Advertisement

The “new normal” in education

- Viewpoints/ Controversies

- Published: 24 November 2020

- Volume 51 , pages 3–14, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- José Augusto Pacheco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4623-6898 1

346k Accesses

47 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Effects rippling from the Covid 19 emergency include changes in the personal, social, and economic spheres. Are there continuities as well? Based on a literature review (primarily of UNESCO and OECD publications and their critics), the following question is posed: How can one resist the slide into passive technologization and seize the possibility of achieving a responsive, ethical, humane, and international-transformational approach to education? Technologization, while an ongoing and evidently ever-intensifying tendency, is not without its critics, especially those associated with the humanistic tradition in education. This is more apparent now that curriculum is being conceived as a complicated conversation. In a complex and unequal world, the well-being of students requires diverse and even conflicting visions of the world, its problems, and the forms of knowledge we study to address them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Rethinking L1 Education in a Global Era: The Subject in Focus

Assuming the Future: Repurposing Education in a Volatile Age

Thinking Multidimensionally About Ambitious Educational Change

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

From the past, we might find our way to a future unforeclosed by the present (Pinar 2019 , p. 12)

Texts regarding this pandemic’s consequences are appearing at an accelerating pace, with constant coverage by news outlets, as well as philosophical, historical, and sociological reflections by public intellectuals worldwide. Ripples from the current emergency have spread into the personal, social, and economic spheres. But are there continuities as well? Is the pandemic creating a “new normal” in education or simply accenting what has already become normal—an accelerating tendency toward technologization? This tendency presents an important challenge for education, requiring a critical vision of post-Covid-19 curriculum. One must pose an additional question: How can one resist the slide into passive technologization and seize the possibility of achieving a responsive, ethical, humane, and international-transformational approach to education?

The ongoing present

Unpredicted except through science fiction, movie scripts, and novels, the Covid-19 pandemic has changed everyday life, caused wide-scale illness and death, and provoked preventive measures like social distancing, confinement, and school closures. It has struck disproportionately at those who provide essential services and those unable to work remotely; in an already precarious marketplace, unemployment is having terrible consequences. The pandemic is now the chief sign of both globalization and deglobalization, as nations close borders and airports sit empty. There are no departures, no delays. Everything has changed, and no one was prepared. The pandemic has disrupted the flow of time and unraveled what was normal. It is the emergence of an event (think of Badiou 2009 ) that restarts time, creates radical ruptures and imbalances, and brings about a contingency that becomes a new necessity (Žižek 2020 ). Such events question the ongoing present.

The pandemic has reshuffled our needs, which are now based on a new order. Whether of short or medium duration, will it end in a return to the “normal” or move us into an unknown future? Žižek contends that “there is no return to normal, the new ‘normal’ will have to be constructed on the ruins of our old lives, or we will find ourselves in a new barbarism whose signs are already clearly discernible” (Žižek 2020 , p. 3).

Despite public health measures, Gil ( 2020 ) observes that the pandemic has so far generated no physical or spiritual upheaval and no universal awareness of the need to change how we live. Techno-capitalism continues to work, though perhaps not as before. Online sales increase and professionals work from home, thereby creating new digital subjectivities and economies. We will not escape the pull of self-preservation, self-regeneration, and the metamorphosis of capitalism, which will continue its permanent revolution (Wells 2020 ). In adapting subjectivities to the recent demands of digital capitalism, the pandemic can catapult us into an even more thoroughly digitalized space, a trend that artificial intelligence will accelerate. These new subjectivities will exhibit increased capacities for voluntary obedience and programmable functioning abilities, leading to a “new normal” benefiting those who are savvy in software-structured social relationships.

The Covid-19 pandemic has submerged us all in the tsunami-like economies of the Cloud. There is an intensification of the allegro rhythm of adaptation to the Internet of Things (Davies, Beauchamp, Davies, and Price 2019 ). For Latour ( 2020 ), the pandemic has become internalized as an ongoing state of emergency preparing us for the next crisis—climate change—for which we will see just how (un)prepared we are. Along with inequality, climate is one of the most pressing issues of our time (OECD 2019a , 2019b ) and therefore its representation in the curriculum is of public, not just private, interest.

Education both reflects what is now and anticipates what is next, recoding private and public responses to crises. Žižek ( 2020 , p. 117) suggests in this regard that “values and beliefs should not be simply ignored: they play an important role and should be treated as a specific mode of assemblage”. As such, education is (post)human and has its (over)determination by beliefs and values, themselves encoded in technology.

Will the pandemic detoxify our addiction to technology, or will it cement that addiction? Pinar ( 2019 , pp. 14–15) suggests that “this idea—that technological advance can overcome cultural, economic, educational crises—has faded into the background. It is our assumption. Our faith prompts the purchase of new technology and assures we can cure climate change”. While waiting for technology to rescue us, we might also remember to look at ourselves. In this way, the pandemic could be a starting point for a more sustainable environment. An intelligent response to climate change, reactivating the humanistic tradition in education, would reaffirm the right to such an education as a global common good (UNESCO 2015a , p. 10):

This approach emphasizes the inclusion of people who are often subject to discrimination – women and girls, indigenous people, persons with disabilities, migrants, the elderly and people living in countries affected by conflict. It requires an open and flexible approach to learning that is both lifelong and life-wide: an approach that provides the opportunity for all to realize their potential for a sustainable future and a life of dignity”.

Pinar ( 2004 , 2009 , 2019 ) concevies of curriculum as a complicated conversation. Central to that complicated conversation is climate change, which drives the need for education for sustainable development and the grooming of new global citizens with sustainable lifestyles and exemplary environmental custodianship (Marope 2017 ).

The new normal

The pandemic ushers in a “new” normal, in which digitization enforces ways of working and learning. It forces education further into technologization, a development already well underway, fueled by commercialism and the reigning market ideology. Daniel ( 2020 , p. 1) notes that “many institutions had plans to make greater use of technology in teaching, but the outbreak of Covid-19 has meant that changes intended to occur over months or years had to be implemented in a few days”.

Is this “new normal” really new or is it a reiteration of the old?

Digital technologies are the visible face of the immediate changes taking place in society—the commercial society—and schools. The immediate solution to the closure of schools is distance learning, with platforms proliferating and knowledge demoted to information to be exchanged (Koopman 2019 ), like a product, a phenomenon predicted decades ago by Lyotard ( 1984 , pp. 4-5):

Knowledge is and will be produced in order to be sold, it is and will be consumed in order to be valued in a new production: in both cases, the goal is exchange. Knowledge ceases to be an end in itself, it loses its use-value.

Digital technologies and economic rationality based on performance are significant determinants of the commercialization of learning. Moving from physical face-to-face presence to virtual contact (synchronous and asynchronous), the learning space becomes disembodied, virtual not actual, impacting both student learning and the organization of schools, which are no longer buildings but websites. Such change is not only coterminous with the pandemic, as the Education 2030 Agenda (UNESCO 2015b ) testified; preceding that was the Delors Report (Delors 1996 ), which recoded education as lifelong learning that included learning to know, learning to do, learning to be, and learning to live together.

Transnational organizations have specified competences for the 21st century and, in the process, have defined disciplinary and interdisciplinary knowledge that encourages global citizenship, through “the supra curriculum at the global, regional, or international comparative level” (Marope 2017 , p. 10). According to UNESCO ( 2017 ):

While the world may be increasingly interconnected, human rights violations, inequality and poverty still threaten peace and sustainability. Global Citizenship Education (GCED) is UNESCO’s response to these challenges. It works by empowering learners of all ages to understand that these are global, not local issues and to become active promoters of more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive, secure and sustainable societies.

These transnational initiatives have not only acknowledged traditional school subjects but have also shifted the curriculum toward timely topics dedicated to understanding the emergencies of the day (Spiller 2017 ). However, for the OECD ( 2019a ), the “new normal” accentuates two ideas: competence-based education, which includes the knowledges identified in the Delors Report , and a new learning framework structured by digital technologies. The Covid-19 pandemic does not change this logic. Indeed, the interdisciplinary skills framework, content and standardized testing associated with the Programme for International Student Assessment of the OECD has become the most powerful tool for prescribing the curriculum. Educationally, “the universal homogenous ‘state’ exists already. Globalization of standardized testing—the most prominent instance of threatening to restructure schools into technological sites of political socialization, conditioning children for compliance to a universal homogeneous state of mind” (Pinar 2019 , p. 2).

In addition to cognitive and practical skills, this “homogenous state of mind” rests on so-called social and emotional skills in the service of learning to live together, affirming global citizenship, and presumably returning agency to students and teachers (OECD 2019a ). According to Marope ( 2017 , p. 22), “this calls for higher flexibility in curriculum development, and for the need to leave space for curricula interpretation, contextualization, and creativity at the micro level of teachers and classrooms”. Heterogeneity is thus enlisted in the service of both economic homogeneity and disciplinary knowledge. Disciplinary knowledge is presented as universal and endowed with social, moral, and cognitive authority. Operational and effective knowledge becomes central, due to the influence of financial lobbies, thereby ensuring that the logic of the market is brought into the practices of schools. As Pestre ( 2013 , p. 21) observed, “the nature of this knowledge is new: what matters is that it makes hic et nunc the action, its effect and not its understanding”. Its functionality follows (presumably) data and evidence-based management.

A new language is thus imposed on education and the curriculum. Such enforced installation of performative language and Big Data lead to effective and profitable operations in a vast market concerned with competence in operational skills (Lyotard 1984 ). This “new normal” curriculum is said to be more horizontal and less hierarchical and radically polycentric with problem-solving produced through social networks, NGOs, transnational organizations, and think tanks (Pestre 2013 ; Williamson 2013 , 2017 ). Untouched by the pandemic, the “new (old) normal” remains based on disciplinary knowledge and enmeshed in the discourse of standards and accountability in education.

Such enforced commercialism reflects and reinforces economic globalization. Pinar ( 2011 , p. 30) worries that “the globalization of instrumental rationality in education threatens the very existence of education itself”. In his theory, commercialism and the technical instrumentality by which homogenization advances erase education as an embodied experience and the curriculum as a humanistic project. It is a time in which the humanities are devalued as well, as acknowledged by Pinar ( 2019 , p. 19): “In the United States [and in the world] not only does economics replace education—STEM replace the liberal arts as central to the curriculum—there are even politicians who attack the liberal arts as subversive and irrelevant…it can be more precisely characterized as reckless rhetoric of a know-nothing populism”. Replacing in-person dialogical encounters and the educational cultivation of the person (via Bildung and currere ), digital technologies are creating uniformity of learning spaces, in spite of their individualistic tendencies. Of course, education occurs outside schools—and on occasion in schools—but this causal displacement of the centrality of the school implies a devaluation of academic knowledge in the name of diversification of learning spaces.

In society, education, and specifically in the curriculum, the pandemic has brought nothing new but rather has accelerated already existing trends that can be summarized as technologization. Those who can work “remotely” exercise their privilege, since they can exploit an increasingly digital society. They themselves are changed in the process, as their own subjectivities are digitalized, thus predisposing them to a “curriculum of things” (a term coined by Laist ( 2016 ) to describe an object-oriented pedagogical approach), which is organized not around knowledge but information (Koopman 2019 ; Couldry and Mejias 2019 ). This (old) “new normal” was advanced by the OECD, among other international organizations, thus precipitating what some see as “a dynamic and transformative articulation of collective expectations of the purpose, quality, and relevance of education and learning to holistic, inclusive, just, peaceful, and sustainable development, and to the well-being and fulfilment of current and future generations” (Marope 2017 , p. 13). Covid-19, illiberal democracy, economic nationalism, and inaction on climate change, all upend this promise.

Understanding the psychological and cultural complexity of the curriculum is crucial. Without appreciating the infinity of responses students have to what they study, one cannot engage in the complicated conversation that is the curriculum. There must be an affirmation of “not only the individualism of a person’s experience but [of what is] underlining the significance of a person’s response to a course of study that has been designed to ignore individuality in order to buttress nation, religion, ethnicity, family, and gender” (Grumet 2017 , p. 77). Rather than promoting neuroscience as the answer to the problems of curriculum and pedagogy, it is long-past time for rethinking curriculum development and addressing the canonical curriculum question: What knowledge is of most worth from a humanistic perspective that is structured by complicated conversation (UNESCO 2015a ; Pinar 2004 , 2019 )? It promotes respect for diversity and rejection of all forms of (cultural) hegemony, stereotypes, and biases (Pacheco 2009 , 2017 ).

Revisiting the curriculum in the Covid-19 era then expresses the fallacy of the “new normal” but also represents a particular opportunity to promote a different path forward.

Looking to the post-Covid-19 curriculum

Based on the notion of curriculum as a complicated conversation, as proposed by Pinar ( 2004 ), the post-Covid-19 curriculum can seize the possibility of achieving a responsive, ethical, humane education, one which requires a humanistic and internationally aware reconceptualization of curriculum.

While beliefs and values are anchored in social and individual practices (Pinar 2019 , p. 15), education extracts them for critique and reconsideration. For example, freedom and tolerance are not neutral but normative practices, however ideology-free policymakers imagine them to be.

That same sleight-of-hand—value neutrality in the service of a certain normativity—is evident in a digital concept of society as a relationship between humans and non-humans (or posthumans), a relationship not only mediated by but encapsulated within technology: machines interfacing with other machines. This is not merely a technological change, as if it were a quarantined domain severed from society. Technologization is a totalizing digitalization of human experience that includes the structures of society. It is less social than economic, with social bonds now recoded as financial transactions sutured by software. Now that subjectivity is digitalized, the human face has become an exclusively economic one that fabricates the fantasy of rational and free agents—always self-interested—operating in supposedly free markets. Oddly enough, there is no place for a vision of humanistic and internationally aware change. The technological dimension of curriculum is assumed to be the primary area of change, which has been deeply and totally imposed by global standards. The worldwide pandemic supports arguments for imposing forms of control (Žižek 2020 ), including the geolocation of infected people and the suspension—in a state of exception—of civil liberties.

By destroying democracy, the technology of control leads to totalitarianism and barbarism, ending tolerance, difference, and diversity. Remembrance and memory are needed so that historical fascisms (Eley 2020 ) are not repeated, albeit in new disguises (Adorno 2011 ). Technologized education enhances efficiency and ensures uniformity, while presuming objectivity to the detriment of human reflection and singularity. It imposes the running data of the Curriculum of Things and eschews intellectual endeavor, critical attitude, and self-reflexivity.

For those who advocate the primacy of technology and the so-called “free market”, the pandemic represents opportunities not only for profit but also for confirmation of the pervasiveness of human error and proof of the efficiency of the non-human, i.e., the inhuman technology. What may possibly protect children from this inhumanity and their commodification, as human capital, is a humane or humanistic education that contradicts their commodification.

The decontextualized technical vocabulary in use in a market society produces an undifferentiated image in which people are blinded to nuance, distinction, and subtlety. For Pestre, concepts associated with efficiency convey the primacy of economic activity to the exclusion, for instance, of ethics, since those concepts devalue historic (if unrealized) commitments to equality and fraternity by instead emphasizing economic freedom and the autonomy of self-interested individuals. Constructing education as solely economic and technological constitutes a movement toward total efficiency through the installation of uniformity of behavior, devaluing diversity and human creativity.

Erased from the screen is any image of public education as a space of freedom, or as Macdonald ( 1995 , p. 38) holds, any image or concept of “the dignity and integrity of each human”. Instead, what we face is the post-human and the undisputed reign of instrumental reality, where the ends justify the means and human realization is reduced to the consumption of goods and experiences. As Pinar ( 2019 , p. 7) observes: “In the private sphere…. freedom is recast as a choice of consumer goods; in the public sphere, it converts to control and the demand that freedom flourish, so that whatever is profitable can be pursued”. Such “negative” freedom—freedom from constraint—ignores “positive” freedom, which requires us to contemplate—in ethical and spiritual terms—what that freedom is for. To contemplate what freedom is for requires “critical and comprehensive knowledge” (Pestre 2013 , p. 39) not only instrumental and technical knowledge. The humanities and the arts would reoccupy the center of such a curriculum and not be related to its margins (Westbury 2008 ), acknowledging that what is studied within schools is a complicated conversation among those present—including oneself, one’s ancestors, and those yet to be born (Pinar 2004 ).

In an era of unconstrained technologization, the challenge facing the curriculum is coding and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), with technology dislodging those subjects related to the human. This is not a classical curriculum (although it could be) but one focused on the emergencies of the moment–namely, climate change, the pandemic, mass migration, right-wing populism, and economic inequality. These timely topics, which in secondary school could be taught as short courses and at the elementary level as thematic units, would be informed by the traditional school subjects (yes, including STEM). Such a reorganization of the curriculum would allow students to see how academic knowledge enables them to understand what is happening to them and their parents in their own regions and globally. Such a cosmopolitan curriculum would prepare children to become citizens not only of their own nations but of the world. This citizenship would simultaneously be subjective and social, singular and universal (Marope 2020 ). Pinar ( 2019 , p. 5) reminds us that “the division between private and public was first blurred then erased by technology”:

No longer public, let alone sacred, morality becomes a matter of privately held values, sometimes monetized as commodities, statements of personal preference, often ornamental, sometimes self-servingly instrumental. Whatever their function, values were to be confined to the private sphere. The public sphere was no longer the civic square but rather, the marketplace, the site where one purchased whatever one valued.

New technological spaces are the universal center for (in)human values. The civic square is now Amazon, Alibaba, Twitter, WeChat, and other global online corporations. The facts of our human condition—a century-old phrase uncanny in its echoes today—can be studied in schools as an interdisciplinary complicated conversation about public issues that eclipse private ones (Pinar 2019 ), including social injustice, inequality, democracy, climate change, refugees, immigrants, and minority groups. Understood as a responsive, ethical, humane and transformational international educational approach, such a post-Covid-19 curriculum could be a “force for social equity, justice, cohesion, stability, and peace” (Marope 2017 , p. 32). “Unchosen” is certainly the adjective describing our obligations now, as we are surrounded by death and dying and threatened by privation or even starvation, as economies collapse and food-supply chains are broken. The pandemic may not mean deglobalization, but it surely accentuates it, as national borders are closed, international travel is suspended, and international trade is impacted by the accompanying economic crisis. On the other hand, economic globalization could return even stronger, as could the globalization of education systems. The “new normal” in education is the technological order—a passive technologization—and its expansion continues uncontested and even accelerated by the pandemic.

Two Greek concepts, kronos and kairos , allow a discussion of contrasts between the quantitative and the qualitative in education. Echoing the ancient notion of kronos are the technologically structured curriculum values of quantity and performance, which are always assessed by a standardized accountability system enforcing an “ideology of achievement”. “While kronos refers to chronological or sequential time, kairos refers to time that might require waiting patiently for a long time or immediate and rapid action; which course of action one chooses will depend on the particular situation” (Lahtinen 2009 , p. 252).

For Macdonald ( 1995 , p. 51), “the central ideology of the schools is the ideology of achievement …[It] is a quantitative ideology, for even to attempt to assess quality must be quantified under this ideology, and the educational process is perceived as a technically monitored quality control process”.

Self-evaluation subjectively internalizes what is useful and in conformity with the techno-economy and its so-called standards, increasingly enforcing technical (software) forms. If recoded as the Internet of Things, this remains a curriculum in allegiance with “order and control” (Doll 2013 , p. 314) School knowledge is reduced to an instrument for economic success, employing compulsory collaboration to ensure group think and conformity. Intertwined with the Internet of Things, technological subjectivity becomes embedded in software, redesigned for effectiveness, i.e., or use-value (as Lyotard predicted).

The Curriculum of Things dominates the Internet, which is simultaneously an object and a thing (see Heidegger 1967 , 1971 , 1977 ), a powerful “technological tool for the process of knowledge building” (Means 2008 , p. 137). Online learning occupies the subjective zone between the “curriculum-as-planned” and the “curriculum-as-lived” (Pinar 2019 , p. 23). The world of the curriculum-as-lived fades, as the screen shifts and children are enmeshed in an ocularcentric system of accountability and instrumentality.

In contrast to kronos , the Greek concept of kairos implies lived time or even slow time (Koepnick 2014 ), time that is “self-reflective” (Macdonald 1995 , p. 103) and autobiographical (Pinar 2009 , 2004), thus inspiring “curriculum improvisation” (Aoki 2011 , p. 375), while emphasizing “the plurality of subjectivities” (Grumet 2017 , p. 80). Kairos emphasizes singularity and acknowledges particularities; it is skeptical of similarities. For Shew ( 2013 , p. 48), “ kairos is that which opens an originary experience—of the divine, perhaps, but also of life or being. Thought as such, kairos as a formative happening—an opportune moment, crisis, circumstance, event—imposes its own sense of measure on time”. So conceived, curriculum can become a complicated conversation that occurs not in chronological time but in its own time. Such dialogue is not neutral, apolitical, or timeless. It focuses on the present and is intrinsically subjective, even in public space, as Pinar ( 2019 , p. 12) writes: “its site is subjectivity as one attunes oneself to what one is experiencing, yes to its immediacy and specificity but also to its situatedness, relatedness, including to what lies beyond it and not only spatially but temporally”.

Kairos is, then, the uniqueness of time that converts curriculum into a complicated conversation, one that includes the subjective reconstruction of learning as a consciousness of everyday life, encouraging the inner activism of quietude and disquietude. Writing about eternity, as an orientation towards the future, Pinar ( 2019 , p. 2) argues that “the second side [the first is contemplation] of such consciousness is immersion in daily life, the activism of quietude – for example, ethical engagement with others”. We add disquietude now, following the work of the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. Disquietude is a moment of eternity: “Sometimes I think I’ll never leave ‘Douradores’ Street. And having written this, it seems to me eternity. Neither pleasure, nor glory, nor power. Freedom, only freedom” (Pesssoa 1991 ).

The disquietude conversation is simultaneously individual and public. It establishes an international space both deglobalized and autonomous, a source of responsive, ethical, and humane encounter. No longer entranced by the distracting dynamic stasis of image-after-image on the screen, the student can face what is his or her emplacement in the physical and natural world, as well as the technological world. The student can become present as a person, here and now, simultaneously historical and timeless.

Conclusions

Slow down and linger should be our motto now. A slogan yes, but it also represents a political, as well as a psychological resistance to the acceleration of time (Berg and Seeber 2016 )—an acceleration that the pandemic has intensified. Covid-19 has moved curriculum online, forcing children physically apart from each other and from their teachers and especially from the in-person dialogical encounters that classrooms can provide. The public space disappears into the pre-designed screen space that software allows, and the machine now becomes the material basis for a curriculum of things, not persons. Like the virus, the pandemic curriculum becomes embedded in devices that technologize our children.

Although one hundred years old, the images created in Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin return, less humorous this time than emblematic of our intensifying subjection to technological necessity. It “would seem to leave us as cogs in the machine, ourselves like moving parts, we keep functioning efficiently, increasing productivity calculating the creative destruction of what is, the human now materialized (de)vices ensnaring us in convenience, connectivity, calculation” (Pinar 2019 , p. 9). Post-human, as many would say.

Technology supports standardized testing and enforces software-designed conformity and never-ending self-evaluation, while all the time erasing lived, embodied experience and intellectual independence. Ignoring the evidence, others are sure that technology can function differently: “Given the potential of information and communication technologies, the teacher should now be a guide who enables learners, from early childhood throughout their learning trajectories, to develop and advance through the constantly expanding maze of knowledge” (UNESCO 2015a , p. 51). Would that it were so.

The canonical question—What knowledge is of most worth?—is open-ended and contentious. In a technologized world, providing for the well-being of children is not obvious, as well-being is embedded in ancient, non-neoliberal visions of the world. “Education is everybody’s business”, Pinar ( 2019 , p. 2) points out, as it fosters “responsible citizenship and solidarity in a global world” (UNESCO 2015a , p. 66), resisting inequality and the exclusion, for example, of migrant groups, refugees, and even those who live below or on the edge of poverty.

In this fast-moving digital world, education needs to be inclusive but not conformist. As the United Nations ( 2015 ) declares, education should ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. “The coming years will be a vital period to save the planet and to achieve sustainable, inclusive human development” (United Nations 2019 , p. 64). Is such sustainable, inclusive human development achievable through technologization? Can technology succeed where religion has failed?

Despite its contradictions and economic emphases, public education has one clear obligation—to create embodied encounters of learning through curriculum conceived as a complicated conversation. Such a conception acknowledges the worldliness of a cosmopolitan curriculum as it affirms the personification of the individual (Pinar 2011 ). As noted by Grumet ( 2017 , p. 89), “as a form of ethics, there is a responsibility to participate in conversation”. Certainly, it is necessary to ask over and over again the canonical curriculum question: What knowledge is of most worth?

If time, technology and teaching are moving images of eternity, curriculum and pedagogy are also, both ‘moving’ and ‘images’ but not an explicit, empirical, or exact representation of eternity…if reality is an endless series of ‘moving images’, the canonical curriculum question—What knowledge is of most worth?—cannot be settled for all time by declaring one set of subjects eternally important” (Pinar 2019 , p. 12).

In a complicated conversation, the curriculum is not a fixed image sliding into a passive technologization. As a “moving image”, the curriculum constitutes a politics of presence, an ongoing expression of subjectivity (Grumet 2017 ) that affirms the infinity of reality: “Shifting one’s attitude from ‘reducing’ complexity to ‘embracing’ what is always already present in relations and interactions may lead to thinking complexly, abiding happily with mystery” (Doll 2012 , p. 172). Describing the dialogical encounter characterizing conceived curriculum, as a complicated conversation, Pinar explains that this moment of dialogue “is not only place-sensitive (perhaps classroom centered) but also within oneself”, because “the educational significance of subject matter is that it enables the student to learn from actual embodied experience, an outcome that cannot always be engineered” (Pinar 2019 , pp. 12–13). Lived experience is not technological. So, “the curriculum of the future is not just a matter of defining content and official knowledge. It is about creating, sculpting, and finessing minds, mentalities, and identities, promoting style of thought about humans, or ‘mashing up’ and ‘making up’ the future of people” (Williamson 2013 , p. 113).

Yes, we need to linger and take time to contemplate the curriculum question. Only in this way will we share what is common and distinctive in our experience of the current pandemic by changing our time and our learning to foreclose on our future. Curriculum conceived as a complicated conversation restarts historical not screen time; it enacts the private and public as distinguishable, not fused in a computer screen. That is the “new normal”.

Adorno, T. W. (2011). Educação e emancipação [Education and emancipation]. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

Aoki, T. T. (2011). Sonare and videre: A story, three echoes and a lingering note. In W. F. W. Pinar & R. L. Irwin (Eds.), Curriculum in a new key. The collected works of Ted T. Aoki (pp. 368–376). New York, NY: Routledge.

Badiou, A. (2009). Theory of the subject . London: Continuum.

Book Google Scholar

Berg, M., & Seeber, B. (2016). The slow professor: Challenging the culture of speed in the academy . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019). The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Google Scholar

Daniel, S. J. (2020). Education and the Covid-19 pandemic. Prospects . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3 .

Article Google Scholar

Davies, D., Beauchamp, G., Davies, J., & Price, R. (2019). The potential of the ‘Internet of Things’ to enhance inquiry in Singapore schools. Research in Science & Technological Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2019.1629896 .

Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within . Paris: UNESCO.

Doll, W. E. (2012). Thinking complexly. In D. Trueit (Ed.), Pragmatism, post-modernism, and complexity theory: The “fascinating imaginative realm” of William E. Doll, Jr. (pp. 172–187). New York, NY: Routledge.

Doll, W. E. (2013). Curriculum and concepts of control. In W. F. Pinar (Ed.), Curriculum: Toward new identities (pp. 295–324). New York, NY: Routledge.

Eley, G. (2020). Conclusion. In J. A. Thomas & G. Eley (Eds.), Visualizing fascism: The twentieth-century rise of the global Right (pp. 284–292). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Gil, J. (2020). A pandemia e o capitalismo numérico [The pandemic and numerical capitalism]. Público . https://www.publico.pt/2020/04/12/sociedade/ensaio/pandemia-capitalismo-numerico-1911986 .

Grumet, M.G. (2017). The politics of presence. In M. A. Doll (Ed.), The reconceptualization of curriculum studies. A Festschrift in honor of William F. Pinar (pp. 76–83). New York, NY: Routledge.

Heidegger, M. (1967). What is a thing? South Bend, IN: Gateway Editions.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, language, thought . New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Heidegger, M. (1977). The question concerning technology and other essays . New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Koepnick, L. (2014). On slowness: Toward an aesthetic of the contemporary . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Koopman, C. (2019). How we became our data: A genealogy of the informational person . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lahtinen, M. (2009). Politics and curriculum . Leiden: Brill.

Laist, R. (2016). A curriculum of things: Exploring an object-oriented pedagogy. The National Teaching & Learning, 25 (3), 1–4.

Latour, B. (2020). Is this a dress rehearsal? Critical Inquiry . https://critinq.wordpress.com/2020/03/26/is-this-a-dress-rehearsal

Lyotard, J. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Macdonald, B. J. (1995). Theory as a prayerful act . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Marope, P. T. M. (2017). Reconceptualizing and repositioning curriculum in the 21st century: A global paradigm shift . Geneva: UNESCO IBE.

Marope, P. T. M. (2020). Preventing violent extremism through universal values in curriculum. Prospects, 48 (1), 1–5.

Means, B. (2008). Technology’s role in curriculum and instruction. In F. M. Connelly (Ed.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 123–144). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

OECD (2019a). OECD learning compass 2030 . Paris: OECD.

OECD (2019b). Trends shaping education 2019 . Paris: OECD.

Pacheco, J. A. (2009). Whole, bright, deep with understanding: Life story and politics of curriculum studies. In-between William Pinar and Ivor Goodson . Roterdam/Taipei: Sense Publishers.

Pacheco, J. A. (2017). Pinar’s influence on the consolidation of Portuguese curriculum studies. In M. A. Doll (Ed.), The reconceptualization of curriculum studies. A Festschrift in honor of William F. Pinar (pp. 130–136). New York, NY: Routledge.

Pestre, D. (2013). Science, technologie et société. La politique des savoirs aujourd’hui [Science, technology, and society: Politics of knowledge today]. Paris: Foundation Calouste Gulbenkian.

Pesssoa, F. (1991). The book of disquietude . Manchester: Carcanet Press.

Pinar, W. F. (2004). What is curriculum theory? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pinar, W. F. (2009). The worldliness of a cosmopolitan education: Passionate lives in public service . New York, NY: Routledge.

Pinar, W. F. (2011). “A lingering note”: An introduction to the collected work of Ted T. Aoki. In W. F. Pinar & R. L. Irwin (Eds.), Curriculum in a new key. The collected works of Ted T. Aoki (pp. 1–85). New York, NY: Routledge.

Pinar, W. F. (2019). Moving images of eternity: George Grant’s critique of time, teaching, and technology . Ottawa: The University of Ottawa Press.

Shew, M. (2013). The Kairos philosophy. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 27 (1), 47–66.

Spiller, P. (2017). Could subjects soon be a thing of the past in Finland? BBC News . https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39889523 .

UNESCO (2015a). Rethinking education. Towards a global common global? Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2015b). Education 2030. Framework for action . Paris: UNESCO. https://www.sdg4education2030.org/sdg-education-2030-steering-committee-resources .

UNESCO (2017). Global citizenship education . Paris: UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced .

United Nations (2015). The sustainable development goals . New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations (2019). The sustainable development goals report . New York, NY: United Nations.

Wells, W. (2020). Permanent revolution: Reflections on capitalism . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Westbury, I. (2008). Making curricula. Why do states make curricula, and how? In F. M. Connelly (Ed.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 45–65). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Williamson, B. (2013). The future of the curriculum. School knowledge in the digital age . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Williamson, B. (2017). Big data in education. The digital future of learning, policy and practice . London: Sage.

Žižek, S. (2020). PANDEMIC! Covid-19 shakes the world . New York, NY: Or Books.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Research Centre on Education (CIEd), Institute of Education, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057, Braga, Portugal

José Augusto Pacheco

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to José Augusto Pacheco .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

My thanks to William F. Pinar. Friendship is another moving image of eternity. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewer. This work is financed by national funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, under the project PTDC / CED-EDG / 30410/2017, Centre for Research in Education, Institute of Education, University of Minho.

About this article

Pacheco, J.A. The “new normal” in education. Prospects 51 , 3–14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09521-x

Download citation

Accepted : 23 September 2020

Published : 24 November 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09521-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Humanistic tradition

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Designing the New Normal: Enable, Engage, Elevate, and Extend Student Learning

The pandemic has provided educators with unprecedented opportunities to explore blended learning and identify the practices and approaches that provide real and lasting value for students.

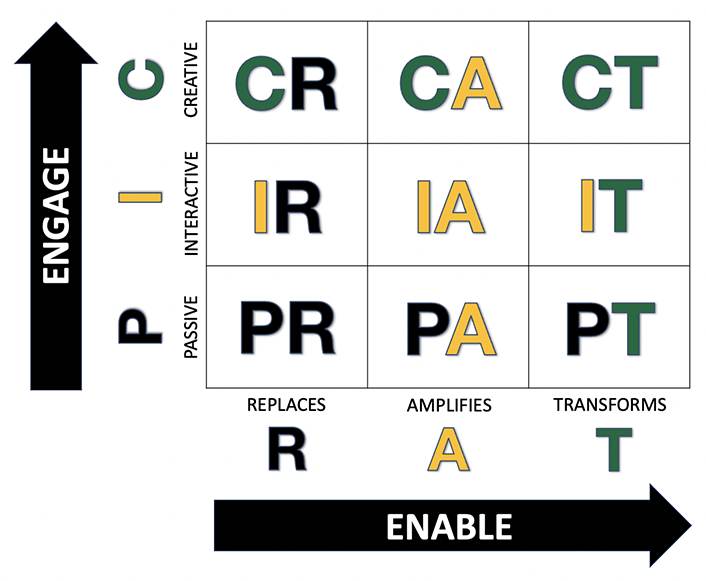

Students and instructors have returned to classrooms on campuses across the country, with a strong desire to rediscover some normalcy following more than a year filled with Zoom meetings and learning apart. At the same time, instructors and students have changed during the pandemic and are coming back to the classroom with new skills and different perspectives. As a result, rather than resuming business as usual, instructors should take inventory of what went well during emergency remote teaching, as well as what they missed most about in-person teaching when they were apart from their students, and begin to blend the two to design the new normal. To help instructors through this process, we have developed a framework to draw their attention to important advantages of blended learning that they should consider as they evaluate what is possible moving forward. Specifically, we have built on previous research and frameworks—such as David Merrill's e 3 approach and Liz Kolb's Triple E Framework Footnote 1 —to develop the 4Es framework (see figure 1) that asks instructors whether their blended learning strategies:

- ENABLE new types of learning activities;

- ENGAGE students in meaningful interactions with others and the course content;

- ELEVATE the learning activities by including real-world skills that benefit students beyond the classroom; and

- EXTEND the time, place, and ways that students can master learning objectives.

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies ENABLE New Types of Learning Activities?

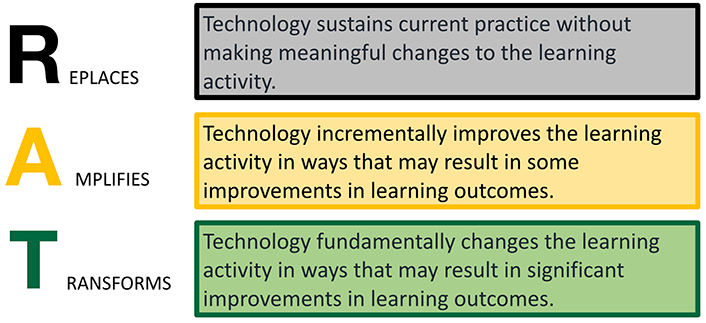

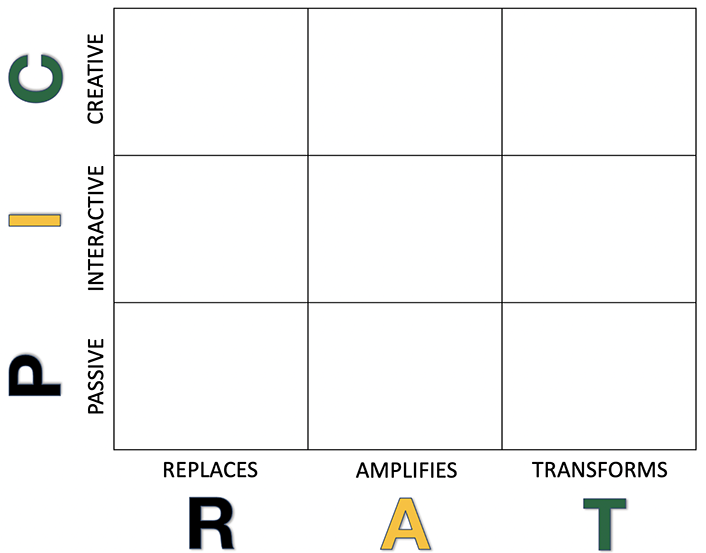

Royce Kimmons, Charles Graham, and Richard West used the RAT framework to explain that blended learning strategies can use technology in ways that replace, amplify, or transform learning activities (see figure 2). Footnote 2

Instructors have a long history of using technology to simply replace or digitize learning activities that were previously done without technology. For example:

- In-person lectures are replaced with Zoom lectures.

- Writing an essay by hand is replaced by typing an essay.

- Writing on a chalkboard is replaced by writing on a digital whiteboard.

- Chalk on a board is replaced by pixels on a screen.

- Reading a textbook is replaced by reading an e-book.

These replacements can be a fine use of technology. Digitizing learning activities can reduce costs and improve access. Additionally, replacing a learning activity by using technology can make some learning activities more efficient than they would be without technology. For instance, an essay typed in a word processor can be revised more easily and quickly than a handwritten essay. However, simply replacing an activity will not improve learning outcomes. In a best-case scenario, students will achieve the same learning outcomes, only more quickly and/or cheaply.

To enable new types of learning that improve learning outcomes, instructors need to use blended learning strategies that move beyond replacing in-person activities with online activities to using strategies that amplify or transform learning activities from what could be accomplished without technology.

Amplifying a learning activity requires instructors to introduce technology in ways that enable incremental improvements, even as the core of the activity remains largely unchanged. For instance, when they read students' essays, instructors may find that many of their students have met the target learning outcomes. As a result, the instructors may choose to amplify the essay-writing process by having students work in a shared document that enables better collaborative opportunities, peer reviews, instructor feedback, and editing. Students can also include multimedia elements to enhance what is written in the essay. Or instructors might use technology to allow students to publish and share their essays in authentic ways. Instructors might also use technology to improve pre-writing activities by engaging students in an online discussion activity to brainstorm and formulate ideas for their essays. What's important to recognize is that although the core activity—writing an essay—remains the same, technology enables incremental improvements, some of which could impact learning outcomes.

Transforming a learning activity is different from amplifying because the goal isn't to improve the activity but to use blended learning strategies in ways that introduce a new learning activity that wouldn't be possible without technology. For instance, rather than making improvements to the essay, instructors could choose to transform the learning activity by tasking students with writing a script, editing a video, and "premiering" their videos to those in the course and others who are invited to participate.

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies ENGAGE Students in Meaningful Interactions with Others and the Course Content?

"Engagement" is a term that is used frequently to mean a lot of different things. A 2020 review of research identified three dimensions of engagement: Footnote 3

- Behavioral: the physical behaviors required to complete the learning activity

- Emotional: the positive emotional energy associated with the learning activity

- Cognitive: the mental energy that a student exerts toward the completion of the learning activity

Instructors often refer to these three dimensions of engagement when they talk about engaging students' hands, hearts, and heads (see figure 3).

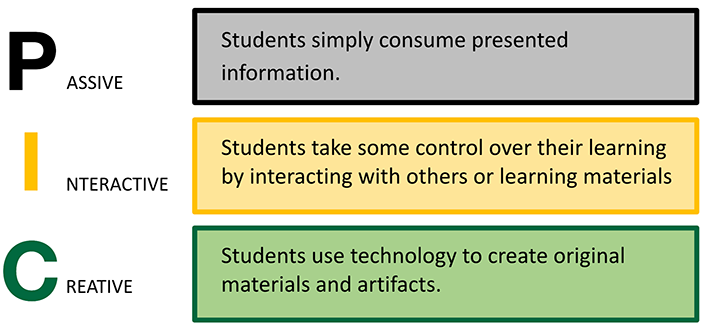

Of the three dimensions of engagement, behavioral engagement is the easiest to observe and categorize. Specifically, Kimmons, Graham, and West used the PIC framework to identify three types of behavioral engagement: passive, interactive, and creative (see figure 4). Footnote 4

Passive learning examples include students watching a video, listening to a podcast, and attending a lecture. In some ways, these passive learning tasks represent a lack of engagement because they don't require or even allow students to make meaningful contributions to the learning activity.

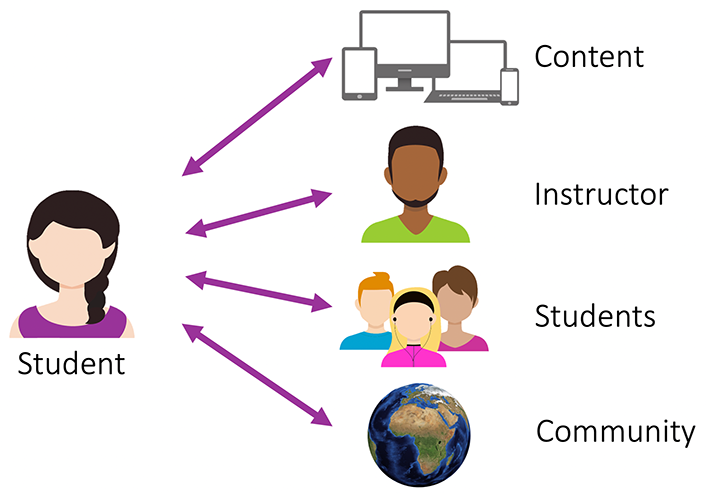

Interactive activities are dynamic and require students to actively participate. Interactive activities include tasks in which students interact with online content and tools. Interactive activities can also include opportunities for students to communicate with others such as the instructor, other students, and those outside the classroom (see figure 5).

Creative activities go beyond participation to actually creating something original such as a blog post, edited video, or website. Table 1 identifies some additional examples of online passive, interactive, and creative activities.

Table 1. Examples of Passive, Interactive, and Creative Activities

| Passive | Interactive | Creative |

|---|---|---|

It's important to note that each type of behavioral engagement is important at different stages of the learning process. For instance, students may passively listen to a short lecture or watch a video before interacting with their peers regarding their thoughts about what they learned during the passive activity. Similarly, if students are tasked with creating a video essay, they will likely start with passive activities to develop a background understanding of the topic or to learn how to use the video-editing program. Students could then interact with their peers to collaboratively create the video. Instructors can also consider when and where passive learning activities occur. For example, sometimes a flipped classroom requires having a passive video-watching experience online to make time and space for an interactive/creative learning experience in person.

An important part of evaluating your blended teaching is to see the value of passive learning activities while also understanding that these types of activities are limited in terms of deepening students' learning. Passive activities such as watching a video or reading an article alone do not require students to demonstrate their comprehension of content or encourage higher levels of cognitive engagement, such as applying, evaluating, or creating. Because too much time spent in passive learning activities will limit students' engagement, instructors should be sure to leave ample time for interactive and creative activities.

Kimmons, Graham, and West combined the PIC and RAT frameworks to form the PICRAT framework and matrix, which allow instructors to chart how technology is being used in their blended learning strategies. Footnote 5 Figure 6 is an adaptation of Kimmons, Graham, and West's original matrix. The matrix is a helpful tool for instructors to consider what the technology adds to the activity and how students are interacting with that technology. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the technology being used to increase student engagement by making learning activities more interactive and/or creative?

- Is the technology being used simply to replace activities or to amplify and transform them?

When planning new blended or online activities, we recommend starting by focusing on the learning objective(s) and then pulling out a piece of paper or pulling up a word processing document and filling out the PICRAT matrix (see figure 7) with various ways that technology could be used to teach the learning objective(s).

Moving up and across the matrix will likely improve the learning activity by leveraging technology to make the experience more interactive or engaging and introducing new ways of learning, but note that the PICRAT matrix doesn't actually measure the quality of the learning activity. Instructors could transform a learning activity by having students create something that wouldn't be possible without technology, but that change might not actually improve students' learning or experience. In fact, students' learning can be transformed for the worse. For instance, using the example shared above, an instructor could transform an essay writing activity so that students create an edited video instead. Although this change may be positive for many students, some students might detest making an edited video and refuse to participate. Similarly, an instructor might transform a passive learning activity into a creative learning activity that isn't as aligned to the learning outcomes. As a result, when amplifying or transforming a learning activity to increase students' behavioral engagement, consider the other two dimensions of engagement—emotional engagement and cognitive engagement. Students will perceive the activity as "busy work" if instructors only engage their hands but fail to also engage their hearts and minds (see figure 8).

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies ELEVATE the Learning Activities to Include Real-World Skills That Benefit Students Beyond the Classroom?

In addition to creating learning activities aligned with the course learning objectives, blended learning strategies can elevate students' learning to also include real-world skills that benefit students beyond the classroom. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Learning stresses the need for students to develop the 4Cs—communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity skills. Footnote 6 While widely referenced and important, the 4Cs model takes a somewhat narrow view of the skills that students need to succeed beyond the classroom. For Ontario's education agenda, Michael Fullan expanded on the 4Cs to include character education and citizenship. Footnote 7 Social-emotional learning is also critical for human development. These skills are best developed in a social learning environment. Of course, students are unable to develop communication, collaboration, and citizenship skills in isolation. Even critical thinking and creativity skills are best developed when working with others. This reality provides more support for balancing passive activities with interactive and creative activities while urging instructors to elevate their instruction.

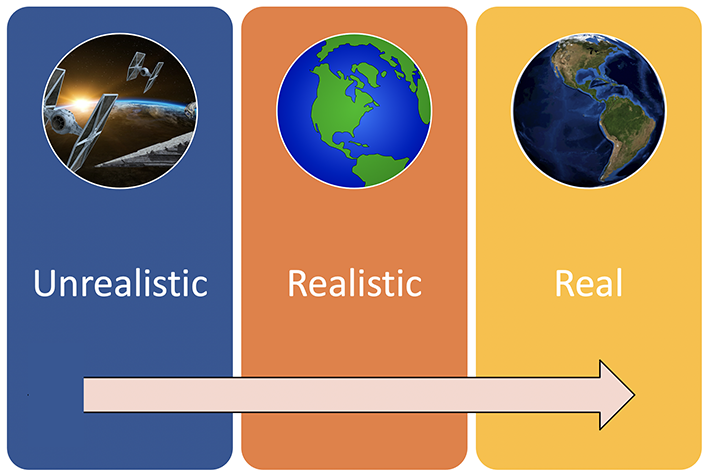

Learning activities are also best elevated when they are situated in authentic tasks and projects. Three levels of authenticity should be considered when choosing the problems students will be working on and the stakeholders that students will be working with (see figure 9):

- Unrealistic: These scenarios and problems can be out of this world—literally! Stakeholders and problems can be science fiction and include anything from time traveling to establishing a colony on Mars. They are intended to make the unit more exciting and emotionally engaging while still requiring students to demonstrate important knowledge and real-world skills.

- Realistic: These are scenarios and problems that feel like they are real but aren't. Real people can even serve as stakeholders, but they are just acting. For example, students might simulate creating a new business by coming up with a new product and working in groups to come up with the name of the product, a business plan, and a marketing plan. It is completely realistic, but they won't be really starting a new business.

- Real: This is the gold standard because you have real people who are genuinely interested in students' work and will benefit from it. These stakeholders can be of any age and in or out of the institution. For example, pre-service instructors in a course on teaching with technology may collaborate to develop a workshop on blended teaching for a local school district. Art students could also curate an actual art gallery showcasing works from local artists.

Authentic assessments are often renewable rather than disposable. As David Wiley explained, "A 'renewable assessment' differs in that the student's work won't be discarded at the end of the process, but will instead add value to the world in some way." Footnote 8 Consider the target audience of most assessments—for whom are students completing assessments? Themselves? Their community? The instructor? Often assessments are completed for an audience of one, the instructor. The instructor then evaluates the assessment, provides the student with some feedback, returns the assessment to the student, and hopes that the feedback enriches the student's learning before the assessment is thrown in the physical or digital trash can. David Wiley referred to these assessments as disposable assessments . They are meant to be used and then discarded without retaining any real-world value.

A movement toward assessments that can exist in a world larger than the four walls of a singular classroom can make learning more authentic and elevate what students learn and do beyond the content-based curriculum and contexts. For example, a community college instructor who worked with one of the authors found that having her students write an openly licensed textbook that would be shared with other students instead of traditional essays prompted them to submit higher quality work than they previously had. Students want to know that their work matters and is destined for more than the nearest trash can (see table 2 and the sidebar "Additional Resources about Assessments").

Table 2. Examples of Renewable and Disposable Assessments

| Renewable Assessments | Disposable Assessments |

|---|---|

Additional Resources about Assessments

Christina Hendricks, "Renewable Assignments: Student Work Adding Value to the World," Flexible Learning , University of British Columbia, October 29, 2015.

Christina Hendricks, "Non-Disposable Assignments in Intro to Philosophy," You're the Teacher , University of British Columbia, August 18, 2015.

"From Consumer to Creator: Students as Producers of Content," Flexible Learning , University of British Columbia, February 18, 2015.

David Wiley, "What Is Open Pedagogy," Improving Learning , October 21, 2013.

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies EXTEND the Time, Place, and Ways That Students Can Master Learning Objectives?

Another way that blended learning strategies can improve learning activities is by extending the time, location, and ways that students can complete them. Attempting to extend students' learning time and location is nothing new. For instance, students have long had flexibility in the time and location that they completed assignments. However, too often students are tasked with completing assignments outside class without adequate support, resulting in frustration and stress.

Using technology, instructors can not only provide students with more sensory-rich learning materials, but, within a learning management system (LMS), they can also provide digital scaffolding and direction to successfully complete learning activities using those materials. For instance, it is relatively easy for instructors to create short instructional videos that can help students learn new concepts or complete learning tasks. Kareem Farah explained that creating instructional videos allowed him to "clone" himself so students could receive his help the moment they needed it, not when he was presently available to help them. Footnote 9 Once instructors feel comfortable making quick videos, they can use them to provide targeted support anytime students find something confusing or difficult. This allows instructors to tailor lessons to specific students or course sections.

Instructors can also extend the ways in which students complete learning activities. For instance, instructors might provide multiple learning paths for students to choose from. Creating multiple activities that all lead toward mastery of learning objectives allows students choice in the learning path—hopefully with choices that will motivate them and inspire them to do their best work. Once learning has been extended, instructors can also provide students with opportunities to form their own learning path and/or set their own learning goals. The taxonomy of learner agency presents a scaffold for moving students from a "one size fits all" learning approach to an instructional approach that provides learners with guided choices for their own learning. Footnote 10 These choices could include setting performance or learning behavior goals related to learning objectives, choosing how to demonstrate learning and understanding, or choosing specific resources to use or topics to study within a given learning objective. At the highest levels of extending learner autonomy, learners may even create their own learning outcomes, assessments, and activities related to the goals of a course.

Combining in-person and online instruction doesn't mean that the blended learning will be high quality—or even good. As you begin to blend your students' learning, you will likely find that some lessons or even entire instructional units don't work as well as expected. The opposite will also be true, however, and you will find that some blended lessons and modules go incredibly well. It's important to carefully evaluate what works and what needs to be improved or even replaced. A J-curve should be expected anytime instructors try something new. Footnote 11 The 4Es framework can help you recognize quality blended teaching and learning. Specifically, as you plan new blended instructional units or evaluate previous blended instruction, ask if your instructional unit would or did:

- ENABLE new types of learning activities?

- ENGAGE students in meaningful interactions with others and the course content?

- ELEVATE the learning activities by including real-world skills that benefit students beyond the classroom?

- EXTEND the time, place, and ways that students can master learning objectives?

- M. David Merrill, "Finding e³ (effective, efficient, and engaging) Instruction," Educational Technology 49, no. 3 (May–June 2009): 15–26; Liz Kolb, Triple E Framework . Jump back to footnote 1 in the text. ↩

- Royce Kimmons, Charles R. Graham, and Richard E. West, "The PICRAT Model for Technology Integration in Teacher Preparation," Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 20, no. 1 (2020). Jump back to footnote 2 in the text. ↩

- Jered Borup, Charles R. Graham, Richard E. West, Leanna Archambault, and Kristian J. Spring, "Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning," Educational Technology Research and Development 68 (February 14, 2020): 807–32. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text. ↩

- Kimmons, Graham, and West, "The PICRAT Model." Jump back to footnote 4 in the text. ↩

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text. ↩

- See "P21 Framework Definitions." Jump back to footnote 6 in the text. ↩

- Michael Fullan, Great to Excellent: Launching the Next Stage of Ontario's Education Agenda , Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text. ↩

- David Wiley, "Toward Renewable Assessments," Improving Learning , July 7, 2016. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text. ↩

- Kareem Farah, "Blended Learning Built on Teacher Expertise," Edutopia , May 9, 2019. Jump back to footnote 9 in the text. ↩

- Charles R. Graham , Jered Borup, Michelle A. Jensen, Karen T. Arnesen, and Cecil R. Short, "K–12 Blended Teaching Competencies," (Provo, UT: EdTechBooks.org, 2021). Jump back to footnote 10 in the text. ↩

- Charles R. Graham, Jered Borup, Cecil R. Short, and Leanna Archambault, K–12 Blended Teaching: A Guide to Personalized Learning and Online Integration (Provo, UT: EdTechBooks.org, 2019). See, specifically, section 6.5 of "Blended Design in Practice." Jump back to footnote 11 in the text. ↩

Jered Borup is an Associate Professor in the Division of Learning Technologies at George Mason University.

Charles R. Graham is a Professor in the Department of Instructional Psychology and Technology at Brigham Young University.

Cecil Short is an Assistant Professor of Practice of Blended and Personalized Learning in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Texas Tech University.

Joan Kang Shin is an Associate Professor in the Division of Advanced Professional Teacher Development and International Education at George Mason University.

© 2022 Jered Borup, Charles R. Graham, Cecil Short, and Joan Kang Shin. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jeff Clyde G Corpuz, Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19, Journal of Public Health , Volume 43, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages e344–e345, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab057

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

To live in the world is to adapt constantly. A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. 1 Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. 2 However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

The term ‘new normal’ first appeared during the 2008 financial crisis to refer to the dramatic economic, cultural and social transformations that caused precariousness and social unrest, impacting collective perceptions and individual lifestyles. 3 This term has been used again during the COVID-19 pandemic to point out how it has transformed essential aspects of human life. Cultural theorists argue that there is an interplay between culture and both personal feelings (powerlessness) and information consumption (conspiracy theories) during times of crisis. 4 Nonetheless, it is up to us to adapt to the challenges of current pandemic and similar crises, and whether we respond positively or negatively can greatly affect our personal and social lives. Indeed, there are many lessons we can learn from this crisis that can be used in building a better society. How we open to change will depend our capacity to adapt, to manage resilience in the face of adversity, flexibility and creativity without forcing us to make changes. As long as the world has not found a safe and effective vaccine, we may have to adjust to a new normal as people get back to work, school and a more normal life. As such, ‘we have reached the end of the beginning. New conventions, rituals, images and narratives will no doubt emerge, so there will be more work for cultural sociology before we get to the beginning of the end’. 5

Now, a year after COVID-19, we are starting to see a way to restore health, economies and societies together despite the new coronavirus strain. In the face of global crisis, we need to improvise, adapt and overcome. The new normal is still emerging, so I think that our immediate focus should be to tackle the complex problems that have emerged from the pandemic by highlighting resilience, recovery and restructuring (the new three Rs). The World Health Organization states that ‘recognizing that the virus will be with us for a long time, governments should also use this opportunity to invest in health systems, which can benefit all populations beyond COVID-19, as well as prepare for future public health emergencies’. 6 There may be little to gain from the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is important that the public should keep in mind that no one is being left behind. When the COVID-19 pandemic is over, the best of our new normal will survive to enrich our lives and our work in the future.

No funding was received for this paper.

UNESCO . A year after coronavirus: an inclusive ‘new normal’. https://en.unesco.org/news/year-after-coronavirus-inclusive-new-normal . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

Cordero DA . To stop or not to stop ‘culture’: determining the essential behavior of the government, church and public in fighting against COVID-19 . J Public Health (Oxf) 2021 . doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab026 .

Google Scholar

El-Erian MA . Navigating the New Normal in Industrial Countries . Washington, D.C. : International Monetary Fund , 2010 .

Google Preview

Alexander JC , Smith P . COVID-19 and symbolic action: global pandemic as code, narrative, and cultural performance . Am J Cult Sociol 2020 ; 8 : 263 – 9 .

Biddlestone M , Green R , Douglas KM . Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 . Br J Soc Psychol 2020 ; 59 ( 3 ): 663 – 73 .

World Health Organization . From the “new normal” to a “new future”: A sustainable response to COVID-19. 13 October 2020 . https: // www.who.int/westernpacific/news/commentaries/detail-hq/from-the-new-normal-to-a-new-future-a-sustainable-response-to-covid-19 . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2021 | 331 |

| April 2021 | 397 |

| May 2021 | 1,112 |

| June 2021 | 1,714 |

| July 2021 | 1,767 |

| August 2021 | 1,638 |

| September 2021 | 3,977 |

| October 2021 | 8,281 |

| November 2021 | 6,445 |

| December 2021 | 4,287 |

| January 2022 | 6,424 |

| February 2022 | 7,286 |

| March 2022 | 8,709 |

| April 2022 | 7,282 |

| May 2022 | 7,307 |

| June 2022 | 5,175 |

| July 2022 | 2,404 |

| August 2022 | 2,940 |

| September 2022 | 7,021 |

| October 2022 | 7,134 |

| November 2022 | 5,171 |

| December 2022 | 3,236 |

| January 2023 | 3,796 |

| February 2023 | 3,344 |

| March 2023 | 4,316 |

| April 2023 | 2,826 |

| May 2023 | 3,263 |

| June 2023 | 1,742 |

| July 2023 | 988 |

| August 2023 | 1,592 |

| September 2023 | 2,701 |

| October 2023 | 1,847 |

| November 2023 | 1,354 |

| December 2023 | 865 |

| January 2024 | 1,025 |

| February 2024 | 1,232 |

| March 2024 | 1,257 |

| April 2024 | 1,169 |

| May 2024 | 902 |

| June 2024 | 519 |

| July 2024 | 666 |

| August 2024 | 1,086 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Here are the steps you can follow to write an essay about education for the new normal: Introduction: Write an engaging introduction that provides background information about the new normal in education and presents your thesis statement. Grab the reader's attention and set the tone for the essay. Body paragraphs: Develop the main points of ...

The new normal in education invites us to reevaluate traditional methods, explore diverse learning modalities, and prioritize adaptability to prepare students for an ever-changing future. This transformative period challenges us to build a more inclusive and equitable educational system, ensuring that every learner can thrive in the face of ...

Education on new normal. The vision of secular capitalistic education, unclear curriculum directions, rigid learning methods, very minimal and uneven support for facilities and infrastructure, makes education in the midst of a pandemic feel so burdensome. Good for students, parents, as well as educators and schools.

This essay aims to provide an informative overview of this new educational paradigm and its impact on students, teachers, and institutions. Paragraph 1: Defining the New Normal Education The New Normal Education refers to the shift towards remote or hybrid learning models in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The New Normal for Students and Schools. In the middle of a pandemic, it's impossible to set expectations. We had deadlines when this all started, and they were either reached or not. Sticking to deadlines was already a hard and quick guideline for some high school teachers and college professors when the pandemic started.

Answer: Everyone of us is new with the life we have now. Having this new normal changed our lives and routines. The education setting was already been in online but sad to say not all of us has the privilege to attain this way of learning. During this time we've all realized how hard life is. We've learned a lot of things.

This pandemic has drastically changed the education landscape and revealed old and new challenges such as the digital divide (Altbach and De Wit, 2020; HESB, 2020) — a term coined for lack of ...

The new normal. The pandemic ushers in a "new" normal, in which digitization enforces ways of working and learning. It forces education further into technologization, a development already well underway, fueled by commercialism and the reigning market ideology. Daniel ( 2020, p.

A 2020 review of research identified three dimensions of engagement: 3. Behavioral: the physical behaviors required to complete the learning activity. Emotional: the positive emotional energy associated with the learning activity. Cognitive: the mental energy that a student exerts toward the completion of the learning activity.

Sun.Star Pampanga. My Reflection in the New Normal Education. 2021-01-26 -. Rico Jay C. Mananquil. Much has been written about the new normal in the society as the COVID-19 Pandemic continues to spread in different countries around the world. The new normal will involve higher levels of health precautions.

First things first, the who of education are entities that need to transform themselves. The learning-from-home mode has abruptly changed the roles of teachers, students and parents. The need for autonomous learning requires that teachers shift to be designers and facilitators of learning instead of the sage on the stage.

This essay explores education due to the "new normal," examining the shifts in teaching and learning methods, the impact of technology, and the importance of adapting to the changing educational landscape.. Here are the steps you can follow to write an essay about education for the new normal: Introduction: Write an engaging introduction that provides background information about the new ...

New normal education essay - 16802937. answered New normal education essay See answers Advertisement Advertisement maeeechan maeeechan Learning in the new normal is a challenge for the teachers, students and even parents. After postponing the opening of online classes last August 24, DepEd now confirms that they are ready for October's ...

The academic landscape has changed globally post-pandemic. Students now have to adapt to the new normal education in the Philippines. According to the 2022 State of Student Success and Engagement in Higher Education, a global study from education technology firm Instructure, 76% of respondents from the Philippines want to take their courses in a combination of in-person and online classes.