Japanese History: Edo Period Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Bibliography

The Edo period also known as the Tokugawa period is the period between 1603-1868 in the Japanese history when Japan was under the Tokugawa Shogunate rule who had divided the country into 300 regions known as Daimyos. Tokugawa leyasu officially opened the era on March, 24, 1603 while Tokugawa yoshinobu resigned on May, 3 1868 after the Meiji restoration. The Tokugawa family ruled Japan from their base in Edo (currently Tokyo). The post of Emperor was more ceremonial during the Edo era (Patricia 60).

Tokugawa leyasu supported foreign trade but he was also suspicious of the influence of the outsiders during the pre-Edo period; Japan underwent the Nanban trade era during which the intense interaction with the European powers took place, namely, economic and religious. Trade restrictions, Christian missionary execution and Spanish expulsion were some of the restrictions that were enforced. The Closed Country Edict in 1635 was the climax of all the restrictions because of the following:

- Set highly strict regulations to minimize the movement of people into and out of the Japanese territory; death penalty was the consequence.

- Catholicism and all Christian practices were forbidden; Missionaries were also barred from entering Japan, and harsh sentences were drawn for those who entered.

- Trade restrictions were set; trade along ports was consequently limited. Portuguese relations with Japan were completely cut off (Alfred 138).

The Edo period was marked by the urban culture in Japan, for instance, Edo became the largest city on earth during those times with a population of 1.2 million residents as compared to the second largest place, London, with 800,000 residents. The period also experienced the rise of entertainment culture such as theaters or humorous novels.

Ordinary residents were also able to gain access to print media following the polychrome woodblocks development. People were also interested in learning more about Europe and all its sciences, commonly known as “Dutch learning” despite the minimal contact between Japan and the Western world (Alfred 100).

Arrival of Matthew Calbraith Perry and his four-ship fleet along the Edo Bay in July 1853 marked the end of the seclusion period in Japan. Japan finally accepted Perry’s demands to ending seclusion and opening up to foreign trade, consequently, the Treaty of Kanagawa that opened-up two ports (Hakodate and the port of Shimoda) to foreign American ships was signed (Administration, United States. National Archives and Records 1-4).

Five years after the Treaty of Kanagawa, the Harris treaty was signed between Japan and the US. The Kanagawa treaty became a catalyst factor of internal conflicts, which were only solved after the Tokugawa shogunate’s fall; similar agreements were negotiated by European powers such as Russia, the United Kingdom and France. (William 4)

After 250 years rule over Japan, the Tokugawa Shogunate turned the Japanese nation into a united cohesive nation with the mushrooming of many urban centers across Japan, for example, Edo became the largest and most populated city on earth with 1.2 million residents; Japan also experienced some artistic as well as intellectual development during this period.

On the other hand, the seclusion policy undermined all the good things that are associated with the rule; it is a policy that consistently haunted the Tokugawa rule, and finally led to its fall as the Japanese opted for a more open Meiji restoration that allowed all forms of Western culture to freely penetrate into Japan without necessarily having to restrict them.

Administration, United States. National Archives and Records. The Treaty of Kanagawa: Setting the Stage for Japanese-American Relations. New York City: National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. Print.

Alfred J. Andrea, and James H. Overfield. The Human Record, Volume II: Sources of Global History: Since 1500. London: Cengage Learning, 2011. Print.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Anne Walthall, and James Palais. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Tokyo: Cengage Learning, 2008. Print.

William C. Middlebrooks. Beyond Pacifism: Why Japan Must Become a Normal Nation: Why Japan Must Become a Normal Nation. New York City: ABC-CLIO, 2008. Print.

- Hiroshima: Rising from the Ashes of Nuclear Destruction

- Tokugawa Settlements and Rule of Meiji in Japan

- Kitagawa and Gainsborough Artworks

- World History: A Peace to End All Peace by David Fromkin

- The Adventures of Ibn Battuta

- The Effects of the Korea Division on South Korea After the Korean War

- The Tale of a Great Journey: "The Rihla" by Ibn Battuta

- The Boxer Rebellion

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 20). Japanese History: Edo Period. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/

"Japanese History: Edo Period." IvyPanda , 20 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Japanese History: Edo Period'. 20 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Japanese History: Edo Period." November 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

1. IvyPanda . "Japanese History: Edo Period." November 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

IvyPanda . "Japanese History: Edo Period." November 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

Site Content

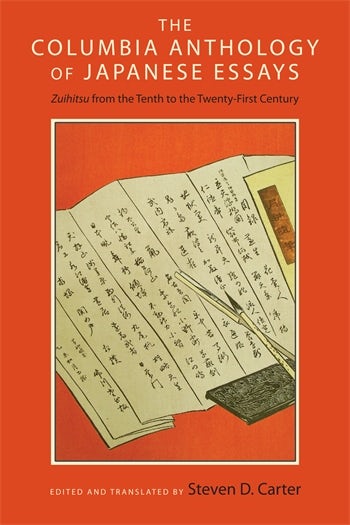

The columbia anthology of japanese essays.

Zuihitsu from the Tenth to the Twenty-First Century

Edited and translated by Steven D. Carter

Columbia University Press

Pub Date: October 2014

ISBN: 9780231167710

Format: Paperback

List Price: $45.00 £38.00

Shipping Options

Purchasing options are not available in this country.

ISBN: 9780231167703

Format: Hardcover

List Price: $135.00 £113.00

ISBN: 9780231537551

Format: E-book

List Price: $44.99 £38.00

- EPUB via the Columbia UP App

- PDF via the Columbia UP App

The focused ramble of the traditional Japanese essay format called zuihitsu (literally, 'following the brush') has appealed to writers of both genders, all ages, and every class in Japanese society. Highly personal, these essays contain dollops of philosophy, odd anecdotes, quiet reflection, and pronouncements on taste. In running alongside the main tracks of Japanese literature, this broad collection of zuihitsu brims with idiosyncratic interest. Liza Dalby, author of The Tale of Murasaki and East Wind Melts the Ice: A Memoir Through the Seasons

Savor a copy of The Columbia Anthology of Japanese Essays , and take a contemplative walk through the Japanese mind, full of poetic turns and pithy longings, ribald humor and lofty aspirations. Kris Kosaka, The Japan Times

Rich and highly enjoyable.... This evocative selection serves both as an excellent introduction to the genre for the English-speaking world and as a reminder that, no matter how distant or seemingly different the society, people's individual struggles, aspirations and aesthetics transcend their own times. Morgan Giles, Times Literary Supplement

Winner, 2016 2015-2016 Japan-United States Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature

About the Author

- Asian Fiction and Literature

- Asian Literature in Translation

- Asian Studies

- Asian Studies: Arts and Culture

- Asian Studies: Fiction and Literature

- Fiction and Literature

- Literary Studies

- Asian Studies: East Asian History

- History: East Asian History

- Environment

- Globalization

- Japanese Language

- Social Issues

After the Meiji Light: The Transition to Taisho, 1905-1912

Editor’s Note: It will be particularly helpful to have access to either Gordon, Andrew, A Modern History of Japan or McClain, James , Japan : A Modern History to conduct this lesson.

With the revision of the Unequal Treaties, acknowledgement by the West of Japan’s great power status, and its acquisition of a colonial empire, Japan’s wars against the Chinese and Russians seemed to represent the realization of the Meiji dream. Instead, Japan’s leaders recognized early just how fragile their new great power status was abroad and how precarious popular support for their government was at home.

- Students will compare and contrast the benefits and obstacles brought about in Japan by the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars;

- Students will understand the different reasons why the transition from the Meiji to the Taisho periods can be called a time of uncertainty about Japanese society, Japan's leadership, and Japan's place in the world; and

- Students will describe reasons for increased political consciousness and dissatisfaction with governmental policies and actions among the Japanese populace during this time period.

Common Core Standards College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading

- Standard 1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

- Standard 7. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and media, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Writing

- Standard 2. Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Speaking and Listenin g

- Standard 4. Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

- McRel Standard 4 . Gathers and uses information for research purposes .

- McRel Standard 5 . Uses the general skills and strategies of the reading process .

- McRel Standard 7 . Uses reading skills and strategies to understand and interpret a variety of informational texts .

- McRel Standard 8 . Uses listening and speaking strategies for different purposes .

World History

- McRel Standard 36 . Understands patterns of global change in the era of Western military and economic dominance from 1800 to 1914 .

- McRel Standard 37 . Understands major global trends from 1750 to 1914 .

- McRel Standard 38 . Understands reform, revolution, and social change in the world economy of the early 20th century .

- McRel Standard 39 . Understands the causes and global consequences of World War I .

The transition from Meiji to Taisho Japan was a period of reflection and uncertainty for the Japanese people and their political leaders.

In what ways did the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars impact Japanese society and Japan’s economy?

- What set of expectations arose among the Japanese populace during these wars and why was the Japanese government unable to live up to its own wartime propaganda?

- What changes to Japanese society led intellectuals to be both proud of its nation’s accomplishments, yet also to be extremely uncertain of the costs of progress during the transition from Meiji to Taisho?

Divide students into small groups and ask them to formulate a response to the following question: In contemporary American society, what recourse does the populace have to express grievances about governmental policies and actions?

- Geography Quiz : (3-5 minutes) Prepare either a list of ten place names and ask the students to locate them correctly on maps of Japan and East Asia, or one page of ten place names with blank spaces provided and two maps with the places marked on the maps. Include dots, arrows pointing to islands, and so forth and label A-J for a matching exercise.

- Lecture : Use an image of the Japanese people meeting in Hibiya Park on September 5, 1905, after the government made public the terms of the Treaty of Portsmouth, as a starting point for a discussion of the significance of the Hibiya Riots. (During the riots, around 30,000 protesters gathered to call for the government to renegotiate the treaty with Russia. As the crowd got out of hand and began to destroy government property, the police responded with force, leaving seventeen of the rioters dead.)

- Reading : The Hibiya Riots signified the growth of a mass political consciousness and the emergence of a nationalist chauvinism among the populace as well as marking the beginning of popular movements against the government. In short, the Japanese people had reached their limit of endurance and willingness to sacrifice for the government uncritically. The chapter entitled “New Awakenings, New Modernities” in James McClain’s Japan: A Modern History , is good background reading for this unit, while Andrew Gordon’s subsection “The Era of Popular Protest” (pages 131-35) from his A Modern History of Japan provides more specific information on the Hibiya Riots themselves.

- What main themes do you see running through Soseki’s take on modern life?

- Why would Soseki lament the isolation and alienation of the individual in urban Japanese society?

- Most Japanese peopledid not want to go back to life under Tokugawa rule, but what does Soseki tell us is being lost in Japan’s headlong rush to modernize?

- On the basis of these passages, how would you describe the way the protagonist (Joji) sees Naomi?

- What is Tanizaki implicitly criticizing in these passages?

- Do you see these passages as allegorical?

- After studying the biographies of General Nogi and the Taisho Emperor, what general sense of things to come do you think the Japanese people experienced with the end of the Meiji period in 1912?

- Do you think that they felt confident about the future of their nation? Why or why not?

- Critique: Using Soseki’s prose as a model, have each student write a short comment on a controversial issue in modern American popular thought, describing this issue’s positive and negative ramifications in contemporary culture.

- Japan's new international position;

- The weakening of the old Meiji leadership;

- The development of political parties;

- The women's movement;

- Economic and social modernization and the gap between rich and poor;

- The development of mass media; and

- The growing pace of public protest.

- Analysis - Essay and/or Discussion : Ask students to study the table in A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (page 132), and to describe the various opinions, trends and policies that they perceive in these events and their outcomes during the late Meiji and the Taisho periods.

Receive Website Updates

Please complete the following to receive notification when new materials are added to the website.

Late Heian Period (ca. 900-1185)

• Nara and Heian Japan (710 AD - 1185 AD) [About Japan: A Teacher's Resource] An overview of Japan's Nara and Heian periods. Discusses the Fujiwara family, their private estates, and the rise of the warrior.

• Heiji Monogatari Emaki (Tale of the Heiji Rebellion) Scrolls - "A Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace" [Princeton University] The Heiji disturbance, which occurred late in 1159, represents a brief armed skirmish in the capital. One faction, led by Fujiwara Nobuyori, in alliance with the warrior Minamoto Yoshitomo, staged a coup. In the scene depicted here, they surrounded the palace, captured the sovereign, placed him in a cart and then consigned the structure to the flames. Even though Nobuyori and Yoshitomo were triumphant here, they later suffered defeat and death at the hands of their rival Kiyomori...After the Heiji disturbance, Taira Kiyomori gained influence as a trusted advisor to the retired emperor, Go-Shirakawa. He launched his own coup some twenty years later, which unleashed a civil war, known commonly as the Genpei Wars (1180-85). One of Yoshitomo's sons, Minamoto Yoritomo, triumphed in this campaign, and consigned Taira Kiyomori's relatives to death or exile. Yoritomo established the Kamakura bakufu, which provided judicial and policing authority for its followers, known as housemen (gokenin) from 1185 until 1333. // The Heiji scrolls date from the thirteenth century and represent a masterpiece of "Yamato" style painting. They can be documented as being treasured artifacts in the fifteenth century, when nobles mention viewing them, but they now only survive in fragmentary form. The scene appearing here, entitled "A Night valuable depiction of Japanese armor as it was worn during the early Kamakura era (1185-1333). By contrast, most surviving picture scrolls showing warriors date from the fourteenth century and show later styles of armor...The scrolls read from right to left, and all action flows to the left. A few people hurrying flow into a confused throng of warriors and nobles, epitomized by a wayward bystander being crushed by an ox cart. Out of the confusion, attention shifts to the palace...Continued on site.

• The Legends of Hachiman [Smith College Museum of Art] From protector of the imperial house, to protector of the Minamoto military house, to protector of the nation, the legend of the Shinto deity, Hachiman, evolved throughout Japanese history... During the Heian period, Hachiman became the protector of the Minamoto military house when the clan adopted Hachiman as their clan deity ( ujigami ) ...Minamoto Yoritomo (1147-1199), who would defeat the Taira clan in the Gempei Wars (1180-1185), a victory that was attributed in no small part to Hachiman's divine protection. The appropriation of Hachiman by the Minamoto clan is seen in multiple instances in the Japanese war epic that describes the Gempei War, Tales of Heike . The site provides background on the scrolls, suggestions for viewing a handscroll, and questions for discussion .

Kamakura Period (1185-1333); Muromachi Period (1333-1568)

• The Age of the Samurai (1185-1868) [Asia for Educators] A guide to the samurai governments that ruled Japan from 1185 to 1868. With discussion questions.

• Kamakura and Nanbokcho Periods (1185-1392) [Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art] A short introduction, with images of seven artworks in the museum's collection.

• Muromachi Period (1392-1573) [Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art] A short introduction, with images of six artworks in the museum's collection.

• Japan's Medieval Age: The Kamakura & Muromachi Periods [About Japan: A Teacher's Resource] An in-depth look at political, economic, cultural, and religious life during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods.

Lesson Plan • A Case Study of Medieval Japan through Art: Samurai Life in Medieval Japan [Program for Teaching East Asia, Center for Asian Studies, University of Colorado] "The samurai warrior has come to symbolize Japan's medieval period of social and political unrest that lasted from the late twelfth to late sixteenth centuries. Working with artistic renderings of the samurai as well as cultural artifacts of samurai life, students recognize the complex, complementary aspects of the samurai culture that developed during this period. Students consider this more nuanced view of the samurai as they take on the role of advisors to a director hoping to make an authentic film about Medieval Japan." An in-depth introductory essay and lesson plan, with images, focusing on the Kamakura (1185-1333), the Muromachi (1336-1573), and the Momoyama (1573-1603) shogunates.

The Mongols' Failed Naval Campaigns Against Japan, 1274 and 1281

• "Relics of the Kamikaze" [Archaeology] An excellent article about the discovery and excavation of Khubilai Khan's 13th-century invasion fleet off the coast of Takashima. With a map and several images. From the January/February 2003 issue of Archaeology magazine.

• Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions (Annotated) [Princeton University] This site allows you to view individual scenes depicting the Mongol Invasions of Japan. Takezaki Suenaga, a warrior who fought against the Mongols in both 1274 and 1281, commissioned scrolls recounting his actions. This unique record of the invasions, and important eyewitness account, was heavily damaged in the ensuing centuries – according to lore they were even once dropped into the ocean! By the time of their rediscovery in the eighteenth century, the scenes and text of the scrolls were scattered into separate sheets. See also the partner site Mongol Invasions of Japan - 1274 and 1281 - this web site is devoted to understanding the Mongol Invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281. The failure of the invasions gave rise to the notion of the "divine wind" or Kamikaze, although an exploration of the invasions reveals that the Japanese defeated the Mongols with little need of divine, or meteorological intervention.

• Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan [PDF] [Association for Asian Studies] With images and maps, topics include: Kamikaze, the 'Divine Wind,' The Mongol Continental Vision Turns Maritime, Korea's Historic Place in Asian Geopolitics, Mongol Invasions of Japan, Reflections on the Mongol Maritime Experience.

• The Legends of Hachiman [Smith College Museum of Art] "This particular pair of lavishly ornamented handscrolls illustrates the legends of the Shinto deity Hachiman [whose 'popularity ... increased after the thirteenth century when Japan was attacked by Mongol forces in 1274 and 1281']. The paintings, which date to the mid-seventeenth century, are rendered in the yamato-e style favored by the members of the Tosa school to which they are attributed. Both the painting and the calligraphy exemplify the highly refined styles favored by the court at the start of the Edo period (1615-1868)." With background information on Shinto and Hachiman and viewing a handscroll.

Also see the Video Unit on Medieval Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods) for more about the Mongol invasions of Japan .

New Sects in Buddhism

Shinran, 1173-1263, founder of the Jodo Shinshu (The True Teaching of the Pure Land) Primary Source w/DBQs • Shinran's Lamentation and Self-Reflection [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

• Ox-Herding: Stages of Zen Practice [ExEAS, Columbia University] The ten ox-herding pictures and commentaries presented here depict the stages of practice leading to the enlightenment at which Zen (Chan) Buddhism aims. The story of the ox and oxherd is an old Taoist story, updated and modified by a twelfth-century Chinese Buddhist master to explain the path to enlightenment.

Dōgen Zenji, 1200-1253, founder of the Soto Zen sect Primary Source w/DBQs • Dōgen's How to Practice Buddhism (Bendōwa) [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Nichiren, 1222-1282, founder of the Nichiren sect Primary Source w/DBQs • Nichiren's Rectification for the Peace of the Nation (Risshō Ankoku Ron) [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Also see the Video Unit on Medieval Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods) for more about the Buddhist sects in medieval Japan .

Maintaining Order through Political Transition

Minamoto Yoritomo, 1147-1199, and the Kamakura Bakufu Primary Source w/DBQs • Selected Documents of the Kamakura Bakufu [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Ashikaga Takauji, 1305-1358 Primary Source w/DBQs • The Kemmu Shikimoku (Kemmu Code) [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Imagawa Sadayo (Imagawa Ryōshun), 1325-1420 Primary Source w/DBQs • Articles of Admonition by Imagawa Ryōshun to His Son Nakaaki [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Asakura Toshikage, 1428-14851 Primary Source w/DBQs • The Seventeen-Article Injunction of Asakura Toshikage [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

The Tale of the Heike

Primary Source • The Tale of the Heike [Asia for Educators] The Tale of the Heike recounts the struggle for power between the Taira (or Heike) and Minamoto (or Genji) houses in the late twelfth century. With the Taira's defeat in 1185 and the establishment of a new warrior government by the victorious Minamoto, the medieval age began. From this war tale, we can learn much about life in Japan during this transitional period and about warrior culture. With discussion questions.

Also see the "War Tales" section of the Video Unit on Medieval Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods) for more about the Tale of the Heike .

For The Pillow Book (ca. 1002) and The Tale of Genji (ca. 1021) please see the Literature section of Time Period 600-1000 CE . For The Tale of the Heike please see the Military and Defense section , above.

Kamo no Chōmei (ca. 1153-1216)

Primary Source • An Account of My Hut [Asia for Educators] Excerpts from this famous essay written in 1212, in which the author, Kamo no Chōmei describes his own road to becoming a Buddhist monk. With discussion questions.

Video Unit • An Account of My Hut [Asia for Educators] A video unit on the famous 13th-century essay introduced above. Featuring Columbia University professor Donald Keene and Asia Society President Emeritus Robert Oxnam.

Yoshida Kenkō (1283-1350)

Primary Source • Essays in Idleness [Asia for Educators] Short excerpts from Essays in Idleness . With a brief historical introduction and exercises for students.

Video Unit • Kenkō's Essays in Idleness and Japanese Aesthetics [Asia for Educators] This video unit on Yoshida Kenkō's 14th-century literary work discusses the Japanese aesthetic of simplicity and impermanence. Featuring Columbia University professor Donald Keene and Asia Society President Emeritus Robert Oxnam.

Noh and Kyōgen

• The Forms of Japanese Drama [Asia for Educators] A brief description of the four major dramatic forms that came out of Japan's medieval period: Noh, Kyôgen, Kabuki, and Bunraku. Followed by a classroom exercise for students.

• Noh Drama [Asia for Educators] This unit begins with a short introduction to Noh, the oldest surviving form of Japanese theater. Also includes a description of two recommended play ("Atsumori" and "Sotoba Komachi"), followed by classroom exercises for students.

• Noh Costume [The Metropolitan Museum of Art] An overview of the development of Noh costumes during the Muromachi and Momoyama periods. With ten examples from the museum's collection.

Video Unit • An Introduction to Noh [Asia for Educators] This video unit on Noh, a dramatic form that originated in Medieval Japan, discusses Noh's history and basic structure, Noh masks, the aesthetics of Noh, and Noh theater today. Featuring Columbia University professors Donald Keene and Haruo Shirane, and Asia Society President Emeritus Robert Oxnam.

• Kyōgen [Asia for Educators] A short introduction to Kyōgen, the comedic counterpart to Noh. Also includes a description of a recommended play ("Busu"), followed by classroom exercises for students.

• The Way of Tea [Five College Center for East Asian Studies] Tea Ceremony, or Chado (茶道), is one of the Japanese traditional arts involving ritualistic preparation of tea. Cha (茶) means tea, and do (道) means the way or the path. Thus, Chado is translated as the Way of Tea.… The Way of Tea is composed of a series of acts such as building a fire in the hearth, boiling the water, whisking the green tea powder in a tea bowl, and serving it along with some sweets. Simply put, it is an act in which the host invites the guest to share a bowl of tea together. Indeed, it began as a simple act of making and drinking tea. Over the centuries, however, it was influenced by Zen Buddhism philosophy and became a highly stylized form of art.

• Steeped in History: The Art of Tea [PDF] [UCLA Fowler Museum]

• Tea Traditions [TeachJapan] A portal for units on tea in Japan developed by Asia Art museums.

• What is Teachable about Japanese Tea Practice? [Education about Asia] Download PDF on page.

Note to Teachers • The journal Education about Asia has many excellent teaching resources on-line on all topics related to East, South and SE Asia.

Scroll Painting

• Emakimono [Asia Society] "During the 11th to 16th centuries, painted handscrolls, called emakimono, flourished as an art form in Japan, depicting battles, romance, religion, folktales, and even stories of the supernatural world." A short background essay with a suggested activity for students.

Lesson Plan • A Case Study of Heian Japan through Art: Japan's Four Great Emaki [Program for Teaching East Asia, Center for Asian Studies, University of Colorado] " Emakimono or emaki , narrative picture scrolls, developed into a distinctly Japanese art form in the Heian period, 794-1185 CE. In this lesson, students examine four emaki masterpieces to analyze the highly refined court culture, politics, and religion in the late Heian period. Working in groups, they then create preview posters for a museum exhibit featuring the four emaki , providing their interpretation of the facets of Heian culture they believe exhibit-goers should learn." Introductory essay and lesson plan with images of picture scrolls from the period.

• Takezaki Suenaga's Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan [Princeton] An excellent interactive website with several versions of the recovered 13th-century scrolls commissioned by the Kyushu warrior Takezaki Suenaga, who fought against the Mongols during the invasions of 1274 and 1281. Viewers can compare the "original" (reassembled) 13th-century version to 18th- and 19th-century copies and also see a 21st-century reconstruction of the 13th-century version. Also features an illustrated glossary.

• The Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki [Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art] A multimedia learning website about a 13th-century Japanese handscroll that illustrates the legends of the Kitano Shrine (Kitano Tenjin Engi). Included are a short introduction to the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki and images of the scroll.

Find more art-related resources for Japan, 1000-1450 CE at OMuRAA (Online Museum Resources on Asian Art)

Related Timelines from Other Websites

World History for Us All Big Era 5: 300 - 1500 CE

The Metropolitan Museum of Art World Regions: 1000 - 1400 AD World Regions: 1400 - 1600 AD

Hyperhistory.com 1000 - 1500

| Index of Topics for All Time Periods |

Skip to Content

Other ways to search:

- Events Calendar

- Voices of Modern Japanese Literature

Lesson (pdf) Handout 1 Handout 1 Key Handout 2 Handout 2 Key Handout 3 Handout 3 Key Handout 4 Handout 5 Handout 6 Handout 6 Key Handout 7 Handout 7 Key Handout 8 Handout 8 Key

Sarah Campbell, Ketchikan High School, Ketchikan, AK

Introduction

Modern writers like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and John Steinbeck are well known in American literary circles. These writers are often included in high school English and social studies curricula because of their artistic commentary on the way in which people viewed themselves and the world during the American modern period (1915-1945). Through these authors’ voices, readers are able, for example, to consider how World War I challenged American optimism, explore how the Great Depression left many with a feeling of uncertainty, and contemplate how World War II furthered feelings of disjointedness and disillusionment in 20th-century life. Through their varied approaches, techniques, and styles, modern American writers echoed the strong sense of isolation, alienation, and uncertainty felt by many Americans of the modern period.

The modernist movement was not exclusive to the United States; this literary movement extended around the world, including Japan. “ Modanizumu , as the term “modernism” was rendered into Japanese in the late 1920s, was a powerful intellectual idea, mode of artistic expression, and source of popular fashion in Japan from approximately 1910-1940,” explains William J. Tyler (2009) in his book Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913-1938 . Similar to American writers, Japanese writers and artists of the Modern period also broke from the authority and traditions of the past by attempting new styles, subjects, and themes. Rapid industrialization, women’s and men’s suffrage movements, education reforms, Taishō democracy, and nationalism provided rich topics for late Meiji and Taishō writers. Japanese Modern writers artistically commented upon the lifestyle, political, and socioeconomic changes of the early 20th century. Thus, their works provide rich sources for American high school curricula on Asian and world history and literature.

The Modern period in Japan overlaps the reigns of three Emperors: Meiji (1868-1912), Taishō (1912-1926), and early Shōwa (1926-1945). Throughout this lesson, “Modern Japan,” “Japan’s Modern Period,” and “Modern Literature” refer to this period of rapid modernization from the late 1800s through the late 1920s.

In this lesson, students read Meiji-Taishō literary works in their historical, cultural, biographical, and literary contexts, considering how individuals reacted to the process of modernization in Japan during the 20th century. During the lesson’s first day, students identify some basic characteristics of modernization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Japan, based on prior study and reading. Then, they make observations and inferences about this period, drawing on visual images from the late 1800s to the early 20th century, as well as Kambara Ariake’s poem “The Oyster Shell.” Through discussion, they define the characteristics of modern Japanese literature and the proletarian movement of the early 20th century in Japanese literature.

On Day 2, the class reads and discusses Mori Ogai’s “The Dancing Girl” (1890). They use the “Shared Inquiry” discussion format to explore the purpose and message of Ogai’s work and complete a reflective writing assignment considering what the short story reflects about modernization at the turn of the 20th century in Japan. On Days 3 and 4, students read Shimizu Shikin’s “The Broken Ring” (1891) and Kuroshima Denji’s “The Telegram” (1923), engaging in discussion and reflective writing using the strategies employed on Day 2.

Grade Level/Subject Area: Secondary/Asian Literature, World Literature, World History

Time Required: 4-5 class periods plus optional homework

For Students:

- Meiji-Taishō Background Essay ; this essay can be copied or students can access it online.

- Handout 1: Background Essay Reading Guide

- Handout 2: Visual Analysis Worksheet (you will need four copies for each student or student pair unless you plan to have students record their answers on separate sheets of paper)

- Handout 3: The Oyster Shell

- Handout 4: Characteristics of Modern Japanese Literature

- Handout 5: Reading for Tone and Mood

- Handout 6: Post-Reading Worksheet for “The Dancing Girl”

- Handout 7: Post-Reading Worksheet for “The Broken Ring”

- Handout 8: Post-Reading Worksheet for “The Telegram

For Teachers:

Computer and projector for showing the following images to students for analysis:

- September 1931 NAPF (Nippona Artista Proleta Federacio) and October 1931 NAPF (Nippona Artista Proleta Federacio) magazine covers

- Tokyo Construction Fair 1935

- Women in the 1920s: Woman Curling Hair and Ainu Woman Carrying Wood

- Handouts 1-3 and 6-8 Answer Keys

- Mori Ogai. “The Dancing Girl.” Youth and Other Stories . Ed. & trans. J. Thomas Rimer. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994. 6-24. Downloadable full text.

- Shimizu Shikin. “The Broken Ring.” Trans. Rebecca Jennison. The Modern Murasaki: Writing by Women of Meiji Japan . Eds. Rebecca L. Copeland and Melek Ortabasi. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006. 232-239.

- Kuroshima Denji. “The Telegram.” A Flock of Swirling Crows and Other Proletarian Writings. Trans. Zeljko Cipris. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005. 17-24.

At the conclusion of this lesson, students will be better able to:

- Identify and discuss characteristics of modern Japanese literature, drawing from selected examples of Meiji and Taishō era poetry and short stories.

- Identify and compare multiple perspectives on modernization as reflected in modern literature of the Meiji-Taishō literature.

Essential Questions

- In what ways did the events of modern Japan influence writers of that period?

- What perspectives on modernization are reflected in literature produced during the Meiji and Taishō periods?

Teacher Background

For an overview of the Meiji-Taishō period, please see the Meiji-Taishō Background Essay for this curriculum project by Ethan Segal, Michigan State University.

A note on name order and special naming of Japanese authors :

In Japanese, the family name comes first and given name last. In the short biographies below, family names appear first and in capital letters. However, when referring to Japanese authors and poets, the Japanese follow special rules based on the writer’s time period, his or her use of a pen name, or genre of literature. So, for the four writers below, the Japanese often refer to Mori Ogai, Kambara Ariake, and Shimizu Shikin by just their given names or pen names. Kuroshima Denji, as a proletarian writer, is referred to by his family name, Kuroshima. This lesson follows the Japanese convention for these writers.

KAMBARA Ariake (1876-1952)

Kambara Ariake is actually a pen name for a writer known for his poetry, biographical novel, and narratives. Ariake, as the poet is known, was born into an elite family, well-educated and well-travelled. His poetry earned him early success. In writing sonnets, a form rarely used at the time in Japan, he acquired a reputation as a symbolist poet. Failing to respond to new trends (e.g., embracing free verse) marked the end of Ariake’s writing career in 1947.

MORI Ogai (1862-1922)

Mori Ogai had a rich career beginning as a Japanese army surgeon, then as a translator, and later as a novelist and poet. He was born into an elite Japanese family and was therefore afforded a strong education. He was well trained in Confucian classics, Chinese poetry, Western thought and medicine, and the German and Dutch languages. While in the army, he spent time living in Germany, where he developed an interest in European literature. His writings can be divided into four phases. First, Mori translated European poetry and plays into Japanese; next, he spent a period writing about his personal experiences. Later in life, from 1912-1916, he wrote historical stories. His final writing period, from 1916 until his death, was characterized by biographies of late Edo period doctors. Mori is considered one of the great writers of modern Japan.

SHIMIZU Shikin (1868-1933)

Raised in Kyoto, Shimizu Shikin was highly educated. She was active in the women’s rights movement in Japan and frequently published in magazines. Scholars credit Shimizu Shikin as one of the first writers to adopt a new narrative style of Japanese writing in the early 20th century—the I Novel, a confessional genre in which the literary events reflect the writer’s life, all written from a first-person point of view. This writing style was popularized by Natsume Sōseki. A pioneering woman in many respects, Shikin married for love. She travelled with her husband to Europe, later ending her writing career to be a wife and mother.

KUROSHIMA Denji (1898-1943)

Kuroshima Denji was born into a poor farming family on Shodo Island in the Inland Sea. He later headed to Tokyo to work and study. In 1919 he was conscripted into the Japanese army and sent to fight in an Allied forces anti-revolutionary war against the new Soviet Union. His military service and war experiences were to influence much of Kuroshima’s writing. After the war, Kuroshima began writing and joined the emerging proletarian literature movement. This early 20th-century movement, in Japan and internationally, produced literature that focused on the harsh lives of peasants, workers, and other groups adversely affected by modernization or political repression and called attention to the need for social, economic, and political change. Kuroshima’s writing included stories of the experiences of Japanese soldiers who had served in the anti-Soviet war in Siberia as well as stories that focused on the struggles of Japanese peasants and workers. His collected works are a major contribution to the Japanese and international proletarian literature movement.

Preparing to Teach the Lesson

- This lesson uses several pedagogical techniques. Day 1 uses visual literacy questioning techniques to guide students in thoughtful and thorough analysis of visual source materials. Days 2 through 5 employ “ Great Books’ Shared Inquiry ” methods for analyzing and discussing print sources. If you are not familiar with these techniques, you may wish to learn more by exploring the above links, which are also listed in the References section at the end of the lesson.

- Prior to the lesson, review the Teacher Background , the Historical Background Essay by Ethan Segal, the images to be examined on Day 1, student materials, and answer keys. Preparation time will vary according to teacher familiarity with the characteristics of Modern Literature and with the Meiji and Taishō periods in Japanese history.

- Obtain master copies of and read in advance the three short stories used in the lesson.

- Duplicate copies of visuals, stories, and handouts for student use.

Lesson Plan: Step-by-Step Procedure

Prior to beginning the lesson.

This lesson assumes students have studied modernization in Meiji and 20th-century Japan. If not, assign the Historical Background Essay and Handout 1, Background Essay Reading Guide , provided with this lesson, or assign students the appropriate chapter in their history text.

- Japan’s rapid modernization when faced with challenges from Western countries after Commodore Perry “opened” Japan to Western trade in the 1850s.

- The Meiji (1868-1911) government’s goals of industrializing and modernizing Japan.

- Rapid industrialization, the growth of critical industries upon which Japan’s modern economy was built.

- Ask students how these changes compare to changes in U.S. society around the same period. What do they know about the positive and negative aspects of the many changes that came with modernization in societies in the early 20th century?

- Next, introduce students to the Essential Questions provided at the beginning of this lesson plan. In what ways did the rapid modernization that characterized Japan of the 1880s-1920s influence writers of that period? What perspectives on modernization are reflected in literature produced during the Meiji and Taishō periods? Explain to students that they will be exploring the link between modernization and literature as reflected in the “Modern Literature” movement of this period in Japan.

- Distribute Handout 2, Visual Analysis Worksheet , to individual students or pairs; you will need four copies per student or pair or may direct students to write their answers on separate sheets of paper. Explain that the class is going to explore some images of early 20th-century Japanese society to form impressions of life and modernization in Japan at that time. Go over the Visual Analysis Worksheet so students understand the analysis process for each image they see.

- The first image is a photograph taken in Tokyo in 1934.

- September 1931 NAPF (Nippona Artista Proleta Federacio) magazine cover

- October 1931 NAPF (Nippona Artista Proleta Federacio) magazine cover

- Women in the 1920s: Japanese women curling hair and Japanese women carrying wood

- Who was this image intended for? What do you see that makes you think this?

- Why do you think the artist or photographer chose to capture this event?

- What is the tone of the photo or illustration? That is, what is the artist or photographer’s attitude about the subject? On what visual clues do you base your answer?

- What is the mood of the photo or illustration? That is, what atmosphere does the image create for the viewer? What do you see that makes you know this?

- Taken together, how did the images you viewed help you understand Japan during this period?

- Next, distribute Handout 3 , “The Oyster Shell.” Read the excerpt from Kambara Ariake’s poem aloud to the students. Then ask students to read the poem again silently—this time using active reading strategies (line-by-line analysis of diction, images, symbols, form, and syntax).

- Lead students in a discussion of the poem using the questions on Handout 3 . An Answer Key with additional background for teachers is provided.

- To conclude Day 1, re-visit the images students viewed earlier in the class. Ask students to articulate characteristics the visuals of Modern Japan and Kambara’s poem share. Write these on the board.

- Distribute Handout 4 , Characteristics of Modern Japanese Literature. Review the handout. If time allows, conduct a class discussion comparing the list of characteristics students generated in Step 8 with the list on the handout. Otherwise, assign students to compare the two lists for homework.

- Tell students that today they will be reading a story titled “The Dancing Girl.” Published in 1890, “The Dancing Girl” came out at a time when Japan had been undergoing rapid industrialization, modernization, and social change for several decades during the late 1800s, the late Meiji period.

- Alert students to the Japanese convention of author names as outlined in the Teacher Background . In Japan, family name comes first, and given name last. However, in Japanese literature, well-established writers are known by their given names. So, in the case of Mori Ogai, whose story the class will read today, the author’s family name in Mori, and his given name is Ogai, but he is referred to as Ogai. Remind students of this convention as they move on to other stories in this unit.

- Remind students of the two Essential Questions for this lesson: In what ways did the events of modern Japan influence writers of that period? What perspectives on modernization are reflected in literature produced during the Meiji and Taishō periods? Ask students to keep these questions in mind as they read and discuss this story.

- How do you or those you know deal with adversity? Do you agree/disagree with these reactions? Why or why not?

- If you know something that might make a person unhappy, should you tell them anyway

- Should we only tell happy stories? Why or why not?

- Read Ogai’s “Dancing Girl” aloud to students or have students read independently. When the reading is complete, distribute Handout 5 , Reading for Tone and Mood; review the handout with students and ask them to complete the chart as they actively reread the story.

- At the end of the story, we are told that “friends like Aizawa Kenkichi are rare indeed, and yet to this very day there remains a part of me that curses him” (24). What did the narrator mean by this?

- Why were his countrymen so critical of his decision? If Elise’s madness had not removed the choice, how do you think the narrator would have resolved his dilemma?

- Who/what might Elise symbolize?

- Do you find the narrator’s confusion to be sincere? Why or why not?

- To conclude Day 2, have students complete Handout 6 , Post-Reading Worksheet for “The Broken Ring.” An Answer Key is provided.

- Imagine that you are one of the characters from “The Dancing Girl.” What would your feelings be after the incident? Compose a letter adopting the persona of one of the main characters and expressing your reactions to the incident.

- Ask student volunteers to restate the Essential Questions for this lesson. Ask additional volunteers to review how the first story the class read, “The Dancing Girl,” addressed these essential questions.

- Set the stage for today’s story—“The Broken Ring,” by Shimizu Shikin—by alerting students that this story, written about the same time (late Meiji, 1891) as “The Dancing Girl,” explores another dimension of the changes of modernization, focusing on relationships, marriage, and expectations in modern society.

- If you know something that might make a person unhappy, should you tell them anyway?

- Read “The Broken Ring” aloud to students or have students read independently.

- Ask students to actively reread the story. As students read the text for the second time, ask them to mark their copy of the text as follows: Mark places in the story “ ” when the main character is happy. Mark places in the story “ ” when the main character is unhappy.

- What does the story seem to reveal about female identity and female duty?

- At the end of the story, we are told that “my only remaining hope is that this broken ring may somehow be restored to its perfect form by the hand that gave it to me. But I know, of course, that such a thing is not yet…”(239). What did the narrator mean by this? Why end the statement with an ellipsis? What is the effect of this punctuation?

- The narrator reported that her father “has now come to have great sympathy for my long years of suffering” (239). How might the father’s change of heart serve as a symbol? What might this reveal about social attitudes in Japan at the turn of the 20th century?

- What do you think this story says about women in modern Japan at the turn of the century?

- The narrator asked, “Ah, will it take a hundred years before even a few will come to understand the precious value of this ring?” ( 232). Do you find the narrator’s confusion to be sincere? Why or why not? What do you think she hoped people would realize?

- Why did the narrator never tell us her name? What was achieved in her anonymity?

- To conclude Day 3, have students complete Handout 7 , Post-Reading Worksheet for “The Broken Ring.” An Answer Key is provided.

- As an optional extension, assign the following personal reflection writing assignment: Imagine that you are one of the characters from “The Broken Ring.” What would your feelings be after the incident? Compose a letter adopting the persona of one of these main characters and expressing your reactions to the incident.

- Ask students to volunteer ways in which the second story, “The Broken Ring,” addressed the Essential Questions.

- Explain to students that the final example of Modernist literature from Japan was written somewhat later than the first two stories, in the early 1920s. By this time, Japan had experienced over four decades of rapid change and modernization and was a fully industrialized society very much like England or the United States, and with many of the same social issues. The story focuses on another dimension of this rapid change—poor rural Japanese who experienced the changes of modernization in a different way than the middle class people of the previous stories. Thus, this story, “The Telegram,” presents yet another dimension of modernization.

- Provide students with a brief definition of proletarian literature of this time period, drawing from the paragraph about Kuroshima Denji in the Teacher Background . Ask what differences or new dimensions students might expect to see reflected in this story representing proletarian literature.

- Read “The Telegram” aloud in class or have students complete the reading independently.

- Why didn’t Gensaku allow his son to return to school? What statements or descriptions did you expect to hear but didn’t? How do you account for these omissions?

- What surprised you about the Kuroshimas’ story?

- How did the son react to his father’s decision? Why do you think he reacted the way he did?

- How did the choice of words affect you?

- How did the son live his life after his father’s decision? How do you think he felt about this?

- Why do you think the author told this story?

- Refer to Handout 4 and our discussion of the characteristics of modern Japanese literature from yesterday. What characteristics of modern Japanese literature are reflected in this story?

- What perspectives on modernization does this story illuminate?

- How do you or those you know deal with adversity? Do you agree/disagree with these reactions? Why or why not

- To conclude the day, have students complete Handout 8 , the Post-Reading Worksheet for “The Telegram.”

- As an optional extension, assign the following personal reflection writing assignment: Imagine that you are one of the characters from “The Telegram.” What would your feelings be after the incident? Compose a letter adopting the persona of one of these main characters and expressing your reactions to the incident.

As an optional assessment, students may be assigned the following essay:

How do you or those you know deal with adversity? How did Japanese people react to the challenges in their lives as a result of the demands of modernization? Do you agree/disagree with these reactions and/or the method in which they voiced their sentiments? Why or why not? Write a five-paragraph essay in which you articulate your understanding of the social landscape in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries, Japan’s Modern Period in literature.

Standards Alignment

Common core :.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.6: Analyze a case in which grasping a point of view requires distinguishing what is directly stated in a text from what is really meant.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.1: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.7: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words in order to address or solve a problem.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.7: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question) or solve a problem; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

Great Books Foundation .

Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Tyler, William J. Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913-1938. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Baker, Frank W. “Visual Literacy.” Media Literacy in the K-12 Classroom. International Society for Technology in Education.

Additional Resources

Japanese authors and literature of the modern period.

“A Short History of Japanese Literature: Part 5” and “Part 6.” Japan Kaleidoskop. July 5, 2013.

Meiji-Taishō History

Christensen, Maria. “The Meiji Era and the Modernization of Japan.” The Samurai Archives Japanese History Page. Cunningham, Mark E., and Lawrence J. Zwier. The End of the Shoguns and the Birth of Modern Japan. Pivotal Moments in History series . Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books, 2009.

Created 2015 Program for Teaching East Asia

Becoming Modern

- Meiji and Taishō Japan: An Introductory Essay

- Voices from the Past: The Human Cost of Japan’s Modernization, 1880s-1930s

- The Nature of Sovereignty in Japan, 1870s-1920s

- A Window into Modern Japan: Using Sugoroku Games

- Moga , Factory Girls, Mothers, and Wives

- Inventing Modern Japanese Man

- Negotiating Relationships: United States and Japan, 1905-1933

Terms of Use: Permission is given to reproduce this module for classroom use only. Other reproduction is prohibited without written permission from the Program for Teaching East Asia.

「『The Art Of、 Japanese Punctuation〜。』」!? What Periods, Commas, Quotation Marks and Brackets Look Like in Japanese

March 21, 2016 • words written by Koichi and Kristen Dexter • Art by Aya Francisco

When you're sitting there writing something, you may take the little things for granted… little things like periods , commas , and quotation marks . That's cool— they only bind together everything a sentence holds dear . If you didn't have these little things, this "punctuation" if you will, the fabric of sentence time would tear apart, creating some kind of super-black hole. (Ironically, it would just look like a period.)

And, wouldn't you know it, punctuation exists in Japanese as well! It's not that much different from English punctuation, but there are definitely a few things to keep in mind if you want to read Japanese more easily or one day get into Japanese translation . In this article, I'm going to cover pretty much all the Japanese punctuation you'll run into. In order to learn it, it'll only take a quick read. Feel free to use this article as reference!

Let's get started with some backstory.

Japanese Punctuation Before the West

This may be shocking, but before the Meiji era there was no punctuation in Japanese. Their version of the modern-day period ( 。) was introduced from China centuries earlier. But of course, it was ignored. When it was used, it was put just about anywhere to mean just about anything.

Thanks to Emperor Meiji's love for Western literature, punctuation like the period and comma ( 、) eventually made its way into written Japanese. In 1946, some years after the Meiji Restoration, the Ministry of Education passed a bill, letting people know how they were supposed to use them. Luckily for us English speakers, this means that a lot of Japanese punctuation symbols are nice and familiar! Unless of course you're trying to read anything pre-WWII, in which case the punctuation is weird and/or nonexistent.

Full-Width Spacing

One thing that really stands out to me in Japanese writing is the spacing. While it differs between operating systems, handwriting style, and your Japanese IME, Japanese typography tends to be something known as "full-width." English, on the other hand, is "half-width." Can you see the difference?

- nandedarou?

While you can type in half-width spaces in Japanese, it looks crowded compared to text you'll see everywhere else. The Japanese language was made to be nice and spread out. And that carries over to their punctuation, as well. There are technically no spaces between letters or words in Japanese. The only place you will find "extra" space is after punctuation, where they are automatically included. This saves anyone typing in Japanese from having to hit the space bar unnecessarily, especially since it's done so infrequently otherwise.

To sum things up, you don't usually have to worry about adding spaces between sentences. Punctuation has you covered. For example:

皆さんこんにちは、トウフグのコウイチでございます。ハロー!

Find the comma and the period. There's a little half-width (normal width in English) space after them, even though I didn't add them in. All I did was type the comma and period themselves— it all counts as one "letter", even when you try to highlight it (go ahead, try and highlight the above sentence).

Now that you know all about empty space in Japanese writing, what about learning all the (main) Japanese punctuation available to you? Let's do it!

Japanese Punctuation Marks

Because Japanese punctuation is so similar to English punctuation, there is a lot of overlap. As I mentioned earlier, however, there also tend to be a lot of subtle differences, which I'll go over below.

- 。 句点 (くてん) or 丸 (まる)

The Japanese period is used much the same as the English period. It marks a full-stop, or end to a sentence. In vertical writing, it sits at the bottom right, below the character before it. If the sentence is on its own or has quotes, however, the Japanese period is omitted most of the time. Japanese periods look like this:

The period itself is a small circle, and not a dot. This character is used the majority of the time in written Japanese, though, occasionally, you will see Western-style periods when a sentence ends with an English word.

- 、 読点 (とうてん) or 点 (てん)

The Japanese comma, like the Japanese period, is used in much the same way as the English one. It's put in the same place as the period (bottom right after the word) in vertical writing, as well.

Comma usage in Japanese is incredibly liberal compared to English. You can stick it pretty much wherever you want a break or pause in your sentence. Just don't abuse the power, please, it, is, irritating.

- 「」 鈎括弧 (かぎかっこ)

- 「」 Single Quotation Marks

Instead of things that look like "this" for quotation marks, which would get confusing because of dakuten (more on that later), the Japanese use little half-brackets to indicate quotes. Although these are called "single quotation marks" or "single quotes", which might make you think of 'this', they are the most common style of quote to use in Japanese. Almost any time you need to use a marker for quotes, you'll use single quotes.

- 『』 二重鉤括弧 (にじゅうかぎかっこ) or 白括弧 (しろかっこ)

- 『』 Double Quotation Marks

Double quotes are a lot less common than single quotes, but they have one good purpose. You know when you have to quote something that's quoting something else? In English, that usually looks like this: "The dog said 'woof' and ran away."

In Japanese punctuation, double quotes go inside single quotes when you're quoting text within text. It's the same rules as in British English punctuation (single first, double second).

Sometimes people will use these double quotes alone as if they are single quotes, but that's a stylistic choice on their part.

- 〜 波線 (なみせん) or 波ダッシュ (なみだっしゅ)

- 〜 Wave Dash

The wave dash isn't really similar to the Western (straight) dash in use. But it's likely the wave dash became popular because straight-line-dashes are already used in katakana to show a long vowel, and not differentiating it here would be confusing.

There are some uses that are like the Western dash, like showing a range of something (4〜5, 9時〜10時, etc), but there are some Japanese-only uses of this punctuation, including drawing out and changing the pitch of a vowel sound (そうだね〜), showing where something is from (アメリカ〜), and marking subtitles (〜こんにちは〜).

- ・ 中黒 (なかぐろ) or 中点 (なかてん) or 中ポツ (なかぽつ) or 黒丸 (くろまる)

- ・ Interpunct

The interpunct is a dot that aligns with the vertical or horizontal center (depending on writing direction) with the words next to it. It's typically used to break up words that go together. You see this most often when you have multiple words written in katakana, like foreign names.

It can be used with Japanese words, as well, though the use is more specialized in those cases. Some Japanese words, when placed side by side, can be ambiguous because combinations of kanji can mean different things. And if you have too many kanji next to each other it can get confusing.

Finally, the interpunct is used to break up lists, act as decimal points when writing numbers in kanji (why would you do that, please don't do that), and separate anything else that needs clarification. For example:

- ? クエスチョンマーク or はてなマーク or 疑問符 (ぎもんふ) or 耳垂れ (みみだれ)

- ? Question Mark

You'd think the Japanese question mark would be self explanatory, but there's a thing or two you ought to know about it. Just like its Western-style counterpart it indicates a question— that's simple enough. Thing is, though that Japanese already has a grammar-based marker (か) to show that you're making an inquiry, rendering any further punctuation redundant most of the time. As such, you won't see question marks in formal writing. Casual writing is a different story, because 1) casual writing has different rules in most languages and 2) Japanese speakers will often drop か in conversation in exchange for a questioning tone of voice, which is hard to convey without a question mark.

- ! 感嘆符 (かんたんふ) or ビックリマーク or 雨垂れ (あまだれ) or エクスクラメーションマーク

- ! Exclamation Point

The Japanese exclamation mark is used just like the Western one. It shows volume or emotion or both. You won't see exclamation marks in formal Japanese, though it's really common everywhere else, especially on Twitter, email, and text.

- () 丸括弧 (まるかっこ)

- () Parentheses

These look like English parentheses, but they have the extra spaces I mentioned when I covered full-width spacing. They're often used to show the kana readings of kanji words— for example:

They're also used an awful lot online in Japanese dictionaries and other educational resources ( like dusty paper books ). And, of course, they're used for annotations (like this) within a sentence.

- 【】 隅付き括弧 (すみつきかっこ) or 太亀甲 (ふときっこう) or 黒亀甲 (くろきっこう) or 墨付き括弧 (すみつきかっこ)

- 【】 Thick Brackets

Finally! Some Japanese punctuation we don't have in English! Sure, we have [] brackets, called 角括弧 ( かくかっこ ) in Japanese, but look at these dark ones! Brackets like this don't have a singular use, and they can really be used for anything; showing emphasis, listing items, or just making your brackets stand out more.

- {} 波括弧 (なみかっこ)

- {} Brackets

Just like the thick brackets, there is no specific use for these curly braces either. Often, though, you'll see them in inside normal brackets[{}]and in mathematical equations, too. I could have added about ten other bracket variations to this list. Seriously, there are way too many bracket types in Japanese.

- … 三点リーダー (さんてんりーだー)

Unlike the English ellipsis, the Japanese version typically hovers around the vertical middle of the line, instead of sitting at the bottom (though they can be formatted that way, as well). There can be as few as two ‥ or as many as six or more …… . They can symbolize the passing of time, silence, or a pause. They also convey silent emotion, which you'll recognize if you read a lot of anime and manga. Finally, you may also see them in text to symbolize long vowels or an omission or missing content.

Japanese Phonetic Marks

These aren't technically punctuation, but they're important symbols you'll see in Japanese and you should know what they mean, too.

- ゛ 濁点 (だくてん) or 点々 (てんてん)

- ゛ Dakuten or Tenten

These are the little marks you see next certain kana to make them "voiced." What that means, basically, is that your vocal cords vibrate when you say a them. They look like English quotations marks, which is probably why the Japanese version was created and is used way more often. They look like this when they're attached to kana:

And, just like the extra space that's added automatically between characters when you type in Japanese, you don't have to add these dakuten manually. Thanks to romaji you just type things how they sound— for example, "ga" for が— and the correct dakuten are added to the hiragana or katakana without any extra effort on your part. Thanks, technology!

- ゜ 半濁音 (はんだくおん) or 丸 (まる)

- ゜ Handakuten or Maru

The handakuten is similar to dakuten, but this little open circle means that the consonant it's attached to is "half" voiced. There are only a few of these in Japanese and they all make the "p" sound.

- っ 促音 (そくおん) or つまる音 (つまるおと)

- っ Small Tsu or Double Consonant

If you see this smaller version of the hiragana つ, it is not pronounced "tsu" (ever!). If you see it in the middle of a word, before a consonant, it means that the consonant after it is a "double" consonant. If you see it at the end of a word (before the particle と in many onomatopoeia) then it's a glottal stop. That means it's kind of like a constricted sound in your throat (that's your glottis in there, thus the name). The katakana version looks like this ッ.

- ー 長音符 (ちょうおんぷ) or 音引き (おんびき) or 棒引き (ぼうびき) or 伸ばし棒 (のばしぼう)

- ー Long Vowel Mark

Long vowel marks mark long vowels. So, instead of スウパア, you'd write スーパー. Simple right?

You'll mostly see these in katakana, hardly ever in hiragana. The only time you'll see them with hiragana is at the end of a sentence or after a drawn out particle or interjection. When it's used like that, it's interchangeable with 〜.

Bonus Symbols

While we're at it, let's look at some other symbols you're bound to see in Japanese.

- 々 踊り字 (おどりじ) or 躍り字 (おどりじ)

- 々 Iteration Mark

This neat-looking kanji is something called an iteration mark. That's a fancy way of saying it is a "repeater", i.e. any kanji it follows is repeated. You've probably seen it in words like 人々 ( ひとびと ) (people), 時々 ( ときどき ) (sometimes), and even place names like 代々木 ( よよぎ ) (Yoyogi [Park]). There used to be repeaters for kana too, but they're hardly ever used nowadays. They look like this:

- Hiragana unvoiced: ゝ

- Katakana unvoiced: ヽ

- Hiragana voiced: ゞ

- Katakana voiced: ヾ

ヶ: 箇 & 个 Replacement

This may look like a small katakana ケ (and it is), but it's also used as a replacement for the counter 箇 (か), especially in months: ヶ月 (かげつ). See how it isn't read け, but か? So when you come across 5ヶ月, you read it as ごかげつ, or five months. You'll also see it pop up in place names like Chigasaki 茅ヶ崎市 ( ちがさきし ) , and Sekigahara 関ケ原町 ( せきがはら ) . But instead of か, it's pronounced が because rendaku . Totally not confusing, right?

- ¥ 円記号 (えんきごう)

- ¥ Yen Symbol

The yen symbol is used just like the dollar sign $ in English. You put it before the numbers it's referencing. You'll see this anywhere money is involved like receipts, price tags, online stores. But make sure you don't accidentally write this: ¥100円. 円 is the kanji for yen. You need to pick! It's either ¥100 or 100円.

- 〒〶 郵便記号 (ゆうびんきごう) or 郵便マーク (ゆうびんまーく)

- 〒〶 Postal Mark

This postal mark is used on addresses to indicate the postal code. That's pretty important if you have a Japanese pen-pal or if you're going to be mailing things in Japan. The one in the circle is usually on maps for post offices, so if you need to find the post office, look for this symbol. They're on mailboxes too, usually in red and white, unlike the American blue you may be used to.

There are plenty of other punctuation marks in Japanese , but these are the main ones (or the ones that I thought were important to learn). You'll also see a bunch of different brackets, colons, and so on in Japanese. But it should be pretty simple to understand how they're used and what they're doing there, now that you've learned the rules I've laid out here.

That does bring me to one last thing, which I think is pretty interesting, and that is:

Kaomoji As Japanese Punctuation

Kaomoji 顔文字 ( かおもじ ) , which translates to "Face Letters", is using text to draw little faces which show some kind of emotion. They're basically Japanese emoticons. While kaomoji will probably never be officially considered punctuation, I feel like it is a sort of new wave post-modern neo-punctuation.

When put together, they are characters that represent strong emotion, like the exclamation mark. They can also represent confusion or a questioning tone, like a question mark. On top of that, there are probably 20-30 different "feelings" they can represent that add to your sentences or paragraphs or phrases. While they aren't a single character (neither is an ellipsis, so take that punctuation snobs!), they do represent something which adds feeling to the sentence. That's basically what punctuation does, so why not kaomoji too?

If kaomoji can indeed be considered punctuation, there'd be a lot of them— too many to add to this list. Good thing we have a big kaomoji guide .

In terms of using kaomoji in Japanese, they usually go at the end of sentences or phrases. Think of them as periods that also convey emotion. Take that period! Go back to your soulless home in the country of boring-ville ヾ(♛;益;♛)ノ

Anyways, there you have it. I hope you learned something new, and thought about kaomoji a little bit, too. There really isn't a lot to learn when it comes to Japanese punctuation because you have most of the concepts down already (assuming you're not reading this as a tiny baby). It's really the subtleties that are interesting, I think, so enjoy them but don't get too hung up on them.

Main Navigation

- Contact NeurIPS

- Code of Ethics

- Code of Conduct

- Create Profile

- Journal To Conference Track

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Proceedings

- Future Meetings

- Exhibitor Information

- Privacy Policy

NeurIPS 2024

Conference Dates: (In person) 9 December - 15 December, 2024

Homepage: https://neurips.cc/Conferences/2024/

Call For Papers

Abstract submission deadline: May 15, 2024

Full paper submission deadline, including technical appendices and supplemental material (all authors must have an OpenReview profile when submitting): May 22, 2024

Author notification: Sep 25, 2024

Camera-ready, poster, and video submission: Oct 30, 2024 AOE

Submit at: https://openreview.net/group?id=NeurIPS.cc/2024/Conference

The site will start accepting submissions on Apr 22, 2024

Subscribe to these and other dates on the 2024 dates page .

The Thirty-Eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024) is an interdisciplinary conference that brings together researchers in machine learning, neuroscience, statistics, optimization, computer vision, natural language processing, life sciences, natural sciences, social sciences, and other adjacent fields. We invite submissions presenting new and original research on topics including but not limited to the following:

- Applications (e.g., vision, language, speech and audio, Creative AI)

- Deep learning (e.g., architectures, generative models, optimization for deep networks, foundation models, LLMs)

- Evaluation (e.g., methodology, meta studies, replicability and validity, human-in-the-loop)

- General machine learning (supervised, unsupervised, online, active, etc.)

- Infrastructure (e.g., libraries, improved implementation and scalability, distributed solutions)

- Machine learning for sciences (e.g. climate, health, life sciences, physics, social sciences)

- Neuroscience and cognitive science (e.g., neural coding, brain-computer interfaces)

- Optimization (e.g., convex and non-convex, stochastic, robust)

- Probabilistic methods (e.g., variational inference, causal inference, Gaussian processes)

- Reinforcement learning (e.g., decision and control, planning, hierarchical RL, robotics)

- Social and economic aspects of machine learning (e.g., fairness, interpretability, human-AI interaction, privacy, safety, strategic behavior)

- Theory (e.g., control theory, learning theory, algorithmic game theory)

Machine learning is a rapidly evolving field, and so we welcome interdisciplinary submissions that do not fit neatly into existing categories.

Authors are asked to confirm that their submissions accord with the NeurIPS code of conduct .

Formatting instructions: All submissions must be in PDF format, and in a single PDF file include, in this order:

- The submitted paper

- Technical appendices that support the paper with additional proofs, derivations, or results

- The NeurIPS paper checklist

Other supplementary materials such as data and code can be uploaded as a ZIP file

The main text of a submitted paper is limited to nine content pages , including all figures and tables. Additional pages containing references don’t count as content pages. If your submission is accepted, you will be allowed an additional content page for the camera-ready version.

The main text and references may be followed by technical appendices, for which there is no page limit.

The maximum file size for a full submission, which includes technical appendices, is 50MB.

Authors are encouraged to submit a separate ZIP file that contains further supplementary material like data or source code, when applicable.

You must format your submission using the NeurIPS 2024 LaTeX style file which includes a “preprint” option for non-anonymous preprints posted online. Submissions that violate the NeurIPS style (e.g., by decreasing margins or font sizes) or page limits may be rejected without further review. Papers may be rejected without consideration of their merits if they fail to meet the submission requirements, as described in this document.

Paper checklist: In order to improve the rigor and transparency of research submitted to and published at NeurIPS, authors are required to complete a paper checklist . The paper checklist is intended to help authors reflect on a wide variety of issues relating to responsible machine learning research, including reproducibility, transparency, research ethics, and societal impact. The checklist forms part of the paper submission, but does not count towards the page limit.

Please join the NeurIPS 2024 Checklist Assistant Study that will provide you with free verification of your checklist performed by an LLM here . Please see details in our blog

Supplementary material: While all technical appendices should be included as part of the main paper submission PDF, authors may submit up to 100MB of supplementary material, such as data, or source code in a ZIP format. Supplementary material should be material created by the authors that directly supports the submission content. Like submissions, supplementary material must be anonymized. Looking at supplementary material is at the discretion of the reviewers.

We encourage authors to upload their code and data as part of their supplementary material in order to help reviewers assess the quality of the work. Check the policy as well as code submission guidelines and templates for further details.