The Best Essay Films, Ranked

Your changes have been saved

Email is sent

Email has already been sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

Sergio Leone Turned down The Godfather to Work on a Famous Flop Instead

20 of mike flanagan's favorite horror movies (picked from his letterboxd account), 13 cult classic movies you can stream for free.

In literature, an essay is a composition dealing with its subject from a personal point of view. The pioneer of this genre, 16th-century French writer and philosopher Michel de Montaigne, used the French word "essai" to describe his "attempts" to put subjective thoughts into writing. Deriving its name from Montaigne’s magnum opus Essays and the literary genre in general, essay films are defined as a self-reflexive form of avant-garde, experimental, sort of documentary cinema that can be traced back to the dawn of filmmaking.

From early silent essay films, like D. W. Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera , to in-depth explorations from the second half of the 20th century, these are some of the best essay films ever made, ranked.

8 A Corner in Wheat

The 14-minute short A Corner in Wheat (1909) is considered by many to be the world's earliest essay film. Directed by filmmaking pioneer D. W. Griffith, this shot follows a ruthless tycoon who wants to control the wheat market. A powerful portrayal of capitalistic greed , A Corner in Wheat is a bold commentary on the contrast between the wealthy speculators and the agricultural poor. It is simply one of the best early short films.

7 Two or Three Things I Know About Her

Described by MUBI as "a landmark transition from the maestro’s jazzy genre deconstructions of the 60s to his gorgeous and inquisitive essay films of the future" (such as Histoire(s) du cinéma , Goodbye to Language , The Image Book ), 1967's Two or Three Things I Know About Her is Jean-Luc Godard’s collage of modern life.

Related: The Best Jean-Luc Godard Films, Ranked

The story of 24 hours in the life of housewife Juliette (Marina Vlady), who moonlights as a prostitute, is only a template for the filmmaker’s social observation of 1960s France, sprinkled with references to the nightmares of the Vietnam War. Whispering in our ears as narrator, Godard tells us much more than two or three things about "her," referring to Paris rather than Juliette.

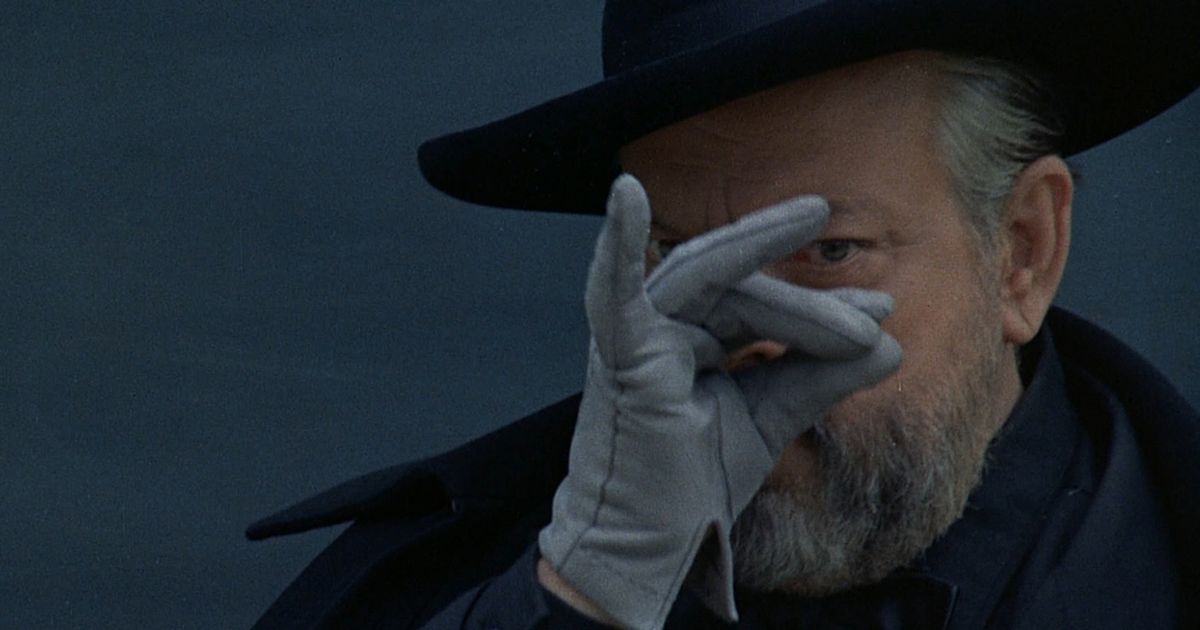

6 F for Fake

Orson Welles’ 1973 essay film F for Fake focuses on three hoaxers, the notorious art forger Elmyr de Hory who had a talent for copying styles of noted painters; his biographer Clifford Irving whose fake "authorized biography" of Howard Hughes was one of the biggest literary scandals of the 20th century; and Welles himself with his famous War of the Worlds hoax. One of the best Orson Welles films , F for Fake investigates the tenuous lines between forgery and art, illusion and life.

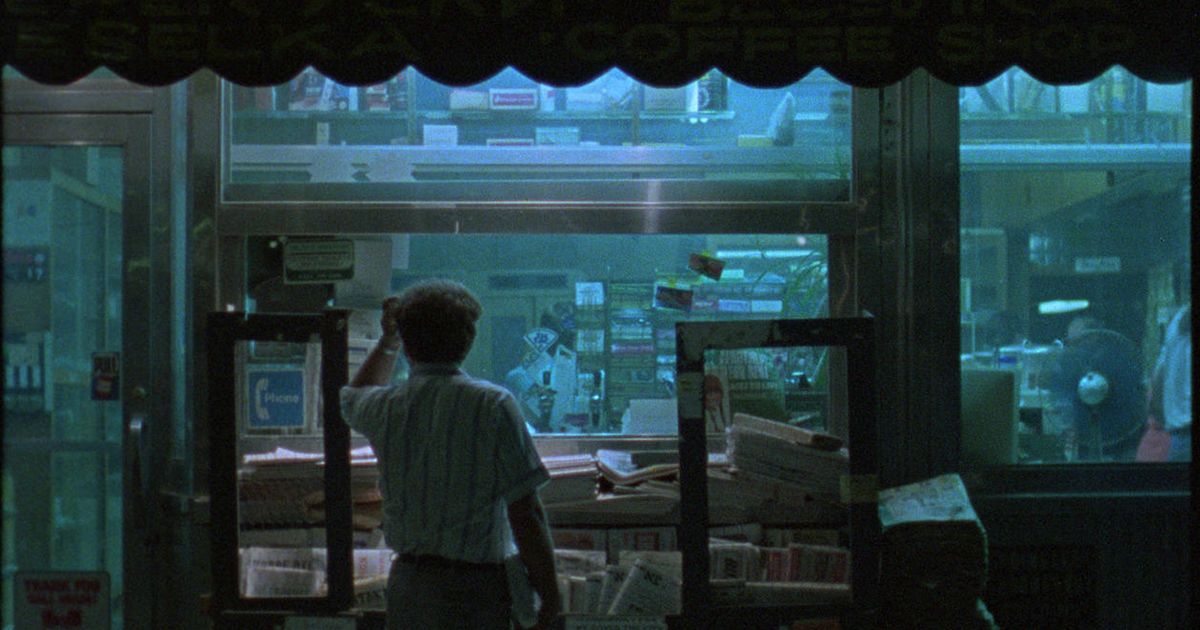

5 News from Home

An unforgettable time capsule of New York in the 1970s, News from Home features Belgian film director Chantal Akerman reading melancholic, sometimes passive-aggressive letters from her mother over beautiful shots of New York, where Akerman relocated at the age of 21. Released in 1976, after the filmmaker’s breakthrough drama Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles , News from Home makes plain the disconnection in family, while New York and the young artist’s alienating come more and more to the front.

4 As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

Jonas Mekas, the godfather of American avant-garde cinema, made one of the most personal, but at the same time one of the most universal films ever. It is his 2000 experimental documentary As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty . Compiled from Mekas' home movies from 1970-1999, this nearly five-hour essay film shows the loveliness of everyday life. Footage of what Mekas calls "little fragments of paradise," the first steps of the filmmaker’s children, their happy life in New York, trips to Europe, and on and on, are complemented by Mekas’ commentary. It is a poetic diary about nothing but life.

3 Sans Soleil

Directed by Chris Marker, king of the essay film , 1983’s Sans Soleil ( Sunless ) follows an unseen cameraman named Sandor Krasna, Marker's alter ego, who journeys from Africa to Japan, "two extreme poles of survival." The 100-minute poetical collage of Marker’s original documentary footage, clips from films and television, sequences from other filmmakers, and stock videos comes complete with the voice of a nameless female narrator, who reads Krasna's letters that sum up his lifetime's travels.

Like Marker's French New Wave masterpiece La Jetee , Sans Soleil reflects on human experience, the nature of memory, understanding of time, and life on our planet. It is pure beauty.

Made when the filmmaker, Derek Jarman, was dying from AIDS-related complications that rendered him partially blind and capable only of experiencing shades of blue, the great experimental film Blue from 1993 is like no other. Jarman’s 79-minute final feature consists of a single shot of one color — International Klein Blue. Against a blank blue screen, the iconic director interweaves a medley of sounds, music, voices of four narrators (Jarman himself, the chameleonic Tilda Swinton , Nigel Terry, and John Quentin), the filmmaker’s daydreams, adventures of Blue, as a character and color, diary-like entries about Jarman’s life and current events, names of his lovers and friends who had died of AIDS, fragments of poetry, and much more.

Related: 8 Must-Watch Movies From LGBTQ+ Filmmakers

A deeply personal goodbye and a sort of self-portrait, this essay film is dedicated to Yves Klein , the artist who mixed this deep blue hue and said, "At first there is nothing, then there is a profound nothingness, after that a blue profundity".

1 Man with a Movie Camera

Dziga Vertov, one of cinema’s greatest innovators, believed that the "eye" of the camera captures life better than the subjective eye of a human. In the 1920s, he started looking for cinematic truth, showing life outside the field of human vision through a mix of rhythmic editing, multiple exposures, experimental camera angles, backward sequences, freeze frames, extreme close-ups, and other "cinema eye" techniques. This is how Vertov’s best-known film, 1929’s Man with a Movie Camera , was made. This narrative-free essay shows the kaleidoscopic life of Soviet cities. An avant-garde urban poem, Man with a Movie Camera makes clear what the beauty of cinema is.

- Movie Lists

Film Analysis: Example, Format, and Outline + Topics & Prompts

Films are never just films. Instead, they are influential works of art that can evoke a wide range of emotions, spark meaningful conversations, and provide insightful commentary on society and culture. As a student, you may be tasked with writing a film analysis essay, which requires you to delve deeper into the characters and themes. But where do you start?

In this article, our expert team has explored strategies for writing a successful film analysis essay. From prompts for this assignment to an excellent movie analysis example, we’ll provide you with everything you need to craft an insightful film analysis paper.

- 📽️ Film Analysis Definition

📚 Types of Film Analysis

- ✍️ How to Write Film Analysis

- 🎞️ Movie Analysis Prompts

- 🎬 Top 15 Topics

📝 Film Analysis Example

- 🍿 More Examples

🔗 References

📽️ what is a film analysis essay.

A film analysis essay is a type of academic writing that critically examines a film, its themes, characters, and techniques used by the filmmaker. This essay aims to analyze the film’s meaning, message, and artistic elements and explain its cultural, social, and historical significance. It typically requires a writer to pay closer attention to aspects such as cinematography, editing, sound, and narrative structure.

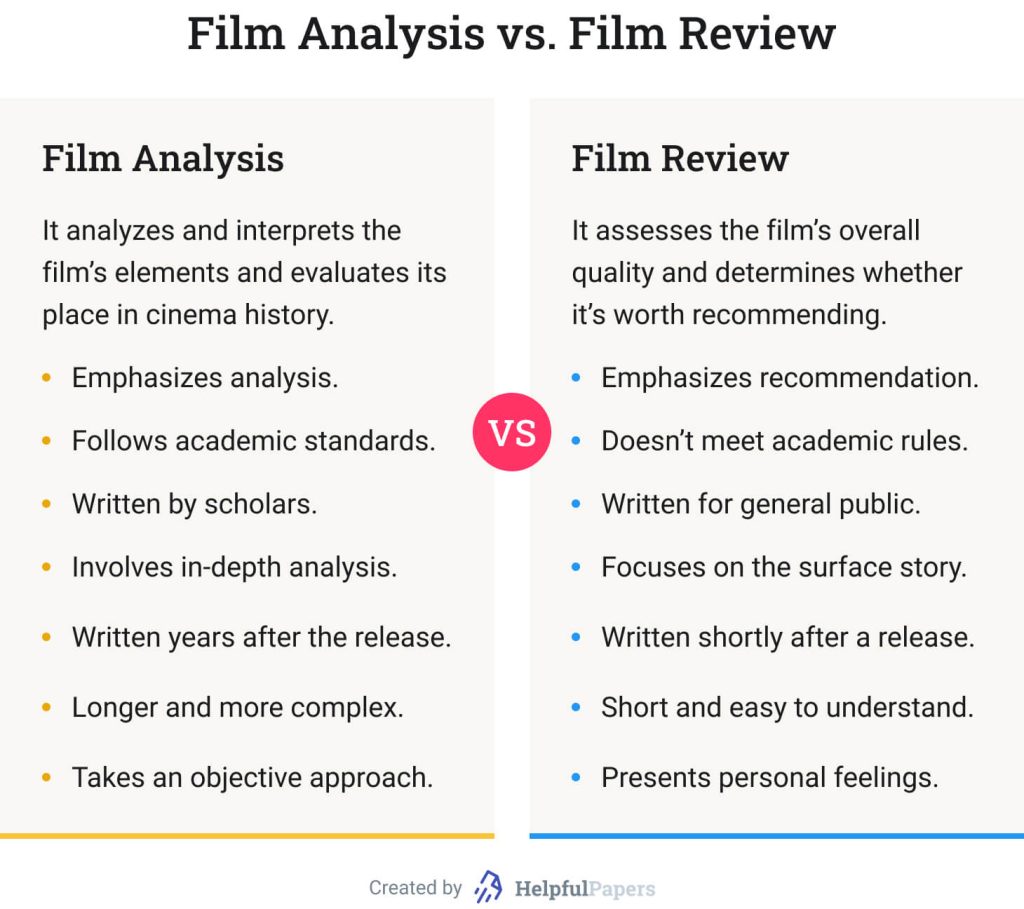

Film Analysis vs Film Review

It’s common to confuse a film analysis with a film review, though these are two different types of writing. A film analysis paper focuses on the film’s narrative, sound, editing, and other elements. This essay aims to explore the film’s themes, symbolism , and underlying messages and to provide an in-depth interpretation of the film.

On the other hand, a film review is a brief evaluation of a film that provides the writer’s overall opinion of the movie. It includes the story’s short summary, a description of the acting, direction, and technical aspects, and a recommendation on whether or not the movie is worth watching.

Wondering what you should focus on when writing a movie analysis essay? Here are four main types of film analysis. Check them out!

| Focuses on the story and how it is presented in the film, including the plot, characters, and themes. This type of analysis looks at how the story is constructed and how it is conveyed to the audience. | |

| Examines the symbols, signs, and meanings created through the film’s visuals, such as color, lighting, and . It analyzes how the film’s visual elements interact to create a cohesive message. | |

| Looks at the cultural, historical, and social context in which the film was made. This type of analysis considers how the film reflects the values, beliefs, and attitudes of its time and place and responds to broader cultural and social trends. | |

| Studies the visual elements of a film, including the setting, costumes, and actors’ performances, to understand how they contribute to the film’s overall meaning. These are analyzed within a scene or even a single shot. |

📋 Film Analysis Format

The movie analysis format follows a typical essay structure, including a title, introduction, thesis statement, body, conclusion, and references.

The most common citation styles used for a film analysis are MLA and Chicago . However, we recommend you consult with your professor for specific guidelines. Remember to cite all dialogue and scene descriptions from the movie to support the analysis. The reference list should include the analyzed film and any external sources mentioned in the essay.

When referring to a specific movie in your paper, you should italicize the film’s name and use the title case. Don’t enclose the title of the movie in quotation marks.

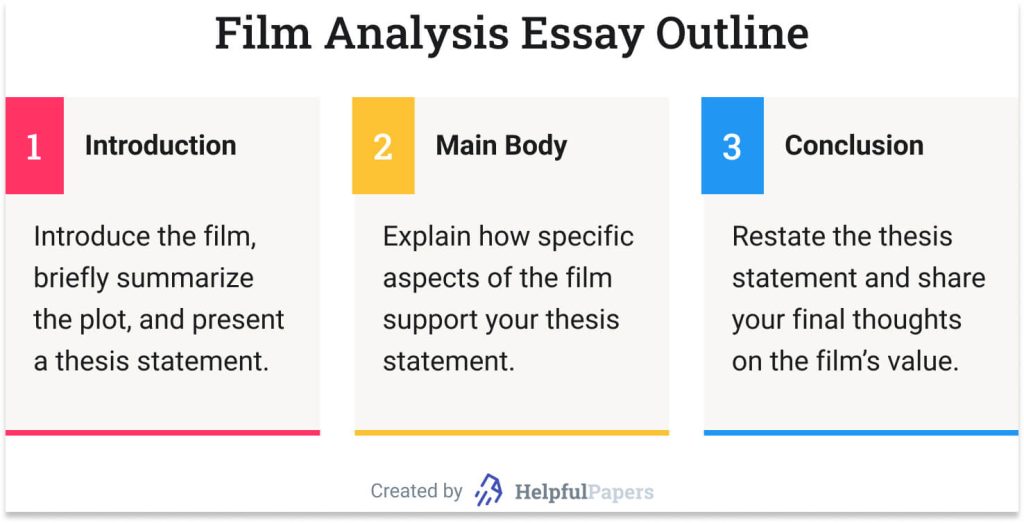

📑 Film Analysis Essay Outline

A compelling film analysis outline is crucial as it helps make the writing process more focused and the content more insightful for the readers. Below, you’ll find the description of the main parts of the movie analysis essay.

Film Analysis Introduction

Many students experience writer’s block because they don’t know how to write an introduction for a film analysis. The truth is that the opening paragraph for a film analysis paper is similar to any other academic essay:

- Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention . For example, it can be a fascinating fact or a thought-provoking question related to the film.

- Provide background information about the movie . Introduce the film, including its title, director, and release date. Follow this with a brief summary of the film’s plot and main themes.

- End the introduction with an analytical thesis statement . Present the central argument or interpretation that will be explored in the analysis.

Film Analysis Thesis

If you wonder how to write a thesis for a film analysis, we’ve got you! A thesis statement should clearly present your main idea related to the film and provide a roadmap for the rest of the essay. Your thesis should be specific, concise, and focused. In addition, it should be debatable so that others can present a contrasting point of view. Also, make sure it is supported with evidence from the film.

Let’s come up with a film analysis thesis example:

Through a feminist lens, Titanic is a story about Rose’s rebellion against traditional gender roles, showcasing her attempts to assert her autonomy and refusal to conform to societal expectations prevalent in the early 20th century.

Movie Analysis Main Body

Each body paragraph should focus on a specific aspect of the film that supports your main idea. These aspects include themes, characters, narrative devices , or cinematic techniques. You should also provide evidence from the film to support your analysis, such as quotes, scene descriptions, or specific visual or auditory elements.

Here are two things to avoid in body paragraphs:

- Film review . Your analysis should focus on specific movie aspects rather than your opinion of the film.

- Excessive plot summary . While it’s important to provide some context for the analysis, a lengthy plot summary can detract you from your main argument and analysis of the film.

Film Analysis Conclusion

In the conclusion of a movie analysis, restate the thesis statement to remind the reader of the main argument. Additionally, summarize the main points from the body to reinforce the key aspects of the film that were discussed. The conclusion should also provide a final thought or reflection on the film, tying together the analysis and presenting your perspective on its overall meaning.

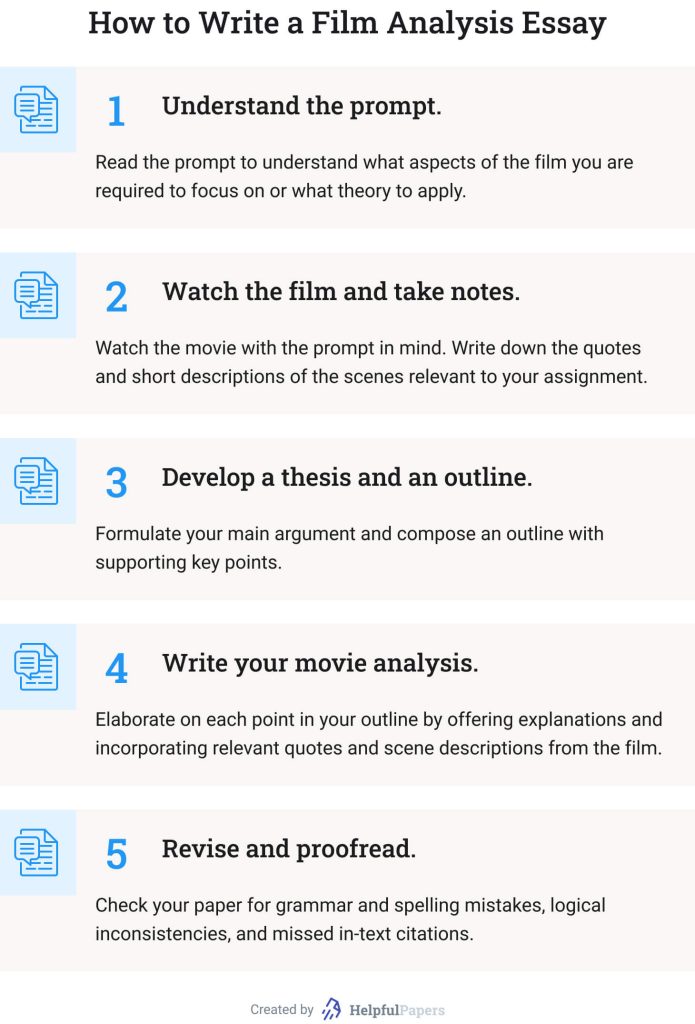

✍️ How to Write a Film Analysis Essay

Writing a film analysis essay can be challenging since it requires a deep understanding of the film, its themes, and its characters. However, with the right approach, you can create a compelling analysis that offers insight into the film’s meaning and impact. To help you, we’ve prepared a small guide.

1. Understand the Prompt

When approaching a film analysis essay, it is crucial to understand the prompt provided by your professor. For example, suppose your professor asks you to analyze the film from the perspective of Marxist criticism or psychoanalytic film theory . In that case, it is essential to familiarize yourself with these approaches. This may involve studying these theories and identifying how they can be applied to the film.

If your professor did not provide specific guidelines, you will need to choose a film yourself and decide on the aspect you will explore. Whether it is the film’s themes, characters, cinematography, or social context, having a clear focus will help guide your analysis.

2. Watch the Film & Take Notes

Keep your assignment prompt in mind when watching the film for your analysis. For example, if you are analyzing the film from a feminist perspective, you should pay attention to the portrayal of female characters, power dynamics , and gender roles within the film.

As you watch the movie, take notes on key moments, dialogues, and scenes relevant to your analysis. Additionally, keeping track of the timecodes of important scenes can be beneficial, as it allows you to quickly revisit specific moments in the film for further analysis.

3. Develop a Thesis and an Outline

Next, develop a thesis statement for your movie analysis. Identify the central argument or perspective you want to convey about the film. For example, you can focus on the film’s themes, characters, plot, cinematography, or other outstanding aspects. Your thesis statement should clearly present your stance and provide a preview of the points you will discuss in your analysis.

Having created a thesis, you can move on to the outline for an analysis. Write down all the arguments that can support your thesis, logically organize them, and then look for the supporting evidence in the movie.

4. Write Your Movie Analysis

When writing a film analysis paper, try to offer fresh and original ideas on the film that go beyond surface-level observations. If you need some inspiration, have a look at these thought-provoking questions:

- How does the movie evoke emotional responses from the audience through sound, editing, character development , and camera work?

- Is the movie’s setting portrayed in a realistic or stylized manner? What atmosphere or mood does the setting convey to the audience?

- How does the lighting in the movie highlight certain aspects? How does the lighting impact the audience’s perception of the movie’s characters, spaces, or overall mood?

- What role does the music play in the movie? How does it create specific emotional effects for the audience?

- What underlying values or messages does the movie convey? How are these values communicated to the audience?

5. Revise and Proofread

To revise and proofread a film analysis essay, review the content for grammatical, spelling, and punctuation errors. Ensure the paper flows logically and each paragraph contributes to the overall analysis. Remember to double-check that you haven’t missed any in-text citations and have enough evidence and examples from the movie to support your arguments.

Consider seeking feedback from a peer or instructor to get an outside perspective on the essay. Another reader can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improvement.

🎞️ Movie Analysis: Sample Prompts

Now that we’ve covered the essential aspects of a film analysis template, it’s time to choose a topic. Here are some prompts to help you select a film for your analysis.

- Metropolis film analysis essay . When analyzing this movie, you can explore the themes of technology and society or the portrayal of class struggle. You can also focus on symbolism, visual effects, and the influence of German expressionism on the film’s aesthetic.

- The Godfather film analysis essay . An epic crime film, The Godfather , allows you to analyze the themes of power and corruption, the portrayal of family dynamics, and the influence of Italian neorealism on the film’s aesthetic. You can also examine the movie’s historical context and impact on future crime dramas.

- Psycho film analysis essay . Consider exploring the themes of identity and duality, the use of suspense and tension in storytelling, or the portrayal of mental illness. You can also explore the impact of this movie on the horror genre.

- Forrest Gump film analysis essay . If you decide to analyze the Forrest Gump movie, you can focus on the portrayal of historical events. You might also examine the use of nostalgia in storytelling, the character development of the protagonist, and the film’s impact on popular culture and American identity.

- The Great Gatsby film analysis essay . The Great Gatsby is a historical drama film that allows you to analyze the themes of the American Dream, wealth, and class. You can also explore the portrayal of the 1920s Jazz Age and the symbolism of the green light.

- Persepolis film analysis essay . In a Persepolis film analysis essay, you can uncover the themes of identity and self-discovery. You might also consider analyzing the portrayal of the Iranian Revolution and its aftermath, the use of animation as a storytelling device, and the film’s influence on the graphic novel genre.

🎬 Top 15 Film Analysis Essay Topics

- The use of color symbolism in Vertigo and its impact on the narrative.

- The moral ambiguity and human nature in No Country for Old Men .

- The portrayal of ethnicity in Gran Torino and its commentary on cultural stereotypes.

- The cinematography and visual effects in The Hunger Games and their contribution to the dystopian atmosphere.

- The use of silence and sound design in A Quiet Place to immerse the audience.

- The disillusionment and existential crisis in The Graduate and its reflection of the societal norms of the 1960s.

- The themes of sacrifice and patriotism in Casablanca and their relevance to the historical context of World War II.

- The psychological horror in The Shining and its impact on the audience’s experience of fear and tension.

- The exploration of existentialism in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind .

- Multiple perspectives and unreliable narrators in Rashomon .

- The music and soundtrack in Titanic and its contribution to the film’s emotional resonance.

- The portrayal of good versus evil in the Harry Potter film series and its impact on understanding morality.

- The incorporation of vibrant colors in The Grand Budapest Hotel as a visual motif.

- The use of editing techniques to tell a nonlinear narrative in Pulp Fiction .

- The function of music and score in enhancing the emotional impact in Schindler’s List .

Check out the Get Out film analysis essay we’ve prepared for college and high school students. We hope this movie analysis essay example will inspire you and help you understand the structure of this assignment better.

Film Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Get Out, released in 2017 and directed by Jordan Peele, is a culturally significant horror film that explores themes of racism, identity, and social commentary. The film follows Chris, a young African-American man, visiting his white girlfriend’s family for the weekend. This essay will analyze how, through its masterful storytelling, clever use of symbolism, and thought-provoking narrative, Get Out reveals the insidious nature of racism in modern America.

Film Analysis Body Paragraphs Example

Throughout the movie, Chris’s character is subject to various types of microaggression and subtle forms of discrimination. These instances highlight the insidious nature of racism, showing how it can exist even in seemingly progressive environments. For example, during Chris’s visit to his white girlfriend’s family, the parents continuously make racially insensitive comments, expressing their admiration for black physical attributes and suggesting a fascination bordering on fetishization. This sheds light on some individuals’ objectification and exotification of black bodies.

Get Out also critiques the performative allyship of white liberals who claim to be accepting and supportive of the black community. It is evident in the character of Rose’s father, who proclaims: “I would have voted for Obama for a third term if I could” (Peele, 2017). However, the film exposes how this apparent acceptance can mask hidden prejudices and manipulation.

Film Analysis Conclusion Example

In conclusion, the film Get Out provides a searing critique of racial discrimination and white supremacy through its compelling narrative, brilliant performances, and skillful direction. By exploring the themes of the insidious nature of racism, fetishization, and performative allyship, Get Out not only entertains but also challenges viewers to reflect on their own biases.

🍿 More Film Analysis Examples

- Social Psychology Theories in The Experiment

- Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader: George Lukas’s Star Wars Review

- Girl, Interrupted : Mental Illness Analysis

- Mental Disorders in the Finding Nemo Film

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest Film: Interpretive Psychological Analysis

- Analysis of Spielberg’s Film Lincoln

- Glory – The Drama Movie by Edward Zwick

- Inventors in The Men Who Built America Series

- Crash Movie: Racism as a Theme

- Dances with Wolves Essay – Movie Analysis

- Superbad by G. Mottola

- Ordinary People Analysis and Maslow Hierarchy of Needs

- A Review of the Movie An Inconvenient Truth by Guggenheim

- Chaplin’s Modern Times and H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau

- Misé-En-Scene and Camera Shots in The King’s Speech

- Children’s Sexuality in the Out in the Dark Film

- Chinese and American Women in Joy Luck Club Novel and Film

- The Film Silver Linings Playbook by Russell

- The Role of Music in the Films The Hours and The Third Man

- The Social Network : Film Analysis

- My Neighbor Totoro : Film by Hayao Miyazaki

- Marriage Story Film Directed by Noah Baumbach

❓ Film Analysis Essay: FAQ

Why is film analysis important.

Film analysis allows viewers to go beyond the surface level and delve into the deeper layers of a film’s narrative, themes, and technical aspects. It enables a critical examination that enhances appreciation and understanding of the film’s message, cultural significance, and artistic value. At the same time, writing a movie analysis essay can boost your critical thinking and ability to spot little details.

How to write a movie analysis?

- Watch the film multiple times to grasp its key elements.

- Take notes on the story, characters, and themes.

- Pay attention to the film’s cinematography, editing, sound, message, symbolism, and social context.

- Formulate a strong thesis statement that presents your main argument.

- Support your claims with evidence from the film.

How to write a critical analysis of a movie?

A critical analysis of a movie involves evaluating its elements, such as plot, themes, characters, and cinematography, and providing an informed opinion on its strengths and weaknesses. To write it, watch the movie attentively, take notes, develop a clear thesis statement, support arguments with evidence, and balance the positive and negative.

How to write a psychological analysis of a movie?

A psychological analysis of a movie examines characters’ motivations, behaviors, and emotional experiences. To write it, analyze the characters’ psychological development, their relationships, and the impact of psychological themes conveyed in the film. Support your analysis with psychological theories and evidence from the movie.

- Film Analysis | UNC Writing Center

- Psychological Analysis of Films | Steemit

- Critical Film Analysis | University of Hawaii

- Questions to Ask of Any Film | All American High School Film Festival

- Resources – How to Write a Film Analysis | Northwestern

- Film Analysis | University of Toronto

- Film Writing: Sample Analysis | Purdue Online Writing Lab

- Film Analysis Web Site 2.0 | Yale University

- Questions for Film Analysis | University of Washington

- Film & Media Studies Resources: Types of Film Analysis | Bowling Green State University

- Film & Media Studies Resources: Researching a Film | Bowling Green State University

- Motion Picture Analysis Worksheet | University of Houston

- Reviews vs Film Criticism | The University of Vermont Libraries

- Television and Film Analysis Questions | University of Michigan

- How to Write About Film: The Movie Review, the Theoretical Essay, and the Critical Essay | University of Colorado

Descriptive Essay Topics: Examples, Outline, & More

371 fun argumentative essay topics for 2024.

Text size: A A A

About the BFI

Strategy and policy

Press releases and media enquiries

Jobs and opportunities

Join and support

Become a Member

Become a Patron

Using your BFI Membership

Corporate support

Trusts and foundations

Make a donation

Watch films on BFI Player

BFI Southbank tickets

- Follow @bfi

Watch and discover

In this section

Watch at home on BFI Player

What’s on at BFI Southbank

What’s on at BFI IMAX

BFI National Archive

Explore our festivals

BFI film releases

Read features and reviews

Read film comment from Sight & Sound

I want to…

Watch films online

Browse BFI Southbank seasons

Book a film for my cinema

Find out about international touring programmes

Learning and training

BFI Film Academy: opportunities for young creatives

Get funding to progress my creative career

Find resources and events for teachers

Join events and activities for families

BFI Reuben Library

Search the BFI National Archive collections

Browse our education events

Use film and TV in my classroom

Read research data and market intelligence

Funding and industry

Get funding and support

Search for projects funded by National Lottery

Apply for British certification and tax relief

Industry data and insights

Inclusion in the film industry

Find projects backed by the BFI

Get help as a new filmmaker and find out about NETWORK

Read industry research and statistics

Find out about booking film programmes internationally

You are here

The essay film

In recent years the essay film has attained widespread recognition as a particular category of film practice, with its own history and canonical figures and texts. In tandem with a major season throughout August at London’s BFI Southbank, Sight & Sound explores the characteristics that have come to define this most elastic of forms and looks in detail at a dozen influential milestone essay films.

Andrew Tracy , Katy McGahan , Olaf Möller , Sergio Wolf , Nina Power Updated: 7 May 2019

from our August 2013 issue

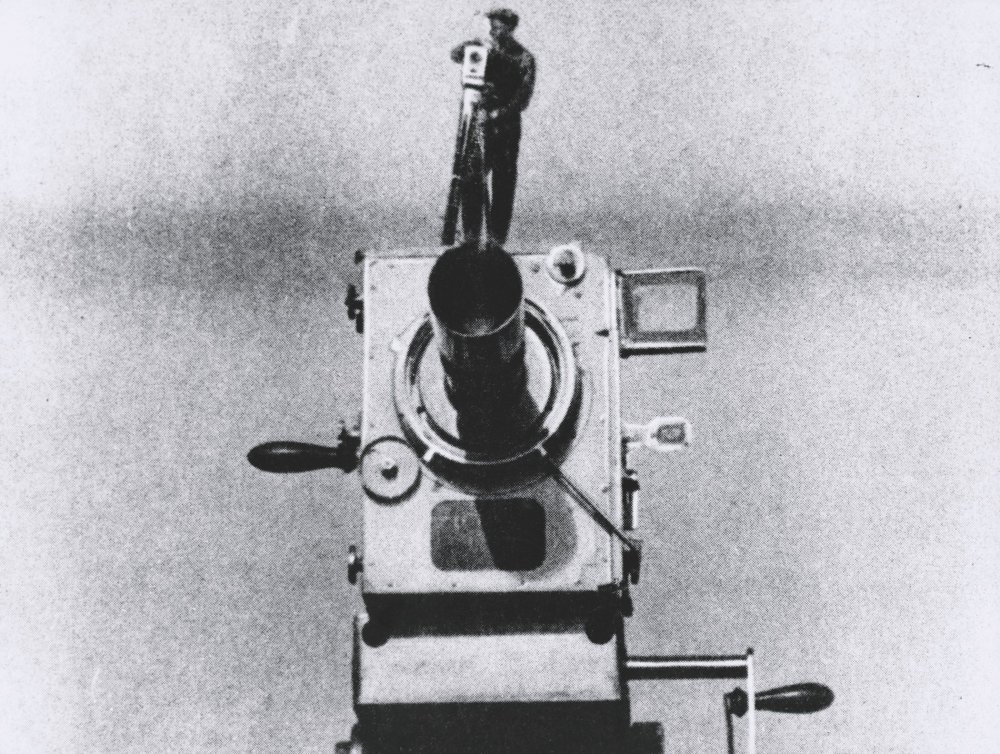

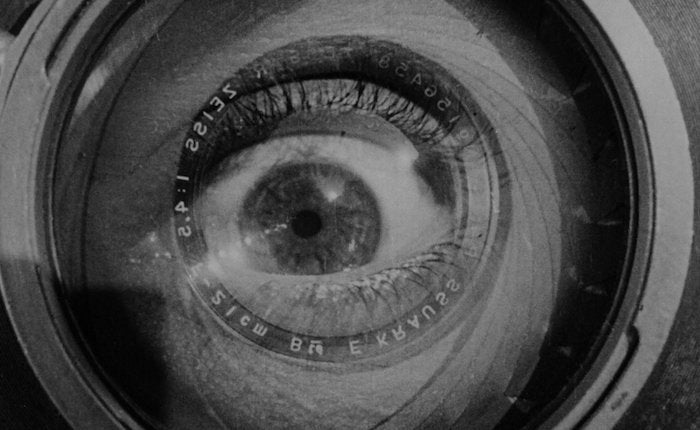

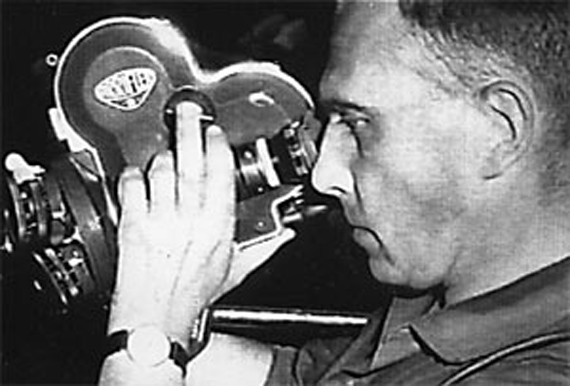

Le camera stylo? Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

I recently had a heated argument with a cinephile filmmaking friend about Chris Marker’s Sans soleil (1983). Having recently completed her first feature, and with such matters on her mind, my friend contended that the film’s power lay in its combinations of image and sound, irrespective of Marker’s inimitable voiceover narration. “Do you think that people who can’t understand English or French will get nothing out of the film?” she said; to which I – hot under the collar – replied that they might very well get something, but that something would not be the complete work.

The Sight & Sound Deep Focus season Thought in Action: The Art of the Essay Film runs at BFI Southbank 1-28 August 2013, with a keynote lecture by Kodwo Eshun on 1 August, a talk by writer and academic Laura Rascaroli on 27 August and a closing panel debate on 28 August.

To take this film-lovers’ tiff to a more elevated plane, what it suggests is that the essentialist conception of cinema is still present in cinephilic and critical culture, as are the difficulties of containing within it works that disrupt its very fabric. Ever since Vachel Lindsay published The Art of the Moving Picture in 1915 the quest to secure the autonomy of film as both medium and art – that ever-elusive ‘pure cinema’ – has been a preoccupation of film scholars, critics, cinephiles and filmmakers alike. My friend’s implicit derogation of the irreducible literary element of Sans soleil and her neo- Godard ian invocation of ‘image and sound’ touch on that strain of this phenomenon which finds, in the technical-functional combination of those two elements, an alchemical, if not transubstantiational, result.

Mechanically created, cinema defies mechanism: it is poetic, transportive and, if not irrational, then a-rational. This mystically-minded view has a long and illustrious tradition in film history, stretching from the sense-deranging surrealists – who famously found accidental poetry in the juxtapositions created by randomly walking into and out of films; to the surrealist-influenced, scientifically trained and ontologically minded André Bazin , whose realist veneration of the long take centred on the very preternaturalness of nature as revealed by the unblinking gaze of the camera; to the trash-bin idolatry of the American underground, weaving new cinematic mythologies from Hollywood detritus; and to auteurism itself, which (in its more simplistic iterations) sees the essence of the filmmaker inscribed even upon the most compromised of works.

It isn’t going too far to claim that this tradition has constituted the foundation of cinephilic culture and helped to shape the cinematic canon itself. If Marker has now been welcomed into that canon and – thanks to the far greater availability of his work – into the mainstream of (primarily DVD-educated) cinephilia, it is rarely acknowledged how much of that work cheerfully undercuts many of the long-held assumptions and pieties upon which it is built.

In his review of Letter from Siberia (1957), Bazin placed Marker at right angles to cinema proper, describing the film’s “primary material” as intelligence – specifically a “verbal intelligence” – rather than image. He dubbed Marker’s method a “horizontal” montage, “as opposed to traditional montage that plays with the sense of duration through the relationship of shot to shot”.

Here, claimed Bazin, “a given image doesn’t refer to the one that preceded it or the one that will follow, but rather it refers laterally, in some way, to what is said.” Thus the very thing which makes Letter “extraordinary”, in Bazin’s estimation, is also what makes it not-cinema. Looking for a term to describe it, Bazin hit upon a prophetic turn of phrase, writing that Marker’s film is, “to borrow Jean Vigo’s formulation of À propos de Nice (‘a documentary point of view’), an essay documented by film. The important word is ‘essay’, understood in the same sense that it has in literature – an essay at once historical and political, written by a poet as well.”

Marker’s canonisation has proceeded apace with that of the form of which he has become the exemplar. Whether used as critical/curatorial shorthand in reviews and programme notes, employed as a model by filmmakers or examined in theoretical depth in major retrospectives (this summer’s BFI Southbank programme, for instance, follows upon Andréa Picard’s two-part series ‘The Way of the Termite’ at TIFF Cinémathèque in 2009-2010, which drew inspiration from Jean-Pierre Gorin ’s groundbreaking programme of the same title at Vienna Filmmuseum in 2007), the ‘essay film’ has attained in recent years widespread recognition as a particular, if perennially porous, mode of film practice. An appealingly simple formulation, the term has proved both taxonomically useful and remarkably elastic, allowing one to define a field of previously unassimilable objects while ranging far and wide throughout film history to claim other previously identified objects for this invented tradition.

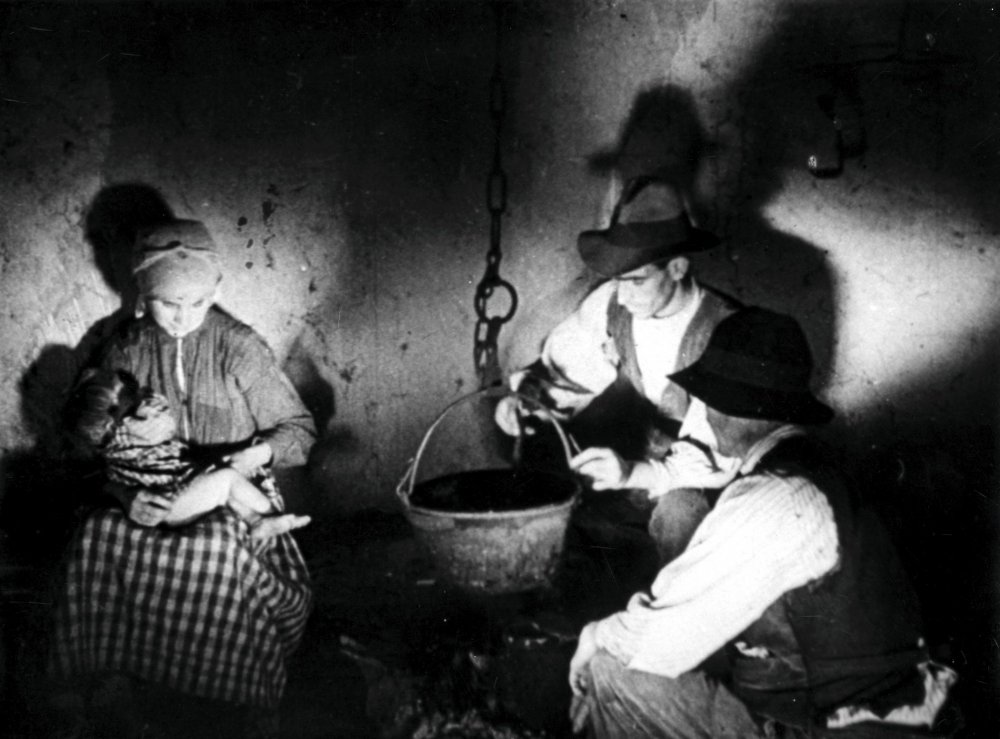

Las Hurdes (1933)

It is crucial to note that the ‘essay film’ is not only a post-facto appellation for a kind of film practice that had not bothered to mark itself with a moniker, but also an invention and an intervention. While it has acquired its own set of canonical ‘texts’ that include the collected works of Marker, much of Godard – from the missive (the 52-minute Letter to Jane , 1972) to the massive ( Histoire(s) de cinéma , 1988-98) – Welles’s F for Fake (1973) and Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), it has also poached on the territory of other, ‘sovereign’ forms, expanding its purview in accordance with the whims of its missionaries.

From documentary especially, Vigo’s aforementioned À propos de Nice, Ivens’s Rain (1929), Buñuel’s sardonic Las Hurdes (1933), Resnais’s Night and Fog (1955), Rouch and Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961); from the avant garde, Akerman’s Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974), Straub/Huillet’s Trop tôt, trop tard (1982); from agitprop, Getino and Solanas’s The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), Portabella’s Informe general… (1976); and even from ‘pure’ fiction, for example Gorin’s provocative selection of Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909).

Just as within itself the essay film presents, in the words of Gorin, “the meandering of an intelligence that tries to multiply the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected),” so, without, its scope expands exponentially through the industrious activity of its adherents, blithely cutting across definitional borders and – as per the Manny Farber ian concept which gave Gorin’s ‘Termite’ series its name – creating meaning precisely by eating away at its own boundaries. In the scope of its application and its association more with an (amorphous) sensibility as opposed to fixed rules, the essay film bears similarities to the most famous of all fabricated genres: film noir, which has been located both in its natural habitat of the crime thriller as well as in such disparate climates as melodramas, westerns and science fiction.

The essay film, however, has proved even more peripatetic: where noir was formulated from the films of a determinate historical period (no matter that the temporal goalposts are continually shifted), the essay film is resolutely unfixed in time; it has its choice of forebears. And while noir, despite its occasional shadings over into semi-documentary during the 1940s, remains bound to fictional narratives, the essay film moves blithely between the realms of fiction and non-fiction, complicating the terms of both.

“Here is a form that seems to accommodate the two sides of that divide at the same time, that can navigate from documentary to fiction and back, creating other polarities in the process between which it can operate,” writes Gorin. When Orson Welles , in the closing moments of his masterful meditation on authenticity and illusion F for Fake, chortles, “I did promise that for one hour, I’d tell you only the truth. For the past 17 minutes, I’ve been lying my head off,” he is expressing both the conjuror’s pleasure in a trick well played and the artist’s delight in a self-defined mode that is cheerfully impure in both form and, perhaps, intention.

Nevertheless, as the essay film merrily traipses through celluloid history it intersects with ‘pure cinema’ at many turns and its form as such owes much to one particularly prominent variety thereof.

The montage tradition

If the mystical strain described above represents the Dionysian side of pure cinema, Soviet montage was its Apollonian opposite: randomness, revelation and sensuous response countered by construction, forceful argumentation and didactic instruction.

No less than the mystics, however, the montagists were after essences. Eisenstein , Dziga Vertov and Pudovkin , along with their transnational associates and acolytes, sought to crystallise abstract concepts in the direct and purposeful juxtaposition of forceful, hard-edged images – the general made powerfully, viscerally immediate in the particular. Here, says Eisenstein, in the umbrella-wielding harpies who set upon the revolutionaries in October (1928), is bourgeois Reaction made manifest; here, in the serried ranks of soldiers proceeding as one down the Odessa Steps in Battleship Potemkin (1925), is Oppression undisguised; here, in the condemned Potemkin sailor who wins over his imminent executioners with a cry of “Brothers!” – a moment powerfully invoked by Marker at the beginning of his magnum opus A Grin Without a Cat (1977) – is Solidarity emergent and, from it, the seeds of Revolution.

The relentlessly unidirectional focus of classical Soviet montage puts it methodologically and temperamentally at odds with the ruminative, digressive and playful qualities we associate with the essay film. So, too, the former’s fierce ideological certainty and cadre spirit contrast with that free play of the mind, the Montaigne -inspired meanderings of individual intelligence, that so characterise our image of the latter.

Beyond Marker’s personal interest in and inheritance from the Soviet masters, classical montage laid the foundations of the essay film most pertinently in its foregrounding of the presence, within the fabric of the film, of a directing intelligence. Conducting their experiments in film not through ‘pure’ abstraction but through narrative, the montagists made manifest at least two operative levels within the film: the narrative itself and the arrangement of that narrative by which the deeper structures that move it are made legible. Against the seamless, immersive illusionism of commercial cinema, montage was a key for decrypting those social forces, both overt and hidden, that govern human society.

And as such it was method rather than material that was the pathway to truth. Fidelity to the authentic – whether the accurate representation of historical events or the documentary flavouring of Eisensteinian typage – was important only insomuch as it provided the filmmaker with another tool to reach a considerably higher plane of reality.

Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm (1931)

Midway on their Marxian mission to change the world rather than interpret it, the montagists actively made the world even as they revealed it. In doing so they powerfully expressed the dialectic between control and chaos that would come to be not only one of the chief motors of the essay film but the crux of modernity itself.

Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), now claimed as the most venerable and venerated ancestor of the essay film (and this despite its prototypically purist claim to realise a ‘universal’ cinematic language “based on its complete separation from the language of literature and the theatre”) is the archetypal model of this high-modernist agon. While it is the turning of the movie projector itself and the penetrating gaze of Vertov’s kino-eye that sets the whirling dynamo of the city into motion, the recorder creating that which it records, that motion is also outside its control.

At the dawn of the cinematic century, the American writer Henry Adams saw in the dynamo both the expression of human mastery over nature and a conduit to mysterious, elemental powers beyond our comprehension. So, too, the modernist ambition expressed in literature, painting, architecture and cinema to capture a subject from all angles – to exhaust its wealth of surfaces, meanings, implications, resonances – collides with awe (or fear) before a plenitude that can never be encompassed.

Remove the high-modernist sense of mission and we can see this same dynamic as animating the essay film – recall that last, parenthetical term in Gorin’s formulation of the essay film, “multiply[ing] the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected)”. The nimble movements and multi-angled perspectives of the essay film are founded on this negotiation between active choice and passive possession; on the recognition that even the keenest insight pales in the face of an ultimate unknowability.

The other key inheritance the essay film received from the classical montage tradition, perhaps inevitably, was a progressive spirit, however variously defined. While Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) amply and chillingly demonstrated that montage, like any instrumental apparatus, has no inherent ideological nature, hers were more the exceptions that proved the rule. (Though why, apart from ideological repulsiveness, should Riefenstahl’s plentifully fabricated ‘documentaries’ not be considered as essay films in their own right?)

The overwhelming fact remains that the great majority of those who drew upon the Soviet montagists for explicitly ideological ends (as opposed to Hollywood’s opportunistic swipings) resided on the left of the spectrum – and, in the montagists’ most notable successor in the period immediately following, retained their alignment with and inextricability from the state.

Progressive vs radical

The Grierson ian documentary movement in Britain neutered the political and aesthetic radicalism of its more dynamic model in favour of paternalistic progressivism founded on conformity, class complacency and snobbery towards its own medium. But if it offered a far paler antecedent to the essay film than the Soviet montage tradition, it nevertheless represents an important stage in the evolution of the essay-film form, for reasons not unrelated to some of those rather staid qualities.

The Soviet montagists had created a vision of modernity racing into the future at pace with the social and spiritual liberation of its proletarian pilot-passenger, an aggressively public ideology of group solidarity. The Grierson school, by contrast, offered a domesticated image of an efficient, rational and productive modern industrial society based on interconnected but separate public and private spheres, as per the ideological values of middle-class liberal individualism.

The Soviet montagists had looked to forge a universal, ‘pure’ cinematic language, at least before the oppressive dictates of Stalinist socialist realism shackled them. The Grierson school, evincing a middle-class disdain for the popular and ‘low’ arts, sought instead to purify the sullied medium of cinema by importing extra-cinematic prestige: most notably Night Mail (1936), with its Auden -penned, Britten -scored ode to the magic of the mail, or Humphrey Jennings’s salute to wartime solidarity A Diary for Timothy (1945), with its mildly sententious E.M. Forster narration.

Night Mail (1936)

What this domesticated dynamism and retrograde pursuit of high-cultural bona fides achieved, however, was to mingle a newfound cinematic language (montage) with a traditionally literary one (narration); and, despite the salutes to state-oriented communality, to re-introduce the individual, idiosyncratic voice as the vehicle of meaning – as the mediating intelligence that connects the viewer to the images viewed.

In Night Mail especially there is, in the whimsy of the Auden text and the film’s synchronisation of private time and public history, an intimation of the essay film’s musing, reflective voice as the chugging rhythm of the narration timed to the speeding wheels of the train gives way to a nocturnal vision of solitary dreamers bedevilled by spectral monsters, awakening in expectation of the postman’s knock with a “quickening of the heart/for who can bear to be forgot?”

It’s a curiously disquieting conclusion: this unsettling, anxious vision of disappearance that takes on an even darker shade with the looming spectre of war – one that rhymes, five decades on, with the wistful search of Marker’s narrator in Sans soleil, seeking those fleeting images which “quicken the heart” in a world where wars both past and present have been forgotten, subsumed in a modern society built upon the systematic banishment of memory.

It is, of course, with the seminal post-war collaborations between Marker and Alain Resnais that the essay film proper emerges. In contrast to the striving culture-snobbery of the Griersonian documentary, the Resnais-Marker collaborations (and the Resnais solo documentary shorts that preceded them) inaugurate a blithe, seemingly effortless dialogue between cinema and the other arts in both their subjects (painting, sculpture) and their assorted creative personnel (writers Paul Éluard , Jean Cayrol , Raymond Queneau , composers Darius Milhaud and Hanns Eisler ). This also marks the point where the revolutionary line of the Soviets and the soft, statist liberalism of the British documentarians give way to a more free-floating but staunchly oppositional leftism, one derived as much from a spirit of humanistic inquiry as from ideological affiliation.

Related to this was the form’s problems with official patronage. Originally conceived as commissions by various French government or government-affiliated bodies, the Resnais-Marker films famously ran into trouble from French censors: Les statues meurent aussi (1953) for its condemnation of French colonialism, Night and Fog for its shots of Vichy policemen guarding deportation camps; the former film would have its second half lopped off before being cleared for screening, the latter its offending shots removed.

Night and Fog (1955)

Appropriately, it is at this moment that the emphasis of the essay film begins to shift away from tactile presence – the whirl of the city, the rhythm of the rain, the workings of industry – to felt absence. The montagists had marvelled at the workings of human creations which raced ahead irrespective of human efforts; here, the systems created by humanity to master the world write, in their very functioning, an epitaph for those things extinguished in the act of mastering them. The African masks preserved in the Musée de l’Homme in Les statues meurent aussi speak of a bloody legacy of vanquished and conquered civilisations; the labyrinthine archival complex of the Bibliothèque Nationale in the sardonically titled Toute la mémoire du monde (1956) sparks a disquisition on all that is forgotten in the act of cataloguing knowledge; the miracle of modern plastics saluted in the witty, industrially commissioned Le Chant du styrène (1958) regresses backwards to its homely beginnings; in Night and Fog an unprecedentedly enormous effort of human organisation marshals itself to actively produce a dreadful, previously unimaginable nullity.

To overstate the case, loss is the primary motor of the modern essay film: loss of belief in the image’s ability to faithfully reflect reality; loss of faith in the cinema’s ability to capture life as it is lived; loss of illusions about cinema’s ‘purity’, its autonomy from the other arts or, for that matter, the world.

“You never know what you may be filming,” notes one of Marker’s narrating surrogates in A Grin Without a Cat, as footage of the Chilean equestrian team at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics offers a glimpse of a future member of the Pinochet junta. The image and sound captured at the time of filming offer one facet of reality; it is only with this lateral move outside that reality that the future reality it conceals can speak.

What will distinguish the essay film, as Bazin noted, is not only its ability to make the image but also its ability to interrogate it, to dispel the illusion of its sovereignty and see it as part of a matrix of meaning that extends beyond the screen. No less than were the montagists, the film-essayists seek the motive forces of modern society not by crystallising eternal verities in powerful images but by investigating that ever-shifting, kaleidoscopic relationship between our regime of images and the realities it both reveals and occludes.

— Andrew Tracy

1. À propos de Nice

Jean Vigo, 1930

Few documentaries have achieved the cult status of the 22-minute A propos de Nice, co-directed by Jean Vigo and cameraman Boris Kaufman at the beginning of their careers. The film retains a spontaneous, apparently haphazard, quality yet its careful montage combines a strong realist drive, lyrical dashes – helped by Marc Perrone’s accordion music – and a clear political agenda.

In today’s era, in which the Côte d’Azur has become a byword for hedonistic consumption, it’s refreshing to see a film that systematically undermines its glossy surface. Using images sometimes ‘stolen’ with hidden cameras, A propos de Nice moves between the city’s main sites of pleasure: the Casino, the Promenade des Anglais, the Hotel Negresco and the carnival. Occasionally the filmmakers remind us of the sea, the birds, the wind in the trees but mostly they contrast people: the rich play tennis, the poor boules; the rich have tea, the poor gamble in the (then) squalid streets of the Old Town.

As often, women bear the brunt of any critique of bourgeois consumption: a rich old woman’s head is compared to an ostrich, others grin as they gaze up at phallic factory chimneys; young women dance frenetically, their crotch to the camera. In the film’s most famous image, an elegant woman is ‘stripped’ by the camera to reveal her naked body – not quite matched by a man’s shoes vanishing to display his naked feet to the shoe-shine.

An essay film avant la lettre , A propos de Nice ends on Soviet-style workers’ faces and burning furnaces. The message is clear, even if it has not been heeded by history.

— Ginette Vincendeau

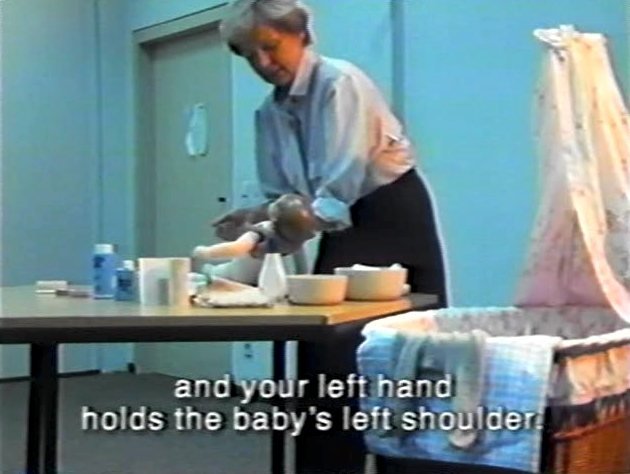

2. A Diary for Timothy

Humphrey Jennings, 1945

A Diary for Timothy takes the form of a journal addressed to the eponymous Timothy James Jenkins, born on 3 September 1944, exactly five years after Britain’s entry into World War II. The narrator, Michael Redgrave , a benevolent offscreen presence, informs young Timothy about the momentous events since his birth and later advises that, even when the war is over, there will be “everyday danger”.

The subjectivity and speculative approach maintained throughout are more akin to the essay tradition than traditional propaganda in their rejection of mere glib conveyance of information or thunderous hectoring. Instead Jennings invites us quietly to observe the nuances of everyday life as Britain enters the final chapter of the war. Against the momentous political backdrop, otherwise routine, everyday activities are ascribed new profundity as the Welsh miner Geronwy, Alan the farmer, Bill the railway engineer and Peter the convalescent fighter pilot go about their daily business.

Within the confines of the Ministry of Information’s remit – to lift the spirits of a battle-weary nation – and the loose narrative framework of Timothy’s first six months, Jennings finds ample expression for the kind of formal experiment that sets his work apart from that of other contemporary documentarians. He worked across film, painting, photography, theatrical design, journalism and poetry; in Diary his protean spirit finds expression in a manner that transgresses the conventional parameters of wartime propaganda, stretching into film poem, philosophical reflection, social document, surrealistic ethnographic observation and impressionistic symphony. Managing to keep to the right side of sentimentality, it still makes for potent viewing.

— Catherine McGahan

3. Toute la mémoire du monde

Alain Resnais, 1956

In the opening credits of Toute la mémoire du monde, alongside the director’s name and that of producer Pierre Braunberger , one reads the mysterious designation “Groupe des XXX”. This Group of Thirty was an assembly of filmmakers who mobilised in the early 1950s to defend the “style, quality and ambitious subject matter” of short films in post-war France; the signatories of its 1953 ‘Declaration’ included Resnais , Chris Marker and Agnès Varda. The success of the campaign contributed to a golden age of short filmmaking that would last a decade and form the crucible of the French essay film.

A 22-minute poetic documentary about the old French Bibliothèque Nationale, Toute la mémoire du monde is a key work in this strand of filmmaking and one which can also be seen as part of a loose ‘trilogy of memory’ in Resnais’s early documentaries. Les statues meurent aussi (co-directed with Chris Marker) explored cultural memory as embodied in African art and the depredations of colonialism; Night and Fog was a seminal reckoning with the historical memory of the Nazi death camps. While less politically controversial than these earlier works, Toute la mémoire du monde’s depiction of the Bibliothèque Nationale is still oddly suggestive of a prison, with its uniformed guards and endless corridors. In W.G. Sebald ’s 2001 novel Austerlitz, directly after a passage dedicated to Resnais’s film, the protagonist describes his uncertainty over whether, when using the library, he “was on the Islands of the Blest, or, on the contrary, in a penal colony”.

Resnais explores the workings of the library through the effective device of following a book from arrival and cataloguing to its delivery to a reader (the book itself being something of an in-joke: a mocked-up travel guide to Mars in the Petite Planète series Marker was then editing for Editions du Seuil). With Resnais’s probing, mobile camerawork and a commentary by French writer Remo Forlani, Toute la mémoire du monde transforms the library into a mysterious labyrinth, something between an edifice and an organism: part brain and part tomb.

— Chris Darke

4. The House is Black

(Khaneh siah ast) Forough Farrokhzad, 1963

Before the House of Makhmalbaf there was The House is Black. Called “the greatest of all Iranian films” by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, who helped translate the subtitles from Farsi into English, this 20-minute black-and-white essay film by feminist poet Farrokhzad was shot in a leper colony near Tabriz in northern Iran and has been heralded as the touchstone of the Iranian New Wave.

The buildings of the Baba Baghi colony are brick and peeling whitewash but a student asked to write a sentence using the word ‘house’ offers Khaneh siah ast : the house is black. His hand, seen in close-up, is one of many in the film; rather than objects of medical curiosity, these hands – some fingerless, many distorted by the disease – are agents, always in movement, doing, making, exercising, praying. In putting white words on the blackboard, the student makes part of the film; in the next shots, the film’s credits appear, similarly handwritten on the same blackboard.

As they negotiate the camera’s gaze and provide the soundtrack by singing, stamping and wheeling a barrow, the lepers are co-authors of the film. Farrokhzad echoes their prayers, heard and seen on screen, with her voiceover, which collages religious texts, beginning with the passage from Psalm 55 famously set to music by Mendelssohn (“O for the wings of a dove”).

In the conjunctions between Farrokhzad’s poetic narration and diegetic sound, including tanbur-playing, an intense assonance arises. Its beat is provided by uniquely lyrical associative editing that would influence Abbas Kiarostami , who quotes Farrokhzad’s poem ‘The Wind Will Carry Us’ in his eponymous film . Repeated shots of familiar bodily movement, made musical, move the film insistently into the viewer’s body: it is infectious. Posing a question of aesthetics, The House Is Black uses the contagious gaze of cinema to dissolve the screen between Us and Them.

— Sophie Mayer

5. Letter to Jane: An Investigation About a Still

Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Pierre Gorin, 1972

With its invocation of Brecht (“Uncle Bertolt”), rejection of visual pleasure (for 52 minutes we’re mostly looking at a single black-and-white still) and discussion of the role of intellectuals in “the revolution”, Letter to Jane is so much of its time as to appear untranslatable to the present except as a curio from a distant era of radical cinema. Between 1969 and 1971, Godard and Gorin made films collectively as part of the Dziga Vertov Group before they returned, in 1972, to the mainstream with Tout va bien , a big-budget film about the aftermath of May 1968 featuring leftist stars Yves Montand and Jane Fonda . It was to the latter that Godard and Gorin directed their Letter after seeing a news photograph of her on a solidarity visit to North Vietnam in August 1972.

Intended to accompany the US release of Tout va bien, Letter to Jane is ‘a letter’ only in as much as it is fairly conversational in tone, with Godard and Gorin delivering their voiceovers in English. It’s stylistically more akin to the ‘blackboard films’ of the time, with their combination of pedagogical instruction and stern auto-critique.

It’s also an inspired semiological reading of a media image and a reckoning with the contradictions of celebrity activism. Godard and Gorin examine the image’s framing and camera angle and ask why Fonda is the ‘star’ of the photograph while the Vietnamese themselves remain faceless or out of focus? And what of her expression of compassionate concern? This “expression of an expression” they trace back, via an elaboration of the Kuleshov effect , through other famous faces – Henry Fonda , John Wayne , Lillian Gish and Falconetti – concluding that it allows for “no reverse shot” and serves only to bolster Western “good conscience”.

Letter to Jane is ultimately concerned with the same question that troubled philosophers such as Levinas and Derrida : what’s at stake ethically when one claims to speak “in place of the other”? Any contemporary critique of celebrity activism – from Bono and Geldof to Angelina Jolie – should start here, with a pair of gauchiste trolls muttering darkly beneath a press shot of ‘Hanoi Jane’.

6. F for Fake

Orson Welles, 1973

Those who insist it was all downhill for Orson Welles after Citizen Kane would do well to take a close look at this film made more than three decades later, in its own idiosyncratic way a masterpiece just as innovative as his better-known feature debut.

Perhaps the film’s comparative and undeserved critical neglect is due to its predominantly playful tone, or perhaps it’s because it is a low-budget, hard-to-categorise, deeply personal work that mixes original material with plenty of footage filmed by others – most extensively taken from a documentary by François Reichenbach about Clifford Irving and his bogus biography of his friend Elmyr de Hory , an art forger who claimed to have painted pictures attributed to famous names and hung in the world’s most prestigious galleries.

If the film had simply offered an account of the hoaxes perpetrated by that disreputable duo, it would have been entertaining enough but, by means of some extremely inventive, innovative and inspired editing, Welles broadens his study of fakery to take in his own history as a ‘charlatan’ – not merely his lifelong penchant for magician’s tricks but also the 1938 radio broadcast of his news-report adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds – as well as observations on Howard Hughes , Pablo Picasso and the anonymous builders of Chartres cathedral. So it is that Welles contrives to conjure up, behind a colourful cloak of consistently entertaining mischief, a rueful meditation on truth and falsehood, art and authorship – a subject presumably dear to his heart following Pauline Kael ’s then recent attempts to persuade the world that Herman J. Mankiewicz had been the real creative force behind Kane.

As a riposte to that thesis (albeit never framed as such), F for Fake is subtle, robust, supremely erudite and never once bitter; the darkest moment – as Welles contemplates the serene magnificence of Chartres – is at once an uncharacteristic but touchingly heartfelt display of humility and a poignant memento mori. And it is in this delicate balancing of the autobiographical with the universal, as well as in the dazzling deployment of cinematic form to illustrate and mirror content, that the film works its once unique, now highly influential magic.

— Geoff Andrew

7. How to Live in the German Federal Republic

(Leben – BRD) Harun Farocki, 1990

Harun Farocki ’s portrait of West Germany in 32 simulations from training sessions has no commentary, just the actions themselves in all their surreal beauty, one after the other. The Bundesrepublik Deutschland is shown as a nation of people who can deal with everything because they have been prepared – taught how to react properly in every possible situation.

We know how birth works; how to behave in kindergarten; how to chat up girls, boys or whatever we fancy (for we’re liberal-minded, if only in principle); how to look for a job and maybe live without finding one; how to wiggle our arses in the hottest way possible when we pole-dance, or manage a hostage crisis without things getting (too) bloody. Whatever job we do, we know it by heart; we also know how to manage whatever kind of psychological breakdown we experience; and we are also prepared for the end, and even have an idea about how our burial will go. This is the nation: one of fearful people in dire need of control over their one chance of getting it right.

Viewed from the present, How to Live in the German Federal Republic is revealed as the archetype of many a Farocki film in the decades to follow, for example Die Umschulung (1994), Der Auftritt (1996) or Nicht ohne Risiko (2004), all of which document as dispassionately as possible different – not necessarily simulated – scenarios of social interactions related to labour and capital. For all their enlightening beauty, none of these ever came close to How to Live in the German Federal Republic which, depending on one’s mood, can play like an absurd comedy or the most gut-wrenching drama. Yet one disquieting thing is certain: How to Live in the German Federal Republic didn’t age – our lives still look the same.

— Olaf Möller

8. One Man’s War

(La Guerre d’un seul homme) Edgardo Cozarinsky , 1982

One Man’s War proves that an auteur film can be made without writing a line, recording a sound or shooting a single frame. It’s easy to point to the ‘extraordinary’ character of the film, given its combination of materials that were not made to cohabit; there couldn’t be a less plausible dialogue than the one Cozarinsky establishes between the newsreels shot during the Nazi occupation of Paris and the Parisian diaries of novelist and Nazi officer Ernst Jünger . There’s some truth to Pascal Bonitzer’s assertion in Cahiers du cinéma in 1982 that the principle of the documentary was inverted here, since it is the images that provide a commentary for the voice.

But that observation still doesn’t pin down the uniqueness of a work that forces history through a series of registers, styles and dimensions, wiping out the distance between reality and subjectivity, propaganda and literature, cinema and journalism, daily life and dream, and establishing the idea not so much of communicating vessels as of contaminating vessels.

To enquire about the essayistic dimension of One Man’s War is to submit it to a test of purity against which the film itself is rebelling. This is no ars combinatoria but systems of collision and harmony; organic in their temporal development and experimental in their procedural eagerness. It’s like a machine created to die instantly; neither Cozarinsky nor anyone else could repeat the trick, as is the case with all great avant-garde works.

By blurring the genre of his literary essays, his fictional films, his archival documentaries, his literary fictions, Cozarinsky showed he knew how to reinvent the erasure of borders. One Man’s War is not a film about the Occupation but a meditation on the different forms in which that Occupation can be represented.

—Sergio Wolf. Translated by Mar Diestro-Dópido

9. Sans soleil

Chris Marker, 1982

There are many moments to quicken the heart in Sans soleil but one in particular demonstrates the method at work in Marker’s peerless film. An unseen female narrator reads from letters sent to her by a globetrotting cameraman named Sandor Krasna (Marker’s nom de voyage), one of which muses on the 11th-century Japanese writer Sei Shōnagon .

As we hear of Shōnagon’s “list of elegant things, distressing things, even of things not worth doing”, we watch images of a missile being launched and a hovering bomber. What’s the connection? There is none. Nothing here fixes word and image in illustrative lockstep; it’s in the space between them that Sans soleil makes room for the spectator to drift, dream and think – to inimitable effect.

Sans soleil was Marker’s return to a personal mode of filmmaking after more than a decade in militant cinema. His reprise of the epistolary form looks back to earlier films such as Letter from Siberia (1958) but the ‘voice’ here is both intimate and removed. The narrator’s reading of Krasna’s letters flips the first person to the third, using ‘he’ instead of ‘I’. Distance and proximity in the words mirror, multiply and magnify both the distances travelled and the time spanned in the images, especially those of the 1960s and its lost dreams of revolutionary social change.

While it’s handy to define Sans soleil as an ‘essay film’, there’s something about the dry term that doesn’t do justice to the experience of watching it. After Marker’s death last year, when writing programme notes on the film, I came up with a line that captures something of what it’s like to watch Sans soleil: “a mesmerising, lucid and lovely river of film, which, like the river of the ancients, is never the same when one steps into it a second time”.

10. Handsworth Songs

Black Audio Film Collective, 1986

Made at the time of civil unrest in Birmingham, this key example of the essay film at its most complex remains relevant both formally and thematically. Handsworth Songs is no straightforward attempt to provide answers as to why the riots happened; instead, using archive film spliced with made and found footage of the events and the media and popular reaction to them, it creates a poetic sense of context.

The film is an example of counter-media in that it slows down the demand for either immediate explanation or blanket condemnation. Its stillness allows the history of immigration and the subsequent hostility of the media and the police to the black and Asian population to be told in careful detail.

One repeated scene shows a young black man running through a group of white policemen who surround him on all sides. He manages to break free several times before being wrestled to the ground; if only for one brief, utopian moment, an entirely different history of race in the UK is opened up.

The waves of post-war immigration are charted in the stories told both by a dominant (and frequently repressive) televisual narrative and, importantly, by migrants themselves. Interviews mingle with voiceover, music accompanies the machines that the Windrush generation work at. But there are no definitive answers here, only, as the Black Audio Film Collective memorably suggests, “the ghosts of songs”.

— Nina Power

11. Los Angeles Plays Itself

Thom Andersen, 2003

One of the attractions that drew early film pioneers out west, besides the sunlight and the industrial freedom, was the versatility of the southern Californian landscape: with sea, snowy mountains, desert, fruit groves, Spanish missions, an urban downtown and suburban boulevards all within a 100-mile radius, the Los Angeles basin quickly and famously became a kind of giant open-air film studio, available and pliant.

Of course, some people actually live there too. “Sometimes I think that gives me the right to criticise,” growls native Angeleno Andersen in his forensic three-hour prosecution of moving images of the movie city, whose mounting litany of complaints – couched in Encke King’s gravelly, near-parodically irritated voiceover, and sometimes organised, as Stuart Klawans wrote in The Nation, “in the manner of a saloon orator” – belies a sly humour leavening a radically serious intent.

Inspired in part by Mark Rappaport’s factual essay appropriations of screen fictions (Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, 1993; From the Journals of Jean Seberg , 1995), as well as Godard’s Histoire(s) de cinéma, this “city symphony in reverse” asserts public rights to our screen discourse through its magpie method as well as its argument. (Today you could rebrand it ‘Occupy Hollywood’.) Tinseltown malfeasance is evidenced across some 200 different film clips, from offences against geography and slurs against architecture to the overt historical mythologies of Chinatown (1974), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) and L.A. Confidential (1997), in which the city’s class and cultural fault-lines are repainted “in crocodile tears” as doleful tragedies of conspiracy, promoting hopelessness in the face of injustice.

Andersen’s film by contrast spurs us to independent activism, starting with the reclamation of our gaze: “What if we watch with our voluntary attention, instead of letting the movies direct us?” he asks, peering beyond the foregrounding of character and story. And what if more movies were better and more useful, helping us see our world for what it is? Los Angeles Plays Itself grows most moving – and useful – extolling the Los Angeles neorealism Andersen has in mind: stories of “so many men unneeded, unwanted”, as he says over a scene from Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1983), “in a world in which there is so much to be done”.

— Nick Bradshaw

12. La Morte Rouge

Víctor Erice, 2006

The famously unprolific Spanish director Víctor Erice may remain best known for his full-length fiction feature The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), but his other films are no less rewarding. Having made a brilliant foray into the fertile territory located somewhere between ‘documentary’ and ‘fiction’ with The Quince Tree Sun (1992), in this half-hour film made for the ‘Correspondences’ exhibition exploring resemblances in the oeuvres of Erice and Kiarostami , the relationship between reality and artifice becomes his very subject.

A ‘small’ work, it comprises stills, archive footage, clips from an old Sherlock Holmes movie, a few brief new scenes – mostly without actors – and music by Mompou and (for once, superbly used) Arvo Pärt . If its tone – it’s introduced as a “soliloquy” – and scale are modest, its thematic range and philosophical sophistication are considerable.

The title is the name of the Québécois village that is the setting for The Scarlet Claw (1944), a wartime Holmes mystery starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce which was the first movie Erice ever saw, taken by his sister to the Kursaal cinema in San Sebastian.

For the five-year-old, the experience was a revelation: unable to distinguish the ‘reality’ of the newsreel from that of the nightmare world of Roy William Neill’s film, he not only learned that death and murder existed but noted that the adults in the audience, presumably privy to some secret knowledge denied him, were unaffected by the corpses on screen. Had this something to do with war? Why was La Morte Rouge not on any map? And what did it signify that postman Potts was not, in fact, Potts but the killer – and an actor (whatever that was) to boot?

From such personal reminiscences – evoked with wondrous intimacy in the immaculate Castillian of the writer-director’s own wry narration – Erice fashions a lyrical meditation on themes that have underpinned his work from Beehive to Broken Windows (2012): time and change, memory and identity, innocence and experience, war and death. And because he understands, intellectually and emotionally, that the time-based medium he himself works in can reveal unforgettably vivid realities that belong wholly to the realm of the imaginary, La Morte Rouge is a great film not only about the power of cinema but about life itself.

Sight & Sound: the August 2013 issue

In this issue: Frances Ha’s Greta Gerwig – the most exciting actress in America? Plus Ryan Gosling in Only God Forgives, Wadjda, The Wall,...

More from this issue

DVDs and Blu Ray

Buy The Complete Humphrey Jennings Collection Volume Three: A Diary for Timothy on DVD and Blu Ray

Humphrey Jennings’s transition from wartime to peacetime filmmaking.

Buy Chronicle of a Summer on DVD and Blu Ray

Jean Rouch’s hugely influential and ground-breaking documentary.

Further reading

Video essay: The essay film – some thoughts of discontent

Kevin B. Lee

The land still lies: Handsworth Songs and the English riots

The world at sea: The Forgotten Space

What I owe to Chris Marker

Patricio Guzmán

His and her ghosts: reworking La Jetée

Melissa Bradshaw

At home (and away) with Agnès Varda

Daniel Trilling

Pere Portabella looks back

John Akomfrah’s Hauntologies

Laura Allsop

Back to the top

Commercial and licensing

BFI distribution

Archive content sales and licensing

BFI book releases and trade sales

Selling to the BFI

Terms of use

BFI Southbank purchases

Online community guidelines

Cookies and privacy

©2024 British Film Institute. All rights reserved. Registered charity 287780.

See something different

Subscribe now for exclusive offers and the best of cinema. Hand-picked.

17 Essential Movies For An Introduction To Essay Films

Put most concisely by Timothy Corrigan in his book on the film: ‘from its literary origins to its cinematic revisions, the istic describes the many-layered activities of a personal point of view as a public experience’.

Perhaps a close cousin to documentary, the film is at its core a personal mode of filmmaking. Structured in a breadth of forms, a partial definition could be said to be part fact, part fiction with an intense intimacy (but none of these are necessarily paramount).

Stemming from the literary as a form of personal expression borne from in-depth explorations of its chosen topic, the film can be agitprop, exploratory, or diaristic and generally rejects narrative progression and concretised conclusions in favour of a thematic ambivalence. Due to its nature as inherently personal, the term itself is as vague and expansive as the broad collective of films it purports to represent.

To borrow Aldous Huxley’s definition, the is a device for saying almost everything about almost anything. In built then is an inherent expansiveness that informs a great ambition in the form itself, but as Huxley acknowledges it can only say almost anything; whether extolling the need for a socialist state (Man with a Movie Camera), deconstructing the power and status of the image itself (Histoire(s) du Cinema, Images of the World and the Inscription of War, Los Angeles Plays Itself) or providing a means to consider ones of past (Walden, News from home, Blue), the film is only the form of expression, which unlike any other taxonomic term suggests almost nothing about the film itself other than its desire to explore.

Below is an 17 film introduction to the film that cannot be pinned down and continue to remake and remodel itself as freely as it sheds connections between any of the films within its own canon.

1. Man with a Movie Camera (1929) dir. Dziga Vertov

An exercise in technical experimentation, Man with a Movie Camera is the pioneering, not to mention most lauded, of Vertov’s filmic polemics: espousing not only a new, necessary way of life, but a means of living that is created through cinema.

Shot by Maurice Kaufman, brother of Vertov, the film is a portrait of a city across 24 hours via bold experimentation based on Vertov’s staunchly Marxist ideologies. Its propagandist structure does not however belie its beauty.

Through masterful technique it became the defining film of 1920’s Soviet Union (perhaps on a par with Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin). Its propagation of film as the means through which life is realised, that the camera is now an unequivocal feature of modernity and too a powerful political tool, creates a filmic love letter to industrialisation and the humanist elements of physical labour.

In opposition to Eisenstein, Vertov is a master of his own brand of idiosyncratic montage which, with its sublime manipulative technique combined with realist images, rejects the opiate affects of traditional narrative cinema, attempting to create instead a cinematic language in which the camera becomes the pen of the 20th century.

2. A Propos de Nice (1930) dir. Jean Vigo

Shot by Boris Kaufman, brother of Dziga Vertov (Man with a Movie Camera), A Propos de Nice is a satirical portrait of life in 1920’s Nice. The leisurely upper classes of French society are the subjects of a portrayal the blind escapism and ignorance created by modernity.