What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

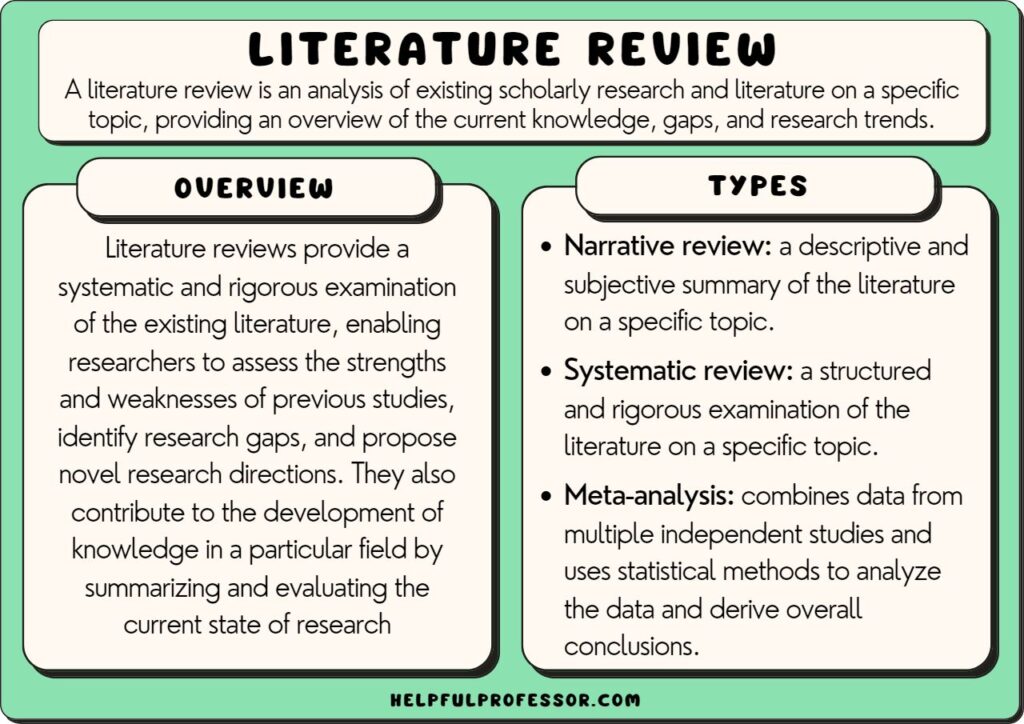

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

What is the purpose of literature review , a. habitat loss and species extinction: , b. range shifts and phenological changes: , c. ocean acidification and coral reefs: , d. adaptive strategies and conservation efforts: .

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review .

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

How to write a good literature review

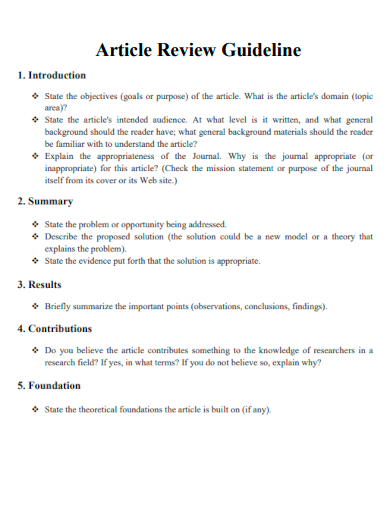

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as yo u go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free!

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

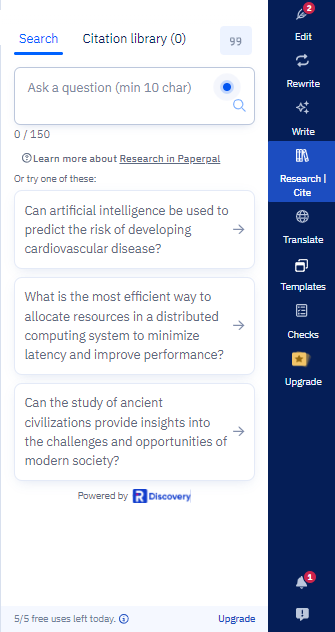

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research | Cite feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface. It also allows you auto-cite references in 10,000+ styles and save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research | Cite” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references in 10,000+ styles into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

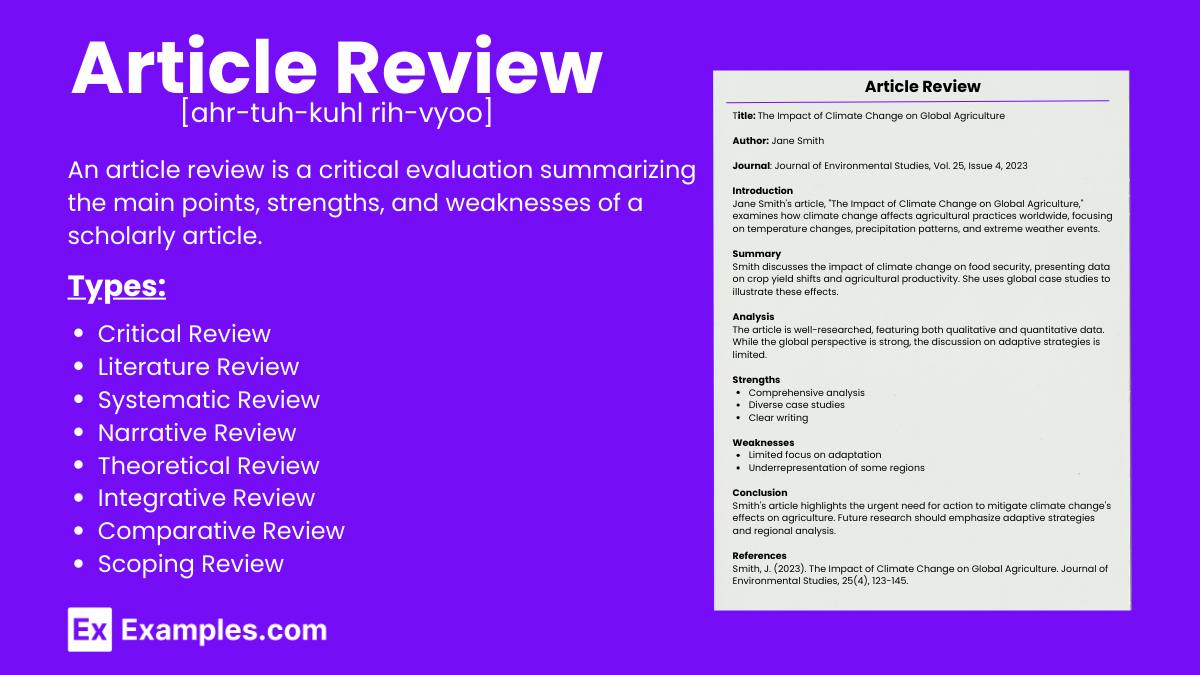

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 22+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, what are the types of literature reviews , what are research skills definition, importance, and examples , what is phd dissertation defense and how to..., abstract vs introduction: what is the difference , mla format: guidelines, template and examples , machine translation vs human translation: which is reliable..., what is academic integrity, and why is it..., how to make a graphical abstract, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is a literature review? [with examples]

What is a literature review?

The purpose of a literature review, how to write a literature review, the format of a literature review, general formatting rules, the length of a literature review, literature review examples, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

In a literature review, you’re expected to report on the existing scholarly conversation, without adding new contributions.

If you are currently writing one, you've come to the right place. In the following paragraphs, we will explain:

- the objective of a literature review

- how to write a literature review

- the basic format of a literature review

Tip: It’s not always mandatory to add a literature review in a paper. Theses and dissertations often include them, whereas research papers may not. Make sure to consult with your instructor for exact requirements.

The four main objectives of a literature review are:

- Studying the references of your research area

- Summarizing the main arguments

- Identifying current gaps, stances, and issues

- Presenting all of the above in a text

Ultimately, the main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

The format of a literature review is fairly standard. It includes an:

- introduction that briefly introduces the main topic

- body that includes the main discussion of the key arguments

- conclusion that highlights the gaps and issues of the literature

➡️ Take a look at our guide on how to write a literature review to learn more about how to structure a literature review.

First of all, a literature review should have its own labeled section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature can be found, and you should label this section as “Literature Review.”

➡️ For more information on writing a thesis, visit our guide on how to structure a thesis .

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, it will be short.

Take a look at these three theses featuring great literature reviews:

- School-Based Speech-Language Pathologist's Perceptions of Sensory Food Aversions in Children [ PDF , see page 20]

- Who's Writing What We Read: Authorship in Criminological Research [ PDF , see page 4]

- A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experience of Online Instructors of Theological Reflection at Christian Institutions Accredited by the Association of Theological Schools [ PDF , see page 56]

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

No. A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature review can be found, and label this section as “Literature Review.”

The main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

- Strategies to Find Sources

Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

Reading critically, tips to evaluate sources.

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

A good literature review evaluates a wide variety of sources (academic articles, scholarly books, government/NGO reports). It also evaluates literature reviews that study similar topics. This page offers you a list of resources and tips on how to evaluate the sources that you may use to write your review.

- A Closer Look at Evaluating Literature Reviews Excerpt from the book chapter, “Evaluating Introductions and Literature Reviews” in Fred Pyrczak’s Evaluating Research in Academic Journals: A Practical Guide to Realistic Evaluation , (Chapter 4 and 5). This PDF discusses and offers great advice on how to evaluate "Introductions" and "Literature Reviews" by listing questions and tips. First part focus on Introductions and in page 10 in the PDF, 37 in the text, it focus on "literature reviews".

- Tips for Evaluating Sources (Print vs. Internet Sources) Excellent page that will guide you on what to ask to determine if your source is a reliable one. Check the other topics in the guide: Evaluating Bibliographic Citations and Evaluation During Reading on the left side menu.

To be able to write a good Literature Review, you need to be able to read critically. Below are some tips that will help you evaluate the sources for your paper.

Reading critically (summary from How to Read Academic Texts Critically)

- Who is the author? What is his/her standing in the field.

- What is the author’s purpose? To offer advice, make practical suggestions, solve a specific problem, to critique or clarify?

- Note the experts in the field: are there specific names/labs that are frequently cited?

- Pay attention to methodology: is it sound? what testing procedures, subjects, materials were used?

- Note conflicting theories, methodologies and results. Are there any assumptions being made by most/some researchers?

- Theories: have they evolved overtime?

- Evaluate and synthesize the findings and conclusions. How does this study contribute to your project?

Useful links:

- How to Read a Paper (University of Waterloo, Canada) This is an excellent paper that teach you how to read an academic paper, how to determine if it is something to set aside, or something to read deeply. Good advice to organize your literature for the Literature Review or just reading for classes.

Criteria to evaluate sources:

- Authority : Who is the author? what is his/her credentials--what university he/she is affliliated? Is his/her area of expertise?

- Usefulness : How this source related to your topic? How current or relevant it is to your topic?

- Reliability : Does the information comes from a reliable, trusted source such as an academic journal?

Useful site - Critically Analyzing Information Sources (Cornell University Library)

- << Previous: Strategies to Find Sources

- Next: Tips for Writing Literature Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Make your writing flawless in 1 upload

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Upload my document

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

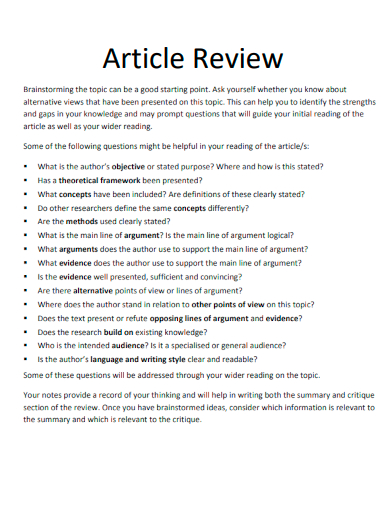

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 October 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

- The EBP Process

- Forming a Clinical Question

- Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

- Acquiring Evidence

- Appraising the Quality of the Evidence

- Writing a Literature Review

- Finding Psychological Tests & Assessment Instruments

What Is a Literature Review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis of scholarly writings that are related directly to your research question. Put simply, it's a critical evaluation of what's already been written on a particular topic . It represents the literature that provides background information on your topic and shows a connection between those writings and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand-alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

What a Literature Review Is Not:

- A list or summary of sources

- An annotated bibliography

- A grouping of broad, unrelated sources

- A compilation of everything that has been written on a particular topic

- Literary criticism (think English) or a book review

Why Literature Reviews Are Important

- They explain the background of research on a topic

- They demonstrate why a topic is significant to a subject area

- They discover relationships between research studies/ideas

- They identify major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic

- They identify critical gaps and points of disagreement

- They discuss further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies

To Learn More about Conducting and Writing a Lit Review . . .

Monash University (in Australia) has created several extremely helpful, interactive tutorials.

- The Stand-Alone Literature Review, https://www.monash.edu/rlo/assignment-samples/science/stand-alone-literature-review

- Researching for Your Literature Review, https://guides.lib.monash.edu/researching-for-your-literature-review/home

- Writing a Literature Review, https://www.monash.edu/rlo/graduate-research-writing/write-the-thesis/writing-a-literature-review

Keep Track of Your Sources!

A citation manager can be helpful way to work with large numbers of citations. See UMSL Libraries' Citing Sources guide for more information. Personally, I highly recommend Zotero —it's free, easy to use, and versatile. If you need help getting started with Zotero or one of the other citation managers, please contact a librarian.

- << Previous: Appraising the Quality of the Evidence

- Next: Finding Psychological Tests & Assessment Instruments >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 2:44 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umsl.edu/ebp

What Is A Literature Review?

A plain-language explainer (with examples).

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | June 2020 (Updated May 2023)

If you’re faced with writing a dissertation or thesis, chances are you’ve encountered the term “literature review” . If you’re on this page, you’re probably not 100% what the literature review is all about. The good news is that you’ve come to the right place.

Literature Review 101

- What (exactly) is a literature review

- What’s the purpose of the literature review chapter

- How to find high-quality resources

- How to structure your literature review chapter

- Example of an actual literature review

What is a literature review?

The word “literature review” can refer to two related things that are part of the broader literature review process. The first is the task of reviewing the literature – i.e. sourcing and reading through the existing research relating to your research topic. The second is the actual chapter that you write up in your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s look at each of them:

Reviewing the literature

The first step of any literature review is to hunt down and read through the existing research that’s relevant to your research topic. To do this, you’ll use a combination of tools (we’ll discuss some of these later) to find journal articles, books, ebooks, research reports, dissertations, theses and any other credible sources of information that relate to your topic. You’ll then summarise and catalogue these for easy reference when you write up your literature review chapter.

The literature review chapter

The second step of the literature review is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or thesis structure ). At the simplest level, the literature review chapter is an overview of the key literature that’s relevant to your research topic. This chapter should provide a smooth-flowing discussion of what research has already been done, what is known, what is unknown and what is contested in relation to your research topic. So, you can think of it as an integrated review of the state of knowledge around your research topic.

What’s the purpose of a literature review?

The literature review chapter has a few important functions within your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s take a look at these:

Purpose #1 – Demonstrate your topic knowledge

The first function of the literature review chapter is, quite simply, to show the reader (or marker) that you know what you’re talking about . In other words, a good literature review chapter demonstrates that you’ve read the relevant existing research and understand what’s going on – who’s said what, what’s agreed upon, disagreed upon and so on. This needs to be more than just a summary of who said what – it needs to integrate the existing research to show how it all fits together and what’s missing (which leads us to purpose #2, next).

Purpose #2 – Reveal the research gap that you’ll fill

The second function of the literature review chapter is to show what’s currently missing from the existing research, to lay the foundation for your own research topic. In other words, your literature review chapter needs to show that there are currently “missing pieces” in terms of the bigger puzzle, and that your study will fill one of those research gaps . By doing this, you are showing that your research topic is original and will help contribute to the body of knowledge. In other words, the literature review helps justify your research topic.

Purpose #3 – Lay the foundation for your conceptual framework

The third function of the literature review is to form the basis for a conceptual framework . Not every research topic will necessarily have a conceptual framework, but if your topic does require one, it needs to be rooted in your literature review.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the drivers of a certain outcome – the factors which contribute to burnout in office workers. In this case, you’d likely develop a conceptual framework which details the potential factors (e.g. long hours, excessive stress, etc), as well as the outcome (burnout). Those factors would need to emerge from the literature review chapter – they can’t just come from your gut!

So, in this case, the literature review chapter would uncover each of the potential factors (based on previous studies about burnout), which would then be modelled into a framework.

Purpose #4 – To inform your methodology

The fourth function of the literature review is to inform the choice of methodology for your own research. As we’ve discussed on the Grad Coach blog , your choice of methodology will be heavily influenced by your research aims, objectives and questions . Given that you’ll be reviewing studies covering a topic close to yours, it makes sense that you could learn a lot from their (well-considered) methodologies.

So, when you’re reviewing the literature, you’ll need to pay close attention to the research design , methodology and methods used in similar studies, and use these to inform your methodology. Quite often, you’ll be able to “borrow” from previous studies . This is especially true for quantitative studies , as you can use previously tried and tested measures and scales.

How do I find articles for my literature review?

Finding quality journal articles is essential to crafting a rock-solid literature review. As you probably already know, not all research is created equally, and so you need to make sure that your literature review is built on credible research .

We could write an entire post on how to find quality literature (actually, we have ), but a good starting point is Google Scholar . Google Scholar is essentially the academic equivalent of Google, using Google’s powerful search capabilities to find relevant journal articles and reports. It certainly doesn’t cover every possible resource, but it’s a very useful way to get started on your literature review journey, as it will very quickly give you a good indication of what the most popular pieces of research are in your field.

One downside of Google Scholar is that it’s merely a search engine – that is, it lists the articles, but oftentimes it doesn’t host the articles . So you’ll often hit a paywall when clicking through to journal websites.

Thankfully, your university should provide you with access to their library, so you can find the article titles using Google Scholar and then search for them by name in your university’s online library. Your university may also provide you with access to ResearchGate , which is another great source for existing research.

Remember, the correct search keywords will be super important to get the right information from the start. So, pay close attention to the keywords used in the journal articles you read and use those keywords to search for more articles. If you can’t find a spoon in the kitchen, you haven’t looked in the right drawer.

Need a helping hand?

How should I structure my literature review?

Unfortunately, there’s no generic universal answer for this one. The structure of your literature review will depend largely on your topic area and your research aims and objectives.

You could potentially structure your literature review chapter according to theme, group, variables , chronologically or per concepts in your field of research. We explain the main approaches to structuring your literature review here . You can also download a copy of our free literature review template to help you establish an initial structure.

In general, it’s also a good idea to start wide (i.e. the big-picture-level) and then narrow down, ending your literature review close to your research questions . However, there’s no universal one “right way” to structure your literature review. The most important thing is not to discuss your sources one after the other like a list – as we touched on earlier, your literature review needs to synthesise the research , not summarise it .

Ultimately, you need to craft your literature review so that it conveys the most important information effectively – it needs to tell a logical story in a digestible way. It’s no use starting off with highly technical terms and then only explaining what these terms mean later. Always assume your reader is not a subject matter expert and hold their hand through a journe y of the literature while keeping the functions of the literature review chapter (which we discussed earlier) front of mind.

Example of a literature review

In the video below, we walk you through a high-quality literature review from a dissertation that earned full distinction. This will give you a clearer view of what a strong literature review looks like in practice and hopefully provide some inspiration for your own.

Wrapping Up

In this post, we’ve (hopefully) answered the question, “ what is a literature review? “. We’ve also considered the purpose and functions of the literature review, as well as how to find literature and how to structure the literature review chapter. If you’re keen to learn more, check out the literature review section of the Grad Coach blog , as well as our detailed video post covering how to write a literature review .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

16 Comments

Thanks for this review. It narrates what’s not been taught as tutors are always in a early to finish their classes.

Thanks for the kind words, Becky. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This website is amazing, it really helps break everything down. Thank you, I would have been lost without it.

This is review is amazing. I benefited from it a lot and hope others visiting this website will benefit too.

Timothy T. Chol [email protected]

Thank you very much for the guiding in literature review I learn and benefited a lot this make my journey smooth I’ll recommend this site to my friends

This was so useful. Thank you so much.

Hi, Concept was explained nicely by both of you. Thanks a lot for sharing it. It will surely help research scholars to start their Research Journey.

The review is really helpful to me especially during this period of covid-19 pandemic when most universities in my country only offer online classes. Great stuff

Great Brief Explanation, thanks

So helpful to me as a student

GradCoach is a fantastic site with brilliant and modern minds behind it.. I spent weeks decoding the substantial academic Jargon and grounding my initial steps on the research process, which could be shortened to a couple of days through the Gradcoach. Thanks again!

This is an amazing talk. I paved way for myself as a researcher. Thank you GradCoach!

Well-presented overview of the literature!

This was brilliant. So clear. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

15 Literature Review Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Literature reviews are a necessary step in a research process and often required when writing your research proposal . They involve gathering, analyzing, and evaluating existing knowledge about a topic in order to find gaps in the literature where future studies will be needed.

Ideally, once you have completed your literature review, you will be able to identify how your research project can build upon and extend existing knowledge in your area of study.

Generally, for my undergraduate research students, I recommend a narrative review, where themes can be generated in order for the students to develop sufficient understanding of the topic so they can build upon the themes using unique methods or novel research questions.

If you’re in the process of writing a literature review, I have developed a literature review template for you to use – it’s a huge time-saver and walks you through how to write a literature review step-by-step:

Get your time-saving templates here to write your own literature review.

Literature Review Examples

For the following types of literature review, I present an explanation and overview of the type, followed by links to some real-life literature reviews on the topics.

1. Narrative Review Examples

Also known as a traditional literature review, the narrative review provides a broad overview of the studies done on a particular topic.

It often includes both qualitative and quantitative studies and may cover a wide range of years.

The narrative review’s purpose is to identify commonalities, gaps, and contradictions in the literature .

I recommend to my students that they should gather their studies together, take notes on each study, then try to group them by themes that form the basis for the review (see my step-by-step instructions at the end of the article).

Example Study

Title: Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations

Citation: Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ijcp.12686

Overview: This narrative review analyzed themes emerging from 69 articles about communication in healthcare contexts. Five key themes were found in the literature: poor communication can lead to various negative outcomes, discontinuity of care, compromise of patient safety, patient dissatisfaction, and inefficient use of resources. After presenting the key themes, the authors recommend that practitioners need to approach healthcare communication in a more structured way, such as by ensuring there is a clear understanding of who is in charge of ensuring effective communication in clinical settings.

Other Examples

- Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review (Reith, 2018) – read here

- Examining the Presence, Consequences, and Reduction of Implicit Bias in Health Care: A Narrative Review (Zestcott, Blair & Stone, 2016) – read here

- A Narrative Review of School-Based Physical Activity for Enhancing Cognition and Learning (Mavilidi et al., 2018) – read here

- A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents (Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2015) – read here

2. Systematic Review Examples

This type of literature review is more structured and rigorous than a narrative review. It involves a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy derived from a set of specified research questions.

The key way you’d know a systematic review compared to a narrative review is in the methodology: the systematic review will likely have a very clear criteria for how the studies were collected, and clear explanations of exclusion/inclusion criteria.

The goal is to gather the maximum amount of valid literature on the topic, filter out invalid or low-quality reviews, and minimize bias. Ideally, this will provide more reliable findings, leading to higher-quality conclusions and recommendations for further research.

You may note from the examples below that the ‘method’ sections in systematic reviews tend to be much more explicit, often noting rigid inclusion/exclusion criteria and exact keywords used in searches.

Title: The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review

Citation: Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092422441730122X