- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

How to Do Action Research in Your Classroom

You are here

This article is available as a pdf. please see the link on the right..

21 Action Research Examples (In Education)

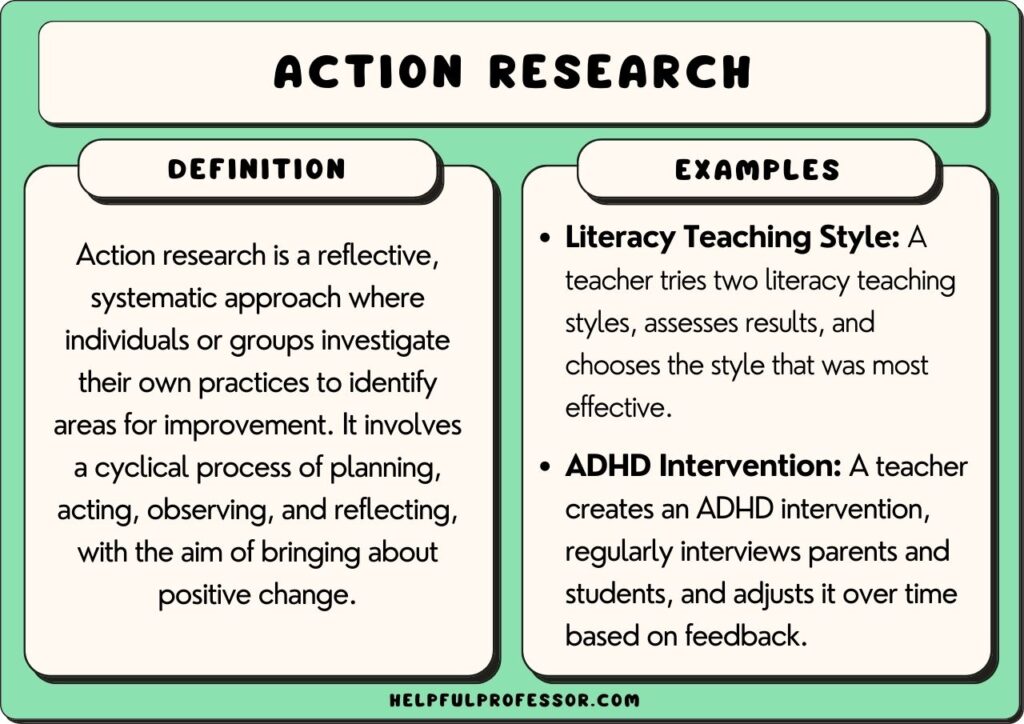

Action research is an example of qualitative research . It refers to a wide range of evaluative or investigative methods designed to analyze professional practices and take action for improvement.

Commonly used in education, those practices could be related to instructional methods, classroom practices, or school organizational matters.

The creation of action research is attributed to Kurt Lewin , a German-American psychologist also considered to be the father of social psychology.

Gillis and Jackson (2002) offer a very concise definition of action research: “systematic collection and analysis of data for the purpose of taking action and making change” (p.264).

The methods of action research in education include:

- conducting in-class observations

- taking field notes

- surveying or interviewing teachers, administrators, or parents

- using audio and video recordings.

The goal is to identify problematic issues, test possible solutions, or simply carry-out continuous improvement.

There are several steps in action research : identify a problem, design a plan to resolve, implement the plan, evaluate effectiveness, reflect on results, make necessary adjustment and repeat the process.

Action Research Examples

- Digital literacy assessment and training: The school’s IT department conducts a survey on students’ digital literacy skills. Based on the results, a tailored training program is designed for different age groups.

- Library resources utilization study: The school librarian tracks the frequency and type of books checked out by students. The data is then used to curate a more relevant collection and organize reading programs.

- Extracurricular activities and student well-being: A team of teachers and counselors assess the impact of extracurricular activities on student mental health through surveys and interviews. Adjustments are made based on findings.

- Parent-teacher communication channels: The school evaluates the effectiveness of current communication tools (e.g., newsletters, apps) between teachers and parents. Feedback is used to implement a more streamlined system.

- Homework load evaluation: Teachers across grade levels assess the amount and effectiveness of homework given. Adjustments are made to ensure a balance between academic rigor and student well-being.

- Classroom environment and learning: A group of teachers collaborates to study the impact of classroom layouts and decorations on student engagement and comprehension. Changes are made based on the findings.

- Student feedback on curriculum content: High school students are surveyed about the relevance and applicability of their current curriculum. The feedback is then used to make necessary curriculum adjustments.

- Teacher mentoring and support: New teachers are paired with experienced mentors. Both parties provide feedback on the effectiveness of the mentoring program, leading to continuous improvements.

- Assessment of school transportation: The school board evaluates the efficiency and safety of school buses through surveys with students and parents. Necessary changes are implemented based on the results.

- Cultural sensitivity training: After conducting a survey on students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences, the school organizes workshops for teachers to promote a more inclusive classroom environment.

- Environmental initiatives and student involvement: The school’s eco-club assesses the school’s carbon footprint and waste management. They then collaborate with the administration to implement greener practices and raise environmental awareness.

- Working with parents through research: A school’s admin staff conduct focus group sessions with parents to identify top concerns.Those concerns will then be addressed and another session conducted at the end of the school year.

- Peer teaching observations and improvements: Kindergarten teachers observe other teachers handling class transition techniques to share best practices.

- PTA surveys and resultant action: The PTA of a district conducts a survey of members regarding their satisfaction with remote learning classes.The results will be presented to the school board for further action.

- Recording and reflecting: A school administrator takes video recordings of playground behavior and then plays them for the teachers. The teachers work together to formulate a list of 10 playground safety guidelines.

- Pre/post testing of interventions: A school board conducts a district wide evaluation of a STEM program by conducting a pre/post-test of students’ skills in computer programming.

- Focus groups of practitioners : The professional development needs of teachers are determined from structured focus group sessions with teachers and admin.

- School lunch research and intervention: A nutrition expert is hired to evaluate and improve the quality of school lunches.

- School nurse systematic checklist and improvements: The school nurse implements a bathroom cleaning checklist to monitor cleanliness after the results of a recent teacher survey revealed several issues.

- Wearable technologies for pedagogical improvements; Students wear accelerometers attached to their hips to gain a baseline measure of physical activity.The results will identify if any issues exist.

- School counselor reflective practice : The school counselor conducts a student survey on antisocial behavior and then plans a series of workshops for both teachers and parents.

Detailed Examples

1. cooperation and leadership.

A science teacher has noticed that her 9 th grade students do not cooperate with each other when doing group projects. There is a lot of arguing and battles over whose ideas will be followed.

So, she decides to implement a simple action research project on the matter. First, she conducts a structured observation of the students’ behavior during meetings. She also has the students respond to a short questionnaire regarding their notions of leadership.

She then designs a two-week course on group dynamics and leadership styles. The course involves learning about leadership concepts and practices . In another element of the short course, students randomly select a leadership style and then engage in a role-play with other students.

At the end of the two weeks, she has the students work on a group project and conducts the same structured observation as before. She also gives the students a slightly different questionnaire on leadership as it relates to the group.

She plans to analyze the results and present the findings at a teachers’ meeting at the end of the term.

2. Professional Development Needs

Two high-school teachers have been selected to participate in a 1-year project in a third-world country. The project goal is to improve the classroom effectiveness of local teachers.

The two teachers arrive in the country and begin to plan their action research. First, they decide to conduct a survey of teachers in the nearby communities of the school they are assigned to.

The survey will assess their professional development needs by directly asking the teachers and administrators. After collecting the surveys, they analyze the results by grouping the teachers based on subject matter.

They discover that history and social science teachers would like professional development on integrating smartboards into classroom instruction. Math teachers would like to attend workshops on project-based learning, while chemistry teachers feel that they need equipment more than training.

The two teachers then get started on finding the necessary training experts for the workshops and applying for equipment grants for the science teachers.

3. Playground Accidents

The school nurse has noticed a lot of students coming in after having mild accidents on the playground. She’s not sure if this is just her perception or if there really is an unusual increase this year. So, she starts pulling data from the records over the last two years. She chooses the months carefully and only selects data from the first three months of each school year.

She creates a chart to make the data more easily understood. Sure enough, there seems to have been a dramatic increase in accidents this year compared to the same period of time from the previous two years.

She shows the data to the principal and teachers at the next meeting. They all agree that a field observation of the playground is needed.

Those observations reveal that the kids are not having accidents on the playground equipment as originally suspected. It turns out that the kids are tripping on the new sod that was installed over the summer.

They examine the sod and observe small gaps between the slabs. Each gap is approximately 1.5 inches wide and nearly two inches deep. The kids are tripping on this gap as they run.

They then discuss possible solutions.

4. Differentiated Learning

Trying to use the same content, methods, and processes for all students is a recipe for failure. This is why modifying each lesson to be flexible is highly recommended. Differentiated learning allows the teacher to adjust their teaching strategy based on all the different personalities and learning styles they see in their classroom.

Of course, differentiated learning should undergo the same rigorous assessment that all teaching techniques go through. So, a third-grade social science teacher asks his students to take a simple quiz on the industrial revolution. Then, he applies differentiated learning to the lesson.

By creating several different learning stations in his classroom, he gives his students a chance to learn about the industrial revolution in a way that captures their interests. The different stations contain: short videos, fact cards, PowerPoints, mini-chapters, and role-plays.

At the end of the lesson, students get to choose how they demonstrate their knowledge. They can take a test, construct a PPT, give an oral presentation, or conduct a simulated TV interview with different characters.

During this last phase of the lesson, the teacher is able to assess if they demonstrate the necessary knowledge and have achieved the defined learning outcomes. This analysis will allow him to make further adjustments to future lessons.

5. Healthy Habits Program

While looking at obesity rates of students, the school board of a large city is shocked by the dramatic increase in the weight of their students over the last five years. After consulting with three companies that specialize in student physical health, they offer the companies an opportunity to prove their value.

So, the board randomly assigns each company to a group of schools. Starting in the next academic year, each company will implement their healthy habits program in 5 middle schools.

Preliminary data is collected at each school at the beginning of the school year. Each and every student is weighed, their resting heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol are also measured.

After analyzing the data, it is found that the schools assigned to each of the three companies are relatively similar on all of these measures.

At the end of the year, data for students at each school will be collected again. A simple comparison of pre- and post-program measurements will be conducted. The company with the best outcomes will be selected to implement their program city-wide.

Action research is a great way to collect data on a specific issue, implement a change, and then evaluate the effects of that change. It is perhaps the most practical of all types of primary research .

Most likely, the results will be mixed. Some aspects of the change were effective, while other elements were not. That’s okay. This just means that additional modifications to the change plan need to be made, which is usually quite easy to do.

There are many methods that can be utilized, such as surveys, field observations , and program evaluations.

The beauty of action research is based in its utility and flexibility. Just about anyone in a school setting is capable of conducting action research and the information can be incredibly useful.

Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Gillis, A., & Jackson, W. (2002). Research Methods for Nurses: Methods and Interpretation . Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of SocialIssues, 2 (4), 34-46.

Macdonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13 , 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37 Mertler, C. A. (2008). Action Research: Teachers as Researchers in the Classroom . London: Sage.

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 11 Unconditioned Stimulus Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 10 Conditioned Stimulus Examples (With Pictures)

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 11 Unconditioned Stimulus Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 10 Conditioned Stimulus Examples (With Pictures)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

2 thoughts on “21 Action Research Examples (In Education)”

Where can I capture this article in a better user-friendly format, since I would like to provide it to my students in a Qualitative Methods course at the University of Prince Edward Island? It is a good article, however, it is visually disjointed in its current format. Thanks, Dr. Frank T. Lavandier

Hi Dr. Lavandier,

I’ve emailed you a word doc copy that you can use and edit with your class.

Best, Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Doing your own action research project

- December 14, 2021

Are children at your setting moving enough? Do they enjoy plenty of physically active outdoor play? The Newham Outdoors and Active practitioners spent eight months working through an action research project in order to identify the best ways to get their children moving and in touch with their own bodies. Here’s how you could do the same thing in your setting.

Action research is research that is undertaken as a response to a recognised area of need. It usually takes place in the workplace (eg your setting, or your home if you’re a childminder) and involves reflection, open ended questions and challenging your own existing practices.

Step 1: Where are we now?

The Outdoors and Active programme began with explorations into what was meant by the term physical development, and how it differs from physicality. These important documents and books and will help you form ideas about what high quality outdoor physicality should look like in your setting:

- Every Child A Mover by Jan White (Early Education, 2015) was a key text for us and is highly recommended as a guide to planning and making changes

- The Well Balanced Child by Sally Goddard Blythe (Hawthorn Press 2014).

- The British Heart Foundation guidance on physical activity for walkers and for non-walkers is essential reading.

- Exercising Muscles and Minds by Marjorie Ouvry (NCB 2003) provides an excellent overview of the connection between movement and cognition

The next action is to establish what is currently happening outdoors, so that you can identify gaps in provision. We did this using several audit tools :

- Jasmine Pasch’s BoingWhooshRolyPoly outdoor activity observation

- Play Learning Life’s Outdoor Play observation

- Learning through Landscapes’ EYFS Moving and Handling audit.

Each of these audits should be repeated at least three or four times, at different times of the day and in different weathers, in order to gain a complete picture of physical development opportunities as they currently stand.

Taking time with colleagues to analyse the outcomes of these surveys is important, not least to avoid travelling a pre-determined route in your action research. Challenging your own and others’ established practices, views and conventions is a key element of action research.

Step 2: Where do we want to be?

Drawing up a vision for physical development and physicality is the logical step, once a clear picture of current practice has been established. Take time to gather colleagues together; working towards a vision is almost impossible without the support and back up of everyone who’ll be affected by it. Share the outcomes of the initial auditing stage, considering any gaps in provision that have become apparent.

- What do you aspire to for children’s physical health and wellbeing?

- What should outdoor play look like at your setting?

- What do you want children to be able to do outdoors? Note – not what do you want them to have!

- How will you manage provision of physical risk and challenge?

- What might the barriers be to achieving your vision?

Create a short statement that encapsulates your shared aspirations for physicality and physical development outdoors. The statement should be clear and concise, but practical and achievable.

Step 3: How can we get there?

Once a vision statement has been agreed, it’s time to create an action research query that will guide your investigations outdoors.

- Your query shouldn’t be too broad (“How can we improve physicality outdoors?”) or too narrow.

- Whilst the beauty of action research is that you’re never going to be absolutely certain about the outcome, you should couch the question in terms that suggest confidence in a positive outcome – “How will increasing access to outdoor play in all weathers improve the frequency of physical activity?”.

- Take care not to generate a query that could have a simple “yes” or “no” answer. So ask “In what ways can we help parents understand the importance of physically active play?” rather than “Can we support parents…?”.

- Choose an action research query that can be supported by evidence and data, so that once it’s complete, you can make a strong case for long-term change. Quantitative and qualitative data are both valid and important to capture.

An action plan will help you plot a route through the action research. It should set out:

- Your vision statement

- Your action research query

- Measuring success – how you’ll compare outcomes with your initial audit data

- Key collaborators

Short-term actions – what do you want to test/achieve in the next 6 weeks?

- List the steps you plan to take, building in regular time for reflection and tweaking of the project.

- What resources might you need? Where will you source them? What budget is there?

- Who will help? Who needs to know?

- What kind of enabling environment do you want to create? What sort of atmosphere will it have?

Medium term actions – after reflection, what can you do over the following 3 – 4 months?

As above, plus:

- How will you communicate progress with your key collaborators and other stakeholders? How will you seek feedback, and how will you incorporate it (where appropriate)?

- What are the management issues? What are the budgeting issues?

- Essential resources to push the research forward

- Resources you should plan to acquire in the next 6 months in order to sustain change

- Resources wish list – fundraising challenges, perhaps?

Step 4: Making the changes

At the end of your action research period, review progress. This is a crucial stage; be honest about what worked and what didn’t, and if possible, ask a colleague to work with you to pick out the interventions that need to be implemented permanently. Gather and present your evidence so that you can make the case for change, along with any requests for a budget allocation or changes in the way outdoors is organised or managed. Long term, sustainable change is only possible with whole setting buy-in, so keep colleagues fully informed during this important phase.

Step 5: Celebrate

Audit the provision of physically active play, using the same audit tools as step one. Celebrate the changes – share details with parents and colleagues; talk to children about how they have progressed throughout the action research project period, asking them what they can now do, what they enjoyed trying, what they’d like to do next and sharing photographs and video footage of their journey.

If you’ve made significant changes to the layout, features or resources of outdoors, consider celebrating with a grand relaunch, inviting everyone that helped, parents and local community members, and of course your local authority early years team!

Further reading

Physical development in early childhood.

Clare Devlin, Early Education Associate What aspects of physical development should we focus on within the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and other early years

Outdoor learning in the early years

by Kathryn Solly The benefits of outdoor learning in the early years have now been firmly recognised for both educators and young children’s learning and

Families’ access to nature project

The Families’ Access to Nature Project was undertaken by the Froebel Trust and Early Education between October 2021 and January 2022. Children, their parents, and

Risk: A Forest School Perspective

Guest blog by Sara Knight Why are opportunities for risk and adventure essential for normal development in the early years? Tim Gill (2007) identifies four

Going out to play and learn

Why go outside? Big movers Have you ever been in an open space with young children? The first thing they want to do is to

Outdoor play and learning – ideas, info and lots of links

When writing our January Early Years Teaching News, I tweeted a survey to ask if practitioners and leaders would like information about ICT or outside

Outdoors and Active

Outdoors and Active – an action research project commissioned by the London Borough of Newham – took practitioners from nurseries, schools, PVI settings and children’s

Busy modern lives are having a dramatic impact on the health and wellbeing of our youngest children. They play outdoors less, spend more time being

Top tips for physicality in the park

Little or no equipment is needed to get children active in the park – not even the play equipment that’s probably already there! If there is play

Top tips for everyday physicality

Even everyday journeys and mundane chores can be used to encourage children to be more physically active. Here are some ideas, suggested by the Outdoors

Boing! Whoosh! RolyPoly!

Toddlers need plenty of balance practice once they are up and walking. Each of the three semi-circular canals in the inner ear respond to movement in different

Overcoming barriers

An early task for the Outdoors and Active action researchers was to identify the barriers to taking children out and about beyond the setting. Only

Taking risks in play

Human beings are “hardwired” to take risks, from birth. Babies take their first independent breaths; they decide to try crawling and walking and then running;

Loose parts for physicality

Traditional fixed play equipment is not necessary for physicality; if it’s there, then great – use it. Most of the Outdoors and Active project settings

Landscapes for physicality

Children can have fun and be active in any kind of landscape, but there’s no doubt that the more diverse and intriguing the space, the

Audit your environment

To audit the current provision for physical development outdoors in your school or setting, you can download our three sample audit sheets below. You should

Grab and Go Kits

Some of the childminders involved in the Outdoors and Active project thought that a kit of easy to carry, low cost resources could encourage children

Babies and toddlers outdoors

This content by Jan White comes from our out of print leaflet “The Sky is the Limit: Babies and Toddlers Outdoors: developing thinking, provision and practice”

Outside in all weathers, by Kathryn Solly

Healthy settling for high wellbeing How can we best help children feel at ease so that they are secure and settled in their new provision?

Become a member

For more articles and professional learning

Browse Early Education publications

- Add to basket

Birth to 5 Matters: non-statutory guidance for the EYFS

Enabling environments on a shoestring: a guide to developing and reviewing early years provision

Foundations of being: understanding young children's emotional, personal and social development

How children learn - The characteristics of effective early learning

I am two! Working effectively with two year olds and their families

The Educational Value of the Nursery School - 90th Anniversary edition

The great outdoors: Developing children's learning through outdoor provision

More than ICT: Information and communication technology in the early years

Supporting young children's sustained shared thinking - USB

Exploring young children's thinking through their self-chosen activities - USB

Young Children's Thinking - USB Combination Pack

Food to share recipe booklet

Centenary combination pack: Early childhood education + Food to share recipe booklet + The Educational Value of the Nursery School – 90th Anniversary edition

Early childhood education: current realities and future priorities

Combination pack: How children learn + I am two! + Foundations of Being + Enabling Environments

Become a member today, stay in the loop.

A registered charity in England and Wales (no. 313082) and in Scotland (no. SC039472) and a company limited by guarantee

Contact Information

Early Education 2 Victoria Square St Albans AL1 3TF

T: 01727 884925 E: [email protected]

- Action research: The benefits for early childhood educators

- This article introduces the purpose, process and benefits of engaging in action research in early childhood settings.

- Engaging in action research is an effective form of professional learning for educators.

- Action research is authentic because it allows educators to respond to issues of importance unique to their own settings.

- Educators have ownership over their action research projects, resulting in ‘transformative’ rather than ‘transmissive’ professional learning.

- Using action research in early childhood settings invites collaboration between educators, families and community.

- The focus of an action research project can be personalised to respond to educators’ interests and passions.

- The cycle of action research invites a sustained engagement in a particular aspect of educators’ work, providing many opportunities to question and reflect on the research topic.

Publication

Miller, M. (2017). Action research: The benefits for early childhood educators. Belonging: Early Years Journal , 6 (3) , pp. 26- 3 2 https://eprints.qut.edu.au/114335/

Action Research

← explore all resources.

Action research is a method used by teachers to solve everyday issues in the classroom. It is a reflective, democratic, and action-based approach to problem-solving or information-seeking in the classroom. Instead of waiting for a solution, action research empowers teachers to become critical and reflective thinkers and lifelong learners that are dedicated to helping improve student learning and teaching effectiveness.

Teachers or program leaders can take on an action research project by framing a question, carrying out an intervention or experiment, and reporting on the results. Below you’ll find resources, examples, and simple steps to help you get started.

Action Research in Early Childhood Education

Steps for action research.

1. Identify a Topic

Topics for action research can include the following:

- Changes in classroom practice

- Effects of program restructuring

- New understanding of students

- Teacher skills and competencies

- New professional relationships

- New content or curricula

- What problem do you want to solve? What information are you seeking?

- What data will need to be collected to help find a solution or answer?

- How will it be collected, by whom and from whom?

- How can you assure that your data will be reliable?

3. Collect Data

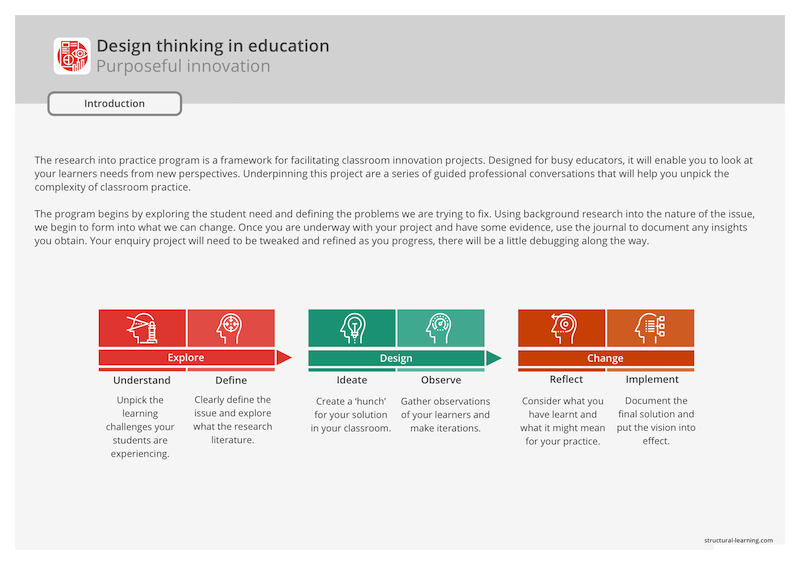

A mixed-method approach is a great way to ensure that your data is valid and reliable since you are gathering data from more than one source. This is called triangulation.

Mixed-methods research is when you integrate quantitative and qualitative research and analysis in a single study. Quantitative data is data that can be measured and written down with numbers. Some examples include attendance records, developmental screening tests, and attitude surveys. Qualitative data is data that cannot be measured in a numerical format. Some examples include observations, open-ended survey responses, audio recordings, focus groups, pictures, and in-depth interviews.

Ethically, even if your research will be contained in the classroom, it is important to get permission from the director or principal and parents. If your data collection involves videotaping or photographing students, you should review and follow school procedures. Always make sure that you have a secure place to store data and that you respect the confidentiality of your students.

4. Analyze and Interpret the Data

It’s important to consider when data will be able to answer your question. Were you looking for effects right away or effects that last until the end of the school year? When you’re done, review all of the data and look for themes. You can then separate the data into categories and analyze each group. Remember the goal of the analysis is not only to help answer the research question, but to gain understanding as a teacher.

5. Carry out an Action Plan to Improve Your Practice

After the analysis, summarize what you learned from the study.

- How can you share your findings?

- What new research questions did the study prompt you to research next?

- What actionable steps can you make as a result of the findings?

Pine, G. J. (2008). Teacher action research: building knowledge democracies. Sage Publications.

Related Content

Data design initiative, webinar: child assessments: telling stories with data, data basics, data literacy credential, data essentials.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

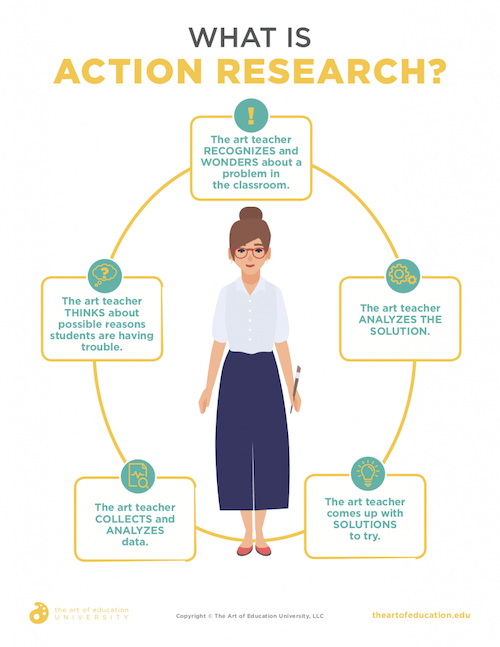

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

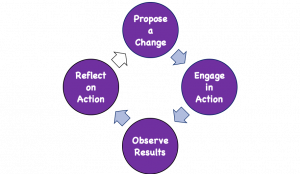

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

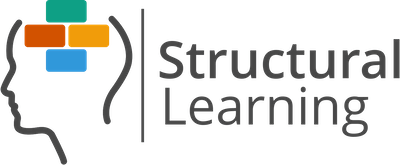

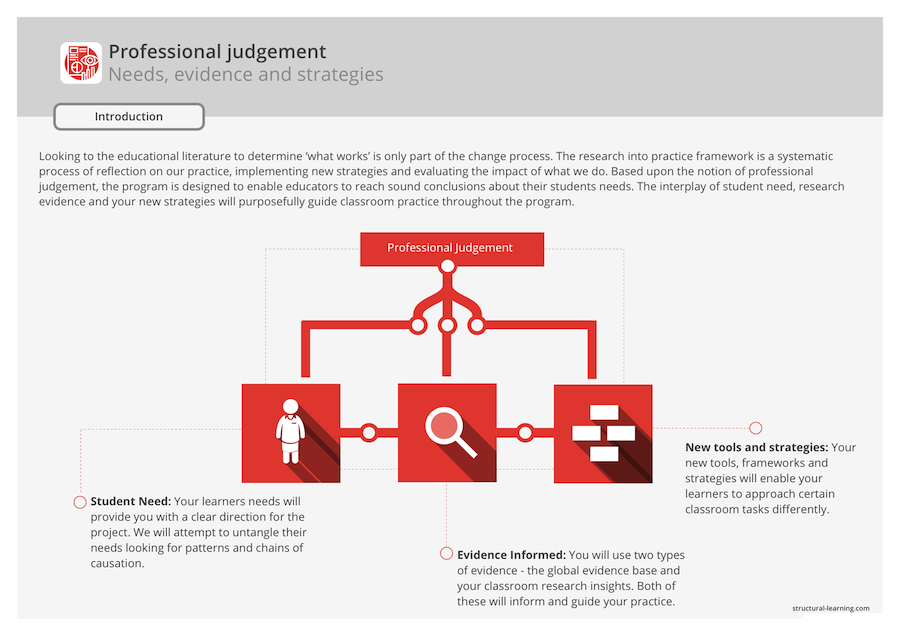

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

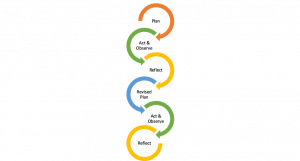

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

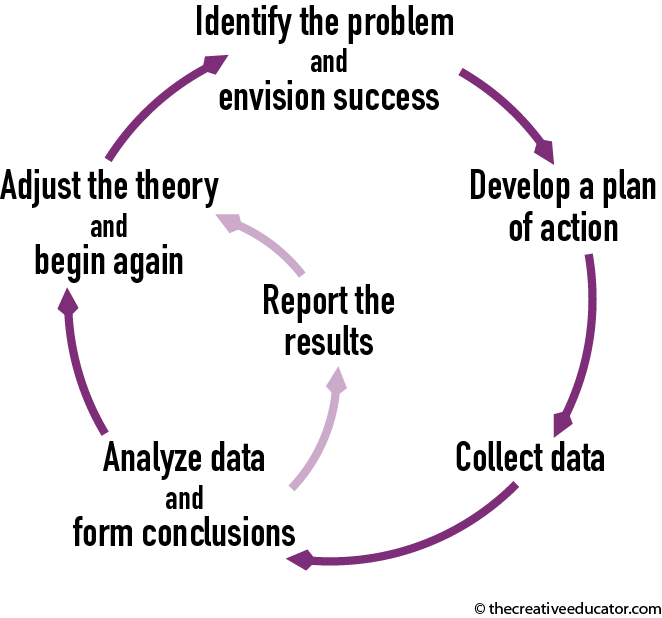

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.

Considering these two attributes, constructivism is distinct from conventional knowledge formation because people can develop a theory of knowledge that orders and organizes the world based on their experiences, instead of an objective or neutral reality. When individuals construct knowledge, there are interactions between an individual and their environment where communication, negotiation and meaning-making are collectively developing knowledge. For most educators, constructivism may be a natural inclination of their pedagogy. Action researchers have a similar relationship to constructivism because they are actively engaged in a process of constructing knowledge. However, their constructions may be more formal and based on the data they collect in the research process. Action researchers also are engaged in the meaning making process, making interpretations from their data. These aspects of the action research process situate them in the constructivist ideology. Just like constructivist educators, action researchers’ constructions of knowledge will be affected by their individual and professional ideas and values, as well as the ecological context in which they work (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). The relations between constructivist inquiry and action research is important, as Lincoln (2001, p. 130) states:

much of the epistemological, ontological, and axiological belief systems are the same or similar, and methodologically, constructivists and action researchers work in similar ways, relying on qualitative methods in face-to-face work, while buttressing information, data and background with quantitative method work when necessary or useful.

While there are many links between action research and educators in the classroom, constructivism offers the most familiar and practical threads to bind the beliefs of educators and action researchers.

Epistemology, Ontology, and Action Research

It is also important for educators to consider the philosophical stances related to action research to better situate it with their beliefs and reality. When researchers make decisions about the methodology they intend to use, they will consider their ontological and epistemological stances. It is vital that researchers clearly distinguish their philosophical stances and understand the implications of their stance in the research process, especially when collecting and analyzing their data. In what follows, we will discuss ontological and epistemological stances in relation to action research methodology.

Ontology, or the theory of being, is concerned with the claims or assumptions we make about ourselves within our social reality – what do we think exists, what does it look like, what entities are involved and how do these entities interact with each other (Blaikie, 2007). In relation to the discussion of constructivism, generally action researchers would consider their educational reality as socially constructed. Social construction of reality happens when individuals interact in a social system. Meaningful construction of concepts and representations of reality develop through an individual’s interpretations of others’ actions. These interpretations become agreed upon by members of a social system and become part of social fabric, reproduced as knowledge and beliefs to develop assumptions about reality. Researchers develop meaningful constructions based on their experiences and through communication. Educators as action researchers will be examining the socially constructed reality of schools. In the United States, many of our concepts, knowledge, and beliefs about schooling have been socially constructed over the last hundred years. For example, a group of teachers may look at why fewer female students enroll in upper-level science courses at their school. This question deals directly with the social construction of gender and specifically what careers females have been conditioned to pursue. We know this is a social construction in some school social systems because in other parts of the world, or even the United States, there are schools that have more females enrolled in upper level science courses than male students. Therefore, the educators conducting the research have to recognize the socially constructed reality of their school and consider this reality throughout the research process. Action researchers will use methods of data collection that support their ontological stance and clarify their theoretical stance throughout the research process.

Koshy (2010, p. 23-24) offers another example of addressing the ontological challenges in the classroom:

A teacher who was concerned with increasing her pupils’ motivation and enthusiasm for learning decided to introduce learning diaries which the children could take home. They were invited to record their reactions to the day’s lessons and what they had learnt. The teacher reported in her field diary that the learning diaries stimulated the children’s interest in her lessons, increased their capacity to learn, and generally improved their level of participation in lessons. The challenge for the teacher here is in the analysis and interpretation of the multiplicity of factors accompanying the use of diaries. The diaries were taken home so the entries may have been influenced by discussions with parents. Another possibility is that children felt the need to please their teacher. Another possible influence was that their increased motivation was as a result of the difference in style of teaching which included more discussions in the classroom based on the entries in the dairies.

Here you can see the challenge for the action researcher is working in a social context with multiple factors, values, and experiences that were outside of the teacher’s control. The teacher was only responsible for introducing the diaries as a new style of learning. The students’ engagement and interactions with this new style of learning were all based upon their socially constructed notions of learning inside and outside of the classroom. A researcher with a positivist ontological stance would not consider these factors, and instead might simply conclude that the dairies increased motivation and interest in the topic, as a result of introducing the diaries as a learning strategy.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, signifies a philosophical view of what counts as knowledge – it justifies what is possible to be known and what criteria distinguishes knowledge from beliefs (Blaikie, 1993). Positivist researchers, for example, consider knowledge to be certain and discovered through scientific processes. Action researchers collect data that is more subjective and examine personal experience, insights, and beliefs.

Action researchers utilize interpretation as a means for knowledge creation. Action researchers have many epistemologies to choose from as means of situating the types of knowledge they will generate by interpreting the data from their research. For example, Koro-Ljungberg et al., (2009) identified several common epistemologies in their article that examined epistemological awareness in qualitative educational research, such as: objectivism, subjectivism, constructionism, contextualism, social epistemology, feminist epistemology, idealism, naturalized epistemology, externalism, relativism, skepticism, and pluralism. All of these epistemological stances have implications for the research process, especially data collection and analysis. Please see the table on pages 689-90, linked below for a sketch of these potential implications:

Again, Koshy (2010, p. 24) provides an excellent example to illustrate the epistemological challenges within action research:

A teacher of 11-year-old children decided to carry out an action research project which involved a change in style in teaching mathematics. Instead of giving children mathematical tasks displaying the subject as abstract principles, she made links with other subjects which she believed would encourage children to see mathematics as a discipline that could improve their understanding of the environment and historic events. At the conclusion of the project, the teacher reported that applicable mathematics generated greater enthusiasm and understanding of the subject.

The educator/researcher engaged in action research-based inquiry to improve an aspect of her pedagogy. She generated knowledge that indicated she had improved her students’ understanding of mathematics by integrating it with other subjects – specifically in the social and ecological context of her classroom, school, and community. She valued constructivism and students generating their own understanding of mathematics based on related topics in other subjects. Action researchers working in a social context do not generate certain knowledge, but knowledge that emerges and can be observed and researched again, building upon their knowledge each time.

Researcher Positionality in Action Research

In this first chapter, we have discussed a lot about the role of experiences in sparking the research process in the classroom. Your experiences as an educator will shape how you approach action research in your classroom. Your experiences as a person in general will also shape how you create knowledge from your research process. In particular, your experiences will shape how you make meaning from your findings. It is important to be clear about your experiences when developing your methodology too. This is referred to as researcher positionality. Maher and Tetreault (1993, p. 118) define positionality as:

Gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities. Knowledge is valid when it includes an acknowledgment of the knower’s specific position in any context, because changing contextual and relational factors are crucial for defining identities and our knowledge in any given situation.

By presenting your positionality in the research process, you are signifying the type of socially constructed, and other types of, knowledge you will be using to make sense of the data. As Maher and Tetreault explain, this increases the trustworthiness of your conclusions about the data. This would not be possible with a positivist ontology. We will discuss positionality more in chapter 6, but we wanted to connect it to the overall theoretical underpinnings of action research.

Advantages of Engaging in Action Research in the Classroom

In the following chapters, we will discuss how action research takes shape in your classroom, and we wanted to briefly summarize the key advantages to action research methodology over other types of research methodology. As Koshy (2010, p. 25) notes, action research provides useful methodology for school and classroom research because:

Advantages of Action Research for the Classroom

- research can be set within a specific context or situation;

- researchers can be participants – they don’t have to be distant and detached from the situation;

- it involves continuous evaluation and modifications can be made easily as the project progresses;

- there are opportunities for theory to emerge from the research rather than always follow a previously formulated theory;

- the study can lead to open-ended outcomes;

- through action research, a researcher can bring a story to life.

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

38 Action research – how and why action research in ECE, Steps in action research

K. Srividya

1. INTRODUCTION:

There is many issues pertaining to early childhood, with regard to the schools, problems within the schools, teaching practices and the target group. There is a need to address these issues by the teachers, care takers, facilitators and other persons concerned in this field. Looking at the problems is just the start, but looking for reasonable solutions, within certain constrains matters a lot. To look in problems and come up with solutions one needs to follow an approach and that is called as action research.

Action research is a form of research or a study, that is carried out during the course of an action. ‘Action’ refers to an activity or an occupation, or a classroom transaction between teacher and students, employees involved in a project work and so on. Action research is carried out to improve the quality of life of the people involved in the research as well as the researcher. Action research helps change one thought processes, actions and gives new direction.

Action research is a process of systematic inquiry that seeks to improve social issues affecting the lives of everyday people (Bogdan & Bilken, 1992; Lewin, 1938; 1946; Stringer, 2008). Action research is found to be practiced by people in the field of education. Let’s learn in general about action research to get more understanding and then it’s importance in the field of Early Childhood Education.

2. LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- To understand action research and its process, and the steps to be followed to conduct action research.

- Understand the importance of action research.

- Helps the learner to apply action research in everyday classroom transactions with children belonging to early childhood years.

- Identifying problem areas, to improve the quality of teaching – learning approaches practiced in the classroom.

- HISTORY OF ACTION RESEARCH

Kurt Lewin, a social psychologist, was the first person to coin the term ‘action research’ during the 1940’s. Stephen Corey was the first person to use action research in the field of education. During it’s genesis, action research was not approved by the researchers and was termed as ‘unscientific’, because it can be used by common man for any purpose. But again in the 1970’s action research picked up momentum and practitioners started rationalising it applicability in the field of scientific research designs and methodologies.

Over the years, action research has been defined in many different ways, and has acquired new meanings.

- ACTION RESEARCH – A NEW MEANING

Action research is a systematic inquiry, whose aim is to answer questions of any practitioner of local concern which does not require any training.

Action research aims to contribute both to the practical concerns of people in an immediate problematic situation and to the goals of social science by joint collaboration within a mutually acceptable ethical framework. (Rapoport, 1970, p. 499)

A general term to refer to research methodologies and projects where the researcher(s) tries to directly improve the participating organization(s) and, at the same time, to generate scientific knowledge. (Kock, 1997)

EXERCISE 1: SELF CHECK QUESTIONS

- ______________ was the first person to coin the term action research. Ans: Kurt Lewin

- Action research can be used only in the field of education. True or False Ans: False

5.1 Identifying the problem – problems can be numerous, but it is very important to identify the pressing issue that needs to be addresses. Planning starts at this stage as soon as the problem has been identified.

5.2 Data collection – collecting the relevant data from various sources is an important factor to understand the problem identified by the researcher. Data can be collected in the form of interviews, observations, diaries, photos, videos, questionnaires.

5.3 Analysing the data collected – the data collected has to be categorised and analysed qualitatively or quantitatively .

5.4 Action plan – depending upon the analysis of data, the researcher will have plan the nature of intervention that needs to be given to address the problem identified through data collection.

5.5 Applying the action plan – once the action plan is finalised, it has to be applied to test the efficiency of the plan as well to observe any changes in the subjects involved in the action research process.

5.6 Analysis of the action plan – to test the efficiency of the action plan, data can be collected, analysed and evaluated.

5.7 Plan future action – evaluation of the action plan will help the researcher in knowing the efficiency of the action and will help define further actions that can be taken if needed.

6. VARIOUS MODELS OF ACTION RESEARCH

The steps followed in action research are all similar to the few models given below;

EXERCISE 2: SELF CHECK QUESTIONS

1.Write the correct sequence of steps in action research.

Data collection, analysing, identifying problem, future action plan, applying action plan.

Ans: Identifying problem, data collection, analysing, applying action plan and future action plan.

7. GIVEN BELOW IS AN EXAMPLE OF THE PROCESS OF ACTION RESEARCH IN A CLASROOM SETTING

7.1 Identifying the problem – A teacher finds that some children in her classroom are not able to follow instructions given by her for writing alphabets in spite of having been given learning experiences previously. So the first step has been taken in identifying the problem

7.2 Data collection – now the teacher will have to look in her teaching methods, and also try and find any commanalities in the particular group of children who are facing the problem. Get data from other teachers who are handing the classes, compare their data with yours. Collect the note books, any dairy entries and teaching methods followed. Also look for any developmental delays.

7.3 Analysing the data collected – once the data is ready, the teacher will be able to find the root cause of the problem, by making comparisions qualitatively or quantitatively.

7.4 Planning and applying the action plan – if for example the cause of the problem differences in teaching method, the teacher will have to make a plan to change her teaching method, and the change has to be implemented at a slow pace so that the other children will also not feel change. The plan has to be followed for a certain time duration to get results and it requires the patience of the teacher.

7.5 Analysis of the action plan – once the teacher feels that his/her action plan has brought in the desirable changes, the teacher will have to collect data to analyse the success of the action plan. This data can be again note books of children, periodic assessments, and also anecdotes from other teachers.

7.6 Plan for future action – from the analysis the teacher finds an improvement in the learning of the children, he/she can recommend the action to other teachers, share results and so on. The teacher can also improvise the action plan for any future purpose also.

8. WRITING ACTION RESEARCH REPORTS

It is very important to document all the research process, and so it is important to know the steps in writing an action research report which is similar to the methods used in other forms of research. Given below is a very generalised way of writing action report.

8.1 Introduction – an introduction which informs any person reaading the report about the topic of research choosed. The introduction define all the variables and also answer the reason for conducting the research.

8.2 Review of related literature – presenting releated research studies, articles will make the research strong as well acts as a support for the report. The research articles must be related to the problem defined by the investigator.

8.3 Methodology –aim, objectives and hypothesis of the study has to be defined. Terminologies used in the research process has to be defined. A detail description of the tools used to collect data for the study, the sample size and subjects taken up for the study, statistical analysis if applied.

8.4 Intervention – a detail description of how the action plan will be planned and executed by the researcher. The researcher can prepare modules, or use mapping technique, can use various art form methods to see the effects of the action plan.

8.5 Interpretation – the data collected has to be tabulated, graphs can be used as an extra source of analysis results and the results obtained has to discussed with supportive reseach studies.

8.6 Summary and conclusion – the report will be summarised and concluded, with recommendations for future research. Care has to be taken to put the references and appendix.

9. CHARACTERISTICS OF ACTION RESEARCH

- Focuses on the problem that needs to be addressed immediately and finding solutions as quickly as possible.

- Action research does not look at creating theories of making any general statements.

- Through action research one can improve one’s own practices, bring a change in the community as well in the work environment.

- Action research is not back breaking and needs very little resources and finances.

- Practicality of the purpose is given a lot of focus.

- There is no set rules to be followed, the researcher can set his/her own rules and frameworks.

- Action research is a collaborative and dynamic research involving a lot of action and sharing of results.

10. ADVANTAGES OF ACTION RESEARCH

- Anybody can use action research.

- Action research helps researchers, eucators get concere data, and not just rely on others preferences and doubts.

- Action research addresses both the quality of learning outcome gained as well as professional growth.

- A very beautiful aspect of action research research is that there action happening alomost immediately after the recognition of the problem and leads to change in the surrounding.

- At a classroom level, action research leads to developing lots of various teaching-learning techniques, which will encourage students and teachers to practice inquiry based teaching and learning.

11. DISADVANTAGES OF ACTION RESEARCH

- The findings of one researcher/educator cannot be generalised for everyone. The same issue can be overcome in a very different approach by another researcher/educator.

- Obstacles and delays maybe faced by the researcher/educator due to various reasons.

- There are various models avaliable, which can add to the confusion of the researcher/educator in choosing an appropriate model.

- Action research is prone to lot of bias.

12. METHODS OF APPLYING ACTION RESEARCH IN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

There are three ways of conducting action research in an educational set up as given by Ferrance (2000);

12.1 Individual teacher research –a single teacher takes charge of doing the research study. The statement of research problem, methods of data collection, analysis, action plan and evaluation depends on the single teacher. The outcomes of the research can be shared with other staff and can be used also.

12.2 Collaborative action research – a team of two or more investigators is formed. The team may include teachers, principal, other officials and so on. Tasks are divided amongst the team members after the research problem has been identified. The team will be meeting regularly to discuss the progress. The group follows the same process of data collection, analysis, action plan, evaluation and will share the outcomes of the research which can be made susceptible to future changes.

12.3 School wide action research – involves every person who is involved with the institution. This action research is usually a long term project with the aim of bringing in changes into the entire system of the institution. For example, if the school has to change the curriculum, the higher authorities of the school will have to identify issues with the current curriculum and bring in experts to suggest their opinions about different curriculum. Groups will be formed, who will work in the same level of collaborative action research. Care should be taken that, the action plan must be feasible for both teachers and the students. Once this issue is addressed, the results should be shared with all the members of the school. Once the action plan has been set and starts functioning, care should be taken to assess it periodically and give sufficient time for the whole school to reform on the changes.

EXERCISE 3: SELF CHECK QUESTIONS.

1. Anybody cannot do action research. True of False Ans: False

2. ___________ is a method where only one person is involved in the action research process.

Ans: Individual teacher research.

13. NEED FOR ACTION RESEARCH IN ECE

According to UNESCO, Early Childhood Care and Education is an integral part of basic education and represents the first and essential step in achieving the goals of Education-for-All. It is a very well known fact that early years are most crucial years of a child’s life. Therefore improving the quality of life of children by providing adequate nourishment, care, giving importance to the cognitive, social, psychological and emotional development has become a major concern for educators in the field of early childhood. Given below are few points where action research can help in the field of ECE;

- Access to early childhood care and education.

- Preparation for school readiness. Transitions are one of the most difficult phases the child passes through, which is very stressful and the child faces a lot of anxiety. To help children overcome this action research is a way to address.

- Improvement of early childhood curricula, programmes and policies.

- Bring about changes in the early childhood education training programmes.

- Application of theory into practice. There are many theoretical perspectives of learning which can be applied in classrooms for which can use action research to test best theories that can used in classrooms.

- To address delays in development. All children go through the same develomental process, but the rate of development is unique to every single child. If the teacher comes across any of these issues steps can be taken through action research the means to address these issues.

- To educate the imporance of play as a medium of learning and teaching children through art forms. Play are in many forms, every type of play gives a hands on learning experience to the children. Rhymes, stories, drammatisation, creative activities are also another froms of learning, through which the teacher can learn to innovate by using action research.

Action research is a matter of pressing demand in the field of education and cannot be taken for granted. It is very important to acknowledge the quality and quantity of work that goes into action research. One’s task is accomplised when the effects of the action research is visible in the classroom. It is very important on the part of educators who have used action research to enlighten their co-fellows about the importance practising action research in classroom. The early childhood years are also called as a vital and foundational years because of the vulnerablity of this age group. The education to children at this age is what stays throughout.