Scientists discover potential cause of Alzheimer’s Disease

Existing drugs may offer effective prevention

Prevailing theories posit plaques in the brain cause Alzheimer’s disease. New UC Riverside research instead points to cells’ slowing ability to clean themselves as the likely cause of unhealthy brain buildup.

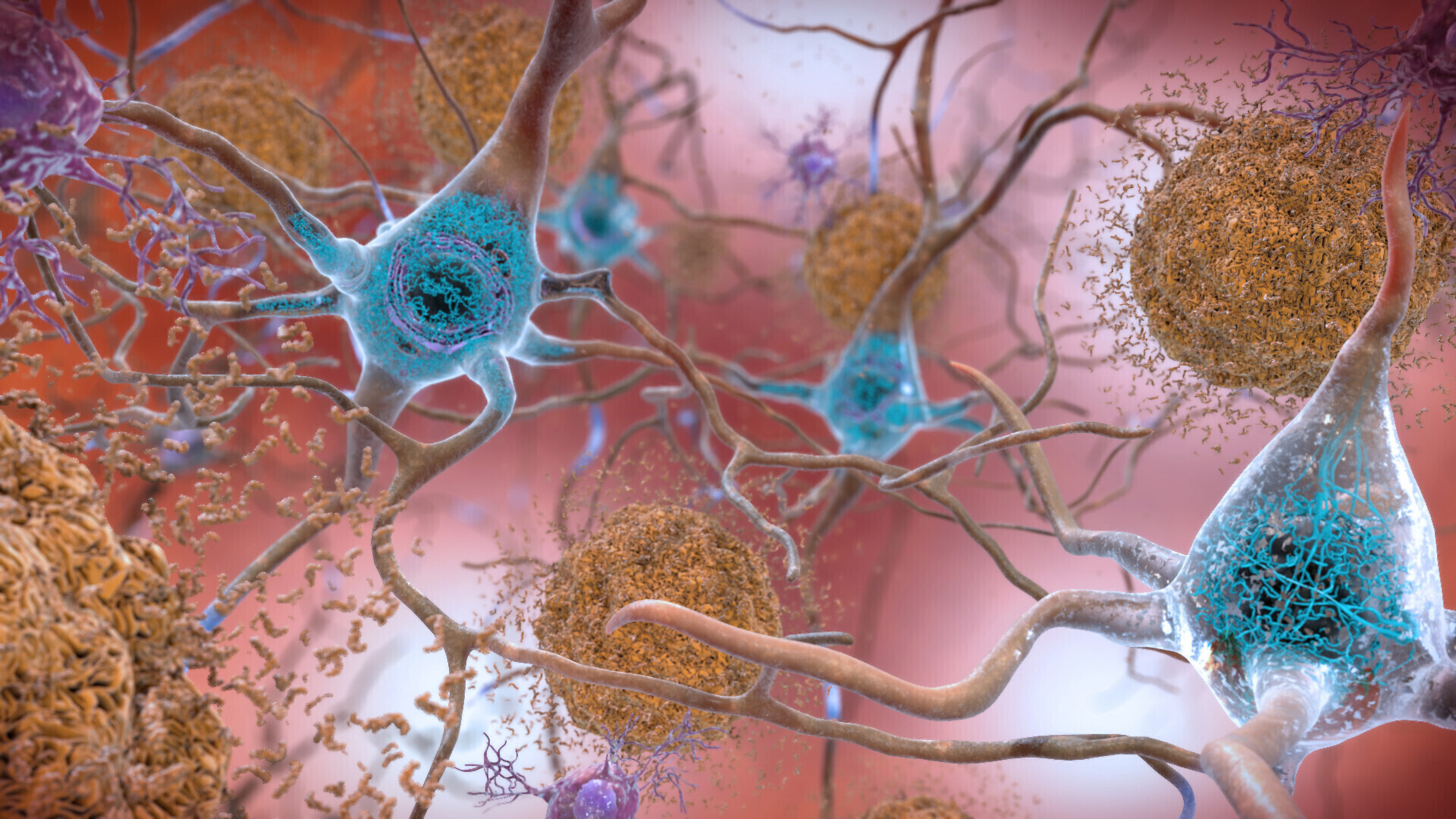

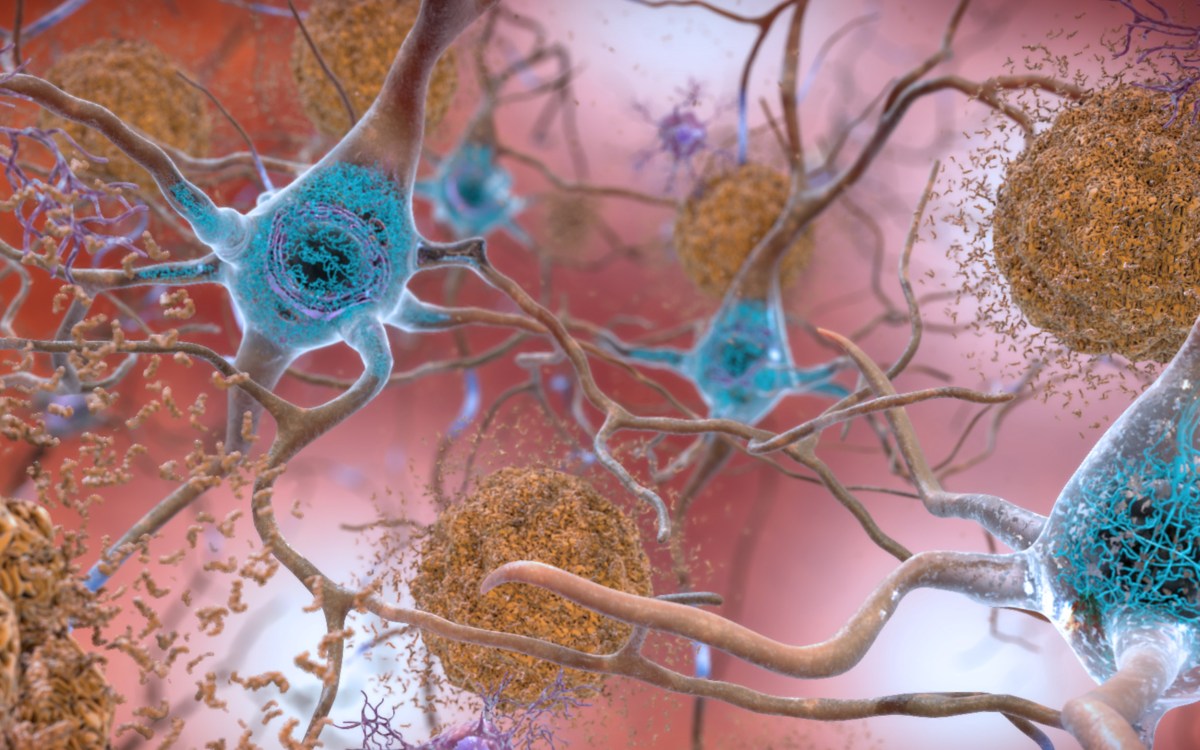

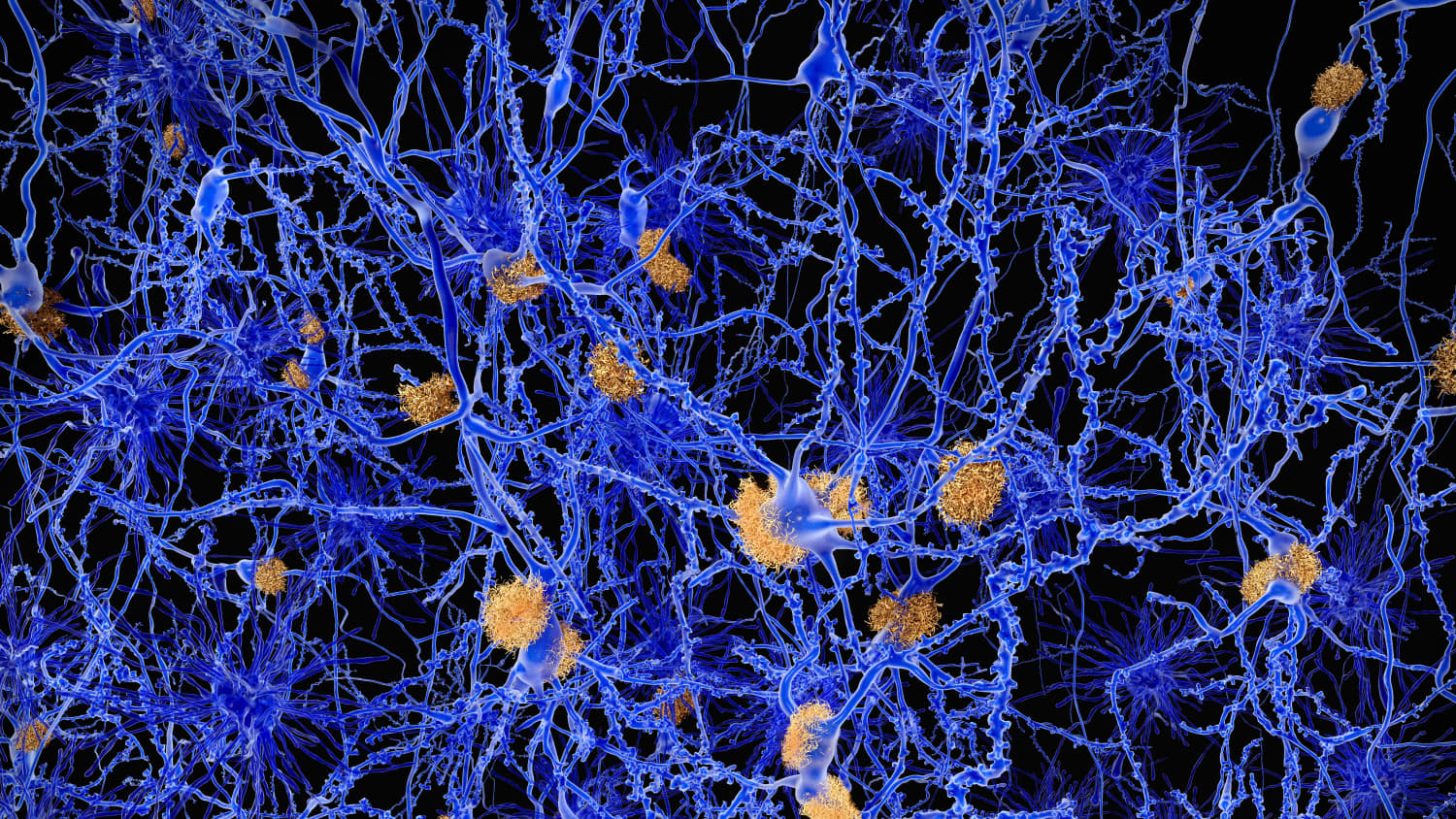

Along with signs of dementia, doctors make a definitive Alzheimer’s diagnosis if they find a combination of two things in the brain: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The plaques are a buildup of amyloid peptides, and the tangles are mostly made of a protein called tau.

“Roughly 20% of people have the plaques, but no signs of dementia,” said UCR Chemistry Professor Ryan Julian. “This makes it seem as though the plaques themselves are not the cause.”

For this reason, Julian and his colleagues investigated understudied aspects of tau protein. They wanted to understand whether a close examination of tau could reveal more about the mechanism behind the plaques and tangles.

A key but difficult-to-detect difference in the form of tau allowed the scientists to distinguish between people who expressed no outward signs of dementia from those who did. These results have now been published in the Journal of Proteome Research.

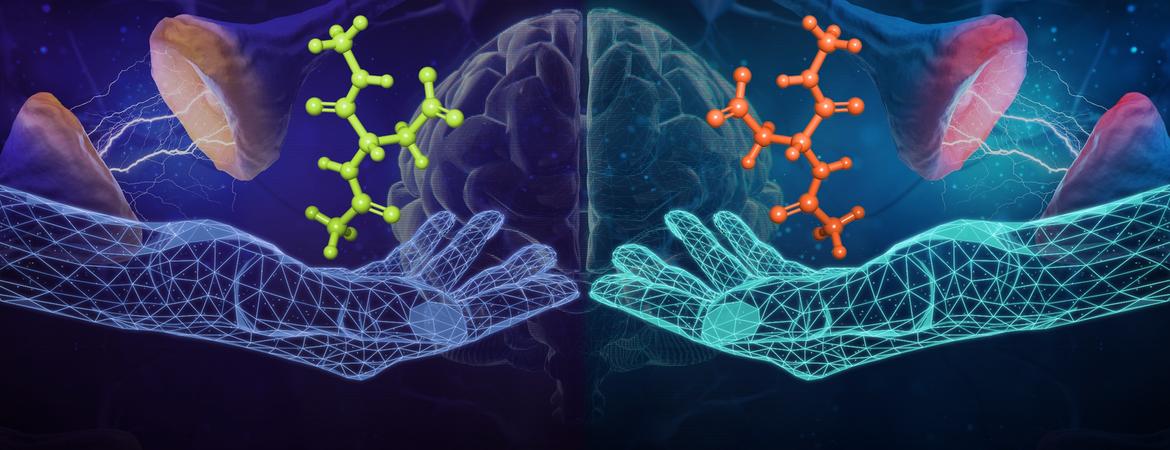

Julian’s lab focuses on the different forms that a single molecule can take, called isomers.

“An isomer is the same molecule with a different three-dimensional orientation than the original,” Julian said. “A common example would be hands. Hands are isomers of each other, mirror images but not exact copies. Isomers can actually have a handedness.”

The amino acids that make up proteins can either be right-handed or left-handed isomers. Normally, Julian said, proteins in living things are made from all left-handed amino acids.

For this project, the researchers scanned all the proteins in donated brain samples. Those with brain buildup but no dementia had normal tau while a different-handed form of tau was found in those who developed plaques or tangles as well as dementia.

Most proteins in the body have a half-life of less than 48 hours. However, if the protein hangs out too long, certain amino acids can convert into the other-handed isomer.

“If you try to put a right-handed glove on your left hand, it doesn’t work too well. It’s a similar problem in biology; molecules don’t work the way they’re supposed to after a while because a left-handed glove can actually convert into a right-handed glove that doesn’t fit,” Julian said.

In general, the process of clearing spent or defective proteins from cells, known as autophagy, slows down in people over the age of 65. It isn’t clear why, but Julian’s laboratory is planning to study this.

Fortunately, drugs are already being tested to improve autophagy. Some candidates include existing drugs approved for cardiovascular disease and other conditions, which may help speed up the approval process.

Autophagy can be induced by fasting. When cells run short on proteins from an individual’s diet, they fill the void by recycling proteins already present in cells. Exercise also increases autophagy.

These measures, as well as drug therapies, may ultimately help prevent the disease. “If a slowdown in autophagy is the underlying cause, things that increase it should have the beneficial, opposite effect,” Julian said.

Media Contacts

Related articles.

The fungus among us: California’s bats under siege

UCR awarded $1.5M for sustainable agriculture initiatives

Slowing ocean current could ease Arctic warming - a little

UC Riverside receives seven grants totaling $7M for graduate education

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Alzheimer's disease articles from across Nature Portfolio

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that impairs memory and cognitive judgment and is often accompanied by mood swings, disorientation and eventually delirium. It is the most common cause of dementia.

The Clinical Dementia Rating scale is useful but caution is needed

The Clinical Dementia Rating scale has been used in clinical research for decades. The Vargas-Gonzales study raises concerns about the subjective nature of the instrument by indicating that sex, the relationship of the informant to the participant, and the ethnicity of the participant can influence ratings, which is particularly relevant in an era of increasing inclusivity.

- Ronald C. Petersen

Latest Research and Reviews

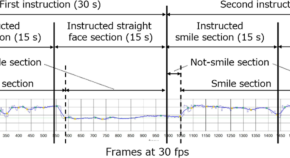

Digital detection of Alzheimer’s disease using smiles and conversations with a chatbot

- Haruka Takeshige-Amano

- Genko Oyama

- Nobutaka Hattori

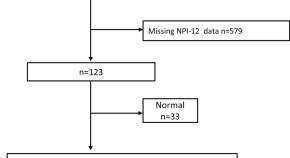

Behavioral and psychological symptoms and brain volumes in community-dwelling older persons from the Nakayama Study

- Ayumi Tachibana

- Jun-ichi Iga

- Shu-ichi Ueno

Using in vivo intact structure for system-wide quantitative analysis of changes in proteins

This study introduces an in vivo protein footprinting method, revealing structural changes in proteome during progressing AD. It demonstrates these changes occur before expression alterations, advancing understanding of protein misfolding mechanisms.

- Hyunsoo Kim

- John R. Yates

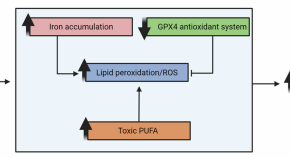

The link between amyloid β and ferroptosis pathway in Alzheimer’s disease progression

- Naďa Majerníková

- Alejandro Marmolejo-Garza

- Amalia M. Dolga

Informant characteristics influence Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes scores-based staging of Alzheimer’s disease

Vargas-Gonzalez et al. report an influence of informant characteristics on the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), a scale designed to stage patients with Alzheimer’s disease, which is commonly used as an outcome for clinical trials.

- Juan-Camilo Vargas-Gonzalez

- Antonella Santuccione Chadha

- Maria Carmela Tartaglia

Increased expression of the proapoptotic presenilin associated protein is involved in neuronal tangle formation in human brain

- Zhong-Ping Sun

- Qi-Lei Zhang

News and Comment

Reading the signs of dementia

Blood tests are leading to earlier diagnosis, and potentially treatments, for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

- Neil Savage

Lewy body pathology accelerates AD progression

- Heather Wood

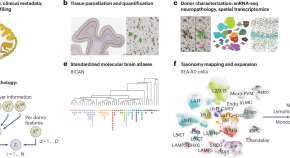

SEA-AD is a multimodal cellular atlas and resource for Alzheimer’s disease

The Seattle Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Cell Atlas (SEA-AD) is a multifaceted open-data resource that is designed to identify cellular and molecular pathologies that underlie Alzheimer’s disease. Integrating neuropathology, single-cell and spatial genomics, and longitudinal clinical metadata, SEA-AD is a unique resource for studying the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

- Michael Hawrylycz

- Eitan S. Kaplan

Francisco Lopera (1951–2024)

A trailblazing Latin American leader in Alzheimer’s disease research and a compassionate patient advocate

- Agustín Ibáñez

- Randall Bateman

- Hernando Santamaria-García

Life expectancy rise in rich countries slows down: why discovery took 30 years to prove

Improvements in public health and medicine have lengthened human survival, but science has yet to overcome ageing.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

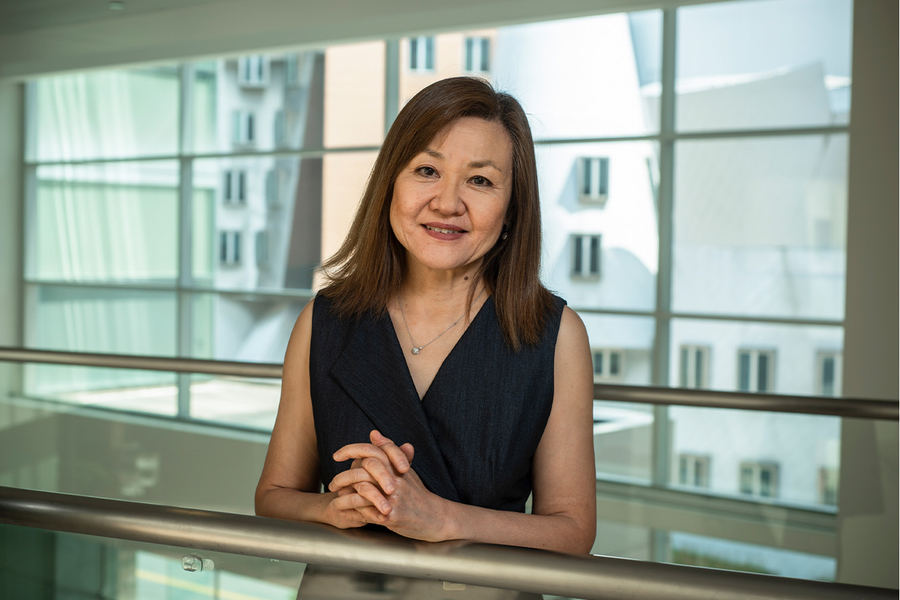

A new wave of treatment for Alzheimer’s disease

Previous image Next image

Alzheimer's disease, the appalling and baffling degenerative brain illness that plagues many elderly people, may be caused by several distinct mechanisms driven by various genetic and lifestyle factors, says Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience at MIT. To fully understand such conditions, she says, we must study the aging brain as a system rather than focusing on one or two types of ailing cells.

Neurodegenerative conditions take years to develop, partly because the brain is a highly plastic organ with many ways to adapt. “If there's one thing wrong, usually our nerve cells can figure out a way to continue to maintain the function of the brain,” Tsai says. “By the time someone shows any symptoms, the brain has already run out of any compensatory mechanism to mask the disruption. As you can imagine, this is a very systemic problem, with many things going wrong.”

Her work has led to a surprising approach to treat Alzheimer's, by increasing the strength of a certain frequency of our brainwaves. This noninvasive method has done well in early clinical trials carried out both by MIT and a startup firm co-founded by Tsai.

Director of The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, Tsai also spearheads the “miBrain” project to create integrated multicellular models of the human brain, with all the major types of brain cells within a network of blood vessels. The miBrain models seek to offer more realistic representations of brain tissue that will allow improved testing of drug candidates — and eventually support treatments that are personalized to each patient, identified in miBrains built from their own cells. (Patients can donate skin cells that can be re-engineered to become brain cells.) Tsai is welcoming potential commercial partners to join this ambitious effort.

Catching the gamma wave

The brain bundles together nerve cells, supporting cells such as astrocytes and microglia, and blood vessels. “In Alzheimer's disease, all of these cells are disrupted,” Tsai says. “So how do you simultaneously take care of all these different systems and different cells?” Her lab has long explored stimulation methods that can engage multiple regions and cell types across the brain.

Decades ago, researchers discovered that light presented at certain frequencies in mammals can elicit nerve cells in the brain to follow along in synch, creating or strengthening brainwaves.

Tsai and MIT neuroscientist Christopher Moore examined this phenomenon in mice with a cutting-edge lab technology called optogenetics (which was originally co-developed by MIT researchers Ed Boyden and Feng Zhang when they were at Stanford University). The collaborators successfully used optogenetics to increase the power of gamma waves in rodent brains.

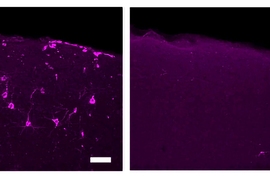

Tsai's former graduate student Hunter Iaccarino followed up to see if boosting gamma waves could produce meaningful effects in mice models of Alzheimer's disease. Working with Boyden and MIT Professor Emery Brown, Iaccarino discovered that enhancing 40-cycle-per-second gamma waves via flickering light stimulation could significantly reduce levels of the amyloid protein that is a lead indicator of Alzheimer's. The partners published these striking results in the journal Nature in 2016.

“We subsequently identified that using gamma sound stimulation also can engage nerve cells in the brain and force them to fire at the gamma frequency,” Tsai says.

The waves generated a surprising range of beneficial effects in animal models. Experiments also showed that the effect reaches key parts of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex, where we do planning and reasoning, and the hippocampus, where we make memories.

“Today, we go cell type by cell type, system by system, to comb through all of the possible mechanisms for this effect,” she says. “If we know how it works, people will be more willing to really embrace it.”

Promise in the clinic

Early clinical trials of gamma-wave treatments have shown dramatic results.

In 2016, Tsai and Boyden were scientific co-founders of Cognito Therapeutics, a startup that has raised $93 million to commercialize gamma-wave technology. In July 2023, Cognito reported positive preliminary results for a phase 2 trial of its proprietary goggle-like device among early-stage Alzheimer's patients. Participants displayed decreased loss of brain volume and a significant slowing in functional and cognitive decline. Cognito is going forward with a phase 3 study designed to enroll 500 patients.

At MIT, Tsai and her collaborators also conducted a small-scale clinical trial on early-stage Alzheimer's subjects. Rather than giving the participants goggles, the researchers installed an LED light panel and stereo in their homes. “We reduced brain volume loss and increased connectivity,” Tsai says. This study was shut down by the pandemic, but she and her collaborators are now resuming clinical tests.

Despite employing very different devices, the Cognito and MIT trials produced similar benefits. Gamma-wave devices should be far more accessible, and safer, than the drugs available to date, Tsai suggests. Unlike the Alzheimer's drugs recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the therapy doesn't require highly expensive infusions or pose the risks of brain swelling and bleeding.

Modeling your whole brain with miBrain

The gamma-wave research is one thread among many in Tsai's lab aimed at understanding the entire aging brain, with its genetic complexities, and to use that understanding to personalize treatments for neurodegenerative illnesses.

“You can think of Alzheimer’s disease as like breast cancer: Depending on what genes are disrupted, people will get different therapies,” Tsai says. “I think this is probably true for other degenerative diseases, like Parkinson's.”

Her team plans to take a huge step up in modeling human brain structures with the miBrain platform, basically multicellular brain chips built with stem cell technology. (Scientists can take human skin cells and induce them to become “pluripotent” stem cells, which means they can be reprogrammed to become various brain and blood vessel cells. Those cells can then be cultured together to form a complex approximation of brain tissue.)

“This miBrain system contains all the different cell types that normally you'll see in the brain,” says Tsai. “This is essential, because the cells in the brain don't exist in isolation. They're all together and they communicate with each other through secreted factors or cell-to-cell contact, and that's a very important part of how they maintain health and functionality.”

The integrated miBrain system will empower both basic research and drug screening. “For example, the blood-brain barrier prevents many molecules from entering the brain.” she says. “We can use this in-vitro-assembled blood-brain barrier to test whether a chemical targeting a brain disease can even get into the brain.”

She points out that the FDA recently decided that it would not always require animal testing data before approving drug candidates for trial. This regulatory move should accelerate the use of in-vitro models such as the miBrain for drug testing.

Over time, Tsai hopes the miBrain will evolve into a translational platform to deliver precision medicine, enabling individualized treatments for brain illnesses. “We can reprogram your skin cells into stem cells, and then we can make a miBrain out of your cells,” she says. “If you have Parkinson's disease, we can test certain therapeutic agents and see how your miBrain responds, and then further optimize how to treat you.”

She and her MIT collaborators are now launching a miBrain center, aimed to boost both basic and translational medical research.

Scaling up this center, however, will be no easy task. “The biggest challenge is manpower, because producing all the cell types and then assembling them into a miBrain is extremely labor-intensive,” she says. “It would be very helpful if we can team up with a company and develop this together.”

MIT offers tremendous opportunities for such collaborations. “I think MIT is in the best position to lead brain disease research, because we have people who are leaders in their disciplines here, doing not just brain research but engineering and artificial intelligence,” Tsai remarks. “We really hope that we can gather people together — scientists, engineers, policymakers and economists — to figure this out. This is the future of brain research; we need people using very different approaches to work together.”

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Li-Huei Tsai

- Videos: Li-Huei Tsai

- The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

Related Topics

- Alzheimer's

- Neuroscience

- Optogenetics

- Brain and cognitive sciences

- MIT intellectual property

- Picower Institute

Related Articles

Decoding the complexity of Alzheimer’s disease

How Tau tangles form in the brain

40 Hz vibrations reduce Alzheimer’s pathology, symptoms in mouse models

Two MIT professors named 2019 fellows of the National Academy of Inventors

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

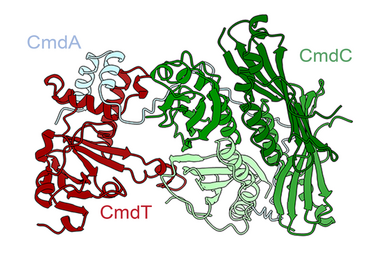

Killing the messenger

Read full story →

Communications user terminal developed by MIT Lincoln Laboratory prepares for historic moon flyby

How examining conflict can be “intellectually serious” and “incredibly fun”

Smart handling of neutrons is crucial to fusion power success

3 Questions: Can we secure a sustainable supply of nickel?

Revealing causal links in complex systems

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Researchers have found a protein that seems to protect brain cells from Alzheimer's

Jon Hamilton

Alzheimer's resilience

A study of 48 post-mortem brains found a protein that appears to protect brain cells from Alzheimer's — even in people who had significant amounts of amyloid plaques in their brains.

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Warning for younger women: Be vigilant on breast cancer risk

Study shows vitamin D doesn’t cut cardiac risk

Weight-loss surgery down 25 percent as anti-obesity drug use soars

Start of new era for alzheimer’s treatment.

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Expert discusses recent lecanemab trial, why it appears to offer hope for those with deadly disease

Researchers say we appear to be at the start of a new era for Alzheimer’s treatment. Trial results published in January showed that for the first time a drug has been able to slow the cognitive decline characteristic of the disease. The drug, lecanemab, is a monoclonal antibody that works by binding to a key protein linked to the malady, called amyloid-beta, and removing it from the body. Experts say the results offer hope that the slow, inexorable loss of memory and eventual death brought by Alzheimer’s may one day be a thing of the past.

The Gazette spoke with Scott McGinnis , an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Alzheimer’s disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital , about the results and a new clinical trial testing whether the same drug given even earlier can prevent its progression.

Scott McGinnis

GAZETTE: The results of the Clarity AD trial have some saying we’ve entered a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Do you agree?

McGINNIS: It’s appropriate to consider it a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Until we obtained the results of this study, trials suggested that the only mode of treatment was what we would call a “symptomatic therapeutic.” That might give a modest boost to cognitive performance — to memory and thinking and performance in usual daily activities. But a symptomatic drug does not act on the fundamental pathophysiology, the mechanisms, of the disease. The Clarity AD study was the first that unambiguously suggested a disease-modifying effect with clear clinical benefit. A couple of weeks ago, we also learned a study with a second drug, donanemab, yielded similar results.

GAZETTE: Hasn’t amyloid beta, which forms Alzheimer’s characteristic plaques in the brain and which was the target in this study, been a target in previous trials that have not been effective?

McGINNIS: That’s true. Amyloid beta removal has been the most widely studied mechanism in the field. Over the last 15 to 20 years, we’ve been trying to lower beta amyloid, and we’ve been uncertain about the benefits until this point. Unfavorable results in study after study contributed to a debate in the field about how important beta amyloid is in the disease process. To be fair, this debate is not completely settled, and the results of Clarity AD do not suggest that lecanemab is a cure for the disease. The results do, however, provide enough evidence to support the hypothesis that there is a disease-modifying effect via amyloid removal.

GAZETTE: Do we know how much of the decline in Alzheimer’s is due to beta amyloid?

McGINNIS: There are two proteins that define Alzheimer’s disease. The gold standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease is identifying amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. We know that amyloid beta plaques form in the brain early, prior to accumulation of tau and prior to changes in memory and thinking. In fact, the levels and locations of tau accumulation correlate much better with symptoms than the levels and locations of amyloid. But amyloid might directly “fuel the fire” to accelerated changes in tau and other downstream mechanisms, a hypothesis supported by basic science research and the findings in Clarity AD that treatment with lecanemab lowered levels of not just amyloid beta but also levels of tau and neurodegeneration in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

GAZETTE: In the Clarity AD trial, what’s the magnitude of the effect they saw?

McGINNIS: The relevant standards in the trial — set by the FDA and others — were to see two clinical benefits for the drug to be considered effective. One was a benefit on tests of memory and thinking, a cognitive benefit. The other was a benefit in terms of the performance in usual daily activities, a functional benefit. Lecanemab met both of these standards by slowing the rate of decline by approximately 25 to 35 percent compared to placebo on measures of cognitive and functional decline over the 18-month studies.

“In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal.”

Steven M. Smith

GAZETTE: What are the key questions that remain?

McGINNIS: An important question relates to the stages at which the interventions were done. The study was done in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer dementia. People who have mild cognitive impairment have retained their independence in instrumental activities of daily living — for example, driving, taking medications, managing finances, errands, chores — but have cognitive and memory changes beyond what we would attribute to normal aging. When people transition to mild dementia, they’re a bit further along. The study was for people within that spectrum but there’s some reason to believe that intervening even earlier might be more effective, as is the case with many other medical conditions.

We’re doing a study here called the AHEAD study that is investigating the effects of lecanemab when administered earlier, in cognitively normal individuals who have elevated brain amyloid, to see whether we see a preventative benefit. The hope is that we would at least see a delay to onset of cognitive impairment and a favorable effect not only on amyloid biomarkers, but other biomarkers that might capture progression of the disease.

GAZETTE: Is anybody in that study treatment yet or are you still enrolling?

McGINNIS: There’s a rolling enrollment, so there are people who are in the double-blind phase of treatment, receiving either the drug or the placebo. But the enrollment target hasn’t been reached yet so we’re still accepting new participants.

GAZETTE: Is it likely that we may see drug cocktails that go after tau and amyloid? Is that a future approach?

More like this

Newly identified genetic variant protects against Alzheimer’s

Using AI to target Alzheimer’s

Excessive napping and Alzheimer’s linked in study

McGINNIS: It has not yet been tried, but those of us in the field are very excited at the prospect of these studies. There’s been a lot of work in recent years on developing therapeutics that target tau, and I think we’re on the cusp of some important breakthroughs. This is key, considering evidence that spreading of tau from cell to cell might contribute to progression of the disease. Additionally, for some time, we’ve had a suspicion that we will likely have to target multiple different aspects of the disease process, as is the case with most types of cancer treatment. Many in our field believe that we will obtain the most success when we identify the most pertinent mechanisms for subgroups of people with Alzheimer’s disease and then specifically target those mechanisms. Examples might include metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and problems with elements of cellular processing, including mitochondrial functioning and processing old or damaged proteins. Multi-drug trials represent a natural next step.

GAZETTE: What about side effects from this drug?

McGINNIS: We’ve known for a long time that drugs in this class, antibodies that harness the power of the immune system to remove amyloid, carry a risk of causing swelling in the brain. In most cases, it’s asymptomatic and just detected by MRI scan. In Clarity AD, while 12 to 13 percent of participants receiving lecanemab had some level of swelling detected by MRI, it was symptomatic in only about 3 percent of participants and mild in most of those cases.

Another potential side effect is bleeding in the brain or on the surface of the brain. When we see bleeding, it’s usually very small, pinpoint areas of bleeding in the brain that are also asymptomatic. A subset of people with Alzheimer’s disease who don’t receive any treatment are going to have these because they have amyloid in their blood vessels, and it’s important that we screen for this with an MRI scan before a person receives treatment. In Clarity AD, we saw a rate of 9 percent in the placebo group and about 17 percent in the treatment group, many of those cases in conjunction with swelling and mostly asymptomatic.

The scenario that everybody worries about is a hemorrhagic stroke, a larger area of bleeding. That was much less common in this study, less than 1 percent of people. Unlike similar studies, this study allowed subjects to be on anticoagulation medications, which thin the blood to prevent or treat clots. The rate of macro hemorrhage — larger bleeds — was between 2 and 3 percent in the anticoagulated participants. There were some highly publicized cases including a patient who had a stroke, presented for treatment, received a medication to dissolve clots, then had a pretty bad hemorrhage. If the drug gets full FDA approval, is covered by insurance, and becomes clinically available, most physicians are probably not going to give it to people who are on anticoagulation. These are questions that we’ll have to work out as we learn more about the drug from ongoing research.

GAZETTE: Has this study, and these recent developments in the field, had an effect on patients?

McGINNIS: It has had a considerable impact. There’s a lot of interest in the possibility of receiving this drug or a similar drug, but our patients and their family members understand that this is not a cure. They understand that we’re talking about slowing down a rate of decline. In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal. So there’s hope. There’s optimism. Our patients, particularly patients who are at earlier stages of the disease, have their lives to live and are really interested in living life fully. Anything that can help them do that for a longer period of time is welcome.

Share this article

You might like.

Pathologist explains the latest report from the American Cancer Society

Outdoor physical activity may be a better target for preventive intervention, says researcher

Study authors call for more research examining how trend affects long-term patient outcomes

Mars may have been habitable much more recently than thought

Study bolsters theory that protective magnetic field supporting life-enabling atmosphere remained in place longer than estimates

Why do election polls seem to have such a mixed track record?

Democratic industry veteran looks at past races, details adjustments made amid shifting political dynamics in nation

Lecanemab, the New Alzheimer’s Treatment: 3 Things To Know

BY CARRIE MACMILLAN July 24, 2023

Yale researcher discusses the recent FDA approval of a new Alzheimer's disease treatment.

[Originally published January 19, 2023. Updated: July 24, 2023.]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently granted full approval to a new Alzheimer’s treatment called lecanemab, which has been shown to moderately slow cognitive and functional decline in early-stage cases of the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive disorder that damages and destroys nerve cells in the brain. Over time, the disease leads to a gradual loss of cognitive functions, including the ability to remember, reason, use language, and recognize familiar places. It can also cause a range of behavioral changes.

In January, the FDA gave the medication an accelerated approval based on amyloid plaque clearance. Christopher van Dyck, MD , director of Yale’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Unit, was the lead author of a study published in the Jan. 5 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine that shared results of a Phase III clinical trial of lecanemab. (Dr. van Dyck is also a paid consultant for the pharmaceutical company Eisai, which funded the trials.)

Sold under the brand name Leqembi™ and made by Eisai in partnership with Biogen Inc., the drug is delivered by an intravenous infusion every two weeks. Lecanemab works by removing a sticky protein from the brain that is believed to cause Alzheimer’s disease to advance.

“It’s very exciting because this is the first treatment in our history that shows an unequivocal slowing of decline in Alzheimer’s disease,” says Dr. van Dyck.

This is the first time in two decades that the FDA has granted full approval to a drug for Alzheimer’s, but there is also a “black box” warning on the medication—the agency’s strongest caution—because of safety concerns.

We talked more with Dr. van Dyck, who answered three questions about the new treatment.

How effective is lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease?

In a trial that involved 1,795 participants with early-stage, symptomatic Alzheimer’s, lecanemab slowed clinical decline by 27% after 18 months of treatment compared with those who received a placebo.

“The antibody treatment selectively targets the forms of amyloid protein that are thought to be the most toxic to brain cells,” says Dr. van Dyck.

Study participants who received the treatment had a significant reduction in amyloid burden in imaging tests, usually reaching normal levels by the end of the trial. Participants also showed a 26% slowing of decline in a key secondary measure of cognitive function and a 37% slowing of decline in a measure of daily living compared to the placebo group.

“Would I like the numbers to be higher? Of course, but I don’t think this is a small effect,” says Dr. van Dyck. “These results could also indicate a starting point for bigger effects. The data appear encouraging that the longer the treatment period, the better the effect. But we’ll need more studies to determine if that’s true.”

They also beg the question about still-earlier intervention, adds Dr. van Dyck. Lecanemab is already being tested in the global AHEAD study for individuals who are still cognitively normal but at high risk of symptoms due to elevated levels of brain amyloid.

Yale currently has the largest number of participants in the AHEAD study, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Eisai and is enrolling participants as young as 55. “We may see a larger benefit if we intervene before significant brain damage has occurred,” he says.

Is lecanemab safe?

The most common side effect (26.4% of participants vs. 7.4% in the placebo group) of the treatment is an infusion-related reaction, which may include transient symptoms, such as flushing, chills, fever, rash, and body aches. The majority (96%) of these reactions were mild to moderate, and 75% happened after the first dose.

“We can medicate those individuals in advance if we find they have those side effects repeatedly,” says Dr. van Dyck. “We can use medications such as diphenhydramine or acetaminophen. But this is generally not an issue.”

Another potential side effect associated with lecanemab was amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema, or fluid formation on the brain. This occurred in 12.6% of trial participants compared to 1.7% in the placebo group. “It’s usually asymptomatic when it occurs, but we can detect it on MRI scans. We often don’t stop dosing if we see it, unless there are symptoms, in which case we would pause infusions until it fully resolves,” Dr. van Dyck says.

It’s important to note that the studies with lecanemab show substantially lower rates of this side effect than do published trials of other, similar drugs such as aducanumab—they're at about a third of the rate, explains Dr. van Dyck. “So, for drugs in this class, I think lecanemab has a favorable safety profile,” he says.

Lastly, 17.3% of trial participants experienced amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with brain bleeding compared to 9% in the placebo group.

“Most of the time we're really talking about microhemorrhages that are in the order of millimeters,” says Dr. van Dyck. “People with Alzheimer's disease are more prone to these events because of the amyloid deposits in their blood vessels, but a catastrophic bleed is quite rare.”

The medication’s label includes warnings about brain swelling and bleeding and that people with a gene mutation that increases their risk of Alzheimer’s disease are at greater risk of brain swelling on the treatment. The label also cautions against taking blood thinners while on the medication.

When will lecanemab be available for Alzheimer’s disease treatment?

Eisai set the price for Leqembi at $26,500 per year, and it has reportedly been largely unavailable while FDA full approval was pending. That may change now that Medicare has said it will cover 80% of the cost.

More news from Yale Medicine

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

SEATTLE — New research at the Allen …

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that impairs memory and cognitive judgment and is often accompanied by mood swings, disorientation and eventually delirium.

Working with Boyden and MIT Professor Emery Brown, Iaccarino discovered that enhancing 40-cycle-per-second gamma waves via flickering light stimulation could significantly reduce levels of the amyloid protein that is a lead …

New findings out of Emory University are challenging existing theories about the origins of Alzheimer’s, the leading cause of dementia in the elderly worldwide. A team led by …

A study of 48 post-mortem brains found a protein that appears to protect brain cells from Alzheimer's — even in people who had significant amounts of amyloid plaques in their …

Researchers say we appear to be at the start of a new era for Alzheimer’s treatment. Trial results published in January showed that for the first time a drug has been able to slow the cognitive decline characteristic of the …

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently granted full approval to a new Alzheimer’s treatment called lecanemab, which has been shown to moderately slow cognitive and functional decline in early-stage cases …