- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Nature Versus Nurture

Introduction.

- Genes and Personality

- Genes and Development

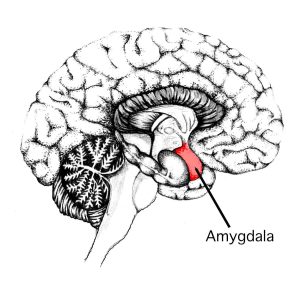

- Brain Structure

- Brain Function

- Criticisms of Nature Theories

- Social Learning

- Parental Attachment

- Child Rearing

- Family Structure

- Family Environment

- Criticism of Nurture Theories

- Development

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Biosocial Criminology

- Developmental and Life-Course Criminology

- Genetics, Environment, and Crime

- James Q. Wilson

- Social Learning Theory

- The General Theory: Self-Control

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Education Programs in Prison

- Juvenile Justice Professionals' Perceptions of Youth

- Juvenile Waiver

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Nature Versus Nurture by Michelle Coyne , John Paul Wright LAST REVIEWED: 30 September 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 30 September 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396607-0163

The nature/nurture debate has raged for decades, both within and outside of criminology. Early biological theories of crime were strongly influenced by Darwinian views of inheritance and natural selection and tended to ignore or downplay environmental influences. Beginning with the early work of Lombroso’s Criminal Man , biological influences were dominant for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The advent of sociology, however, challenged these dominant explanations. Durkheim, Weber, and Marx, for example, each located the causes of crime not in individual pathologies but in the way societies were organized. Various sociological views of crime became widely accepted among scholars as biological theories fell out of favor. This happened in criminology as well. Sutherland, for example, argued that crime was the result of differential socialization and was not caused by individual, heritable factors. Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck, however, argued that the causes of crime were varied and multifaceted—and included biological factors. Sutherland’s view became broadly accepted, which led to the virtual elimination of biological theorizing in criminology from the 1940s until today. Nonetheless, recent advances in the biological sciences have again challenged dominant social views of crime. Unlike early biological theories of crime, the new “biosocial” criminology seeks to understand the various ways biological and environmental variables work together to cause problem behavior. Moreover, much contemporary biological theorizing examines the development of individuals across the life-course as well as issues within the life-course, such as the stability of behavior. Because many scholars now view criminal behavior as the product of nature and nurture, many studies now exist that attempt to account for both processes. Nonetheless, tension between those who view crime as the product of “nature” and those who favor “nurture” remains.

Nature and Development Theories

Nature theories assert that the etiology of criminal behavior is biologically based in genetic inheritance and the structure and functions of people’s brains and other psychological responses. Wilson and Herrnstein 1985 presents the early beginnings and approaches of biosocial theory. Moffitt 1993 presents the author’s classic developmental theory, which is based on a biosocial approach. Modern biosocial approaches of life-course theory and the development of deviant behavior can be found in Wright, et al. 2008 and DeLisi and Beaver 2011 . Fishbein 2004 provides a summation of not only the science but also treatment and prevention practices grounded in nature theories. Anderson 2007 and Walsh and Ellis 2007 present overviews and integrated biosocial approaches in criminology. Pinker 2011 is a controversial text that outlines nature theories and uses them as evidence for declining rates of violence in modern times. See also Lombroso-Ferrero 1972 .

Anderson, Gail. 2007. Biological influences on criminal behavior . Boca Raton, FL: Simon Fraser Univ.

A useful overview of the biosocial perspective of the etiology of criminal behavior focusing on genetic factors as well as the structure and functioning of the brain.

DeLisi, M., and Kevin M. Beaver, eds. 2011. Criminological theory: A life-course approach . Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

An integrated presentation of several perspectives of criminological theories focusing on the development of antisocial behavior from a biosocial life-course perspective.

Fishbein, Diana, ed. 2004. The science, treatment, and prevention of antisocial behavior: Evidence-based practice . 2 vols. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute.

This text presents the origins of antisocial behavior as well as effective theory-based interventions for prevention and treatment of individuals who display them. First published in 2000 ( The science, treatment, and prevention of antisocial behaviors: Application to the criminal justice system ).

Lombroso-Ferrero, Gina. 1972. Criminal man, according to the classification of Cesare Lombroso . Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith.

A reprinted version of Cesare Lombroso’s original work, Criminal Man , written by his daughter Gina. This work chronicles Lombroso’s positivistic approach and study of criminality that laid the groundwork for subsequent biological theories of crime.

Moffitt, Terrie E. 1993. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review 100.4: 674–701.

DOI: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674

A classic theoretical piece classifying offenders into adolescence-limited offenders and life-course-persistent offenders. This suggests that most offenders are delinquent during adolescence and then desist upon entering adulthood, while only a small percentage become lifelong criminals.

Pinker, Steven. 2011. The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined . New York: Viking.

A controversial work that argues violence is declining in society due to advanced genes and evolutionary inheritance. The author capitalizes on human nature and its development over time.

Walsh, Anthony, and Lee Ellis. 2007. Criminology: An interdisciplinary approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

This text presents a compilation of modern criminological theories integrated with biological and psychological explanations of the development of criminality.

Wilson, James Q., and Richard Herrnstein. 1985. Crime & human nature: The definitive study of the causes of crime . New York: Free Press.

An early text on the beginnings of the biosocial theory and approach to causes of criminal behavior. The authors explore patterns of offending, namely who commits crimes and why, focusing on characteristics such as age, gender, race, intelligence, impulsivity, and other constitutional factors.

Wright, John P., Stephen G. Tibbetts, and Leah E. Daigle. 2008. Criminals in the making: Criminality across the life course . Los Angeles: SAGE.

A biosocial approach detailing the structure and genetic makeup of the criminal mind and causes of criminal behavior throughout the life-course.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Criminology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Active Offender Research

- Adler, Freda

- Adversarial System of Justice

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Aging Prison Population, The

- Airport and Airline Security

- Alcohol and Drug Prohibition

- Alcohol Use, Policy and Crime

- Alt-Right Gangs and White Power Youth Groups

- Animals, Crimes Against

- Back-End Sentencing and Parole Revocation

- Bail and Pretrial Detention

- Batterer Intervention Programs

- Bentham, Jeremy

- Big Data and Communities and Crime

- Black's Theory of Law and Social Control

- Blumstein, Alfred

- Boot Camps and Shock Incarceration Programs

- Burglary, Residential

- Bystander Intervention

- Capital Punishment

- Chambliss, William

- Chicago School of Criminology, The

- Child Maltreatment

- Chinese Triad Society

- Civil Protection Orders

- Collateral Consequences of Felony Conviction and Imprisonm...

- Collective Efficacy

- Commercial and Bank Robbery

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- Communicating Scientific Findings in the Courtroom

- Community Change and Crime

- Community Corrections

- Community Disadvantage and Crime

- Community-Based Justice Systems

- Community-Based Substance Use Prevention

- Comparative Criminal Justice Systems

- CompStat Models of Police Performance Management

- Confessions, False and Coerced

- Conservation Criminology

- Consumer Fraud

- Contextual Analysis of Crime

- Control Balance Theory

- Convict Criminology

- Co-Offending and the Role of Accomplices

- Corporate Crime

- Costs of Crime and Justice

- Courts, Drug

- Courts, Juvenile

- Courts, Mental Health

- Courts, Problem-Solving

- Crime and Justice in Latin America

- Crime, Campus

- Crime Control Policy

- Crime Control, Politics of

- Crime, (In)Security, and Islam

- Crime Prevention, Delinquency and

- Crime Prevention, Situational

- Crime Prevention, Voluntary Organizations and

- Crime Trends

- Crime Victims' Rights Movement

- Criminal Career Research

- Criminal Decision Making, Emotions in

- Criminal Justice Data Sources

- Criminal Justice Ethics

- Criminal Justice Fines and Fees

- Criminal Justice Reform, Politics of

- Criminal Justice System, Discretion in the

- Criminal Records

- Criminal Retaliation

- Criminal Talk

- Criminology and Political Science

- Criminology of Genocide, The

- Critical Criminology

- Cross-National Crime

- Cross-Sectional Research Designs in Criminology and Crimin...

- Cultural Criminology

- Cultural Theories

- Cybercrime Investigations and Prosecutions

- Cycle of Violence

- Deadly Force

- Defense Counsel

- Defining "Success" in Corrections and Reentry

- Digital Piracy

- Driving and Traffic Offenses

- Drug Control

- Drug Trafficking, International

- Drugs and Crime

- Elder Abuse

- Electronically Monitored Home Confinement

- Employee Theft

- Environmental Crime and Justice

- Experimental Criminology

- Family Violence

- Fear of Crime and Perceived Risk

- Felon Disenfranchisement

- Feminist Theories

- Feminist Victimization Theories

- Fencing and Stolen Goods Markets

- Firearms and Violence

- Forensic Science

- For-Profit Private Prisons and the Criminal Justice–Indust...

- Gangs, Peers, and Co-offending

- Gender and Crime

- Gendered Crime Pathways

- General Opportunity Victimization Theories

- Green Criminology

- Halfway Houses

- Harm Reduction and Risky Behaviors

- Hate Crime Legislation

- Healthcare Fraud

- Hirschi, Travis

- History of Crime in the United Kingdom

- History of Criminology

- Homelessness and Crime

- Homicide Victimization

- Honor Cultures and Violence

- Hot Spots Policing

- Human Rights

- Human Trafficking

- Identity Theft

- Immigration, Crime, and Justice

- Incarceration, Mass

- Incarceration, Public Health Effects of

- Income Tax Evasion

- Indigenous Criminology

- Institutional Anomie Theory

- Integrated Theory

- Intermediate Sanctions

- Interpersonal Violence, Historical Patterns of

- Interrogation

- Intimate Partner Violence, Criminological Perspectives on

- Intimate Partner Violence, Police Responses to

- Investigation, Criminal

- Juvenile Delinquency

- Juvenile Justice System, The

- Kornhauser, Ruth Rosner

- Labeling Theory

- Labor Markets and Crime

- Land Use and Crime

- Lead and Crime

- LGBTQ Intimate Partner Violence

- LGBTQ People in Prison

- Life Without Parole Sentencing

- Local Institutions and Neighborhood Crime

- Lombroso, Cesare

- Longitudinal Research in Criminology

- Mandatory Minimum Sentencing

- Mapping and Spatial Analysis of Crime, The

- Mass Media, Crime, and Justice

- Measuring Crime

- Mediation and Dispute Resolution Programs

- Mental Health and Crime

- Merton, Robert K.

- Meta-analysis in Criminology

- Middle-Class Crime and Criminality

- Migrant Detention and Incarceration

- Mixed Methods Research in Criminology

- Money Laundering

- Motor Vehicle Theft

- Multi-Level Marketing Scams

- Murder, Serial

- Narrative Criminology

- National Deviancy Symposia, The

- Nature Versus Nurture

- Neighborhood Disorder

- Neutralization Theory

- New Penology, The

- Offender Decision-Making and Motivation

- Offense Specialization/Expertise

- Organized Crime

- Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs

- Panel Methods in Criminology

- Peacemaking Criminology

- Peer Networks and Delinquency

- Performance Measurement and Accountability Systems

- Personality and Trait Theories of Crime

- Persons with a Mental Illness, Police Encounters with

- Phenomenological Theories of Crime

- Plea Bargaining

- Police Administration

- Police Cooperation, International

- Police Discretion

- Police Effectiveness

- Police History

- Police Militarization

- Police Misconduct

- Police, Race and the

- Police Use of Force

- Police, Violence against the

- Policing and Law Enforcement

- Policing, Body-Worn Cameras and

- Policing, Broken Windows

- Policing, Community and Problem-Oriented

- Policing Cybercrime

- Policing, Evidence-Based

- Policing, Intelligence-Led

- Policing, Privatization of

- Policing, Proactive

- Policing, School

- Policing, Stop-and-Frisk

- Policing, Third Party

- Polyvictimization

- Positivist Criminology

- Pretrial Detention, Alternatives to

- Pretrial Diversion

- Prison Administration

- Prison Classification

- Prison, Disciplinary Segregation in

- Prison Education Exchange Programs

- Prison Gangs and Subculture

- Prison History

- Prison Labor

- Prison Visitation

- Prisoner Reentry

- Prisons and Jails

- Prisons, HIV in

- Private Security

- Probation Revocation

- Procedural Justice

- Property Crime

- Prosecution and Courts

- Prostitution

- Psychiatry, Psychology, and Crime: Historical and Current ...

- Psychology and Crime

- Public Criminology

- Public Opinion, Crime and Justice

- Public Order Crimes

- Public Social Control and Neighborhood Crime

- Punishment Justification and Goals

- Qualitative Methods in Criminology

- Queer Criminology

- Race and Sentencing Research Advancements

- Race, Ethnicity, Crime, and Justice

- Racial Threat Hypothesis

- Racial Profiling

- Rape and Sexual Assault

- Rape, Fear of

- Rational Choice Theories

- Rehabilitation

- Religion and Crime

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment

- Routine Activity Theories

- School Bullying

- School Crime and Violence

- School Safety, Security, and Discipline

- Search Warrants

- Seasonality and Crime

- Self-Control, The General Theory:

- Self-Report Crime Surveys

- Sentencing Enhancements

- Sentencing, Evidence-Based

- Sentencing Guidelines

- Sentencing Policy

- Sex Offender Policies and Legislation

- Sex Trafficking

- Sexual Revictimization

- Situational Action Theory

- Snitching and Use of Criminal Informants

- Social and Intellectual Context of Criminology, The

- Social Construction of Crime, The

- Social Control of Tobacco Use

- Social Control Theory

- Social Disorganization

- Social Ecology of Crime

- Social Networks

- Social Threat and Social Control

- Solitary Confinement

- South Africa, Crime and Justice in

- Sport Mega-Events Security

- Stalking and Harassment

- State Crime

- State Dependence and Population Heterogeneity in Theories ...

- Strain Theories

- Street Code

- Street Robbery

- Substance Use and Abuse

- Surveillance, Public and Private

- Sutherland, Edwin H.

- Technology and the Criminal Justice System

- Technology, Criminal Use of

- Terrorism and Hate Crime

- Terrorism, Criminological Explanations for

- Testimony, Eyewitness

- Therapeutic Jurisprudence

- Trajectory Methods in Criminology

- Transnational Crime

- Truth-In-Sentencing

- Urban Politics and Crime

- US War on Terrorism, Legal Perspectives on the

- Victim Impact Statements

- Victimization, Adolescent

- Victimization, Biosocial Theories of

- Victimization Patterns and Trends

- Victimization, Repeat

- Victimization, Vicarious and Related Forms of Secondary Tr...

- Victimless Crime

- Victim-Offender Overlap, The

- Violence Against Women

- Violence, Youth

- Violent Crime

- White-Collar Crime

- White-Collar Crime, The Global Financial Crisis and

- White-Collar Crime, Women and

- Wilson, James Q.

- Wolfgang, Marvin

- Women, Girls, and Reentry

- Wrongful Conviction

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

5.5 Nature versus Nurture: Are We Born Bad?

Crime policy is based on the common belief that humans have free will and “choose” to break the laws; and because of this free will, they should be punished accordingly. But, what if we are born with a propensity to offend? What policy could be created for offenders who were born criminals?

5.5.1 Psychodynamic Theory

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Nature versus Nurture: Biosocial Theories of Crime

Antoinette L. Smith and Tracy Meehan

Learning Objectives

- Understand the fundamental concepts and principles of biosocial criminology and investigate how biological and social factors interact to influence aggression and antisocial behaviour.

- Identify and compare three major areas of biosocial criminological research: nutrition; genetics; and traumatic brain injury.

- Be able to address historical and current criticisms of biosocial criminology and understand the role of ethics and morality in this type of criminological approach.

Before You Begin

- How does your environment affect you? Do you cranky when you are hungry? Anxious or annoyed when you are cold? Take a moment to think about how your body reacts to your environment. Does that affect your behaviour?

- Have you ever read or heard about instances where medical or scientific professionals have acted in an unethical or immoral manner? What types of situations? How did this make you feel?

- It’s easy to understand where we inherit our physical traits. But what about our personality traits? Do you share personality traits with the people you grew up with or the people you are related to? If you had to make a bet, would you bet that you inherited those similar traits or learned them?

INTRODUCTION

It’s no surprise that we inherit traits from our families. It may be our height or our hair colour or any number of other physical traits. But of long interest in criminology is whether personality traits are inherited, particularly those relating to crime and aggression. The long-standing nurture vs. nature debate in social sciences has advocates on both sides but these days, we can sum it up by saying “it depends.” The research into the overlap between biological and social explanations of crime is known as biosocial criminology (Barnes et al., 2015). The body of work exploring criminal behaviours within this discipline is a broad framework borrowing theories and concepts from at least five other disciplines, including: evolution, biology, genetics, neurology and sociology.

Biosocial theory helps us understand the interplay between internal behavioural influences, such as the ways our brains, bodies and genes work, and external behavioural influences, including who we spend time with, the societies we live in, and the cultures we experience. Biosociology offers a more comprehensive explanation for criminal behaviours, rather than traditional or standalone theories have provided. If you have watched any historical detective movies, you may have heard about the study of ‘phrenology,’ when people thought that bumps and divots in our skull could help determine criminals from non-criminals [1] (Bedoya & Portnoy, 2023; Larregue & Rollins, 2019). While we now know this was a silly idea, the study of phrenology helped usher in a period of increased data collection and evidence based scientific endeavors, known as positivism . This early form of biological research has changed dramatically over the decades into what we now know as biosocial criminology.

We have come a long way since criminals were catalogued by their head bumps and limb lengths. And what we have learned is that biology is not destiny. But it does serve a purpose is helping us understand the relationships between our physical, psychological, social and inherited experiences.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Biosocial criminology developed over time by combining research from a range of complementary disciplines, like evolution, genetics, sociology, and environmental theories. During the 19th century, thanks to the work of people like Charles Darwin and Sir Francis Galton, research focused on evolution-based explanations of behaviour. After all, if evolution helped plants and animals change over time, surely it could explain behavioural traits as well (Berryessa & Cho, 2013; Green, 1997). Biosocial theory was first introduced in the 1950s by the German-British psychologist Hans Eysenck, although it did not initially gain much traction in the research community. While recognising the importance of biology in understanding crime, Eysenck also emphasised the importance of social influences like friends and family (Brennan & Raine, 1997).

But one reason that the idea did not gain traction early on was related to the fact that in the 1950s and 1960s, most of the world was still recovering from learning about the atrocities committed during the Holocaust in World War II. During this time, governments and universities began creating new ethics review processes and were more critical about the best ways to study people. Biological research like twin studies where no longer in favour.

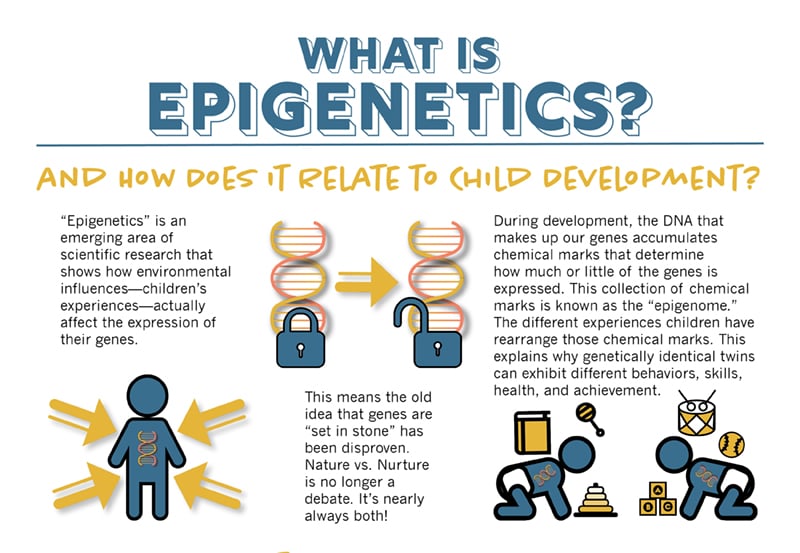

As all types of science adopted more ethical and moral principles of research in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, researchers moved increasingly back towards a focus on biosocial explanations of criminality (Rocque et al., 2012). Improved technologies as well as worldwide efforts that made up the Human Genome Project (which began in 1990) sparked more interest in the role that biology could play in helping us understand aggressive behaviour. It is then when we now think of as biosocial criminology re-emerged (Barkow et al., 1995; Tremblay et al., 2005). Over time, other disciplines have been drawn into the conversation, including epigenetics, environment-interactions, and life-course psychology (Fraga et al., 2005; Wortley, 2011).

Table 11.1 Biosocial Theory – Timeline

What is biosocial criminology.

There is not one kind of biosocial criminology. In fact, there are several biosocial theories to explain crime and aggression. What they all have in common is an assumption that one’s biology interacts with the environment in which they live, and this interaction affects behaviour. Some biosocial theories focus on the inherited nature of biological traits, such as how hormones can influence aggression. Other biosocial theories focus on how our bodies interact with the world around us, such as understanding the effects of brain injuries or nutritional deficiencies on later life outcomes. What they all have in common is that they investigate how the complex interaction between us and our environments.

The contribution of biology has traditionally been about making connections between biological factors, such as hormones, genetic markers, and biochemical factors, and our behaviour (Raine, 2002). For instance, males are more likely to have higher testosterone levels than females, which has led some to come to the conclusion that men are more prone to aggressive crimes, like assault or intimate partner violence (Burgess & Draper, 1989). Other researchers have examined the structure and function of the brain in trying to understand criminal behaviour, finding connections between the overstimulation or under stimulation certain regions of the brain and aggressive behaviour (Raine et al, 1997; Raine, 2002). Recent research has turned to the role of health, particularly nutrition, on individual behaviour and connections to aggression (Jackson, 2016).

For the remainder of the chapter, we will focus on three major research areas that fall under the umbrella of biosocial criminology: the role of nutrition; genetics; and brain injury.

THEORY APPLICATION

Nutrition and crime.

Have you ever been so hungry that you couldn’t think straight? Or maybe you’ve been uncharacteristically mean to a friend when you were ‘hangry.’ We may joke and make memes about how we act when we are hungry, but it’s been in a verifiable truth: you are, in fact, what you eat. The food we consume what food does to our bodies impacts our behaviour. Criminologists in particular have been interested in the role that malnutrition has on childhood behaviour.

Two major patterns stand out. The first is the role that omega-3 fatty acids have on reducing behaviour. Omega-3 fatty acids are known as the “healthy fat” and are typically found in seafood, seeds and nuts. In a study where children were randomly assigned to receive omega-3 supplementation versus not supplements, caretakers reported that children who received the reduced disruptive behaviours 6 months later (Raine et al., 2015). A large-scale meta-analysis [2] showed that omega-3 fatty acid consumption is associated with reduced aggression (Gajos & Beaver, 2016). So eat your mackerel!

But the relationship between nutrition and aggression isn’t limited to omega-3 fatty acids. Malnutrition in general has been found to be associated with increased antisocial behaviour in preschoolers (Jackson, 2016) and adolescents (Galler et al., 2012). An important factor in this connection is to look more closely into why young people are malnourished to begin with. Food insecurity is a real problem in many parts of the world, including Australia. Families experiencing food insecurity are more likely to experience malnutrition, which is then linked to childhood misconduct and delinquency (Jackson & Vaughn, 2017). As you can see, this is the interplay between biology (nutrition) and sociology (access to quality food).

Genetics and Crime

No chapter on biosocial criminology would be complete with a discussion of the role of genetics in understanding aggression and criminality. First and foremost, there is no crime gene. As we have seen in Chapter 2, crime is inherently a social construct. Therefore, most research into genetics and crime focuses on aggressive behaviour. And studies of genetic relationships to aggression remain controversial, due to the historical connections with the study of eugenics and unethical research of the early and mid-twentieth century.

Genetic research has studied twins or siblings in an attempt to understand the role of heredity on behaviour. The most famous studies of genetics and crime are twin studies. The most controversial were adoption studies, where twins were separated into different homes in order to determine the role of nature versus nurture. But many other studies looked for similarity in behaviours between family members. The most common finding is that self-control appears to be, in part, inherited (see Chapter 9 for more discussion on self-control control) (Schwartz et al., 2017).

There have also been advancements in how we have studied the contribution of genetic influences to behaviour. Much of this improved understanding comes from the field of epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of how genes change expression, depending on our environment. Changes to people’s diet or exposure to different group membership may influence when genes are ‘switched on’ or left untouched (Wortley, 2011). For example, a person maybe prone to addiction but without exposure to drug use, the potential to become addicted is never realised. Conversely, the influence of drug users in friendship groups may cause a person with addictive personality traits to become easily addicted. The long and short of it is that nature and nurture interact to influence our development (Moffitt, 2005).

Mental Health and The Criminal Justice System

The link between mental health and the criminal justice system is an important connection that draws significant attention from researchers. In this text, three research papers conducted within Australia will be discussed. These studies examine how mental health affects reoffending risks, incarceration rate and the overrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in the criminal justice system. These findings are significant as they emphasise the need for further research, practical interventions and additional support systems that address mental health disorders for vulnerable individuals.

The research article titled Psychiatric illness and the risk of reoffending: recurrent event analysis for an Australian birth cohort by Ogilvie et al. (2021) is the first focus of this discussion. This paper was sampled from the 1983 to 1984 Queensland birth cohort, consisting of 83,362 individuals (48.5% female, 51.5% male) and 4,821 Indigenous Peoples (5.8%). The findings revealed that individuals with psychiatric illnesses were more susceptible to engaging in repeated criminal behaviour. Individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis reoffended 73.1% of the time, compared to 56% for individuals without a condition. Reappearances of people with a psychiatric diagnosis in court occurred in violent (20.5 vs. 8.5%), nonviolent (60.3 vs. 40.3%) and other minor (61.7 vs. 44.1%) offences compared to those without a psychiatric diagnosis. This study shows that more frequent criminal contact could exacerbate psychiatric illnesses, potentially creating further offending risks, demonstrating the critical necessity of addressing mental health concerns within the criminal justice system to break the reoffending cycle and foster better outcomes for those involved.

The second paper is titled Lifetime prevalence of mental illness and incarceration: An analysis by gender and Indigenous status by Stewart et al. (2020). This study sampled individuals with a 1990 birthdate and found a concerning overrepresentation of individuals with mental health issues among the incarcerated population, with a notably disproportionate impact on Indigenous Peoples and women. Among the individuals sentenced to custody, one-third had a mental health diagnosis, in contrast to only 6.1% of the total birth cohort population. Indigenous Peoples with a mental health diagnosis were 6.14 times more prone to receiving a custodial sentence than non-Indigenous individuals with a mental health diagnosis. Similarly, females with a mental health diagnosis were 5.49 times more likely to receive a custodial sentence than males with a mental health diagnosis. Identifying these vulnerable groups has revealed an urgent need for targeted interventions and culturally sensitive mental health support within the criminal justice system.

The last journal article that will be discussed is titled Psychiatric disorders and offending in an Australian birth cohort: Overrepresentation in the health and criminal justice systems for Indigenous Australians by Ogilvie et al. (2021). This study explored the overlap between mental health and offending, focusing on Indigenous Peoples. Similarly, this study examined a population-based birth cohort of individuals born in Queensland in 1990. Of the individuals with a psychiatric illness diagnosis, 53.0% also had a proven offence; this being much higher for Indigenous Peoples, with the statistic being 80.5% compared to 47.0% for non-Indigenous Peoples. By 23/24, 16.2% of Indigenous Peoples with a proven offence had also received a substance use disorder diagnosis, compared with 7.8% of non-Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples with a diagnosed disorder were also most likely to have more than five proven offences (39.2% vs. 3.3%). These statistics show the extreme over-representation of Indigenous Peoples with mental health diagnoses who have had contact with the criminal justice system. It demonstrates that a psychiatric diagnosis could increase the risk of earlier and more frequent criminal justice contact, emphasising that Indigenous Peoples with a psychiatric disorder are a highly vulnerable group.

Overall, these findings highlight the significant overlap between mental health issues and the criminal justice system. The research advocates for expanding culturally appropriate mental health interventions, particularly within substance use disorders. Additionally, it supports the idea that early diversion and intervention during initial contact with the criminal justice system could be an effective strategy to prevent future reoffending into adulthood for vulnerable people. This research and understanding of how mental health and the criminal justice system intersect are vital to paving the way for more compassionate and successful approaches to supporting vulnerable individuals and reducing the cycle of reoffending.

A summary by Chole Veerman

Traumatic Brain Injury

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an injury of the brain that occurs as the result of a physical impact to the head or body. Causes are diverse but can include falls, car accidents and assaults. Even sports can lead to TBI. It is estimated that up to 200,000 TBI occur in Australia each year, but many are unreported or undiagnosed. In recent years, criminologists have realised that TBI can affect behaviour and may increase violence and aggression, as well as have other negative life consequences. One research study collected information from a group of high risk justice involved young people in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (USA) and Phoenix, Arizona (USA). Youth who experienced a TBI had higher levels of delinquency, bullying, and impulsivity (a trait commonly associated with low self-control) (Silver et al., 2020).

Because individuals can obtain a TBI in ways that are not related to criminal activity, like sports, there is still a lot we do not know about TBI in justice involved populations. Certainly, the type of brain injury will affect the types of behavioural outcomes that could happen. We are learning more about the functions of the brain through advancements in technology that allows us to view the structure of the brain. Using technology such as fMRIs (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging), researchers have identified the parts of the brain that may be related to antisocial behaviour. The amygdala is a region of interest (Kaya et al, 2020). The amygdalae are small almond shaped brain structures on either side of the brain hemisphere that help regulate emotion, including fear. Research suggests that individuals with smaller amygdalae are more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour (Kleine Deters et al., 2022). Whether due to biology or injury, brain structure appears to matter. This is an area where we can continue to expect major contributions to our understanding of criminality in the near future.

THEORY CRITICISMS

In addition to the criticisms already raised in relation to the application of biosocial theory on race and the previously poor ethical practices, many criminologists object to ideological elements that underpin this theoretical approach (Walsh & Wright, 2015). These criticisms relate to determinism, reductionism, and the nature of socially constructed crime. Many argue that a biosocial approach to understanding crime is too deterministic and does not give enough credit to individual decision making. When genes or brain functions are linked to criminality, how do we separate out those who exhibit the trait but do not engage in criminal behaviour?

Similarly, critics of biosocial approaches argue that they are reductive, or overly simplify diverse human behaviour rather than recognising the intense interplay of the environment and social influences (Heylen et al., 2015). For instance, aggressive behaviour may be linked to genes, whereas in reality, the potential for aggression may not be realised unless certain environmental or situational factors are present, such as peer pressure or the presence of an antagonist.

Finally, crime is, and always has been, social (Walsh & Wright, 2015). For instance, consuming alcohol in Dubai is illegal without a permit, whereas it is unregulated for people over the age of 17 in Australia. Similarly, using cannabis is illegal in 25 of the 50 American states, with another 14 legalising medicinal cannabis (Tyko, 2023), and Australia looks like it is headed in that direction. The social construction of crime means that anything considered legal is ignored in research analyses, leaving some important political, social, or environmental factors unconsidered.

THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY

The findings from multifactorial studies with a biosocial focus have helped shape our responses within the criminal justice system and provided new ways to envision prevention and rehabilitations. A better understanding of the diverse causes of criminality brings with it the opportunity to improve outdated systems and incorporate innovative new approaches. Newsome and Cullen (2017) provide an example of this improvement when they updated the ‘risks, needs and responsivity model’ used within criminal rehabilitation. By incorporating biosocial factors like genetics, neurobiology, physiology and nutrition into the existing model of understanding behaviour, neurological and physiological assessments can improve current risk assessments. By continuing to focus on biosocial research elements relating to crime, further improvements to criminal justice system responses will continue to emerge.

The application of biosocial desistance models has moved from understanding young people to better supporting adults, especially with what we have learned about brain structure and function (Boisvert, 2021). Through neuropsychological functioning studies, we have learned that incarcerating low-risk individuals is more likely to induce stress system responses which will impact future brain development, indicating imprisonment should be used as a last resort only. Other research on brain development also shows that high-risk individuals who are incarcerated may benefit from programs to minimise diminished cognitive functioning, such as increased sleep time and limited time in solitary confinement. These changes involve identifying genetic risk factors, understanding the impact of exposure to criminogenic environments within dynamic and static needs assessments, and including a range of cognitive-based treatments in criminal justice responses (Boisvert, 2012).

A Note about Biosocial Criminology and Race

Biosocial theory has previously been used to explain the social and biological ways we understand racial groups (Larregue & Rollins, 2019). However, critics are cautious when applying biosociology to race because of the tendency of some researchers to link criminality to minority populations, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Doing so actively ignores the fact that race is a social construct and reducing people to their race ignores important structural, community, intergenerational and social differences in how people experience their identify. Larregue & Rollins (2019) argue it is impossible to control for race in research as it does not capture the complexities of social relationships and practices. Any attempts to do so are likely to led to racist outcomes such as colour-blind interpretation, or researchers erring towards blaming races for an increased risk in criminality. This is principally problematic considering the social construction of race and diversity within cultures.

The same is true for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. With more than 500 communities living in Australia and surrounding islands, they are not a homogenous group ( Evolve Communities ). Trying to account for the differences in traditions and practices between these communities is unrealistic in single studies comparing differences between non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. For example, there are differences in languages, laws, belief systems and relationships within these 500 communities. Failure to recognise these differences has led to criticisms of Pan-Aboriginalism in Australia; the failure to recognise the uniqueness of hundreds of communities and the tendency to attribute similar characteristics to all communities broadly.

Research conducted by Larregue & Rollins (2019) shows the problematic nature of applying race within biosociology. They reviewed 107 studies exploring biosocial criminality and found race was comprehensively studied in only three of the 107 studies . However, even in these few cases, researchers failed to look at the ‘effects of race’ and criminality, for instance the social mechanisms contributing to and influencing racial populations in set societies. Therefore, it is not possible to truly apply biosocial theory to the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. However, the theory does have other application uses mainly relating to the criminal justice system.

For more information about how people understand race and racial identify, the National Human Genome Institute at the US National Institutes of Health is a good place to start. Australia is more likely to use the terms ethnicity and indigeneity to describe individuals who are part of distinct cultures within our communities (Kowal & Watt, 2018). To many, biological constructions of ‘race’ ignore the realities of shared culture and social status as being an important part of identifying with a community. While new discoveries come every day, the field of genomics is still quite new and it requires us to be critical of findings that separate people into categories that are not supported by science or sociology.

Biosocial theory is an interdisciplinary framework for evaluating human behaviours, including aggression and criminality. The intersection between biological and environmental influences remains an important part of contemporary criminological research. While the theory has not always been favoured in the scientific community, the application of more ethical practices, combined with more advanced technology, has increased interest and improved our knowledge about how to adapt prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation efforts.

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion questions.

- Define biosocial theory in the context of criminality and discuss how it integrates biological and social factors to explain criminal behaviour. Provide examples to illustrate the key concepts of biosocial theory and its application to understanding crime.

- Consider the practical applications of biosocial theory in the development of interventions and prevention strategies. Reflect on how a better understanding of the biological and social factors contributing to criminal behaviour can inform targeted interventions. How might this knowledge be used to identify at-risk individuals early on and implement effective preventative measures?

- Explore the ethical considerations associated with applying biosocial theories to criminality research. Discuss potential implications for stigmatization, discrimination, and the broader societal impact. How can researchers ensure cultural sensitivity and ethical conduct when studying the biosocial aspects of criminal behaviour.

Barkow, J. H., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (Eds.). (1995). The adapted mind: evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture . Oxford University Press.

Barnes, J. C., Boutwell, B. B., & Beaver, K. M. (2015). Contemporary biosocial criminology: A systematic review of the literature, 2000–2012. The handbook of criminological theory , 75-99.

Bedoya, A., & Portnoy, J. (2023). Biosocial criminology: History, theory, research evidence, and policy. Victims & Offenders , 18 (8), 1599-1629.

Berryessa, C. M., & Cho, M. K. (2013). Ethical, legal, social, and policy implications of behavioral genetics. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics , 14 , 515-534.

Boisvert, D. L. (2021). Biosocial factors and their influence on desistance. NCJ 301499, in Desistance From crime: Implications for research, policy, and practice (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, 2021), NCJ 301497. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/301499.pdf

Brennan, P. A., & Raine, A. (1997). Biosocial bases of antisocial behavior: Psychophysiological, neurological, and cognitive factors. Clinical psychology review , 17 (6), 589-604.

Burgess, R. L., & Draper, P. (1989). The explanation of family violence: The role of biological, behavioral, and cultural selection. Crime and Justice , 11 , 59-116.

Fraga, M. F., Ballestar, E., Paz, M. F., Ropero, S., Setien, F., Ballestar, M. L., … & Esteller, M. (2005). Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 102 (30), 10604-10609.

Gajos, J. M., & Beaver, K. M. (2016). The effect of fatty acids on aggression: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews , 69, 147–158. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.017

Galler, J. R., Bryce, C. P., Waber, D. P., Hock, R. S., Harrison, R., Eaglesfield, G. D., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2012). Infant malnutrition predicts conduct problems in adolescents. Nutritional Neuroscience , 15(4), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000012

Green, C. D. (1997). The principles of psychology William James (1890). Classics in the history of psychology .

Heylen, B., Pauwels, L. J., Beaver, K. M., & Ruffinengo, M. (2015). Defending biosocial criminology: On the discursive style of our critics, the separation of ideology and science, and a biologically informed defense of fundamental values. Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology , 7 (1), 83.

Jackson, D. B. (2016). The link between poor quality nutrition and childhood antisocial behavior: A genetically informative analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice , 44, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.11.007J

Kaya, S., Yildirim, H., & Atmaca, M. (2020). Reduced hippocampus and amygdala volumes in antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience , 75, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.01.048

Kleine Deters, R., Ruisch, I. H., Faraone, S. V., Hartman, C. A., Luman, M., Franke, B., Oosterlaan, J., Buitelaar, J. K., Naaijen, J., Dietrich, A., & Hoekstra, P. J. (2022). Polygenic risk scores for antisocial behavior in relation to amygdala morphology across an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder case-control sample with and without disruptive behavior. European Neuropsychopharmacolog y , 62, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.07.182

Kowal, E., & Watt, K. (2018) What is race in Australia? Journal of Anthropological Studies, 96 , 229-237. https://www.isita-org.com/jass/Contents/2018vol96/Kowal/30640719.pdf

Larregue, J., & Rollins, O. (2019). Biosocial criminology and the mismeasure of race. Ethnic and Racial Studies , 42 (12), 1990-2007.

Moffitt, T. E. (2005). The new look of behavioral genetics in developmental psychopathology: Gene-environment interplay in antisocial behaviors. Psychological Bulletin , 131(4), 533–554. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.533

Newsome, J., & Cullen, F. T. (2017). The risk-need-responsivity model revisited: Using biosocial criminology to enhance offender rehabilitation. Criminal Justice and Behavior , 44 (8), 1030- 1049.

Raine, A. (2002). The biological basis of crime. Crime: Public policies for crime control , 43 , 74.

Raine, A., Portnoy, J., Liu, J., Mahoomed, T., & Hibbeln, J. (2015). Reduction in behavior problems with omega-3 supplementation in children aged 8-16 years: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stratified, parallel-grouptrial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines , 56(5), 509–520.

Rocque, M., Welsh, B. C., & Raine, A. (2012). Biosocial criminology and modern crime prevention. Journal of Criminal Justice , 40 (4), 306-312.

Schwartz, J. A., Connolly, E. J., Nedelec, J. L., & Beaver, K. M. (2017). An investigation of genetic and environmental influences across the distribution of self-control. Criminal Justice and Behavior , 44(9), 1163–1182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854817709495

Silver, I. A., Province, K., & Nedelec, J. L. (2020). Self-reported traumatic brain injury during key developmental stages: Examining its effect on co-occurring psychological symptoms in an adjudicated sample. Brain Injury , 34(3), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1723166

Tyko, K. (2023). Where is marijuana legal – and illegal – 2023 . AXIOS. https://www.axios.com/2023/04/20/weed-pot-april-20-medical-marijuana-legal#

Tremblay, R. E., Hartup, W. W., & Archer, J. (Eds.). (2005). Developmental origins of aggression . Guilford Press.

Jackson, D. B., & Vaughn, M. G. (2017). Household food insecurity during childhood and adolescent misconduct. Preventive Medicine , 96, 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.042

Walsh, A., & Wright, J. P. (2015). Biosocial criminology and its discontents: A critical realist philosophical analysis. Criminal Justice Studies , 28 (1), 124-140.

Wortley, R. (2011). Psychological criminology: An integrative approach (Vol. 9). Taylor & Francis.

- Spoiler alert: the bumps in your head do not predict your personality. No matter what you saw on TV. But if you want to know about phrenology, check out this article published in the journal Cortex. ↵

- A meta-analysis is a study that takes information from all existing studies on one topic and comes to a conclusion about what the totality of the evidence says. It is very useful when there are a lot of studies and it can be difficult to keep track of which one is the most recent or the best done. This way, all of the research is put together to make an overall stronger conclusion. ↵

an approach to society that relies on empirical evidence and observation, often including experiments and other similar methdologies

a statistical study that combines findings from several independent studies on the same subject, in order to determine the totality of the evidence

Introduction to Criminology and Criminal Justice Copyright © 2024 by Antoinette L. Smith and Tracy Meehan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Nature vs. Nurture (Criminology is at it Again!)

There are many theories that have been developed which attempt to explain the causes of criminal behaviour, including explanations of crime which focus on the individual – his or her thought process, biological factors, and psychological factors; and explanations of crime which focus on factors external to the individual – the surrounding environment, others who influence the individual, and society as a whole. These two areas of criminology are often seen to be in direct conflict with each other. Nowadays most criminologists agree that it isn't an either-or situation – internal factors and social factors both play a part in determining one's behaviour. This essay takes the same view and argues that both sides of criminology have their strengths and weaknesses in explaining crime, and the notion that only internal or external factors can be the cause for an individual being criminal is outdated. To demonstrate that neither explanations of crime are more convincing than the other, this essay will examine both biological theories and ecological theories and compare them against each other. In doing so, each theory and their origins will be explained, the weaknesses of each theory will be explored, and the crimes that each theory can explain will be stated. Biological theories are interested in the inherited genetics of the individual to determine their predisposition to antisocial behaviour (Hirschi & Gottfredson 1990, p. 414). Cesare Lombroso, dubbed " the father of modern criminology " , popularised biological positivism during the nineteenth century. His general theory proposed that 'the criminal was born, not made' – he believed that atavistic criminals (people who are biologically inferior) were a reversion of the human specimen, having physical features similar to that apes and early man – such a person could be identified by examining their appearance and noting any physical abnormalities or 'stigmata' (White, Haines & Asquith 2012, p. 49).

Related Papers

Sakin Tanvir

Indian Legal Solution Journal of Criminal and Constitutional Law

Faizan Anwer

We are living in a multidisciplinary era. Since the dawn of civilization, every field of study have progressed at its own pace and there have been continuous research and findings at different levels of different diversified fields. There was a time when shooting off of various sciences was an essential phenomenon for inculcating expertise and advancement within a particular area of study. Now all these branches are converging and interconnecting and forming nodes with other fields. Legal studies are no exception to this. In this article, we will try to put some light on criminology with the glasses of biology. The phenomenon of crime integrates multiple factors including human behaviour, psychology, sociology, parenting, forensics, and more recently genetics. The genes present in our very cells may be the causal agent for criminal behaviour, but it’s not a tool to escape from the punishment of one of the most heinous crimes done by most advanced species, Homo sapiens present on the face of the earth. In the advanced modern societies, government prepare the databases of DNA fingerprints of the evil souls of the society. There have been detailed discussions on eugenics and epigenetics. One of the interesting facts is that capital punishment may be one of the methods of implementing eugenics in the core of civilization. The phrase of nature and nurture is very analogous to genetics and epigenetics in this scenario. We all are the products of genetic composition and socioenvironmental factors. Does this rob our free will or does this make us liable?

Diana Shlyapnikova

Through many centuries, criminal behavior was mistakenly explained mostly with biological defects of the individual. It was believed, that abnormal actions, negatively affected society, were preferably conducted by those, who suffered from serious physical deviations in development. However, as the science was progressing, scholars have begun searching other possible causes of the formation of antisocial behavior and psychology began to actively explore this area. Nowadays, it is known, that incorrect parenting style, negative influence of environment, and formation of improper role models may significantly result inner conflicts and thus, led to the abnormal behavior. In this essay, we would further examine, how these aspects can influence the behavior of individuals and lead to criminal conduct, illustrating it with examples from biographies of famous criminals to show how concepts can be applied in reality. First of all, it is necessary to draw a distinction between biological and psychological factors, influencing the behavior of individual. Under biological factors we mean physical anomalies, such as neurotransmitter dysfunction, bradygenesis, and other problems of neural development, genetically predisposed or caused by trauma or injury. Under psychological factors we mean mental disorders, and deviation in education and mental development of the individual. However, despite the fact that the differences seem obvious, both areas are interconnected between deeply. As we know, the connection of nature and nature is rooted into every individual. As the course textbook states " everything psychological is simultaneously biological " (Meyers, 1999, Chapter 2, p.47). Thus, various theories, designed to explain the emerging and development of deviant behavior, combine both approaches. For example, theory of personality and crime by Hans J. Eysenck, British psychologist, states that each individual has innate hereditary predisposition towards asocial behavior, which discloses in certain circumstances. Thus, " criminal behavior is the result of an interaction between certain environmental conditions and features of the nervous system " (Bartol & Bartol, 2005). However, Eysenck does not say, that deviant behavior inborn, but may be caused by the compound of heredity and environment. It is not itself, or criminality that is innate; it is certain peculiarities of the central and autonomic nervous system that react with the environment, with upbringing, and many other environmental factors to increase the probability that a given person would act in a certain antisocial manner (Eysenck & Gudjonsson, 1989)

Current Issues in Criminal Justice

Allan McCay

Elisabetta Sirgiovanni

At the end of the nineteenth century the Italian physician and anthropologist Cesare Lombroso established the foundations of criminological sciences by introducing a biological theory of delinquency, which was later discredited and replaced by the sociological approach. The theory of the " born criminal " was poor in methods and analysis, and turned out to be controversial in its formulations, assumptions, and mostly in its predictions. However, recent research in behavioral genetics and neuroscience has brought back some version of the Lombrosian idea by providing evidence for the genetic and biological correlates of criminality. This research has been impacting legal proceedings worldwide. In this paper, I compare the Lombrosian and the contemporary scientific meanings of "heredity" and "predisposition" to aggressive and violent behavior, by highlighting theoretical similarities and differences in the two approaches. On the one hand, the paper is arguing against the idea that contemporary theories are radically deterministic, while on the other hand it aims at rehabilitating the intellectual image of Lombroso by showing that the denigration of his brilliant work by his successors was unjustified.

Aggressive Behavior

Anthony Mawson

sumbul fatima

Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences

David Speicher

The question of why some individuals commit vile acts is a subject that has challenged criminologists, psychologist and sociologists for many years. Research has demonstrated there is no simple answer, since criminologists all seek to explain the phenomenon of violent crime in different theoretical concepts. The science of criminological convention thus becomes a science of conflicting ideologies. It is therefore noted that criminologists format their theoretical concepts according to the type of crime they are explaining. The question remains, how to explain the violent and vile acts of human beings. Could it be construed that our genetic dispositions sway towards carrying out these acts, or indeed an abusive childhood which was fuelled by poverty, bad parenting and a dysfunctional social standing. This paper therefore proposes to examine the nature verses nurture debate. This debate is fundamentally one of the oldest issues in psychology, which centres on the relative attributes of genetic inheritance and environmental factors to human development.

Imran Ahmad Sajid

These are introductory slides for undergraduate students at the University of Peshawar.

RELATED PAPERS

Sami Aldeeb

Ruut Veenhoven

Jurnal Aplikasi Teknologi Pangan

Yoga Pratama

Earthquake Spectra

Alisa F. Stewart

Akdeniz Spor Bilimleri Dergisi

emre şimşek

The Veterinary Journal

Joanna Dukes-mcewan

NASN School Nurse

Elizabeth Richardson

Chemistry Letters

Tsuyoshi Ochiai

Computational Optimization and Applications

BMC Genomics

R. Alan Harris

Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine

Rodrigo Bustamante

Proceedings of the XSEDE16 Conference on Diversity, Big Data, and Science at Scale

james esheka taylor

Food and Energy Security

Salete Gaziola

1比1仿制维多利亚大学毕业证 victoria毕业证硕士学位GRE证书原版一模一样

Journal of Sohag Agriscience (JSAS)

Abdelsabour Khaled

Health technology assessment (Winchester, England)

Susan Michie

Rebecca Treiman

PLHIS Caruaru: Plano Local de Habitação de Interesse Social

André A R A Ú J O Almeida

International Journal of Surgery Case Reports

Konstantinos Stamou

Andreea Antonescu

Human & Experimental Toxicology

Martin Mozina

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Columbia College

Nature vs. nurture resource guide, about this guide, get started, selected e-books, key databases, streaming videos, need help contact us., attribution.

This guide was created by Vandy Evermon for the assignments related to the influence of environment or genetics on criminal behavior. If you have any questions, please contact us.

This resource guide is designed to provide information on the topic of the causes of criminal behavior, whether environment or genetics.

Key words that are useful for this topic are:

- Nature versus nurture

- Criminal behavior and causes

- Criminal behavior and genetics

- Criminal behavior and environment

Below are some articles on this topic.

- Nature vs. Nurture Debate Research Starter One of the longest-running controversies in psychology, the “nature versus nurture” debate is an academic question as to whether human behaviors, attitudes, and personalities are the result of innate biological or genetic factors (the “nature” side of the debate) or life experiences and experiential learning (“nurture”).

- Nature versus Nurture and Criminal Behavior Virtual Criminology: Insights from Genetic-Social Science and Heidegger Full text, peer reviewed article

- Criminal Behavior and Genetics Full text, peer reviewed articles

- Criminal Behavior & Genetics in PsycARTICLES Full text, peer-reviewed articles.

- Criminal Behavior and Environment Full text, peer reviewed articles

- Nature Nurture Controversy and Crime Full text, peer reviewed articles in Academic Search Complete database.

- Nature and Nurture Articles Articles about nature and nurture.

- Nature and Nurture Includes books and e-books at Columbia College.

- Human Beings Effect of Environment On Includes books and e-books at Columbia College.

- Nature Versus Nurture The topic page on this subject from the Credo Reference database. Includes essays from Credo Reference e-books. Includes a a mind map of related terms that you can link to.

- Criminal Justice ProQuest Criminal Justice is a database supporting research on crime, its causes and impacts, legal and social implications, as well as litigation and crime trends. This database covers U.S. and international scholarly journals, it includes correctional and law enforcement trade publications, crime reports, crime blogs, and other material relevant for researchers.

- PsycARTICLES PsycARTICLES, from the American Psychological Association (APA), is a source of full-text, peer-reviewed scholarly and scientific articles in psychology. The database contains full-text peer-reviewed articles published by the American Psychological Association and affiliated journals.

- Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection The Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection provides the full text of articles from journals covering topics such as behavioral characteristics, psychology, mental processes, anthropology, and observational and experimental methods.

- SocINDEX with Full Text SocINDEX with Full Text offers comprehensive coverage of sociology, encompassing all sub-disciplines and closely related areas of study. Full-text journals, informative abstracts, books, monographs, conference papers and other non-periodical content sources, the database also includes searchable cited references for core coverage journals.

- Breaking the Wall of Nature and Nurture: How Genes and Environment Combine to Affect our Life Course What determines human behavior? In this video of his 2010 Falling Walls Conference lecture, Dalton Conley would say nature and nurture both play a role.

- My Genes Speak for Me: Reconciling Nature and Nurture This film explores the possibility that genetics and environment are not diametrically opposed when it comes to human development—instead, the program asserts, they should be seen as complementary.

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 8:14 PM

- URL: https://library.ccis.edu/crimebehavior

- Introduction to Genomics

- Educational Resources

- Policy Issues in Genomics

- The Human Genome Project

- Funding Opportunities

- Funded Programs & Projects

- Division and Program Directors

- Scientific Program Analysts

- Contact by Research Area

- News & Events

- Research Areas

- Research investigators

- Research Projects

- Clinical Research

- Data Tools & Resources

- Genomics & Medicine

- Family Health History

- For Patients & Families

- For Health Professionals

- Jobs at NHGRI

- Training at NHGRI

- Funding for Research Training

- Professional Development Programs

- NHGRI Culture

- Social Media

- Broadcast Media

- Image Gallery

- Press Resources

- Organization

- NHGRI Director

- Mission & Vision

- Policies & Guidance

- Institute Advisors

- Strategic Vision

- Leadership Initiatives

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Partner with NHGRI

- Staff Search

Nature vs. Nurture in the Criminal Justice System

Background:.

The pace of research into genetic factors that may influence how we think and act has increased drastically in the last few years. Some forms of mental illness have a strong hereditary component. For example, scientists are trying to determine how genetic factors make some people more susceptible to disorders like schizophrenia, depression and alcoholism. They also are exploring the contributions of genes to certain personality traits, like shyness and impulsiveness.

Scientists currently believe that the vast majority of human behaviors and traits reflect a complex mix of genetics and the environment. It is unlikely that they will discover single genetic mutations that determine such characteristics as intelligence or that fully account for why some people become aggressive or violent.

It is 2010, and Joe Schmoe has been charged with assault. The physical evidence supporting his guilt is overwhelming and he pleads guilty. In preparation for his sentencing hearing, Joe's lawyer asks him to undergo a series of genetic tests to determine whether he carries any of four genetic mutations that have been associated in research literature with violent behavior. The tests, while controversial, show that Joe's DNA does, in fact, contain all four mutations. Based on these results, Joe's lawyer will argue that Joe should be sent to a psychiatric facility rather than to state prison. He claims that because Joe's genetic status predisposed him to this violent act, it would be unfair to sentence him as a criminal for behavior over which he had essentially no control.

Discussion Questions:

- If you were the judge at Joe's sentencing hearing, how, if at all, would the results of this controversial genetic test influence your decision?

- How would your decision be influenced if Joe had only 1 of the 4 mutations associated with violent behavior?

- What would be your decision if Joe was shown to suffer from a mental illness such as schizophrenia? How come?

- If Joe gets sent to prison and tries to get released on parole fifteen years later, should the fact that he may have a genetic predisposition to violent behavior be used to keep him in prison, even if his behavior has been consistently good during his incarceration?

- In the future, should all newborn babies be screened to determine if they have genetic mutations that could be linked to violent behavior? How come?

- What if a medication became available to treat people with these mutations?

Last updated: March 30, 2012

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Life Sci Soc Policy

- v.9; 2013 Dec

Perceptions of nature, nurture and behaviour

Mairi levitt.

Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religious Studies, Lancaster University, County South, Lancaster, LA1 4YL UK

Trying to separate out nature and nurture as explanations for behaviour, as in classic genetic studies of twins and families, is now said to be both impossible and unproductive. In practice the nature-nurture model persists as a way of framing discussion on the causes of behaviour in genetic research papers, as well as in the media and lay debate. Social and environmental theories of crime have been dominant in criminology and in public policy while biological theories have been seen as outdated and discredited. Recently, research into genetic variations associated with aggressive and antisocial behaviour has received more attention in the media. This paper explores ideas on the role of nature and nurture in violent and antisocial behaviour through interviews and open-ended questionnaires among lay publics. There was general agreement that everybody’s behaviour is influenced to varying degrees by both genetic and environmental factors but deterministic accounts of causation, except in exceptional circumstances, were rejected. Only an emphasis on nature was seen as dangerous in its consequences, for society and for individuals themselves. Whereas academic researchers approach the debate from their disciplinary perspectives which may or may not engage with practical and policy issues, the key issue for the public was what sort of explanations of behaviour will lead to the best outcomes for all concerned.

Trying to separate out nature and nurture as explanations for behaviour, as in classic genetic studies of twins and families, is now said to be both impossible and unproductive. The nature-nurture debate is declared to be officially redundant by social scientists and scientists, ‘outdated, naive and unhelpful’ (Craddock, 2011 , p.637), ‘a false dichotomy’ (Traynor 2010 , p.196). Geneticists argue that nature and nurture interact to affect behaviour through complex and not yet fully understood ways, but, in practice, the debate continues 1 . Research papers by psychologists and geneticists still use the terms nature and nurture, or genes and environment, to consider their relative influences on, for example, temperament and personality, childhood obesity and toddler sleep patterns (McCrae et al., 2000 ; Anderson et al., 2007 ; Brescianini, 2011 ). These papers separate out and quantify the relative influences of nature/genes and nurture/environment. These papers might be taken to indicate how individuals acquire their personality traits or toddlers acquire their sleep patterns; part is innate or there at birth and part is acquired after birth due to environmental influences. The findings actually refer to technical heritability which is, ‘the proportion of phenotypic variation attributable to genetic differences between individuals’ (Keller, 2010 , p.57). In practice, as Keller illustrates, there is ‘slippage’ between heritability, meaning a trait being biologically transmissible, and technical heritability. This is not simply a mistake made by the media or ‘media hype’ but is, she argues, ‘almost impossible to avoid’ (ibid, p.71).

While researchers are aware of the complexity of gene-environment interaction, the ‘nature and nurture’ model persists as a simple way of framing discussion on the causes of behaviours. It is also a site of struggle between (and within) academic disciplines and, through influence on policy, has consequences for those whose behaviours are investigated. There is general agreement between social scientists and geneticists about the past abuses of genetics but disagreement over whether it will be possible for the new behavioural genetics to avoid discrimination and eugenic practices, and about the likely benefits that society will gain from this research (Parens et al. 2006 , xxi). In a special issue of the American Journal of Sociology ‘Exploring genetics and social structure’, Bearman considers the reasons why sociologists are concerned about genetic effects on behaviour; first they see it as legitimating existing societal arrangements, which assumes that ‘genetic’ is unchangeable. Second, if sociologists draw on genetic research it contaminates the sociological enterprise and, third, whatever claims are made to the contrary, it is a eugenicist project (Bearman, 2008 , vi). As we will see all these concerns were expressed by the publics in this study. Policy makers and publics are interested in explaining problem behaviour in order to change/control it, not in respecting disciplinary boundaries, and will expect the role of genetics to be considered alongside social factors. 2