Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Speaking, writing and reading are integral to everyday life, where language is the primary tool for expression and communication. Studying how people use language – what words and phrases they unconsciously choose and combine – can help us better understand ourselves and why we behave the way we do.

Linguistics scholars seek to determine what is unique and universal about the language we use, how it is acquired and the ways it changes over time. They consider language as a cultural, social and psychological phenomenon.

“Understanding why and how languages differ tells about the range of what is human,” said Dan Jurafsky , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor in Humanities and chair of the Department of Linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford . “Discovering what’s universal about languages can help us understand the core of our humanity.”

The stories below represent some of the ways linguists have investigated many aspects of language, including its semantics and syntax, phonetics and phonology, and its social, psychological and computational aspects.

Understanding stereotypes

Stanford linguists and psychologists study how language is interpreted by people. Even the slightest differences in language use can correspond with biased beliefs of the speakers, according to research.

One study showed that a relatively harmless sentence, such as “girls are as good as boys at math,” can subtly perpetuate sexist stereotypes. Because of the statement’s grammatical structure, it implies that being good at math is more common or natural for boys than girls, the researchers said.

Language can play a big role in how we and others perceive the world, and linguists work to discover what words and phrases can influence us, unknowingly.

How well-meaning statements can spread stereotypes unintentionally

New Stanford research shows that sentences that frame one gender as the standard for the other can unintentionally perpetuate biases.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

Exploring what an interruption is in conversation

Stanford doctoral candidate Katherine Hilton found that people perceive interruptions in conversation differently, and those perceptions differ depending on the listener’s own conversational style as well as gender.

Cops speak less respectfully to black community members

Professors Jennifer Eberhardt and Dan Jurafsky, along with other Stanford researchers, detected racial disparities in police officers’ speech after analyzing more than 100 hours of body camera footage from Oakland Police.

How other languages inform our own

People speak roughly 7,000 languages worldwide. Although there is a lot in common among languages, each one is unique, both in its structure and in the way it reflects the culture of the people who speak it.

Jurafsky said it’s important to study languages other than our own and how they develop over time because it can help scholars understand what lies at the foundation of humans’ unique way of communicating with one another.

“All this research can help us discover what it means to be human,” Jurafsky said.

Stanford PhD student documents indigenous language of Papua New Guinea

Fifth-year PhD student Kate Lindsey recently returned to the United States after a year of documenting an obscure language indigenous to the South Pacific nation.

Students explore Esperanto across Europe

In a research project spanning eight countries, two Stanford students search for Esperanto, a constructed language, against the backdrop of European populism.

Chris Manning: How computers are learning to understand language

A computer scientist discusses the evolution of computational linguistics and where it’s headed next.

Stanford research explores novel perspectives on the evolution of Spanish

Using digital tools and literature to explore the evolution of the Spanish language, Stanford researcher Cuauhtémoc García-García reveals a new historical perspective on linguistic changes in Latin America and Spain.

Language as a lens into behavior

Linguists analyze how certain speech patterns correspond to particular behaviors, including how language can impact people’s buying decisions or influence their social media use.

For example, in one research paper, a group of Stanford researchers examined the differences in how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online to better understand how a polarization of beliefs can occur on social media.

“We live in a very polarized time,” Jurafsky said. “Understanding what different groups of people say and why is the first step in determining how we can help bring people together.”

Analyzing the tweets of Republicans and Democrats

New research by Dora Demszky and colleagues examined how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online in an attempt to understand how polarization of beliefs occurs on social media.

Examining bilingual behavior of children at Texas preschool

A Stanford senior studied a group of bilingual children at a Spanish immersion preschool in Texas to understand how they distinguished between their two languages.

Predicting sales of online products from advertising language

Stanford linguist Dan Jurafsky and colleagues have found that products in Japan sell better if their advertising includes polite language and words that invoke cultural traditions or authority.

Language can help the elderly cope with the challenges of aging, says Stanford professor

By examining conversations of elderly Japanese women, linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto uncovers language techniques that help people move past traumatic events and regain a sense of normalcy.

Essays About Language: Top 5 Examples and 7 Prompts

Language is the key to expressive communication; let our essay examples and writing prompts inspire you if you are writing essays about language .

When we communicate with one another, we use a system called language. It mainly consists of words, which, when combined, form phrases and sentences we use to talk to one another. However, some forms of language do not require written or verbal communication , such as sign language .

Language can also refer to how we write or say things. For example, we can speak to friends using colloquial expressions and slang, while academic writing demands precise, formal language. Language is a complex concept with many meanings; discover the secrets of language in our informative guide.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

5 Top Essay Examples

1. a global language: english language by dallas ryan , 2. language and its importance to society by shelly shah, 3. language: the essence of culture by kelsey holmes.

- 4. Foreign Language Speech by Sophie Carson

- 5. Attitudes to Language by Kurt Medina

1. My Native Language

2. the advantages of bilingualism, 3. language and technology, 4. why language matters, 5. slang and communication, 6. english is the official language of the u.s..

“Furthermore, using English, people can have more friends, widen peer relationships with foreigners and can not get lost. Overall, English becomes a global language; people may have more chances in communication. Another crucial advantage is improving business. If English was spoken widespread and everyone could use it, they would likely have more opportunities in business. Foreign investments from rich countries might be supported to the poorer countries.”

In this essay, Ryan enumerates both the advantages and disadvantages of using English; it seems that Ryan proposes uniting the world under the English language. English, a well-known and commonly-spoken language can help people to communicate better, which can foster better connections with one another. However, people would lose their native language and promote a specific culture rather than diversity. Ultimately, Ryan believes that English is a “global language,” and the advantages outweigh the disadvantages

“ Language is a constituent element of civilization. It raised man from a savage state to the plane which he was capable of reaching. Man could not become man except by language. An essential point in which man differs from animals is that man alone is the sole possessor of language. No doubt animals also exhibit certain degree of power of communication but that is not only inferior in degree to human language, but also radically diverse in kind from it.”

Shah writes about the meaning of language, its role in society, and its place as an institution serving the purposes of the people using it. Most importantly, she writes about why it is necessary; the way we communicate through language separates us as humans from all other living things. It also carries individual culture and allows one to convey their thoughts. You might find our list of TOEFL writing topics helpful.

“Cultural identity is heavily dependent on a number of factors including ethnicity, gender, geographic location, religion, language, and so much more. Culture is defined as a “historically transmitted system of symbols, meanings, and norms.” Knowing a language automatically enables someone to identify with others who speak the same language. This connection is such an important part of cultural exchange”

In this short essay, Homes discusses how language reflects a person’s cultural identity and the importance of communication in a civilized society. Different communities and cultures use specific sounds and understand their meanings to communicate. From this, writing was developed. Knowing a language makes connecting with others of the same culture easier.

4. Foreign Language Speech by Sophie Carson

“Ultimately, learning a foreign language will improve a child’s overall thinking and learning skills in general, making them smarter in many different unrelated areas. Their creativity is highly improved as they are more trained to look at problems from different angles and think outside of the box. This flexible thinking makes them better problem solvers since they can see problems from different perspectives. The better thinking skills developed from learning a foreign language have also been seen through testing scores.”

Carson writes about some of the benefits of learning a foreign language, especially during childhood. During childhood, the brain is more flexible, and it is easier for one to learn a new language in their younger years. Among many other benefits, bilingualism has been shown to improve memory and open up more parts of a child’s brain, helping them hone their critical thinking skills . Teaching children a foreign language makes them more aware of the world around them and can open up opportunities in the future.

5. Attitudes to Language by Kurt Medina

“Increasingly, educators are becoming aware that a person’s native language is an integral part of who that person is and marginalizing the language can have severe damaging effects on that person’s psyche. Many linguists consistently make a case for teaching native languages alongside the target languages so that children can clearly differentiate among the codes”

As its title suggests, Medina’s essay revolves around different attitudes towards types of language, whether it be vernacular language or dialects. He discusses this in the context of Caribbean cultures, where different dialects and languages are widespread, and people switch between languages quickly. Medina mentions how we tend to modify the language we use in different situations, depending on how formal or informal we need to be.

6 Prompts for Essays About Language

In your essay, you can write about your native language. For example, explain how it originated and some of its characteristics. Write about why you are proud of it or persuade others to try learning it. To add depth to your essay, include a section with common phrases or idioms from your native language and explain their meaning.

Bilingualism has been said to enhance a whole range of cognitive skills , from a longer attention span to better memory. Look into the different advantages of speaking two or more languages, and use these to promote bilingualism. Cite scientific research papers and reference their findings in your essay for a compelling piece of writing.

In the 21st century, the development of new technology has blurred the lines between communication and isolation; it has undoubtedly changed how we interact and use language. For example, many words have been replaced in day-to-day communication by texting lingo and slang. In addition, technology has made us communicate more virtually and non-verbally. Research and discuss how the 21st century has changed how we interact and “do language” worldwide, whether it has improved or worsened.

We often change how we speak depending on the situation; we use different words and expressions. Why do we do this? Based on a combination of personal experience and research, reflect on why it is essential to use appropriate language in different scenarios.

Different cultures use different forms of slang. Slang is a type of language consisting of informal words and expressions. Some hold negative views towards slang, saying that it degrades the language system, while others believe it allows people to express their culture. Write about whether you believe slang should be acceptable or not: defend your position by giving evidence either that slang is detrimental to language or that it poses no threat.

English is the most spoken language in the United States and is used in government documents ; it is all but the country’s official language. Do you believe the government should finally declare English the country’s official language? Research the viewpoints of both sides and form a conclusion; support your argument with sufficient details and research.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays .If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our guide on how to write an essay about diversity .

To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves.

HOW DOES OUR LANGUAGE SHAPE THE WAY WE THINK?

For a long time, the idea that language might shape thought was considered at best untestable and more often simply wrong. Research in my labs at Stanford University and at MIT has helped reopen this question. We have collected data around the world: from China, Greece, Chile, Indonesia, Russia, and Aboriginal Australia. What we have learned is that people who speak different languages do indeed think differently and that even flukes of grammar can profoundly affect how we see the world. Language is a uniquely human gift, central to our experience of being human. Appreciating its role in constructing our mental lives brings us one step closer to understanding the very nature of humanity.

HOW DOES OUR LANGUAGE SHAPE THE WAY WE THINK? By Lera Boroditsky

LERA BORODITSKY is an assistant professor of psychology, neuroscience, and symbolic systems at Stanford University, who looks at how the languages we speak shape the way we think.

Lera Boroditsky's Edge Bio Page

Humans communicate with one another using a dazzling array of languages, each differing from the next in innumerable ways. Do the languages we speak shape the way we see the world, the way we think, and the way we live our lives? Do people who speak different languages think differently simply because they speak different languages? Does learning new languages change the way you think? Do polyglots think differently when speaking different languages?

These questions touch on nearly all of the major controversies in the study of mind. They have engaged scores of philosophers, anthropologists, linguists, and psychologists, and they have important implications for politics, law, and religion. Yet despite nearly constant attention and debate, very little empirical work was done on these questions until recently. For a long time, the idea that language might shape thought was considered at best untestable and more often simply wrong. Research in my labs at Stanford University and at MIT has helped reopen this question. We have collected data around the world: from China, Greece, Chile, Indonesia, Russia, and Aboriginal Australia. What we have learned is that people who speak different languages do indeed think differently and that even flukes of grammar can profoundly affect how we see the world. Language is a uniquely human gift, central to our experience of being human. Appreciating its role in constructing our mental lives brings us one step closer to understanding the very nature of humanity.

I often start my undergraduate lectures by asking students the following question: which cognitive faculty would you most hate to lose? Most of them pick the sense of sight; a few pick hearing. Once in a while, a wisecracking student might pick her sense of humor or her fashion sense. Almost never do any of them spontaneously say that the faculty they'd most hate to lose is language. Yet if you lose (or are born without) your sight or hearing, you can still have a wonderfully rich social existence. You can have friends, you can get an education, you can hold a job, you can start a family. But what would your life be like if you had never learned a language? Could you still have friends, get an education, hold a job, start a family? Language is so fundamental to our experience, so deeply a part of being human, that it's hard to imagine life without it. But are languages merely tools for expressing our thoughts, or do they actually shape our thoughts?

Most questions of whether and how language shapes thought start with the simple observation that languages differ from one another. And a lot! Let's take a (very) hypothetical example. Suppose you want to say, "Bush read Chomsky's latest book." Let's focus on just the verb, "read." To say this sentence in English, we have to mark the verb for tense; in this case, we have to pronounce it like "red" and not like "reed." In Indonesian you need not (in fact, you can't) alter the verb to mark tense. In Russian you would have to alter the verb to indicate tense and gender. So if it was Laura Bush who did the reading, you'd use a different form of the verb than if it was George. In Russian you'd also have to include in the verb information about completion. If George read only part of the book, you'd use a different form of the verb than if he'd diligently plowed through the whole thing. In Turkish you'd have to include in the verb how you acquired this information: if you had witnessed this unlikely event with your own two eyes, you'd use one verb form, but if you had simply read or heard about it, or inferred it from something Bush said, you'd use a different verb form.

Clearly, languages require different things of their speakers. Does this mean that the speakers think differently about the world? Do English, Indonesian, Russian, and Turkish speakers end up attending to, partitioning, and remembering their experiences differently just because they speak different languages? For some scholars, the answer to these questions has been an obvious yes. Just look at the way people talk, they might say. Certainly, speakers of different languages must attend to and encode strikingly different aspects of the world just so they can use their language properly.

Scholars on the other side of the debate don't find the differences in how people talk convincing. All our linguistic utterances are sparse, encoding only a small part of the information we have available. Just because English speakers don't include the same information in their verbs that Russian and Turkish speakers do doesn't mean that English speakers aren't paying attention to the same things; all it means is that they're not talking about them. It's possible that everyone thinks the same way, notices the same things, but just talks differently.

Believers in cross-linguistic differences counter that everyone does not pay attention to the same things: if everyone did, one might think it would be easy to learn to speak other languages. Unfortunately, learning a new language (especially one not closely related to those you know) is never easy; it seems to require paying attention to a new set of distinctions. Whether it's distinguishing modes of being in Spanish, evidentiality in Turkish, or aspect in Russian, learning to speak these languages requires something more than just learning vocabulary: it requires paying attention to the right things in the world so that you have the correct information to include in what you say.

Such a priori arguments about whether or not language shapes thought have gone in circles for centuries, with some arguing that it's impossible for language to shape thought and others arguing that it's impossible for language not to shape thought. Recently my group and others have figured out ways to empirically test some of the key questions in this ancient debate, with fascinating results. So instead of arguing about what must be true or what can't be true, let's find out what is true.

Follow me to Pormpuraaw, a small Aboriginal community on the western edge of Cape York, in northern Australia. I came here because of the way the locals, the Kuuk Thaayorre, talk about space. Instead of words like "right," "left," "forward," and "back," which, as commonly used in English, define space relative to an observer, the Kuuk Thaayorre, like many other Aboriginal groups, use cardinal-direction terms — north, south, east, and west — to define space.1 This is done at all scales, which means you have to say things like "There's an ant on your southeast leg" or "Move the cup to the north northwest a little bit." One obvious consequence of speaking such a language is that you have to stay oriented at all times, or else you cannot speak properly. The normal greeting in Kuuk Thaayorre is "Where are you going?" and the answer should be something like " Southsoutheast, in the middle distance." If you don't know which way you're facing, you can't even get past "Hello."

The result is a profound difference in navigational ability and spatial knowledge between speakers of languages that rely primarily on absolute reference frames (like Kuuk Thaayorre) and languages that rely on relative reference frames (like English).2 Simply put, speakers of languages like Kuuk Thaayorre are much better than English speakers at staying oriented and keeping track of where they are, even in unfamiliar landscapes or inside unfamiliar buildings. What enables them — in fact, forces them — to do this is their language. Having their attention trained in this way equips them to perform navigational feats once thought beyond human capabilities. Because space is such a fundamental domain of thought, differences in how people think about space don't end there. People rely on their spatial knowledge to build other, more complex, more abstract representations. Representations of such things as time, number, musical pitch, kinship relations, morality, and emotions have been shown to depend on how we think about space. So if the Kuuk Thaayorre think differently about space, do they also think differently about other things, like time? This is what my collaborator Alice Gaby and I came to Pormpuraaw to find out.

To test this idea, we gave people sets of pictures that showed some kind of temporal progression (e.g., pictures of a man aging, or a crocodile growing, or a banana being eaten). Their job was to arrange the shuffled photos on the ground to show the correct temporal order. We tested each person in two separate sittings, each time facing in a different cardinal direction. If you ask English speakers to do this, they'll arrange the cards so that time proceeds from left to right. Hebrew speakers will tend to lay out the cards from right to left, showing that writing direction in a language plays a role.3 So what about folks like the Kuuk Thaayorre, who don't use words like "left" and "right"? What will they do?

The Kuuk Thaayorre did not arrange the cards more often from left to right than from right to left, nor more toward or away from the body. But their arrangements were not random: there was a pattern, just a different one from that of English speakers. Instead of arranging time from left to right, they arranged it from east to west. That is, when they were seated facing south, the cards went left to right. When they faced north, the cards went from right to left. When they faced east, the cards came toward the body and so on. This was true even though we never told any of our subjects which direction they faced. The Kuuk Thaayorre not only knew that already (usually much better than I did), but they also spontaneously used this spatial orientation to construct their representations of time.

People's ideas of time differ across languages in other ways. For example, English speakers tend to talk about time using horizontal spatial metaphors (e.g., "The best is ahead of us," "The worst is behind us"), whereas Mandarin speakers have a vertical metaphor for time (e.g., the next month is the "down month" and the last month is the "up month"). Mandarin speakers talk about time vertically more often than English speakers do, so do Mandarin speakers think about time vertically more often than English speakers do? Imagine this simple experiment. I stand next to you, point to a spot in space directly in front of you, and tell you, "This spot, here, is today. Where would you put yesterday? And where would you put tomorrow?" When English speakers are asked to do this, they nearly always point horizontally. But Mandarin speakers often point vertically, about seven or eight times more often than do English speakers.4

Even basic aspects of time perception can be affected by language. For example, English speakers prefer to talk about duration in terms of length (e.g., "That was a short talk," "The meeting didn't take long"), while Spanish and Greek speakers prefer to talk about time in terms of amount, relying more on words like "much" "big", and "little" rather than "short" and "long" Our research into such basic cognitive abilities as estimating duration shows that speakers of different languages differ in ways predicted by the patterns of metaphors in their language. (For example, when asked to estimate duration, English speakers are more likely to be confused by distance information, estimating that a line of greater length remains on the test screen for a longer period of time, whereas Greek speakers are more likely to be confused by amount, estimating that a container that is fuller remains longer on the screen.)5

An important question at this point is: Are these differences caused by language per se or by some other aspect of culture? Of course, the lives of English, Mandarin, Greek, Spanish, and Kuuk Thaayorre speakers differ in a myriad of ways. How do we know that it is language itself that creates these differences in thought and not some other aspect of their respective cultures?

One way to answer this question is to teach people new ways of talking and see if that changes the way they think. In our lab, we've taught English speakers different ways of talking about time. In one such study, English speakers were taught to use size metaphors (as in Greek) to describe duration (e.g., a movie is larger than a sneeze), or vertical metaphors (as in Mandarin) to describe event order. Once the English speakers had learned to talk about time in these new ways, their cognitive performance began to resemble that of Greek or Mandarin speakers. This suggests that patterns in a language can indeed play a causal role in constructing how we think.6 In practical terms, it means that when you're learning a new language, you're not simply learning a new way of talking, you are also inadvertently learning a new way of thinking. Beyond abstract or complex domains of thought like space and time, languages also meddle in basic aspects of visual perception — our ability to distinguish colors, for example. Different languages divide up the color continuum differently: some make many more distinctions between colors than others, and the boundaries often don't line up across languages.

To test whether differences in color language lead to differences in color perception, we compared Russian and English speakers' ability to discriminate shades of blue. In Russian there is no single word that covers all the colors that English speakers call "blue." Russian makes an obligatory distinction between light blue (goluboy) and dark blue (siniy). Does this distinction mean that siniy blues look more different from goluboy blues to Russian speakers? Indeed, the data say yes. Russian speakers are quicker to distinguish two shades of blue that are called by the different names in Russian (i.e., one being siniy and the other being goluboy) than if the two fall into the same category.

For English speakers, all these shades are still designated by the same word, "blue," and there are no comparable differences in reaction time.

Further, the Russian advantage disappears when subjects are asked to perform a verbal interference task (reciting a string of digits) while making color judgments but not when they're asked to perform an equally difficult spatial interference task (keeping a novel visual pattern in memory). The disappearance of the advantage when performing a verbal task shows that language is normally involved in even surprisingly basic perceptual judgments — and that it is language per se that creates this difference in perception between Russian and English speakers.

When Russian speakers are blocked from their normal access to language by a verbal interference task, the differences between Russian and English speakers disappear.

Even what might be deemed frivolous aspects of language can have far-reaching subconscious effects on how we see the world. Take grammatical gender. In Spanish and other Romance languages, nouns are either masculine or feminine. In many other languages, nouns are divided into many more genders ("gender" in this context meaning class or kind). For example, some Australian Aboriginal languages have up to sixteen genders, including classes of hunting weapons, canines, things that are shiny, or, in the phrase made famous by cognitive linguist George Lakoff, "women, fire, and dangerous things."

What it means for a language to have grammatical gender is that words belonging to different genders get treated differently grammatically and words belonging to the same grammatical gender get treated the same grammatically. Languages can require speakers to change pronouns, adjective and verb endings, possessives, numerals, and so on, depending on the noun's gender. For example, to say something like "my chair was old" in Russian (moy stul bil' stariy), you'd need to make every word in the sentence agree in gender with "chair" (stul), which is masculine in Russian. So you'd use the masculine form of "my," "was," and "old." These are the same forms you'd use in speaking of a biological male, as in "my grandfather was old." If, instead of speaking of a chair, you were speaking of a bed (krovat'), which is feminine in Russian, or about your grandmother, you would use the feminine form of "my," "was," and "old."

Does treating chairs as masculine and beds as feminine in the grammar make Russian speakers think of chairs as being more like men and beds as more like women in some way? It turns out that it does. In one study, we asked German and Spanish speakers to describe objects having opposite gender assignment in those two languages. The descriptions they gave differed in a way predicted by grammatical gender. For example, when asked to describe a "key" — a word that is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish — the German speakers were more likely to use words like "hard," "heavy," "jagged," "metal," "serrated," and "useful," whereas Spanish speakers were more likely to say "golden," "intricate," "little," "lovely," "shiny," and "tiny." To describe a "bridge," which is feminine in German and masculine in Spanish, the German speakers said "beautiful," "elegant," "fragile," "peaceful," "pretty," and "slender," and the Spanish speakers said "big," "dangerous," "long," "strong," "sturdy," and "towering." This was true even though all testing was done in English, a language without grammatical gender. The same pattern of results also emerged in entirely nonlinguistic tasks (e.g., rating similarity between pictures). And we can also show that it is aspects of language per se that shape how people think: teaching English speakers new grammatical gender systems influences mental representations of objects in the same way it does with German and Spanish speakers. Apparently even small flukes of grammar, like the seemingly arbitrary assignment of gender to a noun, can have an effect on people's ideas of concrete objects in the world.7

In fact, you don't even need to go into the lab to see these effects of language; you can see them with your own eyes in an art gallery. Look at some famous examples of personification in art — the ways in which abstract entities such as death, sin, victory, or time are given human form. How does an artist decide whether death, say, or time should be painted as a man or a woman? It turns out that in 85 percent of such personifications, whether a male or female figure is chosen is predicted by the grammatical gender of the word in the artist's native language. So, for example, German painters are more likely to paint death as a man, whereas Russian painters are more likely to paint death as a woman.

The fact that even quirks of grammar, such as grammatical gender, can affect our thinking is profound. Such quirks are pervasive in language; gender, for example, applies to all nouns, which means that it is affecting how people think about anything that can be designated by a noun. That's a lot of stuff!

I have described how languages shape the way we think about space, time, colors, and objects. Other studies have found effects of language on how people construe events, reason about causality, keep track of number, understand material substance, perceive and experience emotion, reason about other people's minds, choose to take risks, and even in the way they choose professions and spouses.8 Taken together, these results show that linguistic processes are pervasive in most fundamental domains of thought, unconsciously shaping us from the nuts and bolts of cognition and perception to our loftiest abstract notions and major life decisions. Language is central to our experience of being human, and the languages we speak profoundly shape the way we think, the way we see the world, the way we live our lives.

1 S. C. Levinson and D. P. Wilkins, eds., Grammars of Space: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

2 Levinson, Space in Language and Cognition: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

3 B. Tversky et al., “ Cross-Cultural and Developmental Trends in Graphic Productions,” Cognitive Psychology 23(1991): 515–7; O. Fuhrman and L. Boroditsky, “Mental Time-Lines Follow Writing Direction: Comparing English and Hebrew Speakers.” Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (2007): 1007–10.

4 L. Boroditsky, "Do English and Mandarin Speakers Think Differently About Time?" Proceedings of the 48th Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society (2007): 34.

5 D. Casasanto et al., "How Deep Are Effects of Language on Thought? Time Estimation in Speakers of English, Indonesian Greek, and Spanish," Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (2004): 575–80.

6 Ibid., "How Deep Are Effects of Language on Thought? Time Estimation in Speakers of English and Greek" (in review); L. Boroditsky, "Does Language Shape Thought? English and Mandarin Speakers' Conceptions of Time." Cognitive Psychology 43, no. 1(2001): 1–22.

7 L. Boroditsky et al. "Sex, Syntax, and Semantics," in D. Gentner and S. Goldin-Meadow, eds., Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Cognition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 61–79.

8 L. Boroditsky, "Linguistic Relativity," in L. Nadel ed., Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science (London: MacMillan, 2003), 917–21; B. W. Pelham et al., "Why Susie Sells Seashells by the Seashore: Implicit Egotism and Major Life Decisions." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82, no. 4(2002): 469–86; A. Tversky & D. Kahneman, "The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice." Science 211(1981): 453–58; P. Pica et al., "Exact and Approximate Arithmetic in an Amazonian Indigene Group." Science 306(2004): 499–503; J. G. de Villiers and P. A. de Villiers, "Linguistic Determinism and False Belief," in P. Mitchell and K. Riggs, eds., Children's Reasoning and the Mind (Hove, UK: Psychology Press, in press); J. A. Lucy and S. Gaskins, "Interaction of Language Type and Referent Type in the Development of Nonverbal Classification Preferences," in Gentner and Goldin-Meadow, 465–92; L. F. Barrett et al., "Language as a Context for Emotion Perception," Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11(2007): 327–32.

What's Related

Beyond Edge

Conversations at edge.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 19 June 2024

Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought

- Evelina Fedorenko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3823-514X 1 , 2 ,

- Steven T. Piantadosi 3 &

- Edward A. F. Gibson 1

Nature volume 630 , pages 575–586 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

893 Altmetric

Metrics details

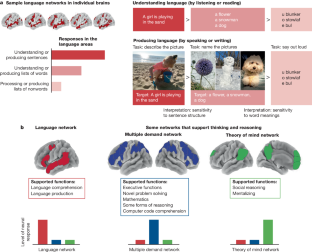

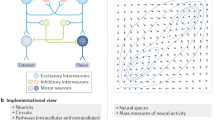

- Human behaviour

Language is a defining characteristic of our species, but the function, or functions, that it serves has been debated for centuries. Here we bring recent evidence from neuroscience and allied disciplines to argue that in modern humans, language is a tool for communication, contrary to a prominent view that we use language for thinking. We begin by introducing the brain network that supports linguistic ability in humans. We then review evidence for a double dissociation between language and thought, and discuss several properties of language that suggest that it is optimized for communication. We conclude that although the emergence of language has unquestionably transformed human culture, language does not appear to be a prerequisite for complex thought, including symbolic thought. Instead, language is a powerful tool for the transmission of cultural knowledge; it plausibly co-evolved with our thinking and reasoning capacities, and only reflects, rather than gives rise to, the signature sophistication of human cognition.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The language network as a natural kind within the broader landscape of the human brain

An investigation across 45 languages and 12 language families reveals a universal language network

Two views on the cognitive brain

Barham, L. & Everett, D. Semiotics and the origin of language in the Lower Palaeolithic. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 28 , 535–579 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Hockett, C. F. The origin of speech. Sci. Am. 203 , 88–97 (1960). A classic overview of the relationship between key features of human language and communication systems found in other species, with a focus on distinctive and shared properties .

Jackendoff, R. & Pinker, S. The faculty of language: what’s special about it? Cognition 95 , 201–236 (2005).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hurford, J. R. Language in the Light of Evolution: Volume 1, The Origins of Meaning (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

Kirby, S., Cornish, H. & Smith, K. Cumulative cultural evolution in the laboratory: an experimental approach to the origins of structure in human language. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 10681–10686 (2008). This behavioural investigation introduces an experimental paradigm based on iterated learning of artificial languages for studying the cultural evolution of language; the findings suggest that languages evolve to maximize their transmissibility by becoming easier to learn and more structured .

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Seyfarth, R. M. & Cheney, D. L. The Social Origins of Language (Princeton Univ. Press, 2018).

Gibson, E. et al. How efficiency shapes human language. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23 , 389–407 (2019).

Chomsky, N. The Minimalist Program (MIT Press, 1995).

Carruthers, P. The cognitive functions of language. Behav. Brain Sci. 25 , 657–674 (2002). This comprehensive review discusses diverse language-for-thought views and puts forward a specific proposal whereby language has a critical role in cross-domain integration .

Gentner, D. & Goldin-Meadow, S. Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Thought (MIT Press, 2003).

Majid, A., Bowerman, M., Kita, S., Haun, D. B. & Levinson, S. C. Can language restructure cognition? The case for space. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8 , 108–114 (2004).

Vygotsky, L. S. Thought and Language (MIT Press, 2012).

Lupyan, G. The centrality of language in human cognition. Lang. Learn. 66 , 516–553 (2016).

Davidson, D. in Mind and Language (ed. Guttenplan, S.) 1975–1977 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1975).

Dummett, M. Origins of Analytical Philosophy (Harvard Univ. Press, 1994).

Gleitman, L. & Papafragou, A. in The Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning (eds Holyoak, K. J. & Morrison, R. G.) 633–661 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

de Villiers, J. in Understanding Other Minds: Perspectives from Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience (eds Baron-Cohen, S. et al.) 83–123 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2000).

Gentner, D. in Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Thought (eds Gentner, D. & Goldin-Meadow, S.) 3–14 (MIT Press, 2003). This position piece articulates one version of a language-for-thought hypothesis, whereby human intelligence is due to a combination of our analogical reasoning ability, possession of symbolic representations, and the ability of relational language to improve analogical reasoning abilities .

Buller, D. J. Adapting Minds: Evolutionary Psychology and the Persistent Quest for Human Nature (MIT Press, 2005).

Gould, S. J. & Vrba, E. S. Exaptation—a missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology 8 , 4–15 (1982).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27 , 379–423 (1948). This article introduces a formal framework for systems of information transfer, with core concepts such as channel capacity, and lays a foundation for the field of information theory .

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Goldberg, A. E. Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure (Univ. Chicago Press, 1995).

Jackendoff, R. Foundations of Language: Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2002).

Geschwind, N. The organization of language and the brain: language disorders after brain damage help in elucidating the neural basis of verbal behavior. Science 170 , 940–944 (1970).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Friederici, A. D. Towards a neural basis of auditory sentence processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6 , 78–84 (2002).

Bates, E. et al. Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping. Nat. Neurosci. 6 , 448–450 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hagoort, P. The neurobiology of language beyond single-word processing. Science 366 , 55–58 (2019).

Fedorenko, E., Ivanova, A. I. & Regev, T. I. The language network as a natural kind within the broader landscape of the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 25 , 289–312 (2024).

Neville, H. J. et al. Cerebral organization for language in deaf and hearing subjects: biological constraints and effects of experience. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95 , 922–929 (1998).

Fedorenko, E., Hsieh, P.-J., Nieto-Castañon, A., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Kanwisher, N. A new method for fMRI investigations of language: defining ROIs functionally in individual subjects. J. Neurophysiol. 104 , 1177–1194 (2010).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vagharchakian, L., Dehaene-Lambertz, G., Pallier, C. & Dehaene, S. A temporal bottleneck in the language comprehension network. J. Neurosci. 32 , 9089–9102 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Regev, M., Honey, C. J., Simony, E. & Hasson, U. Selective and invariant neural responses to spoken and written narratives. J. Neurosci. 33 , 15978–15988 (2013).

Hu, J. et al. Precision fMRI reveals that the language-selective network supports both phrase-structure building and lexical access during language production. Cereb. Cortex 33 , 4384–4404 (2022).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Menenti, L., Gierhan, S. M. E., Segaert, K. & Hagoort, P. Shared language: overlap and segregation of the neuronal infrastructure for speaking and listening revealed by functional MRI. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 1173–1182 (2011). This fMRI investigation establishes that language comprehension and language production draw on the same brain areas in the left frontal and temporal cortex .

Hauser, M. D., Chomsky, N. & Fitch, W. T. The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science 298 , 1569–1579 (2002).

Pallier, C., Devauchelle, A. D. & Dehaene, S. Cortical representation of the constituent structure of sentences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 2522–2527 (2011).

Bozic, M., Fonteneau, E., Su, L. & Marslen‐Wilson, W. D. Grammatical analysis as a distributed neurobiological function. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36 , 1190–1201 (2015).

Rodd, J. M., Vitello, S., Woollams, A. M. & Adank, P. Localising semantic and syntactic processing in spoken and written language comprehension: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Brain Lang. 141 , 89–102 (2015).

Blank, I., Balewski, Z., Mahowald, K. & Fedorenko, E. Syntactic processing is distributed across the language system. NeuroImage 127 , 307–323 (2016).

Fedorenko, E. et al. Neural correlate of the construction of sentence meaning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , E6256–E6262 (2016).

Nelson, M. J. et al. Neurophysiological dynamics of phrase-structure building during sentence processing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , E3669–E3678 (2017).

Fedorenko, E., Blank, I. A., Siegelman, M. & Mineroff, Z. Lack of selectivity for syntax relative to word meanings throughout the language network. Cognition 203 , 104348 (2020). This fMRI investigation establishes that every part of the language network that is sensitive to syntactic structure building is also sensitive to word meanings and comprehensively reviews literature relevant to the syntax selectivity debate .

Giglio, L., Ostarek, M. O., Weber, K. & Hagoort, P. Commonalities and asymmetries in the neurobiological infrastructure for language production and comprehension. Cereb. Cortex 32 , 1405–1418 (2022).

Heilbron, M., Armeni, K., Schoffelen, J. M., Hagoort, P. & De Lange, F. P. A hierarchy of linguistic predictions during natural language comprehension. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119 , e2201968119 (2022).

Shain, C., Blank, I. A., Fedorenko, E., Gibson, E. & Schuler, W. Robust effects of working memory demand during naturalistic language comprehension in language-selective cortex. J. Neurosci. 42 , 7412–7430 (2022).

Desbordes, T. et al. Dimensionality and ramping: signatures of sentence integration in the dynamics of brains and deep language models. J. Neurosci. 43 , 5350–5364 (2023).

Shain, C. et al. Distributed sensitivity to syntax and semantics throughout the language network. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22 , 1–43 (2024). This fMRI investigation establishes distributed sensitivity to cognitive demands associated with lexical access, syntactic structure building and semantic composition across the language network.

Tuckute, G. et al. Driving and suppressing the human language network using large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8 , 544–561 (2024).

Gentner, D. Structure-mapping: a theoretical framework for analogy. Cogn. Sci. 7 , 155–170 (1983).

Google Scholar

Duncan, J. How Intelligence Happens (Yale Univ. Press, 2012).

Varley, R. A., Klessinger, N. J., Romanowski, C. A. & Siegal, M. Agrammatic but numerate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 3519–3524 (2005). Patients with acquired damage to the language network display aphasia and linguistic deficits (including severe grammatical difficulties) but perform at the level of neurotypical control participants on diverse numerical reasoning tasks .

Klessinger, N., Szczerbinski, M. & Varley, R. Algebra in a man with severe aphasia. Neuropsychologia 45 , 1642–1648 (2007).

Lecours, A. & Joanette, Y. Linguistic and other psychological aspects of paroxysmal aphasia. Brain and Language 10 , 1–23 (1980).

Kertesz, A. in Thought Without Language (ed. Weiskrantz, L.) 451–463 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1988).

Varley, R. & Siegal, M. Evidence for cognition without grammar from causal reasoning and ‘theory of mind’ in an agrammatic aphasic patient. Curr. Biol. 10 , 723–726 (2000).

Siegal, M., Varley, R. & Want, S. C. Mind over grammar: reasoning in aphasia and development. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5 , 296–301 (2001).

Varley, R. In Cognitive Bases of Science (eds Carruthers, P. et al.) 99–116 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002).

Woolgar, A., Duncan, J., Manes, F. & Fedorenko, E. Fluid intelligence is supported by the multiple-demand system not the language system. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2 , 200–204 (2018).

Dronkers, N. F., Ludy, C. A. & Redfern, B. B. Pragmatics in the absence of verbal language: descriptions of a severe aphasic and a language-deprived adult. J. Neurolinguistics 11 , 179–190 (1998).

Varley, R., Siegal, M. & Want, S. C. Severe impairment in grammar does not preclude theory of mind. Neurocase 7 , 489–493 (2001).

Apperly, I. A., Samson, D., Carroll, N., Hussain, S. & Humphreys, G. Intact first-and second-order false belief reasoning in a patient with severely impaired grammar. Soc. Neurosci. 1 , 334–348 (2006). A person with acquired damage to the language network and consequent aphasia exhibits linguistic deficits but performs at the level of neurotypical control participants on theory of mind tasks .

Willems, R. M., Benn, Y., Hagoort, P., Toni, I. & Varley, R. Communicating without a functioning language system: Implications for the role of language in mentalizing. Neuropsychologia 49 , 3130–3135 (2011).

Bek, J., Blades, M., Siegal, M. & Varley, R. Language and spatial reorientation: evidence from severe aphasia. J. Exp. Psychol. 36 , 646 (2010).

Caramazza, A., Berndt, R. S. & Brownell, H. H. The semantic deficit hypothesis: Perceptual parsing and object classification by aphasic patients. B. Lang. 15 , 161–189 (1982).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Chertkow, H., Bub, D., Deaudon, C. & Whitehead, V. On the status of object concepts in aphasia. Brain Lang. 58 , 203–232 (1997).

Saygın, A. P., Wilson, S. M., Dronkers, N. F. & Bates, E. Action comprehension in aphasia: linguistic and non-linguistic deficits and their lesion correlates. Neuropsychologia 42 , 1788–1804 (2004).

Jefferies, E. & Lambon Ralph, M. A. Semantic impairment in stroke aphasia versus semantic dementia: a case-series comparison. Brain 129 , 2132–2147 (2006).

Dickey, M. W. & Warren, T. The influence of event-related knowledge on verb-argument processing in aphasia. Neuropsychologia 67 , 63–81 (2015).

Ivanova, A. A. et al. The language network is recruited but not required for nonverbal event semantics. Neurobiol. Lang. 2 , 176–201 (2021). In this fMRI study, semantic processing of event pictures in neurotypical individuals engages the language network, but less than verbal descriptions of the same events; however, individuals with acquired damage to the language network and consequent aphasia perform at the level of neurotypical control participants on a non-verbal semantic task .

Benn, Y. et al. The language network is not engaged in object categorization. Cereb. Cortex 33 , 10380–10400 (2023).

Varley, R. Reason without much language. Lang. Sci. 46 , 232–244 (2014).

Dehaene, S., Spelke, E., Pinel, P., Stanescu, R. & Tsivkin, S. Sources of mathematical thinking: behavioral and brain-imaging evidence. Science 284 , 970–974 (1999).

Hermer, L. & Spelke, E. Modularity and development: the case of spatial reorientation. Cognition 61 , 195–232 (1996).

Lupyan, G. Extracommunicative functions of language: verbal interference causes selective categorization impairments. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 16 , 711–718 (2009).

Braga, R. M., DiNicola, L. M., Becker, H. C. & Buckner, R. L. Situating the left-lateralized language network in the broader organization of multiple specialized large-scale distributed networks. J. Neurophysiol. 124 , 1415–1448 (2020). This fMRI investigation of the language network establishes this network as one of the intrinsic large-scale networks in the human brain, distinct from nearby cognitive networks .

Fedorenko, E. & Blank, I. A. Broca’s area is not a natural kind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24 , 270–284 (2020).

Fedorenko, E., Behr, M. K. & Kanwisher, N. Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 16428–16433 (2011). This fMRI investigation finds that arithmetic addition, demanding executive function tasks and music processing do not engage the language areas, thus establishing their selectivity for linguistic input over non-linguistic inputs and tasks .

Monti, M. M., Parsons, L. M. & Osherson, D. N. Thought beyond language: neural dissociation of algebra and natural language. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 914–922 (2012).

Amalric, M. & Dehaene, S. A distinct cortical network for mathematical knowledge in the human brain. NeuroImage 189 , 19–31 (2019).

Monti, M. M., Osherson, D. N., Martinez, M. J. & Parsons, L. M. Functional neuroanatomy of deductive inference: a language-independent distributed network. NeuroImage 37 , 1005–1016 (2007).

Monti, M. M., Parsons, L. M. & Osherson, D. N. The boundaries of language and thought in deductive inference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 12554–12559 (2009). This fMRI investigation finds largely non-overlapping activations of brain regions to language processing and logical processing, thus establishing the selectivity of language areas for linguistic input over logic statements .

Ivanova, A. A. et al. Comprehension of computer code relies primarily on domain-general executive brain regions. eLife 9 , e58906 (2020).

Liu, Y. F., Kim, J., Wilson, C. & Bedny, M. Computer code comprehension shares neural resources with formal logical inference in the fronto-parietal network. eLife 9 , e59340 (2020).

Paunov, A. M., Blank, I. A. & Fedorenko, E. Functionally distinct language and theory of mind networks are synchronized at rest and during language comprehension. J. Neurophysiol. 121 , 1244–1265 (2019).

Paunov, A. M. et al. Differential tracking of linguistic vs. mental state content in naturalistic stimuli by language and theory of mind (ToM) brain networks. Neurobiol. Lang. 3 , 413–440 (2022).

Shain, C., Paunov, A., Chen, X., Lipkin, B. & Fedorenko, E. No evidence of theory of mind reasoning in the human language network. Cereb. Cortex 33 , 6299–6319 (2023).

Sueoka, Y., Paunov, A., Ivanova, A., Blank, I. A. & Fedorenko, E. The language network reliably “tracks” naturalistic meaningful non-verbal stimuli. Neurobiol. Lang. https://doi.org/10.1162/nol_a_00135 (2024).

Piaget, J. The Language and Thought of the Child (Harcourt Brace, 1926).

Gentner, D. & Loewenstein, J. in Language, Literacy, and Cognitive Development: The Development and Consequences of Symbolic Communication (eds Amsel, E. & Byrnes, J. P.) 89–126 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002).

Appleton, M. & Reddy, V. Teaching three year‐olds to pass false belief tests: a conversational approach. Soc. Dev. 5 , 275–291 (1996).

Slaughter, V. & Gopnik, A. Conceptual coherence in the child’s theory of mind: training children to understand belief. Child Dev. 67 , 2967–2988 (1996).

Hiersche, K. J., Schettini, E., Li, J. & Saygin, Z. M. (2022). Functional dissociation of the language network and other cognition in early childhood. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.11.503597 (2023).

Hiersche, K. J. Functional Organization and Modularity of the Superior Temporal Lobe in Children . Masters thesis, The Ohio State University (2023).

Hall, W. C. What you don’t know can hurt you: the risk of language deprivation by impairing sign language development in deaf children. Matern. Child Health J. 21 , 961–965 (2017).

Hall, M. L., Hall, W. C. & Caselli, N. K. Deaf children need language, not (just) speech. First Lang. 39 , 367–395 (2019).

Bedny, M. & Saxe, R. Insights into the origins of knowledge from the cognitive neuroscience of blindness. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 29 , 56–84 (2012).

Grand, G., Blank, I. A., Pereira, F. & Fedorenko, E. Semantic projection recovers rich human knowledge of multiple object features from word embeddings. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6 , 975–987 (2022).

Jackendoff, R. How language helps us think. Pragmat. Cogn. 4 , 1–34 (1996).

Jackendoff. R. The User’s Guide to Meaning (MIT Press, 2012).

Curtiss, S. Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of a Modern-day Wild Child (Academic Press, 1977).

Peterson, C. C. & Siegal, M. Representing inner worlds: theory of mind in autistic, deaf, and normal hearing children. Psychol. Sci. 10 , 126–129 (1999).

Richardson, H. et al. Reduced neural selectivity for mental states in deaf children with delayed exposure to sign language. Nat. Commun. 11 , 3246 (2020).

Spelke, E. S. What Babies Know: Core Knowledge and Composition , Vol. 1 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2022).

Cheney, D. L. & Seyfarth, R. M. How Monkeys See the World: Inside the Mind of Another Species (Univ. Chicago Press, 1990).

Herrmann, E., Call, J., Hernández-Lloreda, M. V., Hare, B. & Tomasello, M. Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: the cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science 317 , 1360–1366 (2007).

Tomasello, M. & Herrmann, E. Ape and human cognition: what’s the difference? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 19 , 3–8 (2010).

Fischer, J. Monkeytalk: Inside the Worlds and Minds of Primates (Univ. Chicago Press, 2017).

Krupenye, C. & Call, J. Theory of mind in animals: current and future directions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 10 , e1503 (2019).

Shimizu, T. Why can birds be so smart? Background, significance, and implications of the revised view of the avian brain. Comparat. Cogn. Behav. Rev. 4 , 103–115 (2009).

Güntürkün, O. & Bugnyar, T. Cognition without cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20 , 291–303 (2016).

Hart, B. L., Hart, L. A. & Pinter-Wollman, N. Large brains and cognition: where do elephants fit in? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32 , 86–98 (2008).

Godfrey-Smith, P. Other Minds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life (William Collins, 2016).

Schnell, A. K., Amodio, P., Boeckle, M. & Clayton, N. S. How intelligent is a cephalopod? Lessons from comparative cognition. Biol. Rev. 96 , 162–178 (2021).

Gallistel, C. R. Prelinguistic thought. Lang. Learn. Dev. 7 , 253–262 (2011).

Fitch, W. T. Animal cognition and the evolution of human language: why we cannot focus solely on communication. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375 , 20190046 (2020).

Yamada, J. E. & Marshall, J. C. Laura: A Case Study for the Modularity of Language (MIT Press, 1990).

Rondal, J. A. Exceptional Language Development in Down Syndrome (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995).

Bellugi, U., Lichtenberger, L., Jones, W., Lai, Z. & St George, M. The neurocognitive profile of Williams syndrome: a complex pattern of strengths and weaknesses. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12 , 7–29 (2000).

Little, B. et al. Language in schizophrenia and aphasia: the relationship with non-verbal cognition and thought disorder. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 24 , 389–405 (2019).

Mahowald, K. et al. Dissociating language and thought in large language models. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28 , 517–540(2024).

Chomsky, N., Belleti, A. & Rizzi, L. in On Nature and Language (eds Belleti, A. & Rizzi, L.) 92–161 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002).

Schwartz, J. L., Boë, L. J., Vallée, N. & Abry, C. The dispersion–focalization theory of vowel systems. J. Phonetics 25 , 255–286 (1997).

Diehl, R. L. Acoustic and auditory phonetics: the adaptive design of speech sound systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 363 , 965–978 (2008).

Everett, C., Blasi, D. E. & Roberts, S. G. Climate, vocal folds, and tonal languages: Connecting the physiological and geographic dots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 1322–1327 (2015).

Blasi, D. E. et al. Human sound systems are shaped by post-Neolithic changes in bite configuration. Science 363 , eaav3218 (2019).

Dautriche, I., Mahowald, K., Gibson, E., Christophe, A. & Piantadosi, S. T. Words cluster phonetically beyond phonotactic regularities. Cognition 163 , 128–145 (2017).

Piantadosi, S. T., Tily, H. & Gibson, E. Word lengths are optimized for efficient communication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 3526–3529 (2011).

Levelt, W. J. Speaking: From Intention to Articulation (MIT Press, 1993).

Kemp, C. & Regier, T. Kinship categories across languages reflect general communicative principles. Science 336 , 1049–1054 (2012). This study provides a computational demonstration that the kinship systems across world’s languages trade off between simplicity and informativeness in a near-optimal way, and argue that these principles also characterize other category systems .

Gibson, E. et al. Color naming across languages reflects color use. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 10785–10790 (2017).

Zaslavsky, N., Kemp, C., Regier, T. & Tishby, N. Efficient compression in color naming and its evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 7937–7942 (2018).

Kemp, C., Gaby, A. & Regier, T. Season naming and the local environment. Proc. 41st Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 539–545 (2019).

Xu, Y., Liu, E. & Regier, T. Numeral systems across languages support efficient communication: From approximate numerosity to recursion. Open Mind 4 , 57–70 (2020).

Denić, M., Steinert-Threlkeld, S. & Szymanik, J. Complexity/informativeness trade-off in the domain of indefinite pronouns. Semant. Linguist. Theor. 30 , 166–184 (2021).

Mollica, F. et al. The forms and meanings of grammatical markers support efficient communication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , e2025993118 (2021).

van de Pol, I., Lodder, P., van Maanen, L., Steinert-Threlkeld, S. & Szymanik, J. Quantifiers satisfying semantic universals have shorter minimal description length. Cognition 232 , 105150 (2023).

Clark, H. H. in Context in Language Learning and Language Understanding (eds Malmkj’r, K. & Williams, J.) 63–87) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998).

Winter, B., Perlman, M. & Majid, A. Vision dominates in perceptual language: English sensory vocabulary is optimized for usage. Cognition 179 , 213–220 (2018).

von Humboldt, W. Uber die Verschiedenheit des Menschlichen Sprachbaues (1836).

Hurford, J. R. Linguistic Evolution Through Language Acquisition: Formal and Computational Models (ed. Briscoe, E.) 301–344 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002).

Smith, K., Brighton, H. & Kirby, S. Complex systems in language evolution: the cultural emergence of compositional structure. Adv. Complex Syst. 6 , 537–558 (2003).

Piantadosi, S. T. & Fedorenko, E. Infinitely productive language can arise from chance under communicative pressure. J. Lang. Evol. 2 , 141–147 (2017).

Gibson, E. Linguistic complexity: locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68 , 1–76 (1998).

Lewis, R. L., Vasishth, S. & Van Dyke, J. A. Computational principles of working memory in sentence comprehension. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10 , 447–454 (2006).

Liu, H. Dependency distance as a metric of language comprehension difficulty. J. Cogn. Sci. 9 , 151–191 (2008).

ADS CAS Google Scholar

Futrell, R., Mahowald, K. & Gibson, E. Large-scale evidence of dependency length minimization in 37 languages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 10336–10341 (2015). This investigation of syntactic dependency lengths across 37 diverse languages suggests that dependencies are predominantly local cross-linguistically, presumably because non-local dependencies are cognitively costly in both production and comprehension .

Dryer, M. S. The Greenbergian word order correlations. Language 68 , 81–138 (1992).

Hahn, M., Jurafsky, D. & Futrell, R. Universals of word order reflect optimization of grammars for efficient communication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 2347–2353 (2020).

Goldin-Meadow, S., Wing, C. S., Özyürek, A. & Mylander, C. The natural order of events: how speakers of different languages represent events nonverbally. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 9163–9168 (2008).

Senghas, A., Kita, S. & Ozyürek, A. Children creating core properties of language: evidence from an emerging sign language in Nicaragua. Science 305 , 1779–1782 (2004).

Sandler, W., Meir, I., Padden, C. & Aronoff, M. The emergence of grammar: systematic structure in a new language. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 2661–2665 (2005).

Gibson, E. et al. A noisy-channel account of crosslinguistic word-order variation. Psychol. Sci. 24 , 1079–1088 (2013).

Levy, R. A noisy-channel model of human sentence comprehension under uncertain input. In Proc. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing 234–243 (2008).

Gibson, E., Bergen, L. & Piantadosi, S. T. Rational integration of noisy evidence and prior semantic expectations in sentence interpretation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 8051–8056 (2013). This behavioural investigation demonstrates that language comprehension is robust to noise: in the presence of corrupt linguistic input, listeners and readers rely on a combination of prior expectations about messages that are likely to be communicated and knowledge of how linguistic signals can get corrupted by noise .

Futrell, R., Levy, R. P. & Gibson, E. Dependency locality as an explanatory principle for word order. Language 96 , 371–412 (2020).

Hahn, M. & Xu, Y. Crosslinguistic word order variation reflects evolutionary pressures of dependency and information locality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119 , e2122604119 (2022).

Hahn, M., Futrell, R., Levy, R. & Gibson, E. A resource-rational model of human processing of recursive linguistic structure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119 , e2122602119 (2022).

Piantadosi, S. T., Tily, H. & Gibson, E. The communicative function of ambiguity in language. Cognition 122 , 280–291 (2012).

Quijada, J. A grammar of the Ithkuil language—introduction. ithkuil.net https://ithkuil.net/00_intro.html (accessed 27 February 2022).

Srinivasan, M. & Rabagliati, H. The implications of polysemy for theories of word learning. Child Dev. Perspect. 15 , 148–153 (2021).

Bizzi, E. Motor control revisited: a novel view. Curr. Trends Neurol. 10 , 75–80 (2016).

Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species–A Facsimile of the First Edition (Harvard Univ. Press, 1964).

Herculano-Houzel, S. The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its associated cost. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109 , 10661–10668 (2012).

White, L. T. The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science 155 , 1203–1207 (1967).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

King, M. C. & Wilson, A. C. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science 188 , 107–116 (1975).

Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature 437 , 69–87 (2005).

Buckner, R. L. & Krienen, F. M. The evolution of distributed association networks in the human brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 , 648–665 (2013). This review presents the evidence for the disproportionate expansion of the association cortex relative to other brain areas in humans .

Duncan, J., Assem, M. & Shashidhara, S. Integrated intelligence from distributed brain activity. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24 , 838–852 (2020).

Saxe, R. & Kanwisher, N. People thinking about thinking people: the role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. NeuroImage 19 , 1835–1842 (2003).

Buckner, R. L. & DiNicola, L. M. The brain’s default network: updated anatomy, physiology and evolving insights. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20 , 593–608 (2019).

Deen, B. & Freiwald, W. A. Parallel systems for social and spatial reasoning within the cortical apex. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.23.461550 (2021).

Mitchell, D. J. et al. A putative multiple-demand system in the macaque brain. J. Neurosci. 36 , 8574–8585 (2016).

Cantlon, J. & Piantadosi, S. Uniquely human intelligence arose from expanded information capacity. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 3 , 275–293 (2024).

Tomasello, M. The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition (Harvard Univ. Press, 2009).

Boyd, R., Richerson, P. J. & Henrich, J. The cultural niche: Why social learning is essential for human adaptation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 10918–10925 (2011).

Henrich, J. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter (Princeton Univ. Press, 2016).

Heyes, C. Cognitive Gadgets (Harvard Univ. Press, 2018).

Gumperz, J. J. & Levinson, S. C. (eds). Rethinking Linguistic Relativity (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996).

Piaget, J. Language and Thought of the Child: Selected Works , Vol. 5 (Routledge, 2005).

Gleitman, L. R. & Papafragou, A. in Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning (eds Holyoak, K. & Morrison, R.) 2nd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Fedorenko, E. & Varley, R. Language and thought are not the same thing: evidence from neuroimaging and neurological patients. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1369 , 132–153 (2016).

Gentner, D. Language as cognitive tool kit: How language supports relational thought. Am. Psychol. 71 , 650 (2016).

Frank, M. C., Everett, D. L., Fedorenko, E. & Gibson, E. Number as a cognitive technology: Evidence from Pirahã language and cognition. Cognition 108 , 819–824 (2008).

Wernicke, C. The aphasic symptom-complex: a psychological study on an anatomical basis. Arch. Neurol. 22 , 280–282 (1869).

Lichteim, L. On aphasia. Brain 7 , 433–484 (1885).

Poeppel, D., Emmorey, K., Hickok, G. & Pylkkänen, L. Towards a new neurobiology of language. J. Neurosci. 32 , 14125–14131 (2012).

Tremblay, P. & Dick, A. S. Broca and Wernicke are dead, or moving past the classic model of language neurobiology. Brain Lang. 162 , 60–71 (2016).

Hillis, A. E. et al. Re‐examining the brain regions crucial for orchestrating speech articulation. Brain 127 , 1479–1487 (2004).

Flinker, A. et al. Redefining the role of Broca’s area in speech. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 2871–2875 (2015).

Long, M. A. et al. Functional segregation of cortical regions underlying speech timing and articulation. Neuron 89 , 1187–1193 (2016).

Guenther, F. H. Neural Control of Speech (MIT Press, 2016).

Basilakos, A., Smith, K. G., Fillmore, P., Fridriksson, J. & Fedorenko, E. Functional characterization of the human speech articulation network. Cereb. Cortex 28 , 1816–1830 (2018).

Obleser, J., Zimmermann, J., Van Meter, J. & Rauschecker, J. P. Multiple stages of auditory speech perception reflected in event-related fMRI. Cereb. Cortex 17 , 2251–2257 (2007).

Mesgarani, N., Cheung, C., Johnson, K. & Chang, E. F. Phonetic feature encoding in human superior temporal gyrus. Science 343 , 1006–1010 (2014).

Norman-Haignere, S., Kanwisher, N. G. & McDermott, J. H. Distinct cortical pathways for music and speech revealed by hypothesis-free voxel decomposition. Neuron 88 , 1281–1296 (2015).

Overath, T., McDermott, J., Zarate, J. & Poeppel, D. The cortical analysis of speech-specific temporal structure revealed by responses to sound quilts. Nat. Neurosci. 18 , 903–911 (2015).

Norman-Haignere, S. V. et al. A neural population selective for song in human auditory cortex. Curr. Biol. 32 , 1470–1484.e12 (2022).

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 , 393–402 (2007).

Friederici, A. D. The cortical language circuit: from auditory perception to sentence comprehension. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 262–268 (2012).

Wilson, S. M. et al. Recovery from aphasia in the first year after stroke. Brain 146 , 1021–1039 (2023).

Radford, A. et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 1 , 9 (2019).

Jain, S. & Huth, A. Incorporating context into language encoding models for fMRI. in Proc. 32nd International Conf. Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Bengio, S. et al.) (Curran Associates, 2018).

Schrimpf, M. et al. The neural architecture of language: Integrative modeling converges on predictive processing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , e2105646118 (2021).

Caucheteux, C. & King, J. R. Brains and algorithms partially converge in natural language processing. Commun. Biol. 5 , 134 (2022).

Goldstein, A. et al. Shared computational principles for language processing in humans and deep language models. Nat. Neurosci. 25 , 369–380 (2022).

Tuckute, T., Kanwisher, N. & Fedorenko, E. Language in brains, minds, and machines. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-120623-101142 (2024).

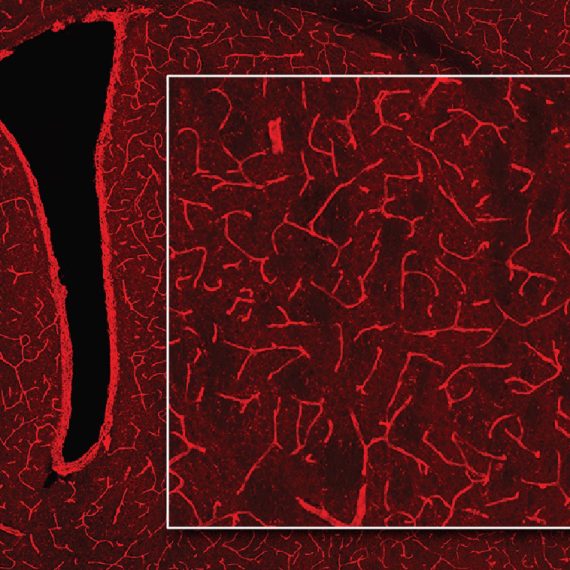

Paulk, A. C. et al. Large-scale neural recordings with single neuron resolution using Neuropixels probes in human cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 25 , 252–263 (2022).

Leonard, M. K. et al. Large-scale single-neuron speech sound encoding across the depth of human cortex. Nature 626 , 593–602 (2024).

Fodor, J. A. The Language of Thought (Crowell, 1975).

Fodor, J. A. & Pylyshyn, Z. W. Connectionism and cognitive architecture: a critical analysis. Cognition 28 , 3–71 (1988).

Rule, J. S., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Piantadosi, S. T. The child as hacker. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24 , 900–915 (2020).

Quilty-Dunn, J., Porot, N. & Mandelbaum, E. The best game in town: the reemergence of the language-of-thought hypothesis across the cognitive sciences. Behav. Brain Sci. 46 , e261 (2023).

Rumelhart, D. E., McClelland, J. L. & PDP Research Group. Parallel Distributed Processing, Vol. 1: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition: Foundations (MIT Press, 1986).

Smolensky, P. & Legendre, G. The Harmonic Mind: From Neural Computation to Optimality–Theoretic Grammar Vol. 1: Cognitive Architecture (MIT Press, 2006).

Frankland, S. M. & Greene, J. D. Concepts and compositionality: in search of the brain’s language of thought. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71 , 273–303 (2020).

Lake, B. M. & Baroni, M. Human-like systematic generalization through a meta-learning neural network. Nature 623 , 115–121 (2023).

Dehaene-Lambertz, G., Dehaene, S. & Hertz-Pannier, L. Functional neuroimaging of speech perception in infants. Science 298 , 2013–2015 (2002).

Pena, M. et al. Sounds and silence: an optical topography study of language recognition at birth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100 , 11702–11705 (2003).

Cristia, A., Minagawa, Y. & Dupoux, E. Responses to vocalizations and auditory controls in the human newborn brain. PLoS ONE 9 , e115162 (2014).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. Ivanova, R. Jackendoff, N. Kanwisher, K. Mahowald, R. Seyfarth, C. Shain and N. Zaslavsky for helpful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript; N. Caselli, M. Coppola, A. Hillis, L. Menn, R. Varley and S. Wilson for comments on specific sections; C. Casto, T. Regev, F. Mollica and R. Futrell for help with the figures; and S. Swords, N. Jhingan, H. S. Kim and A. Sathe for help with references. E.F. was supported by NIH awards DC016607 and DC016950 from NIDCD, NS121471 from NINDS, and from funds from MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Simons Center for the Social Brain, and Quest for Intelligence.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

Evelina Fedorenko & Edward A. F. Gibson

Speech and Hearing in Bioscience and Technology Program at Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA

Evelina Fedorenko

University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

Steven T. Piantadosi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to conceiving, writing and revising this piece.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Evelina Fedorenko .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.