Hot Summer Savings ☀️ 60% Off for 4 Months. Buy Now & Save

60% Off for 4 Months Buy Now & Save

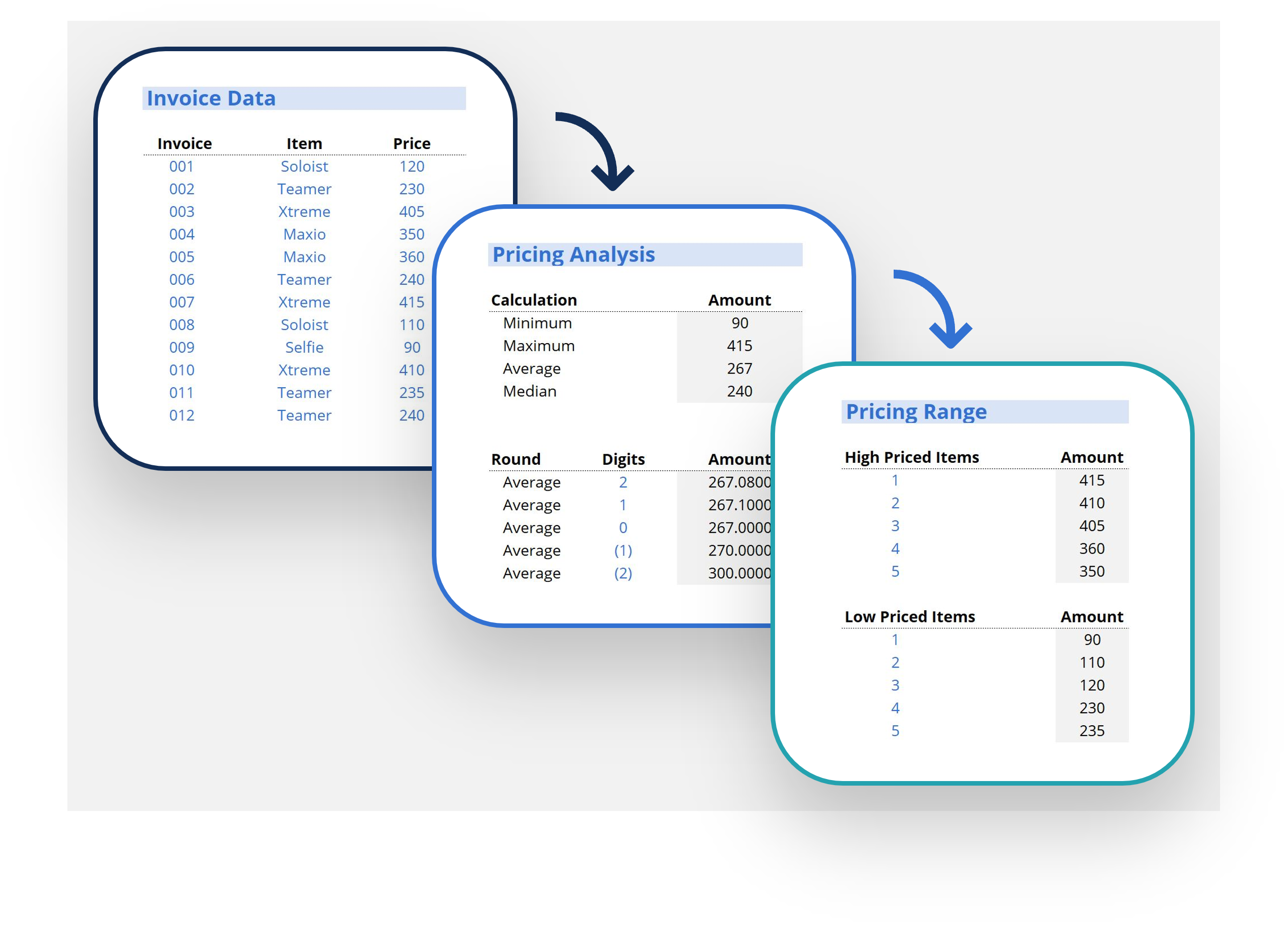

Wow clients with professional invoices that take seconds to create

Quick and easy online, recurring, and invoice-free payment options

Automated, to accurately track time and easily log billable hours

Reports and tools to track money in and out, so you know where you stand

Easily log expenses and receipts to ensure your books are always tax-time ready

Tax time and business health reports keep you informed and tax-time ready

Automatically track your mileage and never miss a mileage deduction again

Time-saving all-in-one bookkeeping that your business can count on

Track project status and collaborate with clients and team members

Organized and professional, helping you stand out and win new clients

Set clear expectations with clients and organize your plans for each project

Client management made easy, with client info all in one place

Pay your employees and keep accurate books with Payroll software integrations

- Team Management

FreshBooks integrates with over 100 partners to help you simplify your workflows

Send invoices, track time, manage payments, and more…from anywhere.

- Freelancers

- Self-Employed Professionals

- Businesses With Employees

- Businesses With Contractors

- Marketing & Agencies

- Construction & Trades

- IT & Technology

- Business & Prof. Services

- Accounting Partner Program

- Collaborative Accounting™

- Accountant Hub

- Reports Library

- FreshBooks vs QuickBooks

- FreshBooks vs HoneyBook

- FreshBooks vs Harvest

- FreshBooks vs Wave

- FreshBooks vs Xero

- Partners Hub

- Help Center

- 1-888-674-3175

- Accounting Theory

- Accounting Standard

- Accounting Convention

- Branch Accounting

- Modified Accrual Accounting

- Modified Cash Basis

- Accounting Policies

- Closing Entry

Save Time Billing and Get Paid 2x Faster With FreshBooks

- Beginning With a

Accounting Theory: Definition & Overview

Have you been wondering about accounting theory? Accounting is an important part of every business. It helps make sure financial transactions get recorded , and assists with things like payroll.

Accounting theory has the purpose of guiding accounting processes , so that everything is as accurate as possible. So , what are some of the accounting theory applications? W hat are some of the practices? There are some financial reporting principles to be aware of in the accounting industry.

We put this guide together to outline everything you need to know . Keep reading to learn all about the study of accounting theory and how it gets applied. You’ll be able to have effective accounting skills in no time.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Accounting theory guides financial reporting and accounting processes.

- It involves methodologies, frameworks, and assumptions that get used in financial reporting.

- Accounting theory evolves and adapts to environmental changes and new trends.

What Is Accounting Theory?

Accounting theory works in a few ways, and is made up of different frameworks, assumptions, and methodologies. All of this gets put into place so reporting financials are correct and accurate.

There are some foundations in accounting theory that guide accounting practices. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) put together a framework of accounting theories to use.

The FASB is an independent entity. Their focus is on outlining the key objectives and framework for reporting financials that is used by both private and public businesses. It’s the logical reasoning behind accounting practices, and as new accounting practices and procedures develop, accounting theory evolves.

Key Elements of Accounting Theory

The first key element in accounting theory is usefulness. Its main intention is to ensure financial statements make important information available. This helps to make more informed business decisions.

This means that there’s also some flexibility to accounting theory. By being flexible, it can adapt to environmental changes. The framework of accounting theory also has a few other aspects to know about.

These include being consistent, reliable, relevant, and comparable. To help guide these aspects, the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) were created.

Following GAAP ensures financial statements, and how they’re prepared, are consistent. Consistency leads to higher accuracy and makes it so that past financials are comparable to the financials of other companies.

Accounting Theory Assumptions

Within the blocks of accounting theory, there are also some assumptions. Accounting professionals follow these assumptions:

- That a business needs to be separate from its owners or creditors

- That there’s a belief that the business won’t go bankrupt and will always exist

- That financial statements get prepared with dollar amounts, not units of production

- That all financial statements get prepared either monthly or annually

Are There Any Special Considerations?

The process of accounting dates back to the 15th century; however, economies and businesses have greatly evolved since then. This means that accounting theory also evolves and adapts when required.

This can include new practices, or discovering gaps in reporting mechanisms. It can also include the advancement of new technological trends. Professional accountants contribute their knowledge to help with these changes. For example, a certified public accountant (CPA) can lend their expertise.

When this happens, new methodologies can be created to stay up-to-date, and businesses can better navigate and understand new accounting standards. All of this leads to the evolution of accounting theory.

The elements in accounting theory consist of a few different things. These include certain frameworks, assumptions, and methodologies. All of these things get used when reporting financials. The purpose is to ensure financials are consistent, accurate, and comparable.

Accounting theory gets used by businesses to make more informed decisions. The main aspect of accounting theory is its usefulness. These frameworks get designed with a few other things in mind: being reliable, consistent, relevant, and comparable.

Following basic accounting theory makes for more effective and accurate accounting practices. This can come in handy for things like an income statement or statement of cash flows.

Frequently Asked Questions

There are five main principles of accounting. They include the accrual principle, the historic cost principle, matching principle , conservatism principle , and the principle of substance over form. Following these principles allows for better accounting practices and accurate financial statements.

This relates to a few different things. It starts with equal treatment for all interested parties. It also includes having true and accurate accounting statements that aren’t misrepresented. It also includes having a fair, unbiased, and completely impartial presentation.

With the positive approach in accounting theory, the goal is to explain a process. This means using knowledge and understanding of accounting , and implementing accounting policies to deal with certain conditions. Other accounting fundamentals are also implemented.

Browse Glossary Term

WHY BUSINESS OWNERS LOVE FRESHBOOKS

SAVE UP TO 553 HOURS EACH YEAR BY USING FRESHBOOKS

SAVE UP TO $7000 IN BILLABLE HOURS EVERY YEAR

OVER 30 MILLION PEOPLE HAVE USED FRESHBOOKS WORLDWIDE

3.1 Describe Principles, Assumptions, and Concepts of Accounting and Their Relationship to Financial Statements

If you want to start your own business, you need to maintain detailed and accurate records of business performance in order for you, your investors, and your lenders, to make informed decisions about the future of your company. Financial statements are created with this purpose in mind. A set of financial statements includes the income statement, statement of owner’s equity, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows. These statements are discussed in detail in Introduction to Financial Statements . This chapter explains the relationship between financial statements and several steps in the accounting process. We go into much more detail in The Adjustment Process and Completing the Accounting Cycle .

Accounting Principles, Assumptions, and Concepts

In Introduction to Financial Statements , you learned that the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is an independent, nonprofit organization that sets the standards for financial accounting and reporting, including generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) , for both public- and private-sector businesses in the United States.

As you may also recall, GAAP are the concepts, standards, and rules that guide the preparation and presentation of financial statements. If US accounting rules are followed, the accounting rules are called US GAAP. International accounting rules are called International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) . Publicly traded companies (those that offer their shares for sale on exchanges in the United States) have the reporting of their financial operations regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) .

You also learned that the SEC is an independent federal agency that is charged with protecting the interests of investors, regulating stock markets, and ensuring companies adhere to GAAP requirements. By having proper accounting standards such as US GAAP or IFRS, information presented publicly is considered comparable and reliable. As a result, financial statement users are more informed when making decisions. The SEC not only enforces the accounting rules but also delegates the process of setting standards for US GAAP to the FASB.

Some companies that operate on a global scale may be able to report their financial statements using IFRS. The SEC regulates the financial reporting of companies selling their shares in the United States, whether US GAAP or IFRS are used. The basics of accounting discussed in this chapter are the same under either set of guidelines.

Ethical Considerations

Auditing of publicly traded companies.

When a publicly traded company in the United States issues its financial statements, the financial statements have been audited by a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) approved auditor. The PCAOB is the organization that sets the auditing standards, after approval by the SEC. It is important to remember that auditing is not the same as accounting. The role of the Auditor is to examine and provide assurance that financial statements are reasonably stated under the rules of appropriate accounting principles. The auditor conducts the audit under a set of standards known as Generally Accepted Auditing Standards. The accounting department of a company and its auditors are employees of two different companies. The auditors of a company are required to be employed by a different company so that there is independence.

The nonprofit Center for Audit Quality explains auditor independence: “Auditors’ independence from company management is essential for a successful audit because it enables them to approach the audit with the necessary professional skepticism.” 1 The center goes on to identify a key practice to protect independence by which an external auditor reports not to a company’s management, which could make it more difficult to maintain independence, but to a company’s audit committee. The audit committee oversees the auditors’ work and monitors disagreements between management and the auditor about financial reporting. Internal auditors of a company are not the auditors that provide an opinion on the financial statements of a company. According to the Center for Audit Quality, “By law, public companies’ annual financial statements are audited each year by independent auditors—accountants who examine the data for conformity with U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).” 2 The opinion from the independent auditors regarding a publicly traded company is filed for public inspection, along with the financial statements of the publicly traded company.

The Conceptual Framework

The FASB uses a conceptual framework , which is a set of concepts that guide financial reporting. These concepts can help ensure information is comparable and reliable to stakeholders. Guidance may be given on how to report transactions, measurement requirements, and application on financial statements, among other things. 3

IFRS Connection

Gaap, ifrs, and the conceptual framework.

The procedural part of accounting—recording transactions right through to creating financial statements—is a universal process. Businesses all around the world carry out this process as part of their normal operations. In carrying out these steps, the timing and rate at which transactions are recorded and subsequently reported in the financial statements are determined by the accepted accounting principles used by the company.

As you learned in Role of Accounting in Society , US-based companies will apply US GAAP as created by the FASB, and most international companies will apply IFRS as created by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). As illustrated in this chapter, the starting point for either FASB or IASB in creating accounting standards, or principles, is the conceptual framework. Both FASB and IASB cover the same topics in their frameworks, and the two frameworks are similar. The conceptual framework helps in the standard-setting process by creating the foundation on which those standards should be based. It can also help companies figure out how to record transactions for which there may not currently be an applicable standard. Though there are many similarities between the conceptual framework under US GAAP and IFRS, these similar foundations result in different standards and/or different interpretations.

Once an accounting standard has been written for US GAAP, the FASB often offers clarification on how the standard should be applied. Businesses frequently ask for guidance for their particular industry. When the FASB creates accounting standards and any subsequent clarifications or guidance, it only has to consider the effects of those standards, clarifications, or guidance on US-based companies. This means that FASB has only one major legal system and government to consider. When offering interpretations or other guidance on application of standards, the FASB can utilize knowledge of the US-based legal and taxation systems to help guide their points of clarification and can even create interpretations for specific industries. This means that interpretation and guidance on US GAAP standards can often contain specific details and guidelines in order to help align the accounting process with legal matters and tax laws.

In applying their conceptual framework to create standards, the IASB must consider that their standards are being used in 120 or more different countries, each with its own legal and judicial systems. Therefore, it is much more difficult for the IASB to provide as much detailed guidance once the standard has been written, because what might work in one country from a taxation or legal standpoint might not be appropriate in a different country. This means that IFRS interpretations and guidance have fewer detailed components for specific industries as compared to US GAAP guidance.

The conceptual framework sets the basis for accounting standards set by rule-making bodies that govern how the financial statements are prepared. Here are a few of the principles, assumptions, and concepts that provide guidance in developing GAAP.

Revenue Recognition Principle

The revenue recognition principle directs a company to recognize revenue in the period in which it is earned; revenue is not considered earned until a product or service has been provided. This means the period of time in which you performed the service or gave the customer the product is the period in which revenue is recognized.

There also does not have to be a correlation between when cash is collected and when revenue is recognized. A customer may not pay for the service on the day it was provided. Even though the customer has not yet paid cash, there is a reasonable expectation that the customer will pay in the future. Since the company has provided the service, it would recognize the revenue as earned, even though cash has yet to be collected.

For example, Lynn Sanders owns a small printing company, Printing Plus. She completed a print job for a customer on August 10. The customer did not pay cash for the service at that time and was billed for the service, paying at a later date. When should Lynn recognize the revenue, on August 10 or at the later payment date? Lynn should record revenue as earned on August 10. She provided the service to the customer, and there is a reasonable expectation that the customer will pay at the later date.

Expense Recognition (Matching) Principle

The expense recognition principle (also referred to as the matching principle ) states that we must match expenses with associated revenues in the period in which the revenues were earned. A mismatch in expenses and revenues could be an understated net income in one period with an overstated net income in another period. There would be no reliability in statements if expenses were recorded separately from the revenues generated.

For example, if Lynn earned printing revenue in April, then any associated expenses to the revenue generation (such as paying an employee) should be recorded on the same income statement. The employee worked for Lynn in April, helping her earn revenue in April, so Lynn must match the expense with the revenue by showing both on the April income statement.

Cost Principle

The cost principle , also known as the historical cost principle , states that virtually everything the company owns or controls ( assets ) must be recorded at its value at the date of acquisition. For most assets, this value is easy to determine as it is the price agreed to when buying the asset from the vendor. There are some exceptions to this rule, but always apply the cost principle unless FASB has specifically stated that a different valuation method should be used in a given circumstance.

The primary exceptions to this historical cost treatment, at this time, are financial instruments, such as stocks and bonds, which might be recorded at their fair market value. This is called mark-to-market accounting or fair value accounting and is more advanced than the general basic concepts underlying the introduction to basic accounting concepts; therefore, it is addressed in more advanced accounting courses.

Once an asset is recorded on the books, the value of that asset must remain at its historical cost, even if its value in the market changes. For example, Lynn Sanders purchases a piece of equipment for $40,000. She believes this is a bargain and perceives the value to be more at $60,000 in the current market. Even though Lynn feels the equipment is worth $60,000, she may only record the cost she paid for the equipment of $40,000.

Full Disclosure Principle

The full disclosure principle states that a business must report any business activities that could affect what is reported on the financial statements. These activities could be nonfinancial in nature or be supplemental details not readily available on the main financial statement. Some examples of this include any pending litigation, acquisition information, methods used to calculate certain figures, or stock options. These disclosures are usually recorded in footnotes on the statements, or in addenda to the statements.

Separate Entity Concept

The separate entity concept prescribes that a business may only report activities on financial statements that are specifically related to company operations, not those activities that affect the owner personally. This concept is called the separate entity concept because the business is considered an entity separate and apart from its owner(s).

For example, Lynn Sanders purchases two cars; one is used for personal use only, and the other is used for business use only. According to the separate entity concept, Lynn may record the purchase of the car used by the company in the company’s accounting records, but not the car for personal use.

Conservatism

This concept is important when valuing a transaction for which the dollar value cannot be as clearly determined, as when using the cost principle. Conservatism states that if there is uncertainty in a potential financial estimate, a company should err on the side of caution and report the most conservative amount. This would mean that any uncertain or estimated expenses/losses should be recorded, but uncertain or estimated revenues/gains should not. This understates net income, therefore reducing profit. This gives stakeholders a more reliable view of the company’s financial position and does not overstate income.

Monetary Measurement Concept

In order to record a transaction, we need a system of monetary measurement , or a monetary unit by which to value the transaction. In the United States, this monetary unit is the US dollar. Without a dollar amount, it would be impossible to record information in the financial records. It also would leave stakeholders unable to make financial decisions, because there is no comparability measurement between companies. This concept ignores any change in the purchasing power of the dollar due to inflation.

Going Concern Assumption

The going concern assumption assumes a business will continue to operate in the foreseeable future. A common time frame might be twelve months. However, one should presume the business is doing well enough to continue operations unless there is evidence to the contrary. For example, a business might have certain expenses that are paid off (or reduced) over several time periods. If the business will stay operational in the foreseeable future, the company can continue to recognize these long-term expenses over several time periods. Some red flags that a business may no longer be a going concern are defaults on loans or a sequence of losses.

Time Period Assumption

The time period assumption states that a company can present useful information in shorter time periods, such as years, quarters, or months. The information is broken into time frames to make comparisons and evaluations easier. The information will be timely and current and will give a meaningful picture of how the company is operating.

For example, a school year is broken down into semesters or quarters. After each semester or quarter, your grade point average (GPA) is updated with new information on your performance in classes you completed. This gives you timely grading information with which to make decisions about your schooling.

A potential or existing investor wants timely i nformation by which to measure the performance of the company, and to help decide whether to invest. Because of the time period assumption, we need to be sure to recognize revenues and expenses in the proper period. This might mean allocating costs over more than one accounting or reporting period.

The use of the principles, assumptions, and concepts in relation to the preparation of financial statements is better understood when looking at the full accounting cycle and its relation to the detailed process required to record business activities ( Figure 3.2 ).

Concepts In Practice

Tax cuts and jobs act.

In 2017, the US government enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. As a result, financial stakeholders needed to resolve several issues surrounding the standards from GAAP principles and the FASB. The issues were as follows: “Current Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requires that deferred tax liabilities and assets be adjusted for the effect of a change in tax laws or rates,” and “implementation issues related to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and income tax reporting.” 4

In response, the FASB issued updated guidance on both issues. You can explore these revised guidelines at the FASB website (https://www.fasb.org/taxcutsjobsact#section_1).

The Accounting Equation

Introduction to Financial Statements briefly discussed the accounting equation, which is important to the study of accounting because it shows what the organization owns and the sources of (or claims against) those resources. The accounting equation is expressed as follows:

Recall that the accounting equation can be thought of from a “sources and claims” perspective; that is, the assets (items owned by the organization) were obtained by incurring liabilities or were provided by owners. Stated differently, everything a company owns must equal everything the company owes to creditors (lenders) and owners (individuals for sole proprietors or stockholders for companies or corporations).

In our example in Why It Matters , we used an individual owner, Mark Summers, for the Supreme Cleaners discussion to simplify our example. Individual owners are sole proprietors in legal terms. This distinction becomes significant in such areas as legal liability and tax compliance. For sole proprietors, the owner’s interest is labeled “owner’s equity.”

In Introduction to Financial Statements , we addressed the owner’s value in the firm as capital or owner’s equity . This assumed that the business is a sole proprietorship. However, for the rest of the text we switch the structure of the business to a corporation, and instead of owner’s equity, we begin using stockholder’s equity , which includes account titles such as common stock and retained earnings to represent the owners’ interests. The primary reason for this distinction is that the typical company can have several to thousands of owners, and the financial statements for corporations require a greater amount of complexity.

As you also learned in Introduction to Financial Statements , the accounting equation represents the balance sheet and shows the relationship between assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity (for sole proprietorships/individuals) or common stock (for companies).

You may recall from mathematics courses that an equation must always be in balance. Therefore, we must ensure that the two sides of the accounting equation are always equal. We explore the components of the accounting equation in more detail shortly. First, we need to examine several underlying concepts that form the foundation for the accounting equation: the double-entry accounting system, debits and credits, and the “normal” balance for each account that is part of a formal accounting system.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping

The basic components of even the simplest accounting system are accounts and a general ledger . An account is a record showing increases and decreases to assets, liabilities, and equity—the basic components found in the accounting equation. As you know from Introduction to Financial Statements , each of these categories, in turn, includes many individual accounts, all of which a company maintains in its general ledger. A general ledger is a comprehensive listing of all of a company’s accounts with their individual balances.

Accounting is based on what we call a double-entry accounting system , which requires the following:

- Each time we record a transaction, we must record a change in at least two different accounts. Having two or more accounts change will allow us to keep the accounting equation in balance.

- Not only will at least two accounts change, but there must also be at least one debit and one credit side impacted.

- The sum of the debits must equal the sum of the credits for each transaction.

In order for companies to record the myriad of transactions they have each year, there is a need for a simple but detailed system. Journals are useful tools to meet this need.

Debits and Credits

Each account can be represented visually by splitting the account into left and right sides as shown. This graphic representation of a general ledger account is known as a T-account . The concept of the T-account was briefly mentioned in Introduction to Financial Statements and will be used later in this chapter to analyze transactions. A T-account is called a “T-account” because it looks like a “T,” as you can see with the T-account shown here.

A debit records financial information on the left side of each account. A credit records financial information on the right side of an account. One side of each account will increase and the other side will decrease. The ending account balance is found by calculating the difference between debits and credits for each account. You will often see the terms debit and credit represented in shorthand, written as DR or dr and CR or cr , respectively. Depending on the account type, the sides that increase and decrease may vary. We can illustrate each account type and its corresponding debit and credit effects in the form of an expanded accounting equation . You will learn more about the expanded accounting equation and use it to analyze transactions in Define and Describe the Expanded Accounting Equation and Its Relationship to Analyzing Transactions .

As we can see from this expanded accounting equation, Assets accounts increase on the debit side and decrease on the credit side. This is also true of Dividends and Expenses accounts. Liabilities increase on the credit side and decrease on the debit side. This is also true of Common Stock and Revenues accounts. This becomes easier to understand as you become familiar with the normal balance of an account.

Normal Balance of an Account

The normal balance is the expected balance each account type maintains, which is the side that increases. As assets and expenses increase on the debit side, their normal balance is a debit. Dividends paid to shareholders also have a normal balance that is a debit entry. Since liabilities, equity (such as common stock), and revenues increase with a credit, their “normal” balance is a credit. Table 3.1 shows the normal balances and increases for each account type.

| Type of account | Increases with | Normal balance |

|---|---|---|

| Asset | Debit | Debit |

| Liability | Credit | Credit |

| Common Stock | Credit | Credit |

| Dividends | Debit | Debit |

| Revenue | Credit | Credit |

| Expense | Debit | Debit |

When an account produces a balance that is contrary to what the expected normal balance of that account is, this account has an abnormal balance . Let’s consider the following example to better understand abnormal balances.

Let’s say there were a credit of $4,000 and a debit of $6,000 in the Accounts Payable account. Since Accounts Payable increases on the credit side, one would expect a normal balance on the credit side. However, the difference between the two figures in this case would be a debit balance of $2,000, which is an abnormal balance. This situation could possibly occur with an overpayment to a supplier or an error in recording.

We define an asset to be a resource that a company owns that has an economic value. We also know that the employment activities performed by an employee of a company are considered an expense, in this case a salary expense. In baseball, and other sports around the world, players’ contracts are consistently categorized as assets that lose value over time (they are amortized).

For example, the Texas Rangers list “Player rights contracts and signing bonuses-net” as an asset on its balance sheet. They decrease this asset’s value over time through a process called amortization . For tax purposes, players’ contracts are treated akin to office equipment even though expenses for player salaries and bonuses have already been recorded. This can be a point of contention for some who argue that an owner does not assume the lost value of a player’s contract, the player does. 5

- 1 Center for Audit Quality. Guide to Public Company Auditing . https://www.iasplus.com/en/binary/usa/aicpa/0905caqauditguide.pdf

- 2 Center for Audit Quality. Guide to Public Company Auditing . https://www.iasplus.com/en/binary/usa/aicpa/0905caqauditguide.pdf

- 3 Financial Accounting Standards Board. “The Conceptual Framework.” http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/BridgePage&cid=1176168367774

- 4 Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). “Accounting for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” https://www.fasb.org/taxcutsjobsact#section_1

- 5 Tommy Craggs. “MLB Confidential, Part 3: Texas Rangers.” Deadspin. August 24, 2010. https://deadspin.com/5619951/mlb-confidential-part-3-texas-rangers

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Authors: Mitchell Franklin, Patty Graybeal, Dixon Cooper

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Accounting, Volume 1: Financial Accounting

- Publication date: Apr 11, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/3-1-describe-principles-assumptions-and-concepts-of-accounting-and-their-relationship-to-financial-statements

© Jul 16, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

A Beginner’s Guide to Hypothesis Testing in Business

- 30 Mar 2021

Becoming a more data-driven decision-maker can bring several benefits to your organization, enabling you to identify new opportunities to pursue and threats to abate. Rather than allowing subjective thinking to guide your business strategy, backing your decisions with data can empower your company to become more innovative and, ultimately, profitable.

If you’re new to data-driven decision-making, you might be wondering how data translates into business strategy. The answer lies in generating a hypothesis and verifying or rejecting it based on what various forms of data tell you.

Below is a look at hypothesis testing and the role it plays in helping businesses become more data-driven.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Hypothesis Testing?

To understand what hypothesis testing is, it’s important first to understand what a hypothesis is.

A hypothesis or hypothesis statement seeks to explain why something has happened, or what might happen, under certain conditions. It can also be used to understand how different variables relate to each other. Hypotheses are often written as if-then statements; for example, “If this happens, then this will happen.”

Hypothesis testing , then, is a statistical means of testing an assumption stated in a hypothesis. While the specific methodology leveraged depends on the nature of the hypothesis and data available, hypothesis testing typically uses sample data to extrapolate insights about a larger population.

Hypothesis Testing in Business

When it comes to data-driven decision-making, there’s a certain amount of risk that can mislead a professional. This could be due to flawed thinking or observations, incomplete or inaccurate data , or the presence of unknown variables. The danger in this is that, if major strategic decisions are made based on flawed insights, it can lead to wasted resources, missed opportunities, and catastrophic outcomes.

The real value of hypothesis testing in business is that it allows professionals to test their theories and assumptions before putting them into action. This essentially allows an organization to verify its analysis is correct before committing resources to implement a broader strategy.

As one example, consider a company that wishes to launch a new marketing campaign to revitalize sales during a slow period. Doing so could be an incredibly expensive endeavor, depending on the campaign’s size and complexity. The company, therefore, may wish to test the campaign on a smaller scale to understand how it will perform.

In this example, the hypothesis that’s being tested would fall along the lines of: “If the company launches a new marketing campaign, then it will translate into an increase in sales.” It may even be possible to quantify how much of a lift in sales the company expects to see from the effort. Pending the results of the pilot campaign, the business would then know whether it makes sense to roll it out more broadly.

Related: 9 Fundamental Data Science Skills for Business Professionals

Key Considerations for Hypothesis Testing

1. alternative hypothesis and null hypothesis.

In hypothesis testing, the hypothesis that’s being tested is known as the alternative hypothesis . Often, it’s expressed as a correlation or statistical relationship between variables. The null hypothesis , on the other hand, is a statement that’s meant to show there’s no statistical relationship between the variables being tested. It’s typically the exact opposite of whatever is stated in the alternative hypothesis.

For example, consider a company’s leadership team that historically and reliably sees $12 million in monthly revenue. They want to understand if reducing the price of their services will attract more customers and, in turn, increase revenue.

In this case, the alternative hypothesis may take the form of a statement such as: “If we reduce the price of our flagship service by five percent, then we’ll see an increase in sales and realize revenues greater than $12 million in the next month.”

The null hypothesis, on the other hand, would indicate that revenues wouldn’t increase from the base of $12 million, or might even decrease.

Check out the video below about the difference between an alternative and a null hypothesis, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content.

2. Significance Level and P-Value

Statistically speaking, if you were to run the same scenario 100 times, you’d likely receive somewhat different results each time. If you were to plot these results in a distribution plot, you’d see the most likely outcome is at the tallest point in the graph, with less likely outcomes falling to the right and left of that point.

With this in mind, imagine you’ve completed your hypothesis test and have your results, which indicate there may be a correlation between the variables you were testing. To understand your results' significance, you’ll need to identify a p-value for the test, which helps note how confident you are in the test results.

In statistics, the p-value depicts the probability that, assuming the null hypothesis is correct, you might still observe results that are at least as extreme as the results of your hypothesis test. The smaller the p-value, the more likely the alternative hypothesis is correct, and the greater the significance of your results.

3. One-Sided vs. Two-Sided Testing

When it’s time to test your hypothesis, it’s important to leverage the correct testing method. The two most common hypothesis testing methods are one-sided and two-sided tests , or one-tailed and two-tailed tests, respectively.

Typically, you’d leverage a one-sided test when you have a strong conviction about the direction of change you expect to see due to your hypothesis test. You’d leverage a two-sided test when you’re less confident in the direction of change.

4. Sampling

To perform hypothesis testing in the first place, you need to collect a sample of data to be analyzed. Depending on the question you’re seeking to answer or investigate, you might collect samples through surveys, observational studies, or experiments.

A survey involves asking a series of questions to a random population sample and recording self-reported responses.

Observational studies involve a researcher observing a sample population and collecting data as it occurs naturally, without intervention.

Finally, an experiment involves dividing a sample into multiple groups, one of which acts as the control group. For each non-control group, the variable being studied is manipulated to determine how the data collected differs from that of the control group.

Learn How to Perform Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a complex process involving different moving pieces that can allow an organization to effectively leverage its data and inform strategic decisions.

If you’re interested in better understanding hypothesis testing and the role it can play within your organization, one option is to complete a course that focuses on the process. Doing so can lay the statistical and analytical foundation you need to succeed.

Do you want to learn more about hypothesis testing? Explore Business Analytics —one of our online business essentials courses —and download our Beginner’s Guide to Data & Analytics .

About the Author

What is Hypothesis Testing?

Hypothesis testing steps, stating the null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis, what are type i and type ii errors, hypothesis testing example, more resources, hypothesis testing.

A statistical test to support your hypothesis

Hypothesis Testing is a method of statistical inference. It is used to test if a statement regarding a population parameter is statistically significant. Hypothesis testing is a powerful tool for testing the power of predictions.

A Financial Analyst , for example, might want to make a prediction of the mean value a customer would pay for her firm’s product. She can then formulate a hypothesis, for example, “The average value that customers will pay for my product is larger than $5.” To statistically test this question, the firm owner could use hypothesis testing. This example is further explored down below.

Hypothesis Testing is a critical part of the scientific method, which is a systematic approach to assessing theories through observation. A good theory is one that can make accurate predictions. For an analyst who makes predictions, hypothesis testing is a rigorous way of backing up his prediction with statistical analysis.

Here are the steps for hypothesis testing:

- State the null hypothesis ( H 0 ) and the alternative hypothesis ( H a ).

- Consider the statistical assumptions being made. Evaluate if these assumptions are coherent with the underlying population being evaluated. For example, is assuming the underlying distribution as a normal distribution sensible?

- Determine the appropriate probability distribution and select the appropriate test statistic.

- Select the significance level commonly denoted by the Greek letter alpha (α). This is the probability threshold for which the null hypothesis will be rejected.

- Based on the significance level and on the appropriate test, state the decision rule.

- Collect the observed sample data, and use it to calculate the test statistic.

- Based on your results, you should either reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis. This is known as the statistical decision.

- Consider any other economic issues that are applied to the problem. These are non-statistical considerations that need to be considered for a decision. For example, sometimes, societal cultural shifts lead to changes in consumer behavior. This must be taken into consideration in addition to the statistical decision for a final decision.

The Null Hypothesis is usually set as what we don’t want to be true. It is the hypothesis to be tested. Therefore, the Null Hypothesis is considered to be true until we have sufficient evidence to reject it. If we reject the null hypothesis, we are led to the alternative hypothesis.

Going back to our initial example of the business owner who is looking for some customer insight. Her null hypothesis would be:

H 0 : The average value customers are willing to pay for my product is smaller than or equal to $5

H 0 : µ ≤ 5

( µ = the population mean)

The alternative hypothesis would then be what we are evaluating, so, in this case, it would be:

H a : The average value customers are willing to pay for the product is greater than $5

H a : µ > 5

It is important to emphasize that the alternative hypothesis will only be considered if the sample data that we gather provide evidence for it.

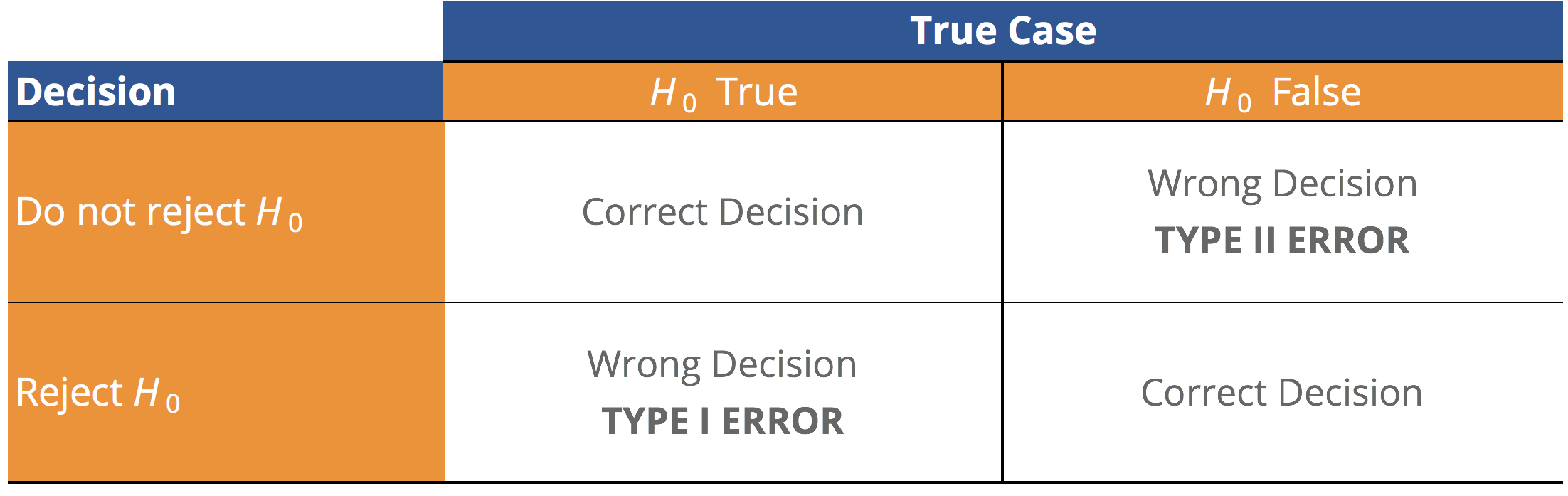

The binary nature of our decision, to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis, gives rise to two possible errors. The table below illustrates all of the possible outcomes. A Type I Error arises when a true Null Hypothesis is rejected . The probability of making a Type I Error is also known as the level of significance of the test, which is commonly referred to as alpha (α). So, for example, if a test that has its alpha set as 0.01, there is a 1% probability of rejecting a true null hypothesis or a 1% probability of making a Type I Error.

A Type II Error arises when you fail to reject a False Null Hypothesis . The probability of making a Type II Error is commonly denoted by the Greek letter beta (β). β is used to define the Power of a Test, which is the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis. The Power of a Test is defined as 1-β . A test with more Power is more desirable, as there is a lower probability of making a Type II Error. However, there is a tradeoff between the probability of making a Type I Error and the probability of making a Type II Error.

Let’s go back to the business owner example. Let us remember the question that we are trying to answer:

Q: “Will customers pay, on average, more than $5 for our product?”

1. We have set above both the null and alternative hypothesis

2. For this example, let us assume that the firm sells organic apple juice boxes. They are consumed by a wide range of consumers of all ages, income levels, and cultural backgrounds. So, given that our product is widely used by a diverse group of consumers, assuming a normal distribution is fair.

3. Let us assume that by getting samples from our consumers, we will manage to get over 100 observations. Given we are confident with our assumption of a normal distribution for the underlying population and have a large number of observations, we will use a z-test.

4. We want to be confident of our result, so let us pick our significance level as α = 5%. This will provide strong evidence of our result.

5. We are using a z-test with a significance level, and the null hypothesis is µ ≤ 5, so our rejection point will be z 0.05 =1.645 . This means that if the z score calculated from our sample is greater than 1.645, we reject the null hypothesis.

6. Now assume that we have collected our data and that from our sample of 100 observations, the mean price that customers are willing to pay for our juices is $5.02 and that the sample standard deviation was $0.10 . We can now calculate the z-score for our sample where we get a value of 2 given by [(5.02 – 5) / ( 0.1/ √ 100)].

7. Given our calculated z is greater than z 0.05 =1.645, we have strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis at a 5% significance level. We are then in favor of the alternative hypothesis that t he average value customers are willing to pay for the product is greater than $5.

8. We now need to take into consideration any economic or qualitative issues that are not addressed through the statistical process. These are usually non-quantifiable variables that have to be addressed when making a decision based on the findings. For example, if the biggest competitor was going to lower the price of the competing product significantly, that may lower the average value consumers are willing to pay for your product.

If you want to learn more about topics related to Hypothesis Testing, check out resources on the Royal Statistics Society website . To keep learning and advancing your career, the following CFI resources will also be helpful:

- Delphi Method

- Cointegration

- Durbin Watson Statistic

- Fibonacci Numbers

- AVERAGE Excel Function

- See all data science resources

- Share this article

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in

|

| | | | | | | | |

|

|

Positive Accounting Theory (PAT)

- Part 11.1 - Summary of Qualitative Characteristics of GENERALLY ACCEPTED ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES (GAAP)

- Part 11.2 - How and When to Recognize Revenues & Expenses in Accrual Accounting

- Part 11.3 - Functions in the Purchasing Process and how to Segregate Purchasing Duties

- Part 11.4 - Three Steps to Determining and Applying Materiality

- Part 11.5 - Assertions of Management about Economic Events in the Business

- Part 11.6 - Bank Accounting - Types of Bank Accounts, Cash Receipts & Disbursements, Disclosures Required for Cash Accounting

- Part 11.7 - Objectives of Internal Controls set by Management

- Part 11.8 - How to Test Internal Controls of an Organization

- Part 11.9 - Positive Accounting Theory (PAT)

- Part 11.11 - Accounting Information - Complex Commodity & Information Asymmetry

Positive Accounting Theory tries to make good predictions of real world events and translate them to accounting transactions. While normative theories tend to recommend what should be done, Positive Theories try to explain and predict

o Actions such as which accounting policies firms will choose o How firms will react to newly proposed accounting standards

• Its overall intention is to understand and predict the choice of accounting policies across differing firms. It recognizes that economic consequences exist.

• Under PAT, firms want to maximize their prospects for survival, so they organize themselves efficiently.

• Firms are viewed as the accumulation of the contracts they have entered into.

• In relation to PAT, because there is a need to be efficient, the firm will want to minimize costs associated with contracts. Examples of contract costs are negotiation, renegotiation, and monitoring costs. Contract costs involve accounting variables as contracts can be stipulated in terms of accounting information such as net income, and financial ratios.

• The firm will choose the accounting policies that best acknowledge the need for minimization of contract costs.

• PAT recognizes that changing circumstances require managers to have flexibility in choosing accounting policies. • This brings forward the problem of “opportunistic behavior”. This occurs when the actions of management are to better their own personal interests.

• With this in mind, the optimal set of accounting policies are described as a compromise between fixing accounting policies to minimize contract costs and providing flexibility in times of changing circumstances (considering the effects of opportunistic behavior).

The Three Hypotheses of Positive Accounting Theory

Positive Accounting Theory has three hypotheses around which its predictions are organized.

1. Bonus plan hypothesis

• Managers of firms with bonus plans are more likely to choose accounting procedures that shift reported earnings from future periods to the current period. By doing so, they can increase their bonuses for the current year.

2. Debt covenant hypothesis

• The closer a firm is to violating accounting-based debt covenants, the more likely the firm manager is to select accounting procedures that shift reported earnings from future periods to the current period.

• By increasing current earnings, the company is less likely to violate debt covenants, and management has minimized its constraints in running the company

3. Political cost hypothesis

• The greater the political costs faced by the firm, the more likely the manager is to choose accounting procedures that defer reported earnings from current to future periods.

• High profitability can lead to increased political “heat”, and can lead to new taxes or regulations esp. for large firms which may be held to higher reporting standards

How to Achieve Positive Accounting Theory

• Changing accounting policies • Managing discretionary accruals • Timing of adoption of new accounting standards • Changing real variables--R&D, advertising, repairs & maintenance • SPEs (Enron), capitalize operating expenses (WorldCom)

| |

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Accounting and Corporate Reporting - Today and Tomorrow

Accounting Choices in Corporate Financial Reporting: A Literature Review of Positive Accounting Theory

Submitted: 22 December 2016 Reviewed: 03 April 2017 Published: 20 September 2017

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.68962

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Accounting and Corporate Reporting - Today and Tomorrow

Edited by Soner Gokten

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

6,440 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

This chapter aims to put light on the positive accounting theory and related empirical studies and identify its broad contributions to the accounting research. Our objective is to provide a review of positive accounting literature in order to synthesize findings, identify areas of controversy in the literature, and evaluate critiques. Positive research in accounting started coming to prominence around the mid-1960s and had been a vector of paradigm shift within the financial accounting research in the 1970s and 1980s. The positive accounting theory is developed by Watts and Zimmerman and is based on work undertaken in economics and is heavily dependent on the efficient market hypothesis, the capital assets pricing model, and agency theory. The three key hypotheses are bonus plan hypothesis, debt hypothesis, and political cost hypothesis. Nevertheless, PAT has been subjected to severe and numerous criticisms from different perspectives, which are critiques on research methods, its theoretical foundations, its logic on economics' basis, and its reference to philosophy of science. PAT and its hypotheses will continue to be a rich field of empirical research and the basic questions that it raises are still relevant today.

- positive accounting theory

- accounting choice

- management compensation hypothesis

- debt hypothesis

- political cost hypothesis

Author Information

İdil kaya *.

- Galatasaray University, Istanbul, Turkey

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

Academic studies on the factors that affect a firm's accounting choices triggered a paradigm change in accounting research, altering the nature of literature from prescriptive to predictive. The construct of the new paradigm was first articulated by Ross Watts and Jerold Zimmerman with the publication of their revolutionary articles in the Accounting Review —“Towards a Positive Theory of the Determination of Accounting Standards” in 1978 and “The Demand for and Supply of Accounting Theories: The Market for Excuses” in 1979.

The term “Positive Accounting Theory” has come to practise to refer to the accounting theory developed and named by Watts and Zimmerman. The authors seek to appreciate and explain the concept of economic consequences of the interests of managers and financial accounting and reporting. In other words, their major aim is to explain and predict why managers and accountants choose particular accounting methods in preference to others. Furthermore, they assert that firm's attributes, such as leverage and size, are predictive variables of the firm's accounting choice.

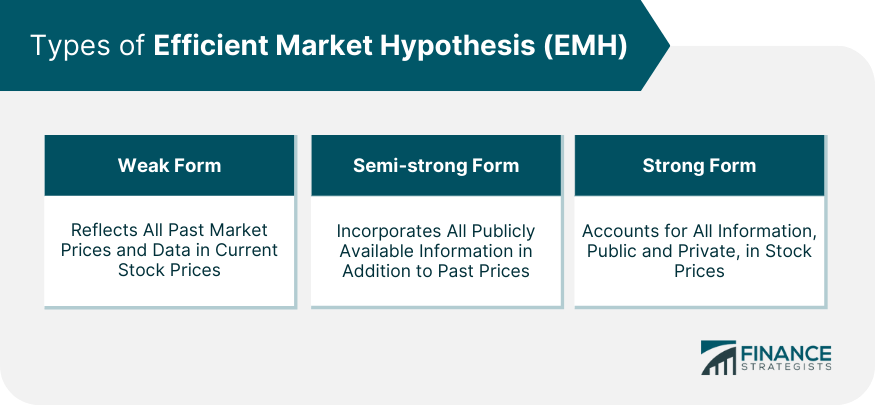

In fact, positive research in accounting started coming to prominence around the mid-1960s and had been a vector of paradigm shift within the financial accounting research in the 1970s and 1980s. The term “positive” refers to the theory that attempts to explain and make good predictions of particular phenomena. The positive accounting theory (PAT) relied in great part on work undertaken in economics and was heavily reliant on the efficient market hypothesis, the capital assets pricing model, and agency theory.

PAT has led to a large amount of empirical studies. Positive researchers empirically test their predictions around the bonus plan hypothesis, the debt covenant hypothesis, and the political cost hypothesis. These hypotheses can be used in two distinguished forms of positive accounting theory. The first form is the opportunistic form asserting that managers in electing accounting procedures react to maximize the wealth, and the second form is the efficiency form for good corporate governance.

PAT has been subjected to severe and numerous criticisms from different perspectives, which are critiques on research method, economics base, and reference to philosophy of science. It is said that PAT seeks to predict and explain why managers choose to adopt particular accounting methods in preference to others but says nothing as to which method a firm should use.

We believe that PAT and its hypotheses will continue to be a rich field of empirical research and the basic questions that it raises are still relevant today. This chapter aims to put light on the PAT and related empirical studies and identify its broad contributions to the accounting research. Our objective is to provide a review of extant literature in order to synthesize findings, identify areas of controversy in the literature, and evaluate critiques.

Our literature review is organized around ideas of PAT, its hypotheses, supporters and followers, and finally critiques of this theory. The remaining part of this chapter proceeds as follows: We first examine the forces that give rise to this theory. We then investigate its foundations using the works of Watts and Zimmerman. We describe how empirical studies added unique insights into its development. Some criticisms are evaluated. Finally, we outline and discuss the significant contribution of PAT to our understanding of corporate reporting practices. We conclude that this theory has generated several useful insights on managers' reporting decisions.

2. The paradigm change in accounting research: the origins of positive accounting theory

In this section, we examine the forces and the publications that had a major impact on the emergence of PAT. This theory is based on work undertaken in economics and is heavily dependent on the efficient market hypothesis, the capital assets pricing model, and agency theory.

Positive research began in early 1960s and opened a new era in accounting literature, using economic models and statistical processing in empirical studies. The first serious discussions and analyses of positive research on accounting emerged in late 1960s with the pioneering studies of Ball and Brown [ 1 ] and Beaver [ 2 ]. These two seminal publications provide significant evidence of the information content in accounting earnings announcements, i.e., the earnings reflect some of the information in security prices. They gave rise to a huge literature of capital markets research [ 3 ].

A significant number of academic publications investigated the determinants of the shift in paradigm from narrative to positive research. Major findings offered by these studies are as follows.

Research methodologies have been developed based on the “hypothesis formulating and testing” [ 4 , 5 ].

With the emergence of computers, large new databases of financial information would be readily accessible for researchers [ 4 , 6 ].

The concept of “economic consequences” has been investigated. This concept is defined by Zeff as “the impact of accounting reports on the decision-making behaviour of business, governments, and creditors” [ 7 , 8 ].

New academic journals have been established and they adopt the selection policy of empirical researches [ 9 ].

The development of behavioural science enabled to analyse managers' accounting choices [ 6 , 9 ].

Generous research grants have been provided to new generation of accounting researchers that applied empirical research methods [ 9 ].

It is said that two reports on US business education were the impetus for those changes [ 4 , 5 ]. In 1959, R.A. Gordon and James E. Howell published “Higher education for business” and Franck C. Pierson published “The education of American Business men”. The former report was commissioned by Ford Foundation and the latter by Carnegie Foundation. Besides their recommendations on teaching methods, these authors stressed the need to develop research based on the formulation and testing of the hypotheses. They also describe the resources necessary to advance the level of business studies.

Another significant explanation of the PAT's development is the strong influence of several academic works on positive economic theory, efficient markets hypothesis, CAPM, agency theory, and capital markets researches ( Table 1 ). Watts and Zimmerman aimed to develop an economic-based accounting theory and they advance an empirical methodology that focus on economics-based explanations and predictions of accounting practice. Boland and Gordon assert that this economic-based accounting theory is a combination of Milton Friedman's instrumentalism and Paul Samuelson's positivism [ 15 ]. They also add that Watts and Zimmerman practise the methodology as that of the Chicago School economists [ 6 , 15 ].

| Authors | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Friedman [ ] | Friedman (1953) described positive science in economics. |

| Fama [ ] | He introduced and subsequently made major contribution to the efficient markets hypothesis. |

| Sharpe [ ] and Lintner [ ] | They developed the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). |

| Ball and Brown [ ] | They found significantly positive correlation between the sign of the abnormal stock return and the sign of the earnings change over the firm's previous year's earnings. |

| Beaver [ ] | The author examined the variability of stock returns and trading volume around earnings announcements. He found that the flow of info increase in the earnings announcement periods. |

| Jensen and Merckling [ ] | The authors investigated managerial behaviour, agency costs, and ownership structure in the context of the firm. |

Table 1.

Academic literatures that were the impetus for PAT.

In 1976, the publication of Jensen and Merckling's article on agency theory had a major impact on PAT [ 14 ]. In agency theory, the firm is analysed as “a nexus of contracts” and this concept is accepted by positive accounting research. The contracts are produced with the aim of guarantee that all parties, acting in their own self-interest, are at the same time motivated towards maximizing the firm's value. PAT accentuates the function of accounting in reducing agency costs and its essential role in an efficient corporate governance structure [ 4 ].

3. The development of positive accounting theory

In this section, we examine the development of the PAT, the contribution of major works of Watts and Zimmerman, and the hypotheses of this theory.

The construct of PAT was first articulated by Watts and Zimmerman and popularized in their book: positive accounting theory [ 6 , 16 ]. Table 2 shows major works of Watts and Zimmerman in this issue. They adopted the label “positive” from the economics to distinguish accounting research aimed at understanding accounting from research directed at generating prescriptions. They investigated the role of accounting theory in determining accounting practice and build a theory intending to be a positive theory (Watts & Zimmerman, p. 274) [ 5 ], i.e.,

“a theory capable of explaining the factors determining the extant accounting literature, predicting how research will change as the underlying factors change, and explaining the role of theories in the determination of accounting standards. It is not normative or prescriptive”.

| Authors | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Watts and Zimmerman [ ] | This pioneering article outlined many of the problems posed by regulatory capture. The authors announce that ultimately, they seek to develop a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. They believe that management plays a central role in the determination of standards. They examine factors affecting management wealth which are taxes, political costs, regulation, information production and management compensation plans. They find that the political cost factor is important in affecting management’s attitude. |

| Watts and Zimmerman [ ] | This paper analyses; |

| Watts and Zimmerman [ ] | This book is written and used for second year M.B.A and Ph.D. audience. Authors review the theory and methodology of the economic-based literature in accounting. EMH and CAPM are explained. The important role of EMH in accounting research is emphasized. CAPM is used as the valuation method. The methodologies of the empirical studies in the development of the literature are explained. Analyses end syntheses are provided on the different issues. These are forecasting earnings, contracting process, compensation plans, debt contracts, political process, empirical tests of accounting choice, stock price tests of the theory, and the theory's application to auditing. |

| Watts and Zimmerman [ ] | This paper examines and evaluated the evolution and state of PAT and criticisms of positive accounting research. The authors responded to most of the published critiques on issues relating to research method and philosophy of science. Opportunistic and efficiency perspectives of PAT are distinguished. |

Table 2.

Major works of Watts and Zimmerman.

Watts and Zimmerman reviewed the theory and methodology of the economic-based literature in accounting in their prominent book dated 1986 [ 6 ]. In this book written and used for second year M.B.A and Ph.D. audience, the authors point the important role of efficient market hypothesis in accounting research; they use CAPM as the valuation method. They explain the methodology of the empirical studies in the development of the literature. They also provide analyses end syntheses on forecasting earnings, contracting process, compensation plans, debt contracts, political process, empirical tests of accounting choice, stock price tests of the theory, and the theory's application to auditing [ 6 ].

According to Watts and Zimmerman, the “property rights” theory adopted by positive accounting researchers assumes that the firm is a nexus of contracts between self-interested individuals. PAT highlighted the importance of contracting costs, including information, agency, bankruptcy, and lobbying costs [ 5 , 6 ].

In 1990, after more than a decade since the publication of 1978 and 1979 articles, the authors examined and evaluated the evolution and state of PAT and criticisms of positive accounting research in their article “Positive Accounting Theory: A Ten Year Perspective”, in the accounting review. They emphasized that their two pioneering papers contributed to a literature that has uncovered empirical regularities in accounting practice and they responded to most of the published critiques [ 5 ]. In evaluating the contribution of this article to the literature, Watts and Zimmerman asset that:

“The literature explains why accounting is used and provides a framework for predicting accounting choices. Choices are not made in terms of "better measurement" of some accounting construct, such as earnings. Choices are made in terms of individual objectives and the effects of accounting methods on the achievement of those objectives”.

Watts and Zimmerman identified three essential hypotheses. These are bonus plan hypothesis (or management compensation hypothesis), the debt/equity hypothesis (or debt hypothesis), and political cost hypothesis [ 5 ]. According to management compensation hypothesis, managers with bonus plans anchored to earnings are more likely to adopt accounting methods that increase current period's reported income. The debt hypothesis predicts that the higher the firm's debt/equity ratio, the more likely managers use accounting methods that increase earnings. As far as political costs hypothesis is concerned, it is assumed that if managers are under political scrutiny, they are likely to adopt accounting methods that reduce reported income [ 4 ].

4. Literature relating to the PAT

In this section, we examine the PAT literature. A considerable amount of literature has been published on PAT. Numerous empirical studies tested its hypotheses, provided important evidence, and contributed to the theory.

PAT literature focuses on management's motives for financial reporting choices, using economic models and statistical processing, when there are agency costs and information asymmetry. It attempts to explain and predict firm accounting choices as a part of the firm's overall need to minimize its cost of capital and other contracting costs, applying methods and techniques from economics. Opportunistic attitudes and behaviours of managers and their impacts on accounting policy choices have been investigated widely in positive research and this led to a rich body of empirical studies on earnings management. A wide range of the literature incorporates both ex ante contracting efficiency incentives with ex post redistributive effects. The methodology of this literature is the methodology of economics, finance, and science generally [ 5 ]. Table 3 provides an overview of these empirical researches and their research area.

| Authors | Research area |

|---|---|

| Ball, Kothari and Watts [ ] | Determinants of the relationship between earnings changes and stock return. |

| Beattie [ ] | Relationship between extraordinary items and income smoothing. |

| Christie [ ] | Cross-sectional analysis. |

| Christie [ ] | Evidence on contracting and size hypotheses. |

| De Angelo [ ] | Study of the accounting numbers as market value substitutes in managerial buyouts of public stockholders. |

| Dechow [ ] | The role of accounting accruals in earnings and cash flows. |

| Dechow and Sloan [ ] | Executive incentives and the horizon problem. |

| Dechow, Sloan and Sweeney [ ] | Detection of earnings management. |

| Dechow, Kothari and Watts [ ] | The relation between earnings and cash flows. |

| Dechow, Ge and Schrand [ ] | Proxies in earnings quality. |

| Healy [ ] | The effect of bonus schemes on accounting decisions. Description of “taking a bath” or Big Bath concept. |

| Healy and Palepu [ ] | Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets. |

| Kothari [ ] | Review of capital markets research in accounting. |

| Lys and Sohn [ ] | The association between revisions of financial analysts' earnings forecasts and security price changes. |

| Nagar, Nanda and Wysocki [ ] | Discretionary disclosure and stock-based incentives. |

| Sweeney [ ] | Debt-covenant violations and managers. |

| Verrecchia [ ] | Discretionary disclosure. |

| Zang [ ] | The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lenders and borrowers. |

Table 3.

Literature constructed on the PAT.

Beattie et al. state that this literature implicitly assumes that the market is inefficient and relies on bottom line accounting numbers and does not show interest in methods used to produce them [ 18 ]. According to Healy and Palepu (p. 419) [ 19 ],

”Empirical studies of positive accounting studies test whether managers make accounting method changes or accrual estimates to reduce the costs of violating bond covenants written in terms of accounting numbers, to increase the value of earnings-based bonuses under compensation contracts, or to reduce the likelihood of implicit or explicit taxes”.

On the other hand, Healy and Palepu assert that PAT studies generated several interesting empirical regularities regarding management accounting choice but there is ambiguity on the interpretation of this evidence [ 19 ].

5. Criticisms from different perspectives

In this section, we summarize and analyse the literature having critical comments on PAT. The literature developed since the first publication of Watts and Zimmerman articles in 1978.

PAT has been subject to a continuous and endless stream of criticisms since it first emerged in late 1970s. The critiques are from different perspectives. These are critiques related to its theoretical foundations, its logic on economics' basis, its research methods, and critiques on its reference to philosophy of science [ 15 , 35 ]. It has been defended that this theory is scientifically wrong and its predictions do not always hold. Christenson (p. 18) asserts that [ 36 ]:

“By arguing that their theories admit exceptions, Watts and Zimmerman condemn them as insignificant and useless”.

In an examination of PAT methodology with a critical look, Christenson argues that he prefers to use the name “the Rochester School” referring to authors' affiliation instead of PAT [ 36 ]. Furthermore, he asserts that this discipline should be denominated “sociology of accounting” since it is about describing, predicting, and explaining the behaviours of managers and accountants. Table 4 presents an overview of some criticisms.

| Authors | Critiques |

|---|---|

| Boland and Gordon [ ] | The authors examined economics-based critiques and those based on philosophy of science. They conclude that critiques on philosophy of science may not be very effective but the critiques on the limitations of equilibrium-based economic analysis are valid. |