Verify originality of an essay

Get ideas for your paper

Find top study documents

How to write a discursive essay: step-by-step guideline

Updated 17 Apr 2024

Many students struggle with discursive writing as it can be tricky. It’s hard to manage different opinions and create a well-organized argument, leaving learners feeling unsure. In this article, we want to make creating discursive essays less confusing by giving helpful tips. If you grasp the essential information and follow our advice, you can tackle the challenges of this essay style and learn how to express convincing and well-thought-out ideas. Come with us as we explore the basic dos and don’ts for making successful writing.

What is a discursive essay?

This type of academic writing explores and presents various perspectives on a particular topic or issue. Unlike an argumentative essay, where the author takes a clear stance on the subject, discursive writing aims to provide a balanced and nuanced discussion of different viewpoints. What is the discursive essay meaning? The first word implies a conversation or discussion. So, the text encourages an exploration of diverse opinions and arguments.

This homework, commonly assigned in higher academia, serves various purposes:

- Students analyze diverse perspectives, fostering critical thinking as they weigh different viewpoints before forming a conclusion.

- Such essays involve thorough research, requiring students to synthesize information from various sources and present a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

- When struggling with how to write my essay for me , students develop their communication skills as they should express complex ideas clearly and coherently, creating smooth transitions between arguments.

- While not demanding a fixed stance, discursive papers require persuasive writing skills. The authors present each perspective convincingly, regardless of personal endorsement.

- Encouraging an appreciation for the issue’s complexity, the essays promote tolerance for diverse opinions.

In summary, these papers contribute to developing analytical, research, and communication skills, preparing students for nuanced engagement with complex topics in academic and professional settings.

What is the difference between discursive and argumentative essays?

While these documents may exhibit certain similarities, it’s crucial to underscore the notable distinctions that characterize them, delineating their unique objectives and methodologies.

Discursive essays

- Objective presentation: A five paragraph essay of this type aims to provide a comprehensive discussion on a particular topic without necessarily taking a clear stance.

- Multiple perspectives: Writers explore different viewpoints, neutrally presenting arguments and counterarguments.

- Complexity: These essays often deal with complex issues, encouraging a nuanced understanding of the subject.

- Balanced tone and language: Such writing allows for a more open expression of different ideas using objective and formal language.

- Flexible structure: These texts allow for a free-flowing topic analysis and may express numerous ideas in separate sections.

- Conclusion: While a discursive essay example may express the writer's opinion, it doesn’t necessarily require a firm conclusion or a call to action.

Argumentative essays

- Clear stance: This type involves taking a specific position and defending it with strong, persuasive arguments.

- Focused argumentation: The primary goal is to convince the reader of the writer's position, providing compelling evidence and logical reasoning.

- Counterarguments: While an argumentative essay acknowledges opposing views, the focus is on refuting them to strengthen the writer’s position.

- Assertive tone: This type aims to present ideas from the writer’s perspective and convict the reader using evidence and reasoning.

- Rigid structure: These texts come with a clear structure with a distinct introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs with arguments and reasoning, and a conclusion that highlights the author’s stance.

- Call to action or conclusion: Such papers often conclude with a clear summary of the arguments and may include a call to action or a statement of the writer’s position.

The key distinction lies in the intent: discursive texts foster a broader understanding by presenting multiple perspectives. At the same time, argumentative papers aim to persuade the reader to adopt a specific viewpoint through strong, focused arguments.

Save your time! We can take care of your essay

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

Discursive writing types

When delving into discursive essay format, exploring three primary forms of writing is essential.

1. Opinion essay.

- In an opinion essay , your viewpoint on the discussed problem is crucial.

- State your opinion in the introduction, supported by examples and reasons.

- Present the opposing argument before the conclusion, explaining why you find it unconvincing.

- Summarize your important points in the conclusion.

2. Essay providing a solution to a problem.

- Focus on discussing an issue and proposing solutions.

- Introduce the issue at the beginning of the text.

- Detail possible solutions in separate body paragraphs.

- Summarize your opinion in the conclusion.

3. For and against essay.

- Write it as a debate with opposing opinions.

- Describe each viewpoint objectively, presenting facts.

- Set the stage for the problem in your discursive essay intro.

- Explore reasons, examples, and facts in the main body.

- Conclude with your opinion on the matter.

If you need professional writers' support when working on your homework, you may always pay for essay writing . Our experts can explain how to create different types of papers and suggest techniques to make them well-thought-out and compelling.

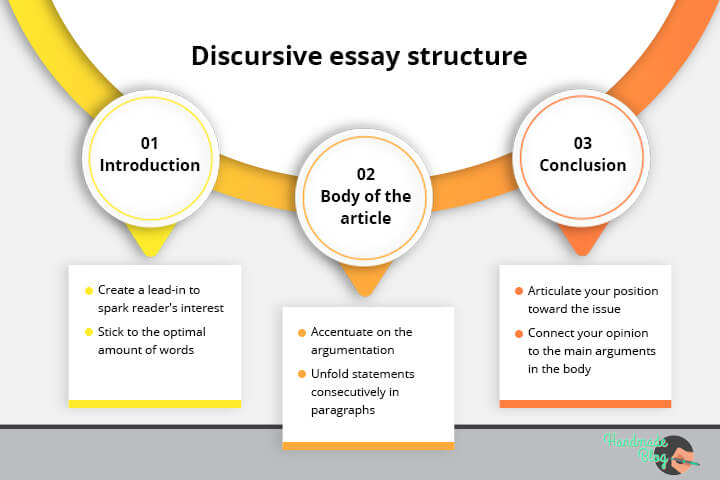

Discursive essay structure

Discover a concise outline that will help structure your thoughts and arguments, allowing for a comprehensive and articulate presentation of your ideas.

|

A. Hook or opening statement B. Background information on the topic C. Thesis statement (indicate the topic and your stance, if applicable)

(number of paragraphs can vary based on essay length) A. Presentation of perspective (1) 1. Statement of perspective (1) 2. Supporting evidence/examples 3. Analysis and discussion

B. Presentation of perspective (2) 1. Statement of perspective (2) 2. Supporting evidence/examples 3. Analysis and discussion

C. Presentation of perspective (3) (if applicable) 1. Statement of perspective (3) 2. Supporting evidence/examples 3. Analysis and discussion

D. Presentation of counterarguments 1. Acknowledge opposing views 2. Refute or counter opposing arguments 3. Provide evidence supporting your perspective

A. Summary of main points B. (if applicable) C. Closing thoughts or call to action (if applicable) |

The length of the discursive introduction example and the number of body paragraphs can vary based on the topic's complexity and the text's required length. Additionally, adjust the outline according to specific assignment guidelines or your personal preferences.

10 steps to create an essay

Many students wonder how to write a discursive essay. With the following guidelines, you can easily complete it as if you were one of the professional essay writers for hire . Look at these effective steps and create your outstanding text.

1. Choose an appropriate topic:

- Select a topic that sparks interest and is debatable. Ensure it is suitable for discursive examples with multiple viewpoints.

2. Brainstorm your ideas:

- Gather information from various sources to understand different perspectives on the chosen topic.

- Take notes on key arguments, evidence, and counterarguments.

3. Develop a clear thesis:

- Formulate a thesis statement that outlines your main idea. This could include your stance on the topic or a commitment to exploring various viewpoints.

4. Create a discursive essay outline:

- Structure your text with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Outline the main points you want to cover in each section.

5. Write the introduction:

- Begin with a hook to grab the reader's attention.

- Provide background information on the topic.

- Clearly state your thesis or the purpose of the essay.

6. Create body paragraphs:

- Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence.

- Present different perspectives on the topic in separate paragraphs.

- Support each perspective with relevant evidence and examples.

- Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each viewpoint.

- Use smooth transitions between paragraphs.

7. Suggest counterarguments:

- Devote a section to acknowledging and addressing counterarguments.

- Refute or explain why you find certain counterarguments unconvincing.

8. Write the conclusion:

- Summarize the main points discussed in the body paragraphs.

- Restate your thesis or the overall purpose of the essay.

- Provide a concise discursive essay conclusion, highlighting the significance of the topic.

9. Proofread and revise:

- Review your work for clarity, coherence, and logical flow.

- Check for grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors.

- Ensure that your arguments are well-supported and effectively presented.

10. Finalize and submit:

- Make any necessary revisions based on feedback or additional insights.

- Ensure every discursive sentence in your paper meets specific requirements provided by your instructor.

- Submit your well-crafted document.

Following these steps will help you produce a well-organized and thought-provoking text that effectively explores and discusses the chosen topic.

Dos and don’ts when completing a discursive essay

If you want more useful writing tips, consider the dos and don’ts to create an impactful and compelling text.

- Thorough research: Do conduct extensive research on the topic to gather a diverse range of perspectives and solid evidence. It will strengthen your discursive thesis statement and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

- Clear structure: Do organize your essay with a clear introduction, body paragraphs that present different viewpoints, and a concise conclusion. Use a separate paragraph to introduce every point. This structure helps readers follow your argument effectively.

- Neutral tone: Do maintain a balanced tone and impersonal style throughout the essay. Avoid being overly emotional or biased, as the goal is to present a fair discussion of various perspectives.

- Critical analysis: Do critically analyze each perspective, highlighting strengths and weaknesses. Build your discursive thesis on trustworthy sources and make appropriate references following the rules of the required citation style. This showcases your critical thinking ability and contributes to a more nuanced discussion.

- Smooth transitions: Do use smooth transitions between paragraphs and arguments to create a cohesive flow. The use of linking phrases and words enhances the readability of your text and makes it easier for the reader to follow your line of reasoning.

Don’ts:

- Avoid biased language: Don’t use biased language or favor one perspective over another. Maintain an objective tone and present each viewpoint with equal consideration.

- Don’t oversimplify: Avoid oversimplifying complex issues. Acknowledge the nuances of the topic and provide a nuanced discussion that reflects a deep understanding of the subject matter.

- Steer clear of generalizations: Don’t make broad generalizations without supporting evidence. Ensure that relevant and credible sources back your arguments to strengthen your position.

- Don’t neglect counterarguments: Avoid neglecting counterarguments. Acknowledge opposing views and address them within your discursive essays. It adds credibility to your work and thoroughly examines the topic.

- Don’t be too personal : Avoid expressing your personal opinion too persistently, and don’t use examples from your individual experience.

- Refrain from unsupported claims: Don’t make claims without supporting them with evidence. Substantiate your arguments with reliable sources and statistics with proper referencing to enhance the credibility of your document.

By adhering to these dos and don’ts, you’ll be better equipped to navigate the complexities of writing a discursive text and present a well-rounded and convincing discussion.

Final thoughts

Mastering the art of writing a discursive essay is a valuable skill that equips students with critical thinking, research, and communication abilities. If your essay-writing journey is challenging, consider seeking assistance from EduBirdie, a trusted companion that guides students through the intricacies of these papers and helps them answer the question, “What is discursive writing?”. With our support, you can navigate the challenges of crafting a compelling and well-rounded discourse, ensuring success in your academic endeavors. Embrace the assistance of EduBirdie and elevate your writing experience to new heights.

Was this helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Written by Steven Robinson

Steven Robinson is an academic writing expert with a degree in English literature. His expertise, patient approach, and support empower students to express ideas clearly. On EduBirdie's blog, he provides valuable writing guides on essays, research papers, and other intriguing topics. Enjoys chess in free time.

Related Blog Posts

Diversity essay: effective tips for expressing ideas.

In today's interconnected and rapidly evolving world, the importance of diversity in all its forms cannot be overstated. From classrooms to workpla...

Learn how to write a deductive essay that makes you proud!

Learning how to write a deductive essay may sound like a challenging task. Yet, things become much easier when you master the definition and the ob...

Learn how to write an extended essay correctly

This helpful article will provide all the necessary information to show you how to write an extended essay without mistakes. You will learn about a...

Join our 150K of happy users

- Get original papers written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

- Business Intelligence Assignment Help

- Lab Report Writing Service

- Nursing Assignment Help

- Buy Response Essay

- CPM Homework Answers

- Do My Chemistry Homework

- Buy Argumentative Essay

- Do Your Homework

- Biology Essay Writers

- Business Development Assignment Help

- Best Macroeconomics Assignment Help

- Best Financial Accounting Assignment Help

- PHP Assignment Help

- Science Assignment Help

- Audit Assignment Help

- Perdisco Accounting Assignment Help

- Humanities Assignment Help

- Computer Network Assignment Help

- Arts and Architecture Assignment Help

- How it works

How to Write a Discursive Essay: Tips, Examples, and Structure

Calculate the price of your order:.

Mastering the Art of Writing a Discursive Essay

Table of contents.

Introduction

Understanding Discursive Essays

Discursive essay writing tips, discursive essay structure, examples of discursive essays, picking the right discursive essay topics, discursive essay format, crafting a strong discursive essay outline, writing an effective discursive essay introduction, nailing the discursive essay conclusion.

Welcome to our comprehensive guide on how to write a discursive essay effectively. If you’re unfamiliar with this type of essay or want to improve your skills, you’ve come to the right place! This guide will cover How to Write a Discursive Essay , examples, and strategies to help you craft a compelling discursive essay.

Are you ready to master this art of writing ? This article will explain a discursive essay and explore various aspects such as writing tips, structure, examples, and format. So, let’s dive right in and unveil the key elements of an impressive discursive essay.

Before we delve into the nitty-gritty of writing a discursive essay , let’s take a moment to understand its nature and purpose. A discursive essay presents a balanced argument on a particular topic by exploring different perspectives. It requires the writer to consider different viewpoints, present evidence, and critically analyze the subject matter.

Writing a discursive essay can be challenging, but you can excel in this art form with the right approach. Here are some valuable tips that will help you write a discursive essay effectively:

- Choose an Engaging Topic: Select a topic that is interesting and relevant to your audience. This will make the essay more engaging and enjoyable to read.

- Thorough Research: Gather extensive information from reliable sources to support your arguments and counterarguments.

- Plan and Outline: Take the time to plan and create an outline before diving into the writing process. This will help you organize your thoughts and arguments effectively.

- Clear Introduction: Start with a concise introduction that provides context and grabs the reader’s attention. Clearly state your thesis or main argument.

- Well-structured Paragraphs: Divide your essay into paragraphs that focus on specific points. Each paragraph should present a new idea or support a previous one.

- Logical Flow: Maintain a logical flow using transitional words and phrases that connect your ideas and paragraphs smoothly.

- Balance Your Arguments: Ensure a balance in presenting the pros and cons of each perspective. This will demonstrate your fairness and critical thinking skills.

- Support with Evidence: Provide evidence, facts, and examples to support your claims and make your arguments more persuasive.

- Use Clear Language: Avoid jargon and overly complex language. Opt for clear, concise, and precise language that is easy for readers to comprehend.

- Proofread and Edit: Always revise, proofread, and edit your essay to ensure clarity, coherence, and proper grammar usage.

Following these tips, you’ll be well-equipped to write an impressive discursive essay that effectively presents your arguments and engages your readers.

A well-structured discursive essay enhances readability and ensures that your arguments are coherent. Here’s a suggested structure that you can follow:

- Hook the reader with an attention-grabbing statement or anecdote.

- Introduce the topic and provide background information.

- Present your thesis statement or main argument.

- Start each paragraph with a topic sentence introducing a new argument or perspective.

- Provide evidence, examples, and supporting details to justify your claims.

- Address counterarguments and present rebuttals, showing your ability to consider different viewpoints.

- Use transitional words to maintain a smooth flow between paragraphs.

- Summarize the main points discussed in the essay.

- Restate your thesis statement while considering the arguments presented.

- End with a thought-provoking statement or call to action.

By adhering to this structure, your discursive essay will be well-organized and easy for readers to follow.

To gain a better understanding of how discursive essays are written, let’s explore a couple of examples:

Example 1: The Impact of Social Media

Introduction: The growing influence of social media in society.

Main Body: Discussing the positive and negative aspects of social media on communication, mental health, privacy, and relationships.

Conclusion: Weighing the overall impact of social media and proposing ways to harness its strengths and mitigate its drawbacks.

Example 2: The Pros and Cons of School Uniforms

Introduction: Introducing the debate on school uniforms.

Main Body: Exploring the arguments supporting school uniforms (such as fostering discipline and equality) and arguments against them (such as limiting self-expression).

Conclusion: Evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of school uniforms and suggesting potential compromises.

These examples illustrate how discursive essays analyze various perspectives on a topic while maintaining a balanced approach.

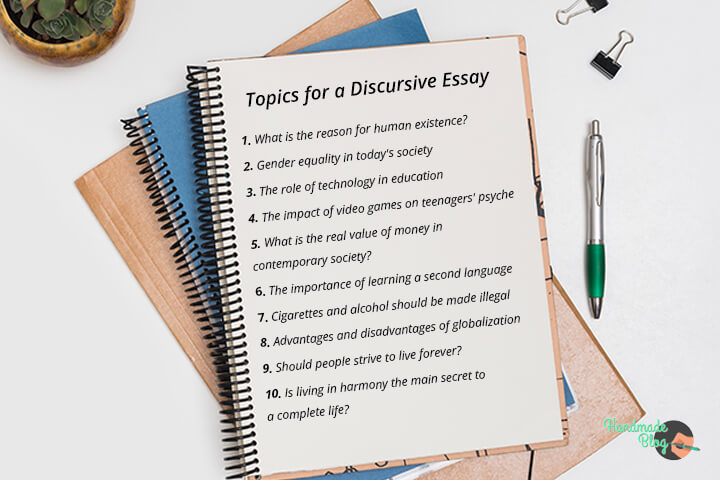

Choosing an engaging and relevant topic is crucial to capturing your readers’ attention. Here are some popular discursive essay topics to consider:

- Is social media beneficial or detrimental to society?

- Should the death penalty be abolished worldwide?

- Are genetically modified organisms (GMOs) safe for consumption?

- Should recreational marijuana use be legalized?

- Are video games responsible for the rise in violence among youth?

When selecting a topic, ensure it is captivating, allows for multiple viewpoints, and is backed by sufficient research material.

While there is flexibility in formatting a discursive essay, adhering to a standard format enhances clarity and readability. Consider following this general format:

- Font type and size: Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri with a 12-point font size.

- Line spacing: Double-spaced throughout the essay.

- Page margins: 1-inch margins on all sides.

- Title page: Include the essay title, your name, course name, instructor’s name, and submission date (if applicable).

- Header: Insert a header with your last name and page number (top-right corner).

A consistent format will make your essay more professional and easier to navigate.

Before writing your discursive essay, creating an outline that organizes your thoughts and arguments effectively is essential. Here’s a sample outline to help you get started:

I. Introduction

B. Background information

C. Thesis statement

II. Main Body

A. Argument 1

1. Supporting evidence

2. Examples

B. Argument 2

C. Argument 3

1 . Supporting evidence

2 . Examples

III. Counterarguments and Rebuttals

A. Counterargument 1

1 . Rebuttal evidence

B. Counterargument 2

C . Counterargument 3

IV. Conclusion

A. Summary of main points

B . Restating the thesis statement

C. Call to action or thought-provoking statement

By structuring your ideas in an outline, you’ll have a clear roadmap for your essay, ensuring that your arguments flow logically.

The introduction of your discursive essay plays a vital role in capturing your reader’s attention and setting the tone for the essay. Here’s how you can make your introduction compelling:

Start With an Engaging Hook: Begin with a captivating opening sentence, such as a surprising statistic, an intriguing question, or a compelling anecdote related to your topic.

Provide Necessary Background Information: Briefly explain the topic and its relevance to the reader.

Present Your Thesis Statement: Clearly state your main argument or thesis, which will guide your essay’s direction and focus.

You’ll establish a strong foundation for your discursive essay by crafting an engaging and informative introduction.

The conclusion of your discursive essay should effectively summarize your main points and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s how you can achieve this:

Summarize the Main Points: Briefly recap the key arguments and perspectives discussed in the essay.

Restate Your Thesis Statement: Reiterate your main argument while considering the various perspectives.

Call to Action or Thought-Provoking Statement: End your essay with a compelling statement or encourage readers to explore the topic further, sparking discussion and reflection.

By crafting a powerful conclusion, you’ll leave a lasting impact on your readers, ensuring they walk away with a clear understanding of your essay’s message.

Congratulations! You’ve now comprehensively understood how to write a discursive essay effectively. Remember to choose an engaging topic, conduct thorough research, create a clear structure, and present balanced arguments while considering different perspectives. Following these guidelines and incorporating our tips, you’ll be well-equipped to craft a compelling discursive essay.

So, start writing your discursive essay following our comprehensive guide. Unlock your writing potential and captivate your readers with an impressive discursive essay that showcases your analytical skills and ability to present compelling arguments. Happy writing!

Frequently Asked Questions About “How to Write a Discursive Essay Effectively”

What is a discursive essay, and how does it differ from other types of essays.

A discursive essay explores a particular topic by presenting different perspectives and arguments. It differs from other essays, emphasizing balanced, unbiased discussion rather than a single, strong stance.

How should I choose a topic for my discursive essay?

Select a topic that allows for multiple viewpoints and has room for discussion. Controversial issues or topics with various opinions work well, providing ample material for exploration.

What is the typical structure of a discursive essay?

A discursive essay typically has an introduction, several body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction sets the stage, the body paragraphs present different viewpoints, and the conclusion summarizes the key points and your stance.

Is it necessary to choose a side in a discursive essay?

While you don’t have to take a definite side, you should present a balanced view. However, some essay prompts may ask you to argue for or against a particular position.

How do I start the introduction of a discursive essay?

Begin with a hook to capture the reader’s attention, provide background information, and clearly state the issue you will discuss. End the introduction with a thesis statement that outlines your approach.

Should I use formal language in a discursive essay?

Yes, maintain a formal and objective tone. Avoid using first-person pronouns and aim for clarity and precision in your language.

How many viewpoints should I include in the body paragraphs?

Include at least two or three well-developed viewpoints. Ensure that each paragraph focuses on a specific aspect or argument related to the topic.

How do I transition between paragraphs in a discursive essay?

Use transitional phrases to move smoothly from one idea to the next. This helps maintain a logical flow and coherence in your essay.

Can I include personal opinions in a discursive essay?

While you can present your opinions, remaining objective and supporting your views with evidence is crucial. The emphasis should be on presenting a well-rounded discussion rather than expressing personal bias.

How do I conclude a discursive essay effectively?

Summarize the main points discussed in the body paragraphs, restate your thesis nuancedly, and offer a closing thought or call to action. Avoid introducing new information in the conclusion.

Basic features

- Free title page and bibliography

- Unlimited revisions

- Plagiarism-free guarantee

- Money-back guarantee

- 24/7 support

On-demand options

- Writer's samples

- Part-by-part delivery

- Overnight delivery

- Copies of used sources

- Expert Proofreading

Paper format

- 275 words per page

- 12 pt Arial/Times New Roman

- Double line spacing

- Any citation style (APA, MLA, CHicago/Turabian, Havard)

Guaranteed originality

We guarantee 0% plagiarism! Our orders are custom made from scratch. Our team is dedicated to providing you academic papers with zero traces of plagiarism.

Affordable prices

We know how hard it is to pay the bills while being in college, which is why our rates are extremely affordable and within your budget. You will not find any other company that provides the same quality of work for such affordable prices.

Best experts

Our writer are the crème de la crème of the essay writing industry. They are highly qualified in their field of expertise and have extensive experience when it comes to research papers, term essays or any other academic assignment that you may be given!

Calculate the price of your order

Expert paper writers are just a few clicks away

Place an order in 3 easy steps. Takes less than 5 mins.

How to Write a Discursive Essay: Awesome Guide and Template

Interesting fact: Did you know that the term "discursive" is derived from the Latin word "discursus," which means to run about or to traverse? This reflects the nature of a discursive essay, as it involves exploring various perspectives, moving through different points of view, and presenting a comprehensive discussion on a given topic.

In this article, you will find out about a discursive essay definition, learn the difference between a discourse and an argumentative essay, gain practical how-to tips, and check out a discursive essay example.

What Is a Discursive Essay

A discursive essay definition is a type of formal writing that presents a balanced analysis of a particular topic. Unlike an argumentative essay, which takes a firm stance on a single perspective and seeks to persuade the reader to adopt that viewpoint, a discursive essay explores multiple sides of an issue.

The goal of a discursive essay is to provide a comprehensive overview of the subject, presenting different arguments, counterarguments, and perspectives in a structured and organized manner.

This type of essay encourages critical thinking and reasoned discourse. It typically includes an introduction that outlines the topic and sets the stage for the discussion, followed by a series of body paragraphs that delve into various aspects of the issue. The essay may also address counterarguments and opposing viewpoints.

Finally, a discursive essay concludes by summarizing the key points and often leaves room for the reader to form their own informed opinion on the matter. This form of writing is commonly assigned in academic settings, allowing students to demonstrate their ability to analyze complex topics and present a well-reasoned exploration of diverse viewpoints. In case you find this type of composition too difficult, just say, ‘ write my paper ,’ and professional writers will take care of it.

Ready to Transform Your Essays?

From discursive writing to academic triumphs, let your words soar with our essay writing service!

Difference Between a Discursive Essay and an Argumentative

The main difference between discursive essays and argumentative lies in their overall purpose and approach to presenting information.

- Discursive: The primary purpose of a discursive essay is to explore and discuss various perspectives on a given topic. How to write a discursive essay is about providing a comprehensive overview of the subject matter by presenting different arguments, opinions, and viewpoints without necessarily advocating for a specific stance.

- Argumentative: In contrast, an argumentative essay is designed to persuade the reader to adopt a particular viewpoint or take a specific action. It presents a clear and focused argument in favor of the writer's position, often addressing and refuting opposing views.

Tone and Language:

- Discursive: The tone of a discursive essay is generally more balanced and objective. It allows for a more open exploration of ideas, and the language used is often neutral and formal.

- Argumentative: An argumentative essay tends to have a more assertive tone. The language is focused on presenting a compelling case from the writer's perspective, and there may be a sense of conviction in the presentation of evidence and reasoning.

- Discursive Essay: A discursive essay typically follows a more flexible structure. It may present multiple points of view in separate sections, allowing for a free-flowing exploration of the topic.

- Argumentative Essay: When learning how to write an argumentative essay, students usually follow a more rigid structure, with a clear introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs that present evidence and arguments, and a conclusion that reinforces the writer's stance.

Conclusion:

- Discursive Essay: The conclusion of a discursive essay often summarizes the main points discussed and may leave room for the reader to form their own opinion on the matter.

- Argumentative Essay: The conclusion of an argumentative essay reinforces the writer's position and may include a call to action or a clear statement of the desired outcome.

While both types of essays involve critical thinking and analysis, the key distinction lies in their ultimate goals and how they approach the presentation of information.

Types of Discursive Essay

Before writing a discursive essay, keep in mind that they can be categorized into different types based on their specific purposes and structures. Here are some common types of discursive essays:

.webp)

Opinion Essays:

- Purpose: Expressing and supporting personal opinions on a given topic.

- Structure: The essay presents the writer's viewpoint and provides supporting evidence, examples, and arguments. It may also address counterarguments to strengthen the overall discussion.

Problem-Solution Essays:

- Purpose: Identifying a specific problem and proposing effective solutions.

- Structure: The essay introduces the problem, discusses its causes and effects, and presents possible solutions. It often concludes with a recommendation or call to action.

Compare and Contrast Essays:

- Purpose: Analyzing similarities and differences between two or more perspectives, ideas, or approaches.

- Structure: The essay outlines the key points of each perspective, highlighting similarities and differences. A balanced analysis is provided to give the reader a comprehensive understanding.

Cause and Effect Essays:

- Purpose: Exploring the causes and effects of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Structure: The essay identifies the primary causes and examines their effects or vice versa. It may delve into the chain of events and their implications.

Argumentative Essays:

- Purpose: Presenting a strong argument in favor of a specific viewpoint.

- Structure: The essay establishes a clear thesis statement, provides evidence and reasoning to support the argument, and addresses opposing views. It aims to persuade the reader to adopt the writer's perspective.

Pro-Con Essays:

- Purpose: Evaluating the pros and cons of a given issue.

- Structure: The essay presents the positive aspects (pros) and negative aspects (cons) of the topic. It aims to provide a balanced assessment and may conclude with a recommendation or a summary of the most compelling points.

Exploratory Essays:

- Purpose: Investigating and discussing a topic without necessarily advocating for a specific position.

- Structure: The essay explores various aspects of the topic, presenting different perspectives and allowing the reader to form their own conclusions. It often reflects a process of inquiry and discovery.

These types of discursive essays offer different approaches to presenting information, and the choice of type depends on the specific goals of the essay and the preferences of the writer.

How to Write a Discursive Essay

Unlike other forms of essay writing, a discursive essay demands a unique set of skills, inviting writers to navigate through diverse perspectives, present contrasting viewpoints, and weave a tapestry of balanced arguments.

You can order custom essay right now to save time to get ready to delve into the art of crafting a compelling discursive essay, unraveling the intricacies of structure, language, and critical analysis. Whether you're a seasoned essayist or a novice in the realm of formal writing, this exploration promises to equip you with the tools needed to articulate your thoughts effectively and engage your audience in thoughtful discourse.

.webp)

Discursive Essay Format

The format of a discursive essay plays a crucial role in ensuring a clear, well-organized, and persuasive presentation of multiple perspectives on a given topic. Here is a typical discursive essay structure:

1. Introduction:

- Hook: Begin with a captivating hook or attention-grabbing statement to engage the reader's interest.

- Contextualization: Provide a brief overview of the topic and its relevance, setting the stage for the discussion.

- Thesis Statement: Clearly state the main argument or the purpose of the essay. In a discursive essay, the thesis often reflects the idea that the essay will explore multiple viewpoints without necessarily taking a firm stance.

2. Body Paragraphs:

- Topic Sentences: Start each body paragraph with a clear topic sentence that introduces the main point or argument.

- Presentation of Arguments: Devote individual paragraphs to different aspects of the topic, presenting various arguments, perspectives, or evidence. Ensure a logical flow between paragraphs.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen the overall credibility of your essay.

- Supporting Evidence: Provide examples, statistics, quotations, or other forms of evidence to bolster each argument.

3. Transitions:

- Logical Transitions: Use transitional phrases and words to ensure a smooth and logical flow between paragraphs and ideas. This helps readers follow your line of reasoning.

4. Conclusion:

- Restate Thesis: Summarize the main argument or purpose of the essay without introducing new information.

- Brief Recap: Provide a concise recap of the key points discussed in the body paragraphs.

- Closing Thoughts: Offer some closing thoughts or reflections on the significance of the topic. You may also leave room for the reader to consider their own stance.

5. Language and Style:

- Formal Tone: Maintain a formal and objective tone throughout the essay.

- Clarity and Coherence: Ensure that your ideas are presented clearly and that there is coherence in your argumentation.

- Varied Sentence Structure: Use a variety of sentence structures to enhance readability and engagement.

6. References (if applicable):

- Citations: If you use external sources, cite them appropriately according to the citation style required (e.g., APA, MLA).

Remember, flexibility exists within this format, and the specifics may vary based on the assignment requirements or personal writing preferences. Tailor the structure to suit the demands of your discourse and the expectations of your audience.

Introduction

A discursive essay introduction serves as the gateway to a thought-provoking exploration of diverse perspectives on a given topic. Here's how to structure an effective discursive essay introduction:

- Begin with a compelling hook that captures the reader's attention. This could be a striking statistic, a thought-provoking quote, a relevant anecdote, or a rhetorical question.

- Offer a brief context or background information about the topic. This helps orient the reader and sets the stage for the discussion to follow.

- Clearly state the purpose of the essay. This often involves indicating that the essay will explore various perspectives on the topic without necessarily advocating for a specific stance.

- Provide a brief overview of the different aspects or arguments that will be explored in the essay.

- Conclude the introduction with a clear and concise thesis statement.

Remember that besides writing compositions, you still have to do math homework , which is something we can help you with right now!

Writing a discursive essay involves crafting the body of your discursive essay. The number of paragraphs in the body should correspond to the arguments presented, with an additional paragraph dedicated to the opposing viewpoint if you choose to disclose both sides of the argument. If you opt for this approach, alternate the order of the body paragraphs—supporting arguments followed by counterarguments.

Each body paragraph in your discursive essay should focus on a distinct idea. Begin the paragraph with the main idea, provide a concise summary of the argument, and incorporate supporting evidence from reputable sources.

In the concluding paragraph of the body, present potential opposing arguments and counter them. Approach this section as if engaging in a debate, strategically dismantling opposing viewpoints.

While composing the body of a discursive essay, maintain a cohesive narrative. Although individual paragraphs address different arguments, refrain from titling each paragraph—aim for a seamless flow throughout the essay. Express your personal opinions exclusively in the conclusion.

Key guidelines for writing the body of a discursive essay:

- Remain Unbiased: Prioritize objectivity. Evaluate all facets of the issue, leaving personal sentiments aside.

- Build Your Argumentation: If you have multiple arguments supporting your viewpoint, present them in separate, well-structured paragraphs. Provide supporting evidence to enhance clarity and credibility.

- Use an Alternate Writing Style: Present opposing viewpoints in an alternating manner. This means that if the first paragraph supports the main argument, the second should present an opposing perspective. This method enhances clarity and research depth and ensures neutrality.

- Include Topic Sentences and Evidence: Commence each paragraph with a topic sentence summarizing the argument. This aids reader comprehension. Substantiate your claims with evidence, reinforcing the credibility of your discourse.

By adhering to these principles, you can construct a coherent and well-supported body for your discursive essay.

Conclusion

Writing an effective conclusion is crucial to leaving a lasting impression on your reader. Here are some tips to guide you in crafting a compelling and impactful conclusion:

- Begin your conclusion by summarizing the key points discussed in the body of the essay.

- Remind the reader of your thesis statement, emphasizing the primary purpose of your discursive essay.

- Address the broader significance or implications of the topic.

- Explain why the issue is relevant and underscore the importance of considering multiple perspectives in understanding its complexity.

- Reiterate the balanced nature of your essay. Emphasize that you have explored various viewpoints and arguments without necessarily taking a firm stance.

- Reinforce the idea that your goal was to present a comprehensive analysis.

- If applicable, suggest possible recommendations or solutions based on the insights gained from the essay.

- Encourage the reader to reflect on the topic independently.

- Pose open-ended questions or invite them to consider the implications of the arguments presented.

- Resist the temptation to introduce new information or arguments in the conclusion.

- Keep the tone of your conclusion professional and thoughtful.

- Conclude your essay with a strong, memorable closing statement.

- Carefully review your conclusion to ensure clarity and coherence. Edit for grammar, punctuation, and overall writing quality to present a polished final product.

By incorporating these tips into your discursive essay conclusion, you can effectively summarize your arguments, leave a lasting impression, and prompt thoughtful reflection from your readers. Consider using our term paper writing service if you have to deal with a larger assignment that requires more time and effort.

Yays and Nays of Writing Discourse Essays

In learning how to write a discursive essay, certain do's and don'ts serve as guiding principles throughout the writing process. By adhering to these guidelines, writers can navigate the complexities of presenting arguments, counterarguments, and nuanced analyses, ensuring the essay resonates with clarity and persuasiveness.

- Conduct thorough research on the topic to ensure a well-informed discussion.

- Present multiple perspectives on the issue, exploring various arguments and viewpoints.

- Maintain a balanced and neutral tone. Present arguments objectively without expressing personal bias.

- Structure your essay logically with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. Use paragraphs to organize your ideas effectively.

- Topic Sentences:

- Include clear topic sentences at the beginning of each paragraph to guide the reader through your arguments.

- Support your arguments with credible evidence from reputable sources to enhance the credibility of your essay.

- Use transitional words and phrases to ensure a smooth flow between paragraphs and ideas.

- Engage in critical analysis. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different arguments and viewpoints.

- Recap key points in the conclusion, summarizing the main arguments and perspectives discussed in the essay.

- Carefully proofread your essay to correct any grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors.

- Don't express personal opinions in the body of the essay. Save personal commentary for the conclusion.

- Don't introduce new information or arguments in the conclusion. This section should summarize and reflect on existing content.

- Don't use overly emotional or subjective language. Maintain a professional and objective tone throughout.

- Don't rely on personal opinions without sufficient research. Ensure that your arguments are supported by credible evidence.

- Don't have an ambiguous or unclear thesis statement. Clearly state the purpose of your essay in the introduction.

- Don't ignore counterarguments. Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen your overall argument.

- Don't use overly complex language if it doesn't add to the clarity of your arguments. Strive for clarity and simplicity in your writing.

- Don't present ideas in a disorganized manner. Ensure that there is a logical flow between paragraphs and ideas.

- Don't excessively repeat the same points. Present a variety of arguments and perspectives to keep the essay engaging.

- Don't ignore the guidelines provided for the essay assignment. Follow any specific instructions or requirements given by your instructor or institution.

Feeling exhausted and overwhelmed with all this new information? Don't worry! Buy an essay paper of any type that will be prepared for you individually based on all your instructions.

Discursive Essay Examples

Discursive essay topics.

Writing a discursive essay on a compelling topic holds immense importance as it allows individuals to engage in a nuanced exploration of diverse perspectives. A well-chosen subject encourages critical thinking and deepens one's understanding of complex issues, fostering intellectual growth.

The process of exploring a good topic enhances research skills as writers delve into varied viewpoints and gather evidence to support their arguments. Moreover, such essays contribute to the broader academic discourse, encouraging readers to contemplate different facets of a subject and form informed opinions.

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment.

- Should Social Media Platforms Regulate Content for Misinformation?

- Exploring the Ethics of Cloning in Contemporary Science.

- Universal Basic Income: A Solution for Economic Inequality?

- The Role of Technology in Shaping Modern Education.

- Nuclear Energy: Sustainable Solution or Environmental Risk?

- The Effects of Video Games on Adolescent Behavior.

- Cybersecurity Threats in the Digital Age: Balancing Privacy and Security.

- Debunking Common Myths Surrounding Climate Change.

- The Pros and Cons of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs).

- Online Education vs. Traditional Classroom Learning.

- The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Behavior.

- The Ethics of Animal Testing in Medical Research.

- Universal Healthcare: Addressing Gaps in Healthcare Systems.

- The Role of Government in Regulating Cryptocurrencies.

- The Influence of Advertising on Body Image and Self-Esteem.

- Renewable Energy Sources: A Viable Alternative to Fossil Fuels?

- The Implications of Space Exploration on Earth's Resources.

- Is Censorship Justified in the Arts and Entertainment Industry?

- Examining the Impact of Globalization on Cultural Identity.

- The Morality of Capital Punishment in the 21st Century.

- Should Genetic Engineering be Used for Human Enhancement?

- Social Media and Its Influence on Political Discourse.

- Balancing Environmental Conservation with Economic Development.

- The Role of Gender in the Workplace: Achieving Equality.

- Exploring the Impact of Fast Fashion on the Environment.

- The Benefits and Risks of Autonomous Vehicles.

- The Influence of Media on Perceptions of Beauty.

- Legalization of Marijuana: Addressing Medical and Social Implications.

- The Impact of Antibiotic Resistance on Global Health.

- The Pros and Cons of a Cashless Society.

- Exploring the Relationship Between Technology and Mental Health.

- The Role of Government Surveillance in Ensuring National Security.

- Addressing the Digital Divide: Ensuring Access to Technology for All.

- The Impact of Social Media on Political Activism.

- The Ethics of Animal Rights and Welfare.

- Nuclear Disarmament: Necessity or Utopian Ideal?

- The Effects of Income Inequality on Societal Well-being.

- The Role of Education in Combating Systemic Racism.

- The Influence of Pop Culture on Society's Values and Norms.

- Artificial Intelligence and Its Impact on Creative Industries.

- The Pros and Cons of Mandatory Vaccination Policies.

- The Role of Women in Leadership Positions: Breaking the Glass Ceiling.

- Internet Privacy: Balancing Personal Security and Data Collection.

- The Impact of Social Media on Youth Mental Health.

- The Morality of Animal Agriculture and Factory Farming.

- The Rise of Online Learning Platforms: Transforming Education.

- Addressing the Digital Gender Gap in STEM Fields.

- The Impact of Global Tourism on Local Cultures and Environments.

- Exploring the Implications of 3D Printing Technology in Various Industries.

By the way, we have another great collection of narrative essay topics to get your creative juices flowing.

Wrapping Up

Throughout this guide, you have acquired valuable insights into the art of crafting compelling arguments and presenting diverse perspectives. By delving into the nuances of topic selection, structuring, and incorporating evidence, you could hone your critical thinking skills and sharpen your ability to engage in informed discourse.

This guide serves as a roadmap, offering not just a set of rules but a toolkit to empower students in their academic journey. As you embark on future writing endeavors, armed with the knowledge gained here, you can confidently navigate the challenges of constructing well-reasoned, balanced discursive essays that contribute meaningfully to academic discourse and foster a deeper understanding of complex issues. If you want to continue your academic learning journey right now, we suggest that you read about the IEEE format next.

Overwhelmed by Essays?

Let professional writers be your writing wingman. No stress - just success!

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

26 Planning a Discursive Essay

Discursive essay – description.

A discursive essay is a form of critical essay that attempts to provide the reader with a balanced argument on a topic, supported by evidence. It requires critical thinking, as well as sound and valid arguments (see Chapter 25) that acknowledge and analyse arguments both for and against any given topic, plus discursive essay writing appeals to reason, not emotions or opinions. While it may draw some tentative conclusions, based on evidence, the main aim of a discursive essay is to inform the reader of the key arguments and allow them to arrive at their own conclusion.

The writer needs to research the topic thoroughly to present more than one perspective and should check their own biases and assumptions through critical reflection (see Chapter 30).

Unlike persuasive writing, the writer does not need to have knowledge of the audience, though should write using academic tone and language (see Chapter 20).

Choose Your Topic Carefully

A basic guide to choosing an assignment topic is available in Chapter 23, however choosing a topic for a discursive essay means considering more than one perspective. Not only do you need to find information about the topic via academic sources, you need to be able to construct a worthwhile discussion, moving from idea to idea. Therefore, more forward planning is required. The following are decisions that need to be considered when choosing a discursive essay topic:

- These will become the controlling ideas for your three body paragraphs (some essays may require more). Each controlling idea will need arguments both for and against.

- For example, if my topic is “renewable energy” and my three main (controlling) ideas are “cost”, “storage”, “environmental impact”, then I will need to consider arguments both for and against each of these three concepts. I will also need to have good academic sources with examples or evidence to support my claim and counter claim for each controlling idea (More about this in Chapter 27).

- Am I able to write a thesis statement about this topic based on the available research? In other words, do my own ideas align with the available research, or am I going to be struggling to support my own ideas due to a lack of academic sources or research? You need to be smart about your topic choice. Do not make it harder than it has to be. Writing a discursive essay is challenging enough without struggling to find appropriate sources.

- For example, perhaps I find a great academic journal article about the uptake of solar panel installation in suburban Australia and how this household decision is cost-effective long-term, locally stored, and has minimal, even beneficial environmental impact due to the lowering of carbon emissions. Seems too good to be true, yet it is perfect for my assignment. I would have to then find arguments AGAINST everything in the article that supports transitioning suburbs to solar power. I would have to challenge the cost-effectiveness, the storage, and the environmental impact study. Now, all of a sudden my task just became much more challenging.

- There may be vast numbers of journal articles written about your topic, but consider how relevant they may be to your tentative thesis statement. It takes a great deal of time to search for appropriate academic sources. Do you have a good internet connection at home or will you need to spend some quality time at the library? Setting time aside to complete your essay research is crucial for success.

It is only through complete forward planning about the shape and content of your essay that you may be able to choose the topic that best suits your interests, academic ability and time management. Consider how you will approach the overall project, not only the next step.

Research Your Topic

When completing a library search for online peer reviewed journal articles, do not forget to use Boolean Operators to refine or narrow your search field. Standard Boolean Operators are (capitalized) AND, OR and NOT. While using OR will expand your search, AND and NOT will reduce the scope of your search. For example, if I want information on ageism and care giving, but I only want it to relate to the elderly, I might use the following to search a database: ageism AND care NOT children. Remember to keep track of your search strings (like the one just used) and then you’ll know what worked and what didn’t as you come and go from your academic research.

The UQ Library provides an excellent step-by-step guide to searching databases:

Searching in databases – Library – University of Queensland (uq.edu.au)

Did you know that you can also link the UQ Library to Google Scholar? This link tells you how:

Google Scholar – Library – University of Queensland (uq.edu.au)

Write the Thesis Statement

The concept of a thesis statement was introduced in Chapter 21. The information below relates specifically to a discursive essay thesis statement.

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, the discursive essay should not take a stance and therefore the thesis statement must also impartially indicate more than one perspective. The goal is to present both sides of an argument equally and allow the reader to make an informed and well-reasoned choice after providing supporting evidence for each side of the argument.

Sample thesis statements: Solar energy is a cost -effective solution to burning fossil fuels for electricity , however lower income families cannot afford the installation costs .

Some studies indicate that teacher comments written in red may have no effect on students’ emotions , however other studies suggest that seeing red ink on papers could cause some students unnecessary stress. [1]

According to social justice principles, education should be available to all , yet historically, the intellectually and physically impaired may have been exempt from participation due to their supposed inability to learn. [2]

This is where your pros and cons list comes into play. For each pro, or positive statement you make, about your topic, create an equivalent con, or negative statement and this will enable you to arrive at two opposing assertions – the claim and counter claim.

While there may be multiple arguments or perspectives related to your essay topic, it is important that you match each claim with a counter-claim. This applies to the thesis statement and each supporting argument within the body paragraphs of the essay.

It is not just a matter of agreeing or disagreeing. A neutral tone is crucial. Do not include positive or negative leading statements, such as “It is undeniable that…” or “One should not accept the view that…”. You are NOT attempting to persuade the reader to choose one viewpoint over another.

Leading statements / language will be discussed further, in class, within term three of the Academic English course.

Thesis Structure:

- Note the two sides (indicated in green and orange)

- Note the use of tentative language: “Some studies”, “may have”, “could cause”, “some students”

- As the thesis is yet to be discussed in-depth, and you are not an expert in the field, do not use definitive language

- The statement is also one sentence, with a “pivot point” in the middle, with a comma and signposting to indicate a contradictory perspective (in black). Other examples include, nevertheless, though, although, regardless, yet, albeit. DO NOT use the word “but” as it lacks academic tone. Some signposts (e.g., although, though, while) may be placed at the start of the two clauses rather than in the middle – just remember the comma, for example, “While some studies suggest solar energy is cost-effective, other critical research questions its affordability.”

- Also note that it is based on preliminary research and not opinion: “some studies”, “other studies”, “according to social justice principles”, “critical research”.

Claims and Counter Claims

NOTE: Please do not confuse the words ‘claim’ and ‘counter-claim’ with moral or value judgements about right/wrong, good/bad, successful/unsuccessful, or the like. The term ‘claim’ simply refers to the first position or argument you put forward (whether for or against), and ‘counter-claim’ is the alternate position or argument.

In a discursive essay the goal is to present both sides equally and then draw some tentative conclusions based on the evidence presented.

- To formulate your claims and counter claims, write a list of pros and cons.

- For each pro there should be a corresponding con.

- Three sets of pros and cons will be required for your discursive essay. One set for each body paragraph. These become your claims and counter claims.

- For a longer essay, you would need further claims and counter claims.

- Some instructors prefer students to keep the pros and cons in the same order across the body paragraphs. Each paragraph would then have a pro followed by a con or else a con followed by a pro. The order should align with your thesis; if the thesis gives a pro view of the topic followed by a negative view (con) then the paragraphs should also start with the pro and follow with the con, or else vice versa. If not aligned and consistent, the reader may easily become confused as the argument proceeds. Ask your teacher if this is a requirement for your assessment.

Use previous chapters to explore your chosen topic through concept mapping (Chapter 18) and essay outlining (Chapter 19), with one variance; you must include your proposed claims and counter claims in your proposed paragraph structures. What follows is a generic model for a discursive essay. The following Chapter 27 will examine this in further details.

Sample Discursive Essay Outline

The paragraphs are continuous; the dot-points are only meant to indicate content.

Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Essay outline (including 3 controlling ideas)

Body Paragraphs X 3 (Elaboration and evidence will be more than one sentence, though the topic, claim and counter claim should be succinct)

- T opic sentence, including 1/3 controlling ideas (the topic remains the same throughout the entire essay; it is the controlling idea that changes)

- A claim/assertion about the controlling idea

- E laboration – more information about the claim

- E vidence -academic research (Don’t forget to tell the reader how / why the evidence supports the claim. Be explicit in your E valuation rather than assuming the connection is obvious to the reader)

- A counter claim (remember it must be COUNTER to the claim you made, not about something different)

- E laboration – more information about the counter claim

- E vidence – academic research (Don’t forget to tell the reader how / why the evidence supports the claim. Be explicit in your E valuation rather than assuming the connection is obvious to the reader)

- Concluding sentence – L inks back to the topic and/or the next controlling idea in the following paragraph

Mirror the introduction. The essay outline should have stated the plan for the essay – “This essay will discuss…”, therefore the conclusion should identify that this has been fulfilled, “This essay has discussed…”, plus summarise the controlling ideas and key arguments. ONLY draw tentative conclusions BOTH for and against, allowing the reader to make up their own mind about the topic. Also remember to re-state the thesis in the conclusion. If it is part of the marking criteria, you should also include a recommendation or prediction about the future use or cost/benefit of the chosen topic/concept.

A word of warning, many students fall into the generic realm of stating that there should be further research on their topic or in the field of study. This is a gross statement of the obvious as all academia is ongoing. Try to be more practical with your recommendations and also think about who would instigate them and where the funding might come from.

This chapter gives an overview of what a discursive essay is and a few things to consider when choosing your topic. It also provides a generic outline for a discursive essay structure. The following chapter examines the structure in further detail.

- Inez, S. M. (2018, September 10). What is a discursive essay, and how do you write a good one? Kibin. ↵

- Hale, A., & Basides, H. (2013). The keys to academic English. Palgrave ↵

researched, reliable, written by academics and published by reputable publishers; often, but not always peer reviewed

assertion, maintain as fact

The term ‘claim’ simply refers to the first position or argument you put forward (whether for or against), and ‘counter-claim’ is the alternate position or argument.

Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write a Good Discursive Essay?

05 June, 2020

7 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

What does a discursive essay mean? We have an answer to this and many other questions in our article. Welcome to the world of ideal essay writing. Ever wanted to build buzz for your text? We know you do. And we also know how you can do that with minimum effort and little diligence. So forget about your trivial academic essays - they are not as exciting as a discursive one. Ready to dive in?

What is Discursive Writing?

For all those who wanted to know the discursive essay meaning, here it is: a discursive essay is a writing piece, in which the focal element is devoted to an argument. That is, discursive writing presupposes developing a statement that ignites active discussions. After this essay, readers should be motivated to express their own opinions regarding the topic. Discursive essays have much in common with argumentative and persuasive papers, but these are not to be confused. Despite some similarities, discursive writing is a separate type of work that has its specific features and nuances. What we do want you to remember about discursive essays is that you need to concentrate on the power of thought rather than factology and pieces of evidence. In short, your mind is the only tool required to persuade and interest others on the topic you choose.

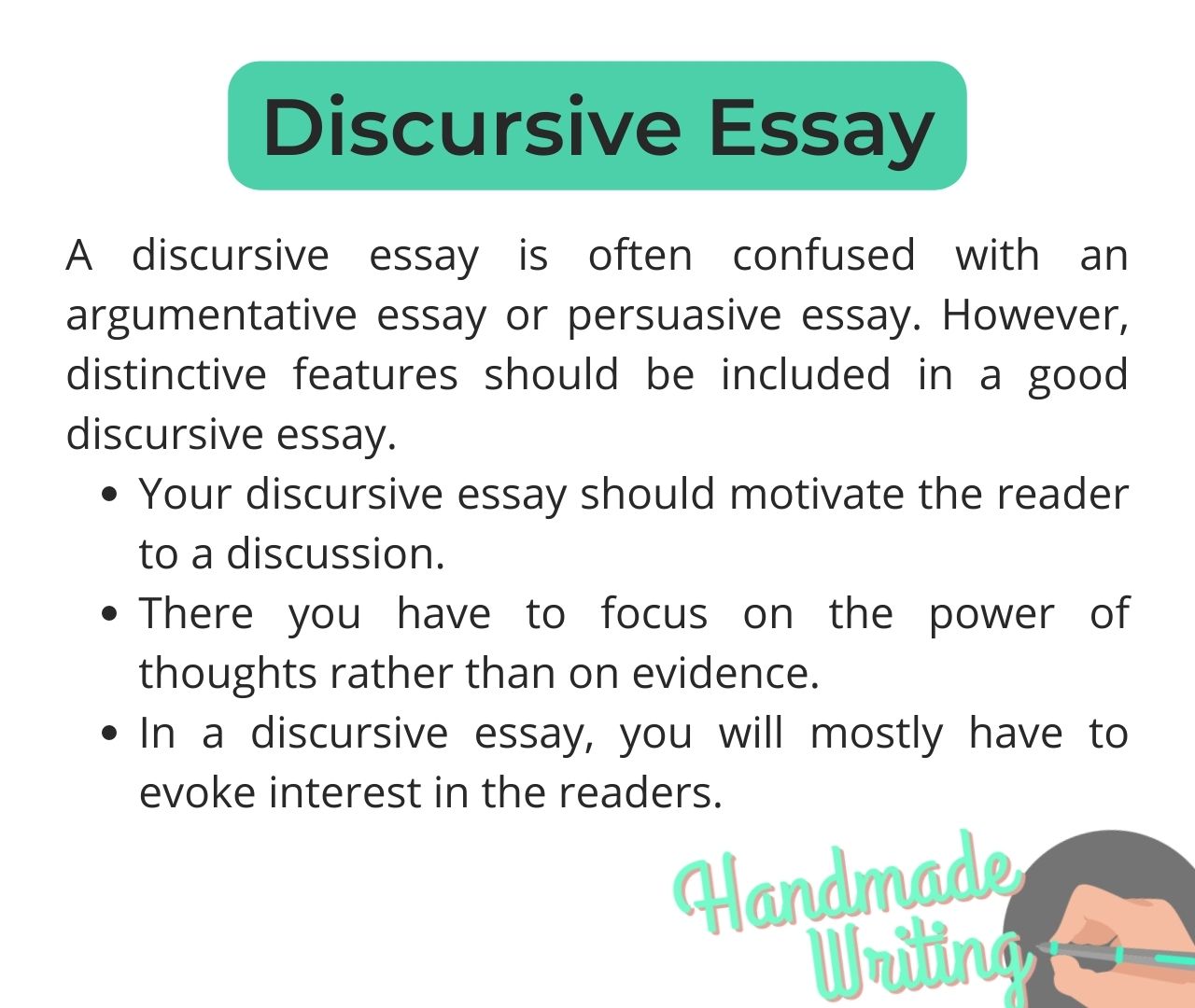

Discursive Essay Format

Now that we’ve figured out what is discursive writing, it’s time to focus more on the “skeleton” of discursive essay. Like any other piece of writing, discursive essays have clear requirements that help to glue their elements into a coherent paper. By the way, there are many writing services available which can help you present an excellent academic essay. So if you need professional assistance with your task, check them out. But if you want to do it yourself, you can simply take any discursive essay example from the web and use it as a starting point for your paper.

As for the discursive structure itself, you need to start your essay with an introduction in the first place. Create a lead-in that’ll spark the reader’s interest and make them genuinely responsive to the topic. Also, make sure that your introduction is neither small nor extensive. Stick to the optimal amount of words that’ll be sufficient for readers to get the general idea of your essay.

Another essential aspect of an effective intro is your opinion. It’s worthy of note that some discursive essays might require no particular stance on the topic. In situations like this, wait until the end of an essay comes, and only then share your personal view on the matter. This way, readers will understand the neutral tone throughout the piece, shape their own thoughts about it, and later decide whether to agree with yours or not.

In the paragraphs that follow, you’ll need to accentuate on the argumentation. There’s no room for vague and unarticulate expressions at this point. Quite the contrary – you need to unfold your statements consecutively, in a couple of paragraphs, to depict the entire image of your stance for or against the topic. And don’t forget to link your discursive text to supporting evidence.

The last section is the conclusion. Your finishing remarks should clearly articulate your position toward this or that issue, with a close connection to the main ideas in the essay body.

Discursive Essay Thesis

To construct a good thesis for your discursive essay, you’ll need to describe the general stance your work will argue. Here, it’s important to back up the thesis statement with points. These are the opinions that support your thesis and allow to create an affirmative structure for the entire paper.

Discursive Essay Linking Words

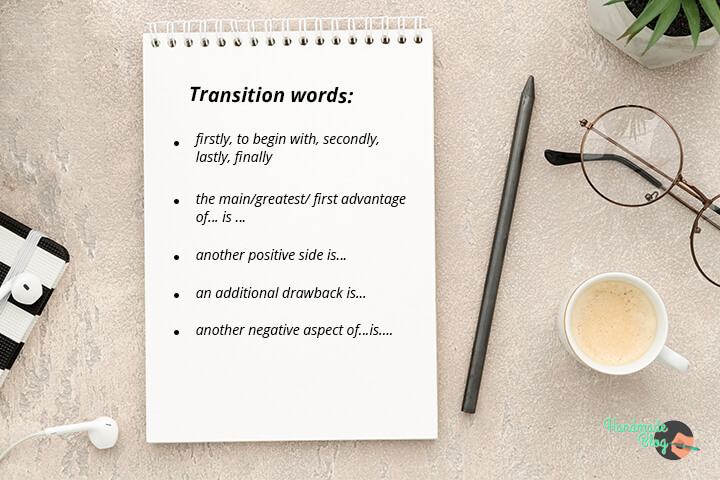

The points you use while writing a discursive essay need to flow smoothly so that readers could see a logical organization of the work. For this, you can use transition words that’ll make your paper easily readable and crisp. For example, if you want to list some points, opt for such words as firstly, to begin with, secondly, lastly, finally, etc. If you wish to point at advantages or disadvantages, consider using these transitions: the main/greatest/ first advantage of… is …, another positive side is…, an additional drawback is, another negative aspect of…is…

How to Write an Introduction for a Discursive Essay?

The introductory part is the critical aspect of creating a good discursive essay. In this section, specific attention should centralize on what your topic is all about. Therefore, it needs to be presented with clarity, be informative, and attention-grabbing. How to make your intro sentence for discursive essay memorable? You can start with a spicy anecdote to add humor to discussion. Another powerful way for hooking readers is stating a quote or opinion of experts and famous influencers. This will add to the credibility of your statements, making readers more motivated to read your work.

How to Write a Discursive Essay Conclusion?

Your discursive essay ending is the climax of your argument, a final link that organically locks up a chain of previously described points. This part is devoted to the restatement of the main arguments that sum up your attitude to the topic. And just like with introduction, the conclusion should leave a trace in readers’ minds. To achieve this result, your closing paragraph should include a call to action, warning or any other food for thought that will encourage people to ponder on the issue and make relevant conclusions.

Discursive Essay Topics

The ideas for discursive papers are so versatile that it’s hard to compile all of them in one list. For such list will extend to kilometers. However, we’ve collected some of them for you to facilitate your work on this task. So here are some discursive essay examples you can use any time:

As you understand now, discursive writing definition and discursive essay definition are not as scary as they seem from the first glance. Even though the art of this type of paper is hard to master, over time, you’ll notice significant progress. All you need for this is practice and a little bit of patience to understand the subtle nuances of this task and develop the skill of writing confidently. And if you ever wondered what is an essay, a team of professional academic essay writers can give a helping hand and provide you with a top-notch paper.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- Buy Custom Assignment

- Custom College Papers

- Buy Dissertation

- Buy Research Papers

- Buy Custom Term Papers

- Cheap Custom Term Papers

- Custom Courseworks

- Custom Thesis Papers

- Custom Expository Essays

- Custom Plagiarism Check

- Cheap Custom Essay

- Custom Argumentative Essays

- Custom Case Study

- Custom Annotated Bibliography

- Custom Book Report

- How It Works

- +1 (888) 398 0091

- Essay Samples

- Essay Topics

- Research Topics

- Writing Tips

How to Write a Discursive Essay

November 17, 2023

A discursive essay is a type of academic writing that presents both sides of an argument or issue. Unlike an argumentative essay where you take a clear stance and defend it, a discursive essay allows you to explore different perspectives and provide an objective analysis. It requires careful research, critical thinking, and the ability to present logical arguments in a structured manner.

In a discursive essay, you are expected to examine the topic thoroughly, present evidence and examples to support your points, and address counterarguments to demonstrate a balanced understanding of the issue. The purpose is not to persuade the reader to take a particular side, but rather to present a comprehensive view of the topic. By mastering the art of writing a discursive essay, you can effectively convey complex ideas and contribute to meaningful discussions on various subjects.

What’s different about writing a discursive essay

Writing a discursive essay differs from other types of essays in several ways. Here are some key differences to consider when approaching this particular form of academic writing:

- Explores multiple perspectives: Unlike an argumentative essay, a discursive essay examines different viewpoints on a given topic. It requires you to gather information, analyze various arguments, and present a balanced view.

- Structured presentation: A discursive essay follows a clear structure that helps organize your thoughts and arguments. It typically consists of an introduction, several body paragraphs discussing different arguments, and a conclusion.

- Impartiality and objectivity: While other essays may require you to take a stance or defend a particular position, a discursive essay aims for objectivity. You should present arguments and evidence without bias and demonstrate a fair understanding of each viewpoint.

- Importance of research: Good research is essential for a discursive essay. You should gather information from reliable sources, consider various perspectives, and present evidence to support your ideas.

- Addressing counterarguments: In a discursive essay, it is crucial to acknowledge and address counterarguments. By doing so, you show a comprehensive understanding of the topic and strengthen your own argument.

- Use of transitions: To maintain coherence and provide a smooth flow of ideas, appropriate transitions should be used to link paragraphs and signal shifts between arguments.

By recognizing these key differences and adapting your writing style accordingly, you can effectively write a discursive essay that engages the reader and presents a well-rounded discussion of the topic.

Step-by-Step Discursive Essay Writing Guide

Selecting a topic.

Selecting a topic for a discursive essay is a crucial first step in the writing process. Here are some considerations to help you choose an appropriate and engaging topic:

- Relevance: Select a topic that is relevant and holds significance in the current context. It should be something that sparks interest and discussion among readers.

- Controversy: Look for topics that have multiple perspectives and controversial viewpoints. This will allow you to explore different arguments and present a balanced analysis.

- Research opportunities: Choose a topic that offers ample research opportunities. This ensures that you have access to reliable sources and enough material to support your arguments.

- Personal interest: It is easier to write about a topic that you are genuinely interested in. Consider your own passion and areas of expertise when selecting a subject for your essay.

- Scope and depth: Ensure that the chosen topic is neither too broad nor too narrow. It should provide enough scope for thorough analysis and discussion within the word limit of your essay.

Remember, the topic sets the foundation for your discursive essay. Take time to consider these factors and select a topic that aligns with your interests, research capabilities, and the potential to present a well-rounded discussion.

Possible Discursive Essay Topics:

- The impact of social media on society.

- Should euthanasia be legalized?