An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.172(3); 2000 Mar

Evidence-Based Case Review

Identifying and treating adolescent depression, martha c tompson.

1 Department of Psychology Boston University 64 Cummington St Boston, MA 02215-2407

Fawn M McNeil

Margaret m rea.

2 Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences University of California Los Angeles, CA 90095

Joan R Asarnow

- Understand the importance of diagnosing and treating depression in adolescents

- Identify the symptoms of depression in adolescents and the difference between depression and normal adolescent moods

- Identify suicidal risk in a depressed adolescent

- Understand when a specialty consultation is needed

- Understand what effective treatments are available

By age 18, about 20% of our nation's youth will have had depressive episodes, 1 , 2 with girls at substantially higher risk. 2 Major depressive episodes in adolescence last an average of 6 to 9 months, 2 , 3 6% to 10% of depressed adolescents have protracted episodes, and the probability of recurrence within 5 years is about 70%. 3 Given that depressed people are as likely to seek help in primary care settings as in mental health establishments, 4 primary care physicians may be the first to be aware of this problem in their adolescent patients.

Case history

Wanda S, aged 16 years, comes for her checkup accompanied by her mother. She is in good health and has had no notable illnesses in the past year. However, Wanda complains of difficulty sleeping in the past few months and of frequently being tired. Her mother asks for a few minutes alone to discuss her concerns about her daughter. She states that “Wanda has been much more irritable than her usual self” and that “her teachers have been complaining that she doesn't seem to attend to her work lately and her grades are slipping.” Wanda's mother remembers being an unhappy adolescent herself and asks your advice on how to help her daughter.

When directly questioned, Wanda admits to “feeling pretty bad for the last few months, since school began.” She concedes that she feels sad and blue most days of the week and believes that she is “a loser.” She's been spending more time alone and, despite complaining of chronic boredom, has little energy or desire to engage in recreational activities.

Our conclusions are based on literature searches using both MEDLINE and PsychLIT databases, and most are derived from empiric findings and clinical trials. Because of the relatively modest literature, particularly on treatment, some suggestions are based on published opinions of experts. We have noted when expert opinion is our source.

What does depression look like in adolescents?

According to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders , fourth edition, 5 an adolescent must have five out of nine characteristic symptoms most of the time for at least 2 weeks for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. At least one of these symptoms must be either depressed or irritable mood or a pervasive loss of pleasure or interest in events that were once enjoyed. Many seriously depressed adolescents experience both. For example, a depressed adolescent may feel sad most of the day, act crabby, stop hanging out with friends, and seem to lose her love of soccer.

Summary points

- Adolescent depression is common, and primary care physicians are often in a position to first identify the symptoms

- Depression includes changes in moods, thoughts, behaviors, and physical functioning. Among adolescents, depression may include irritable as well as sad moods

- Unlike normal adolescent moods, depression is severe and enduring and interrupts the adolescent's ability to perform in school, to relate to peers, and to engage in age-appropriate activities

- In assessing the risk of suicide, ask straightforward questions about the adolescent's intent, plan, and means

- Antidepressant medication and psychotherapy may be effective treatments; a combination of these is frequently optimal

- Education about depression with both the adolescent and parents provides a rationale for treatment, may alleviate family misunderstandings, and facilitates recovery

Although all adolescents occasionally become sad, and adolescent angst may be normal and common, symptoms of major depression are more severe in intensity, interfere with social, academic, and recreational activities, and last for months at a time, 2 instead of fluctuating like more typical adolescent ups and downs. 6 Depression occurs as a cluster of signs and symptoms, including emotional, physical, and mental changes that usually signify an alteration from the adolescent's normal personality. 3

Some adolescents present with depressive symptoms but do not meet the full criteria for having major depression. Dysthymic disorder is characterized by milder but more persistent symptoms than major depression. In dysthymic disorder, symptoms are present much of the time for at least one year in adolescents (2 years in adults).

Wanda's physician prescribes a low dose of fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. In addition, the physician refers Wanda for interpersonal therapy to help her cope with the losses and disappointments of the past year, develop new peer relationships, and reintegrate herself into high school activities.

This multifaceted approach will address the physical and psychological symptoms Wanda has been experiencing and provide her with skills she can use to combat future depressive symptoms and interpersonal problems.

What contributes to adolescent depression?

The vulnerability-stress model is useful for understanding depression. According to this model, adolescent depression results from a predisposition for depression, which is then triggered or complicated by environmental stress. The exact nature of the predisposition may include biologic and cognitive factors. This interplay between life's stresses and cognitive and biologic vulnerabilities is important in conceptualizing depression in an adolescent.

An accumulation of adverse life circumstances and events can trigger depression. Family adversity, 7 academic difficulties, 3 chronic medical conditions, 8 and loss in the adolescent's life may increase risk. As Wanda's history illustrates, losses such as her breakup with a boyfriend and failure to make the track team may serve as triggers. Illnesses such as asthma, sickle cell anemia, irritable bowel syndrome, recurrent abdominal pain, and diabetes mellitus may put an adolescent at particular risk. 8

Cognitive models of depression suggest that it is not stressful events and circumstances but rather the tendency toward negative interpretations about these situations that initiates and maintains depression. 9 , 10 When an adverse event occurs, the depressed adolescent often understands the cause of the event as something stable, internal, and global. For example, Wanda fails to make the track team and attributes this failure to being a “loser.” This cause is stable (unlikely to change), internal (her own fault), and global (affecting everything she does).

Vulnerability to depression may result from biologic or genetic factors and lead to numerous biologic changes. First, studies of family history show that offspring of depressed parents are at high risk for depression 11 and that depressed adolescents have high rates of depression among their family members. 12 Wanda's mother may have been depressed during adolescence. Second, as depressions become more severe, biologic changes may occur, including dysregulation of growth hormone and changes in sleep architecture. 6

How do you assess adolescent depression?

The diagnosis of depression is made clinically. Physicians need to ask about changes in an adolescent's moods, feelings, and thoughts; behaviors; daily functioning; and any impairment in that functioning, as well as physical symptoms. Furthermore, a medical explanation (for example, thyroid disease or adrenal dysfunction) or substance misuse needs to be ruled out as possible causes. The best methods of assessment supplement the adolescent's selfreport with reports from parents or guardians and other outside sources. 2 Whereas youths tend to be better reporters of their internal experiences, such as their mood and thoughts, parents tend to be better reporters of overt behaviors, such as disruptive behavior in the classroom and defiance. 13 As in all primary care evaluations, ethnic and cultural factors must also be considered. For example, in some cultures, making eye contact with an authority figure may not be considered proper etiquette, and the failure to do so may not reflect a depressed mood. 3 In recent years, several screening tools for depression have been adapted for use in primary care settings. 14 , 15 The use of these screening techniques can improve the quality of assessments of depression while reducing the time needed for questioning during routine examinations.

How do you assess and intervene when an adolescent is suicidal?

Depression is associated with a markedly increased risk of suicide and attempted suicide. 16 , 17 , 18 About 41% of depressed youths have suicidal ideation, and 21% report a past attempt at suicide. 2 Although many people are concerned that asking directly about suicide may suggest the idea, most depressed youths have suicidal thoughts and are relieved at the opportunity to share them. Unfortunately, adolescents may not volunteer this information unless directly questioned. Often depressed youths have thoughts of death, a desire to die, or a more overt suicidal intention. Asking straightforward, unambiguous questions to assess the risk of suicide is the best strategy. Questions may include “Have you thought that life was not worth living?” “Have you wished you were dead?” “Have you thought about killing yourself?” “What have you thought about doing?” “Have you ever tried to hurt yourself?” or “Have you ever actually tried to kill yourself?” If there is evidence of suicidal thoughts or attempts, it is then critical to establish if the adolescent has the intent, plan, and means to attempt suicide. Questions to ask may include “Are you going to try?” “How would you do it?” and “Do you have a gun (knife, pills)?”

When is a specialty consultation needed?

Depression in adolescents is frequently complicated by other mental health and life problems. Because these additional problems affect management strategies, it is important to screen for comorbid disorders and problems with psychosocial functioning and life stress. If at any point the primary care physician feels uncertain about the diagnosis and/or management strategy, specialty mental health consultation is recommended. Primary care physicians should obtain a consultation with a specialist if any of the following are present: current or past mania, two previous episodes of depression, chronic depression, substance dependence or abuse, eating disorder, a history of being admitted to a hospital for psychiatric problems, or a history of suicide attempts or concerns regarding the risk for suicide.

TREATMENTS EFFECTIVE FOR ADOLESCENT DEPRESSION

Although research on the treatment of adolescent depression is limited, recent clinical trials have identified promising interventions, both pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic. The physician also needs to help the family to understand the adolescent's symptoms.

Although research has clearly documented the use of antidepressant medication for adults with depression, 19 far fewer studies have examined the use of these agents in adolescents. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the first choice in medication for depressed adolescents because of their relatively benign side effects, their safety in overdose, and because they only need to be taken once daily. 3 Both tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are less efficacious in adolescents, are more lethal in overdose, 20 and are not recommended at this time. 3

Cognitive behavior therapies are effective in treating adolescent depression. 21 , 22 They assume that developing more adaptive ways of thinking, understanding events, and interacting with the environment will reduce depressive symptoms and improve a youth's ability to function. The cognitive component of the treatment focuses on helping adolescents identify and interrupt negative or pessimistic thoughts, assumptions, beliefs, and interpretations of events and to develop new, more positive or optimistic ways of thinking. The behavioral component focuses on increasing constructive interactions with others to improve the likelihood of receiving positive feedback.

Interpersonal therapy emphasizes improving relationships. The therapy is brief and focuses on the problems that precipitated the current depressive episode. It helps the adolescent to reduce and cope with stress. Two studies 23 , 24 have shown its effectiveness in reducing depression.

No definitive guidelines have been published for deciding when to begin with medication, psychotherapy, or a combination of medication plus psychotherapy. We have, however, suggested several considerations based on common sense to help clinicians make this decision. 25 , 26 , 27 For example, medication should be considered if an adolescent does not seem interested in thinking about problems, has limited cognitive abilities, is severely depressed with vegetative symptoms, has had two or more episodes of depression, has not responded to 8 to 12 weeks of psychotherapy, or cannot regularly get to therapy sessions. Conversely, psychotherapy should be considered as the first alternative for adolescents who fear medication or do not like taking pills, prefer talking about problems, have complex life stressors that need sorting out, have contraindications to medication (such as pregnancy or breast-feeding), or have not responded to an adequate trial of medication. For some adolescents who have combinations of severe depression, limited cognitive skills, and complex life stressors, it may be best to begin with both medication and psychotherapy.

Parents may have little understanding of the adolescent's symptoms and sometimes interpret falling grades and lack of interest as willful behavior. By giving parents information about the symptoms, causes, and treatments of depression, the physician can help them to help their child to recover, to monitor symptoms, and to facilitate ongoing care. 3 Families differ in their willingness to consider the possibility that their child may have a psychological or psychiatric problem. For personal and/or cultural reasons, some families may be more receptive to a medical model, which identifies the depressive symptoms as part of an illness, and so they are more comfortable with a pharmacologic intervention. Other families may find a cognitive explanation more acceptable and see psychotherapy as a more palatable option. Further, primary care physicians may note that on finding out about their adolescent's depression, parents may feel guilty or feel they are being blamed and thus be resistant to suggestions for interventions. Appropriate education about depression and possible causes may help allay these concerns.

Symptoms of major depressive disorder in adolescents

- Depressed or irritable mood

- Loss of pleasure or interest in activities that were once enjoyed

- Significant weight loss or gain when not dieting, or an increase or decrease in appetite

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Observable slowing of movements and speech or increased agitation

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive and/or inappropriate guilt

- Difficulty concentrating and/or making decisions

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide or a suicide attempt

- For a diagnosis, an adolescent must have at least 5 symptoms, which must include at least one of either of the first 2 symptoms, for at least 2 weeks.

When assessing adolescents for depression who already have chronic illnesses, it is important to look at the symptoms that are less likely to overlap with the physical illness, such as feelings of guilt, worthlessness, and hopelessness. It may be difficult to decipher whether changes in sleep patterns, appetite, and increased fatigue are due to the illness or to depression. 3

Symptoms of dysthymic disorder in adolescents

Depressed or irritable mood must be present for most of the day, more days than not, for at least 1 year. In addition, 2 of the following 6 symptoms must be present:

- Poor appetite or overeating

- Low energy of fatigue

- Low self-esteem

- Poor concentration or difficulty making decisions

- Feelings of hopelessness

During this time, the adolescent has never been without the depressive symptoms for more than 2 months at a time but does not meet criteria for a major depressive episode.

Having assessed thoughts of death, the intention to die, plans for an attempt, the means to commit suicide, and the availability of support, the physician must estimate the degree of risk and make choices for managing the patient's risk of suicide. 3 First, although thoughts of death or thinking of suicide in vague terms suggests a low risk, such symptoms indicate a need for both immediate intervention and close monitoring (because suicidal risk can increase). Second, when the adolescent acknowledges having a plan or means but no intent, emergency care may not be needed if safety can be ensured through involving parents and other support systems. Parents need to be in close proximity and to remove potential means such as firearms, and the adolescent needs to be referred for psychotherapy. However, if the adolescent does not have a supportive family, has access to lethal means, or has other risk factors (for example, a past suicide attempt, family history of suicide, recent exposure to suicide, substance abuse, bipolar illness, mixed state, or severe stress), more intensive interventions are needed, and the adolescent needs to see a mental health specialist. Finally, when the adolescent has intent, plan, and means, the risk for suicide is high. Such adolescents need help immediately, and psychiatric emergency care may be needed. 3 Regardless of risk, follow-up care is essential to tackle the concerns that contributed to the adolescent's suicidal feelings.

Empirically supported treatment options

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors Alters dysfunctional neurotransmitter systems

Cognitive behavioral therapy Monitors and changes dysfunctional ways of thinking

Interpersonal therapy Improves interpersonal skills and problem-solving abilities

Funding: National Institutes of Health, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research

SHELLEY S. SELPH, MD, MPH, AND MARIAN S. MCDONAGH, PharmD

Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(10):609-617

Patient information: See related handout on depression in children and adolescents , written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

The prevalence of major unipolar depression in children and adolescents is increasing in the United States. In 2016, approximately 5% of 12-year-olds and 17% of 17-year-olds reported experiencing a major depressive episode in the previous 12 months. Screening for depression in adolescents 12 years and older should be conducted annually using a validated instrument, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9: Modified for Teens. If the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment should be initiated for persistent, moderate, and severe depression. Active support and monitoring may be sufficient for mild, self-limited depression. For more severe depression, evidence indicates greater response to treatment when psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy) and an antidepressant are used concurrently, compared with either treatment alone. Fluoxetine and escitalopram are the only antidepressants approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of depression in children and adolescents. Fluoxetine may be used in patients older than eight years, and escitalopram may be used in patients 12 years and older. Monitoring for suicidality is necessary in children and adolescents receiving pharmacotherapy, with frequency of monitoring based on each patient's individual risk. The decision to modify treatment (add, increase, change the medication or add psychotherapy) should be made after about four to eight weeks. Consultation with or referral to a mental health subspecialist is warranted if symptoms worsen or do not improve despite treatment and for those who become a risk to themselves or others.

The prevalence of depression is increasing among youth in the United States. The 2005 to 2014 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, which included 172,495 adolescents 12 to 17 years of age, found that the percentage of adolescents who experienced one or more major depressive episodes in the previous 12 months increased from 9% in 2005 to 11% in 2014. 1 In 2016, this percentage was approximately 13% (5% in 12-year-olds, 13% in 14-year-olds, and 17% in 17-year-olds), and although 70% of youths experienced severe impairment from depression, only about 40% received treatment. 1 Treatment rates have changed little since 2005, raising concern that adolescents are not receiving needed care for depression. 1

Risk Factors

Increased risk of depression in children and adolescents may be due to biologic, psychological, or environmental factors ( Table 1 ) . 2 – 34 In children 12 years and younger, depression is slightly more common in boys than in girls (1.3% vs. 0.8%). 35 However, after puberty, adolescent girls are more likely to experience depression. 35

Screening for Depression

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening children and adolescents 12 to 18 years of age for major depressive disorder with adequate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up. 36 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports the USPSTF recommendation. 37 In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics endorsed the Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC), which recommends screening adolescents 12 years and older annually for depressive disorders using a self-report screening tool. 38 , 39

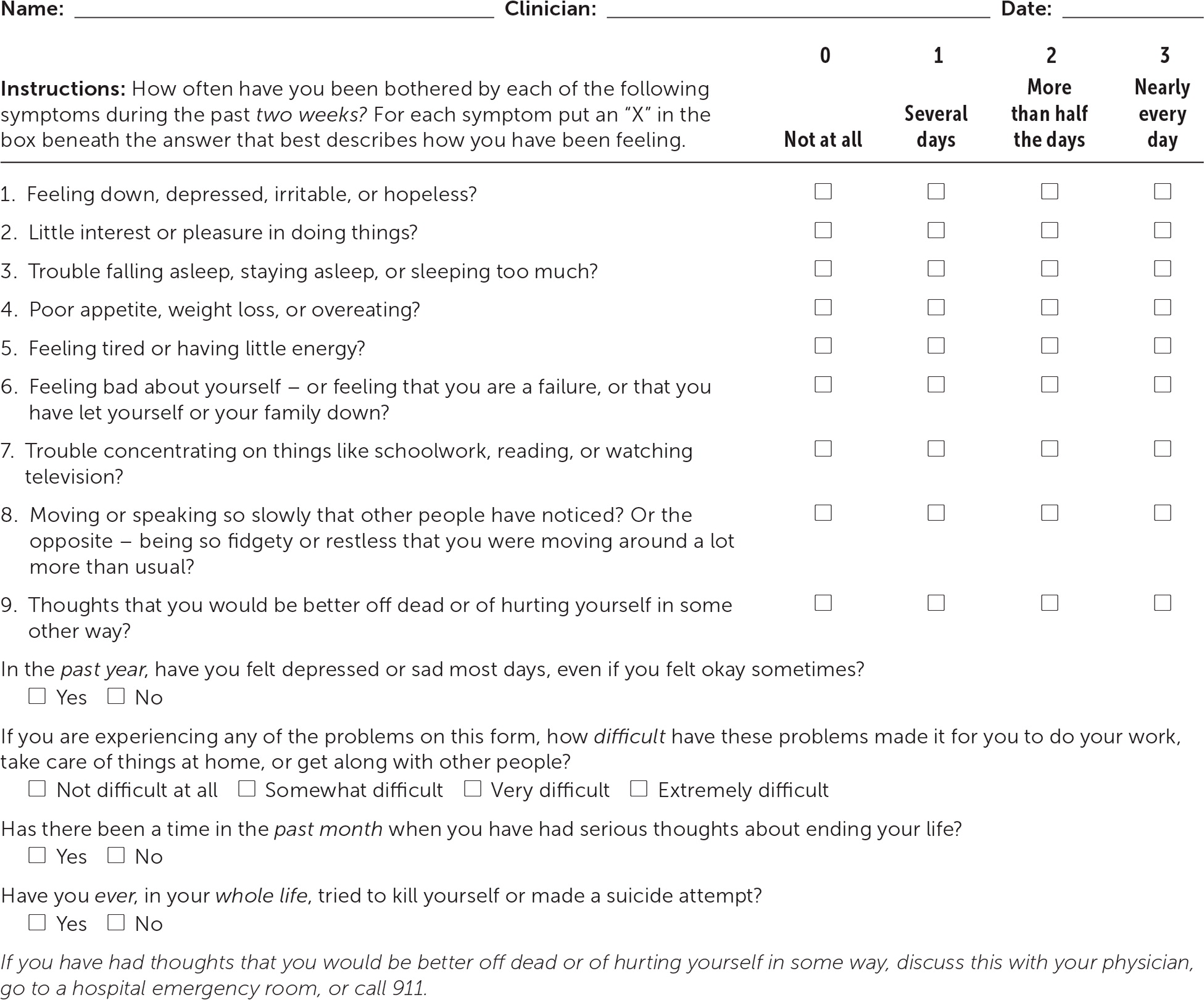

There are various instruments to screen adolescents for depression. One popular instrument for use in primary care is the Patient Health Questionnaire-9: Modified for Teens (also called PHQ-A) for patients 11 to 17 years of age. The PHQ-A is shown in Figure 1 and Table 2 , along with four questions not used in scoring that address suicidality, dysthymia, and severity of depression. 40 , 41

Clinical Presentation

The presenting sign of major depressive disorder may be insomnia or hypersomnia; weight loss or gain; difficulty concentrating; loss of interest in school, sports, or other previously enjoyable activities; increased irritability; or feeling sad or worthless. 42 To distinguish between normal grief, such as after the loss of a loved one, and a major depressive episode, it may be helpful to determine whether the predominant symptom is a sense of loss or emptiness (more typical of grief) vs. a persistent depressed mood with the inability to anticipate future enjoyable events (more typical of depression). 42

When a child or adolescent screens positive using a formal screening tool, such as the PHQ-A, or when he or she presents with symptoms indicating a possible depressive disorder, the primary care physician should assess whether the symptoms are a result of a major depressive episode or another condition that could present with similar symptoms. To diagnose major depressive disorder, criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed. (DSM-5), must be met and not explained by substance abuse, medication use, or other medical or psychological condition. 42 The full DSM-5 criteria are available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/1015/p508.html#afp20181015p508-t6 . Some children may develop a cranky mood or irritability rather than sadness.

Medical conditions that may present similarly to depression include hypothyroidism, anemia, autoimmune disease, and vitamin deficiency. Laboratory tests that may be helpful in ruling out common medical conditions that could be mistaken for depression include complete blood count; comprehensive metabolic profile panel; an inflammatory biomarker, such as C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate; thyroid-stimulating hormone; vitamin B 12 ; and folate.

Other psychological conditions that may present similarly to major depressive disorder include persistent depressive disorder (also called dysthymia) and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. If a child or adolescent has a depressed mood for more days than not for at least one year, the diagnosis may be persistent depressive disorder, which is often treated the same as a major depressive episode (e.g., antidepressants, psychotherapy). 42 If a child or adolescent is predominantly angry with temper outbursts, the diagnosis may be disruptive mood dysregulation disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder. 42

Symptoms of bipolar disorder, eating disorders, and conduct disorders may also overlap with major depressive disorder. Children and adolescents may have more than one psychiatric diagnosis concurrently, such as comorbid depression and anxiety. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 74% of children three to 17 years of age who have depression also have anxiety, and 47% of children with depression also have a behavior problem. Therefore, a thorough assessment is needed, with possible mental health consultation or referral.

Risk Assessment for Suicide

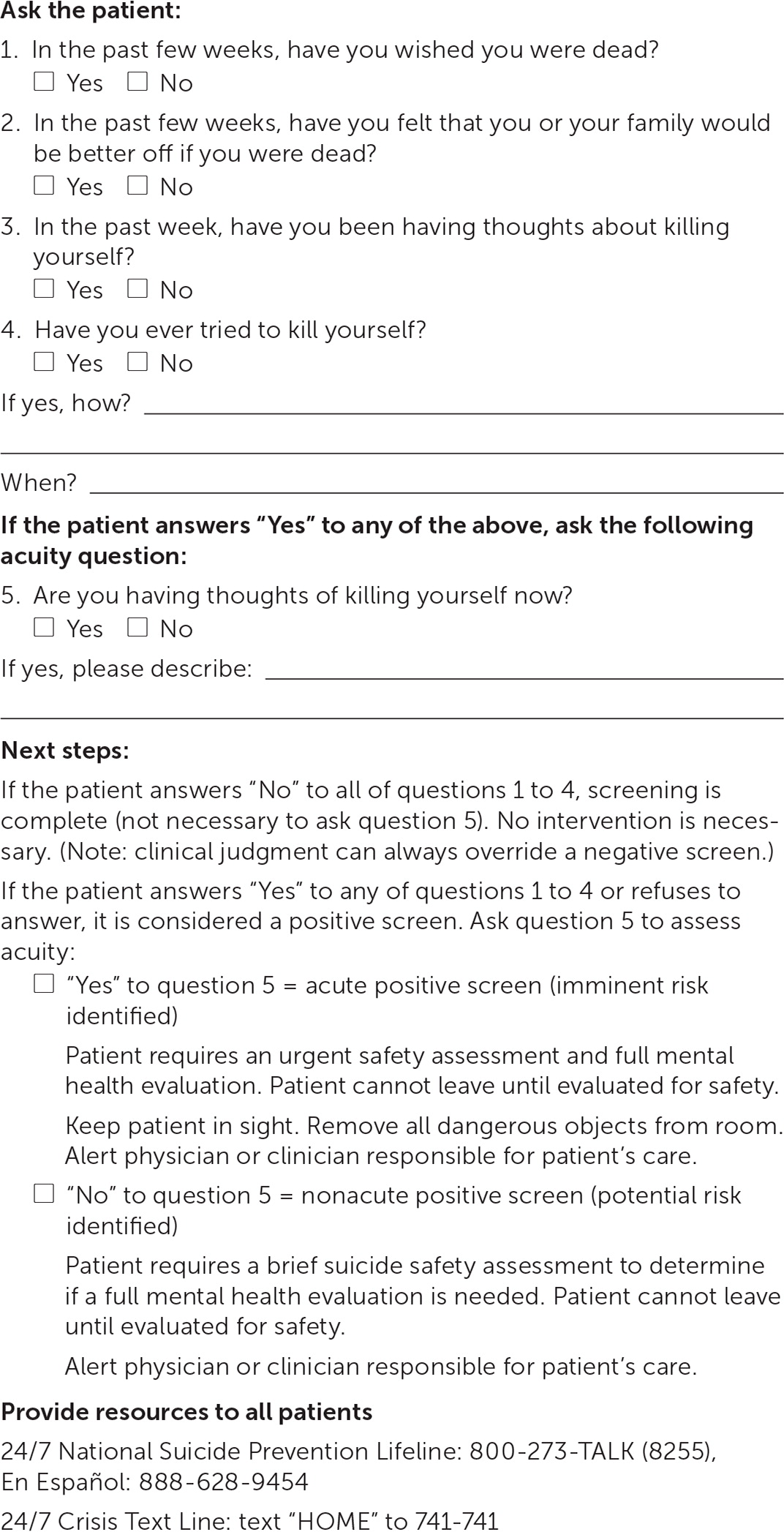

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people 10 to 24 years of age after unintentional injury. 43 Depression is a risk factor for suicide, but at-risk youth can be easily missed without specific suicide screening. In one study, nurses in a pediatric emergency department used the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) tool to assess suicide risk in 970 adolescents who presented with psychiatric problems. 44 Of those who screened positive, 53% did not present with suicide-related problems. The sensitivity and specificity for a return visit to the emergency department because of suicidality within six months were 93% and 43%, respectively, for a positive predictive value of 10% and a negative predictive value of 99%. 44 The ASQ screening test is shown in Figure 2 . 45 The complete ASQ toolkit is available at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/index.shtml#outpatient .

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

The GLAD-PC guidelines recommend that primary care physicians counsel families and patients about depression and develop a treatment plan that includes setting specific goals involving functioning at home, at school, and with peers. 38 For example, a treatment plan might include treating others with respect, attending family meals, keeping up with schoolwork, and spending time in activities with supportive peers. Additionally, a safety plan should be established that limits access to lethal means, such as removing firearms from the home or locking them up. It should also provide a way for the patient to communicate during an acute crisis (e.g., providing phone numbers for people to contact if suicidal thoughts occur, creating a list of coping skills, educating the parents on how to recognize if the patient is a risk to self or others). 38 If the danger of suicide becomes imminent, psychiatric evaluation in a hospital emergency department or psychiatry crisis clinic is needed.

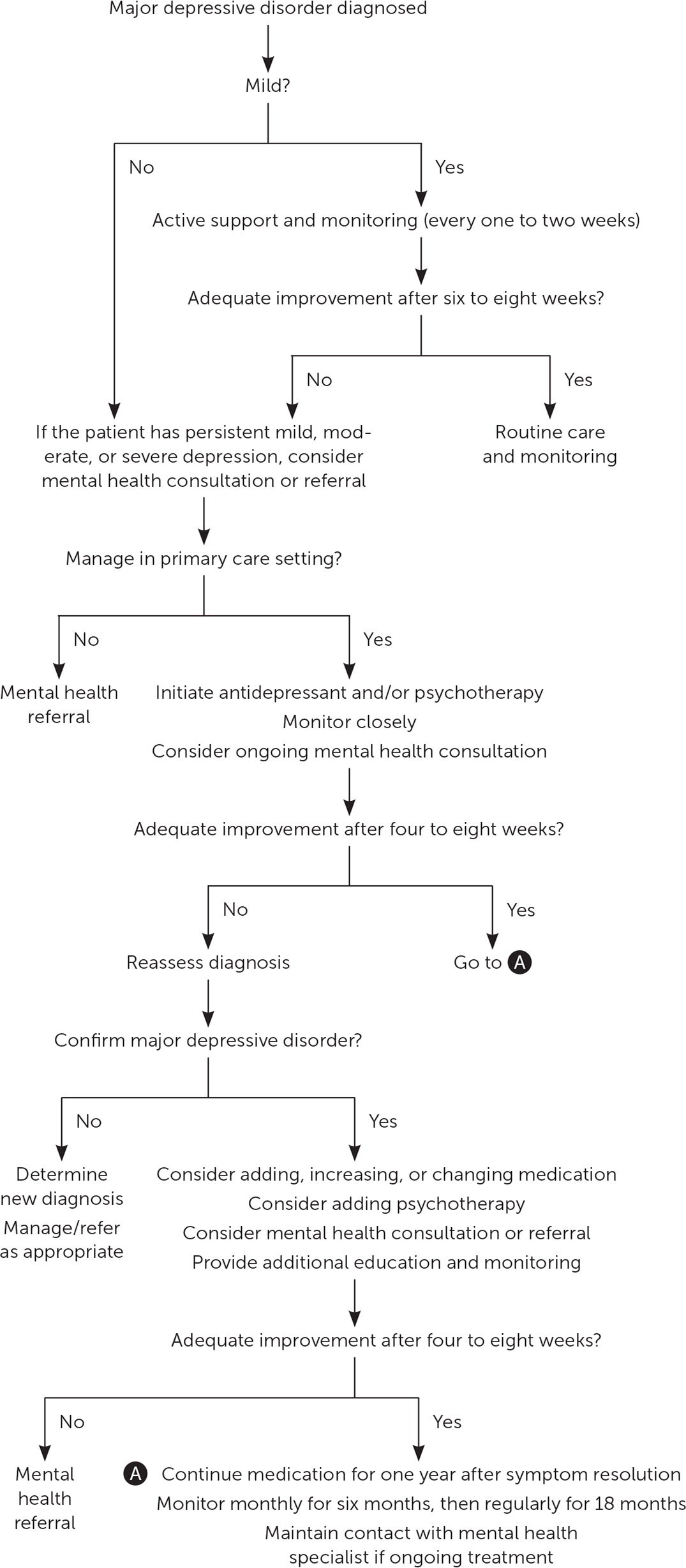

For mild depression, which may be short-lived, primary care physicians should consider active support such as counseling about depression and treatment options, facilitating caregiver/patient depression self-management, and monitoring the patient every week or two for six to eight weeks before initiating pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy. 46 – 50 According to the DSM-5, although the symptoms of mild depression are distressing, they are manageable and result in only minor impairment in functioning, whereas severe depression causes more seriously distressing, unmanageable symptoms that greatly impact functioning. See Figure 3 for a suggested approach to the management of depression in children and adolescents. 43 , 50

ONGOING MANAGEMENT

Treatment options for children and adolescents with depression include psychotherapy and anti-depressants. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is a form of talk therapy that focuses on changing behaviors by correcting faulty or potentially harmful thought patterns and generally includes five to 20 sessions. Whereas CBT focuses on cognition and behaviors, interpersonal psychotherapy concentrates on improving interpersonal relationships and typically includes around 12 to 16 sessions.

Fluoxetine (Prozac) and escitalopram (Lexapro) are the only two medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Fluoxetine is approved for patients eight years and older, and escitalopram is approved for patients 12 years and older. There are concerns of increased suicidality with the use of fluoxetine and escitalopram in this population. 51 Although there were no suicides in trials of children and adolescents taking antidepressants, suicidal thoughts and behaviors were increased compared with placebo (4% vs. 2%). 51 Children and adolescents who are taking these medications should be monitored for suicidality. The frequency of monitoring should be based on the individual patient's risk (e.g., weekly monitoring at treatment onset, monthly monitoring in a child showing steady improvement on antidepressants).

PHARMACOTHERAPY ALONE

Three systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials including children and adolescents with major depressive disorder support the use of fluoxetine as the first-line antidepressant medication. 52 – 54 Two reviews also support the use of escitalopram as initial therapy. 52 , 54 However, the effects of fluoxetine and escitalopram as monotherapy were often similar to placebo, depending on the outcome measured. Tricyclic antidepressants, other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reupta ke inhibitors have not been shown to be effective in treating depression in children and adolescents. 46 , 52 – 54 If neither fluoxetine nor escitalopram is effective and antidepressant therapy is desired, referral to a child or adolescent psychiatrist is recommended.

PSYCHOTHERAPY ALONE

Evidence is mixed for the use of CBT as monotherapy in children and adolescents with depression. A systematic review for the USPSTF found no benefit of CBT on remission or recovery and inconsistent effects on symptoms, response, and functioning. 54 One trial of youth with major depression who declined antidepressants found that compared with self-selected treatment as usual, 12 weeks of CBT was associated with shorter time to treatment response and remission and improved depression scores through week 52 but not in weeks 53 to 104. 55 In children and adolescents with subclinical depression, one systematic review (19 trials) found moderate-quality evidence that CBT is associated with a small effect on depressive symptoms vs. waitlist or no treatment. 56

COMBINED THERAPY

Evidence from a good-quality randomized trial suggests that adolescents are most likely to achieve remission with 12 weeks of combined therapy with fluoxetine and CBT (37%; number needed to treat = 4) compared with either therapy alone (23% with fluoxetine; number needed to treat = 11; 16% with CBT) or placebo (17%). 47 , 57 Suicidality declined with duration of treatment for all therapies, but the decline was less steep for fluoxetine alone (26.2% at baseline to 13.7% at week 36) vs. combination therapy (39.6% to 2.5%) and CBT alone (25.2% to 3.9%). 47 , 57

In another trial of adolescents who achieved at least a 50% decrease in depression scores following six weeks of fluoxetine treatment, those who were randomized to receive the addition of CBT to fluoxetine therapy for six months were less likely to relapse at 78 weeks compared with continued fluoxetine monotherapy (36% vs. 62%). 58

Children and adolescents with moderate or severe depression or persistent mild depression should be treated with fluoxetine or escitalopram in conjunction with CBT or other talk therapy. 47 , 57 – 59 If combination therapy is not used, monotherapy with an antidepressant or psychotherapy is recommended, although the likelihood of benefit is lower. 46 , 52 – 56

Reassessing Treatment and Treatment Duration

One trial found that early reassessment of depression is valuable. 43 In this study, all youth received interpersonal psychotherapy and were randomized to a four- or eight-week follow-up assessment for treatment modification. If additional treatment was needed because of inadequate response, patients were further randomized to add-on fluoxetine or more intense (twice weekly) psychotherapy. Those who were reassessed at four weeks improved the most at 16 weeks (a difference of 5.7 points on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; scores on this scale can range from 0 to 58 points, with a score of 0 to 7 considered normal and a score of 20 associated with moderate depression; P < .05). Additionally, those who began add-on fluoxetine at four weeks had better posttreatment depression scores than those who began intense interpersonal psychotherapy at eight weeks, although there was no difference in global assessment scores between the two groups.

Treatment duration for talk therapy in adolescents with unipolar depression is typically six months or less, but longer treatment may be necessary. Although good evidence regarding the duration of medication treatment in adolescents with depression is lacking, the GLAD-PC guidelines recommend continuing medication for one year beyond the resolution of symptoms. 50

Referral to a Mental Health Subspecialist

If a child or adolescent does not improve after initial treatment for depression, the primary care physician may add, change, or increase a medication and may consider referral for psychotherapy. Referral to a licensed mental health professional is appropriate at any point in the treatment process. However, if the depression does not improve or the child deteriorates even with treatment, consultation with or referral to a child or adolescent psychiatrist is necessary.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Clark, et al. 60 ; Bhatia and Bhatia 61 ; and Son and Kirchner . 62

Data Sources: We conducted general and targeted searches using Essential Evidence Plus, Ovid Medline, PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and UpToDate, including the key words children or adolescents with depression. Search dates: November 2018 to January 2019, and September 27, 2019.

The authors thank Alycia Brown, MD, for her review of the manuscript and Ngoc Wasson, MPH, and Chandler Weeks, BS, for help with formatting the manuscript.

National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression. Accessed December 13, 2018. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml#part_155031

Xie B, Unger JB, Gallaher P, et al. Overweight, body image, and depression in Asian and Hispanic adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(4):476-488.

Shankar M, Fagnano M, Blaakman SW, et al. Depressive symptoms among urban adolescents with asthma: a focus for providers. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(6):608-614.

Buchberger B, Huppertz H, Krabbe L, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;70:70-84.

Sibbitt WL, Brandt JR, Johnson CR, et al. The incidence and prevalence of neuropsychiatric syndromes in pediatric onset systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(7):1536-1542.

Benoit A, Lacourse E, Claes M. Pubertal timing and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: the moderating role of individual, peer, and parental factors. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(2):455-471.

Kounali D, Zammit S, Wiles N, et al. Common versus psychopathologyspecific risk factors for psychotic experiences and depression during adolescence. Psychol Med. 2014;44(12):2557-2566.

Song SJ, Ziegler R, Arsenault L, et al. Asian student depression in American high schools: differences in risk factors. J Sch Nurs. 2011;27(6):455-462.

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):12. Accessed September 29, 2019. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/6/e20161878.long

Whitehouse AJ, Durkin K, Jaquet EK, et al. Friendship, loneliness and depression in adolescents with Asperger's syndrome. J Adolesc. 2009;32(2):309-322.

De-la-Iglesia M, Olivar JS. Risk factors for depression in children and adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Scientific World Journal. 2015;2015:127853.

McDonald K. Social support and mental health in LGBTQ adolescents: a review of the literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(1):16-29.

Lavigne JV, Herzing LB, Cook EH, et al. Gene × environment effects of serotonin transporter, dopamine receptor D4, and monoamine oxidase A genes with contextual and parenting risk factors on symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, and depression in a community sample of 4-year-old children. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(2):555-575.

Ferreiro F, Seoane G, Senra C. A prospective study of risk factors for the development of depression and disordered eating in adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40(3):500-505.

Bisaga K, Whitaker A, Davies M, et al. Eating disorder and depressive symptoms in urban high school girls from different ethnic backgrounds. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(4):257-266.

Pabayo R, Dias J, Hemenway D, et al. Sweetened beverage consumption is a risk factor for depressive symptoms among adolescents living in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(17):3062-3069.

Kullik A, Petermann F. Attachment to parents and peers as a risk factor for adolescent depressive disorders: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44(4):537-548.

Torres-Rodríguez A, Griffiths MD, Carbonell X, et al. Internet gaming disorder in adolescence: psychological characteristics of a clinical sample. J Behav Addict. 2018;7(3):707-718.

Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Frøyland LR. Is video gaming, or video game addiction, associated with depression, academic achievement, heavy episodic drinking, or conduct problems?. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(1):27-32.

Orth U, Robins RW, Widaman KF, et al. Is low self-esteem a risk factor for depression? Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(2):622-633.

Muris P, van den Broek M, Otgaar H, et al. Good and bad sides of self-compassion: a face validity check of the self-compassion scale and an investigation of its relations to coping and emotional symptoms in non-clinical adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(8):2411-2421.

Orchard F, Reynolds S. The combined influence of cognitions in adolescent depression: biases of interpretation, self-evaluation, and memory. Br J Clin Psychol. 2018;57(4):420-435.

Rawal A, Rice F. Examining overgeneral autobiographical memory as a risk factor for adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(5):518-527.

Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, et al. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:274-281.

Kodish T, Herres J, Shearer A, et al. Bullying, depression, and suicide risk in a pediatric primary care sample [published correction appears in Crisis . 2016;37(3):247]. Crisis. 2016;37(3):241-246.

Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, et al. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: a scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(8):770-777.

Adams J, Mrug S, Knight DC. Characteristics of child physical and sexual abuse as predictors of psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;86:167-177.

Cohen JR, McNeil SL, Shorey RC, et al. Maltreatment subtypes, depressed mood, and anhedonia: a longitudinal study with adolescents [published online December 27, 2018]. Psychol Trauma . Accessed September 29, 2019. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ftra0000418

Lai BS, La Greca AM, Auslander BA, et al. Children's symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression after a natural disaster: comorbidity and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(1):71-78.

Tang B, Liu X, Liu Y, et al. A meta-analysis of risk factors for depression in adults and children after natural disasters. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:623.

Kremer P, Elshaug C, Leslie E, et al. Physical activity, leisure-time screen use and depression among children and young adolescents. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(2):183-187.

Korczak DJ, Madigan S, Colasanto M. Children's physical activity and depression: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20162266.

Uddin M, Jansen S, Telzer EH. Adolescent depression linked to socioeconomic status? Molecular approaches for revealing premorbid risk factors. Bioessays. 2017;39(3):03. Accessed September 29, 2019. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bies.201600194

Shanahan L, Copeland WE, Costello EJ, et al. Child-, adolescent- and young adult-onset depressions: differential risk factors in development?. Psychol Med. 2011;41(11):2265-2274.

Douglas J, Scott J. A systematic review of gender-specific rates of uni-polar and bipolar disorders in community studies of pre-pubertal children. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(1):5-15.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Depression in children and adolescents: screening. February 2016. Accessed August 12,2019. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1

American Academy of Family Physicians. Adolescent health clinical recommendations and guidelines. Depression – clinical preventive service recommendation. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/browse/topics.tag-adolescent-health.html

Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, et al.; GLAD-PC Steering Group. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): part I. Practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174081.

The Reach Institute. Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC) Toolkit. Accessed August 12, 2019. http://www.glad-pc.org

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) screeners. Accessed August 12, 2019. http://www.phqscreeners.com

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. PHQ-9: Modified for Teens. Accessed August 12, 2019. http://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/member_resources/toolbox_for_clinical_practice_and_outcomes/symptoms/GLAD-PC_PHQ-9.pdf

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2014.

Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Bernstein G, et al. Critical decision points for augmenting interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents: a pilot sequential multiple assignment randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):80-91.

Ballard ED, Cwik M, Van Eck K, et al. Identification of at-risk youth by suicide screening in a pediatric emergency department. Prev Sci. 2017;18(2):174-182.

National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide risk screening tool. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/index.shtml#outpatient

Weihs KL, Murphy W, Abbas R, et al. Desvenlafaxine versus placebo in a fluoxetine-referenced study of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):36-46.

Kennard B, Silva S, Vitiello B, et al.; TADS Team. Remission and residual symptoms after short-term treatment in the Treatment of Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1404-1411.

Clarke GN, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adolescent depression: efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):272-279.

Wagner KD, Jonas J, Findling RL, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram in the treatment of pediatric depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):280-288.

Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, et al. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): part II. treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174082.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Suicidality in children and adolescents being treated with antidepressant medications. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/suicidality-children-and-adolescents-being-treated-antidepressant-medications

Ignaszewski MJ, Waslick B. Update on randomized placebo-controlled trials in the past decade for treatment of major depressive disorder in child and adolescent patients: a systematic review [published online July 31, 2018]. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol . Accessed September 29, 2019. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/cap.2017.0174?journalCode=cap

Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2016;388(10047):881-890.

Forman-Hoffman VL, McClure E, McKeeman J, et al. Screening for major depressive disorder among children and adolescents: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):342-349.

Clarke G, DeBar LL, Pearson JA, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care for youth declining antidepressants: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20151851.

Oud M, de Winter L, Vermeulen-Smit E, et al. Effectiveness of CBT for children and adolescents with depression: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;57:33-45.

March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes [published correction appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry . 2008;65(1):101]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1132-1143.

Emslie GJ, Kennard BD, Mayes TL, et al. Continued effectiveness of relapse prevention cognitive-behavioral therapy following fluoxetine treatment in youth with major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(12):991-998.

Foster S, Mohler-Kuo M. Treating a broader range of depressed adolescents with combined therapy. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:417-424.

Clark MS, Jansen KL, Cloy JA. Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(5):442-448. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/0901/p442.html

Bhatia SK, Bhatia SC. Childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(1):73-80. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0101/p73.html

Son SE, Kirchner JT. Depression in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(10):2297-2308. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2000/1115/p2297.html

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2019 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 07 August 2023

A global mental health approach to depression in adolescence

- Ana Paula Donnelly 1

Nature Mental Health volume 1 , pages 527–528 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

158 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Adolescence is one of the most important transition periods in life, in which self-esteem and identity are being shaped and individuals experience profound social and physical transformations. In recent years, a concerning increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders in adolescents has been documented, prompting the mental health research community to prioritize understanding the risks of developing psychiatric disorders as well as factors that might be protective. Nature Mental Health spoke about depression in adolescence with Christian Kieling , an associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the School of Medicine at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil. Kieling is leading an international project called ‘Identifying depression early in adolescence ( IDEA )’ that brings a global health approach to the topic.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nature Mental Health https://www.nature.com/natmentalhealth/

Ana Paula Donnelly

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ana Paula Donnelly .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Donnelly, A.P. A global mental health approach to depression in adolescence. Nat. Mental Health 1 , 527–528 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00107-y

Download citation

Published : 07 August 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00107-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Open access

- Published: 02 October 2020

Depression in adolescence: a review

- Diogo Beirão ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5612-8941 1 ,

- Helena Monte 1 ,

- Marta Amaral 1 ,

- Alice Longras 1 ,

- Carla Matos 1 , 2 &

- Francisca Villas-Boas 1

Middle East Current Psychiatry volume 27 , Article number: 50 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

50k Accesses

16 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Depression is a common mental health disease, especially in mid to late adolescence that, due to its particularities, is a challenge and requires an effective diagnosis. Primary care providers are often the first line of contact for adolescents, being crucial in identifying and managing this pathology. Besides, several entities also recommend screening for depression on this period. Thus, the main purpose of this article is to review the scientific data regarding screening, diagnosis and management of depression in adolescence, mainly on primary care settings.

Comprehension of the pathogenesis of depression in adolescents is a challenging task, with both environmental and genetic factors being associated to its development. Although there are some screening tests and diagnostic criteria, its clinical manifestations are wide, making its diagnosis a huge challenge. Besides, it can be mistakenly diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders, making necessary to roll-out several differential diagnoses. Treatment options can include psychotherapy (cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal therapy) and/or pharmacotherapy (mainly fluoxetine), depending on severity, associated risk factors and available resources. In any case, treatment must include psychoeducation, supportive approach and family involvement. Preventive programs play an important role not only in reducing the prevalence of this condition but also in improving the health of populations.

Depression in adolescence is a relevant condition to the medical community, due to its uncertain clinical course and underdiagnosis worldwide. General practitioners can provide early identification, treatment initiation and referral to mental health specialists when necessary.

Adolescence is an important period in developing knowledge and skills, learning how to manage emotions and relationships and acquiring attributes and abilities for adulthood. Depression in adolescence is a common mental health disease with a prevalence of 4–5% in mid to late adolescence [ 1 ]. It is a major risk factor for suicide and can also lead to social and educational impairments. Consequently, identifying and treating this disorder is crucial.

General practitioners and primary care providers are frequently the first line of contact for adolescents in times of distress and can be crucial to identify mental health issues amongst these patients. They can facilitate early identification of depression, initiate treatment and refer the adolescents for mental health specialists [ 2 ]. It is vital to make a timely and accurate diagnosis of depression in adolescence and a correct differential diagnosis from other psychiatric disorders, due to the recurrent nature of this condition and its association with poor academic performance, functional impairment and problematic relationships with parents, siblings and peers. Furthermore, depression at this age is strongly related to suicidal ideation and attempts [ 2 ].

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening adolescents for depressive disorder by the General Practitioners [ 2 , 3 ]. Guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) state that adolescent patients should be screened annually for depression in Primary Care with a formal self-report screening tool [ 4 ]. AAP recommends that Primary Care clinicians should evaluate for depression in those who screen positive on the screening tool, in those who present with any emotional problem as the chief complaint and in those in whom depression is highly suspected despite a negative screen result [ 4 ].

The present work consists of a review on the depression in the adolescent, summarizing data published in scientific papers in the last years, regarding the epidemiology of the disease, its pathogenesis and risk factors, screening and diagnosis tools and its management and treatment. Our research focused on research papers published between January 2010 and March 2020 in the area. Other research papers not included in this first search were included due to their interest and value to the subject. The keywords, used in different permutations and combinations, included the following: depression, adolescence, overview, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of depression is significantly linked to age, being low in children (< 1%) and increasing throughout childhood and adolescence. Nevertheless, the prevalence of depression in adolescence varies significantly between studies and reports. A reported prevalence in Great Britain was 4%, whereas in the USA was 2.1% and in France was 11.0% [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Nevertheless, a systematic review from 2013 stated the life prevalence of depression varies from 1.1 to 14.6% [ 8 ].

A possible factor for the reported increase during adolescence is the set of social and biological changes characteristic of post-pubertal phase, such as enhanced social understanding and self-awareness, brain circuits changes involved in responses to reward and danger and increased reported stress levels [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

Regarding differences between genders, while no significant differences are found in depression during childhood, depression during adolescence has a strong female preponderance, similar to adulthood [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. This difference is still observed between distinct epidemiological and clinical samples and across various methods of assessment. As such, it is unlikely due to differences in help-seeking or reporting of symptoms and more closely tied to female hormonal changes, which suggests a direct link to hormone-brain relations [ 15 ].

Pathogenesis

Comprehension of the pathogenesis of depression in adolescents is a challenging task, due to its heterogeneous clinical presentation and diverse causes.

Putative risk factors, potentially modifiable during adolescence without professional intervention, are substance use (alcohol, cannabis and other illicit drugs, tobacco), diet and weight [ 16 ].

Alcohol use is known to have neurotoxic effects during this developmentally sensitive period. Cannabis and other illicit drugs can have an impact on serotonin and other neurotransmitters causing an increase in depressive symptoms. Furthermore, alcohol, cannabis and other illicit drug use have various deleterious social and academic consequences for the adolescent which could increase their risk for depression [ 16 ].

The relationship between tobacco use and depression is unclear. However, it has been proposed that this linkage may arise from the effects of nicotine on neurotransmitter activity in the brain, causing changes to neurotransmitter activity [ 17 ]. Overweight can have a negative impact on self-image which elevates the risk for depression. Moreover, depressed people may lead a less healthy lifestyle and suffer from deregulation in the stress response system, which may contribute to weight gain [ 16 ].

Association between depression and environmental factors, such as exposures to acute stressful events (personal injury, bereavement) and chronic adversity (maltreatment, family discord, bullying by peers, poverty, physical illness), has been subject of papers. Stressful life events seem more strongly associated with first onset rather than recurrence, and risk is considerably greater in girls and in adolescents who have multiple negative life events. The most important factors are chronic and severe relationship stressors [ 18 ]. A significant interaction was found between exposure to maternal threatening behaviours and deficits in emotional clarity in relation to depressive symptom severity [ 19 ].

Genetic factors can also play a very important role in the pathogenesis. Many reports suggest that a variant (5-HTTLPR) in the serotonin transporter gene might increase the risk of depression, but only in the presence of adverse life stressors or early maltreatment. The findings are less robust in adolescent boys than girls. This gene variant has also been reported to affect fear-related and danger-related brain circuitry, which is altered in depression. However, such findings seem to vary not only by genotype but also by age, sex, and severity of symptoms, and are also reliant on good quality measures of adversity and depression [ 18 , 20 ].

Two interrelated neural circuits and associated modulatory systems have been closely linked to risk for depression. One circuit connects the amygdala to the hippocampus and ventral expanses of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and is linked to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity. Disruption of this circuit links depression to stress-related enhancements in HPA-stress systems, such as higher than expected cortisol concentrations, and activity in the serotonergic system. Psychosocial stress, sex hormones and development have also been linked to changing activity in this circuit, with evidence that this circuit matures after adolescence. High concentrations of sex steroid receptors have been identified within this circuit and might provide a biological mechanism for why girls have higher risk of depression than boys. The other key circuit implicated in depression encompasses the striatum and its connection to both the PFC and ventral dopamine-based systems. Like the first circuit, this one also continues to mature through adolescence. Sex differences emerge in both circuits. Research into this reward circuit implies that reduced activity is linked with expression of and risk for depression. Reduced striatal and PFC activity during tasks involving rewards has been recorded both in individuals with major depression and in those with depressed parents. Both inherited factors and stress-related perturbations seem to contribute to these changes [ 18 , 21 ].

Temperament and character traits are also important factors in the pathogenesis of depression in adolescence. According to Cloninger, temperament is responsible for automatic and emotional responses to environmental stimuli and encompasses four dimensions: novelty seeking, exploratory activity, harm avoidance, reward dependence and persistence [ 22 ]. In contrast, character develops across the lifespan and is influenced by social and cultural experiences. Three dimensions are distinguished: self-directedness, cooperativeness and self-transcendence [ 23 ]. Studies showed that depressed patients present higher novelty seeking, harm avoidance and lower reward dependence, persistence, self-directedness and cooperativeness compared to healthy individuals [ 23 , 24 ].

Primary care providers are frequently the first contact during times of distress and can be crucial to identify mental health issues allowing for an earlier depression diagnosis, treatment and referral [ 2 ].

The symptoms can differ from the adult population. In comparison to it, adolescents tend to have more frequently somatic symptoms, anxiety, disruptive behaviour and personality disorders [ 25 ].

The fact that these symptoms are common in other disorders such as hypothyroidism, anaemia, sleep apnoea or other chronic diseases makes the diagnosis more challenging to establish in these subjects [ 26 ].

Screening tools

The screening of adolescents for depression is an essential tool for early detection of this disorder. USPSTF and AAP recommend the screening of adolescents in primary care settings [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 25 , 26 , 27 ].

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) are the most commonly used, outperforming other screening tools in the identification of major depressive disorder among adolescents [ 2 , 28 ].

Originally developed as a depression symptom rating scale for the adult population, BDI is widely used among adults and adolescents and mainly in research. It is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms, scored from “0” to “3”. Participants are asked to respond to each item based on their experiences within the past 2 weeks. The total score can range from 0 to 63, with higher scores meaning higher levels of depressive symptoms [ 29 ]. In primary care settings, an adapted version (BDI-PC) is often used, which consists of a 7-item self-report instrument, with a cut-off of 4 points for major depression [ 30 ]. Good performance has also been shown using BDI, with sensitivity ranging from 84 to 90% and specificity ranging from 81 to 86% [ 3 ].

The PHQ-A is the depression module of a 67-item questionnaire that can be used to screen for depression among adolescent primary care patients. Composed of 9 questions, it can be entirely self-administered by the patient and evaluates symptoms experienced in the 2 weeks prior. It measures functional impairment and inquiries about suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [ 31 ]. The PHQ-A study had the highest positive predictive value, as well as a sensitivity and specificity of 73% and 94%, respectively [ 3 ].

Diagnostic tools

Diagnosis of depression in adolescents is established through the criteria described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [ 32 ]. The evaluation of patients should be made through interviews, alone and with the patient’s family and/or caregivers and should include an assessment of functional impairment in different domains and other existing psychiatric conditions [ 4 ].

DSM-5 establishes the diagnosis of major depressive disorder as a period of at least 2 weeks during which there is a depressed mood or the loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities, and, additionally, at least four additional symptoms from a list that includes changes in weight, sleep disturbances, changes in psychomotor activity, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, impaired concentration or ability to make decisions, or suicidal ideation. Additionally, it states that, in adolescents, depressed mood can be replaced by irritability or crankiness, a sign that can be neglected during assessment or by caregivers. This presentation should be differentiated from a pattern of irritability when frustrated [ 33 ]. Children diagnosed with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, a new diagnosis referring persistent irritability and frequent episodes of extreme behaviour, typically develop unipolar depressive or anxiety disorders as they mature into adolescence [ 32 ]. Clinical presentation differs between genders, with female adolescents reporting feelings of sadness, loneliness, irritability, pessimism, self-hatred and eating disorders, while males present with somatic complaints, reduced ability to think or concentrate, lacking decision making skills, restlessness and anhedonia [ 34 , 35 ].

The severity of depressive disorders can be based on symptom count or intensity, and/or level of impairment. Mild depression can be defined as 5 to 6 symptoms that are mild in severity, with mild impairment in functioning. Severe depression exists when a patient experiences all depressive symptoms listed in the DSM-5 or severe impairment in functioning and, also, with at least 5 criteria and a specific suicide plan, clear intent or recent suicide attempt, psychotic symptoms or family history of first-degree relatives with bipolar disorder. Moderate depression falls between these two categories [ 4 ].

Differential diagnosis

Despite its well-defined diagnostic criteria, depression during adolescence can often be misdiagnosed, with the main differential diagnoses being adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. However, it is crucial to establish the correct diagnosis as different psychiatric disorders involve distinct treatment and prognosis.

Adjustment disorder is classified as depressed mood in response to an identifiable psychosocial stressor. It arises within 3 months of the onset of a stressor and persists up to 6 months after stressor resolution. It is characterized by low mood, tearfulness, or hopelessness associated with a significant distress that exceeds what would be expected given the nature of the stressor, or impaired social or occupational functioning. On the other hand, dysthymic disorder is a pattern of chronic symptoms of depression that are present for most of the time on most days with a minimum duration of 1 year for children and adolescents [ 32 ].

Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are much less common in adolescents compared to depression disorder. However, they have different prognosis and require different treatments. Consequently, when establishing the diagnosis of depressive disorder in adolescence, it is important to bear in mind that the first symptomatic episode may also represent the beginning of a bipolar disorder [ 36 , 37 ].

Management and treatment

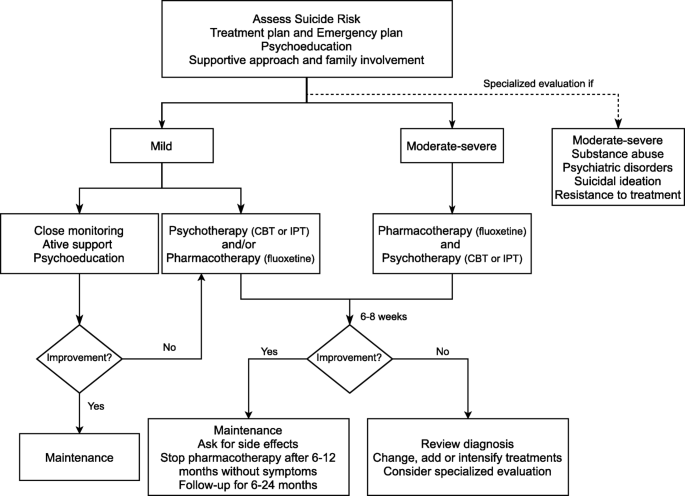

The treatment of depression in adolescence can include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy or both [ 38 ]. Treatment should be selected based on the severity of the condition, the preference of the patient/family, associated risk factors, family support and the availability of each therapy [ 39 , 40 ]. On first approach, it is essential to comprehensively explain the therapeutic strategy and involve both patients and family members to assure close follow-up of progress, treatment adjustment according to symptoms and prevention of relapse [ 41 ]. Adolescents with moderate to severe depression, substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, suicidal ideation or resistance to treatment should be referred for specialized evaluation [ 42 ].

Treatment may be divided into three phases: acute (obtain response and remission), continuation (consolidate the response) and maintenance (avoid recurrences) [ 39 ]. Each of them must include psychoeducation, supportive approach and family involvement [ 39 , 40 ].

In mild depression, psychotherapy may be the first option, complemented with pharmacotherapy if there is no response [ 42 , 43 ]. The AAP recommends starting with active support, symptom monitoring and close follow-up for 6–8 weeks [ 44 ]. These measures are also useful when patients refuse more interventional treatments. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has a slightly stricter approach, in which it recommends psychotherapy after absence of improvement after 2 weeks of watchful waiting [ 45 ]. In adolescents with moderate to severe depression, treatment is based on combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy [ 42 , 43 ]. NICE recommends psychotherapy for the minimum of 3 months, followed by fluoxetine if necessary. AAP has a similar approach [ 44 , 45 ]. Other strategies such as physical exercise, sleep hygiene and adequate nutrition have been referred as treatment adjuvants [ 44 , 46 , 47 ].

Both NICE and AAP recommend treatment for at least 6 months after remission of symptoms to consolidate the response and prevent relapse (continuation phase). In addition, both organizations also recommend maintaining follow-up during 1 year or, in cases of recurrent depression, 2 years [ 44 , 45 ].

Psychotherapy

In this area, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) have shown effectiveness [ 40 , 48 ].

CBT is a brief psychotherapy, carried out individually or in groups, based on the relationship between thoughts, feelings and behaviours [ 40 ]. CBT focuses on cognitive distortions associated with depressive mood and the development of behavioural activation techniques, coping strategies and problem solving [ 42 ]. When used in acute depression, it has been shown to have a moderate effect [ 40 ]. CBT seems to be useful in preventing relapses and suicidal ideation, in the treatment of resistant depression and in adolescents with long-term physical conditions [ 49 , 50 , 51 ]. Moreover, the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, in particular fluoxetine, has shown promising results [ 52 ]. Within the different psychotherapy approaches, behavioural activation, challenging thoughts and involvement of caregivers have a higher success rate [ 53 ].

IPT assumes depression association with disruptive relationships, based on the negative impact of symptoms on interpersonal relationships and vice-versa [ 40 ]. This approach may be useful especially when there is a well-established relational factor as the cause of the depressive condition [ 54 ]. Most studies have compared only IPT with placebo groups or with other psychotherapy, showing favourable results for IPT [ 48 , 55 ].

Psychotherapy should be considered first line of treatment in adolescents afraid of or with contraindications for medication, with identified stress factors or those with poor response to other approaches [ 56 ]. There are no contraindications to psychotherapy, though it has a limited effect in cases of cognitive delay [ 40 ].

Pharmacotherapy

Even though psychotherapy is an important component, pharmacotherapy can be used as an addition. When psychotherapy is not available or cannot be applied, pharmacotherapy can be an alternative [ 39 , 41 ].

Fluoxetine is widely regarded as the first-line drug for this age group given its efficacy [ 2 , 38 , 57 , 58 , 59 ]. Besides fluoxetine, escitalopram has also shown to be particularly effective, especially for ages between 12 and 17 years [ 38 , 60 , 61 , 62 ]. The main side effects of selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs) include abdominal pain, agitation, jitteriness, restlessness, diarrhoea, headache, nausea and changes in sleep patterns. However, these effects are dose dependent and tend to decrease over time [ 39 ].

Given the efficacy of fluoxetine and escitalopram, many studies have focused on other SSRIs, such as sertraline, citalopram, paroxetine and fluvoxamine. Citalopram must be carefully evaluated as side effects include prolongation of the QT interval, which can lead to arrhythmia [ 63 , 64 ]. Paroxetine and fluvoxamine are not commonly used due to a lack of efficacy in this age group [ 65 , 66 ]. Regarding serotonin noradrenaline receptor inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine appears to have a similar efficacy to SSRIs in resistant depression and no significant differences in adverse effects [ 49 ]. However, because hypertension is a possible side effect, this parameter must be periodically evaluated [ 41 , 64 ]. In Table 1 , the main drugs used in the treatment of depression in adolescents are displayed.

Bupropion and duloxetine have also been studied as alternatives but the evidence of its use in adolescents is limited. Bupropion can be useful in the treatment of overweight patients or those who intend to quit smoking. The main side effects are insomnia, agitation and seizures [ 41 ]. Bupropion is contraindicated in patients suffering from eating disorders. Duloxetine can be used for comorbid depression and pain in adolescents [ 67 ].

Tricyclic antidepressants do not have any demonstrated benefit in the treatment of depression in adolescents [ 42 , 68 , 69 ]. This drug class has significant side effects such as dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, tremors and vertigo and can increase PR interval and QRS duration. Moreover, it is highly lethal in overdose [ 69 ].

At the time of writing, only fluoxetine (ages 8 years and older) and escitalopram (ages 12 years and older) are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents [ 70 , 71 ].

Several studies suggest an association between antidepressants and increased suicidal risk [ 18 , 58 ]. However, the risks and benefits of this strategy should be evaluated. Adolescents should be closely monitored, and, if suicidal thoughts arise during treatment, parents should seek care as soon as possible, to adjust dosage, change antidepressant or discontinue it [ 42 ].

Finally, the treatment strategies proposed in this age group are illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Algorithm for the management and treatment of depression in adolescents

Prevention is crucial to depression management, consequence of the impact on the population and inequal quality health care access [ 72 ]. In addition, it prevents the onset of other possible comorbidities, as well as reduces the impact on the patient and their families [ 73 , 74 , 75 ].

It is important to understand which different risk factors and protective factors intervene in the development of the disease. The risk factors can be divided into specific and non-specific for depression. Regarding the specific ones, parent depression history increases the risk between 2 and 4 times [ 76 ]. Among the non-specific, poverty, domestic violence and child abuse also increase the risk. On the other hand, protective factors are good family support, emotional skills or coping ability [ 77 ].

Depression prevention can be divided into 3 types: universal, selective and indicated. Universal interventions target the adolescent population group in general. Selective interventions target adolescents who are at risk for developing depression. Finally, indicated interventions target adolescents with subclinical symptoms of depression [ 78 ].

With regard to universal interventions, the efficacy of prevention programs through therapy for problem solving and overcoming traumatic situations has been demonstrated in multiple studies [ 79 , 80 ]. Although it has been shown that adolescents under these programs experience decreased depressive symptoms, the long-term usefulness of these programs was not unanimous. The inclusion of parents to these programs provided no additional advantage [ 81 ]. Furthermore, no significant difference between adolescents who received an intervention program and those who did not was found, although improvements in school environment were reported [ 82 ].

Concerning selective interventions, interpersonal communication skills and optimistic thinking programs have shown to be effective in decreasing anxiety and depression [ 83 ]. Contrary to universal interventions, the inclusion of parents in programs was demonstrated as beneficial [ 83 , 84 , 85 ]. However, it had no benefit to adolescents, but improved the parents’ perception of children’s behaviour [ 86 ].