- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Graphical Abstracts and Tidbit

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About American Journal of Hypertension

- Editorial Board

- Board of Directors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- AJH Summer School

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Clinical management and treatment decisions, hypertension in black americans, pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in black americans.

- < Previous

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Suzanne Oparil, Case study, American Journal of Hypertension , Volume 11, Issue S8, November 1998, Pages 192S–194S, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00195-2

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Ms. C is a 42-year-old black American woman with a 7-year history of hypertension first diagnosed during her last pregnancy. Her family history is positive for hypertension, with her mother dying at 56 years of age from hypertension-related cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, both her maternal and paternal grandparents had CVD.

At physician visit one, Ms. C presented with complaints of headache and general weakness. She reported that she has been taking many medications for her hypertension in the past, but stopped taking them because of the side effects. She could not recall the names of the medications. Currently she is taking 100 mg/day atenolol and 12.5 mg/day hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), which she admits to taking irregularly because “... they bother me, and I forget to renew my prescription.” Despite this antihypertensive regimen, her blood pressure remains elevated, ranging from 150 to 155/110 to 114 mm Hg. In addition, Ms. C admits that she has found it difficult to exercise, stop smoking, and change her eating habits. Findings from a complete history and physical assessment are unremarkable except for the presence of moderate obesity (5 ft 6 in., 150 lbs), minimal retinopathy, and a 25-year history of smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes per day. Initial laboratory data revealed serum sodium 138 mEq/L (135 to 147 mEq/L); potassium 3.4 mEq/L (3.5 to 5 mEq/L); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 19 mg/dL (10 to 20 mg/dL); creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.35 to 0.93 mg/dL); calcium 9.8 mg/dL (8.8 to 10 mg/dL); total cholesterol 268 mg/dL (< 245 mg/dL); triglycerides 230 mg/dL (< 160 mg/dL); and fasting glucose 105 mg/dL (70 to 110 mg/dL). The patient refused a 24-h urine test.

Taking into account the past history of compliance irregularities and the need to take immediate action to lower this patient’s blood pressure, Ms. C’s pharmacologic regimen was changed to a trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril, 5 mg/day; her HCTZ was discontinued. In addition, recommendations for smoking cessation, weight reduction, and diet modification were reviewed as recommended by the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). 1

After a 3-month trial of this treatment plan with escalation of the enalapril dose to 20 mg/day, the patient’s blood pressure remained uncontrolled. The patient’s medical status was reviewed, without notation of significant changes, and her antihypertensive therapy was modified. The ACE inhibitor was discontinued, and the patient was started on the angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan, 50 mg/day.

After 2 months of therapy with the ARB the patient experienced a modest, yet encouraging, reduction in blood pressure (140/100 mm Hg). Serum electrolyte laboratory values were within normal limits, and the physical assessment remained unchanged. The treatment plan was to continue the ARB and reevaluate the patient in 1 month. At that time, if blood pressure control remained marginal, low-dose HCTZ (12.5 mg/day) was to be added to the regimen.

Hypertension remains a significant health problem in the United States (US) despite recent advances in antihypertensive therapy. The role of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is well established. 2–7 The age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in non-Hispanic black Americans is approximately 40% higher than in non-Hispanic whites. 8 Black Americans have an earlier onset of hypertension and greater incidence of stage 3 hypertension than whites, thereby raising the risk for hypertension-related target organ damage. 1 , 8 For example, hypertensive black Americans have a 320% greater incidence of hypertension-related end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 80% higher stroke mortality rate, and 50% higher CVD mortality rate, compared with that of the general population. 1 , 9 In addition, aging is associated with increases in the prevalence and severity of hypertension. 8

Research findings suggest that risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, particularly the role of blood pressure, may be different for black American and white individuals. 10–12 Some studies indicate that effective treatment of hypertension in black Americans results in a decrease in the incidence of CVD to a level that is similar to that of nonblack American hypertensives. 13 , 14

Data also reveal differences between black American and white individuals in responsiveness to antihypertensive therapy. For instance, studies have shown that diuretics 15 , 16 and the calcium channel blocker diltiazem 16 , 17 are effective in lowering blood pressure in black American patients, whereas β-adrenergic receptor blockers and ACE inhibitors appear less effective. 15 , 16 In addition, recent studies indicate that ARB may also be effective in this patient population.

Angiotensin-II receptor blockers are a relatively new class of agents that are approved for the treatment of hypertension. Currently, four ARB have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, and valsartan. Recently, a 528-patient, 26-week study compared the efficacy of eprosartan (200 to 300 mg/twice daily) versus enalapril (5 to 20 mg/daily) in patients with essential hypertension (baseline sitting diastolic blood pressure [DBP] 95 to 114 mm Hg). After 3 to 5 weeks of placebo, patients were randomized to receive either eprosartan or enalapril. After 12 weeks of therapy within the titration phase, patients were supplemented with HCTZ as needed. In a prospectively defined subset analysis, black American patients in the eprosartan group (n = 21) achieved comparable reductions in DBP (−13.3 mm Hg with eprosartan; −12.4 mm Hg with enalapril) and greater reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP) (−23.1 with eprosartan; −13.2 with enalapril), compared with black American patients in the enalapril group (n = 19) ( Fig. 1 ). 18 Additional trials enrolling more patients are clearly necessary, but this early experience with an ARB in black American patients is encouraging.

Efficacy of the angiotensin II receptor blocker eprosartan in black American with mild to moderate hypertension (baseline sitting DBP 95 to 114 mm Hg) in a 26-week study. Eprosartan, 200 to 300 mg twice daily (n = 21, solid bar), enalapril 5 to 20 mg daily (n = 19, diagonal bar). †10 of 21 eprosartan patients and seven of 19 enalapril patients also received HCTZ. Adapted from data in Levine: Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study, in Programs and abstracts from the 1st International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism, September 28–October 1, 1997, London, UK.

00195-2/2/m_ajh.192S.f1.jpeg?Expires=1715912260&Signature=m2JuurBni9XVjiybM3wXE401VWu4HNWdtD79r0atsyyKUC2aP3ObV-PT7Is78Qblcdrt5EPN3x3KfsCiJGsSTx1mEEBJokzNSQnsRxO6y2rP0wQwOub0kjziZp1wW8sr5aXAZrePCbZcYswK5-Yao-wojv7yn3Z-hiQU2mAD-oiytEMnDwMZft~WXpzxZTF5VOaj1DuXeJ~gldf0LKbtdHDOtvytG7ywcwd4cPMULAVxXSHMeX9JQJAaLqQ2Cr2Q9NefpOeccUKUQU94nY6f0sUAiPI5RlZ93CzskWmJkCf2gEv307Dt~DhaOFE6xPs38RP-HEa285lZ0X1ADKGhcg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Approximately 30% of all deaths in hypertensive black American men and 20% of all deaths in hypertensive black American women are attributable to high blood pressure. Black Americans develop high blood pressure at an earlier age, and hypertension is more severe in every decade of life, compared with whites. As a result, black Americans have a 1.3 times greater rate of nonfatal stroke, a 1.8 times greater rate of fatal stroke, a 1.5 times greater rate of heart disease deaths, and a 5 times greater rate of ESRD when compared with whites. 19 Therefore, there is a need for aggressive antihypertensive treatment in this group. Newer, better tolerated antihypertensive drugs, which have the advantages of fewer adverse effects combined with greater antihypertensive efficacy, may be of great benefit to this patient population.

1. Joint National Committee : The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure . Arch Intern Med 1997 ; 24 157 : 2413 – 2446 .

Google Scholar

2. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg . JAMA 1967 ; 202 : 116 – 122 .

3. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg . JAMA 1970 ; 213 : 1143 – 1152 .

4. Pooling Project Research Group : Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to the incidence of major coronary events: Final report of the pooling project . J Chronic Dis 1978 ; 31 : 201 – 306 .

5. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program: I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension . JAMA 1979 ; 242 : 2562 – 2577 .

6. Kannel WB , Dawber TR , McGee DL : Perspectives on systolic hypertension: The Framingham Study . Circulation 1980 ; 61 : 1179 – 1182 .

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : The effect of treatment on mortality in “mild” hypertension: Results of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program . N Engl J Med 1982 ; 307 : 976 – 980 .

8. Burt VL , Whelton P , Roccella EJ et al. : Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991 . Hypertension 1995 ; 25 : 305 – 313 .

9. Klag MJ , Whelton PK , Randall BL et al. : End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men: 16-year MRFIT findings . JAMA 1997 ; 277 : 1293 – 1298 .

10. Neaton JD , Kuller LH , Wentworth D et al. : Total and cardiovascular mortality in relation to cigarette smoking, serum cholesterol concentration, and diastolic blood pressure among black and white males followed up for five years . Am Heart J 1984 ; 3 : 759 – 769 .

11. Gillum RF , Grant CT : Coronary heart disease in black populations II: Risk factors . Heart J 1982 ; 104 : 852 – 864 .

12. M’Buyamba-Kabangu JR , Amery A , Lijnen P : Differences between black and white persons in blood pressure and related biological variables . J Hum Hypertens 1994 ; 8 : 163 – 170 .

13. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program: mortality by race-sex and blood pressure level: a further analysis . J Community Health 1984 ; 9 : 314 – 327 .

14. Ooi WL , Budner NS , Cohen H et al. : Impact of race on treatment response and cardiovascular disease among hypertensives . Hypertension 1989 ; 14 : 227 – 234 .

15. Weinberger MH : Racial differences in antihypertensive therapy: evidence and implications . Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1990 ; 4 ( suppl 2 ): 379 – 392 .

16. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC et al. : Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men: A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo . N Engl J Med 1993 ; 328 : 914 – 921 .

17. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC for the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Department of Veterans Affairs single-drug therapy of hypertension study: Revised figures and new data . Am J Hypertens 1995 ; 8 : 189 – 192 .

18. Levine B : Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study , in Programs and abstracts from the first International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism , September 28 – October 1 , 1997 , London, UK .

19. American Heart Association: 1997 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update . American Heart Association , Dallas , 1997 .

- hypertension

- blood pressure

- african american

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1941-7225

- Copyright © 2024 American Journal of Hypertension, Ltd.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 6: 10 Real Cases on Hypertensive Emergency and Pericardial Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Niel Shah; Fareeha S. Alavi; Muhammad Saad

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Clinical Symptoms

- Diagnostic Evaluation

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Management of Hypertensive Encephalopathy

A 45-year-old man with a 2-month history of progressive headache presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, visual disturbance, and confusion for 1 day. He denied fever, weakness, numbness, shortness of breath, and flulike symptoms. He had significant medical history of hypertension and was on a β-blocker in the past, but a year ago, he stopped taking medication due to an unspecified reason. The patient denied any history of tobacco smoking, alcoholism, and recreational drug use. The patient had a significant family history of hypertension in both his father and mother. Physical examination was unremarkable, and at the time of triage, his blood pressure (BP) was noted as 195/123 mm Hg, equal in both arms. The patient was promptly started on intravenous labetalol with the goal to reduce BP by 15% to 20% in the first hour. The BP was rechecked after an hour of starting labetalol and was 165/100 mm Hg. MRI of the brain was performed in the emergency department and demonstrated multiple scattered areas of increased signal intensity on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images in both the occipital and posterior parietal lobes. There were also similar lesions in both hemispheres of the cerebellum (especially the cerebellar white matter on the left) as well as in the medulla oblongata. The lesions were not associated with mass effect, and after contrast administration, there was no evidence of abnormal enhancement. In the emergency department, his BP decreased to 160/95 mm Hg, and he was transitioned from drip to oral medications and transferred to the telemetry floor. How would you manage this case?

The patient initially presented with headache, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, and confusion. The patient’s BP was found to be 195/123 mm Hg, and MRI of the brain demonstrated scattered lesions with increased intensity in the occipital and posterior parietal lobes, as well as in cerebellum and medulla oblongata. The clinical presentation, elevated BP, and brain MRI findings were suggestive of hypertensive emergency, more specifically hypertensive encephalopathy. These MRI changes can be seen particularly in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), a sequela of hypertensive encephalopathy. BP was initially controlled by labetalol, and after satisfactory control of BP, the patient was switched to oral antihypertensive medications.

Hypertensive emergency refers to the elevation of systolic BP >180 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >120 mm Hg that is associated with end-organ damage; however, in some conditions such as pregnancy, more modest BP elevation can constitute an emergency. An equal degree of hypertension but without end-organ damage constitutes a hypertensive urgency, the treatment of which requires gradual BP reduction over several hours. Patients with hypertensive emergency require rapid, tightly controlled reductions in BP that avoid overcorrection. Management typically occurs in an intensive care setting with continuous arterial BP monitoring and continuous infusion of antihypertensive agents.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Presentation

Clinical pearls, case study: treating hypertension in patients with diabetes.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Evan M. Benjamin; Case Study: Treating Hypertension in Patients With Diabetes. Clin Diabetes 1 July 2004; 22 (3): 137–138. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.22.3.137

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

L.N. is a 49-year-old white woman with a history of type 2 diabetes,obesity, hypertension, and migraine headaches. The patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 9 years ago when she presented with mild polyuria and polydipsia. L.N. is 5′4″ and has always been on the large side,with her weight fluctuating between 165 and 185 lb.

Initial treatment for her diabetes consisted of an oral sulfonylurea with the rapid addition of metformin. Her diabetes has been under fair control with a most recent hemoglobin A 1c of 7.4%.

Hypertension was diagnosed 5 years ago when blood pressure (BP) measured in the office was noted to be consistently elevated in the range of 160/90 mmHg on three occasions. L.N. was initially treated with lisinopril, starting at 10 mg daily and increasing to 20 mg daily, yet her BP control has fluctuated.

One year ago, microalbuminuria was detected on an annual urine screen, with 1,943 mg/dl of microalbumin identified on a spot urine sample. L.N. comes into the office today for her usual follow-up visit for diabetes. Physical examination reveals an obese woman with a BP of 154/86 mmHg and a pulse of 78 bpm.

What are the effects of controlling BP in people with diabetes?

What is the target BP for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Which antihypertensive agents are recommended for patients with diabetes?

Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Approximately two-thirds of people with diabetes die from complications of CVD. Nearly half of middle-aged people with diabetes have evidence of coronary artery disease (CAD), compared with only one-fourth of people without diabetes in similar populations.

Patients with diabetes are prone to a number of cardiovascular risk factors beyond hyperglycemia. These risk factors, including hypertension,dyslipidemia, and a sedentary lifestyle, are particularly prevalent among patients with diabetes. To reduce the mortality and morbidity from CVD among patients with diabetes, aggressive treatment of glycemic control as well as other cardiovascular risk factors must be initiated.

Studies that have compared antihypertensive treatment in patients with diabetes versus placebo have shown reduced cardiovascular events. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), which followed patients with diabetes for an average of 8.5 years, found that patients with tight BP control (< 150/< 85 mmHg) versus less tight control (< 180/< 105 mmHg) had lower rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and peripheral vascular events. In the UKPDS, each 10-mmHg decrease in mean systolic BP was associated with a 12% reduction in risk for any complication related to diabetes, a 15% reduction for death related to diabetes, and an 11% reduction for MI. Another trial followed patients for 2 years and compared calcium-channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,with or without hydrochlorothiazide against placebo and found a significant reduction in acute MI, congestive heart failure, and sudden cardiac death in the intervention group compared to placebo.

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial has shown that patients assigned to lower BP targets have improved outcomes. In the HOT trial,patients who achieved a diastolic BP of < 80 mmHg benefited the most in terms of reduction of cardiovascular events. Other epidemiological studies have shown that BPs > 120/70 mmHg are associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes. The American Diabetes Association has recommended a target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg. Studies have shown that there is no lower threshold value for BP and that the risk of morbidity and mortality will continue to decrease well into the normal range.

Many classes of drugs have been used in numerous trials to treat patients with hypertension. All classes of drugs have been shown to be superior to placebo in terms of reducing morbidity and mortality. Often, numerous agents(three or more) are needed to achieve specific target levels of BP. Use of almost any drug therapy to reduce hypertension in patients with diabetes has been shown to be effective in decreasing cardiovascular risk. Keeping in mind that numerous agents are often required to achieve the target level of BP control, recommending specific agents becomes a not-so-simple task. The literature continues to evolve, and individual patient conditions and preferences also must come into play.

While lowering BP by any means will help to reduce cardiovascular morbidity, there is evidence that may help guide the selection of an antihypertensive regimen. The UKPDS showed no significant differences in outcomes for treatment for hypertension using an ACE inhibitor or aβ-blocker. In addition, both ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to slow the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy. In the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE)trial, ACE inhibitors were found to have a favorable effect in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, whereas recent trials have shown a renal protective benefit from both ACE inhibitors and ARBs. ACE inhibitors andβ-blockers seem to be better than dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers to reduce MI and heart failure. However, trials using dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in combination with ACE inhibitors andβ-blockers do not appear to show any increased morbidity or mortality in CVD, as has been implicated in the past for dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers alone. Recently, the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) in high-risk hypertensive patients,including those with diabetes, demonstrated that chlorthalidone, a thiazide-type diuretic, was superior to an ACE inhibitor, lisinopril, in preventing one or more forms of CVD.

L.N. is a typical patient with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Her BP control can be improved. To achieve the target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg, it may be necessary to maximize the dose of the ACE inhibitor and to add a second and perhaps even a third agent.

Diuretics have been shown to have synergistic effects with ACE inhibitors,and one could be added. Because L.N. has migraine headaches as well as diabetic nephropathy, it may be necessary to individualize her treatment. Adding a β-blocker to the ACE inhibitor will certainly help lower her BP and is associated with good evidence to reduce cardiovascular morbidity. Theβ-blocker may also help to reduce the burden caused by her migraine headaches. Because of the presence of microalbuminuria, the combination of ARBs and ACE inhibitors could also be considered to help reduce BP as well as retard the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Overall, more aggressive treatment to control L.N.'s hypertension will be necessary. Information obtained from recent trials and emerging new pharmacological agents now make it easier to achieve BP control targets.

Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular complications of diabetes.

Clinical trials demonstrate that drug therapy versus placebo will reduce cardiovascular events when treating patients with hypertension and diabetes.

A target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg is recommended.

Pharmacological therapy needs to be individualized to fit patients'needs.

ACE inhibitors, ARBs, diuretics, and β-blockers have all been documented to be effective pharmacological treatment.

Combinations of drugs are often necessary to achieve target levels of BP control.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are agents best suited to retard progression of nephropathy.

Evan M. Benjamin, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and Vice President of Healthcare Quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Email alerts

- Online ISSN 1945-4953

- Print ISSN 0891-8929

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Making Best Practice, Every Day Practice

Case study: The hypertensive patient

Working with patients who are not willing to engage fully with healthcare services is a common occurrence. The process requires patience and a focus on providing the patient with full information about their condition and then allowing them to make decisions about their treatment. Here, Dr Terry McCormack (GP and Cardiovascular Lead, North Yorks) describes the approach of his practice to a man with hypertension.

A 57-year old man Mr ‘Hawk’ Ward attends a routine NHS Health Check with a health care assistant (HCA) in the local surgery. He had had no contact with healthcare for many years and was not keen on any interventions. Repeated blood pressure (BP) measurements showed very high BP of 205/91 mmHg. The assessment also showed:

- A strong family history of CV disease (brother

- Smoker 30/day

- Appearance healthy

- Alcohol intake 100 units/week

The HCA immediately referred him to the GP who had a long discussion with him and was able to persuade him to take a blood test and have home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) although he declined ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

He returned to see the practice senior nurse after HBPM and further investigations showed:

- HBPM average of 8 readings (first 2 discounted) 180/95 mmHg

- Total cholesterol 7.2 mmol/L, HDL 1.4 mmol/L, non-HDL 5.8 mmol/L

- QRISK2 36.1

- Liver Function Tests normal

Mr Ward agreed with the senior nurse to stop smoking, excess alcohol intake, adding salt to food, but would not take medication. He reluctantly agreed to make an appointment to see Dr McCormack.

At the GP appointment

- Mr Ward announces that ‘medication is not an option’

- The GP explains all his risks (including the relevance of non-HDL cholesterol and QRISK2 assessment) and then ask him what he would like to do about it.

- Shared, informed decision making explained

- The GP offers ABPM to confirm the diagnosis

After some time spent considering the GPs evidence and advice, the patient decided to accept some medication and was put on amlodipine 5mg.

Current situation

At a later visit Mr Ward’s blood pressure had reduced to 147/84 mmHg. He has cut down on alcohol and was less agitated. He agreed to take atorvastatin 20 mg and is continuing on therapy and has improved his engagement with the practice team. This patient and ongoing approach has produced significant improvements in his condition, lowered his risk of subsequent events and provides promise for ongoing interaction with health care services.

Case study: Nurse COPD assessment

Case study: Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy

Case study: Statin intolerance in a patient with high cardiovascular risk

Join our community of primary care professionals today, educational partners.

- Open access

- Published: 15 September 2020

Treatment adherence among patients with hypertension: findings from a cross-sectional study

- Fahad M. Algabbani 1 &

- Aljoharah M. Algabbani 2

Clinical Hypertension volume 26 , Article number: 18 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

33 Citations

Metrics details

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of mortality globally. Patient’s adherence to treatment is a cornerstone factor in controlling hypertension and its complications. This study assesses hypertension patients’ adherence to treatment and its associated factors.

This cross-sectional study conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study targeted outpatients aged ≥18 years who were diagnosed with hypertension. Participants were recruited using a systemic sampling technique. The two main measurements were assessing adherence rate of antihypertensive medications using Morisky scale and identifying predictors of poor medication adherence among hypertensive patients including socio-economic and demographic data, health status, clinic visits, medication side effects, medications availability, and knowledge. Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were performed to assess factors associated with poor adherence.

A total of 306 hypertensive outpatients participated in this study. 42.2% of participants were adherent to antihypertensive medications. Almost half of participants (49%) who reported having no comorbidities were adherent to antihypertensive medications compared to participants with one or more than one comorbidities 41, 39% respectively. The presence of comorbid conditions and being on multiple medications were significantly associated with medication adherence ( P -values, respectively, < 0.004, < 0.009). Patients with good knowledge about the disease and its complications were seven times more likely to have good adherence to medication ( P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Non-adherence to medications is prevalent among a proportion of hypertensive patients which urges continuous monitoring to medication adherence with special attention to at risks groups of patients. Patients with comorbidities and on multiple medications were at high risk of medication non-adherence. Patients’ knowledge on the disease was one of the main associated factors with non-adherence.

Hypertension is one of the most common chronic diseases in Saudi Arabia and a rising health burden, affecting 26.1% adult population [ 1 ]. Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart failure, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and renal failure [ 2 ]. Controlling hypertension reduces the risk of cerebrovascular accident (CVA), coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, and mortality [ 2 , 3 ]. There are several factors that affect blood pressure control. Patients’ adherence to treatment is one of the major factors in controlling blood pressure and preventing hypertension complications [ 3 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adherence to long-term therapy as “the extent to which a person’s behavior-taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes-corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider” [ 3 ]. Patients with a high level of medication adherence were found to have better blood pressure control [ 4 ]. Still, adherence to hypertension treatment is challenging, due to the asymptomatic nature of the disease [ 5 ].

Several studies investigated the adherence rate among hypertension patients and sociodemographic factors affecting medication adherence including age, gender, comorbidities, patients’ knowledge about the disease, the number of medications. A study conducted in Saudi Arabia showed that only 34.7% of male hypertensive patients were found to be adherent to their medication [ 6 ]. The study reported a negative association between the presence of comorbidities and the adherence level [ 6 ]. A cross-sectional study on medication adherence among patients with hypertension in Malaysia, found an association between adherence and good knowledge of the medications and disease [ 7 ]. The study also found that the increase in the number of drugs patients taking has a negative effect on medication adherence [ 7 ]. Other studies had similar findings regarding the association between the number of medications and adherence [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Iran, older patients reported high adherence to antihypertensive medication and better knowledge of their disease than younger patients [ 9 ]. However, number of studies reported no significant associations between age and medication adherence [ 8 , 11 ]. Female patients were more likely to adhere to their medication, compared to males [ 12 ]. Another study on the prevalence and predictors of poor antihypertensive reported that male patients were more adherent than female patients [ 13 ]. Some studies reported no relationship between gender and adherence [ 9 , 11 ].

Educational level and health literacy were shown to be associated with medication adherence. A cross-sectional study conducted in Iraq showed that adherence decreased in patients with primary and secondary school education, while no significant difference among patients with higher education and undereducated patients [ 14 ]. Similar results found in a systematic review conducted in hypertension management and medication adherence [ 15 ]. On the other hand, no association between educational level and adherence was found in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia [ 8 ]. However, good health knowledge of hypertension shown to be associated with good adherence to medication treatment in several studies [ 7 , 11 ]. Two cross-sectional studies conducted in Turkey and Algeria showed a significant association between knowledge of complications related to hypertension and good adherence to antihypertensive therapy [ 16 , 17 ].

Hypertension is one of the major health issues in Saudi Arabia; affecting more than a quarter of the Saudi adult population [ 1 ]. Only 37% of hypertensive patients on medication have their blood pressure controlled [ 18 ]. Non-adherence to antihypertensive medications is a potential contributing factor to uncontrolled hypertension. With limited studies conducted to investigate this challenging issue, this cross-sectional study aims to assess the adherence rate among hypertensive patients and associated factors affecting adherence to antihypertensive medications.

Study design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the adherence rate of antihypertensive medications and the predictors of poor medication adherence among hypertensive patients at primary health clinics (PHCs) in Prince Sultan Medical City (PSMMC) in Riyadh the capital city of Saudi Arabia. Single population proportion formula was used to calculate the sample size based on the prevalence of hypertension in Saudi Arabia (26.1%) [ 1 ]. With a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, a total of 306 randomly selected outpatients with hypertension following up at primary health clinics were included in this study.

Participants recruitment

Participants in this study were recruited using a systemic sampling technique. Every fourth consecutive patient who fits the criteria was included. Arabic speaker patients older than 18 years who have been diagnosed with hypertension for more than three months were included in this study. Patients who do not speak Arabic had mental retardation, secondary hypertension, or who were younger than 18 years old were excluded from the study. The data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire that was distributed in the waiting area of the pharmacy. Illiterate participants were interviewed by a trained data collector. Before participants’ recruitment in the study, informed consent was obtained from all patients after a full explanation of the study. The study was approved and supervised by the institution review board (IRB) of Prince Sultan Medical City.

Measurements

The questionnaire consists of four main sections. The first section assesses participants’ socio-economic factors including age, gender, marital status, occupation, the highest level of education currently attained, occupation, and monthly income. The second section assesses the factors affecting medication adherence including comorbidities, number of medications, number of daily doses, number of clinic visits, the distance to the clinic, medication side effects, medication availability at the pharmacy. The third section aimed to assess patients’ adherence to treatment. The fourth part assesses the patients’ knowledge about hypertension.

Medication adherence was assessed using the 8- items Morisky scale [ 19 ]. Morisky scale has been validated and found to be reliable (α = .83) [ 20 ]. The scale is based on the patients’ self-response and consists of eight questions, seven items with yes or no response, and one item with a 5-point Likert scale response option. The total score ranges from 1 to 8, the patient whose adherence score was six or more is considered adherent. For linguistic validation, questions were translated forward and backward into Arabic by an independent translator.

The participant’s knowledge about hypertension was assessed using nine structured questions. The questions focused on different aspects of hypertension, namely blood pressure target, lifestyle modification effect, complications, treatment, and cure. During analysis, patients who answered < 70% were considered to have low knowledge and patient how answered ≥70% of the questions were considered to have good knowledge. The 70 % cut-off is based on the minimally acceptable level of quality control at PSMMC [ 21 ].

The questionnaire was pre-tested and then a pilot survey was conducted on 20 patients for clarity and feasibility. The questionnaire was also evaluated and reviewed by two independent family medicine consultants at Prince Sultan Medical City for validation.

Data analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to assess participants’ characteristics. Chi-square analysis was used to determine the association between demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors with medication adherence. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with poor adherence. The variables were analyzed collectively using logistic regression to study the potential factors to avoid confounding bias. The association was considered statistically significant if the P -value was less than 0.05. Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25 and Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 was used for data analysis.

A total of 306 outpatients who have hypertension participated in this study. Approximately 43% of the participants’ ages range was between 56 and 65. The majority of participants were married (92%), employed (61%), and had a high school diploma or above (80%). Most of the participants were middle income in the 5000–10,000 Saudi Riyal range of monthly income. Nearly one-third (28.1%) of the respondents in this study had no comorbidities while two-thirds reported having one or more comorbidities. The demographic, and socioeconomic clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1 .

Only 13% of the respondents live at a distance of less than half an hour from the clinic. Of the total participants, 14.1% reported visiting the primary health clinic once in the last year, 29.4% twice, 24.2% three times. The majority of participants reported taking less than four medications a day and 31.4% reported taking four or more medications a day. As to antihypertensive medication side effects, 19.6% reported having medication side effects. Only 4.9% of the participants reported that they stop taking their antihypertensive medications when they get sick. Approximately 9% of the participants reported that they stop taking their medications when it is not available at the pharmacy. Findings show that half (50.7%) of the participants were knowledgeable about the disease. The clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1 .

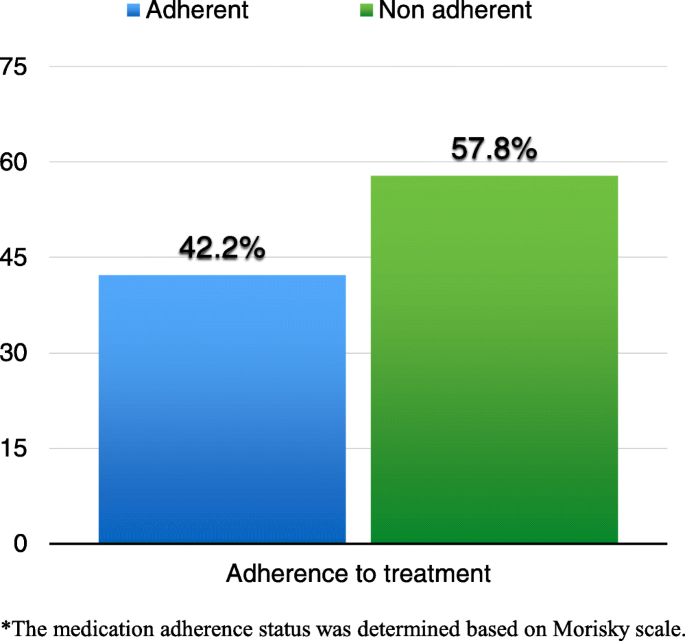

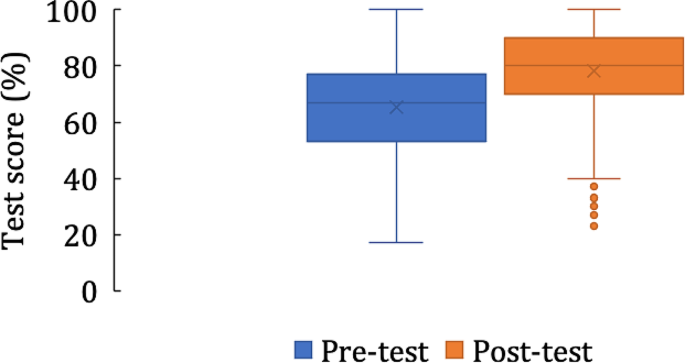

Figure 1 presents the percentage of participants’ adherence to antihypertensive treatment. Based on Morisky scale test results, 42.2% of the participants in this study were adherent to antihypertensive medications, while 57.8% were not adherent.

Distribution of patients according to their medication adherence status*

Table 2 presents the adherence rate in relation to the participants’ demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. The presence of comorbid conditions is significantly associated with medication adherence ( P < 0.001). Almost half of participants (49%) who reported having no comorbidities were adherent to antihypertensive medications compared to the participants with one or more than one comorbidities 41, 39% respectively. As for the number of medications, the adherence rate was found to be better among patients who were taking less than four medications (47.1%) compared to patients who were taking four or more medications (31.3%). Patients who visited the clinic once in the last year were more adherent than those who visited the clinic more than once ( p < 0.05). No significant association between age, gender, income, educational level, and distance from home to the clinic.

The participants were asked eight questions about hypertension. Table 3 shows the distribution of the correct and incorrect answers giving by the participants. Most participants (64.4%) knew the target blood pressure for hypertensive patients and 40.8% think that hypertension can be cured. The majority (78%) knew that a low salt diet helps in lowering high blood pressure. Only 61% knew that hypertension can affect eyes and 13.4% reported that they stop taking their medication when they feel their blood pressure under control.

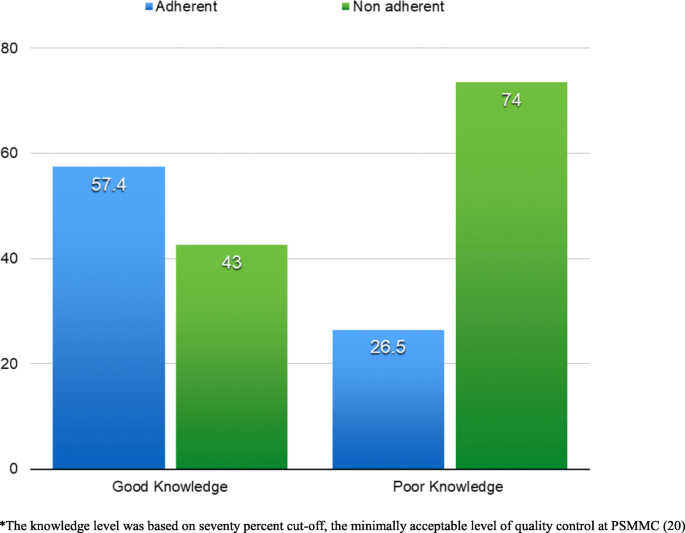

Adherence to antihypertensive medications among patients with good and poor knowledge levels about hypertension was assessed based on nine structured questions. Figure 2 shows the adherence to hypertension treatment among patients with good and poor knowledge level. 57.4% of patients with good knowledge levels were adherent compared to 42.6% who were not adherent. The majority (73.5%) of patients with poor knowledge levels were not adherent to treatment.

Adherence to hypertension treatment among patients with good and poor knowledge level*

Table 4 presents the factors associated with good adherence. When conducting binary logistic regression, knowledge about the disease was found to be significantly associated with adherence. Patients with good knowledge about the disease were seven times more likely to have good adherence to antihypertensive medications than those with poor knowledge (AOR 7.4 [95% CI: 4.177–13.121], p < 0.001).

Several studies have investigated factors affecting medication adherence. This study shows that the level of adherence to antihypertensive medications is low. In this sample the adherence rate to hypertension treatment was found to be only 42%, which is similar to the study conducted in Al-Khobar and higher than the study conducted in Taif where adherence rate was found to be 47 and 34.7%, respectively [ 6 , 8 ]. Other studies conducted in different countries reported adherence rates ranging from 15 to 88% [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. This discrepancy in adherence rate is potentially due to the differences in population characteristics, medication adherence assessment tools, and healthcare systems.

The association between sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors and adherence level has been investigated in several studies. In a study done in Hong Kong, older patients were found to be more adherent. However, in this study, there was no association between age and adherence. In another study done in the United States, female patients were less adherent to hypertension medication compared to male patients [ 13 ]. A study conducted in Malaysia reported that female patients were more adherent than male patients [ 22 ]. Our study showed that there was no significant relationship between gender and adherence. A meta-analysis suggested that the association between age, gender, and adherence level is weak [ 26 ]. The results of our study also demonstrate no significant relationship between marital status and educational level with adherence, which is similar to findings reported by other studies [ 9 , 27 ].

Previous research found that shorter traveling time from residence to the healthcare facility could increase patients’ adherence [ 28 ]. A study in Ethiopia found that the adherence level was lower in patients who lived more than 10 km from healthcare facilities [ 29 ]. A cross-sectional observational study done in Northwest Ethiopia indicated that patients who live less than 10 km from the healthcare facility had an adherence rate of 74% compared to 58% for patients who live far from the healthcare facility [ 29 ]. As the authors attributed this problem to poor infrastructure and lack of transportation in Ethiopia, the study suggested that shorter traveling time from residence to the healthcare facility could increase patients’ adherence [ 29 ]. In this study, distance from home to the clinic was not associated with hypertensive treatment. These differences may be due to the higher level of car ownership in Saudis Arabia which makes it easier to access health care facilities [ 30 ].

Only 8.8% of the participants reported not taking their medication when it is not available at the hospital pharmacy. This low percentage may be explained by the multiple community health centers in Saudi Arabia which provide free health care including medications dispensing. Moreover, the medication cost at private pharmacies in Saudi Arabia is affordable for most patients. According to the published Saudi Hypertension Management Guidelines the prices of the antihypertensive medications ranges between 7 to 118 Saudi Riyal (about 2 to 31 US Dollar) [ 31 ].

Many patients with hypertension will need two or more antihypertensive medications to achieve goal blood pressure [ 2 ]. In this sample significant association was observed between the number of medications and adherence level. The adherence rate among patients taking less than four medications was 47.1% compared to 31.3% to those who take four or more medications. Similarly, other studies reported the negative association between the number of medication and adherence levels [ 29 , 32 ].

Findings indicate that patients with multiple comorbidities were less adherent to antihypertensive medication, which is inconsistent with a previous study done in Taif which showed a negative association between the presence of comorbidity and adherence level [ 6 ]. This may be related to the fact that most patients with multiple comorbidities require taking multiple complex medications.

The result of our study showed that the patient who visited the clinic once in the last year were more adherent than the patient who visited the clinic more than once. This could be explained by that most patients with multiple comorbidities and on multiple medications frequently visit the clinic for issues related to their disease and to refill prescriptions.

Our study demonstrated the positive association between knowledge and adherence levels. Patients who had good knowledge were more adherent to the treatment [ 29 ]. Previous studies showed that patients who know the ideal target blood pressure level were more adherent to their medications [ 16 , 20 ]. In this study, only 64.4% of the participants knew the ideal target of blood pressure and 40.8% of the patients believe that hypertension can be cured. A study conducted in Rajshahi, Bangladesh found that 65.8% of the patients believe that hypertension is curable. Patients how have been educated by their physicians and healthcare providers were more adherents to treatment as they have a better understanding of the disease nature, the ideal target of blood pressure, and the complications of hypertension [ 33 ]. Therefore, patient education in disease nature and management is considered a key factor in the treatment of hypertension.

The study findings were based on self-reported survey. Self-reported data is a common method used in a cross-sectional study. However, self-reported data is subjected to biases such as response and recall biases that can lead to under- or overestimation of findings. On the other hand, adherence in this study was measured based on a validated self-report adherence scale and knowledge was tested based on evaluated and reviewed assessment items by two independent family medicine consultants. Moreover, this study conducted in one of the largest medical cities that serves a large community in the capital city Riyadh. Due to the study design and sampling method, study findings cannot be generalized and temporal relationships cannot be established between risk factors and adherence. Nevertheless, this study provides a snapshot of adherence to antihypertensive medication status and associated determinates among outpatients. Future large scale longitudinal studies will contribute to a better understanding of adherence status and associated factors among hypertensive patients.

Non-adherence to medications is prevalent in proportion of patients with hypertension. Therefore, there is an urge to continually monitor patients’ adherence to antihypertensive medication using a standardized scale. Patients with comorbidities and on multiple medications were at higher risk of non-adherence. There is a need to encourage patients on multiple medications to use adherence aids such as weekly pill organizers and medication alarm devices. Hypertensive patients’ knowledge of the disease and its complications was one of the main factors affecting patients’ adherence to treatment. Implementation of health awareness interventions and education programs intended for hypertensive patients will help improve medication adherence.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted odd ratio

Confidence interval

Blood pressure

Prince Sultan Medical City

primary health clinic

institution review board

Cerebrovascular accident

The World Health Organization

Al-Nozha MM, Abdullah M, Arafah MR, Khalil MZ, Khan NB, Al-Mazrou YY, et al. Hypertension in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(1):77–84.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure the seventh report of the joint National Committee on complete report. Natl High Blood Press Educ Progr. 2003;42(6):1206.

CAS Google Scholar

De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:323.

Bramley TJ, Gerbino PP, Nightengale BS, Frech-Tamas F. Relationship of blood pressure control to adherence with antihypertensive monotherapy in 13 managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(3):239–45.

Saeed AA, Al-Hamdan NA, Bahnassy AA, Abdalla AM, MAF A, Abuzaid LZ. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among Saudi adult population: A national survey. Int J Hypertens. 2011, 2011:174135 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21912737 . [cited 2020 May 4].

Elbur AI. Level of adherence to lifestyle changes and medications among male hypertensive patients in two hospitals in taif; kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(4):168–72.

Google Scholar

Ramli A, Ahmad NS, Paraidathathu T. Medication adherence among hypertensive patients of primary health clinics in Malaysia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:613–22.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Al-Sowielem LS, Elzubier AG. Compliance and knowledge of hypertensive patients attending PHC centres in Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Heal J. 1998;4(2):301–7 Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/118129 . [cited 2020 May 4].

Hadi N, Rostami-Gooran N. Determinant factors of medication compliance in hypertensive patients of Shiraz, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2004;7(4):292–6 Available from: https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx? ID=13626. [cited 2020 May 4].

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2012 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2012;3:125(1).

Goussous LS, Halasah NA, Halasa M. Non - Compliance to Antihypertensive Treatment among Patients Attending Prince Zaid Military Hospital. World Fam Med Journal/Middle East J Fam Med. 2015;13(1):15–9 Available from: https://platform.almanhal.com/Files/2/58839 . [cited 2020 May 4].

Article Google Scholar

Schoberberger R, Janda M, Pescosta W, Sonneck G. The COMpliance praxiS survey (COMPASS): a multidimensional instrument to monitor compliance for patients on antihypertensive medication. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(11):779–87.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hyre AD, Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Kawasaki L, KB DS. Prevalence and Predictors of Poor Antihypertensive Medication Adherence in an Urban Health Clinic Setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2007;9(3):179–86 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06372.x . [cited 2020 May 4].

Issa H, Banna A, Mohmed LH. Compliance and knowledge of hypertensive patients attending Shorsh Hospital in Kirkuk Governorate. Iraqi Postgrad Med J. 2010;9(2):145–50.

Klootwyk JM, Sanoski CA. Adherence and persistence in hypertension management. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2011;18(8):351–8.

Karaeren H, Yokuşoǧlu M, Uzun Ş, Baysan O, Köz C, Kara B, et al. The effect of the content of the knowledge on adherence to medication in hypertensive patients. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2009;9(3):183–8.

Ghembaza MA, Senoussaoui Y, Tani M, Meguenni K. Impact of patient knowledge of hypertension complications on adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2014;10(1):41–8.

Elzubier AG, Al-Shahri MA. Drug control of hypertension in primary health care centers-registered patients, Al-khobar, saudi arabia. J Family Community Med. 1997;4(2):47–53 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23008573 . [cited 2020 May 4].

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10(5):348–54.

González-fernández RA, Rivera M, Torres D, Quiles J, Jackson A. Usefulness of a systemic hypertension in-hospital educational program. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(20):1384–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brown J, Mellott S. The healthcare quality handbook : a professional resource and study guide; 2016. p. 439.

Mafutha GN, Wright SCD. Compliance or non-compliance of hypertensive adults to hypertension management at three primary healthcare day clinics in Tshwane. Curationis. 2013;36(1):E1–6.

Hussanin S, Boonshuyar C, Ekram A. Non-adherence to antihypertensive treatment in essential hypertensive patients in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Anwer Khan Mod Med Coll J. 2011;2(1):9–14.

Al-Mehza AM, Al-Muhailije FA, Khalfan MM, Al-Yahya AA. Drug compliance among hypertensive patients; an area based study. Eur J Gen Med. 2009;6(1):6–10 Available from: http://www.ejgm.co.uk/download/drug-compliance-among-hypertensive-patients-an-area-based-study-6685.pdf . [cited 2020 May 4].

Busari OA, Olanrewaju TO, Desalu OO, Opadijo OG, Jimoh AK, Agboola SM, et al. Impact of Patients’ Knowledge, Attitude and Practices on Hypertension on Compliance with Antihypertensive Drugs in a Resource-poor Setting. TAF Prev Med Bull. 2010;9(2):87–92 Available from: www.korhek.org . [cited 2020 May 4].

Fitz-Simon N, Bennett K, Feely J. A review of studies of adherence with antihypertensive drugs using prescription databases. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(2):93–106.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lee GKY, Wang HHX, Liu KQL, Cheung Y, Morisky DE, Wong MCS. Determinants of medication adherence to antihypertensive medications among a Chinese population using Morisky medication adherence scale. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62775.

Gonzalez J, Williams JW, Noël PH, Lee S. Adherence to mental health treatment in a primary care clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(2):87–96.

Ambaw AD, Alemie GA, Wyohannes SM, Mengesha ZB. Adherence to antihypertensive treatment and associated factors among patients on follow up at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):282.

Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access [internet]. J Commun Health. 2013;38:976–93 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23543372 . [cited 2020 May 4].

Saudi Hypertension Management Society. Saudi Hypertension Guidelines. 2018.

Marcum ZA, Gellad WF. Medication Adherence to Multidrug Regimens. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):287–300 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22500544 . [cited 2020 May 5].

Neutel JM, Smith DHG. Improving Patient Compliance: A Major Goal in the Management of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2003;5(2):127–32 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.00495.x . [cited 2020 May 5].

Download references

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Family Medicine Department, Prince Sultan Military Medical City (PSMMC), Riyadh, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Fahad M. Algabbani

George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA

Aljoharah M. Algabbani

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The study design was conceptualized by FA and AA. Data collection was managed by FA and data analysis and interpretation were conducted by FA and AA. All authors participated in writing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fahad M. Algabbani .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from institution review board (IRB) of Prince Sultan Medical City. Before participants’ recruitment in the study, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Algabbani, F.M., Algabbani, A.M. Treatment adherence among patients with hypertension: findings from a cross-sectional study. Clin Hypertens 26 , 18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-020-00151-1

Download citation

Received : 21 May 2020

Accepted : 03 August 2020

Published : 15 September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-020-00151-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- High blood pressure

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Nonadherence

Clinical Hypertension

ISSN: 2056-5909

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Case Studies: BP Evaluation and Treatment in Patients with Prediabetes or Diabetes

—the new acc/aha blood pressure guidelines call for a more aggressive diagnostic and treatment approach in most situations..

By Kevin O. Hwang, MD, MPH, Associate Professor, McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX

The following case studies illustrate how the new ACC/AHA guideline specifies a shift in the definition of BP categories and treatment targets.

A 59-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presents with concerns about high blood pressure (BP). At a recent visit to his dentist he was told his BP was high. He was reclining in the dentist’s chair when his BP was taken, but he doesn’t remember the exact reading. He has no symptoms. He has never taken medications for high BP. He takes metformin for type 2 diabetes.

His BP is measured once at 146/95 mm Hg in the left arm while sitting. Physical exam is unremarkable except for obesity. EKG is unremarkable.

BP Measurement

Controlling BP in patients with diabetes reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, but the available data are not sufficient to classify this patient with respect to BP status. The reading taken while reclining in the dentist’s chair was likely inaccurate. A single reading in the medical clinic, even with correct technique, is not adequate for clinical decision-making because individual BP measurements vary in unpredictable or random ways.

The accuracy of BP measurement is affected by patient preparation and positioning, technique, and timing. Before the first reading, the patient should avoid smoking, caffeine, and exercise for at least 30 minutes and should sit quietly in a chair for at least 5 minutes with back supported and feet flat on the floor. An appropriately sized cuff should be placed on the bare upper arm and with the arm supported at heart level. For the first encounter, BP should be recorded in both arms. The arm with the higher reading should be used for subsequent measurements.

It is recommended that one use an average of 2 to 3 readings, separated by 1 to 2 minutes, obtained on 2 to 3 separate visits. Some of those readings should be performed outside of the clinical setting, either with home BP self-monitoring or 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring, especially when confirming the diagnosis of sustained hypertension. Note that a clinic BP of 140/90 corresponds to home BP values of 135/85. Multiple BP readings in the clinic and at home allow for classification into one of the following categories.

The BP is measured in the office with the correct technique and timing referenced above. The patient is educated on how on to measure BP at home with a validated monitor. He should take at least 2 readings 1 minute apart in the morning and in the evening before supper (4 readings per day). The optimal schedule is to measure BP every day for a week before the next clinic visit, which is set for a month from now. Obtaining multiple clinic and home BP readings on multiple days will support a well-informed assessment of the patient’s BP status and subsequent treatment decisions.

A 62 year old African-American woman with prediabetes presents for her annual physical. She has no complaints. The average of 2 BP readings in her right arm is BP 143/88. Her physical exam is unremarkable except for obesity. She has no history of myocardial infarction, stroke, kidney disease, or heart failure. After the visit, she measures her BP at home and returns 1 month later. The average BP from multiple clinic and home readings is 138/86.

Her total cholesterol is 260 mg/dL, HDL 42 mg/dL, and LDL 165 mg/dL. She does not smoke.

Stage 1 Hypertension

Under the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline, she has stage 1 hypertension (HTN). This guideline uses a uniform BP definition for HTN without regard to patient age or comorbid illnesses, such as diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

In patients with stage 1 HTN and no known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) , the new guideline recommends treating with BP-lowering medications if the 10-year risk for ASCVD risk is 10% or greater. With input such as her age, gender, race, lipid profile, and other risk factors, the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations tool estimates her 10-year risk to be approximately 10.5%.

With stage 1 HTN and 10-year ASCVD risk of 10% or higher, she would benefit from a BP-lowering medication. Thiazide diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers are first-line agents for HTN because they reduce the risk of clinical events. In African-Americans, thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers are more effective for lowering BP and preventing cardiovascular events compared to ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Patient-specific factors, such as age, comorbidities, concurrent medications, drug adherence, and out-of-pocket costs should be considered. Shared decision making should drive the ultimate choice of antihypertensive medication(s).

Nonpharmacologic strategies for prediabetes and HTN include dietary changes, physical activity, and weight loss. If clinically appropriate, she should also avoid agents which could elevate BP, such as NSAIDs, oral steroids, stimulants, and decongestants.

A goal BP of 130/80 is recommended. After starting the new BP medication, she should monitor BP at home and return to the clinic in 1 month. If the BP goal is not met at that time despite adherence to treatment, consideration should be given to intensifying treatment by increasing the dose of the first medication or adding a second agent.

A 63 year old man with type 2 diabetes has an average BP of 151/92 over the span of several weeks of measuring at home and in the clinic. He also has albuminuria.

Stage 2 Hypertension:

The BP treatment goal patients with diabetes and HTN is less than 130/80. While some patients can be effectively treated with a single agent, serious consideration should be given to starting with 2 drugs of different classes, especially if BP is more than 20/10 mm Hg above their BP target. Giving both medications as a fixed-dose combination may improve adherence.

In this man with diabetes and HTN, any of the first-line classes of antihypertensive agents (diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and CCBs) would be reasonable choices. Given the presence of albuminuria, an ACE inhibitor or ARB would be beneficial for slowing progression of kidney disease. However, an ACE inhibitor and ARB should not be used simultaneously due to an increase in cardiovascular and renal risk observed in clinical trials.

He is started on a fixed-dose combination of an ACE-inhibitor and thiazide diuretic. He purchases a validated BP monitor which can transmit BP readings to his provider’s electronic health records system. Direct transmission of BP data to the provider has been shown to help patients achieve greater reductions in BP compared to self-monitoring without transmission of data. One month follow-up is recommended to determine if the treatment goal has been met.

Published: April 30, 2018

- 2. Final Recommendation Statement: High Blood Pressure in Adults: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. September 2017.

Does cabg owe its success more to sag--or to mag, dvt treatment: home versus hospital, perioperative thromboembolic complications predict long-term vte risk, coronary plaque in people with well-controlled hiv and low ascvd risk, poor neighborhood, poor mi outcome, stroke risk at age 66 to 74 years—with atrial fibrillation but without other risk factors, using cardiovascular biomarkers to diagnose type 2 mi: yea or nay, cardiac rehabilitation: outcomes in south asian patients.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 April 2024

Efficacy and safety of a four-drug, quarter-dose treatment for hypertension: the QUARTET USA randomized trial

- Mark D. Huffman 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Abigail S. Baldridge 3 , 4 ,

- Danielle Lazar 5 ,

- Hiba Abbas 5 ,

- Jairo Mejia 5 ,

- Fallon M. Flowers 5 ,

- Adriana Quintana 5 ,

- Alema Jackson 5 ,

- Namratha R. Kandula 3 , 6 ,

- Donald M. Lloyd-Jones 3 , 7 ,

- Stephen D. Persell 6 , 8 ,

- Sadiya S. Khan 3 , 7 ,

- James J. Paparello 3 , 9 ,

- Aashima Chopra 3 ,

- Priya Tripathi 3 ,

- My H. Vu 3 ,

- Clara K. Chow 10 &

- Jody D. Ciolino 3 , 11

Hypertension Research ( 2024 ) Cite this article

404 Accesses

1 Altmetric

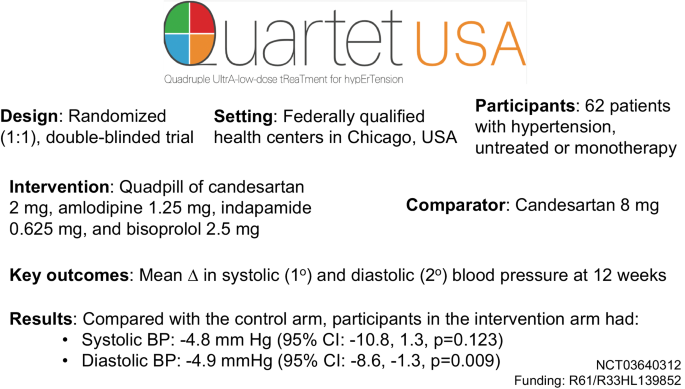

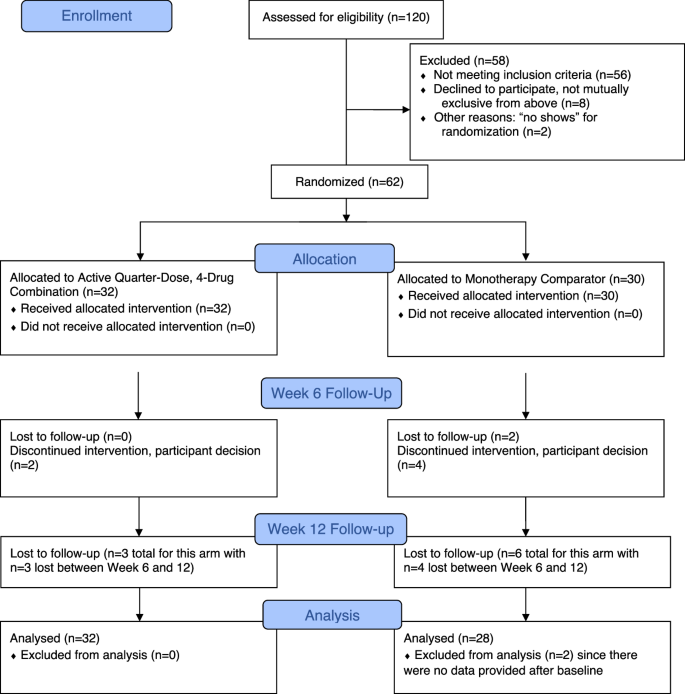

Metrics details

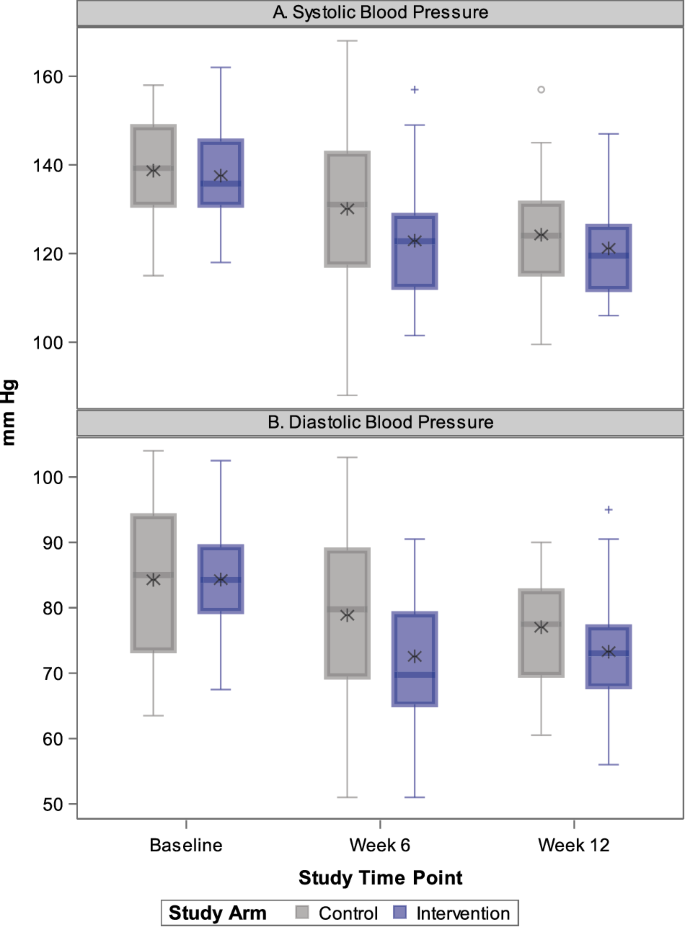

New approaches are needed to lower blood pressure (BP) given persistently low control rates. QUARTET USA sought to evaluate the effect of four-drug, quarter-dose BP lowering combination in patients with hypertension. QUARTET USA was a randomized (1:1), double-blinded trial conducted in federally qualified health centers among adults with hypertension. Participants received either a quadpill of candesartan 2 mg, amlodipine 1.25 mg, indapamide 0.625 mg, and bisoprolol 2.5 mg or candesartan 8 mg for 12 weeks. If BP was >130/>80 mm Hg at 6 weeks in either arm, then participants received open label add-on amlodipine 5 mg. The primary outcome was mean change in systolic blood pressure (SBP) at 12 weeks, controlling for baseline BP. Secondary outcomes included mean change in diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and safety included serious adverse events, relevant adverse drug effects, and electrolyte abnormalities. Among 62 participants randomized between August 2019-May 2022 ( n = 32 intervention, n = 30 control), mean (SD) age was 52 (11.5) years, 45% were female, 73% identified as Hispanic, and 18% identified as Black. Baseline mean (SD) SBP was 138.1 (11.2) mmHg, and baseline mean (SD) DBP was 84.3 (10.5) mmHg. In a modified intention-to-treat analysis, there was no significant difference in SBP (−4.8 mm Hg [95% CI: −10.8, 1.3, p = 0.123] and a −4.9 mmHg (95% CI: −8.6, −1.3, p = 0.009) greater mean DBP change in the intervention arm compared with the control arm at 12 weeks. Adverse events did not differ significantly between arms. The quadpill had a similar SBP and greater DBP lowering effect compared with candesartan 8 mg. Trial registration number: NCT03640312.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reduced efficacy of blood pressure lowering drugs in the presence of diabetes mellitus—results from the TRIUMPH randomised controlled trial

Sonali R. Gnanenthiran, Ruth Webster, … on behalf of the TRIUMPH Study Group

Efficacy and safety of esaxerenone (CS-3150) in primary hypertension: a meta-analysis

Ran Sun, Yali Li, … Xiaoxia Guo

Association of intensive blood pressure management with cardiovascular outcomes in patients using multiple classes of antihypertensive medications: a post-hoc analysis of the STEP Trial

Kaipeng Zhang, Qirui Song, … Jun Cai

Introduction

More than 1 billion adults have hypertension globally [ 1 ]. Despite widespread availability of generic blood pressure lowering drugs for decades, hypertension control rates (defined as a blood pressure <140/<90 mm Hg) remain persistently low (<50%) among adults in the United States [ 2 ]. Control rates are even lower (<25%) when accounting for newer, lower blood pressure targets (defined as a blood pressure <130/<80 mm Hg) recommended by national and international clinical practice guidelines [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Hypertension is more prevalent in racially and ethnically minoritized individuals, in whom control rates are also lower than other groups [ 6 ]. Most patients with hypertension are initially treated with a single blood pressure lowering drug that is titrated up over multiple, monthly office visits with additional medications added sequentially. Therapeutic inertia contributes to persistently low hypertension control rates and has not improved [ 7 , 8 ]. Thus, a new approach is needed. New strategies are especially important among low-income individuals who seek care within federally qualified health centers, where the burden of hypertension is high and control rates are lower than the general population [ 9 ].

Previous trials of single drug ultra-low dose (i.e., one-quarter of a standard dose) blood pressure lowering therapy demonstrated an average of −4.7 systolic and −2.4 diastolic mm Hg greater blood pressure lowering compared with placebo with no significant difference in adverse events [ 10 , 11 ]. Each additional drug added in a combination (e.g., two-, three-, and four-drug combinations) of quarter-dose blood pressure lowering drugs demonstrated a stepwise gradient of blood pressure lowering. Two- and three-drug single pill combinations have a favorable balance between greater blood pressure lowering effect, tolerability, adherence, and persistence in blood pressure control [ 12 , 13 , 14 ], As a result, major clinical practice guidelines and the World Health Organization recommend single pill combination therapy [ 3 , 4 , 5 ],

The QUARTET trial [ 15 ] in Australia randomized 591 adults with mild to moderate hypertension and demonstrated a mean −6.9/−5.8 mm Hg greater systolic/diastolic blood pressure lowering effect at 12 weeks with initiation of a four-drug, quarter-dose combination of irbesartan 37.5 mg, amlodipine 1.25 mg, indapamide 0.625 mg, and bisoprolol 2.5 mg (quadpill) compared with irbesartan 150 mg daily alone. This effect was observed even with add-on amlodipine 5 mg at six-week follow-up in either arm among individuals who were not controlled, defined as a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or greater, while both arms remained blinded to initial treatment allocation. Most (>90%) participants in QUARTET identified as White or Asian. It is uncertain if similar effects would be observed in other race/ethnic groups based on previous reports of differential blood pressure lowering effects of some drug classes by race/ethnicity [ 16 ].