Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: Theories of Motivation

Chapter Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- Understand the role of motivation in determining employee performance.

- Classify the basic needs of employees.

- Describe how fairness perceptions are determined and consequences of these perceptions.

- Understand the importance of rewards and punishments.

- Apply motivation theories to analyze performance problems.

Introduction

The challenges and motivators in a post pandemic world..

The world is becoming progressively more digital with every passing year, so today’s workforce looks a lot different than it did 25 years ago. This progression, expedited by the global pandemic of Covid19, presents new challenges that today’s employers must learn to navigate to motivate their teams, prevent employee burnout and minimize turnover.

To understand and overcome the challenges in motivating today’s workforce, especially companies with significant numbers of non-desk workers, we must understand both the challenges and the motivators of new age, digital employees.

Let’s start with the challenges.

The top challenges chosen by the vast majority of employers

A. Building a great employee experience

1.Listen to people. Ensure that employees have a means of communication. Many non-desk workers are not connected to the company in a way that allows two-way communication.

2.Get feedback from surveys and focus groups, then implement change if need be. Keep an open channel of communication so that employees feel connected. Be committed to employee development and growth.

3.Equip and enable managers to support their teams. Creating a positive employee experience goes a long way with employee engagement and motivation.

B. Creating calm and reassurance in periods of turbulence

1.We can all agree that the world has been in a period of turbulence over the past two years. As a leader in an organization, you must pause and breathe . Managers can unintentionally pass their stress onto other employees.

2.Do the research and prevent the spread of misinformation. Speak clearly and confidently to your teams and colleagues so that you appear to have control over the situation. Transparency will create trust and go a long way in calming the workforce.

C. Fighting burnout

1.Let’s talk about the ever-elusive fight against burnout. It’s easy to understand that the outside stressors of everyday life during and after a pandemic paired with the daily stressors of work are enough to burn anyone out. More than 70% of employees reported feeling burnt out over the past year, making history (Forbes.com).

2.It’s never been more critical than it is now to tackle feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion. The key to avoiding burnout is getting in front of it, as it is much easier to prevent burnout than reverse it.

D. Turnover and letting employees go

1.Turnover tends to be a result of a poor approach to the above challenges. It’s no secret that the cost of turnover is high, estimated at 1.5 – 2 times an employee’s salary and $1,500 per hourly employee (builtin.com).

Therefore, organizations should actively avoid turnover by putting into place best practices and implementing a solid plan to tackle the above challenges.

E. Retaining top talent

1.With the cost of turnover being so high, retaining top talent is a priority . The key here is employee engagement, so ask questions to gain insight on employees to instill the correct development and training programs.

Weekly one-on-one meetings with department heads or managers are an excellent way to ask questions and get to know these individuals. Including all employees in the communication loop creates an atmosphere of teamwork and ensures that everyone’s efforts are appreciated.

2.Create on-the-job learning opportunities, whether significant or small. Vary learning experiences and provide insightful feedback that is constructive and accompanied by manageable action steps.

F. Communicating effectively

These challenges arguably have a common denominator – they’re a causal effect of poor communication. Therefore, effective communication could essentially eliminate or solve these challenges.

It seems simple, yet effective communication is complex and involves complex solutions. Everyone communicates differently. The good news is there are a plethora of companies specializing in making communications in the workforce easy.

According to Pew Research, 91% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 64 own a smartphone, making them far and away the most popular way to communicate. Due to this information, the most innovative and easiest way to reach employees and increase engagement would be to interact via the smartphone.

Employee engagement apps can simplify your workforce management system and workplace communication making it accessible for all employees, non-desk workers, remote and office workers alike. Some of these platforms include Artificial Intelligence which provides highly structured communications.

These communications give the right message to the right person at the right time, prevent spray and pray messaging, and the chaos and lack of usage that reply-all messaging creates.

Now that the challenges have been addressed, let’s understand the motivators.

Why is it that, on some days, it can feel harder than others to get up when your alarm goes off, do your workout, complete a work or school assignment, or make dinner for your family?

Motivation (or a lack thereof) is usually behind why we do the things that we do.

There are different types of motivation, and as it turns out, understanding why you are motivated to do the things that you do can help you keep yourself motivated — and can help you motivate others.

There are two types of motivator categories in a company’s culture, intrinsic and extrinsic.

What Is Intrinsic Motivation?

When you’re intrinsically motivated, your behavior is motivated by your internal desire to do something for its own sake — for example, your personal enjoyment of an activity, or your desire to learn a skill because you’re eager to learn.

Examples of intrinsic motivation could include:

- Reading a book because you enjoy the storytelling

- Exercising because you want to relieve stress

- Cleaning your home because it helps you feel organized

What Is Extrinsic Motivation?

When you’re extrinsically motivated, your behavior is motivated by an external factor pushing you to do something in hopes of earning a reward — or avoiding a less-than-positive outcome.

Examples of extrinsic motivation could include:

- Reading a book to prepare for a test

- Exercising to lose weight

- Cleaning your home to prepare for visitors coming over

If you have a job, and you must complete a project, you’re probably extrinsically motivated — by your manager’s praise or a potential raise or commission — even if you enjoy the project while you’re doing it. If you’re in school, you’re extrinsically motivated to learn a foreign language because you’re being graded on it — even if you enjoy practicing and studying it.

So, intrinsic motivation is good, and extrinsic motivation is good. The key is to figure out why you — and your team — are motivated to do things and encouraging both types of motivation.

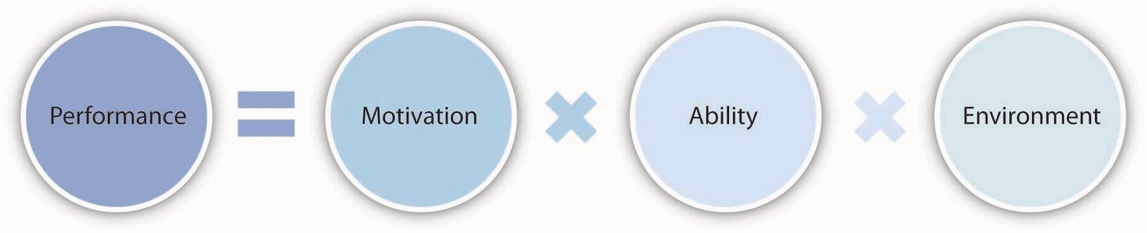

If someone is not performing well, what could be the reason? According to this equation, motivation, ability, and environment are the major influences over employee performance.

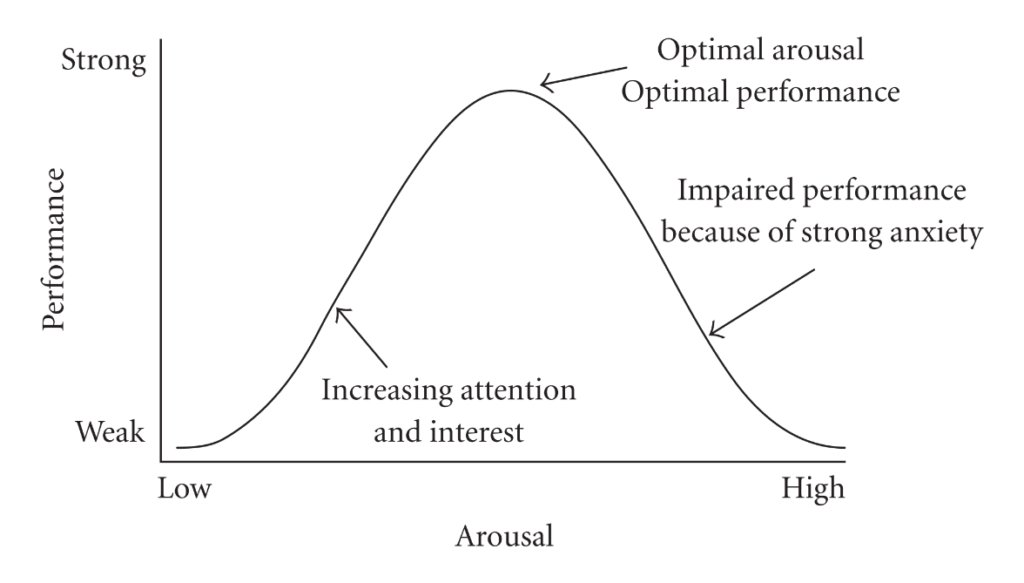

Motivation is one of the forces that lead to performance. Motivation is defined as the desire to achieve a goal or a certain performance level, leading to goal-directed behaviour. When we refer to someone as being motivated, we mean that the person is trying hard to accomplish a certain task. Motivation is clearly important if someone is to perform well; however, it is not sufficient. Ability —or having the skills and knowledge required to perform the job—is also important and is sometimes the key predictor of effectiveness. Finally, environmental factors such as having the resources, information, and support to perform well are critical to determine performance. At different times, one of these three factors may be the key to high performance. For example, for an employee sweeping the floor, motivation may be the most important factor that determines performance. In contrast, even the most motivated individual would not be able to successfully design a house without the necessary talent involved in building quality homes. Being motivated is not the same as being a high performer and is not the sole reason why people perform well, but it is nevertheless a key influence over our performance level.

So, what motivates people? Why do some employees try to reach their targets and pursue excellence while others merely show up at work and count the hours? As with many questions involving human beings, the answer is anything but simple. Instead, there are several theories explaining the concept of motivation. We will discuss motivation theories under two categories: need-based theories and process theories.

5.1 A Motivating Place to Work: The Case of Rogers Communications Inc

Rogers Communications Inc has been identified as one of Canada’s 100 top employers by Media Corp Canada, who investigate Canadian companies based on 8 criteria: (1) Physical Workplace; (2) Work Atmosphere & Social; (3) Health, Financial & Family Benefits; (4) Vacation & Time Off; (5) Employee Communications; (6) Performance Management; (7) Training & Skills Development; and (8) Community Involvement. Employers are compared to other organizations in their field to determine which offers the most progressive and forward-thinking programs (Media Corp Canada,2019).

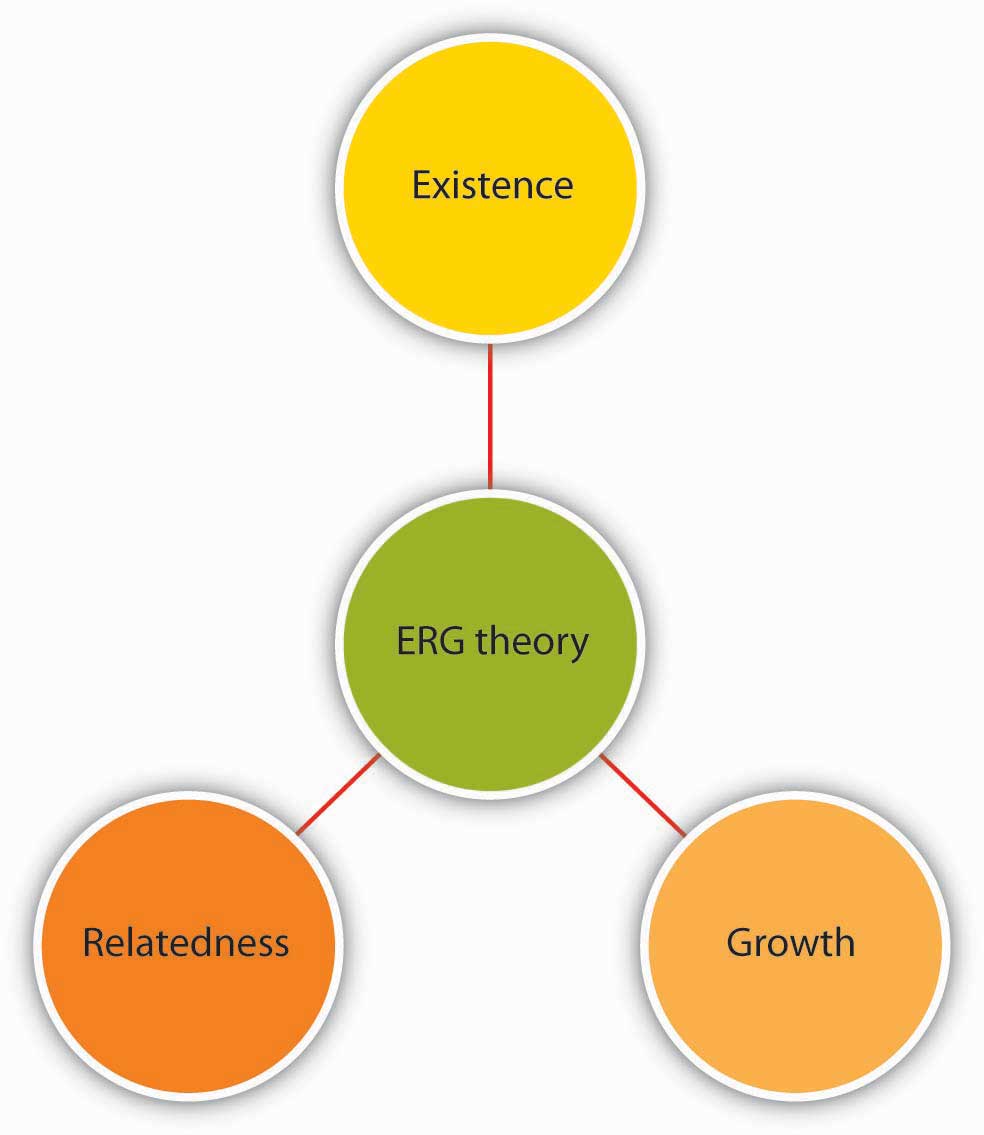

5.2 Need-Based Theories of Motivation

Early researchers thought that employees try hard and demonstrate behaviour to satisfy their own personal needs. For example, an employee who is always walking around the office talking to people may have a need for companionship, and his or her behaviour may be a way of satisfying this need. At the time, researchers developed theories to understand what people need. Two theories may be placed under this category: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and McClelland’s acquired-needs theory.

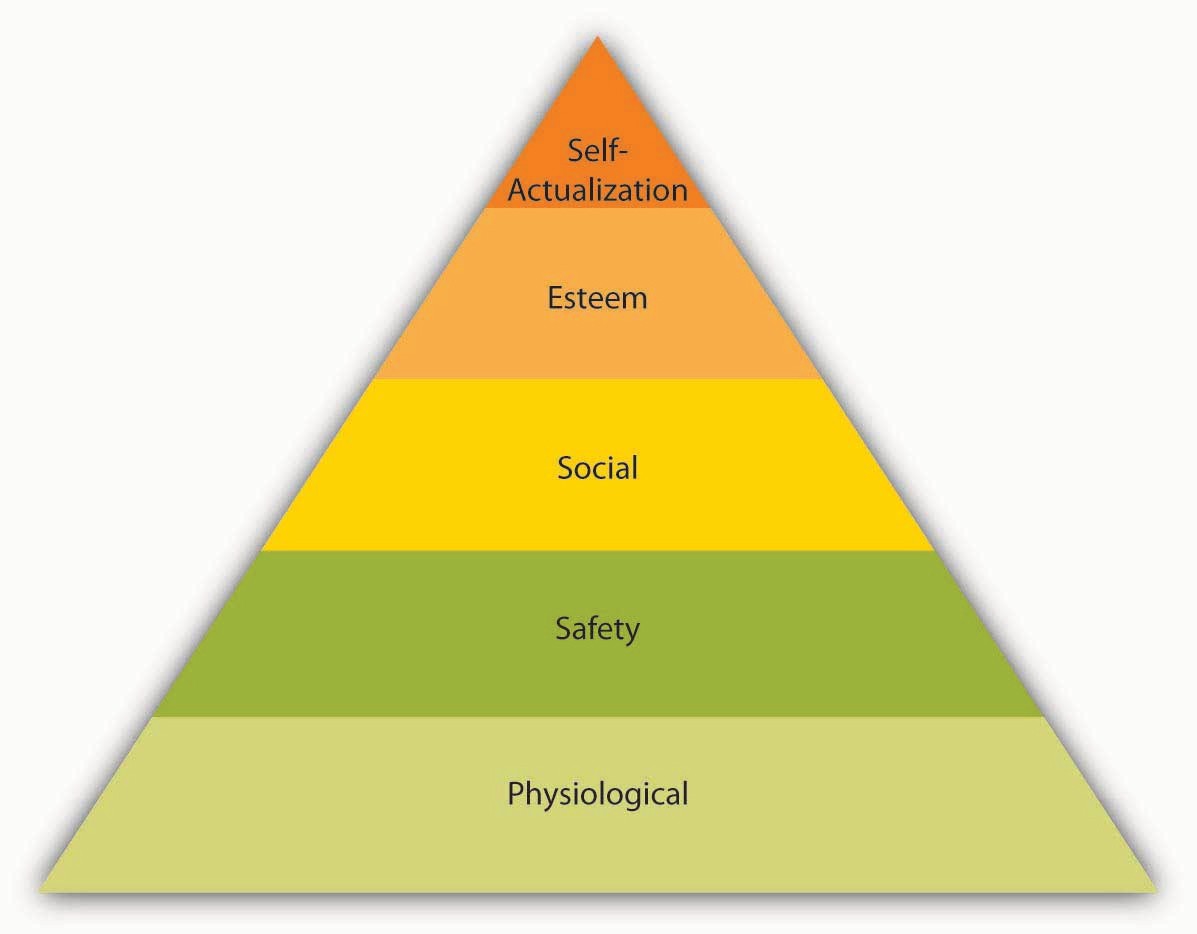

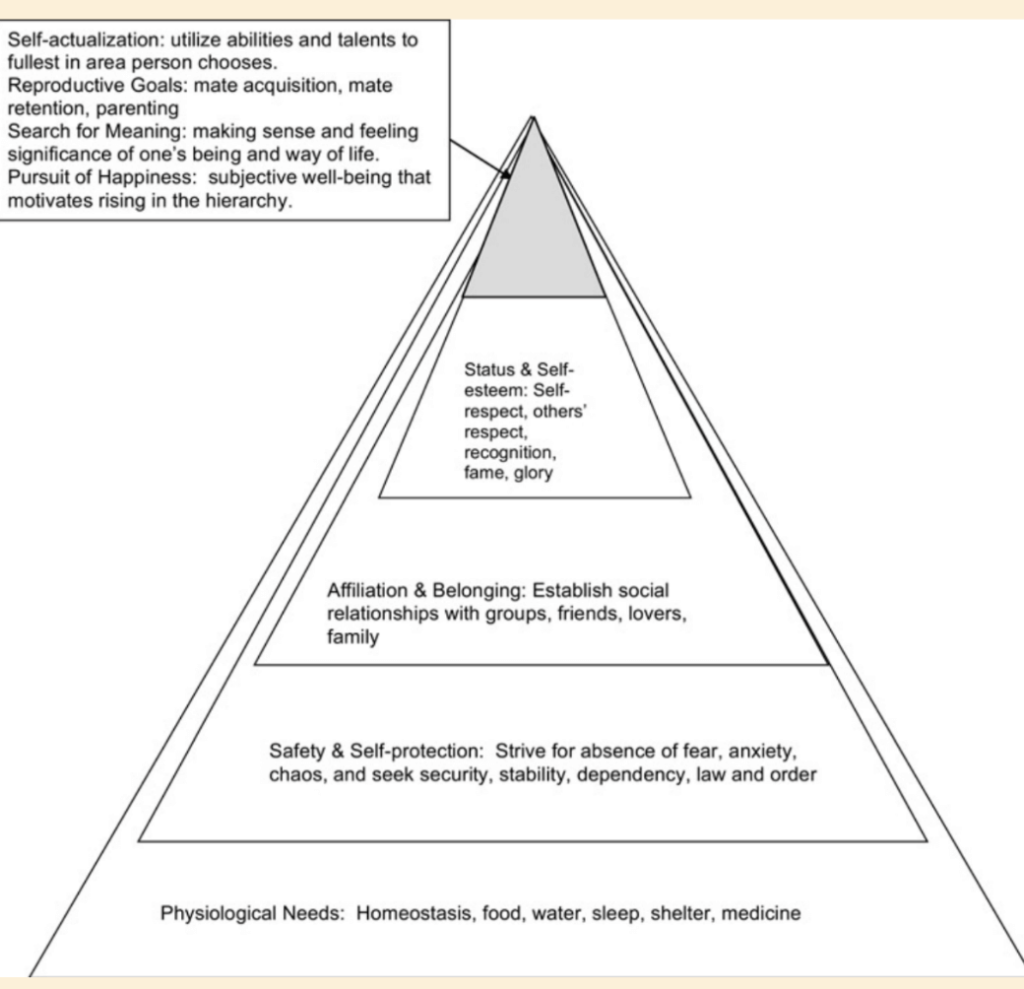

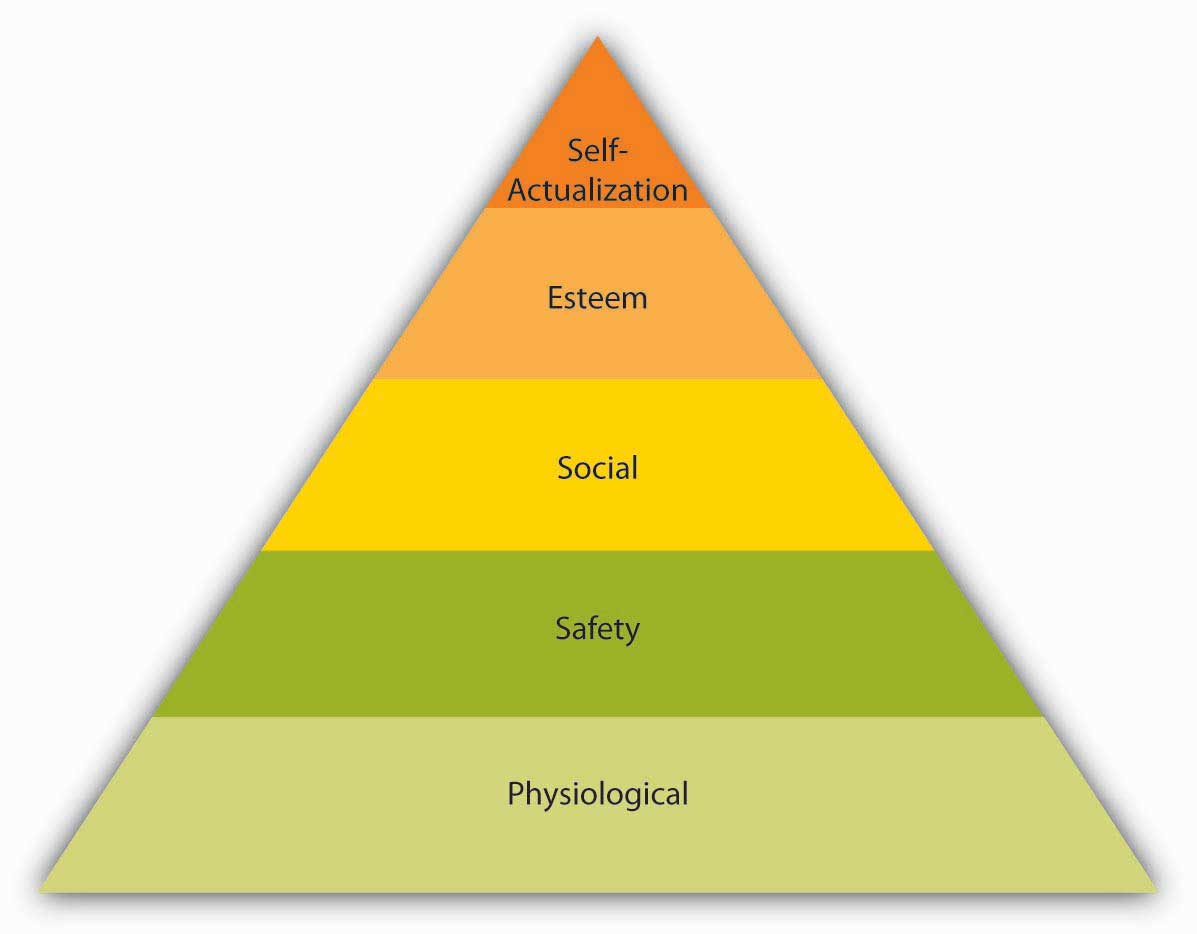

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Abraham Maslow is among the most prominent psychologists of the twentieth century. His hierarchy of needs is an image familiar to most business students and managers. The theory is based on a simple idea: human beings have needs that are ranked (Maslow, 1943; Maslow, 1954). There are some needs that are basic to all human beings, and in their absence nothing else matters. As we satisfy these basic needs, we start looking to satisfy higher order needs. In other words, once a lower-level need is satisfied, it no longer serves as a motivator.

The most basic of Maslow’s needs are physiological needs . Physiological needs refer to the need for food, water, and other biological needs. These needs are basic because when they are lacking, the search for them may overpower all other urges. Imagine being very hungry. At that point, all your behaviour may be directed at finding food. Once you eat, though, the search for food ceases and the promise of food no longer serves as a motivator. Once physiological needs are satisfied, people tend to become concerned about safety needs . Are they free from the threat of danger, pain, or an uncertain future? On the next level up, social needs refer to the need to bond with other human beings, be loved, and form lasting attachments with others. In fact, attachments, or lack of them, are associated with our health and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). The satisfaction of social needs makes esteem needs more salient. Esteem needs refer to the desire to be respected by one’s peers, feel important, and be appreciated. Finally, at the highest level of the hierarchy, the need for self-actualization refers to “becoming all you are capable of becoming.” This need manifests itself by the desire to acquire new skills, take on new challenges, and behave in a way that will lead to the attainment of one’s life goals.

How can an organization satisfy its employees’ various needs? In the long run, physiological needs may be satisfied by the person’s paycheck, but it is important to remember that pay may satisfy other needs such as safety and esteem as well. Providing generous benefits that include health insurance and company-sponsored retirement plans, as well as offering a measure of job security, will help satisfy safety needs. Social needs may be satisfied by having a friendly environment and providing a workplace conducive to collaboration and communication. Company picnics and other social get-togethers may also be helpful if most employees are motivated primarily by social needs (but may cause resentment if they are not and if they must sacrifice a Sunday afternoon for a company picnic). Providing promotion opportunities at work, recognizing a person’s accomplishments verbally or through more formal reward systems, and conferring job titles that communicate to the employee that one has achieved high status within the organization are among the ways of satisfying esteem needs. Finally, self-actualization needs may be satisfied by the provision of development and growth opportunities on or off the job, as well as by work that is interesting and challenging. By making the effort to satisfy the different needs of each employee, organizations may ensure a highly motivated workforce.

Acquired-Needs Theory

Among the need-based approaches to motivation, David McClelland’s acquired-needs theory is the one that has received the greatest amount of support. According to this theory, individuals acquire three types of needs because of their life experiences. These needs are the need for achievement, the need for affiliation, and the need for power . All individuals possess a combination of these needs, and the dominant needs are thought to drive employee behaviour.

McClelland used a unique method called the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to assess the dominant need (Spangler, 1992). This method entails presenting research subjects an ambiguous picture and asking them to write a story based on it. The instructions will be: “Take a look at the following picture. Who is this person? What is she doing? Why is she doing it?” The story you tell about the woman in the picture would then be analyzed by trained experts. The idea is that the stories the photo evokes would reflect how the mind works and what motivates the person. ( Apperception : the mental process by which a person makes sense of an idea by assimilating it to the body of ideas he or she already possesses. For example: a perception would be seeing a dog and thinking “There is a dog.” Apperception would be seeing a dog and thinking “That dog looks like the one that bit my friend Andres”)

If the story you come up with contains themes of success, meeting deadlines, or coming up with brilliant ideas, you may be high in need for achievement. Those who have high need for achievement have a strong need to be successful. As children, they may be praised for their hard work, which forms the foundations of their persistence (Mueller & Dweck, 1998). As adults, they are preoccupied with doing things better than they did in the past. These individuals are constantly striving to improve their performance. They relentlessly focus on goals, particularly stretch goals that are challenging in nature (Campbell, 1982).

Are individuals who are high in need for achievement effective managers? Because of their success in lower-level jobs where their individual contributions matter the most, those with high need for achievement are often promoted to higher level positions (McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982). However, a high need for achievement has significant disadvantages in management positions. Management involves getting work done by motivating others.

If the story you created in relation to the picture you are analyzing contains elements of making plans to be with friends or family, you may have a high need for affiliation . Individuals who have a high need for affiliation want to be liked and accepted by others. When given a choice, they prefer to interact with others and be with friends (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991).

Finally, if your story contains elements of getting work done by influencing other people or the desire to make an impact on the organization, you may have a high need for power . Those with a high need for power want to influence others and control their environment. A need for power may in fact be a destructive element in relationships with colleagues if it takes the form of seeking and using power for one’s own good and prestige.

5.3 Process-Based Theories

A separate stream of research views motivation as something more than action aimed at satisfying a need. Instead, process-based theories view motivation as a logical process. Individuals analyze their work environment, develop thoughts and feelings, and react in certain ways. Process theories attempt to explain the thought processes of individuals who demonstrate motivated behaviour. Under this category, we will review equity theory, expectancy theory, and reinforcement theory.

Equity Theory

Imagine that you are paid $10 an hour working as an office assistant. You have held this job for 6 months. You are very good at what you do, you come up with creative ways to make things easier around you, and you are a good colleague who is willing to help others. You stay late when necessary and are flexible if requested to change hours. Now imagine that you found out they are hiring another employee who is going to work with you, who will hold the same job title, and who will perform the same type of tasks. This person has more advanced computer skills, but it is unclear whether these will be used on the job. The starting pay for this person will be $14 an hour. How would you feel? Would you be as motivated as before, going above and beyond your duties?

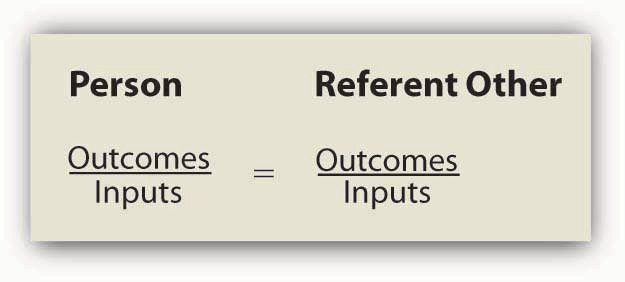

If your reaction to this scenario is along the lines of “this would be unfair,” your behaviour may be explained using equity theory (Adams, 1965). According to this theory, individuals are motivated by a sense of fairness in their interactions. Moreover, our sense of fairness is a result of the social comparisons we make. Specifically, we compare our inputs and outcomes with other people’s inputs and outcomes. We perceive fairness if we believe that the input-to-outcome ratio we are bringing into the situation is like the input-to-outcome ratio of a comparison person, or a referent . Perceptions of inequity create tension within us and drive us to action that will reduce perceived inequity.

What Are Inputs and Outcomes?

Inputs are the contributions people feel they are making to the environment. In the previous example, the person’s hard work; loyalty to the organization; amount of time with the organization; and level of education, training, and skills may have been relevant inputs. Outcomes are the perceived rewards someone can receive from the situation. For the hourly wage employee in our example, the $10 an hour pay rate was a core outcome. There may also be other, more peripheral outcomes, such as acknowledgment or preferential treatment from a manager. In the prior example, however, the person may reason as follows: I have been working here for 6 months. I am loyal, and I perform well (inputs). I am paid $10 an hour for this (outcomes). The new person does not have any experience here (referent’s inputs) but will be paid $14 an hour. This situation is unfair.

Who is the Referent?

The referent other may be a specific person as well as a category of people. Referents should be comparable to us—otherwise the comparison is not meaningful. It would be pointless for a student worker to compare himself to the CEO of the company, given the differences in inputs and outcomes. Instead, individuals may compare themselves to someone performing similar tasks within the same organization or, in the case of a CEO, a different organization.

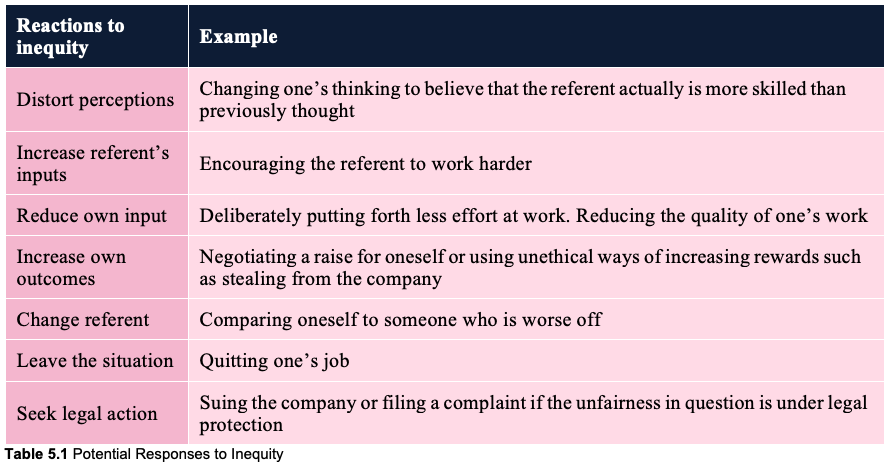

Reactions to Unfairness

The theory outlines several potential reactions to perceived inequity. Oftentimes, the situation may be dealt with perceptually by altering our perceptions of our own or the referent’s inputs and outcomes . For example, we may justify the situation by downplaying our own inputs (I don’t really work very hard on this job), valuing our outcomes more highly (I am gaining valuable work experience, so the situation is not that bad), distorting the other person’s inputs (the new hire really is more competent than I am and deserves to be paid more), or distorting the other person’s outcomes (she gets $14 an hour but will have to work with a lousy manager, so the situation is not unfair).

Another option would be to have the referent increase inputs . If the other person brings more to the situation, getting more out of the situation would be fair. If that person can be made to work harder or work on more complicated tasks, equity would be achieved.

The person experiencing a perceived inequity may also reduce inputs or attempt to increase outcomes . If the lower paid person puts forth less effort, the perceived inequity would be reduced. Research shows that people who perceive inequity reduce their work performance or reduce the quality of their inputs (Carrell & Dittrich, 1978; Goodman & Friedman, 1971). Increasing one’s outcomes can be achieved through legitimate means such as negotiating a pay raise. At the same time, research shows that those feeling inequity sometimes resort to stealing to balance the scales (Greenberg, 1993).

Other options include changing the comparison person (e.g., others doing similar work in different organizations are paid only minimum wage) and leaving the situation by quitting (Schmidt & Marwell, 1972). Sometimes it may be necessary to consider taking legal action as a potential outcome of perceived inequity. For example, if an employee finds out the main reason behind a pay gap is gender related, the person may react to the situation by taking legal action because sex discrimination in pay is illegal in Canada.

Fairness Beyond Equity: Procedural and Interactional Justice

Equity theory looks at perceived fairness as a motivator. However, the way equity theory defines fairness is limited to fairness of rewards. Starting in the 1970s, research on workplace fairness began taking a broader view of justice. Equity theory deals with outcome fairness, and therefore it is considered to be a distributive justice theory.

Distributive justice refers to the degree to which the outcomes received from the organization are perceived to be fair. Two other types of fairness have been identified: procedural justice and interactional justice.

Let’s assume that you just found out you are getting a promotion. Clearly, this is an exciting outcome and comes with a pay raise, increased responsibilities, and prestige. If you feel you deserve to be promoted, you will perceive high distributive justice (you getting this promotion is fair). However, you later found out upper management picked your name out of a hat! What would you feel? You might still like the outcome but feel that the decision-making process was unfair. If so, you are describing feelings of procedural justice.

Procedural justice refers to the degree to which fair decision-making procedures are used to arrive at a decision. People do not care only about reward fairness. They also expect decision-making processes to be fair. In fact, research shows that employees care about the procedural justice of many organizational decisions, including layoffs, employee selection, surveillance of employees, performance appraisals, and pay decisions (Alge, 2001; Bauer et al., 1998; Kidwell, 1995). People also tend to care more about procedural justice in situations in which they do not get the outcome they feel they deserve (Brockner & Wiesenfeld, 1996). If you did not get the promotion and later discovered that management chose the candidate by picking names out of a hat, how would you feel? This may be viewed as adding insult to injury. When people do not get the rewards they want, they tend to hold management responsible if procedures are not fair (Brockner et al., 2007).

Now let’s imagine the moment your boss told you that you are getting a promotion. Your manager’s exact words were, “Yes, we are giving you the promotion. The job is so simple that we thought even you can handle it.” Now what is your reaction? The feeling of unfairness you may now feel is explained by interactional justice. Interactional justice refers to the degree to which people are treated with respect, kindness, and dignity in interpersonal interactions. We expect to be treated with dignity by our peers, supervisors, and customers. When the opposite happens, we feel angry. Even when faced with negative outcomes such as a pay cut, being treated with dignity and respect serves as a buffer and alleviates our stress (Greenberg, 2006).

Expectancy Theory

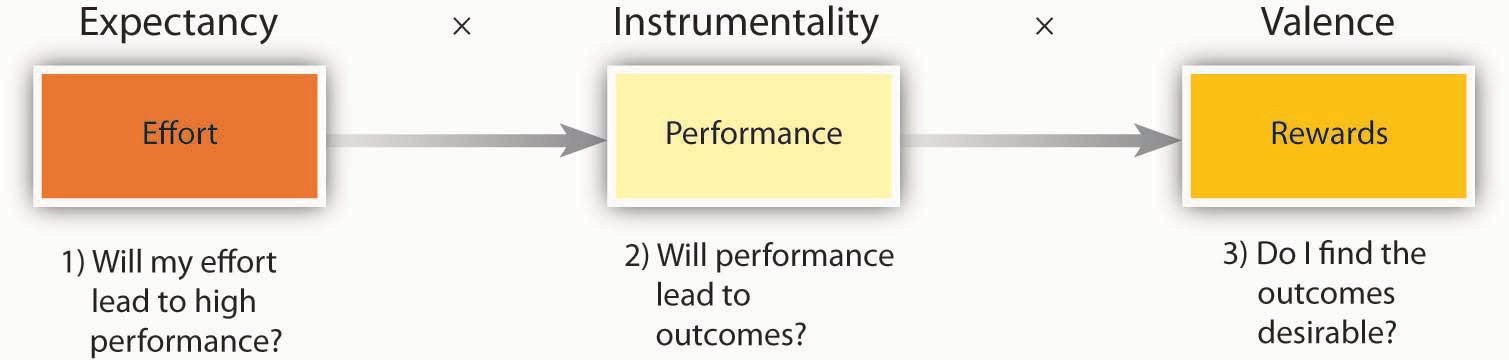

The expectancy theory of motivation, or the expectancy theory, is the belief that an individual chooses their behaviors based on what they believe leads to the most beneficial outcome. The individual’s motivation to put forth more or less effort is determined by a rational calculation in which individuals evaluate their situation (Porter & Lawler, 1968; Vroom, 1964).

This theory is dependent on how much value a person places on different motivations. This results in a decision they expect to give them the highest return for their efforts.

According to this theory, individuals ask themselves three questions.

The first question is whether the person believes that high levels of effort will lead to outcomes of interest, such as performance or success. This perception is labeled expectancy . For example, do you believe that the effort you put forth in a class is related to performing well in that class? If you do, you are more likely to put forth effort.

The second question is the degree to which the person believes that performance is related to subsequent outcomes, such as rewards. This perception is labeled instrumentality . For example, do you believe that getting a good grade in the class is related to rewards such as getting a better job, or gaining approval from your instructor, or from your friends or parents? If you do, you are more likely to put forth effort.

Finally, individuals are also concerned about the value of the rewards awaiting them as a result of performance. The anticipated satisfaction that will result from an outcome is labeled valence . For example, do you value getting a better job, or gaining approval from your instructor, friends, or parents? If these outcomes are desirable to you, your expectancy and instrumentality is high, and you are more likely to put forth effort.

Expectancy theory is a well-accepted theory that has received a lot of research attention (Heneman & Schwab, 1972; Van Eerde & Thierry, 1996). It is simple and intuitive. Consider the following example. Let’s assume that you are working in the concession stand of a movie theater. You have been selling an average of 100 combos of popcorn and soft drinks a day. Now your manager asks you to increase this number to 300 combos a day. Would you be motivated to try to increase your numbers? Here is what you may be thinking:

- Expectancy: is the belief that if an individual raises their efforts, their reward may rise as well. Expectancy is what motivates a person to gather the right tools to get the job done, which could include raw materials and resources, skills to perform the job and support and information from supervisors. Can I do it? If I try harder, can I really achieve this number? Is there a link between how hard I try and whether I reach this goal or not? If you feel that you can achieve this number if you try, you have high expectancy.

- Instrumentality: is the belief that the reward you receive depends on your performance in the workplace. What is in it for me? What is going to happen if I reach 300? What are the outcomes that will follow? Are they going to give me a 2% pay raise? Am I going to be named the salesperson of the month? Am I going to receive verbal praise from my manager? If you believe that performing well is related to certain outcomes, instrumentality is high.

- Valence: is the importance you place on the expected outcome of your performance. This often depends on your individual needs, goals, values and sources of motivation. For example, if you expect to be one of the top performers on your team, you may place high importance on achieving that goal, even if others don’t expect you to achieve this level of performance. How do I feel about the outcomes in question? Do I feel that a 2% pay raise is desirable? Do I find being named the salesperson of the month attractive? Do I think that being praised by my manager is desirable? If your answers are yes, valence is positive. In contrast, if you find the outcomes undesirable (you definitely do not want to be named the salesperson of the month because your friends would make fun of you), valence is negative.

If your answers to all three questions are affirmative—you feel that you can do it, you will get an outcome if you do it, and you value the reward—you are more likely to be motivated to put forth more effort toward selling more combos.

As a manager, how can you motivate employees? In fact, managers can influence all three perceptions (Cook, 1980).

Influencing Expectancy Perceptions

Employees may not believe that their effort leads to high performance for a multitude of reasons. First, they may not have the skills, knowledge, or abilities to successfully perform their jobs. The answer to this problem may be training employees or hiring people who are qualified for the jobs in question. Second, low levels of expectancy may be because employees may feel that something other than effort predicts performance, such as political behaviours on the part of employees. If employees believe that the work environment is not conducive to performing well (resources are lacking or roles are unclear), expectancy will also suffer. Therefore, clearing the path to performance and creating an environment in which employees do not feel restricted will be helpful. Finally, some employees may perceive little connection between their effort and performance level because they have an external locus of control, low self-esteem, or other personality traits that condition them to believe that their effort will not make a difference. In such cases, providing positive feedback and encouragement may help motivate employees.

Reinforcement Theory

Reinforcement theory is based on a simple idea that may be viewed as common sense. Beginning at infancy we learn through reinforcement. If you have observed a small child discovering the environment, you will see reinforcement theory in action. When the child discovers that twisting and turning a tap leads to water coming out and finds this outcome pleasant, he is more likely to repeat the behaviour. If he burns his hand while playing with hot water, the child is likely to stay away from the faucet in the future.

Despite the simplicity of reinforcement, how many times have you seen positive behaviour ignored, or worse, negative behaviour rewarded? In many organizations, this is a familiar scenario. People go above and beyond the call of duty, yet their actions are ignored or criticized. People with disruptive habits may receive no punishments because the manager is afraid of the reaction the person will give when confronted. Problem employees may even receive rewards such as promotions so they will be transferred to a different location and become someone else’s problem.

Reinforcement Interventions

How does a leader modify a team members’ behaviour so that the team member becomes more productive. ?

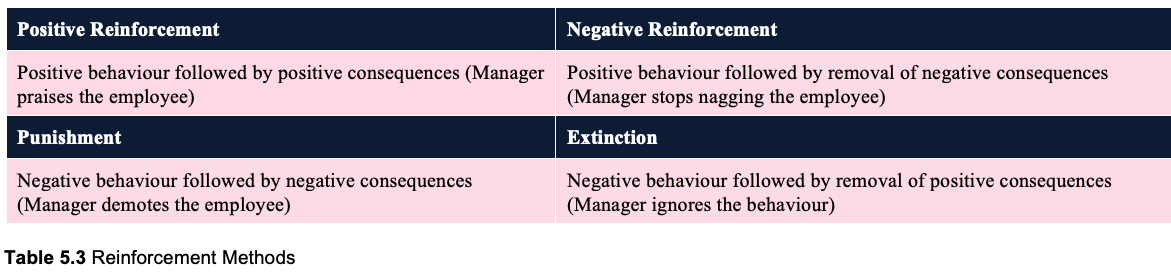

Reinforcement theory describes four interventions to modify employee behaviour. Two of these (Positive and Negative reinforcement) are methods of increasing the frequency of desired behaviours, while the remaining two (Punishment and Extinction) are methods of reducing the frequency of undesired behaviours.

Positive reinforcement is a method of increasing the desired behaviour (Beatty & Schneier, 1975). Positive reinforcement involves making sure that behaviour is met with positive consequences. For example, praising an employee for treating a customer respectfully is an example of positive reinforcement. If the praise immediately follows the positive behaviour, the employee will see a link between the behaviour and positive consequences and will be motivated to repeat similar behaviours.

Negative reinforcement is also used to increase the desired behaviour. Negative reinforcement involves removal of unpleasant outcomes once desired behaviour is demonstrated. Nagging an employee to complete a report is an example of negative reinforcement. The negative stimulus in the environment will remain present until positive behaviour is demonstrated. The problem with negative reinforcement is that the negative stimulus may lead to unexpected behaviours and may fail to stimulate the desired behaviour. For example, the person may start avoiding the manager to avoid being nagged.

Extinction is used to decrease the frequency of negative behaviours. Extinction is the removal of rewards following negative behaviour. Sometimes, negative behaviours are demonstrated because they are being inadvertently rewarded. For example, it has been shown that when people are rewarded for their unethical behaviours, they tend to demonstrate higher levels of unethical behaviours (Harvey & Sims, 1978). Thus, when the rewards following unwanted behaviours are removed, the frequency of future negative behaviours may be reduced. For example, if a co-worker is forwarding unsolicited e-mail messages containing jokes, commenting and laughing at these jokes may be encouraging the person to keep forwarding these messages. Completely ignoring such messages may reduce their frequency.

Punishment is another method of reducing the frequency of undesirable behaviours. Punishment involves presenting negative consequences following unwanted behaviours. Giving an employee a warning for consistently being late to work is an example of punishment.

An inspiring speech for your reflection

Jon Fisher (born January 19, 1972) is an entrepreneur, investor, author, speaker, philanthropist and inventor. Fisher is known for a viral commencement speech at the University of San Francisco. Here is an excerpt.

5.4 Motivation in Action: The Case of Trader Joe’s

People in Hawaiian T-shirts. Delicious fresh fruits and vegetables. A place where parking is tight and aisles are tiny. A place where you will be unable to find half the things on your list but will go home satisfied. We are, of course, talking about Trader Joe’s (a privately held company), a unique grocery store headquartered in California and located in 22 states. By selling store-brand and gourmet foods at affordable prices, this chain created a special niche for itself. Yet the helpful employees who stock the shelves and answer questions are definitely key to what makes this store unique and helps it achieve twice the sales of traditional supermarkets.

Shopping here is fun and chatting with employees is a routine part of this experience. Employees are upbeat and friendly to each other and to customers. If you look lost, there is the definite offer of help. But somehow the friendliness does not seem scripted. Instead, if they see you shopping for big trays of cheese, they might casually inquire if you are having a party and then point to other selections. If they see you chasing your toddler, they are quick to tie a balloon to his wrist. When you ask them if they have any cumin, they get down on their knees to check the back of the aisle, with the attitude of helping a guest that is visiting their home. How does a company make sure its employees look like they enjoy being there to help others?

One of the keys to this puzzle is pay. Trader Joe’s sells cheap organic food, but they are not “cheap” when it comes to paying their employees. Employees, including part-timers, are among the best paid in the retail industry. Full-time employees earn an average of $40,150 in their first year and also earn average annual bonuses of $950 with $6,300 in retirement contributions. Store managers’ average compensation is $132,000. With these generous benefits and above-market wages and salaries, the company has no difficulty attracting qualified candidates.

But money only partially explains what energizes Trader Joe’s employees. They work with people who are friendly and upbeat. The environment is collaborative, so that people fill in for each other and managers pick up the slack when the need arises, including tasks like sweeping the floors. Plus, the company promotes solely from within, making Trader Joe’s one of few places in the retail industry where employees can satisfy their career aspirations. Employees are evaluated every 3 months and receive feedback about their performance.

Employees are also given autonomy on the job. They can open a product to have the customers try it and can be honest about their feelings toward different products. They receive on- and off-the-job training and are intimately familiar with the products, which enables them to come up with ideas that are taken seriously by upper management. In short, employees love what they do, work with nice people who treat each other well, and are respected by the company. When employees are treated well, it is no wonder they treat their customers well daily (Lewis, 2005; McGregor et al., 2004; Speizer, 2004).

5.5 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have reviewed the basic motivation theories that have been developed to explain motivated behaviour. Several theories view motivated behaviour as attempts to satisfy needs. Based on this approach, managers would benefit from understanding what people need so that the actions of employees can be understood and managed. Other theories explain motivated behaviour using the cognitive processes of employees. Employees respond to unfairness in their environment, they learn from the consequences of their actions and repeat the behaviours that lead to positive results, and they are motivated to exert effort if they see their actions will lead to outcomes that would get them desired rewards. None of these theories are complete on their own, but each theory provides us with a framework we can use to analyze, interpret, and manage employee behaviours in the workplace.

Organizational Behaviour Copyright © 2019 by Seneca College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Theories of Motivation

Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal, but, why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Is motivation an inherited trait or is motivation influenced by reinforcement and consequences that strengthen some behaviors and weaken others? Is the key to motivating learners a lesson plan that captures their interest and attention? In other words, is motivation something innate that we are born with that can be strengthened by reinforcers external to the learning task, or is it something interwoven with the learning process itself?

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Some motives are biological, like our need for food or water. However, the motives that we will be more interested in are more psychological. In general, we discuss motivation as being intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Video 6.1.1. Extrinsic vs Intrinsic Motivation explains the difference and provides examples of these types of motivation.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she often whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it. What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In addition, culture may influence motivation. For example, in collectivistic cultures, it is common to do things for your family members because the emphasis is on the group and what is best for the entire group, rather than what is best for any one individual (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). This focus on others provides a broader perspective that takes into account both situational and cultural influences on behavior; thus, a more nuanced explanation of the causes of others’ behavior becomes more likely. (You will learn more about collectivistic and individualistic cultures when you learn about social psychology.)

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts the results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

Think About It

Schools often use concrete rewards to increase adaptive behaviors. How might this be a disadvantage for students intrinsically motivated to learn? What are the educational implications of the potential for concrete rewards to diminish intrinsic motivation for a given task?

We would expect to see a shift from learning for the sake of learning to learning to earn some reward. This would undermine the foundation upon which traditional institutions of higher education are built. For a student motivated by extrinsic rewards, dependence on those may pose issues later in life (post-school) when there are not typically extrinsic rewards for learning.

Like motivation itself, theories of it are full of diversity. For convenience in navigating through the diversity, we have organized the theories around two perspectives about motion. The first set of theories focuses on the innateness of motivation. These theories emphasize instinctual or inborn needs and drives that influence our behavior. The second set of theories proposes cognition as the source of motivation. Individual motivation is influenced by thoughts, beliefs, and values. The variation in these theories is due to disagreement about which cognitive factors are essential to motivation and how those cognitive factors might be influenced by the environment.

Innate Motivation Theories

First, we will describe some early motivational theories that focus on innate needs and drives. Not all of these theories apply to the classroom, but learning about them will show you how different theorists have approached the issue of motivation. You are sure to find some elements of your own thinking about motivation in each of them. We will examine instinct theory, drive theory, and arousal theory as early explanations of motivation. We will also discuss the behavioral perspective on motivation and the deficiency-growth perspective, as exemplified by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

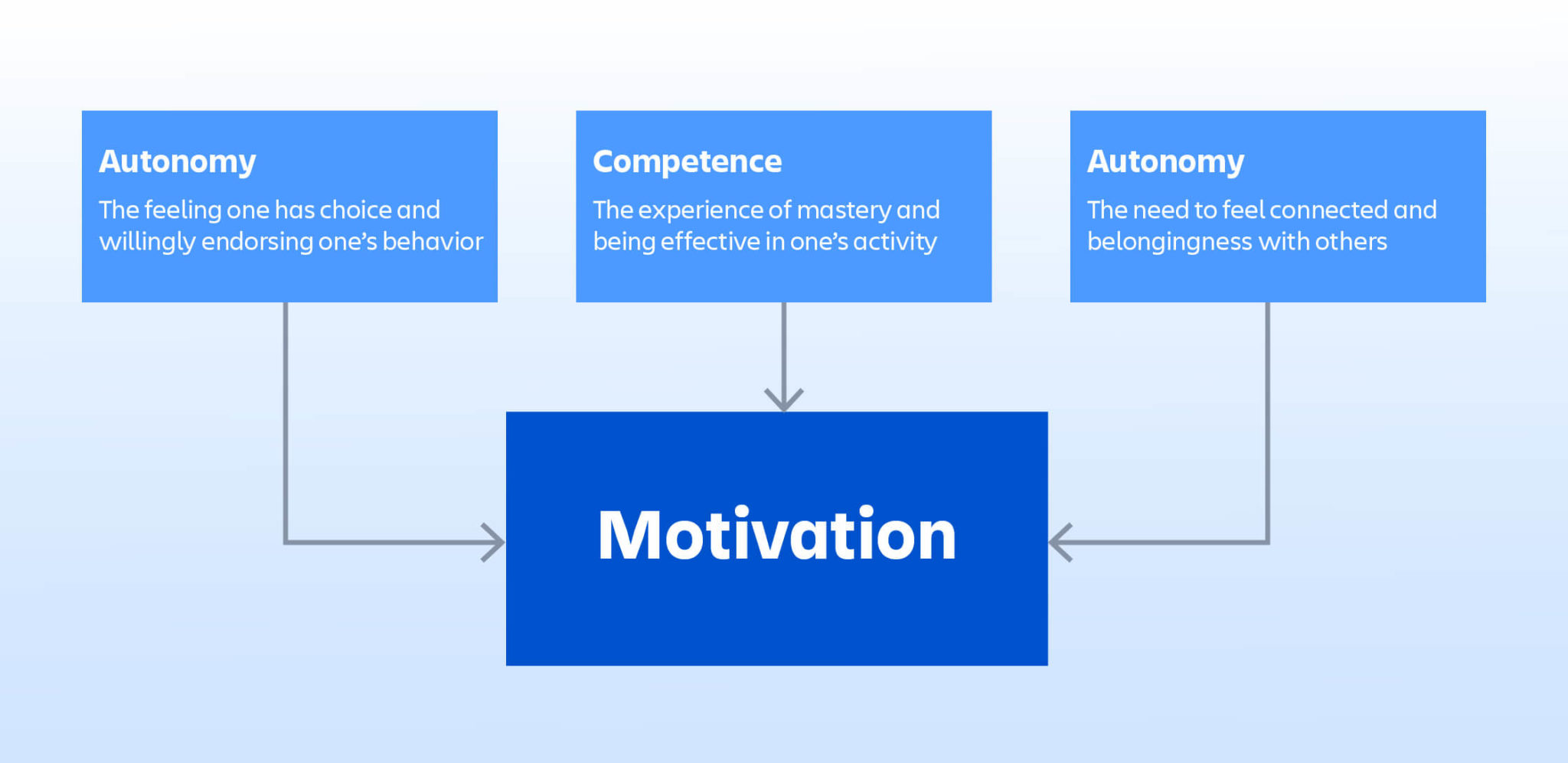

Cognitive Theories of Motivation

Cognitive theories of motivation assume that behavior is a result of cognitive processes. These theories presume that individuals are interpreting information and making decisions, not just acting on basic needs and drives. Cognitive motivation theories share strong ties with the cognitive and social learning theories that we discussed previously. We will examine several cognitive motivation theories: interest, attribution theory, expectancy-value theory, and self-efficacy theory. All emphasize that learners need to know, understand, and appreciate what they are doing in order to become motivated. Then, along with these cognitive motivation theories, we will examine a motivational perspective called self-determination theory, which attempts to reconcile cognitive theory’s emphasis on intrinsic motivation with more traditional notions of human needs and drives.

Video 6.1.2. Instincts, Arousal, Needs, Drives provides a brief overview of some of the major motivational theories.

Candela Citations

- Theories of Motivation . Authored by : Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by : Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from : . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Educational Psychology. Authored by : Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. Provided by : The Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/educationalpsychology. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Educational Psychology. Authored by : Borlin. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Psychology 2e. Authored by : Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett. Provided by : Open Stax. Retrieved from : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Extrinsic vs Intrinsic Motivation. Provided by : ASCatRIT. Retrieved from : https://youtu.be/kUNE4RtZnbk. License : All Rights Reserved

Educational Psychology Copyright © 2020 by Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

14.3 Process Theories of Motivation

- Describe the process theories of motivation, and compare and contrast the main process theories of motivation: operant conditioning theory, equity theory, goal theory, and expectancy theory.

Process theories of motivation try to explain why behaviors are initiated. These theories focus on the mechanism by which we choose a target, and the effort that we exert to “hit” the target. There are four major process theories: (1) operant conditioning, (2) equity, (3) goal, and (4) expectancy.

Operant Conditioning Theory

Operant conditioning theory is the simplest of the motivation theories. It basically states that people will do those things for which they are rewarded and will avoid doing things for which they are punished. This premise is sometimes called the “law of effect.” However, if this were the sum total of conditioning theory, we would not be discussing it here. Operant conditioning theory does offer greater insights than “reward what you want and punish what you don’t,” and knowledge of its principles can lead to effective management practices.

Operant conditioning focuses on the learning of voluntary behaviors. 18 The term operant conditioning indicates that learning results from our “operating on” the environment. After we “operate on the environment” (that is, behave in a certain fashion), consequences result. These consequences determine the likelihood of similar behavior in the future. Learning occurs because we do something to the environment. The environment then reacts to our action, and our subsequent behavior is influenced by this reaction.

The Basic Operant Model

According to operant conditioning theory , we learn to behave in a particular fashion because of consequences that resulted from our past behaviors. 19 The learning process involves three distinct steps (see Table 14.2 ). The first step involves a stimulus (S). The stimulus is any situation or event we perceive that we then respond to. A homework assignment is a stimulus. The second step involves a response (R), that is, any behavior or action we take in reaction to the stimulus. Staying up late to get your homework assignment in on time is a response. (We use the words response and behavior interchangeably here.) Finally, a consequence (C) is any event that follows our response and that makes the response more or less likely to occur in the future. If Colleen Sullivan receives praise from her superior for working hard, and if getting that praise is a pleasurable event, then it is likely that Colleen will work hard again in the future. If, on the other hand, the superior ignores or criticizes Colleen’s response (working hard), this consequence is likely to make Colleen avoid working hard in the future. It is the experienced consequence (positive or negative) that influences whether a response will be repeated the next time the stimulus is presented.

Reinforcement occurs when a consequence makes it more likely the response/behavior will be repeated in the future. In the previous example, praise from Colleen’s superior is a reinforcer. Extinction occurs when a consequence makes it less likely the response/behavior will be repeated in the future. Criticism from Colleen’s supervisor could cause her to stop working hard on any assignment.

There are three ways to make a response more likely to recur: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and avoidance learning. In addition, there are two ways to make the response less likely to recur: nonreinforcement and punishment.

Making a Response More Likely

According to reinforcement theorists, managers can encourage employees to repeat a behavior if they provide a desirable consequence, or reward, after the behavior is performed. A positive reinforcement is a desirable consequence that satisfies an active need or that removes a barrier to need satisfaction. It can be as simple as a kind word or as major as a promotion. Companies that provide “dinners for two” as awards to those employees who go the extra mile are utilizing positive reinforcement. It is important to note that there are wide variations in what people consider to be a positive reinforcer. Praise from a supervisor may be a powerful reinforcer for some workers (like high-nAch individuals) but not others.

Another technique for making a desired response more likely to be repeated is known as negative reinforcement . When a behavior causes something undesirable to be taken away, the behavior is more likely to be repeated in the future. Managers use negative reinforcement when they remove something unpleasant from an employee’s work environment in the hope that this will encourage the desired behavior. Ted doesn’t like being continually reminded by Philip to work faster (Ted thinks Philip is nagging him), so he works faster at stocking shelves to avoid being criticized. Philip’s reminders are a negative reinforcement for Ted.

Approach using negative reinforcement with extreme caution. Negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment. Punishment, unlike reinforcement (negative or positive), is intended to make a particular behavior go away (not be repeated). Negative reinforcement, like positive reinforcement, is intended to make a behavior more likely to be repeated in the future. In the previous example, Philip’s reminders simultaneously punished one behavior (slow stocking) and reinforced another (faster stocking). The difference is often a fine one, but it becomes clearer when we identify the behaviors we are trying to encourage (reinforcement) or discourage (punishment).

A third method of making a response more likely to occur involves a process known as avoidance learning. Avoidance learning occurs when we learn to behave in a certain way to avoid encountering an undesired or unpleasant consequence. We may learn to wake up a minute or so before our alarm clock rings so we can turn it off and not hear the irritating buzzer. Some workers learn to get to work on time to avoid the harsh words or punitive actions of their supervisors. Many organizational discipline systems rely heavily on avoidance learning by using the threat of negative consequences to encourage desired behavior. When managers warn an employee not to be late again, when they threaten to fire a careless worker, or when they transfer someone to an undesirable position, they are relying on the power of avoidance learning.

Making a Response Less Likely

At times it is necessary to discourage a worker from repeating an undesirable behavior. The techniques managers use to make a behavior less likely to occur involve doing something that frustrates the individual’s need satisfaction or that removes a currently satisfying circumstance. Punishment is an aversive consequence that follows a behavior and makes it less likely to reoccur.

Note that managers have another alternative, known as nonreinforcement , in which they provide no consequence at all following a worker’s response. Nonreinforcement eventually reduces the likelihood of that response reoccurring, which means that managers who fail to reinforce a worker’s desirable behavior are also likely to see that desirable behavior less often. If Philip never rewards Ted when he finishes stocking on time, for instance, Ted will probably stop trying to beat the clock. Nonreinforcement can also reduce the likelihood that employees will repeat undesirable behaviors, although it doesn’t produce results as quickly as punishment does. Furthermore, if other reinforcing consequences are present, nonreinforcement is unlikely to be effective.

While punishment clearly works more quickly than does nonreinforcement, it has some potentially undesirable side effects. Although punishment effectively tells a person what not to do and stops the undesired behavior, it does not tell them what they should do. In addition, even when punishment works as intended, the worker being punished often develops negative feelings toward the person who does the punishing. Although sometimes it is very difficult for managers to avoid using punishment, it works best when reinforcement is also used. An experiment conducted by two researchers at the University of Kansas found that using nonmonetary reinforcement in addition to punitive disciplinary measures was an effective way to decrease absenteeism in an industrial setting. 20

Schedules of Reinforcement

When a person is learning a new behavior, like how to perform a new job, it is desirable to reinforce effective behaviors every time they are demonstrated (this is called shaping ). But in organizations it is not usually possible to reinforce desired behaviors every time they are performed, for obvious reasons. Moreover, research indicates that constantly reinforcing desired behaviors, termed continuous reinforcement, can be detrimental in the long run. Behaviors that are learned under continuous reinforcement are quickly extinguished (cease to be demonstrated). This is because people will expect a reward (the reinforcement) every time they display the behavior. When they don’t receive it after just a few times, they quickly presume that the behavior will no longer be rewarded, and they quit doing it. Any employer can change employees’ behavior by simply not paying them!

If behaviors cannot (and should not) be reinforced every time they are exhibited, how often should they be reinforced? This is a question about schedules of reinforcement , or the frequency at which effective employee behaviors should be reinforced. Much of the early research on operant conditioning focused on the best way to maintain the performance of desired behaviors. That is, it attempted to determine how frequently behaviors need to be rewarded so that they are not extinguished. Research zeroed in on four types of reinforcement schedules:

Fixed Ratio. With this schedule, a fixed number of responses (let’s say five) must be exhibited before any of the responses are reinforced. If the desired response is coming to work on time, then giving employees a $25 bonus for being punctual every day from Monday through Friday would be a fixed ratio of reinforcement.

Variable Ratio. A variable-ratio schedule reinforces behaviors, on average, a fixed number of times (again let’s say five). Sometimes the tenth behavior is reinforced, other times the first, but on average every fifth response is reinforced. People who perform under such variable-ratio schedules like this don’t know when they will be rewarded, but they do know that they will be rewarded.

Fixed Interval. In a fixed-interval schedule, a certain amount of time must pass before a behavior is reinforced. With a one-hour fixed-interval schedule, for example, a supervisor visits an employee’s workstation and reinforces the first desired behavior she sees. She returns one hour later and reinforces the next desirable behavior. This schedule doesn’t imply that reinforcement will be received automatically after the passage of the time period. The time must pass and an appropriate response must be made.

Variable Interval. The variable interval differs from fixed-interval schedules in that the specified time interval passes on average before another appropriate response is reinforced. Sometimes the time period is shorter than the average; sometimes it is longer.

Which type of reinforcement schedule is best? In general, continuous reinforcement is best while employees are learning their jobs or new duties. After that, variable-ratio reinforcement schedules are superior. In most situations the fixed-interval schedule produces the least effective results, with fixed ratio and variable interval falling in between the two extremes. But remember that effective behaviors must be reinforced with some type of schedule, or they may become extinguished.

Equity Theory

Suppose you have worked for a company for several years. Your performance has been excellent, you have received regular pay increases, and you get along with your boss and coworkers. One day you come to work to find that a new person has been hired to work at the same job that you do. You are pleased to have the extra help. Then, you find out the new person is making $100 more per week than you, despite your longer service and greater experience. How do you feel? If you’re like most of us, you’re quite unhappy. Your satisfaction has just evaporated. Nothing about your job has changed—you receive the same pay, do the same job, and work for the same supervisor. Yet, the addition of one new employee has transformed you from a happy to an unhappy employee. This feeling of unfairness is the basis for equity theory.

Equity theory states that motivation is affected by the outcomes we receive for our inputs compared to the outcomes and inputs of other people. 21 This theory is concerned with the reactions people have to outcomes they receive as part of a “social exchange.” According to equity theory, our reactions to the outcomes we receive from others (an employer) depend both on how we value those outcomes in an absolute sense and on the circumstances surrounding their receipt. Equity theory suggests that our reactions will be influenced by our perceptions of the “inputs” provided in order to receive these outcomes (“Did I get as much out of this as I put into it?”). Even more important is our comparison of our inputs to what we believe others received for their inputs (“Did I get as much for my inputs as my coworkers got for theirs?”).

The Basic Equity Model

The fundamental premise of equity theory is that we continuously monitor the degree to which our work environment is “fair.” In determining the degree of fairness, we consider two sets of factors, inputs and outcomes (see Exhibit 14.11 ). Inputs are any factors we contribute to the organization that we feel have value and are relevant to the organization. Note that the value attached to an input is based on our perception of its relevance and value. Whether or not anyone else agrees that the input is relevant or valuable is unimportant to us. Common inputs in organizations include time, effort, performance level, education level, skill levels, and bypassed opportunities. Since any factor we consider relevant is included in our evaluation of equity, it is not uncommon for factors to be included that the organization (or even the law) might argue are inappropriate (such as age, sex, ethnic background, or social status).

Outcomes are anything we perceive as getting back from the organization in exchange for our inputs. Again, the value attached to an outcome is based on our perceptions and not necessarily on objective reality. Common outcomes from organizations include pay, working conditions, job status, feelings of achievement, and friendship opportunities. Both positive and negative outcomes influence our evaluation of equity. Stress, headaches, and fatigue are also potential outcomes. Since any outcome we consider relevant to the exchange influences our equity perception, we frequently include unintended factors (peer disapproval, family reactions).

Equity theory predicts that we will compare our outcomes to our inputs in the form of a ratio. On the basis of this ratio we make an initial determination of whether or not the situation is equitable. If we perceive that the outcomes we receive are commensurate with our inputs, we are satisfied. If we believe that the outcomes are not commensurate with our inputs, we are dissatisfied. This dissatisfaction can lead to ineffective behaviors for the organization if they continue. The key feature of equity theory is that it predicts that we will compare our ratios to the ratios of other people. It is this comparison of the two ratios that has the strongest effect on our equity perceptions. These other people are called referent others because we “refer to” them when we judge equity. Usually, referent others are people we work with who perform work of a similar nature. That is, referent others perform jobs that are similar in difficulty and complexity to the employee making the equity determination (see Exhibit 14.11 ).

Three conditions can result from this comparison. Our outcome-to-input ratio could equal the referent other’s. This is a state of equity . A second result could be that our ratio is greater than the referent other’s. This is a state of overreward inequity . The third result could be that we perceive our ratio to be less than that of the referent other. This is a state of underreward inequity .

Equity theory has a lot to say about basic human tendencies. The motivation to compare our situation to that of others is strong. For example, what is the first thing you do when you get an exam back in class? Probably look at your score and make an initial judgment as to its fairness. For a lot of people, the very next thing they do is look at the scores received by fellow students who sit close to them. A 75 percent score doesn’t look so bad if everyone else scored lower! This is equity theory in action.

Most workers in the United States are at least partially dissatisfied with their pay. 22 Equity theory helps explain this. Two human tendencies create feelings of inequity that are not based in reality. One is that we tend to overrate our performance levels. For example, one study conducted by your authors asked more than 600 employees to anonymously rate their performance on a 7-point scale (1 = poor, 7 = excellent). The average was 6.2, meaning the average employee rated his or her performance as very good to excellent. This implies that the average employee also expects excellent pay increases, a policy most employers cannot afford if they are to remain competitive. Another study found that the average employee (one whose performance is better than half of the other employees and worse than the other half) rated her performance at the 80th percentile (better than 80 percent of the other employees, worse than 20 percent). 23 Again it would be impossible for most organizations to reward the average employee at the 80th percentile. In other words, most employees inaccurately overrate the inputs they provide to an organization. This leads to perceptions of inequity that are not justified.

The second human tendency that leads to unwarranted perceptions of inequity is our tendency to overrate the outcomes of others. 24 Many employers keep the pay levels of employees a “secret.” Still other employers actually forbid employees to talk about their pay. This means that many employees don’t know for certain how much their colleagues are paid. And, because most of us overestimate the pay of others, we tend to think that they’re paid more than they actually are, and the unjustified perceptions of inequity are perpetuated.

The bottom line for employers is that they need to be sensitive to employees’ need for equity. Employers need to do everything they can to prevent feelings of inequity because employees engage in effective behaviors when they perceive equity and ineffective behaviors when they perceive inequity.

Perceived Overreward Inequity

When we perceive that overreward inequity exists (that is, we unfairly make more than others), it is rare that we are so dissatisfied, guilty, or sufficiently motivated that we make changes to produce a state of perceived equity (or we leave the situation). Indeed, feelings of overreward, when they occur, are quite transient. Very few of us go to our employers and complain that we’re overpaid! Most people are less sensitive to overreward inequities than they are to underreward inequities. 25 However infrequently they are used for overreward, the same types of actions are available for dealing with both types of inequity.

Perceived Underreward Inequity

When we perceive that underreward inequity exists (that is, others unfairly make more than we do), we will likely be dissatisfied, angered, and motivated to change the situation (or escape the situation) in order to produce a state of perceived equity. As we discuss shortly, people can take many actions to deal with underreward inequity.

Reducing Underreward Inequity

A simple situation helps explain the consequences of inequity. Two automobile workers in Detroit, John and Mary, fasten lug nuts to wheels on cars as they come down the assembly line, John on the left side and Mary on the right. Their inputs are equal (both fasten the same number of lug nuts at the same pace), but John makes $500 per week and Mary makes $600. Their equity ratios are thus:

As you can see, their ratios are not equal; that is, Mary receives greater outcome for equal input. Who is experiencing inequity? According to equity theory, both John and Mary—underreward inequity for John, and overreward inequity for Mary. Mary’s inequity won’t last long (in real organizations), but in our hypothetical example, what might John do to resolve this?

Adams identified a number of things people do to reduce the tension produced by a perceived state of inequity. They change their own outcomes or inputs, or they change those of the referent other. They distort their own perceptions of the outcomes or inputs of either party by using a different referent other, or they leave the situation in which the inequity is occurring.

- Alter inputs of the person. The perceived state of equity can be altered by changing our own inputs, that is, by decreasing the quantity or quality of our performance. John can affect his own mini slowdown and install only nine lug nuts on each car as it comes down the production line. This, of course, might cause him to lose his job, so he probably won’t choose this alternative.

- Alter outcomes of the person. We could attempt to increase outcomes to achieve a state of equity, like ask for a raise, a nicer office, a promotion, or other positively valued outcomes. So John will likely ask for a raise. Unfortunately, many people enhance their outcomes by stealing from their employers.

- Alter inputs of the referent other. When underrewarded, we may try to achieve a state of perceived equity by encouraging the referent other to increase their inputs. We may demand, for example, that the referent other “start pulling their weight,” or perhaps help the referent other to become a better performer. It doesn’t matter that the referent other is already pulling their weight—remember, this is all about perception. In our example, John could ask Mary to put on two of his ten lug nuts as each car comes down the assembly line. This would not likely happen, however, so John would be motivated to try another alternative to reduce his inequity.

- Alter outcomes of the referent other. We can “correct” a state of underreward by directly or indirectly reducing the value of the other’s outcomes. In our example, John could try to get Mary’s pay lowered to reduce his inequity. This too would probably not occur in the situation described.

- Distort perceptions of inputs or outcomes. It is possible to reduce a perceived state of inequity without changing input or outcome. We simply distort our own perceptions of our inputs or outcomes, or we distort our perception of those of the referent other. Thus, John may tell himself that “Mary does better work than I thought” or “she enjoys her work much less than I do” or “she gets paid less than I realized.”

- Choose a different referent other. We can also deal with both over- and underreward inequities by changing the referent other (“my situation is really more like Ahmed’s”). This is the simplest and most powerful way to deal with perceived inequity: it requires neither actual nor perceptual changes in anybody’s input or outcome, and it causes us to look around and assess our situation more carefully. For example, John might choose as a referent other Bill, who installs dashboards but makes less money than John.

- Leave the situation. A final technique for dealing with a perceived state of inequity involves removing ourselves from the situation. We can choose to accomplish this through absenteeism, transfer, or termination. This approach is usually not selected unless the perceived inequity is quite high or other attempts at achieving equity are not readily available. Most automobile workers are paid quite well for their work. John is unlikely to find an equivalent job, so it is also unlikely that he will choose this option.

Implications of Equity Theory

Equity theory is widely used, and its implications are clear. In the vast majority of cases, employees experience (or perceive) underreward inequity rather than overreward. As discussed above, few of the behaviors that result from underreward inequity are good for employers. Thus, employers try to prevent unnecessary perceptions of inequity. They do this in a number of ways. They try to be as fair as possible in allocating pay. That is, they measure performance levels as accurately as possible, then give the highest performers the highest pay increases. Second, most employers are no longer secretive about their pay schedules. People are naturally curious about how much they are paid relative to others in the organization. This doesn’t mean that employers don’t practice discretion—they usually don’t reveal specific employees’ exact pay. But they do tell employees the minimum and maximum pay levels for their jobs and the pay scales for the jobs of others in the organization. Such practices give employees a factual basis for judging equity.

Supervisors play a key role in creating perceptions of equity. “Playing favorites” ensures perceptions of inequity. Employees want to be rewarded on their merits, not the whims of their supervisors. In addition, supervisors need to recognize differences in employees in their reactions to inequity. Some employees are highly sensitive to inequity, and a supervisor needs to be especially cautious around them. 26 Everyone is sensitive to reward allocation. 27 But “equity sensitives” are even more sensitive. A major principle for supervisors, then, is simply to implement fairness. Never base punishment or reward on whether or not you like an employee. Reward behaviors that contribute to the organization, and discipline those that do not. Make sure employees understand what is expected of them, and praise them when they do it. These practices make everyone happier and your job easier.

Goal Theory

No theory is perfect. If it was, it wouldn’t be a theory. It would be a set of facts. Theories are sets of propositions that are right more often than they are wrong, but they are not infallible. However, the basic propositions of goal theory* come close to being infallible. Indeed, it is one of the strongest theories in organizational behavior.

The Basic Goal-Setting Model

Goal theory states that people will perform better if they have difficult, specific, accepted performance goals or objectives. 28 , 29 The first and most basic premise of goal theory is that people will attempt to achieve those goals that they intend to achieve. Thus, if we intend to do something (like get an A on an exam), we will exert effort to accomplish it. Without such goals, our effort at the task (studying) required to achieve the goal is less. Students whose goals are to get As study harder than students who don’t have this goal—we all know this. This doesn’t mean that people without goals are unmotivated. It simply means that people with goals are more motivated. The intensity of their motivation is greater, and they are more directed.

The second basic premise is that difficult goals result in better performance than easy goals. This does not mean that difficult goals are always achieved, but our performance will usually be better when we intend to achieve harder goals. Your goal of an A in Classical Mechanics at Cal Tech may not get you your A, but it may earn you a B+, which you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. Difficult goals cause us to exert more effort, and this almost always results in better performance.

Another premise of goal theory is that specific goals are better than vague goals. We often wonder what we need to do to be successful. Have you ever asked a professor “What do I need to do to get an A in this course?” If she responded “Do well on the exams,” you weren’t much better off for having asked. This is a vague response. Goal theory says that we perform better when we have specific goals. Had your professor told you the key thrust of the course, to turn in all the problem sets, to pay close attention to the essay questions on exams, and to aim for scores in the 90s, you would have something concrete on which to build a strategy.