- Browse by Year

- Browse by Subject

- Advanced Search

Welcome to LSE Research Online

Welcome to LSE Research Online, the institutional repository for the London School of Economics and Political Science. LSE Research Online contains research produced by LSE staff, including journal articles, book chapters, books, working papers, conference papers and more. Use the "Browse" functions above to look for items by year, Department, or Research Group. For a quick search, use the search box below

supports OAI 2.0 with a base URL of /oai2

Browser does not support script.

- Current Students

- PhD Job Market

- Centres and units

International Relations research

Find out about our research community, and the research in the Department of International Relations

Research news and highlights

Watch video: Are there elections taking place in wartime?

Mariia Zolkina, DINAM Research Fellow, explains the cases of Ukraine and Russia

COVID-19: research and writing Read the contributions from our faculty and students on the global pandemic

Research Excellence Framework 2021 Results Read more about our REF 2021 results

The downsides of being a nuclear superpower Lauren Sukin explains the circumstances when a country's strength can also be a disadvantage

What really went wrong in the Middle East Fawaz Gerges explains America’s concern over Communist Russia led to poor foreign policy decisions

VIDEO: The Battle for the White House Professor Peter Trubowitz outlines what you need to know about the 2024 US election

Video: 2024 a year of unpredictable elections Professor Michael Cox sets out the year before us

Research: Noah Zucker's research explores why climate change is moving to the fore of the global governance agenda

Global Politics: A year of elections Explore the debates at the forefront of politics and the implications of key elections

Why does India want to be a space power? Chandrayaan-3 and the politics of India’s space programme Dimitrios Stroikos explores how India’s space programme has developed.

Video: The international politics of outer space Chris Alden and Dimitrios Stroikos explore complexities around the international politics of space

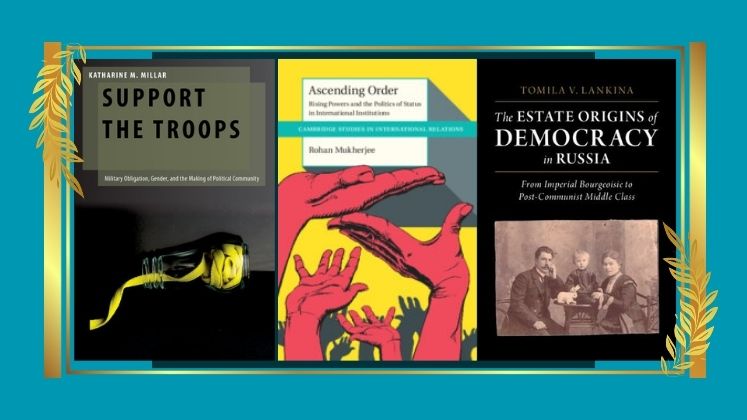

Three of our faculty have won prestigious book prizes Congratulations to Rohan Mukherjee, Katharine Millar and Tomila Lankina! Click to find out more.

publications and media.

Research news Read about the latest research from the department

New books Latest publications from the IR faculty

Research on IR Blog Read the latest research articles from our department on the IR blog

research students and early career researchers .

IR MPhil/PhD programme Find out about our research degree

Research Community Meet our MPhil/PhD students

PhD Job Market Candidates Find out more about our PhD candidates who are entering the job market

Researcher Profiles: Q&As with our PhD students Read about their current research

Careers of LSE IR PhD students

research clusters.

Introduction Find out about our research and our research clusters

Our research on International Institutions, Law and Ethics

Our research on Theory/Area/History

Our research on International Political Economy

Our research on Security and Statecraft

impact.

Knowledge Exchange and Outreach Find out more about the impact of our research

Promoting policy reforms in the Philippines by Thinking and Working Politically in development REF Impact 2021: John Sidel contributed to policy reform advocacy in the Philippines

Influencing EU policy on international trade agreements ITPU provided expert analysis on trade agreements for EU's International Trade Committee

Strengthening global regulation of emerging nanotechnologies Research has highlighted the importance of transparency and reporting for nanotechnology products

Strengthening policies to protect human rights and prevent genocide LSE research influenced EU policies intended to protect human rights and to prevent genocide

David Davies of Llandinam [DINAM] Research Fellowship Find out more

Millennium Journal of International Studies More about our prestigious student-edited journal

Journals and book series associated with the department. Find out more

LSE Research Online articles, chapters etc from the IR department

Appointment of academic visitors Information and how to apply

centres and units associated with us.

LSE Middle East Centre A central hub for the wide range of research on the Middle East and North Africa carried out at LSE

LSE IDEAS Think tank connecting academic knowledge of diplomacy and strategy with the people who use it

Phelan United States Centre A hub for global expertise, analysis and commentary on America

European foreign policy unit expertise on a collective european foreign policy, global south unit examining the changing role of the south in the global order, international trade policy unit serves the academic, policy, and business community, religion and global society unit conducting religion-related social science research, browse all lse ir centres, units and groups, find out more.

LSE Theses Online

Browse the archives of theses from the IR Department

LSE Research Ethics

Guidance on LSE research ethics, code of research conduct and training

Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Promoting equitable treatment, championing diversity and developing an inclusive LSE

PhD and Research Team: Sarah Hélias and Amy Brook Please email [email protected] to arrange an appointment.

Research and MPhil/PhD programme enquiries [email protected]

Address View on Google maps

Department of International Relations, Centre Building (10th floor), Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE

Follow our new Department page on LinkedIn

Browser does not support script.

- Autumn Term events schedule

- Student Voice

- You've got this

- LSE Volunteer Centre

- Key information

- School Voice

- My Skills and Opportunities

- Student Wellbeing Service

- PhD Academy

- LSE Careers

- Student Services Centre

- Timetable publication information

- Students living in halls

- Faith Centre

Collect and analyse data

Whether you’re doing primary, empirical research or a desk-based research project, or a combination of the two, you’ll be gathering things. This could include documents, historical archives, photographs, audio or video files, statistical datasets, and more. If you’re planning to use primary or secondary data for your project, you’ll need to give careful thought to your research design, particularly the methods you’ll use to collect and analyse your data.

What are some data collection options?

Just sit down and chat, right? No! Interviews are structured dialogues, designed to elicit information, and so are an efficient way of gathering rich and focused data. There are several steps to the interview research design, with sampling, interview topic guides, and interview questions needing to be given some planning.

For guidance, check out the Methodology Department's course on qualitative research methods (MY421) ' in - depth interviews ' week.

Focus groups

Focus groups are organised, facilitated discussions, that try to recreate natural conversations, and for which the group interaction is the data. It’s good to know both why and when to use focus groups. When constructing and conducting a focus group, there are three key design considerations : number of participants, diversity and number of groups. Like anything, focus groups have their strengths and challenges, so it is worth looking into what makes a good focus group .

Want more information? Check the Methodology Department's course on qualitative research methods (MY421) ‘ focus groups ’ week.

Case studies

Case studies are an empirical investigation into a particular phenomenon within a real life context (Yin, 2009). It's useful to be aware of the different types of case studies and methods of analysis, as well as what case studies are good for and their fundamental issues. To know more, check out the Methodology Department's course on Social Science Research Design (MY400) ‘ case studies and comparable cases ’ week. ‘ What is a case study and what is it good for ’ (Gerring, 2004) is also a good introductory read.

What can I do to analyse my data?

Thematic analysis.

Thematic analysis is a process of making sense of a situation and synthesising texts , by going from words to codes (what and how) to themes (how and why) to global themes (why and argument). Thematic analysis is an iterative process, and a good thematic analysis requires you to read, re-read, (re-)label, and (re-)categorise, before you begin writing.

For help, check the Methodology Department's course on qualitative research methods (MY421) Thematic Analysis I and Thematic Analysis II . A good introductory read is ‘Thematic networks: an analytical tool for qualitative research’ (Attride-Stirling, 2001)

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis is a way to consider texts as a form of social interaction. There are of course different views on what "discourse" means . There are also different approaches to how to conduct a discourse analysis . To learn more, explore the Methodology Department's course on qualitative research methods (MY421) ‘ discourse analysis’ week.

Quant analysis

Sometimes only numbers will do. If you're new to quantitative research methods, you'll want to check out the Methodology Department's ‘ introduction to quantitative analysis’ (MY451) and their intermediate course (MY465) , too. Another helpful resource could be the Statistics Department's course on market research (ST327) -- particularly the material on surveys and questionnaires .

What tools are available?

Data collection.

The suggested software for running a survey is Qualtrics. Apply for a free Qualtrics account via DTS.

Data analysis

NVivo, SPSS, R, and Stata are all installed as standard on LSE PCs, and you can apply for a licence for your own computer via the DTS specialist software page .

NVivo can be used in qualitative and mixed methods research to analyse and code text, as well as manage survey and interview data. Check out the Digital Skills Lab online introduction to Nvivo or the Methodology department's Youtube playlist for more.

SPSS, R, and Stata are all used for quantitative analysis. The Methodology department's Youtube page has video demos of analysis software packages in action - SPSS and Stata .

Who can I speak to?

Designing and carrying out research is exciting, rewarding, and challenging! Talk through your research design with experts at the Methods Surgery (offered by the Methodology Department in the Spring Term only).

The Digital Skills Lab runs daily drop-in support sessions for software, including NVivo, Qualtrics, SPSS, Stata, R, and more. Find out more about Research Software drop-in sessions .

You could ask...

- My research plans have changed! What should I consider now to implement my Plan B?

- How can I make sure my online survey, interview guides, or other research instrument makes sense to participants?

- Does my project require ethical clearance or review?

- Where can I learn more about a particular method independently?

Events and resources

Conduct effective interviews

Working with your data: think about data collection clearly and logically

Working with your data: connect your data analysis with your literature review and research question

Practical tips for

qualitative research

thematic analysis

discourse analysis

working with research participants

planning, conducting, and transcribing interviews

Plan and conduct responsible, ethical research

Conduct primary research online

SAGE Research Methods

How do your research methods fit into the big picture of your research story?

Is there past research that uses similar data collection or analysis methods ?

How can you ensure that your data files and your work are saved securely? Are there any ethical considerations?

- Browse by author

- Browse by year

- Departments

- History of Thought

- Advanced search

In this thesis, I draw on Hannah Arendt’s extensive body of work, encompassing her constitutional and non-constitutional writings, to present an Arendtian constitutional theory. I suggest that active citizenship is the normative and critical focal point of an Arendtian understanding of democratic constitutionalism as a system of governance. I examine and develop citizenship as a freedom that is experienced in collective action and in taking responsibility for collective action. Sourcing insights from Arendt’s discussion of the Greek and Roman conceptions of law, I argue that for Arendtian constitutional theory, democratic constitutionalism requires the establishment of structures for citizens to experience political freedom and to take responsibility for the preservation of the constitutional order. I conduct an examination of Arendt’s discourse on freedom, power, and authority to reveal how, in a constitutional democracy, active citizenship is intrinsically connected with the maintenance of a constitutional order. Citizens act and judge through participation in ordinary politics to generate and preserve constitutional principles. I conclude the thesis by emphasising the significance of civil disobedience in a democratic constitutional setting. In my reading, Arendt views civil disobedience as the citizens’ attempt at creating a temporary, extra-institutional political space to preserve constitutional principles in the face of a loss of power and authority of the constitutional institutions. I propose that an Arendtian emphasis on theorising civil disobedience as an intrinsic part of the ordinary politics of a democratic constitutional order implies, on the part of the institutions, a duty to establish structures and platforms for citizens’ right to action and dissent, and on the part of the citizens, a duty to preserve and maintain the constitutional order. Such a conceptualisation, I argue, contributes a unique and nuanced understanding of how citizens actively contribute to and interact with the foundations of democratic constitutional governance.

Actions (login required)

Downloads per month over past year

View more statistics

Browser does not support script.

- Using the Library

- What's on

- Collection highlights

- Research support

Access archives and special collections

Open to everyone that wants to use our collections, the reading room on the 4th floor is called the women's library reading room and is where all our archives and special collections material can be accessed., opening hours.

- 10am to 4pm, Monday to Friday.

Make an appointment to visit our reading room

Get in touch in advance as it can take up to 5 working days to arrange access.

If you already have access to LSE Library

- Email us to arrange an appointment . Provide 2 working days' notice.

If you don't have current access to LSE Library

- You must follow the process on the visitor access to LSE Library and Archive page.

Beginning your research

Search our catalogues to identify material that is relevant to your research.

- Use Library Search to find books, articles and pamphlets.

- Search the archives catalogue for LSE and the Women's Library archives.

Requesting material for use in the reading room

You can request up to 3 items in advance of your visit and additional material when you are here. We retrieve material at the following times:

- 10.30am, 12pm and 2.30pm

Please allow up to an hour for material to be retrieved.

Take your own photographs of items. Flash photography and scanners are not permitted.

Make sure you follow copyright guidance. Responsibility for infringement of copyright is borne by the person making the copy, and the person (if different) for whom the copy is being made.

Read our guide to copying archival material

What can i take images of in the reading room.

You may take images of any item from the collections, as long as it’s for non-commercial research purposes.

Are there any limits on how much I can copy?

Yes. Fair dealing applies to all copyright works and suggests limits as follows:

- One article from a journal

- One chapter from a book

- One short story or poem from an anthology

- Up to 5% extracted from a work

You may only make one copy and that must only be used for non-commercial research or private study, or for criticism, review or news reporting.

What if I want to use an item in my book/article/website?

The only permitted use for making copies of copyrighted works in the Reading Room is for non-commercial purposes. If you wish to make copies with the intention of publishing then you must provide written permission from the copyright holder(s) first, or obtain a licence for publishing orphan works from the Intellectual Property Office.

There are no restrictions on copying and publishing works that are out of copyright.

How do I know if a work is out of copyright?

Copyright is a very complicated area and it can be difficult to determine whether something is in copyright or not, and consequently what you can do with it. The following is a guide, and should not be considered as legal advice:

- Copyright in published works expires 70 years after the death of the author

- Copyright in unpublished works, regardless of age, expires 31st December 2039

- Copyright in published works with no specified author expires 70 years after publication

- Copyright in photographs where the photographer is unknown expires 70 years after creation

Unpublished works, though still in copyright, may be published without infringement if the work was created before 1 August 1989; and the author has been dead for more than 50 years; and the work is more than 100 years old.

How do I find out who the copyright holder is?

There are a variety of sources to try, such as the WATCH database, DACS , the National Portrait Gallery (for photographers), and Who Was Who .

It is your responsibility to gain permission from the copyright holders if you intend to publish any of the images you take in the Reading Room.

Can LSE Library trace copyright for me?

Very rarely: in a small amount of cases we have up to date contact details for copyright holders or their estates, and we are willing to pass permission requests on for you.

LSE Library cannot grant permission to publish works where the copyright is held by a third party.

What photography equipment can I bring?

All equipment that will fit on a Reading Room table is permitted with the following exceptions:

- Flash photography is not permitted under any circumstances

- The use of portable or flat-bed scanners is not permitted

- Users must disable electronic camera sounds and avoid disturbing other users

There is no dedicated space for photography in the Reading Room, but we are happy to sit users close to a window to maximise natural light. The Reading Room has ceiling lights and adjustable lamps on the desks. You are welcome to bring props to shield/scatter light as long as they do not encroach onto another user space. We place no restrictions on the quality of images taken, and we do not charge a fee for using a camera.

Digital scanning service

Digital scans of archives and special collections items can be ordered for personal use. The service is free and aimed at researchers wishing to consult small amounts of material remotely.

Each request will be considered on a case-by-case basis. We aim to produce scans, subject to condition approval and appropriate copyright restrictions, within ten working days.

Contact us regarding your request .

Further help

Contact us if you need assistance identifying material relevant to your research.

Search the archives catalogue

Explore collection highlights

Browse Charles Booth's London

Explore our Google Arts exhibits.

Browse LSE Digital Library collections.

Discover our images on Flickr.

I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy.

INTRODUCTION

COMPLETED PAPERS

The Merit of Misfortune: Taiping Rebellion and the Rise of Indirect Taxation in Late Imperial China, 1850s-1900s

Reexamine the Restoration: Fiscal Capacity and Industrialization in Modern China, 1860s-1930s

Fiscal Decentralization, Historical Legacy and Economic Performance: Empirical Evidence from Coastal Prefectures in China, 2010-2015

MONOGRAPH IN PROGRESS

A History of Decentralization: Fiscal Transitions in Late Imperial China, 1850-1911

PAPERS IN PROGRESS

I undertake the teaching tasks at Fudan University from fall 2022 .

Poli620041/poli820013. research methods for social sciences (社会科学研究方法), i taught undergraduate and postgraduate seminars at the london school of economics during 2017-21., eh207. the making of an economic superpower: china since 1850, eh240. business and economic performance since 1945: britain in international context, eh401. historical analysis of economic change, eh40 2 . research design and quantitative methods in economic history, other campus events - student & alumni discussion. literary history and selected reading for modern and contemporary china (现当代文学史与作品选读).

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Use of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT™) for end-of-life discussions: a scoping review

- Melanie Mahura 1 ,

- Brigitte Karle 2 ,

- Louise Sayers 3 ,

- Felicity Dick-Smith 3 &

- Rosalind Elliott 3 , 4

BMC Palliative Care volume 23 , Article number: 119 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

98 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

In order to mitigate the distress associated with life limiting conditions it is essential for all health professionals not just palliative care specialists to identify people with deteriorating health and unmet palliative care needs and to plan care. The SPICT™ tool was designed to assist with this.

The aim was to examine the impact of the SPICT™ on advance care planning conversations and the extent of its use in advance care planning for adults with chronic life-limiting illness.

In this scoping review records published between 2010 and 2024 reporting the use of the SPICT™, were included unless the study aim was to evaluate the tool for prognostication purposes. Databases searched were EBSCO Medline, PubMed, EBSCO CINAHL, APA Psych Info, ProQuest One Theses and Dissertations Global.

From the search results 26 records were reviewed, including two systematic review, two theses and 22 primary research studies. Much of the research was derived from primary care settings. There was evidence that the SPICT™ assists conversations about advance care planning specifically discussion and documentation of advance care directives, resuscitation plans and preferred place of death. The SPICT™ is available in at least eight languages (many versions have been validated) and used in many countries.

Conclusions

Use of the SPICT™ appears to assist advance care planning. It has yet to be widely used in acute care settings and has had limited use in countries beyond Europe. There is a need for further research to validate the tool in different languages.

Key message

What is already known on this topic?

• The SPICT ™ was developed to assist clinicians to screen patients for palliative care needs.

What this review found.

• The SPICT™ assists conversations about advance care planning and facilitates changes in documented goals of care.

• The SPICT™ is available in at least eight languages (and used in many countries.

How the findings of this review may affect practice and research.

• Evidence suggests that formalising screening for palliative care needs using the SPICT™ is advantageous for advance care planning; clinicians should consider using the SPICT™ to initiate discussions with people with life limiting conditions.

• Further research is required to validate the tool in different languages and extend its use in acute care settings and with other patient cohorts.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The demand for palliative care services globally has outpaced service availability, particularly in low and middle-income countries [ 1 ]. This is expected to continue as the population ages and the burden of noncommunicable disease increases. Thus, non-specialist palliative care health professionals may be required to manage care. The Supportive And Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT™) [ 2 ] is one instrument available for non-specialist palliative care clinicians which may assist them in assessing unmet palliative needs and care planning.

Evidence suggests that clinicians feel inadequately prepared to conduct end-of-life discussions with patients who are terminally ill [ 3 , 4 , 5 ] and are also unsure of the appropriate time to start these discussions or whether to involve a specialist palliative care team [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Clinicians have reported their discomfort when addressing the topic of death with seriously ill patients [ 5 ].

From the perspective of patients with advanced illness, honest information from a trusted health care professional is the preference of most [ 7 ]. A survey study conducted in Canada involving 434 patients with advanced illness found over half of patients felt it was ‘very important’ to have a sense of control over decision-making regarding their care and 56% felt it was ‘extremely important’ not to be kept alive on life support if there was little hope of recovery [ 7 ]. The default medical decision to do everything to save life may be contributing to delays in referral to a specialist palliative care team, burdensome medical treatment and poorer quality of life for many patients [ 8 ]. Thus, a standardised, reliable and validated method of assessing and planning care in collaboration with the patient is required.

The terms ‘end-of-life’ and ‘terminally ill’ have been conceptualised as synonymous and ‘apply to patients with progressive disease with months or less of expected survival.’ [ 9 ]. In the United States there is consensus that referral to specialist palliative care services is required at the time of diagnosis for patients with neurologic disease, frailty, multimorbidity, advanced cancer, organ or cognitive impairment, patients with a high symptom burden and patients with onerous family or caregiver needs [ 10 ]. However with an ageing population and increased levels of dementia and frailty non-palliative care clinicians need a tool with a common language to identify those who are nearing the end of life and to promote a palliative approach to care. According to the High Authority for Health, an independent organisation that promotes quality outcomes in the fields of health, sociology and medicine a palliative approach is, “a way of addressing end-of-life issues early on: make time to talk about ethical questions, psychological support, comfort care, the right care, and give a timely thought to the likely palliative care needs of people approaching the end-of-life.” [ 11 ], p1.

Advance care planning, “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care” [ 12 ] is one aspect of palliative care often provided by medical professionals which may assist in ensuring people’s needs are met, and care and communication are enhanced. Early advance care planning is vital, particularly for patients with neurodegenerative conditions before they lose capacity to express their wishes [ 8 ] “to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences during serious and chronic illness.” [ 12 ] Research has revealed that patients who have had the opportunity to discuss their preferences at the end-of-life are more likely to receive care that is consistent with those preferences. Findings also include greater patient and carer satisfaction and less conflict regarding decision making when end-of-life preferences have been examined [ 13 ].

People who have life limiting conditions may benefit from the delivery of advance care planning using a systematic approach. The SPICT™, although not designed for this purpose may enhance the approach particularly when health professionals who have limited palliative care experience are required to facilitate advance care planning.

The SPICT™ [ 2 ] was designed to identify patients at risk of deteriorating or dying and to screen for unmet palliative care needs. The tool includes general indicators of deterioration and clinical indicators of life-limiting conditions. The accompanying SPICT™ guide provides prompts and tips and a suggested framework (REMAP Ready, Expect, Diagnosis, Matters, Actions and Plan) [ 14 ] for conducting future care planning conversations. The tool is reported to be simple to use and designed for use by all multidisciplinary team members in any care setting [ 13 ].

The SPICT™ was evaluated using a mixed methods participatory approach [ 2 ]. Peer review and consensus was gathered for the 15 revisions of the SPICT™ over an 18-month period. Each iteration of the tool was distributed to clinicians and policy makers internationally until consensus was reached [ 2 ]. The research team worked concurrently with clinicians in four participating units at an acute tertiary hospital in Scotland to screen all patients with advanced organ disease whose admission to hospital was unplanned ( n = 130) using a checklist that included the SPICT™ general indicators, disease specific indicators and the surprise question (SQ), “Would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next 6 to 12 months?”. Data were gathered over an 8-week period and patients were followed up for 12 months [ 2 ]. A significantly greater number of patients who died at 12-months had two or more admissions in the previous 6 months before being screened. These patients also had increased care needs and persistent symptoms despite optimal treatment. The researchers proposed that better identification, assessment and pre-emptive care planning could reduce the risk of unplanned hospital admission and prolonged inpatient stays [ 2 ]. Of note the patients’ diagnoses were limited to advanced illness which was non-malignant and ethnicity was homogenous [ 2 ]. The SQ was removed from subsequent versions of the SPICT™ and the rationale for removing it remains unclear. The SPICT™ continues to be revised and versions are available in different languages [ 2 ].

The intention of this review was to examine the impact of the SPICT™ on advance care planning and the extent of its use. The patient cohorts, languages, and contexts in which the SPICT™ is available and used were examined.

Review questions

The following primary question was addressed:

How does use of the SPICT™ assist with conversations about advance care planning?

Secondary review questions were:

What is the extent of the use of the SPICT™ (which patient cohorts, contexts, and countries is it used)?

In which languages has the spict™ been validated.

Does use of the SPICT™ facilitate changes in documented goals of care?

Design and methods

This scoping review was performed in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis Scoping Review Framework [ 15 ] and the Meta-Analyses Scoping Review extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [ 16 ] was used to guide the reporting.

Preliminary literature search

An initial search focussed on inpatients with a chronic illness nearing the end of life however the search was expanded to include all care settings where the SPICT™ was being used for adults with a life-limiting chronic illness to evaluate its efficacy in advance care planning. Thus the search reflected the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care definition of palliative care “the active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness, and especially of those near the end of life.” [ 17 ]. A life-limiting illness or condition encompasses both malignant and non-malignant diseases as well as the effects of ageing.

A preliminary search of EBSCO Medline, the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, Prospero and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted in June 2022. No current or planned systematic or scoping reviews specifically on this topic were identified. A systematic review by Teike Luthi, et al. [ 18 ], examining instruments for the identification of patients in need of palliative care in the hospital setting was identified. The current scoping review differs from the systematic review by Teike Luthi, et al. [ 18 ] as the aim was to identify and describe all research related to how the SPICT™ is used in end-of-life discussions and what influence this has on advance care planning and goals of care.

Inclusion criteria

Participants.

The population of interest was adult patients (> 18 years) with a life-limiting chronic illness.

The concept of interest was the SPICT™. Any studies incorporating the SPICT™ were included in this review since its development in 2010. Studies evaluating the SPICT™ for prognostication purposes were excluded as this was not the intent of this review.

Published and unpublished studies in any language for which a translation could be obtained were included. Published and unpublished studies in any setting that met the eligibility criteria were included.

Evidence sources

This scoping review included both experimental and quasi-experimental study designs. In addition, analytical observational studies including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies and analytical cross-sectional studies were considered for inclusion. Systematic reviews that met the inclusion criteria were included. Qualitative studies, theses and dissertations were also considered if they met the inclusion criteria.

Search strategy

An initial search on this topic in the EBSCO Medline and PubMed databases was reviewed for relevant abstracts and titles to determine keywords and index terms. MESH terms used in the final search strategy included: Communication; Documentation; Palliative Care; Patient Care Planning; Advance Care Plan; Decision Making and Chronic Disease. The research abstract for this scoping review was registered on the Center for Open Science website ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DN27C ) in August 2022 prior to performing the definitive search in September. The search was conducted on 28th September 2022 and date limited i.e., 2010-September 2022. The database and grey literature searches were updated on 27th January 2024 to identify further studies published beyond this date.

Electronic databases searched included EBSCO Medline, PubMed, EBSCO CINAHL, APA Psych Info, ProQuest One Theses and Dissertations Global. Publications listed on the SPICT website ( www.spict.org.uk ) were cross checked with the records included from the electronic databases, duplicates were removed and further records were added to the Endnote library for screening. Reference lists of included studies were reviewed for additional studies.

All websites searched for additional records (grey literature sources) are included in supplementary file 1 . The expanded search strategy for the EBSCO Medline database is also provided in supplementary file 1 .

Study selection

All records were collated in an EndNote library. Duplicate records were removed manually by RE. The screening process involved two independent reviewers (MM and RE) reading titles and abstracts. Full text screening was conducted independently by the same two reviewers. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers at each stage of the process was resolved following review and consultation of a third reviewer (BK). Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded with a reason recorded. Data extracted from included studies has been recorded in the standardised data extraction form (supplementary file 2 ). Critical appraisal of included studies was not performed and thus studies were not excluded based on methodological quality.

Data synthesis

Key aspects of the included studies were summarised in tables. Also consistent with the approach for a scoping review a textual narrative synthesis [ 19 ] was performed with the primary aim of addressing the review questions.

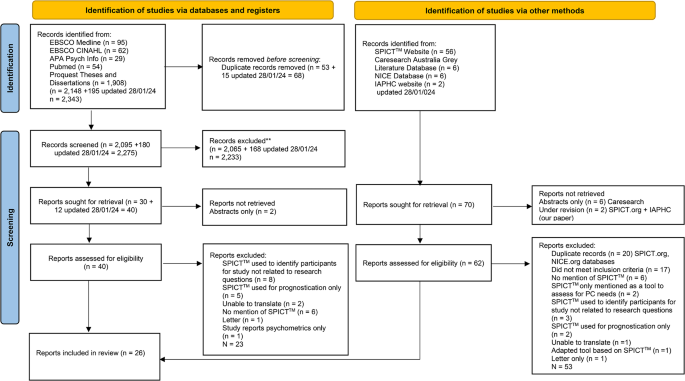

Over 2,000 records were retrieved. Five guidelines and six conference abstracts were found but these either did not relate to the review questions or did not contain sufficient information to be included. After applying the exclusion criteria 26 reports were included in this scoping review. The flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) presents the number of records retrieved, screened, excluded and included.

Flow diagram of number of records retrieved, screened, excluded and included **Abstract and title screening involved assessing each record for relevance to the review questions i.e., if no mention of the SPICT™ or/and advance planning conversation the record was excluded from further consideration

There were multiple study designs including validation and translation ( n = 8) studies [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ] and clinical improvement projects ( n = 3) [ 28 , 29 , 30 ]. The focus of the clinical improvement projects was to increase the identification of palliative care needs and care planning through the use of the SPICT™. Two reviews (one of these included a survey study) 18 31 and two theses were included 28 29 (Table 1 ).

Research reveals that the SPICT™ appears to assist clinicians with conversations about advance care planning by providing a proforma for essential aspects of end-of-life care, a framework for end-of-life conversations and a common language to collaborate within the multidisciplinary team.

For example, in a prospective exploratory feasibility study to explore the practical use of the SPICT™ resulted in increased palliative care planning [ 32 ]. In this study general practitioners (GPs) [ n = 10] were trained in the use of the German version of the SPICT™ (SPICT-DE™) and during a two-month intervention period were asked to use the tool with any adult patients diagnosed with a life-limiting disease ( n = 79) and these patients were followed up at 6 months. The GPs’ actions as recommended by the SPICT-DE™ were considered appropriate with the most frequent actions being “Agree a current and future care plan with the person and their family; support family carers” ( n = 59 [75%)),“Review current treatment and medication to ensure the person receives optimal care; minimise polypharmacy”( n = 53 [67%]), and “Plan ahead early if loss of decision-making capacity is likely”(n = 49 [62%]). Of note “Consider referral for specialist palliative care consultation to manage complex symptoms” was considered appropriate for 25 (32%) patients. The effect of the SPICT™ was evident at the 6-month follow-up; the most frequently initiated actions were “Review current treatment and medication to ensure the person receives optimal care; minimise polypharmacy” (n = 36 [46%]) and “Plan ahead early if loss of decision-making capacity is likely” (n = 29 [37%]).

Further implementation research by Afshar et al. [ 33 ] with GPs in Germany revealed that GPs considered that the tool supported the communication and coordination of care and considered it broadened their perspectives of the meeting the needs of people especially those with non-cancer diagnoses. Of note over 50% of patients in this study had their agreed care plan initiated at the 6-month follow-up. Some GPs who had extensive experience and training claimed that the tool had no effect on their practice. However overall more than two thirds of the sample reported that they could envisage using the SPICT-DE™ in everyday practice.

In addition, three studies found that nurses who were trained to use the SPICT™ increased their self-efficacy in identifying patients who may be nearing the end of life and promoted an advance care plan discussion with these patients 28 29 34 . 21−23 In the study set in a renal ward, patients were screened on admission to identify those nearing the end of life by nurses using the SPICT™ [ 34 ]. An alert was added to the ward patient name list when a patient was identified as nearing the end of life (‘SPICT™ positive’) which prompted a review by the physician and multidisciplinary team. In this study 16% (25/152) of newly admitted patients were screened as ‘SPICT™ positive’; all of these patients received a palliative care consult and were discharged with an advance care directive including a resuscitation plan [ 34 ]. Incidentally nurses reported a significant increase in their ability to identify patients approaching end of life.

Similarly high SPICT™ screening rates and end of life conversations and referrals were revealed in a clinical improvement project designed to improve palliative care screening and consultation on admission to the cardiopulmonary unit of a long-term acute care facility using the SPICT™ [ 29 ]. In this project involving patients requiring mechanical ventilation and cardiac monitoring, 83% (59/71) of nurses working in the unit were trained in the use of the tool and screened all 50 newly admitted patients in the study period, 48 of whom were ‘SPICT™ positive’. Only 7 received a palliative care consultation within a week of admission however all 7 of these patients received a resuscitation plan and an advanced directive. Of note the use of the SPICT™ for screening resulted in a doubling of the facility’s monthly average number of palliative care referrals (from 32 to 84). In another clinical improvement project designed to increase screening and referral for palliative care among ambulatory care patients, nurse practitioners found the SPICT™ ‘. opens the door to a discussion of palliation .’ and was ‘. helpful in determining eligibility for palliative care. .’ p 22 28 . This project using both quantitative and qualitative approaches revealed an increase in palliative care referrals from 16% ( n = 8/50) to 50% ( n = 25/50) after the SPICT™ was introduced.

Two studies designed to translate and validate the SPICT-DK™ (Danish) [ 21 ] and SPICT-SE™ (Swedish) [ 24 ] involving focus groups with health care professionals revealed positive responses from doctors and nurses. The tool was described as a linguistic framework among these professionals and that use of the SPICT™ gave them a common language in which to collaborate and focus when treating and caring for patients [ 21 ]. The specificity of the tool was highlighted by nurses and medical doctors [ 24 ].

Conversely the expert committee comprising family physicians and palliative and home care specialists who provided input to the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the SPICT™ into Japanese were more circumspect [ 27 ]. These experts were concerned that the tool might not be appropriate for framing advance planning conversations as a ‘not-telling the truth’ culture was prevalent and health care was heavily siloed into specialities so that care planning was fragmented.

The SPICT™ has been used to screen for palliative care needs in many patient cohorts, settings and countries. The cohorts in which the SPICT™ has been used include people over 65 years [ 35 ], those with advanced cancer 32 36 and with chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease [ 28 ], renal disease [ 34 ] and pulmonary disease [ 29 ].

Ten of the included studies were conducted in primary care and general practice settings 20 , 21 , 22 24 25 30 , 31 , 32 37 38 . The SPICT™ was also used in outpatient clinic settings 23 28 39 and residential aged care 29 35 . One cross sectional survey of community households in India used the SPICT™ to identify patients with palliative care needs in two rural communities [ 40 ]. The SPICT™ was originally developed for use in a hospital setting but not formally validated during its development [ 2 ]. All of the contexts in which the SPICT™ has been used are listed in Table 1 .

Of the included records ten were studies conducted in European countries 20 , 21 , 22 24 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 37 38 ; seven in Asia 23 25 27 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ; three in the USA 28 29 36 ; two in Australia 34 35 ; one in South Africa [ 43 ] one in Chile [ 26 ] and one in Peru [ 44 ], and one paper was a review performed by authors based in Switzerland [ 18 ]. Of note the systematic review and survey of European primary care GP practice to identify patients for palliative care revealed that the United Kingdom was the only European country at the time that incorporated the SPICT™ to identify palliative care needs in primary and secondary care in clinical guidelines [ 31 ].

The SPICT ™ has been translated, cross culturally adapted and validated to identify patients with palliative care needs in Danish [ 21 ] and German [ 38 ] using the Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pre-testing and Documentation (TRAPD) model. Another study by Afshar, et al. [ 32 ] further established the validity of the SPICT-DE ™ in German in general practice with a patient cohort. In addition the SPICT ™ has been translated from English to Italian [SPICT-IT ™ ] [ 22 ], Spanish [SPICT-ES ™ ] [ 20 ], Swedish [ 24 ] and Japanese [SPICT-J ™ ] [ 23 ] using the Beaton protocol for cross cultural adaptation of health measures [ 45 ]. Farfán-Zuñiga and Zimmerman-Vildoso [ 26 ] established the reliability and validity of the SPICT-ES CHTM after culturally adapting the SPICT-ES ™ using the Beaton protocol. Nurses positively evaluated the feasibility of the tool. In addition Oishi et al. [ 27 ] also performed a translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the SPICT ™ into Japanese using a similar approach. The forward-back translated Indonesian version of the tool was found to be highly reliable and valid and greatly assisted in identifying hospital patients’ unmet palliative care needs [ 41 ].

The SPICT™ for low-income settings (LIS) was translated and cross culturally adapted for use in Thailand [ 25 ]. The interrater reliability of the final SPICT-LIS™ Thai version was high when nurses and GPs used it to ascertain palliative care needs of patients in case vignettes.

A Delphi study was used to develop the SPICT™ for the South African context [ 43 ]. Modifications to the original tool included the addition of haematological and infectious diseases and trauma however the SPICT-SA™ has yet to be validated in these patient cohorts. Although not a validated study per se in research comparing the performance of the Dutch version of the tool (SPICT-NL™) and the SQ in general practice ( n = 3,640) the SPICT™ was found to be superior to the SQ in identifying patients with palliative care needs particularly younger people [ 37 ].

Of note the SPICT4-ALL™ [ 46 ] is a simplified version of the original SPICT™ developed for family/friends and care staff to identify individual palliative care needs. It is available to download from the SPICT™ website in English, German, Danish and Spanish. Although Sudhakaran, et al. [ 40 ] successfully used it to identify palliative care needs in two communities in rural India. No studies validating or evaluating it were found in our search.

Does use of the SPICT ™ facilitate changes in documented goals of care?

There is evidence that the SPICT™ by virtue of assisting clinicians to discuss end of life care facilitates changes in documented goals of care. Specifically this was demonstrated in a pre-post intervention study in which GPs trained in palliative care and the use of the SPICT-DE™ were requested to use it in their everyday practice for 12 months with every adult patient diagnosed with a chronic, progressive disease [ 30 ]. This occurred concurrently with a public campaign focused on informing health care providers and stake holders in two counties in Germany about end-of-life care. GPs’ documentation improved after the intervention. Records of care planning increased from 33 to 51% and documentation of preferred place of death towards the end-of-life increased from 20 to 33% and patients’ wishes, and spiritual beliefs increased from 18 to 27%. Incidentally GPs’ self-reported quality of end-of-life care increased after the implementation of the SPICT-DE™ and the information campaign [ 30 ].

In a study including 187 residents in an aged care facility in Australia comparing the SPICT™ and SQ, two Directors of Nursing pre-screened residents using the SQ and if the response was ‘yes’ (SQ+) applied the SPICT™ [ 35 ]. Of the 80 (43%) residents who were SQ+, 100% of these showed signs of nearing end of life according to the SPICT™. Of these residents 39 (49%) had some form of palliative care from either GPs, a specialist palliative care physician or palliative care nurse. Nearly all 39 (97%) had a GP management plan, and 67% had an advance care directive and 67% had discussed treatment options with their care provider [ 29 ]. It is unclear whether the SPICT™ affected care planning or documentation as the study involved pre-screening with the SQ and documentation was not assessed before and after this intervention.

Death and dying are taboo in many countries and thus any discussion about end of life is challenging. However, clinicians are morally and ethically obliged to appropriately initiate discussions about advance care planning towards the end of life when patients are ready [ 47 ]. This review found that the SPICT™ may help the clinician with this conversation. Specifically, evidence suggests that the tool may be a useful proforma and a conversation ‘checklist’ to ensure that the priority areas for advance care planning are addressed. Specifically, the tool may enable an assessment of the person’s readiness to have an advance planning conversation and an exploration of their expectations, the diagnosis, what matters to them, treatment options and future plans [ 14 ]. Importantly extensive specialist training is not required to administer it; the studies in this review employed brief information interventions to prepare clinicians to use the SPICT™. Thus, the SPICT™ provides a method of ‘objectively’ assessing palliative care needs, articulating the requirement for a specialist palliative review if required and advance care planning.

This review found that the SPICT™ was used in mainly primary health care settings and predominately in European countries. Of note there were few published records of its use in countries in the Asian and African continents and North America. The tool has been translated into more than eight languages including Spanish (SPICT-ES™) [ 20 ], Italian (SPICT-IT™) [ 22 ], German (SPICT-DE™) [ 38 ] and Japanese (SPICT-J™) [ 23 ] although not all versions have been formally validated [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 33 ].

Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that the SPICT™ may facilitate changes in the goals of care and documentation of end of life care planning and patient wishes. Incidentally the SPICT™ appears to be positively received by clinicians with some suggesting that the tool provides a common language for clinicians when collaborating to identify palliative care needs and provide palliative care.

Of note the tool did not meet the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) criteria [ 18 ]. However arguably these criteria may not be the most appropriate criteria on which to base an assessment of the SPICT™ given that it was never meant to be used to objectively measure a parameter such as prognosis; Highet et al. [ 2 ] were clear about the remit of the tool i.e., “help clinicians working in primary and secondary care recognise when their patients might be at risk of dying and likely to benefit from supportive and palliative care in parallel with appropriate ongoing management of their advanced conditions.” [ 2 ], p11.

There is an imperative to improve recognition of palliative care needs particularly in fast paced acute care settings. Evidence suggests that a tool such as the SPICT™ is an important adjunct for initiating a conversation about end-of-life care and ensuring that key palliative care needs are identified. Importantly the SPICT™ requires little training and its brevity may be suited to settings in which there is limited opportunity to engage in lengthy conversations and in which clear unambiguous communication is key to timely referral and treatment. Formalising palliative care needs screening in an end-of-life conversation in acute care settings may reduce distress for patients and their informal care givers [ 48 ] and the SPICT™ is a relevant proforma for such a conversation. Furthermore with the increase in the numbers of people living with chronic illness globally [ 49 ] arguably the formal adoption of palliative care needs screening in all health care settings may not only reduce patient distress but may assist health care managers and policy makers to more appropriately plan services [ 50 ]. Identifying needs early in the illness trajectory may allow appropriate personalised care and services to be provided in a timely and cost effective manner thus avoiding health crises at the end of life [ 51 ].

Conversely caution should be exercised when recommending a tool to guide advance care planning and end of life conversations particularly in the setting of low health professional skill level. This was highlighted by experienced GP participants in the study by Afshar et al. [ 33 ]. The GPs did not consider that the SPICT-DE™ made any impact on their practice. A proforma or guideline cannot replace the need for exemplary health care professional communication during advance care planning and end of life conversations particularly as studies reporting the use of the SPICT™ were not specifically focused on testing its efficacy in this regard. Flexibility and sensitivity are required to assess and manage people with life limiting conditions to ensure care is individualised. Thus, a sufficiently trained and resourced workforce is vital in addition to aids such as the SPICT™.

In addition, although not the focus of this review we noticed that there was an apparent lack of attention paid to input from the family and consideration of the family context in the included studies. In practice the advance care planning conversation goes beyond using the family to identify palliative care needs and the requirement for referral. The conversation should include addressing family members’ concerns and emotions and facilitate communication between the person who is the focus of advance care planning and their family members [ 52 ].

There are translations of the English version of the SPICT™ available to download from the SPICT™ website for a number of countries including; Brazil, France, Greece, Portugal and South Africa. However, studies reporting the use of many versions of the SPICT™ indicates that formal validation has not been performed. Further validation may strengthen the efficacy and reputation of these versions of the tool. Further studies are required to establish the validity of translated versions of the SPICT™ in Swedish, Danish, Indonesian and the SPICT-LIS™ (Thai), for everyday use in other patient cohorts.

The SPICT™ has scope to be tested in other patient cohorts. Specifically more work is required to extend and test its use in acute care settings where the demand for palliative care is rising and appropriate timely referrals to specialist palliative care are vital to avoid unnecessary distress [ 51 ]. Similarly, there are research opportunities such as reliability and validity testing in relation to the SPICT-4ALL™ version which has been specifically designed to be used by family and informal carers.

Strengths and limitations

This review has strengths which warrant consideration. For example, a systematic approach based on the PRISMA-SCr methodological framework was used, and the search was extensive including 5 electronic databases and many sources of grey literature. A limitation of this review is that we were unable to access a healthcare librarian to assist with the search thus important records may have been missed. In addition, we did not have funding to arrange the translation of two studies which were identified as potentially eligible. Studies included in this scoping review were not appraised for bias thus the level of evidence for the effectiveness of the SPICT™ was not reported. Of note most studies were descriptive and thus evidence for the effectiveness in relation to review question 1 (how does the tool assist with conversations about advance care planning?) is not available.

The current scoping review aimed to assess the impact and extent of the use of the SPICT™. In summary the SPICT™ appears to enable advance care planning, review of care plans and initiation of palliative care in many settings. Previous research suggests that patients and their families greatly appreciate the opportunity to discuss end of life matters. The SPICT™ provides clinicians a proforma on which to base this conversation and a common language to collaborate for palliative care. Clinicians with advance care planning and end of life communication in all settings should consider using the SPICT™ for this purpose. Future research should focus on further validating the SPICT™ in more patient cohorts and acute care settings. Further testing of the tool beyond Europe in countries in Africa, Asia and North America is also warranted.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. In: Connor S, editor. Global atlas of Palliative Care. 2nd ed. London, UK: World Health Organisation; 2020. p. 120.

Google Scholar

Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, et al. Development and evaluation of the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Supportive Palliat Care. 2014;4(3):285–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000488 .

Article Google Scholar

Le B, Mileshkin L, Doan K, Saward D, Sruyt O, Yoong J, Gunawardana D, Conron M, Phillip J. Acceptability of early integration of palliative care in patients with incurable lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(5). https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0473 .

Perrin KO, Kazanowski M. Overcoming barriers to Palliative Care Consultation. Crit Care Nurse. 2015;35(5):44–52. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2015357 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Scholz B, Goncharov L, Emmerich N, et al. Clinicians’ accounts of communication with patients in end-of-life care contexts: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(10):1913–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.033 .

Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):224–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315606645 . [published Online First: 2015/09/26].

Heyland D, Dodek, Rocker G, Groll D, Gafni A, Pachora D, Shortt S, Tranmer J, Lazar N, Kutsogiannis A, Lam M. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):627–33.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Salins N, Ramanjulu R, Patra L, et al. Integration of early specialist palliative care in cancer care and patient related outcomes: a critical review of evidence. Indian J Palliat care. 2016;22(3). https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.185028 .

Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaneya N, Dev R, De La Cruz M, Kim SH, Kwon JH, Hutchins R, Liem C, Bruera E. Concepts and definitions for actively dying, end of life, terminally ill, terminal care, and transition of care: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 2014;47(1).

Kelly A, Morrison R. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1404684 .

Haute autorite de sante. ORGANISATION OF PATHWAYS - essentials of the palliative approach. TOOL TO IMPROVE PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE; 2016.

Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care planning for adults: a Consensus Definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(5):821–e321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 .

Boyd K, Murray S. Recognising and managing key transitions in end-of-life care. BMJ. 2010;341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4863 .

Group PPCR. The SPICT ™ Supportive and palliative care indicators tool Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Edinburgh; 2023. https://www.spict.org.uk/the-spict/ accessed 05 Feb 2024.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. In: Munn EAZ, editor. JBI Manual for evidence synthesis. Scoping reviews: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020. p. 45.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 .

IAHPC. Global Consensus based palliative care definition Houston, TX, USA: The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care. 2018. https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care/definition/ accessed 10 July 2023.

Teike Luthi F, MacDonald I, Rosselet Amoussou J, et al. Instruments for the identification of patients in need of palliative care in the hospital setting: a systematic review of measurement properties. JBI Evid Synth. 2022;20(3):761–87. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00555 .

Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, et al. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-4 .

Fachado A, Alonso, Martínez NS, Roselló MM, et al. Spanish adaptation and validation of the supportive & palliative care indicators tool – SPICT-ES™. Rev Saúde Pública. 2018;52(0):3. https://doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000398 .

Bergenholtz H, Weibull A, Raunkiaer M. Supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT) in a Danish healthcare context: translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and content validation. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00931-6 . [published Online First: 2022/03/26].

Casale G, Magnani C, Fanelli R, et al. Supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT): content validity, feasibility and pre-test of the Italian version. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00584-3 . [published Online First: 2020/06/09].

Hamano J, Oishi A, Kizawa Y. Identified Palliative Care Approach needs with SPICT in Family Practice: a preliminary observational study. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(7):992–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0491 . [published Online First: 2018/02/10].

Pham L, Arnby M, Benkel I, et al. Early integration of palliative care: translation, cross-cultural adaptation and content validity of the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool in a Swedish healthcare context. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(3):762–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12781 . [published Online First: 2019/11/02].

Sripaew S, Fumaneeshoat O, Ingviya T. Systematic adaptation of the Thai version of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool for low-income setting (SPICT-LIS). BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00729-y . [published Online First: 2021/02/21].

Farfán-Zuñiga X, Zimmermann-Vildoso M. Cultural adaptation and validation of the SPICT-ES™ instrument to identify palliative care needs in Chilean older adults. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-01111-2 . [published Online First: 2022/12/17].

Oishi A, Hamano J, Boyd K, et al. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool into Japanese: a preliminary Report. Palliat Med Rep. 2022;3(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/pmr.2021.0083 . [published Online First: 2022/09/06].

Clark NH. Palliative Care: improving Eligible Patient Identification to encourage early intervention [Capstone]. Northern Arizona University; 2019.

Dinega G. Improving palliative care utilization processes: An effort to enhance nurses’ contribution [D.N.P]. The College of St. Scholastica; 2016.

van Baal K, Wiese B, Muller-Mundt G, et al. Quality of end-of-life care in general practice - a pre-post comparison of a two-tiered intervention. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01689-9 . [published Online First: 2022/04/22].

Maas EA, Murray SA, Engels Y, et al. What tools are available to identify patients with palliative care needs in primary care: a systematic literature review and survey of European practice. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(4):444–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000527 . [published Online First: 2014/06/21].

Afshar K, Wiese B, Schneider N, et al. Systematic identification of critically ill and dying patients in primary care using the German version of the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool (SPICT-DE). Ger Med Sci. 2020;18:Doc02. https://doi.org/10.3205/000278 . [published Online First: 2020/02/13].

Afshar K, van Baal K, Wiese B, et al. Structured implementation of the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool in general practice – a prospective interventional study with follow-up. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-01107-y .

Lunardi L, Hill K, Crail S, et al. Supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool (SPICT) improves renal nurses’ confidence in recognising patients approaching end of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002496 . [published Online First: 2020/11/05].

Liyanage T, Mitchell G, Senior H. Identifying palliative care needs in residential care. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(6):524–29. doi: 10.1071/PY17168 [published Online First: 2018/11/14].

Chan AS, Rout A, ’Adamo CRD, et al. Palliative referrals in Advanced Cancer patients: utilizing the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool and Rothman Index. Am J Hospice Palliat Medicine®. 2022;39(2):164–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211017873 .

van Wijmen MPS, Schweitzer BPM, Pasman HR, et al. Identifying patients who could benefit from palliative care by making use of the general practice information system: the Surprise question versus the SPICT. Fam Pract. 2020;37(5):641–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmaa049 . [published Online First: 2020/05/20].

Afshar K, Feichtner A, Boyd K, et al. Systematic development and adjustment of the German version of the supportive and Palliative Care indicators Tool (SPICT-DE). BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0283-7 .

Fumaneeshoat O, Ingviya T, Sripaew S. Prevalence of Cancer Patients Requiring Palliative Care in Outpatient Clinics in a Tertiary Hospital in Southern Thailand. 2021 2021;39(5):11. https://doi.org/10.31584/jhsmr.2021798 [published Online First: 2021-07-02].

Sudhakaran D, Shetty RS, Mallya SD, et al. Screening for palliative care needs in the community using SPICT. Med J Armed Forces India. 2023;79(2):213–19. [published Online First: 2023/03/28].

Effendy C, Silva JFDS, Padmawati RS. Identifying palliative care needs of patients with non-communicable diseases in Indonesia using the SPICT tool: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00881-5 .

Pairojkul S, Thongkhamcharoen R, Raksasataya A, et al. Integration of specialist Palliative Care into Tertiary hospitals: a Multicenter Point Prevalence Survey from Thailand. Palliat Med Rep. 2021;2(1):272–79.

Krause R, Barnard A, Burger H, et al. A Delphi study to guide the development of a clinical indicator tool for palliative care in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2022;14(1):e1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3351 . [published Online First: 2022/06/14].

Pinedo-Torres I, Intimayta-Escalante C, Jara-Cuadros D, et al. Association between the need for palliative care and chronic diseases in patients treated in a Peruvian hospital. Revista peruana de medicina Experimental y Salud pública. 2021;38(4):569–76. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2021.384.9288 .

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 . [published Online First: 2000/12/22].

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

University of Edinburgh. SPICT-4ALL Edinburgh, Scotland, 2023. https://www.spict.org.uk/spict-4all/ accessed 04 July 2023.

Zwakman M, Jabbarian LJ, van Delden J, et al. Advance care planning: a systematic review about experiences of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness. Palliat Med. 2018;32(8):1305–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318784474 . [published Online First: 2018/06/30].

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 . [published Online First: 2008/10/09].

Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: a narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:284–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.008 . [published Online First: 2018/11/09].

Taghavi M, Johnston G, Urquhart R, et al. Workforce planning for community-based Palliative Care specialist teams using Operations Research. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2021;61(5):1012–e224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.009 .

Hui D, Heung Y, Bruera E. Timely Palliative Care: personalizing the process of Referral. Cancers. 2022;14(4):1047.

Kishino M, Ellis-Smith C, Afolabi O, et al. Family involvement in advance care planning for people living with advanced cancer: a systematic mixed-methods review. Palliat Med. 2022;36(3):462–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211068282 . [published Online First: 2022/01/07].

Download references

Acknowledgements

The work involved in performing this review was not funded.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Avondale University, Wahroonga, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Melanie Mahura

Hammond Care, Greenwich, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Brigitte Karle

Royal North Shore Hospital, St. Leonards, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Louise Sayers, Felicity Dick-Smith & Rosalind Elliott

University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Rosalind Elliott

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

We declare that this paper has not been published elsewhere and we have not submitted the paper to any other journal at the time of this submission. In addition, we Rosalind Elliott (RE), Melanie Mahura (MM), Brigitte Karle (BK), Felicity Dick-Smith (F D-S) and Louise Sayers (LS), declare that we have no known conflicts of interest in relation to the review or manuscript.All authors contributed to the research and reporting. MM lead the protocol design with input from all authors (RE, BK, FD-S and LS) and the search. MM and RE screened the search records with BK and LS acting as arbitrator. MM and BK extracted the data. Synthesis and interpretation were performed mainly by MM and BK with input from all authors. The writing was lead by MM with contributions from all authors (RE, BK, FD-S and LS). RE provided mentorship and thoroughly edited the final version. All authors (MM, RE, BK, FD-S and LS) reviewed the final version and gave their final approval for submission of the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosalind Elliott .

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication, ethical approval and consent to participate, ethical guidelines.

The International Medical Journal Editors’ Committee guidelines for authorship were followed.

Author’s information (optional)

Conflict of interest.

The authors know of no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mahura, M., Karle, B., Sayers, L. et al. Use of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT™) for end-of-life discussions: a scoping review. BMC Palliat Care 23 , 119 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01445-z

Download citation

Received : 17 August 2023

Accepted : 25 April 2024

Published : 16 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01445-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Communication

- Documentation

- Palliative Care

- Patient Care Planning

- Terminal Care

BMC Palliative Care

ISSN: 1472-684X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Welcome to LSE Theses Online, the online archive of PhD theses for the London School of Economics and Political Science. LSE Theses Online contains a partial collection of completed and examined PhD theses from doctoral candidates who have studied at LSE. Please note that not all print PhD theses have been digitised.

Departments (146) Law (146) Number of items at this level: 146. Misra, Tanmay (2023) The invention of corruption: India and the License Raj. PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science. Garcés de Marcilla Musté, Mireia (2023) Designing, fixing and mutilating the vulva: exploring the meanings of vulval cutting.

Browse by Sets. Number of items at this level: 323. Liao, Junyi (2023) Essays on macroeconomics. PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science. Matcham, William Oliver (2023) Essays in household finance and innovation. PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science. Leonardi, Edoardo (2023) Essays on heterogeneity ...

LSE Theses Online contains full text, final examined versions of theses accepted for the qualification of Doctorate at the London School of Economics and Political Science. LSE Theses Online does not contain Master's dissertations, please contact the relevant department directly if you are seeking to access a Master's dissertation. ...

Search the LSE database of research papers, articles, theses, books chapters, reports and other research material. Skip to main content. Search. Menu. In this section. Research. REF 2021; LSE Expertise: UK Economy; ... LSE is a private company limited by guarantee, registration number 70527. ...

LSE Theses Online - contains reference and many full text LSE PhD theses. Keep up to date with journal alerts. ... with database alerts. Most bibliographic and citation databases will allow you to set up regular email alerts on a given topic, keyword or author. They can be set up so that you will be informed every time new publications match ...

Learn about the Library's online resources such as ebooks, databases, news and more. Contact one of our librarians. Library services for LSE alumni. Archives catalogue for special collections. ... LSE is a private company limited by guarantee, registration number 70527. +44 (0)20 7405 7686. Campus map. Contact us. Report a page. Cookies ...

Most databases allow you to create your own account enabling you to save your searches, re-run them and set up alerts when new items are added. ... LSE LIFE Workshop - Master's Dissertation: develop and refine your search strategy for your literature review - sign up to one for practical tips for your online research . Contact us.

Most databases allow you to create your own account enabling you to save your searches, re-run them and set up alerts when new items are added. ... LSE LIFE Workshop - Master's Dissertation: develop and refine your search strategy for your literature review - sign up to one for practical tips for your online research . Contact us.

If you're thinking about conducting dissertation research that involves collecting your own data (like surveys, interviews, social media analysis), you'll want a plan for how you'll manage your data and keep it secure. ... LSE is a private company limited by guarantee, registration number 70527. +44 (0)20 7405 7686. Campus map. Contact us ...