Pathways of Addiction: Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research (1996)

Chapter: 1. introduction, 1 introduction.

Drug abuse research became a subject of sustained scientific interest by a small number of investigators in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Despite their creative efforts to understand drug abuse in terms of general advances in biomedical science, the medical literature of the early twentieth century is littered with now-discarded theories of drug dependence, such as autointoxication and antibody toxins, and with failed approaches to treatment. Eventually, escalating social concern about the use of addictive drugs and the emergence of the biobehavioral sciences during the post-World War II era led to a substantial investment in drug abuse research by the federal government (see Appendix B ). That investment has yielded substantial advances in scientific understanding about all facets of drug abuse and has also resulted in important discoveries in basic neurobiology, psychiatry, pain research, and other related fields of inquiry. In light of how little was understood about drug abuse such a short time ago, the advances of the past 25 years represent a remarkable scientific accomplishment. Yet there remains a disconnect between what is now known scientifically about drug abuse and addiction, the public's understanding of and beliefs about abuse and addiction, and the extent to which what is known is actually applied in public health settings.

During its brief history, drug abuse research has been supported mainly by the federal government, with occasional investments by major private foundations. At the federal level, the lead agency for drug abuse research is the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which supports

85 percent of the world's research on drug abuse and addiction. Other sponsoring agencies include the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), all in the Department of Health and Human Services; as well as the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) in the Department of Justice. Throughout the federal government, the FY 1995 investment in drug abuse research and development was $542.2 million, which represents 4 percent of the $13.3 billion spent by the federal government on drug abuse (ONDCP, 1996). By comparison, $8.5 billion (64 percent of the FY 1995 budget) was spent on criminal justice programs, 1 $2.7 billion (20 percent) on treatment of drug abuse, and $1.6 billion (12 percent) on prevention efforts.

In 1992, the General Accounting Office (GAO) released a report Drug Abuse Research: Federal Funding and Future Needs, which recommended that Congress review the place of research in drug control policy and its modest 4 percent share of the drug control budget. The report questioned whether the federal commitment to research was adequate, given the enormity of research needs (GAO, 1992), and whether adequate evaluation research was being conducted to determine the efficacy of various drug control programs. In FY 1995, drug abuse research was still little more than 4 percent of the entire drug control budget.

In January 1995, NIDA requested the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to examine accomplishments in drug abuse research and provide guidance for future research opportunities. This report by the IOM Committee on Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research focuses broadly on opportunities and priorities for future scientific research in drug abuse. After a brief review of major accomplishments in drug abuse research, the remainder of this chapter discusses the vocabulary and basic concepts used in the report, highlights the importance of the nation's investment in drug abuse research, and explores some of the factors that could improve the yield from that investment.

MAJOR ACHIEVEMENTS IN DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

There have been remarkable achievements in drug abuse research over the past quarter of a century as researchers have learned more about the biological and psychosocial aspects of drug use, abuse, and dependence. Behavioral researchers have developed animal and human mod-

|

| Criminal justice programs include interdiction, investigation, international efforts, prosecution, correction efforts, and intelligence programs. |

els of drug-seeking behavior, that have, for example, yielded objective measures of initiation and repeated administration of drugs, thereby providing the scientific foundation for assessments of "abuse liability" (i.e., the potential for abuse) of specific drugs (see Chapter 2 ). This information is an essential predicate for informed regulatory decisions under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and the Controlled Substances Act. Taking advantage of technological advances in molecular biology, neuroscientists have identified receptors or receptor types in the brain for opioids, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and marijuana and have described the ways in which the brain adapts to, and changes after, exposure to drugs. Those alterations, which may persist long after the termination of drug use, appear to involve changes in gene expression. They may explain enhanced susceptibility to future drug exposure, thereby shedding light on the enigmas of withdrawal and relapse at the molecular level (see Chapter 3 ). Epidemiologists have designed and implemented epidemiological surveillance systems that enable policymakers to monitor patterns of drug use in the population ( Chapter 4 ) and that enable researchers to investigate the causes and consequences of drug use and abuse (Chapters 5 and 7 , respectively). Paralleling broader trends in health promotion and disease prevention in the past 20 years, the field of drug abuse prevention has made significant progress in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions implemented in a range of settings including communities, schools, and families (see Chapter 6 ).

Marked gains have also been made in treatment research, including improvements in diagnostic criteria; development of a wide range of treatment interventions and sophisticated methods to assess treatment outcome; and development and approval of Leo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM), a medication for the treatment of opioid dependence. Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments, alone or in combination, have been shown to be effective for drug dependencies, and treatment has been shown to reduce drug use, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection rates, health care costs, and criminal activity (see Chapter 8 ).

Drug abuse researchers have also made major contributions to knowledge in adjacent fields of scientific inquiry. For example, NIDA-sponsored research was the driving force in the identification of morphine-like substances that serve as neurotransmitters in specific neurons located throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems (Orson et al., 1994). Identification of these substances represents a dramatic breakthrough in understanding the mechanisms of pain, reinforcement, and stress. Additionally, the discovery of opioid peptides as neurotransmitters played a key role in the identification of numerous other peptide neurotransmitters (Cooper et al., 1991; Goldstein, 1994; Hokfelt et al., 1995). These discoveries have broadened the understanding of brain function and now

form the basis of many current strategies in the design of new drug treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders. Additionally, drug abuse research has contributed to the development of brain imaging techniques.

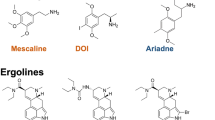

Drug abuse research has also provided a major impetus for neuropharmacological research in psychiatry since the late 1950s, when it was discovered that LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide; a hallucinogen that produces psychotic symptoms) affected the brain's serotonin systems (Cooper et al., 1991). That seminal discovery stimulated decades of research in the neuropharmacological basis of behavior and psychiatric disorders. The impact on antipsychotic research has been dramatic. In addition, stimulants (e.g., cocaine and amphetamine) were found to produce a state of paranoid psychosis, resembling schizophrenia, in some people. The actions of stimulants on the brain's dopamine pathways continue to inform researchers of the potential role of those pathways in the treatment, and perhaps the pathophysiology, of schizophrenia (Kahn and Davis, 1995). Drug abuse research also has had an impact on antidepressant research (e.g., the actions of drugs of abuse on the brain's serotonin systems have provided useful models with which to investigate the role of those systems in depression and mania). Depression is a risk factor for treatment failure in smoking cessation (Glassman et al., 1993) and depression-like symptoms are dominant during cocaine withdrawal (DiGregorio, 1990). Consequently, treatment of depression in nicotine and cocaine-dependent individuals has been an area of interest for drug abuse research.

Some drugs that are abused, most notably the opioid analgesics, have essential medical uses. Since its founding, NIDA has been the major supporter of research into brain mechanisms of pain and analgesia, analgesic tolerance, and analgesic pharmacology. The resulting discoveries have led to an understanding of which brain circuits are required to generate pain and pain relief (Wall and Melzack, 1994), have revolutionized the treatment of postoperative and cancer pain (Folly and Interesse, 1986; Car et al., 1992; Jacob et al., 1994), and have led to improved treatments for many other conditions that result in chronic pain (see Chapter 3 ).

VOCABULARY OF DRUG ABUSE

Ordinarily, scientific vocabulary evolves toward greater clarity and precision in response to new empirical discoveries and reconceptualizations. That creative process is evident within each of the disciplines of drug abuse research covered in various chapters of this report. Interestingly, however, the words describing the field as a whole, and connecting each chapter to the next, seem to defy the search for clarity and precision. Does "drug" include alcohol and tobacco? What is "abuse"? Are use and

abuse mutually exclusive categories? Are abuse and dependence mutually exclusive categories? Does use of illicit drugs per se amount to abuse? Does abuse include underage use of nicotine? Is addiction synonymous with dependence?

These ambiguities have persisted for decades because the vocabulary of drug abuse is inevitably influenced by peoples' attitudes and values. If the task were solely a scientific one, precise terminology would have emerged long before now. However, because the choice of words in this field always carries a nonscientific message, scientists themselves cannot always agree on a common vocabulary.

Consider the case of nicotine; from a pharmacological standpoint, nicotine is functionally similar to other psychoactive drugs. However, many researchers and policymakers choose to exclude nicotine from the category of drug. The same is true of alcohol; for example, other terms, such as ''chemical dependency" or "substance abuse," are often used as generic terms encompassing the abuse of nicotine and alcohol as well as abuse of illicit drugs. This semantic strategy is chosen to signify the difference in legal status among alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs. In recent years, however, a growing number of researchers have adopted a more inclusive use of the term drug. In the case of nicotine, this move tends to reflect a policy judgment that nicotine should be classified as a drug under the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.

In the committee's view, the term drug should be understood, in its generic sense, to encompass alcohol and nicotine as well as illicit drugs. It is very important for the general public to recognize that alcohol and nicotine constitute, by far, the nation's two largest drug problems, whether measured in terms of morbidity, mortality, or social cost. Abuse of and dependence on those drugs have serious individual and societal consequences. Continued separation of alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs in everyday speech is an impediment to public education, prevention, and therapeutic progress.

Although the committee uses the term drug, in its generic sense, to encompass alcohol and nicotine, the report focuses, at NIDA's request, on research opportunities relating to illicit drugs; research on alcohol and nicotine is discussed only when the scientific inquiries are intertwined. Because the report sometimes ranges more broadly than illicit drugs, however, the committee has adopted several semantic conventions to promote clarity and avoid redundancy. First, the term drug, unmodified, refers to all psychoactive drugs, including alcohol and nicotine. When reference is intended solely to illicit drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and other drugs regulated by the Controlled Substances Act, the committee says so explicitly. Occasionally, to ensure that the intended meaning is clear, the report refers to "illicit drugs and nicotine" or to "illicit drugs

and alcohol," as the case may be. Additionally, the words opiate and opioid are used interchangeably, although opiates are derivative of morphine and opioids are all compounds with morphine-like properties (they may be synthetic and not resemble morphine chemically).

The report employs the standard three-stage conceptualization of drug-taking behavior that applies to all psychoactive drugs, whether licit or illicit. Each stage—use, abuse, dependence—is marked by higher levels of use and increasingly serious consequences. Thus, when the report refers to the "use" of drugs, the term is usually employed in a narrow sense to distinguish it from intensified patterns of use. Conversely, the term "abuse" is used to refer to any harmful use, irrespective of whether the behavior constitutes a "disorder'' in the DSM-IV diagnostic nomenclature (see Appendix C ). When the intent is to emphasize the clinical categories of abuse and dependence, that is made clear.

The committee also draws a clear distinction between patterns of drug-taking behavior, however described, and the harmful consequences of that behavior for the individual and for society. These consequences include the direct, acute effects of drug taking such as a drug-induced toxic psychosis or impaired driving, the effects of repeated drug taking on the user's health and social functioning, and the effects of drug-seeking behavior on the individual and society. It bears emphasizing that adverse consequences can be associated with patterns of drug use that do not amount to abuse or dependence in a clinical sense, although the focus of this report and the committee's recommendations is on the more intensified patterns of use (i.e., abuse and dependence) since they cause the majority of the serious consequences.

DEFINITIONS AND BASIC CONCEPTS

Drug use may be defined as occasional use strongly influenced by environmental factors. Drug use is not a medical disorder and is not listed as such in either of the two most important diagnostic manuals—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSMIV; APA, 1994); or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10; WHO, 1992). (See Appendix C for DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria.) Drug use implies intake for nonmedical purposes; it may or may not be accompanied by clinically significant impairment or distress on a given occasion.

Drug abuse is characterized in DSM-IV as including regular, sporadic, or intensive use of higher doses of drugs leading to social, legal, or interpersonal problems. Like DSM-IV, ICD-10 identifies a nondependent but problematic syndrome of drug use but calls it "harmful use" instead

of abuse. This syndrome is defined by ICD-10 as use resulting in actual physical or psychological harm.

Drug dependence (or addiction) is characterized in both DSM-IV and ICD-10 as drug-seeking behavior involving compulsive use of high doses of one or more drugs, either licit or illicit, for no clear medical indication, resulting in substantial impairment of health and social functioning. Dependence is usually accompanied by tolerance and withdrawal 2 and (like abuse) is generally associated with a wide range of social, legal, psychiatric, and medical problems. Unlike patients with chronic pain or persistent anxiety, who take medication over long periods of time to obtain relief from a specific medical or psychiatric disorder (often with resulting tolerance and withdrawal), persons with dependence seek out the drug and take it compulsively for nonmedical effects.

Tolerance occurs when certain medications are taken repeatedly. With opiates for example, it can be detected after only a few days of use for medical purposes such as the treatment of pain. If the patient suddenly stops taking the drug, a withdrawal syndrome may ensue. Physicians often confuse this phenomenon, referred to as physical dependence, with true addiction. That can lead to withholding adequate medication for the treatment of pain because of the very small risk that addiction with drug-seeking behavior may occur.

As a consequence of its compulsive nature involving the loss of control over drug use, dependence (or addiction) is typically a chronically relapsing disorder (IOM, 1990, 1995; Meter, 1996; O'Brien and McLennan, 1996; McLennan et al., in press). Although individuals with drug dependence can often complete detoxification and achieve temporary abstinence, they find it very difficult to sustain that condition and avoid relapse over time. Most persons who achieve sustained remission do so only after a number of cycles of detoxification and relapse (Dally and Marital, 1992). Relapse is caused by a constellation of biological, family, social, psychological, and treatment factors and is demonstrated by the fact that at least half of former cigarette smokers quit three or more times before they successfully achieve stable remission from nicotine addiction (Schilling, 1992). Similarly, within one year of treatment, relapse occurs in 30-50 percent of those treated for drug dependence, although the level

|

| Tolerance refers to the situation in which repeated administration of a drug at the same dose elicits a diminishing effect or involves the need for an increasing dose to produce the same effect. Withdrawal syndrome is characterized by physical or motivational disturbances when the drug is withdrawn. It is important to emphasize that the phenomena of tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal are not associated uniquely with drugs of abuse, since many medications used clinically that are not addicting (e.g., clonidine, propranolol, tricyclic antidepressants) can produce these types of effects. |

of drug use may not be as high as before treatment (Daley and Marlatt, 1992; McLellan et al., in press). Unlike those who use (or even abuse) drugs, individuals with addiction have a substantially diminished ability to control drug consumption, a factor that contributes to their tendency to relapse.

Another terminological issue arises in relation to the terms addiction and dependence. For some scientists, the proper terms for compulsive drug seeking is addiction, rather than dependence. In their view, addiction more clearly signifies the essential behavioral differences between compulsive use of drugs for their nonmedical effects and the syndrome of "physical dependence" that can develop in connection with repeated medical use. In response, many scientists argue that dependence has been defined in both ICD-10 and DSM-IV to encompass the behavioral features of the disorder and has become the generally accepted term in the diagnostic nomenclature. Moreover, some scientists object to the term addiction on the grounds that it is associated with stigmatizing social images and that a less pejorative term would help to promote public understanding of the medical nature of the condition. The committee has not attempted to resolve this controversy. For purposes of this report, the terms addiction and dependence are used interchangeably.

An inherent aspect of drug addiction is the propensity to relapse. Relapse should not be viewed as treatment failure; addiction itself should be considered a brain disease similar to other chronic and relapsing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma (IOM, 1995; O'Brien and McLellan, 1996). In the latter, significant improvement is considered successful treatment even though complete remission or cure is not achieved. In the area of drug abuse, however, many individuals (both lay and professional) expect treatment programs to perform like vaccine programs, where one episode of treatment offers lifetime immunity. Not surprisingly, because of that expectation, people are inevitably disappointed in the relatively high relapse rates associated with most treatments. If, however, addiction is understood as a chronically relapsing brain disease, then—for any one treatment episode—evidence of treatment efficacy would include reduced consumption, longer abstention periods, reduced psychiatric symptoms, improved health, continued employment, and improved family relations. Most of those results are demonstrated regularly in treatment outcome studies.

The idea that drug addiction is a chronic relapsing condition, requiring long-term attention, has been resisted in the United States and in some other countries (Brewley, 1995). Many lay people view drug addiction as a character defect requiring punishment or incarceration. Proponents of the medical model, however, point to the fact that addiction is a distinct morbid process that has characteristics and identifiable signs and

symptoms that affect organ systems (Miller, 1991; Meter, 1996). Characterization of addiction as a brain disease is bolstered by evidence of genetic vulnerability to addiction, physical correlates of its clinical course, physiological changes as a result of repeated drug use, and fundamental changes in brain chemistry as evidenced by brain imaging (Volkow et al., 1993). This is not to say that behavioral, social, and environmental factors are immaterial—they all play a role in onset and outcome, just as they do in heart disease, kidney disease, tuberculosis, or other infectious diseases. Thus, the contemporary understanding of disease fully incorporates the voluntary behavioral elements that lead many people to be skeptical about the applicability of the medical model to drug addiction. In any case, the committee embraces the disease concept, not because it is indisputable but because this paradigm facilitates scientific investigation in many important areas of knowledge, without inhibiting or distorting scientific inquiry in other parts of the field.

IMPORTANCE OF DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

The widespread prevalence of illicit drug use in the United States is well documented in surveys of households, students, and prison and jail inmates ( Chapter 4 ). Based on the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA), an annual survey presently sponsored by SAMHSA, it was estimated that in 1994, 12.6 million people had used illicit drugs (primarily marijuana) in the past month (SAMHSA, 1995). That figure represents 6 percent of the population 12 years of age or older. 3 The number of heavy drug users, using drugs at least once a week, is difficult to determine. It has been estimated that in 1993 there were 2.1 million heavy cocaine users and 444,000-600,000 heavy heroin users (Rhodes et al., 1995). This population represents a significant burden to society, not only in terms of federal expenditures but also in terms of costs related to the multiple consequences of drug abuse (see Chapter 7 ).

The ultimate aim of the nation's investment in drug abuse research is to enable society to take effective measures to prevent drug use, abuse, and dependence, and thereby reduce its adverse individual and social consequences and associated costs. The adverse consequences of drug abuse are numerous and profound and affect the individual's physical health and psychological and social functioning. Consequences of drug abuse include increased rates of HIV infection and tuberculosis (TB); education and vocational impairment; developmental harms to children of

|

| It is important to note that the total number of users results from the rates of use in different age groups in the population and from the demographic structure of the population. The actual number of users may increase while the rates of use are declining. |

drug-using parents associated with fetal exposure or maltreatment and neglect; and increased violence (see Chapter 7 ). It now appears that injection drug use is the leading risk factor for new HIV infection in the United States (Holmberg, 1996). Most (80 percent) HIV-infected heterosexual men and women who do not use injection drugs have been infected through sexual contact with HIV-infected injection drug users (IUDs). Thus, it is not surprising that the geographic distribution of heterosexual AIDS cases has been essentially the same as the distribution of male injection drug users' AIDS cases (Holmberg, 1996) Further, the IUDs-associated HIV epidemic in men is reflected in the heterosexual epidemic in women, which is reflected in HIV infection in children (CDC, 1995). Nearly all children who acquire HIV infection do so prenatal (see Chapter 7 ).

The extent of the impact of drug use and abuse on society is evidenced by its enormous economic burden. In 1990, illicit drug abuse is estimated to have cost the United States more than $66 billion. When the cost of illicit drug use and abuse is tallied with that of alcohol and nicotine ( Table 1.1 ), the collective cost of drug use and abuse exceeds the estimated annual $117 billion cost of heart disease and the estimated annual $104 billion cost of cancer (AHA, 1992; ACS, 1993; D. Rice, University of California at San Francisco, personal communication, 1995).

As noted above, the federal government accounts for a large segment of the societal expenditure on illicit drug abuse control—spending more than $13.3 billion in FY 1995 (ONDCP, 1996). About two-thirds was devoted to interdiction, intelligence, incarceration, and other law enforcement activities. Research, however, accounts for only 4 percent of federal outlays, a percentage that has remained virtually unchanged since 1981 (ONDCP, 1996) ( Figure 1.1 ). Given the social costs of illicit drug abuse and the enormity of the federal investment in prevention and control, research into the causes, consequences, treatment, and prevention of drug abuse should have a higher priority. Enhanced support for drug abuse research would be a socially sound investment, because scientific research can be expected to generate new and improved treatments, as well as prevention and control strategies that can help reduce the enormous social burden associated with drug abuse.

THE CONTEXT OF DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

In the chapters that follow, the committee identifies research initiatives that seem most promising and most likely to lead to successful efforts to reduce drug abuse and its associated social costs. Although the yield from these initiatives will depend largely on the creativity and skill of scientists, the many contextual factors that will also have a major bear-

TABLE 1.1 Estimated Economic Costs (million dollars) of Drug Abuse, 1990

|

| Illicit Drugs | Alcohol | Nicotine |

| Total | $66,873 | $98,623 | $91,269 |

| Core Costs | 14,602 | 80,763 | 91,269 |

| Direct | 3,197 | 10,512 | 39,130 |

| Mental health/specialty organizations | 867 | 3,469 | — |

| Short-stay hospitals | 1,889 | 4,589 | 21,072 |

| Office-based physicians | 88 | 240 | 12,251 |

| Other professional services | 32 | 329 | — |

| Prescription drugs | — | — | 1,469 |

| Nursing homes | — | 1,095 | 3,858 |

| Home health services | — | — | 480 |

| Support costs | 321 | 790 | — |

| Indirect | 11,405 | 70,251 | 52,139 |

| Morbidity | 7,997 | 36,627 | 6,603 |

| Mortality | 3,408 | 33,624 | 45,536 |

| Other Related Costs | 45,989 | 15,771 | — |

| Direct | 18,043 | 10,436 | — |

| Crime | 18,035 | 5,807 | — |

| Motor vehicle crashes | — | 3,876 | — |

| Fire destruction | — | 633 | — |

| Social welfare administration | 8 | 120 | — |

| Indirect | 27,946 | 5,335 | — |

| Victims of crime | 1,042 | 576 | — |

| Incarceration | 7,813 | 4,75 | — |

| Crime careers | 19,091 | — | — |

| AIDS | 6,282 | — | — |

| Fetal Alcohol Syndrome |

| 2,089 | — |

| NOTE: 1990 costs for illicit drugs and alcohol abuse are based on socioeconomic indexes applied to 1985 estimates (Rice et al., 1990; cigarette direct smoking costs are deflated from 1993 direct cost estimates (MMWR, 1994); cigarette indirect costs are from Rice et al., 1992. Amounts spent for other professional services are included in office-based physicians' costs. Value of goods and services lost by individuals unable to perform their usual activities because of drug abuse or unable to perform them at a level of full effectiveness (Rice et al., 1990). Present value of future earnings lost, illicit drugs and alcohol discounted at 6 percent, nicotine discounted at 4 percent. SOURCE: D. Rice, University of California at San Francisco, personal communication (1995). | |||

FIGURE 1.1 Federal drug control budget trends (1981-1995). NOTE: Figures are in current dollars. SOURCE: ONDCP (1996).

ing on the payoff from scientific inquiry cannot be ignored. The committee has identified six major factors that, if successfully addressed, could optimize the gains made in each area of drug abuse research: stable funding; use of a comprehensive public health framework; wider acceptance of a medical model of drug dependence; better translation of research findings into practice; raising the status of drug abuse research; and facilitating interdisciplinary research.

Stable Funding

A stable level of funding in any area of biomedical research is needed to sustain and build on research accomplishments, to retain a cadre of experts in a field, and to attract young investigators. Drug abuse research, in comparison with many other research venues, has not enjoyed consistent federal support (IOM, 1990, 1995; see also Appendix B ). The field has suffered from difficulties in recruiting and retaining young researchers and clinicians and in maintaining a stable research infrastructure (IOM, 1995). Society's capacity to contain and manage drug abuse

depends upon a stable, long-term investment in research. The vicissitudes in federal research funding often reflect changing currents in public opinion toward drugs and drug users ( Appendix B ). However, drug abuse will not disappear; it is an endemic social and public health problem. The nation must commit itself to a sustained effort. The social investment in research is an investment in "human capital" that must be sustained over the long term in order to reap the expected gains. An investment in this field is squandered if researchers who have been recruited and trained in drug abuse research are drawn to other fields because of uncertainty about the stability of future funding.

Adoption of a Comprehensive Public Health Framework

The social impact of drug abuse research can be enhanced significantly by conceptualizing goals and priorities within a comprehensive public health framework (Goldstein, 1994). All too often, public discourse about drug abuse is characterized by such unnecessary and fruitless disputes as whether drug abuse should be viewed as a social and moral problem or a health problem, whether the drug problem can best be solved by law enforcement or by medicine, whether priority should be placed on reducing supply or reducing demand, and so on. The truth is that these dichotomies oversimplify a brain disease impacted by a complex set of behaviors and a diverse array of potentially useful social responses. Forced choices of this nature also tend to inhibit or foreclose potentially useful research strategies. Confusion about social goals can lead to confusion about research priorities and can obscure the links between investigations viewing the subject through different lenses.

Some issues tend to recur. A prominent dispute centers on whether preventing drug use is important in itself or whether society should be more concerned with abuse or with the harmful consequences of use. The answer, of course, is that such a forced choice obscures, rather than clarifies, the issues. From a public health standpoint, drug use is a risk factor; the significance of use (whether of alcohol, nicotine, or illicit drugs) lies in the risk of harm associated with it (e.g., fires from smoking, impaired driving from alcohol or illicit drugs, or developmental setbacks) and in the risk that use will intensify, escalating to abuse or dependence. Those risks vary widely in relation to drug, user characteristics, social context, etc. Attention to the consequences of use and to the risk of escalation helps to set priorities (for research and policy) and provides a framework for assessing the impact of different interventions.

From a public policy standpoint, arguments about goals and priorities are fraught with controversy. From the standpoint of research strategy, however, the key lies in asking the right questions (e.g., What influ-

ences the pathways from use, to abuse, to dependence? What are the effects of needle exchange programs on illicit drug use and on HIV disease?) and in generating the knowledge required to facilitate informed policy debate. The main virtues of a comprehensive public health approach are that it helps to disentangle scientific questions from policy questions and that it encompasses all of the pertinent empirical questions, including the causes and consequences of use, abuse, and dependence, as well as the efficacy and cost of all types of interventions. In sum, the social payoff from drug abuse research can be enhanced substantially by integrating diverse strands of inquiry within a public health framework.

Acceptance of a Medical Model of Drug Dependence

Drug dependence is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that, like other diseases, can be evaluated and treated with the standard tools of medicine, including efforts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment with medications and behavioral or psychosocial therapies. Unfortunately, the medical model of dependence is not universally accepted by health professionals and others in the treatment community; it is widely rejected within the law enforcement community and often by the public at large, which tends to view the complex and varied patterns of use, abuse, and dependence as an undifferentiated behavior rather than a medical problem.

Resistance to the medical model takes many forms. One is resistance to pharmacotherapies, such as methadone, that are seen as substituting licit drugs for illicit drugs without changing drug-taking behavior. Conversely, treatment approaches that adopt a rigid drug-free strategy preclude the use of medications for patients with other psychiatric disorders that are easily treated by pharmacotherapeutic approaches. On a subtler level, resistance to the use of pharmacotherapies is evidenced by the routine use of inadequate doses of methadone (D'Aunno and Vaughn, 1992). Finally, for others, all forms of drug abuse signify a failure of willpower or a moral weakness requiring punishment, incarceration, or moral education rather than treatment (Anglin and Hser, 1992).

Resistance to the medical model of drug dependence presents numerous barriers to research. Clinical researchers experience difficulty in soliciting participation by both treatment program administrators and patients, who are sometimes mistrustful of researchers' motives. If research involves a medication that is itself prone to abuse, there are additional regulatory requirements for drug scheduling, storage, and record keeping that act to discourage investigation (see Chapter 10 ; IOM, 1995). The ever-present threat of inappropriate intrusion by law enforcement agents has a chilling effect on treatment research (McDuff et al., 1993). All barri-

ers to inquiry, irrespective of whether they are legal or social in origin, raise the cost of research and discourage researchers from entering the field. Additionally, those barriers diminish the likelihood that a pharmaceutical company will invest in the development of antiaddiction medications (IOM, 1995). 4 Broader acceptance of the medical model of drug dependence would provide an incentive for researchers and clinicians to enter this field of research. Over time, a developing consensus in support of the medical model could facilitate common discourse, help to shape a shared research agenda within a public health framework, and diminish tensions between the research and treatment communities and the criminal justice system.

Better Translation of Research Findings into Practice and Policy

To benefit society, new research findings must be disseminated adequately to treatment providers, educators, law enforcement officials, and community leaders. In the case of prevention practices, it is often difficult for communities to change entrenched policies, particularly when combined with political imperatives for action to counteract drug abuse. In the case of treatment, technology transfer is impeded by the heterogeneity of providers and their marginalization at the outskirts of the medical community (see IOM, 1990, 1995; see also Chapter 8 ). Physicians and psychiatrists are seldom employed by specialized drug treatment facilities (approximately one-quarter employ medical doctors), and treatment is delivered by counselors whose training and supervision vary greatly and who have little access to and understanding of research results (Ball and Ross, 1991; Batten et al., 1993). These factors not only impede the transfer of research findings to the field but also impede communication from the field to the laboratory so that research designs can be modified in response to clinical realities (Pentz, 1994). Thus, there is a real need for bidirectional communication, from bench to bedside and back to the basic scientist (IOM, 1994).

The committee is aware, however, of recent technology transfer efforts in the field such as the Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, an initiative to establish guidelines for drug abuse treatment with an emphasis on incorporating research findings (SAMHSA, 1993), and the Prevention Enhancement Protocol System, a process implemented by the Center

|

| In recognition of the barriers to pharmaceutical company investment in this area of drug development, Congress in 1990 created NIDA's Medications Development Division (IOM, 1990) to stimulate the discovery and development of new medications for the treatment of drug abuse. |

for Substance Abuse Prevention in which scientists and practitioners develop protocols to identify and evaluate the strength of evidence on topics related to prevention interventions. Similar efforts will be invaluable for communicating and integrating research results to the treatment community.

Research frequently results in product development leading to changes in operations and an overall enhancement of the value of the enterprise. For example, in the pharmaceutical industry research often leads to the development of new medications or devices. In the public sector, however, research is often divorced from the implementation of findings and development. Research is often more basic than applied, and the fruits of research are not realized by the government, but by the private sector. Although that approach may be appropriate, it is unfortunately not always the most productive strategy for advancing research, knowledge, and product development. That is particularly true in the development of medications for opiate and cocaine addictions, where there is a great need for commitment from the private sector. However, many obstacles prevent active involvement of the pharmaceutical industry in this area of research and development (IOM, 1995).

A similar problem arises in relation to policymaking. Because debates about drug policy tend to be so highly polarized and politicized, research findings are often distorted, or selectively deployed, for rhetorical purposes. Researchers cannot prevent this practice, which is a common feature of political debate in a democratic society. However, researchers and their sponsors should not be indifferent to the disconnect between policy discourse and science. Researchers should establish and support institutional mechanisms for communicating an important message to policymakers and to the general public. Scientific research has produced a solid, and growing, body of knowledge about drug abuse and about the efficacy of various interventions that aim to prevent and control it. As long as drug abuse remains a poorly understood social problem, policy will be based mainly on wish and supposition; steps should be taken to educate policymakers about the scientific and technological advances in addiction research. Only then will it be possible for policymaking to support legislation that adequately funds new research and applies research findings. To some extent, persisting failure to reap the fruits of drug abuse research is attributable to the low visibility of the field—a problem to which the discussion now turns.

Raising the Status of Drug Abuse Research

Drug abuse research is often an undervalued area of inquiry, and most scientists and clinicians choose other disciplines in which to develop

their careers. Compared with other fields of research, investigators in drug abuse are often paid less, have less prestige among their peers, and must contend with the unique complexities of performing research in this area (e.g., regulations on controlled substances) (see IOM, 1995). The overall result is an insufficient number of basic and clinical researchers. IOM has recently begun a study, funded by the W. M. Keck Foundation of Los Angeles, to develop strategies to raise the status of drug abuse research. 5

Weak public support for this field of study is evident in unstable federal funding (see above), a lack of pharmaceutical industry investment in the development of antiaddiction medications (IOM, 1995), and inadequate funding for research training (IOM, 1995). NIDA's FY 1994 training budget, which is crucial to the flow of young researchers into the field, was about 2 percent of its extramural research budget, a percentage substantially lower than the overall National Institutes of Health (NIH) training budget, which averages 4.8 percent of its extramural research budget.

Beyond funding problems, investigators face a host of barriers to research: research subjects may pose health risks (e.g., TB, HIV/AIDS, and other infectious diseases), may be noncompliant, may deny their drug abuse problems, and may be involved in the criminal justice system. Even when research is successful and points to improvements in service delivery, the positive outcome may not be translated into practice or policy. For example, more than a year after the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) approval of levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM) as the first new medication for the treatment of opiate dependence in over 20 years, fewer than 1,000 patients nationwide actually had received the medication (IOM, 1995). More recently, scientific evidence regarding the beneficial effects of needle exchange programs (NRC, 1995) has received inadequate attention. Continuing indifference to scientific progress in drug abuse research inevitably depresses the status of the field, leading in turn to difficulties in recruiting new investigators.

Increasing Interdisciplinary Research

The breadth of expertise needed in drug abuse research spans many disciplines, including the behavioral sciences, pharmacology, medicine, and the neurosciences, and many fields of inquiry, including etiology, epidemiology, prevention, treatment, and health services research. Aspects of research relating to drug use tend to draw on developmental perspectives and to focus on general population samples in community settings, especially schools. Aspects of research relating to abuse and de-

|

| The report on raising the profile of drug abuse will be published in the Fall of 1996. |

pendence tend to be more clinical in nature, drawing on psychopathological perspectives. Additionally, a full account of any aspect of drug-taking behavior must also reflect an understanding of social context. The rich interplay between neuroscience and behavioral research and between basic and clinical research poses distinct challenges and opportunities.

Unfortunately, research tends to be fragmented within disciplinary boundaries. The difficulties in conducting successful interdisciplinary research are well known. Funds for research come from many separate agencies, such as the NIDA, NIMH, and SAMHSA. These agencies all have different programmatic emphases as they attempt to shape the direction of research in their respective fields. In times of funding constraints, agencies may be less inclined to fund projects at the periphery of their interests.

Additionally, NIH study sections, which rank grant proposals, are discipline specific, making it difficult for interdisciplinary proposals to ''qualify" (i.e., receive a high rank) for funding. Another problem is that the most advanced scientific literature tends to be compartmentalized within discipline or subject matter categories, making it difficult for scientists to see the whole field. The problem is exacerbated by what Tonry (1990) has called "fugitive literatures," studies carried out by private sector research firms or independent research agencies and available only in reports submitted to the sponsoring agency.

In light of lost opportunities for collaboration and interdisciplinary research, IOM (1995) previously recommended the creation and expansion of comprehensive drug abuse centers to coordinate all aspects of drug abuse research, training, and treatment. The field of drug abuse research presents a real opportunity to bridge the intellectual divide between the behavioral and neuroscience communities and to overcome the logistical impediments to interdisciplinary research.

INVESTING WISELY IN DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

This report sets forth drug abuse research initiatives for the next decade based on a thorough assessment of what is now known and a calculated judgment about what initiatives are most likely to advance our knowledge in useful ways. This report is not meant to be a road map or tactical battle plan, but is best regarded as a strategic outline. Within each discipline of drug abuse research, the committee has highlighted priorities for future research. However, the committee did not make any attempt to prioritize recommendations across varied disciplines and fields of research. Prudent research planning must respond to newly emerging opportunities and needs while maintaining a steady commitment to the

achievement of long-term objectives. The ability to respond to new goals and needs may be the real challenge for the field of drug abuse research.

Drug abuse research is an important public investment. The ultimate aim of that investment is to reduce the enormous social costs attributable to drug abuse and dependence. Of course, drug abuse research must also compete for funding with research in other fields of public health, research in other scientific domains, and other pressing public needs. Recognizing the scarcity of resources, the committee has also considered ways in which the research effort can be harnessed most effectively to increase the yield per dollar invested. These include stable funding, use of a comprehensive public health framework, wider acceptance of a medical model of drug dependence, better translation of research findings into practice and policy, raising the status of drug abuse research, and facilitating interdisciplinary research.

The committee notes that there have been major accomplishments in drug abuse research over the past 25 years and commends NIDA for leading that effort. The committee is convinced that the field is on the threshold of significant advances, and that a sustained research effort will strengthen society's capacity to reduce drug abuse and to ameliorate its adverse consequences.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report sets forth a series of initiatives in drug abuse research. 6 Each chapter of the report covers a segment of the field, describes selected accomplishments, and highlights areas that seem ripe for future research. As noted, the committee has not prioritized areas for future research but, instead, has identified those areas that most warrant further exploration.

Chapter 2 describes behavioral models of drug abuse and demonstrates how the use of behavioral procedures has given researchers the ability to measure drug-taking objectively and to study the development, maintenance, and consequences of that behavior. Chapter 3 discusses drug abuse within the context of neurotransmission; it describes neurobiological advances in drug abuse research and provides the foundation for the current understanding of addiction as a brain disease. The epidemiological information systems designed to gather information on drug use in the United States are identified in Chapter 4 . The data collected from the systems provide an essential foundation for systematic study of

|

| As noted earlier, the primary focus of the report is research on illicit drugs, such as heroin and cocaine. Research on alcohol and nicotine is cited in the text where it has illuminated our knowledge of illicit drug abuse. |

the etiology and consequences of drug abuse, which are addressed, respectively, in Chapters 5 and 7 . Chapter 6 addresses the efficacy of interventions designed to prevent drug abuse. The effectiveness of drug abuse treatment and the difficulties in treating special populations of drug users are discussed in Chapter 8 , while the impact of managed care on access, costs, utilization, and outcomes of treatment is addressed in Chapter 9 . Finally, Chapter 10 discusses the effects of drug control on public health and identifies areas for policy-relevant research.

Specific recommendations appear in each chapter. Although these recommendations reflect the committee's best judgment regarding priorities within the specific domains of research, the committee did not identify priorities or rank recommendations for the entire field of drug abuse research. Opportunities for advancing knowledge exist in all domains. It would be a mistake to invest too narrowly in a few fields of inquiry. At the present time, soundly conceived research should be pursued in all domains along the lines outlined in this report.

ACS (American Cancer Society). 1993. Cancer Facts and Figures, 1993 . Washington, DC: ACS.

AHA (American Heart Association). 1992. 1993 Heart and Stroke Fact Statistics . Dallas, TX: AHA.

Anglin MD, Hser Y. 1992. Treatment of drug abuse. In: Watson RR, ed. Drug Abuse Treatment. Vol. 3, Drug and Alcohol Abuse Reviews . New York: Humana Press.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA.

Ball JC, Ross A. 1991. The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment . New York: Springer-Verlag.

Batten H, Horgan CM, Prottas J, Simon LJ, Larson MJ, Elliott EA, Bowden ML, Lee M. 1993. Drug Services Research Survey Final Report: Phase I . Contract number 271-90-8319/1. Submitted to the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Waltham, MA: Bigel Institute for Health Policy, Brandeis University.

Brewley T. 1995. Conversation with Thomas Brewley. Addiction 90:883-892.

Carr DB, Jacox AK, Chapman CR, et al. 1992. Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma. Clinical Practice Guidelines . AHCPR Publication No. 92-0032. Rockville, MD: U.S. Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1995. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 7(2).

Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH. 1991. The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology . 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Daley DC, Marlatt GA. 1992. Relapse prevention: Cognitive and behavioral interventions. In: Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, Langrod JG, eds. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook . Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

D'Aunno T, Vaughn TE. 1992. Variation in methadone treatment practices. Journal of the American Medical Association 267:253-258.

DiGregorio GJ. 1990. Cocaine update: Abuse and therapy. American Family Physician 41(1):247-250.

Foley KM, Inturrisi CE, eds. 1986. Opioid Analgesics in the Management of Clinical Pain. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. Vol. 8. New York: Raven Press.

GAO (General Accounting Office). 1992. Drug Abuse Research: Federal Funding and Future Needs . GAO/PEMD-92-5. Washington, DC: GAO.

Glassman AH, Covey LS, Dalack GW, Stetner F, Rivelli SK, Fleiss J, Cooper TB. 1993. Smoking cessation, clonidine, and vulnerability to nicotine among dependent smokers. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 54(6):670-679.

Goldstein A. 1994. Addiction: From Biology to Drug Policy . New York: W.H. Freeman.

Hokfelt TGM, Castel MN, Morino P, Zhang X, Dagerlind A. 1995. General overview of neuropeptides. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, eds. Psychopharmacology: Fourth Generation of Progress . New York: Raven Press. Pp. 483-492.

Holmberg SD. 1996 . The estimated prevalence and incidence of HIV in 96 large U.S. metropolitan areas . American Journal of Public Health 86(5):642-654.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1990. Treating Drug Problems . Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. AIDS and Behavior: An Integrated Approach . Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1995. The Development of Medications for the Treatment of Opiate and Cocaine Addictions. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R, et al. 1994. Management of Cancer Pain. Clinical Practice Guideline . AHCPR Publication No. 94-0592. Rockville, MD: U.S. Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

Kahn RS, Davis KL. 1995. New developments in dopamine and schizophrenia. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, eds. Psychopharmacology: Fourth Generation of Progress . New York: Raven Press. Pp. 1193-1204.

McDuff DR, Schwartz RP, Tommasello A, Tiegel S, Donovan T, Johnson JL. 1993. Outpatient benzodiazepine detoxification procedure for methadone patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 10:297-302.

McLellan AT, Metzger DS, Alterman Al, Woody GE, Durell J, O'Brien CP. In press. Is addiction treatment "worth it"? Public health expectations, policy-based comparisons. Milbank Quarterly .

Meyer R. 1996. The disease called addiction: Emerging evidence in a 200-year debate. Lancet 347:162-166.

Miller NS. 1991. Drug and alcohol addiction as a disease. In: Miller NS, ed. Comprehensive Handbook of Drug and Alcohol Addiction . New York: Marcel Dekker.

MMWR (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report). 1994. Medical care expenditures attributable to cigarette smoking, United States, 1993. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 43(26):469-472.

NRC (National Research Council). 1995. Preventing HIV Transmission: The Role of Sterile Needles and Bleach . Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

O'Brien CP, McLellan AT. 1996. Myths about the treatment of addiction. Lancet 347:237-240.

Olson GA, Olson RD, Kastin AJ. 1994. Endogenous opiates, 1993. Peptides 15:1513-1556.

ONDCP (Office of National Drug Control Policy). 1996. National Drug Control Strategy . Washington, DC: ONDCP.

Pentz M. 1994. Directions for future research in drug abuse prevention. Preventive Medicine 23:646-652.

Rhodes W, Scheiman P, Pittayathikhun T, Collins L, Tsarfaty V. 1995. What America's Users Spend on Illegal Drugs, 1988-1993 . Prepared for the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Washington, DC.

Rice DP, Kelman S, Miller LS, Dunmeyer S. 1990. The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1985 . DHHS Publication No. (ADM) 90-1694. San Francisco: University of California, Institute for Health and Aging.

Rice DP, Max W, Novotny T, Shultz J, Hodgson T. 1992. The Cost of Smoking Revisited: Preliminary Estimates . Paper presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, November 23, 1992. Washington, DC.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 1993. Improving Treatment for Drug-Exposed Infants: Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 1995. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1994 . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Schelling TC. 1992 . Addictive drugs: The cigarette experience. Science 255:431-433.

Tonry M. 1990. Research on drugs and crime. In: Morris N, Tonry M, eds. Drugs and Crime . Vol. 13 . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Schlyer DJ, Dewey SI, Wolf AD. 1993. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse 14:169-177.

Wall PD, Melzack R. 1994. Textbook of Pain . 3rd ed. Edinburg: Churchill-Livingstone.

WHO (World Health Organization). 1992. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems . Tenth Revision. Geneva: WHO.

Drug abuse persists as one of the most costly and contentious problems on the nation's agenda. Pathways of Addiction meets the need for a clear and thoughtful national research agenda that will yield the greatest benefit from today's limited resources.

The committee makes its recommendations within the public health framework and incorporates diverse fields of inquiry and a range of policy positions. It examines both the demand and supply aspects of drug abuse.

Pathways of Addiction offers a fact-filled, highly readable examination of drug abuse issues in the United States, describing findings and outlining research needs in the areas of behavioral and neurobiological foundations of drug abuse. The book covers the epidemiology and etiology of drug abuse and discusses several of its most troubling health and social consequences, including HIV, violence, and harm to children.

Pathways of Addiction looks at the efficacy of different prevention interventions and the many advances that have been made in treatment research in the past 20 years. The book also examines drug treatment in the criminal justice setting and the effectiveness of drug treatment under managed care.

The committee advocates systematic study of the laws by which the nation attempts to control drug use and identifies the research questions most germane to public policy. Pathways of Addiction provides a strategic outline for wise investment of the nation's research resources in drug abuse. This comprehensive and accessible volume will have widespread relevance—to policymakers, researchers, research administrators, foundation decisionmakers, healthcare professionals, faculty and students, and concerned individuals.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- June 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 6 CURRENT ISSUE pp.461-564

- May 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 5 pp.347-460

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

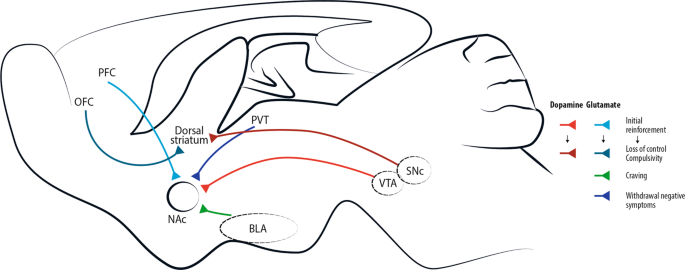

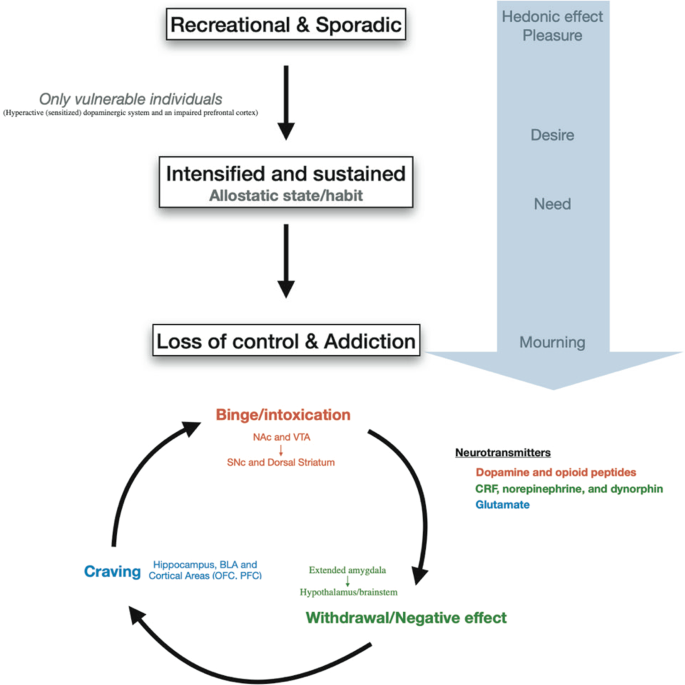

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions