An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Prim Care

A qualitative assessment of medical assistant professional aspirations and their alignment with career ladders across three institutions

Stacie vilendrer.

1 Division of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University School of Medicine, 1265 Welch Rd., Mail Code 5475, Stanford, CA 94305 USA

Alexis Amano

Cati brown johnson, timothy morrison.

2 Stanford Health Care, 300 Pasteur Drive, Palo Alto, CA 94304 USA

Associated Data

Original qualitative interview recordings and transcripts will not be shared given possible risk to individual privacy. For questions related to the data, please contact Dr. Stacie Vilendrer at [email protected].

Growing demand for medical assistants (MAs) in team-based primary care has led health systems to explore career ladders based on expanded MA responsibilities as a solution to improve MA recruitment and retention. However, the practical implementation of career ladders remains a challenge for many health systems. In this study, we aim to understand MA career aspirations and their alignment with available advancement opportunities.

Semi-structured focus groups were conducted August to December 2019 in primary care clinics based in three health systems in California and Utah. MA perspectives of career aspirations and their alignment with existing career ladders were discussed, recorded, and qualitatively analyzed.

Ten focus groups conducted with 59 participants revealed three major themes: mixed perceptions of expanded MA roles with concern over increased responsibility without commensurate increase in pay; divergent career aspirations among MAs not addressed by existing career ladders; and career ladder implementation challenges including opaque advancement requirements and lack of consistency across practice settings.

MAs held positive perceptions of career ladders in theory, yet recommended a number of improvements to their practical implementation across three institutions including improving clarity and consistency around requirements for advancement and matching compensation to job responsibilities. The emergence of two distinct clusters of MA professional needs and desires suggests an opportunity to further optimize career ladders to provide tailored support to MAs in order to strengthen the healthcare workforce and talent pipeline.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12875-022-01712-z.

Primary care practices have increasingly turned to team-based primary care models in their efforts to efficiently provide high quality care [ 1 , 2 ]. As work processes shift in these multi-disciplinary teams to allow each member to perform “at the top of their license” [ 3 , 4 ], medical assistants (MAs) have seen their responsibilities expand to include panel management, health coaching, scribing, translating, phlebotomy, and other multi-functional roles, which vary by site and state licensing [ 5 – 7 ]. Demand is skyrocketing for MAs; growth projections exceed the average for all occupations by over four-fold [ 8 ]. Factors contributing to demand include the relative value of MAs in health systems (2019 median salary $34,800 [ 8 ]), short training periods, scope of work flexibility, and contribution to positive patient outcomes [ 5 , 9 ].

Efforts to employ and retain such a valuable workforce are of considerable interest to healthcare organizations, given the shortage of available MAs, annual turnover rates of 20–30%, and replacement costs that reach 40% of MA yearly salary [ 10 , 11 ]. Research around these challenges is limited; lack of career advancement opportunity [ 10 , 12 ] and negative perceptions of organizational culture may contribute to MA turnover [ 13 ].

Given these challenges, many organizations are exploring novel solutions to recruit and retain the MA workforce [ 5 , 14 ] with the goal of ultimately improving patient outcomes and workforce efficiency [ 15 – 18 ]. One such solution is the implementation of career ladders— paths of professional advancement that provide employees with greater compensation as they cultivate and demonstrate additional skills and increase job responsibilities [ 15 ]. Formal MA career advancement opportunities have been associated with improved quality of care, teamwork, employee satisfaction and intent to stay with current employer [ 5 , 9 , 19 , 20 ]. An evaluation of 15 case studies in which new MA roles and opportunities for advancement were implemented alongside primary care model redesigns found associated improvements in patient and employee satisfaction, cost reduction, and quality [ 5 ]. Notably, MA advancement opportunities also have equity implications. Both women and racial minorities make up the majority of working MAs [ 21 ]. By improving wage earning and career advancement opportunities, healthcare organizations have the opportunity to address racial and gender equity in the healthcare workforce.

Despite these benefits, health organizations face challenges expanding the MA role and structuring meaningful advancement opportunities [ 7 , 22 ]. Lags in implementation of a career ladder following MA role expansion can lead to MA frustration, particularly as these workers may see their responsibilities, but not pay, increase [ 7 ]. Career ladders often require institutional-level support, given that adjustments to compensation often occur at a system-wide level [ 7 , 23 ]. Variation in MA training as well as in state certification and licensure requirements present further obstacles [ 7 , 16 ]. MA education and training programs range from 6-month certificate programs to two-year associates degree programs, and the curriculum offered often varies between programs. Although no states require MA licensure or professional certification, many require certification in specific practice settings or require job training [ 16 ]. MA certification is offered by a number of professional and certification organizations, but the associated education and training requirements vary [ 19 ].

As healthcare organizations continue to establish and refine career ladders, an understanding of MA career aspirations and how they align with current implementations of career ladders is needed. This assessment aims to fill this gap with a qualitative analysis of MA focus groups discussing career aspirations and career ladders implemented at three institutions.

MA perspectives of career aspirations and existing career ladders within their institutions were assessed through a series of semi-structured focus groups. Implementation outcomes were drawn from the Implementation Outcomes Framework, including acceptability, appropriateness, and perceived effectiveness at improving recruitment and retention [ 24 ].

Sites included primary care clinics in three health systems across urban, suburban and partially rural U.S. geographies (University Healthcare Alliance, Newark, CA; Stanford Health Care, Stanford, CA; Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, UT). Within each institution, a subset of sites were chosen to represent urban (including suburban) and partial rural settings where available [ 25 ].

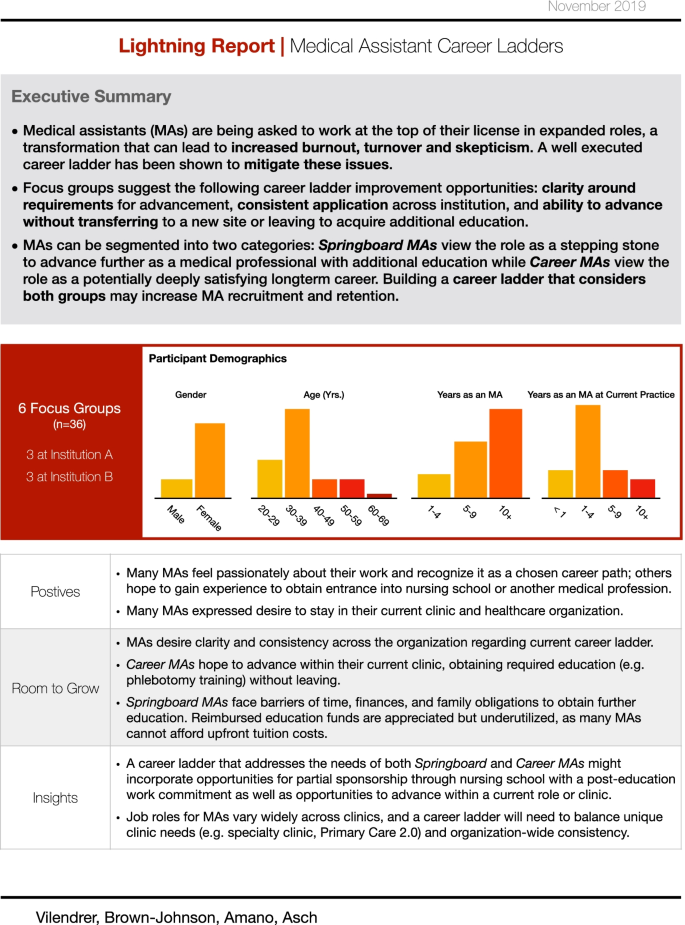

MA career ladders at the three institutions ranged between 3 and 4 levels, where combination of clinical responsibility and tenure within a site determined a promotion. Administrative contacts reported these were in place for 1 year or more across each institution, though the details varied by clinical site and were often not documented. Two of the organizations were also in the process of revising career ladder details at the time of analysis, thus it was not feasible to capture the details of each of these heterogenous career ladder structures in this analysis. This evaluation was reviewed by the Stanford School of Medicine and Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Boards and did not meet the definition of human subjects research; it therefore followed institutional protocols governing quality improvement efforts rather than research (Protocols #51945, #1051215, respectively). As such, early findings were reported back to operational leaders at each institution partway through the analysis to inform ongoing improvement (Fig. 1 ) [ 26 ]. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Lightning report on focus group findings

Data collection

From August to December 2019, all MAs within each selected clinic were emailed an invitation to participate in an hour-long focus group by managers who were not present during the conversation. The focus group methodology was chosen to optimize limited research resources, draw out the collective views of the MA population and engage otherwise hesitant participants, particularly given their relative vulnerability as the lowest paid members of the clinical team [ 27 , 28 ]. An unknown minority of MA participants who were invited did not attend the focus group due to clinical care activities. Participants did not receive financial compensation, though lunch was provided. No author practiced within these clinics. Focus groups (led by physician and health services researcher SV) were conducted at clinic sites and consisted of a qualitative semi-structured discussion around MA perceptions of career ladders and financial incentives, the latter of which is the focus of other work [ 14 ]. (See protocol in Additional file 1 : Appendix A.) Conversations were recorded with permission from all participants and transcribed (Rev, Austin, TX). Field notes were also taken by an author (AA) in three focus groups. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was achieved.

Data analysis

Analysis of data collected was rooted in grounded theory [ 29 – 31 ]. Authors (SV, CBJ, AA) created an initial codebook based on emergent themes from early transcripts and used a constant comparative method [ 30 – 32 ] to categorize remaining data using software (NVivo 12, Burlington, MA). Authors (SV, CBJ, AA) collectively reviewed a subset of three transcripts to reach consensus on a coding structure before recoding all remaining transcripts in sequence to ensure consistency. Codes were further analyzed by a single author (AA) to identify any potential differences in MA perceptions across clinic organizations and geographies. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were used to inform reporting of the study findings (Supplemental file 1 ) [ 33 ].

Across the three institutions, ten focus groups were conducted with 4 to 9 participants each for a total of 59 participants. Most MA participants (78.0%) worked in urban/suburban settings, 44% were 30–39 years of age, 92% identified as women, 37% were white, and 54% were non-Hispanic. Nearly half had worked as an MA for 10+ years (Additional file 1 : Appendix B). The demographic composition of study participants with female sex and non-White individuals predominating was consistent with national and local trends [ 16 , 34 , 35 ]. Findings were consistent across institutions as well as urban versus partial rural areas and are therefore described uniformly.

Our qualitative analysis surfaced three major themes: mixed perceptions of expanded MA roles with primary concern over increased responsibility without commensurate increase in pay; divergent career aspirations among MAs not addressed by existing career ladders; and career ladder implementation challenges including opaque advancement requirements and lack of consistency across practice settings. Underlying each of these themes were feelings of underappreciation for the MA role by healthcare organizations. Beyond these themes, a full accounting of factors reported to influence MAs’ decisions to join and remain within their organization can be found in Additional file 1 : Appendix C.

Mixed perceptions of MA career ladders and expanded roles

MAs overall welcomed the existence of a career ladder that would help them understand steps to gaining skills and increasing professional and economic growth. MAs also reported expanded responsibilities at all career levels when compared with their historical roles. However, this increased responsibility was often not associated with increased compensation, which led to subthemes of burnout, frustration over licensure limitations, and skepticism about the value placed on MA’s by the organization.

Several MAs elucidated the tension of being open to more responsibilities so long as they were associated with increased compensation. One MA shared, “I think it’s [career ladder] a positive thing. Also, if they’re going to pay you more, then it’s a really, really good positive thing” (MA 1, FG 2). Another was frustrated with recent changes to her workload: “Two [years ago the work increased]…My workload’s way different …a lot more computer stuff, reports, calling patients” (MA4, FG7). MAs expressed that this felt unfair: “It’s just discouraging if we’re doing all this work, and we’re not being recognized on our title and on our paycheck” (MA8, FG6). Some expressed a desire for a return to their prior responsibilities, or reported the variety of responsibilities and sheer workload created time pressures that reduced job satisfaction.

At the same time, MAs shared frustration at the limitations of what their licenses or job responsibilities allowed them to do. This sentiment clustered around the lack of upward growth opportunities available as well as limitations in day-to-day activities. One MA expressed dissatisfaction at the loss of her ability to place intravenous lines (IVs) due to changes in institutional protocols. Activities that were valued included patient-facing interaction, minor procedures (e.g. IV placement); less valued were computer work and scheduling. Overall, MAs’ desire for increased patient-facing and procedural responsibilities was uniform and appeared conditional on having enough time during the day to complete such tasks and the recognition of this added value in their paychecks.

Underlying these sentiments was skepticism of the organizational value of MAs. This was another factor that some MAs described as driving their desire to leave a given organization. Even while MAs were reportedly in short supply, they reported hearing the message from administration that they were dispensable:

“MA1: …a lot of people say that they don't feel like they're protected here. Like you could literally get fired for the smallest things.

MA3: …I was always afraid that I was getting fired because of things that were said…And just constantly getting talked to, or at, about certain things and never having that representative for myself in there. It was always my word against the manager's word…

MA2: You feel like management is against you and trying to get rid of you kind of thing. And then when you try to reach out to HR, they kind of give you that whole, ‘It's your manager. I'm going to have his or her's back, not your back, because you're replaceable and management's not replaceable.’” (MA1, MA2, MA3, FG4)

Some MAs described their human resource contact as being largely unhelpful, particularly related to questions of work performance, promotion, or career ladders.

Divergent MA career aspirations: “springboard” vs “career” MAs

MA career aspirations varied considerably and fell in two clusters: “springboard” MAs who pursued their current role as one step along a path to obtain a higher level license in healthcare, and “career” MAs who were not interested in obtaining a higher license in healthcare but rather were interested in growing within their careers as MAs (Table 1 ). Whether a given MA fell into one category or another depend in part on their backgrounds: “…personality-wise, we’re not all the same person. We have huge diversity groups in how you were raised or what your projection is or what you want out of life.” (MA 2, FG 7).

Medical assistant desired career trajectories and recommended path for advancement by cluster

“Springboard” MAs reported a desire to gain experience and save money in order to return to school primarily to become a nurse, though individuals also shared plans to become a physician or health administrator. Understanding their personal interest in healthcare before committing to additional training was felt to be a key reason for choosing the MA role: “Nursing... it’s expensive, and then it’s hard to get into. So, you don’t want to be that committed [before knowing you are ready]... I have friends that went into the medical field, and then after [they] were done or close to being done, they found out that they hate blood” (MA6, FG 6). The cost of making a mistake in investing in one’s career was thought to be high.

Alternately, “career” MAs did not nurture plans to return to school or switch professions. Instead, they expressed general contentment in their field and even described the benefits of being an MA over other healthcare careers:

“MA3:…I wouldn't even want to go to school as an RN... You just don't get that interaction with the patient…they [nurses] have time to go in, start the IV, run the machine, change bags, and then they're gone….I don't want to be that, I want to do patient interactions.

MA4: Our patients know our names.” (MA3, MA4, FG9)

“Maybe at age 60, I might want to retire…So, why stress myself out even further along…my mental health is something to consider too. So then, I said, ‘I'd rather leave it for somebody that's younger.’” (MA 3, FG 2)

Career ladders fall short of meeting “springboard” and “career” MA needs

Career ladders fell short when viewed through the lens of diverse MA career aspirations. The “springboard” MAs described above who hope to return to school face challenges obtaining financial resources to pursue this education, often while balancing family responsibilities: “[Returning to school requires] debt, time. Hard especially if you have family.” (MA8, FG6) While MAs in several settings described receiving funds for continuing education for their employer, these were a small portion of what was required for additional training. One MA described a loan-forgiveness program where the health system paid a fraction of her loans in exchange for an agreement to work at the institution following training. This program did not seem to entice the MA to shift her plans.

“Career” MAs who expressed a desire to stay within their given roles and clinics still hoped for increased professional growth opportunities. Many felt this was lacking: “I’m in that mode where I’m struggling…I want to be more but I have to do X, Y, and Z, and leave where I’m currently happy at in order to do that.” (MA1, FG1) Other MAs gave clues as to what might constitute these growth opportunities within their given roles. For example, an MA reported that her friend who worked as an MA at an outside health system was eventually hired into an administrative leaderhip role without having to go back for more schooling. The MAs in this focus group agreed that such a professional growth opportunity would be motivating, though no such opportunity existed within their institution. Another participant identified that taking on a new specialized responsibility such as patient coaching might increase her job satisfaction.

Career ladder implementation challenges across MAs

Other implementation challenges were noted across all MAs, regardless of their career aspirations. While MAs largely reacted positively to career ladders in theory, they desired increased clarity as to the requirements for advancement, consistency of these requirements across practice settings within a given institution, and local advancement opportunities.

MAs uniformly described a lack of clarity regarding career ladder details at all three health systems. The exchange below was typical across focus groups:

“Facilitator: So if you wanted to move up [the career ladder],… what would you have to do?

MA2: I have no idea.

MA4: We have no idea.” (FG3)

This challenge was attributed to a lack of communication from administration, both about the overall system and where individuals fit within that system: “We don’t know what level we’re in.” (MA1, FG 5). Other challenges included inconsistent recognition of responsibilities, inability to advance without re-applying for an open position or specializing, lack of individual career counseling, education funds that were challenging to use in practice, and desire for greater appreciation from local physicians and the health system overall. These sub-themes have been converted to direct and implied recommendations for career ladder improvement (Table 2 ).

Direct and implied MA recommendations for improving career ladders

Where career ladder knowledge existed, MAs faced other obstacles to advancement, such as the need for self-funded education: “You can become MA3, …but you have to have specific certification and you have to do CME [continuing medical education]. You have to pay for that yourself.” (MA 3, FG 7) In addition, many MAs who wanted to advance up the career ladder reported having to wait until a position of that particular level opened.

Further, MAs felt the career ladder did not acknowledge responsibility differences across clinic sites within the same institution, or differences in individual years of experience and training. Several MAs reported that job responsibilities for the same career level varied between clinics. For example, some entry-level MAs are asked to do front desk, back office, and phlebotomy work while others simply obtain vitals and room patients; MAs reported these differences were not reflected in the career ladder.

Again underscoring these concerns was a sense that MAs were not appreciated for their work. MAs highlighted the need to build this recognition into career ladder and compensation structure: “I think being more appreciated is a huge thing… knowing that I’m making a difference.” (MA5, FG9) These collective challenges made it difficult for MAs to advance within their existing role and clinic.

Well-designed career ladders have the potential to improve job satisfaction, thereby improving recruitment and retention of health workers with downstream benefits on patient care and operational efficiency. We found positive MA perceptions of career ladders in principle, though elements of their practical implementation were reported to need improvement across three institutions. Two disinct groups of MAs emerged with regard to their professional ambitions: “springboard” MAs hoped to advance to higher paying non-MA roles while “career” MAs desired professional and financial growth opportunities within the MA profession. Reported and implied recommendations for career ladder improvement included the need for health systems to provide MAs with clear and transparent requirements to ascend career ladders; consistent recognition of training, experience, and work responsibilities across the organization as demonstrated through career ladders; the ability to advance in place or with increased specialization; career counseling; and streamlined opportunities to use educational funds. The need for transparency and consistency in career ladder implementation is consistent with prior work [ 7 ], though this evaluation further contributes to discussions around structuring opportunities for advancement including continuing education and recognition that MAs may cluster into distinct segments based on their needs and career aspirations.

MAs varied in terms of their professional ambitions, including the degree to which they hoped to grow within their existing role and whether they planned to pursue additional training to move into another profession. Designing career experiences around employee career aspirations, including “grouping employees into clusters based on their wants and needs” has been briefly explored in business literature [ 36 ], yet such programs have yet to be formally explored in healthcare. Diverse MA needs discovered here suggest opportunities to optimize career ladders from the perspective of two distinct groups: “springboard” MAs and “career” MAs.

For “springboard MAs”, these results suggest health systems may benefit from anticipating—and moreover supporting—transitions from MA to other health professions, particularly for individuals who hope to remain within a given medical system. MAs frequently reported considering nursing as the next step in their career, a profession with well-documented worker shortages and high turnover cost [ 37 – 40 ]. Supporting these “springboard” MAs in their desire to become fully-trained nurses or other types of healthcare professionals may be a savvy way for health systems to create talent pipelines. We heard a single example in which one health system paid a small amount of tuition for additional education in exchange for an agreement to work after training for a minimum number of years. Such agreements exist in other industries and are increasingly used with physician trainees [ 41 ]; extending an adapted program to other health professions, including MAs, deserves further exploration.

MAs’ varied levels of ambition suggest that at least some turnover should be anticipated. Further study is needed to quantify the impact MA career intentions have on turnover, including the portion of MAs who may be retained or positively directed towards other roles within a given health system. We also note that supporting such MA advancement opportunities—whether within the MA role or in non-MA roles within the same institution—may benefit institutional goals towards diversifying workforce and leadership, as MAs typically come from diverse backgrounds that often closely align with the patient population they serve [ 5 , 34 ].

For the “career” MAs, we heard that opportunities that allow for advancement within their current MA profession may increase job satisfaction and thereby retention with its downstream financial and organizational benefits [ 10 , 11 ]. Literature outside healthcare also suggests that organizations can benefit when promoting from within, given that employees retain institution-specific knowledge that increases productivity [ 42 , 43 ]. We note major barriers to facilitating MA advancement within their current roles include licensing restrictions and common staffing structures in primary care—MA role expansion may mean MAs have taken over the historical positions they might have once stepped up into. Some primary care settings, including those in this analysis, are actively exploring further specializing MA roles based on additional training in mental health, population health management, or value-based care [ 5 , 44 ]. These opportunities may facilitate higher level advancement-in-place opportunities for MAs without requiring years of additional training.

We recognize another tension in that local clinic needs can vary significantly, and each may require different competencies from their MAs (e.g. phlebotomy, population health measures). This goes against MAs’ voiced desire that a career ladder consistently reflect competencies across an organization. Based on our overall findings, is seems that allowing for some local clinic-level flexibility to facilitate advancement-in-place opportunities may outweigh MA desire for career ladder consistency across the organization. Administrators must recognize and balance this tension in their efforts to optimize career ladder design.

Underlying these conversations was the dominant theme of MA role expansion in the last several years. While prior work has largely emphasized the benefits of this transition [ 5 , 15 , 16 ], we were struck by the unfavorable perspectives many MAs held when role expansion was discussed in the context of their career progression and, indirectly, compensation. In particular, MAs seemed to recognize they were providing more value to the health system than before, generally without increased compensation; this manifested in the perception that their organizations did not value them. It appears that career ladders, if implemented effectively, may begin to combat negative MA perceptions of fairness in their workplace, thereby improving “organizational justice” and retention [ 45 , 46 ]. Fortunately, despite these sentiments, early literature based on a subset of the population represented here suggests MAs do not experience significantly elevated rates of burnout [ 13 ], though additional study is needed.

Focus groups within three institutions across two geographies cannot encompass the full range of MA perspectives across the U.S., particularly as licensing laws vary from state to state. This evaluation reflects learnings to inform institutional practices, and extrapolation to outside settings is therefore limited. Future efforts to understand and optimize career ladders may benefit from expanded participation from administrators and MAs from diverse settings. Furthermore, we acknowledge two institutions at the time of interviews were working on career ladder improvements; this period of ongoing change may have reduced overall MA knowledge and satisfaction with the pre-existing programs. Additionally, we are unable to provide specific examples of the career ladders at each institution due to variation between clinic sites and ongoing revisions to their structures; understanding these trends is an area for future research. Our use of focus groups may also have limited certain individual disclosures, though we felt the benefits from a synergistic discussion with multiple voices outweighed that risk. Finally, the focus group structure also prohibited us from making comparisons on MA perceptions between racial/ethnic groups, which may be an important area of future study.

Conclusions

MA roles have undergone significant expansion in recent years, and identifying the right balance between organizational and employee needs is ongoing. Career ladders are perceived favorably by MAs in principle but their practical implementation merits further attention. Segmenting MAs into distinct clusters based on their career aspirations may serve as a useful model to further tailor career ladders to employee needs, though additional evaluation is still needed. Such efforts have the potential to strengthen the healthcare workforce and talent pipeline, with downstream benefits to patient care and operational efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Raj Srivastava of Intermountain Healthcare, Catherine Krna of the University Healthcare Alliance and Dr. Bryan Bohman of Stanford School of Medicine for their support in facilitating this evaluation.

Abbreviations

Authors’ contributions.

Author SV conceived of the concept; SV, SA and CB-J designed the evaluation and focus group protocol. Author SV collected focus group data with support from author TM. Authors SV, AA, CB-J analyzed the qualitative transcripts while author SV led the drafting of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript content and edits. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work received indirect support through the Stanford-Intermountain Fellowship in Population Health, Primary Care and Delivery Science.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

The study was reviewed by the Stanford School of Medicine and Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Boards and, as quality improvement, did not meet the definition of human subjects research (Protocols #51945, #1051215, respectively). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Not applicable.

No competing interests are reported.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Stacie Vilendrer, Email: ude.drofnats@veicats .

Alexis Amano, Email: ude.drofnats@onamama .

Cati Brown Johnson, Email: ude.drofnats@jbitac .

Timothy Morrison, Email: gro.erachtlaehdrofnats@nosirromit .

Steve Asch, Email: ude.drofnats@hcsas .

Medical assistants: the invisible "glue" of primary health care practices in the United States?

Affiliation.

- 1 University of California San Francisco Department of Family and Community Medicine, San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, California, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 20698404

- DOI: 10.1108/14777261011054626

Purpose: Little attention has been given to the field of medical assisting in US health services to date. To explore the roles medical assistants (MAs) currently play in primary care settings, the paper aims to focus on the work scope and dynamics of these increasingly common healthcare personnel.

Design/methodology/approach: This is a multiple step, mixed methods study, combining a quantitative survey and qualitative semi-structured interviews: eight experts in the field of medical assisting; 12 MAs from diverse primary care practice settings in Northern California.

Findings: Survey results revealed great variation in the breadth of tasks that MAs performed. Five overarching themes describe the experience of medical assistants in primary care settings: ensuring patient flow and acting as a patient liaison, "making a difference"; diversity within the occupation and work relationships.

Research implications/limitations: As the number of medical assistants working in primary care practices in the United States increases, more attention must be paid to how best to deploy this allied health workforce. This study suggests that MAs have an expertise in maintaining efficient clinic flow and promoting patient satisfaction. Future recommendations for changes in MA roles must address the diversity within this occupation in terms of workscope and quality assurance as well as MA relationships with other members of ambulatory care teams.

Originality/value: This is the first study to explore perspectives of medical assistants in the USA. As this is a largely unregulated and understudied field, a qualitative study allowed the exploration of major themes in medical assisting and the establishment of a framework from which further study can occur.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Allied Health Personnel / statistics & numerical data*

- Interviews as Topic

- Job Satisfaction*

- Middle Aged

- Primary Health Care* / organization & administration

- Professional Practice

- Professional Role*

- United States

- Young Adult

- Library Hours Servicios en Español Databases Research Guides Get Help My Account CCC Home myClackamas

- myClackamas

- Research Guides

- Servicios en Español

- CCC Library

- Health Professions

Medical Assistant

- APA (7th ed.) resources

- Course Reserves (textbooks)

- Article databases and eJournals

- eBook databases

- Streaming video databases

- CCC Library Catalog

- Search tips and strategies

APA 7th edition manual

Apa 7 citation examples, missing elements - apa 7, apa 7 paper formatting basics, apa 7 document templates, more apa 7th ed. resources.

- Job and career resources

This guide will introduce you to APA 7 citations, both for the References page of your paper and in-text citations. It is offered in multiple file formats below.

- Citation Examples - APA 7 - Word Document

- Citation Examples - APA 7 - PDF

This guide will tell you exactly what to do if your resource is missing a citation element. Can't find the author, publication date, page numbers, or something else? Use this guide to find out what to do! This guide is offered in multiple formats below.

- Missing Elements - APA 7 - Word Document

- Missing Elements - APA 7 - PDF

- Typed, double-spaced paragraphs.

- 1" margins on all sides.

- Align text to the left.

- Choose one of these fonts: 11-point Calibri, 11-points Arial, 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode, 12-point Times New Roman, 11-point Georgia, 10-point Computer Modern.

- Include a page header (also known as the "running head") at the top of every page with the page number.

- APA papers are broken up into sections. Check with your instructor for their expectations.

- In general, headings and title are centered.

APA 7th edition recognizes two kinds of paper formats - student papers (undergraduate students) and professional research papers (graduate students and professionals). At Clackamas CC, you will use the student paper formatting conventions.

You don't have to format a paper from scratch! Download this APA-formatted document template as a Word document or Google document. Save it, erase the existing text, and type your text right into the template. Learn how to format a paper in APA format by reading the contents of the template. The References page has been formatted with hanging indents.

- Download & edit: APA Word document template Microsoft Word document template to save a copy of and type into. To edit it, save a copy to your desktop or Clackamas Office 365 account. Includes tips on how to format a paper in APA. Last updated Feb. 2020.

- Download & edit: Pages document template If you need this template in Pages, email [email protected]

- View Only: Sample APA student paper (7th ed.) This sample student paper includes descriptions of indentations, margins, headers, and other formatting conventions (APA, 2020).

- APA Style (APA.org) APA's site answers all the basic questions about APA 7th edition and gives sample "student" and "professional" papers. This will help you with document format, in-text citations, the References list, and various stylistics.

- << Previous: Search tips and strategies

- Next: Job and career resources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 10:24 AM

- URL: https://libguides.clackamas.edu/medical-assistant

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Medical Assistant

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- ECG analysis Follow Following

- Addiction Medicine Follow Following

- Management Information System Follow Following

- Knowledge Translation Follow Following

- Alternative Medicine Follow Following

- Rating Scales Follow Following

- Journalism Follow Following

- New Media Follow Following

- Media Studies Follow Following

- Beletristica Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2022

A qualitative assessment of medical assistant professional aspirations and their alignment with career ladders across three institutions

- Stacie Vilendrer 1 ,

- Alexis Amano 1 ,

- Cati Brown Johnson 1 ,

- Timothy Morrison 2 &

- Steve Asch 1

BMC Primary Care volume 23 , Article number: 117 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2498 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Growing demand for medical assistants (MAs) in team-based primary care has led health systems to explore career ladders based on expanded MA responsibilities as a solution to improve MA recruitment and retention. However, the practical implementation of career ladders remains a challenge for many health systems. In this study, we aim to understand MA career aspirations and their alignment with available advancement opportunities.

Semi-structured focus groups were conducted August to December 2019 in primary care clinics based in three health systems in California and Utah. MA perspectives of career aspirations and their alignment with existing career ladders were discussed, recorded, and qualitatively analyzed.

Ten focus groups conducted with 59 participants revealed three major themes: mixed perceptions of expanded MA roles with concern over increased responsibility without commensurate increase in pay; divergent career aspirations among MAs not addressed by existing career ladders; and career ladder implementation challenges including opaque advancement requirements and lack of consistency across practice settings.

MAs held positive perceptions of career ladders in theory, yet recommended a number of improvements to their practical implementation across three institutions including improving clarity and consistency around requirements for advancement and matching compensation to job responsibilities. The emergence of two distinct clusters of MA professional needs and desires suggests an opportunity to further optimize career ladders to provide tailored support to MAs in order to strengthen the healthcare workforce and talent pipeline.

Peer Review reports

Primary care practices have increasingly turned to team-based primary care models in their efforts to efficiently provide high quality care [ 1 , 2 ]. As work processes shift in these multi-disciplinary teams to allow each member to perform “at the top of their license” [ 3 , 4 ], medical assistants (MAs) have seen their responsibilities expand to include panel management, health coaching, scribing, translating, phlebotomy, and other multi-functional roles, which vary by site and state licensing [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Demand is skyrocketing for MAs; growth projections exceed the average for all occupations by over four-fold [ 8 ]. Factors contributing to demand include the relative value of MAs in health systems (2019 median salary $34,800 [ 8 ]), short training periods, scope of work flexibility, and contribution to positive patient outcomes [ 5 , 9 ].

Efforts to employ and retain such a valuable workforce are of considerable interest to healthcare organizations, given the shortage of available MAs, annual turnover rates of 20–30%, and replacement costs that reach 40% of MA yearly salary [ 10 , 11 ]. Research around these challenges is limited; lack of career advancement opportunity [ 10 , 12 ] and negative perceptions of organizational culture may contribute to MA turnover [ 13 ].

Given these challenges, many organizations are exploring novel solutions to recruit and retain the MA workforce [ 5 , 14 ] with the goal of ultimately improving patient outcomes and workforce efficiency [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. One such solution is the implementation of career ladders— paths of professional advancement that provide employees with greater compensation as they cultivate and demonstrate additional skills and increase job responsibilities [ 15 ]. Formal MA career advancement opportunities have been associated with improved quality of care, teamwork, employee satisfaction and intent to stay with current employer [ 5 , 9 , 19 , 20 ]. An evaluation of 15 case studies in which new MA roles and opportunities for advancement were implemented alongside primary care model redesigns found associated improvements in patient and employee satisfaction, cost reduction, and quality [ 5 ]. Notably, MA advancement opportunities also have equity implications. Both women and racial minorities make up the majority of working MAs [ 21 ]. By improving wage earning and career advancement opportunities, healthcare organizations have the opportunity to address racial and gender equity in the healthcare workforce.

Despite these benefits, health organizations face challenges expanding the MA role and structuring meaningful advancement opportunities [ 7 , 22 ]. Lags in implementation of a career ladder following MA role expansion can lead to MA frustration, particularly as these workers may see their responsibilities, but not pay, increase [ 7 ]. Career ladders often require institutional-level support, given that adjustments to compensation often occur at a system-wide level [ 7 , 23 ]. Variation in MA training as well as in state certification and licensure requirements present further obstacles [ 7 , 16 ]. MA education and training programs range from 6-month certificate programs to two-year associates degree programs, and the curriculum offered often varies between programs. Although no states require MA licensure or professional certification, many require certification in specific practice settings or require job training [ 16 ]. MA certification is offered by a number of professional and certification organizations, but the associated education and training requirements vary [ 19 ].

As healthcare organizations continue to establish and refine career ladders, an understanding of MA career aspirations and how they align with current implementations of career ladders is needed. This assessment aims to fill this gap with a qualitative analysis of MA focus groups discussing career aspirations and career ladders implemented at three institutions.

MA perspectives of career aspirations and existing career ladders within their institutions were assessed through a series of semi-structured focus groups. Implementation outcomes were drawn from the Implementation Outcomes Framework, including acceptability, appropriateness, and perceived effectiveness at improving recruitment and retention [ 24 ].

Sites included primary care clinics in three health systems across urban, suburban and partially rural U.S. geographies (University Healthcare Alliance, Newark, CA; Stanford Health Care, Stanford, CA; Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, UT). Within each institution, a subset of sites were chosen to represent urban (including suburban) and partial rural settings where available [ 25 ].

MA career ladders at the three institutions ranged between 3 and 4 levels, where combination of clinical responsibility and tenure within a site determined a promotion. Administrative contacts reported these were in place for 1 year or more across each institution, though the details varied by clinical site and were often not documented. Two of the organizations were also in the process of revising career ladder details at the time of analysis, thus it was not feasible to capture the details of each of these heterogenous career ladder structures in this analysis. This evaluation was reviewed by the Stanford School of Medicine and Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Boards and did not meet the definition of human subjects research; it therefore followed institutional protocols governing quality improvement efforts rather than research (Protocols #51945, #1051215, respectively). As such, early findings were reported back to operational leaders at each institution partway through the analysis to inform ongoing improvement (Fig. 1 ) [ 26 ]. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Lightning report on focus group findings

Data collection

From August to December 2019, all MAs within each selected clinic were emailed an invitation to participate in an hour-long focus group by managers who were not present during the conversation. The focus group methodology was chosen to optimize limited research resources, draw out the collective views of the MA population and engage otherwise hesitant participants, particularly given their relative vulnerability as the lowest paid members of the clinical team [ 27 , 28 ]. An unknown minority of MA participants who were invited did not attend the focus group due to clinical care activities. Participants did not receive financial compensation, though lunch was provided. No author practiced within these clinics. Focus groups (led by physician and health services researcher SV) were conducted at clinic sites and consisted of a qualitative semi-structured discussion around MA perceptions of career ladders and financial incentives, the latter of which is the focus of other work [ 14 ]. (See protocol in Additional file 1 : Appendix A.) Conversations were recorded with permission from all participants and transcribed (Rev, Austin, TX). Field notes were also taken by an author (AA) in three focus groups. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was achieved.

Data analysis

Analysis of data collected was rooted in grounded theory [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Authors (SV, CBJ, AA) created an initial codebook based on emergent themes from early transcripts and used a constant comparative method [ 30 , 31 , 32 ] to categorize remaining data using software (NVivo 12, Burlington, MA). Authors (SV, CBJ, AA) collectively reviewed a subset of three transcripts to reach consensus on a coding structure before recoding all remaining transcripts in sequence to ensure consistency. Codes were further analyzed by a single author (AA) to identify any potential differences in MA perceptions across clinic organizations and geographies. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were used to inform reporting of the study findings (Supplemental file 1 ) [ 33 ].

Across the three institutions, ten focus groups were conducted with 4 to 9 participants each for a total of 59 participants. Most MA participants (78.0%) worked in urban/suburban settings, 44% were 30–39 years of age, 92% identified as women, 37% were white, and 54% were non-Hispanic. Nearly half had worked as an MA for 10+ years (Additional file 1 : Appendix B). The demographic composition of study participants with female sex and non-White individuals predominating was consistent with national and local trends [ 16 , 34 , 35 ]. Findings were consistent across institutions as well as urban versus partial rural areas and are therefore described uniformly.

Our qualitative analysis surfaced three major themes: mixed perceptions of expanded MA roles with primary concern over increased responsibility without commensurate increase in pay; divergent career aspirations among MAs not addressed by existing career ladders; and career ladder implementation challenges including opaque advancement requirements and lack of consistency across practice settings. Underlying each of these themes were feelings of underappreciation for the MA role by healthcare organizations. Beyond these themes, a full accounting of factors reported to influence MAs’ decisions to join and remain within their organization can be found in Additional file 1 : Appendix C.

Mixed perceptions of MA career ladders and expanded roles

MAs overall welcomed the existence of a career ladder that would help them understand steps to gaining skills and increasing professional and economic growth. MAs also reported expanded responsibilities at all career levels when compared with their historical roles. However, this increased responsibility was often not associated with increased compensation, which led to subthemes of burnout, frustration over licensure limitations, and skepticism about the value placed on MA’s by the organization.

Several MAs elucidated the tension of being open to more responsibilities so long as they were associated with increased compensation. One MA shared, “I think it’s [career ladder] a positive thing. Also, if they’re going to pay you more, then it’s a really, really good positive thing” (MA 1, FG 2). Another was frustrated with recent changes to her workload: “Two [years ago the work increased]…My workload’s way different …a lot more computer stuff, reports, calling patients” (MA4, FG7). MAs expressed that this felt unfair: “It’s just discouraging if we’re doing all this work, and we’re not being recognized on our title and on our paycheck” (MA8, FG6). Some expressed a desire for a return to their prior responsibilities, or reported the variety of responsibilities and sheer workload created time pressures that reduced job satisfaction.

At the same time, MAs shared frustration at the limitations of what their licenses or job responsibilities allowed them to do. This sentiment clustered around the lack of upward growth opportunities available as well as limitations in day-to-day activities. One MA expressed dissatisfaction at the loss of her ability to place intravenous lines (IVs) due to changes in institutional protocols. Activities that were valued included patient-facing interaction, minor procedures (e.g. IV placement); less valued were computer work and scheduling. Overall, MAs’ desire for increased patient-facing and procedural responsibilities was uniform and appeared conditional on having enough time during the day to complete such tasks and the recognition of this added value in their paychecks.

Underlying these sentiments was skepticism of the organizational value of MAs. This was another factor that some MAs described as driving their desire to leave a given organization. Even while MAs were reportedly in short supply, they reported hearing the message from administration that they were dispensable:

“MA1: …a lot of people say that they don't feel like they're protected here. Like you could literally get fired for the smallest things.

MA3: …I was always afraid that I was getting fired because of things that were said…And just constantly getting talked to, or at, about certain things and never having that representative for myself in there. It was always my word against the manager's word…

MA2: You feel like management is against you and trying to get rid of you kind of thing. And then when you try to reach out to HR, they kind of give you that whole, ‘It's your manager. I'm going to have his or her's back, not your back, because you're replaceable and management's not replaceable.’” (MA1, MA2, MA3, FG4)

Some MAs described their human resource contact as being largely unhelpful, particularly related to questions of work performance, promotion, or career ladders.

Divergent MA career aspirations: “springboard” vs “career” MAs

MA career aspirations varied considerably and fell in two clusters: “springboard” MAs who pursued their current role as one step along a path to obtain a higher level license in healthcare, and “career” MAs who were not interested in obtaining a higher license in healthcare but rather were interested in growing within their careers as MAs (Table 1 ). Whether a given MA fell into one category or another depend in part on their backgrounds: “…personality-wise, we’re not all the same person. We have huge diversity groups in how you were raised or what your projection is or what you want out of life.” (MA 2, FG 7).

“Springboard” MAs reported a desire to gain experience and save money in order to return to school primarily to become a nurse, though individuals also shared plans to become a physician or health administrator. Understanding their personal interest in healthcare before committing to additional training was felt to be a key reason for choosing the MA role: “Nursing... it’s expensive, and then it’s hard to get into. So, you don’t want to be that committed [before knowing you are ready]... I have friends that went into the medical field, and then after [they] were done or close to being done, they found out that they hate blood” (MA6, FG 6). The cost of making a mistake in investing in one’s career was thought to be high.

Alternately, “career” MAs did not nurture plans to return to school or switch professions. Instead, they expressed general contentment in their field and even described the benefits of being an MA over other healthcare careers:

“MA3:…I wouldn't even want to go to school as an RN... You just don't get that interaction with the patient…they [nurses] have time to go in, start the IV, run the machine, change bags, and then they're gone….I don't want to be that, I want to do patient interactions.

MA4: Our patients know our names.” (MA3, MA4, FG9)

A majority hoped to grow within their existing career and shared a desire to move into administration, teaching, or other leadership opportunities. Rare individuals expressed no desire to move up the career ladder. One attributed this to being late in her career:

“Maybe at age 60, I might want to retire…So, why stress myself out even further along…my mental health is something to consider too. So then, I said, ‘I'd rather leave it for somebody that's younger.’” (MA 3, FG 2)

Career ladders fall short of meeting “springboard” and “career” MA needs

Career ladders fell short when viewed through the lens of diverse MA career aspirations. The “springboard” MAs described above who hope to return to school face challenges obtaining financial resources to pursue this education, often while balancing family responsibilities: “[Returning to school requires] debt, time. Hard especially if you have family.” (MA8, FG6) While MAs in several settings described receiving funds for continuing education for their employer, these were a small portion of what was required for additional training. One MA described a loan-forgiveness program where the health system paid a fraction of her loans in exchange for an agreement to work at the institution following training. This program did not seem to entice the MA to shift her plans.

“Career” MAs who expressed a desire to stay within their given roles and clinics still hoped for increased professional growth opportunities. Many felt this was lacking: “I’m in that mode where I’m struggling…I want to be more but I have to do X, Y, and Z, and leave where I’m currently happy at in order to do that.” (MA1, FG1) Other MAs gave clues as to what might constitute these growth opportunities within their given roles. For example, an MA reported that her friend who worked as an MA at an outside health system was eventually hired into an administrative leaderhip role without having to go back for more schooling. The MAs in this focus group agreed that such a professional growth opportunity would be motivating, though no such opportunity existed within their institution. Another participant identified that taking on a new specialized responsibility such as patient coaching might increase her job satisfaction.

Career ladder implementation challenges across MAs

Other implementation challenges were noted across all MAs, regardless of their career aspirations. While MAs largely reacted positively to career ladders in theory, they desired increased clarity as to the requirements for advancement, consistency of these requirements across practice settings within a given institution, and local advancement opportunities.

MAs uniformly described a lack of clarity regarding career ladder details at all three health systems. The exchange below was typical across focus groups:

“Facilitator: So if you wanted to move up [the career ladder],… what would you have to do?

MA2: I have no idea.

MA4: We have no idea.” (FG3)

This challenge was attributed to a lack of communication from administration, both about the overall system and where individuals fit within that system: “We don’t know what level we’re in.” (MA1, FG 5). Other challenges included inconsistent recognition of responsibilities, inability to advance without re-applying for an open position or specializing, lack of individual career counseling, education funds that were challenging to use in practice, and desire for greater appreciation from local physicians and the health system overall. These sub-themes have been converted to direct and implied recommendations for career ladder improvement (Table 2 ).

Where career ladder knowledge existed, MAs faced other obstacles to advancement, such as the need for self-funded education: “You can become MA3, …but you have to have specific certification and you have to do CME [continuing medical education]. You have to pay for that yourself.” (MA 3, FG 7) In addition, many MAs who wanted to advance up the career ladder reported having to wait until a position of that particular level opened.

Further, MAs felt the career ladder did not acknowledge responsibility differences across clinic sites within the same institution, or differences in individual years of experience and training. Several MAs reported that job responsibilities for the same career level varied between clinics. For example, some entry-level MAs are asked to do front desk, back office, and phlebotomy work while others simply obtain vitals and room patients; MAs reported these differences were not reflected in the career ladder.

Again underscoring these concerns was a sense that MAs were not appreciated for their work. MAs highlighted the need to build this recognition into career ladder and compensation structure: “I think being more appreciated is a huge thing… knowing that I’m making a difference.” (MA5, FG9) These collective challenges made it difficult for MAs to advance within their existing role and clinic.

Well-designed career ladders have the potential to improve job satisfaction, thereby improving recruitment and retention of health workers with downstream benefits on patient care and operational efficiency. We found positive MA perceptions of career ladders in principle, though elements of their practical implementation were reported to need improvement across three institutions. Two disinct groups of MAs emerged with regard to their professional ambitions: “springboard” MAs hoped to advance to higher paying non-MA roles while “career” MAs desired professional and financial growth opportunities within the MA profession. Reported and implied recommendations for career ladder improvement included the need for health systems to provide MAs with clear and transparent requirements to ascend career ladders; consistent recognition of training, experience, and work responsibilities across the organization as demonstrated through career ladders; the ability to advance in place or with increased specialization; career counseling; and streamlined opportunities to use educational funds. The need for transparency and consistency in career ladder implementation is consistent with prior work [ 7 ], though this evaluation further contributes to discussions around structuring opportunities for advancement including continuing education and recognition that MAs may cluster into distinct segments based on their needs and career aspirations.

MAs varied in terms of their professional ambitions, including the degree to which they hoped to grow within their existing role and whether they planned to pursue additional training to move into another profession. Designing career experiences around employee career aspirations, including “grouping employees into clusters based on their wants and needs” has been briefly explored in business literature [ 36 ], yet such programs have yet to be formally explored in healthcare. Diverse MA needs discovered here suggest opportunities to optimize career ladders from the perspective of two distinct groups: “springboard” MAs and “career” MAs.

For “springboard MAs”, these results suggest health systems may benefit from anticipating—and moreover supporting—transitions from MA to other health professions, particularly for individuals who hope to remain within a given medical system. MAs frequently reported considering nursing as the next step in their career, a profession with well-documented worker shortages and high turnover cost [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Supporting these “springboard” MAs in their desire to become fully-trained nurses or other types of healthcare professionals may be a savvy way for health systems to create talent pipelines. We heard a single example in which one health system paid a small amount of tuition for additional education in exchange for an agreement to work after training for a minimum number of years. Such agreements exist in other industries and are increasingly used with physician trainees [ 41 ]; extending an adapted program to other health professions, including MAs, deserves further exploration.

MAs’ varied levels of ambition suggest that at least some turnover should be anticipated. Further study is needed to quantify the impact MA career intentions have on turnover, including the portion of MAs who may be retained or positively directed towards other roles within a given health system. We also note that supporting such MA advancement opportunities—whether within the MA role or in non-MA roles within the same institution—may benefit institutional goals towards diversifying workforce and leadership, as MAs typically come from diverse backgrounds that often closely align with the patient population they serve [ 5 , 34 ].

For the “career” MAs, we heard that opportunities that allow for advancement within their current MA profession may increase job satisfaction and thereby retention with its downstream financial and organizational benefits [ 10 , 11 ]. Literature outside healthcare also suggests that organizations can benefit when promoting from within, given that employees retain institution-specific knowledge that increases productivity [ 42 , 43 ]. We note major barriers to facilitating MA advancement within their current roles include licensing restrictions and common staffing structures in primary care—MA role expansion may mean MAs have taken over the historical positions they might have once stepped up into. Some primary care settings, including those in this analysis, are actively exploring further specializing MA roles based on additional training in mental health, population health management, or value-based care [ 5 , 44 ]. These opportunities may facilitate higher level advancement-in-place opportunities for MAs without requiring years of additional training.

We recognize another tension in that local clinic needs can vary significantly, and each may require different competencies from their MAs (e.g. phlebotomy, population health measures). This goes against MAs’ voiced desire that a career ladder consistently reflect competencies across an organization. Based on our overall findings, is seems that allowing for some local clinic-level flexibility to facilitate advancement-in-place opportunities may outweigh MA desire for career ladder consistency across the organization. Administrators must recognize and balance this tension in their efforts to optimize career ladder design.

Underlying these conversations was the dominant theme of MA role expansion in the last several years. While prior work has largely emphasized the benefits of this transition [ 5 , 15 , 16 ], we were struck by the unfavorable perspectives many MAs held when role expansion was discussed in the context of their career progression and, indirectly, compensation. In particular, MAs seemed to recognize they were providing more value to the health system than before, generally without increased compensation; this manifested in the perception that their organizations did not value them. It appears that career ladders, if implemented effectively, may begin to combat negative MA perceptions of fairness in their workplace, thereby improving “organizational justice” and retention [ 45 , 46 ]. Fortunately, despite these sentiments, early literature based on a subset of the population represented here suggests MAs do not experience significantly elevated rates of burnout [ 13 ], though additional study is needed.

Focus groups within three institutions across two geographies cannot encompass the full range of MA perspectives across the U.S., particularly as licensing laws vary from state to state. This evaluation reflects learnings to inform institutional practices, and extrapolation to outside settings is therefore limited. Future efforts to understand and optimize career ladders may benefit from expanded participation from administrators and MAs from diverse settings. Furthermore, we acknowledge two institutions at the time of interviews were working on career ladder improvements; this period of ongoing change may have reduced overall MA knowledge and satisfaction with the pre-existing programs. Additionally, we are unable to provide specific examples of the career ladders at each institution due to variation between clinic sites and ongoing revisions to their structures; understanding these trends is an area for future research. Our use of focus groups may also have limited certain individual disclosures, though we felt the benefits from a synergistic discussion with multiple voices outweighed that risk. Finally, the focus group structure also prohibited us from making comparisons on MA perceptions between racial/ethnic groups, which may be an important area of future study.

Conclusions

MA roles have undergone significant expansion in recent years, and identifying the right balance between organizational and employee needs is ongoing. Career ladders are perceived favorably by MAs in principle but their practical implementation merits further attention. Segmenting MAs into distinct clusters based on their career aspirations may serve as a useful model to further tailor career ladders to employee needs, though additional evaluation is still needed. Such efforts have the potential to strengthen the healthcare workforce and talent pipeline, with downstream benefits to patient care and operational efficiency.

Availability of data and materials

Original qualitative interview recordings and transcripts will not be shared given possible risk to individual privacy. For questions related to the data, please contact Dr. Stacie Vilendrer at [email protected] .

Abbreviations

Medical assistant

Focus group

Continuing medical educator

Findlay S. Implementing MACRA. Health Policy Briefing. Published March 27, 2017. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/03/implementing-the-medicare-and-chip-reauth-act.html .

Reiss-Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, et al. Association of Integrated Team-Based Care with Health Care Quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA. 2016;316(8):826–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.11232 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The Teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(5):457–61. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.731 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Anderson P, Halley MD. A new approach to making your doctor-nurse team more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15(7):35–40.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(S1):383–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12602 .

Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):226–35. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170341 .

Dill J, Morgan JC, Chuang E, Mingo C. Redesigning the Role of Medical Assistants in Primary Care: Challenges and Strategies During Implementation. Med Care Res Rev. Published online August 14, 2019:107755871986914. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558719869143 .

Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. Medical Assistants.; 2020. Accessed 14 Aug 2020. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/medical-assistants.htm .

Nelson K, Pitaro M, Tzellas A, Lum A. Transforming the role of medical assistants in chronic disease management. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):963–5. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0129 .

Article Google Scholar

Taché S, Chapman SA. Medical assistants in California. San Francisco: University of California; 2004. https://healthforce.ucsf.edu/sites/healthforce.ucsf.edu/files/publication-pdf/7.%202004-05_Medical_Assistants_in_California.pdf . Accessed 14 Aug 2020

Google Scholar

Friedman JL, Neutze D. The financial cost of medical assistant turnover in an academic family medicine center. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(3):426–30. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2020.03.190119 .

Taché S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manage. 2010;24(3):288–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777261011054626 .

Seay-Morrison TP, Hirabayshi K, Malloy CL, Brown-Johnson C. Factors affecting burnout among medical assistants. J Healthc Manag. 2021;66(2):111–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/JHM-D-19-00265 .

Vilendrer S, Brown-Johnson C, Kling SMR, et al. Financial incentives for medical assistants: a mixed-methods exploration of Bonus structures, motivation, and population health quality measures. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(5):427–36. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2719 .

Bodenheimer T, Willard-Grace R, Ghorob A. Expanding the roles of medical assistants: who does what in primary care? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1025–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1319 .

Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning Medical Assistants for a Greater Role in the Era of Health Reform. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1347–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000775 .

Ilbawi NM, Kamieniarz M, Datta A, Ewigman B. Reinventing the medical assistant staffing model at no cost in a large medical group. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(2):180. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2468 .

Shekelle PG, Begashaw M. What are the effects of different team-based primary care structures on the quadruple aim of care? A Rapid Review: Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568333/ . Accessed 21 Jan 2022

Willard-Grace R, Najmabadi A, Araujo C, et al. “I Don’t See Myself as a Medical Assistant Anymore”: Learning to Become a Health Coach, in our Own Voices. i.e inquiry in education . 4(2).

Dill JS, Morgan JC, Weiner B. Frontline health care workers and perceived career mobility: do high-performance work practices make a difference? Health Care Manag Rev. 2014;39(4):318–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0b013e31829fcbfd .

Dill J, Morgan JC, Chuang E. Career ladders for medical assistants in primary care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3423–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06814-5 .

Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61(3):181–91.

Dill JS, Chuang E, Morgan JC. Healthcare organization–education partnerships and career ladder programs for health care workers. Soc Sci Med. 2014;122:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.021 .

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptualdistinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. PMID: 20957426; PMCID: PMC3068522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 .

United States Census Bureau: Urban and Rural. Published February 24, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural.html . Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Brown-Johnson C, Safaeinili N, Zionts D, et al. The Stanford lightning report method: a comparison of rapid qualitative synthesis results across four implementation evaluations. Learn Health Syst Published online December 21. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/lrh2.10210 .

Kitzinger J. Qualitative research: introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, vol. 5. Paperback print. Aldine Transaction; 2010.

Hallberg LRM. The “core category” of grounded theory: making constant comparisons. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2006;1(3):141–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620600858399 .

Sbaraini A, Carter SM, Evans RW, Blinkhorn A. How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):128. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-128 .

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 4th ed: SAGE; 2020.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 .

Bates T, Hailer L, Chapman SA. Diversity in California’s health professions: current status and emerging trends: The Public Health Institute and the UC Berkeley School of Public Health; 2008. https://healthforce.ucsf.edu/sites/healthforce.ucsf.edu/files/publication-pdf/10.%20Diversity-in-Californias-Health-Professions-Current-Status-and-Emerging-Trends.pdf . Accessed 28 Jan 2021

Sex, Race, and Ethnic Diversity of U.S, Health Occupations (2011–2015). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis; 2017.

Yohn DL. Design your employee experience as thoughtfully as you design your customer experience. Harvard Business Review. Published online December 8, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/12/design-your-employee-experience-as-thoughtfully-as-you-design-your-customer-experience .

Duffield CM, Roche MA, Homer C, Buchan J, Dimitrelis S. A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(12):2703–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12483 .

Zhang X, Tai D, Pforsich H, Lin VW. United States registered nurse workforce report card and shortage forecast: a revisit. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(3):229–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617738328 .

Hayes LJ, O’Brien-Pallas L, Duffield C, et al. Nurse turnover: a literature review – an update. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(7):887–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.001 .

Waldman JD, Kelly F, Aurora S, Smith HL. The Shocking Cost of Turnover in Health Care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(1):2–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004010-200401000-00002 .

Scheinman SJ, Ryu J. Why a teaching hospital offers an employment-based tuition waiver program. NEJM Catalyst. Published online June 26, 2019. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.19.0646?casa_token=_ugA89cfTkgAAAAA:JcOwSI1AYL9wez4fMx0X8J0h_Fk9KEmNol7VLV3WGnREa9e8upBd8HPW20_HBWszDU0lv_jWDYEIVj8 .