Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

Published on 2 September 2022 by Kassiani Nikolopoulou . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Content validity evaluates how well an instrument (like a test) covers all relevant parts of the construct it aims to measure. Here, a construct is a theoretical concept, theme, or idea – in particular, one that cannot usually be measured directly.

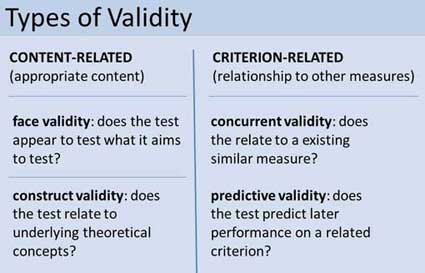

Content validity is one of the four types of measurement validity . The other three are:

- Face validity : Does the content of the test appear to be suitable for its aims?

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

Table of contents

Content validity examples, step-by-step guide: how to measure content validity, frequently asked questions about content validity.

Some constructs are directly observable or tangible, and thus easier to measure. For example, height is measured in inches. Other constructs are more difficult to measure. Depression, for instance, consists of several dimensions and cannot be measured directly.

Additionally, in order to achieve content validity, there has to be a degree of general agreement, for example among experts, about what a particular construct represents.

Research has shown that there are at least three different components that make up intelligence: short-term memory, reasoning, and a verbal component.

Construct vs. content validity example

It can be easy to confuse construct validity and content validity, but they are fundamentally different concepts.

Construct validity evaluates how well a test measures what it is intended to measure. If any parts of the construct are missing, or irrelevant parts are included, construct validity will be compromised. Remember that in order to establish construct validity, you must demonstrate both convergent and divergent (or discriminant) validity .

- Convergent validity shows whether a test that is designed to measure a particular construct correlates with other tests that assess the same construct.

- Divergent (or discriminant) validity shows you whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed unrelated. There should be little to no relationship between the scores of two tests measuring two different constructs.

On the other hand, content validity applies to any context where you create a test or questionnaire for a particular construct and want to ensure that the questions actually measure what you intend them to.

- High content validity. If your survey questions cover all dimensions of health needs – physical, mental, social, and environmental – your questionnaire will have high content validity.

- Low content validity. If most of your survey questions relate to the attitude of the study population towards the health services provided to them instead of to health needs , the results are no longer a valid measure of community health needs.

- Low construct validity. If some dimensions of health needs are left out, then the results may not give an accurate indication of the health needs of the community due to poor operationalisation of the concept.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Measuring content validity correctly is important – a high content validity score shows that the construct was measured accurately. You can measure content validity following the step-by-step guide below:

Step 1: Collect data from experts

Step 2: calculate the content validity ratio, step 3: calculate the content validity index.

Measuring content validity requires input from a judging panel of subject matter experts (SMEs). Here, SMEs are people who are in the best position to evaluate the content of a test.

For example, the expert panel for a school math test would consist of qualified math teachers who teach that subject.

For each individual question, the panel must assess whether the component measured by the question is ‘essential’, ‘useful’, but ‘not essential’, or ‘not necessary’ for measuring the construct.

The higher the agreement among panelists that a particular item is essential, the higher that item’s level of content validity is.

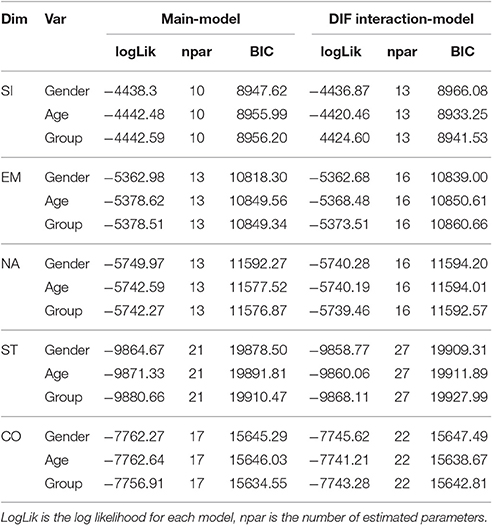

Next, you can use the following formula to calculate the content validity ratio (CVR) for each question:

Content Validity Ratio = (ne − N/2) / (N/2) where:

- ne = number of SME panelists indicating ‘essential’

- N = total number of SME panelists

The content validity ratio for the first question would be calculated as:

Using the same formula, you calculate the CVR for each question.

Note that this formula yields values which range from +1 to −1. Values above 0 indicate that at least half the SMEs agree that the question is essential. The closer to +1, the higher the content validity.

However, agreement could be due to coincidence. In order to rule that out, you can use the critical values table below. Depending on the number of experts in the panel, the content validity ratio (CVR) for a given question should not fall below a minimum value, also called the critical value.

| # of panelists | Critical value |

|---|---|

| 5 | 0.99 |

| 6 | 0.99 |

| 7 | 0.99 |

| 8 | 0.75 |

| 9 | 0.78 |

| 10 | 0.62 |

| 11 | 0.59 |

| 12 | 0.56 |

| 20 | 0.42 |

| 30 | 0.33 |

| 40 | 0.29 |

To measure the content validity of the entire test, you need to calculate the content validity index (CVI) . The CVI is the average CVR score of all questions in the test. Remember that values closer to 1 denote higher content validity.

To calculate the content validity index (CVI) of the entire test, you take the average of all the CVR scores of the seven questions.

Here, that would be:

Comparing the CVI with the critical value for a panel of 5 experts (0.99), you notice that the CVI is too low. This means that the test does not accurately measure what you intended it to. You decide to improve the questions with a low CVR, in order to get a higher CVI.

Face validity and content validity are similar in that they both evaluate how suitable the content of a test is. The difference is that face validity is subjective, and assesses content at surface level.

When a test has strong face validity, anyone would agree that the test’s questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure.

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test).

On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more systematic and relies on expert evaluation. of each question, analysing whether each one covers the aspects that the test was designed to cover.

A 4th grade math test would have high content validity if it covered all the skills taught in that grade. Experts(in this case, math teachers), would have to evaluate the content validity by comparing the test to the learning objectives.

A glossary is a collection of words pertaining to a specific topic. In your thesis or dissertation, it’s a list of all terms you used that may not immediately be obvious to your reader. In contrast, an index is a list of the contents of your work organised by page number.

Content validity shows you how accurately a test or other measurement method taps into the various aspects of the specific construct you are researching.

In other words, it helps you answer the question: “does the test measure all aspects of the construct I want to measure?” If it does, then the test has high content validity.

The higher the content validity, the more accurate the measurement of the construct.

If the test fails to include parts of the construct, or irrelevant parts are included, the validity of the instrument is threatened, which brings your results into question.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2022, October 10). What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 27 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/content-validity-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Kassiani Nikolopoulou

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is convergent validity | definition & examples, face validity | guide with definition & examples.

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

- What is content validity?

Last updated

8 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

When we discuss research accuracy, we use the term “validity.” Validity tells us how accurately a method measures what it has been deployed to measure.

There are four different types of validity: face validity, criterion validity , construct validity, and content validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

Content validity concerns how well a specific research instrument measures what it aims to measure. In this case, “construct” refers to a particular concept that is not directly measurable. Examples include justice, happiness, or beauty. Construct validity can be used to determine how accurately a test, experiment, or similar instrument measures the construct.

- When is content validity used?

Content validity is typically used to measure a test’s accuracy. The test in question would be used to measure constructs that are too complex to measure directly.

Some constructs, such as height or weight, are simple to measure quantifiably. But consider a concept like health. Some may consider health from a strictly physical perspective. Others believe good health requires high spiritual, physical, mental, emotional, and social levels.

Whether you define health according to one or several dimensions, each is comprised of multiple aspects that must be measured.

Take physical health as an example. Evaluating a person’s physical health might include assessing their medical history, weight, body composition, activity levels, diet, lifestyle, and sleep routines. A physician or medical researcher might also check for signs of temporary or chronic illness, injury, or substance abuse. Further, some evaluators may only be concerned with specific aspects of health or place more importance on certain aspects.

Content validity helps researchers understand just how precisely the instrument measures that specific construct. It’s crucial that researchers design tests that precisely define the construct they’re trying to measure, using the right attributes and characteristics.

- Content validity examples

The Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) is a well-known example of content validity. Designed and orchestrated by the College Board, the SAT is commonly used to measure college readiness and indicate how successful a student will be in college.

Multiple studies have shown a statistically significant correlation between a combination of good high school grades and SAT scores and first-year college grades. Accordingly, the SAT has been a standard part of the college admissions process for decades.

However, many critics have argued that the SAT doesn’t provide a sufficient gauge of college readiness. They noted design aspects that have led to performance disparities among specific groups of test takers. While the College Board has made changes, academics have conducted many studies concerning the SATs’ content validity. These have reaffirmed its value.

Another example of content validity involves the commonly used measure of obesity known as body mass index (BMI). This measure involves a relatively simple set of calculations that yield appropriate weight ranges for an individual relative to their height.

The healthcare industry uses BMI widely, but the measure has been criticized for how well it measures obesity. Since obesity is defined as an excess of body fat, BMI does not accurately classify heavily muscular individuals with low body fat whose BMI calculation places them in the obese category. Nor does it accurately gauge metabolic obesity (colloquially known as skinny fat), which can present just as many health risks as those who carry a visible, significant amount of visceral fat.

Academics have published numerous papers over the past few years examining BMI’s face, content, criterion, and construct validity regarding obesity.

- How to measure content validity

Measuring content validity takes some time and effort, but it is essential to ensure that the research you conduct or use is accurate.

To measure content validity, you’ll need to collect expert data, find the content validity ratio, and calculate the content validity index.

Collecting data from experts

First, you will need to find and assemble a group of experts in the research area you’re evaluating. You will need these subject matter experts (SMEs) to assess the content of the research instrument involved.

For accounting research, you might pull together a group of practicing accountants and accounting professors. If you’re gauging the content validity of a fitness test for a high school physical education test, you could assemble physical education teachers and experts in teaching and sports science.

These SMEs will evaluate the instrument on a three-point (one to three) scale, ranking each question on the questionnaire, test, or survey instrument as either “not necessary,” “useful, but not necessary,” or “essential.”

A question’s content validity is higher the more SMEs rank it as “essential.”

Finding the content validity ratio

Once you’ve gathered this initial data from the SMEs, you’ll calculate each question’s content validity ratio (CVR).

CVR = (Nₑ - N/2) / (N/2)

In this formula, Ne e refers to the number of SMEs who have indicated a question is essential. N equals the total number of participating SMEs.

When calculating the CVR, you’ll get answers ranging between - 1 (perfect disagreement) and +1 (perfect agreement). The closer a question’s CVR is to +1, the higher its content validity.

Now, SMEs may agree that a question is essential by coincidence. Ruling this out involves a critical values table. The critical values table for content validity measurements is below:

|

|

5 | 0.99 |

6 | 0.99 |

7 | 0.99 |

8 | 0.75 |

9 | 0.78 |

10 | 0.62 |

11 | 0.59 |

12 | 0.56 |

13 | 0.54 |

14 | 0.51 |

15 | 0.49 |

20 | 0.42 |

25 | 0.37 |

30 | 0.33 |

35 | 0.31 |

40 | 0.29 |

Calculating the content validity index

Once you’ve calculated the CVR for each question, you must find the entire instrument’s content validity. This measure is referred to as the content validity index (CVI). You can find the CVI by taking the average of all your CVRs .

When you have calculated the CVI, you’ll be left with a number between -1 and +1. However, this number on its own doesn’t tell you enough about the precision of your instrument. As with CVR, the closer to +1 your CVI is, the better—but you must also compare your CVI to the appropriate minimum value in your critical values table to determine how precise it is.

Let’s say you have a test with a CVI of 0.27. If you used a panel of six SMEs, you’d find that the minimum value in your critical values table is 0.99. This value is much higher than your CVI, meaning your test isn’t very precise at all. You want your CVI to be higher than the minimum value in your critical values table to attain an appropriate level of precision.

- Content validity vs. face validity

Some people confuse face validity with content validity, as the two terms tackle the same aspect of instrument measurement. However, face validity involves a preliminary evaluation of whether an instrument appears to be appropriate for measuring a construct. Content validity, on the other hand, evaluates the instrument’s precision in measuring a construct.

Evaluating face validity involves examining whether an instrument is appropriate for its intended purpose at the surface level. For example, a survey designed to measure postpartum maternal health that exclusively contains questions about fast food consumption would lack face validity. In contrast, face validity would be high if the survey included questions about a woman’s physical and mental health, diet and exercise, work-life balance, and social engagement.

What is an example of a content validity test?

You can often find tests with content validity in everyday life. Common examples include driver’s license exams, standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT, professional licensing exams such as the NCLEX 9 for nurses, and more.

What is content validity in qualitative research?

Content validity helps researchers determine the measurement efficacy of quantitative and qualitative research instruments.

For example, suppose you were conducting research about the perspectives of baby boomers on today’s political discourse. You would measure how comprehensively and effectively your survey captured the possible range of opinions. Subject matter experts would calculate the survey’s content validity index in the same way they would for a quantitative research instrument.

What is the difference between validity and content validity?

Validity (or measurement validity) generally tells you about a measurement method’s accuracy. Content validity helps you understand whether your method, such as a test or survey, fully represents the concept or idea it’s measuring.

What is the difference between content validity and construct validity?

Construct validity examines how effectively an instrument measures what it is designed to measure relative to other instruments. It is composed of convergent validity and divergent validity. Convergent validity illustrates if a correlation exists between the instrument in question and other instruments that measure the same construct. Divergent validity shows that the instrument is not correlated with other instruments designed to measure different phenomena.

By contrast, content validity is an intrinsic assessment of how well an instrument measures what it’s intended to measure.

How do you quantify content validity?

Content validity is measured in quantifiable terms. Calculate the content validity for each instrument question and the content validity index using their formulas.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Content Validity: Definition, Examples & Measuring

By Jim Frost Leave a Comment

What is Content Validity?

Content validity is the degree to which a test or assessment instrument evaluates all aspects of the topic, construct, or behavior that it is designed to measure. Do the items fully cover the subject? High content validity indicates that the test fully covers the topic for the target audience. Lower results suggest that the test does not contain relevant facets of the subject matter.

For example, imagine that I designed a test that evaluates how well students understand statistics at a level appropriate for an introductory college course. Content validity assesses my test to see if it covers suitable material for that subject area at that level of expertise. In other words, does my test cover all pertinent facets of the content area? Is it missing concepts?

Learn more about other Types of Validity and Reliability vs. Validity .

Content Validity Examples

Evaluating content validity is crucial for the following examples to ensure the tests assess the full range of knowledge and aspects of the psychological constructs:

- A test to obtain a license, such as driving or selling real estate.

- Standardized testing for academic purposes, such as the SAT and GRE.

- Tests that evaluate knowledge of subject area domains, such as biology, physics, and literature.

- A scale for assessing anger management.

- A questionnaire that evaluates coping abilities.

- A scale to assess problematic drinking.

How to Measure Content Validity

Measuring content validity involves assessing individual questions on a test and asking experts whether each one targets characteristics that the instrument is designed to cover. This process compares the test against its goals and the theoretical properties of the construct. Researchers systematically determine whether each item contributes, and that no aspect is overlooked.

Factor Analysis

Advanced content validity assessments use multivariate factor analysis to find the number of underlying dimensions that the test items cover. In this context, analysts can use factor analysis to determine whether the items collectively measure a sufficient number and type of fundamental factors. If the measurement instrument does not sufficiently cover the dimensions, the researchers should improve it. Learn more in my Guide to Factor Analysis with an Example .

Content Validity Ratio

For this overview, let’s look at a more intuitive approach.

Most assessment processes in this realm obtain input from subject matter experts. Lawshe* proposed a standard method for measuring content validity in psychology that incorporates expert ratings. This approach involves asking experts to determine whether the knowledge or skill that each item on the test assesses is “essential,” “useful, but not necessary,” or “not necessary.”

His method is essentially a form of inter-rater reliability about the importance of each item. You want all or most experts to agree that each item is “essential.”

Lawshe then proposes that you calculate the content validity ratio (CVR) for each question:

- N e = Number of “essentials” for an item.

- N = Number of experts.

Using this formula, you’ll obtain values ranging from -1 (perfect disagreement) to +1 (perfect agreement) for each question. Values above 0 indicate that more than half the experts agree.

However, it’s essential to consider whether the agreement might be due to chance. Don’t worry! Critical values for the ratio can help you make that determination. These critical values depend on the number of experts. You can find them here: Critical Values for Lawshe’s CVR .

The content validity index (CVI) is the mean CVR for all items and it provides an overall assessment of the measurement instrument. Values closer to 1 are better.

Finally, CVR distinguishes between necessary and unnecessary questions, but it does not identify missing facets.

Lawshe, CH, A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity, Personnel Psychology , 1975, 28, 563-575.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

Comments and questions cancel reply.

Content Validity

- Reference work entry

- pp 1261–1262

- Cite this reference work entry

- Shayna Rusticus 3

3761 Accesses

19 Citations

Content validity refers to the degree to which an assessment instrument is relevant to, and representative of, the targeted construct it is designed to measure.

Description

Content validation, which plays a primary role in the development of any new instrument, provides evidence about the validity of an instrument by assessing the degree to which the instrument measures the targeted construct (Anastasia, 1988 ). This enables the instrument to be used to make meaningful and appropriate inferences and/or decisions from the instrument scores given the assessment purpose (Messick, 1989 ; Moss, 1995 ). All elements of the instrument (e.g., items, stimuli, codes, instructions, response formats, scoring) that can potentially impact the scores obtained and the interpretations made should be subjected to content validation. There are three key aspects of content validity: domain definition, domain representation, and domain relevance (Sireci, 1998a ). The first aspect, domain...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Anastasia, A. (1988). Psychological testing (6th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing.

Google Scholar

DeVellis, R. F. (1991). Scale development: Theory and applications . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Haynes, S. N., Richard, D. C. S., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychological Assessment, 7 , 238–247.

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13–103). New York: American Council on Education.

Mosier, C. I. (1947). A critical examination of the concepts of face validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 7 , 191–205.

Moss, P. A. (1995). Themes and variations in validity theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 14 , 5–13.

Murphy, K. R., & Davidshofer, C. O. (1994). Psychological testing: Principles and applications (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Sireci, S. G. (1998a). Gathering and analyzing content validity data. Educational Assessment, 5 , 299–321.

Sireci, S. G. (1998b). The construct of content validity. Social Indicators Research, 45 , 83–117.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Evaluation Studies Unit, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Shayna Rusticus

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shayna Rusticus .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC, Canada

Alex C. Michalos

(residence), Brandon, MB, Canada

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Rusticus, S. (2014). Content Validity. In: Michalos, A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_553

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_553

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-0752-8

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-0753-5

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Validity In Psychology Research: Types & Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology research, validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement tool accurately measures what it’s intended to measure. It ensures that the research findings are genuine and not due to extraneous factors.

Validity can be categorized into different types based on internal and external validity .

The concept of validity was formulated by Kelly (1927, p. 14), who stated that a test is valid if it measures what it claims to measure. For example, a test of intelligence should measure intelligence and not something else (such as memory).

Internal and External Validity In Research

Internal validity refers to whether the effects observed in a study are due to the manipulation of the independent variable and not some other confounding factor.

In other words, there is a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables .

Internal validity can be improved by controlling extraneous variables, using standardized instructions, counterbalancing, and eliminating demand characteristics and investigator effects.

External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other settings (ecological validity), other people (population validity), and over time (historical validity).

External validity can be improved by setting experiments more naturally and using random sampling to select participants.

Types of Validity In Psychology

Two main categories of validity are used to assess the validity of the test (i.e., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.): Content and criterion.

- Content validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement represents all aspects of the intended content domain. It assesses whether the test items adequately cover the topic or concept.

- Criterion validity assesses the performance of a test based on its correlation with a known external criterion or outcome. It can be further divided into concurrent (measured at the same time) and predictive (measuring future performance) validity.

Face Validity

Face validity is simply whether the test appears (at face value) to measure what it claims to. This is the least sophisticated measure of content-related validity, and is a superficial and subjective assessment based on appearance.

Tests wherein the purpose is clear, even to naïve respondents, are said to have high face validity. Accordingly, tests wherein the purpose is unclear have low face validity (Nevo, 1985).

A direct measurement of face validity is obtained by asking people to rate the validity of a test as it appears to them. This rater could use a Likert scale to assess face validity.

For example:

- The test is extremely suitable for a given purpose

- The test is very suitable for that purpose;

- The test is adequate

- The test is inadequate

- The test is irrelevant and, therefore, unsuitable

It is important to select suitable people to rate a test (e.g., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.). For example, individuals who actually take the test would be well placed to judge its face validity.

Also, people who work with the test could offer their opinion (e.g., employers, university administrators, employers). Finally, the researcher could use members of the general public with an interest in the test (e.g., parents of testees, politicians, teachers, etc.).

The face validity of a test can be considered a robust construct only if a reasonable level of agreement exists among raters.

It should be noted that the term face validity should be avoided when the rating is done by an “expert,” as content validity is more appropriate.

Having face validity does not mean that a test really measures what the researcher intends to measure, but only in the judgment of raters that it appears to do so. Consequently, it is a crude and basic measure of validity.

A test item such as “ I have recently thought of killing myself ” has obvious face validity as an item measuring suicidal cognitions and may be useful when measuring symptoms of depression.

However, the implication of items on tests with clear face validity is that they are more vulnerable to social desirability bias. Individuals may manipulate their responses to deny or hide problems or exaggerate behaviors to present a positive image of themselves.

It is possible for a test item to lack face validity but still have general validity and measure what it claims to measure. This is good because it reduces demand characteristics and makes it harder for respondents to manipulate their answers.

For example, the test item “ I believe in the second coming of Christ ” would lack face validity as a measure of depression (as the purpose of the item is unclear).

This item appeared on the first version of The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and loaded on the depression scale.

Because most of the original normative sample of the MMPI were good Christians, only a depressed Christian would think Christ is not coming back. Thus, for this particular religious sample, the item does have general validity but not face validity.

Construct Validity

Construct validity assesses how well a test or measure represents and captures an abstract theoretical concept, known as a construct. It indicates the degree to which the test accurately reflects the construct it intends to measure, often evaluated through relationships with other variables and measures theoretically connected to the construct.

Construct validity was invented by Cronbach and Meehl (1955). This type of content-related validity refers to the extent to which a test captures a specific theoretical construct or trait, and it overlaps with some of the other aspects of validity

Construct validity does not concern the simple, factual question of whether a test measures an attribute.

Instead, it is about the complex question of whether test score interpretations are consistent with a nomological network involving theoretical and observational terms (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955).

To test for construct validity, it must be demonstrated that the phenomenon being measured actually exists. So, the construct validity of a test for intelligence, for example, depends on a model or theory of intelligence .

Construct validity entails demonstrating the power of such a construct to explain a network of research findings and to predict further relationships.

The more evidence a researcher can demonstrate for a test’s construct validity, the better. However, there is no single method of determining the construct validity of a test.

Instead, different methods and approaches are combined to present the overall construct validity of a test. For example, factor analysis and correlational methods can be used.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity is a subtype of construct validity. It assesses the degree to which two measures that theoretically should be related are related.

It demonstrates that measures of similar constructs are highly correlated. It helps confirm that a test accurately measures the intended construct by showing its alignment with other tests designed to measure the same or similar constructs.

For example, suppose there are two different scales used to measure self-esteem:

Scale A and Scale B. If both scales effectively measure self-esteem, then individuals who score high on Scale A should also score high on Scale B, and those who score low on Scale A should score similarly low on Scale B.

If the scores from these two scales show a strong positive correlation, then this provides evidence for convergent validity because it indicates that both scales seem to measure the same underlying construct of self-esteem.

Concurrent Validity (i.e., occurring at the same time)

Concurrent validity evaluates how well a test’s results correlate with the results of a previously established and accepted measure, when both are administered at the same time.

It helps in determining whether a new measure is a good reflection of an established one without waiting to observe outcomes in the future.

If the new test is validated by comparison with a currently existing criterion, we have concurrent validity.

Very often, a new IQ or personality test might be compared with an older but similar test known to have good validity already.

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity assesses how well a test predicts a criterion that will occur in the future. It measures the test’s ability to foresee the performance of an individual on a related criterion measured at a later point in time. It gauges the test’s effectiveness in predicting subsequent real-world outcomes or results.

For example, a prediction may be made on the basis of a new intelligence test that high scorers at age 12 will be more likely to obtain university degrees several years later. If the prediction is born out, then the test has predictive validity.

Cronbach, L. J., and Meehl, P. E. (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin , 52, 281-302.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1943). Manual for the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory . New York: Psychological Corporation.

Kelley, T. L. (1927). Interpretation of educational measurements. New York : Macmillan.

Nevo, B. (1985). Face validity revisited . Journal of Educational Measurement , 22(4), 287-293.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Validity is a fundamental concept in research, referring to the extent to which a test, measurement, or study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. Ensuring validity is crucial as it determines the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings.

Research Validity

Research validity pertains to the accuracy and truthfulness of the research. It examines whether the research truly measures what it claims to measure. Without validity, research results can be misleading or erroneous, leading to incorrect conclusions and potentially flawed applications.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several strategies:

- Clear Operational Definitions : Define variables clearly and precisely.

- Use of Reliable Instruments : Employ measurement tools that have been tested for reliability.

- Pilot Testing : Conduct preliminary studies to refine the research design and instruments.

- Triangulation : Use multiple methods or sources to cross-verify results.

- Control Variables : Control extraneous variables that might influence the outcomes.

Types of Validity

Validity is categorized into several types, each addressing different aspects of measurement accuracy.

Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to the degree to which the results of a study can be attributed to the treatments or interventions rather than other factors. It is about ensuring that the study is free from confounding variables that could affect the outcome.

External Validity

External validity concerns the extent to which the research findings can be generalized to other settings, populations, or times. High external validity means the results are applicable beyond the specific context of the study.

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a test or instrument measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. It involves ensuring that the test is truly assessing the concept it claims to represent.

Content Validity

Content validity examines whether a test covers the entire range of the concept being measured. It ensures that the test items represent all facets of the concept.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity assesses how well one measure predicts an outcome based on another measure. It is divided into two types:

- Predictive Validity : How well a test predicts future performance.

- Concurrent Validity : How well a test correlates with a currently existing measure.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the extent to which a test appears to measure what it is supposed to measure, based on superficial inspection. While it is the least scientific measure of validity, it is important for ensuring that stakeholders believe in the test’s relevance.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial because it directly affects the credibility of research findings. Valid results ensure that conclusions drawn from research are accurate and can be trusted. This, in turn, influences the decisions and policies based on the research.

Examples of Validity

- Internal Validity : A randomized controlled trial (RCT) where the random assignment of participants helps eliminate biases.

- External Validity : A study on educational interventions that can be applied to different schools across various regions.

- Construct Validity : A psychological test that accurately measures depression levels.

- Content Validity : An exam that covers all topics taught in a course.

- Criterion Validity : A job performance test that predicts future job success.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, the methodology section should include discussions about validity. Here, you explain how you ensured the validity of your research instruments and design. Additionally, you may discuss validity in the results section, interpreting how the validity of your measurements affects your findings.

Applications of Validity

Validity has wide applications across various fields:

- Education : Ensuring assessments accurately measure student learning.

- Psychology : Developing tests that correctly diagnose mental health conditions.

- Market Research : Creating surveys that accurately capture consumer preferences.

Limitations of Validity

While ensuring validity is essential, it has its limitations:

- Complexity : Achieving high validity can be complex and resource-intensive.

- Context-Specific : Some validity types may not be universally applicable across all contexts.

- Subjectivity : Certain types of validity, like face validity, involve subjective judgments.

By understanding and addressing these aspects of validity, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their studies, leading to more reliable and actionable results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Construct Validity – Types, Threats and Examples

Internal Validity – Threats, Examples and Guide

Reliability – Types, Examples and Guide

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Content Validity – Measurement and Examples

Alternate Forms Reliability – Methods, Examples...

METHODS article

What do you think you are measuring a mixed-methods procedure for assessing the content validity of test items and theory-based scaling.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt, Klagenfurt, Austria

- 2 Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA

The valid measurement of latent constructs is crucial for psychological research. Here, we present a mixed-methods procedure for improving the precision of construct definitions, determining the content validity of items, evaluating the representativeness of items for the target construct, generating test items, and analyzing items on a theoretical basis. To illustrate the mixed-methods content-scaling-structure (CSS) procedure, we analyze the Adult Self-Transcendence Inventory, a self-report measure of wisdom (ASTI, Levenson et al., 2005 ). A content-validity analysis of the ASTI items was used as the basis of psychometric analyses using multidimensional item response models ( N = 1215). We found that the new procedure produced important suggestions concerning five subdimensions of the ASTI that were not identifiable using exploratory methods. The study shows that the application of the suggested procedure leads to a deeper understanding of latent constructs. It also demonstrates the advantages of theory-based item analysis.

Introduction

Construct validity is an important criterion of measurement validity. Broadly put, a scale or test is valid if it exhibits good psychometric properties (e.g., unidimensionality) and measures what it is intended to measure (e.g., Haynes et al., 1995 ; de Von et al., 2007 ). The 2014 Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing ( American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014 ) state that test content is one of four interrelated sources of validity, the other ones being internal structure, response processes, and relations to other constructs. While elaborate empirical and statistical procedures exist for evaluating at least internal structure and relations to other constructs, the validity of test content is harder to ensure and to quantify. As Webb (2006) wrote in his chapter in the Handbook of Test Development, “Identifying the content of a test designed to measure students' content knowledge and skills is as much an art as it is a science. The science of content specification draws on conceptual frameworks, mathematical models, and replicable procedures. The art of content specification is based on expert judgments, writing effective test items, and balancing the many tradeoffs that have to be made” (p. 155). This may be even more the case when the construct at hand is not a form of knowledge or skill, where responses can be coded as right or wrong, but a personality or attitudinal construct where responses are self-judgments. How can we evaluate the validity of the items that form a test or questionnaire?

The development and evaluation of tests and questionnaires is a complex and lengthy process. The phases of this process have been described, for example, in the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing by the American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education (2014) , or by the Educational Testing Service (2014) . A good overview is given by Lane et al. (2016) . These standards require, for example, that the procedures for selecting experts and collecting their judgments should be fully described, or that the potential for effects of construct-irrelevant characteristics on the measure should be minimized. Here, we describe a concrete procedure for evaluating and optimizing the content validity of existing and new measures in a theory-based way that is consistent with the requirements of the various standards. That is, we do not focus on ways to develop new test items in a theory-consistent way, which are described at length in the literature (e.g., Haladyna and Rodriguez, 2013 ; Lane et al., 2016 ), but on how to evaluate existing items in an optimal, unbiased way.

Content validity ( Rossiter, 2008 ) is defined as “the degree to which elements of an assessment instrument are relevant to a representative of the targeted construct for a particular assessment purpose” ( Haynes et al., 1995 , p. 238). Content validity includes several aspects, e.g., the validity and representativeness of the definition of the construct, the clarity of the instructions, linguistic aspects of the items (e.g., content, grammar), representativeness of the item pool, and the adequacy of the response format. The higher the content validity of a test, the more accurate is the measurement of the target construct (e.g., de Von et al., 2007 ). While we all know how important content validity is, it tends to receive little attention in assessment practice and research (e.g., Rossiter, 2008 ; Johnston et al., 2014 ). In many cases, test developers assume that content validity is represented by the theoretical definition of the construct, or they do not discuss content validity at all. At the same time, content validity is a necessary condition for other aspects of construct validity. A test or scale that does not really cover the content of the construct it intends to measure will not be related to other constructs or criteria in the way that would be expected for the respective construct.

In a seminal paper, Haynes et al. (1995) emphasized the importance of content validity and gave an overview of methods to assess it. After the publication of this paper, consideration of content validity in assessment studies increased for a short time, especially in the journal where the authors published their work. However, a brief literature search in journals relevant to the topic shows that content validity is still rarely referred to and even less often analyzed systematically. Between 1995 and 2015, “content validity” was mentioned in one article published in Assessment , in 44 articles in Psychological Assessment , where the paper by Haynes et al. (1995) was published, in 22 articles in Educational Assessment , and in seven articles in European Journal of Psychological Assessment . Currently, content validity is rarely mentioned in psychological journals but receives special attention in other disciplines such as nursing research (e.g., de Von et al., 2007 ).

Methods to Evaluate Content Validity

Several approaches to evaluate content validity have been described in the literature. One of the first procedures was probably the Delphi method, which was used since 1940 by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as a systematic method for technical predictions (see Sackman, 1974 ; Hasson and Keeney, 2011 ). The Delphi method, which is predominantly used in medical research, is a structural iterative communication technique where experts assess the importance of characteristics, symptoms, or items for a target construct (e.g., Jobst et al., 2013 ; Kikukawa et al., 2014 ). In the first round, each expert individually rates the importance of symptoms/items for the illness/construct of interest. In the second round, the experts receive summarized results based on the first round and can make further comments or revise their answers of the first round. The process stops when a previously defined homogeneity criterion is achieved.

Most procedures currently used to investigate content validity are based on the quantitative methods described by Lawshe (1975) or Lynn (1986) , who also provided numerical content validity indices (see Sireci, 1998 ). All these methods, as well as the Delphi-method, are based on expert judgments where a number of experts rate the relevance of the items for the construct on 4- to 10-point scales or using percentages ( Haynes et al., 1995 ) or assign the items to the dimensions of the construct (see Moore and Benbasat, 2014 ). Then, indicators of average relevance are calculated. This can be done by calculating simple average percentages (e.g., if the number of experts is low) or by using a cut-off value (usually 70–80%) to decide whether an item measures the respective construct (e.g., Sireci, 1998 ; Newman et al., 2013 ). In other cases, as mentioned above, a content validity index ( Lawshe, 1975 ; Lynn, 1986 ; Polit and Beck, 2006 ; Polit et al., 2007 ; Zamanzadeh et al., 2014 ) is estimated for individual items (e.g., the proportion of agreement among experts concerning scale assignment) or for the whole scale (e.g., the proportion of items that are judged as content valid by all experts).

There exists, however, no systematical procedure that could be used as a general guideline for the evaluation of content validity (cf. Newman et al., 2013 ). Also, Johnston et al. (2014) recently called for a satisfactory, transparent, and systematical method to assess content validity. They described a quantitative “discriminant content validity” (DCV) approach that assesses not only the relevance of items for the construct, but also whether discriminant constructs play an important role for response behavior. In this method, experts evaluate how relevant each item is for the construct. After that, it is statistically determined whether each item measures the construct of interest. This procedure is well-suited for determining content validity, but the authors argued that it is not possible to determine the representativeness of the items for the target construct, as claimed by Haynes et al. (1995) . Furthermore, it involves only purely quantitative analyses and does not utilize the potential of qualitative approaches. For example, Newman et al. (2013) illustrated the advantages of mixed-method procedures for evaluating content validity or even validity in general. They specifically mention two advantages: the possibility to improve validity and reliability of the instrument, and the resulting new insights into the nature of the target construct. They introduced the Table of Specification (ToS), which requires experts, among other things, to assign items to constructs using percentages. Additionally, the experts can estimate the overall representativeness of the whole set of items for the target construct and add comments concerning this topic. The ToS is wide applicable and a good possibility to evaluate content validity, but it does not allow the evaluation of overlaps between different constructs and does not connect the results to the subsequent psychometric analysis of items. Such a connection does not only improve the measurement of content validity, it also allows for theory-based item analysis. That is, expert judgments about item content can be used to derive specific hypotheses about item fit, which can then be tested statistically.

Theory-Based Item Analysis

Scale items are often developed on the basis of theoretical definitions of the construct, and sometimes they are even analyzed for content validity in similar ways as described above, but after this step, item selection is usually purely empirical. A set of items is completed by a sample of participants, and response frequencies and indicators of reliability such as item-total correlations are used to select the best-functioning items. Rossiter (2008) criticized that at the end of such purely empirical item-selection processes, the remaining items often measure only one narrow aspect of the target construct. In such cases, it would perhaps be possible to retain the diversity of the original items by constructing subscales. Some authors, such as Gittler (1986) and Koller et al. (2012) , have long highlighted the importance of theory-based analysis. For example, Koller and Lamm (2015) showed that a theory-based analysis of items measuring cognitive empathy yielded important information concerning scale dimensionality. In this study, the authors derived hypotheses about item-specific violations of the Rasch model from expert judgments about item content. The expert judgements suggested that the perspective-taking subscale could theoretically be subdivided into the dimensions “to understand both sides” and “to put oneself in the position of another person.” Psychometric analysis confirmed this assumption, which is also in accordance with recent findings from social neuroscience (e.g., Singer and Lamm, 2009 ). In sum, approaches from neuropsychology, item response theory, and qualitative item-content analysis were integrated into a more valid assessment of cognitive empathy.

Goals of the Study

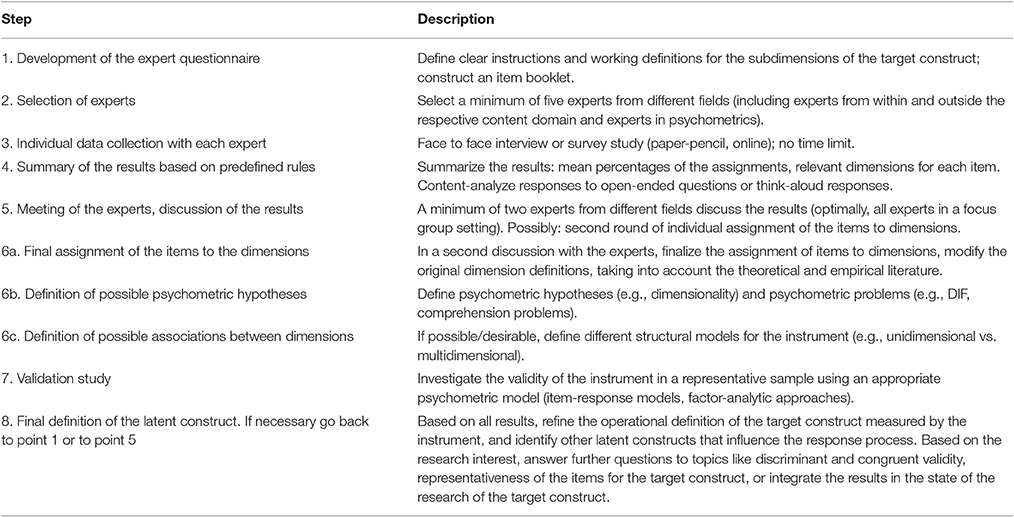

The main aim of this paper is to introduce the Content-Scaling-Structure (CSS) procedure, a mixed-methods approach for analyzing and optimizing the content validity of a questionnaire or scale. The approach is suitable for many research questions in the realm of content validity, such as the formulation of a-priori hypotheses for a theory-based item analysis, the refinement of the definition of a target construct, including possible differentiation into subdimensions, the evaluation of representativeness of items for the target construct, or the investigation of the influence of related constructs on the items of a scale. Thus, the proposed CSS procedure combines the qualitative and quantitative investigation of content validity with an approach for the theory-based psychometric analysis of items. Furthermore, it can lead to a better understanding of the latent construct itself, a better embedding of empirical findings in the research literature, and to a higher construct validity of the instrument in general. We present a general description of the procedure (see Table 1 ) and describe several possible adaptations. The proposed procedure can be adapted in several ways to examine different types of latent constructs (e.g., competencies vs. traits, less vs. more complex constructs). In summary, the proposed CSS procedure fulfills the demand for a systematical and transparent procedure for the estimation of content validity, includes the advantages of mixed-methodologies, and allows researchers not only to evaluate content validity, but also to perform theory-based item analyses. Although the CSS procedure was developed independently of the ToS ( Newman et al., 2013 ), there are several similarities. However, the CSS-procedure is not limited to the non-psychometric analysis of content validity, it also includes psychometric analyses and the integration of the non-psychometric and psychometric parts. Accordingly, the first part of the CSS-procedure could be viewed as an adaption and extension of the ToS.

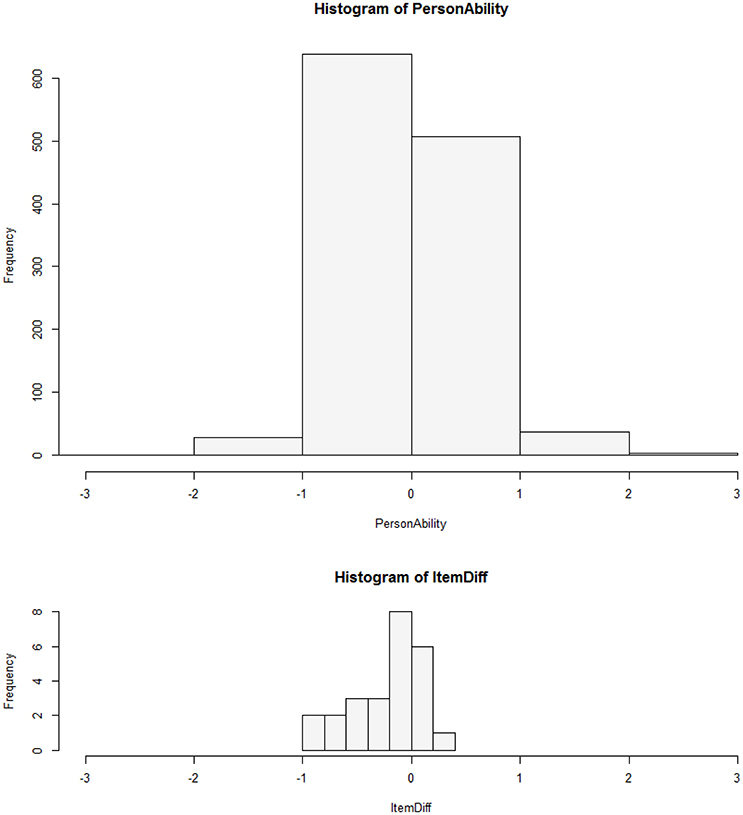

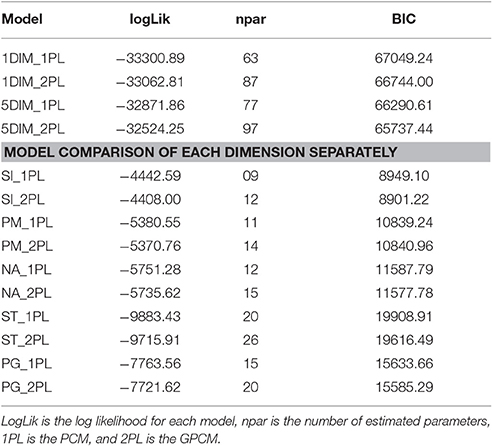

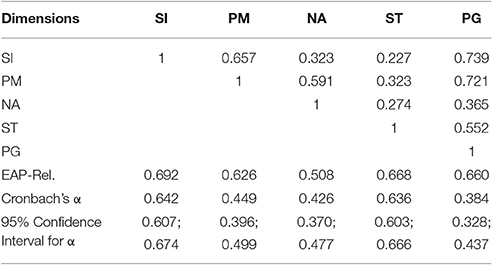

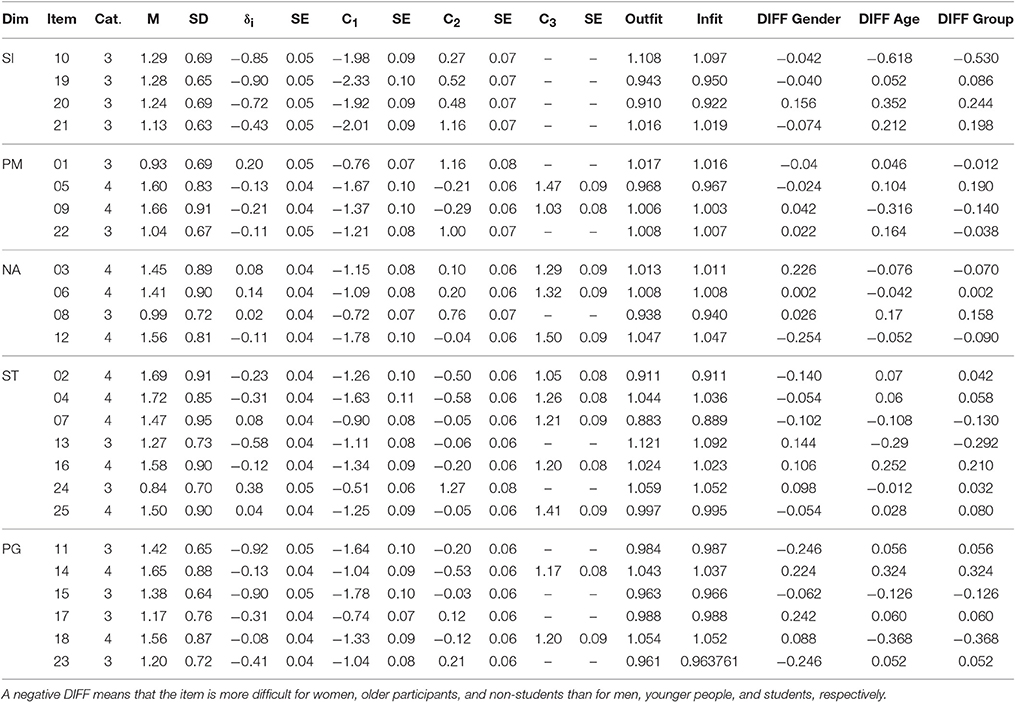

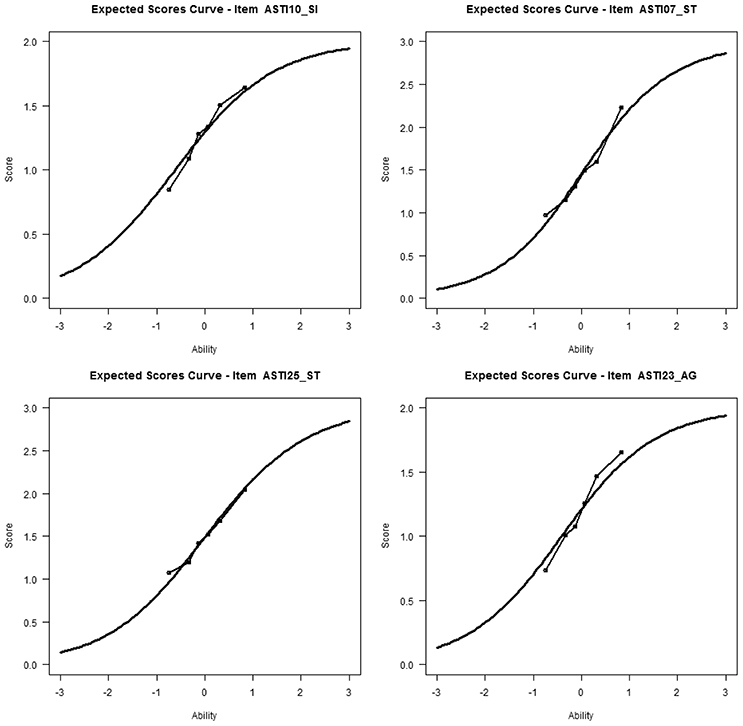

Table 1. General schedule for the Content-Scaling-Structure (CSS) procedure .

To demonstrate our procedure here, we use the Adult Self-Transcendence Inventory (ASTI), a self-report scale measuring the complex target construct of wisdom. In the first part of the study, an expert panel analyzed the content of the ASTI items with respect to the underlying constructs in order to investigate dimensionality, identify potential predictors of differential item functioning, and analyze the appropriateness of the definition of the construct for the questionnaire. In the second part, data from a sample of 1215 participants were used to evaluate the items using multidimensional item response theory models, building upon the results of the first part. It is not at all mandatory to use item response modeling for such analyses; other psychometric methods, such as exploratory or confirmatory factor analyses, may also be employed, although our impression is that item response models are particularly well-suited to test specific hypotheses about item functioning. At the end, the results and the proposed procedure are discussed and a new definition of the target construct that the ASTI measures is given.

Before we describe the CSS-procedure in detail, we introduce the topic of measuring wisdom and the research questions for the presented study. After that, the CSS procedure is described and illustrated using the ASTI as an example.

Measuring Wisdom with the Adult Self-Transcendence Inventory

Wisdom is a complex and multifaceted construct, and after 30 years of psychological wisdom research, measuring it in a reliable and valid way is still a major challenge ( Glück et al., 2013 ). In this study, we used the ASTI, a self-report measure that conceptualizes wisdom as self-transcendence ( Levenson et al., 2005 ). The idea that self-transcendence is at the core of wisdom was first brought forth by the philosopher Trevor Curnow (1999) in an analysis of the common elements of wisdom conceptions across different cultures. Curnow identified four general principles of wisdom: self-knowledge, detachment, integration, and self-transcendence. Levenson et al. (2005) suggested to consider these principles as stages in the development of wisdom.

Self-knowledge is awareness of the sources of one's sense of self. The sense of self arises in the context of roles, achievements, relationships, and beliefs. Individuals high in self-knowledge have developed awareness of their own thoughts and feelings, attitudes, and motivations. They are also aware of aspects that do not agree with their ideal of who they would like to be.

Individuals high in non-attachment are aware of the transience and provisional nature of the external things, relationships, roles, and achievements that contribute to our sense of self. They know that these things are not essential parts of the self but observable, passing phenomena. This does not mean that they do not care for their relationships—on the contrary, non-attachment increases openness to and acceptance of others: individuals who are less identified with their own wishes, motives, thoughts, and feelings are better able to perceive, and care about, the needs and feelings of others.

Integration is the dissolution of separate “inner selves.” Different, contradictory self-representations or motives are no longer in conflict with each other or with the person's ideal self, but accepted as part of the person. This means that defense mechanisms that protect self-worth against threats from undesirable self-aspects are no longer needed.

Self-transcendent individuals are detached from external definitions of the self. They know and accept who they are and therefore do not need to focus on self-enhancement in their interaction with others. For this reason, they are able to dissolve rigid boundaries between themselves and others, truly care about others, and feel that they are part of a greater whole. Levenson et al. (2005) argue that self-transcendence in this sense is at the core of wisdom.

Levenson et al. (2005) developed a first version of the ASTI to measure these four dimensions. That original version consisted of 18 items with a response scale that asked for changes over the last 5 years rather than for participants' current status. This approach turned out to be suboptimal, however, and a revised version was developed that consists of 34 items with a more common response scale ranging from 1 (“disagree strongly”) to 4 (“agree strongly”). Some items were reworded from Tornstam's (1994) gerotranscendence scale, others were newly constructed by the test authors in order to broaden the construct. The majority of the items are related to one of the four dimensions identified by Curnow (1999) . They refer to inner peace independent of external things, feelings of unity with others and nature, joy in life, and an integrated sense of self. Ten of the items were included to measure alienation as a potential opposite of wisdom.

In a study including wisdom nominees as well as control participants, Glück et al. (2013) used a German-language version of the revised ASTI. The scale was translated into German and back-translated. One of the items (“Whatever I do to others, I do to myself”) was difficult to translate into German because it could have two different meanings (item 34: doing something (good) for others and oneself, or item 35: doing something (bad) to others and oneself). After consultation with the scale author, M. R. Levenson, both translations were retained in the German scale, resulting in a total of 35 items. In study by Glück et al. (2013) , the ASTI had the highest amount of shared variance with three other measures of wisdom, which suggests that it may indeed tap core aspects of wisdom. Reliability was satisfactory (Cronbach's α = 0.83), but factor analyses using promax rotation suggested that the ASTI might be measuring more than one dimension. The factor loadings did not suggest a clear structure representing Curnow's four dimensions, however. Scree plots suggested either one factor (accounting for only 21.7% of the variance) or three factors (38.5%). The first factor in the three-factor solution comprised five items describing the factor of self-transcendence (feeling one with nature, feeling as part of a greater whole, engaging in quiet contemplation), but the other two factors included only two or three items each and did not really correspond with the subfacets proposed by the scale authors. Thus, factor-analytically, the structure of the ASTI was not very clear. As the scale had not been systematically constructed to include specific subscales, there was no basis for a confirmatory factor analysis, and given the exploratory results it seems doubtful that such an analysis would have rendered clear results.

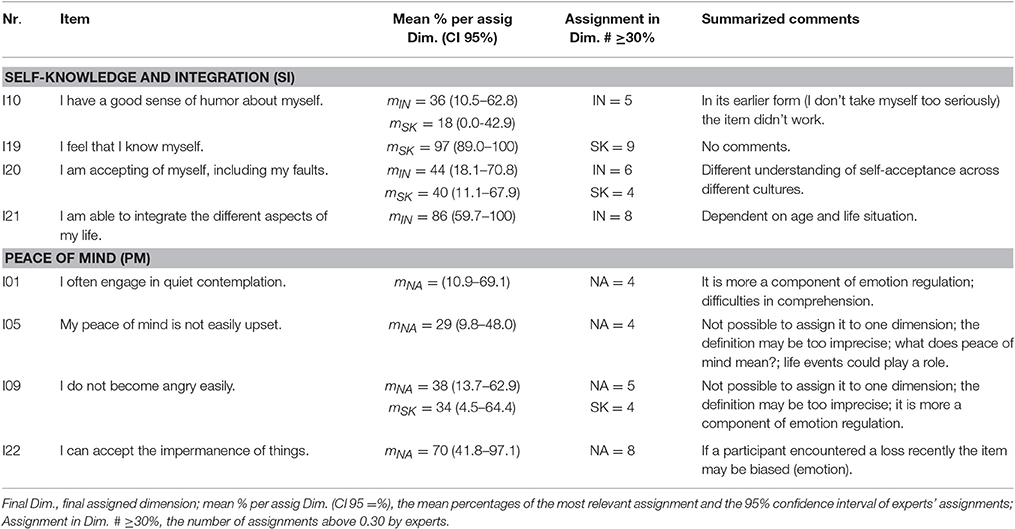

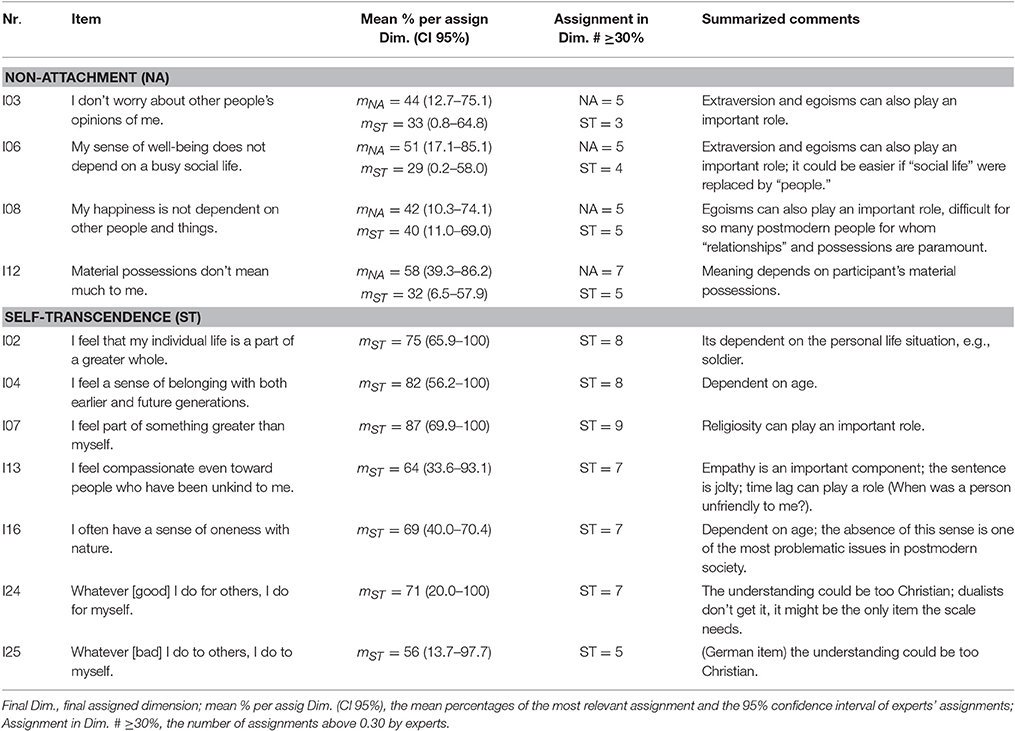

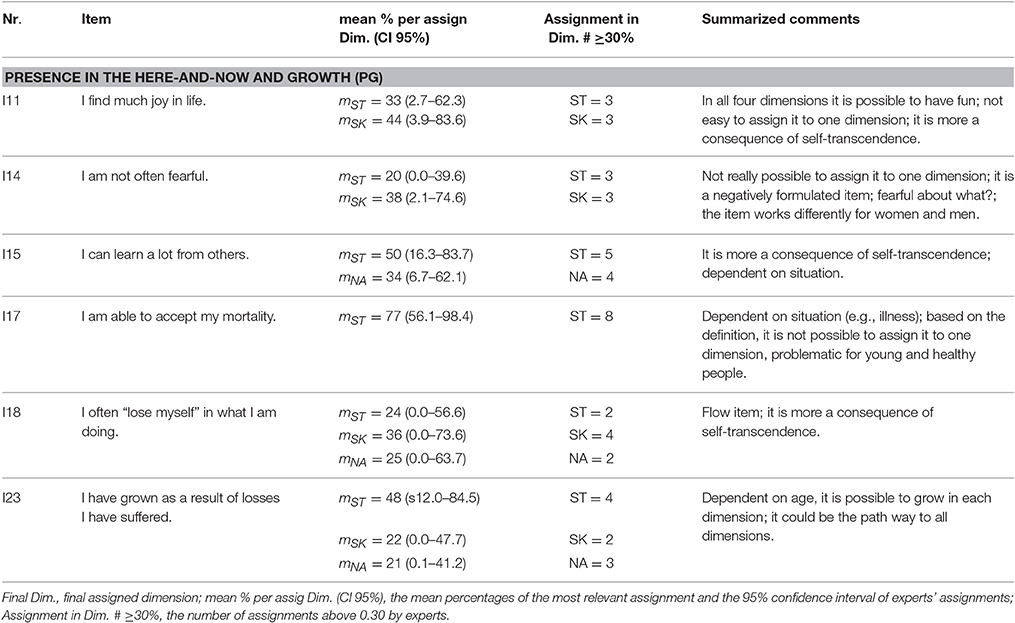

In the current study, we used the CSS procedure to gain insights about the structure of the scale, with the goal of identifying possible subscales. We only analyzed the 24 items measuring self-transcendence, excluding the 10 alienation items. Tables 3A – C include all analyzed items. Before the point by point description of the CSS Procedure, the research questions for the investigation of the ASTI are described.

Description and Application of the Content-Scaling-Structure Procedure

As the study design is intended to be a template for other studies, we first present a point-by-point description of the steps in Table 1 . In general, detailed descriptions of the procedure for assigning items to scales are important elements for the transparency of studies, especially as they offer the possibility to reanalyze and compare results across different studies (e.g., Johnston et al., 2014 ).

The research questions for the current study were as follows.

• Which items of the ASTI fulfill the requirement of content validity? The theoretical background of the ASTI describes a multidimensional, complex construct, and it is not obvious for all items to which dimension(s) they pertain. In addition, item responses may be influenced by other, related constructs that the ASTI is not intended to tap. Thus, we investigated experts' views on the relation of the items to the dimensions of the ASTI and to related constructs. The results of this analysis were also expected to show whether all dimensions of the ASTI are well-represented by the items, i.e., whether enough items are included to assess each dimension.

• How sufficient is the definition of the four-factor model underlying the ASTI? In earlier studies using content-dimensionality scaling, we have repeatedly found that the exercise of assigning items to dimensions and discussing our assignments has enabled us to rethink the definitions of the constructs themselves, identify conceptual overlaps between dimensions, and find that certain aspects were missing in a definition or did not fit into it. In other cases, we found that a construct was too broadly defined and needed to be divided into sub-constructs. In this vein, it is also important to consider whether other, related constructs may affect the responses to some items.

• Do the expert judgments suggest hypotheses for theory-based item analysis? The expert judgments are interesting not only with respect to the dimensionality of the ASTI. Other relevant psychometric issues include potential predictors of differential item functioning, comprehensibility of items, and too strong or too imprecise item formulations.

• To what extent are the theory-based assignments of items to dimensions supported by psychometric analyses? The ultimate goal of the study was to identify unidimensional subscales of the ASTI that would include as many of the items as possible and make theoretical as well as empirical sense. In earlier studies, we have repeatedly found that subscales that were identified in a theory-based way remained highly stable in cross-validations with independent samples, whereas subscales determined in a purely empirical way did not.

Development of the Expert Questionnaire: Instruction, Definitions, and Item Booklet

Independent of whether the research question of interest concerns the construction of a new measurement instrument, the evaluation of an existing measurement, or evaluating the representativeness of the items for the target construct, the first step is to lay out the definition of the target construct in a sufficiently comprehensive way (e.g., by a systematical review). That is, all relevant dimensions of the target construct should be defined in such a way that there is no conceptual overlap between them. Because the goal of the current study was to investigate the items and definitions of the ASTI and not the representativeness of the items for the construct of wisdom, we used the four levels of self-transcendence (self-knowledge, non-attachment, integration, and self-transcendence) as defined above.

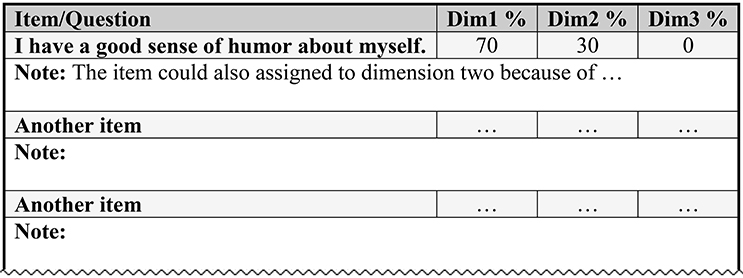

The second step is the generation of the questionnaire for the expert ratings based on the definitions of the target dimensions and the items. It includes a clear written instruction, the definitions of each subdimension, and an item booklet (see Figure 1 ) with the items in random order (i.e., not ordered by subdimension or content).

Figure 1. A fictive example of an item-booklet .

In the present study, the experts were first instructed to carefully read the definitions of the four dimensions underlying the ASTI shown above. Then they should read each item and use percentages to assign each item to the four dimensions: if an item tapped just one dimension, they should write “100%” into the respective column, if an item tapped more than one dimension they should split the 100% accordingly. For example, an item might be judged as measuring 80% self-transcendence and 20% integration. It is also possible to “force” experts to assign each item to only one dimension. This might be useful for re-evaluating an item assignment produced in earlier CSS rounds. As a first step, however, we believe that this kind of assignment could lead to a loss of valuable psychometric information about the items and increase the possibility of assignment errors.

If the experts felt that an item was largely measuring something other than the four dimensions, they should not fill out the percentages but make a note in an empty space below each item. They were also asked to note down any other thoughts or comments in that space. In addition, they were asked two specific questions: (1) “Do you think the item could be difficult to understand? If yes, why?,” and (2) “Do you think the item might have a different meaning for certain groups of people (e.g., men vs. women, younger vs. older participants, participants from different professional fields, or levels of education)? If yes, why?” The responses to these last questions allowed us to formulate a-priori hypotheses about differential item functioning (DIF; e.g., Holland and Wainer, 1993 ; see Section Testing Model Fit).

Selection of Experts

We recommend to recruit at least five experts (cf. Haynes et al., 1995 ): (1) at least two individuals with high levels of scientific and/or applied knowledge and experience concerning the construct of interest and related constructs, and (2) at least two individuals with expertise in test construction and psychometrics, who evaluate the items from a different perspective than content experts, so that their answers may be particularly helpful for theory-based item analysis. In addition, depending on the construct of interest, it may be useful to include laypersons, especially individuals from the target population (e.g., patients for a measure of a psychiatric construct). A higher number of experts allows for a better evaluation of the consistency of their judgments, increases the reliability and validity of the results, and allows the calculation of content validity indices. However, a higher number of experts can also increase the complexity of the results. In any case, the quality and diversity of the experts may be more important than their number.

In the present study, nine experts (seven women and two men) participated. Because the interest of the study was to validate the items of the ASTI, all experts were psychologists; five were mainly experts in the field of wisdom research and related fields (including the second and third author), and four were mainly experts of test psychology and assessment in different research fields (including the first author). All experts worked with the German version of the ASTI, except for the second author who used the original English version. In the present study, the experts were invited by email and the questionnaire was sent to them as an RTF document.

Individual Data Collection with Each Expert

The experts filled out the questionnaire individually and without time limits.

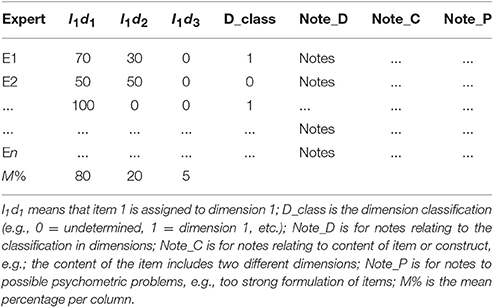

Summary of the Results Based on Predefined Rules

Next, the responses of the experts were summarized according to pre-defined rules. As Table 2 shows, we produced one summarizing table for each item. In this table, the percentages provided by the experts were averaged. In addition, we counted how many experts assigned each item to each dimension. Finally, the notes provided by the experts were sorted into three categories: notes concerning dimension assignment, item or dimension content, and psychometric issues.

Table 2. Example of summarized results for the discussion of final assignments .

Of course, these three categories are only examples, other categories are also possible. This qualitative part of the study can offer theoretical insights about the target construct as well as the individual items.

The last row of Table 2 contains the average percentages for each dimension across all experts. These values allow for first insights concerning dimension assignments. For example, the mean values might be d 1 = 50%, d 2 = 30%, d 3 = 10%, d 4 = 10%. A cutoff value can be used to determine which dimensions are important concerning the item. Choice of the cutoff value depends on the research aims: if the goal is to select items that measure only one subcomponent of a clearly and narrowly defined construct, a cutoff of 80% may be useful. This would mean that the experts agree substantially that each item very clearly taps one and only one of the dimensions involved. Newman et al. (2013) , for example, wrote that 80% agreement among experts is a typical rule of thumb for sufficient content validity. If the goal is to inspect the functioning of a scale measuring a broader, more vaguely defined construct, lower cutoff values may be useful. In addition to setting a cutoff, it may also be important to define rules for dealing with items that have relevant percentages on more than one subdimension. Our experience is that simply discarding all such items may mean discarding important aspects of the construct. It may be more helpful to consider alternative ways of dividing the scale into subcomponents. Even if an item has a high average assignment on only one dimension, it may still be worthwhile to check whether some experts assigned it strongly to another dimension. Thus, it is important to not only look at the averages, but to inspect the whole table for each item. In addition, if several rounds of expert evaluations are performed, the cutoff could be set higher from round to round.

In the current case, as the goal was not to select items but to gain information about an existing scale, we used a much lower cutoff criterion of 0.30 to determine which dimension(s) experts considered as most fitting for each item. We then presented the results, in an aggregated form, to a subgroup of the experts with the goal redefining and perhaps differentiating the dimensions to allow for a clearer assignment of items. Thus, the number of experts who assigned the item to the most prominent dimension with a percentage of at least the cutoff value was an indicator of homogeneity of the experts' views (see Tables 3A – C , column 4), similar to the classical content validity index (see Polit and Beck, 2006 ).

Table 3A. Results of the final assignment of the ASTI items .

Table 3B. Results of the final assignment of the ASTI items .

Table 3C. Results of the final assignment of the ASTI items .

Expert Meeting: Discussion of the Results