Your browser is outdated. To ensure the best experience, update to the latest version of your preferred browser. Update

Become a Member!

- Customizable Worksheets

- Interactive Therapy Tools

- No More Ads

- Support Therapist Aid

Filter by demographic

Filter by topic

No results found :(

You can change or remove a filter, or select a different content type.

Select a content type to begin browsing

demographic

Your account has been created.

Would you like to explore more features?

Recommended

Professional

Customizable and fillable worksheets.

Unlimited access to interactive therapy tools.

Support the creation of new tools for the entire mental health community.

Ad-free browsing.

- Effective Drug Education Tools

- What Teachers & Educators Say

- The Truth About Drugs Education Package Content

- Educator’s Guide Downloads

- Law Enforcement Professionals

- Drug Prevention Specialists

- Prevention Activities

- Youth Pledge

- Adult Pledge

EDUCATOR’S GUIDE DOWNLOADS

The Truth About Drugs Educator's Guide (PDF)

Additional Projects and Activities

Adult Drug-Free Pledge (Black & White)

Adult Drug-Free Pledge (Color)

Assignment Sheet Lesson 17

Class Assignment—Lesson 3

Educator’s Questionnaire

Examination—Lessons 1–17

Glossary of Terms

Homework Assignment—Lesson 1

Homework Assignment—Lessons 5–16

Post Program Student Questionnaire

Post Program Survey

Pre-Program Student Questionnaire

Student Certificate (Black & White)

Student Certificate (Color)

Success Form (Black & White)

Success Form (Color)

Understanding Drugs Assignment Sheet

Youth Drug-Free Pledge (Large Format—Black & White)

Youth Drug-Free Pledge (Large Format—Color)

Youth Drug-Free Pledge (Small Format—Black & White)

Youth Drug-Free Pledge (Small Format—Color)

Download more Truth About Drugs materials.

GET INVOLVED

Learn the Truth About Drugs, enroll in the free online courses.

JOIN A TEAM

There are Drug-Free World Chapters all over the world. To join a local chapter or start your own, contact us.

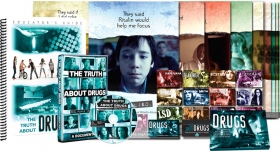

The Truth About Drugs Education Package contains practical tools to educate young people about substance abuse.

Sign up for news and updates from the Foundation!

Thank you for subscribing.

Connect with us!

DRUG EDUCATION

Foundation support.

The Foundation for a Drug-Free World is a nonprofit, international drug education program proudly sponsored by the Church of Scientology and Scientologists all over the world. To learn more, click here.

Your download will begin shortly.

Subscribe to The Truth About Drugs News and get our latest news and updates in your inbox.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

www.rcmp.gc.ca

Common menu bar links

- Français

Home > Centre for Youth Crime Prevention > Drugs and Alcohol > Drugs: Use, Abuse and Addiction - Lesson Plan (Grades 9 & 10)

Institutional links

Centre for youth crime prevention, get involved.

- National Youth Advisory Committee

- Leave the phone alone

- Youth leadership workshops

Topic pages

- Bullying and cyberbullying

- Impaired driving

- Distracted driving

- Drugs and alcohol

- Online safety

- Youth engagement

Lesson plans

National rcmp.

- About the RCMP

- Publications

- Family Corner

Navigate by

- A-Z site index

- Proactive Disclosure

- Acts and Regulations

Drugs: Use, Abuse and Addiction - Lesson Plan (Grades 9 & 10)

Note: Contact us by e-mail to receive the Lesson Plan PDF version. Requests will be answered between 7:00am and 3:00pm, Monday to Friday.

Objectives:

- To learn about various drugs.

- To identify risk factors and protective factors associated with substance abuse (drugs and alcohol).

- To discuss what addiction is and the consequences of it.

- To determine behaviours that increase well-being and allow students to achieve life goals.

- Activity #1: Name that Drug (9-10.1 Handout)

- Activity #5: Now, it's Your Choice (9-10.5 Handout)

Reference documents are found at the end of this lesson plan.

Activity #1: name that drug (9-10.1 reference), activity #2: recognizing the risks (9-10.2 reference).

- Activity #3: Path to Addiction (9-10.3 Reference)

Activity #4: Consequences of Addiction (9-10.4 Reference)

Other materials:.

- SMART board/chalk board to summarize responses on

- Chart paper and markers for groups to use

- Computer/projector to display slides (optional)

- Masking tape

- Introduction: 5 minutes

- Activity #1: Name that Drug 10 minutes

- Activity #2: Recognizing the Risks 15 minutes

- Activity #3: Scale of Addiction Use 10 minutes

- Activity #4: Consequences of Addiction 15 minutes

- Activity #5: Now, it's Your Choice 5 minutes

- Conclusion 5 minutes

Total: 60 minutes

Presenter Preparation:

- Review the Drugs and Alcohol section of the Centre for Youth Crime Prevention.

- Review the Objectives of this lesson plan.

- Identify ways in which you are personally linked to the subject matter. This presentation is general in nature, and will be more effective if you tailor it to your personal experiences, the audience and your community.

- Guest speakers can really have an impact. If there is someone in your community who has been impacted by substance abuse, invite them to speak with the youth. You may also want to consider inviting an RCMP member from the drug section. Please note: Activities will need to be removed or modified to ensure that the time allotment is respected.

- Print the lesson plan and reference documents.

- Print required handouts. Make a few extra copies just to be sure.

- Ensure your location has any technology you require (computer, projector, SMART board, etc.)

A) Introduction

- Introduce yourself.

- Tell the students about your job and why you are there to talk to them. Tell students that in today's class, they will talk about substance abuse, its impacts and ways they can deal with peer pressure related to substance use and abuse. Additionally, different supports to help them deal with the issue will be addressed.

- If you are a police officer, briefly discuss the role of police officers when it comes to substance abuse (i.e. your experience dealing with youth and substance abuse issues).

- Pass out one index card to each student. Explain that this card is to be used for students to write down any question they may have. The presenters will collect them towards the end of the presentation and answer the questions anonymously in front of the group.

B) Activity #1: Name that Drug

Goal: Students will learn about various drugs (including short and long-term health impacts). Type: Information chart and discussion Time: 10 minutes

- Cut out the drug types and their matching definitions from Activity #1: Name that Drug (9-10.1 Reference) and place them out of order on the board.

- Explain to students that different types of drugs have different effects on our bodies.

- Stimulants: Drugs that make the user hyper and alert.

- Depressants: Drugs that cause a user's body and mind to slow down.

- Hallucinogens: Drugs that disrupt a user's perception of reality and cause them to imagine experiences and objects that seem real.

- Ask students to match up the fact with the drug as a class. Go over the answers.

- Ask the students to read over the handout Activity #1: Name that Drug (9-10.1 Handout) and start a discussion based on what the students read. Encourage all students to participate to the discussion by asking questions, such as: "What is a drug?" "What do drugs do?" "What happens when a person uses drugs?" "What are drugs used for?" "Do drugs affect everyone in the same way?" "Can drugs be prescribed by a doctor?"

C) Activity #2: Recognizing the Risks

Goal: Students will recognize protective and risk factors associated with substance abuse and addiction and learn the importance of resilient factors. Type: T-chart and group activity Time: 15 minutes Step #1:

- Resiliency: The ability to become strong, healthy and successful after something bad happens to you ( www.merriam-webster.com 2014).

- Risk Factors: Factors that can lead to drug use.

- Protective Factors: Factors that can shield from drug use.( http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/docas-ssdco/guide-kid-enf/page3-eng.htm ).

- Ask the students to get into groups of 3 or 4.

- Create a chart on the SMART board, chalkboard or overhead with two titles: (1) Risk Factors & (2) Protective Factors . Ask students to identify examples of risk factors when it comes to substance abuse, alcohol and addiction and record their answers. Then ask students to identify some examples of protective factors that could be associated with not using drugs and alcohol or getting addicted. Use Activity #2: Recognizing the Risks (9-10.2 Reference) as a guide.

- If time allows, give each group playing cards and tell them to work together to make a card house for 5 minutes.

- Explain that in this activity, each card represents a protective and resilience factor, and when those factors fail or diminish the structure will fall.

D) Activity #3: Path to Addiction

Goal: Students will discuss how addiction can impact a person's lifestyle. Type: Discussion and group activity Time: 10 minutes

- Ask students to define what addiction is as well as the substances a person can become addicted to.

- Make sure to include that both drugs and alcohol can be addictive.

- Explain to students that addiction is an ongoing process. Addiction may present its challenges at different times over many years in a user's life.

- Write each stage on a different piece of paper. Ask for 5 volunteers to come to the front of the class and give each student a stage.

- Have the student volunteers work together to arrange themselves in the order that they think the scale of addiction occurs in.

- With the students, define each stage of addiction. Discuss the answers with students and use Activity #3: Path to Addiction (9-10.3 Reference) as a guide.

E) Activity #4: Consequences of Addiction

Goal: Students will examine the consequences of addiction on all facets of life. Type: 5 corners activity and group discussion Time: 10 minutes

- Separate the students into 5 different groups.

- Have the students get into their groups and give each group a piece of chart paper. Assign each of the five groups one of the topics: (1) Family, (2) Friends & Recreation, (3) School & Jobs, (4) Physical & Emotional Health, and (5) Financial. Have each group write the topic on their piece of chart paper.

- Ask each group to brainstorm and record the consequences of an addiction relating to their topic.

- Give the groups 5 minutes to come up with a hashtag that represents how they might be affected in that aspect of their life.

- Discuss answers with the group.

F) Activity #5: Now, it's Your Choice

Goal: Students will commit to a healthy lifestyle Type: 5 corners activity and group discussion Time: 15 minutes

- Distribute Activity #5: Now, it's Your Choice (9-10.5 Handout) and ask the students to answer the question.

Step #2: (Homework)

- As part of their homework from the presentation, ask all the students to make the pledge to say no to drugs on the National Anti-Drug Strategy website: http://nationalantidrugstrategy.gc.ca/prevention/youth-jeunes/index.html and click on "Make a Pledge." Tell them to print the pledge they submitted and display them around the classroom or school.

G) Conclusion

- To conclude the lesson, summarize the important points and highlights of your discussion throughout the session.

- Collect all index cards from students. Take some time to answer any questions from the cards that the students may have had.

- Leave students with information about how to contact you if they have any follow up questions they didn't want to ask in class.

Reference documents

| Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| This drug may slow down mental reactions and impair short-term memory, and emits a strong odor with use. Impairment by this drug is different for every individual. | |

| This stimulant comes in powder, crystal, and rock form | |

| This man-made hallucinogen is created by mixing drugs and chemicals to mimic the effects of marijuana | |

| This hallucinogen has a range of effects including "pseudo-hallucinations" where you're aware that the images aren't real | |

| This depressant causes your skin to itch and a decreased reaction to pain | |

| This "natural" hallucinogen can cause you to mix up senses, for instance "hearing" colours or "seeing" sounds (source: ) | |

| This hallucinogen can cause you feel "out-of-body" or "near death" experiences | |

| Also known as MDMA, this drug is both a hallucinogen and a stimulant | |

| This hallucinogen can cause your mouth and teeth to decay (source: ) |

| Risk Factors | Protective Factors |

|---|---|

(Adapted from: Alberta Health Services www.albertahealthservices.ca/2677.asp )

Activity #3: Scale of Addiction Use (9-10.3 Reference)

| Level | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| No substance use. |

| Includes experimentation to see what it's like and recreational use also can occur. |

| Problems associated with using the substance begin to appear; or, the substance (such as medication) is not being used as it was originally intended. |

| Use is more frequent and obsessive behaviour starts. |

| Choice of use is no longer an option and has become a way of life. |

(Adapted from: Alberta Health Services http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/2677.asp )

| Personal Areas Affected | Consequences |

|---|---|

Family | |

Friends & Recreation | |

School & Job | |

Health – Physical & Emotional | |

Financial |

Drugs Research Project - Health Class Assignment - Drugs Info Poster or Pamphlet

What educators are saying

Description.

Drugs Research Project - Health Class Assignment - Drugs Info Poster or Pamphlet: This health project serves as an informative exploration of the dangers of drug use. Through comprehensive research, students research the harmful effects, addictive nature, and societal impacts of a specific drug. They compile their findings into a comprehensive poster or pamphlet, highlighting key information to raise awareness among their peers about the risks associated with drug use. By engaging in this health class project, students not only deepen their understanding of the subject but also contribute to promoting a healthier and safer community.

Included in This Drugs Research Project Health Assignment:

➡️ Drugs Research Project Assignment Page: Share this comprehensive assignment page detailing the drug research project where they will create a poster or pamphlet warning teens about the dangers of a specific drug. This assignment page includes:

- A designated website for research purposes,

- A curated list of drugs for students to choose from,

- Clear instructions outlining what to include on the poster or pamphlet, and

- Rubric requirements for student assessment and guidance.

➡️ Drugs Research Project Rubric: Streamline the assessment process with a user-friendly printable rubric. This tool ensures students understand the expectations of the project

What Teachers Are Saying About This Drugs Research Project Health Assignment:

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ I used this at the end of our drug unit. It was a good way to wrap up the unit. Students worked in pairs to complete this project.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ My students enjoyed working on this and learning about this topic. They had no idea about a lot of the information on drugs that they found out, and were totally shocked by some of it!

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ Easy to use. Engaging for middle schoolers to research drugs. Provided student choice.

If you like this, you'll also love these other health resources:

>>> The Dangers of Energy Drinks

>>> The Dangers of Smoking Cigarettes

>>> The Dangers of Drinking Alcohol

© Presto Plans

➡️ Want 10 free ELA resources sent to your inbox? Click here!

⭐️ Follow Presto Plans on TpT to see what's new and on sale .

Questions & Answers

Presto plans.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Creative Ways to Use Graphic Novels in the Classroom! 🎥

10 Conversation Starters To Spark Authentic Classroom Discussions About Drugs and Alcohol

It’s a difficult task, but an important one. Here are some powerful prompts to start the conversation.

I’m going to be honest with you. Talking to middle-school students about the risks of drugs and alcohol is not my favorite thing to do. It’s awkward. It’s challenging. I don’t know what they’re going to say. Frankly, it scares me a little. But here’s the thing. Not talking to my students about underage use and abuse of drugs and alcohol, and the many tough decisions they’re going to face as teenagers, scares me far more. Here’s why. The average age boys first try alcohol is 11. For girls, the age is 13. Research shows that teens who drink or use drugs regularly are 65 percent more likely to become addicted than those who hold off until age 21.

So, that’s why I talk to my students. I’m in. Even though it’s hard, even though they sometimes roll their eyes, I talk to them about drugs and alcohol because it matters, because it can help them make good choices, it can help to save lives, and because I believe teachers can make a difference. Genuine, ongoing conversations with adults who care—parents of course, but teachers too—can help teens make better decisions on the way to growing up.

Download these free conversation starter cards I use with my eighth graders. Over the last couple of years, I’ve tried different approaches. Sometimes, I have kids pull a question out of a hat, and we have a class-wide discussion. Other times, I divide a class into groups and give each group a question to chat about. Then, each group reports back to the whole class on their discussion. Below are my most successful “conversation starters” about teen drug and alcohol use, and some tips on how to guide the discussions that follow.

1. Have you been in situations where there were opportunities for drug or alcohol use? Did you feel pressured? Why or why not?

Let students share a few stories. Then guide them to think about peer (or other) pressure. Would they judge someone who says “no” to alcohol and drugs negatively? They will likely say they respect others’ choices, yet they still fear being judged themselves. This dichotomy is a great place to focus the conversation. Ask: “What are your options if you feel pressured?” For example, students can practice what they are going to say so that they feel more comfortable. Suggest they avoid the “pressure zone” or situations that might be uncomfortable. Use the buddy system. Perhaps they can find a friend who shares their values, and they can back each other up.

2. Why do you think some teens abuse drugs and alcohol? If you asked them, what reasons would they give for using? What other reasons might they have?

Some of the answers you can expect are: peer pressure, escapism, “because it’s fun,” curiosity, or rebellion. Push students to also consider reasons like self-medication, boredom, ignorance of the risks, fear of rejection, depression, recklessness. Ask: “What else can you do for fun or when you need an escape? Everybody needs that sometimes. What are some options besides drugs and alcohol?” (Hint: amusement parks, sports, trying something new like acting or skating.)

3. Imagine that it’s 25 years from now and you have a teenage son or daughter exactly the same age as you are now. What would you say to him or her about drinking and drugs?

You may receive a surprising range of answers to this question, but it will likely provoke an interesting discussion. Ask them to consider the choices about drugs and alcohol they would want a younger sibling or cousin to make. Are they different from the choices they make themselves or they intend to make themselves? Push your students to account for the difference. If they want the best for others, why not for themselves?

4. When you feel down, stressed, lonely or bored, what do you do to feel better? Sometimes people “medicate” with drugs or alcohol to avoid difficult feelings. What are some healthier options?

Your students should be able to come up with a list—everything from “Facetime a friend” to “go out for ice cream.” Afterwards, type up their list of suggestions to share as a handout at the next class .

5. It’s Friday night and you’ve been looking forward to hanging out with your friends all week. Your friend says he’ll give you a ride because he knows you’re stuck. You get there and it’s going great, but then you turn around and your ride is smoking a joint. What are your options? What would you do?

Your students will know that calling their parents is the accepted answer. If they don’t want to do that, what other options are there? Find a different ride, Uber, call a sibling or another adult they trust, walk home, spend the night. Talk to your students about the importance of thinking ahead and anticipating possible outcomes. What can they do to avoid these kinds of situations in the first place?

6. You are at a concert and someone offers you a pill to “enhance the experience.” If you were to take it, what are some of the possible consequences? If you chose not to take it, what would happen?

Encourage your class to list all the possible things that could happen after each choice. Appoint a student to record answers on the board. No doubt, one list will be far longer than the other. There are many negative consequences to taking a drug that they know nothing about. Talk to your students about impulse control and the teenage brain . The teen brain is primed to take risks This means that teens need to be extra aware as they make decisions.

7. Have you ever seen anyone using alcohol or drugs make a fool of themselves? What happened? How would you feel if it were you?

Every hand in the room will go up, and everyone will want to tell a story about the time their uncle fell off the porch into the baby pool. The tricky part here is reining it in, and helping them understand that it’s a lot less funny when the Snapchat video stars your own humiliation. Ask students: How would you feel if that was you? How can you avoid making decisions you regret the next day or perhaps even forever?

8. When do you think people are old enough to make their own decisions about drinking and drugs? Do grownups always make good decisions? If you were in charge of setting the legal age, what would it be?

Ask: Are there other reasons why it’s a good idea for teens to wait until they are 21 before they drink alcohol? What are they? For example, research shows that people who use drugs or alcohol regularly as teens are 68 percent more likely to become addicted than those who hold off use until age 21, after which the chances of addiction drop to 2%.

9. What can teens do to have a good time and to feel a rush of excitement other than doing drugs or drinking? In short, what else can teens be doing on a Saturday night?

Push your students to think beyond movies and concerts. How about indoor rock climbing, mountain biking, going to concerts, playing music, learning to cook, volunteering, filmmaking, cartooning, science experiments, political activism, fundraising, bodybuilding or camping? Encourage your students to see that they can be themselves, have great friends and a great time without resorting to drinking and drugs.

10. Name two things you would like to accomplish by the time you graduate high school. How could drugs and alcohol use get in the way of those goals?

For this question, ask five or so students to share goals, and then have the rest of the class list ways drugs and alcohol could interfere. If the goal is, for example, playing college football, marijuana use could affect physical and mental performance on the field, lower your grades or even get you thrown off the team. Encourage your students to see that the temporary fun of drinking and drugs can come with dangerous risks and unwanted consequences both short- and long-term.

You Might Also Like

How To Teach Kids To Wash Their Hands So They’ll Remember It Forever

7 easy and fun ideas! Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- JMIR Mhealth Uhealth

- v.10(4); 2022 Apr

Mobile Health Apps Providing Information on Drugs for Adult Emergency Care: Systematic Search on App Stores and Content Analysis

Sebastián garcía-sánchez.

1 Pharmacy Department, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain

Beatriz Somoza-Fernández

Ana de lorenzo-pinto, cristina ortega-navarro, ana herranz-alonso, maría sanjurjo.

Drug-referencing apps are among the most frequently used by emergency health professionals. To date, no study has analyzed the quantity and quality of apps that provide information on emergency drugs.

This study aimed to identify apps designed to assist emergency professionals in managing drugs and to describe and analyze their characteristics.

We performed an observational, cross-sectional, descriptive study of apps that provide information on drugs for adult emergency care. The iOS and Android platforms were searched in February 2021. The apps were independently evaluated by 2 hospital clinical pharmacists. We analyzed developer affiliation, cost, updates, user ratings, and number of downloads. We also evaluated the main topic (emergency drugs or emergency medicine), the number of drugs described, the inclusion of bibliographic references, and the presence of the following drug information: commercial presentations, usual dosage, dose adjustment for renal failure, mechanism of action, therapeutic indications, contraindications, interactions with other medicinal products, use in pregnancy and breastfeeding, adverse reactions, method of preparation and administration, stability data, incompatibilities, identification of high-alert medications, positioning in treatment algorithms, information about medication reconciliation, and cost.

Overall, 49 apps were identified. Of these 49 apps, 32 (65%) were found on both digital platforms; 11 (22%) were available only for Android, and 6 (12%) were available only for iOS. In total, 41% (20/49) of the apps required payment (ranging from €0.59 [US $0.64] to €179.99 [US $196.10]) and 22% (11/49) of the apps were developed by non–health care professionals. The mean weighted user rating was 4.023 of 5 (SD 0.71). Overall, 45% (22/49) of the apps focused on emergency drugs, and 55% (27/49) focused on emergency medicine. More than half (29/47, 62%) did not include bibliographic references or had not been updated for more than a year (29/49, 59%). The median number of drugs was 66 (range 4 to >5000). Contraindications (26/47, 55%) and adverse reactions (24/47, 51%) were found in only half of the apps. Less than half of the apps addressed dose adjustment for renal failure (15/47, 32%), interactions (10/47, 21%), and use during pregnancy and breastfeeding (15/47, 32%). Only 6% (3/47) identified high-alert medications, and 2% (1/47) included information about medication reconciliation. Health-related developer, main topic, and greater amount of drug information were not statistically associated with higher user ratings ( P =.99, P =.09, and P =.31, respectively).

Conclusions

We provide a comprehensive review of apps with information on emergency drugs for adults. Information on authorship, drug characteristics, and bibliographic references is frequently scarce; therefore, we propose recommendations to consider when developing an app of these characteristics. Future efforts should be made to increase the regulation of drug-referencing apps and to conduct a more frequent and documented review of their clinical content.

Introduction

Digital technologies are an increasingly relevant resource for health services because they can improve the quality, efficiency, and safety of health care, a particularly relevant issue in the event of emergencies, disasters, and other unplanned care situations [ 1 ]. In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the quantity and quality of mobile health apps owing to the efforts made by health professionals and app developers. At the beginning of 2021, almost 50,000 medical apps were available on the main download platforms (Apple App Store and Google Play Store) [ 2 ]. Mobile apps are changing the health care landscape because they facilitate the exchange of information among professionals, researchers, and patients and enable easy access to quality services during clinical practice [ 3 , 4 ].

The need for a quick response is one of the most prominent characteristics of emergency medicine. Examples of the high care burden experienced in emergency departments can be seen in the nearly 130 million visits in 2018 in the United States or the 30 million visits registered each year in Spain [ 5 , 6 ]. A variety of apps have been developed in recent years to improve patient care in these departments [ 7 , 8 ]. Medical emergency apps are now a key element of clinical practice as they can be used as clinical decision tools, case management tools, and sources of clinical information. A desirable feature of these apps is that they can be used quickly because of the need to provide a rapid response to the broad spectrum of clinical scenarios occurring in emergency departments. Recent studies on mobile devices and medical apps in emergency rooms [ 9 , 10 ] have shown that the apps most frequently used by emergency health professionals are medical formulary and drug-referencing apps (84.4%), followed by disease diagnosis and management apps (69.5%) [ 10 ].

Health care pressure, stressful situations, and the need for multiple high-alert medications make emergency departments the perfect setting for drug-related problems [ 7 ]. Insufficient information on drugs is the most common cause of medication errors, which can lead to adverse drug events involving temporary or permanent harm to patients and higher health care costs [ 11 , 12 ]. The information needed in an emergency department includes multiple drug characteristics such as indications, dosing, administration, pharmaceutical compatibilities, adverse reactions, interactions, and contraindications [ 11 , 13 ]. The usefulness of medical apps as a source of information on drug-related characteristics should be highlighted, although the literature still contains relevant gaps concerning these tools. To date, no study has addressed the quantity and quality of smartphone apps that provide information on emergency drugs.

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to identify apps designed to assist health care professionals in managing drugs for adult emergency care and describe their main characteristics and functionalities. As secondary objectives, we designed a score to estimate the amount of drug information contained in each app and analyzed the relationship between this score and the relevant app characteristics. We also analyzed whether some of the variables selected could affect user satisfaction (app user ratings).

Search Strategy and App Selection

We performed an observational, cross-sectional, descriptive study of smartphone apps available on the iOS and Android platforms that provide information on drugs used for adult emergency care.

The methodology used for app selection was based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) system [ 14 ]. To identify emergency drugs–related apps, a search was conducted between February 15 and February 19, 2021, on the digital distribution platforms Google Play Store (Android) and Apple App Store (iOS), which are the app stores with the most apps available at present [ 15 ]. The search terms were “emergency drugs ” OR “ fármacos de urgencias ” and “emergency medicine ” OR “medicina de urgencias y emergencias. ” We extracted text from app store descriptions and selected apps available in English or Spanish whose content was fully dedicated to drugs commonly used in the emergency room (hereafter referred to as emergency drugs apps ) and apps related to the field of emergency medicine that contained a section on medications ( emergency medicine apps ). Apps aimed at pediatric emergencies were excluded because of relevant differences in the use of drugs in children (eg, dosage, treatment algorithms, and selection). Both free and paid apps were included. Apps from the Google Play Store were downloaded onto a Xiaomi Mi 9 SE (version 9 PKQ1.181121.001; Android), and apps from the Apple App Store were downloaded onto an iPhone 11 (version 14.4; iOS).

Ethical Considerations

No patients were involved in the study and therefore ethical board approval was not sought, as it is considered unnecessary under RD 1090/2015 regulating clinical trials with medicinal products and the Ethics Committees for Research with medicinal products, and Law 14/2007 on Biomedical Research.

Data Extraction

We collected the following information from the download platforms: app name, operating system (Android, iOS, or both), developer affiliation, country of origin, language, category, cost, publication date, date of last update, size, version, number of downloads, and user ratings. These indicators are commonly used in studies on health-related apps [ 16 - 19 ]. The overall mean weighted user rating was calculated by considering the number of ratings from both app stores. For the rest of the analysis, when the same app was available on both platforms, we only considered the version available on the Google Play Store as Android is the leading operating system worldwide and the Apple App Store provides less information (no data on the number of downloads). Subsequently, all apps were downloaded and their contents were evaluated. We counted the number of drugs included in each app and determined whether they belonged to ≥1 drug classes. We then evaluated whether the apps contained information on the following fifteen drug-related characteristics: (1) commercial presentations, (2) usual dosage, (3) dose adjustment for renal failure, (4) mechanism of action, (5) therapeutic indications, (6) contraindications, (7) interaction with other medicinal products, (8) use in pregnancy and breastfeeding, (9) adverse reactions, (10) method of preparation and administration, (11) stability data and incompatibilities, (12) identification of high-alert medications, (13) positioning in treatment algorithms, (14) information about medication reconciliation, and (15) cost. The selection of these indicators was discussed by the research team based on the most frequent requests received from emergency medicine pharmacy services and drug information centers [ 12 , 13 ]. High-alert medications are defined as drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used erroneously [ 20 ]. Medication reconciliation is defined as the formal process in which health care professionals partner with patients to ensure accurate and complete medication information transfer at transitions of care [ 21 ].

We assigned a score of 0 to 15 according to the amount of drug information provided in the app. A score of 0 indicates that the app did not include any information about the 15 drug characteristics analyzed, and a score of 15 indicates that all characteristics were shown in the app. Finally, we also evaluated whether the apps included bibliographic references on drug-related concerns.

Data Analysis

All apps were independently evaluated by 2 hospital clinical pharmacists (SGS and BSF). The variables were coded and entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The Cohen κ coefficient was calculated using Reliability Calculator for 2 coders [ 22 ] to analyze the level of agreement between the data collected by each investigator. Following this analysis, disagreements on the reported results were resolved through iterative discussion and consensus.

A statistical analysis was performed using Stata (version IC-16; StataCorp). On the basis of previously published studies on mobile health apps, we measured the association between a series of app characteristics (developer, main topic, cost, and number of downloads) and user ratings (which indicate user satisfaction) or the score assigned to the app (which indicates the variety of content on drug information). We also analyzed whether the inclusion of bibliographic references could be influenced by the app developer (health-related or non–health-related). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate whether continuous variables were normally distributed. For normally distributed data, differences were assessed using the 2-tailed Student t test for 2 categories and ANOVA for ≥2 categories; for nonnormally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The correlation between quantitative variables was evaluated using the Spearman correlation test. Categorical variables were compared using an uncorrected chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P <.05.

Mobile App Search

Combined keyword searches of the Google Play Store and Apple App Store yielded 645 apps potentially related to emergency drugs. A flow diagram illustrating the selection and exclusion of apps at various stages of the study is shown in Figure 1 . We removed 88 apps as duplicates, with the same app name and developer appearing on both download platforms. The remaining 557 apps were further screened. We extracted information from the store app description and removed 293 apps that were not related to emergency medicine and 20 apps aimed at pediatric emergencies. We then exhaustively analyzed the descriptions of the remaining apps and downloaded them to determine whether the information was inaccurate. From the resulting apps, we removed 4 duplicates with different app names within the same store. We eventually excluded 191 apps that did not contain a specific section on drugs. Following this systematic search, we identified 49 apps that met the inclusion criteria. In total, 65% (32/49) of the apps were found on both digital distribution platforms, whereas 22% (11/49) were obtained only from the Google Play Store, and 12% (6/49) were only available from the Apple App Store.

A flow diagram illustrating the search process for the apps analyzed in the study.

Two independent researchers (SGS and BSF) further analyzed the characteristics, functionalities, and contents of the 49 apps selected. The mean Cohen κ coefficient for interrater reliability was 0.94 (SD 0.05).

Analysis of General Characteristics of Apps

Textbox 1 shows the names of the 49 apps classified by their main topic (emergency drugs or emergency medicine).

List of emergency drugs apps and emergency medicine apps.

Emergency drugs apps

- 50 Drugs in emergency

- Antídotos

- Common 50 drugs for emergency

- Drogas en emergencia y UCI

- Emergency drugs

- Emergency drugs (Antonio Frontera)

- Emergency drugs (Ferrazza)

- Emergency medication reference

- EMS calculator or EMS drugs fast

- EMS drug cards

- Farmacos de urgencias SES or urgencias SES

- FarmaPoniente

- Goteo para vasoactivos

- Guía farmacológica

- Guía URG

- Medicina de urgencias

- Paramedic drug list

- Perfusiones urgencias

- Pocket drug guide EMS or EMS pocket guide

- UrgRedFasterFH

Emergency medicine apps

- AHS EMS MedicalProtocols

- Arritmias urgencias

- Basic emergency care

- Chuletario urgencias extrahospitalarias

- Emergency central

- Emergency medicine on call

- EMRA antibiotic guide

- EMRA PressorDex

- EMS ACLS guide

- EMS notes: EMT and paramedic

- ICU ER facts made Incred quick

- iTox Urgencias intoxicación

- Manual de procedimientos SAMUR

- Médico de urgencias

- My Emergency Department

- Odonto emergencias

- Urgencia HBLT or Guia urgencia HBLT

- Urgencias Extrahospitalarias

- WikEM—Medicina de emergencia

- Zubirán. Manual Terapéutica 7e

By origin, 41% (20/49) of the apps were developed in North America, 35% (17/49) in Europe, 12% (6/49) in South America, 4% (2/49) in Asia, and 2% (1/49) in Africa. The origin of 6% (3/49) of the apps could not be determined. Of the 49 apps analyzed, 27 (55%) were published only in English, 21 (43%) were published only in Spanish, and 1 (2%) was available in both languages. Most apps (44/49, 90%) were classified in the category of medicine. The other categories were health and well-being (3/49, 6%) and education (2/49, 4%).

Slightly more than half of the apps were free to download (29/49, 59%), whereas the other 41% (20/49) required payment, with a cost ranging from €0.59 (US $0.64) to €179.99 (US $196.10) (median €8.99 [US $9.79]) and a mean cost of €20.82 (US $22.68) (SD €40.81 [US $44.46]). Two apps were for the exclusive use of workers at the center where they were developed, and 1 app could only be used with a code acquired after purchasing a book; therefore, they could not be fully analyzed. In addition, the content of 1 app was unavailable because of a download error that affected the latest versions of Android. In these cases, we collected as much information as possible from the description of the app and images available on the digital distribution platforms.

The average size of the apps was 23.89 (SD 23.28) MB. The content of 27% (13/49) of the apps was updated 6 months before the search. A further 14% (7/49) of the apps were updated in the previous year. A total of 59% (29/49) of the apps had not been updated for more than a year; of these, 12 (24% of the overall apps) had not been updated for more than 3 years. A total of 16% (8/49) apps had not been updated since the date of the first publication. The average time between the date of analysis and the date of the most recent update was 23.3 (SD 23.6) months. iOS apps were excluded from this last analysis because of the lack of information on the day of the most recent update.

About half of the apps were developed by private and for-profit organizations (22/49, 45%) as follows: health-related technology companies (n=12, 24%); non–health-related technology companies (n=9, 18%); and medical publishers (n=1, 2%). A total of 22% (11/49) apps were developed by non–health-related professionals. Among the 78% (38/49) apps developed by health care professionals, 29% (14/49) were developed by individual professionals, whereas the rest were developed by technology companies or medical publishers (13/49, 27%), or with the involvement of a health care organization (eg, hospital, public health agency, or professional society; 11/49, 22%). A complete list of developers is provided in Table 1 .

Developers of the apps (N=49).

| Developer | Value, n (%) |

| Individual health professional | 14 (29) |

| Health-related technology company | 12 (24) |

| Non–health-related technology company | 9 (18) |

| Hospital | 3 (6) |

| Public health agency | 3 (6) |

| Individual non–health professional | 2 (4) |

| Medical or pharmaceutical society | 2 (4) |

| Other health professional organization | 2 (4) |

| University | 1 (2) |

| Medical publisher | 1 (2) |

The number of downloads can only be determined in the apps found in the Google Play Store, as this information is not available in the Apple App Store. The median number of downloads was >5000 (range >1 to >100,000). Detailed information regarding the number of downloads is presented in Table 2 .

Apps classified by the number of downloads (N=43).

| Number of downloads | Value, n (%) |

| 1-100 | 2 (5) |

| 101-1000 | 5 (12) |

| 1001-5000 | 12 (28) |

| 5001-10,000 | 6 (14) |

| 10,001-100,000 | 12 (28) |

| >100,000 | 6 (14) |

We evaluated the association between the cost of apps and the number of downloads. Owing to the small sample sizes, the number of downloads was broken down for this analysis into 3 categories: 1 to 1000, 1001 to 10,000, and >10,000 downloads. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups ( F 42 =0.24; P =.70).

The analyses of user ratings included 40 apps, as no data were available for 9 apps. The mean overall weighted user rating of apps according to the number of valuations was 4.023 out of 5 (SD 0.71). The average user ratings were almost identical ( t 38 =−0.01; P =.99) for apps developed by health professionals (n=30, mean 4.240, SD 0.707) and non–health professionals (n=10, mean 4.243, SD 0.470). Free apps were rated higher (n=27, mean 4.277, SD 0.680) than paid apps (n=13, mean 4.197, SD 0.621; t 38 =−2.27; P =.03).

Analysis of Contents of Apps

Approximately half of the apps focused on emergency drugs (22/49, 45%), whereas the rest (27/49, 55%) focused on emergency medicine in a broader sense. We did not find statistically significant differences ( z =−1.7; P =.09) between the average user rating of emergency drugs apps (4.163/5; 16 apps) and emergency medicine apps (4.296/5; 24 apps).

The median number of drugs included in the apps was 66 (range 4 to >5000). The apps classified according to the number of drugs analyzed are shown in Table 3 .

Apps classified by number of drugs analyzed (N=47).

| Number of drugs | Value, n (%) |

| 1-25 | 9 (19) |

| 26-50 | 12 (26) |

| 51-100 | 10 (21) |

| 101-200 | 11 (23) |

| >200 | 3 (6) |

| >1000 | 2 (4) |

Of 49 apps, 6 (12%) analyzed only a specific class of drugs: antidotes (n=2, 33%), vasopressors (n=2, 33%), antibiotics (n=1, 17%), and antiarrhythmics (n=1, 17%).

Table 4 shows the 15 drug characteristics of the apps analyzed. Most apps included information about therapeutic indications (38/48, 79%) and the most common doses (43/49, 88%). Other drug-related concerns found in more than half of the apps were commercial presentations (27/47, 57%), mechanism of action (26/47, 55%), contraindications (26/47, 55%), method of preparation and administration (25/48, 52%), and adverse reactions (24/47, 51%). Only 17% (8/47) of apps provided data on stability and incompatibilities. Identification of high-alert medications was found in 6% (3/47) of the apps. Information on drug costs was present in only 2% (1/47) of the apps. Similarly, information about medication reconciliation in the emergency room was found in only 2% (1/47) of the apps.

Drug characteristics described in the apps.

| Drug characteristic | Value, N | Value, n (%) |

| Commercial presentations | 47 | 27 (57) |

| Usual dosage | 49 | 43 (88) |

| Dose adjustment for renal failure | 47 | 15 (32) |

| Mechanism of action | 47 | 26 (55) |

| Therapeutic indications | 48 | 38 (79) |

| Contraindications | 47 | 26 (55) |

| Interaction with other medicinal products | 47 | 10 (21) |

| Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding | 47 | 15 (32) |

| Adverse reactions | 47 | 24 (51) |

| Method of preparation and administration | 48 | 25 (52) |

| Stability data and incompatibilities | 47 | 8 (17) |

| Identification of high-alert medications | 47 | 3 (6) |

| Positioning in treatment algorithms | 47 | 19 (40) |

| Information about reconciliation | 47 | 1 (2) |

| Cost | 47 | 1 (2) |

Most apps (29/47, 62%) did not include bibliographic references regarding drug-related concerns. The percentage of apps that included this kind of information was 44% (16/36) in the group of apps developed by health professionals and 18% (2/11) in the group of apps developed by non–health professionals ( χ 2 1 =2.5; P =.12).

Analysis of Drug Information Score

We assigned a score of 0 to 15 according to the number of drug characteristics provided in the app. The mean score was 5.89 (SD 2.91). Of the 47 apps, 22 (47%) apps received a score ranging from 0 to 5, a total of 21 (45%) apps received a score from 6 to 10, and 4 (8%) apps received a score from 11 to 13. There was no correlation between this score and the app user ratings (ρ=−0.17; P =.31).

The average score for apps developed by health professionals (n=36, mean 6.00, SD 3.04) was slightly higher than that for apps developed by non–health professionals (n=11, mean 5.55, SD 2.54), although the difference was not significant ( t 45 =−0.45; P =.66). Similarly, no statistically significant differences ( t 45 =−0.78; P =.44) were found between the average score of emergency drugs apps (n=21, mean 5.52, SD 2.75) and emergency medicine apps (n=26, mean 6.19, SD 3.06) or between the average score of free (n=27, mean 5.90, SD 2.91) and paid (n=20, 5.47, SD 3.07) apps ( t 45 =−0.83; P =.40).

Finally, we compared the difference between the number of downloads and drug information score. The average score was 4.57 (SD 1.81) for apps with 1 to 1000 downloads (7/41, 17%), 6.69 (SD 3.28) for apps with 1001 to 10,000 downloads (16/41, 39%), and 6.61 (SD 2.55) for apps with >10,000 downloads (18/41, 44%). No statistically significant differences were found between the groups ( F 40 =1.63; P =.21).

Studies on the content of mobile health apps are increasingly frequent, and apps related to relevant diseases such as cancer or COVID-19 infection have recently been analyzed [ 16 , 17 , 23 , 24 ]. Nevertheless, research on apps designed for use in emergency rooms remains insufficient. In this study, we provide a comprehensive and unique review of smartphone apps that provide information on drugs for adult emergency care.

The use of mobile devices by emergency health professionals is common, and apps related to this field of medicine are proliferating [ 10 , 25 ]. Emergency rooms are areas where a high volume of patients must be seen within a short period, and work interruptions are very frequent [ 26 ]. In this complex environment, incorrect use of mobile devices can increase the risk of distraction and may affect patient safety [ 9 ]. Nevertheless, when these devices are used properly, they have enormous potential to improve medical practice, for instance, by allowing quick access to relevant and evidence-based information, which facilitates decision-making and can help reduce error rates. In a recent survey of professionals in an emergency department, most respondents found mobile devices useful for better coordinating care among providers and beneficial for patient care [ 10 ].

Principal Findings on General Characteristics and Comparison With Prior Studies

Our study provides a general perspective on apps designed to help health care professionals with drug management for adult emergency care. Given that medication errors are commonly caused by insufficient information on drugs [ 12 ], we analyzed these apps in detail. This is one of the most comprehensive studies of apps aimed at providing information about drugs for health care professionals. Recently, a study identified more than 600 drug-related apps, and approximately two-third of them were categorized within the medication information class [ 27 ]. The authors distinguished among apps for patients, apps for health professionals, and apps that can be used by both groups. Recent studies on patient-focused drug apps have analyzed those that help patients understand and take their medications or those with a medication list function [ 28 , 29 ]. In addition, apps for treatment adherence have been the subject of intensive research [ 30 - 35 ]. Some papers have also been published on apps about drug-drug interactions [ 36 , 37 ]. This is an issue traditionally addressed by health care professionals, although nowadays many apps for checking interactions are intended to be used by patients rather than health care professionals.

Knowledge of the characteristics of drug apps designed to be used exclusively by health care professionals is still limited. Few studies have aimed to analyze the functionalities and content of these apps. A study conducted in 2013 identified 306 apps providing drug reference information and prescribing material, and analyzed cost, updates, user ratings, intended area of use, and medical involvement in app development [ 38 ]. More recently, a study published in 2017 compared 8 apps for dosage recommendations, adverse reactions, and drug interactions [ 39 ]. The quality of the apps targeting medication-related problems has been assessed. Of the 59 apps analyzed, 23 (39%) contained medication information features [ 40 ]. Very recently, a study identified 23 drug reference apps with local drug information in Taiwan (including those aimed at both patients and professionals) and analyzed their quality and factors influencing user perceptions [ 41 ]. In the field of emergency care, a recent study analyzed apps for the management of drug poisoning [ 42 ]. Of the 17 apps identified, 14 (82%) presented diagnosis and treatment guides, and 3 (18%) were specifically on antidotes and their dosage.

In our study, we first collected the information available in the app marketplace descriptions (eg, number of downloads and user ratings) before downloading the apps and analyzing their content in detail. This strategy differs from those of other recent studies, in which a greater number of apps were identified but where the analysis was limited to the marketplace description [ 8 , 18 , 19 , 38 ]. Among our main findings, we can highlight that 22% (11/49) of the apps were not developed by health care professionals. This is a lower percentage than that reported in other studies on mobile health apps [ 18 , 23 , 43 ]. In 2013, there was no evidence of involvement of health care professionals in the development of 32.7% (100/306) of the apps available to support prescribing practice [ 38 ]. It should also be noted that apps for patient medication management are developed mainly by the software industry, without the involvement of health care professionals [ 28 , 31 ]. Nevertheless, our findings should be considered relevant, given that the apps we analyzed are intended to be used in complex and emergency situations. In addition, information on authorship is scarce in many of the apps evaluated.

More importantly, we found that more than half of the apps (29/47, 62%) did not include bibliographic references or had not been updated for more than a year (29/49, 59%). Our results are in accordance with a previous study analyzing 23 apps with medication information, most of which did not provide supporting references [ 40 ]. Of particular concern is the lack of updates in the apps analyzed in our study, as this indicator has worsened compared with the study conducted by Haffey et al [ 38 ], in which 44.4% (136/306) of the apps had either been released or updated within the last 6 months, and a further 24.2% (74/306) within 1 year [ 38 ]. These concerns raise doubts about the quality and reliability of the information provided by these apps aimed at emergency health care professionals, as incorrect drug information may remain for long periods.

Doubts arise when a health app is developed by non–health professionals [ 44 , 45 ]. We found that bibliographic references were included in 44% (16/36) of the apps developed by health professionals and in only 18% (2/11) of the apps developed by non–health professionals. This result was not statistically significant ( P =.12), probably because of the small sample size, although it highlights the uncertainty surrounding the sources of information provided in apps developed by non–health professionals. The reliability and authority of information should be analyzed by health care professionals who are more capable of evaluating, reviewing, and verifying the content of health-related apps. In the field of medication, pharmacists should play a vital role in reviewing apps.

About half of the apps (20/49, 41%) required payment to access all the content, with a cost ranging from €0.59 (US $0.64) to €179.99 (US $196.10). This is a similar percentage than that observed in a recent study on drug poisoning management apps [ 42 ]. Nevertheless, it is considerably higher than that observed in other recent reviews of apps for medical emergencies [ 8 ], medication management and adherence for patients [ 28 , 32 ], or checking for drug-drug interactions [ 36 ]. We hypothesize that these differences could arise because the apps analyzed in our study are aimed exclusively at health care professionals and are designed for use in health care facilities. A study conducted in 2013 on apps to support drug prescribing or provide pharmacology education showed that 68% (208/306) of the apps required payment, with a mean price of £14.25 (US $18.57) per app and a range of £0.62 (US $0.81) to £101.90 (US $132.76) [ 38 ]. The cost of apps also seems to be influenced by the origin of the developer [ 41 ]. In any case, cost is an important determinant in the decision to adopt a mobile health app, regardless of age group and socioeconomic status [ 46 ]. In addition, payment for the apps analyzed in our study could be a relevant limitation for health care professionals who only occasionally work in emergency rooms, as is common in many hospitals.

To date, few studies have analyzed the factors that influence user satisfaction with apps [ 18 , 47 , 48 ]. The number of downloads and user ratings are usually correlated and have been proposed as indicators of acceptability and satisfaction with mobile health apps [ 49 , 50 ]. A secondary objective of our study was to learn more about user behavior with emergency medicine apps, for which we analyzed whether factors such as cost, the main theme of the app (emergency medicine or emergency drugs), or the app developer (health-related or non–health related) could influence user ratings. The free apps analyzed in our study had higher user ratings than paid apps, although no association was found between the cost and number of downloads. We found no further statistically significant differences, probably because of the small sample size. The number of downloads and user ratings probably depend on multiple factors. Navigation, performance, visual appeal, credibility, and quantity of information have recently been identified as the most influential factors on higher user ratings in a study analyzing 23 drug reference apps [ 41 ]. Previous studies have reported highly variable results for the influence of expert involvement in app development on user ratings and the number of downloads [ 18 , 41 , 49 ]. In any case, user ratings and downloads should not be considered good predictors of the quality and reliability of medical apps because they could be influenced by other factors, such as low price, in-app purchase options, in-app advertisements, and recent updates [ 18 , 51 , 52 ]. In our study, the number of downloads, cost, and user ratings were not associated with a score created to quantify the variety of relevant information on drug characteristics in the apps ( P =.21, P =.40, and P =.31, respectively). Further research should analyze the reliability of the clinical content of drug information apps and corroborate its association with a greater intention to use or better user satisfaction.

Drug Information Gaps

At present, there are no standardized guidelines for assessing the clinical content and quality of mobile health apps [ 18 ]. A highly specific quality assessment tool was developed to assess the quality of apps targeting medication-related problems, including those with medication information features [ 40 ]. Nevertheless, the most commonly used methodology to assess the quality of medical apps is the Mobile Application Rating Scale [ 53 - 55 ], as well as in studies on drug apps [ 30 , 36 , 37 , 41 ]. The total number of features has been associated with the total Mobile Application Rating Scale score in a study on apps for potential drug-drug interaction decision support [ 36 ].

In our study, we paid special attention to the information provided by the apps regarding relevant drug characteristics. We found that most apps included information about the usual dosage (43/49, 88%) and therapeutic indications (38/48, 79%). Nevertheless, other relevant characteristics were found in less than half of the apps, such as dose adjustment for renal failure (15/47, 32%) and use in pregnancy and breastfeeding (15/47, 32%). Interaction with other medicinal products was found in only 21% (10/47) of the apps, despite being a major problem in patient safety. Drug-drug interaction checks are one of the most frequent functional categories within the current medication-related app landscape [ 27 , 56 ], but relevant quality and accuracy problems have been detected in apps, including this feature [ 36 , 37 ]. In addition, other relevant information on drug safety, such as contraindications (26/47, 55%) and adverse reactions (24/47, 51%), was found in approximately half of the apps analyzed in our study. Furthermore, it is worrying that only 6% (3/47) of the apps clearly identified high-alert medications, despite efforts made to avoid errors with these drugs [ 12 ].

In clinical practice, many medication-related inquiries are about the method of administration; however, our study showed that this information is included in slightly more than half of the apps (25/48, 52%). In addition, stability data and incompatibilities were present in only 17% (8/47) of the apps. Nurses have also been reported to be frequent app users in daily practice, albeit at a slightly lower percentage than that observed by physicians [ 10 ]. Therefore, apps for the use of drugs in the emergency department should be designed to provide more information on drug administration characteristics.

Finally, incorrect medication reconciliation in the emergency department can lead to relevant medication errors [ 57 ]. We found only 1 app that appropriately addressed this issue, including information on the maximum time to carry out reconciliation or the possible presence of withdrawal syndrome. Given that medication reconciliation has been considered the most relevant activity carried out by pharmacists in emergency departments [ 58 ], it would be desirable for apps related to emergency drugs to provide more information on this matter.

Recommendations for Development of an Emergency Drugs App

There are a growing number of health apps on the market with highly variable designs and content, and it is difficult to determine which are the most useful for health care professionals. Given the relative absence of legislation on medical apps [ 59 ] and the risks associated with drugs used in the emergency room, it would be interesting to propose a series of improvements in the content of apps for emergency drugs. The results of our study and clinical experience enable us to make several recommendations.

Design, ease of use, and the ability to quickly respond to questions that arise during daily clinical practice are especially relevant characteristics, considering that these apps are to be used in a stressful environment. The success of an app for emergency professionals depends on quickly obtaining a reliable response.

Our findings could help developers design apps that provide drug-related information most frequently demanded by health care professionals. Drug information centers have historically received the most inquiries regarding therapeutic indications, adverse reactions, and identification of medical products [ 13 ]. In addition, information on contraindications, appropriate dosage, and major drug-drug interactions should be included to prevent major adverse events [ 11 ]. We provided a score to measure the amount of drug information included in each app, and our results showed that a greater amount of information is not necessarily associated with better user ratings. Therefore, it could be beneficial to design apps with content aimed exclusively at doctors and apps for nurses, although with maximum information of interest for each of these professionals. For example, apps with information on drug administration and incompatibilities would have the potential to help nursing staff by reducing their workload and, ultimately, the risk of drug-related errors. Strategies to identify high-alert medications should be included in all emergency drug apps, regardless of the group of health care professionals they focus on [ 12 ].

We recommend caution with respect to the sources of information used to elaborate the content of the app to ensure that it is reliable. Apps should only be considered reliable based on an extensive literature review, expert panel review, or peer review. The author’s affiliation and bibliographic references to scientific and clinical evidence should always be clearly shown [ 60 ], and health professionals participating in reviewing and app updates should be clearly identified.

As previously suggested [ 16 ], we believe that future legislation should require a more comprehensive description of the mobile app marketplace, with detailed information on authorship and the process used to review app functionalities and the clinical information provided. All information must be supported by appropriate bibliographic references, and developers should preferably be clinicians with experience writing or synthesizing medical evidence. Thus, the information provided, which should be checked by independent reviewers or endorsed by health organizations of recognized prestige, will be more reliable. In addition, we suggest that app developers clearly identify the target user group and provide the maximum amount of drug information relevant to each professional category. It may also be relevant for a partner with a technology company to make apps more attractive and user-friendly.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, our study was limited by the inclusion criteria. There are hundreds (perhaps thousands) of apps providing drug-related information, and some may be useful for emergency room professionals; however, they were not analyzed in this study because our aim was to review apps specifically related to emergency drugs or medicine in adults. Drug information indicators were selected and analyzed by the authors and were therefore not validated. A more comprehensive analysis of drug information apps may be the subject of future research, for which our methodology could prove useful. Our approach could be adapted to analyze apps related to child health care or to include indicators not described in our study, such as information on pharmacokinetic properties, therapeutic drug monitoring, and pharmacogenomics. Other limitations are associated with the study design. We only analyzed the Android version when the same app was available on Android and iOS platforms. It should be noted that some characteristics, such as the date of the last update, may vary among platforms. In addition, we analyzed apps in English and Spanish. Although Spanish is the language with the second highest number of native speakers, many health professionals are not sufficiently competent in the language to use these apps comfortably. Our study was also limited by the fact that it only analyzed whether a series of drug characteristics of interest were included in the app. Further research is needed to evaluate the clinical accuracy of the drug information provided by the apps. One possible approach would be a peer-review process to evaluate app contents in terms of the reliability and quality of information according to the best available clinical evidence.

We conducted a comprehensive and unique systematic review of apps that provide information on drugs for adult emergency care. We identified 49 apps according to the PRISMA methodology and conducted a content analysis on most of them. Health-related app developers, the main topic of the app (emergency drugs or emergency medicine), and a greater amount of drug information were not associated with higher app user ratings. Slightly less than half of the apps (20/49, 41%) required payment, with a cost ranging from €0.59 (US $0.64) to €179.99 (US $196.10). We noted that 22% (11/49) of the apps were not developed by health care professionals. Most apps include information about the usual dosage and therapeutic indications, although information on safety and drug administration is much less frequent. Very few apps provide relevant information, such as high-alert medication notices and instructions for drug reconciliation. In addition, more than half of the apps (29/47, 62%) did not include bibliographic references. These findings cast doubts on the quality of many apps. Therefore, we propose a series of issues that should be considered when developing an app of these characteristics and advocate for greater regulation and more frequent and documented review of app content.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Thomas O’Boyle for editing and proofreading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

Authors' Contributions: This study was the result of a collaboration between all the authors. SGS and BSF contributed equally to this work. SGS designed the study, supervised and performed the data collection, and drafted the manuscript. BSF conducted the data analysis and substantially contributed to data collection and drafting of the manuscript. AdLP and CON conceived the original research idea and made a considerable contribution to the design of the study. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved its final version for publication.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Header - Callout

In Crisis? Call or Text 988

2020 NSDUH Detailed Tables

Get detailed national estimates from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The tables provide comprehensive statistics on substance use, mental health, and treatment in the United States. Although past year estimates are provided, they cannot be compared to 2020 estimates. This is because changes in survey methodology mean the indicators are not comparable to past NSDUH estimates.

The tables are based on the NSDUH survey, which interviews people ages 12 or older in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. In the tables, indicators are broken out by a variety of demographic, geographic, and economic variables.

The following topics are covered, among others: drug, alcohol, nicotine, and tobacco product use and initiation; substance use disorder (SUD); substance use risk and protective factors; availability of substance use treatment; any mental illness (AMI) and serious mental illness (SMI); major depressive episode (MDE); suicidal thoughts and behaviors; serious psychological distress (SPD); mental health service utilization; treatment for depression; and co-occurrence of mental health issues and SUDs. In 2020, these tables also present the perceived effects of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on substance use and mental health. 1

All of the tables can be downloaded in a zip file which contains both an html and PDF file containing every table. Alternatively, users can open the clickable Table of Contents to go to a particular section. Click on “PE” to get to a population estimate or percentage table, and “SE” to get a standard error table.

1. Please note that selected tables have been revised.

View/Download Files

More like this, report resources.

- README (pdf | 80.31 KB)

- PDF and HTML files (zip | 119.84 MB)

- Clickable Table of Contents (htm | 185.01 KB)

| Collected Date: 2022 | Published Date: November 13, 2023 | Type: Data Table |

| Collected Date: 2021 | Published Date: January 04, 2023 | Type: Data Table |

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

Shots - Health News

Health insurers cover fewer drugs and make them harder to get.

Sydney Lupkin

Insurance Pinch

Health insurers' lists of covered drugs have gotten tighter. Darwin Brandis/Getty Images/iStockphoto hide caption

Insurance coverage isn’t what it used to be when it comes to prescription drugs.

Insurance companies’ lists of covered drugs, called formularies, are shrinking. In 2010, the average Medicare formulary covered about three-quarters of all drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration, according to new research by GoodRx , a website that helps patients find discounts on prescription drugs. Now, it’s a little more than half.

The GoodRx report is called “The Big Pinch,” because it illustrates how patients are pinched between the drug companies’ high prices and their health insurance companies’ limited drug coverage. GoodRx is an NPR funder.

“I think far too often people talk way too much about the cost of their prescription and we're screaming about the high cost of prescriptions,” says Tori Marsh, director of research at GoodRx . “But what we're not talking about is the poor coverage.”

What to know about the drug price fight in those TV ads

Commercial plans likely cover even fewer drugs than Medicare plans do because they’re not bound by the same federal coverage mandates as Medicare, Marsh says.

What’s more, according to the report, patients have clear more hurdles to get the drugs that are covered by their insurance than they did 14 years ago.

Half the drugs insurance companies cover require things like prior authorization , in which insurers require doctors to take an additional step of justifying why they’ve written a prescription. This step can cause delays and make it harder for patients to get drugs their doctors prescribe -- or deter people from filling their prescriptions altogether.

Insurers trade patient access to medicines for lower prices

Still, limited formularies and restrictions on access serve a business purpose, says Jeromie Ballreich, a health economist at Johns Hopkins University . They give negotiating leverage to the part of your health insurance that deals with drug coverage — called a pharmacy benefit manager.

“Their way to kind of combating the jump in prices or the jump in spending is to really kind of hardball negotiate with drug companies,” says Ballreich.

For instance, an insurance company will say no to a drugmaker’s offer, but if it lowers the price or increases rebates, the insurer would make the drug a preferred option without prior authorization.

The negotiated prices and rebates don’t typically get passed directly to consumers as lower copays but they can reduce pressure on insurance premiums.

The trade group for pharmacy benefit managers, the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, took issue with the GoodRx report.

“PBMs make recommendations and assist employers in designing pharmacy benefits that fit their unique patient population needs,” says PCMA spokesman Greg Lopes. “PBMs have a proven track record of creating access to affordable medications for payors and patients.”

Drugmakers have criticized PBMs for not adequately sharing the discounts they receive with patients.

If you’re shopping for insurance, check the coverage for medicines you need

GoodRx says formularies shrank the most before 2020. Lately, they’ve stabilized somewhat.

“It's hopeful to see that things are not getting worse,” GoodRx’s Marsh says. “But I would love to kind of see this chart move in the opposite direction with more drugs covered and fewer of those having restrictions.”

So far, however, she’s never seen drug coverage expand in any of the years of formulary data she’s reviewed.

If consumers want more generous plans, they likely need to shop around and buy them even if it means higher monthly premiums, says Ballreich. But most people just look for a low premium.

“It's incredibly overwhelming,” he says of shopping for health insurance. “And I have a Ph.D. in this.”

- Health Insurance

- Pharmaceuticals

- Open access

- Published: 26 June 2024

Evaluation of nurses’ attitudes and behaviors regarding narcotic drug safety and addiction: a descriptive cross-sectional study

- Ayten Kaya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7684-3675 1 ,

- Zila Özlem Kirbaş ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4030-5442 2 &

- Suhule Tepe Medin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1980-1612 3

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 435 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

114 Accesses

Metrics details

By evaluating nurses’ attitudes and behaviors regarding narcotic drug safety and addiction, effective strategies need to be developed for combating addiction in healthcare institutions. This study, aimed at providing an insight into patient and staff safety issues through the formulation of health policies, aimed to evaluate nurses’ attitudes and behaviors regarding narcotic drug safety and addiction.