How to Build a Successful Research Team

researchdirector.io ·

In the world of research, a well-orchestrated team can make all the difference. This blog post will delve into the intricacies of building a successful research team. We will explore the steps, strategies, and considerations that can lead to a high-performing team, capable of producing groundbreaking research.

Understanding the Importance of a Research Team

A research team is the backbone of any research project. The team's composition, dynamics, and management significantly impact the project's success. A well-structured team can foster creativity, encourage innovation, and drive the project towards its goals.

In contrast, a poorly managed team can lead to delays, conflicts, and even failure. Therefore, understanding the importance of a research team and knowing how to build one is crucial. This section will explore the role of a research team, its importance, and the potential benefits of a well-structured team.

A research team brings together individuals with different skills, knowledge, and perspectives. This diversity can lead to innovative ideas and solutions that a single researcher may not conceive. Moreover, a team can share the workload, making the research process more efficient.

A well-structured team also fosters a supportive environment. Team members can motivate each other, provide feedback, and help overcome challenges. This camaraderie can make the research process more enjoyable and less stressful.

However, building such a team is not an easy task. It requires careful planning, thoughtful selection, and effective management. The following sections will provide a step-by-step guide on how to build a successful research team.

Assembling the Team

The first step in building a successful research team is assembling the team. This process involves identifying the skills and expertise needed for the project, finding suitable candidates, and selecting the best ones.

Start by identifying the skills and expertise needed for the project. Consider the project's objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. This analysis will help you determine the type of researchers you need.

Once you have identified the required skills and expertise, start looking for suitable candidates. You can find candidates through professional networks, academic institutions, job boards, and research communities. Consider candidates' qualifications, experience, skills, and potential contribution to the project.

After finding suitable candidates, select the best ones. Consider their compatibility with the project and the team. Also, consider their commitment, motivation, and work ethic. Remember, a team is not just about skills and expertise. It's also about compatibility, commitment, and collaboration.

Fostering Team Dynamics

After assembling the team, the next step is fostering team dynamics. This process involves promoting communication, collaboration, and cohesion among team members.

Promote communication by establishing clear and open channels of communication. Encourage team members to share their ideas, concerns, and feedback. This openness can lead to better understanding, trust, and cooperation among team members.

Promote collaboration by assigning tasks that require teamwork. Encourage team members to work together, share their knowledge, and help each other. This collaboration can lead to better results and a stronger team.

Promote cohesion by building a shared vision and goals. Encourage team members to contribute to the project's objectives and align their efforts towards these objectives. This cohesion can lead to a more focused and motivated team.

Managing the Team

Once you have fostered team dynamics, the next step is managing the team. This process involves guiding the team, resolving conflicts, and providing feedback and support.

Guide the team by setting clear expectations, providing direction, and monitoring progress. This guidance can help the team stay on track and achieve its goals.

Resolve conflicts by promoting open dialogue, understanding different perspectives, and finding common ground. This resolution can lead to a more harmonious and productive team.

Provide feedback and support by acknowledging good work, providing constructive criticism, and offering help when needed. This support can help team members improve their performance and feel valued.

Evaluating and Improving the Team

After managing the team, the next step is evaluating and improving the team. This process involves assessing the team's performance, identifying areas for improvement, and implementing changes.

Assess the team's performance by tracking progress, measuring results, and gathering feedback. This assessment can help you understand the team's strengths and weaknesses.

Identify areas for improvement by analyzing the assessment results, discussing with team members, and considering external feedback. This identification can help you find ways to enhance the team's performance.

Implement changes by adjusting strategies, providing training, and making necessary adjustments. This implementation can lead to a more effective and successful team.

Sustaining the Team

After improving the team, the final step is sustaining the team. This process involves maintaining team dynamics, managing changes, and continuously improving.

Maintain team dynamics by regularly promoting communication, collaboration, and cohesion. This maintenance can help the team stay strong and effective.

Manage changes by anticipating potential changes, preparing the team, and adapting strategies. This management can help the team navigate changes and stay focused.

Continuously improve by regularly evaluating the team, identifying areas for improvement, and implementing changes. This improvement can help the team stay successful and relevant.

Wrapping Up: Building and Sustaining a Successful Research Team

Building a successful research team is a complex process that requires careful planning, thoughtful selection, effective management, continuous improvement, and sustained effort. However, the benefits of a well-structured team - innovative ideas, efficient work, supportive environment, and successful outcomes - make it worth the effort. So, start building your winning research team today!

Manage My Research Team

Categories:

- Award Management

- Regulatory Compliance

There are many ways to go about building a research team—some more effective than others. If you are charged with or are interested in building a research team, there are several considerations to keep in mind:

Bring together members with diverse backgrounds and experiences to promote mutual learning.

Make sure each person understands his or her roles, responsibilities, and contributions to the team’s goals.

As a leader, establish expectations for working together; as a participant, understand your contribution to the end goal.

Recognize that discussing team goals openly and honestly will be a dynamic process and will evolve over time.

Be prepared for disagreements and even conflicts, especially in the early stages of team formation.

Agree on processes for sharing data, establishing and sharing credit, and managing authorship immediately and over the course of the project.

Regularly consider new scientific perspectives and ideas related to the research.

Source: Collaboration and Team Science: A Field Guide

The Field Guide discusses:

Team Science

Preparing Yourself for Team Science

Building a Research Team

Fostering Trust

Developing a Shared Vision

Communicating About Science

Sharing Recognition and Credit

Handling Conflict

Strengthening Team Dynamics

Navigating and Leveraging Networks and Systems

Created: 11.27.2020

Updated: 04.12.2021

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Leading your Research Team in Science

- > Introduction

Book contents

- Leading Your Research Team in Science

- Copyright page

- Introduction

- 2 Organization

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgments

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 November 2018

Who is this book for?

This book is for researchers who lead, or want to lead, their own team to carry out their research plans. It is also for staff who provide support to researchers to help make these plans come true: specialists in human resources, communication, information technologies, finance, knowledge transfer, legal affairs and contracts, learning and teaching, and any other issues important to the day-to-day and longer-term business of research. So what’s in it for you? I will outline what you can expect to find in this book here.

You’re a team leader or aspiring to become one. You’re passionate about science. Your dreams might lie in the exact sciences (biology, chemistry, mathematics, or physics) or in one of the other sciences (medical, behavioral, economic, historical, or social sciences). You’re convinced that your ideas will extend the frontiers of your research field. And you dream of having a successful team of dedicated people working with you. How do you make this come true? Today’s reality in academia is that it’s not enough to be an expert in a particular scientific area; you also need to be multitalented in a range of skills to get your daily academic “business” done. You need to have a nose for the best opportunities and antennas alert for serious threats. You need to be able to “sell” your plans well to attract the necessary funds. You need to recruit the right people and create a team that can work well together. You need to justify to the funding agency and the public why their investment in you is a wise one. You need to know when to protect an intellectual contribution before sharing it openly. There are many more “you need’s.” Here is a final one: you need to spend your allocated research time as much as possible on doing true research with your team. How can you ever achieve this? If there is an answer, then it could look like this: research is teamwork, and today’s teams are more than ever a union between talented scientific staff and talented support staff. Get to know what these support staff can offer you. Learn to understand their language, and help them to understand yours. Get them truly engaged in your work, and let them support, guide, advise, and educate you and contribute their share to the teamwork. And last but not least, include them in your research successes. Take the lead, become entrepreneurial: it is up to you to make your science a successful business. I trust that this book will trigger you to do just that extra bit, that the passion and performance of your team together will greatly exceed the sum of the individuals’ contributions.

You provide support services. Perhaps you work in a university support department. You have great colleagues, in-depth knowledge about processes and procedures in academia, and some basic understanding of what the scientists actually aim for in their research projects. But these scientists are so specialized and sometimes they’re rather odd characters too, so it may be a continual challenge to understand and support them. However, it’s worth investing time and effort to engage with them and understand a bit about their work. How do you convince them that your expertise can add value to their research business? That together you can make their science affairs work better, hopefully much better? Step into their shoes, figuratively. What is really meaningful to them? What will make them feel well supported? You’re an expert not in their field but in your own. Like them, know your environment: what do your peers in support departments at other universities offer? Take a look at the websites of top (and other) universities. Go to national and international meetings on research services, and offer to give oral or poster presentations on your experience. Read the literature – not only business books written in your language but also academic journals such as Nature, Science, Trends in … , Public Library of Science , or Chronicles of Higher Education . Such journals regularly publish articles about the business of science too. Let your science colleagues know that you are at the forefront of your field, and prove this to them. This aligns you with the scientists. Ultimately, why not consider publishing your department’s vision, stories, or best practices in those journals too? It may help to convince the scientists you support and your management that your ideas will make a difference. Now demonstrate your expertise, passion, and ambition to work with your organization’s scientists. Researchers need to trust that you do what you say you are going to do ( credibility ), do it when you say you’re going to do it ( reliability ), do it in a way that is sensitive for researchers’ characters ( intimacy ), do it to serve the interest of the research and researcher and not just your own ( orientation ), and do it well ( effectiveness and efficiency ). Footnote 1 By contributing to the work of successful scientists, their positive recommendations will raise your reputation and justify your role.

In the rest of this book, “you” refers to the ambitious scientist who wants to make science his or her business by building up an effective team of coworkers. If you are not a scientist but a support staff member, then every time you read “you,” it is an invitation to step into the shoes of an ambitious scientist.

How is this book structured?

This book has three chapters to help you do all of this and to do it well:

| describes how you can build up an effective team of Master’s and PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, and other staff, such as technicians. Join forces with staff from human resources to optimize your most important research resource: the people. | |

| describes the formal organization of your team: how to manage the finances, protect intellectual property, and negotiate legal contracts. Learn about the official rules, procedures, and processes of your institution. Join forces with staff in financial, legal, and human resource services, as well as in the knowledge transfer office. | |

| describes how to address your peers, the public, and other parties who want or need to know about your project and its results. Enhance the visibility and publicity of your work by allowing open access to information, by involving nonacademics in the work, and by using traditional and modern media to share outcomes. Join forces with staff from information technology, library services, and communication services. |

The three chapters and the various sections can be read sequentially or be dipped into ad hoc. Read and use the information in your own way. The “messages” in the sections are illustrated by anecdotes from starting, consolidating, and advanced researchers as well as from alumni who work outside academia: stories can speak louder than anything else. All these stories are presented in the first person, and some details have been changed to protect the privacy of the people who have shared their stories with me – but all the stories are based on true events. The messages in these sections have also been translated into various “TRY THIS ! ” exercises to help you sharpen your thoughts. You can do most of these exercises on your own, but you may benefit from interaction at a research group retreat, in an ad hoc peer discussion session you organize, or in a course for young team leaders.

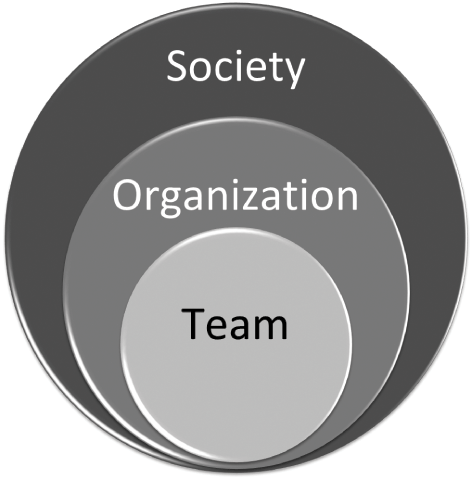

Figure Intro.1 The three parts of this book

The trilogy

This book is the third part of a triology for “early career researchers at work.” The first book, Developing a Talent for Science ( Reference Jansen 2011 ), discusses essential behaviors and skills. It offers guidelines on how to develop your own talent, how to use other people’s talent, and how to develop other people’s talent. The second book, Funding Your Career in Science ( Reference Jansen 2013 ) , discusses proposing projects and getting them funded . It offers guidelines on how to get novel research ideas and convert them into successful project proposals. This third book, Leading Your Research Team in Science (2019), completes the trilogy and discusses managing funded projects. It offers guidelines on how to deal successfully with all the associated responsibilities.

Disclaimers

This book offers an introduction to a range of issues in the domains of human resources, finance, and legal experts and others such as lawyers and patent specialists.

First disclaimer:

The information in this book does not aim to replace financial, legal, or any other professional advice. If you have questions, do contact a specialist, e.g., a human resources officer , project controller , or patent lawyer . How specific issues should be dealt with will differ between countries, between universities in the same country, and sometimes even between different institutes at the same university. Once you have read this book, however, you’ll have had a chance to think about such issues and be better equipped to handle such matters appropriately, knowing some of the general actions you need to take to make things happen.

Second disclaimer:

This book is not a scientific text. While reading it, try not to accept or reject anything right away; rather, taste, explore and consider, look up suggested further readings, and form your opinions later, as well as your own vision, strategy, and plans for your science business. Do it your way!

1 Modified from Maister et al. Reference Maister, Green and Galford 2000 .

Save book to Kindle

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Ritsert C. Jansen , Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands

- Book: Leading your Research Team in Science

- Online publication: 30 November 2018

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108601993.001

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

How to Lead a Research Team

- First Online: 01 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Aimee-Noelle Swanson 2

1276 Accesses

Leadership. Organizational culture. Managing dynamic teams. Providing effective feedback. Did you miss this course in your advanced training? Is this the class that you slept through only to show up for the final exam – or was that really just a dream? You didn’t, and it was only a dream. Being an intentional leader and building the culture you want to maximize workflow and employee satisfaction is not something that is taught in graduate school. Very few institutions provide a didactic to scientists on how you build an effective organizational structure to deliver the best science possible. In academia, you are taught to think critically; to be a careful, well-reasoned scientist and clinician; and to approach problems with an objective eye, determine the root cause, and create impactful solutions. You are not taught how to be an effective leader, how to hire the right staff, how to engage teams in work during stressful periods, how to provide effective feedback to enhance performance, and how to build trust in a diverse team. However, you do have all of the tools that you need to do all of these things. You’ve been doing them for years and have seen them all around you. Now it’s just a matter of recognizing them for what they are and connecting with them in a way that serves your goals and objectives. That is the point of this chapter. In this chapter we will cover building an intentional organizational culture, being a thoughtful leader, and managing a research team so that with some foresight and effort, you can focus on your science while engaging your staff in meaningful, high-impact work as a team.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Leading Change

Promoting Yourself into Leadership: Leading from Above, Beside, Below, and Outside

Working Open-Mindedly

Suggested reading.

These texts are valuable management and leadership tools for scientists. Consider these as key reference materials to set yourself up for success.

Google Scholar

Allen D. Getting things done: the art of stress-free productivity, revised edition. New York: Penguin Books; 2015.

Barker K. At the Helm: leading your laboratory. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2010.

Cohen CM, Cohen SL. Lab dynamics: management and leadership skills for scientists. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2012.

The Harvard Business Review (HRB). 10 Must Reads book series covers a wide range of topics with terrific resources and references.

Making the right moves: a practical guide to scientific management for postdocs and new faculty. 2nd ed. Burroughs Wellcome Fund and Howard Hughes Medical Institute; 2006. https://www.hhmi.org/developing-scientists/making-right-moves .

Patterson K, Grenny J, McMillan R, Switzler A. Crucial conversations: tools for talking when stakes are high. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2011.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Aimee-Noelle Swanson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Aimee-Noelle Swanson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Laura Weiss Roberts

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Swanson, AN. (2020). How to Lead a Research Team. In: Roberts, L. (eds) Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_34

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_34

Published : 01 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-31956-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-31957-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Advice for running a successful research team

- November 2015

- Nurse Researcher 23(2):36-40

- 23(2):36-40

- University of New England (Australia)

- Charles Sturt University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Binyam N. Desta

- Custodia Macuamule

- VigneshK Alamanda

- ChadA Krueger

- JosephR Hsu

- Haresh Raulgaonkar

- Helena Maguire

- Aly M. Fayed

- Carola F van Eck

- Zevia Schneider

- Bary Conchie

- Patricia Gosling

- Bart Noordam

- R. Meredith Belbin

- HARVARD BUS REV

- HEALTH SERV RES

- Lauren W Cohen

- Peter Kemper

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

8 Steps to Find the Best Research Collaborators

The pursuit of knowledge transcends borders and cultural boundaries, and research collaborators are increasingly coming together to make some incredible discoveries. A more globalized world creates more opportunities for academics to work together, pooling in their expertise, backgrounds, and strategies. In this article, we’ll outline the many advantages of collaborative research with tips to help you find and work with research collaborators.

Table of Contents

Benefits of collaborative research

Finding the right research collaborators and partnering with international counterparts can be a game-changer for your research. While working with research collaborators from different fields offers a blend of unique perspectives, it also allows access to specialized equipment, funding opportunities, and research facilities that would not otherwise be possible. This, in turn, results in a comprehensive, multidimensional, high-quality research study that can contribute significantly to addressing global challenges and create more meaningful impact. Collaborative research studies often have a better chance of publication in international journals, helping the research collaborators reach a wider group of readers across the world. Engaging with international research collaborators also fosters cross-cultural understanding, which goes a long way in helping you build a network of peers that you can tap for exciting research opportunities in the future.

Challenges in finding the right research collaborators

Despite the many benefits and growing collaborative research trends , finding the right partners or research collaborators can be a challenge. This rings especially true for early career researchers and individuals lacking an established network of peers and mentors. Overcoming language and cultural barriers can prove daunting, complicating the process further. Moreover, given the differences in the way research is conducted across the world, it is common to have misunderstandings, disagreements, and lapses in communication that could hamper progress. So, if you are looking for answers to how and where you can find international research collaborators, then continue reading.

How to find international research collaborators

- Define and specify your research objectives: Being clear about your research goals is a good way to start your search for international research collaborators who may share your vision. Consider your research question, methodology, and the kind of skills and support your project will require. This will help you to remain on track with your research work and will also make it simpler for you to communicate your needs and collaborate more effectively.

- Attend and participate in international seminars and conferences: Being a part of seminars, conferences, and academic forums are a great way to meet and interact with peers and researchers from around the world and learn about their work. Given that most academic and scientific events have networking sessions, you will find plenty of opportunities to learn about ongoing research in your field and connect with like-minded peers, who may be great potential research collaborators.

- Use online platforms and join professional research communities: Invest some extra effort by utilizing digital tools, online platforms like LinkedIn, and professional organizations and communities that provide access to a network of researchers from around the world. Consider reaching out to peers and colleagues at other institutions who are engaged in similar research to see if there are any chances of working together. You can identify potential collaboration opportunities by actively networking on both online and offline platforms and by joining professional groups.

- Find opportunities to collaborate on existing projects: If you are already working on a project, it can be a good idea to think about asking international colleagues to join you as research collaborators if you feel they can offer value. Seeking input on an existing project or offering assistance to others who may need help is a great way to build relationships that can lead to future research collaborations.

- Look for relevant research grants and funding opportunities: Many funding agencies today offer international research grants that require collaboration between researchers from different countries. Applying for these grants can provide you with an opportunity to work with international research collaborators and expand the reach of your research.

- Seek out researchers who have similar research interests: Review published articles and journals to identify and reach out to researchers. If their skills and research interests align with your project goals and needs, it may be a good idea to contact them directly via email or social media to inquire about the possibility of a collaboration. Remember to be clear not just about the work at hand but also about the potential benefits of collaboration for both parties.

- Be sensitive to cultural and geographic differences: It is imperative to ensure that there is no ambiguity when communicating with research collaborators. Find solutions to possible logistical and cultural barriers, such as language or differences in working styles and research methodologies. Consider time zone differences when scheduling meetings and discussions and be open to receiving inputs and feedback and be willing to commit to the project.

- Communicate and formalize goals and expectations: Once you have established contact, discuss expectations and goals for the research collaboration and formalize them through a written agreement that outlines the terms of the collaboration.

Finding the right research collaborator takes time and effort and can be challenging even for experienced researchers. Hopefully, the tips listed above will help you increase your chances of finding a research collaborator who shares your interests, skills, and goals, leading to better research outcomes.

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies top AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline a researcher’s journey, from reading to writing, submission, promotion and more. Based on over 20 years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success.

Try for free or sign up for the Researcher.Life All Access Pack , a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI academic writing assistant, literature reading app, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional services from Editage. Find the best AI tools a researcher needs, all in one place – Get All Access now at just $25 a month or $199 for a year !

Related Posts

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

Take Top AI Tools for Researchers for a Spin with the Editage All Access 7-Day Pass!

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Research Team Structure

- 4 minute read

- 100.1K views

Table of Contents

A scientific research team is a group of individuals, working to complete a research project successfully. When run well, the research team members work closely, and have clearly defined roles. Every team member should know their role, and how it plays into the project as a whole. Ultimately, the principal investigator is responsible for every aspect of the project.

In this article, we’ll review research team roles and responsibilities, and the typical structure of a scientific research team. If you are forming a research team, or are part of one, this information can help you ensure smooth operations and effective teamwork.

Team Members

A group of individuals working toward a common goal: that’s what a research team is all about. In this case, the shared goal between team members is the successful research, data analysis, publication and dissemination of meaningful findings. There are key roles that must be laid out BEFORE the project is started, and the “CEO” of the team, namely the Principal Investigator, must provide all the resources and training necessary for the team to successfully complete its mission.

Every research team is structured differently. However, there are five key roles in each scientific research team.

1. Principal Investigator (PI):

this is the person ultimately responsible for the research and overall project. Their role is to ensure that the team members have the information, resources and training they need to conduct the research. They are also the final decision maker on any issues related to the project. Some projects have more than one PI, so the designated individuals are known as Co-Principal Investigators.

PIs are also typically responsible for writing proposals and grant requests, and selecting the team members. They report to their employer, the funding organization, and other key stakeholders, including all legal as well as academic regulations. The final product of the research is the article, and the PI oversees the writing and publishing of articles to disseminate findings.

2. Project or Research Director:

This is the individual who is in charge of the day-to-day functions of the research project, including protocol for how research and data collection activities are completed. The Research Director works very closely with the Principal Investigator, and both (or all, if there are multiple PIs) report on the research.

Specifically, this individual designs all guidelines, refines and redirects any protocol as needed, acts as the manager of the team in regards to time and budget, and evaluates the progress of the project. The Research Director also makes sure that the project is in compliance with all guidelines, including federal and institutional review board regulations. They also usually assist the PI in writing the research articles related to the project, and report directly to the PI.

3. Project Coordinator or Research Associate:

This individual, or often multiple individuals, carry out the research and data collection, as directed by the Research Director and/or the Principal Investigator. But their role is to also evaluate and assess the project protocol, and suggest any changes that might be needed.

Project Coordinators or Research Associates also need to be monitoring any experiments regarding compliance with regulations and protocols, and they often help in reporting the research. They report to the Principal Investigator, Research Director, and sometimes the Statistician (see below).

4. Research Assistant:

This individual, or individuals, perform the day-to-day tasks of the project, including collecting data, maintaining equipment, ordering supplies, general clerical work, etc. Typically, the research assistant has the least amount of experience among the team members. Research Assistants usually report to the Research Associate/Project Coordinator, and sometimes the Statistician.

5. Statistician:

This is the individual who analyzes any data collected during the project. Sometimes they just analyze and report the data, and other times they are more involved in the organization and analysis of the research throughout the entire study. Their primary role is to make sure that the project produces reliable and valid data, and significant data via analysis methodology, sample size, etc. The Statistician reports both to the Principal Investigator and the Research Director.

Research teams may include people with different roles, such as clinical research specialists, interns, student researchers, lab technicians, grant administrators, and general administrative support staff. As mentioned, every role should be clearly defined by the team’s Principal Investigator. Obviously, the more complex the project, the more team members may be required. In such cases, it may be necessary to appoint several Principal Administrators and Research Directors to the research team.

Elsevier Author Services

At every stage of your project, Elsevier Author Services is here to help. Whether it’s translation services, done by an expert in your field, or document review, graphics and illustrations, and editing, you can count on us to get your manuscript ready for publishing. Get started today!

Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

Confidentiality and Data Protection in Research

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Latest Issue

- Practice Area Columns

- Comprehensive Internationalization

- Education Abroad

- International Enrollment Management

- International Students and Scholars

Five Tips to Build a Strong Research Team

Building a research team can seem like a daunting task. Bringing a group of people together who may not have collaborated before and who often represent different disciplines is a challenge that carries no assurance of success. However, with patience, proper preparation, and detailed expectations, a research team can emerge that will be productive for years.

“There’s not a magic recipe” for a successful research team, says Paul Whitney, associate vice president for international programs and director of the Health Equity Research Center at Washington State University. “But there are some common factors present in the species that thrive. If you have vegetable seeds to grow, you don’t just go out and throw them on bare ground. You prepare the bed. That’s how I think of building teams.” Determining those common factors and preparing for healthy growth doesn’t just happen. International educators with deep experience in team building identified five factors to keep in mind to put together a successful research team.

Find the right mix of talent.

“The most important thing for a really interdisciplinary team is that the people who come to the table have complementary skills around a similar talent,” says Whitney. “That really is the key to a research team taking off.”

While personalities make a difference, Whitney says that those dynamics are not as big a deal as many people think. “There are certainly people who play well with others and others who don’t,” he says. “I don’t think that accounts as much as people

Subscribe now to read full article

Already a NAFSA member or subscriber? Log in .

Job Seekers

Business Solutions

- Contractors

Meet the team

- CSR & Partnerships

Refer A Friend

How to Lead a Research Team in 4 Steps

Share Our Blog

Despite talent management in research being the greatest driver of research success , researchers are seldom taught how to lead a research team well.

In fact, research from the Wellcome Trust where over 4,000 scientists were surveyed, reveals that while 80% of lead researchers say they have the skills to manage a diverse team, less than half of research leaders have had any management training.

Successfully implementing talent management practices in a time-sensitive laboratory environment can be complex and remains a key area in need of improvement even for industry leaders in the scientific field.

However, when leaders do rise to the challenge, they can generate an environment of continual improvement, increased efficiency and greater satisfaction. In this article, I’ll outline 4 key steps, inspired by Psychologist Bruce Tuckman’s notorious theory of group development . Expect to find:

- 4 steps to successful leadership

- Research and insights on laboratory leadership

- Key skills information for research leaders

Four key steps to leadership success

Step 1 – form a vision and set your strategy.

While mission statements involve describing the purpose of your research itself, a vision statement should outline the project’s full trajectory while staying connected to the mission.

Your wider strategy and vision statement should include details around:

- Staff career plans – understanding your team’s ideal career trajectory will enable you to better share opportunities and responsibilities.

- Timelines for the project – clarifying clear timelines from the start can improve your chances of gaining additional funding.

- Communication channels – find reliable ways to maintain communication, ideally through weekly updates.

- Financial goals – aim for any additional funding opportunities from the project’s outset.

- Approach to work-life balance – understanding your team’s need for a work-life balance will help shape the trajectory of the project, and timelines, by setting realistic goals

- Development opportunities – describe any additional training and development opportunities that are available over the course of the project

- Enabling innovation – foster a creative environment from the outset, creating a psychologically safe environment where people can suggest new ideas.

- Building connections – collaboration can open up a wealth of opportunity and resource.

Vision statements should be a collaborative affair, where your team contribute their perspectives to shape a realistic and meaningful vision for the project.

A strong research vision describes the unique way a challenge will be addressed in context of its wider societal, environmental or even industrial impact.

Syngenta accomplish this with the vision statement below:

“Our vision is a bright future for smallholder farming. To strengthen smallholder farming and food systems, we catalyze market development and delivery of innovations, while building capacity across the public and private sectors” Leadership tip: While creativity is often regarded as key to research culture, 75% of researchers believe it’s being stalled. Overcoming this takes conscious action, and psychological safety. Google’s research shows that psychological safety is one of the greatest drivers for successful teamwork. Leaders can achieve a more innovative, and successful team culture by showing concern for wellbeing alongside success.

Step 2 – Bridge communication gaps and work through the challenges

Once you’ve successfully set up the vision and strategy behind your project, your attention can shift onto working through the challenges that arise and bridging any communication gaps that emerge. Your focus as a leader should be on promoting learning and providing the constructive feedback needed to help your team turn mistakes into lessons learned.

When faced with a hurdle, consider additional training where skills are insufficient, and stay committed even if the project isn’t going at the pace you expected.

Leadership tip: It’s also important to practice self-awareness and identify whether any research challenges could be down to your leadership style. If you don’t find your leadership style to be driving your team’s motivation, be prepared to change up your approach. Research shows you can do this by asking ‘what’ you can do to change, rather than focusing too much on ‘why’ your approach wasn’t successful.

Step 3 – Sustain performance

Now your project has overcome its growing pains, it’s likely that productivity has increased and that you’re looking for ways to keep that momentum going.

Emphasising project ownership and accountability is integral at this stage and can help sustain motivation and commitment to the research. As the research continues, it’s important to leverage communication channels, and keep conversations and ideas flowing – doing so, will better enable problem solving if further issues do arise.

Your responsibilities will largely shift at this point to monitoring:

- Time – the time it takes to complete projects, as well as the time the team are spending in the lab.

- Money – how finances are progressing, and whether further resourcing may be required.

- Quality of work – the quality of work should take a greater focus over the quantity of work, although both are important.

- Work-life balance – refer back to the vision for the project; is the same work-life balance being maintained?

- Burnout – monitor employee wellbeing and try to identify signs of employee burnout early.

Leadership tip: To maintain productivity, it’s important to move away from a competitive culture. 78% of researchers think that high levels of competition in the laboratory have created unkind, and aggressive conditions . Celebrate achievements and consider how you can help encourage team growth and development rather than focusing on a competitive environment.

Step 4 - Prepare for wrap-up

As the project draws to a close, your role as a leader should shift on to developing your team member’s career beyond the project. You can refer back to your project vision, as well as actively communicate with your wider team to ensure that every member is accessing the opportunities that they need to transition to their next research project and role.

You could organise a final event for the team to celebrate personal achievements alongside overall team achievements to close the project in a positive way.

Leadership tip: Establishing a successful offboarding process as a leader is crucial to maintaining a strong network with wider research teams, even after project completion.

Skills breakdown:

Key skills Research Managers require to achieve laboratory success are:

- Self-awareness

- Time management

- Accountability

Looking for resource support?

At Synergy , we provide specialist teams that boost laboratory capability, potential and efficiency from within. (www.srgtalent.com/clients/our-services/synergy-scientific-solutions)

Our links with SRG’s expansive talent networks mean we can source, manage and develop teams on behalf of our clients across the clinical and biotech industries.

Want to learn more? Get in touch with our team at: [email protected]

Latest News, Events & Insights

Working in Pharmaceutical Quality Assurance: Career Guidance

Discover the importance of quality assurance in pharma and what skills matter most with Behruz Sheikh, Pharmaceutical Sector Head

Why we need to embrace genetically modified food in the UK

Is public perception on genetically modified foods aligned with scientific reality? Find out more...

Why VCs are rushing to invest in medtech innovation

Find out why the medtech landscape will continue to abound with investment opportunities in 2021 and beyond — though with some minor caveats.

Why STEM Workplaces Need Inclusive Leadership Today

The need for inclusive leadership in STEM is heightening as discrimination and harassment challenge the sector. Find out more...

Why Money Doesn't Motivate Employees

Find out why money doesn't motivate employees and discover the best way to power employee motivation.

Why is Diverse Leadership in STEM Important?

Jacob Midwinter, Director of Sales and Search by SRG, discusses the key success factors behind driving diversity in leadership, as well as the challenges and opportunities leaders in STEM can expect to encounter along the way, with senior leaders Julia Buckler - QIAGEN, Dr. Amy Smith - CPI, Rich McLean - GPAS, Dr. Garry Pairaudeau - Exscientia, and Professor Charlotte Deane - Exscientia.

Why Eco-friendly, Sustainable Packaging is the Future of FMCG

Find out how FMCG organisations and the sector are large are fighting back against plastic waste and ushering in more a circular, sustainable economy.

What types of jobs are available in the petroleum engineering field?

Petroleum engineers are pivotal to the global economy. Involved in all stages of hydrocarbon extraction, development and production, they ensure that the end-to-end process is safe, efficient and cost-effective.

Want to Know More?

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Stay up to date with SRG

Latest Salary Survey

SRG are industry leaders and work with 3rd party vendors for market intelligence

Get in Touch

For Job Seekers

- Staffing Solutions

- Executive & Technical Search

- Managed Service Provider & Contingent Workforce Solutions

- Pre-Clinical Discovery Science

- Early Talent in STEM

- Recruitment Process Outsourcing and Permanent Workforce Solutions

- Statement of Work (SOW)

- Salary Benchmarking

- Meet the Team

- SRG Scotland

- News & Insights

- Guides & Reports

- Podcasts & Webinars

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Whistleblowing policy

- Accessibility

- Carbon Reduction Plan

- ED&I statement

- Gender Pay Gap Report

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Modern Slavery Statement

- Terms and conditions

- Complaints Procedure

© 2024 SRG.

- Gender pay gap report

11 common challenges you face as a researcher

As much as I love being a researcher, we experience some challenges when we try to lead research. Below I will share some of the common pain points other researchers, and I have faced within our roles.

.css-1nrevy2{position:relative;display:inline-block;} What are the problems faced by researchers during research?

1. research is slow and expensive.

As research as a separate team is relatively new compared to engineering, product, or design, many stakeholders may not have worked with researchers in the past and understand the value that a researcher can bring to the table.

Additionally, because some research methodologies take time to execute or require external vendor support to get the best insight, there are perceptions that research is slow or expensive and will be a barrier or blocker in building or shipping products.

These can lead to research not being included in product conversations early, or at all, limiting the ability for analysis to provide strategic or directional support.

In other cases it may lead to research not getting the right budget to effectively perform their work, leading to researchers having to be scrappy, hacky and de-prioritize research that may take up a significant percentage of their budget.

2. Research teams of one, or silos

When research is not valued, organizations will not invest in a group. Many organizations will have an individual researcher across the entire company or multiple product areas, which can strain the researcher to rigorously prioritize what projects they work on and lead to frustrations with other teams if they are not getting research support.

In cases where research teams exist, researchers may be embedded in discrete or separate product areas, making it hard for researchers to collaborate or pair with other researchers on projects. When researchers come together to attend crit or share feedback and experiences, researchers spend time setting the context of what they're working on with peers (especially in non-consumer facing experiences) to ensure peers can provide meaningful feedback to support their projects.

3. Research execution

Sometimes, after a researcher has spent the time and effort creating a robust research report, it isn't used. A research report is usually not used because of a mismatch in expectations of the stakeholder and researcher. Researchers need to ensure that stakeholders are taken along the research creation journey to ensure there is alignment and buy-in from stakeholders.

In some cases, researchers may "throw research over the fence" in that they may not invest the effort in creating research outputs that resonate with stakeholders or take the time to have conversations and presentations with stakeholders to open a dialogue about the research and help the stakeholder understand how to leverage the research

4. Research not used

In other cases, product priorities may have shifted, or new dependencies now prevent the research findings from being integrated into products and design. Inaction on research can make it harder for researchers to feel like they impact their team when their work doesn't create change in the product.

Researchers must determine other ways to generate value from the work that they have done. Value might be in the form of looking for broader opportunities to share findings outside of the direct stakeholder team or share with their research team, where outputs have the chance to be used for related work.

5. Too much effort to add and search for previous work

Researchers can spend a lot of time looking for past research or data to support a stakeholder or research project. Because researchers have to quickly jump from one project to another to ensure they can continually provide value, 'meta work' such as knowledge management is usually deprioritized in the research process.

Researchers may actively try to stay up to date with knowledge management activities. As each researcher may have a different mental model for how to tag and store insights, other researchers can find it difficult to find research unless they know the right search keywords.

Whatever the format a researcher presents in (such as a presentation or report), it will be the same format that it is stored. An inconsistent storage format can be hard for future researchers to parse for insights, leading researchers to have to go through every individual report on a topic to determine if there are relevant insights.

6. Service model requests

Although stakeholders are critical to ensuring the value of research is understood, some stakeholders may come to a researcher with an explicit research request (e.g. "I want to do usability testing on this feature"). This experience puts researchers into a 'service model' and prevents researchers from providing real strategic value and looking for opportunities that may be blind spots from stakeholders.

Preventing service model situations from happening requires researchers to build strong proactive relationships with their stakeholders, so researchers are on the pulse of potential research opportunities and teach them how to come with questions, not solutions, to researcher conversations.

7. Institutional knowledge inhibits new research

As many stakeholders may have domain or institutional knowledge about the area that they are working in, they may make assumptions about customers or products, leading them to drive product decisions on their own experiences.

Although stakeholders might have daily interactions with customers, they are not customers. Their underlying biases and assumptions based on their experience may not always align with actual customer pain points and needs. Researchers must figure out ways to tactfully push back on these decisions to ensure that research can provide guidance, or analysis, to ensure customer needs are clearly understood.

8. Insight of one

If stakeholders are customer-facing, or are part of customer conversations, they are likely to receive feedback on the stakeholders' product or experience. Customers may also 'solutionize' (i.e. provide suggestions on fixing the product) during these conversations. If a customer is high value, stakeholders are more likely to reactively decide to change or re-prioritize work based on the customer's insight or product suggestion.

A robust stakeholder perspective may be challenging for researchers when they are looking to propose work that may be on a similar topic, as a stakeholder may be adamant that the insight they captured as part of the customer conversation covers the need to conduct additional research.

9. More time in operations means less time to research

The responsibility of all organization and operational activities are then put on the researcher, leaving them less time to focus on ensuring high-quality research throughout the process.

Having a dedicated research operations resource also enables them to focus on other ways to improve operations in planning, to run, and synthesizing research that can provide longer-term efficiency gains for researchers.

10. Recruiting participants is high effort

A large part of a research operations' role is managing the participant recruitment process. If a research panel with customers who have proactively opted to participate in research is not available (either internally or through a vendor), alternative sources have to be used to identify potential participants.

Email open rates generally average 15-25% , so if there is a niche participant type, it's even more challenging to recruit enough of the relevant participants to match the required sample size.

There may also be situations where participant types are not digitally active (e.g. truck drivers), which means potential participants need to be called and manually scheduled individually.

Additionally, managing participants can take more effort: in most cases, confirmation calls are conducted with participants the day before a research session to minimize the potential of no-shows, and allows participants to reschedule.

11. Managing vendors through onboarding processes

Vendors support research in two key ways:

Recruitment & Logistics: Managing participants, including recruiting, scheduling, and incentive management. Vendors help when there is difficulty finding participant requirements, non-customers / users of a product or if the study is blinded. They may also rent out research labs for researchers to facilitate sessions if internal facilities are not available.

Research execution: Running full research projects, including planning, recruiting, execution, and synthesis. These are useful when there is a scoped project with little to no ambiguity (e.g. competitive review, usability testing).

In both cases, vendors need to go through procurement to agree on the work, cost, and expected outputs.

There are usually questionnaires related to security, privacy, and operational structures for larger or enterprise organizations that one or more internal teams may manage. In these cases, the researcher / research ops must become the middleman, working across both the internal teams and vendor to prevent timeline slippage of projects.

Procurement can become more complicated if organizations have stringent privacy or data protection processes, as there are strict requirements on what data sharing with external parties (e.g., personally identifiable information or PII off-limits).

If there is data that the researcher needs to recruit with and they are denied access because of company policy, it can lead to the researcher and vendor having to determine workarounds that may risk the quality of participants or research output.

Keep reading

.css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} Decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next

Decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Facility for Rare Isotope Beams

At michigan state university, investigating the conditions for a new stellar process.

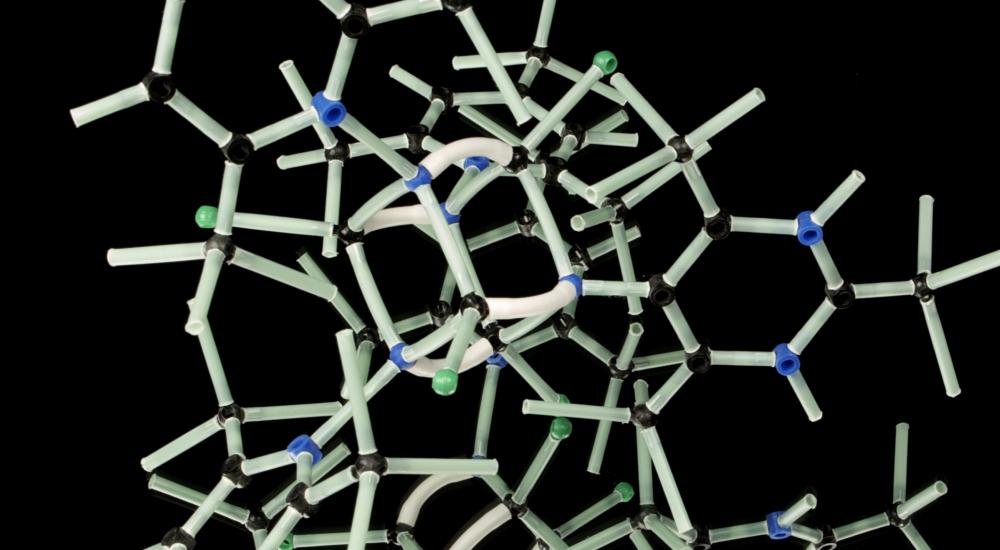

A scientific research team studied how the barium-139 nucleus captures neutrons in the stellar environment in an experiment at Argonne National Laboratory ’s (ANL) CARIBU facility using FRIB’s Summing Nal (SuN) detector . The team’s goal was to lessen uncertainties related to lanthanum production. Lanthanum is a rare earth element sensitive to intermediate neutron capture process (i process) conditions. Uncovering the conditions of the i process allows scientists to determine its required neutron density and reveal potential sites where it might occur. The team recently published its findings in Physical Review Letters (“First Study of the 139Ba(𝑛,𝛾)140Ba Reaction to Constrain the Conditions for the Astrophysical i Process”).

Artemis Spyrou , professor of physics at FRIB and in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Michigan State University (MSU), and Dennis Mücher , professor of physics at the University of Cologne in Germany, led the experiment. MSU is home to FRIB, the only accelerator-based U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE-SC) user facility on a university campus. FRIB is operated by MSU to support the mission of the DOE-SC Office of Nuclear Physics as one of 28 DOE-SC user facilities.

Combining global collaboration and world-class educational experiences

The experiment was a collaborative effort involving more than 30 scientists and students from around the world. Participating institutions included the University of Victoria in Canada, the University of Oslo in Norway, and the University of Jyväskyla in Finland.

“The collaboration is essential because everyone comes from different backgrounds with different areas of expertise,” Spyrou said. “Together, we’re much stronger. It’s really an intellectual sharing of that knowledge and bringing new ideas to the experiment.”

The international collaboration also included five FRIB graduate and two FRIB undergraduate students. FRIB is an educational resource for the next generation of science and technical talent. Students enrolled in nuclear physics at MSU can work with scientific researchers from around the world to conduct groundbreaking research in accelerator science, cryogenic engineering, and astrophysics.

“Our students contribute to every aspect of the experiment, from transporting the instrumentation to unpacking and setting it up, then testing and calibrating it to make sure everything works,” Spyrou said. “Then, we all work together to identify what’s in the beam. Is it reasonable? Do we accept it? Once everything is set up and ready, we all take shifts.”

Measuring the i process

Producing some of the heaviest elements found on Earth, like platinum and gold, requires stellar environments rich in neutrons. Inside stars, neutrons combine with an atomic nucleus to create a heavier nucleus. These nuclear reactions, called neutron capture processes, are what create these heavy elements. Two neutron capture processes are known to occur in stars: the rapid neutron capture process ( r process) and the slow neutron capture process ( s process). Yet, neither process can explain some astronomic observations, such as unusual abundance patterns found on very old stars. A new stellar process—the i process—may help. The i process represents neutron densities that fall between those of the r and s processes.

“Through this reaction we are constraining, we discovered that compared to what theory predicted, the amount of lanthanum is actually less,” said Spyrou.

Spyrou said that combining lanthanum with other elements, like barium and europium, helps provide a signature of the i process.

“It’s a new process, and we don’t know the conditions where the i process is happening. It’s all theoretical, so unless we constrain the nuclear physics, we will never find out,” Spyrou said. “This was the first strong constraint from the nuclear physics point of view that validates that yes, the i process should be making these elements under these conditions.”

Neutron capture processes are difficult to measure directly, Spyrou said. Indirect techniques, like the beta-Oslo and shape methods, help constrain neutron capture reaction rates in exotic nuclei . These two methods formed the basis of the barium-139 nucleus experiment.

To measure the data, beams provided by ANL’s CARIBU facility produced a high-intensity beam and delivered it to the center of the SuN detector, a device that measures gamma rays emitted from decaying isotope beams. This tool was pivotal in producing strong data constraints during the study.

“I developed SuN with my group at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, the predecessor to FRIB,” Spyrou said. “It’s a very efficient and large detector. Basically, every gamma ray that comes out, we can detect. This is an advantage compared to other detectors, which are smaller.”

The first i process constraint paves the way for more research

Studying the barium-139 neutron capture was only the first step in discovering the conditions of the i process. Mücher is starting a new program at the University of Cologne that aims to measure some significant i process reactions directly. Spyrou said that she and her FRIB team plan to continue studying the i process through different reactions that can help constrain the production of different elements or neutron densities. They recently conducted an experiment at ANL to study the neodymium-151 neutron capture. This neutron capture is the dominant reaction for europium production.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation.

Michigan State University operates the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) as a user facility for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE-SC), supporting the mission of the DOE-SC Office of Nuclear Physics. Hosting what is designed to be the most powerful heavy-ion accelerator, FRIB enables scientists to make discoveries about the properties of rare isotopes in order to better understand the physics of nuclei, nuclear astrophysics, fundamental interactions, and applications for society, including in medicine, homeland security, and industry.

The U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of today’s most pressing challenges. For more information, visit energy.gov/science .

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Do "research team" and "research group" mean the same thing?

I see some papers use "research team" while others use "research group". Do they mean the same thing, a few of researchers that form a team dedicated to a research?

- terminology

- The two terms seem to mean the same thing, unless an institution formally makes a distinction. – JRN Commented Apr 17, 2020 at 2:52

- 2 If they don't, it's certainly not universal enough to make an assumptions – Azor Ahai -him- Commented Apr 17, 2020 at 3:19

2 Answers 2

I would use “research group” to describe the set of people that is the students that I advise and any researchers I employ (plus myself).

“Research team” to me would be primarily the set of PIs with who I am collaborating on a given grant or other project, and may also encompass the students and researchers who are directly involved in that project.

“PI” here would be anyone in a principle investigator role for the project. This would certainly include professors and researchers at government labs/museums/zoos with whom I set up the project and secured funding, and could also include people who joined the project later under their own resources at our invitation, rather than being hired by one of the existing PIs out of the original funds. A postdoc coming in with their own funding, but with the funding contingent on their having a supervisor, would be in a grey area between the “PI-level” sense of “research team” and the broader sense of “PIs plus their students and staff”.

- Thanks for you answer. Does "PI" refer to principal investigator, the holder of an independent grant and the lead researcher for the grant project? – WXJ96163 Commented Apr 17, 2020 at 4:53

- Edited to expand my definition of PI. – RLH Commented Apr 17, 2020 at 6:32

Yes, they mean the same thing (or if they don't the difference is subtle enough that most people will not agree on what the difference is).

- I disagree that they mean the same thing — if I referred to people from research teams that I’m on as being “in my research group”, I would at least get funny looks from colleagues, and possibly hurt my standing in the community for being out of sync with accepted technical vocabulary. (This is not to dispute the fact that that the vocabulary might be community-dependent) – RLH Commented Apr 17, 2020 at 6:35

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged terminology ..

- Featured on Meta

- Upcoming sign-up experiments related to tags

Hot Network Questions

- Why can Ethernet NICs bridge to VirtualBox and most Wi-Fi NICs don't?

- Could space habitats have large transparent roofs?

- What does Athena mean by 'slaughtering his droves of sheep and cattle'?

- What is the function of the inductor in this Bluetooth audio module?

- Do capacitor packages make a difference in MLCCs?

- Weird behavior by car insurance - is this legit?

- Fantasy TV series with a male protagonist who uses a bow and arrows and has a hawk/falcon/eagle type bird companion

- DSP Puzzle: Advanced Signal Forensics

- Font shape warnings in LuaLaTeX but not XeLaTeX

- bug with beamer and lastpage?

- What is the meaning of '"It's nart'ral" in "Pollyanna" by Eleanor H. Porter?

- Clip data in GeoPandas to keep everything not in polygons

- What kind of sequence is between an arithmetic and a geometric sequence?

- Can I tell a MILP solver to prefer solutions with fewer fractions?

- Is there any other reason to stockpile minerals aside preparing for war?

- How do you say "living being" in Classical Latin?

- Reconstructing Euro results

- How to bid a very strong hand with values in only 2 suits?

- Next date in the future such that all 8 digits of MM/DD/YYYY are all different and the product of MM, DD and YY is equal to YYYY

- What to do if you disagree with a juror during master's thesis defense?

- Should I accept an offer of being a teacher assistant without pay?

- Is there a way to non-destructively test whether an Ethernet cable is pure copper or copper-clad aluminum (CCA)?

- Trying to determine what this small glass-enclosed item is

- How to make D&D easier for kids?

Researchers work to combat rise in syphilis cases

A team led by Dr. Arlene Seña is cataloging samples of syphilis patients to help fight the disease.

In the U.S., syphilis is at its highest rate since 1950, with a nearly 80% increase since 2018 , while babies born with syphilis have surged 937% in the past decade.

Symptoms of the sexually transmitted infection can include painless ulcers and sores that progress to body rashes on the palms and soles, hair loss, muscle pain and fatigue. Untreated, syphilis can cause blindness, deafness, paralysis and damage to the heart and brain.

Syphilis is easy to cure in the early stages with antibiotics like benzathine penicillin and doxycycline, said Dr. Arlene Seña , a researcher with the UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases. But better diagnostics and a vaccine are urgently needed.

“Despite many advances in infectious diseases, we’re still using serological tests developed in the early 1900s to determine infection and response to therapy,” she said. “We also need a syphilis vaccine that can effectively prevent infections in those at risk for infection.”

Seña is leading a $1.9 million National Institutes of Health contract to develop a specimen biorepository, collecting clinical data and different sample types to advance syphilis diagnostics from patients at domestic and international sites like UNC Project Malawi. She also led the clinical project for a multicenter NIH grant to collect specimens for genomic sequence analyses and to identify future vaccine candidates.

“These are critical steps in the development of a syphilis vaccine with global efficacy,” she said.

Persistence of syphilis

Seña says the persistent and chronic nature of syphilis — an infection that can hide from the immune system and affect other organ systems if not treated — is fascinating. She educates healthcare providers about syphilis throughout the U.S. and is a consultant for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s STI treatment guidelines on syphilis.

“Sir William Osler, the father of modern medicine, said that ‘those who understand syphilis understand medicine.’ This is a challenge for many clinicians that continues today,” she said.

Approximately 40% of babies born to women with untreated syphilis can be stillborn or die from the infection as a newborn. In 2012, there was only one case of congenital syphilis reported in North Carolina. In 2022, there were 55.

“Syphilis is one of the most difficult STIs to recognize and manage and can result in serious consequences in pregnant women if they are not screened properly,” Seña said.

Syphilis is caused by the Treponema pallidum bacterium, and research has been hindered because, until 2018, investigators were unable to successfully grow a long-lasting tissue culture of the bacterium . Testing is also complicated because the disease progresses into complex phases that can coexist with other STIs like genital herpes and HIV.

Currently, syphilis is diagnosed using a screening algorithm with serum antibody tests; however, these cannot reliably distinguish between current and past infections nor determine cure after antibiotics.

Those with an active UNC-Chapel Hill email can get a free July GoPass for GoTriangle bus routes.

UNC-Chapel Hill in top 5 of The Princeton Review’s best value colleges

Carolina is second among public universities for financial aid.

Carolina 7th in final Learfield Directors’ Cup standings

This is the Tar Heels' fifth-consecutive top-10 finish and their eighth top-10 effort in the past nine years.

Jessica Grant named interim director of Odum Institute

Grant will be the first woman to lead the institute in its 100-year history.

Eshelman ranked No. 1 in pharmacy research funding

The school earned the top spot from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy with more than $92 million in grants in FY23.

On-campus filming production will impact operations, traffic and parking July 5-12

Find information on road closures, parking changes and alterations to pedestrian routes.

Rhiannon Giddens connects history and music

The gifted musician reflects on her time as Carolina’s first Southern Futures Artist-in-Residence.

Pleiades are a flying disc dynasty

The Carolina women’s team won its fourth-straight national title in the sport also known as “ultimate Frisbee.”

Share on Mastodon

If we’re all so busy, why isn’t anything getting done?