IDR Explains | Local government in India

In five questions, get an introduction to local government in india—what it is, its structure, functions, sources of funding, and some of the challenges it faces..

What is local government and why is it important?

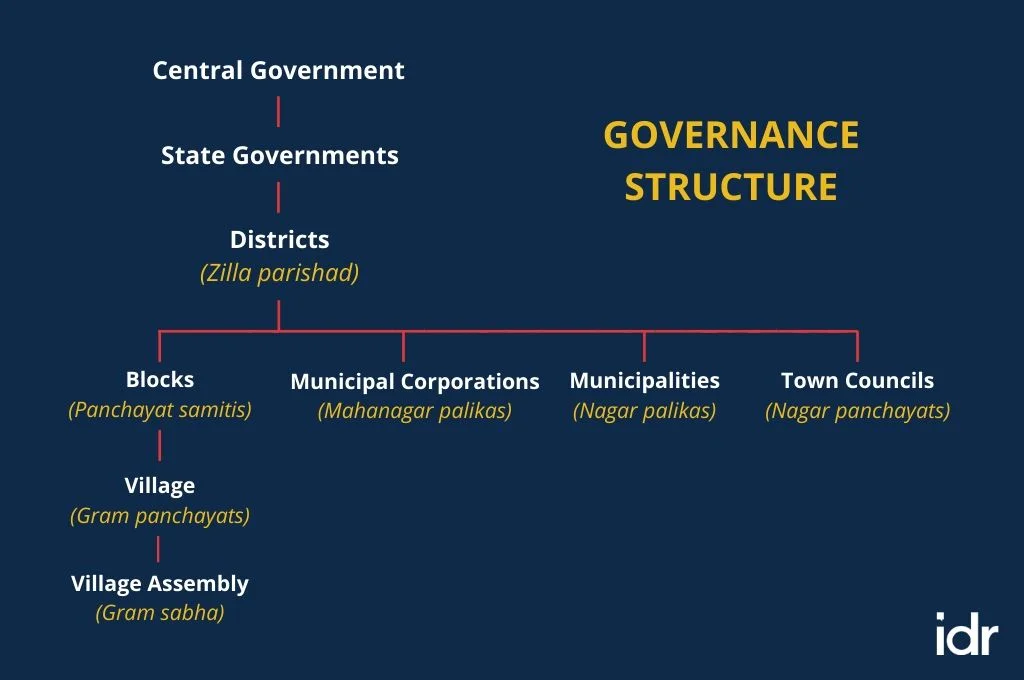

Since the late 1980s, we have been witnessing a wave of decentralisation globally, which is founded upon the idea of making governance more participatory and inclusive. In 1992, India too embraced this wave and amended its constitution with the intent to strengthen grassroots-level democracy by decentralising governance and empowering local political bodies.The objective was to create local institutions that were democratic, autonomous, financially strong, and capable of formulating and implementing plans for their respective areas and providing decentralised administration to the people. It is based on the notion that people need to have a say in decisions that affect their lives and local problems are best solved by local solutions.Though traditional forms of local governance have existed in India for centuries, the post-Independence period saw a shift towards building a system of local government, in no small part due to the influence of Mahatma Gandhi. The passing of the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments , made it mandatory for each state to constitute rural and urban local governments, to establish mechanisms to fund them, and to carry out local elections every five years. The creation of this new three-tier system of local governance provided constitutional status to rural and urban local bodies, ensuring a degree of uniformity in their structure and functioning across the country. Provisions of these two amendments are similar in many ways, and differ mainly in the fact that the former applies to rural local government (also known as Panchayati Raj Institutions or PRIs), while the latter applies to urban local bodies.Currently, there are more than 250,000 local government bodies across India with nearly 3.1 million elected representatives and 1.3 million women representatives.

How is the system structured?

What are the functions of local government in India?

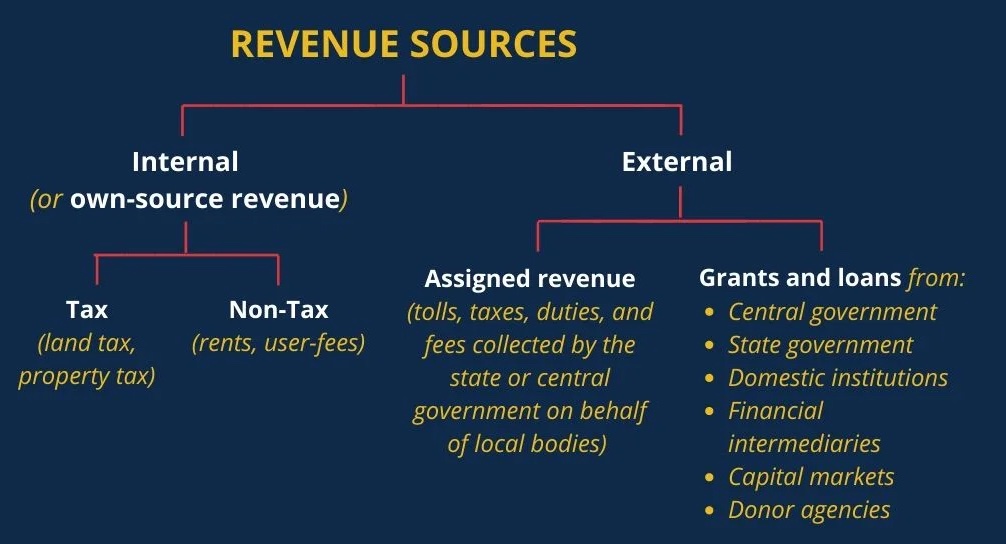

How are local bodies funded?

What are some of the challenges faced by local government bodies?

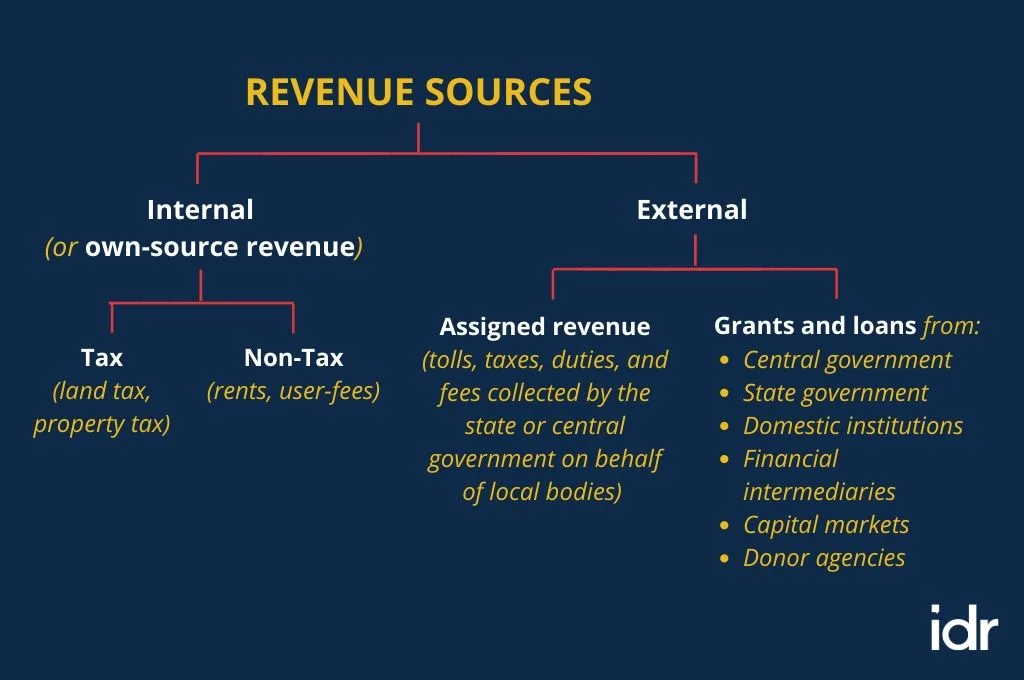

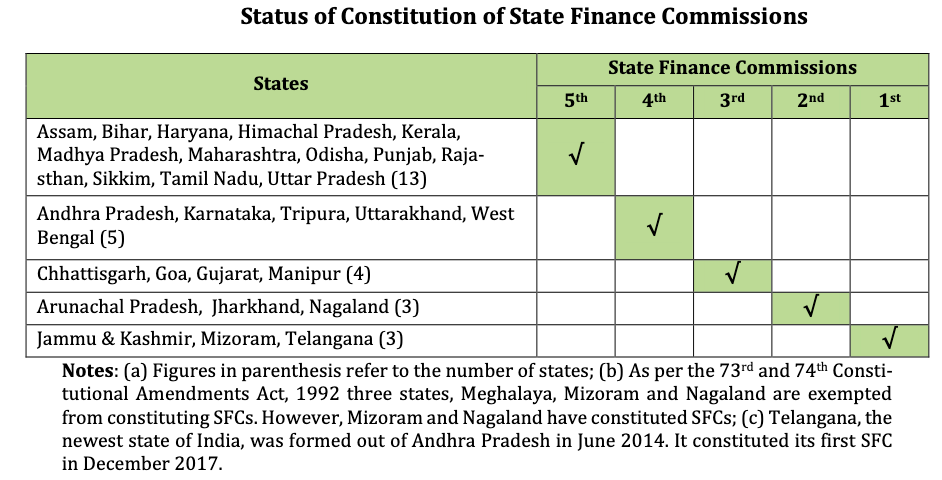

In India, though political decentralisation has been successfully achieved through the establishment of local government bodies, the actual transfer of functions, finances, and functionaries to these institutions remains incomplete. This weakens the system and inhibits its proper functioning.A Devolution Report , published by the Ministry of Panchayati Raj in 2015-2016 estimates the extent to which states have devolved functions, finances, and functionaries. It concludes that while certain states such as Kerala, Karnataka, and Maharashtra have transferred relatively more power to local bodies, real decentralisation has a long way to go in India. Functional challenges: The power to devolve functions to local governments rests with the state government. For a variety of reasons, states do not devolve adequate functions to local government bodies, severely affecting the system’s efficiency and effectiveness. For instance, state governments have been known to create parallel structures for the implementation of projects around agriculture, health, and education—undermining areas for which local bodies are constitutionally responsible.Additionally, many local bodies lack the support systems necessary to carry out their mandates. The 74th amendment requires a District Planning Committee to be set up in each district, so that the development plans prepared by the panchayats and urban local bodies can be consolidated and integrated. However, it was seen that District Planning Committees are non-functional in nine states, and failed to prepare integrated plans in 15 states. Financial challenges: Devolving functions is meaningless without providing adequate funds to carry out said functions. After nearly 25 years of decentralisation, local government expenditure as a percentage of GDP is only two percent—a number that is extremely low when compared to other major emerging economies such as China (11 percent) and Brazil (seven percent).Most local bodies, both rural and urban are unable to generate adequate funds from their internal sources, and are therefore extremely dependent on external sources for funding. Studies show that around 80 percent to 95 percent of revenue is obtained from external sources, particularly state and central government loans and grants.There are two main reasons for low internal revenue collection:- Local bodies may lack the capacity to properly impose taxes, due to ambiguous taxation norms, lack of reliable records, and so on.- State governments have not devolved enough taxation powers. Most states only permit local bodies to collect property taxes and water tariffs, but not land tax or tolls, which can provide more substantial revenues. Functionary challenges: The capacity of local bodies to carry out their mandate is often circumscribed by the state government officials. Additionally, the secretariats of local governments are grossly under-staffed and under-skilled, and therefore unable to provide the required support to the elected body. Their capacities need to be further strengthened through training of existing personnel and the recruitment of new staff. Though local bodies are authorised to recruit staff, this is prevented by limited funding.India’s local governance system needs to be empowered in all three areas to ensure that power truly rests with the people, not just on paper, but also in practice.

Tanaya Jagtiani contributed to this article, with inputs and insights from Dr Shankara Prasad , Sonali Srivastava , Jyothsna Devi , Ila Reddy , and Anant Maringanti .

- Explore the government’s India Panchayat Knowledge Portal —a one-stop repository for everything you need to know about rural local governance in India.

- Listen to ‘The Seen and the Unseen’ podcast, which discusses the importance of cities , the state of urban governance in India , and how urban governance can be reformed .

- Learn more about how urban governance , democratic local governance , and the Panchayati Raj Institutions work in practice through PRIA’s Knowledge Resource Centre .

- Dip in to Praja’s research carried out across two years and 21 states, to understand the challenges in the implementation of the 74th amendment.

Tanaya Jagtiani contributed to this article, with inputs and insights from Dr Shankara Prasad, Sonali Srivastava, Jyothsna Devi, Ila Reddy, and Anant Maringanti. — Know more

India Development Review (IDR) is India’s first independent online media platform for leaders in the development community. Our mission is to advance knowledge on social impact in India. We publish ideas, opinion, analysis, and lessons from real-world practice.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

31 Local Government

KC Sivaramakrishnan was the Chairman of the Governing Board, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi.

This chapter remained unfinished at the time of the author’s death. A substantial draft had been written, and the final version was edited and completed by Raeesa Vakil. The author was formerly the Secretary, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, and wanted it to be noted that as one among others involved in the drafting of the Seventy-fourth Amendment, he shares in the responsibility for the deficiencies in the drafting of the Amendment.

- Published: 06 February 2017

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines the constitutional framework for the structure of local government in India, particularly the background, scope, and content of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments, 1992 to the Indian Constitution. The Seventy-third Amendment required States to create self-governing, elected village councils, or panchayats , while the Seventy-fourth Amendment required the creation of elected municipalities in urban areas. The history of local self-government in India is discussed, before turning to a discussion of the constitutional position of local government in the country after Independence. The constitutional and statutory provisions on local government are considered, along with the motivations and the context behind the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments. The chapter explores issues of structure and implementation in local government, the functions and powers of local governments, and the case of industrial townships. Finally, it evaluates the functions and powers of local bodies and their place in the federal framework.

I. Introduction

The structure of local government in India has been the subject of a series of legal and political contestations, beginning from colonial rule and continuing to the independent modern State. The colonial Indian State embraced franchise in local governments while simultaneously withholding financial autonomy, reinforcing Lord Ripon’s claim that they were administratively irrelevant, and ‘designed as … instrument[s] of political and popular education’. 1 In framing the modern Indian republic’s Constitution, the Constituent Assembly was split between Gandhi’s vision of Panchayati Raj —a State constituted of and governed by idealised, democratic self-governing village councils ( panchayats ) and Ambedkar’s equally compelling understanding of the Indian village as a ‘a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism’. 2 The current constitutional framework is an elaborate exercise in creating, constituting, and electing local governments, without directly devolving powers to them. Such powers are left, constitutionally, to States to devolve by legislation; as a consequence, although local representation has been achieved, we are still struggling to attain local self-government.

This chapter examines the background, scope, and content of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments 1992 to the Indian Constitution. The Seventy-third Amendment compelled States to create self-governing, elected panchayats (village councils) across the nation, while the Seventy-fourth Amendment implemented similar requirements for urban areas, by requiring the creation of elected municipalities.

In the twenty-three years since the introduction of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Amendments, Indian States have made slow and varying progress towards establishing local self-governing bodies, and devolving powers to them for local government. The process of devolution, both politically and financially, has been the subject of a number of analyses; however, the legal effects of these amendments remain largely unexamined. This chapter provides a brief introduction to the legal questions and issues that arise from the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments, their framing, and implementation.

Section II of this chapter lays out the motivations and the context behind the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments, which formalised local government in rural and urban India, respectively. Section III focuses on issues of structure and implementation in local government. Section IV discusses the functions and powers of local governments, and finally, Section V contains a conclusion and examines the effectiveness of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments.

II. Establishing Representative Local Self-Government in India: A Brief History

1. indigenous and colonial local government.

Local government in India has had a long indigenous and colonial history. 3 The traditional system of local self-government in villages, by unelected councils, continued through the Mughal Empire, 4 and urban government operated through delegated representatives of sovereign authorities. Early attempts to establish a formal structure for local government under colonial rule were seen as a project to inculcate democracy. Lord Ripon, as stated above, when passing a resolution for the creation of urban local bodies in 1882, viewed them primarily as ‘an instrument of political and popular education’. 5

Although local councils had been established by charter prior to this, Lord Ripon’s resolution saw the introduction of limited franchise and representation for Indians on governing bodies in colonial cities. 6 Steps for financial decentralisation were also implemented by the former Viceroy of India, Lord Mayo (1870); 7 the local bodies were constituted by the former Viceroy of India, Lord Ripon (1882), 8 as well as the Recommendations of the Royal Commission on Decentralisation (1909), 9 making local self-government fully representative and responsible. However, these were not pursued aggressively until 1919, when reforms implemented by the British Secretary of State, Edwin Montagu, along with the then Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, resulted in local self-government becoming a subject under the control of provincial governments.

The 1919 model was replicated to an extent in the Government of India Act 1935, which permitted provinces to control local government without creating a common legal structure or status for them. Essentially, colonial local self-governments were, as Sunil Khilnani describes them, ‘theatres of Independence’, 10 allowing Indian politicians to gain representation and experience in the processes of parliamentary democracy; however, their powers, finances, and functions were limited and controlled by provincial and State legislatures and Central authorities.

When debating local government while framing the Constitution, several members of the Indian Constituent Assembly such as Arun Chandra Guha, KT Shah, RK Sidhwa, and others urged that the village panchayats (governing councils in villages) should be formally recognised as units of government, should be financially empowered, and should be the basic units of provincial governments. 11 A wide spectrum of members supported this position 12 and invoked the views of Gandhi, who had famously advocated a State constituted of independent and self-sufficient ‘village republics’ 13 (commonly described as Panchayati Raj or rule by the village councils).

There was, however, equal opposition to the notion, led primarily by Dr BR Ambedkar, who chaired the Drafting Committee for the Indian Constitution. Dr Ambedkar insisted that panchayats or local self-government bodies did not merit separate mention as entities of the State, famously describing the typical Indian village as ‘a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism’. 14 A proposed amendment to implement Panchayati Raj in a staggered fashion, moved by Dr KT Shah, did not succeed. 15

Eventually, to break the impasse, a compromise formula was worked out by K Santhanam, and supported by Ananthasayanam Ayyangar. 16 They proposed that a provision should be made in the Directive Principles of State Policy that ‘the State shall take steps to organise village panchayats and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government’. The Directive Principles of State Policy, constituting Chapter IV of the Indian Constitution, are unenforceable recommendations for the governance of India. The draft Article 31A proposed by them became what is currently Article 40 in the Constitution:

Organisation of village panchayats.—The State shall take steps to organize village panchayats and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government. 17 17 Constitution of India 1950, art 40.

As an unenforceable provision, this had limited value, and moreover, wholly ignored urban local governments. To allow States to legislate on these issues, List II of Schedule VII of the Constitution, which allocates legislative powers to the States, was provided with Entry 5, which gives States the power to legislate on:

Local government, that is to say, the constitution and powers of municipal corporations, improvement trusts, district boards, mining settlement authorities and other local authorities for the purpose of local self-government or village administration. 18 18 Constitution of India 1950, Entry 5, List 2, Schedule 7.

The power to control local governments, therefore, was vested almost entirely with States; a position that is purported to have been altered by the grant of constitutional status to panchayats and municipalities, but remains, effectively, the same, despite the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments.

2. Local Government in Independent India

The constitutional position of this subordinate status of local government remained the same for many years. Local bodies remained under the control of State Governments and lacked independent constitutional footing. They were, consequently, subject to repeated supersession and interference in their functioning by States, and were also financially dependent on the States. 19

By the mid-1960s about 60,000 village panchayats , 7,500 panchayat samitis , and 330 Zilla Parishads had been set up across the country. In some States, local acts such as the Madras Panchayats Act 1958 and Madras District Development Council Act 1958 for Tamil Nadu, resulted in the creation of panchayat unions, coterminus with development blocks, entrusting to them developmental and social welfare functions. The District Boards were replaced by District Development Councils, which acted as advisory bodies. In Maharashtra, the Bombay Panchayats Act 1958 and the Maharashtra Zilla Parishads and Panchayat Samitis Act 1961 created a three-tier system. Though these Acts envisaged an impressive list of duties and functions to be allocated to local governments, various problems in actual implementation were encountered partly because of frequent political changes. 20

In regard to urban local bodies, again, the position was worse. Most municipalities across the country were vulnerable to supersession by State Governments, irrespective of the political party, which was in power in the States. Indeed, the phenomenon of supersession began soon after Independence, when the Calcutta Corporation was superseded in 1948. The Madras Corporation was superseded in 1973, which lasted for twenty-four years. Another notorious example is the municipality of Gaya, which was set up in 1985 but was placed immediately under suspension and run by an administrator. Sixteen years later, in 2001, judicial intervention finally compelled the State Government to hold elections for the Municipal Corporation of Gaya. 21

In 1986, the government appointed a committee chaired by eminent jurist LM Singhvi to assess the gaps and anomalies brought out by experience in regard to the rural and urban local bodies. 22 The Singhvi Committee recommended that local self-government should be constitutionally recognised, protected, and preserved by the inclusion of a new chapter in the Constitution. The Committee further recommended that Panchayati Raj institutions should be constitutionally proclaimed as the third tier of the government.

3. Constitutional Amendments for Local Government

In 1988, the Government of India, then headed by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, amplified the Singhvi Committee’s recommendations and used them to advance some important objectives. This approach was evident in various speeches made by the Prime Minister, in different public functions. For example, in the inaugural function of the Golden Jubilee of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly held in Bombay on 3 September 1988, Rajiv Gandhi observed that ‘the transmission of democracy and development to the levels where the bulk of the people lived required a national debate and if necessary an amendment to the Constitution’. 23

Another important objective, as mentioned before, was to increase the number of persons holding elected office in the country. Introducing the Constitution (Sixty-fourth) Amendment Bill 24 on Panchayati Raj in the House of the People on 15 May 1989, Rajiv Gandhi observed that putting together both Houses of Parliament and all the State legislatures, the State had only between 5,000 and 6,000 persons representing a population of nearly 800 million. He envisaged that democracy in the panchayats on the same basis of sanctity as enjoyed by Parliament and the State legislature would bring in about seven lakh elected representatives. This would ensure the holding of regular and periodic elections and also provide for the reservation of Scheduled Castes and Schedules Tribes on par with Parliament and the State legislatures.

Though Rajiv Gandhi obtained a resolution of different State legislatures as envisaged in Article 252, requesting Parliament to enact a law on the subject, some States, such as West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, strongly objected to Parliament embarking on this enactment. 25 The Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, for instance, stated in his letter:

This State Government is not agreeable to the suggestion to transfer the subject entrusted to the State Governments under Entry 5 in the State List in the Constitution of India, to the Central List. The suggestion to entrust the conducting of Municipal Elections to the Election Commission is also not acceptable to us . . . I would like to observe on behalf of the people of Tamil Nadu, our government will not agree to the amendment of the Constitution which amounts to taking away the rights of State Governments. 26

The Sixty-fourth Constitution Amendment Bill for panchayats was introduced in the Lok Sabha on 15 May 1989 and the Sixty-fifth Constitution Amendment Bill for nagarpalikas (municipalities) was introduced on 8 August 1989. On 10 August, the Lok Sabha passed the Bills. However, on 13 October 1989 both the Bills were defeated in the Rajya Sabha. Late in 1989 the National Front government was formed, with VP Singh as Prime Minister. On 4 September 1990, the government introduced in the Lok Sabha a composite Bill of Constitution Amendment (No 156 of 1990). On 7 November, the government itself fell. On 21 May 1991, Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated. On 21 June, the Narasimha Rao government was sworn in. That government declared that it would revive the Panchayati Raj initiative, and on 16 September two separate Bills were introduced as the Seventy-second and Seventy-third Constitution Amendment Bills. Both were referred to two Joint Parliamentary Committees. While there were some important differences between the Seventy-second and the Seventy-third Bills introduced as compared to the Sixty-fourth and Sixty-fifth Bills, the two Joint Parliamentary Committees significantly amplified the provisions and finalised the recommendations in July 1992.

On 22 December and 23 December 1992, the Amendment Bills with the recommendations of the JPC were considered and passed in the Lok Sabha and in the Rajya Sabha, respectively. In April 1993 both the Amendment Acts, renumbered as the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments, received the assent of the President and became law.

III. Local Government in the Constitution and in Statutes

1. overview of constitutional and statutory provisions on local government.

In this part, an outline of constitutional and statutory provisions for local government in India is provided. It also covers the structure and composition of local governments, provisions for elections, representations, and electoral reservations, their duration and suspension, and the conduct of elections to local bodies.

The Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments introduced Part IX (entitled ‘The Panchayats’) and Part IXA (entitled ‘The Municipalities’) into the Constitution. The most significant aspect of these amendments is that they do not, in fact, mandate the implementation of self-government. Rather, they mandate the creation of local self-governing bodies, but leave the question of delegating powers and functions to these bodies to State legislatures. Articles 243G and 243W both provide that ‘the Legislature of a State, may, by law, endow … ’ the panchayats and municipalities with powers and functions. Similarly, the financing of local bodies is provided for by the Constitution of State Finance Commissions in Articles 243I and 243Y, which recommend distribution of funds to the State. The State, in turn, determines allocation to local bodies.

The remaining provisions of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments contain detailed structural requirements on the structure, elections to, and representation in local self-government bodies. The product of this rather dichotomous drafting has led to a large body of litigation that focuses on local representation , and comparatively little that focuses on local government . It must be noted, in addition, that certain parts of India, in keeping with the Constitution, are not governed by Parts IX and IXA. Three exceptions operate: Union Territories, which are directly administered by the Centre, are subject to these provisions but can be exempted in part or whole by the President; 27 certain areas listed in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution are exempted, 28 although Parliament and State legislatures can resolve to extend the constitutional provisions of local government to these areas. 29 Finally, cantonment areas fall under the control of defence forces and the Ministry of Defence. 30

Even as Parts IX and IXA of the Constitution provide for the constitution of local government bodies, States retain the power to frame laws that implement these parts, and govern how these bodies function, and what powers they assume. This power is drawn from Entry 5 of Schedule VII of the Constitution, which makes local government a subject for exclusive legislation by the States. State legislatures have therefore accumulated a plethora of laws on local government, both rural and urban, that pre-dated the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments.

It is common for States to have specific statutes for urban and rural local government bodies (eg, the Tripura Panchayats Act 1993 and the Tripura Municipalities Act 1994). State Governments may, in addition, have specific acts for different types of local governments in rural or urban areas; for instance, the Karnataka Municipalities Act 1964 provides for smaller municipalities, while the Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act 1976 provides for larger municipal areas. In the case of larger cities, States may frame a specific statute for that city to enable it to address specific governance issues: for instance, the city of Mumbai’s corporation is governed by the much-amended Mumbai Municipal Corporation Act 1888, while the City of Panaji Corporation Act 2002 makes specific provisions for the capital city of the State of Goa.

With the passing of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Amendments, a minimal level of uniformity was brought into varying patterns of local governments across States. Consequently, Articles 243N and 243ZF allowed these existing State laws to continue after Parts IX and IXA were inserted in the Constitution, for a period of only one year, unless they were repealed or amended to be brought into conformity with the new constitutional provisions.

Inevitably, the compliance—or lack thereof—of State laws with the constitutional provisions has formed a rich source of litigation at the High Courts and at the Supreme Court. 31 The Supreme Court has tended to endorse the powers of the State legislatures to legislate beyond the provisions of Parts IX and IXA of the Constitution—in Bhanumathi v State of Uttar Pradesh , Ganguly J held that the State could legislate to allow for no-confidence motions against the heads of panchayats even though the Seventy-third Amendment is silent on whether this is allowed. The power of States to legislate on local government, he pointed out, drew from Entry 5 of List II of Schedule VII, which remained in the Constitution despite the passing of the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments. Consequently, the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments do not prevent State legislatures from legislating on local government; rather, they allow States to legislate on all issues pertaining to them so long as the minimum requirements of these amendments are met.

2. The Structure and Composition of Local Government Bodies

The Constitution, in Parts IX and IXA, lays down a broad outline for the structure of local bodies. In doing so, these two parts create a baseline on which States may legislate to provide for variations to account for their individual populations, social structures, economies, and political frameworks. It is accurate to say that while the legal structure of local government bodies across India is not uniform, there are some uniform characteristics laid out by the Constitution.

The creation of rural and urban local bodies is mandatory. Article 243B says, ‘There shall be constituted in every State, Panchayats at the village, intermediate, and district levels … ’ 32 and similar language in Article 243Q provides for the constitution of municipalities in urban areas. Like panchayats at the village, intermediate, and district levels, municipalities are of three kinds: nagar panchayats (city panchayats ) for areas that are transitioning from rural to urban; municipal councils for smaller urban areas; and municipal corporations for larger urban areas. State legislatures ultimately determine how these categories are defined, although in Article 243Q the Constitution does provide some guidelines for this. 33

3. The Case of Industrial Townships: Subverting Representative Local Government

Although Article 243Q compels the constitution of municipalities in urban areas, a most obnoxious provision was introduced by a proviso to Article 243Q, allowing that a municipality may not be constituted in an urban area if the municipal services are proposed to be provided by an industrial establishment, in which case the area may be specified as an industrial township. This proviso was not a part of the draft introduced in Parliament, neither did it come up for consideration at all in the Joint Parliamentary Committee.

In 2009, a request for information was filed under the Right to Information Act 2005, to the Ministry of Urban Development. 34 This request sought information on the inclusion of this proviso to Article 243Q and sought to know, inter alia, whether this proviso was originally contained in the Bill, whether it was referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee that reviewed the Bill, and whether any corporation had requested its inclusion. The response from the Ministry of Urban Development, received through letters dated 6 March 2009 (initial response) and 16 April 2009 (response on first appeal) has revealed that the then Chief Minister of Orissa, Biju Patnaik, and another Union Minister requested Prime Minister Narasimha Rao by a letter dated 20 November 1992 to consider excluding industrial townships from the purview of the amendment. Responding to this suggestion, a so-called political consensus was arrived at in haste and the proviso was introduced as a government motion at the stage of consideration of the Bill. 35

Given the fact that a Joint Parliamentary Committee had given its recommendations on the Bill already, this single clause ‘introduced by the Government’ did not attract any attention and the Bill was passed. Though the Joint Parliamentary Committee on local government as well as the government-appointed Commission on Administrative Reforms has decried this arrangement of exclusion, the Government of India itself (Ministry of Commerce) advised various States to actively take advantage of the proviso and exempt industrial townships and Special Economic Zones (SEZs) from municipal purview. The Tata Nagar Steel Township in the Jamshedpur area has been the longest-standing effort to resist municipalisation.

The ‘industrial township’ proviso has been used to great effect by the Indian government to exclude what are known as SEZs from the purview of local government. The Special Economic Zones Act 2005 provides no role for local bodies, and only allocates functions between the State and Centre. Instead, these areas are to be governed by a ‘Board of Approval’ 36 and Development Commissioners for various sub-zones inside the SEZ. 37 Local bodies are not represented the management of SEZs. The loophole that the proviso to Article 243Q provides is therefore used to appoint real estate bodies, industrial councils, and industrial corporations as the heads of local government. 38 This has the effect of not only disenfranchising the residents of these zones, but also preventing them from participating in decisions that affect their daily lives.

The key example of this industrial township exception is the town of Jamshedpur, which has been run in this manner since 1922 by various entities that ultimately became Tata Steel. 39 When the Seventy-fourth Amendment came into force, a number of persons filed petitions seeking the constitution of a municipality and the conduct of elections. The issue here was that the Bihar and Orissa Municipal Act 1922, which originally governed this area, allowed for the creation of a ‘notified area committee’ composed of an industrial company, to govern an area in which an industrial establishment was located. Subsequent to the Seventy-fourth Amendment, this was deleted, to bring the Act in conformity with the amendment. The State could now declare an area to be an industrial township and exempt it from elected local government under Article 243Q, or create a municipality. In the High Court of Jharkhand, SJ Mukhopadhyay J had held that a valid notification of an industrial township had not been issued, and consequently, the State was directed to constitute a municipality or an industrial township in the manner provided by law. 40 The case was appealed and is still pending before the Supreme Court, and has not been concluded. 41 Key questions concerning the validity of laws permitting the exemption of local government from industrial areas continue to remain unresolved. Very recently, in response to a Supreme Court direction, a meeting of public representatives in Tata Nagar preferred to remain under the Tata Company’s private management rather than come under a municipality requiring payment of taxes. 42

Similar facts arose when the Seventy-fourth Amendment was implemented in the State of Gujarat. Like Jamshedpur, the capital of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, was a notified area under the Gujarat Municipalities Act 1963. When the Act was amended to remove notified area committees and required the constitution of an industrial township, the State Government failed to respond, and no municipality or industrial township was constituted. Accordingly, a suit was filed in the Gujarat High Court seeking a writ directing the State to constitute a municipality. 43 KS Radhakrishnan CJ held that ‘by non-formation of the Municipal Corporation at Gandhinagar, the constitutional requirement … has been given a complete go-bye’. 44

The inclusion of the proviso to Article 243Q also leaves open a number of constitutional issues that are yet to be decided. Can the corporate entities running an industrial township exercise sovereign functions that a municipality can—the levy of fees and taxes, etc? Can the term ‘industrial establishment’ be extended to any non-State body that acts as a promoter of an industrial area? Would it extend to real estate development agencies, which are geared towards disposing of the land and not supplying essential services? These questions remain open and unanswered.

The Supreme Court has only briefly touched upon these issues. In Saij Gram Panchayat v State of Gujarat , 45 the Supreme Court considered the question of whether the creation of an industrial township out of rural areas was contrary to the Constitution. Sujata Manohar J held that although industrial areas would be generally constituted in urban areas, this would include areas that were transitioning from rural areas to urban areas. The key issues that arise from the proviso to Article 243Q, accordingly, remain unanswered.

Today there are more than 500 entities in the country that are presently beyond municipal purview, including private development companies exercising sovereign powers as an industrial township. It is likely that this trend will continue. 46 As a result, the proviso to Article 243Q brought by the government itself has rendered a mortal blow to the very essence of setting up municipalities in urban areas as institutions of self-government.

4. The Composition of Local Bodies: Franchise and Representation

The most significant changes that Parts IX and IXA introduced to local bodies were the constitutional recognition of elected local representatives and adult franchise for the same. 47 The scale of representation is extraordinary; more than three million persons are elected to panchayats and municipalities across the country. 48

Articles 243C and 243R provide for the composition of municipalities and panchayats whose members are to be chosen by direct elections from territorial constituencies. The principle that guides these elections is that the ratio of the territorial area of the local body to the number of seats it elects should be, as far as possible, the same throughout a State. Beyond this, State legislatures are empowered to make specific provisions for the election of chairpersons, for inclusion of other elected representatives such as Members of Parliament or State Legislative Assemblies.

An important major constitutional issue, which has so far not been agitated specifically, is the provision allowing members of the Union and State legislatures to be members of local bodies as well. Dual membership in Union and State legislatures is prohibited in Article 101 of the Constitution. 49 In the case of local bodies, however, this prohibition does not exist, and States are explicitly given powers to legislate for the representation of members of Union and State legislatures in local bodies, provided they are from the territorial constituency of those local bodies. 50 The prohibition on dual membership of State and Union legislatures is because both these bodies are considered on a par in constitutional status and are expected to operate exclusively in the domain as provided in the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. If the basic intention of setting up Panchayati Raj and nagarpalika bodies as institutions of self-government on a par with Parliament and the State legislature was that they should exercise their functional domain in keeping with the Eleventh and Twelfth Schedules of the Constitution, there is no reason why these bodies alone should be subjected to the double membership of the Members of Parliament and members of the State legislature. 51

Though the validity of persons holding such dual membership has not been specifically challenged, in a number of cases in the State High Courts, the nature and extent of powers under this membership have been questioned. In some cases it has been held that MPs and State legislators are invitees to the local bodies and do not have the right to vote as elected members. 52 In some others it has been held they do have voting rights. 53 In the celebrated case relating to the MP’s Local Area Development scheme, which was heard over several years by the Supreme Court, a kind of non-judgment eventually became available, stating that the division of executive power as between the government and the legislature was not clear in the Indian Constitution and as such there seemed to be no bar on legislators entering upon the executive domain or being substantially involved in the implementation of local schemes, 54 though most of these schemes fall under the purview of local bodies.

In addition to the above constitutional provisions, local bodies were given fixed tenures; 55 and State Election Commissions were created to conduct elections for them. 56 State Finance Commissions were constituted to advise on their finances 57 and rules for reservations of seats for backward classes, castes, and women were introduced. 58 As with the structure and composition, these aspects of local government are left partly to the discretion of States, to be implemented through State legislation. For instance, disqualifications for membership of local bodies through elections are to be specified by State law. 59

States have made significant modifications to laws governing representation, particularly when it comes to reserving seats for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Castes. Articles 243D and 243T require that no less than one-third of the total seats in local bodies, including one-third of the reserved seats, are to be further reserved for women. Some States, such as Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bihar, Kerala, Karnataka, Orissa, and Chhattisgarh, have increased this to 50 per cent of seats for women, in urban local bodies. Moreover, reservations for Other Backward Castes are left to the States to determine, and consequently, conflicts over the amount of reservation and how it is calculated have frequently resulted in legal disputes.

A second, significant source of conflict has been over the interpretation of fixed tenure for local bodies. As local bodies operate almost entirely under State control, a common problem has been the suspension of elected local bodies in the course of political maneouvring, and their replacement by an unelected ‘administrator’ by State Governments. In the Statement of Objects and Reasons that introduced the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments, specific reference was made to this problem, noting that ‘In many States local bodies have become weak and ineffective on account of a variety of reasons, including the failure to hold regular elections, prolonged supersessions and inadequate devolution of powers and functions.’ 60

Articles 243E and 243U attempt to remedy this by providing that local bodies have fixed tenures of five years. Elections must be held before the end of or within six months of the end of this period. States often claim delays in the conduct of elections for local bodies on the grounds of incomplete delimitation of constituencies after increases in population. 61 Early in 2015, the Karnataka State Government claimed that it was unable to hold elections for the capital city of Bengaluru, since it proposed to trifurcate Bengaluru’s municipal corporation. This, the State argued, would require fresh delimitation, and until such delimitation took place, elections had to be postponed, and the municipality administered by a State official. The State Government was eventually compelled by the High Court of Karnataka to proceed with elections regardless of future proposals for municipal restructuring. 62 Courts have generally disallowed delays such as this, usually holding that in such instances, elections should be held on the basis of the previous, existing delimitation. This is an uneasy compromise, as it often results in insufficient representation to burgeoning populations of reserved categories. 63

5. The Conduct of Elections to Local Bodies

In all the three draft amendment Bills that preceded the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments, it was proposed that an autonomous election commission be constituted. This body was to deal with the entire range of electoral functions for local bodies, such as delimitation, reservation of constituencies for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, conduct and superintendence of elections, and other connected matters. 64

Provisions for the State Election Commissions were based almost entirely on the provision of the Central Election Commission. 65 The Election Commission in India, as a fiercely independent body, has resisted attempts on the part of the government to interfere with its ability to regulate and conduct elections. 66 Given the fact that the State Election Commissions are very much a clone of the Central Election Commission, it was expected that the same level of independence would apply.

Nevertheless, in several of the States, governments have encroached upon the jurisdiction of the State Election Commission and taken over some of the powers. For instance, in Chanigappa v State of Karnataka , 67 the Karnataka High Court held that the State Government could take over some functions of the State Election Commission, such as delimitation of constituencies, since these functions preceded the electoral process and were not a part of it. This in turn has invariably delayed the timely holding of elections and resulted in extensive litigation. The composition, inclusion, and exclusion of members from electoral rolls are frequently challenged, as are the delimitation of constituencies, and the powers exercised by the State Election Commissions. 68

It must be noted, however, that the Constitution, in an attempt to control the vast amount of litigation generated by electoral processes in local bodies, had barred the jurisdiction of courts in any disputes concerning the validity of laws relating to delimitation, allotment of seats to constituencies, or that call into question the elections to any local bodies by allowing States to legislate and create alternative appellate bodies. 69 Courts do, however, interfere when State electoral appeals processes do not allow remedies in specific circumstances, or when there have been instances of violations of fundamental rights. 70 While a systematically applied test has not yet evolved, the formulation of the Delhi High Court in Chand Kumar v Union of India 71 demonstrates how courts apply their powers in writ jurisdiction to overcome the prohibition on jurisdiction. In this case, R Lahoti J held that:

This Court has not been called upon to examine the validity of any law relating to delimitation of constituencies or the allotment of seats to such constituencies made or purporting to be made under Article 243ZG. Any delimitation if it falls foul of the statutory power under which it purports to have been made and smacks of arbitrariness, whim or fancy, offensive of Article 14 of the Constitution then it is open to judicial review under Article 226 of the Constitution on the well established parameters. 72 72 Chand Kumar (n 71 ) [20].

The irregularly applied test in Article 243ZG, coupled with a lack of clarity on the powers of the State Election Commissions, continues to lead to litigation in courts. While the conduct of local elections on a massive scale in India is laudable, there are still some issues, such as these, which require clarity, either by judicial or legislative intervention.

IV. The Functions and Powers of Local Bodies and their Place in the Federal Framework

1. failures in devolution and the rise of parallel bodies.

The most significant lacuna in the constitutional framework on local government is that the transfer of various State functions, such as the management of health, local education, sanitation, and housing, has been not directly implemented in Parts IX and IXA of the Constitution. Subjects that could be transferred to local bodies were listed in two Schedules to the Constitution, with the provision that States could, through State law, transfer these functions from the State Government to local bodies. 73 Neither Article 243G (dealing with panchayats ) or Article 243W (dealing with municipalities) makes the transfer of functions mandatory.

I have argued before that the language of Articles 243G and 243W creates an obligation on States to devolve powers and responsibilities listed in Schedules XI and XII by framing laws. The only leeway granted to States is the manner in which the statutes for devolvement are framed. 74 This view is not taken by the courts, which have held, by and large, that State legislatures have leeway not just on how and when power devolves to local bodies, but on whether to devolve such power at all. 75 The Allahabad High Court, for instance, has clearly held that Article 243G is ‘only an enabling provision. It enables the State Legislature endow panchayats with certain powers … the legislature of a State is not bound to endow the panchayats with the powers referred to in Article 243G and it is in its discretion to do so or not.’ 76 In Andhra Pradesh, a challenge raised to State laws that provided for incomplete devolution was rejected by the majority in Ranga Reddy District Sarpanches Association v Andhra Pradesh . 77 The petitioners, an association of panchayat chairpersons, argued that Article 243G was mandatory, compelling States to devolve powers. PS Narayana J, for the majority held:

A careful analysis of the Article makes it clear that the directives envisaged by Article 243G are discretionary in nature. Hence the contention that Article 243G and Eleventh Schedule of the Constitution had conditioned the Legislative power of the State in Article 246 and Seventh Schedule, cannot be accepted … The power of the State Legislature to legislate on a subject relating to an entry in State List or Concurrent List is well governed by specific provisions and hence it cannot be said that by introduction of Article 243G by 73rd Constitutional Amendment, the power to legislate relating to those entries is in any way curtailed … 78 78 Ranga Reddy District Sarpanches Association (n 77 ) [21]–[22].

The failure to devolve functions to local bodies has led to States replacing them with parallel executive bodies that carry out the same functions. For instance, although the management of water supply can be transferred to municipalities under Item 5, Schedule XI, it has become increasingly common for States to constitute executive-controlled Water Boards to manage these. 79 This is most common in questions of planning—although Part IXA provides for the constitution of district and metropolitan planning committees, 80 and for the delegation of planning powers to municipalities, 81 it is almost ubiquitous for States to have ‘Development Agencies’ that take on this function.

A challenge to the diversion of planning functions from representative local bodies to executive ones was raised in Bondu Ramaswamy v Bangalore Development Authority (2010) 7 SCC 129. In a much criticised judgment, 82 the Supreme Court endorsed an act of the Karnataka State legislature that effectively removed town planning powers from the elected municipality for the city of Bengaluru and vested them in an executive-controlled ‘Development Authority’. 83 The challenge related to Article 243ZF, which allows laws predating the constitutional amendments on local government to continue only if they comply with the amendments.

The Court held, somewhat confusingly, that:

The benefit of Article 243ZF is available only in regard to laws relating to ‘municipalities’ … neither any city improvement trust nor any development authority is a municipality, referred to in Article 243ZF. Thus Article 243ZF has no relevance to test the validity of the BDA Act or any provision thereof. 84 84 Bondu Ramaswamy (n 83 ) [42] (RV Raveendran J).

Bondu Ramaswamy ’s case effectively implies that the State can legitimately restrict the powers of elected local self-government bodies by simply constituting another body and vesting powers in it. Such alternative bodies do not fall afoul of the Constitution, because they are not local self-government bodies.

Subsequent challenges to the diversion of local functions have failed, as the Supreme Court and High Courts, bound by Bondu Ramaswamy ’s precedent and the wording of Parts IX and IXA, can neither authorise nor compel devolution. Thus, although Articles 243G and 243W envisage that the State will enable local bodies to ‘function as institutions of self-government’ the Supreme Court has found this an insufficient mandate to interfere with the State’s legislative powers to devolve functions at its own pace.

2. Financing Local Bodies: Powers of Taxation

Part of the incapacity of local bodies to function effectively stems from their inability to raise finances of their own. Articles 243H and 2343X, formulated in similar language, make it amply clear that any powers of taxation that local bodies have must be devolved upon them by State legislatures. The State Finance Commissions, constituted under Articles 243I and 243Y, are then authorised to recommend to State Governments the principles on which the revenue so collected is distributed between the State and local governments. The starvation of finances in local bodies has led to at least one instance of a court ordering the State to release funds that will enable a municipality to pay its dues to its employees. 85 Attempts by municipalities to levy taxes on areas where powers have been devolved have also been successfully challenged, on the ground that the power to tax on subjects even within their control has to be specifically authorised by statutes. 86 The Bombay High Court, in a case where a challenge was raised to the constitutionality of municipal taxation laws in Maharashtra, held that a State could levy taxes on municipal subjects without transferring powers to municipalities. SC Dharmadhikari J held, ‘Eventually, the Municipality derives its power and authority to impose the tax from the law made by the Legislature.’ 87

Consequently, with neither powers nor finances, municipalities and panchayats are almost wholly at the mercy of State Governments. While their elections, constitution, and composition are couched in imperative terms, their functional and financial powers remain limited and optional.

3. India’s Federal Framework and Local Bodies

The changes brought about by the Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Constitutional Amendments were not purely administrative. An important impact of these amendments was on the federal structure of the nation. Historically envisaged as a careful balancing of powers and functions between States and a strong Centre, the addition of a third—constitutionally recognised—level was bound to lead to some confusion about the place of local bodies in the federal identity.

While strengthening of rural and urban local bodies could not be questioned as an objective, conferring on these bodies a status on a par with Parliament and the State legislatures or making them a third tier of the government was fraught with significant constitutional issues. As stated before, the Constitution clearly recognised that all matters connected with rural and urban local bodies were entirely within the legislative and executive jurisdiction of the States as per Entry 5 of the State List in Schedule VII to the Constitution. In order to pass these amendments to the Constitution, the government was obliged to obtain the consent of at least half the States, and it is true that the government did so. 88 It was then left open to the best judgment of the Rajiv Gandhi government to decide to what extent the authorisation by the State legislatures could be stretched.