- Career Advice

How to Avoid Failing Your Ph.D. Dissertation

By Daniel Sokol

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istock.com/erhui1979

I am a barrister in London who specializes in helping doctoral students who have failed their Ph.D.s. Few people will have had the dubious privilege of seeing as many unsuccessful Ph.D. dissertations and reading as many scathing reports by examination committees. Here are common reasons why students who submit their Ph.D.s fail, with advice on how to avoid such pitfalls. The lessons apply to the United States and the United Kingdom.

Lack of critical reflection. Probably the most common reason for failing a Ph.D. dissertation is a lack of critical analysis. A typical observation of the examination committee is, “The thesis is generally descriptive and a more analytical approach is required.”

For doctoral work, students must engage critically with the subject matter, not just set out what other scholars have said or done. If not, the thesis will not be original. It will not add anything of substance to the field and will fail.

Doctoral students should adopt a reflexive approach to their work. Why have I chosen this methodology? What are the flaws or limitations of this or that author’s argument? Can I make interesting comparisons between this and something else? Those who struggle with this aspect should ask their supervisors for advice on how to inject some analytic sophistication to their thesis.

Lack of coherence. Other common observations are of the type: “The argument running through the thesis needs to be more coherent” or “The thesis is poorly organized and put together without any apparent logic.”

The thesis should be seen as one coherent whole. It cannot be a series of self-contained chapters stitched together haphazardly. Students should spend considerable time at the outset of their dissertation thinking about structure, both at the macro level of the entire thesis and the micro level of the chapter. It is a good idea to look at other Ph.D. theses and monographs to get a sense of what constitutes a logical structure.

Poor presentation. The majority of failed Ph.D. dissertations are sloppily presented. They contain typos, grammatical mistakes, referencing errors and inconsistencies in presentation. Looking at some committee reports randomly, I note the following comments:

- “The thesis is poorly written.”

- “That previous section is long, badly written and lacks structure.”

- “The author cannot formulate his thoughts or explain his reasons. It is very hard to understand a good part of the thesis.”

- “Ensure that the standard of written English is consistent with the standard expected of a Ph.D. thesis.”

- “The language used is simplistic and does not reflect the standard of writing expected at Ph.D. level.”

For committee members, who are paid a fixed and pitiful sum to examine the work, few things are as off-putting as a poorly written dissertation. Errors of language slow the reading speed and can frustrate or irritate committee members. At worst, they can lead them to miss or misinterpret an argument.

Students should consider using a professional proofreader to read the thesis, if permitted by the university’s regulations. But that still is no guarantee of an error-free thesis. Even after the proofreader has returned the manuscript, students should read and reread the work in its entirety.

When I was completing my Ph.D., I read my dissertation so often that the mere sight of it made me nauseous. Each time, I would spot a typo or tweak a sentence, removing a superfluous word or clarifying an ambiguous passage. My meticulous approach was rewarded when one committee member said in the oral examination that it was the best-written dissertation he had ever read. This was nothing to do with skill or an innate writing ability but tedious, repetitive revision.

Failure to make required changes. It is rare for students to fail to obtain their Ph.D. outright at the oral examination. Usually, the student is granted an opportunity to resubmit their dissertation after making corrections.

Students often submit their revised thesis together with a document explaining how they implemented the committee’s recommendations. And they often believe, wrongly, that this document is proof that they have incorporated the requisite changes and that they should be awarded a Ph.D.

In fact, the committee may feel that the changes do not go far enough or that they reveal further misunderstandings or deficiencies. Here are some real observations by dissertation committees:

- “The added discussion section is confusing. The only thing that has improved is the attempt to provide a little more analysis of the experimental data.”

- “The author has tried to address the issues identified by the committee, but there is little improvement in the thesis.”

In short, students who fail their Ph.D. dissertations make changes that are superficial or misconceived. Some revised theses end up worse than the original submission.

Students must incorporate changes in the way that the committee members had in mind. If what is required is unclear, students can usually seek clarification through their supervisors.

In the nine years I have spent helping Ph.D. students with their appeals, I have found that whatever the subject matter of the thesis, the above criticisms appear time and time again in committee reports. They are signs of a poor Ph.D.

Wise students should ask themselves these questions prior to submission of the dissertation:

- Is the work sufficiently critical/analytical, or is it mainly descriptive?

- Is it coherent and well structured?

- Does the thesis look good and read well?

- If a resubmission, have I made the changes that the examination committee had in mind?

Once students are satisfied that the answer to each question is yes, they should ask their supervisors the same questions.

‘Manufacturing Backlash’

To understand the right-wing legislative attacks on higher education, follow the money, Isaac Kamola writes.

Share This Article

More from career advice.

Let’s Finally Tackle the Problem of Pay Inequity

Higher ed must go beyond buzz words and stop hiding behind performative equity, which does not create change, w

The Problem With Participation Grades (and How To Solve It)

The benefits are well documented but the practice can be subjective and prone to instructor biases, warns Anna Broadb

Ensuring International Students’ Career Success

Sherry Wang and Merab Mushfiq offer several strategies to help international students overcome the challenges their N

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Create Free Account

- PhD Failure Rate – A Study of 26,076 PhD Candidates

- Doing a PhD

The PhD failure rate in the UK is 19.5%, with 16.2% of students leaving their PhD programme early, and 3.3% of students failing their viva. 80.5% of all students who enrol onto a PhD programme successfully complete it and are awarded a doctorate.

Introduction

One of the biggest concerns for doctoral students is the ongoing fear of failing their PhD.

After all those years of research, the long days in the lab and the endless nights in the library, it’s no surprise to find many agonising over the possibility of it all being for nothing. While this fear will always exist, it would help you to know how likely failure is, and what you can do to increase your chances of success.

Read on to learn how PhDs can be failed, what the true failure rates are based on an analysis of 26,067 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities, and what your options are if you’re unsuccessful in obtaining your PhD.

Ways You Can Fail A PhD

There are essentially two ways in which you can fail a PhD; non-completion or failing your viva (also known as your thesis defence ).

Non-completion

Non-completion is when a student leaves their PhD programme before having sat their viva examination. Since vivas take place at the end of the PhD journey, typically between the 3rd and 4th year for most full-time programmes, most failed PhDs fall within the ‘non-completion’ category because of the long duration it covers.

There are many reasons why a student may decide to leave a programme early, though these can usually be grouped into two categories:

- Motives – The individual may no longer believe undertaking a PhD is for them. This might be because it isn’t what they had imagined, or they’ve decided on an alternative path.

- Extenuating circumstances – The student may face unforeseen problems beyond their control, such as poor health, bereavement or family difficulties, preventing them from completing their research.

In both cases, a good supervisor will always try their best to help the student continue with their studies. In the former case, this may mean considering alternative research questions or, in the latter case, encouraging you to seek academic support from the university through one of their student care policies.

Besides the student deciding to end their programme early, the university can also make this decision. On these occasions, the student’s supervisor may not believe they’ve made enough progress for the time they’ve been on the project. If the problem can’t be corrected, the supervisor may ask the university to remove the student from the programme.

Failing The Viva

Assuming you make it to the end of your programme, there are still two ways you can be unsuccessful.

The first is an unsatisfactory thesis. For whatever reason, your thesis may be deemed not good enough, lacking originality, reliable data, conclusive findings, or be of poor overall quality. In such cases, your examiners may request an extensive rework of your thesis before agreeing to perform your viva examination. Although this will rarely be the case, it is possible that you may exceed the permissible length of programme registration and if you don’t have valid grounds for an extension, you may not have enough time to be able to sit your viva.

The more common scenario, while still being uncommon itself, is that you sit and fail your viva examination. The examiners may decide that your research project is severely flawed, to the point where it can’t possibly be remedied even with major revisions. This could happen for reasons such as basing your study on an incorrect fundamental assumption; this should not happen however if there is a proper supervisory support system in place.

PhD Failure Rate – UK & EU Statistics

According to 2010-11 data published by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (now replaced by UK Research and Innovation ), 72.9% of students enrolled in a PhD programme in the UK or EU complete their degree within seven years. Following this, 80.5% of PhD students complete their degree within 25 years.

This means that four out of every five students who register onto a PhD programme successfully complete their doctorate.

While a failure rate of one in five students may seem a little high, most of these are those who exit their programme early as opposed to those who fail at the viva stage.

Failing Doesn’t Happen Often

Although a PhD is an independent project, you will be appointed a supervisor to support you. Each university will have its own system for how your supervisor is to support you , but regardless of this, they will all require regular communication between the two of you. This could be in the form of annual reviews, quarterly interim reviews or regular meetings. The majority of students also have a secondary academic supervisor (and in some cases a thesis committee of supervisors); the role of these can vary from having a hands-on role in regular supervision, to being another useful person to bounce ideas off of.

These frequent check-ins are designed to help you stay on track with your project. For example, if any issues are identified, you and your supervisor can discuss how to rectify them in order to refocus your research. This reduces the likelihood of a problem going undetected for several years, only for it to be unearthed after it’s too late to address.

In addition, the thesis you submit to your examiners will likely be your third or fourth iteration, with your supervisor having critiqued each earlier version. As a result, your thesis will typically only be submitted to the examiners after your supervisor approves it; many UK universities require a formal, signed document to be submitted by the primary academic supervisor at the same time as the student submits the thesis, confirming that he or she has approved the submission.

Failed Viva – Outcomes of 26,076 Students

Despite what you may have heard, the failing PhD rate amongst students who sit their viva is low.

This, combined with ongoing guidance from your supervisor, is because vivas don’t have a strict pass/fail outcome. You can find a detailed breakdown of all viva outcomes in our viva guide, but to summarise – the most common outcome will be for you to revise your thesis in accordance with the comments from your examiners and resubmit it.

This means that as long as the review of your thesis and your viva examination uncovers no significant issues, you’re almost certain to be awarded a provisional pass on the basis you make the necessary corrections to your thesis.

To give you an indication of the viva failure rate, we’ve analysed the outcomes of 26,076 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities who sat a viva between 2006 and 2017.

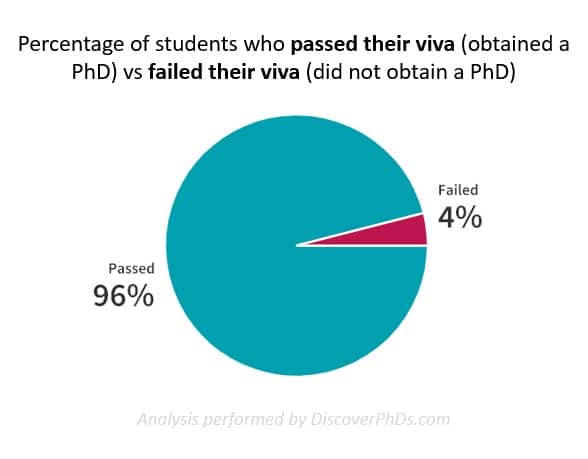

The analysis shows that of the 26,076 students who sat their viva, 25,063 succeeded; this is just over 96% of the total students as shown in the chart below.

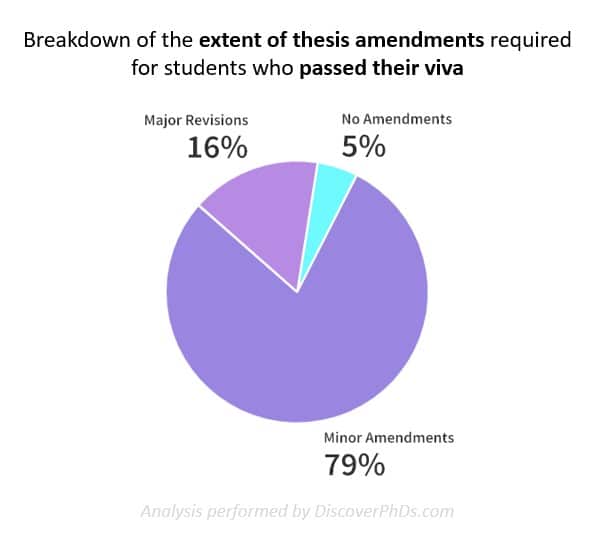

Students Who Passed

The analysis shows that of the 96% of students who passed, approximately 5% required no amendments, 79% required minor amendments and the remaining 16% required major revisions. This supports our earlier discussion on how the most common outcome of a viva is a ‘pass with minor amendments’.

Students Who Failed

Of the 4% of unsuccessful students, approximately 97% were awarded an MPhil (Master of Philosophy), and 3% weren’t awarded a degree.

Note : It should be noted that while the data provides the student’s overall outcome, i.e. whether they passed or failed, they didn’t all provide the students specific outcome, i.e. whether they had to make amendments, or with a failure, whether they were awarded an MPhil. Therefore, while the breakdowns represent the current known data, the exact breakdown may differ.

Summary of Findings

By using our data in combination with the earlier statistic provided by HEFCE, we can gain an overall picture of the PhD journey as summarised in the image below.

To summarise, based on the analysis of 26,076 PhD candidates at 14 universities between 2006 and 2017, the PhD pass rate in the UK is 80.5%. Of the 19.5% of students who fail, 3.3% is attributed to students failing their viva and the remaining 16.2% is attributed to students leaving their programme early.

The above statistics indicate that while 1 in every 5 students fail their PhD, the failure rate for the viva process itself is low. Specifically, only 4% of all students who sit their viva fail; in other words, 96% of the students pass it.

What Are Your Options After an Unsuccessful PhD?

Appeal your outcome.

If you believe you had a valid case, you can try to appeal against your outcome . The appeal process will be different for each university, so ensure you consult the guidelines published by your university before taking any action.

While making an appeal may be an option, it should only be considered if you genuinely believe you have a legitimate case. Most examiners have a lot of experience in assessing PhD candidates and follow strict guidelines when making their decisions. Therefore, your claim for appeal will need to be strong if it is to stand up in front of committee members in the adjudication process.

Downgrade to MPhil

If you are unsuccessful in being awarded a PhD, an MPhil may be awarded instead. For this to happen, your work would need to be considered worthy of an MPhil, as although it is a Master’s degree, it is still an advanced postgraduate research degree.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of stigma around MPhil degrees, with many worrying that it will be seen as a sign of a failed PhD. While not as advanced as a PhD, an MPhil is still an advanced research degree, and being awarded one shows that you’ve successfully carried out an independent research project which is an undertaking to be admired.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Additional Resources

Hopefully now knowing the overall picture your mind will feel slightly more at ease. Regardless, there are several good practices you can adopt to ensure you’re always in the best possible position. The key of these includes developing a good working relationship with your supervisor, working to a project schedule, having your thesis checked by several other academics aside from your supervisor, and thoroughly preparing for your viva examination.

We’ve developed a number of resources which should help you in the above:

- What to Expect from Your Supervisor – Find out what to look for in a Supervisor, how they will typically support you, and how often you should meet with them.

- How to Write a Research Proposal – Find an outline of how you can go about putting a project plan together.

- What is a PhD Viva? – Learn exactly what a viva is, their purpose and what you can expect on the day. We’ve also provided a full breakdown of all the possible outcomes of a viva and tips to help you prepare for your own.

Data for Statistics

- Cardiff University – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- Imperial College London – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- London School of Economics (LSE) – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- Queen Mary University of London – 2009/10 to 2015/16

- University College London (UCL) – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Aberdeen – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Birmingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Bristol – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Edinburgh – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Nottingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Oxford – 2007/08 to 2016/17

- University of York – 2009/10 to 2016/17

- University of Manchester – 2008/09 to 2017/18

- University of Sheffield – 2006/07 to 2016/17

Note : The data used for this analysis was obtained from the above universities under the Freedom of Information Act. As per the Act, the information was provided in such a way that no specific individual can be identified from the data.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Elisa Granato

Microbial ecology & evolution, phd tips – dealing with “failed” experiments.

“PhD tips” is an ongoing series of blog posts written by postdocs and aimed at graduate students at the University of Oxford (Department of Biology). I wrote this in April 2021.

[Update Dec 2022: this article is now published in The Microbiologist ]

Hi everyone!

I hope you are all doing well. This week, I want to talk about dealing with “failed” experiments.* I put “failed” in quotes because, as I will argue below, only a very small fraction of experiments perceived as failed have actually failed in the sense that they were completely pointless.

The first thing to realize is that the core of experimental science is an iterative process: you do a thing, it does something (or not), you think about it, you do it a little different next time. Crucially, this process works the same way whether the results made you happy or not (for whatever reason). You think about what happened, you change stuff, you do it again the same way, you do it again with a twist, or you do something else entirely. A very normal experience as a scientist is to – on average – be a little disappointed in the outcome of your experiment. See below for a list of outcomes that tend to make people unhappy. Again: this is normal and part of the process. The most “successful” projects are built on a foundation of “failed” or semi-failed attempts at doing something.**

The second thing to realize is that learning is at the core of this iterative process: a thing has to happen for us to better understand what we’re dealing with. This means that the essential goal of each experiment is to learn something, anything! And this “lesson” doesn’t usually come in the shape of a perfect plot that’s publication-ready on the first try. Instead, the next learning item usually comes from a mangled mess of an experiment or dataset.

What exactly you are learning from each attempt depends of course on the details of your project, but below I am giving a few real-life examples of typical experimental outcomes that tend to make people unhappy, and some suggestions on what one could learn from them.

- Not failed at all, this is a valuable negative result.

- Outcome: solid scientific insight.

- Not failed at all, this is valuable data we can learn from.

- Potential next step: figure out if noise is biological variance or technical measurement error, or both.

- Outcome: a better understanding of your system, solid scientific insight

- Example: forgot to wash cells before treating them.

- Semi-failed, this is valuable data we can learn from. By comparing the washed cells with the unwashed cells we can learn how this step in the experiment influences the final results. Can be useful for future troubleshooting.

- Outcome: an experimental protocol where we understand better what each step does, or where we realize one step is less important than previously thought; honing of lab skills.

- Example: positive/negative control didn’t yield the expected result, even though it has always worked before and the experiment was (to the best of your knowledge) executed as usual.

- Semi-failed. An opportunity to evaluate the reliability of the protocol/equipment/material.

- Potential next steps: introduce checklists and more note-taking to ensure little details are adhered to; evaluate assumptions e.g. is the control genotype actually this genotype, is something contaminated, is the machine still working, etc.

- Outcome: a more reliable experimental protocol, honing of lab skills

- Example: algae grow over all your aquatic plants and kill them

- Semi-failed. An opportunity to evaluate “housing” conditions for your organism.

- Potential next steps: pilot experiment to optimize housing conditions before doing “actual” experiments; investigate whether the contaminant did something interesting

- Outcome: a more reliable experimental protocol; chance of a random cool discovery with the contaminant

- Example: dropped tube with the sample on the floor. Cannot be recovered.

- Close to “actually failed”, but still an opportunity to introduce better safety measures / risk assessment.

- Potential next steps: introduce safety procedures to ensure better sample preservation, labelling etc.

- Outcome: a more reliable experimental protocol

The third thing to realize is that feelings of frustration, anger, sadness, fear, are all very common in the wake of a “failed” experiment, especially if it took a long time. And trying to think about the next steps while still frustrated can turn into a vicious cycle where you make mistakes because frustrated brains are bad at solving problems. So, instead, allow yourself to feel these feelings, get a good night’s sleep, and then start troubleshooting the next day with a fresh and relaxed mind.

So, to summarize: doing your PhD, and science in general, is about learning. Every experiment, no matter the outcome, can teach you something. Some of the lessons are perhaps a bit more appealing and easier to swallow than others, but they are all useful and necessary. So next time an experiment “fails”, try taking a nice little break if you can, and then list all the things you still learned about your experimental setup, or organism of interest.

Finally, I would like to share a little mental trick I developed over the years that has helped me with dealing and accepting experimental setbacks. I like to imagine that any given project will take me X hours to complete, including setbacks, trials by fire, random distractions, dead-ends etc. In science, X is usually unknown. But importantly, there is always an X. Every time I conduct an experiment that “fails”, and let’s say it took me 6 hours, I have now reduced X by 6 hours. Not bad! I am one step closer to finishing the project. It’s a bit tongue-in-cheek of course, but it still helps me see my work for what it is: I gave these 6 hours my best and the outcome doesn’t change that.

*If you work on theory you can probably replace “failed experiments” here with “theoretical approaches that didn’t work out” or something along those lines and maybe some of this might still be helpful.

**This is the science version of “The master has failed more times than the student has even tried”.

5 ways to fail your PhD

In Australia most theses are examined through blind peer review. Other countries have different ways of doing examination, but in every system judgment of any PhD is the job of a small group of experts. This is an assessment process unlike any other in academe and it pays to make yourself familiar with it.

You’ll be pleased to know that people have spent time studying how examiners read a thesis and what sort of document they expect you to deliver. The seminal paper is “It’s a PhD, not a Nobel Prize: how experience examiners assess research theses” (2002) by Gerry Mullins and Margaret Kiley. I consider this paper required reading for every research student, regardless of their location or discipline. There’s a lot I could say about this paper. In fact I have been talking about this paper for about 5 years in one of my On Track Workshops “What do examiners really want?”, where I spend two hours examining it in detail (there’s sessions coming up next week for students at RMIT – check your email!).

As you can imagine this is one of our more popular sessions, but I must admit I’m beginning to feel like one of those aged rock stars . Although the audience expects it, I don’t want to sing a straight version of my hit wonder from the 1980s. I want to sing songs from my new album. So here I turn around my normal presentation of the paper. If Mullins and Kiley are right about how examiners examine – what are 5 things you could do if you really wanted to fail (or at least be asked to do major revisions)?

1. Don’t talk to your supervisor about who you think should examine your thesis

I am located in the School of Graduate Research, who manage the examination process, so I get to read a lot of examiner reports and see the occasional complaint go by. Far and away the most common complaint is that the examiner didn’t understand what the student was trying to do. Usually this means there’s some kind of disagreement about method and how the student has handled (or not) validity, reliability and so on.

Sometimes supervisors take the confidential nature of the examination process seriously and may brush off your attempts to have a conversation about what sort of people they have in mind. However most universities, including ours, include an option for you to send a list of people who would not be appropriate. In my opinion every student should send a list of inappropriate people to their supervisor – if only for the record.

Just in case ok? Humour me.

2. Send your thesis to someone who has never examined a thesis before

Mullins and Kiley found that even more than methodological orientation, the amount of experience the examiner has matters. This probably makes sense to those of you who teach. Young teachers tend to have high expectations because they haven’t had time to see the full range of student abilities out there. The longer you teach, the more forgiving you become because for every new student you encounter, you have probably seen another who was worse. Some people can be nervous about sending their thesis to the world’s expert in *blah*, but they are exactly the sort of people you should be aiming for.

3. Write your introduction first

One of the most interesting and useful observations Mullins and Kiley made is that most examiners don’t read your thesis like it’s a novel – starting at the beginning and reading through to the end. Shocked? I was the first time I read this, but then I reflected on the last academic book which I read from start to finish… and I couldn’t think of one. Academic texts are dense, difficult, cumbersome beings at the best of times and a thesis is even worse.

Most examiners read the abstract, introduction and the conclusion to see what the work is about and then look in the references, so you should write these last – or rather rewrite them at the end. Any questions you raise in the introduction should be answered in the conclusion. If these parts act as righteous ‘bookends’ the examiner will form a better impression of you as a scholar – and is likely to be more forgiving of you if you slip up a bit in the middle parts.

4. Write a bad literature review

Oh boy. Where do I start? There are so many ways to write a bad literature review that it deserves a few posts on its own. The literature review is the nice party frock of your thesis. If the examiner sees that you have chosen the right frock for the occasion they are more likely to want to have a drink with you. It goes without saying your frock should be freshly ironed and have no stains on it – even better if it matches your handbag and shoes.

The kind of dress you think is appropriate is up to you, but I think you can’t go wrong with a little black dress (LBD). In thesis land the LBD is a simple, but competent run through of the major authors with a thread of an argument running through the whole. The argument should be connected to why you are bothering to do the study. It’s up to you of course, you can be more daring, but I would stop short of trying to be Lady Gaga .

5. Don’t let anyone else do your copy editing

Mullins and Kiley note that across all disciplines examiners report being put off by ‘sloppiness’. Yep – typos, missed footnotes, badly formatted bibliographies and so on. Those of you writing in a different language don’t need to fret too much, there’s evidence to suggest that examiners accommodate idiosyncratic grammar more than plain mess. I’m not sure how much it costs to get a copy editor – but most universities will allow you to employ one under certain guidelines . If not, do a lot of favours for a grammar enabled friend and ask them to perform the duty for you. It’s hard to see the mistakes in your own work on the 700th read

I’d be happy to have a discussion in the comments section about fears and questions relating to examiners and examination – and a special shout out to all the RMIT students due to submit at the end of March!

*Update: Later Mr Thesis Whisperer found another 3 mistakes in this copy, other than intentionally missing full stop. That’s why I made him read my masters thesis 🙂

Related posts

Learning from ‘Avatar’

The ‘It’s time’ talk

The dead hand of the Thesis Genre

Share this:

The Thesis Whisperer is written by Professor Inger Mewburn, director of researcher development at The Australian National University . New posts on the first Wednesday of the month. Subscribe by email below. Visit the About page to find out more about me, my podcasts and books. I'm on most social media platforms as @thesiswhisperer. The best places to talk to me are LinkedIn , Mastodon and Threads.

- Post (606)

- Page (16)

- Product (6)

- Getting things done (258)

- On Writing (138)

- Miscellany (137)

- Your Career (113)

- You and your supervisor (66)

- Writing (48)

- productivity (23)

- consulting (13)

- TWC (13)

- supervision (12)

- 2024 (5)

- 2023 (12)

- 2022 (11)

- 2021 (15)

- 2020 (22)

Whisper to me....

Enter your email address to get posts by email.

Email Address

Sign me up!

- On the reg: a podcast with @jasondowns

- Thesis Whisperer on Facebook

- Thesis Whisperer on Instagram

- Thesis Whisperer on Soundcloud

- Thesis Whisperer on Youtube

- Thesiswhisperer on Mastodon

- Thesiswhisperer page on LinkedIn

- Thesiswhisperer Podcast

- 12,132,388 hits

Discover more from The Thesis Whisperer

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

After horrible 5.5 years completely failed PhD (not even any degree awarded)

Hi, I started my PhD in 2012, on my first day I already got warned to be careful with my supervisor. Having had quite bad supervisors in the past (the ‘fat girls are stupid’ kind and the ‘you aren’t my favourite so I do not help you’ kind) I figured at this stage I’m fine I was well used to it. Now, 1 car crash, bullying, address to the lab withdrawn then lack of results blamed on being stupid, almost 6 years later I suffer from depression, have ongoing nightmares and not even any kind of participation badge for all the time in the lab and- frankly, therapy. I agree that the thesis was bad but I do find it an odd coincidence that I was told I was going to pass, until I filed an academic and dignity complaint against my supervisors (with evidence) and now I am supposed to get more experimental results (without lab access) and am supposed to improve my bad writing... I know I am not stupid but I feel bad I been given the materials, the access and the support that was advertised and had they listened when Initially discussed the lack of biological relevance and scientific depth when I requested a switch from topic- i feel I would have at least gotten an MPhil. After refusing a switch in topic or supervisors because ‘there is no time to get enough results with only 3 years left’ they then switched my topic with only little under 2 years left, which suddenly was more than enough time. At the same time I was told I was useless unless I went part-time but worked on the thesis full-time and came in every weekend (while blocking my out of hours access???) The thesis was bad and I said it from the beginning but was always told I was doing Phantastin with a paper on the way (until the complaint...when oddly suddenly I failed and had tons of obstacles thrown my way) How do I get over this?

You are supposed to get more results, or they have failed you outright? Has this been through the board of examiners? There are still steps you can take to rectify this is you want to. You can appeal the decision, if you have grounds do so, e.g. if there was "material irregularity in the decision making process", such as they didn't follow the procedures properly, or there were errors made, if your performance was affected by something you haven't disclosed or they failed to take account of it properly (maybe the latter in your case?). Seek advice from the Students' Union If you just want to forget it about it, then I suggest getting a change of scene, go on holiday, or go and stay with friends/family somewhere. Time and distance will give you some perspective. Failing that, try some counselling. It does sound like you have had a raw deal here and this should be a lesson to anyone that is thinking about registering a complaint about supervisors - it generally does not have a good outcome and is best left until your certificate is safely in your hand.

Hi, Just finished crying and reading through the notes. I was failed outright (no viva) but was given the option to resubmit in 1 year with a mandatory viva (perfectly fair enough) but they want more data. How can I possibly get more data without access to the laboratory? They blocked my access long before submission, I didn‘t even have library access. Thanks for the student union tip, I have raised that the internal examiner is one of my supervisors closest friends but I am am still shattered. How is one supposed to get good data without laboratory access, out of hour access revoked almost 1 year before writing period started and no access to materials needed for cloning without arguing for weeks? Such a long time, such a long gap in my CV and so much bad treatment all for nothing :(

Hi, Tigernore, You have my sympathy. Working under a bullly supervisor is awful and you have not been given fair treatment. As Tree of Life has advised, seek the Students Union. In fact, see if your Students Union provide legal services. You have nothing to lose anyway, and talking to a lawyer will help you determine if any rules have been broken incl the right access to lab support and material as a student. It will also put pressure on the university as they normally do not want anything that may damage their reputation, especially if they are in the wrong. You may even be able to fight for lab access again and another fair examination of your thesis. Dry your tears. Now is the time for desperate actions and strategy. You must stay strong. What your supervisor and examiners want to do is to force you to give up and walk away, painting you as a bad student. You must not let them win. I speak from my personal experience as I too launched a complain towards my supervisor and the amount of backlash and soft threats (veiled as advice to maintain good relationship with supervisor as I need his letter of support) were terrible. I represented myself at institute level -failed, faculty level -failed and finally University level -success with a detailed portfolio of evidence and cover letter provided with strong support from a lawyer from Students Union. In my case, I had very strong evidence and was advised by my lawyer that if I failed again at university level, I could go to court. Luckily I didn't have to but the experience was traumatic. Every case is different, and I wish you the very best as you fight for yours. Don give up without trying to fight.

I would echo what tru has said as well. This is not over yet if you don't want it to be. They have to give you lab access if they are asking for more results. Cutting your access to things doesn't seem fair - you should check if this happens to all students in your department - if doesn't, you have a massive case for mistreatment because they have been setting you up to fail. Who has signed off on this decision? Examiners? Head of postgrads? Head of School? Faculty Dean? Take up to a higher level if needed. Don't cry about this, get angry instead. Channel that anger into getting the access and then the results you need to get this PhD.

Hi, I know of multiple students having had ...let's say issues in my department. Including sexual harrassment and when filed being threatened with losing the degree, having no right to holidays and having the same issue I have of being told to go part-time (including part-time stipend) but working full-time in the lab-which most cannot afford. I just can't seem to get heard, everyone is just saying, well let it go they have the power etc. And without access to labs like you agree I can't get anywhere and I don't even have a supervisor / academic tutor at this point. I am filing my appeal over this week and requesting await of the complaint process and readjustment of my access. It is impossible to salvage this into a PhD with what happened but at least an MPhil would have been nice. Thanks for your messages!!!

Quote From Tigernore: Hi, I know of multiple students having had ...let's say issues in my department. Including sexual harrassment and when filed being threatened with losing the degree, having no right to holidays and having the same issue I have of being told to go part-time (including part-time stipend) but working full-time in the lab-which most cannot afford. I just can't seem to get heard, everyone is just saying, well let it go they have the power etc. And without access to labs like you agree I can't get anywhere and I don't even have a supervisor / academic tutor at this point. I am filing my appeal over this week and requesting await of the complaint process and readjustment of my access. It is impossible to salvage this into a PhD with what happened but at least an MPhil would have been nice. Thanks for your messages!!! Ah, the usual discouragement.. "Let go because you can't win.. Why bother since your supervisors have power..." Haven't we all heard of that before... This is the phsycological game to break the student's spirit and rid "troublemakers".. Don't give in. Tigernore, steel yourself. You have not been given a fair fighting chance, and you know it. Instead of talking to nonsense people who are out to discourage you (probably other academics who may or may not have ties with your uni and supervisor), talk to your Student Union who is supposed to defend you. Talk to a legal representative from your Student Union. Fight for your PhD... All is not lost unless you give up on yourself. All the best in your appeal, and don't walk away without exhausting all avenues.

I agree with Tru, I am going through a fight of my own at the moment and experienced the psychological games. I am very much on my own and have been working without supervision for 6 months now, I am almost 12 months in. Having no supervision is better than the situation I was in, but it can't continue for long this way, so I am hoping for a resolution soon. Dragging things out seems to be another way of trying to get rid of any student who speaks out. I have a strong case and its sounds like you have also, so as Tru also says don't give in. My SU haven't been any help, they often don't respond and don't seem to know processes well. Your SU may be better so I advise speaking to them. I struggled getting heard also, my department seemingly didn't want to know, so it had to go formal. I also have/had a supervisor you have to be careful with and my project was changed after I started. So I sympathise with your situation. I see many similarities on this forum among experiences students have concerning supervisor issues and how Universities respond to such cases.

Post your reply

Postgraduate Forum

Masters Degrees

PhD Opportunities

Postgraduate Forum Copyright ©2024 All rights reserved

PostgraduateForum Is a trading name of FindAUniversity Ltd FindAUniversity Ltd, 77 Sidney St, Sheffield, S1 4RG, UK. Tel +44 (0) 114 268 4940 Fax: +44 (0) 114 268 5766

Welcome to the world's leading Postgraduate Forum

An active and supportive community.

Support and advice from your peers.

Your postgraduate questions answered.

Use your experience to help others.

Sign Up to Postgraduate Forum

Enter your email address below to get started with your forum account

Login to your account

Enter your username below to login to your account

Reset password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password

An email has been sent to your email account along with instructions on how to reset your password. If you do not recieve your email, or have any futher problems accessing your account, then please contact our customer support.

or continue as guest

Postgrad Forum uses cookies to create a better experience for you

To ensure all features on our website work properly, your computer, tablet or mobile needs to accept cookies. Our cookies don’t store your personal information, but provide us with anonymous information about use of the website and help us recognise you so we can offer you services more relevant to you. For more information please read our privacy policy

Dissertation Genius

The Six Laws of PhD Failure

September 9, 2019 by Dissertation Genius

To give you a dose of reality, the attrition rate at any PhD school is very high. Anywhere from a third to half of those that enroll at a PhD university will not end up graduating and finishing their dissertation. In fact, the figure of 40%-50% of failing PhD students has been fairly stable over the past three decades. In 1990, Baird reported that PhD completion rates in most disciplines hover around 50% and are even lower in the arts and humanities. In 2003, Elgar conducted a detailed study of North American PhD students and found that “only about half of all students who enter PhD programs…actually complete” (p. iii). The Higher Education Funding Council (HEFCE) for England also reported similar numbers in 2007.

Based on my two decades experience in PhD dissertation consulting, this 50% failure rate is a real number; and the attrition rate for PhD and dissertation students has always been extremely high especially when compared to undergrad and master’s programs. The reason has to do with many factors but, in this article, I’d like to focus on the negative factors that will prevent you from PhD graduation. Towards this end, I’ve inserted what I think are the six most relevant factors correlated to failing PhD students.

1st Law of PhD Failure – Choosing the wrong dissertation adviser

Choosing your dissertation adviser is one of the most important decisions of your academic career and one recipe for disaster is to choose a dissertation adviser because you ‘like’ him or her or because you find this person ‘cool’ meaning charismatic, well-published, and has similar research interests as yourself. While these characteristics are admirable, in the end, they won’t help you in completing a quality dissertation and acquiring your PhD.

Lunenberg and Irby (2008) completed a masterly work about successful dissertation writing and, in chapter two of this work, they mention the key factors in choosing a dissertation adviser. The most important two factors they mention are:

- Accessibility

- Feedback turnaround times

Too many doctoral students fail to take these factors into account when choosing their dissertation adviser even though these two things are the most common source of complaints regarding dissertation advisers.

You must make sure your potential dissertation adviser satisfies these two criteria and that you are clear about whether your potential candidate will satisfy your expectations in these areas. You should also ask colleagues about the dependability of the candidate in the aforementioned areas to make sure you are choosing a suitable candidate that will give a realistic amount of his or her time to hear you out and attend to your dissertation needs (to the extent appropriate for a doctoral student).

2nd Law of PhD Failure – Expecting Dissertation Hand-holding from your Peers

Too many new doctoral students hold mistaken expectations of what they will find in postgraduate school and among these mistaken assumptions is expecting lots of help and hand-holding. As a doctoral student, you should clearly understand that you must take charge of your own doctoral program.

Although you should get help from your dissertation supervisor, chair, and committee members at certain times, you are the person that will make it happen. For example, there will be no one to remind you of certain courses you should enroll in, or particular forms you need to complete by a certain deadline. Only you are responsible for engraving your intellectual path. And under no circumstances should you ever expect your dissertation supervisor, or anyone else for that matter, in holding your hand and telling you which literature to read, which journals to subscribe to, which peer groups and seminars to attend, or which grants and funding to apply for.

While you should seek help and guidance, you should not expect this help to come, and you must develop an independent and persevering mindset in doctoral school, or else you risk a huge disappointment.

3rd Law of PhD Failure – Choosing too Broad a Dissertation Topic

Doctoral students should understand that when it comes to doctoral school and acquiring that PhD, the dissertation is everything. Because most doctoral students understand this, they unfortunately bring with them the mistaken impression that their dissertation should include everything, cover everything, and attack the topic from every conceivable angle using a variety of different research methodologies.

This mindset and mistaken assumption is absolutely wrong. You must narrow down your research topic and zone in on a particular area. Too many doctoral students end up having a broad research topic and realize too late that they have bit off way more than they could chew and taken on much more than they have anticipated.

Here, make sure you work closely with your dissertation adviser and chairperson and keep working on narrowing down your topic appropriately. You may have always dreamt of your dissertation being all-inclusive and having an immediate impact on your field but you must realize that this is near impossible with the normal resources a typical doctoral student has at his or her disposal. Therefore, make your mark by working with the resources you have and beware of defining a research topic that is too broad.

4th Law of PhD Failure – Procrastination

I am not talking about lazy students since this law doesn’t apply to them (laziness is not usually a personality trait for those enrolling in doctoral school). In fact, this particular law applies to the typical doctoral student who is usually a perfectionist that sets very high standards.

“Understand: obsessive perfectionists, aka doctoral students, tend to be procrastinators!”

In general, PhD and doctoral students got to where they are by being obsessive perfectionists (to a certain extent), setting the standard extremely high and working to get near-perfect grades and submissions. This is fine in high doses up to the point of getting into doctoral school, where your dissertation (not your gpa) defines your success. And a doctoral dissertation reflects more the realities of life where you will stumble several times and find yourself doubting your abilities at many points, no matter how smart you think you are . Therefore, many doctoral students are not used to facing massive obstacles and perplexing problems in their academic life. And when finally facing them, most doctoral students tend to turn inward and face away, rather than confronting, these problems. They simply tend to procrastinate as a method of coping with something they are not used to.

To eliminate this idea, understand that life, real life, is not like school. It is filled with perplexing problems, challenges, and many obstacles. To succeed in anything you do, you must face down these problems and simply start by not running away or putting things off because you subconsciously find it easier on your ego to do so.

5th Law of PhD Failure – Ignoring your Dissertation Committee

Yes, you did not read this wrong. Many PhD students nowadays seem to forget that their committee must sign off and approve of their dissertation in order to graduate. Many doctoral students tend to forget the importance of the dissertation committee and forget to maintain contact with committee members, especially in the latter stages of a dissertation. It’s also very easy for doctoral students to forget particular pieces of advice that a committee member has given since the presence of a committee member is not as dominating as that of a dissertation adviser. On the flip side of this, committee members rarely forget the dissertation advice they give to students.

Hopefully it doesn’t happen to you, but many dissertation committee members give advice during the proposal stage of a student’s dissertation only to have this advice ignored or forgotten by the students. Once it comes time for the thesis defense, the committee members will bring up the unfollowed advice and, many times, it becomes a problem for doctoral students who have to postpone their PhD graduation by a semester (if one is lucky) or more. Don’t let this happen to you and make sure you are in periodic contact with your dissertation committee members and also make sure you record, and follow , any advice given by them.

6th Law of PhD Failure – Getting Romantically Involved with Faculty Members

Although this issue is rarely discussed in online dissertation consulting and writing forums, doctoral students and academic faculty members may become romantically involved. Keep in mind I am not talking about sexual harassment or assault, but rather about completely consensual relationships. Although one may be tempted to think a relationship between two fully-grown adults is not anyone’s business, the reality is that the power dynamics involved in such a relationship are not usually conducive in the long run since the faculty member usually has much more formal and informal power over the doctoral student. Thus, even in seemingly consensual relationships, moral questions of how much the student’s free will was actually involved do arise (e.g. how free was the student to actually decline the relationship). The problem is even more serious if it involves a dissertation adviser or committee member sleeping with a student. Although there are cases of successful long-term faculty-member and student relationships, in my experience these are few and far between. Moreover, what may look like a serious caring relationship could actually be a pattern on the part of the faculty member in ‘cycling’ through impressionable or vulnerable students.

Regardless of the situation, you should simply keep in mind to be careful and keep your guard up. Finally, understand that if things go wrong in the relationship, it could become a serious impediment to success. Moreover, even with successful relationships, your academic success may be hindered by reports of gossip and peers linking any progress of your work to the relationship itself rather than to your own hard work. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

Baird, L.L. (1990). Disciplines and doctorates: The relationship between program characteristics and the duration of doctoral study. Research in Higher Education, 31, 369-385.

Elgar, F. J. (2003). Phd completion in Canadian universities: Final report . Retrieved from Graduate Student’s Association of Canada website: http://careerchem.com/CAREER-INFO-ACADEMIC/Frank-Elgar.pdf

HEFCE. (2007). Phd research degrees: Update . Retrieved from Higher Education Funding Council for England website: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100202100434/http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/hefce/2007/07_28/07_28.pdf

Lunenburg, F. C., & Irby, B. J. (2008). Writing a successful thesis or

dissertation: Tips and strategies for students in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Schedule a Free Consultation

- Email * Enter Email Confirm Email

- What services are you interested in? Dissertation Assistance Dissertation Defense Preparation Dissertation Writing Coaching APA and Academic Editing Literature Review Assistance Concept Paper Assistance Methodology Assistance Qualitative Analysis Quantitative Analysis Statistical Power Analysis Masters Thesis Assistance

- Yes, please.

- No, thank you.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

535 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor New York, NY 10017

Free consultation: (877) 875-7687

- Testimonials

- What is a PhD?

Written by Mark Bennett

A PhD is a doctoral research degree and the highest level of academic qualification you can achieve. The degree normally takes between three and four years of full-time work towards a thesis offering an original contribution to your subject.

This page explains what a PhD is, what it involves and what you need to know if you’re considering applying for a PhD research project , or enrolling on a doctoral programme .

The meaning of a PhD

The PhD can take on something of a mythic status. Are they only for geniuses? Do you have to discover something incredible? Does the qualification make you an academic? And are higher research degrees just for people who want to be academics?

Even the full title, ‘Doctor of Philosophy’, has a somewhat mysterious ring to it. Do you become a doctor? Yes, but not that kind of doctor. Do you have to study Philosophy? No (not unless you want to) .

So, before going any further, let's explain what the term 'PhD' actually means and what defines a doctorate.

What does PhD stand for?

PhD stands for Doctor of Philosophy. This is one of the highest level academic degrees that can be awarded. PhD is an abbreviation of the Latin term (Ph)ilosophiae (D)octor. Traditionally the term ‘philosophy’ does not refer to the subject but its original Greek meaning which roughly translates to ‘lover of wisdom’.

What is a doctorate?

A doctorate is any qualification that awards a doctoral degree. In order to qualify for one you need to produce advanced work that makes a significant new contribution to knowledge in your field. Doing so earns you the title 'Doctor' – hence the name.

So, is a PhD different to a doctorate? No. A PhD is a type of doctorate .

The PhD is the most common type of doctorate and is awarded in almost all subjects at universities around the world. Other doctorates tend to be more specialised or for more practical and professional projects.

Essentially, all PhDs are doctorates, but not all doctorates are PhDs.

Do you need a Masters to get a PhD?

Not necessarily. It's common for students in Arts and the Humanities to complete an MA (Master of Arts) before starting a PhD in order to acquire research experience and techniques. Students in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) don't always need an MS/MSc (Master of Science) to do a PhD as you'll gain training in lab techniques and other skills during your undergraduate degree.

Whether a Masters is a requirement for a PhD also varies by country. Australian PhDs may require a Masters as the equivalent of their own 'honours year' (where students work on research). US PhD programmes often include a Masters.

We have a whole guide dedicated to helping you decide whether a PhD without a Masters is the right route for you.

The origin of the PhD

Despite its name, the PhD isn't actually an Ancient Greek degree. Instead it's a much more recent development. The PhD as we know it was developed in nineteenth-century Germany, alongside the modern research university.

Higher education had traditionally focussed on mastery of an existing body of scholarship and the highest academic rank available was, appropriately enough, a Masters degree.

As the focus shifted more onto the production of new knowledge and ideas, the PhD degree was brought in to recognise those who demonstrated the necessary skills and expertise.

The PhD process – what's required to get a PhD?

The typical length of a PhD is three to four years full-time, or five to six years part-time.

Unlike most Masters courses (or all undergraduate programmes), a PhD is a pure research degree. But that doesn’t mean you’ll just spend years locked away in a library or laboratory. In fact, the modern PhD is a diverse and varied qualification with many different components.

Whereas the second or third year of a taught degree look quite a lot like the first (with more modules and coursework at a higher level) a PhD moves through a series of stages.

A typical PhD normally involves:

- Carrying out a literature review (a survey of current scholarship in your field).

- Conducting original research and collecting your results .

- Producing a thesis that presents your conclusions.

- Writing up your thesis and submitting it as a dissertation .

- Defending your thesis in an oral viva voce exam.

These stages vary a little between subjects and universities, but they tend to fall into the same sequence over the three years of a typical full-time PhD.

The first year of a PhD

The beginning of a PhD is all about finding your feet as a researcher and getting a solid grounding in the current scholarship that relates to your topic.

You’ll have initial meetings with your supervisor and discuss a plan of action based on your research proposal.

The first step in this will almost certainly be carrying out your literature review . With the guidance of your supervisor you’ll begin surveying and evaluating existing scholarship. This will help situate your research and ensure your work is original.

Your literature review will provide a logical jumping off point for the beginning of your own research and the gathering of results . This could involve designing and implementing experiments, or getting stuck into a pile of primary sources.

The year may end with an MPhil upgrade . This occurs when PhD students are initially registered for an MPhil degree and then ‘upgraded’ to PhD candidates upon making sufficient progress. You’ll submit material from your literature review, or a draft of your research findings and discuss these with members of your department in an upgrade exam . All being well, you’ll then continue with your research as a PhD student.

PhDs in other countries

The information on the page is based on the UK. Most countries follow a similar format, but there are some differences. In the USA , for example, PhD students complete reading assignments and examinations before beginning their research. You can find out more in our guides to PhD study around the world .

The second year of a PhD

Your second year will probably be when you do most of your core research. The process for this will vary depending on your field, but your main focus will be on gathering results from experiments, archival research, surveys or other means.

As your research develops, so will the thesis (or argument) you base upon it. You may even begin writing up chapters or other pieces that will eventually form part of your dissertation .

You’ll still be having regular meetings with your supervisor. They’ll check your progress, provide feedback on your ideas and probably read any drafts your produce.

The second year is also an important stage for your development as a scholar. You’ll be well versed in current research and have begun to collect some important data or develop insights of your own. But you won’t yet be faced with the demanding and time-intensive task of finalising your dissertation.

So, this part of your PhD is a perfect time to think about presenting your work at academic conferences , gaining teaching experience or perhaps even selecting some material for publication in an academic journal. You can read more about these kinds of activities below.

The third year of a PhD

The third year of a PhD is sometimes referred to as the writing up phase.

Traditionally, this is the final part of your doctorate, during which your main task will be pulling together your results and honing your thesis into a dissertation .

In reality, it’s not always as simple as that.

It’s not uncommon for final year PhD students to still be fine-tuning experiments, collecting results or chasing up a few extra sources. This is particularly likely if you spend part of your second year focussing on professional development.

In fact, some students actually take all or part of a fourth year to finalise their dissertation. Whether you are able to do this will depend on the terms of your enrolment – and perhaps your PhD funding .

Eventually though, you are going to be faced with writing up your thesis and submitting your dissertation.

Your supervisor will be very involved in this process. They’ll read through your final draft and let you know when they think your PhD is ready for submission.

All that’s left then is your final viva voce oral exam. This is a formal discussion and defence of your thesis involving at least one internal and external examiner. It’s normally the only assessment procedure for a PhD. Once you’ve passed, you’ve done it!

Looking for more information about the stages of a PhD?

How do you go about completing a literature review? What's it like to do PhD research? And what actually happens at an MPhil upgrade? You can find out more in our detailed guide to the PhD journey .

Doing a PhD – what's it actually like?

You can think of the ‘stages’ outlined above as the basic ‘roadmap’ for a PhD, but the actual ‘journey’ you’ll take as a research student involves a lot of other sights, a few optional destinations and at least one very important fellow passenger.

Carrying out research

Unsurprisingly, you’ll spend most of your time as a PhD researcher… researching your PhD. But this can involve a surprisingly wide range of activities.

The classic image of a student working away in the lab, or sitting with a pile of books in the library is true some of the time – particularly when you’re monitoring experiments or conducting your literature review.

Your PhD can take you much further afield though. You may find yourself visiting archives or facilities to examine their data or look at rare source materials. You could even have the opportunity to spend an extended period ‘in residence’ at a research centre or other institution beyond your university.

Research is also far from being a solitary activity. You’ll have regular discussions with your supervisor (see below) but you may also work with other students from time to time.

This is particularly likely if you’re part of a larger laboratory or workshop group studying the same broad area. But it’s also common to collaborate with students whose projects are more individual. You might work on shorter projects of joint interest, or be part of teams organising events and presentations.

Many universities also run regular internal presentation and discussion groups – a perfect way to get to know other PhD students in your department and offer feedback on each other’s work in progress.

Working with your supervisor

All PhD projects are completed with the guidance of at least one academic supervisor . They will be your main point of contact and support throughout the PhD.

Your supervisor will be an expert in your general area of research, but they won’t have researched on your exact topic before (if they had, your project wouldn’t be original enough for a PhD).

As such, it’s better to think of your supervisor as a mentor, rather than a teacher.

As a PhD student you’re now an independent and original scholar, pushing the boundaries of your field beyond what is currently known (and taught) about it. You’re doing all of this for the first time, of course. But your supervisor isn’t.

They’ll know what’s involved in managing an advanced research project over three years (or more). They’ll know how best to succeed, but they’ll also know what can go wrong and how to spot the warning signs before it does.

Perhaps most importantly, they’ll be someone with the time and expertise to listen to your ideas and help provide feedback and encouragement as you develop your thesis.

Exact supervision arrangements vary between universities and between projects:

- In Science and Technology projects it’s common for a supervisor to be the lead investigator on a wider research project, with responsibility for a laboratory or workshop that includes several PhD students and other researchers.

- In Arts and Humanities subjects, a supervisor’s research is more separate from their students’. They may supervise more than one PhD at a time, but each project is essentially separate.

It’s also becoming increasingly common for PhD students to have two (or more) supervisors. The first is usually responsible for guiding your academic research whilst the second is more concerned with the administration of your PhD – ensuring you complete any necessary training and stay on track with your project’s timetable.

However you’re supervised, you’ll have regular meetings to discuss work and check your progress. Your supervisor will also provide feedback on work during your PhD and will play an important role as you near completion: reading your final dissertation draft, helping you select an external examiner and (hopefully) taking you out for a celebratory drink afterwards!

Professional development, networking and communication

Traditionally, the PhD has been viewed as a training process, preparing students for careers in academic research.

As such, it often includes opportunities to pick up additional skills and experiences that are an important part of a scholarly CV. Academics don’t just do research after all. They also teach students, administrate departments – and supervise PhDs.

The modern PhD is also viewed as a more flexible qualification. Not all doctoral graduates end up working in higher education. Many follow alternative careers that are either related to their subject of specialism or draw upon the advanced research skills their PhD has developed.

PhD programmes have begun to reflect this. Many now emphasise transferrable skills or include specific training units designed to help students communicate and apply their research beyond the university.

What all of this means is that very few PhD experiences are just about researching and writing up a thesis.

The likelihood is that you’ll also do some (or all) of the following during your PhD:

The work is usually paid and is increasingly accompanied by formal training and evaluation.

Conference presentation

As a PhD student you’ll be at the cutting edge of your field, doing original research and producing new results. This means that your work will be interest to other scholars and that your results could be worth presenting at academic conferences .

Doing this is very worthwhile, whatever your career plans. You’ll develop transferrable skills in public speaking and presenting, gain feedback on your results and begin to be recognised as an expert in your area.

Conferences are also great places to network with other students and academics.

Publication

As well as presenting your research, you may also have the opportunity to publish work in academic journals, books, or other media. This can be a challenging process.

Your work will be judged according to the same high standards as any other scholar’s and will normally go through extensive peer review processes. But it’s also highly rewarding. Seeing your work ‘in print’ is an incredible validation of your PhD research and a definite boost to your academic CV.

Public engagement and communication

Academic work may be associated with the myth of the ‘ivory tower’ – an insular community of experts focussing on obscure topics of little interest outside the university. But this is far from the case. More and more emphasis is being placed on the ‘impact’ of research and its wider benefits to the public – with funding decisions being made accordingly.

Thankfully, there are plenty of opportunities to try your hand at public engagement as a PhD student. Universities are often involved in local events and initiatives to communicate the benefits of their research, ranging from workshops in local schools to public lectures and presentations.

Some PhD programmes include structured training in order to help students with activities such as the above. Your supervisor may also be able to help by identifying suitable conferences and public engagement opportunities, or by involving you in appropriate university events and public engagement initiatives.

These experiences will be an important part of your development as a researchers - and will enhance the value of your PhD regardless of your career plans.

What is a PhD for – and who should study one?

So, you know what a PhD actually is, what’s involved in completing one and what you might get up to whilst you do. That just leaves one final question: should you do a PhD?

Unfortunately, it’s not a question we can answer for you.

A PhD is difficult and uniquely challenging. It requires at least three years of hard work and dedication after you’ve already completed an undergraduate degree (and probably a Masters degree too).

You’ll need to support yourself during those years and, whilst you will be building up an impressive set of skills, you won’t be directly progressing in a career.

But a PhD is also immensely rewarding. It’s your chance to make a genuine contribution to the sum of human knowledge and produce work that other researchers can (and will) build on in future. However obscure your topic feels, there’s really no such thing as a useless PhD.

A PhD is also something to be incredibly proud of. A proportionately tiny number of people go on to do academic work at this level. Whatever you end up doing after your doctorate you’ll have an impressive qualification – and a title to match. What’s more, non-academic careers and professions are increasingly recognising the unique skills and experience a PhD brings.

Other PhDs - do degree titles matter?

The PhD is the oldest and most common form of higher research degree, but a few alternatives are available. Some, such as the DPhil are essentially identical to a PhD. Others, such as the Professional Doctorate or DBA are slightly different. You can find out more in our guide to types of PhD .

Is a PhD for me?

There’s more advice on the value of a PhD – and good reasons for studying one – elsewhere in this section. But the following are some quick tips if you’re just beginning to consider a PhD.

Speak to your lecturers / tutors

The best people to ask about PhD study are people who’ve earned one. Ask staff at your current or previous university about their experience of doctoral research – what they enjoyed, what they didn’t and what their tips might be.

If you’re considering a PhD for an academic career, ask about that too. Are job prospects good in your field? And what’s it really like to work at a university?

Speak to current PhD students

Want to know what it’s like studying a PhD right now? Or what it’s like doing research at a particular university? Ask someone who knows.

Current PhD students were just like you a year or two ago and most will be happy to answer questions.

If you can’t get in touch with any students ‘face to face’, pop over to the Postgraduate Forum – you’ll find plenty of students there who are happy to chat about postgraduate research.

Take a look at advertised projects and programmes

This may seem like a strange suggestion. After all, you’re only going to study one PhD, so what’s the point of reading about lots of others?

Well, looking at the details of different PhD projects is a great way to get a general sense of what PhD research is like. You’ll see what different PhDs tend to have in common and what kinds of unique opportunity might be available to you.

And, with thousands of PhDs in our database , you’re already in a great place to start.

Read our other advice articles

Finally, you can also check out some of the other advice on the FindAPhD website. We’ve looked at some good (and bad) reasons for studying a PhD as well as the value of a doctorate to different career paths.

More generally, you can read our in-depth look at a typical PhD journey , or find out more about specific aspects of doctoral study such as working with a supervisor or writing your dissertation .

We add new articles all the time – the best way to stay up to date is by signing up for our free PhD opportunity newsletter .

Ready to find your PhD?

Head on over to our PhD search listings to learn what opportunities are on offer within your discipline.

Our postgrad newsletter shares courses, funding news, stories and advice

You may also like....