Conducting Archival Research

Main navigation.

A guide, featuring the Hoover Institution Library & Archives

This is an open invitation to an intellectual feast on the Stanford campus. The Hoover Institution Library & Archives Reading Room offers open access to a vast array of original sources on world history from 1900 to the present. Unlike published sources in books and newspapers, most of these archival materials are one of a kind and are only available at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives.

The archives are a local campus treasure that you can use to your advantage. For students on campus, access is especially easy. The Hoover Library & Archives staff is on hand to help facilitate use and coordinate with students and faculty to ensure a successful research project.

Typically scholars come to the reading room to see the original documents. Some are handwritten diaries by actors on the historical stage. Other materials include typed correspondence from military and diplomatic leaders. Some collections encompass visual materials, such as posters, photographs, or artifacts that serve as evidence of material culture at a turning point in history. With an estimated 64,000,000 items, only a fraction have been scanned or microfilmed.

What Are Archives?

Archives in the strict, narrow sense are the documents generated by an official government or organization in the course of its duties. So diplomatic dispatches issued by an Embassy are considered archives and the baptismal records accumulated by a church.

In American usage, the term “archives” expands to an umbrella concept for all primary documentation, including personal papers (such as correspondence, diaries, and manuscript writings). It is also used for noncommercial photographic evidence, noncommercial videos, and home movies. Also included in the general concept of archives are ephemeral materials such as posters for an event (e.g. an election). The initial intent for these materials is that they will be discarded after the date of their original use passes.

These materials are generated with one specific purpose in mind (for example, sending orders to an army or enrolling a child in a religious congregation). Then later the documents are preserved and used for a secondary purpose: writing history. Archives are documents that are no longer needed for their original purpose, yet have significant informational and evidential value for the purpose of writing history.

How Do You Start Researching the Hoover Institution Library & Archives?

The brief descriptions of key Hoover Institution Library & Archives collections on this website have been selected with PWR research projects in mind. They will give you a good start on researching some of the wonderful primary sources available to you at Stanford. Much more than what is described here exists in each collection. However, you should be able to get a good idea of possible research projects from these descriptions.

Browse Through This Web Page For Ideas Using A Few Selected Collections

Acquaint yourself with some possibilities for research. Identify a range of historical research topics, working with your instructor to determine suitable topics to research. For topics related to modern history or politics, it is likely that the Hoover Institution Library & Archives have resources for you. Some sample past student research papers covered a wide range of topics. The following themes are just a few of the ones students have researched:

- German and American propaganda

- Women in World War II

- Psychological warfare

- Visual propaganda

- The German atom bomb program

- AIDS posters in Africa

- American dealings in the black market in Germany after World War II

- Relief efforts by UNRRA

- The life of Sydney Riley, Ace of Spies

Check the Web

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives website provides general background, policies and procedures surrounding how to reserve a seat in the reading room, and updates on new acquisitions, at hoover.org/library-archives .

Be sure to read this short guide explaining how to use the search tool .

Find and Access Your Archives of Interest

Begin your preliminary search and write down whatever collections you think might be interesting to pursue. If questions come up, contact research services staff by emailing [email protected] or calling 650-723-3563.

When you have successfully identified the collections relevant to your research, it is time to reserve a seat in the Library & Archives reading room, open Monday - Friday 8:30 am to 4:30 pm. The reading room page on the website contains detailed information on how to reserve a seat, request material through Aeon , and prepare for your visit: https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/reading-room . Please feel free to ask for help with the staff once you have completed your search.

How to Search

Searchworks.

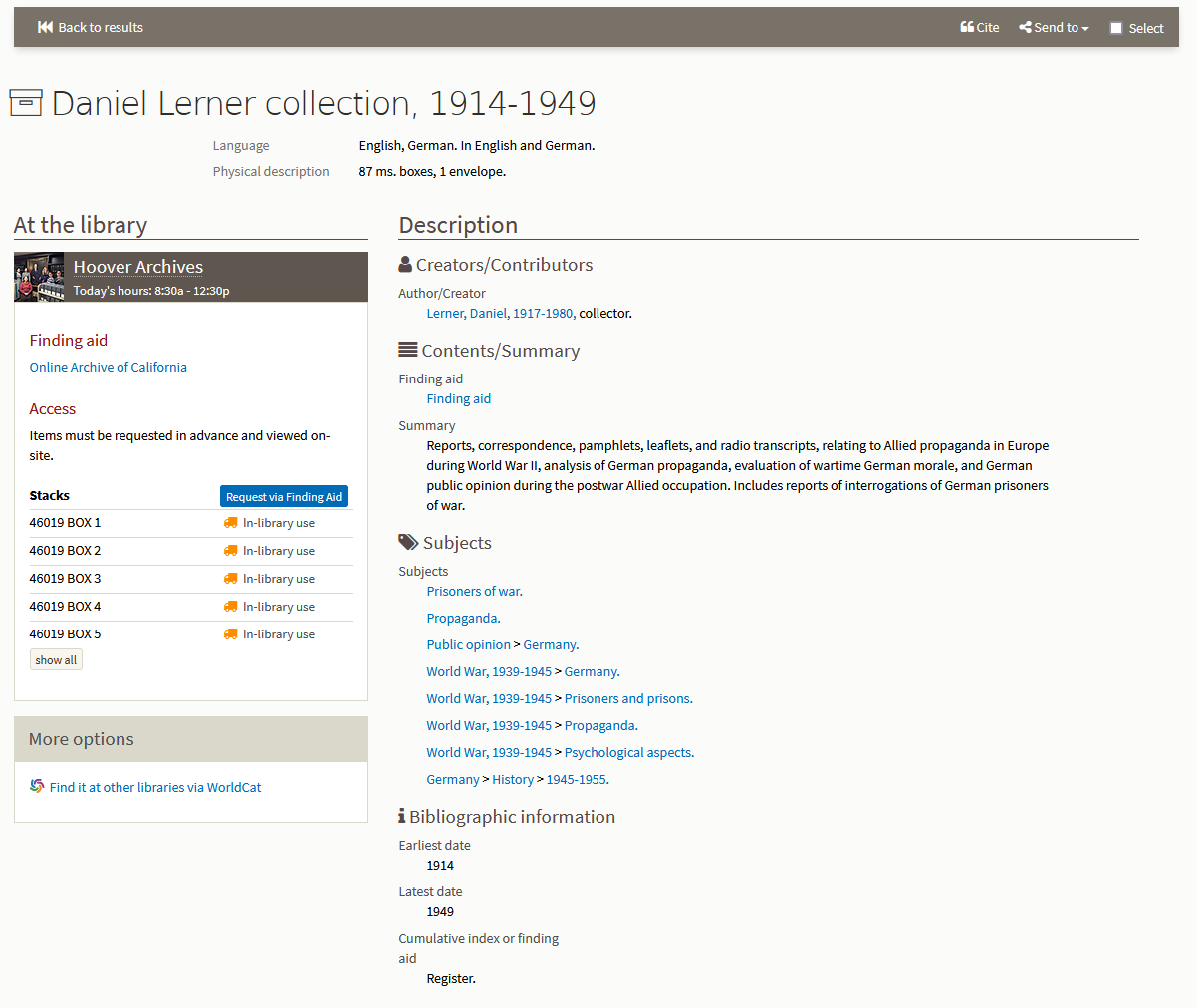

Most of the Hoover Institution’s library and all archival materials are listed in Stanford’s online catalog SearchWorks , available for browsing. To narrow your search, try clicking on “Hoover Institution Archives” in the library box of the SearchWorks interface. Then enter search terms. If you typed in “World War II propaganda” and hit the key to search all categories, you would find a list of 70 collections in the Hoover Archives including the papers of Daniel Lerner, who collected World War II propaganda and analyzed it for the Office of War Information. We'll go through this one together.

The collection name is your starting point. If you click the name, you will find the following general, collection-level description :

Online Archive of California

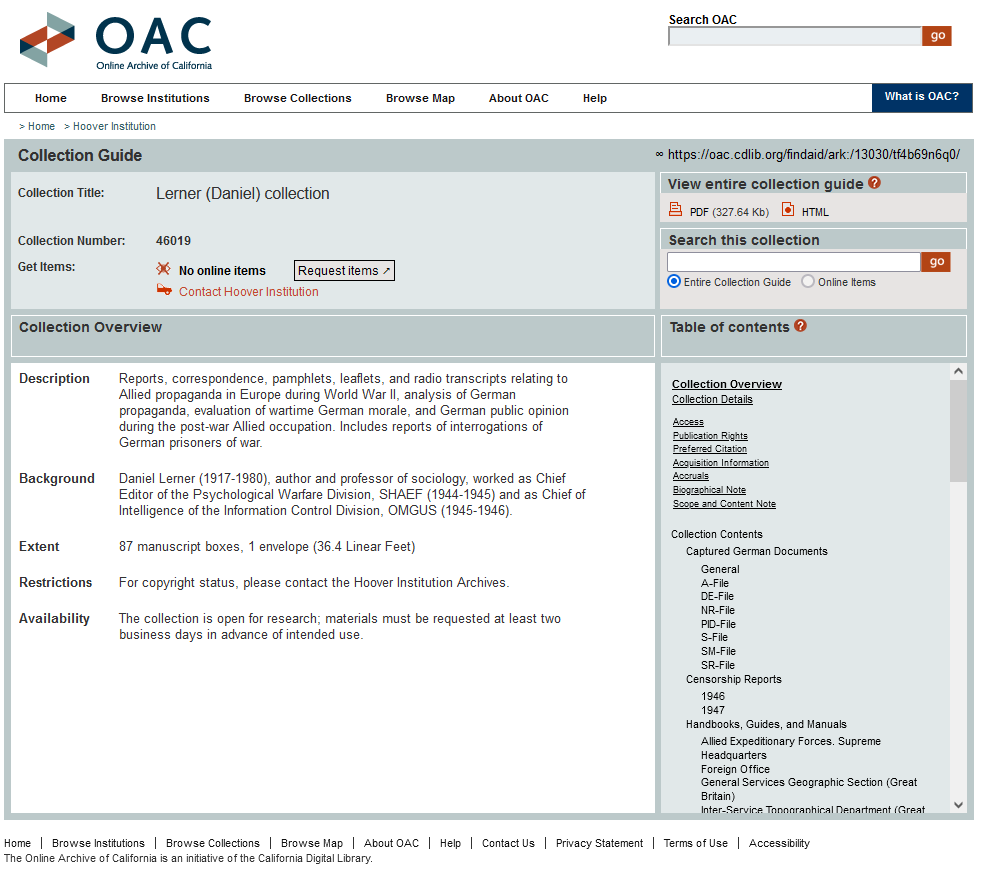

The Online Archive of California (OAC) provides access to descriptions of primary source collections held by the Hoover Institution Archives, as well as more than 200 archival repositories across the state of California. Collections are listed in alphabetical order and have their own collection guide (as known as a finding aid) that includes biographical information about the creator, the scope and contents of the collection, and inventories and register descriptions of the material.

On the OAC website, conduct your search within the Hoover Institution by going to “Find a collection at this institution” in the left sidebar, or browse by alphanumeric order by clicking the appropriate number or letter. Once you have found the name of the desired collection, clicking on it takes you to the collection’s page. There, you have the option to view the entire collection guide in PDF or HTML format (links located in the upper right hand corner of the page). You can also use the search function to search the collection guide. To request items, through Aeon, click on the field on the top of the page.

For example, take the Daniel Lerner collection which has 87 boxes, this Finding Aid can help you pinpoint what material at the box-level is relevant to your research.

The opening page will be as shown below.

Hoover Institution Digital Collections

Hoover Institution Library & Archives collections that have been digitized prior to 2021 can be found on our Digital Collections portal. Digitized items include posters, photographs, manuscripts, moving images, sound recordings, and other historical materials.

Searches should be in English, with a few exceptions:

- many non-English proper names have not been translated into English;

- the records of the Zhongguo guo min dang [Kuomintang] are described in traditional Chinese; and

- the Ėduard Amvrosievich Shevardnadze radio interview transcripts are described in Cyrillic.

The keyword search covers title, creator/contributor, description, subject, country of origin, object number, and object name. It also searches the full text of most PDF files ("document full-text").

Use quotation marks (" ") to search for an exact phrase and an asterisk (*) to search for a truncated term. For example, “Cold War” and stat* (for state, states, statutes, statistics, stats, and more).

In the search results, the search term is usually highlighted in context, with one exception: if a search term is found in the document’s full text. When a PDF file is retrieved in a search result and no search term is highlighted, the term is somewhere within the PDF file. After opening the PDF file, you can search within it for the term using keyboard shortcuts Control+F for PCs or Command+F for Macs

Additional search help is available in the Advanced Search .

How Do You Use the Originals?

Once you have identified a promising collection, you will need to reserve a seat in the reading room and request material (in priority order) through the archives’ registration system, Aeon . Reservations must be made 7 calendar days in advance, as half of the Library & Archives material (over 90,000 items) are stored off-site. Once you have submitted your reservation and selected material through Aeon, you will receive an email confirmation from staff.

When you arrive at the reading room, the reference archivist will explain how to safely handle fragile documents. If you are using photographs, you will be given a clean pair of nitrile gloves to wear to protect the emulsion from fingerprints. After the first visit, the logic behind these procedures will all make sense and seem second nature.

When you look at the documents, you need to bring your own knowledge of the context to bear. Background reading in published sources is absolutely essential to understand just what you are looking at. Then you will need to ask a lot of questions while you go through the materials, such as:

- Are the files complete or fragmentary?

- Are they well organized or random in order?

- When were they written and by whom?

- Is the author knowledgeable or clueless? (All archives have some of both!)

- Is the document authentic or the copy of another document? (You can tell this by examining the paper as well as the ink and by reading the document itself.)

- Is it a forgery, and if so, what was the purpose of the forgery?

- Is there an agenda in the writings?

With visual materials such as political posters or photographs, “reading” the pictures can take as long, or longer, than reading actual text. There are often ambiguities in archival documents. Working assumptions need frequent revising.

For more information on Hoover Library & Archives conditions of use, visit https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/reading-room/conditions-use .

How do you get from the primary source to the research paper?

For your research, you will need to use a combination of primary sources, like those found at Hoover, and secondary sources, published scholarly works or articles on your topic. A comparison of primary sources with published secondary sources on the same topic will often reveal a fresh perspective on historical events, add richness of detail to known events, correct faulty evaluations, or refine the chronology of history, provide a new voice from an eye witness to history. Exploring archives leads to such discoveries that form the basis of research that adds to our knowledge. One document alone can be the basis of an analysis. One poster can be used to illustrate a point. More frequently, the series of files provides a sense of “real time” as events unfold. Secondary sources show how events lead to a result, and have an air of inevitability about them. Primary sources show imperfect people struggling with the blur of conflicting and confusing forces, the “fog of war.” The authors of letters do not yet know what the outcome will be; their motives are often mixed and unclear even to themselves.

Be sure to cite the sources you use, not only to avoid plagiarism but to lead other researchers to your sources accurately. The convention is to go from general to specific in your footnotes: Name of the archives, name of the collection, box number and folder title or number. For example: “Hoover Institution Archives, Daniel Lerner Collection, Box 52, Folder 1.” It will then be up to your readers to find the actual documents in question once you have given them the folder information.

When Your Research Paper is Complete

Archival research is steeped in traditions and etiquette. Researchers, as a courtesy, are expected to inform the archives of publications citing their materials. Many European archives have entire libraries of publications based on their sources. The Hoover Institution Library & Archives appreciates receiving copies of such work or at least citations to publications and titles of research papers submitted to Stanford classes. Your instructor may ask you for another copy of your final paper so that the Archives can have a record of the work student researchers have done.

But above all, have fun and enjoy the wonderful resources available at Hoover Institution Library & Archives!

Research Methodology: Archival Research

- Overview of Research Methodology

- General Encyclopedias on Research Methodology

- General Handbooks on Research Methodology

- Focus Groups

- Case Studies

- Cost Benefit Analysis

- Participatory Action Research

- Archival Research

- Data Analysis

About Archival Research

Archival Research is the investigation of hard data from files that organizations or companies have. US Census data are archival data. Telephone bills that are in the computers of the telephone company are another example. Fire departments keep records of fires, chemical spills, accidents and so forth, all of which constitute archived data. Most IQPs use archived data. Indeed, many IQPs require the use of several kinds of archived data, some of which get transformed into different forms so that they can be used together to help the authors defend an argument.

- A Survival Guide to Archival Research From the America Historical Association by Heck, Barbara; Preston, Elizabeth; and Svec, Bill

- Introduction to Historical Method Five part series serves as an Introduction to the Historical Method by Comtois, Marc

Method Demonstrated by IQPs

- Feeding the World: The Impact of Theo Brown and John Deere Blackwell-Tompkins, Michael;Danley, Steven; Egan, Christopher; Saffron, Jacob; Silsby, Derek

- Noise Data Farming for the City of Boston Finzel, Brandon R.; O'Toole, Shannon Elizabeth; Perron, Justin M.; Russell, Jacob E.

Books on Archival Research

- << Previous: Participatory Action Research

- Next: Data Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Sep 12, 2024 6:11 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wpi.edu/researchmethod

How can we help?

- [email protected]

- Consultation

- 508-831-5410

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Review of The Archive Project: Archival Research in the Social Sciences

2020, Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies (LLIDS)

The relatively recent archival turn-the necessity to enter library archives for research-has resulted in an increased engagement with previously undiscov-ered materials throughout numerous fields. Emphasizing this turn, the four authors of The Archive Project lay out various intersecting theoretical and practical issues-specifically looking at epistemological, ontological, and methodological problems-to provide fellow researchers with a sense of logical and supportive approaches for a broad range of considerations concerning research in archives. The result of these scholars' efforts is a fairly cohesive journey through the field of archival research over the last few decades. With the rapidly changing methods of digitizing archival materials, various debates about practical aspects of gathering, processing, storing , and incorporating material are examined across the six chapters of this collection. The first and the last chapter are written by the group, while the middle four chapters allow each author to present their views by discussing specific collections with which they have worked. The organizational structures of the chapters are focused around women's studies and include archive collections from around the world. The Archives Project arrives during a period of intensifying interest in the promotion and necessity for researchers to uncover new Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies (LLIDS)

Related Papers

Collections

Bertram Lyons

International Conference on Knowledge and Politics in Gender and Women's Studies

A new subject has entered women studies in Turkey: Women-centered archives and their historical process. The acquisition of women's and women's organization's archives/papers/records and their preservation in an archive center is a new field of interest in Turkey. In order to understand the history of these collections in various countries, we must not forget that the decisive factor of the existence of these collections is the feminist movement. As so many fields have been closed to women for a long time, women and the women's movement have established and developed their own institutions. In the early 20 th century, the documents generated by the women's movement were preserved in newly founded archives centers. These collections were documents issued by the women's movement either during their struggle, their mass actions or activities. Usually these archives centers were founded by feminist pioneers through the donation of their own private papers. These centers still represent an answer to the exclusion/omission of women in the archival field and they represent the memory of women and women's movements; they also create an awareness regarding the "invisibility" of women in history. A century ago in parallel with the struggle of women for freedom and equality a new consciousness began to blossom: Women and the women's movement realized that if they wanted to transmit to future generations, documents and archives, they had to solve the acquisition and preservation process themselves. Here at this point, women started to set up archive centers which grow in parallel with the development of the women's consciousness. In this paper, I will try to explain the establishment process of women's archives, the problems they had to face, the reasons of the loss of memory/documents and the work done in order to solve them. I will try to also assess the level of development of this new field in Turkey.

Wendy Fasko

Tom Nesmith

Library Trends

Tanya Zanish-Belcher

In 2000, we coauthored "A Room of One's Own: Women's Archives in the Year 2000," an article focused on the growing number of women's archives in the United States and the impetus for their creation (Mason & Zanish-Belcher, 1999). We argued that women's archives were ...

Archival Science

Patricia Whatley , Caroline Brown

Sarah Tyacke

Sarah Lubelski

Proposed in 1935 by feminist pacifist Rosika Schwimmer and dissolved only five years later, the World Center for Women’s Archives (WCWA) is now remembered as a mostly failed experiment. Current scholarship suggests that the organization’s sole long-term contribution was the preservation of women’s historical materials that would form the basis of more significant women’s collections. However, a more in-depth analysis reveals that, beyond acting as a repository, the WCWA was an innovator in the fields of women’s history and archives. The organization’s understanding of the power of the archive, including the role of the archive in shaping historical memory and the politics of exclusion that governed the building of an archival collection, had a profound influence on the Archives’ ideologies. In the quest to recover women’s history, the WCWA emerged as a counter-archive, employing alternative approaches to historical documentation and knowledge production in order to represent the fem...

https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/issue/view/429

ABSTRACT This is a reflective essay on some of the cultural, literary criticism, historical , and postmodern implications for records management and archiving, archives, and archivists from a point of view situated in the United Kingdom. It is based on observing the changes, over the past ten years, in the position of archives in various countries' perceptions. The author maintains that archivists have the critical role of producing an archiving resolution of the tensions in society at any one time between what should be kept and destroyed, and what should be open and closed-both for the present and, more importantly, for future generations. Archivists need to make the manner of the archival resolution clear and understand the inherent biases in the processes necessary to achieve that resolution. The subject of archives is, on the face of it, dry and dusty, but nevertheless fascinating for all sorts of reasons to many millions of people across the world. Moreover, in its formal, organizational, and utilitarian guise as "Arch-ives," it is increasingly emerging from the "basement to the boardroom" in governments and organizations and becoming a cultural phenomenon at the same *

Isabel Carrera Suárez

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Feminist Review

Nydia A. Swaby

Marlene Manoff

Marika Cifor

Kate Eichhorn

meera velayudhan

Qualitative Sociology

A.K.M. Skarpelis

Public Knowledge

Jared Davidson

Maria Tamboukou

LSE Field Research Methods Lab

Sin Yee Koh

Markus Friedrich

Mary Grace Golfo

Victoria Lemieux

History Workshop Journal

Richard Taws

Feminist Media Histories

victoria duckett , Jill Matthews

Miranda Johnson

Jason Lustig

Harriet Edquist

K.F. Latham

The American Archivist

Steven Lubar

Pierangelo Blandino

Anne J Gilliland

Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature

Laura Engel

Dag Petersson

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Citing Archival Resources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Once you have determined which materials are relevant to your research, you will need to know how to reference them properly in your paper or project. Citation is one important challenge you must face when working with archives. Because archivists strive to preserve the unique order of collections when they are donated, universal guidelines for citing archival sources have not been established. However, we suggest the following methods based on best scholarly practices.

How to Cite Archival Materials

You have two viable options for citing archival sources.

- Check the archives website or contact them for a preferred citation.

- Use the adapted MLA citation we propose below.

If you choose Option 1, first check the website of the library or archival system, which may contain guidelines, or LibGuides, for referencing their artifacts. Here's an example of a Purdue University LibGuide .

You may also call or email the archival staff to obtain or ask questions about preferred citation practices.

If you choose Option 2, you will need to adapt the MLA citation format to meet your needs. To start, refer to the MLA citation practices most relevant to the particular genre of your materials. For example, the most recent MLA handbook will contain citation guidelines for comic books, film strips, commercials, photographs, etc. Next, include as much detail as possible to help a fellow researcher locate your artifact in a given archive. Depending on the system in place, you should refer to box numbers, folders, collections, archives name, institutional affiliation and location. Since archives are dynamic in the sense that collections may be sold, donated to another archives, reorganized and in extreme cases damaged or lost, you should also include the date accessed.

The following example is based on a combination of MLA citation practices and the Purdue LibGuide:

Genre-appropriate MLA Citation. Box number, Folder number. Unique identifier and collection name. Archives name, Institutional affiliation, Location. Date accessed.

Summers, Clara. Letter to Steven Summers. 29 June 1942. Box 1, Folder 1. MSP 94 Steven and Clara Summers papers. Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University Libraries, West Lafayette, IN. 20 May 2013.

While these two citation options are recommended, you should consult with your publisher or instructor to determine what information they value most in your citation.

A Guide to Archival Research

- How to read a finding aid

- Evaluating primary sources

- The Archival Research Process Part 1: Before you visit the archives

- The Archival Research Process Part 2: Visiting the Archives

- The Archival Research Process Part 3: Organizing and Citing Archival Material

- Accessing Archives Online

Reading a photograph

- What can you learn from this photograph?

- What contextual information would help you better understand this photograph?

Introduction

Archival research can be overwhelming. Your research may focus on a single textual document, or it might require you to look at tens of boxes (if not more)! Whether your research is a long-term project (like a thesis or book), or a short-term project (like a paper or blog post), knowing the basics of how to do archival research before you start can save you time and energy later on.

Like any project, the key to success is planning! By following this step-by-step guide, you will learn how to best manage your visit to the archives.

The Archival Research Process

- 1. Narrow your topic

- 2. Develop your research question

- 3. Think about the kinds of sources you hope to find

- 4. Search for and identify archives

- 5. Read archival finding aids and collection guides

- 6. Contact the archives

1.1. Select a broad topic.

The first step for any research project is to select a topic. You may not know exactly what your final project will be when you begin (that is okay!), but it is a good idea to start with a topic which interests you. Ask yourself questions related to your topic:

- What interests you about the topic?

- What would you like to learn about it?

- What do you already know about the topic? What aspects of it would you like to know more about?

1.2. Narrow your topic by doing background reading.

Background reading means looking up information about your topic from general sources before you begin your research as a way to learn more about your topic in broad strokes. These are sources which will give you a general overview of your topic and therefore will not be included in your bibliography or works cited.

Reference sources such as these can offer you more general information about a topic which will help you narrow the focus of your research. With these types of reference sources you may discover sub-topics within your research interest, major debates in the field about your topic, and key authors or persons related to your topic.

Learning as much as you can about a topic before you begin your archival research can be a very useful way to make the most of your time in the archives. Background reading will help you:

- become familiar with the basic information about the topic, including its concepts, controversies, and historical context;

- learn the names of people related to the topic;

- decode some of the jargon related to the topic;

- possibly find sources by following the background sources' footnotes or bibliography.

Being familiar with aspects of the topic, such as important dates or people, will save you time and energy when you encounter archival material related to it. By knowing these things before you encounter them in the archives, you will already have the crucial contextual information needed to make sense of the document that you are looking at.

For example, if you are reading a diary entry which includes a reference to an event which took place in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, it would be useful if you were already familiar with what that meant!

2.1. Develop a research question by exploring questions related to your topic.

- Ask yourself open-ended questions about your topic. The "how" and "why".

- Consider the "so what?" What is the significance of your topic?

- Get creative. What would you like to learn?

2.2. Determine a question that you hope to answer through your research.

- Is your question clear?

- Is your question specific? (Can it be answered by your project?)

Hypothesize where your research might lead.

- Is your question answerable?

- Are the resources which might answer your question available?

Find a topic specific enough that you will be able to master it in the time that you have.

- Would an exploration of your topic be appropriate for the required length your project? Would it take an entire book to adequately answer?

- If you have a deadline for your project, do you think you can learn what you need to know and completing your project within that deadline.

Be prepared to revisit your research question throughout the process.

As you will find, the archival research process can be challenging. You may often discover that the information that you have is not the information that you originally wanted! The most important part of good research is to follow what the evidence says, not what you want it to say.

For more help on forming research questions, check out these guides:

3.1 Think about what sorts of archival sources might answer your research question or that might be related to your narrow topic.

- Would you find relevant information in someone's correspondence?

- In someone’s diary?

- In a historical newspaper?

Unfortunately, not every document that you can imagine actually exists -- it may never have been written, or it may have been lost or destroyed before it could be preserved in an archival repository. For example, not everyone keeps a diary. Of those that are kept, very few survive. Of these, even fewer end up in archival repositories!

Don't let this discourage you! It just means you need to think about what kinds of documents might help with your research rather than thinking a single source will answer your question.

3.2 When you have an idea of what kind of documents you are interested in finding, ask yourself:

- Who would have created the documents that might inform my question, and for what purpose?

- In what context might these documents have originated? Am I looking for official documents, like government records, or for the personal documents of ordinary people?

- Where might these documents be now? Are there repositories which specialize in the types of documents I might need to access?

Here are two examples of questions which might lead to archival research:

| Research question #1

| Research question #2 ? |

| What type of document might help answer this question?

There are several potential sources for this question but the best might be soldiers' letters from the front. The William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University has a collection of soldiers letters, which are described The letters of Gordon William Parkinson (1898-1918), a Canadian soldier who fought in World War I, have been digitized by McMaster and are available | What type of document might help answer this question?

There are several potential sources for this question. Unfortunately, some of these sources, like "Viola Desmond's diary," do not exist! The document that might best answer the research question is the court documents from the trial. By law, court documents are archived in government archives. Because the trial occurred in Nova Scotia, the documents are held by the Nova Scotia Archives. They have been digitized and can be found |

What is evidence?

No matter what your field is, academic research consists of making a claim and providing evidence which supports that claim. Researchers in different fields might have different words for this, such as 'argument' in place of 'claim' and 'data' in place of 'evidence'. The strength of your argument or claim rests on the strength of your evidence.

The critical question about your claim is: can you prove it? How do you know if you have collected enough sources?

When you have proven your claim.

To be acceptable as "proof," make sure that your information is verifiable and collaborated by other information. Sometimes record creators make mistakes! For example, a letter dated after the author's death is not evidence that their faked his death -- it's evidence that they were careless when writing dates!

4.1 Search for archives that hold material that is relevant to your research.

Archives have collecting mandates which govern what materials they are likely to acquire. As you explore archival websites and databases, make sure to look out for descriptions of their collecting policies and overviews of their collecting strengths. For example, the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections has a collection focus on Business, Commerce, Canadian Journalism, Canadian Publishing, the World Wars, Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Labour History, Literature and Writing, Music, Peace and Pacifism, and Politics and Radicalism.

Consider talking about your research with your instructor or an archivist, who might be able to make recommendations for where to look.

Additionally, there are online search tools for locating archival material. These may be specific to a repository, or they may be portals which index the holdings of multiple repositories. In many cases, individual repositories may have more accurate or up-to-date records than those found through search portals. Examples of search tools include:

AtoM at McMaster

AtoM (Access to Memory) is the online database of holdings located at McMaster University's William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections.

ARCHEION: Ontario's Archival Information Network

ARCHEION is the online catalogue of descriptions of records located in archives across Ontario.

Archives Canada

Archives Canada is a portal for connecting users to archives across Canada. Includes links to provincial and territorial databases, online exhibits and digital holdings.

Archive Grid

Archives Grid is a searchable database containing roughly 5 million descriptions of archival collections in 1,000 libraries, museums, historical societies and manuscript repositories around the world.

4.2 Keep in mind your limitations as a researcher.

You may discover the perfect archival material for your project held by an archives in another part of the country or maybe another part of the world! If you are limited by travel and time necessary to consult those documents, you may need to rethink your project based on what archives are within your geographic area.

- You may also have the option of looking at archival material that is available digitally through the website of the archives of your choice. Check out the Accessing Archives Online section of this guide to learn more about digital archival research.

- Another option is to investigate if the archives of your choice is able to make digital copies of archival material. Learn more about this process on the 'Contact the Archives' (Step #6) page of this guide.

5.1 Once you have found the archives you would like to visit, look at their finding aids before contacting them.

Archives will often make their "finding aids" available online. Reminder: a finding aid is like a roadmap to the archival material and will be the essential tool to help you navigate the archives. For more information, read the next page of this guide, How to Read a Finding Aid .

If the finding aid isn't available online, contact the archives and request more information about the material.

5.2 Make a list of the boxes and files that you are interested in looking at.

As you read the finding aid, you will hopefully find a number of boxes and files which look like they will be useful to your research. Keep a detailed list of what you are interested in.

It is possible that you will not have enough time to read everything that you thought might be of interest in the archives. When you have completed your list, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much time will I need to go through this material? ( Be careful: archival research always takes longer than you think! )

- How many visits to the archives will it take me to look at all of the material?

- Which of these boxes will be the most likely to have the information that I am looking for? ( Hint : Look at these ones first!)

5.3 Review your list and contact the archives!

Once you have determined what material you would like to look at, you are ready to contact the archives.

6.1 Contacting the archives and scheduling a visit.

Archives will expect that in your email you introduce yourself, and list the specific boxes that you wish to access. Most archives will expect you to email them ahead of time (3-4 days in advance of your visit) when requesting material. If you are considering traveling for a visit to the archives, be in contact with the archives as soon as possible in order to make sure the material will be available for your visit. (Make sure the material is ready for you before you book a trip!)

It may also be helpful to write a general description of your research interest and your project. The archivist answering your email may have advice about your research, including the suggestion that the material you are requesting will not be as useful as you hope, or they might recommend something you had not thought of. Remember: archivists cannot do your research for you, but they may be able to provide helpful advice for your project.

Things to keep in mind:

- Archival material is not always available on-site. It may take a few days for the archives to get the material prepared for you. That is why it is always a good idea to email a few days in advance of your visit.

- Why might an archives have restrictions? In some cases, archival material contains personal information about the creator or a third-party. By law or by agreement with the donor of the material, this information must be kept confidential until a specific date.

- Archives are typically only open standard business hours (i.e. Monday to Friday, 10:00 am to 5:00 pm). Don't expect to visit after hours or on the weekend.

(6.2 Requesting digital copies)

You may find archival material in an archives that you are unable to visit due to time and budget constraints. Many archives offer digital copying services.

Things to keep in mind when ordering digital copies:

- There will be a fee. Pay attention to the size of the request and consider your budget.

- There may be copyright restrictions. The archives may refuse your copy request if copying violates a copyright or other restriction.

- You will have to sign a copy agreement which states that the copy is being made for your own research and will not be duplicated or transferred to others.

- Digital scans may not be possible in cases where the material is fragile and if the process of scanning will threaten its integrity. The staff will assess the condition of the item prior to scanning.

Digital copies at William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University:

When requesting digital copies of archival material, please fill out the form found at the following link: Copy Request Form.

- << Previous: Evaluating primary sources

- Next: The Archival Research Process Part 2: Visiting the Archives >>

- Last Updated: Jul 26, 2023 2:21 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/guide-to-archival-research

Archival Research

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Connor Brenna 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

5956 Accesses

An archive, in the broadest sense, is any collection of historical materials. Archival research is a primary research methodology in which archival holdings constitute the key source of data. The technique is unique among qualitative research methodologies in that it traditionally requires physical exploration of one or more archives to acquire source material which may not be available anywhere else, although advances in electronic recordkeeping and open access practices are making archival research more accessible. This chapter presents a brief history of archival research, an introduction to its use, and an overview of its strengths and limitations. It also offers a use case to describe how an archival researcher might leverage the exclusive holdings of an archive to answer an interesting and novel research question.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Into the Archives

How Can an Archive Be Characterized?

Archives and the American Historical Profession

Clanchy, M. T. (2012). From memory to written record: England 1066–1307 . Wiley.

Google Scholar

Duffin, J. (2009). Medical miracles: Doctors, saints, and healing in the modern world . Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gilliland, A., & McKemmish, S. (2004). Building an infrastructure for archival research. Archival Science, 4 (3), 149–197.

Article Google Scholar

Giusti, M. (1978). The Vatican secret archives. Archivaria, 7 , 16–27.

L’Eplattenier, B. E. (2009). An argument for archival research methods: Thinking beyond methodology. College English, 72 (1), 67–79.

Scott, J. (2014). A matter of record: Documentary sources in social research . Wiley.

Seale, C. (2004). Researching society and culture . SAGE.

Sinner, A. (2013). Archival research as living inquiry: An alternate approach for research in the histories of teacher education. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 36 (3), 241–251.

Ventresca, M. J., & Mohr, J. W. (2017). Archival research methods. In J. Baum (Ed.), The Blackwell Companion to organizations (pp. 805–828). Wiley.

Chapter Google Scholar

Yale, E. (2015). The history of archives: The state of the discipline. Book History, 18 (1), 332–359.

Additional Readings

Gaillet, L. L., Eidson, D., & Gammill, D. (Eds.). (2016). Landmark Essays on Archival Research . Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Hill, M. R. (1993). Archival strategies and techniques (Vol. 31). Sage Publications.

Moore, N., Salter, A., Stanley, L., & Tamboukou, M. (2016). The archive project: Archival research in the social sciences . Routledge.

Ramsey, A. E., Sharer, W. B., L'Eplattenier, B., & Mastrangelo, L. (Eds.). (2009). Working in the archives: Practical research methods for rhetoric and composition . SIU Press.

Online Resources

What is archival research (3 min): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kzZz3HYlN4Y&ab_channel=TheAudiopedia

Archival research tips (13 min): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nAIRwtb7XsU&ab_channel=BrianSweeney

Sciences of the Archives (16 ½ minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iPSa4Ub8FU8&ab_channel=LatestThinking

Archives have the power to boost marginalized voices (8 ½ minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XsNPlBBi1IE&ab_channel=TEDxTalks

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Connor Brenna

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Connor Brenna .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Janet Mola Okoko

Scott Tunison

Department of Educational Administration, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Keith D. Walker

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Brenna, C. (2023). Archival Research. In: Okoko, J.M., Tunison, S., Walker, K.D. (eds) Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_6

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04396-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04394-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

Library and Information Studies

- Archival Studies

- Articles and Databases

- Reference Sources

What Is Archival Studies?

Top archives and records management journals.

- Informatics

- Library Studies

- Portfolio and Thesis Resources

Archives play a critically important role in many aspects of society. As repositories of a culture's unique documents, records and other texts, archives serve as basic tools for social accountability, the preservation and dissemination of historical memory, and the development of a richer understanding of cultural, social and political forces in an increasingly digital and networked world.

In addition to covering traditional archives and manuscripts theory and practice, this area of specialization addresses the dramatic expansion of the archival field. It charts how accelerating technological developments have changed both the form of the record and methods for its dissemination and preservation. It responds to shifting social and political conditions as well as the increased codification of archival practice through local and international standards development. It actively engages debates about archival theory and societal roles in diverse archival and cultural jurisdictions.

The specialization comprises a range of courses, experiential components, and research opportunities. Courses explore the full spectrum of archival materials (e.g., paper and electronic records, manuscripts, still and moving images, oral history); the theory that underlies recordkeeping, archival policy development and memory-making; and the historical roles that recordkeeping, archives, and documentary evidence play in a pluralized and increasingly global society.

Examples of student emphases within the Archival Studies specialization include:

- Appraisal and collection-building

- Preservation of traditional and digital materials in a range of media

- Development of new methods for providing access based on the needs of diverse and non-traditional constituencies

- Design and development of automated records creation and recordkeeping systems

- Design and development of archival information systems, metadata including, inventories, finding aids and specialized indexes

- Curatorship of both site-specific and virtual exhibits

- Development, evaluation, and advocacy of archival and recordkeeping law and policy

- Scholarly research on comparative archival traditions

- Use of archival content in K-12 education

- Intellectual property management and digital licensing of primary sources

- Archival administration: from staff development to grant writing

- Providing reference and outreach services

- Management of special collections, archives, and manuscript repositories

- Design and supervision of digitization initiatives

- American Archivist

- Archival Issues

- Archival Science

- Archives and Manuscripts

- Archives and Museum Informatics

- Journal of Archival Organization

- Journal of the Society of Archivists (Great Britain)

Records Management

- NARA Bulletin

- Information Management Journal

- << Previous: Books

- Next: Informatics >>

- Last Updated: Jun 28, 2024 3:46 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/information-studies

The National Archives Catalog

Introduction to Archival Materials and Related Elements

Archival materials and related elements, introduction, how the archival materials elements work, archival materials elements, archival creator elements, levels of archival description, digital objects elements, the framework.

These elements are used to describe many different hierarchical levels of archival materials from record groups to items as well as all formats of archival materials from paper to electronic records to artifacts. In addition, there are elements for archival creators and for digital objects.

When describing records, you will associate descriptions of archival materials with their creators to put the archival materials in context. Every series description must be placed in a record group or collection, and must also link to a creator. Creator descriptions can link to multiple record descriptions. Every item or file unit description must link up to a series description. These linkages will allow us to maintain the hierarchy and provenance of records.

When digital objects, such as digital reproductions of photographs, are included, they also are linked to the archival description. One archival item or file unit can have many digital objects. For example, each scanned page of a letter would be a digital object, and each would be attached to the archival description.

The elements used to describe archival materials are divided into three categories:

- the intellectual elements

- the physical occurrence elements

- the media occurrence elements

Intellectual Elements

The intellectual elements describe the content of the archival materials, including the title, arrangement, function and use, scope and content, dates, control numbers, access and use restrictions, and other access points such as geography, language, subject, and record types. According to A Glossary for Archivists, Manuscript Curators, and Records Managers (Society of American Archivists [SAA] Glossary), an access point is "a name, term, phrase, or code that is used to search, identify, or locate a record, file, or document."

Physical Occurrence Elements

The physical occurrence elements describe the physical characteristics for each copy or version of the archival materials, including the amount, containers, location, and reference unit. The physical characteristics also include the purpose behind each copy or version: e.g., is it used for preservation, reproduction, or reference.

Media Occurrence Elements

Within each physical occurrence, the characteristics of the physical media also may be described. If the archival materials consist of a variety of physical media, each medium is described in its own media occurrence. The media occurrence elements include the media type, color, dimensions, piece count, and reproduction count, as well as the format and processes used to make the media itself.

A key concept here is that a particular physical occurrence can have many media occurrences. If a physical occurrence includes multiple media types, or if the media types come in different sizes, exist on more than one base, or were produced by more than one process, etc., then all media occurrence elements must be repeated as a group to capture the different media occurrences. For example, a physical occurrence of a series of records may contain a preservation set of photographs and paper records. The photographs are one media occurrence and the paper records are another. This same series may have a duplicate set of photographs and paper records used for reference -- a second physical occurrence. The photographs and paper records of the second physical occurrence would also have separate media occurrence descriptions.

Separate sets of elements are used to describe archival creators. The records creators can be individuals or organizations (agencies or units within an agency.) The individual creator elements include names, birth and death dates, and biography. The organizational creator elements include names, administrative history, establish and abolish dates, function, and jurisdiction. Each series description will identify a creator or creators of the archival materials and this identification will provide the link to the creator description.

For the elements used to describe organizational creators, the guidance indicates how to form names, write histories, and index them via access points. What is not apparent from the element guidance is that although an organization may undergo a reorganization that results in a name change, it remains essentially the same organization. When this is the case, the Organization Names that represent the organization share an Administrative History Note and are considered "minor" predecessor/successors of each other. However, when a transfer of functions to an entirely new organization occurs, that successor organization will require a new Administrative History Note.

The following general rules will help you decide when Organization Names should be linked to the same history and when a successor should link to a new Administrative History Note. Organization Names will share the same history when:

- An organization's hierarchical placement changes due to a reorganization, but the functions and name remain relatively intact; or,

- An organization's name changes without an accompanying significant adjustment of its functions.

However, when an organization is abolished and its functions are transferred to an existing or new organization, the new Organization Name should not be linked to the existing Administrative History Note and a new note should be written.

Archival records are described at various levels of aggregation:

Record Group/Collection

The highest grouping of archival materials will be a record group or collection. At NARA, both function as a means for facilitating administrative control of holdings.

The SAA Glossary defines a record group as "A body of organizationally related records established on the basis of provenance by an archives for control purposes." NARA has defined a record group as "a major archival unit that comprises the records of a large organization, such as a Government bureau or independent agency."

The SAA Glossary defines a collection as "An artificial accumulation of documents brought together on the basis of some characteristic (e.g. means of acquisition, creator, subject, language, medium, form, name of collector) without regard to the provenance of the documents." The Presidential libraries often organize their archival materials by collections, which primarily fall into three categories: donated historical materials (relating to all Presidencies, Hoover-Bush), Presidential records (applying to Presidencies since Reagan), and Presidential historical materials (Nixon.)

The next highest grouping of archival materials is the series level. The SAA Glossary defines a series as "file units or documents arranged in accordance with a filing system or maintained as a unit because they result from the same accumulation or filing process, the same function, or the same activity; have a particular form; or because of some other relationship arising out of their creation, receipt, or use."

The third grouping is the file unit level. The SAA Glossary defines a file unit as "an organized unit (folder, volume, etc.) of documents grouped together either for current use or in the process of archival arrangement." For NARA's descriptive practices, the file unit is the intellectual handling of the record item, which may or may not be the physical handling. In other words, a folder does not necessarily equal a file unit. For example, a case file may be in several physical folders, but is described as one file unit. For electronic records, the definition of a file unit level may be difficult. A file does not necessarily refer to a tape or to a particular data file.

The lowest grouping in the hierarchy is the item level, which is an individual item or a specific record. The SAA Glossary defines an item as "the smallest indivisible archival unit (e.g. a letter, memorandum, report, leaflet, or photograph." NARA would add that it is the smallest intellectually indivisible item. For example, a book or record album would be described as an item, but the individual chapters of the book or the discs or songs that make up the album would not be described as items.

There are separate elements for describing digital objects. Digital objects are copies of NARA's archival holdings, such as textual records, still pictures, artifacts, and moving images, that have been digitized and made available online. Digital objects are linked to archival descriptions at the item or file unit level. Each archival item or file unit can have one or more digital objects, and each of these objects can be associated with the description of the archival item or file unit. For example, a double-sided one-page letter would have two digital objects; each digital object would be linked to the item level description of that letter.

Currently, standards have been developed for digital images only. Other formats, such as sound and moving image files, will be addressed in the future. All NARA imaging projects should adhere to the policies established by the directive NARA 816, Digitizing Activities for Enhanced Access.

The framework for each element consists of three things:

- a table of characteristics

- definition, purpose, relationship, and guidance statements

- examples, when appropriate

The table of characteristics contains information about the data structure of the element and the rules that affect how it can be used. The definition, purpose, relationship, and guidance statements explain what the element is, what it does, how it relates to other elements, and how to use it. References to elements are in bold. Examples are shown in gray-shaded boxes and are included to illustrate how information should be entered.

The Characteristics

The characteristics of each element may include:

- whether or not the element is mandatory

- whether or not the element is repeatable

- the data type and length for the element

- whether or not an authority source is used to enter information in the element

- the level(s) at which the element is available

- the type of digital object the element applies to

- whether or not the element is for audiovisual records only

- whether or not the element can be available to the public

What is Mandatory?

Mandatory means information must be entered in the element for a description to be considered complete. The mandatory elements are the minimum description for archival materials. Some elements are mandatory at certain levels of description but not at others. Some elements have relationships that require them to be used with other elements; those requirements are described in the relationship statements, not in the mandatory section of the table of characteristics.

What is Repeatable?

Repeatable means information may be entered more than once in one intellectual description, physical occurrence, or media occurence. For example, because a series can have more than one Former Record Group or Topical Subject Reference, these are repeatable elements. Because a series can have only one Record Group Number or Title, these are non-repeatable elements.

What is a Data Type?

There are four primary data types:

- variable character length

Variable character length means the information can be any kind of character, number or symbol. Long means the character length can be up to 2 gigabytes. Numeric means the information can only be numbers. Commas cannot be used in numeric elements. The identifier "NW-338-99-005" could not be entered in a numeric data type element because it contains both letters and symbols. Date means the information can only be in a date format (mm/dd/yyyy). Where appropriate, field length limitations are shown in parentheses after the data type.

What is an Authority Source?

In some elements information cannot be entered as free-text, but must be selected from an authority source, such as an authority file, authority list, or thesaurus. Authority sources are used to ensure information is entered into an element consistently to facilitate sorting or searching. Some of the authority sources are well-known, highly reputable products from the cataloging field, such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names® (TGN) or the Library of Congress Name Authority File (LCNAF). Some of the authority sources are lists that have been developed by NARA to specifically meet our needs, such as the Specific Access Restriction Authority List or Reference Unit Authority List.

What is Level Available?

Level available indicates the hierarchical level of description for which the element may be used: the record group or collection, series, file unit, or item. If a level is not named, then the element may not be used to describe archival materials at that level.

What is Type?

Type indicates what digital object type (e.g. image, sound, moving image) the element can be applied to.

What is Audiovisual Only?

"A/V Only" means the element may only be used to describe audiovisual materials. Audiovisual materials are moving images and sound recordings. Moving images are defined as: "A sequence of images that presents the illusion of motion or movement as they are advanced. Examples include motion pictures, videos, and other theatrical releases, shorts, news footage (including television newscasts and theatrical newsreels), trailers, outtakes, screen tests, training films, educational material, commercials, spot announcements, home movies, amateur footage, television broadcasts, and unedited footage. These may be in electronic form."

Sound recordings are defined as: "Digital or analog recordings for audio purposes only. Examples include radio broadcasts, public service or advertising spot announcements, recordings of meetings, oral histories, and speeches." "A/V only" elements can not be used for maps, charts, and photographs.

What is Public Element?

Public Element indicates whether or not the element and its contents can be made available to the general public. A small number of the elements are not appropriate for public display because they are used only for administrative purposes.

COMMENTS

Archival research is a methodological approach characterized by the methodical scrutiny and evaluation of pre-existing records, papers, artifacts, and materials with the objective of addressing ...

3 Introduction This paper introduces a largely unexplored approach in archival and recordkeeping research based on the theoretical and methodological premises of the field of practice theory.i Despite what the name suggests, practice theory is not a unified theoretical framework.ii Rather practice theory is an interdisciplinary research approach based on a set of ontological and epistemological

Archives Research Paper 250 pts For this writing assignment, you will be researching an issue, a person, a building, or something else that has ... Your angle can be pointing out an instance of injustice (racism on campus, for example), or it can simply be informative (the process of erecting a new building on campus). The point of this assignment

ace, the in-person archive visit.While COVID-19 has afected archival researchers in all career stages, particularly afe. ted are early career researchers. Aliza Luft (Assistant Professor, UCLA), for example, is waiting to hear whether her June visit to the Vatican. ecret Archive can be rescheduled. The Vatican has made new documents on the ...

before admitting researchers.• Removal of coats and bags: Another method used to discourage theft is requiring that researchers remove bulky outer clothing and store purses, bags, binders, and laptop cases. outside of the research area. Many archives have lockers or other monitored areas that researchers can use.

1794. Prior to this, archives were generally closed to all except a select few. • In Canada, archival institutions attempt to document Canadian history from all segments of the population and in all record formats. Government archives often hold private papers in addition to government records. This is known as Total Archives.

Examples of archival materials include: ... (The Archival Research Catalog) ... Some archives just have paper copies to use on-site, while others have word processing documents, PDF, or HTML/XML finding aids that can be viewed on their websites. Downloading and print options vary by repository. Some archives may provide digital copies of ...

For example: "Hoover Institution Archives, Daniel Lerner Collection, Box 52, Folder 1." It will then be up to your readers to find the actual documents in question once you have given them the folder information. When Your Research Paper is Complete. Archival research is steeped in traditions and etiquette.

Archival research is the process of extracting meaningful data from archives and has been conducted informally since the inception of recorded material. For-mal archival research methods are more recent, and it is suggested that they began to take shape in England in the eleventh century (Clanchy, 2012).

Archival research methods include a broad range of activities applied to facilitate the investigation of documents and textual materials produced by and about organizations. In its most classic sense, archival methods are those that involve the study of historical documents; that is, documents created at some point in the relatively distant ...

Abstract. Purpose -Archival research is a much under-rated and under-utilized method of research in management. studies. Yet multi-disciplinary undertakings being observed in recent times, such ...

The paper discusses archival research method analysis and how it serves as a memory institute to the scholars and readers. Content may be subject to copyright. as a memory ins tute. An archive ...

Finding Archival and other Primary Materials. ArchiveGrid; WorldCat - the first step is to search your topic here, restricting to "Archival" and/or "Internet" (for digitally available materials); Secondary Sources - Archival materials used for articles and books are cited in the references - this is a great way to find repositories and collections to support your research.

Chapter - Information Seeking and Research Methods This chapter will provide an overview of the variety of research subjects and methods. There was the book Research and the Manuscript Tradition (1997) and little has been published since (within the archival profession). It will incorporate non-archivist writing about archival research,

Archival Research is the investigation of hard data from files that organizations or companies have. US Census data are archival data. Telephone bills that are in the computers of the telephone company are another example. Fire departments keep records of fires, chemical spills, accidents and so forth, all of which constitute archived data.

Academia.edu is a platform for academics to share research papers. Archival Research Methods ... They analyze a random sample of 335 calls from an archival software database to identify the set of action sequence, or "moves," that constitute what they refer to as the "grammar for [the firm's] software support process" (1994:490); that ...

The relatively recent archival turn-the necessity to enter library archives for research-has resulted in an increased engagement with previously undiscov-ered materials throughout numerous fields. ... The acquisition of women's and women's organization's archives/papers/records and their preservation in an archive center is a new field of ...

How to Cite Archival Materials. You have two viable options for citing archival sources. Check the archives website or contact them for a preferred citation. Use the adapted MLA citation we propose below. If you choose Option 1, first check the website of the library or archival system, which may contain guidelines, or LibGuides, for ...

Your research may focus on a single textual document, or it might require you to look at tens of boxes (if not more)! Whether your research is a long-term project (like a thesis or book), or a short-term project (like a paper or blog post), knowing the basics of how to do archival research before you start can save you time and energy later on.

The use of archival data can help with current research by using a thorough review of what was already available through various sources (Schultz, Hoffman, & Reiter-Palmon, 2005).

advice for working in the archives. While this special issue of CCC is specifi cally devoted to research methodologies, in archival investigation examining methodologies and methods in tandem is critical given the nature of primary research, as this essay demonstrates. In "An Argument for Archival Research. CCC 64:1 / SEPTEMBER 2012.

The following scenario is a hypothetical example of the archival research process applied to answer an appropriate research question. A scholar of Icelandic literature is interested in the relationship between the original physical structure and format of ancient sagas of Icelanders (Íslendingasögur) and their textual content.

It actively engages debates about archival theory and societal roles in diverse archival and cultural jurisdictions. The specialization comprises a range of courses, experiential components, and research opportunities. Courses explore the full spectrum of archival materials (e.g., paper and electronic records, manuscripts, still and moving ...

When digital objects, such as digital reproductions of photographs, are included, they also are linked to the archival description. One archival item or file unit can have many digital objects. For example, each scanned page of a letter would be a digital object, and each would be attached to the archival description. Archival Materials Elements