This browser is no longer supported.

Upgrade to Microsoft Edge to take advantage of the latest features, security updates, and technical support.

Flipped instruction with PowerPoint Recorder

At a glance

Course Duration

Achievement Code

Would you like to request an achievement code?

Use PowerPoint Recorder to flip instruction, provide content for students outside of class, and help improve student outcomes.

Course Syllabus

You can prepare in instructor-led training or self-paced study

Start course

Effective Visual Presentations

Flipped learning module.

Each Flipped Learning Module (FLM) is a set of short videos and online activities that can be used (in whole or in part) to free up class time from content delivery for greater student interaction. At the end of the module, students are asked to fill out a brief survey, in which we adopt the minute paper strategy . In this approach, students are asked to submit their response to two brief questions regarding their knowledge of the module.

In this FLM, students are asked to complete a fill-in-the-blank outline which accompanies all three videos, covering the topics of designing visual presentations as well as presenting them. The completed outline will enhance the students’ note-taking skills and will serve as a summary of the FLM that they may refer to in the future.

purpose, topic, audience, design elements, visuals, body language, voice, pace

Module Overview Why give Visual Presentations? Introduction Getting Started Designing the Presentation The Main Points Writing for the Presentation Design Elements Visuals Presenting Focus on the Oral Presentation Body Language and Voice Finishing up Download Video Transcripts

Worksheet: Effective Visual Presentations Outline

- __________________________________

- (Consideration 1) _________________________

- (Consideration 2) _________________________

- (Consideration 3) _________________________

- The introduction slide of your visual presentation should include ____________________________________.

- ________________ fonts are better suited for slide presentations because ______________________________.

- Embedding video clips into your presentation could be effective as long as ____________________________.

- (Recommendation 1) ___________________________________________

- (Recommendation 2) ___________________________________________

- (Recommendation 3) ___________________________________________

Download Outline

Video 1: Why give Visual Presentations?

Video 2: designing the presentation, effective visual presentations online activity 1.

Effective Visual Presentations Online Activity 2

Submit your response to your instructor.

Effective Visual Presentations Online Activity 3

Effective Visual Presentations Online Activity 4

Video 3: Presenting

Effective visual presentations survey.

- What was the one most important thing you learned from this module?

- Do you have any unanswered questions for me?

Effective Visual Presentations In-Class Activity

We will then watch the first 5 minutes of President Obama’s 2004 Democratic Convention speech delivered before he became President. Make a note of how Obama uses some of the techniques mentioned in the first video. Write down the presentation techniques that you notice, and discuss these techniques with your team members. We will also have a whole-class discussion.

Download Worksheet

Download Digital Implementation of the Activity

Ball, Cheryl E., Jennifer Sheppard, and Kristin L. Arola. Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects . Bedford/St. Martins, 2018.

Ball, Cheryl E. and Kristin L. Arola. ix: visual exercises [CD-ROM]. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004.

“ Designing Effective PowerPoint Presentations .” The Purdue OWL , Purdue U Writing Lab.

Smith, Andrew. “ How PowerPoint is killing critical thought .” The Guardian, 23 September 2015.

Thompson, Clive. “ 2003: The 3rd Annual Year in Ideas; PowerPoint Makes You Dumb .” The New York Times , 14 December 2003.

The Innovative Instructor

Pedagogy – best practices – technology.

PowerPoint in the Classroom

Do you use PowerPoint (or Keynote, Prezi or other presentation software) as part of your teaching? If yes, why? This is not meant to be a question that puts you on the defensive, rather to ask you to reflect on how the use of a presentation application enhances your teaching and fits in with other strategies to meet your learning objectives for the class.

A key point from that post to reiterate: “Duarte reports on research showing that listening and reading are conflicting cognitive processes, meaning that your audience can either read your slides or listen to you; they cannot do both at the same time. However, our brains can handle simultaneous listening to a speaker and seeing relevant visual material.”

It’s important to keep this in mind, particularly if your slides are text heavy. Your students will be scrambling to copy the text verbatim without actually processing what is being said. On the other hand, if your slides are used as prompts (presenting questions or key points with minimal text) or if you don’t use slides at all, students will have to listen to what you are saying, and summarize those concepts in their notes. This process will enhance their understanding of the material.

An article in Focus on Teaching from August 1, 2012 by Maryellen Weimer, PhD asks us to consider Does PowerPoint Help or Hinder Learning? Weimer references a survey of students on the use of PowerPoint by their instructors. A majority of students reported that all or most of their instructors used PowerPoint. Weimer’s expresses the concern that “Eighty-two percent [of students surveyed] said they “always,” “almost always,” or “usually” copy the information on the slides.” She asks, “Does copying down content word-for-word develop the skills needed to organize material on your own? Does it expedite understanding the relationships between ideas? Does it set students up to master the material or to simply memorize it?” Further, she notes that PowerPoint slides that serve as an outline or use bulleted lists may “oversimplify” complex content, encourage passivity, and limit critical thinking.

Four journal articles from Cell Biology Education on PowerPoint in the Classroom (2004 Fall) present different points of view (POV) on the use of PowerPoint. Although written over a decade ago, most of the concepts are still relevant. Be aware that some of the links are no longer working. From the introduction to the series:

Four POVs are presented: 1) David Keefe and James Willett provide their case why PowerPoint is an ideal teaching software. Keefe is an educational researcher at the Center for Technology in Learning at SRI International. Willett is a professor at George Mason University in the Departments of Microbial and Molecular Bioscience; as well as Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. 2) Kim McDonald highlights the causes of PowerPointlessness, a term which indicates the frequent use of PowerPoint as a crutch rather than a tool. She is a Bioscience Educator at the Shodor Education Foundation, Inc. 3) Diana Voss asks readers if PowerPoint is really necessary to present the material effectively or not. Voss is a Instructional Computing Support Specialist at SUNY Stony Brook. 4) Cynthia Lanius takes a light-hearted approach to ask whether PowerPoint is a technological improvement or just a change of pace for teacher and student presentations. Lanius is a Technology Integration Specialist in the Sinton (Texas) Independent School District.

These are short, op-ed style, pieces that will further stimulate your thinking on using presentation software in your teaching.

For more humorous, but none-the-less thought provoking approach, see Rebecca Shuman’s anti-PowerPoint tirade featured in Slate (March 7, 2014): PowerPointless . With the tagline, “Digital slideshows are the scourge of higher education,” Shuman reminds us that “A presentation, believe it or not, is the opening move of a conversation—not the entire conversation.”

Shuman offers a practical guide for those, like her, who do use presentation software, but seek to avoid abusing it. “It is with a few techniques and a little attention, possible to ensure that your presentations rest in the slim minority that are truly interactive and actually help your audience learn.” Speaking.io , the website Shuman references, discusses the use of presentation software broadly, not just for academics, but has many useful ideas and tips.

For a resource specific to academic use, see the University of Central Florida’s Faculty Center for Teaching & Learning’s Effective Use of PowerPoint . The experts at the Center examine the advantages and challenges of using presentation software in the classroom, suggest approaches to take, and discuss in detail using PowerPoint for case studies, with clickers, as worksheets, for online (think flipped classes as well) teaching, the of use presenter view, and demonstrate best practices for delivery and content construction.

Macie Hall, Senior Instructional Designer Center for Educational Resources

Image Source: CC Oliver Tacke https://www.flickr.com/photos/otacke/12635014673/

One thought on “ PowerPoint in the Classroom ”

This post offers a well-framed discussion of the pedagogical choices behind presentation choices we make in our classes–thanks!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Flip Your Classroom

what is a “flipped” class.

Flipping the classroom is a pedagogical approach where students first explore new course content outside of class by viewing a pre-recorded lecture video or digital module, or completing a reading or preparatory assignment. In-class time is organized around student engagement, inquiry, and assessment, allowing students to grapple with, apply, and elaborate on course concepts. In-class sessions typically entail collaborative coursework and use of active learning strategies , including case studies, problem sets, or structured discussion.

There are a number of reported benefits to implementing flipped classrooms, including:

More individualized help during class time, as an instructor can be “guide on the side”, rather than “sage on the stage.”

More opportunities for deliberate practice and increased support for students as they grapple with higher order disciplinary concepts and problems.

More opportunities for students to interact with their instructor as well as peers.

Student control over the pace of lectures: if providing video lectures, students can watch, rewind, and fast-forward as needed.

Resiliency: since the lecture-style material is pre-recorded, in-classroom activities are flexible, and classes are less likely to fall behind if technology or life circumstances interfere with a synchronous course session. Depending on the content, out-of-class materials can also be used in future semesters.

Recent studies suggest that the benefits of flipped classrooms are due, in part, to the incorporation of in-class activities, collaboration, and active learning strategies that have been shown to enhance student learning (see, for example, DeLozier & Rhodes, 2017; Jensen et al., 2015; Means et al. , 2009).

Models of Flipped Classrooms

Standard flipping.

Lectures are recorded (either as video or as narrated screencasts). Students are required to watch these lectures as homework and then spend class time doing problem-solving or other highly interactive, structured activities, usually in groups and with guidance from instructors and GSIs.

In-class activities could include in-class discussion, problem-solving, or group work exercises. They could also be technology-enhanced activities, such as:

Use polling to gauge student understanding of course topics and leverage poll results to spur discussion and/or individual and/or group problem-solving

Example polling tools supported at UC Berkeley are PollEverywhere, Top Hat, and Google Forms.

Offer class time for students to work collaboratively using shared documents, including bDrive (Google Drive) Docs, Sheets, Slides, Forms, and (link is external) Jamboard.

Groups can be formed using bCourses Groups , Collaborations , or bCourses SuiteC

For additional collaborative learning ideas, see: Barkley, Elizabeth F., K. Patricia Cross, and Claire H. Major. Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty . John Wiley & Sons, 2014. (Digital copies available through the UC Berkeley Library; includes adaptations for online courses)

One-day-a-week flipping

If a standard flip seems overwhelming, or not appropriate for your class, try flipping one lecture a week. UCB Chemistry instructor, Michelle Douskey, has done “Flipped Fridays”, where she recorded a short lecture video, which students watch to prepare for class. During class students worked in groups to complete tasks where they were solving real analytical problems. Answers were presented in class and students were asked to correct their own work and reflect on their understanding. (See Michelle's presentation on this at the 2016 Showcase of Teaching Innovation and Reinvention (STIR) )

Selected-content flipping

Lecturing does not have to be completely eliminated from your class time. Instead, be selective and strategic about what you record for students to watch in advance. You might record only a subset of lecture materials, and reserve some of your class time for lecturing on advanced topics. Are there particular topics or concepts on which students routinely get stuck? Try designing in-class activities around these ideas or concepts. Or, consider recording lectures that cover content that’s likely to be reusable in future semesters, and plan on some in-class microlectures covering “hot-off-the-presses” topics, leaving plenty of time for active learning.

Flipping without recording video lectures

It’s a common misconception that instructors can only flip if they pre-record their lectures, which admittedly can be a time-consuming process. Instructors can, instead, find other ways for students to get content that might typically be delivered in a lecture: readings can be used, as well as other content such as powerpoint presentations, podcasts, or videos or animations that others have recorded.

Full hybrid flipping

Eliminate some in-class lectures completely and replace those in-class hours with time students are expected to complete online activities, typically watching the lecture. (Note: switching an existing class to a full hybrid flipped course requires approval from Committee on Courses of Instruction, COCI; see https://academic-senate.berkeley.edu/coci-handbook for more information.)

Things to Keep in Mind…

Experiment and iterate.

Flipping a whole class is no small endeavor. Start with small, strategic changes. As you become more familiar with the tools and approaches, explore ways to expand time spent in class on collaborative and active learning.

Tips for Videos (see Brame, 2016)

Aim for multiple short videos rather than one long video -- this will help to ease the technical work for instructors and better align with student attention and learning

Draw attention to or highlight important ideas or concepts.

Complement videos with guiding questions, interactive elements, or reflective components.

Remote Group Work, and Collaboration

Consider practices that will help student groups to function most successfully and equitably, particularly as they navigate collaboration in remote contexts, including group norms and roles (see also: Raygoza, León, & Norris, 2020 )

Thinking about Flipping Your Class?

The Center for Teaching and Learning offers one-on-one faculty consultations to support your efforts to flip your classroom environment. CTL staff can answer your pedagogical questions, serve as thought partners, and share resources as you determine learning goals, content, teaching practices, and assessments for your course.

Additional Resources

Flipping Your Class , University of Michigan Center for Research on Teaching and Learning

Flipping the Classroom , Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching

Flipped Classrooms , Educause Library

Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE—Life Sciences Education , 15 (4), es6. (See also: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/effective-educational-videos/ )

DeLozier, S. J., & Rhodes, M. G. (2017). Flipped classrooms: a review of key ideas and recommendations for practice. Educational Psychology Review , 29 (1), 141-151.

Jensen, J. L., Kummer, T. A., & Godoy, P. D. D. M. (2015). Improvements from a flipped classroom may simply be the fruits of active learning. CBE—Life Sciences Education , 14 (1), ar5.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development

Raygoza, M., León, R., & Norris, A. (2020). Humanizing online teaching. http://works.bepress.com/mary-candace-raygoza/28/

Barkley, E.F., Cross K..P, & Major C.H. (2014). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. John Wiley & Sons. (available online via UC Berkeley Library/Oskicat).

Crouch, C. H., & Mazur, E. (2001). Peer instruction: Ten years of experience and results. American journal of physics , 69 (9), 970-977.

Deslauriers, L., Schelew, E., & Wieman, C. (2011). Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class. Science , 332 (6031), 862-864.

Kerr, B. (2015). The flipped classroom in engineering education: A survey of the research. In 2015 International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL) (pp. 815-818). IEEE.

Lage MJ, Platt GJ, and Treglia M (2000). Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. The Journal of Economic Education 31: 30-43.

Figure: Flipped Classroom Introduction, UMichigan CRLT

Flipped learning: What is it, and when is it effective?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, patricia roehling and patricia roehling professor emeritus of psychology - hope college carrie bredow carrie bredow associate professor of psychology - hope college.

September 28, 2021

Instructors are constantly on the lookout for more effective and innovative ways to teach. Over the last 18 months, this quest has become even more salient, as COVID-19 has shaken up the academic landscape and pushed teachers to experiment with new strategies for engaging their students. One innovative teaching method that may be particularly amenable to teaching during the pandemic is flipped learning. But does it work?

In this post, we discuss our new report summarizing the lessons from over 300 published studies on flipped learning. The findings suggest that, for many of us who work with students, flipped learning might be worth a try.

What is flipped learning?

Flipped learning is an increasingly popular pedagogy in secondary and higher education. Students in the flipped classroom view digitized or online lectures as pre-class homework, then spend in-class time engaged in active learning experiences such as discussions, peer teaching, presentations, projects, problem solving, computations, and group activities. In other words, this strategy “flips” the typical presentation of content, where class time is used for lectures and example problems, and homework consists of problem sets or group project work. (See Roehling, 2018 , for information on how to construct and implement flipped learning.)

Flipped learning is not simply a fad. There is theoretical support that it should promote student learning. According to constructivist theory, active learning enables students to create their own knowledge by building upon pre-existing cognitive frameworks, resulting in a deeper level of learning than occurs in more passive learning settings. Another theoretical advantage of flipped learning is that it allows students to incorporate foundational information into their long-term memory prior to class. This lightens the cognitive load during class, so that students can form new and deeper connections and develop more complex ideas. Finally, classroom activities in the flipped model can be intentionally designed to teach students valuable intra- and interpersonal skills.

Since 2012, the research literature on the effectiveness of flipped learning has grown exponentially. However, because these studies were conducted in many different contexts and published across a wide range of disciplines, a clear picture of whether and when flipped classrooms outperform their traditional lecture-based counterparts has been difficult to assemble.

To address this issue, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of flipped pedagogies ; this review focused specifically on higher education contexts. For our meta-analysis, we combined data from 317 studies (51,437 participants) that compared the effectiveness of flipped and lecture-based courses taught by the same instructor.

We assembled all of these studies to examine the efficacy of flipped versus lecture-based learning for fostering a variety of outcomes in higher education. Specifically, we examined outcomes falling into three broad categories:

- Academics , including exams and assignments measuring foundational knowledge, higher-order thinking, and applied/professional skills;

- Intra-/interpersonal aptitudes , including student engagement and identification with the course or discipline, metacognitive skills, and interpersonal skills; and

- Satisfaction with the course and instruction as reported by students.

We also explored the extent to which factors related to educational context (e.g., discipline, geographic location) and course design (e.g., the use of quizzes to motivate pre-class preparation) may shape the effectiveness of flipped learning. Below, we outline some of the key takeaways of our meta-analytic synthesis.

Is flipped learning more effective than lecture-based learning?

Yes, it certainly can be. Students in flipped classrooms performed better than those in traditionally taught classes across all of the academic outcomes we examined. In addition to confirming that flipped learning has a positive impact on foundational knowledge (the most common outcome in prior reviews of the research), we found that flipped pedagogies had a modest positive effect on higher-order thinking. Flipped learning was particularly effective at helping students learn professional and academic skills.

Importantly, we also found that flipped learning is superior to lecture-based learning for fostering all intra-/interpersonal outcomes examined, including enhancing students’ interpersonal skills, improving their engagement with the content, and developing their metacognitive abilities like time management and learning strategies.

In which educational settings is flipped learning most effective?

Flipped learning was shown to be more effective than lecture-based learning across most disciplines. However, we found that flipped pedagogies produced the greatest academic and intra-/interpersonal benefits in language, technology, and health-science courses. Flipped learning may be a particularly good fit for these skills-based courses, because class time can be spent practicing and mastering these skills. Mathematics and engineering courses, on the other hand, demonstrated the smallest gains when implementing flipped pedagogies.

The relative benefits of flipped learning also vary based upon geographic location across the globe. Whereas flipped courses outperformed lecture courses in all of the regions that were adequately represented in our meta-analysis, flipped classes in Middle Eastern and Asian countries produced greater academic and intra-/interpersonal gains than flipped courses implemented in Europe, North America, or Australia. These findings suggest that flipped learning may have the greatest impact in courses that, in the absence of flipped learning, adhere more strictly to a lecture-format, as is often the case in the Middle East and Asia. However, we might expect benefits in any context where active learning is used less regularly.

How can you design an effective flipped course?

When designing a flipped course, the conventional wisdom has been that instructors should use pre-class quizzes and assignments to ensure that students are prepared to participate in and benefit from the flipped class period. Surprisingly, we found little support for this in our analysis. While using in-class quizzes did not affect learning outcomes, using pre-class quizzes and assignments to hold students accountable actually produced lower academic gains. It’s unclear why this is the case. It may be that pre-class assignments shift the focus of student preparation; rather than striving to understand the course material, students focus on doing well on the quiz. This suggests that, to hold students accountable for pre-class preparation, instructors should consider using in-class quizzes and assessments rather than pre-class assignments.

We also found that more isn’t always better. Compared to courses where all (or nearly all) class sessions followed the flipped model (“fully flipped”), courses that combined flipped and lecture-based approaches (“partially flipped”) tended to produce better academic outcomes. Given the time and skill required to design effective flipped class sessions, partially flipped courses may be easier for instructors to implement successfully, particularly when they are new to the pedagogy. Partially flipped courses also give instructors the flexibility to flip content that lends itself best to the model, while saving more complex or foundational topics for in-class instruction.

What about student satisfaction?

Another reason to consider flipped learning is student satisfaction. We found that students in flipped classrooms reported greater course satisfaction than those in lecture-based courses. The size of this overall effect was fairly small, so flipping the classroom is not a silver bullet for instantly boosting course evaluations. But in no context did flipping the classroom hurt course ratings, and in some settings, including mathematics courses and courses taught in Asia and Europe, we observed more pronounced increases in student satisfaction.

Adopting a new pedagogy can be daunting, and a significant barrier to converting a course to a flipped format is the substantial time commitment involved in creating digitized lectures. However, during the 2020-2021 pandemic surges, many instructors were encouraged (if not forced) to find new ways of teaching, leading many to record their lectures or create other supplementary digital content. For instructors who have now created such digital content, this could be a great time to experiment with flipped learning.

Related Content

Bruce Fuller

March 4, 2021

Stephanie Riegg Cellini

August 13, 2021

Education Technology Higher Education

Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Brown Center on Education Policy

Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly, Landry Signé, George Ingram, Priya Vora, Rebecca Winthrop, Caren Grown, Belinda Archibong, Brad Olsen, Jennifer L. O’Donoghue, Sweta Shah

September 19, 2024

Adam Looney, Constantine Yannelis

September 17, 2024

Brad Olsen, Molly Curtiss Wyss, Maya Elliott

September 16, 2024

- Skip to main content

- Skip to main navigation

Effective PowerPoint

PowerPoint is common in college classrooms, yet slide technology is not more effective for student learning than other styles of lecture (Levasseur & Sawyer, 2006). While research indicates which practices support learning and clarifies students’ attitudes toward PowerPoint, effective PowerPoint is not an exact science; few rules can be applied universally. Instructors should consider their audience and their pedagogical goals.

What Students Think

Although students do not necessarily learn more when PowerPoint is used, students prefer slide technology and think they learn better from it (Suskind, 2005). Students also rate instructors who use PowerPoint more highly. One study found about a six percent bump in student ratings of instructors who use PowerPoint over those who don’t (Apperson et al., 2006). Students indicate that what they like most about PowerPoint is that it organizes information, keeps them interested, and helps “visual learners” (Hill et al., 2012). They also, however, critique PowerPoint when slides have too many words, irrelevant clip art, unnecessary movement or animations, and too many colors (Vanderbilt University).

Research-Supported Methods

Like all teaching methods, the use of PowerPoint requires that teachers consider and make use of students’ need for variety. If used as one tool among many, lecturing with PowerPoint adds variety to a course, possibly minimizing student distractions (Bunce et al, 2010).

Minimal Text

In the interest of variety, PowerPoint lectures should not be excessively long, but the number of slides used in lectures has no direct impact on teaching effectiveness. However, the amount of text per slide is consequential. One study found that slides containing three or fewer bullet points and twenty or fewer words were more effective than slides with higher density (Brock, et al., 2011). Less text on each slide also reduces the amount of simultaneous delivery of material in text and speech, that is, presenters reading out loud the text on the slide, which is an additional barrier to comprehension. Studies show that audiences comprehend less when the same material is simultaneously delivered by text and speech and that for many settings, audio-only delivery of text is more effective.

This process is explained by the cognitive load theory , which states that since working memory is limited and each form of presentation of new material (written text, audio instruction, visual diagram, etc.) requires its own allotment of working memory to process, the amount of working memory available for learning is hindered by unnecessary redundancies in presentation. These effects are more pronounced when multiple presentations of information are processed in the same cognitive domain—such as audio instructions and visual text, both processed in the language domain, known as the “phonological loop” (Kalyuga et al., 2004).

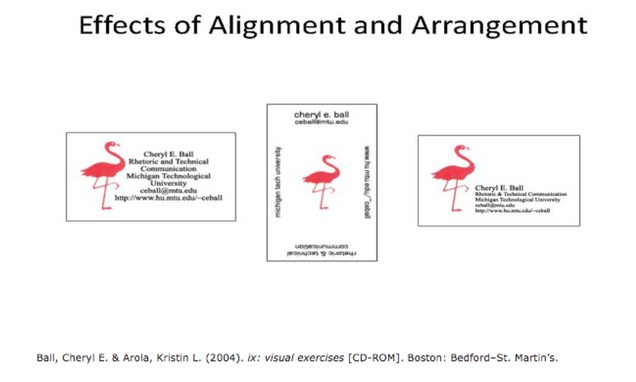

Assertion-Evidence Method

The traditional use of PowerPoint, determined mostly by software programming defaults, involves crafting slides with a topic, question, or theme in the upper banner, followed by text bullet points in the body of the slide. A more effective way to present material is with the Assertion-Evidence Method (see graphic), in which the top banner makes an assertion, written in sentence form (think of crafting the assertion in the style of a newspaper headline). The body of the slide then contains visual evidence of the assertion—if possible, in the form of a simple chart, but pictures and brief text can also serve as evidence. This method has been linked with better understanding and long-term retention (Garner & Alley, 2013).

Traditional Topic and Bullet-Point Method

Practical Tips

The research above—as well as research about learning in general—encourages certain practices when using PowerPoint:

- For variety, use the hyperlink or embed features of PowerPoint to incorporate audio or video media.

- To reduce cognitive load, blank out the projector when answering a question or dealing with an issue not directly related to the slide.

- Also to reduce cognitive load, don’t talk while students are writing. If you have minimal text, the instructor should be able—without much disruption in the flow of oration—to display the text and let students silently read before proceeding to elaborate.

- To encourage interactive learning , incorporate questions into PowerPoint presentations. These can be used for discussion, pause-and-ponder, brief writing exercises, etc.

Apperson, J., Laws, E., & Scepansky, J. (2006). The impact of presentation graphics on students’ experience in the classroom. Computers & Education 47 , 116-126.

Brock, S. Joglekar, Y., & Cohen, E. (2011). Empowering PowerPoint: Slides and teaching effectiveness. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge & Management, 6 , 85-94.

Bunce, D. M., Flens, E. A., & Neiles, K. Y. (2010). How long can students pay attention in class? A study of student attention using clickers. Journal of Chemical Education , 87 (12, 1438-1443.

Garner, J. K., & Alley, M. P (2013). How the design of presentation slides affects audience comprehension: A case for the assertion-evidence approach. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29 (6), 1564-1579.

Hill, A., Arford, T., Lubitow, A., & Smollin, L. M. (2012). “I’m ambivalent about it”: The dilemmas of PowerPoint. Teaching Sociology, 40 (3), 242-256.

Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2004). When redundant on-screen text in multimedia technical instruction can interfere with learning. Human Factors, 46 (3), 567-581.

Levasseur, D. G., & Sawyer, J. K. (2006). Pedagogy meets PowerPoint: A research review of the effects of computer-generated slides in the classroom. The Review of Communication, 6 (1/2), 101-123.

Making better PowerPoint presentations (n.d.). Vanderbilt University, Center for Teaching (webpage). Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/ .

Suskind, J. E. (2005). PowerPoint’s power in the classroom: Enhancing students’ self-efficacy and attitudes. Computers & Education, 45 (2), 203-215.

Academy for Teaching and Learning

Moody Library, Suite 201

One Bear Place Box 97189 Waco, TX 76798-7189

- General Information

- Academics & Research

- Administration

- Gateways for ...

- About Baylor

- Give to Baylor

- Social Media

- Strategic Plan

- College of Arts & Sciences

- Diana R. Garland School of Social Work

- George W. Truett Theological Seminary

- Graduate School

- Hankamer School of Business

- Honors College

- Louise Herrington School of Nursing

- Research at Baylor University

- Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences

- School of Education

- School of Engineering & Computer Science

- School of Music

- University Libraries, Museums, and the Press

- More Academics

- Compliance, Risk and Safety

- Human Resources

- Marketing and Communications

- Office of General Counsel

- Office of the President

- Office of the Provost

- Operations, Finance & Administration

- Senior Administration

- Student Life

- University Advancement

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Baylor Law School Admissions

- Social Work Graduate Programs

- George W. Truett Theological Seminary Admissions

- Online Graduate Professional Education

- Virtual Tour

- Visit Campus

- Alumni & Friends

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Anonymous Reporting

- Annual Fire Safety and Security Notice

- Cost of Attendance

- Digital Privacy

- Legal Disclosures

- Mental Health Resources

- Web Accessibility

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

26 Blended Learning and Flipped Instruction

Teaching strategies: blended learning and flipped instruction.

Blended learning refers to a teaching strategy that utilizes both face-to-face classroom meetings as well as technology-enhanced learning outside of the classroom. This strategy is also sometimes called hybrid learning (although hybrid learning is also sometimes thought of as a slightly different strategy.) One popular format for blended learning is the flipped instructional model (Tucker, 2012). One of the overarching goals of blended learning and flipped instruction is to give students the best elements of face-to-face instruction and self-paced and interactive online activities. The flipped classroom is a pedagogical model in which the typical lecture and homework elements of a course are reversed.

A departure from the more common transmittal model, flipped instruction is grounded in the constructivist model, which presents learning as an active, social process in which learners use existing knowledge and prior experiences to build an individual understanding of new material (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989). As a means to integrate the constructivist model into their classrooms, teachers are now utilizing technology to implement a blended method that shifts lectures out of the classroom and onto the internet in order to free up class time for collaborative activities (Shimamoto, 2012). Instructors have determined that instructional videos were valuable in shifting the lower level of bloom’s taxonomy out of the class, which enables the class to spend more time at the upper end of the taxonomy, with tasks that ask students to apply, analyze, evaluate and create (Sams & Bergmann, 2013).

LinkedIn Learning Playlists:

- Teaching Techniques: Blended Learning

- Flipping the Classroom

Typically speaking, having lectures available to students online and outside of class allows students a more self-paced approach to their learning. Students are free to re-watch and re-wind instructor lectures to ensure they are understanding key concepts. Additionally, as instructors make their lectures available online, a digital repository can be made available for students who are interested in further explanation, or review of concepts, all the while encouraging active learning and supporting 21st-century on-demand expectations.

Quick Start Guide – Flipping 101

Employing this strategy can be somewhat ambiguous, and may require careful planning in order to yield meaningful results, in fact, a whole section of this document is designated to exploring more about the best practices of this strategy – see our ‘On the Web’ section. Considering that, Instructional Design Services would like to provide some suggestions on how to begin to flip your class.

Plan Your Lesson

Flipping your instruction does not have to come all at once, in fact, we suggest starting with a lesson or two before determining if the strategy is right for your coursework and students. When examining your first lesson, consider the lesson objectives, and whether or not it lends itself to video instruction. If the lesson is conducive to this type of strategy, we suggest using materials that you have previously created. Old lecture notes, PowerPoint slides, etc. can be amended and revised for this purpose. This can be a daunting task, but it is imperative to the successful implementation of blended course content. In order to help you with your planning, we recommend that you use our Flipped Instruction Planning Template. This template helps you consider crucial planning elements for your flipped instruction. If you would prefer this document in another format (.docx or PDF), please contact Instructional Design Services.

Record Lecture/Video

This can happen in a variety of ways, however, for simplicity, Instructional Design Services offers a software solution for this called MediaSpace / Kaltura Capture . MediaSpace and Kaltura Capture are fully-supported lecture capture solutions provided for Faculty, Staff, and even Student use. This software allows you to record your lectures directly from your office, or anywhere else you might have access to your computer or laptop with a microphone and camera (commonly built-in).

- When recording your video, it is recommended that you have an outline, or guide for your lesson. This might be your PowerPoint slides or notes.

- Do not worry about creating or following a script, your students will appreciate the more conversational and lecture qualities of your recordings.

- Within the MediaSpace website, editing your video is possible. Typically, this is only used to trim the beginning and the end of your videos. Highly stylized video editing is not necessary, nor is it recommended.

Publish the Video

Once your lesson has been recorded, you will have to publish your video and find a way to make it available to your students. Instructional Design Services recommends that you try to find a web-hosted solution, such as MediaSpace for this step. Web-hosted videos are easily shared with students through web links that you can add to your D2L course. You can access your MediaSpace video list directly from D2L. An additional benefit of web-hosted video is that it is software agnostic, which means your students can view your materials without having to have special software. A modern and updated web browser is all that is required.

- In-Class Activities – Considering that you’ve now freed up class time that you may have otherwise spent on lectures, what will your classroom activities look like now? Common to this approach, class time can be spent on doing interactive, group-based labs, or activities. Benefits of this include:

- Students can receive instant feedback, and teachers have more time to help students and explain difficult concepts.

- Ease student frustrations when they have a hard time understanding a concept by revisiting ideas and working through those problems in class, collaboratively.

- Students who understand the concepts can assist others who are having difficulty.

This section outlines how you might begin to think about adopting the aforementioned teaching strategy and the tools you might consider employing.

- MediaSpace – MediaSpace/Kaltura Capture is our enterprise screen recording solution that we have available for all current faculty, staff, and students. This tool allows you to easily record and share presentations, lectures, meetings, and mobile videos from virtually anywhere. It is fully integrated with our statewide media management system, Kaltura, so it is trivial to record and post your lectures.

- HD Recording Studio – Instructional Design Services has a high-definition recording studio available for use by all faculty. The studio is outfitted with an HD camera, touch screen podium, and professional quality sound and lighting equipment. This is a great option for instructors who might not want to fuss around with their own technology. This studio is managed by a student worker, and thus, instructors need only to schedule a time, provide lecture slides in advance, and show up to make their lecture. The student worker coordinates with the instructor to determine any editing that might be needed. Once the recording and editing are complete, which typically has a 2-2-4-day turnaround, the student worker makes the video available to the instructor via their MediaSpace account, or by the video file.

- Zoom – By sharing your screen and your presentation, Zoom will capture audio, video, and your screen or any combination you are comfortable with. By “recording to the cloud”, Zoom will send your video directly to your Mediaspace account, making it easy to then pull it into D2L.

- Forbes.com Article and Infographic on the ‘gist’ of what is Flipped Instruction.

- Knewton.com – Flipped Classroom Infographic

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18 ,32-42.

Sams, A., & Bergmann, J. (2013). Flip your students’ learning. Educational Leadership, 70 (6), 16-20.

Shimamoto, D. (2012, April). Implementing a flipped classroom: An instructional module. TCC Conference.

Tucker, B. (2012) The flipped classroom. Education Next, 12 (1). Retrieved from http://educationnext.org/the-flipped-classroom/

Maverick Learning and Educational Applied Research Nexus Copyright © 2021 by Minnesota State University, Mankato is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

- Instructional Guide

Teaching with PowerPoint

When effectively planned and used, PowerPoint (or similar tools, like Google Slides) can enhance instruction. People are divided on the effectiveness of this ubiquitous presentation program—some say that PowerPoint is wonderful while others bemoan its pervasiveness. No matter which side you take, PowerPoint does offer effective ways to enhance instruction when used and designed appropriately.

PowerPoint can be an effective tool to present material in the classroom and encourage student learning. You can use PowerPoint to project visuals that would otherwise be difficult to bring to class. For example, in an anthropology class, a single PowerPoint presentation could project images of an anthropological dig from a remote area, questions asking students about the topic, a chart of related statistics, and a mini quiz about what was just discussed that provides students with information that is visual, challenging, and engaging.

PowerPoint can be an effective tool to present material in the classroom and encourage student learning.

This section is organized in three major segments: Part I will help faculty identify and use basic but important design elements, Part II will cover ways to enhance teaching and learning with PowerPoint, and Part III will list ways to engage students with PowerPoint.

PART I: Designing the PowerPoint Presentation

Accessibility.

- Student accessibility—students with visual or hearing impairments may not be able to fully access a PowerPoint presentation, especially those with graphics, images, and sound.

- Use an accessible layout. Built-in slide template layouts were designed to be accessible: “the reading order is the same for people with vision and for people who use assistive technology such as screen readers” (University of Washington, n.d.). If you want to alter the layout of a theme, use the Slide Master; this will ensure your slides will retain accessibility.

- Use unique and specific slide titles so students can access the material they need.

- Consider how you display hyperlinks. Since screen readers read what is on the page, you may want to consider creating a hyperlink using a descriptive title instead of displaying the URL.

- All visuals and tables should include alt text. Alt text should describe the visual or table in detail so that students with visual impairments can “read” the images with their screen readers. Avoid using too many decorative visuals.

- All video and audio content should be captioned for students with hearing impairments. Transcripts can also be useful as an additional resource, but captioning ensures students can follow along with what is on the screen in real-time.

- Simplify your tables. If you use tables on your slides, ensure they are not overly complex and do not include blank cells. Screen readers may have difficulty providing information about the table if there are too many columns and rows, and they may “think” the table is complete if they come to a blank cell.

- Set a reading order for text on your slides. The order that text appears on the slide may not be the reading order of the text. Check that your reading order is correct by using the Selection Pane (organized bottom-up).

- Use Microsoft’s Accessibility Checker to identify potential accessibility issues in your completed PowerPoint. Use the feedback to improve your PowerPoint’s accessibility. You could also send your file to the Disability Resource Center to have them assess its accessibility (send it far in advance of when you will need to use it).

- Save your PowerPoint presentation as a PDF file to distribute to students with visual impairments.

Preparing for the presentation

- Consider time and effort in preparing a PowerPoint presentation; give yourself plenty of lead time for design and development.

- PowerPoint is especially useful when providing course material online. Consider student technology compatibility with PowerPoint material put on the web; ensure images and graphics have been compressed for access by computers using dial-up connection.

PowerPoint is especially useful when providing course material online.

- Be aware of copyright law when displaying course materials, and properly cite source material. This is especially important when using visuals obtained from the internet or other sources. This also models proper citation for your students.

- Think about message interpretation for PowerPoint use online: will students be able to understand material in a PowerPoint presentation outside of the classroom? Will you need to provide notes and/or other material to help students understand complex information, data, or graphics?

- If you will be using your own laptop, make sure the classroom is equipped with the proper cables, drivers, and other means to display your presentation the way you have intended.

Slide content

- Avoid text-dense slides. It’s better to have more slides than trying to place too much text on one slide. Use brief points instead of long sentences or paragraphs and outline key points rather than transcribing your lecture. Use PowerPoint to cue and guide the presentation.

- Use the Notes feature to add content to your presentation that the audience will not see. You can access the Notes section for each slide by sliding the bottom of the slide window up to reveal the notes section or by clicking “View” and choosing “Notes Page” from the Presentation Views options.

- Relate PowerPoint material to course objectives to reinforce their purpose for students.

Number of slides

- As a rule of thumb, plan to show one slide per minute to account for discussion and time and for students to absorb the material.

- Reduce redundant or text-heavy sentences or bullets to ensure a more professional appearance.

- Incorporate active learning throughout the presentation to hold students’ interest and reinforce learning.

Emphasizing content

- Use italics, bold, and color for emphasizing content.

- Use of a light background (white, beige, yellow) with dark typeface or a dark background (blue, purple, brown) with a light typeface is easy to read in a large room.

- Avoid using too many colors or shifting colors too many times within the presentation, which can be distracting to students.

- Avoid using underlines for emphasis; underlining typically signifies hypertext in digital media.

Use of a light background with dark typeface or a dark background with a light typeface is easy to read in a large room.

- Limit the number of typeface styles to no more than two per slide. Try to keep typeface consistent throughout your presentation so it does not become a distraction.

- Avoid overly ornate or specialty fonts that may be harder for students to read. Stick to basic fonts so as not to distract students from the content.

- Ensure the typeface is large enough to read from anywhere in the room: titles and headings should be no less than 36-40-point font. The subtext should be no less than 32-point font.

Clip art and graphics

- Use clip art and graphics sparingly. Research shows that it’s best to use graphics only when they support the content. Irrelevant graphics and images have been proven to hinder student learning.

- Photographs can be used to add realism. Again, only use photographs that are relevant to the content and serve a pedagogical purpose. Images for decorative purposes are distracting.

- Size and place graphics appropriately on the slide—consider wrapping text around a graphic.

- Use two-dimensional pie and bar graphs rather than 3D styles which can interfere with the intended message.

Use clip art and graphics sparingly. Research shows that it’s best to use graphics only when they support the content.

Animation and sound

- Add motion, sound, or music only when necessary. When in doubt, do without.

- Avoid distracting animations and transitions. Excessive movement within or between slides can interfere with the message and students find them distracting. Avoid them or use only simple screen transitions.

Final check

- Check for spelling, correct word usage, flow of material, and overall appearance of the presentation.

- Colleagues can be helpful to check your presentation for accuracy and appeal. Note: Errors are more obvious when they are projected.

- Schedule at least one practice session to check for timing and flow.

- PowerPoint’s Slide Sorter View is especially helpful to check slides for proper sequencing as well as information gaps and redundancy. You can also use the preview pane on the left of the screen when you are editing the PowerPoint in “Normal” view.

- Prepare for plan “B” in case you have trouble with the technology in the classroom: how will you provide material located on your flash drive or computer? Have an alternate method of instruction ready (printing a copy of your PowerPoint with notes is one idea).

PowerPoint’s Slide Sorter View is especially helpful to check slides for proper sequencing and information gaps and redundancy.

PowerPoint Handouts

PowerPoint provides multiple options for print-based handouts that can be distributed at various points in the class.

Before class: students might like having materials available to help them prepare and formulate questions before the class period.

During class: you could distribute a handout with three slides and lines for notes to encourage students to take notes on the details of your lecture so they have notes alongside the slide material (and aren’t just taking notes on the slide content).

After class: some instructors wait to make the presentation available after the class period so that students concentrate on the presentation rather than reading ahead on the handout.

Never: Some instructors do not distribute the PowerPoint to students so that students don’t rely on access to the presentation and neglect to pay attention in class as a result.

- PowerPoint slides can be printed in the form of handouts—with one, two, three, four, six, or nine slides on a page—that can be given to students for reference during and after the presentation. The three-slides-per-page handout includes lined space to assist in note-taking.

- Notes Pages. Detailed notes can be printed and used during the presentation, or if they are notes intended for students, they can be distributed before the presentation.

- Outline View. PowerPoint presentations can be printed as an outline, which provides all the text from each slide. Outlines offer a welcome alternative to slide handouts and can be modified from the original presentation to provide more or less information than the projected presentation.

The Presentation

Alley, Schreiber, Ramsdell, and Muffo (2006) suggest that PowerPoint slide headline design “affects audience retention,” and they conclude that “succinct sentence headlines are more effective” in information recall than headlines of short phrases or single words (p. 233). In other words, create slide titles with as much information as is used for newspapers and journals to help students better understand the content of the slide.

- PowerPoint should provide key words, concepts, and images to enhance your presentation (but PowerPoint should not replace you as the presenter).

- Avoid reading from the slide—reading the material can be perceived as though you don’t know the material. If you must read the material, provide it in a handout instead of a projected PowerPoint slide.

- Avoid moving a laser pointer across the slide rapidly. If using a laser pointer, use one with a dot large enough to be seen from all areas of the room and move it slowly and intentionally.

Avoid reading from the slide—reading the material can be perceived as though you don’t know the material.

- Use a blank screen to allow students to reflect on what has just been discussed or to gain their attention (Press B for a black screen or W for a white screen while delivering your slide show; press these keys again to return to the live presentation). This pause can also be used for a break period or when transitioning to new content.

- Stand to one side of the screen and face the audience while presenting. Using Presenter View will display your slide notes to you on the computer monitor while projecting only the slides to students on the projector screen.

- Leave classroom lights on and turn off lights directly over the projection screen if possible. A completely dark or dim classroom will impede notetaking (and may encourage nap-taking).

- Learn to use PowerPoint efficiently and have a back-up plan in case of technical failure.

- Give yourself enough time to finish the presentation. Trying to rush through slides can give the impression of an unorganized presentation and may be difficult for students to follow or learn.

PART II: Enhancing Teaching and Learning with PowerPoint

Class preparation.

PowerPoint can be used to prepare lectures and presentations by helping instructors refine their material to salient points and content. Class lectures can be typed in outline format, which can then be refined as slides. Lecture notes can be printed as notes pages (notes pages: Printed pages that display author notes beneath the slide that the notes accompany.) and could also be given as handouts to accompany the presentation.

Multimodal Learning

Using PowerPoint can help you present information in multiple ways (a multimodal approach) through the projection of color, images, and video for the visual mode; sound and music for the auditory mode; text and writing prompts for the reading/writing mode; and interactive slides that ask students to do something, e.g. a group or class activity in which students practice concepts, for the kinesthetic mode (see Part III: Engaging Students with PowerPoint for more details). Providing information in multiple modalities helps improve comprehension and recall for all students.

Providing information in multiple modalities helps improve comprehension and recall for all students.

Type-on Live Slides

PowerPoint allows users to type directly during the slide show, which provides another form of interaction. These write-on slides can be used to project students’ comments and ideas for the entire class to see. When the presentation is over, the new material can be saved to the original file and posted electronically. This feature requires advanced preparation in the PowerPoint file while creating your presentation. For instructions on how to set up your type-on slide text box, visit this tutorial from AddictiveTips .

Write or Highlight on Slides

PowerPoint also allows users to use tools to highlight or write directly onto a presentation while it is live. When you are presenting your PowerPoint, move your cursor over the slide to reveal tools in the lower-left corner. One of the tools is a pen icon. Click this icon to choose either a laser pointer, pen, or highlighter. You can use your cursor for these options, or you can use the stylus for your smart podium computer monitor or touch-screen laptop monitor (if applicable).

Just-In-Time Course Material

You can make your PowerPoint slides, outline, and/or notes pages available online 24/7 through Blackboard, OneDrive, other websites. Students can review the material before class, bring printouts to class, and better prepare themselves for listening rather than taking a lot of notes during the class period. They can also come to class prepared with questions about the material so you can address their comprehension of the concepts.

PART III: Engaging Students with PowerPoint

The following techniques can be incorporated into PowerPoint presentations to increase interactivity and engagement between students and between students and the instructor. Each technique can be projected as a separate PowerPoint slide.

Running Slide Show as Students Arrive in the Classroom

This technique provides visual interest and can include a series of questions for students to answer as they sit waiting for class to begin. These questions could be on future texts or quizzes.

- Opening Question : project an opening question, e.g. “Take a moment to reflect on ___.”

- Think of what you know about ___.

- Turn to a partner and share your knowledge about ___.

- Share with the class what you have discussed with your partner.

- Focused Listing helps with recall of pertinent information, e.g. “list as many characteristics of ___, or write down as many words related to ___ as you can think of.”

- Brainstorming stretches the mind and promotes deep thinking and recall of prior knowledge, e.g. “What do you know about ___? Start with your clearest thoughts and then move on to those what are kind of ‘out there.’”

- Questions : ask students if they have any questions roughly every 15 minutes. This technique provides time for students to reflect and is also a good time for a scheduled break or for the instructor to interact with students.

- Note Check : ask students to “take a few minutes to compare notes with a partner,” or “…summarize the most important information,” or “…identify and clarify any sticking points,” etc.

- Questions and Answer Pairs : have students “take a minute to come with one question then see if you can stump your partner!”

- The Two-Minute Paper allows the instructor to check the class progress, e.g. “summarize the most important points of today’s lecture.” Have students submit the paper at the end of class.

- “If You Could Ask One Last Question—What Would It Be?” This technique allows for students to think more deeply about the topic and apply what they have learned in a question format.

- A Classroom Opinion Poll provides a sense of where students stand on certain topics, e.g. “do you believe in ___,” or “what are your thoughts on ___?”

- Muddiest Point allows anonymous feedback to inform the instructor if changes and or additions need to be made to the class, e.g. “What parts of today’s material still confuse you?”

- Most Useful Point can tell the instructor where the course is on track, e.g. “What is the most useful point in today’s material, and how can you illustrate its use in a practical setting?”

Positive Features of PowerPoint

- PowerPoint saves time and energy—once the presentation has been created, it is easy to update or modify for other courses.

- PowerPoint is portable and can be shared easily with students and colleagues.

- PowerPoint supports multimedia, such as video, audio, images, and

PowerPoint supports multimedia, such as video, audio, images, and animation.

Potential Drawbacks of PowerPoint

- PowerPoint could reduce the opportunity for classroom interaction by being the primary method of information dissemination or designed without built-in opportunities for interaction.

- PowerPoint could lead to information overload, especially with the inclusion of long sentences and paragraphs or lecture-heavy presentations with little opportunity for practical application or active learning.

- PowerPoint could “drive” the instruction and minimize the opportunity for spontaneity and creative teaching unless the instructor incorporates the potential for ingenuity into the presentation.

As with any technology, the way PowerPoint is used will determine its pedagogical effectiveness. By strategically using the points described above, PowerPoint can be used to enhance instruction and engage students.

Alley, M., Schreiber, M., Ramsdell, K., & Muffo, J. (2006). How the design of headlines in presentation slides affects audience retention. Technical Communication, 53 (2), 225-234. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43090718

University of Washington, Accessible Technology. (n.d.). Creating accessible presentations in Microsoft PowerPoint. Retrieved from https://www.washington.edu/accessibility/documents/powerpoint/

Selected Resources

Brill, F. (2016). PowerPoint for teachers: Creating interactive lessons. LinkedIn Learning . Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/PowerPoint-tutorials/PowerPoint-Teachers-Create-Interactive-Lessons/472427-2.html

Huston, S. (2011). Active learning with PowerPoint [PDF file]. DE Oracle @ UMUC . Retrieved from http://contentdm.umuc.edu/digital/api/collection/p16240coll5/id/78/download

Microsoft Office Support. (n.d.). Make your PowerPoint presentations accessible to people with disabilities. Retrieved from https://support.office.com/en-us/article/make-your-powerpoint-presentations-accessible-to-people-with-disabilities-6f7772b2-2f33-4bd2-8ca7-ae3b2b3ef25

Tufte, E. R. (2006). The cognitive style of PowerPoint: Pitching out corrupts within. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press LLC.

University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Medicine. (n.d.). Active Learning with a PowerPoint. Retrieved from https://www.unmc.edu/com/_documents/active-learning-ppt.pdf

University of Washington, Department of English. (n.d.). Teaching with PowerPoint. Retrieved from https://english.washington.edu/teaching/teaching-powerpoint

Vanderbilt University, Center for Teaching. (n.d.). Making better PowerPoint presentations. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/

Suggested citation

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2020). Teaching with PowerPoint. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide

Phone: 815-753-0595 Email: [email protected]

Connect with us on

Facebook page Twitter page YouTube page Instagram page LinkedIn page

Center for Teaching

Making better powerpoint presentations.

Print Version

Baddeley and Hitch’s model of working memory.

Research about student preferences for powerpoint, resources for making better powerpoint presentations, bibliography.

We have all experienced the pain of a bad PowerPoint presentation. And even though we promise ourselves never to make the same mistakes, we can still fall prey to common design pitfalls. The good news is that your PowerPoint presentation doesn’t have to be ordinary. By keeping in mind a few guidelines, your classroom presentations can stand above the crowd!

“It is easy to dismiss design – to relegate it to mere ornament, the prettifying of places and objects to disguise their banality. But that is a serious misunderstanding of what design is and why it matters.” Daniel Pink

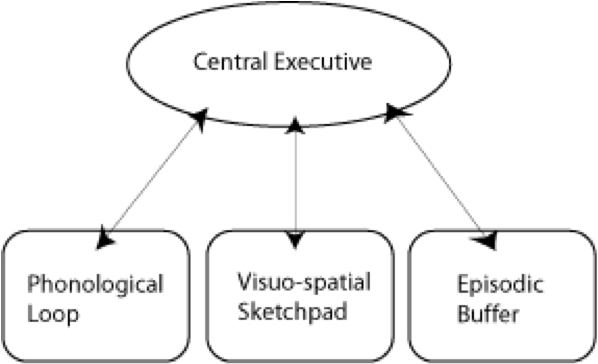

One framework that can be useful when making design decisions about your PowerPoint slide design is Baddeley and Hitch’s model of working memory .

As illustrated in the diagram above, the Central Executive coordinates the work of three systems by organizing the information we hear, see, and store into working memory.

The Phonological Loop deals with any auditory information. Students in a classroom are potentially listening to a variety of things: the instructor, questions from their peers, sound effects or audio from the PowerPoint presentation, and their own “inner voice.”

The Visuo-Spatial Sketchpad deals with information we see. This involves such aspects as form, color, size, space between objects, and their movement. For students this would include: the size and color of fonts, the relationship between images and text on the screen, the motion path of text animation and slide transitions, as well as any hand gestures, facial expressions, or classroom demonstrations made by the instructor.

The Episodic Buffer integrates the information across these sensory domains and communicates with long-term memory. All of these elements are being deposited into a holding tank called the “episodic buffer.” This buffer has a limited capacity and can become “overloaded” thereby, setting limits on how much information students can take in at once.

Laura Edelman and Kathleen Harring from Muhlenberg College , Allentown, Pennsylvania have developed an approach to PowerPoint design using Baddeley and Hitch’s model. During the course of their work, they conducted a survey of students at the college asking what they liked and didn’t like about their professor’s PowerPoint presentations. They discovered the following:

Characteristics students don’t like about professors’ PowerPoint slides

- Too many words on a slide

- Movement (slide transitions or word animations)

- Templates with too many colors

Characteristics students like like about professors’ PowerPoint slides

- Graphs increase understanding of content

- Bulleted lists help them organize ideas

- PowerPoint can help to structure lectures

- Verbal explanations of pictures/graphs help more than written clarifications

According to Edelman and Harring, some conclusions from the research at Muhlenberg are that students learn more when:

- material is presented in short phrases rather than full paragraphs.

- the professor talks about the information on the slide rather than having students read it on their own.

- relevant pictures are used. Irrelevant pictures decrease learning compared to PowerPoint slides with no picture

- they take notes (if the professor is not talking). But if the professor is lecturing, note-taking and listening decreased learning.

- they are given the PowerPoint slides before the class.

Advice from Edelman and Harring on leveraging the working memory with PowerPoint:

- Leverage the working memory by dividing the information between the visual and auditory modality. Doing this reduces the likelihood of one system becoming overloaded. For instance, spoken words with pictures are better than pictures with text, as integrating an image and narration takes less cognitive effort than integrating an image and text.

- Minimize the opportunity for distraction by removing any irrelevant material such as music, sound effects, animations, and background images.

- Use simple cues to direct learners to important points or content. Using text size, bolding, italics, or placing content in a highlighted or shaded text box is all that is required to convey the significance of key ideas in your presentation.

- Don’t put every word you intend to speak on your PowerPoint slide. Instead, keep information displayed in short chunks that are easily read and comprehended.

- One of the mostly widely accessed websites about PowerPoint design is Garr Reynolds’ blog, Presentation Zen . In his blog entry: “ What is Good PowerPoint Design? ” Reynolds explains how to keep the slide design simple, yet not simplistic, and includes a few slide examples that he has ‘made-over’ to demonstrate how to improve its readability and effectiveness. He also includes sample slides from his own presentation about PowerPoint slide design.

- Another presentation guru, David Paradi, author of “ The Visual Slide Revolution: Transforming Overloaded Text Slides into Persuasive Presentations ” maintains a video podcast series called “ Think Outside the Slide ” where he also demonstrates PowerPoint slide makeovers. Examples on this site are typically from the corporate perspective, but the process by which content decisions are made is still relevant for higher education. Paradi has also developed a five step method, called KWICK , that can be used as a simple guide when designing PowerPoint presentations.

- In the video clip below, Comedian Don McMillan talks about some of the common misuses of PowerPoint in his routine called “Life After Death by PowerPoint.”

- This article from The Chronicle of Higher Education highlights a blog moderated by Microsoft’s Doug Thomas that compiles practical PowerPoint advice gathered from presentation masters like Seth Godin , Guy Kawasaki , and Garr Reynolds .

Presenting to Win: The Art of Telling Your Story , by Jerry Weissman, Prentice Hall, 2006

Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery , by Garr Reynolds, New Riders Press, 2008

Solving the PowerPoint Predicament: using digital media for effective communication , by Tom Bunzel , Que, 2006

The Cognitive Style of Power Point , by Edward R. Tufte, Graphics Pr, 2003

The Visual Slide Revolution: Transforming Overloaded Text Slides into Persuasive Presentations , by Dave Paradi, Communications Skills Press, 2000

Why Most PowerPoint Presentations Suck: And How You Can Make Them Better , by Rick Altman, Harvest Books, 2007

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

COMMENTS

Learning objectives. In this module, you will: Describe the principles of flipped learning and how to implement them into the classroom. Explain how to create flipped lessons using PowerPoint Recorder. Build a flipped lesson to use with students.

the PowerPoint-Based Flipped Learning model in increasing students' understanding. The recent study is an experimental study with 115 participants divided into a class with a PBFL model, a class with a Flipped Learning model, and a class with a conventional model. The sampling technique used was

Overview. Use PowerPoint Recorder to flip instruction, provide content for students outside of class, and help improve student outcomes. Course Syllabus. You can prepare in instructor-led training or self-paced study. Learning paths or modules are not yet available for this. English (United States)

In this video we will explain how to use PowerPoint to create educational content for your students and use them for flipped classroom.#HPOnlineTeachingAssis...

Academy for Teaching and Learning. Moody Library, Suite 201. One Bear Place. Box 97189. Waco, TX 76798-7189. [email protected]. (254) 710-4064. A "flipped" classroom inverts the setting of traditional learning activities for the sake of efficiency and deeper learning (Flipped Learning Network, 2014). As pioneers Bergmann and Sams (2012) put it ...

Tools You Can Use To Create A Flipped Classroom. The principal study material in flipped classrooms comprises of video lectures, slideshows, audio lectures, screencast content, and engaging animation. Here are a few tools you can use to create this content. Tools For Screencasting. Educators use screencasting software to do a recording of their ...

The Flipped Classroom IS: A means to INCREASE interaction and personalized contact time between students and teachers. An environment where students take responsibility for their own learning. A classroom where the teacher is not the "sage on the stage", but the "guide on the side".

Perhaps the easiest way to create flipped videos for the flipped classroom. Using the application of Microsoft PowerPoint and little other required tools to ...

In this FLM, students are asked to complete a fill-in-the-blank outline which accompanies all three videos, covering the topics of designing visual presentations as well as presenting them. The completed outline will enhance the students' note-taking skills and will serve as a summary of the FLM that they may refer to in the future. Key Terms.

When using different versions of PowerPoint, the basic techniques are fundamentally the same, just the menu options tend to change a bit, with different icons and layouts. Voice Narration in PowerPoint 2013. The first technique covered above works the same basic way in PowerPoint 2013 as it does for PowerPoint 2010.

Flipped learning is a pedagogical approach in which direct instruction moves from the group learning space to the individual learning space, and the resulting group space is transformed into a dynamic, interactive, learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter (Flipped ...

other immediately after the classroom was flipped with student teaching. The solid line shows student atte. e after and the dotted line before the new strategy was implemented. Along with the increased. attendance were the improved student performance and course evaluations. The class performance was improv.

The experts at the Center examine the advantages and challenges of using presentation software in the classroom, suggest approaches to take, and discuss in detail using PowerPoint for case studies, with clickers, as worksheets, for online (think flipped classes as well) teaching, the of use presenter view, and demonstrate best practices for ...

Here are the steps: For each slide, cut the main content (Ctrl + X), click in the Notes pane, and paste (Ctrl + V). (If the Notes pane doesn't show, click the NOTES button at the bottom of the PowerPoint window.) Now, design simple, visual slides that people can understand and remember. Use the slides for the main principles and conclusions.

Flipping the classroom is a pedagogical approach where students first explore new course content outside of class by viewing a pre-recorded lecture video or digital module, or completing a reading or preparatory assignment. In-class time is organized around student engagement, inquiry, and assessment, allowing students to grapple with, apply ...

Carl Wieman and colleagues have also published evidence that flipping the classroom can produce significant learning gains (Deslauriers et al., 2011). Wieman and colleagues compared two sections of a large-enrollment physics class. The classes were both taught via interactive lecture methods for the majority of the semester and showed no ...

Flipped learning is an increasingly popular pedagogy in secondary and higher education. Students in the flipped classroom view digitized or online lectures as pre-class homework, then spend in ...