REVIEW article

The state of music therapy studies in the past 20 years: a bibliometric analysis.

- 1 School of Kinesiology, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China

- 2 Department of Sport Rehabilitation, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China

- 3 Department of Sport Rehabilitation Medicine, Shanghai Shangti Orthopedic Hospital, Shanghai, China

Purpose: Music therapy is increasingly being used to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals. However, publications on the global trends of music therapy using bibliometric analysis are rare. The study aimed to use the CiteSpace software to provide global scientific research about music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

Methods: Publications between 2000 and 2019 related to music therapy were searched from the Web of Science (WoS) database. The CiteSpace V software was used to perform co-citation analysis about authors, and visualize the collaborations between countries or regions into a network map. Linear regression was applied to analyze the overall publication trend.

Results: In this study, a total of 1,004 studies met the inclusion criteria. These works were written by 2,531 authors from 1,219 institutions. The results revealed that music therapy publications had significant growth over time because the linear regression results revealed that the percentages had a notable increase from 2000 to 2019 ( t = 14.621, P < 0.001). The United States had the largest number of published studies (362 publications), along with the following outputs: citations on WoS (5,752), citations per study (15.89), and a high H-index value (37). The three keywords “efficacy,” “health,” and “older adults,” emphasized the research trends in terms of the strongest citation bursts.

Conclusions: The overall trend in music therapy is positive. The findings provide useful information for music therapy researchers to identify new directions related to collaborators, popular issues, and research frontiers. The development prospects of music therapy could be expected, and future scholars could pay attention to the clinical significance of music therapy to improve the quality of life of people.

Introduction

Music therapy is defined as the evidence-based use of music interventions to achieve the goals of clients with the help of music therapists who have completed a music therapy program ( Association, 2018 ). In the United States, music therapists must complete 1,200 h of clinical training and pass the certification exam by the Certification Board for Music Therapists ( Devlin et al., 2019 ). Music therapists use evidence-based music interventions to address the mental, physical, or emotional needs of an individual ( Gooding and Langston, 2019 ). Also, music therapy is used as a solo standard treatment, as well as co-treatment with other disciplines, to address the needs in cognition, language, social integration, and psychological health and family support of an individual ( Bronson et al., 2018 ). Additionally, music therapy has been used to improve various diseases in different research areas, such as rehabilitation, public health, clinical care, and psychology ( Devlin et al., 2019 ). With neurorehabilitation, music therapy has been applied to increase motor activities in people with Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders ( Bernatzky et al., 2004 ; Devlin et al., 2019 ). However, limited reviews about music therapy have utilized universal data and conducted massive retrospective studies using bibliometric techniques. Thus, this study demonstrates music therapy with a broad view and an in-depth analysis of the knowledge structure using bibliometric analysis of articles and publications.

Bibliometrics turns the major quantitative analytical tool that is used in conducting in-depth analyses of publications ( Durieux and Gevenois, 2010 ; Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ). There are three types of bibliometric indices: (a) the quantity index is used to determine the number of relevant publications, (b) the quality index is employed to explore the characteristics of a scientific topic in terms of citations, and (c) the structural index is used to show the relationships among publications ( Durieux and Gevenois, 2010 ; Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ). In this study, the three types of bibliometric indices will be applied to conduct an in-depth analysis of publications in this frontier.

While research about music therapy is extensively available worldwide, relatively limited studies use bibliometric methods to analyze the global research about this topic. The aim of this study is to use the CiteSpace software to perform a bibliometric analysis of music therapy research from 2000 to 2019. CiteSpace V is visual analytic software, which is often utilized to perform bibliometric analyses ( Falagas et al., 2008 ; Ellegaard and Wallin, 2015 ). It is also a tool applied to detect trends in global scientific research. In this study, the global music therapy research includes publication outputs, distribution and collaborations between authors/countries or regions/institutions, intense issues, hot articles, common keywords, productive authors, and connections among such authors in the field. This study also provides helpful information for researchers in their endeavor to identify gaps in the existing literature.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy.

The data used in this study were obtained from WoS, the most trusted international citation database in the world. This database, which is run by Thomson & Reuters Corporation ( Falagas et al., 2008 ; Durieux and Gevenois, 2010 ; Chen C. et al., 2012 ; Ellegaard and Wallin, 2015 ; Miao et al., 2017 ; Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ), provides high-quality journals and detailed information about publications worldwide. In this study, publications were searched from the WoS Core Collection database, which included eight indices ( Gonzalez-Serrano et al., 2020 ). This study searched the publications from two indices, namely, the Science Citation Index Expanded and the Social Sciences Citation Index. As the most updated publications about music therapy were published in the 21st century, publications from 2000 to 2019 were chosen for this study. We performed data acquisition on July 26, 2020 using the following search terms: title = (“music therapy”) and time span = 2000–2019.

Inclusion Criteria

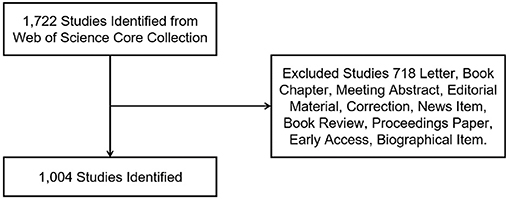

Figure 1 presents the inclusion criteria. The title field was music therapy (TI = music therapy), and only reviews and articles were chosen as document types in the advanced search. Other document types, such as letters, editorial materials, and book reviews, were excluded. Furthermore, there were no species limitations set. This advanced search process returned 718 articles. In the end, a total of 1,004 publications were obtained and were analyzed to obtain comprehensive perspectives on the data.

Figure 1 . Flow chart of music therapy articles and reviews inclusion.

Data Extraction

Author Lin-Man Weng extracted the publications and applied the EndNote software and Microsoft Excel 2016 to conduct analysis on the downloaded publications from the WoS database. Additionally, we extracted and recorded some information of the publications, such as citation frequency, institutions, authors' countries or regions, and journals as bibliometric indicators. The H-index is utilized as a measurement of the citation frequency of the studies for academic journals or researchers ( Wang et al., 2019 ).

Analysis Methods

The objective of bibliometrics can be described as the performance of studies that contributes to advancing the knowledge domain through inferences and explanations of relevant analyses ( Castanha and Grácio, 2014 ; Merigó et al., 2019 ; Mulet-Forteza et al., 2021 ). CiteSpace V is a bibliometric software that generates information for better visualization of data. In this study, the CiteSpace V software was used to visualize six science maps about music therapy research from 2000 to 2019: the network of author co-citation, collaboration network among countries and regions, relationship of institutions interested in the field, network map of co-citation journals, network map of co-cited references, and the map (timeline view) of references with co-citation on top music therapy research. As noted, a co-citation is produced when two publications receive a citation from the same third study ( Small, 1973 ; Merigó et al., 2019 ).

In addition, a science map typically features a set of points and lines to present collaborations among publications ( Chen, 2006 ). A point is used to represent a country or region, author, institution, journal, reference, or keyword, whereas a line represents connections among them ( Zheng and Wang, 2019 ), with stronger connections indicated by wider lines. Furthermore, the science map includes nodes, which represent the citation frequencies of certain themes. A burst node in the form of a red circle in the center indicates the number of co-occurrence or citation that increases over time. A purple node represents centrality, which indicates the significant knowledge presented by the data ( Chen, 2006 ; Chen H. et al., 2012 ; Zheng and Wang, 2019 ). The science map represents the keywords and references with citation bursts. Occurrence bursts represent the frequency of a theme ( Chen, 2006 ), whereas citation bursts represent the frequency of the reference. The citation bursts of keywords and references explore the trends and indicate whether the relevant authors have gained considerable attention in the field ( Chen, 2006 ). Through this kind of map, scholars can better understand emerging trends and grasp the hot topics by burst detection analysis ( Liang et al., 2017 ; Miao et al., 2017 ).

Publication Outputs and Time Trends

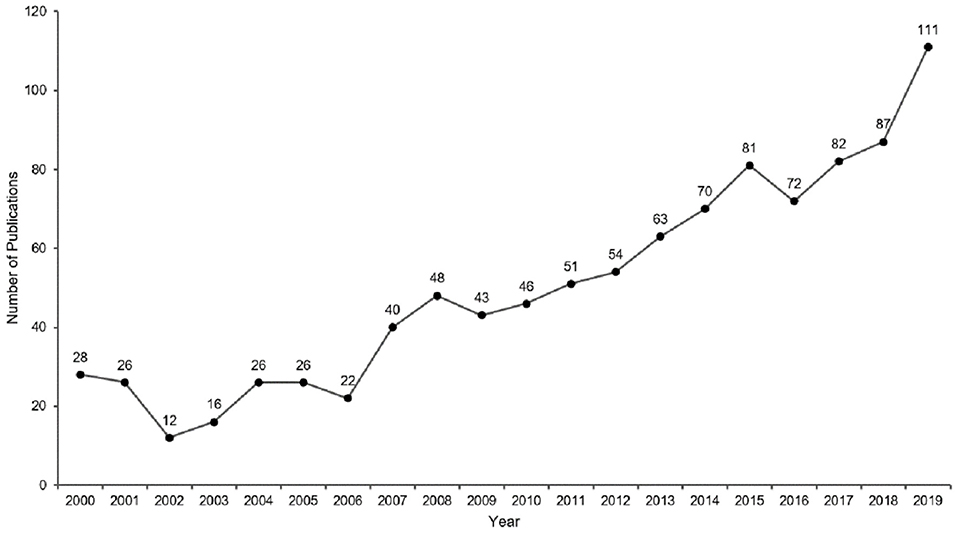

A total of 1,004 articles and reviews related to music therapy research met the criteria. The details of annual publications are presented in Figure 2 . As can be seen, there were <30 annual publications between 2000 and 2006. The number of publications increased steadily between 2007 and 2015. It was 2015, which marked the first time over 80 articles or reviews were published. The significant increase in publications between 2018 and 2019 indicated that a growing number of researchers became interested in this field. Linear regression can be used to analyze the trends in publication outputs. In this study, the linear regression results revealed that the percentages had a notable increase from 2000 to 2019 ( t = 14.621, P < 0.001). Moreover, the P < 0.05, indicating statistical significance. Overall, the publication outputs increased from 2000 to 2019.

Figure 2 . Annual publication outputs of music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

Distribution by Country or Region and Institution

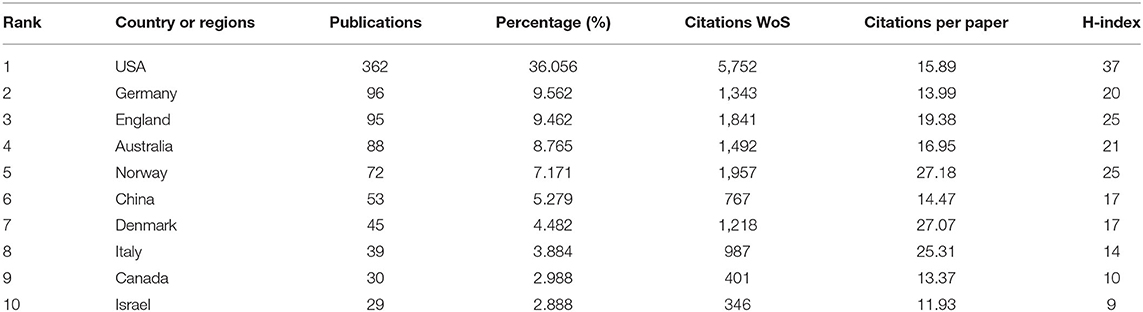

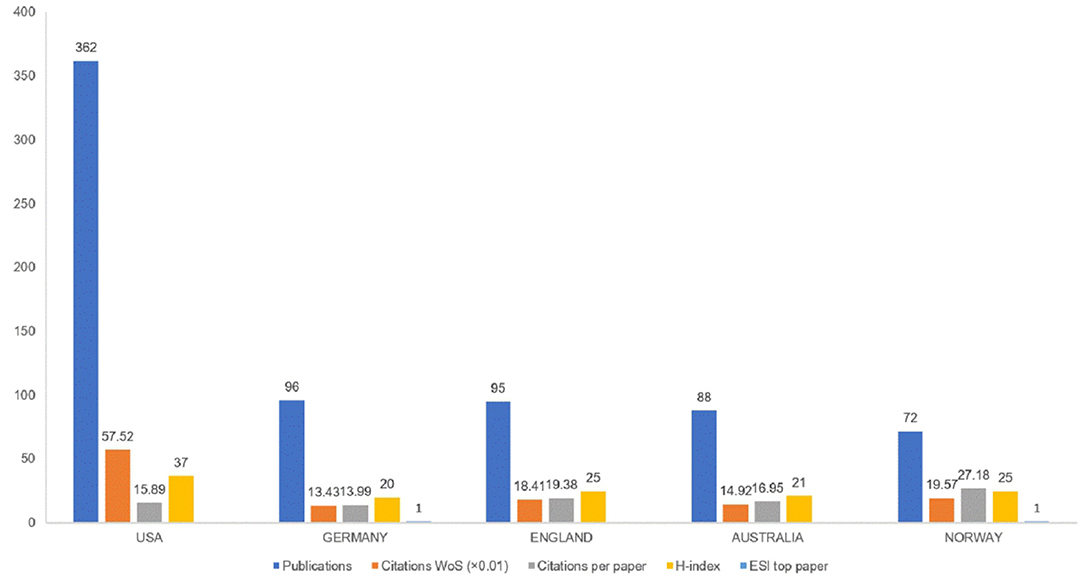

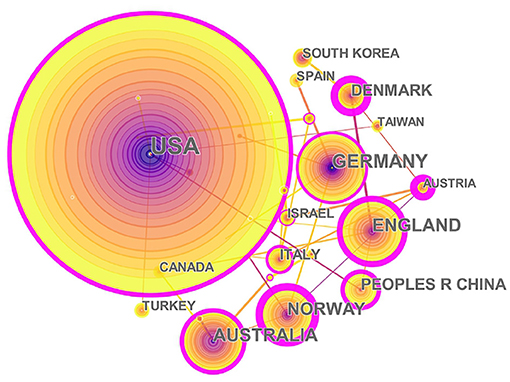

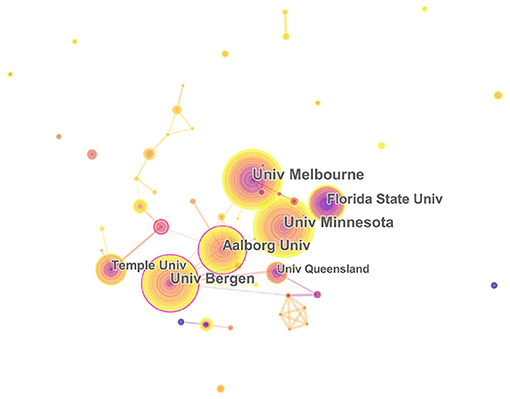

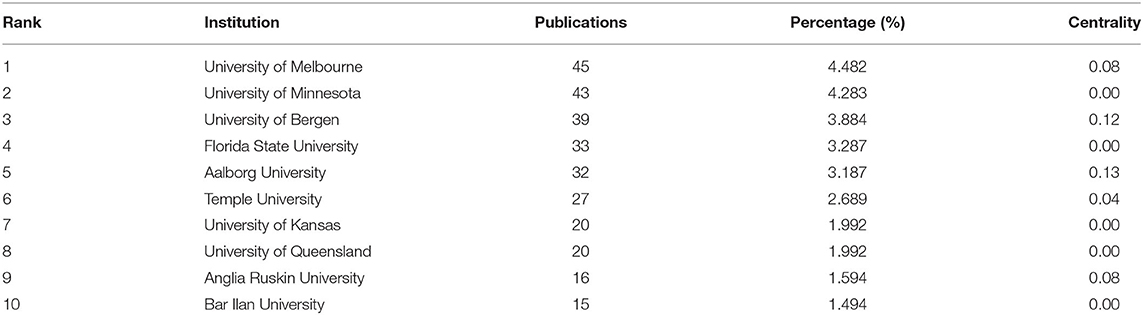

The 1,004 articles and reviews collected were published in 49 countries and regions. Table 1 presents the top 10 countries or regions. Figure 3 shows an intuitive comparison of the citations on WoS, citations per study, Hirsch index (H-index), and major essential science indicator (ESI) studies of the top five countries or regions. The H-index is a kind of index that is applied in measuring the wide impact of the scientific achievements of authors. The United States had the largest number of published studies (362 publications), along with the following outputs: citations on WoS (5,752), citations per study (15.89), and a high H-index value (37). Norway has the largest number of citations per study (27.18 citations). Figure 4 presents the collaboration networks among countries or regions. The collaboration network map contained 32 nodes and 38 links. The largest node can be found in the United States, which meant that the United States had the largest number of publications in the field. Meanwhile, the deepest purple circle was located in Austria, which meant that Austria is the country with the most number of collaborations with other countries or regions in this research field. A total of 1,219 institutions contributed various music therapy-related publications. Figure 5 presents the collaborations among institutions. As can be seen, the University of Melbourne is the most productive institution in terms of the number of publications (45), followed by the University of Minnesota (43), and the University of Bergen (39). The top 10 institutions featured in Table 2 contributed 28.884% of the total articles and reviews published. Among these, Aalborg University had the largest centrality (0.13). The top 10 productive institutions with details are shown in Table 2 .

Table 1 . Top 10 countries or regions of origin of study in the music therapy research field.

Figure 3 . Publications, citations on WoS (×0.01), citations per study, H-index, and ESL top study among top five countries or regions.

Figure 4 . The collaborations of countries or regions interested in the field. In this map, the node represents a country, and the link represents the cooperation relationship between two countries. A larger node represents more publications in the country. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

Figure 5 . The relationship of institutions interested in the field. University of Melbourne, Florida State University, University of Minnesota, Aalborg University, Temple University, University of Queensland, and University of Bergen. In this map, the node represents an institution, and the link represents the cooperation relationship between two institutions. A larger node represents more publications in the institution. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

Table 2 . Top 10 institutions that contributed to publications in the music therapy field.

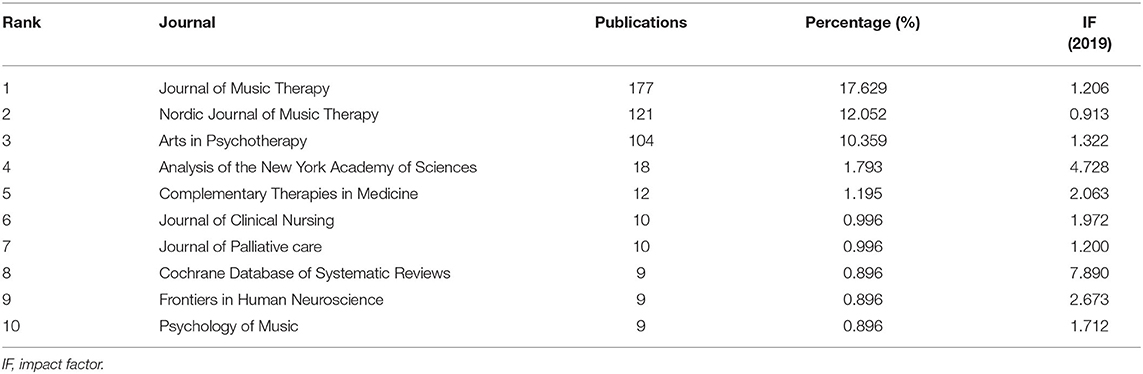

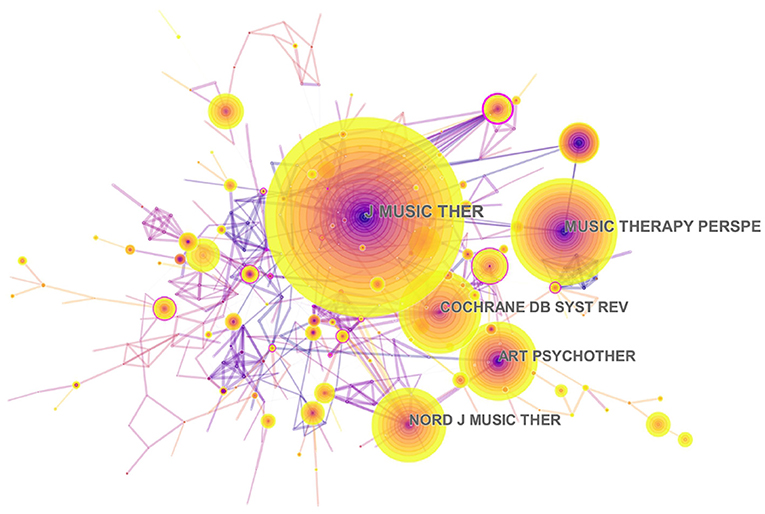

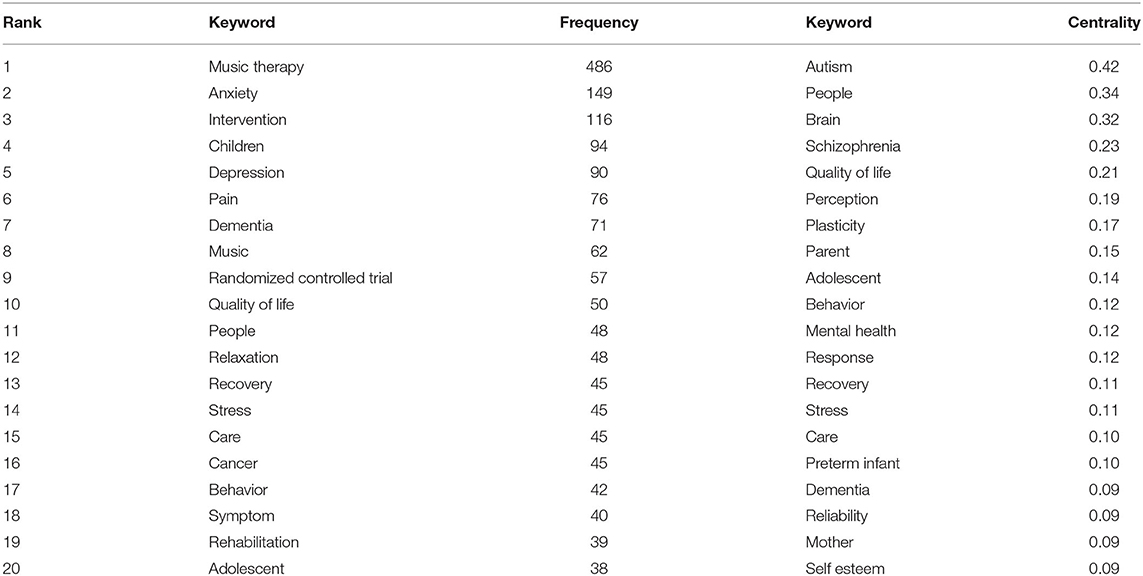

Distribution by Journals

Table 3 presents the top 10 journals that published articles or reviews in the music therapy field. The publications are mostly published in these journal fields, such as Therapy, Medical, Psychology, Neuroscience, Health and Clinical Care. The impact factors (IF) of these journals ranged between 0.913 and 7.89 (average IF: 2.568). Four journals had an impact factor >2, of which Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews had the highest IF, 2019 = 7.89. In addition, the Journal of Music Therapy (IF: 2019 = 1.206) published 177 articles or reviews (17.629%) about music therapy in the past two decades, followed by the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy (121 publications, 12.052%, IF: 2019 = 0.913), and Arts in Psychotherapy (104 publications, 10.359%, IF: 2019 = 1.322). Furthermore, the map of the co-citation journal contained 393 nodes and 759 links ( Figure 6 ). The high co-citation count identifies the journals with the greatest academic influence and key positions in the field. The Journal of Music Therapy had the maximum co-citation counts (658), followed by Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (281), and Arts in Psychotherapy (279). Therefore, according to the analysis of the publications and co-citation counts, the Journal of Music Therapy and Arts in Psychotherapy occupied key positions in this research field.

Table 3 . Top 10 journals that published articles in the music therapy field.

Figure 6 . Network map of co-citation journals engaged in music therapy from 2000 to 2019. Journal of Music Therapy, Arts in Psychotherapy, Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, Music Therapy Perspectives, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In this map, the node represents a journal, and the link represents the co-citation frequency between two journals. A larger node represents more publications in the journal. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

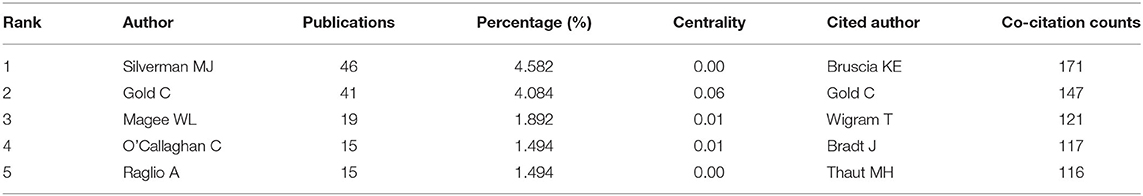

Distribution by Authors

A total of 2,531 authors contributed to the research outputs related to music therapy. Author Silverman MJ published most of the studies (46) in terms of number of publications, followed by Gold C (41), Magee WL (19), O'Callaghan C (15), and Raglio A (15). According to co-citation counts, Bruscia KE (171 citations) was the most co-cited author, followed by Gold C (147 citations), Wigram T (121 citations), and Bradt J (117 citations), as presented in Table 4 . In Figure 7 , these nodes highlight the co-citation networks of the authors. The large-sized node represented author Bruscia KE, indicating that this author owned the most co-citations. Furthermore, the linear regression results revealed a remarkable increase in the percentages of multiple articles of authors ( t = 13.089, P < 0.001). These also indicated that cooperation among authors had increased remarkably, which can be considered an important development in music therapy research.

Table 4 . Top five authors of publications and top five authors of co-citation counts.

Figure 7 . The network of author co-citaion. In this map, the node represents an author, and the link represents the co-citation frequency between two authors. A larger node represents more publications of the author. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field.

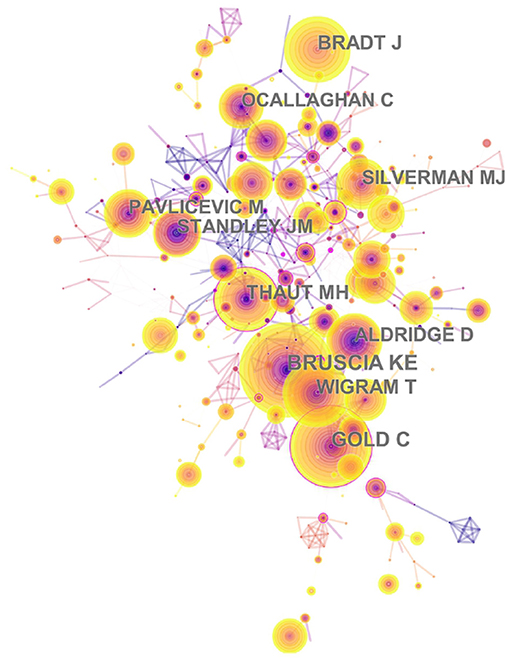

Analysis of Keywords

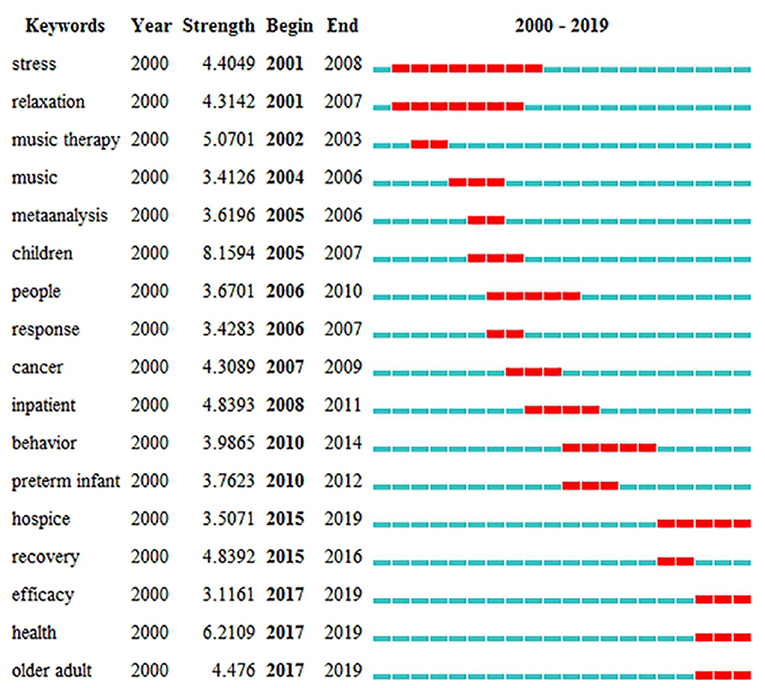

The results of keywords analysis indicated research hotspots and help scholars identify future research topics. Table 5 highlights 20 keywords with the most frequencies, such as “music therapy,” “anxiety,” “intervention,” “children,” and “depression.” The keyword “autism” has the highest centrality (0.42). Figure 8 shows the top 17 keywords with the strongest citation bursts. By the end of 2019, keyword bursts were led by “hospice,” which had the strongest burst (3.5071), followed by “efficacy” (3.1161), “health” (6.2109), and “older adult” (4.476).

Table 5 . Top 20 keywords with the most frequency and centrality in music therapy study.

Figure 8 . The strongest citation bursts of the top 17 keywords. The red measures indicate frequent citation of keywords, and the green measures indicate infrequent citation of keywords.

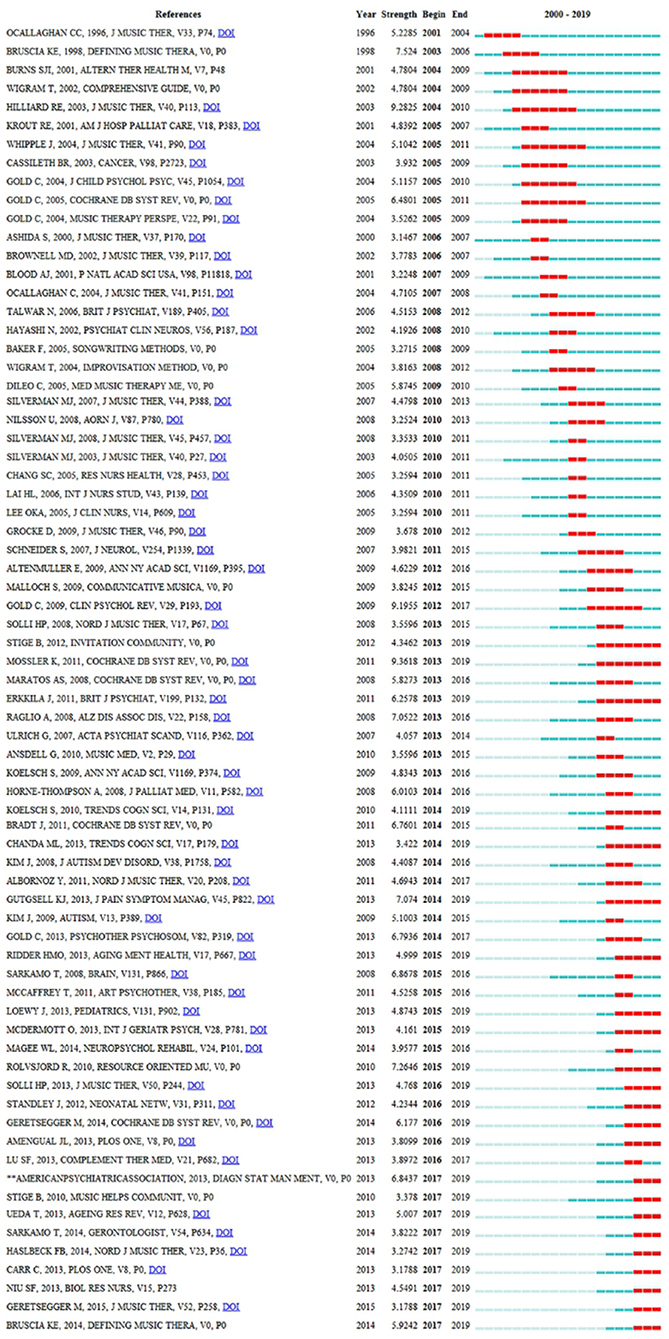

Analysis of Co-cited References

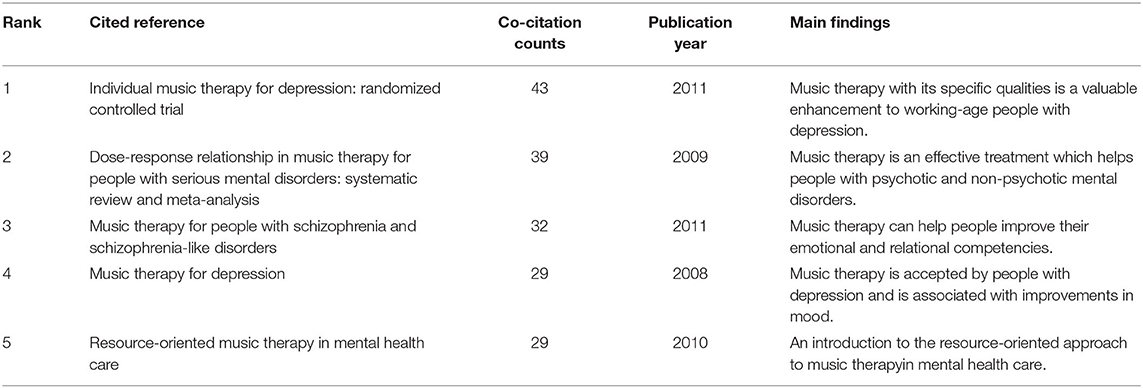

The analysis of co-cited references is a significant indicator in the bibliometric method ( Chen, 2006 ). The top five co-cited references and their main findings are listed in Table 6 . These are regarded as fundamental studies for the music therapy knowledge base. In terms of co-citation counts, “individual music therapy for depression: randomized controlled trial” was the key reference because it had the most co-citation counts. This study concludes that music therapy mixed with standard care is an effective way to treat working-age people with depression. The authors also explained that music therapy is a valuable enhancement to established treatment practices ( Erkkilä et al., 2011 ). Meanwhile, the strongest citation burst of reference is regarded as the main knowledge of the trend ( Fitzpatrick, 2005 ). Figure 9 highlights the top 71 strongest citation bursts of references from 2000 to 2019. As can be seen, by the end of 2019, the reference burst was led by author Stige B, and the strongest burst was 4.3462.

Table 6 . Top five co-cited references with co-citation counts in the study of music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

Figure 9 . The strongest citation bursts among the top 71 references. The red measures indicate frequent citation of studies, and the green measures indicate infrequent citation of studies.

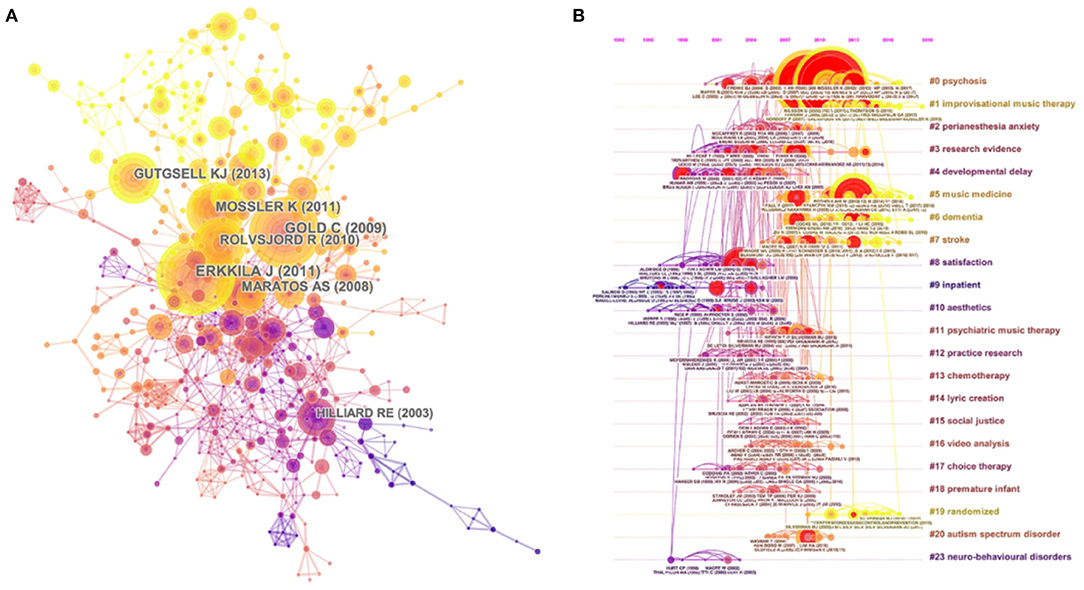

Figure 10A presents the co-cited reference map containing 577 nodes and 1,331 links. The figure explains the empirical relevance of a considerable number of articles and reviews. Figure 10B presents the co-citation map (timeline view) of reference from publications on top music therapy research. The timeline view of clusters shows the research progress of music therapy in a particular period of time and the thematic concentration of each cluster. “Psychosis” was labeled as the largest cluster (#0), followed by “improvisational music therapy” (#1) and “paranesthesia anxiety” (#2). These clusters have also remained hot topics in recent years. Furthermore, the result of the modularity Q score was 0.8258. That this value exceeded 0.5 indicated that the definitions of the subdomain and characters of clusters were distinct. In addition, the mean silhouette was 0.5802, which also exceeded 0.5. The high homogeneity of individual clusters indicated high concentration in different research areas.

Figure 10. (A) The network map of co-cited references and (B) the map (timeline view) of references with co-citation on top music therapy research. In these maps, the node represents a study, and the link represents the co-citation frequency between two studies. A larger node represents more publications of the author. A thicker purple circle represents greater influence in this field. (A) The nodes in the same color belong to the same cluster. (B) The nodes on the same line belong to the same cluster.

Global Trends in Music Therapy Research

This study conducted a bibliometric analysis of music therapy research from the past two decades. The results, which reveal that music therapy studies have been conducted throughout the world, among others, can provide further research suggestions to scholars. In terms of the general analysis of the publications, the features of published articles and reviews, prolific countries or regions, and productive institutions are summarized below.

I. The distribution of publication year has been increasing in the past two decades. The annual publication outputs of music therapy from 2000 to 2019 were divided into three stages: beginning, second, and third. In the beginning stage, there were <30 annual publications from 2000 to 2006. The second stage was between 2007 and 2014. The number of publications increased steadily. It was 2007, which marked the first time 40 articles or reviews were published. The third stage was between 2015 and 2019. The year 2015 was the key turning point because it was the first time 80 articles or reviews were published. The number of publications showed a downward trend in 2016 (72), but it was still higher than the average number of the previous years. Overall, music therapy-related research has received increasing attention among scholars from 2000 to 2020.

II. The articles and reviews covered about 49 countries or regions, and the prolific countries or regions were mainly located in the North American and European continents. According to citations on WoS, citations per study, and the H-index, music therapy publications from developed countries, such as United States and Norway, have greater influence than those from other countries. In addition, China, as a model of a developing country, had published 53 studies and ranked top six among productive countries.

III. In terms of the collaboration map of institutions, the most productive universities engaged in music therapy were located in the United States, namely, University of Minnesota (43 publications), Florida State University (33 publications), Temple University (27 publications), and University of Kansas (20 publications). It indicated that institutions in the US have significant impacts in this area.

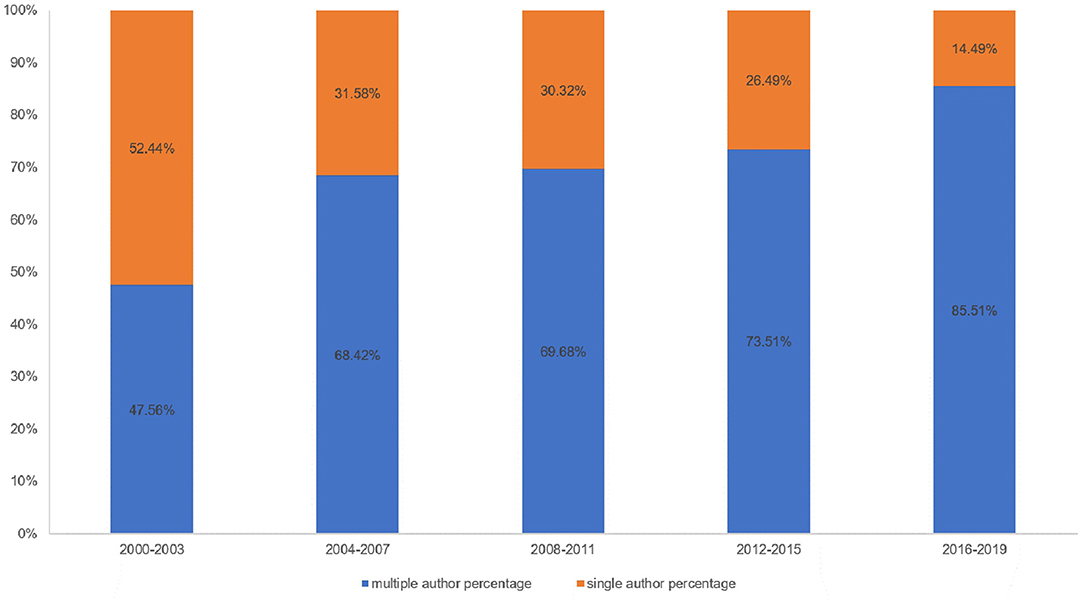

IV. According to author co-citation counts, scholars can focus on the publications of such authors as Bruscia KE, Gold C, and Wigram T. These three authors come from the United States, Norway, and Denmark, and it also reflected that these three countries are leading the research trend. Author Bruscia KE has the largest co-citation counts and is based at Temple University. He published many music therapy studies about assessment and clinical evaluation in music therapy, music therapy theories, and therapist experiences. These publications laid a foundation and facilitate the development of music therapy. In addition, in Figure 11 , the multi-authored articles between 2000 and 2003 comprised 47.56% of the sample, whereas the publications of multi-authored articles increased significantly from 2016 to 2019 (85.51%). These indicated that cooperation is an effective factor in improving the quality of publications.

Figure 11 . The percentage of single- vs. multiple-authored articles. Blue bars mean multiple-author percentage; orange bars mean single-author percentage.

Research Focus on the Research Frontier and Hot Topics

According to the science map analysis, hot music therapy topics among publications are discussed.

I. The cluster “#1 improvisational music therapy” (IMT) is the current research frontier in the music therapy research field. In general, music therapy has a long research tradition within autism spectrum disorders (ASD), and there have been more rigorous studies about it in recent years. IMT for children with autism is described as a child-centered method. Improvisational music-making may enhance social interaction and expression of emotions among children with autism, such as responding to communication acts ( Geretsegger et al., 2012 , 2015 ). In addition, IMT is an evidence-based treatment approach that may be helpful for people who abuse drugs or have cancer. A study applied improving as a primary music therapeutic practice, and the result indicated that IMT will be effective in treating depression accompanied by drug abuse among adults ( Albornoz, 2011 ). By applying the interpretative phenomenological analysis and psychological perspectives, a study explained the significant role of music therapy as an innovative psychological intervention in cancer care settings ( Pothoulaki et al., 2012 ). IMT may serve as an effective additional method for treating psychiatric disorders in the short and medium term, but it may need more studies to identify the long-term effects in clinical practice.

II. Based on the analysis of co-citation counts, the top three references all applied music therapy to improve the quality of life of clients. They highlight the fact that music therapy is an effective method that can cover a range of clinical skills, thus helping people with psychological disorders, chronic illnesses, and pain management issues. Furthermore, music therapy mixed with standard care can help individuals with schizophrenia improve their global state, mental state (including negative and general symptoms), social functioning, and quality of life ( Gold et al., 2009 ; Erkkilä et al., 2011 ; Geretsegger et al., 2017 ).

III. By understanding the keywords with the strongest citation bursts, the research frontier can be predicted. Three keywords, “efficacy,” “health,” and “older adults,” emphasized the research trends in terms of the strongest citation bursts.

a. Efficacy: This refers to measuring the effectiveness of music therapy in terms of clinical skills. Studies have found that a wide variety of psychological disorders can be effectively treated with music. In the study of Fukui, patients with Alzheimer's disease listened to music and verbally communicated with their music therapist. The results showed that problematic behaviors of the patients with Alzheimer's disease decreased ( Fukui et al., 2012 ). The aim of the study of Erkkila was to determine the efficacy of music therapy when added to standard care. The result of this study also indicated that music therapy had specific qualities for non-verbal expression and communication when patients cannot verbally describe their inner experiences ( Erkkilä et al., 2011 ). Additionally, as summarized by Ueda, music therapy reduced anxiety and depression in patients with dementia. However, his study cannot clarify what kinds of music therapy or patients have effectiveness. Thus, future studies should investigate music therapy with good methodology and evaluation methods ( Ueda et al., 2013 ).

b. Health: Music therapy is a methodical intervention in clinical practice because it uses music experiences and relationships to promote health for adults and children ( Bruscia, 1998 ). Also, music therapy is an effective means of achieving the optimal health and well-being of individuals and communities, because it can be individualized or done as a group activity. The stimulation from music therapy can lead to conversations, recollection of memories, and expression. The study of Gold indicated that solo music therapy in routine practice is an effective addition to usual care for mental health care patients with low motivation ( Gold et al., 2013 ). Porter summarized that music therapy contributes to improvement for both kids and teenagers with mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, and increases self-esteem in the short term ( Porter et al., 2017 ).

c. Older adults: This refers to the use of music therapy as a treatment to maintain and slow down the symptoms observed in older adults ( Mammarella et al., 2007 ; Deason et al., 2012 ). In terms of keywords with the strongest citation bursts, the most popular subjects of music therapy-related articles and reviews focused on children from 2005 to 2007. However, various researchers concentrated on older adults from 2017 to 2019. Music therapy was the treatment of choice for older adults with depression, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disorders ( Brotons and Koger, 2000 ; Bernatzky et al., 2004 ; Johnson et al., 2011 ; Deason et al., 2012 ; McDermott et al., 2013 ; Sakamoto et al., 2013 ; Benoit et al., 2014 ; Pohl et al., 2020 ). In the study of Zhao, music therapy had positive effects on the reduction of depressive symptoms for older adults when added to standard therapies. These standard therapies could be standard care, standard drug treatment, standard rehabilitation, and health education ( Zhao et al., 2016 ). The study of Shimizu demonstrated that multitask movement music therapy was an effective intervention to enhance neural activation in older adults with mild cognitive impairment ( Shimizu et al., 2018 ). However, the findings of the study of Li explained that short-term music therapy intervention cannot improve the cognitive function of older adults. He also recommended that future researchers can apply a quality methodology with a long-term research design for the care needs of older adults ( Li et al., 2015 ).

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first one to analyze large-scale data of music therapy publications from the past two decades through CiteSpace V. CiteSpace could detect more comprehensive results than simply reviewing articles and studies. In addition, the bibliometric method helped us to identify the emerging trend and collaboration among authors, institutions, and countries or regions.

This study is not without limitations. First, only articles and reviews published in the WoS Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index were analyzed. Future reviews could consider other databases, such as PubMed and Scopus. The document type labeled by publishers is not always accurate. For example, some publications labeled by WoS were not actually reviews ( Harzing, 2013 ; Yeung, 2021 ). Second, the limitation may induce bias in frequency of reference. For example, some potential articles were published recently, and these studies could be not cited with frequent times. Also, in terms of obliteration by incorporation, some common knowledge or opinions become accepted that their contributors or authors are no longer cited ( Merton, 1965 ; Yeung, 2021 ). Third, this review applied the quantitative analysis approach, and only limited qualitative analysis was performed in this study. In addition, we applied the CitesSpace software to conduct this bibliometric study, but the CiteSpace software did not allow us to complicate information under both full counting and fractional counting systems. Thus, future scholars can analyze the development of music therapy in some specific journals using both quantitative and qualitative indicators.

Conclusions

This bibliometric study provides information regarding emerging trends in music therapy publications from 2000 to 2019. First, this study presents several theoretical implications related to publications that may assist future researchers to advance their research field. The results reveal that annual publications in music therapy research have significantly increased in the last two decades, and the overall trend in publications increased from 28 publications in 2000 to 111 publications in 2019. This analysis also furthers the comprehensive understanding of the global research structure in the field. Also, we have stated a high level of collaboration between different countries or regions and authors in the music therapy research. This collaboration has extremely expanded the knowledge of music therapy. Thus, future music therapy professionals can benefit from the most specialized research.

Second, this research represents several practical implications. IMT is the current research frontier in the field. IMT usually serves as an effective music therapy method for the health of people in clinical practice. Identifying the emerging trends in this field will help researchers prepare their studies on recent research issues ( Mulet-Forteza et al., 2021 ). Likewise, it also indicates future studies to address these issues and update the existing literature. In terms of the strongest citation bursts, the three keywords, “efficacy,” “health,” and “older adults,” highlight the fact that music therapy is an effective invention, and it can benefit the health of people. The development prospects of music therapy could be expected, and future scholars could pay attention to the clinical significance of music therapy to the health of people.

Finally, multiple researchers have indicated several health benefits of music therapy, and the music therapy mechanism perspective is necessary for future research to advance the field. Also, music therapy can benefit a wide range of individuals, such as those with autism spectrum, traumatic brain injury, or some physical disorders. Future researchers can develop music therapy standards to measure clinical practice.

Author Contributions

KL and LW: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing—review, and editing. LW: software and data curation. KL: validation and writing—original draft preparation. XW: visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation of China (161092), the scientific and technological research program of the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (19080503100), and the Shanghai Key Lab of Human Performance (Shanghai University of Sport) (11DZ2261100).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

WoS, Web of Science; ESI, essential science indicators; IF, impact factor; IMT, improvisational music therapy; ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Albornoz, Y. (2011). The effects of group improvisational music therapy on depression in adolescents and adults with substance abuse: a randomized controlled trial. Nord. J. Music Ther. 20, 208–224. doi: 10.1080/08098131.2010.522717

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Association, A. M. T. (2018). History of Music Therapy . Available online at: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/history/ (accessed November 10, 2020).

Google Scholar

Benoit, C. E., Dalla Bella, S., Farrugia, N., Obrig, H., Mainka, S., and Kotz, S. A. (2014). Musically cued gait-training improves both perceptual and motor timing in Parkinson's disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:494. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00494

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bernatzky, G., Bernatzky, P., Hesse, H. P., Staffen, W., and Ladurner, G. (2004). Stimulating music increases motor coordination in patients afflicted with Morbus Parkinson. Neurosci. Lett. 361, 4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.022

Bronson, H., Vaudreuil, R., and Bradt, J. (2018). Music therapy treatment of active duty military: an overview of intensive outpatient and longitudinal care programs. Music Ther. Perspect. 36, 195–206. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miy006

Brotons, M., and Koger, S. M. (2000). The impact of music therapy on language functioning in dementia. J. Music Ther. 37, 183–195. doi: 10.1093/jmt/37.3.183

Bruscia, K. (1998). Defining Music Therapy 2nd Edition . Gilsum: Barcelona publications.

Castanha, R. C. G., and Grácio, M. C. C. (2014). Bibliometrics contribution to the metatheoretical and domain analysis studies. Knowl. Organiz. 41, 171–174. doi: 10.5771/0943-7444-2014-2-171

Chen, C. (2006). CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 57, 359–377. doi: 10.1002/asi.20317

Chen, C., Hu, Z., Liu, S., and Tseng, H. (2012). Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12, 593–608. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.674507

Chen, H., Zhao, G., and Xu, N. (2012). “The analysis of research hotspots and fronts of knowledge visualization based on CiteSpace II,” in International Conference on Hybrid Learning , Vol. 7411, eds S. K. S. Cheung, J. Fong, L. F. Kwok, K. Li, and R. Kwan (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 57–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-32018-_6

Deason, R., Simmons-Stern, N., Frustace, B., Ally, B., and Budson, A. (2012). Music as a memory enhancer: Differences between healthy older adults and patients with Alzheimer's disease. Psychomusicol. Music Mind Brain 22:175. doi: 10.1037/a0031118

Devlin, K., Alshaikh, J. T., and Pantelyat, A. (2019). Music therapy and music-based interventions for movement disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 19:83. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-1005-0

Durieux, V., and Gevenois, P. A. (2010). Bibliometric indicators: quality measurements of scientific publication. Radiology 255, 342–351. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090626

Ellegaard, O., and Wallin, J. A. (2015). The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics 105, 1809–1831. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1645-z

Erkkilä, J., Punkanen, M., Fachner, J., Ala-Ruona, E., Pöntiö, I., Tervaniemi, M., et al. (2011). Individual music therapy for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 199, 132–139. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085431

Falagas, M. E., Pitsouni, E. I., Malietzis, G. A., and Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. Faseb J. 22, 338–342. doi: 10.1096/FJ.07-9492LSF

Fitzpatrick, R. B. (2005). Essential Science IndicatorsSM. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 24, 67–78. doi: 10.1300/J115v24n04_05

Fukui, H., Arai, A., and Toyoshima, K. (2012). Efficacy of music therapy in treatment for the patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2012, 531646–531646. doi: 10.1155/2012/531646

Geretsegger, M., Holck, U., Carpente, J. A., Elefant, C., Kim, J., and Gold, C. (2015). Common characteristics of improvisational approaches in music therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder: developing treatment guidelines. J. Music Ther. 52, 258–281. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thv005

Geretsegger, M., Holck, U., and Gold, C. (2012). Randomised controlled trial of improvisational music therapy's effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders (TIME-A): study protocol. BMC Pediatr. 12:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-2

Geretsegger, M., Mossler, K. A., Bieleninik, L., Chen, X. J., Heldal, T. O., and Gold, C. (2017). Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5:CD004025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub4

Gold, C., Mössler, K., Grocke, D., Heldal, T. O., Tjemsland, L., Aarre, T., et al. (2013). Individual music therapy for mental health care clients with low therapy motivation: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 82, 319–331. doi: 10.1159/000348452

Gold, C., Solli, H. P., Krüger, V., and Lie, S. A. (2009). Dose-response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.001

Gonzalez-Serrano, M. H., Jones, P., and Llanos-Contrera, O. (2020). An overview of sport entrepreneurship field: a bibliometric analysis of the articles published in the Web of Science. Sport Soc. 23, 296–314. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2019.1607307

Gooding, L. F., and Langston, D. G. (2019). Music therapy with military populations: a scoping review. J. Music Ther. 56, 315–347. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thz010

Harzing, A.-W. (2013). Document categories in the ISI web of knowledge: misunderstanding the social sciences? Scientometrics 94, 23–34. doi: 10.1007/s11192-012-0738-1

Johnson, J. K., Chang, C. C., Brambati, S. M., Migliaccio, R., Gorno-Tempini, M. L., Miller, B. L., et al. (2011). Music recognition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer disease. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 24, 74–84. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31821de326

Li, H. C., Wang, H. H., Chou, F. H., and Chen, K. M. (2015). The effect of music therapy on cognitive functioning among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.10.004

Liang, Y. D., Li, Y., Zhao, J., Wang, X. Y., Zhu, H. Z., and Chen, X. H. (2017). Study of acupuncture for low back pain in recent 20 years: a bibliometric analysis via CiteSpace. J. Pain Res. 10, 951–964. doi: 10.2147/jpr.S132808

Mammarella, N., Fairfield, B., and Cornoldi, C. (2007). Does music enhance cognitive performance in healthy older adults? The Vivaldi effect. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 19, 394–399. doi: 10.1007/bf03324720

McDermott, O., Crellin, N., Ridder, H. M., and Orrell, M. (2013). Music therapy in dementia: a narrative synthesis systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 781–794. doi: 10.1002/gps.3895

Merigó, J. M., Mulet-Forteza, C., Valencia, C., and Lew, A. A. (2019). Twenty years of tourism Geographies: a bibliometric overview. Tour. Geograph. 21, 881–910. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2019.1666913

Merton, R. K. (1965). On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript . New York, NY: Free Press.

Miao, Y., Xu, S. Y., Chen, L. S., Liang, G. Y., Pu, Y. P., and Yin, L. H. (2017). Trends of long noncoding RNA research from 2007 to 2016: a bibliometric analysis. Oncotarget 8, 83114–83127. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20851

Mulet-Forteza, C., Lunn, E., Merigó, J. M., and Horrach, P. (2021). Research progress in tourism, leisure and hospitality in Europe (1969–2018). Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manage. 33, 48–74. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2020-0521

Pohl, P., Wressle, E., Lundin, F., Enthoven, P., and Dizdar, N. (2020). Group-based music intervention in Parkinson's disease - findings from a mixed-methods study. Clin. Rehabil. 34, 533–544. doi: 10.1177/0269215520907669

Porter, S., McConnell, T., McLaughlin, K., Lynn, F., Cardwell, C., Braiden, H. J., et al. (2017). Music therapy for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: a randomised controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 586–594. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12656

Pothoulaki, M., MacDonald, R., and Flowers, P. (2012). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of an improvisational music therapy program for cancer patients. J. Music Ther. 49, 45–67. doi: 10.1093/jmt/49.1.45

Sakamoto, M., Ando, H., and Tsutou, A. (2013). Comparing the effects of different individualized music interventions for elderly individuals with severe dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 25, 775–784. doi: 10.1017/s1041610212002256

Shimizu, N., Umemura, T., Matsunaga, M., and Hirai, T. (2018). Effects of movement music therapy with a percussion instrument on physical and frontal lobe function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment. Health 22, 1614–1626. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1379048

Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. 24, 265–269. doi: 10.1002/asi.4630240406

Ueda, T., Suzukamo, Y., Sato, M., and Izumi, S. (2013). Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 12, 628–641. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.02.003

Wang, X. Q., Peng, M. S., Weng, L. M., Zheng, Y. L., Zhang, Z. J., and Chen, P. J. (2019). Bibliometric study of the comorbidity of pain and depression research. Neural. Plast 2019:1657498. doi: 10.1155/2019/1657498

Yeung, A. W. K. (2021). Is the influence of freud declining in psychology and psychiatry? A bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:631516. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631516

Zhao, K., Bai, Z. G., Bo, A., and Chi, I. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of music therapy for the older adults with depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 31, 1188–1198. doi: 10.1002/gps.4494

Zheng, K., and Wang, X. (2019). Publications on the association between cognitive function and pain from 2000 to 2018: a bibliometric analysis using citespace. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 8940–8951. doi: 10.12659/msm.917742

Keywords: music therapy, aged, bibliometrics, health, web of science

Citation: Li K, Weng L and Wang X (2021) The State of Music Therapy Studies in the Past 20 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:697726. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697726

Received: 20 April 2021; Accepted: 12 May 2021; Published: 10 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Li, Weng and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xueqiang Wang, wangxueqiang@sus.edu.cn

† These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The State of Music Therapy Studies in the Past 20 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Kinesiology, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China.

- 2 Department of Sport Rehabilitation, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China.

- 3 Department of Sport Rehabilitation Medicine, Shanghai Shangti Orthopedic Hospital, Shanghai, China.

- PMID: 34177744

- PMCID: PMC8222602

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697726

Purpose: Music therapy is increasingly being used to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals. However, publications on the global trends of music therapy using bibliometric analysis are rare. The study aimed to use the CiteSpace software to provide global scientific research about music therapy from 2000 to 2019. Methods: Publications between 2000 and 2019 related to music therapy were searched from the Web of Science (WoS) database. The CiteSpace V software was used to perform co-citation analysis about authors, and visualize the collaborations between countries or regions into a network map. Linear regression was applied to analyze the overall publication trend. Results: In this study, a total of 1,004 studies met the inclusion criteria. These works were written by 2,531 authors from 1,219 institutions. The results revealed that music therapy publications had significant growth over time because the linear regression results revealed that the percentages had a notable increase from 2000 to 2019 ( t = 14.621, P < 0.001). The United States had the largest number of published studies (362 publications), along with the following outputs: citations on WoS (5,752), citations per study (15.89), and a high H-index value (37). The three keywords "efficacy," "health," and "older adults," emphasized the research trends in terms of the strongest citation bursts. Conclusions: The overall trend in music therapy is positive. The findings provide useful information for music therapy researchers to identify new directions related to collaborators, popular issues, and research frontiers. The development prospects of music therapy could be expected, and future scholars could pay attention to the clinical significance of music therapy to improve the quality of life of people.

Keywords: aged; bibliometrics; health; music therapy; web of science.

Copyright © 2021 Li, Weng and Wang.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Flow chart of music therapy…

Flow chart of music therapy articles and reviews inclusion.

Annual publication outputs of music…

Annual publication outputs of music therapy from 2000 to 2019.

Publications, citations on WoS (×0.01),…

Publications, citations on WoS (×0.01), citations per study, H-index, and ESL top study…

The collaborations of countries or…

The collaborations of countries or regions interested in the field. In this map,…

The relationship of institutions interested…

The relationship of institutions interested in the field. University of Melbourne, Florida State…

Network map of co-citation journals…

Network map of co-citation journals engaged in music therapy from 2000 to 2019.…

The network of author co-citaion.…

The network of author co-citaion. In this map, the node represents an author,…

The strongest citation bursts of…

The strongest citation bursts of the top 17 keywords. The red measures indicate…

The strongest citation bursts among…

The strongest citation bursts among the top 71 references. The red measures indicate…

The percentage of single- vs.…

The percentage of single- vs. multiple-authored articles. Blue bars mean multiple-author percentage; orange…

Similar articles

- Hotspots, trends, and advice: a 10-year visualization-based analysis of painting therapy from a scientometric perspective. Liang Q, Ye J, Lu Y, Dong J, Shen H, Qiu H. Liang Q, et al. Front Psychol. 2023 May 22;14:1148391. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1148391. eCollection 2023. Front Psychol. 2023. PMID: 37284478 Free PMC article. Review.

- Global scientific research on social participation of older people from 2000 to 2019: A bibliometric analysis. Fu J, Jiang Z, Hong Y, Liu S, Kong D, Zhong Z, Luo Y. Fu J, et al. Int J Older People Nurs. 2021 Jan;16(1):e12349. doi: 10.1111/opn.12349. Epub 2020 Sep 20. Int J Older People Nurs. 2021. PMID: 32951349 Free PMC article.

- Bibliometric analysis of recent sodium channel research. Zhao D, Li J, Seehus C, Huang X, Zhao M, Zhang S, Wang W, Ji HL, Guo F. Zhao D, et al. Channels (Austin). 2018;12(1):311-325. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2018.1511513. Channels (Austin). 2018. PMID: 30134757 Free PMC article.

- Global trends and performances of Mediterranean diet: A bibliometric analysis in CiteSpace. Pan C, Jiang N, Cao B, Dong C. Pan C, et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Sep 24;100(38):e27175. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027175. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021. PMID: 34559106 Free PMC article.

- Bibliometric and Visualized Analysis of 2011-2020 Publications on Physical Activity Therapy for Diabetes. Huang K, Zhu J, Xu S, Zhu R, Chen X. Huang K, et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Apr 7;9:807411. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.807411. eCollection 2022. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022. PMID: 35463021 Free PMC article. Review.

- Research hotspots and nursing inspiration in research of older adults with subjective cognitive decline from 2003 to 2023: A bibliometric analysis. Ding X, Shi J, Wang Q, Chen H, Shi X, Li Z. Ding X, et al. Int J Nurs Sci. 2024 Mar 6;11(2):222-232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2024.03.003. eCollection 2024 Apr. Int J Nurs Sci. 2024. PMID: 38707682 Free PMC article. Review.

- Effectiveness of music-based interventions for cognitive rehabilitation in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Citon LF, Hamdan AC. Citon LF, et al. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2023 Aug 10;36(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s41155-023-00259-x. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2023. PMID: 37561275 Free PMC article. Review.

- Value co-creation in business-to-business context: A bibliometric analysis using HistCite and VOS viewer. Ullah F, Shen L, Shah SHH. Ullah F, et al. Front Psychol. 2023 Jan 11;13:1027775. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1027775. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2023. PMID: 36710832 Free PMC article. Review.

- Bibliometric assessment of world scholars' international publications related to conceptual metaphor. Han Y, Peng Z, Chen H. Han Y, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Nov 22;13:1071121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1071121. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 36483716 Free PMC article.

- A visualized and scientometric analysis of research trends of weight loss in overweight/obese children and adolescents (1958-2021). Sun G, Li L, Zhang X. Sun G, et al. Front Public Health. 2022 Oct 20;10:928720. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.928720. eCollection 2022. Front Public Health. 2022. PMID: 36339176 Free PMC article.

- Albornoz Y. (2011). The effects of group improvisational music therapy on depression in adolescents and adults with substance abuse: a randomized controlled trial. Nord. J. Music Ther. 20, 208–224. 10.1080/08098131.2010.522717 - DOI

- Association A. M. T. (2018). History of Music Therapy. Available online at: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/history/ (accessed November 10, 2020).

- Benoit C. E., Dalla Bella S., Farrugia N., Obrig H., Mainka S., Kotz S. A. (2014). Musically cued gait-training improves both perceptual and motor timing in Parkinson's disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:494. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00494 - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Bernatzky G., Bernatzky P., Hesse H. P., Staffen W., Ladurner G. (2004). Stimulating music increases motor coordination in patients afflicted with Morbus Parkinson. Neurosci. Lett. 361, 4–8. 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.022 - DOI - PubMed

- Bronson H., Vaudreuil R., Bradt J. (2018). Music therapy treatment of active duty military: an overview of intensive outpatient and longitudinal care programs. Music Ther. Perspect. 36, 195–206. 10.1093/mtp/miy006 - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- Frontiers Media SA

- PubMed Central

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 22 June 2021

Mental health and music engagement: review, framework, and guidelines for future studies

- Daniel E. Gustavson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1470-4928 1 , 2 ,

- Peyton L. Coleman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5388-6886 3 ,

- John R. Iversen 4 ,

- Hermine H. Maes 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Reyna L. Gordon 2 , 3 , 8 , 9 &

- Miriam D. Lense 2 , 8 , 9

Translational Psychiatry volume 11 , Article number: 370 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

21 Citations

73 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Medical genetics

- Psychiatric disorders

Is engaging with music good for your mental health? This question has long been the topic of empirical clinical and nonclinical investigations, with studies indicating positive associations between music engagement and quality of life, reduced depression or anxiety symptoms, and less frequent substance use. However, many earlier investigations were limited by small populations and methodological limitations, and it has also been suggested that aspects of music engagement may even be associated with worse mental health outcomes. The purpose of this scoping review is first to summarize the existing state of music engagement and mental health studies, identifying their strengths and weaknesses. We focus on broad domains of mental health diagnoses including internalizing psychopathology (e.g., depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses), externalizing psychopathology (e.g., substance use), and thought disorders (e.g., schizophrenia). Second, we propose a theoretical model to inform future work that describes the importance of simultaneously considering music-mental health associations at the levels of (1) correlated genetic and/or environmental influences vs. (bi)directional associations, (2) interactions with genetic risk factors, (3) treatment efficacy, and (4) mediation through brain structure and function. Finally, we describe how recent advances in large-scale data collection, including genetic, neuroimaging, and electronic health record studies, allow for a more rigorous examination of these associations that can also elucidate their neurobiological substrates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Biological principles for music and mental health

A comprehensive investigation into the genetic relationship between music engagement and mental health

The effects of playing music on mental health outcomes

Introduction.

Music engagement, including passive listening and active music-making (singing, instrument playing), impacts socio-emotional development across the lifespan (e.g., socialization, personal/cultural identity, mood regulation, etc.), and is tightly linked with many cognitive and personality traits [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. A growing literature also demonstrates beneficial associations between music engagement and quality of life, well-being, prosocial behavior, social connectedness, and emotional competence [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Despite these advances linking engagement with music to many wellness characteristics, we have a limited understanding of how music engagement directly and indirectly contributes to mental health, including at the trait-level (e.g., depression and anxiety symptoms, substance use behaviors), clinical diagnoses (e.g., associations with major depressive disorder (MDD) or substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses), or as a treatment. Our goals in this scoping review are to (1) describe the state of music engagement research regarding its associations with mental health outcomes, (2) introduce a theoretical framework for future studies that highlight the contribution of genetic and environmental influences (and their interplay) that may give rise to these associations, and (3) illustrate some approaches that will help us more clearly elucidate the genetic/environmental and neural underpinnings of these associations.

Scope of the article

People interact with music in a wide variety of ways, with the concept of “musicality” broadly including music engagement, music perception and production abilities, and music training [ 9 ]. Table 1 illustrates the breadth of music phenotypes and example assessment measures. Research into music and mental health typically focuses on measures of music engagement, including passive (e.g., listening to music for pleasure or as a part of an intervention) and active music engagement (e.g., playing an instrument or singing; group music-making), both of which can be assessed using a variety of objective and subjective measures. We focus primarily on music engagement in the current paper but acknowledge it will also be important to examine how mental health traits relate to other aspects of musicality as well (e.g., perception and production abilities).

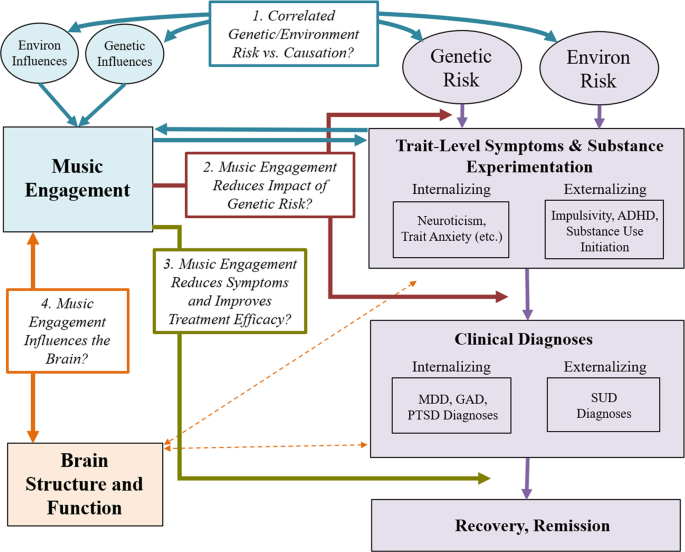

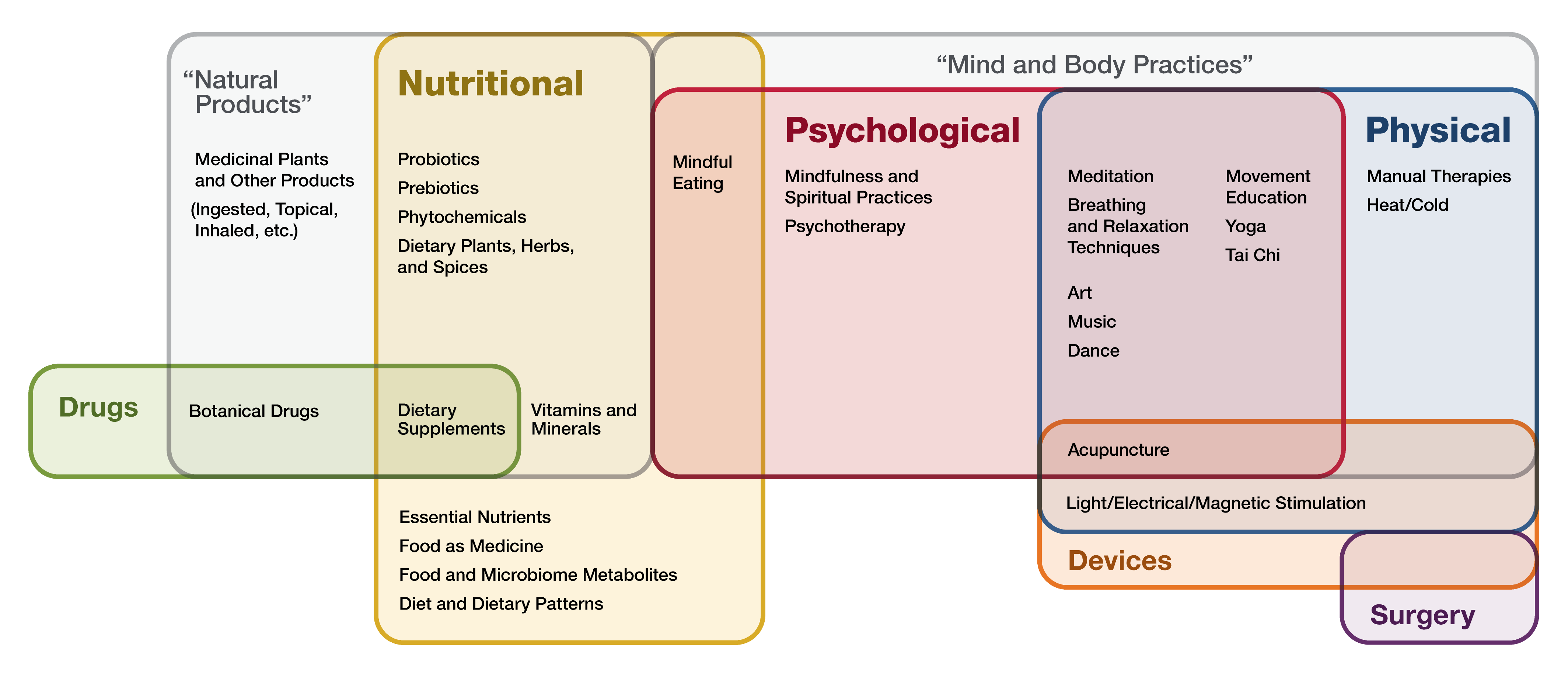

Our scoping review and theoretical framework incorporate existing theoretical and mechanistic explanations for how music engagement relates to mental health. From a psychological perspective, studies have proposed that music engagement can be used as a tool for encouraging self-expression, developing emotion regulation and coping skills, and building community [ 10 , 11 ]. From a physiological perspective, music engagement modulates arousal levels including impacts on heart rate, electrodermal activity, and cortisol [ 12 , 13 ]. These effects may be driven in part by physical aspects of music (e.g., tempo) or rhythmic movements involved in making or listening to music, which impact central nervous system functioning (e.g., leading to changes in autonomic activity) [ 14 ], as well as by personality and contextual factors (e.g., shared social experiences) [ 15 ]. Musical experiences also impact neurochemical processes involved in reward processing [ 10 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 ], which are also implicated in mental health disorders (e.g., substance use; depression). Thus, an overarching framework for studying music-mental health associations should integrate the psychological, physiological, and neurochemical aspects of these potential associations. We propose expanding this scope further through consideration of genetic and environmental risk factors, which may give rise to (and/or interact with) other factors to impact health and well-being.

Regarding mental health, it is important to recognize the hierarchical structure of psychopathology [ 19 , 20 ]. Common psychological disorders share many features and cluster into internalizing (e.g., MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)), externalizing (e.g., SUDs, conduct disorder), and thought disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), with common variance shared even across these domains [ 20 ]. These higher-order constructs tend to explain much of the comorbidity among individual disorders, and have helped researchers characterize associations between psychopathology, cognition, and personality [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. We use this hierarchical structure to organize our review. We first summarize the emerging literature on associations between music engagement and generalized well-being that provides promising evidence for associations between music engagement and mental health. Next, we summarize associations between music engagement and internalizing traits, externalizing traits/behaviors, and thought disorders, respectively. Within these sections, we critically consider the strengths and shortcomings of existing studies and how the latter may limit the conclusions drawn from this work.

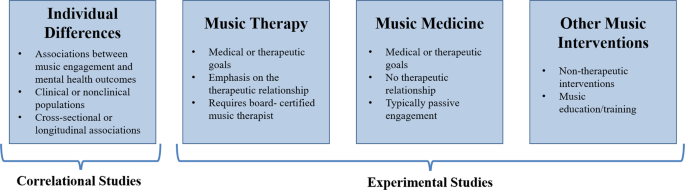

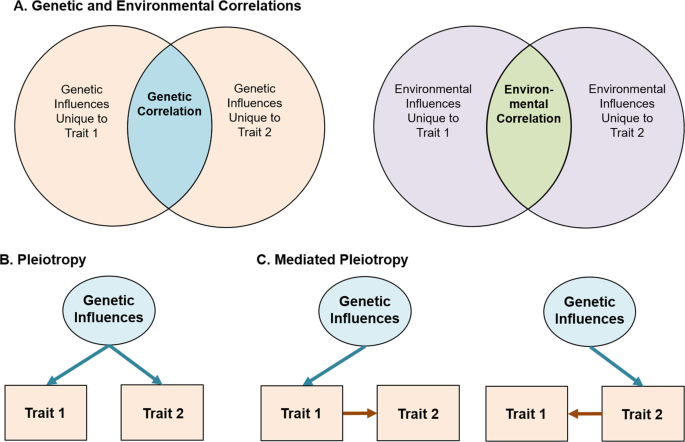

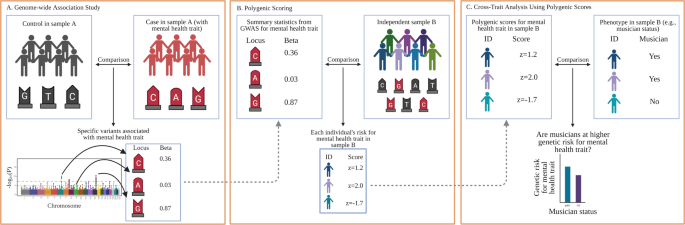

Our review considers both correlational and experimental studies (typically, intervention studies; see Fig. 1 for examples of study designs). We include not only studies that examine symptoms or diagnoses based on diagnostic interviews, but also those that assess quantitative variation (e.g., trait anxiety) in clinical and nonclinical populations. This is partly because individuals with clinical diagnoses may represent the extreme end of a spectrum of similar, sub-clinical, problems in the population, a view supported by evidence that genetic influences on diagnosed psychiatric disorders or DSM symptom counts are similar to those for trait-level symptoms in the general population [ 24 , 25 ]. Music engagement may be related to this full continuum of mental health, including correlations with trait-level symptoms in nonclinical populations and alleviation of symptoms from clinical disorders. For example, work linking music engagement to subjective well-being speaks to potential avenues for mental health interventions in the population at large.

Within experimental studies, music interventions can include passive musical activities (e.g., song listening, music and meditation, lyric discussion, creating playlists) or active musical activities (e.g., creative methods, such as songwriting or improvisation and/or re-creative methods, such as song parody).

The goal of this scoping review was to integrate across related, but often disconnected, literatures in order to propose a comprehensive theoretical framework for advancing our understanding of music-mental health associations. For this reason, we did not conduct a fully systematic search or quality appraisal of documents. Rather, we first searched PubMed and Google Scholar for review articles and meta-analyses using broad search terms (e.g., “review” and “music” and [“anxiety” or “depression” or “substance use”]). Then, when drafting each section, we searched for additional papers that have been published more recently and/or were examples of higher-quality research in each domain. When giving examples, we emphasize the most recent and most well-powered empirical studies. We also conducted some targeted literature searches where reviews were not available (e.g., “music” and [“impulsivity” or “ADHD”]) using the same databases. Our subsequent framework is intended to contextualize diagnostic, symptom, and mechanistic findings more broadly within the scope of the genetic and environmental risk factors on psychopathology that give rise to these associations and (potentially) impact the efficacy of treatment efforts. As such, the framework incorporates evidence from review articles and meta-analyses from various literatures (e.g., music interventions for anxiety [ 26 ], depression [ 27 ]) in combination with experimental evidence of biological underpinnings of music engagement and the perspective provided by newly available methods for population-health approaches (i.e., complex trait genetics, gene–environment interactions).

Music engagement and well-being

A growing body of studies report associations between music engagement and general indices of mental health, including increased well-being or emotional competence, lending support for the possibility that music engagement may also be associated with better specific mental health outcomes. In over 8000 Swedish twins, hours of music practice and self-reported music achievement were associated with better emotional competence [ 5 ]. Similarly, a meta-ethnography of 46 qualitative studies revealed that participation in music activities supported well-being through management of emotions, facilitation of self-development, providing respite from problems, and facilitating social connections [ 28 ]. In a sample of 1000 Australian adults, individuals who engaged with music, such as singing or dancing with others or attending concerts reported greater well-being vs. those who engaged in these experiences alone or did not engage. Other types of music engagement, such as playing an instrument or composing music were not associated with well-being in this sample [ 4 ]. Earlier in life, social music experiences (including song familiarity and synchronous movement to music) are associated with a variety of prosocial behaviors in infants and children [ 6 ], as well as positive affect [ 7 ]. Thus, this work provides some initial evidence that music engagement is associated with better general mental health outcomes in children and adults with some heterogeneity in findings depending on the specific type of music engagement.

Music engagement and internalizing problems

MDD, GAD, and PTSD are the most frequently clustered aspects of internalizing psychopathology [ 19 , 24 , 29 , 30 ]. Experimental studies provide evidence for the feasibility of music intervention efforts and their therapeutic benefits but are not yet rigorous enough to draw strong conclusions. The most severe limitations are small samples, the lack of appropriate control groups, few interventions with multiple sessions, and publications omitting necessary information regarding the intervention (e.g., intervention fidelity, inclusion/exclusion criteria, education status of intervention leader) [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Correlational studies, by contrast, suggest musicians are at greater risk for internalizing problems, but that they use music engagement as a tool to help manage these problems [ 34 , 35 ].

Experimental studies

Randomized controlled trials have revealed that music interventions (including both music therapies administered by board-certified music therapists and other music interventions) are associated with reduced depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms [ 26 , 27 , 33 , 36 ]. A review of 28 studies reported that 26 revealed significantly reduced depression levels in music intervention groups compared to control groups, including the 9 studies which included active non-music intervention control groups (e.g., reading sessions, “conductive-behavior” psychotherapy, antidepressant drugs) [ 27 ]. A similar meta-analysis of 19 studies demonstrated that music listening is effective at decreasing self-reported anxiety in healthy individuals [ 26 ]. A review of music-based treatment studies related to PTSD revealed similar conclusions [ 36 ], though there were only four relevant studies. More recent studies confirm these findings [ 37 , 38 , 39 ], such as one randomized controlled trial that demonstrated reduced depression symptoms in older adults following musical improvisation exercises compared to an active control group (gentle gymnastic activities) [ 39 ].

This work is promising given that some studies have observed effects even when compared to traditional behavior therapies [ 40 , 41 ]. However, there are relatively few studies directly comparing music interventions to traditional therapies. Some music interventions incorporate components of other therapeutic methods in their programs including dialectic or cognitive behavior therapies [ 42 ], but few directly compare how the inclusion of music augments traditional behavioral therapy. Still other non-music therapies incorporate music into their practice (e.g., background music in mindfulness therapies) [ 43 , 44 ], but the specific contribution of music in these approaches is unclear. Thus, there is a great need for further systematic research relating music to traditional therapies to understand which components of music interventions act on the same mechanisms as traditional therapies (e.g., developing coping mechanisms and building community) and which bolster or synchronize with other approaches (e.g., by adding structure, reinforcement, predictability, and social context to traditional approaches).

Aside from comparison with other therapeutic approaches, an earlier review of 98 papers from psychiatric in-patient studies concluded that promising effects of music therapy were limited by small sample sizes and methodological shortcomings including lack of reporting of adverse events, exclusion criteria, possible confounders, and characteristics of patients lost to follow-up [ 33 ]. Other problems included inadequate reporting of information on the source population (e.g., selection of patients and proportion agreeing to take part in the study), the lack of masking of interviewers during post-test, and concealment of randomization. Nevertheless, there was some evidence that therapies with active music participation, structured sessions, and multiple sessions (i.e., four or more) improved mood, with all studies incorporating these characteristics reporting significant positive effects. However, most studies have focused on passive interventions, such as music listening [ 26 , 27 ]. Active interventions (e.g., singing, improvising) have not been directly compared with passive interventions [ 27 ], so more work is needed to clarify whether therapeutic effects are indeed stronger with more engaging and active interventions.

Correlational studies

Correlational studies have focused on the use of music in emotional self-regulation. Specifically, individuals high in neuroticism appear to use music to help regulate their emotions [ 34 , 35 ], with beneficial effects of music engagement on emotion regulation and well-being driven by cognitive reappraisal [ 45 ]. Music listening may also moderate the association between neuroticism and depression in adolescents [ 46 ], consistent with a protective effect.

A series of recent studies have used validated self-reported instruments that directly assess how individuals use music activities as an emotion regulation strategy [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. In adults, the use of music listening for anger regulation and anxiety regulation was positively associated with subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and social well-being [ 50 ]. In studies of adolescents and undergraduates, the use of music listening for entertainment was associated with fewer depression and anxiety symptoms [ 51 ]. “Healthy” music engagement in adolescents (i.e., using music for relaxation and connection with others) was also positively associated with happiness and school satisfaction [ 49 ]. However, the use of music listening for emotional discharge was also associated with greater depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms [ 51 ], and “unhealthy” music engagement (e.g., ‘hiding’ in music to block others out) was associated with lower well-being, happiness, school satisfaction, and greater depression and rumination [ 49 ]. Other work has highlighted the role of valence in these associations, with individuals who listen to happier music when they are in a bad mood reporting stronger ability for music to influence their mood than those who listen to sad music while in a negative mood [ 52 , 53 ].

This work highlights the importance of considering individuals’ motivations for engaging with music in examining associations with well-being and mental health, and are consistent with the idea that individuals already experiencing depression, anxiety, and stress use music as a therapeutic tool to manage their emotions, with some strategies being more effective than others. Of course, these correlational effects may not necessarily reflect causal associations, but could be due to bidirectional influences, as suggested by claims that musicians may be at higher risk for internalizing problems [ 54 , 55 , 56 ]. It is also necessary to consider demographic and socioeconomic factors in these associations [ 57 ], for example, because arts engagement may be more strongly associated with self-esteem in those with higher education [ 58 ].

It is also necessary to clarify if musicians (professional and/or nonprofessional) represent an already high-risk group for internalizing problems. In one large study conducted in Norway ( N = 6372), professional musicians were higher in neuroticism than the general population [ 56 ]. Another study of musician cases ( N = 9803) vs. controls ( N = 49,015) identified in a US-based research database through text-mining of medical records found that musicians are at greater risk of MDD (Odds ratio [OR] = 1.21), anxiety disorders (OR = 1.25), and PTSD (OR = 1.13) [ 55 ]. However, other studies demonstrate null associations between musician status and depression symptoms [ 5 ] or mixed associations [ 59 ]. In N = 10,776 Swedish twins, for example, professional and amateur musicians had more self-reported burnout symptoms [ 54 ]. However, neither playing music in the past, amateur musicianship, nor professional musicianship was significantly associated with depression or anxiety disorder diagnoses.

Even if musicians are at higher risk, such findings can still be consistent with music-making being beneficial and therapeutic (e.g., depression medication use is elevated in individuals with depressive symptoms because it is a treatment). Clinical samples may be useful in disentangling these associations (i.e., examining if those who engage with music more frequently have reduced symptoms), and wider deployment of measures that capture emotion regulation strategies and motivations for engaging with music will help shed light on whether high-risk individuals engage with music in qualitatively different ways than others [ 51 , 57 ]. Later, we describe how also considering the role of genetic and environmental risk factors in these associations (e.g., if individuals at high genetic and/or environmental risk self-select into music environments because they are therapeutic) can help to clarify these questions.

Music engagement and externalizing problems

The externalizing domain comprises SUDs, and also includes impulsivity, conduct disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), especially in adolescents [ 20 , 24 , 60 , 61 ]. Similar to the conclusions for internalizing traits, experimental studies show promising evidence that music engagement interventions may reduce substance use, ADHD, and other externalizing symptoms, but conclusions are limited by methodological limitations. Correlational evidence is sparce, but there is less reason to suspect musicians are at higher risk for externalizing problems.

Intervention studies have demonstrated music engagement is helpful in patients with SUDs, including reducing withdrawal symptoms and stress, allowing individuals to experience emotions without craving substance use, and making substance abuse treatment sessions more enjoyable and motivating [ 62 , 63 , 64 ] (for a systematic review, see [ 65 ]). Similar to the experimental studies of internalizing traits, however, these studies would also benefit from larger samples, better controls, and higher-quality reporting standards.