Sulu’s exit shakes up Bangsamoro: 5 scenarios for the 2025 polls

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Filipinos face the mental toll of the Covid-19 pandemic — a photo essay

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

BY ORANGE OMENGAN

Depression, anxiety, and other mental health-related illnesses are on the rise among millennials as they face the pressure to be functional amidst pandemic fatigue. Omengan’s photo essay shows three of the many stories of mental health battles, of struggling to stay afloat despite the inaccessibility of proper mental health services, which worsened due to the series of lockdowns in the Philippines.

“I was just starting with my new job, but the pandemic triggered much anxiety causing me to abandon my apartment in Pasig and move back to our family home in Mabalacat, Pampanga.”

This was Mano Dela Cruz’s quick response to the initial round of lockdowns that swept the nation in March 2020.

Anxiety crept up on Mano, who was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder traits. The 30-year-old writer is just one of many Filipinos experiencing the mental health fallout of the pandemic.

Covid-19 infections in the Philippines have reached 1,149,925 cases as of May 17. The pandemic is unfolding simultaneously with the growing number of Filipinos suffering from mental health issues. At least 3.6 million Filipinos suffer from mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, according to Frances Prescila Cuevas, head of the National Mental Health Program under the Department of Health.

As the situation overwhelmed him, Mano had to let go of his full-time job. “At the start of the year, I thought I had my life all together, but this pandemic caused great mental stress on me, disrupting my routine and cutting my source of income,” he said.

Mano has also found it difficult to stay on track with his medications. “I don’t have insurance, and I do not save much due to my medical expenses and psychiatric consultations. On a monthly average, my meds cost about P2,800. With my PWD (person with disability) card, I get to avail myself of the 20% discount, but it’s still expensive. On top of this, I pay for psychiatric consultations costing P1,500 per session. During the pandemic, the rate increased to P2,500 per session lasting only 30 minutes due to health and safety protocols.”

The pandemic has resulted in substantial job losses as some businesses shut down, while the rest of the workforce adjusted to the new norm of working from home.

Ryan Baldonado, 30, works as an assistant human resource manager in a business process outsourcing company. The pressure from work, coupled with stress and anxiety amid the community quarantine, took a toll on his mental health.

Before the pandemic, Ryan said he usually slept for 30 hours straight, often felt under the weather, and at times subjected himself to self-harm. “Although the symptoms of depression have been manifesting in me through the years, due to financial concerns, I haven’t been clinically diagnosed. I’ve been trying my best to be functional since I’m the eldest, and a lot is expected from me,” he said.

As extended lockdowns put further strain on his mental health, Ryan mustered the courage to try his company’s online employee counseling service. “The free online therapy with a psychologist lasted for six months, and it helped me address those issues interfering with my productivity at work,” he said.

He was often told by family or friends: “Ano ka ba? Dapat mas alam mo na ‘yan. Psych graduate ka pa man din!” (As a psych graduate, you should know better!)

Ryan said such comments pressured him to act normally. But having a degree in psychology did not make one mentally bulletproof, and he was reminded of this every time he engaged in self-harming behavior and suicidal thoughts, he said.

“Having a degree in psychology doesn’t save you from depression,” he said.

Depression and anxiety are on the rise among millennials as they face the pressure to perform and be functional amid pandemic fatigue.

Karla Longjas, 27, is a freelance artist who was initially diagnosed with major depression in 2017. She could go a long time without eating, but not without smoking or drinking. At times, she would cut herself as a way to release suppressed emotions. Karla’s mental health condition caused her to get hospitalized twice, and she was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder in 2019.

“One of the essentials I had to secure during the onset of the lockdown was my medication, for fear of running out,” Karla shared.

With her family’s support, Karla can afford mental health care.

She has been spending an average of P10,000 a month on medication and professional fees for a psychologist and a psychiatrist. “The frequency of therapy depends on one’s needs, and, at times, it involves two to three sessions a month,” she added.

Amid the restrictions of the pandemic, Karla said her mental health was getting out of hand. “I feel like things are getting even crazier, and I still resort to online therapy with my psychiatrist,” she said.

“I’ve been under medication for almost four years now with various psychologists and psychiatrists. I’m already tired of constantly searching and learning about my condition. Knowing that this mental health illness doesn’t get cured but only gets manageable is wearing me out,” she added. In the face of renewed lockdowns, rising cases of anxiety, depression, and suicide, among others, are only bound to spark increased demand for mental health services.

MANO DELA CRUZ

Writer Mano Dela Cruz, 30, is shown sharing stories of his manic episodes, describing the experience as being on ‘top of the world.’ Individuals diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II suffer more often from episodes of depression than hypomania. Depressive periods, ‘the lows,’ translate to feelings of guilt, loss of pleasure, low energy, and thoughts of suicide.

Mano says the mess in his room indicates his disposition, whether he’s in a manic or depressive state. “I know that I’m not stable when I look at my room and it’s too cluttered. There are days when I don’t have the energy to clean up and even take a bath,” he says.

Mano was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II in 2016, when he was in his mid-20s. His condition comes with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder traits, requiring lifelong treatment with antipsychotics and mood stabilizers such as antidepressants.

Mano resorts to biking as a form of exercise and to release feel-good endorphins, which helps combat depression, according to his psychiatrist.

Mano waits for his psychiatric consultation at a hospital in Angeles, Pampanga.

Mano shares a laugh with his sister inside their home. “It took a while for my family to understand my mental health illness,” he says. It took the same time for him to accept his condition.

RYAN BALDONADO

Ryan Baldonado, 30, shares his mental health condition in an online interview. Ryan is in quarantine after experiencing symptoms of Covid-19.

KARLA LONGJAS

Karla Longjas, 27, does a headstand during meditative yoga inside her room, which is filled with bottles of alcohol. Apart from her medications, she practices yoga to have mental clarity, calmness, and stress relief.

Karla shares that in some days, she has hallucinations and tries to sketch them.

In April 2019, Karla was inflicting harm on herself, leading to her two-week hospitalization as advised by her psychiatrist. In the same year, she was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. The stigma around her mental illness made her feel so uncomfortable that she had to use a fake name to hide her identity.

Karla buys her prescriptive medications in a drug store. Individuals clinically diagnosed with a psychosocial disability can avail themselves of the 20% discount for persons with disabilities.

Karla Longjas is photographed at her apartment in Makati. Individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) exhibit symptoms such as self-harm, unstable relationships, intense anger, and impulsive or self-destructive behavior. BPD is a dissociative disorder that is not commonly diagnosed in the Philippines.

This story is one of the twelve photo essays produced under the Capturing Human Rights fellowship program, a seminar and mentoring project

organized by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Photojournalists’ Center of the Philippines.

Check the other photo essays here.

Larry Monserate Piojo – “Terminal: The constant agony of commuting amid the pandemic”

Orange Omengan – “Filipinos face the mental toll of the Covid-19 pandemic”

Lauren Alimondo – “In loving memory”

Gerimara Manuel – “Pinagtatagpi-tagpi: Mother, daughter struggle between making a living and modular learning”

Pau Villanueva – “Hinubog ng panata: The vanishing spiritual traditions of Aetas of Capas, Tarlac”

Bernice Beltran – “Women’s ‘invisible work'”

Dada Grifon – “From the cause”

Bernadette Uy – “Enduring the current”

Mark Saludes – “Mission in peril”

EC Toledo – “From sea to shelf: The story before a can is sealed”

Ria Torrente – “HIV positive mother struggles through the Covid-19 pandemic”

Sharlene Festin – “Paradise lost”

PCIJ’s investigative reports

THE SHRINKING GODS OF PADRE FAURA | READ .

7 MILLION HECTARES OF PHILIPPINE LAND IS FORESTED – AND THAT’S BAD NEWS | READ

FOLLOWING THE MONEY: PH MEDIA LESSONS FOR THE 2022 POLL | READ

DIGGING FOR PROFITS: WHO OWNS PH MINES? | READ

THE BULACAN TOWN WHERE CHICKENS ARE SLAUGHTERED AND THE RIVER IS DEAD | READ

Pandemic in the Philippines: The Struggle Within

- Photographer George Calvelo

- Prize Honorable Mention

Michael Zajakowski There were many excellent photo stories of the pandemic and how nations, states medical professionals and individuals responded. Or didn’t. This photographer’s record of the response in the Philippines is overlaid on the country’s pre-existing conditions of autocratic rule, political corruption and violence and underlying climate and health care challenges. The photographs are not elegant or beautiful, like some of the photo essays we have come to revere, but the situations photographed are precise and moving, exposing the gamut of human emotions, and the editing is precise. Among the hundreds of photo essays about communities confronting the pandemic, this ongoing project stands as a model for bearing witness.

- Company/Studios Freelance

- Date of Photograph Various dates throughout 2020-2021

- Technical Info Various settings

These photos are from my ongoing documentary on the Philippine government's response to the COVID19 pandemic, and how the most affected people struggle to deal with what is left for them. Several corruption issues, human rights violations, abuse of power, politicking by power-hungry officials, and the deteriorating climate situation. These are what the Filipino people have to face. All of these as the presidential election is fast approaching.

Considered having one of the longest lockdowns in the world, the Philippines continue to implement quarantine protocols while struggling to address the damage the pandemic has brought to its people and economy. By mandating the general public to wear plastic face shields on top of wearing masks, people can't help but say that those in power are more concerned about business opportunities than about solving the problem. Children had to take part in online learning, which presented multiple problems for students, teachers, and parents. Politicians take advantage of the crisis by seemingly creating problems for them to solve, a ridiculously obvious campaign stint. Cash assistance drives initiated by the government have seen problems that only the most affected feel. Job losses, businesses closing down, the death of several loved ones, multiple severe typhoons, and climate emergencies. This is what the Filipino people continue to face. As the country starts to feel the blow of the more transmissible COVID19 delta variant, the Department of Health tallied 14,249 new cases in a single day, based on their latest bulletin as of August 14, 2021. This brings the total number of cases to 1,727,231. More than a year of lockdown, the government’s idea of battling the virus was to beef up the presence of uniformed personnel on the streets, with an order to arrest quarantine violators and those who didn’t want to get vaccinated. A statement of the president which his staff conveniently pass off as 'jokes' that aren't meant to be taken seriously. Despite multiple loans amounting to billions of dollars since last year, a recent report by national auditors revealed deficiencies in the Health Department’s spending for the COVID19 response fund amounting to a total of P67.32 billion. Here in the Philippines, it isn't surprising at all to hear people say that these experiences are clear signs that the election season is fast approaching.

You can create multiple entries, and pay for them at the same time. Just go to your History , and select multiple entries that you would like to pay for.

Award-winning Filipino photographer shares how photography can help amid COVID-19

An esteemed overseas Filipino photographer calls on aspiring artists to pursue their passion, and put their talent to good use especially during amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

Staff Report

Related articles.

Bakasyon sa Pinas 101: Budget tips para ready ka sa holidays!

“Be vigilant”: Kathleen Hermosa comments on Labubu toys

Dubai-based fashion designer Michael Cinco among most influential figures in PH

Filipino singer from Abu Dhabi recognized as emerging teen icon at international awards

Privacy overview.

- Agri-Commodities

- Asean Economic Community

- Banking & Finance

- Business Sense

- Entrepreneur

- Executive Views

- Export Unlimited

- Harvard Management Update

- Monday Morning

- Mutual Funds

- Stock Market Outlook

- The Integrity Initiative

- Editorial cartoon

- Design&Space

- Digital Life

- 360° Review

- Biodiversity

- Climate Change

- Environment

- Envoys & Expats

- Health & Fitness

- Mission: PHL

- Perspective

- Today in History

- Tony&Nick

- When I Was 25

- Wine & Dine

- Live & In Quarantine

- Bulletin Board

- Public Service

- The Broader Look

Today’s front page, Monday, November 18, 2024

- Covid-19 Updates

- Photo Gallery

The best of Filipino self-reliance and resiliency in face of a lingering Covid-19 pandemic

Manuel cayon.

- March 15, 2022

- 5 minute read

THE battle cry—“Buy local and Patronize local”—has been enunciated in the past in certain tight economic situations, and resurfaced anew, this time in the early period of the Covid-19 rampage as nations closed their borders, restricting travel and movement of people.

As a consequence, shops and factories shut down as people lost customers and as customers become penniless. Shops and factories shed off a number of workers, and eventually ceased operations. It’s like a vicious cycle like the virus—still widely unknown then and undeciphered—which scared people enough to keep them home.

Into their homes for months and years, the slogan “Buy Local,” soon emerged as a future tense, of what to do when a hopeful population yearned for the day when shops and factories would reopen soon.

And when the economy stayed afloat despite lockdowns and cyclical imposition, or easing, of movement restriction, the slogan soon assumed life of its own and was adapted by Filipino netizens, all to help everyone trying to eke out a meager living, and to resuscitate a sputtering local economy gasping for air.

AS what they did during at least two episodes of global economic meltdown in 1994 and in 2008, the small local entrepreneurs, the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), fared best in keeping the national economy afloat when corporations and factories, and especially foreign companies, opted to take a lull.

The Davao regional office of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), for example, reported that while export and investment development program was ideal year on year, “the Covid-19 pandemic and the imposition of community quarantine protocols posed challenges in the implementation of the agency’s [DTI] regular programs, activities and projects.” This resulted in limited face-to-face interactions and even rendered some of the projects and programs “unfit and impractical” in the Davao Region.

“Nevertheless, resiliency, creativity and flexibility in providing and facilitating virtual and physical interventions still led to the generation of P806.14 million in domestic sales [in the region],” it said. Of this amount, MSMEs accounted for 76.53 percent, or P616.9 million.

Interesting to note, too, that the next bigger contribution to the domestically-generated sales was chipped in by the Pasalubong Centers, at P139.09 million, which are maintained by local governments seeking to promote their own products that are created by small entrepreneurs.

The DTI said the initial effort to renew trade and commerce was done virtually as what has been recommended and adapted to avoid the spread of the virus. This method, apparently because virtual sessions were still untested, soon flopped at the beginning, the DTI said. It was saved however, when institutional buyers that were still around joined the virtual trade fairs, increasing the sales.

Of these attempts to rejuvenate domestic trade, the DTI counted 31 trade fairs done last year, of which the provincial level accounted for 12; at least 10 were held nationally, seven regionally and only two internationally. The latter was due to the intermittent easing of restrictions as Covid-19 showed a fluctuating trend, mostly going down, but only pushed up sharply in the latter part of the year by the Omicron variant.

IT’S not simply the MSMEs that helped prepare the comeback of trade and commerce in the region. On the part of the DTI, which tracked the progress of entrepreneurs and other livelihood initiatives during the second year of the pandemic, it said it also applied the industry cluster program for mostly agricultural products, sent experts to mentor local entrepreneurs and tendered the Shared Service Facilities (SSF).

It also attended to consumer inquiries and complaints as well as widened the reach of its education and advocacy program to ensure that those stuck in their homes for months will start taking bold steps to entrepreneurship.

Industry clusters have been applied here before to smoothen and streamline the programs and projects fit to each cluster. These are mostly applied to agricultural crops for which the Davao Region and the rest of Mindanao are known for.

There are clusters for cacao, mostly grown in Davao City and some parts of the Davao Region, coffee, coconut, rubber, palm oil, banana, fruits and nuts, bamboo, mango and aquaculture. The non-agriculture clusters are in information and communication technology, wearables and homestyle and tourism.

Last year, these clusters turned in a more than 100 percent performance from targets: exports worth $1,136.11 million (or $1.136 billion), a 346 percent accomplishment from a target of $328.254 million; number of MSMEs assisted at 3,406, a 117 percent effort from a target of assisting 2,906; and number of trainings conducted, at 340, a 113 percent accomplishment from a target of 301 trainings.

The other bottom line accomplishments were nothing to sneeze at: the clusters generated 13,602 jobs during the pandemic, nearly hitting the target of 14,659. The clusters also trained 5,202 beneficiaries, an accomplishment of 95 percent from target of 5,490.

More MSMEs were created too, during this time, with 361 new enterprises. The target was to create 411. Domestic sales reached P403.486 million, also nearly hitting the target of P460.65 million.

Investment, as expected, was low at 20 percent performance at best efforts, getting only P160.574 million worth. The target was to hit P804.5 million worth of investment. The amount of loans facilitated to farmers and co-operatives was as low as P11.943 million, indicating the general sentiment of hesitancy to apply for loans. This amount represented only 11 percent of P170.21 million that was readied for takeout.

THE entrepreneurs’ creativity was not wanting during the pandemic, so the DTI found out. In the region, some 577 were developed, of which 390 were developed through the platform One Town-One Product Next Gen product development activities. Another 167 prototypes were developed through other economic platforms and 20 of these products were developed at the DigiHub-FabLab Davao, established by the University of Southeastern Philippines (USEP), the DTI Region 11 and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST Region 11) at the USEP campus at Barrio Obrero in Davao City.

The DigiHub aims to provide the tools, training and resources for creativity and innovation in the academe, MSMEs, inventor groups, hobbyists and design professionals, its Internet web site said.

Product and investment promotion were not abandoned though, despite the obvious absence of corporate operations, including foreign. Virtual trade fairs continued and product exposition in the national level.

Industry clustering, product promotion and invitations to become engaged in entrepreneurship were done through the program called Negosyo Serbisyo sa Barangay Caravans, of which many of the 131 visits were in identified disadvantaged villages. These caravans made stopovers to orient and instruct residents on topics and skills like Livelihood Seeding Program and Business Registration Assistance and Consultation.

Mentoring was equally helpful, with the DTI’s family-like atmosphere of Kapatid Mentor ME (literally Mentor Me Brother) guiding aspiring and starting businesses on the rudiments of business, such as making a business plan, improving it and other basic business operation.

Business newbies and those aspiring to graduate into the next business level would also be helped with their need for equipment and machinery. Although limited, the DTI has its own SSFs that businesses may apply for their own use.

The DTI said the SSF program is a major component of MSME development to improve their competitiveness by providing them with machinery, equipment, tools systems, skills and knowledge under a shared system. As of December last year, DTI assisted 1,511 MSMEs with 3,684 beneficiaries of the facilities shared with them and generating 3,592 jobs in the process.

Customer care, however, remained a pivotal concern in business; and the DTI said its offices and allied services in the local governments had attended to 384 consumer complaints. These were either endorsed to appropriate agencies, were subjected to mediation and arbitration.

Customer satisfaction is one of the keys for the success of business, but most especially for upstarts and MSMEs.

“With the number of complaints endorsed and escalated for mediation ang arbitration, it shows that the office has been efficient in handling consumers-related-complaints. This resulted in consumer complaints resolution rate of 100 percent,” it said.

Manuel T. Cayon has written about Mindanao for national newspapers for more than two decades, mostly on conflict reporting, and on the political front. His stint with TODAY newspaper in the ’90s started his business reporting in Mindanao, continuing to this day with the BusinessMirror . The multiawarded reporter received a Biotechnology journalism award in January 2019, his third. A fellow of the US International Visitors’ Program Leadership in 2007 on conflict resolution and alternative dispute resolution, Manuel attended college at the Mindanao State University and the Ateneo de Davao University.

- Manuel Cayon https://businessmirror.com.ph/author/manuelcayon/ Mindanao breaks India’s record for trees planted in single hour

- Manuel Cayon https://businessmirror.com.ph/author/manuelcayon/ ComVal to produce local reference book for pupils

- Manuel Cayon https://businessmirror.com.ph/author/manuelcayon/ ARMM sets P100-million development plan for Polloc port

- Manuel Cayon https://businessmirror.com.ph/author/manuelcayon/ Malacañang explores ways to tackle war scars in Moro Mindanao

Related Topics

Let’s do the shake: frotea keeps on bubbling up amid contagion.

- Roderick Abad

- March 1, 2022

Franchising reopens as government loosens Covid curbs

Digital-ready women micro entrepreneurs supported.

- BusinessMirror

- November 20, 2024

US small-business optimism rose in weeks before polls

Fruitas holdings adds roasted chicken chain to its portfolio.

A call for nation building

- Alexey Rola Cajilig

Holiday outlooks due from retailers in test of US consumer

Sg firm offers help to local smes in esg reporting.

- November 6, 2024

DTI-Laguna Provincial Office holds training

Tech innovations secure major equity-free grants in startup qc, do you want some change.

Filipino SMEs find market via store launch in Sydney

GoTyme, Foodpanda partner to support local enterprises

Lafferty to conduct free brand-building conference in Manila on Thursday

- November 5, 2024

Escudero visits Senate tiangge

- October 23, 2024

Asialink, CEO feted for entrepreneurial development

Pay platform operator backs PHL gig economy, MSMEs

- Reine Juvierre S. Alberto

Why you need SMART objectives

Davao micro-entrepreneurs get sen. bong go’s support.

- October 22, 2024

Razon’s by Glenn CEO nominated for EY Young Entrepreneur Award 2024

- September 26, 2024

Fuse, Puregold partner up for BNPL option to MSMes

- Lorenz S. Marasigan

- September 25, 2024

The marks of leadership

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Coronavirus Disease 2019

Filipino responses to covid-19, research documents filipino panic responses to the global pandemic..

Posted April 30, 2020 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- What Is Anxiety?

- Take our Generalized Anxiety Disorder Test

- Find counselling to overcome anxiety

By Georgina Fairbrother

A recent study explored panic responses to COVID-19 in the Philippines. COVID-19 has been declared a global pandemic and has caused mass lockdowns and closures across the globe. An angle relatively unexplored amidst this global pandemic is the impact of COVID-19 on mental health. The survey conducted was a mixed-method study that gathered qualitative and quantitative data in order to better explore the different dimensions of panic responses.

The survey was conducted through convenience sampling by online forms due to government-mandated limitations of social contact and urgency. The online survey ran for three days and gathered 538 responses. The average age of a survey participant was 23.82, with participants ranging in ages from 13-67. 47% of those who completed the survey were working, 45.4% were students and 7.6% were not working. Of those who completed the survey, 1.3% had witnessed direct exposure to a COVID-19 patient, while 26% had witnessed exposure within their community, and 72.7% had not been exposed.

For purposes of the survey, the Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI) Short Week was adapted in order to test illness anxiety on COVID-19 amongst Filipinos. The HAI had four main sections used in this survey: 1) Symptoms of health anxiety (hypochondriasis), 2) Attitudes towards how awful it would be to develop COVID-19, 3) Avoidance, and 4) Reassurance. Responses to questions answered within these areas were scored on a 0-3 basis, compromising the quantitative portion of the study. To complete the qualitative section of the survey three open-ended questions were used. The open-ended questions used for qualitative purposes in this survey were:

“1. What came to your mind when you knew the existence of COVID-19? 2. How do you feel when you know the existence of COVID-19? 3. What actions have you done with the knowledge of existence of COVID-19?”

Upon completion of the survey, researchers were able to analyze data in regard to five different areas. First, researchers discovered that it was very evident that respondents were experiencing moderate illness anxiety in all four aspects listed by HAI. Secondly, by comparing locations, researchers also discovered that respondents residing in Metro Manilla exhibited less avoidance behavior compared to respondents residing outside Metro Manilla. While there is no definitive reason for this result, speculation looms around education , awareness, and proximity to COVID-19 cases. Thirdly, researchers looked at occupation, but determined illness anxiety was present regardless of occupation. Fourthly, researchers determined that respondents who had been in direct contact with those having COVID-19 were more likely to exhibit symptoms of hypochondriasis compared to respondents who had not witnessed or contacted anyone with COVID-19.

The fifth area that researchers explored upon completion of this survey was that of feeling, thinking, and behavior in response to COVID-19. Nineteen different themes were ranked by 100 experts based on their positivity and negativity. The themes included items such as the following: Health Consciousness, Optimism , Cautiousness, Protection, Compliance, Composure, Information Dissemination, Worry on self/family/others, Relating to Past Pandemics, Anxiety, Government Blaming, Shock, Transmission of Virus, Fear, Sadness, Paranoia , Nihilism, Annihilation, and Indifference. Upon completion of the survey, the highest-scoring themes amongst respondents included Fear, Social Distancing, Health Consciousness, and Information Dissemination. Meanwhile, the lowest-scoring themes included Indifference and Nihilism.

Overall, COVID-19 has become a global pandemic that is continuing to move and spread across the world. In the aftermath of this pandemic, it will be interesting to compare the panic responses of different countries. The Philippines approaches this study from a more socially collectivist perspective. With that being said, it was reported that the Philippines leaned towards more individualistic tendencies in times of fear. Another area to look deeper into would include how panic responses change from the initial shock of COVID-19 to lockdown phases to re-emergence phases.

Georgina Fairbrother is a current master’s student in the Humanitarian and Disaster Leadership program at Wheaton College. Prior to her master’s degree, she received a bachelor’s degree in Global Security and Intelligence studies from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

Nicomedes, C. J., & Avila, R. (2020). An Analysis on the Panic of Filipinos During COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17355.54565

Jamie Aten , Ph.D. , is the founder and executive director of the Humanitarian Disaster Institute at Wheaton College.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

COVID-19: In the Eyes of a Filipino Child

Lourdes urbano agbing, josephine dionela agapito, ann marie albano baradi, m bernadette c guzman, clarissa mariano ligon, arsenia tuazon lozano.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Lourdes Urbano Agbing, Miriam College, Quezon City, Philippines. Email: [email protected]

Issue date 2022 Jul.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until permissions are revoked in writing. Upon expiration of these permissions, PMC is granted a perpetual license to make this article available via PMC and Europe PMC, consistent with existing copyright protections.

explore thoughts and feelings of children on COVID-19, find out how they cope, and what they did during lockdown. It was total lockdown in Luzon, Philippines, April 2020 – when survey was conducted; pre-tested open-end questionnaire was administered to children who answered either by paper and pen, or through social media, with parents’ cooperation.

Participants

200 boys and girls, 6-12 years old, public and private schools in NCR-Luzon.

Participants heard COVID-19, pandemic and lock down from media and family; described as deadly, dangerous, contagious, world-wide, death-causing virus; about 90% expressed sadness, fear, boredom, anger, disappointments and difficult time; employed self-enhanced coping mechanisms, and engaged in hobbies and interests to assuage thoughts and feelings; family appeared as saving grace.

Recommendations: develop strategies to assist children during critical events; studies – find out effects of pandemic on participants’ health; visit participants after two years to find out reminiscence of pandemic experience.

Keywords: COVID-19, lock down, pandemic, Filipino, family

In a life time, individuals in different parts of the world have experienced, witnessed and testified on the various natural calamities and disasters which have claimed lives and wrecked properties that occurred at various times of the year, or at different seasons. But this decade, except perhaps in isolated places, peoples of planet earth are witnessing, experiencing and documenting the one and only disaster that is confronting almost every one, everywhere at one time and perhaps, one of the longest durations – the deadly coronavirus disease, now known as COVID-19 ( Tedros, 2020 ). It was estimated that mortality figures globally may be around the 50 million level ( British Medical Journal, 2020 ; World Health Organization, 2020 ). In the Philippines, people in the different regions continue to be victims of natural calamities, like the destructive typhoons where strong rains, violent winds and drowning floods, and volcanic eruptions, have become part of the Filipino life. However, COVID-19 is a tragic disaster that is not only new but which the people are very much unprepared to confront with.

In an unprecedented turn, from epidemic to pandemic, the Philippines together with the world woke up to an invisible enemy that suddenly everything was put to a halt: economically, small industries to huge corporate businesses ceased operations; people are socially-distanced; all kinds of offices and institutions were closed; worshipers attend online services; countries, states, provinces, and communities were locked down.

People who are ever busy with daily concerns found themselves locked in their homes. It was one of those moments that we found a common interest, and conceptualized a study on how children are affected by the pandemic.

There were attempts to search for studies on Filipino children’s emotions during disasters and calamities but due to time constraints and in our desire to grab the opportune time to conduct this study, the hunt was not really exhaustive.

It appeared that many studies conducted on corona virus and children are mostly focused on health concerns particularly in the infant stage however, we selected online articles on the issues which are somehow related to our topic. One is the multinational, multicenter cohort study of COVID-19 and children, although focused on service planning and allocation of resources, children’s health condition (18 years and younger) were discussed since they are the benefactors of the services. Riphagen et al. (2020) found an unprecedented cluster of eight children (8 to 14 years) with hyperinflammatory shock which formed the basis of a national alert for a huge number of children to undergo test for corona virus.

Adigun (2020) reported that COVID-19 disease in children is usually mild, fatalities rare as UK study says; that children are not as adversely affected by COVID-19 as adults. However, it did not mention of the possible negative effects of the virus on the children’s mental, emotional, and psychological health, and the consequences in their later childhood life.

Going a little back, the research brief on ‘The Impact of Natural Disaster on Childhood Education’ looked at devastating earthquakes’ effect on young people in Nepal reported that children around the world react similarly to disasters despite differences in cultures and resources ( Crowder, 2016 ). Strauss (2017) pointed out, that based on research, children who were victims of disasters can suffer from trauma and bereavement far longer than adults realize, and this can affect not only how well they perform at school but also the trajectory of their lives. The study of Gibbs et al. (2019) showed that social disruption caused by natural disasters often interrupts educational opportunities for children but little is known about children's learning in the following years, their findings highlight the importance of building and maintaining supportive relationships following a disaster. Ramchandani (2020) expressed his view that the direct impact of COVID-19 on children seems to be less severe than on adults but indirect and hidden consequences will have a lasting effect on children's education, social life and physical and mental health.

Wang (2020) showed how to support children (and families) during quarantine to reduce the risk of negative mental health. The initial findings of a study involving young children (ages four to 10) suggest that they are worried about family and friends catching the virus; afraid to leave their homes and are worried there will not be enough food to eat; and over a one-month period in lockdown parents/carers reported that they saw increases in their child’s emotional difficulties, such as feeling unhappy, worried, being clingy and experiencing physical symptoms associated with worry ( Pearcey et al., 2020 ).

We may not be aware, or know much about what the concept of threat of the current pandemic brings or means to a school-age child who have never experienced a dreadful event. This is our most important concern and interest which motivated us to pursue this study during the lockdown period. We thought that it is best at this time to explore what are their unspoken sentiments when the invisible COVID-19 is at its height in its attack against anyone. We envision that we can help mollify some of the negative effects of COVID-19 on young children when we know their thoughts and feelings, and what they do during lockdown. The image of the Filipino child in an uncharted environmental condition, guided and inspired us to answer the following objectives:

To explore the thoughts and feelings of children about COVID-19,

To find out how they cope with the pandemic, and

To know what they did during the lockdown

Methodology

Research design.

This is a descriptive survey which employed a pre-tested open-end questionnaire and used a non-standardized measurement.

Sampling Method

Due to the total lockdown brought about by COVID-19 pandemic, the study utilized the purposive sampling technique. Parents or guardians known to the researchers were contacted through the cell phone, or email, and requested for their children who met the criteria, to be a participant to the study. The sampling method was constrained by unavailability of resources like contacting more parents who may not have access to the social media; the parents’ inaccessibility to the gadget to print the questionnaires; a place to administer the questionnaire such as in a classroom or a private place; and for us, the researchers, to administer the questionnaire to the participants.

Parents or guardians who consented to have their children who met the criteria – in school, ages 6-12 years old – signed up using email, or cell phone (some questionnaires were sent through Messenger as requested by parents). The online google research form method was a last recourse when the paper and pencil technique was found problematic by parents who reported difficulty in producing the printed questionnaire for lack of printers in their home.

An open-ended questionnaire which included a page for participants’ age, gender, grade level and school type, was pre-tested to 20 children whose characteristics were similar to intended participants to the study. In the final questionnaire, added were the participants’ nickname and birthdate for encoding.

The final questionnaire consisted of 11 open-end items on the issues: COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown.

A separate page addressed to the parent or guardian requesting for their comments was added as the last page of the questionnaire.

Data-gathering method was through the aforesaid media. The questionnaire with a letter to the parent/guardian explained the purpose of the study, and asked consent for their child’s participation in the study. Parents were given the questionnaire, through email or cell phone, where the child answered on it directly, or they supervised the youngest participants when needed, and returned this questionnaire to the researcher through the same media. However, when some parents reported that they don’t have the appropriate gadget to print the questionnaire, the google online tools for research was similarly sent to parents. Fielding out the questionnaires started in mid-April, when Luzon, (Philippines) including the National Capital Region (NCR), were in complete lockdown; it ended in June, 2020 when partial lock down in the same place was lifted.

Simple descriptive statistics was used in reporting the data, mostly in graphic presentations. Since non-standardized measurement was used, the processes involved were adapted from literature selecting only what were deemed appropriate with the data, without a specific reference of source. Data were analyzed through the following processes:

Analysis of Data

The questionnaire from the 200 participants generated about 22,000 raw data in words, (and few numbers).

These words were the participants’ expressions or descriptions of their knowledge, thoughts and feelings about the issues – COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown; how they handled or managed themselves during the lockdown, and the activities they did, and missed, or wished to do more with family. They also stated the communication media in their home.

Categorization and Coding of Responses

The expressions of participants on the issues were categorized according to similarity or relativity of concepts, terms, ideas or clues including Pilipino words which were not translated, these are presented in italics. Coding used, or putting the labels, was based on the main concepts found, such as about the self (participant), family events or affairs, and the participants’ different thoughts, feelings, concerns, and activities. A cluster of codes for a particular concept, say the coping mechanisms and some activities of participants, were found to be interrelated. These were compared between and within cases; terms which appeared almost the same in their concept or meaning were grouped together under one theme.

Developing Themes

Some themes, from a cluster of several codes, emerged in the initial tryout; finding the last themes although time consuming and quite resource-intensive, was achieved. After similar or related terms were coded, reviewed and clustered, which were likewise repeatedly analyzed and branded, four conclusive themes finally emerged.

Thematic Analysis

This last process was employed to capture the most important sentiments of participants thus, giving a clearer picture of their thoughts and feelings. These are: Theme 1 – Inward and Outward Fear and Sadness; Theme 2 – Mixed Positive and Negative Emotions About Lockdown; Theme 3 – Hope and Faith in God Expressed in Prayer; and Theme 4 – Family as a Stronghold of Support.

Graphic Presentations

There were multiple answers to individual issues hence, for brevity key words and phrases were categorized and presented in tables and figures.

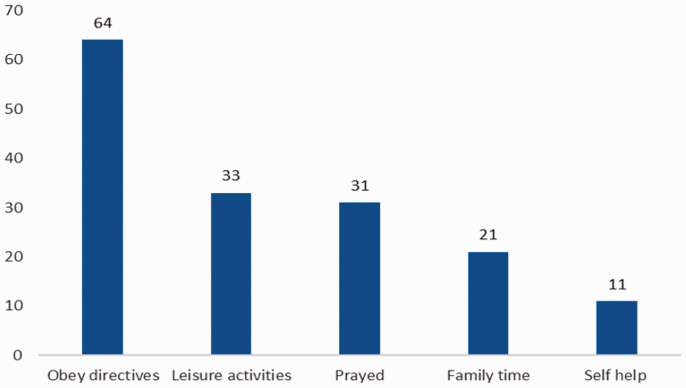

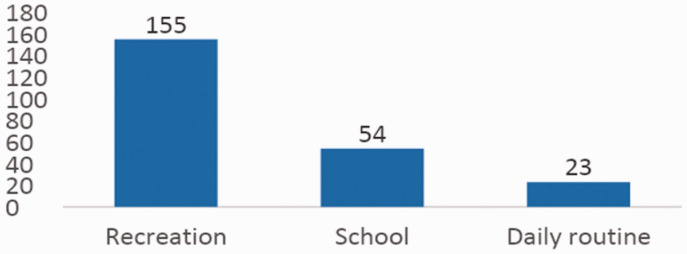

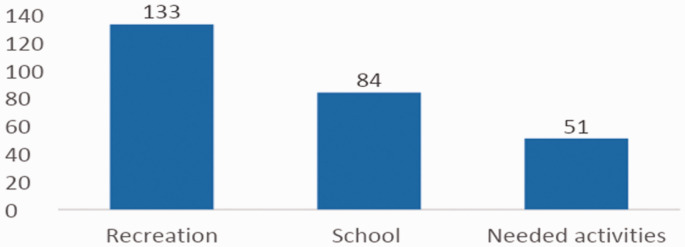

Table 1 shows the demographic data of participants; Table 2 reflects what they said about the issues: COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown; Table 3 reveals their thoughts and feelings about these issues; Table 4 contains the comments from the participants’ parents or guardians; and Table 5 presents the sources of information resources used by participants at home. Figure 1 demonstrates the participants’ coping behavior during lockdown; Figure 2 reflects the activities that participants did during lockdown; Figure 3 reveals what participants missed while confined at home; and Figure 4 shows what participants wished to do more with family while in lockdown.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 200).

Participants’ Response to the Item, ‘What Can You Say About COVID-19, Pandemic and Lockdown/Quarantine’ (N=200).

Thoughts and Feelings of Participants on COVID-19, Pandemic and Lockdown/Quarantine (N=200).

Comments From Parents or Guardians of Participants.

Participants’ Sources of Information.

Coping Mechanisms of Participants.

Activities of Participants During Lockdown/Quarantine.

Activities Participants Wished to Do More Together With Their.

What Participants Wished to Do More Together With Family.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participants from the elementary schools of the public and private institutions; the private sectors included colleges and universities, both coed and exclusive.

Participants’ Thoughts and Feelings

Most of participants’ expressions were in one-word terms, phrases, or brief statements. For brevity these were edited, or deleted, among these were I and I am, it is, the, there is/are, since, due to, and because. Similarly, the brief Filipino terms are presented in italics.

Parents/Guardians and Media

Table 4 contains the edited comments from the participants’ parents or guardians. Participants’ reported that they heard and learned about the issues – COVID-19, pandemic, and lock down – from different resources as shown on Table 5 .

Participants’ Coping Mechanisms

Participants employed various mechanisms to cope with COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown. Among these were: Obey government guidelines like stay at home to prevent getting infected, maghugas ng kamay at mag-alcohol, huwag na po dapat lalabas para di na magka-virus, listen to news, and support the front liners. They had leisure activities such as play with toys, games, pets, phone, gadgets, nagbabasa nalang po ako ng mga libro, and focus on hobbies. They do spiritual acts like pray not to be infected, n agpapray po para mawala ang covid, that it would end or find a solution, that it stops; and to have a normal life; lift and believe God will heal the world, and ask for His guidance, for family, kasama sila lolo at lola . They have the family and others from whom they ask questions, talk with different topics, follow their reminders and rules, or simply play with them. They play with siblings, toys, pets, and watch t.v.; occupied with hobbies with sisters and doggies, took time to hug Papa and family, stuffy toy, Tasha; talk/zoom meet with friends; spent time and call up cousins and grandparents. They also did some self-help means by keeping calm and staying positive, understanding the cause of fears, dealing with it pro-actively, trying to forget this, and not to feel sad but to be happy; made a COVID journal and wrote experiences. (Expressions of participants were edited for brevity, including Filipino words in italics.)

Participants’ Activities

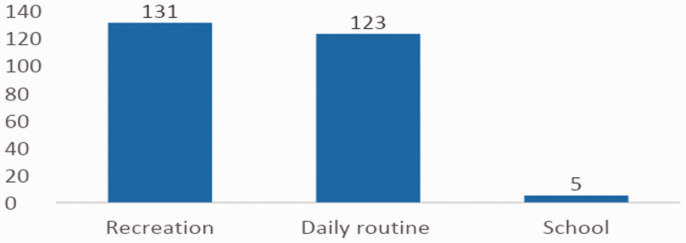

Participants gave multiple responses on the item how they spend the day during lockdown which were categorized into recreation, school and daily activities. Majority of participants engaged in activities for fun, enjoyment or amusement. These included playing, watching and doing arts and crafts alone and/or together with family members, relatives and friends. Playing included the use of gadgets for video and computer games, board games, toys and even pets. Watching were television movies, programs, and news. As for arts, stated were drawing, painting, and sketching; for crafts were beads and paper folding. School-related activities included doing assignments and exercises, reading and writing. Daily routine activities like eating, sleeping, personal hygiene, grooming, praying, and (virtual) mass were mentioned. Helping in household chores such as house cleaning, and helping in the kitchen, washing clothes, watering plants, alone or with family members, were also included.

Responses of participants were likewise grouped into recreation, school and needed activities. Majority missed doing recreational past times with their family, close relatives and friends like going to the mall, beaches, parks, restaurants, and also going on vacation. Many participants also missed school activities including teachers, classmates, friends, and learning new lessons. Participants missed doing outside needed activities like buying food, walking, going to the gym, and obligatory weekly church services, with the family.

Participants wished to do more with their family were grouped into recreation, daily routine and school. Recreation for fun and amusement included watching movies, playing board games, and other leisurely activities. Mentioned daily routine activities were doing household chores such as cleaning in the house, cooking, baking, watering the plants, among others. School-related activities were reading and doing home works.

Data clearly showed the thoughts and feelings of about 90% of participants who described their sentiments in negative, unkind and unpleasant terms, about the issues – COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown. They continue living and adjusting to the difficult condition, and expressed their varied emotions in a word, a phrase, or short narratives; employed self-made defenses; and engaged in multi-faceted activities alone or with family. Perhaps, all these behaviors and manifestations assuaged them from what may be described as a heavy emotional load for young children. Undoubtedly, the objectives of the study were strongly supported by the robust data.

The participants, confronted with daily uncharted events must have found a venue (the questionnaire) and expressed what they thought and felt about the issues ( Tables 2 and 3 ); provided self-prescribed measures and ways probably, to remain sane and normal ( Figure 1 ). The long, and what seems to be an indefinite duration of the lockdown, gave the participants the unplanned closer bonding with the family when they engaged in various leisure activities, hobbies and interests ( Figures 2 to 4 ).

The study which sought to find out the participants’ thoughts and feelings was achieved through an open-ended questionnaire where the responses were collated and summarized (in aforesaid Tables and Figures); and some statements were subjected to thematic analysis. The following overarching themes observed in the participants’ words created a clearer picture which captured how the participants were affected by the issues.

Theme 1 – Inward and Outward Fear and Sadness

An overarching theme that can be gathered from the responses can be worded as such: Inward and Outward Fear and Sadness. The terms ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ refer to the direction of movement of the emotions, or in other words, who these emotions are directed to – themselves or other people. These emotions are instinctive reactions to the current pandemic that the country and the world are currently facing, the younger members of our society are not spared. This is mitigated by the news of the rise of cases and deaths disseminated through multiple media – television, radio, websites, and social media ( Table 5 ).

“Very, very sad because people all over the world get sick”

“It is terrifying and stressful. I cannot go out for a walk, cannot even buy stuff like Nintendo switch games and clothes, and new white rubber shoes for my PE class.”

Although news has a positive impact in providing people with information and updates about the pandemic, this however, has an irrefutable negative effect on the mental health of viewers, including young children. A study by the University of Oxford examining mental health found that 19% of parents said that their children were worried the family would not have enough food and other essential items during the outbreak after news coverage of panic buying and empty supermarket shelves. Piercey This can also be seen in the responses of the participants where they mention what they see or hear on the news.

“I heard it from the radio and it kills people”

“ … , I have heard a lot in the news and also on what I see people kept on disobeying the government … ”

While mass media is necessary providing updates about the pandemic, limiting the exposure of these children may be beneficial for their emotional and mental health.

Moreover, these feelings of sadness and fear may also be viewed as Inward and Outward. The inward aspect is seen among participants who are afraid or feel sad for themselves. They fear that they may contract the virus and get sick.

“I felt scared to get infected and die early.”

“I am worried because there is no cure yet.”

They also appeared to be sad because of the lockdown. While still under quarantine, these participants were not able to do the things that they used to enjoy, specifically going outside the house.

“It means kids are not allowed to leave the home.”

“ … everybody stays at home, no more malls. No more visiting other houses and going to the groceries for me.”

“It’s not nice because we cannot go out. Too boring to be at home.”

On the other hand, the outward direction is shown in participants who expressed worry for those outside of themselves, such as their family members, friends, medical workers, and those who are impoverished. This shows their concern going beyond their own safety, even beyond their own family.

“I felt sad for the people who are suffering from the virus and for the families that lost a family member and especially for the front-liners that did their very best for the people to survive from the pandemic.”

“It makes me feel worried and scared for my family and relatives, myself and the front liners and everybody in the country and the world.”

“Because a lot of people or families are suffering during ECQ, because they don’t have funds to buy all their needs to survive.”

These emotions, moving inwardly or outwardly, was also observed in children of previous studies ( Pearcey et al., 2020 ). Needless to say, these emotions are felt by everyone who feels threatened for themselves and for others. Understandably, adults also experience these emotions – worry, anxiety, sadness, and fear, as the World Health Organization (2020) puts it:

“Children are likely to experiencing worry, anxiety and fear, and this can include the types of fears that are very similar to those experienced by adults, such as fear of dying, a fear of their relatives dying, or a dare of what it means to receive medical treatment.”

Theme 2 – Mixed Positive and Negative Emotions About Lockdown

Another theme that can be drawn from the participants’ responses, especially when asked about the lockdown, is the differences in the way that these participants feel or think about lockdown. There are participants who felt that the lockdown was an added stressor as they were unable to do the things they once did such as play outside with their friends, go out with their families, and go to school.

“It slows down everything. All of my outside activities stopped. I am stacked in the house because of the quarantined measures. It makes me sad on that part alone … ”

“This COVID-19 situation separated me physically from my friends in school, from my cousins, from the activities I normally do especially this summer break.”

However, some may conversely regard it as somewhat a blessing in disguise. They viewed the lockdown as a respite from school, an increased opportunity for play at home and time with family.

“ … but it’s really relaxing because we don’t have to go to school, and not being allowed to go to places means we can stay home more.”

“ Sad and also happy it’s weird. Sad because I can’t go out and see my friends especially my cousin … happy cause I get to rest.”

More importantly, some of the participants considered the lockdown for its very essence – to prevent the spread of the virus and personal protection. Interestingly, the responses showed a realization on the part of some participants, which was probably brought about by family members and mass media, about the importance of quarantine.

“At first, I felt annoyed for having to miss out on schoolwork and time with friends. But later, I have realized how important it was to keep all of us safe, specially the front liners.”

“It is a good decision of government to suppress the increase of infection.”

“This lockdown is our government’s way of controlling the spread of virus and avoiding unnecessary deaths. Although it can sometimes be a bummer to be on lockdown, I think it is a small price to pay for safety and good health.” “We need to obey the rules because it’s for our own protection and wellbeing.”

In summation, this theme shows that there are participants having mixed emotions about lockdown. This may not necessarily reflect the child’s values and priorities, but it may have implications in the type of support a parent or a family member can give to the child, as this support may be crucial in how their children would view the quarantine. As can be seen in their statements, the participants who knew the reason and importance of a quarantine viewed it in a more altruistic and positive way. Again, the role of family, as the children’s role model, teacher and comforter, especially during difficult times cannot be more emphasized.

Theme 3 – Hope and Faith in God Expressed in Prayer

From the responses it may be noted the repeated reference to prayer and God. The participants mentioned that prayer is a part of their daily routine – their own response to the pandemic. Some of them began praying, while others continued their prayer in increased frequency and apparent sincerity. They prayed not only for themselves, but for their families, friends, the front liners, and the rest of the world stricken with COVID. Going over their verbatim responses, many participants had the term ‘nagdadasal’, or praying to God, as an answer to the question of their reaction to the pandemic and the lockdown.

“It also helps to pray with your family and pray for God’s protection.”

“ … Praying at night to get over this crisis is always my routine before I go to bed.”

“I am not scared because I pray”.

“ … lift and believe God will heal the world .”

“I pray always to the Lord to protect me and my family and heal others who got affected by it..."

Children are regarded as the more helpless members of the family. They are very limited in terms of their capabilities, and this is especially true in this time. Parents and other adults achieve a sense of feeling useful during this pandemic by spending more time taking care of their family, buying more groceries and supplies, and donating to organizations which cater to the front liners or those who are need. These behaviors of parents may be taken by participants either positively – they become equally helpful and thoughtful- or negatively, they feel helpless and worry about not having enough and other resources, during the pandemic. Although they do social distancing, staying at home and practicing personal hygiene, participants worry and feel that they should do more. Consequently, some of these participants may have resorted to prayer as their way of helping out in this pandemic. It was perhaps that through their spirituality, some participants felt hopeful about the pandemic which would seem a dramatic change in mindset from worry and anxiety to hope for a soon-to-be brighter future for them.

“My feeling is that I’m hopeful that all of us will be able to fight the virus from spreading … ”

“My feeling is still to be hopeful and trust everyone that we can end the virus and heal a lot of people.”

Being a predominantly Catholic country, religion and spirituality plays a major role especially true during tough times in a person's life. Data shows that participants turn to prayer perhaps as a way to relieve their personal worry about themselves and others, and also making them feel hopeful.

Theme 4 – Family as a Stronghold of Support

Another theme that can be observed is the overwhelming sense of family bond and relationships. Being quarantined for months, and which may continue indefinitely, and the prohibition for senior citizens and younger children to go outside their homes have been a difficult experience for them (as can be seen in the 1st theme). However, this allows them to stay with their family members virtually every single day. This may be a downside for some participants, but for many of them, this strengthens their relationships.

“It’s a family bonding.”

“I felt happy because we get to spend time with our family but also sad becaushere are still people infected and dying because of Corona Virus.”

“I have more time with family .”

“ I miss going to school and seeing my friends and doing sports but I get to stay home and spend more time with my family.”

A vital factor for this development is the oneness of the family as the family goes through this difficult time together. Their physical closeness allows the parents to keep an eye on their children, and consequently, find time to explain for participants to understand what exactly they are going through, and together. This perhaps helped the participants ease their anxiety as they understood the virus better, and as they had their family members to support them through these extraordinary circumstances.

“I always try to understand the situation or cause of my fears and worries as my parents have taught me. Fear comes from not understanding. So, the more I understand the less I fear.”

“I felt scared to get infected and die early, but after reading and studying about it with my parents I have learned to understand the virus and how to maintain a healthier lifestyle.”

Scanning through their responses, most participants mentioned obeying what their parents told them to do; while staying together during lockdown, some parents took the chance and imparted knowledge about the issues to which participants expressed appreciation. The implications for family dynamics which appeared altered by the circumstances are seemingly more favorable to both parents and their children. Although the responsibilities of parents to care for their children in these times may double, or even triple, but doing so may lead to the further strengthening of relationships fostered in the functioning of the family as one unit amidst the crisis. Needless to say, the older members of the family are crucial in the child’s physical, mental and emotional well-being and development during times when a widespread virus limits them to stay together to a great extent (Piercey et al., 2020).

The comments from parents ( Table 4 ) should be given attention because they are the nearest, and maybe the only companion of the children during lockdown. Parents who participated in the Oxford University Study showed that after one month of lockdown, they reported an increase in their child’s emotional, behavioral and restless/attentional difficulties ( Pearcey et al., 2020 ).

Conclusions and Recommendations

This study have achieved its objectives when participants expressed their thoughts and emotions which were mostly hurting, unkind and unfriendly. They employed self-enhanced mechanisms to cope with the pandemic, and engaged in various activities alone or with family. Positive perspectives on forging relationships with others were noted.

Generally, the participants seemed to have gained the knowledge, or perceptions, of the issues – COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown/quarantine – through the media, parents, and others. Confronted with lockdown, participants kept themselves busy with different activities, alone or with family; these somehow assuaged their fear, boredom, sadness, anger, and other negative emotions. Data seemed to indicate that adjusting to social distancing, especially when they started missing their friends, school, and places, was difficult for most participants.

It is noteworthy that strengthening family ties and relations appeared as the consoling and positive consequence of the lockdown. Participants expressed the good and wonderful remarks for their family, making the family their holding power which probably helped managed their thoughts and feelings, withstood what seemed unpleasant circumstances, and bore the challenges which confronted their young life.

This exploration was confronted with limitations: The lockdown, although it motivated this investigation, was a big constraint when participants were unavailable if compared when they are in one school or location; and the lack of control on the place where the questionnaire was filled-up by participants. It was trust on the parents/guardians that the instituted precautionary measures (such as, not coaching or helping the participant in answering the questionnaire) were followed. Our regular meeting although virtually conducted in social media would still be much friendlier and informal when face-to-face while we discussed every step of the study thus, further enhancing camaraderie.

This study may not claim to be a novel piece of work for Filipino children in this age group but we declare that it is the first of its kind that we ventured on. It is our contribution to the literature on the Filipino children’s thoughts and feelings during a difficult time, and at this stage of their growth and development.

Armed with what appeared as rich and informative data, we recommend to develop strategies to assist children at the time of, or during, a critical period or disastrous event; that the participants be revisited say, after a year or two. It would be thought-provoking and challenging to find out how they will reminisce the impact of the experience during the pandemic and how this may have affected their young heart and mind. We consider it very important the need for more studies to determine the long-term effects of the lockdown on the life of young children specifically on their mental and emotional state, the quintessence of this paper. Our recommendations are encouraged by the articles of Gibbs et al. (2019) , Pearcey et al. (2020) , Riphagen et al. (2020) , and Strauss (2017). In addition probably, a three-generation of grandparents, parents and grandchildren may be taken as participant-companions in a study where lockdown has been enforced for say, four to six months, and find out how all were affected by the directive of staying home together, and provide support to reduce the risk of negative mental health ( Wang, 2020 ) .

Author Biographies

Lourdes Urbano Agbing Retired, University of the Philippines and Miriam College

Josephine Dionela Agapito Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Ann Marie Albano Baradi Project Manager, Miriam College, Quezon City, Philippines; Past President, Associationof Private Schools Administrators, Quezon City

M. Bernadette Camba Guzman, RGS Program Coordinator, Welcome House Good Shepherd Sisters, Crisis Intervention Center, Manila, Philippines

Clarissa Mariano Ligon College of Education, Miriam College

Arsenia Tuazon Lozano Principal, Basic Education DepartmentNational College of Business and ArtsQuezon City, Philippines

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Lourdes Urbano Agbing https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7814-9310

- Adigun A. (2020, June 26). COVID-19 disease in children is usually mild, fatalities rare, UK study says. ABC News. https://app.abcnews.go.com/Health/covid-19-disease-children-mild-fatalities-rare-uk/story?id=71462424

- British Medical Journal. (2020, April 02). Covid-19: four fifths of cases are asymptomatic, China figures indicate. The BMJ. https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1375 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- Crowder L. (2016, April 02). Hope despite hardship. Nepal Capstone. Center on Conflict and Development. https://hardin04.wixsite.com/nepalcapstone#!about/cjg9

- Gibbs L., Nursey J., Cook J., Ireton G., Alkemade N., Roberts M., Forbes D. (2019). Delayed disaster impacts on academic performance of primary school children. Child Development, 90(4), 1402–1412. 10.1111/cdev.13200 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearcey S., Shum A., Waite P., Patalay P., Creswell C. (2020, June 16). Changes in children and young people’s emotional and behavioral difficulties through lockdown. Emerging Minds. https://emergingminds.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CoSPACE-Report-4-June-2020.pdf

- Ramchandani P. (2020, April 11). Children and Covid-19. New Scientist . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7194712/ [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Riphagen S., Gomez X., Gonzalez-Martinez C., Wilkinson N., Theocharis P. (2020). Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10237), 1607–1608. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32386565 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Strauss V. (2017, September 12). The serious and long-lasting impact of disaster on schoolchildren. Analysis. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/09/11/the-serious-and-long-lasting-impact-of-disaster-on-schoolchildren/

- Tedros. A. (2020, April 13). WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–13-april-2020

- Wang G. (2020, June 1). Seven findings that can help people deal with COVID-19. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/06/covid-findings

- World Health Organization. (2020, March 01). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report 41. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200301-sitrep-41-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6768306d_2

- View on publisher site

- PDF (14.4 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Omengan’s photo essay shows three of the many stories of mental health battles, of struggling to stay afloat despite the inaccessibility of proper mental health services, which worsened due to the series of lockdowns in the Philippines.

This is what the Filipino people continue to face. As the country starts to feel the blow of the more transmissible COVID19 delta variant, the Department of Health tallied 14,249 new cases in a single day, based on their latest bulletin as of August 14, 2021.

In this essay, we engage with the call for Extraordinary Issue: Coronavirus, Crisis and Communication. Situated in the Philippines, we reflect on how COVID-19 has made visible the often-overlooked relationship between journalism and public health.

Tindi ng sakit ng COVID-19. Karamihan sa mga taong may impeksyon ng COVID-19 ay magkakaranas lamang ng hindi malalang sintomas at ganap na gagaling. Ngunit may ilang tao na mas maapektuhan ng sakit. Lahat tayo ay may papel na ginagampanan upang maprotektahan ang ating sarili at ang iba.

Filipinos helping Fellow Filipinos. By E photographer / Shutterstock. March 26th, 2020 by Juliene Guillermo. As COVID-19 strikes the Philippine nation, people rise together to counter it. At the forefront of the fight against the virus are our healthcare workers and various frontliners.

An esteemed overseas Filipino photographer calls on aspiring artists to pursue their passion, and put their talent to good use especially during amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

The best of Filipino self-reliance and resiliency in face of a lingering Covid-19 pandemic. Manuel Cayon. March 15, 2022. 5 minute read. In file photo: Homegrown entrepreneurs across the country throw their support behind the government’s “Buy Local, Patronize Local” drive amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

A daughter shares her story in the hope of sparing other families the same grief of losing loved ones to COVID-19.

Filipino Responses to COVID-19. Research documents Filipino panic responses to the global pandemic. Posted April 30, 2020 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina. Source: Photo by Graham Ruttan on...

explore thoughts and feelings of children on COVID-19, find out how they cope, and what they did during lockdown. It was total lockdown in Luzon, Philippines, April 2020 – when survey was conducted; pre-tested open-end questionnaire was administered to children who answered either by paper and pen, or through social media, with parents ...