Advertisement

Educator Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Mainstream Education: a Systematic Review

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 19 January 2022

- Volume 10 , pages 477–491, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Amy Russell 1 ,

- Aideen Scriney 1 &

- Sinéad Smyth 1

18k Accesses

8 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Educator attitudes towards inclusive education impact its success. Attitudes differ depending on the SEN cohort, and so the current systematic review is the first to focus solely on students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Seven databases searched yielded 13 relevant articles. The majority reported positive educator attitudes towards ASD inclusion but with considerable variety in the measures used. There were mixed findings regarding the impact of training and experience on attitudes but, where measured, higher self-efficacy was related to positive attitudes. In summary, educator ASD inclusion attitudes are generally positive but we highlight the need to move towards more homogeneous attitudinal measures. Further research is needed to aggregate data on attitudes towards SEN cohorts other than those with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Leading Systems Change to Support Autistic Students

Improving Student Attitudes Toward Autistic Individuals: A Systematic Review

Approaches to Inclusion and Social Participation in School for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC)—a Systematic Research Review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Until relatively recently, students were frequently separated based on their perceived education needs. Students with special educational needs (SEN) were often educated in special education settings while their remaining peers were educated in what are often termed mainstream settings (Armstrong et al., 2011 ). Interest in wider issues of social inclusion, however, has led to consideration of how education may play a role in promoting social cohesion. As such, educational inclusion has become a central focus in many countries during the last decade (Qvortrup & Qvortrup, 2018 ). In educational contexts, inclusion is a teaching philosophy in which students with special educational needs (SEN) are actively engaged with their typically developing peers (Voltz et al., 2001 ). In practice, inclusion is considered ‘the continuing process of increasing the presence, participation and achievements of all children and young people’ (Ainscow, 2005 ). It is important to note that such definitions go beyond the simple placement of students with SEN in mainstream classrooms, as opposed to in specific specialised settings. Such a conceptualisation would reduce ‘inclusion’ to an issue of admission or placement and ignores the more complex dynamic side of inclusion as an effort to promote participation rather than simple placement with no reference to support and practices.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child ( 1989 ), every child has a right to education free from discrimination. Therefore, inclusive education is considered an important human rights issue (Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009 ). The United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2017 ) guidelines state that inclusion and equity should be acknowledged as principles for guiding educational policies and practices. UNESCO ( 2009 ) argues that inclusion benefits all learners as it focuses on responding to diverse needs and promotes a fairer society. Despite this, the practicality of ‘inclusive education’ still appears to be problematic in the eyes of some educators (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010 ; Allan, 2014 ). Although there has been a push by policymakers for individuals with SEN to be included in mainstream classrooms, there has been a lack of appropriate support for staff and students (Costello & Boyle, 2013 ). According to Mitchell ( 2014 ), ‘good teaching’ is systematic, explicit and intensive applications of effective teacher strategies. Such strategies should be appropriate to all learners even if they have to be adapted towards their specific educational needs (Norwich, 2003 ; Norwich & Lewis, 2001 ). Empirical studies show that pupils with SEN benefit from ‘good teaching’, even if it is not in a dedicated environment (Mitchell, 2014 ). A good quality education is paramount but a good quality inclusive education is optimal. If inclusion is being implemented internationally, it is important to determine if it works for all cohorts, and if it does not, we need to determine why not.

Educators’ beliefs are used as personal guidelines for defining and understanding educational contexts and roles (Zheng, 2009 ). These beliefs are resilient to rational arguments and scientific proofs which contradict them (UNESCO, 2002 ). Educators play a crucial role in the implementation of inclusive education (Ainscow, 2007 ; Rose & Howley, 2007 ) and their attitudes towards inclusion are vital for success (Loreman et al., 2011 ). However, inclusive education is suggested to be one of the most challenging issues for educators (Atta et al., 2009 ). The American Psychological Association ( 2021 ) defines an attitude as ‘a relatively enduring and general evaluation of an object, person, group, issue or concept on a dimension ranging from negative to positive’. For the purpose of this review, attitude refers to how the educator evaluates the inclusion of the student or SEN in question. Positive attitudes of educators have been related to successful inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream educational institutions (Roberts et al., 2008 ). Educators’ attitudes influence their willingness to accommodate and persist with difficult students and their beliefs about students’ abilities to learn (Stauble, 2009 ). A seminal research study on the impact of teacher expectation on student achievement was conducted by Rosenthal and Jacobson ( 1968 ). They found when teachers were told that some students (picked at random) did poorly on intelligence tests, when these students were revisited, their progress was significantly lower than their peers. This is called the ‘Pygmalion Effect’. It is the idea that the expectations of leaders (in this case, teachers) can influence the progress of the subordinate (the student). This is mainly because teachers put more effort into the students they expect to do well. Therefore, if educators do not believe that students with SEN will do well, they will not put effort into teaching them, and thus, these students will perform poorly.

Research has suggested that educators’ attitudes towards inclusion differ according to disability type. Specifically, educators have more positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with physical or mild learning disabilities compared to those with emotional disorders, cognitive impairments or behavioural issues (Cumming, 2011 ; De Boer et al., 2011 ; Rae et al., 2010 ). It, therefore, appears to be crucial to look at educator attitudes towards different SEN cohorts separately. However, to date, no researchers have attempted to aggregate data on the attitudes of educators on the inclusion of subsets of students with SEN. By assessing attitudes towards SEN in general, we may miss out on nuanced data about attitudes towards the inclusion of specific student groups.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) comprises a range of neurodevelopmental disorders which are characterised by social impairments, communication difficulties and repetitive and restrictive patterns of behaviours (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). As the ‘spectrum’ title suggests, individuals with ASD range in their social, communicative and intellectual abilities (Campisi et al., 2018 ). ASD affects about 1–2% of children worldwide (Elsabbagh et al., 2012 ) and the rate of diagnoses has increased dramatically over the last thirty years (Blaxill, 2004 ; Newschaffer et al., 2007 ). Individuals with ASD are also prone to having comorbid mental health disorders (van Steensel et al., 2011 ; Williams & Roberts, 2018 ). Many experience hyperactivity, attention deficits, executive function, social and communication deficits as well as self-injurious and stereotypic behaviours and emotional instability (Cappadocia et al., 2012 ). It is common for students with ASD to underachieve relative to their cognitive ability (Ashburner et al., 2010 ). The difficulties associated with ASD may lead to challenges in mainstream environments for these students (van Roekel et al., 2010 ), which may impact educators’ attitudes about the appropriateness of this environment for them. Although many individuals with ASD have significant deficits in functioning, many children diagnosed with ASD are highly functioning. Students with ASD are more likely to be excluded from school than most other groups of learners (Barnard, 2000 ; Department for Education & Skills, 2006 ; National Autistic Society, 2003 ). This may be because teaching students with ASD presents significant instructional challenges for educators which may lower their self-efficacy for working with these students (Anglim et al., 2018 ; Klassen et al., 2011 ; Rodden et al., 2018; Ruble et al., 2013 ). Two-thirds of teachers reported lacking confidence and being apprehensive about teaching a student with ASD (Anglim et al., 2018 ). Pupils with ASD are sometimes viewed as more difficult to include than other learners with SEN (House of Commons Education & Skills Committee, 2006 ). Teachers report experiencing tension when dealing with the difficulties these students have in social and emotional understanding (Emam & Farrell, 2009 ) and regard teaching students with ASD as particularly challenging (Simpson et al., 2003 ). As prevalence rates of ASD are so high in school settings and the impairments experienced can impact the classroom in different ways depending on the severity of behaviours displayed (Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ), it is important to assess the attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD specifically.

Educators engaging successfully with students with ASD must have an understanding of the social, cognitive and behavioural characteristics of the population (Simpson, 2004 ). Every student with ASD has unique strengths and weaknesses, and therefore, teaching strategies may be successful for some and not for others (Morrier et al., 2011 ). Educators often do not possess relevant knowledge to implement student-focused evidence-based practice (Freeman et al., 2014 ; Morrier et al., 2011 ; Paynter et al., 2017 ). Mainstream teachers report inadequate preparation and lack of ASD-specific training (Busby et al., 2012 ) as a reason for their poor attitudes towards inclusion of these students. Training can improve the self-efficacy of educators (Benoit, 2013 ) and relationships with students with ASD (Blatchford et al., 2009 ), reducing levels of occupational stress (Baghdadli et al., 2010 ). Leach and Duffy ( 2009 ) suggest that teaching pupils with ASD requires specific approaches that mainstream teachers may not be familiar with. Thus, training in the area might remedy this.

There are other perceived needs for successful inclusion. Both new and experienced teachers indicate that their greatest concern regarding inclusive education is inadequate resources and lack of staff (Forlin & Chambers, 2011 ; Round et al., 2016 ). As every child with ASD has unique needs, lack of resources is often cited by teachers to explain their reservations about inclusion of these learners (Busby et al., 2012 ; Ruel et al., 2015 ). Assessing the attitudes of educators and the factors influencing these will allow for the specific needs identified to be addressed and improve attitudes, thus enhancing inclusive education.

Review Purpose

Inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream education is recognised as a human right (Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009 ) and is thought to have benefits for all students (UNESCO, 2009 ). It has been found that positive attitudes of educators facilitate successful inclusion (Roberts et al., 2008 ), and importantly, that these attitudes seem to be dependent on disability type, with those with behavioural, social and emotional difficulties usually being least accepted (Khochen & Radford, 2012 ). ASD proves particularly difficult for inclusion because each student has unique abilities and deficits in these domains (Anglim et al., 2018 ). To date, systematic reviews have focused on SEN in general, rather than on attitudes towards specific SEN cohorts. Therefore, results may be overgeneralized. Aggregating data on educators’ attitudes towards ASD inclusion specifically could greatly assist in understanding the implementation of inclusive educational practices for children with ASD. The aim of the current review was to aggregate data on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream educational settings and to examine the factors which influence these attitudes. A review of this nature can help to draw attention to the importance of seeking out nuanced attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of different subsets of SEN to gain a deeper understanding of inclusive education practices.

Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted across seven databases: PsycINFO, CINAHL Complete, British Education Index, Education Research Complete, UK and Ireland Reference Centre, PsycArticles and Web of Science. The searches were conducted on the 5th of March 2021 (Web of Science search run and added 19th of March, 2021). The key search terms were as follows: ((Inclu* OR integrat* OR ‘inclusive education’) AND (Attitude* OR opinion* OR perspective* OR perception*) AND (Education OR mainstream OR school*) AND (ASD or autism spectrum disorder OR autism spectrum OR autism OR autistic OR Asperger*)).

Eligibility Criteria

To design the inclusion criteria for this review, the PICOSS (participants, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study design and setting) was used. It has been adopted by Cochrane and other systematic review organisations (Schardt et al., 2007 ). The inclusion criteria have been summarised in Table 1 . Studies were included in the final analysis if they (1) investigated educator attitudes regarding the educational inclusion of school aged children and adolescents diagnosed with ASD and (2) the participants were current educators. Studies were not included if (1) they were a review of previous studies, (2) they referred to students in settings other than primary or secondary education (e.g. preschool or third level education), (3) participants were not educators or were not currently working (including retired educators or pre-service educators), (4) attitudes were not clearly stated, (5) qualitative only studies and (6) any studies that only focused on attitudes towards inclusion of students with SEN but which did not allow for extraction of attitudes towards students with ASD specifically. The majority of the included studies refer to ‘autism’ or ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder’ but one study refers to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ (Agyapong et al., 2010 ). In 2013, Asperger’s syndrome became recognised under the umbrella of ‘Autism Spectrum Disorders’ under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ).

Details of Methods

In order to minimise bias, the review was conducted with a team of two reviewers and a supervisor. Results from each database were exported to ‘Zotero’ reference manager (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, 2021 ), where duplicates were removed before uploading to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, 2021 ). Covidence, a web-based software, was used throughout the remainder of the review. Each reviewer had access and independently screened the title and abstracts of the retrieved studies. The two reviewers then met to discuss the conflicts which arose during title and abstract screening and a consensus was reached. At the full-text screening phase, if the full text of a study was not available, the author was contacted and asked to provide it. The reviewers again independently screened the texts at this stage and met to discuss conflicts. The first reviewer conducted data extraction on all papers and the second reviewer conducted data extraction on 30% of the included studies. There was full agreement between the reviewers on the data extraction. Quality assessment was conducted by both reviewers and they again met to reach a consensus on the scores for each study.

Data Extraction

The first reviewer extracted data into a pre-prepared excel sheet for the papers chosen at full-text screening. The components extracted from each study were as follows: (1) name of study; (2) authors; (3) year of publication; (4) brief note on the study design; (5) sample size; (6) participant details (gender, mean age, occupation); (7) measures, means and standard deviations of outcome measures; (8) factors mentioned which influence educator attitudes.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the studies included in the review was assessed using the Quantitative Quality Appraisal Tool (adapted from Dunne et al., 2017 and Jefferies et al., 2012 ). The Quantitative Quality Appraisal tool asks 12 questions of the paper being assessed, with four possible answers: yes (score of 2 points), partial (score of 1 point), no (score of 0) and do not know (score of 0). Studies scoring 17–24 were considered good quality, 9–16 acceptable quality and 0–8 low quality. A summary of the quality appraisal ratings is included in the table of study characteristics (Table 2 ).

Synthesis of Results

A narrative synthesis was chosen to analyse the data, due to the heterogeneity of the measures. This type of synthesis is useful for explaining the ‘why’ behind phenomena. The data extracted from the studies was organised into themes. These themes are discussed later in the ‘ Results ’ section.

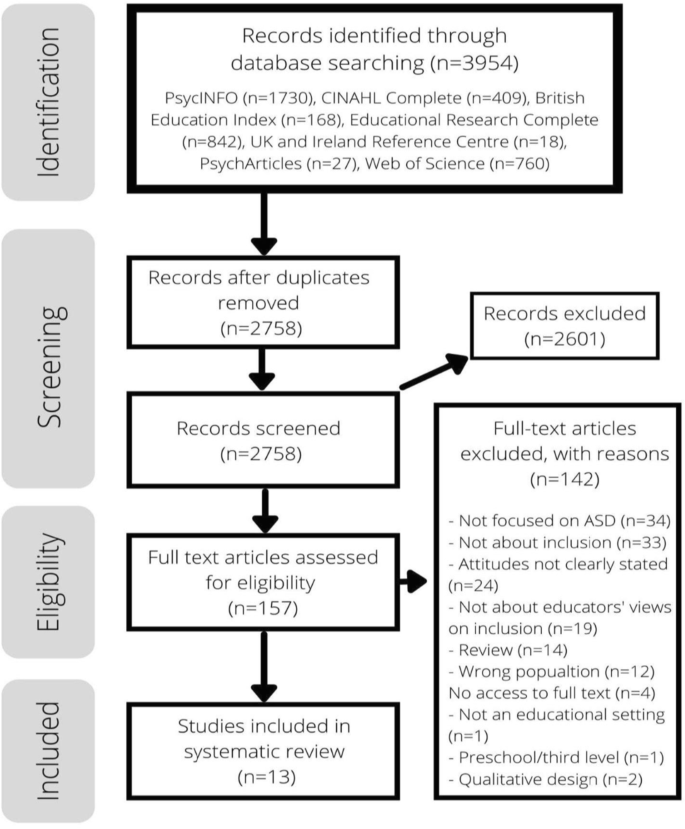

Following database searches, 3954 articles were identified for possible inclusion, as outlined in Fig. 1 . Of these, 1196 articles were duplicates and were subsequently excluded. Upon initial screening of the abstracts of the remaining 2758 articles, it was determined that 2601 did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria and 157 articles did. Following full-text review, of the 157 articles, 13 fulfilled the necessary inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in the review. Summary characteristics of these studies are provided in Table 2 .

PRISMA diagram for studies considered for the systematic review

Study Characteristics

A total of 3247 educators participated across the 13 identified studies. The sample sizes ranged from 72 to 863 and included general education (both primary and post primary), special education and physical education teachers, principals and instructors. Five studies did not present data on gender (Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Horrocks et al., 2008 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Salceanu, 2020 ; Su et al., 2020 ), but of the remaining studies, 1756 participants were female, and 326 were male. Two studies reported mean ages of 46 and 38.8 (Beamer & Yun, 2014 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Six studies reported their ages in categories, all participants were adults, with the youngest category being reported as ‘20–30’ and the oldest being ‘50 + ’ (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; Cassimos et al., 2015 ; Garrad et al., 2019 ; Lu et al., 2020 ; Salceau, 2020). The other studies did not report ages of their participants. Study locations varied from the USA ( n = 3) to Ireland ( n = 2), Romania ( n = 1), Jordan ( n = 1), Iceland ( n = 1), Greece ( n = 1), Australia ( n = 1), China ( n = 2) and Scotland ( n = 1). All studies were cross-sectional in nature.

Attitude Measures

There was considerable diversity in the scales used to measure the attitudes of participants, with six established scales in total and only one scale (the Autism Attitude Scale for Teachers; Olley et al., 1981 ) used more than once. Other studies used the Teacher’s Beliefs and Intentions towards Teaching Students with Disabilities (Jeong & Block, 2011 ), Principal’s Perspective Questionnaire (Horrocks, 2005 ), Impact of Inclusion Questionnaire (Hastings & Oakford, 2003 ), Inclusion of Children with Special Needs in Public Schools Questionnaire (Chitu et al., 2016) and Placement and Services Survey (Segall & Campbell, 2007 ). An additional six studies created their own surveys rather than using an existing measure (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Bjornsson et al., 2014; Cassimos et al., 2015 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Su et al., 2020 ). These surveys addressed the opinions of educators about the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education.

Attitudes of Educators: Educational Placement

Not surprisingly, given the heterogeneity of measures, the attitudes of educators were presented in a number of different ways. This made synthesis of results particularly difficult. Eight studies equated the opinions of their participants on the educational placement of students with ASD as representing their attitudes towards the inclusion of these students. However, the phrasing of the reported attitudes showed considerable variation. Abu-Hamour and Muhaidat ( 2013 ) asked participants if students with ASD should have the right to attend mainstream. Agyapong and colleagues (2010) asked if these students should be taught in mainstream classrooms. Cassimos and colleagues (2015) inquired whether their participants would accept these students in their classroom. Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) asked which cohort of SEN is most appropriate for mainstream education. Salceanu ( 2020 ) asked participants what they thought the best solution was for the educational placement of these students. Su and colleagues (2020) presented the opinions of their participants on whether or not these students could be taught in mainstream classrooms. The final two studies (Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ) showed some uniformity by asking participants where they thought was most appropriate for these students to be taught. These measures all purport to determine the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream so, therefore, they have been synthesised as such, but there are subtle differences between them.

In four of the eight studies which equated attitudes towards inclusion with beliefs about appropriate educational placement of autistic students, a large majority of participants showed positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 , 79.3%; Agyapong et al., 2010 , 71.1%; Segall & Campbell, 2001, 66.7%; Su et al., 2020 , 60.9%). Two studies found only a moderately positive attitude towards the inclusion of these students (Cassimos et al., 2015 , 56.1%, Salceanu, 2020 , 56.7%). The final two studies found their participants to have negative attitudes (Bjornsson et al., 2019 , 50.1%, McGregor & Campbell, 2001 , 68.7%).

Attitudes of Educators: Attitude Scales

The alternative approach to measuring attitudes towards inclusion was to use attitude scales and presenting the mean results of these. Five studies followed this model. These attitude scales represent a more affective measure of attitudes, gauging beliefs about inclusion and the perceived impacts of the inclusion of these students. Two of these studies found their participants to have a significantly positive attitude towards inclusion (Beamer & Yun, 2014 , 6.65 out of 7; Garrad et al., 2019 , 4.11 out of 5). Two other studies found moderately positive attitudes of their participants (Horrocks et al., 2008 , 3.76 out of 5; Lu et al., 2020 . 3.20 out of 5). One study found largely negative or neutral attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD (Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ; 54% with negative attitude, 36% neutral). Therefore, most studies who measured using attitude scales reported positive mean attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education. The majority of the included studies found positive attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education (c.f. Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ). There were no consistent differences in attitudes across educator type, country of publication or sample size. It is important to note, however, that the measures of attitudes were heterogeneous, making synthesis difficult and perhaps masking differences across studies.

Factors Influencing Attitudes

There were a number of factors examined within the studies which influenced the attitudes of participants. The common themes that emerged were experience and training, personal factors, perceived needs and student skills.

Experience and Training

The impact of experience on the attitudes of educators was measured in seven of the 15 studies. Three studies found that teaching experience did not influence attitudes (Garrad et al., 2019 ; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Three studies found that more experience led to more positive attitudes towards integration into mainstream education (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Cassimos et al., 2015 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ). Another two studies found the opposite that experience led to more negative attitudes (Horrocks et al., 2008 ; Su et al., 2020 ). Therefore, considerable variation exists surrounding whether or not experience has an impact on the attitudes of educators’ and the direction of this impact.

Training in SEN and ASD was another factor which was assessed for its relationship to inclusion attitudes. Participants in five studies stated that they lacked specific training on ASD (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Salceanu, 2020 ). Two studies found training in SEN in general or ASD in particular did not influence the inclusion attitudes of their participants (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ). Two studies found that the inclusion of ASD was more likely to be supported by educators who had training in the area (Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Cassimos et al., 2015 ). Garrad and colleagues (2019) found that there was a small positive relationship between attitudes and ASD-specific training but that it did not predict attitudes. Again, there was mixed evidence on the impact of training on educators’ attitudes with two studies stating there is no impact and three finding a positive relationship between the two.

There was also variability in the types of educators included in the studies. Five studies included ‘special needs educators’. In these studies, special needs educators were classified as those who were working in specialised placements with students with SEN. For example, Abu-Harmour and Muhaidat (2013) included ‘special education teachers who worked in special education centres that provided focused teaching for low-functioning students’ (p.34). Three of these studies found positive attitudes (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Salceanu, 2020 ; Su et al., 2020 ) and the other two found negative attitudes (Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ). McGregor and Campbell ( 2001 ) highlighted the difference between special educators and mainstream educators with experience working with students with SEN and those without. Forty-seven percent of specialist staff strongly agreed or agreed that full integration should be aimed for where possible, 47% of experienced mainstream staff agreed but only 27% of inexperienced mainstream staff thought full inclusion should happen where possible. Four percent of specialised staff strongly disagree or disagreed with full integration where possible, compared with 20% of experienced mainstream staff and 31% of inexperienced mainstream staff. Cassimos and colleagues (2015) also found that individuals with previous training or experience of working with students with ASD were more willing to include these learners in their classroom (73.5% of those with training and 81.3% of those with experience, compared to 46.2% and 46.3% of those with no training or experience, respectively).

Personal Factors

Of the personal factors investigated, the most common was the impact of self-efficacy on the attitude of educators which was examined in three studies. Beamer and Yun ( 2014 ) and Lu and colleagues (2020) found a significant, positive correlation between self-efficacy and inclusion attitudes of their participants (0.59 and 0.34, respectively). Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) found that self-efficacy was a predictor of placement decisions. Beamer and Yun ( 2014 ) found very small correlations between undergraduate training in adapted physical education (0.05) and graduate training in adapted physical education (0.06) and self-efficacy. However, Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) found a moderate correlation between self-efficacy and training (0.5). Another personal factor which was examined in the included studies was knowledge of ASD. Two studies investigated the effect of knowledge on attitudes, with mixed findings. One study found a significant positive relationship between knowledge and attitudes (Lu et al., 2020 ). However, another found that knowledge of ASD did not predict placement decisions (Segall & Campbell, 2014 ).

In addition to self-efficacy and knowledge, researchers also examined the relationship between factors such as gender, subject taught, subjective norms and type of educational institution. The two studies which assessed gender found no significant relationship with inclusion attitudes (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ). However, these studies did not have even spreads of gender, with female participants far out-weighing males. Those from ages 20 to 30 were found to be more accepting of the inclusion of students with ASD (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ). It was also found that educators who focused on teaching academic subjects had significantly lower inclusion attitude scores (Su et al., 2020 ). Subjective norms of teachers (i.e., taking into account what their colleagues think) were found to be significant predictors of placement opinions (Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) found that the educators’ perception of the disruptive behaviours did not influence their placement decisions. The influence of the type of institution the educator currently works in was found to have an influence on attitudes with educators in private schools and centres being found to have more positive attitudes (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ).

Perceived Needs

There were a number of perceived needs for successful inclusion cited by participants in the included studies. Some educators felt that they lacked the capability and understanding to deal with these students’ needs (Cassimos et al., 2015 ; Salceanu, 2020 ). McGregor and Campbell’s ( 2001 ) participants believed that integration was dependent on educators’ attitude while participants in Salceanu’s ( 2020 ) study felt that differential assessment strategies and curriculum adaptation were necessary for inclusion. The need for closer collaboration between schools and psychiatric services was also mentioned in one study (Agyapong et al., 2010 ). Beyond these staff related factors, resources and funding were the main needs cited in four studies (Agyapong et al., 2010 , 77.3% of participants; Cassimos et al., 2015 , 70.2%; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 , 66%; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ). Three of these four studies reported that participants felt that they did not have the necessary resources and funding to accommodate a student with ASD (Agyapong et al., 2010 , 77.3% of participants; Cassimos et al., 2015 , 70.2%; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 , 66%). Human resources featured frequently with educational psychologists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, special needs assistants (Agyapong et al., 2010 ), human resources (Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ) and adequate auxiliary help (McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ) considered to be required for inclusion. Leonard and Smyth ( 2020 ) also mentioned the need for classroom materials. All studies examining resources asked questions in different ways, making a clearer synthesis of the findings difficult.

Student Skills

Two studies reported on participant opinions of student skills which impact on successful inclusion in mainstream school. Abu-Harmour and Muhaidat (2013) reported participants’ perception that for inclusion to be successful, students with ASD needed to have certain skills. Cassimos and colleagues (2015), by contrast, reported on their participants’ views of student related factors that were barriers to inclusion. Cross over between the perceived barriers and facilitators between these two studies was in the area of communication and social skills. The specific skills noted by participants in Abu-Harmour and Muhaidat (2013) were ranked in order of importance as independence, imitation, behavioural, play, social, routine, language, pre-academic and academic. Their participants reported these as being necessary in order for students to navigate the social environment, communicate their needs, understand communication from other people and acquire strategies to help them learn with and through their peers. Cassimos and colleagues’ (2015) barriers were once again listed in order of perceived importance and comprised introvertedness, communication problems, obsessive, stereotypical and self-stimulatory behaviour and incomprehensible language of these students. These participants also voiced that vocational training was a better option for learners with ASD (69.7%). It is important to note that these were participant opinions and not evidence-based however, and additional three of the included studies (Horrocks et al., 2008 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ) investigated how the abilities of students with ASD impacted the educator’s attitude about their placement. Horrocks and colleagues (2008) measured the placement decisions of principals based on the description of five different pupils. All of the pupils described presented with a diagnosis of ASD. They found that those students who were described as having good academic performance were more often recommended to have high levels of inclusion by the principals. The participants were also found to be less likely to recommend high levels of inclusion in the students who showed social detachment. Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) provided their participants with descriptions of a student, Robby. There were six variations of Robby provided—moderate intellectual disability with no label, with label of autism, and with just label of an intellectual disability and average cognitive ability with no label, with label of autism, and with label of Asperger’s syndrome. The study found that the cognitive ability of Robby affected the teachers’ opinions regarding his placement. Participants reported that their own classroom was a less appropriate placement for students with a label of autism versus no label. However, the label of Asperger’s syndrome did not affect placement decisions when compared to the label of autism or no label at all. McGregor and Campbell ( 2001 ) asked participants what factors influence successful inclusion. Eighteen percent of specialist staff, 20% of experienced mainstream staff and 16% of inexperienced mainstream staff agreed or strongly agreed that successful inclusion depended on the academic ability of the student. A larger majority of the participants strongly agreed that the student’s degree of autism was a factor influencing successful inclusion. Participants were also asked if ‘able’ children were better educated in mainstream school. The responses were close on this item with 39% of specialist staff, 34% of experienced mainstream staff and 21% of inexperienced mainstream staff agreeing or strongly agreeing. It would appear that the cognitive abilities of the student impacts educators’ attitudes regarding their educational placement.

Potential Bias

All included studies were considered to be of good or acceptable quality according to the quality appraisal tools employed. The key areas in which the studies were downgraded were lack of control groups and not describing their non-responders. However, the use of a control group in studies such as this may not have been appropriate to answer the research questions. The overall risk of bias across the studies was considered to be low. All studies clearly stated their aims and objectives and adhered to them. There was no evidence of selective reporting and sampling bias across the studies.

While previous systematic reviews have explored the literature on educator attitudes towards the inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream education, no known published reviews have examined the inclusion of a specific cohort of students with SEN, those with a diagnosis of ASD. Given the diverse profiles of students with SEN, examining attitudes towards inclusion of students with SEN as a whole group may result in over generalisation and omitting specific attitudinal trends with regard to the inclusion of students with ASD. The aim of the current review was therefore to conduct the first systematic review to aggregate data on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education and the factors which influence these. A search of the literature yielded 13 eligible studies with a total of 3247 participants. These included participants in a number of different education roles and settings. Furthermore, these studies reported huge diversity in the attitudinal measures employed, making a narrative synthesis of the data the most appropriate approach.

Overall, the majority of the included studies reported that educators were in favour of the inclusion of students with ASD. It is interesting to note that attitudes towards inclusion did not vary across educator types. Hernandez et al. ( 2016 ), when examining attitudes towards general SEN inclusion, rather than ASD specifically, found that special education teachers had significantly more positive inclusion attitudes than their general education counterparts. They also found teacher type was a predictor of inclusion attitudes. From the findings of McGregor and Campbell ( 2001 ), it appears that attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD differ depending on the extent of experience with this group of learners. Cassimos and colleagues (2015) similarly reported that previous experience with students with ASD made educators more willing to accept them in their classroom. Perhaps giving experience and training in working with individuals with ASD to mainstream educators will make them more willing to accept these learners in their classroom.

Heterogeneity of Measures

Caution should be taken when considering these findings given that there was a considerable amount of heterogeneity of measures used in the included studies, which made synthesis difficult. Many studies created their own scales and presented their findings in different manners, making comparison challenging. It was not only the variety of measures which made synthesis difficult, but also the way in which attitudes were measured. As previously mentioned, attitudes were gauged using either affective measures or binary (yes/no) questions regarding where these students should be taught. Previous reviews which aimed to synthesise data on the attitudes of educators towards students with SEN also had similar issues. Lautenbach and Heyder’s ( 2019 ) systematic review for example saw a number of distinct measures used, the majority of which were self-constructed. Attitudes towards individuals with SEN, including ASD, are multi-faceted and include the domains of cognition, affect and behaviour (Nowicki & Sandieson, 2002 ). Therefore, comparing data from measures which may not be assessing the same domain may be futile. Antonak and Larrivee ( 1995 ) advised that the use of existing scales which are refined, revised and updated as necessary is preferable to creating new measures. Particular attention should be paid to choosing if attitudes are best estimated using affective measures or using binary placement questions. By reaching a consensus on which attitude scales to use in future research of this nature, more valuable information will be obtained. However, as this is the first review of its type, it would not be expected that an agreed upon measure would be used throughout studies.

The findings of predominantly positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD is despite known educational challenges for this cohort. Students with ASD are the most likely cohort of learners to be excluded from school (Barnard, 2000 ; Department for Education & Skills, 2006 ; National Autisitic Society, 2003). It has been found that students with ASD present significant instructional challenges for educators (Anglim et al., 2018 ; Klassen et al., 2011 ; Rodden et al., 2019 ; Ruble et al., 2013 ) and are often viewed as difficult to include (House of Commons Education & Skills Committee, 2006 ). Therefore, exploring the factors influencing these attitudes is important. Training in ASD and SEN and educator experience were the factors most assessed in the included studies. The results of the current synthesis found mixed evidence on the impact of training and experience on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD. Mainstream teachers often report a lack of specific ASD training as a reason for their apprehension to include these pupils (Busby et al., 2012 ).

Training did not clearly relate to more positive educator attitudes; however, self-efficacy of educators was found to have a positive relationship with inclusion attitudes, in the three studies where it was assessed. According to Bandura’s ( 1997 ) social cognitive theory, educator efficacy is concerned with educators’ appraisals of their capabilities to influence student outcomes (Wheatley, 2002 ). If educators believe that they are able to teach students with ASD and produce positive outcomes, they will be more willing to include them. Previously, increased self-efficacy has been linked with training (Benoit, 2013 ). However, two of the included studies which examined self-efficacy found mixed results on the correlations between training and self-efficacy. Interestingly, while a large majority of participants in Segall and Campbell’s ( 2014 ) study were confident in their ability to teach students with ASD (87%), only about one-third of them had ASD-specific training. Further research is needed to assess the impact of training on self-efficacy as self-efficacy can appear to have an impact on educators’ inclusion attitudes.

Resources and funding were the most cited need within the included studies, with many participants reporting that they did not feel that they had the necessary resources to include a student with ASD. Perception of available resources has a major influence on teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ). Inclusive education would not be possible without resources (Goldan & Schwab, 2020 ). However, high quality resources do not lead to high quality inclusive education (Loreman, 2014 ). The provision of resources, however, may improve the educators’ inclusion attitudes and, therefore, improve the inclusive education experience. In keeping with the current findings, research on general SEN resource needs found that personnel needs were the most commonly cited (Chiner & Cardona, 2013 ). The current findings suggest that educators do not feel that the inclusion of students with ASD requires distinct resources from general SEN inclusion and, therefore, these supports should be straightforward to deliver.

Perceived student skills necessary for success in mainstream settings were also highlighted by participants in some studies. While some involved academic abilities, many did not and showed a tendency for educators to express the belief that social and behavioural skills are most important for inclusion. It is interesting that many of the symptoms inherent in this cohort were reported as constraining for inclusion, for example, communication problems. Does this suggest that only students with low levels of stereotypical ASD symptoms are believed to be successful in mainstream education? Many of the studies did not assess participants’ attitudes towards students with ASD of differing abilities. Future research is needed to collect this type of evidence which would further enrich knowledge found in the current review.

There were a number of challenges and benefits to the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education both for the students themselves and for their peers. For example, the educators felt that mainstream education taught students with ASD life skills and prepared them for the future but that they may be bullied. For peers of students with ASD, the educators felt that inclusion taught them tolerance and understanding but that there may be a disruption in the class due to the student with ASD requiring extra assistance. By knowing the perceived benefits and challenges to inclusion of students with ASD from the perspective of the educator, a more in-depth understanding of what may be contributing to educators’ attitudes has been gained.

Implications of the Findings

The findings of this review provide an insight into the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD, for the first time. Research has been conducted to show educators’ attitudes towards general SEN inclusion, which encompasses many disabilities. Focusing on one cohort of the SEN population can provide more nuanced details. It has been found that educator attitudes towards inclusive education affect its successful implementation in mainstream classrooms (Ewing et al., 2018 ). Therefore, separating SEN cohorts and examining the attitudes of educators towards each one individually, a clearer understanding can be obtained and used to improve inclusive education. Some suggestions for improving educator attitudes and acceptance of the inclusion of students with ASD can also be found, for example, in targeting resourcing or educator perceptions of resourcing as well as targeting educator self-efficacy.

Limitations

The current review had a number of limitations, as with any study. A narrative synthesis was used in this review. This type of synthesis allows for interpretation and critique of the data and gives a deeper understanding (Greenhalgh et al., 2018 ). Often, meta-analyses are considered the gold standard for avoiding bias while synthesising data (Crombie & Davies, 2009). They allow for the quantification of beliefs about effects of variables using evidence from quantitative research (Jones et al., 2003 ). However, the data collected in this review did not lend itself to a meta-analysis. There were also a number of limitations to the included studies. As previously mentioned, many of the studies created their own measures of attitudes, many of which were not assessed for reliability or validity. While some of the sample sizes of the included studies were large (up to 863), others had small sample sizes and, therefore, the generalisability of their findings are limited.

Future Recommendations

Consensus on and standardisation of a measure to assess educator attitudes towards inclusion of students with ASD would make synthesis and comparison of results less complicated. It may encourage the replication of studies, thereby improving the reliability of findings. It is vital that more research be conducted on the reliability and validity of measures. Once the most effective measure has been identified, researchers must adopt this in future studies. By doing this, we can strengthen attitudinal research in this area. These measures can also then be adapted to other groups of learners with SEN to be able to assess attitudes towards their inclusion. However, in order to find the most effective measure, clarity must be sought regarding what is being measured. Further research is also needed to clearly define the relationship between inclusion attitudes and training and experience. It is also hoped that from this pioneering review, more research will be aggregated on different SEN cohorts (e.g. ADHD) so that a more comprehensive understanding of the inclusion attitudes of educators and how these can be improved can be gathered to create a more prosperous inclusive education environment. There were mixed findings regarding the impact of training and experience on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education suggesting that more in depth research on this is needed. Regardless of these conflicting reports, it does appear that pre-service teachers may benefit from specialised placements and specific training. This would certainly fulfil a training need and may impact on attitudes towards inclusion. Beyond training, self-efficacy is also positively associated with inclusion attitudes (Beamer & Yun, 2014 ; Lu et al., 2020 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Further investigation into the relationship between training, placement experiences in pre-service training and years of experience on self-efficacy is needed to better understand their impact on attitudes and, therefore, on practice. Perhaps increasing the general public’s knowledge and experience with individuals with ASD would positively impact their attitudes towards these individuals, making the community a more inclusive place. Further research on the impact of knowledge and experience in the general public should be conducted.

The current review presents a unique insight into the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education. Aggregations of data on distinct SEN cohorts have not been conducted to date. The current review found that the majority of the included studies presented positive attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of these students. However, due to the diversity of approaches to measure attitudes, these results may not accurately represent educators’ attitudes. The factors which influenced these were also unclear. Self-efficacy was found to have a positive relationship with inclusion attitudes in these studies but evidence on the influence of training and experience on attitudes was mixed. From a facilitatory perspective, participants reported that resources and specific student skills were required for successful inclusion. The review also gave an insight into the perceived benefits and challenges of the inclusion of students with ASD from the perspective of educators. It is hoped that this review will inspire others like it so that more nuanced data can be established to give an in-depth understanding of educators’ inclusion attitudes as they are vitally important for successful inclusion.

Abu-Hamour, B., & Muhaidat, M. (2013). Special education teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion of students with autism in Jordan. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 14 (1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.80202

Article Google Scholar

Agyapong, V., Migone, M., Crosson, C., & Mackey, B. (2010). Recognition and management of Asperger’s syndrome: Perceptions of primary school teachers. Ir J Psych Med, 27 (1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0790966700000835

Ainscow, M. (2005). Developing inclusive education systems: What are the levers for change? Journal of Educational Change, 6 , 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-005-1298-4

Ainscow, M. (2007). Taking an inclusive turn. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 7 (1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2007.00075.x

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903

Allan, J. (2014). Inclusive education and the arts. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44 (4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.921282

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

American Psychological Association. (2021). APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved 4 June 2021, from https://dictionary.apa.org/attitude

Anglim, J., Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2018). The self-efficacy of primary teachers in supporting the inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34 (1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1391750

Antonak, R. F., & Larrivee, B. (1995). Psychometric analysis and revision of the opinions relative to mainstreaming scale. Exceptional Children, 62 (2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299506200204

Armstrong, D., Armstrong, A. C., & Spandagou, I. (2011). Inclusion: By choice or by chance? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15 (1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.496192

Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., & Rodger, S. (2010). Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behavior at school. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4 (1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.07.002

Atta, M. A., Shah, M., & Khan, M. M. (2009). Inclusive school and inclusive teacher. The Dialogue, 4 (2), 272–283.

Google Scholar

Avramidis, E., & Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17 (2), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250210129056

Baghdadli, A., Rattaz, C., Ledésert, B., & Bursztejn, C. (2010). Étude descriptive des modalités d’accompagnement sanitaire, médicosocial et scolaire des personnes avec troubles envahissants du développement (TED) et de la satisfaction des familles – Aspects méthodologiques. Neuropsychiatrie de l’Enfance et de l’Adolescence, 5 8(8), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurenf.2010.07.014x

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . Freeman.

Barnard, J. (2000). Inclusion and autism: Is it working? 1,000 examples of inclusion in education and adult life from the National Autistic Society’s members . National Autistic Society.

Beamer, J. A., & Yun, J. (2014). Physical educators’ beliefs and self-reported behaviors toward including students with autism spectrum disorder. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 31 (4), 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2014-0134

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benoit, V. (2013). Intégration scolaire en Suisse: Focus sur le sentiment d’efficacité personnelle des enseignants.

Bjornsson, B. G., Saemundsen, E., & Njardvik, U. (2019). A survey of Icelandic elementary school teachers’ knowledge and views of autism–Implications for educational practices. Nordic Psychology, 71 (2), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2018.1480408

Blatchford, P., Bassett, P., Brown, P., & Webster, R. (2009). The effect of support staff on pupil engagement and individual attention. British Educational Research Journal, 35 (5), 661–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902878917

Blaxill, M. F. (2004). What’s going on? The question of time trends in autism. Public Health Reports, 119 (6), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phr.2004.09.003

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Busby, R., Ingram, R., Bowron, R., Oliver, J., & Lyons, B. (2012). Teaching elementary children with autism: Addressing teacher challenges and preparation needs. Rural educator , 33 (2), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v33i2.416

Campisi, L., Imran, N., Nazeer, A., Skokauskas, N., & Azeem, M. W. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder. British Medical Bulletin , 127 (1). https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldy026

Cappadocia, M. C., Weiss, J. A., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42 (2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x

Cassimos, D. C., Polychronopoulou, S. A., Tripsianis, G. I., & Syriopoulou-Delli, C. K. (2015). Views and attitudes of teachers on the educational integration of students with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 18 (4), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2013.794870

Chiner, E., & Cardona, M. C. (2013). Inclusive education in Spain: How do skills, resources, and supports affect regular education teachers’ perceptions of inclusion? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17 (5), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.689864

Corporation for Digital Scholarship. (2021). Zotero (Version 5.0) [Mac]. Retrieved from https://www.zotero.org/download/

Costello, S., & Boyle, C. (2013). Pre-service secondary teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education , 38 (4), 8. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n4.8

Cumming, T. M. (2011). The education of students with emotional and behavior disabilities in Australia: Current trends and future directions. Intervention in School and Clinic, 48 (1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451211423810

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary school teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15 (3), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903030089

Department for Education and Skills. (2006) Permanent and fixed period exclusions from schools and exclusions appeals in England 2004/05 . Nottingham: DfES Publications.

Dunne, S., Mooney, O., Coffey, L., Sharp, L., Desmond, D., Timon, C., O’Sullivan, E., & Gallagher, P. (2017). Psychological variables associated with quality of life following primary treatment for head and neck cancer: A systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2015. Psycho-Oncology, 26 (2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4109

Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y.-J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., et al. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research , 5 (3), 160e179. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.239

Emam, M. M., & Farrell, P. (2009). Tensions experienced by teachers and their views of support for pupils with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24 (4), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250903223070

Ewing, D. L., Monsen, J. J., & Kielblock, S. (2018). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A critical review of published questionnaires. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34 (2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1417822

Forlin, C., & Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: Increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39 (1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2010.540850

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., Briere, D. E., & MacSuga-Gage, A. S. (2014). Pre-service teacher training in classroom management: A review of state accreditation policy and teacher preparation programs. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37 (2), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413507002

Garrad, T. A., Rayner, C., & Pedersen, S. (2019). Attitudes of Australian primary school teachers towards the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 19 (1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12424

Goldan, J., & Schwab, S. (2020). Measuring students’ and teachers’ perceptions of resources in inclusive education–Validation of a newly developed instrument. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (12), 1326–1339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1515270

Greenhalgh, T., Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews?. European journal of clinical investigation, 48 (6). https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12931

Hastings, R. P., & Oakford, S. (2003). Student teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special needs. Educational Psychology, 23 (1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410303223

Hernandez, D. A., Hueck, S., & Charley, C. (2016). General education and special education teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals 79(93).

Horrocks, J. L., White, G., & Roberts, L. (2008). Principals’ attitudes regarding inclusion of children with autism in Pennsylvania public schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38 (8), 1462–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0522-x

Horrocks, J. (2005). Principals’ attitudes regarding inclusion of children with autism in Pennsylvania public schools . Unpublished doctoral dissertation , Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA.

House of Commons Education and Skills Committee. (2006). Special educational needs: Third report of session 2005–06 . The Stationary Office Limited.

Jefferies, P., Gallagher, P., & Dunne, S. (2012). The Paralympic athlete: A systematic review of the psychosocial literature. Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 36 (3), 278–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309364612450184

Jeong, M., & Block, M. E. (2011). Physical education teachers’ beliefs and intentions toward teaching students with disabilities. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82 (2), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2011.10599751

Jones, D., Roberts, K. A., Dixon-Woods, M., Fitzpatrick, R., & Abrams, K. R. (2003). Bayesian synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence: Overview and example. HDA Synthesis Series on Promoting Methodological Development in Evidence Synthesis: Understanding Bayesian Approaches to Synthesis.

Khochen, M., & Radford, J. (2012). Attitudes of teachers and headteachers towards inclusion in Lebanon. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16 (2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603111003671665

Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M., Betts, S. M., & Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher efficacy research 1998–2009: Signs of progress or unfulfilled promise? Educational Psychology Review, 23 (1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8

Lautenbach, F., & Heyder, A. (2019). Changing attitudes to inclusion in preservice teacher education: A systematic review. Educational Research, 61 (2), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1596035

Leach, D., & Duffy, M. L. (2009). Supporting students with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive settings. Intervention in School and Clinic, 45 (1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451209338395

Leonard, N. M., & Smyth, S. (2020). Does training matter? Exploring teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream education in Ireland. International Journal of Inclusive Education https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1718221

Loreman, T. (2014). Measuring inclusive education outcomes in Alberta, Canada. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18 (5), 459–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.788223

Loreman, T., Deppeler, J., Harvey, D., & Harvey, D. (2011). Inclusive education: Supporting diversity in the classroom . Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Lu, M., Zou, Y., Chen, X., Chen, J., He, W., & Pang, F. (2020). Knowledge, attitude and professional self-efficacy of Chinese mainstream primary school teachers regarding children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 72 , 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101513

McGregor, E. M., & Campbell, E. (2001). The attitudes of teachers in Scotland to the integration of children with autism into mainstream schools. Autism, 5 (2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005002008

Mitchell, D. (2014). Hvad der virker i inkluderende undervisning – Evidensbaserede undervisnings- oglæringsstrategier. Frederikshavn: Dafolo.

Morrier, M. J., Hess, K. L., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Teacher training for implementation of teaching strategies for students with autism spectrum disorders. Teacher Education and Special Education, 34 (2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406410376660

National Autistic Society. (2003). Autism and education: The ongoing battle . NAS.

Newschaffer, C. J., Croen, L. A., Daniels, J., Giarelli, E., Grether, J. K., Levy, S. E., ... & Reynolds, A. M. (2007). The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu. Rev. Public Health , 28 , 235-258 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007

Norwich, B., & Lewis, A. (2001). Mapping a pedagogy for special educational needs. British Educational Research Journal, 27 (3), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920120048322

Norwich, B. (2003). Is there a distinctive pedagogy for learning difficulties?. Occasional Papers- Association for Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 25–38.

Nowicki, E. A., & Sandieson, R. (2002). A meta-analysis of school-age children’s attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 49 (3), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912022000007270

Olley, J. G., Devellis, R. F., Devellis, B. M., Wall, A. J., & Long, C. E. (1981). The autism attitude scale for teachers. Exceptional Children, 47 (5), 371–372.

Paynter, J. M., Ferguson, S., Fordyce, K., Joosten, A., Paku, S., Stephens, M., ... & Keen, D. (2017). Utilisation of evidence-based practices by ASD early intervention service providers. Autism , 21 (2), 167-180 https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316633032

Qvortrup, A., & Qvortrup, L. (2018). Inclusion: Dimensions of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22 (7), 803–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412506

Rae, H., Murray, G., & McKenzie, K. (2010). Teachers’ attitudes to mainstream schooling. Learning Disability Practice, 13 (10), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.7748/ldp2010.12.13.10.12.c8138

Roberts, J. M., Keane, E., & Clark, T. R. (2008). Making inclusion work: Autism Spectrum Australia’s satellite class project. Teaching Exceptional Children, 41 (2), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990804100203

Rodden, B., Prendeville, P., Burke, S., & Kinsella, W. (2019). Framing secondary teachers’ perspectives on the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder using critical discourse analysis. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49 (2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2018.1506018

Rose, R., & Howley, M. (2007). The practical guide to special educational needs in inclusive primary classrooms . Sage.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. The Urban Review, 3 (1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02322211

Round, P. N., Subban, P. K., & Sharma, U. (2016). “I don’t have time to be this busy”. Exploring the concerns of secondary school teachers towards inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1079271

Ruble, L. A., Toland, M. D., Birdwhistell, J. L., McGrew, J. H., & Usher, E. L. (2013). Preliminary study of the autism self-efficacy scale for teachers (ASSET). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7 (9), 1151–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.06.006

Ruel, P., Poirier, N., & Japel, C. (2015). L’integration en classe ordinaire d’eleves presentant un trouble du spectre de l’autisme (TSA): La perception d’enseignantes du primaire. Revue De Psychoeducation, 43 (2), 37–61.

Ruijs, N. M., & Peetsma, T. T. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educational Research Review, 4 (2), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002

Salceanu, C. (2020). Development and inclusion of autistic children in public schools. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience , 11 (1), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.18662/brain/11.1/12

Schardt, C., Adams, M. B., Owens, T., Keitz, S., & Fontelo, P. (2007). Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 7 (1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-16

Segall, M. J., & Campbell, J. M. (2007). Autism inclusion questionnaire . Unpublished measure.

Segall, M. J., & Campbell, J. M. (2014). Factors influencing the educational placement of students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8 (1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.10.006

Simpson, R. L. (2004). Finding effective intervention and personnel preparation practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. Exceptional Children, 70 (2), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290407000201

Simpson, R. L., deBoer-Ott, S. R., & Smith-Myles, B. (2003). Inclusion of learners with autism spectrum disorders in general education settings. Topics in Language Disorders, 23 (2), 116–133.

Stauble, K. R. (2009). Teacher attitudes toward inclusion and the impact of teacher and school variables.Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1375. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1375

Su, X., Guo, J., & Wang, X. (2020). Different stakeholders’ perspectives on inclusive education in China: Parents of children with ASD, parents of typically developing children, and classroom teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (9), 948–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1502367

UNESCO. (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education . UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2002). Learning to be: A holistic and integrated approach to values education for human development: Core values and the valuing process for developing innovative practices for values education toward International understanding and a culture of peace . Bangkok: UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education.

UNESCO (2017). A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education . Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248254 .

UN General Assembly (1989). United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 . United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3 .

Van Roekel, E., Scholte, R. H., & Didden, R. (2010). Bullying among adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40 (1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0832-2

Van Steensel, F. J., Bögels, S. M., & Perrin, S. (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14 (3), 302.

Veritas Health Innovation. (2021). Covidence systematic review software [Mac]. Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org

Voltz, D. L., Brazil, N., & Ford, A. (2001). What matters most in inclusive education: A practical guide for moving forward. Intervention in School and Clinic, 37 (1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/105345120103700105

Wheatley, K. F. (2002). The potential benefits of teacher efficacy doubts for educational reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18 (1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00047-6

Williams, K., & Roberts, J. (2018). Understanding autism: The essential guide for parents (Vol. 3). Exisle Publishing.

Zheng, H. (2009). A review of research on EFL pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices. Journal of Cambridge Studies, 4 (1), 73–81.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The current paper was completed by the first author in part fulfilment of the MSc in Psychology and Well-being at Dublin City University. The second author acted as independent reviewer while the third and coordinating author was involved in supervision of the research including development, design, editing and proofreading.

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology, Dublin City University, Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland

Amy Russell, Aideen Scriney & Sinéad Smyth

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sinéad Smyth .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Russell, A., Scriney, A. & Smyth, S. Educator Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Mainstream Education: a Systematic Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 10 , 477–491 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00303-z

Download citation

Received : 24 August 2021

Accepted : 06 January 2022

Published : 19 January 2022

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00303-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Inclusive education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Autism Dev Lang Impair

- v.7; Jan-Dec 2022

Strategies in supporting inclusive education for autistic students—A systematic review of qualitative research results

Linda petersson-bloom.

Faculty of Learning and Society, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden; The National Agency for Special Needs Education and School (SPSM), Sweden

Mona Holmqvist

Faculty of Learning and Society, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

Associated Data

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-dli-10.1177_23969415221123429 for Strategies in supporting inclusive education for autistic students—A systematic review of qualitative research results by Linda Petersson-Bloom and Mona Holmqvist in Autism & Developmental Language Impairments

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-dli-10.1177_23969415221123429 for Strategies in supporting inclusive education for autistic students—A systematic review of qualitative research results by Linda Petersson-Bloom and Mona Holmqvist in Autism & Developmental Language Impairments

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-dli-10.1177_23969415221123429 for Strategies in supporting inclusive education for autistic students—A systematic review of qualitative research results by Linda Petersson-Bloom and Mona Holmqvist in Autism & Developmental Language Impairments

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-dli-10.1177_23969415221123429 for Strategies in supporting inclusive education for autistic students—A systematic review of qualitative research results by Linda Petersson-Bloom and Mona Holmqvist in Autism & Developmental Language Impairments

Background and Aim

Strategies to modify and adjust the educational setting in mainstream education for autistic students are under-researched. Hence, this review aims to identify qualitative research results of adaptation and modification strategies to support inclusive education for autistic students at school and classroom levels.

In this systematic review, four databases were searched. Following the preferred PRISMA approach, 108 studies met the inclusion criteria, and study characteristics were reported. Synthesis of key findings from included studies was conducted to provide a more comprehensive and holistic understanding.

Main Contribution

This article provides insights into a complex area via aggregating findings from qualitative research a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena is presented. The results of the qualitative analysis indicate a focus on teachers' attitudes and students' social skills in research. Only 16 studies were at the classroom level, 89 were at the school level, and three studies were not categorized at either classroom or school level. A research gap was identified regarding studies focusing on the perspectives of autistic students, environmental adaptations to meet the students' sensitivity difficulties, and how to enhance the students' inclusion regarding content taught and knowledge development from a didactic perspective.

Conclusions and Implications

Professional development that includes autism-specific understanding and strategies for adjusting and modifying to accommodate autistic students is essential. This conclusion may direct school leaders when implementing professional development programs. A special didactical perspective is needed to support teachers' understanding of challenges in instruction that autistic students may encounter.

Introduction