How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

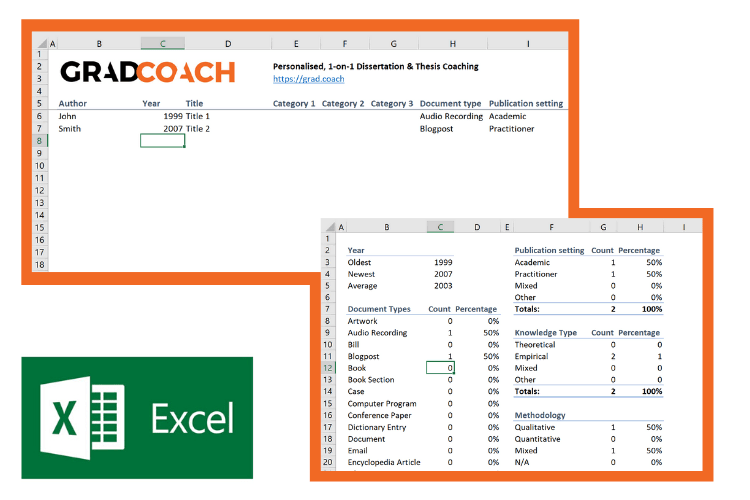

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Blog – Authenu

Anna university annexure i publications: a guide to getting published for phd.

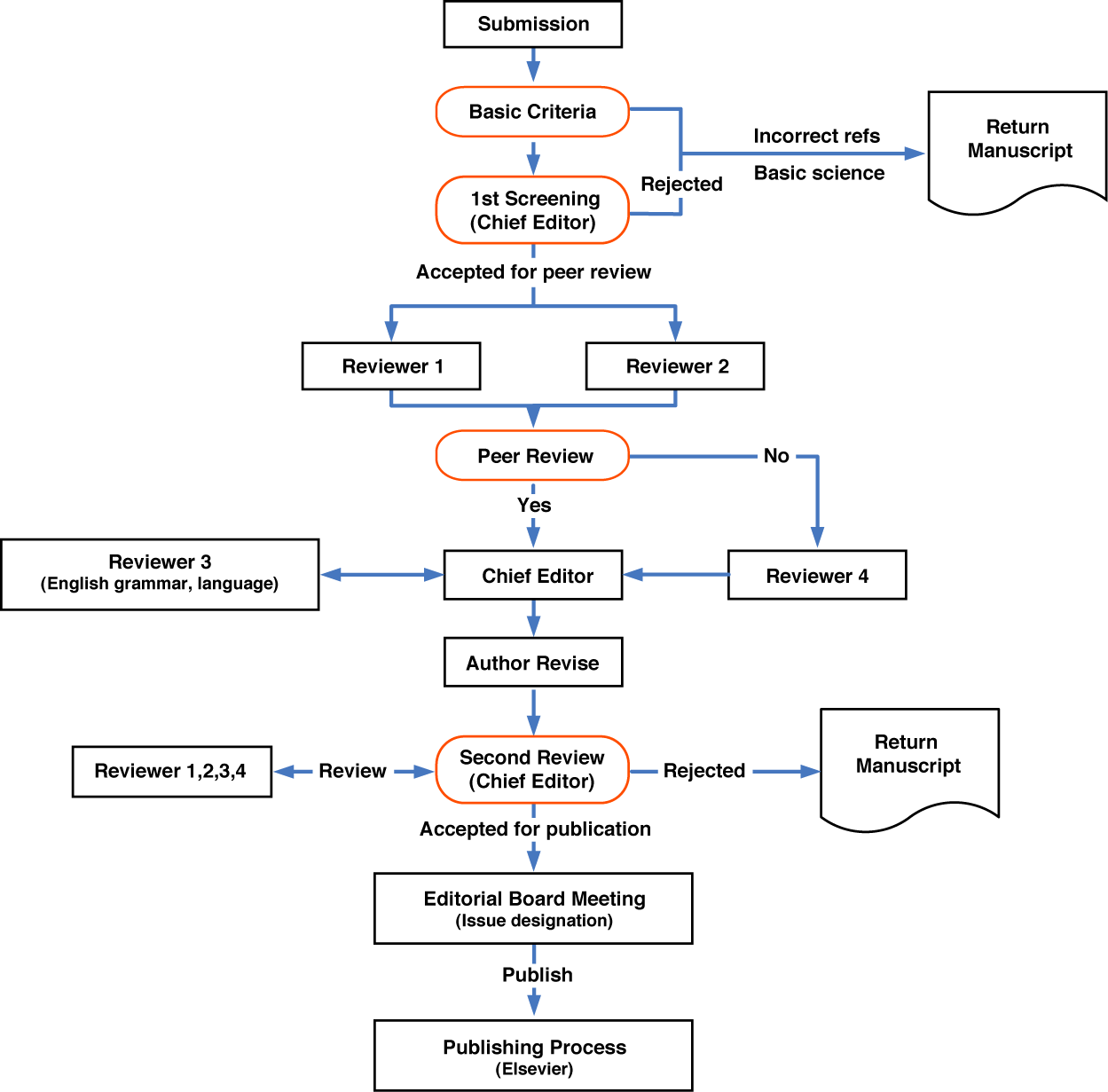

Anna University instructs its scholars to get their research publications for PhD in ISI-indexed journals. ISI is a service that offers access to quality controlled Open Access Journals. The aim of ISI is to have a more comprehensive perspective and encompass all the open access scientific and scholarly journals which are using the right kind of quality control mechanism. It does not even limit itself to any specific languages or subject domains. The reason it has been created is to enhance the visibility of good quality scholarly journals, thus increasing their readability and impact factor as well.

As a scholar, you must know that ISI follows a strict referring process and two to four referees should be there for each submitted manuscript. With the stringent acceptance policies, the acceptance rate is mostly less than 50 per cent.

Within the ISI journals , there are subcategories and levels. The highest level of ISI defines the most original and significant contribution in the field. If a scholar gets a publication in an ISI-indexed journal, it is taken to be a remarkable contribution in the field of study.

The review process for the ISI journals is quite stringent, and one needs to follow a process to select the ISI journal that is most appropriate for the researcher. The journal can be selected with this process:

- Choose field of knowledge

- Determine journals’ Impact Factor and Quartiles

- Select the journals within the quartile (Q1, Q2, Q3)

- For all journals selected, visit their website

- Check type of works accepted (Review, Original research article, Letters, etc.)

- Check the turnaround time for articles submitted to the journal

- Check number of publications per year

- Check type of fees associated

- Check whether it has online edition

- Check the length and structure of the manuscript acceptable to the journal

Here is a flow chart of how the Review Process the journals at ISI normally follow:

You must have the following considerations in place before you think your research paper is complete to be sent at ISI:

- First of all give an honest opinion to yourself that your research is worth publishing

- Answer whether my research has substantive contribution to make in the field of study or the literature under study?

- What are the steps needed to be cleared before the submission in the chosen journal?

- How can I increase the citations of my published research by selecting the most appropriate journal?

Other than knowing the guidelines for getting your paper selected for publication in one of these worthy journals, you must also know the reasons because of which your paper may get rejected by the journal for a more thorough preparation. But once you get prepared with your manuscript, your quest for the most suitable ISI journal begins. We can make your this quest easy and can help you figure out that one perfect ISI journal, write to us at [email protected]

One thought on “ Anna University Annexure I publications: A guide to getting published for PhD ”

But why is there no mention of Anna University?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Med Educ

- v.7(1); 2018 Feb

Writing an effective literature review

Lorelei lingard.

Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Health Sciences Addition, Western University, London, Ontario Canada

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

This Writer’s Craft instalment is the first in a two-part series that offers strategies for effectively presenting the literature review section of a research manuscript. This piece alerts writers to the importance of not only summarizing what is known but also identifying precisely what is not, in order to explicitly signal the relevance of their research. In this instalment, I will introduce readers to the mapping the gap metaphor, the knowledge claims heuristic, and the need to characterize the gap.

Mapping the gap

The purpose of the literature review section of a manuscript is not to report what is known about your topic. The purpose is to identify what remains unknown— what academic writing scholar Janet Giltrow has called the ‘knowledge deficit’ — thus establishing the need for your research study [ 1 ]. In an earlier Writer’s Craft instalment, the Problem-Gap-Hook heuristic was introduced as a way of opening your paper with a clear statement of the problem that your work grapples with, the gap in our current knowledge about that problem, and the reason the gap matters [ 2 ]. This article explains how to use the literature review section of your paper to build and characterize the Gap claim in your Problem-Gap-Hook. The metaphor of ‘mapping the gap’ is a way of thinking about how to select and arrange your review of the existing literature so that readers can recognize why your research needed to be done, and why its results constitute a meaningful advance on what was already known about the topic.

Many writers have learned that the literature review should describe what is known. The trouble with this approach is that it can produce a laundry list of facts-in-the-world that does not persuade the reader that the current study is a necessary next step. Instead, think of your literature review as painting in a map of your research domain: as you review existing knowledge, you are painting in sections of the map, but your goal is not to end with the whole map fully painted. That would mean there is nothing more we need to know about the topic, and that leaves no room for your research. What you want to end up with is a map in which painted sections surround and emphasize a white space, a gap in what is known that matters. Conceptualizing your literature review this way helps to ensure that it achieves its dual goal: of presenting what is known and pointing out what is not—the latter of these goals is necessary for your literature review to establish the necessity and importance of the research you are about to describe in the methods section which will immediately follow the literature review.

To a novice researcher or graduate student, this may seem counterintuitive. Hopefully you have invested significant time in reading the existing literature, and you are understandably keen to demonstrate that you’ve read everything ever published about your topic! Be careful, though, not to use the literature review section to regurgitate all of your reading in manuscript form. For one thing, it creates a laundry list of facts that makes for horrible reading. But there are three other reasons for avoiding this approach. First, you don’t have the space. In published medical education research papers, the literature review is quite short, ranging from a few paragraphs to a few pages, so you can’t summarize everything you’ve read. Second, you’re preaching to the converted. If you approach your paper as a contribution to an ongoing scholarly conversation,[ 2 ] then your literature review should summarize just the aspects of that conversation that are required to situate your conversational turn as informed and relevant. Third, the key to relevance is to point to a gap in what is known. To do so, you summarize what is known for the express purpose of identifying what is not known . Seen this way, the literature review should exert a gravitational pull on the reader, leading them inexorably to the white space on the map of knowledge you’ve painted for them. That white space is the space that your research fills.

Knowledge claims

To help writers move beyond the laundry list, the notion of ‘knowledge claims’ can be useful. A knowledge claim is a way of presenting the growing understanding of the community of researchers who have been exploring your topic. These are not disembodied facts, but rather incremental insights that some in the field may agree with and some may not, depending on their different methodological and disciplinary approaches to the topic. Treating the literature review as a story of the knowledge claims being made by researchers in the field can help writers with one of the most sophisticated aspects of a literature review—locating the knowledge being reviewed. Where does it come from? What is debated? How do different methodologies influence the knowledge being accumulated? And so on.

Consider this example of the knowledge claims (KC), Gap and Hook for the literature review section of a research paper on distributed healthcare teamwork:

KC: We know that poor team communication can cause errors. KC: And we know that team training can be effective in improving team communication. KC: This knowledge has prompted a push to incorporate teamwork training principles into health professions education curricula. KC: However, most of what we know about team training research has come from research with co-located teams—i. e., teams whose members work together in time and space. Gap: Little is known about how teamwork training principles would apply in distributed teams, whose members work asynchronously and are spread across different locations. Hook: Given that much healthcare teamwork is distributed rather than co-located, our curricula will be severely lacking until we create refined teamwork training principles that reflect distributed as well as co-located work contexts.

The ‘We know that …’ structure illustrated in this example is a template for helping you draft and organize. In your final version, your knowledge claims will be expressed with more sophistication. For instance, ‘We know that poor team communication can cause errors’ will become something like ‘Over a decade of patient safety research has demonstrated that poor team communication is the dominant cause of medical errors.’ This simple template of knowledge claims, though, provides an outline for the paragraphs in your literature review, each of which will provide detailed evidence to illustrate a knowledge claim. Using this approach, the order of the paragraphs in the literature review is strategic and persuasive, leading the reader to the gap claim that positions the relevance of the current study. To expand your vocabulary for creating such knowledge claims, linking them logically and positioning yourself amid them, I highly recommend Graff and Birkenstein’s little handbook of ‘templates’ [ 3 ].

As you organize your knowledge claims, you will also want to consider whether you are trying to map the gap in a well-studied field, or a relatively understudied one. The rhetorical challenge is different in each case. In a well-studied field, like professionalism in medical education, you must make a strong, explicit case for the existence of a gap. Readers may come to your paper tired of hearing about this topic and tempted to think we can’t possibly need more knowledge about it. Listing the knowledge claims can help you organize them most effectively and determine which pieces of knowledge may be unnecessary to map the white space your research attempts to fill. This does not mean that you leave out relevant information: your literature review must still be accurate. But, since you will not be able to include everything, selecting carefully among the possible knowledge claims is essential to producing a coherent, well-argued literature review.

Characterizing the gap

Once you’ve identified the gap, your literature review must characterize it. What kind of gap have you found? There are many ways to characterize a gap, but some of the more common include:

- a pure knowledge deficit—‘no one has looked at the relationship between longitudinal integrated clerkships and medical student abuse’

- a shortcoming in the scholarship, often due to philosophical or methodological tendencies and oversights—‘scholars have interpreted x from a cognitivist perspective, but ignored the humanist perspective’ or ‘to date, we have surveyed the frequency of medical errors committed by residents, but we have not explored their subjective experience of such errors’

- a controversy—‘scholars disagree on the definition of professionalism in medicine …’

- a pervasive and unproven assumption—‘the theme of technological heroism—technology will solve what ails teamwork—is ubiquitous in the literature, but what is that belief based on?’

To characterize the kind of gap, you need to know the literature thoroughly. That means more than understanding each paper individually; you also need to be placing each paper in relation to others. This may require changing your note-taking technique while you’re reading; take notes on what each paper contributes to knowledge, but also on how it relates to other papers you’ve read, and what it suggests about the kind of gap that is emerging.

In summary, think of your literature review as mapping the gap rather than simply summarizing the known. And pay attention to characterizing the kind of gap you’ve mapped. This strategy can help to make your literature review into a compelling argument rather than a list of facts. It can remind you of the danger of describing so fully what is known that the reader is left with the sense that there is no pressing need to know more. And it can help you to establish a coherence between the kind of gap you’ve identified and the study methodology you will use to fill it.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mark Goldszmidt for his feedback on an early version of this manuscript.

PhD, is director of the Centre for Education Research & Innovation at Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, and professor for the Department of Medicine at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window

Sample Lit Reviews from Communication Arts

Have an exemplary literature review.

Note: These are sample literature reviews from a class that were given to us by an instructor when APA 6th edition was still in effect. These were excellent papers from her class, but it does not mean they are perfect or contain no errors. Thanks to the students who let us post!

- Literature Review Sample 1

- Literature Review Sample 2

- Literature Review Sample 3

Have you written a stellar literature review you care to share for teaching purposes?

Are you an instructor who has received an exemplary literature review and have permission from the student to post?

Please contact Britt McGowan at [email protected] for inclusion in this guide. All disciplines welcome and encouraged.

- << Previous: MLA Style

- Next: Get Help! >>

- Last Updated: Sep 11, 2024 1:37 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/litreview

Internationalization at home in higher education: a systematic review of teaching and learning practices

Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education

ISSN : 2050-7003

Article publication date: 30 September 2024

This paper explores current teaching and learning practices, benefits and challenges in the implementation of Internationalization at Home (IaH) in higher education.

Design/methodology/approach

The study follows a systematic review (SR) protocol in accordance with the PRISMA Statement, covering published research from 2018 to 2022. Through this process, we identified 58 peer-reviewed manuscripts meeting our inclusion criteria. We examined disciplines, locations of IaH, objectives pursued, modality of the IaH implementation, activities and resources used. Benefits and challenges were also analysed.

The SR reveals a growing adoption of IaH, employing various technologies and interdisciplinary methods to foster cross-cultural competence. It emphasizes diverse teaching activities and resources, aligning with digitalization trends. While IaH brings benefits like improved intercultural sensitivity, collaboration and skills development, it also faces challenges in language, technical, personal, pedagogical and organizational aspects, highlighting its complexity.

Research limitations/implications

Our search focused on research from 2018 to 2022, potentially missing earlier trends, and excluded grey literature due to quality concerns. The SR emphasizes online collaborative efforts in IaH, signalling a shift to digital internationalization. Institutions should invest in supporting such practices aided by strategic university alliances. A critical approach to “Global-North” collaborations is urged, promoting geographically inclusive IaH initiatives.

Originality/value

This study responds to the call for critical analysis on concrete examples of IaH. Through a systematic review, it explores recent teaching and learning practices, with a particular focus on the latest technological advancements. The study specifies learning objectives and identifies relevant tools for implementing IaH initiatives.

- Internationalization at home

- Virtual exchange

- Internationalization of the curriculum

- Teaching and learning practices

- Transnational collaboration in higher education

Soulé, M.V. , Parmaxi, A. and Nicolaou, A. (2024), "Internationalization at home in higher education: a systematic review of teaching and learning practices", Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education , Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-10-2023-0484

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2024, María Victoria Soulé, Antigoni Parmaxi and Anna Nicolaou

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

What is the current status of IaH in HE in terms of teaching and learning practices (fields of study, locations of IaH, objectives pursued,)?

How is IaH implemented in HE (mode and duration, participants, activities and resources used)?

What are the reported benefits and challenges of IaH in HE?

2. Literature review

Internationalization at Home is a concept that was proposed in Malmö in 1998 by Bengt Nilsson in an effort to “embrace all ideas about and measures to be taken to give all students an international dimension during their time at the university” ( Nilsson, 2003 , p. 31). In his work Internationalisation at Home From a Swedish Perspective: The Case of Malmö , Nilsson defines IaH as “any internationally related activity with the exception of outbound student mobility” (2003, p. 31). This echoes the definition of IaH by Crowther et al. (2001 , p. 8) as “any internationally related activity with the exception of outbound student and staff mobility”. Both definitions are very similar and seem to embrace the notions of equity and access ( Almeida et al ., 2019 ) as IaH efforts aim at being inclusive, keeping in mind the non-mobile majority of the student body. Since IaH was developed as a concept, institutions around the world have embraced it as a means to promote global competence among a broader spectrum of students. Research highlights the benefits of IaH in fostering diverse skills, such as the development of soft skills and increased motivation of students ( Barbosa et al ., 2020 ) while enhancing the acquisition of new knowledge and developing students’ linguocultural awareness ( Karimova et al ., 2023 ).

Universities have adopted various learning practices, including the internationalization of both the formal and informal curriculum, with the goal of fostering a global mindset and intercultural understanding among students ( Leask, 2015 ). These practices involve open access education, intercultural research projects, extracurricular activities, relationships and collaborations with domestic students and ethnic or minority community groups, and the integration of foreign students and academics into campus activities ( Knight, 2012 ; Hofmeyr, 2021 ). Other IaH activities include cross-cultural peer-mentoring ( Huanga et al ., 2022 ), delivering courses in foreign languages ( Hénard et al ., 2012 ), or adopting internationalized pedagogies ( Lomer and Anthony-Okeke, 2019 ). Barbosa et al . (2020) posit that IaH encompasses various modalities, including in-campus cultural diversity, specifically multicultural classrooms with a high number of international students, and Virtual Exchange (VE) also known as “Telecollaboration, Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), etandem, online intercultural exchange” ( O’Dowd, 2023 , p. 21).

Previous reviews focusing on IaH practices have underscored persistent challenges, including limited educational resources, financial support, and proficiency in foreign languages ( Li and Xue, 2022 ). Similarly, Harrison’s (2015) review, which concentrates on IaH practices such as diversity as a resource, internationalized curriculum, and culturally sensitive pedagogy, reveals challenges in their implementation. Mainly, home students often resist intercultural group work and avoid contact with international peers, raising concerns about unequal access to transformative experiences. More recently, Janebová and Johnstone’s (2022) critical review advocates for inclusive IaH practices that create accessible educational spaces for all stakeholders. While the review emphasizes the importance of these practices, it provides limited details on implementation and specific necessary resources. Another recent review was conducted by Mittelmeier et al . (2024) , who focused on holistic internationalization, inclusion, active and creative learning, opportunities for reflection, and scaffolding intercultural skills. In their scoping review, they investigate how internationalization, including IaH, impacts student outcomes and experiences, which is crucial for designing effective internationalized learning. Despite its idealization as beneficial, the authors suggest that empirical evidence for internationalization’s benefits remains limited.

The European Association of International Education (EAIE) Barometer underscores the complexity of internationalization strategies across institutions, suggesting that “the literature on internationalisation often argues that no one model can apply to all institutions when it comes to the development and delivery of internationalisation policy and its related activities” ( Sandström and Hudson, 2019 , p. 23). However, the analysis of the EAIE Barometer data suggests possible commonalities in approaches to IaH. Moreover, it raises concerns about the dominance of scholars, especially those from Western Europe, in shaping the discourse on international education in Europe. A response to this call can be found in Wimpenny et al .’s (2021) effort to delineate a decolonized, internationalized, inclusive curriculum whose teaching and learning practices should also be determined by the context and by local perspectives, including interaction with other perspectives, such as the Global South. Howes (2018) offers a concrete example of decolonizing or 'southernizing' curriculum through a study on the internationalization of the criminology curriculum. This study draws on southern criminology as an emerging paradigm, providing guidance for this transformative process. Another example of developing IaH approaches in the Global South is the study by Finardi and Aşık (2024) that explored the potential of a virtual exchange between a university in Brazil and a university in Turkey towards engaging the two universities in international conversations.

One of the main goals of IaH is to provide all students the possibility to access cross-cultural and international education without leaving their home countries ( Li and Xue, 2022 ). The advancement of technology, particularly in the last 2 decades, has facilitated this goal. However, there have been no substantial developments in line with the recommendations made by Eisenchlas and Trevaskes (2003 , p. 89). The authors stressed the need for critical analysis of IaH, examining both theoretical aspects and concrete examples of curriculum internationalization implementation, including specifying learning aims and suggesting relevant learning tools. An exception to this lack of comprehensive frameworks can be identified in the practical models proposed by Agnew and Kahn (2014) for the pursuit of IaH and Internationalization of the Curriculum (IoC). The authors present clear examples of global course goals, global authentic assessment, global learning outcomes, classroom activities, and resources. Despite the comprehensive nature of Agnew and Kahn’s (2014) practical model, a decade has elapsed since its publication, indicating a need for updated research, particularly regarding recent advancements in IaH with technological integration.

The methodology of this review was conducted following the PRISMA statement ( Moher et al ., 2009 ). The decision to utilize the PRISMA methodology was based on its recognized rigour and structured approach for conducting systematic reviews, ensuring comprehensive and unbiased synthesis of available evidence: “many studies have evaluated how well systematic reviews adhere to the PRISMA Statement” ( Page and Moher, 2017 , p. 10). We chose this particular methodology over others due to its established guidelines, transparency, and reproducibility, which align with the objectives and scope of our research. The methodology was also informed by the processes recommended by Xiao and Watson (2019) , and by previous systematic reviews such as Caniglia et al . (2017) who reviewed transnational collaboration for sustainability in higher education.

3.1 Identification of data sources and search strategy

Internationalization at home-related keywords (“Internationalization/Internationalisation at home” OR “Internationalized/Internationalised curriculum” OR “comprehensive internationalization/internationalisation” OR “collaborative online international learning” OR “telecollaboration” OR “Virtual exchange”).

Higher education-related keywords (“higher education” OR “university” OR “college” OR “tertiary education”).

The results obtained for each database and journal are presented in Table A1 (All the tables of this study are available at Appendix 1 ).

3.2 Search results

The initial search yielded 550 manuscripts published between 2018 and 2022 that were related to IaH and HE, 441 manuscripts were identified from three databases used in this study, and 109 manuscripts from the search in the four high impact journals. Duplicate manuscripts were excluded resulting in 505 records. Figure 1 describes the flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review conducted in this study.

3.3 Application of inclusion and exclusion criteria for refining the IaH dataset

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table A2 . These criteria were applied during the screening phase of the review, as indicated in Figure 1 . During this stage, we conducted a detailed examination of articles based on their abstracts. The primary purpose of this early screening was to eliminate articles that did not align with the research questions and the established criteria. Subsequently, we performed a more comprehensive review of the full text, following the methodology outlined by Xiao and Watson (2019) . During this stage, some articles were also assessed for methodological quality, data analysis, results, and conclusions, as depicted in the 'Eligibility phase' (see Figure 1 ).

3.4 Screening and extraction of data