Teaching creative writing in primary schools: a systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity

- Open access

- Published: 17 June 2023

- Volume 51 , pages 1311–1330, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Georgina Barton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2703-238X 1 ,

- Maryam Khosronejad 2 ,

- Mary Ryan 2 ,

- Lisa Kervin 3 &

- Debra Myhill 4

9436 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

Teaching writing is complex and research related to approaches that support students’ understanding and outcomes in written assessment is prolific. Written aspects including text structure, purpose, and language conventions appear to be explicit elements teachers know how to teach. However, more qualitative and nuanced elements of writing such as authorial voice and creativity have received less attention. We conducted a systematic literature review on creativity and creative aspects of writing in primary classrooms by exploring research between 2011 and 2020. The review yielded 172 articles with 25 satisfying established criteria. Using Archer’s critical realist theory of reflexivity we report on personal, structural, and cultural emergent properties that surround the practice of creative writing. Implications and recommendations for improved practice are shared for school leaders, teachers, preservice teachers, students, and policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Re-imagining narrative writing and assessment: a post-NAPLAN craft-based rubric for creative writing

Radical rubrics: implementing the critical and creative thinking general capability through an ecological approach

Autofictionalizing Reflective Writing Pedagogies: Risks and Possibilities

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creative writing in schools is an important part of learning, assessment, and reporting, however, there is evidence globally to suggest that such writing is often stifled in preference to quick on-demand writing, usually featured in high-stakes testing (Au & Gourd, 2013 ; Gibson & Ewing, 2020 ). Research points to this negatively impacting particularly on students from diverse backgrounds (Mahmood et al., 2020 ). When teachers teach on-demand writing typical pedagogical traits are revealed, those that are often referred to as formulaic (Ryan & Barton, 2014 ). When thinking about creative writing, however, Wyse et al. ( 2013 ) noted that it involves the absence of structure and teaching creative writing requires an ‘open’ pedagogical approach for students to be given imaginative choice. By this, they mean that teachers need to consider less formulaic ways to teach writing so that students can experience different opportunities and ways to write creatively. They argued that if students are not given the flexibility to experiment through writing then their creativity might be stifled. Similarly, Barbot et al. ( 2012 ), who carried out a study with a panel of 15 experts of creative writing, posited that creative writing is when students draw on their imagination and other creative processes to create fictional narratives or writing that is ‘unusually original’. They also noted that creative writing is important for the development of students’ critical and creative thinking skills and ways in which they can approach life in creative ways.

Creative writing is defined in various ways in literature. Wang ( 2019 ) defined creative writing as a form of original expression involving an author’s imagination to engage a reader. Other definitions of creative writing involve the notion of children’s imagination, choice, and originality and much research has explored the concept of creativity within and through the writing process.

While creative writing is defined in various ways, and the many ways that it is treated in literacy education, this article is not concerned with the nature of the term per se. Rather, it focusses on research about creative writing and creativity in writing to understand how research unpacks the personal and contextual characteristics that surround creative writing practices. To this aim, we adopt a broad definition of creative writing as a form of original writing involving an author’s imagination and self-expression to engage a reader (Wang, 2019 ). Creative writing is important for children’s development (Grainger et al., 2005 ), allowing them to use their imagination and broaden their ability to problem-solve and think deeply. Creativity in writing refers to specific aspects within a writing product that can be deemed creative. Some examples include the use of senses and how a writer might engage a reader (Deutsch, 2014 ; Smith, 2020 ).

International research on teaching writing has indicated a loss in innovative or creative pedagogical practices due to the pressure on teachers to teach prescribed writing skills that are assessed in high-stakes tests (Göçen, 2019 ; Stock & Molloy, 2020 ), often resulting in specific trends including teaching a genre approach to writing (Polesel et al., 2012 ; Ryan & Barton, 2014 ). A comprehensive meta-analysis by Graham et al ( 2012 ), designed to identify writing practices with evidence of effectiveness in primary classrooms, found that explicitly teaching imagery and creativity was an effective teaching practice in writing. In addition, a review of methods related to teaching writing conducted by Slavin et al. ( 2019 ) included studies that statistically reported causal relationships between teacher practice and student outcomes. Common themes in Slavin et al’s ( 2019 ) quest for improving writing included comprehensive teacher professional development, student engagement and enjoyment, and explicit teaching of grammar, punctuation, and usage. While they did not specifically cite creativity, motivating environments and cooperative learning were important characteristics of writing programs.

This systematic literature review aims to share empirical international research in the context of elementary/primary schools by exploring creativity in writing and the conditions that influence its emergence. It specifically aims to answer the question: What influences the teaching of creative writing in primary education? And how can reflexivity theorise these influences? The review shares scholarly work that attempts to define personal aspects of creative writing including imagination, and creative thinking; discusses creative approaches to teaching writing, and shows how these methods might support students’ creative writing or creative aspects of writing.

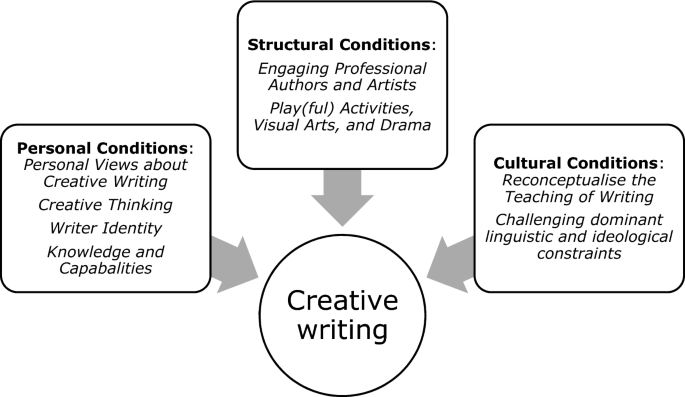

Writing is a complex process that involves students making decisions about word choice, sentence, and text structure, and ways in which to engage readers. Such decisions require a certain amount of reflection or at times deeper reflexive judgments by both teachers and students. Consequently, we draw on Archer’s ( 2012 ) critical realist theory of reflexivity to guide our review as research shows that reflexive thinking in practice can improve writing outcomes (Ryan et al., 2021 ). Archer ( 2007 ) highlights how reflexivity is an everyday activity involving mental processes whereby we think about ourselves in relation to our immediate personal, social, and cultural contexts. She suggests we make decisions through negotiating the connected emergences of personal properties (PEPs) related to the individual, structural properties (SEPs) related to the contextual happenings and cultural properties (CEPs) related to ideologies, each of which is influenced by the other developments. These decisions influence, and are influenced by, our subsequent actions. In applying reflexivity theory to writing (see Ryan, 2014 ), we cannot simply focus on the writing product, but should also interrogate the process of writing, that is, the influences on decision-making and design which are enabled or constrained through pedagogical practices in the classroom. Writing practices and outputs are formed through the interplay of personal, structural, and cultural conditions. Student decisions and actions about writing ensue through the mediation of personal (e.g. beliefs, motivations, interests, experiences), structural (e.g. curriculum, programs, testing regimes, teaching strategies, resources), and cultural (e.g. norms, expectations, ideologies, values) conditions. Therefore, teachers play an important role in facilitating the interplay of these conditions for their students and recontextualising curricula and policy (Ryan et al., 2021 ). For example, by enabling students’ agency and creating an authentic purpose for writing, teachers can balance the personal conditions of students (such as their motivation and interest) against the structural effects of the curriculum requirements. Using a reflexive approach to investigating the literature on creative writing we aim to reveal the personal, structural, and cultural conditions surrounding the study and the practice of creative writing. We argue that it is through the understanding of these conditions that we can theorise how a. students might make their writing more creative and b. how teachers might establish classroom conditions conducive to creativity.

The approach taken for this paper was guided by the PRISMA method (Moher et al., 2009 ) for conducting systematic literature reviews (see Table 1 ).

Our electronic search involved several databases: researchers’ library online catalogue, EBSCO host ultimate, ProQuest, Eric, Web of Science, Informit, and ScienceDirect. Using the following search terms: creativ* AND (‘teaching methods’ OR pedagog*) AND writing AND (elementary OR primary) to search titles and abstracts as well as limiting the search to peer-reviewed articles written in English within a 10-year timeframe (2011–2020), we initially retrieved 172 articles. Information about all 172 articles was input into a data spreadsheet including author, article title, journal title, volume and issue number, and abstract. Once completed, these articles were divided into two equal groups and two researchers were assigned to review the articles for relevancy against the following inclusion criteria:

Studies were peer-reviewed empirical research published in English;

Participants were primary students and/or teachers;

Students were not specifically English as a Second or Additional Language/Dialect learners (samples of culturally and linguistically diverse students in primary classrooms were included);

Studies were not carried out in curriculum areas other than English; and

Studies did not have a specific focus on digital technologies in the classroom.

For this systematic review, we were interested in the ways in which teachers thought about, understood, and taught the ‘creative’ aspect of writing.

The 25 studies that met the inclusion criteria were synthesised to review what influences the improvement of creative writing in primary education. We analysed the papers for how creative writing and/or creative aspects in writing were viewed as well as how teachers might best support students to develop reflexive capacities to improve the creative aspects of writing. We also identified any personal, structural, and/or cultural emergences that might impact on the effectiveness of students’ creative writing. Two of the authors read the entire articles and identified four main categories of research which were (1) understanding creative writing; (2) creative thinking and its contribution to writing; (3) creative pedagogy; and (4) what students can do to be more creative in their writing. These were cross-checked by the entire research team. Some of the papers fit more than one of these themes. In the next section, each theme is introduced and defined and then the articles that fall within the theme are reviewed.

Overall a total number of 25 articles had overlapping themes that included various personal and contextual aspects. Figure 1 shows what we have identified as the key themes under each category. In the next sections, we represent papers based on their main theme.

The personal, structural, and cultural conditions surrounding creative writing

Personal emergent properties

A total number of 13 articles were about what students can do to be more creative in their writing (Mendelowitz, 2014 ; Steele, 2016 ) and how teachers’ and students’ personal characteristics relate to the development of creative writing. These articles were mainly focussed on the personal emergent aspects of writing (Alhusaini & Maker, 2015 ; Barbot et al., 2012 ; Cremin et al., 2020 ; DeFauw, 2018 ; Dobson, 2015 ; Dobson & Stephenson, 2017 , 2020 ; Edwards-Groves, 2011 ; Healey, 2019 ; Lee & Enciso, 2017 ; Macken-Horarik, 2012 ; Ryan, 2014 ). The personal aspects identified in our review were (1) personal views about creative writing, (2) creative thinking, (3) writer identity, (4) learner motivation and engagement, and (5) knowledge and capabilities.

Personal views about creative writing

From our systematic review, we identified three articles exploring views about what creative writing is, and more specifically the role that it plays and the elements that make creative writing, in primary classrooms. One of these studies was focussed on the views and experiences of experts in writing (Barbot et al., 2012 ), whereas the other two investigated students’ perspectives and experiences (Alhusaini & Maker, 2015 ; Healey, 2019 ). Barbot et al’s ( 2012 ) work, for example, recognised that creative writing involves both cognitive and metacognitive abilities. This was determined by the expert panel of people whose work related to writing including teachers, linguists, psychologists, professional writers, and art educators. The panel were asked to complete an online survey that rated the relative importance of 28 identified skills needed to creatively write. Six broad categories were identified as a result of the responses and the rank given to each factor by the expert groups (See Table 2 ). They acknowledged that these features cross over various age groups from children to professional writers.

Findings suggested that each independent rater weighted different key components of creative writing as being more or less important for children. Overall, the findings showed.

a global ‘consensus’ across the expert groups indicated that creative writing skills are primarily supported by factors such as observation, generation of description, imagination, intrinsic motivation and perseverance, while the contributions of all of the other relevant factors seemed negligible (e.g. intelligence, working memory, extrinsic motivation and penmanship). (p. 218)

One factor that was ranked as critical by most respondents, but underemphasised by teachers, was imagination. Teachers’ work in classrooms around creative writing is complex due to the difficulty in defining imagination (Brill, 2004 ). Teachers also under-rated other aspects related to creative cognition.

Another study that explored students’ creativity in writing was conducted by Alhusaini and Maker ( 2015 ) in the south-west of the United States. Participants included 139 students with mixed ethnicities including White, Mexican American, and Navajo. This study involved six elementary/primary school teachers judging students’ writing samples of open-ended stories. To assess the work a Written Linguistic Assessment tool, which was based on the Consensual Assessment Technique [CAT] (Amabile, 1982 ) was implemented. According to Baer and McKool ( 2009 ), The CAT involves experts rating written artefacts or artistic objects by using their ‘sense of what is creative in the domain in question to rate the creativity of the products in relation to one another’ (p. 4). Interestingly, Alhusaini and Maker ( 2015 ) found the CAT to be effective in relation to interrater reliability. The authors do not share what the Judge’s Guidelines to Assess Students’ Stories entail. They mention the difference between technical quality and creativity and note that assessors were able to distinguish the differences between the two, but the reader is not made aware of the aspects of each quality. Overall, the study revealed that one of the most challenging problems in the field of creativity and writing is trying to measure creativity across cultures by using standardised tests. Such studies could have implications for other students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds as teachers become more aware of cultural nuances in constituting ‘creative’ in creative writing.

The final study we identified in this category was by Healey ( 2019 ). Healey employed an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and explored how eight children (11–12 Years of age) experienced creative writing in the classroom. He shared how children’s writing experiences were based on ‘the affect, embodiment, and materiality of their immediate engagement with activities in the classroom’ (p. 184). Results from student interviews showed three themes related to the experience of writing: the writing world (watching, ideas from elsewhere, flowing); the self (concealing and revealing, agency, adequacy); and schooled writing (standards, satisfying task requirements, rules of good writing). The author stated that children’s consciousness shifts between their imagination (The Writing World) and set assessment tasks (Schooled Writing). Both of these worlds affect the way children experience themselves as writers. Further findings from this work argued that originality of ideas and use of richer vocabulary improved students’ creative writing. Vocabulary improvement included diversity of word meanings, appropriate usage of words, words being in line with the purpose of the text; while originality of ideas featured creative and unusual (original) ideas—which in many ways is difficult to define.

Overall, when concerned with personal views and attitudes in creative writing, the two studies by Healey ( 2019 ) and Barbot et al. ( 2012 ) show contrasting findings about ‘imagination’ captured through the view of students and teachers, respectively. While Healey’s ( 2019 ) study suggests that children shift between their imagination and set assessment tasks in creative writing, Barbot et al. ( 2012 ) highlight the lack of attention to imagination among their participated teachers. Although these results cannot be generalised, they highlight the significance of understanding personal emergent properties that both students and teachers bring to the classroom and the way that they interact to affect the experience of creative writing for learners. From this theme, we suggest the importance of educators acknowledging students’ imagination through their definition of creative writing as well as providing quality time for students to choose what they write through imaginative thought. We now turn to creative thinking and related pedagogical approaches to teaching creative writing from the research literature.

Creative thinking

We identified two articles that were focussed on creative thinking and its contribution to writing (Copping, 2018 ; Cress & Holm, 2016 ). Copping ( 2018 ) explored writing pedagogy and the connections between children’s creative thinking, or a ‘new way of looking at something’ (p. 309), and their writing achievement. The study involved two primary schools in Lancashire, one in an affluent area and one in an underprivileged area. Approximately 28 children from each school were involved in two, 2-day writing workshops based on a murder mystery the children had to solve. Findings from this study revealed that to improve students’ writing achievement (1) a thinking environment needs to be created and maintained, (2) production processes should have value, (3) motivation and achievement increase when there is a tangible purpose, and (4) high expectations lead to higher attainment.

Cress and Holm’s ( 2016 ) study described a curricular approach implemented by a first-grade teacher and their class comprised 13 girls and 11 boys. The project known as the Creative Endeavours project aimed to develop creative thinking by (1) creating an environment of respect with a positive classroom climate. (2) offering new and challenging experiences, and (3) encouraging new ideas rather than praise. The authors argued that through peer collaboration and the flexibility to choose their own projects, children can become more authentically engaged in the writing process. The children wrote about their experiences and their choices, and reflected upon the projects undertaken. In this study, it was revealed that the children showed diversity in their writing assignments including presentation through sewing, photography, and drama. While there were only two papers in this particular theme, their findings are supported by systematic reviews (Graham et al., 2012 ; Slavin et al., 2019 ) that emphasise not only new ways of exploring a range of concepts for learning but also the creation of motivating environments for improving writing (Copping, 2018 ). In addition to the significance of positive and encouraging learning environments, these two studies suggest that setting ‘high expectations’ or ‘challenging experiences’ are conducive to creative thinking however, teachers would need to set appropriate, reflexive conditions for this to occur.

Writer identity

Studies in this category revolve around choice and learner writer identity. The study carried out by Dobson and Stephenson ( 2017 ) focussed on developing a community of writers involving 25 primary school pupils from low socio-economic backgrounds. The project was offered over 2 weeks and featured a number of creative writing workshops. The authors applied the theoretical frameworks of practitioner enquiry and discourse analysis to explore the children’s creative writing outputs. They argued that the workshops, which promoted intertextuality and freedom for the children as writers, enabled a shifting of their ‘writer’ identities (Holland et al., 1998). Dobson and Stephenson ( 2017 ) showed that allowing students to make decisions and choices in regard to authentic writing purposes supported a more flexible approach. They recommend stronger partnerships between schools and universities in relation to research on creative writing, however, it would be important for these relationships to be sustainable.

The second paper on this theme is by Ryan ( 2014 ) who noted that writing is a complex activity that requires appropriate thinking in relation to the purpose, audience, and medium of a variety of texts. Writers always make decisions about how they will present subject matter and/or feelings through all of the modes. Ryan ( 2014 ) suggested that writing is like a performance ‘whereby writers shape and represent their identities as they mediate social structures and personal considerations’ (p. 130). The study analysed writing samples of culturally and linguistically diverse Australian primary students to uncover the types of identities students shared. It found that three different types of writers existed—the school writers who followed teacher instructions or formulas to produce a product; the constrained writers who also followed instructions and formulas but were able to add in some authorical voice; and the reflexive writers who could show a definite command of writing and showed creative potential. Ryan ( 2014 ) argued that teachers’ practices in the classroom directly influence the ways in which students express these identities. She stated that when students are provided choices in writing, they are more able to shape and develop their voices. Such choices would need to include quality time and support to be reflexive in the decisions being made by the students.

The Teachers as Writers project (2015–2017) was conducted by Cremin, Myhill, Eyres, Nash, Wilson, and Oliver. In a recent paper ( 2020 ), the team reported on a collaborative partnership between two universities and a creative writing foundation. Professional writers were invited to engage with teachers in the writing process and the impact of these interactions on classroom teaching practices was determined. Data sets included observations, interviews, audio-capture (of workshops, tutorials and co-mentoring reflections), and audio-diaries from 16 teachers; and a randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 32 primary and secondary classes. An intervention was carried out involving teachers writing in a week long residence with professional writers, one-on-one tutorials, and extra time and space to write. They also continued learning through two Continuing Professional Development (CPD) days. Results showed that teachers’ identities as writers shifted greatly due to their engagement with professional authors. The students responded positively in terms of their motivation, confidence, sense of ownership, and skills as writers. The professional authors also commented on positive impacts including their own contributions to schools. Conversely, these changes in practice did not improve the students’ final assessment results in any significant way. The authors noted that assuming a causal relationship between teachers’ engagement with writing workshops and students’ writing outcomes was spurious. They, therefore, developed further research building on this learning.

Knowledge and capabilities

The role of knowledge and capability is central to the articles in this category. In Australia, Macken-Horarik ( 2012 ) reported on the introduction of a national curriculum for English. This article drew on Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) by investigating the potential of Halliday’s notion of grammatics for understanding students’ writing as acts of creative meaning in context. Macken-Horarik ( 2012 ) argued that students needed to know deeply about language so that they could make creative decisions with their writing. She outlined that a ‘good enough’ grammatics would assist teachers in becoming comfortable with ‘playful developments in students’ texts and to foster their control of literate discourse’ (p. 179).

A project carried out by Edwards-Groves in 2011 highlights the role of knowledge about digital technologies in writing practices. 17 teachers in primary classrooms in Australia were asked to use particular digital technologies with their students when constructing classroom texts. Findings showed that an extended perspective on what counts as writing including the writing process was needed. Results revealed that collaborative methods when constructing diverse texts required teachers to rethink pedagogies towards writing instruction and what they consider as writing. It was argued that technology can be used to enhance creative possibilities for students in the form of new and dynamic texts. In particular, it was noted that teachers and students should be aware that digital technologies can both constrain and/or enable text creation in the classroom depending on a number of variables including knowledge and understanding, locating resources and logistical issues such as connectivity and reliability.

In addition, Mendelowitz’s ( 2014 ) study argued that nurturing teachers’ own creativity assisted their ability to teach writing more generally. She noted several ‘interrelated variables and relationships that still need to be given attention in order to gain a more holistic understanding of the challenges of teaching creative writing’ (p. 164). According to Mendelowitz ( 2014 ), elements that impacted on these challenges include teachers’ school writing histories, conceptualisations of imagination, classroom discourses, and pedagogy. Documenting teachers’ work through interviews and classroom observations by the researcher, the study found that teachers need to be able to define imagination and imaginative writing and know what strategies work best with their students. She noted that the teacher’s approaches to teaching writing ‘powerfully shaped by the interactions between their conceptualisations and enactments of imaginative writing pedagogy’ (p. 181) and that these may either limit or create a space for students to be more creative with their writing.

Such Personal Emergent Properties show that individual attributes of both teachers and students are important in learning creative writing. The next section of the paper explores the articles that shared various structural and cultural properties.

Structural emergent properties

In the subset of structural emergent properties, we mainly identified pedagogical approaches for creative writing that explored primary school learning and teaching (Christianakis, 2011a ; Christianakis, 2011b ; Coles, 2017 ; DeFauw, 2018 ; Hall & Grisham-Brown, 2011 ; Portier et al., 2019 ; Rumney et al., 2016 ; Sears, 2012 ; Steele, 2016 ; Southern et al., 2020 ; Yoo & Carter, 2017 ). These pedagogical approaches were aimed at addressing issues related to personal emergent properties such as motivation and engagement, and confidence in writing. The two categories of writing pedagogies were those that engaged professional authors and artists in teaching about creative writing, and the approaches that involved play(ful) activities, and use of visual arts, and drama.

Engaging professional authors and artists

Interestingly, many of the studies used literary forms and/or professional creative authors to spike interest and motivation in the students. Coles’ ( 2017 ) study, for example, used a garden-themed poetry writing project to support 9–10-year-old children’s creative writing in a London primary school. The 5-week project partnered with a professional creative writing organisation that facilitated the Ministry for Stories (MoS) writing centres across the USA. The study found that the social relationships created through this partnership allowed for a more inclusive and socially generative model of creativity. This meant that teachers should not just include creative aspects in assessment rubrics but rather recognise that creativity is encouraged through imagination and working with others. The researchers found improvements in the children’s participation in classroom writing activities as well as diversity in the ways they expressed their writing. The approach valued ‘rich means of expression rather than a set of rules to be learnt’ (p. 396). They also acknowledged issues associated with school–community partnerships including the sustainability of the practice.

Similarly, Rumney et al. ( 2016 ) found that using creative multimodal activities increased students’ confidence and motivation for writing. The study implemented the Write Here project with over 900 children in 12 primary and secondary schools. The study involved the children visiting local art galleries to work with professional authors and artists. Case studies were presented about pre-writing activities, the actual gallery work and post-gallery follow-up sessions. It aimed to improve students’ social development and literacy outcomes through diverse learning activities such as visual art and play in different contexts such as art galleries and classrooms. Like Coles’ ( 2017 ) study, this project showed that creative activities (e.g. talking about and acting out pictures; using story maps; backwards writing and planning) engaged students more than just teaching skills.

In addition, DeFauw’s ( 2018 ) study had student-centred learning and leadership at the core when working with a children’s book author for one year. The collaboration involved three face-to-face sessions with the author as well as online communication through blog posts. Data included recorded interactions, readings and pre and post interviews with teachers ( n = 9), students ( n = 36), and the author. The partnership showed that students’ interest was activated and sustained due to the situational context as well as the extended time given to students to interact with the author. The project improved students’ interest in and motivation to write as a result of engaging with authors and hearing about their own experience and writing strategies. It also found that teachers gained more confidence to support students’ exploration of writing in more creative ways. The creative pedagogies were also used in addressing issues related to creative writing outcomes for students, including teachers’ lack of confidence about pedagogies (Southern et al., 2020 ). Through a creative social enterprise approach, the authors facilitated professional development and learning involving artist-led activities for students. The program called Zip Zap had been implemented in schools in Wales and England, and data were collected through focus groups with teachers, students, and parents/carers. Observations of some of the professional development workshops were also video recorded. Third space theory was used to describe the collaborative practice between educators and artists that supported students’ creative writing outcomes. It was noteworthy that involving ‘creative’ practitioners largely focussed on the specific strategies that could be used in classrooms, to which our next section now turns.

Play(ful) activities, visual arts, and drama

Much research explores how to best support students who find writing difficult. Sears’ research ( 2012 ) is a case in point. The author shared how visual arts may be an effective way to improve struggling students with writing. They argued that the visual arts can provide ways of ‘accessing and expressing [student] ideas and ultimately opening a world of creative possibilities’ (p. 17). In the study, six third-grade students engaged with drawing and painting as pre-writing strategies, leading to the creation of poems based on the artworks. The students’ final poems were assessed and showed improved knowledge of all 6 technical categories in writing: ideas, organisation, fluency, voice, word choice, and conventions. The author also argued that students’ motivation to write increased as a result of the visual art activities.

A study by Portier et al. ( 2019 ) investigated approaches to teaching writing that were motiving and engaging for students. Involving 10 northern rural communities in Canada, the project implemented collaborative, play(ful) learning activities alongside sixteen teachers and their students. Interestingly, the study, like many others in our review, found a disconnect ‘between the achievement of curricular objectives and the implementation of play(ful) learning activities’ (p. 20); an approach valued in early childhood education. The students were supported through action research projects in creating texts with different purposes. Students’ motivation as well as samples of work were analysed and showed that student interest areas and collaborative approaches benefited both teachers and students. Further research on how reflexive thinking might have influenced these benefits is recommended.

Similarly, Lee and Enciso ( 2017 ) highlighted the importance of motivation and engagement in their study. In a collaboration with Austin Theatre Alliance, Lee and Enciso ( 2017 ) investigated how dramatic approaches to teaching, such as through expanded imagination and improvisation, can improve students’ story writing. They argued that the students’ motivation to write was also increased. The study was carried out through a controlled quasi-experimental study over 8 weeks of story-writing and drama-based programs. 29 third-grade classrooms in various schools, located in an urban district of Texas, were involved. The study also pre- and post-tested the students’ writing self-efficacy through story building. The study found that students were more able to use their cultural knowledge such as ‘culturally formed repertoires of language and experience to explore and express new understandings of the world and themselves…’ (p. 160) for creative writing purposes but needed more quality resources to support opportunities such as the Literacy for Life program. A most important finding was that for children who experience poverty, drama-based activities developed and led by teaching artists were extremely powerful and allowed the students to express themselves in entertaining ways. We do note that ‘entertainment’ and or engagement might mean different things for different students so reflexive approaches to deciding what these are would be necessary.

Steele’s ( 2016 ) study also looked at supporting teachers’ work in the classroom. Involving 6 out of 20 teacher workshop participants in Hawaii, this exploratory case study utilised observations, interview, and portfolio analyses of teacher and student work. Findings from the study showed that some teachers relished moving away from everyday ‘typical’ practice and increased student voice and choice. Other teachers, however, found it difficult to take risks and hence respond to student needs and ideas.

Dobson and Stephenson’s ( 2020 ) study focussed on the professional development of primary school teachers using drama to develop creative writing across the curriculum. The project was sponsored by the United Kingdom Literacy Association and ran for two terms in a school year. Researchers based the research on a collaborative approach involving academics and four teachers working with theatre educators to use process drama. Data sets included lesson observations, notes taken during learning conversations, and interviews with the teachers. The findings showed that three of the four teachers resisted some of the methods used such as performance; resulting in a lack of child-centred learning. The remaining teacher could take on board innovative practice, which the researchers attributed to his disposition. The study argued that these teachers, while a small participant group, needed more support in feeling confident in implementing new and creative approaches to teaching writing.

The final study, identified as addressing creative pedagogies for creative writing, was carried out by Yoo and Carter ( 2017 ) as professional development for teachers. Data included teacher survey responses and field notes taken by the researchers at each workshop (note: number of workshops and participants is unknown). The program aimed to investigate how emotions play a role in teachers’ work when teaching creative writing. The researchers found that intuitive joint construction of meaning was important to meet the needs of both primary and secondary teachers. A community of practice was established to support teachers’ identities as writers (see also Cremin et al., 2020 ). Findings showed that teachers who already identified as writers engaged more positively in the workshop.

These studies presented some approaches for teachers to consider how to teach creative writing. For example, the need to value unique spaces for students to write, including authentic connections with people and places outside of school environments was shared. Further, the need for quality stimuli and time for writing was acknowledged. Several other studies identified that blended teaching approaches to support student learning outcomes in the area of creative writing is important for schools and teachers to consider. We do acknowledge there may be other methods available to support students in creative writing, however, understanding what types of SEPs are impacting on teaching creative writing is an important step in determining improvements in schools.

Cultural emergent properties

Christianakis ( 2011a , 2011b ) wrote two papers about children’s creative text development with an emphasis on the cultural aspects. The first was an ethnographic study across 8 months with a year five class in East San Francisco Bay. The study included audio recording the students’ conversations and analysing over 900 samples of work. In the classroom, students were involved in a range of meaning-making practices including those that were arts-based and multimodal. The conversations with the students involved the researcher asking questions such: tell me more about this drawing, how did you come up with the idea? or why did you make this choice? The study found that there was a need for schools to reconceptualise the teaching of writing ‘to include not only orthographic symbols, but also the wide array of communicative tools that children bring to writing’ (p. 22). The author argued that unless corresponding institutional practices and ideologies were interrogated then improved practice was unlikely.

Christianakis’ ( 2011b ) second article, from the same project, explored more specifically the creation of hybrid rap poems by the children. She explicated how educators needed to negotiate and challenge dominant practices in primary classroom literacy learning. Like many studies before, a strong recommendation was to be more inclusive of youth popular cultures and culturally relevant literacies for students to be more engaged in creative writing practices. For Christianakis, culturally relevant literacies meant practices that embraced diversity in class and race and accounted for, and challenged, the dominant hegemonic curriculum that ‘privileges a traditional canon’ (p. 1140).

In summary, we found several themes under PEPs that could be considered for further research including those outlined in Table 3 below.

Discussion and implications for classroom practice

From this systematic literature review, several positions were exposed about the personal, structural, and cultural influences (Archer, 2012 ; Ryan, 2014 ) on teaching creative writing. These include limited teacher and student knowledge of what constitutes creative writing (Personal Emergent Properties [PEPs]), and no shared understanding or expectation in relation to creative writing pedagogy in their context (Cultural Emergent Properties [CEPs]). The negative impact of standardised testing and trending approaches on how teachers teach writing (CEP; Structural Emergent Properties [SEPs]) could also be considered (see AUTHORS 1 and 3, 2014 for example). In addition, teachers’ poor self-efficacy in terms of teaching creative writing (PEP); a paucity of quality professional development about teaching and assessing creative writing (SEP); and issues related to the sustainability of creative approaches to teach writing (SEP; CEP) need to be considered by leaders and teachers in schools. Our literature review advances knowledge about creative writing by revealing two interconnected areas that affect creative writing practices. Findings suggest that a parallel focus on personal conditions and contextual conditions—including structural and cultural—has the potential to improve creative writing in general. Below, we share some implications and recommendations for improved practice by focussing on both (1) personal views about creative writing and (2) the structural and cultural aspects that affect creative writing practices at schools.

Focussing on personal views about creative writing

School leaders and teachers must clearly define what creative writing is, what key skills constitute creative writing.

From our search it was apparent that schools and their educators often do not have a clear idea or indeed a shared idea as to what constitutes creative writing in relation to their own context. Without a well-defined focus for creative writing students may find it difficult to know what is required in classroom tasks and assessment. In addition, when planning for creative writing in school programs, teachers should consider flexible learning opportunities and choice for their students when developing their creative writing skills. Such flexibility should also involve choice of topic, ways of working (e.g. peer collaboration, individual activities etc.), and open discussions led by students in the classroom as shown throughout this paper. It would also be important for leaders and teachers to interrogate current approaches to teaching writing which we argued in the introduction to be formulaic and genre based.

Improve teacher self-efficacy, confidence, and content knowledge in teaching writing

Many of our studies showed that teachers who lacked confidence about writing themselves had less knowledge and skills to teach writing than those that may have participated in projects encouraging ‘teachers as writers’. Further, improved knowledge of grammar (as highlighted in Macken-Horarik’s, 2012 work); talk about writing in the classroom and other spaces (Cremin et al., 2020 ) and the writing process (see Ryan, 2014 ) could assist teachers in becoming more confident to take risks in the classroom with their students. Above all being playful about writing through extended conversations and practices is required.

Focussing on the structural and cultural resources

Improve training and further professional development and learning about teaching and assessing creative writing.

In order for the above personal attributes to be improved, further professional development and learning are required. Many of the papers presented throughout this review demonstrated the powerful impact of immersive professional learning for teachers. Working alongside professional authors, researchers, drama practitioners, visual artists, poets, for example, provided positive opportunities for teachers to learn about writing but also to feel more confident to teach it without imposing strict boundaries on students. We argue for professional development to be both formal and informal including such approaches as coaching and mentoring in the classroom. Demonstrated practice alongside the teacher is also recommended. This, in turn, would address the ongoing issue of creative writing being stifled for students in the classroom context.

Consider sustainability of creative pedagogic approaches and spaces for creative writing in curriculum planning

Many of the studies throughout this paper shared creative approaches to teaching writing but there were concerns that some of these methods may not be sustainable. It is important for school leaders to support the work of teachers in relation to teaching creative writing. We acknowledge that there is increasing uncertainty and scrutiny surrounding teachers’ everyday work (Knight, 2020 ), however, continued engagement in learning about and participating in creative pedagogy for writing is highly recommended. In addition, the studies suggested the provision of appropriate and authentic spaces in which students could creatively write and these often included spaces outside of the normal classroom environment and arts-based approaches implemented in such spaces. Teachers should be encouraged to collaborate and take risks rather than follow predetermined strategies for every lesson. A whole of school practice can be developed with important conversations about the ideologies that inform the school’s approach to writing.

Schools should not stifle creativity in the classroom due to the infiltration of standardised and/or trending approaches to teaching and assessing writing

It is evident that pedagogical approaches to teaching writing have been stifled by more formulaic methods aiming to meet expectations of standardised tests despite other evidence showing the benefits of more productive, engaging, and creative approaches to teaching writing as highlighted above. This can be particularly the case for students from non-dominant backgrounds where writing about cultural and life experiences through innovative practices has been proven to empower their voices (Johnson, 2021 ). The research shows that when students are offered rigid structures of texts, no choice of genres, and indeed word lists, their own decisions about writing are diminished (Ryan & Barton, 2013 ). It has been proven that students’ engagement and motivation to write can increase when they are able to write directly from their own experience or in social groups. It is therefore recommended that school leaders and teachers reconsider their ideologies about writing and explicitly indicate the importance of real-world purposes for writing—not just formulised, quick writing as usually included in external tests—but also those that encourage students’ growth in imagination, creativity, and innovative thought.

This systematic review used a lens of reflexivity to situate writing as a process of active and creative design whereby students make conscious decisions about their writing, with guidance from their teachers. As explained, we see creative writing as writing that engages a reader and, therefore, requires knowledge of authorial voice and appropriate word choice. This involves reflexive decisions relating to personal, structural, and cultural emergent properties. Predominant in the literature was the striking influence of CEPs or the values and expectations ascribed to writing, which in turn influence the strategies and resources (SEPs) and the experiences and motivations of students and teachers in the classroom (PEPs). Writing is about more than a series of perfectly formed sentences in a recognisable structure, which dominates conceptions of writing through high-stakes testing globally. It is about engagement with the expressive self, emergent identities, and relationships to places and people and above all communicating to and/or entertaining a reader. Without quality education in creative writing, society is at risk of losing an art form that is important for cultural practice and expression (Watson, 2016 ).

We do foresee several limitations with such a review, largely related to the positive nature of the studies in relation to creative approaches to teaching writing as well as the relatively small numbers of participants in some of the studies. Most of the studies reported favourably on the approaches taken by teachers to influence student motivation towards writing with limited comments about adverse effects. In terms of contributions, the notion that students need to draw on creative thought and ideas when writing means that teachers and leaders must think about diverse ways to teach writing. We argue, on the basis of the findings, that inquiry-based and reflexive professional learning projects about creativity are crucial for primary classrooms: what creativity means in different contexts and for different writers; how it is enabled; and the decisions and actions that emerge when creative and reflexive design guide our approach to classroom writing. Without quality knowledge and understanding of what creative writing is and how it is taught, we would be at risk of diminishing students’ self-expression and ability to communicate meaning to others in literary forms.

Alhusaini, A. A., & Maker, C. J. (2015). Creativity in students’ writing of open-ended stories across ethnic, gender, and grade groups: An extension study from third to fifth grades. Gifted and Talented International, 30 (1–2), 25–38.

Article Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Children's artistic creativity: Detrimental effects of competition in a field setting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 8 (3), 573–578.

Archer, M. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Archer, M. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity . Cambridge University Press.

Au, W., & Gourd, K. (2013). Asinine assessment: Why high-stakes testing is bad for everyone, including English teachers. English Journal , 14–19.

Baer, J., & McKool, S. (2009). Assessing creativity using the consensual assessment technique . IGI Global.

Barbot, B., Tan, M., Randi, J., Santa-Donato, G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2012). Essential skills for creative writing: Integrating multiple domain-specific perspectives. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7 (3), 209–223.

Brill, F. (2004). Thinking outside the box: Imagination and empathy beyond story writing. Literacy, 38 (2), 83–89.

Christianakis, M. (2011a). Children’s text development: Drawing, pictures, and writing. Research in the Teaching of English, 46 (1), 22–54.

Christianakis, M. (2011b). Hybrid texts: Fifth graders, rap music, and writing. Urban Education, 46 (5), 1131–1168.

Coles, J. (2017). Planting poetry: Sowing seeds of creativity in a year 5 class changing english. Studies in Culture and Education, 24 (4), 386–398.

Google Scholar

Copping, A. (2018). Exploring connections between creative thinking and higher attaining writing. Education, 46 (3), 307–316.

Cremin, T., Myhill, D., Eyres, I., Nash, T., Wilson, A., & Oliver, L. (2020). Teachers as writers: Learning together with others. Literacy, 54 (2), 49–59.

Cress, S. W., & Holm, D. T. (2016). Creative endeavors: Inspiring creativity in a first-grade classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44 (3), 235–243.

DeFauw, D. L. (2018). One school’s yearlong collaboration with a children’s book author. Reading Teacher., 72 (30), 355–367.

Deutsch, L. (2014). Writing from the senses: 59 exercises to ignite creativity and revitalize your writing . Shambhala Publications.

Dobson, T. (2015). Developing a theoretical framework for response: Creative writing as response in the Year 6 primary classroom. English in Education, 49 (3), 252–265.

Dobson, T., & Stephenson, L. (2017). Primary pupils’ creative writing: Enacting identities in a Community of Writers. Literacy, 51 (3), 162–168.

Dobson, T., & Stephenson, L. (2020). Challenging boundaries to cross: Primary teachers exploring drama pedagogy for creative writing with theatre educators in the landscape of performativity. Professional Development in Education, 46 (2), 245–255.

Edwards-Groves, C. (2011). The multimodal writing process: Changing practices in contemporary classrooms. Language and Education, 25 (1), 49–64.

Gibson, R., & Ewing, R. (2020). Transforming the curriculum through the arts . Springer.

Göçen, G. (2019). The effect of creative writing activities on elementary school students’ creative writing achievement, writing attitude and motivation. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15 (3), 1032–1044.

Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 (4), 879.

Grainger, T., Goouch, K., & Lambirth, A. (2005). Creativity and writing: Developing voice and verve in the classroom . Routledge.

Hall, A. H., & Grisham-Brown, J. (2011). Writing development over time: Examining preservice teachers' attitudes and beliefs about writing. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 32 (2), 148–158.

Healey, B. (2019). How children experience creative writing in the classroom. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 42 (3), 184–194.

Johnson, T. (2021). Identity placement in social justice issues through a creative writing curriculum . Unpublished Masters thesis. Hamline University.

Knight, R. (2020). The tensions of innovation: Experiences of teachers during a whole school pedagogical shift. Research Papers in Education, 35 (2), 205–227.

Lee, B. K., & Enciso, P. (2017). The big glamorous monster (or Lady Gaga’s adventures at sea): Improving student writing through dramatic approaches in schools. Journal of Literacy Research, 49 (2), 157–180.

Macken-Horarik, M. (2012). Why school English needs a ‘good enough’ grammatics (and not more grammar). Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education, 19 (2), 179–194.

Mahmood, M. I., Mobeen, M., & Abbas, S. (2020). Effect of high-stakes exams on creative writing skills of ESL learners in Pakistan. Research Journal of Social Sciences and Economics Review, 1 (3), 169–179.

Mendelowitz, B. (2014). Permission to fly: Creating classroom environments of imaginative (im)possibilities. English in Education, 48 (2), 164–183.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6 (7), e1000097.

Polesel, J., Dulfer, N., & Turnbull, M. (2012). The experience of education: The impacts of high stakes testing on school students and their families . The Whitlam Institute.

Portier, C., Friedrich, N., & Stagg Peterson, S. (2019). Play(ful) pedagogical practices for creative collaborative literacy. Reading Teacher, 73 (1), 17–27.

Rumney, P., Buttress, J., & Kuksa, I. (2016). Seeing, doing, writing: The write here project. SAGE Open, 6 (1).

Ryan, M. (2014). Writers as performers: Developing reflexive and creative writing identities. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 13 (3), 130–148.

Ryan, M., & Barton, G. M. (2013). Working towards a ’’thirdspace' in the teaching of writing to middle years students. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years , 21 (3), 71–81.

Ryan, M., & Barton, G. (2014). The spatialized practices of teaching writing in Australian elementary schools: Diverse students shaping discoursal selves. Research in the Teaching of English , 303–329.

Ryan, M., & Daffern, T. (2020). Assessing writing: Teacher-led approaches. Teaching Writing: Effective approaches for the middle years.

Ryan, M., Khosronejad, M., Barton, G., Kervin, L. & Myhill, D. (2021). A reflexive approach to teaching writing: Enablements and constraints in primary school classrooms. Written Communication.

Sears, E. (2012). Painting and poetry: Third graders’ free-form poems inspired by their paintings. Journal of Inquiry and Action in Education, 5 (1), 17–40.

Slavin, E. R., Lake, C., Inns, A., Baye, A., Dachet, D., & Haslam, J. (2019). A quantitative synthesis of research on writing approaches in years 3 to 13 . Education Endowment Foundation.

Smith, H. (2020). The writing experiment: Strategies for innovative creative writing . Routledge.

Southern, A., Elliott, J., & Morley, C. (2020). Third space creative pedagogies: Developing a model of shared CPDL for teachers and artists to support reading and writing in the primary curricula of England and Wales. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 8 (1), 24–31.

Steele, J. (2016). Becoming creative practitioners: Elementary teachers tackle artful approaches to writing instruction. Teaching Education, 27 (1), 1037829. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2015.1037829

Stock, C., & Molloy, K. (2020). Where are the students?: Creative writing in a high-stakes world. Idiom, 56 (3), 19.

Wang, L. (2019). Rethinking the significance of creative writing: A neglected art form behind the language learning curriculum. Cambridge Open-Review Educational Research, 6 , 110–122.

Watson, V. M. (2016). Literacy is a civil write: The art, science, and soul of transformative classrooms. Social Justice Instruction: Empowerment on the Chalkboard , 307–323.

Wyse, D., Jones, R., Bradford, H., & Wolpert, M. A. (2013). Teaching English, language and literacy . Routledge.

Yoo, J., & Carter, D. (2017). Teacher emotion and learning as praxis: Professional development that matters. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42 (3), 38–52.

Download references

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The project that informed this systematic review was on the teaching of writing and funded by the Australian Research Council. The views expressed here are in no way reflective of the ARC.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield, QLD, Australia

Georgina Barton

Australian Catholic University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Maryam Khosronejad & Mary Ryan

Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

Lisa Kervin

Centre for Research in Writing, The University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Debra Myhill

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Georgina Barton .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

Etical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Barton, G., Khosronejad, M., Ryan, M. et al. Teaching creative writing in primary schools: a systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity. Aust. Educ. Res. 51 , 1311–1330 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00641-9

Download citation

Received : 19 July 2022

Accepted : 26 May 2023

Published : 17 June 2023

Issue Date : September 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00641-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Creative writing

- Primary classrooms

- Teaching writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Teaching Expertise

- Classroom Ideas

- Teacher’s Life

- Deals & Shopping

- Privacy Policy

51 Creative Writing Activities For The Classroom: Comics, Prompts, Games, And Pretend Play

January 4, 2024 // by Milka Kariuki

Creative writing can be tough for learners of any age. From knowing where to start to establishing the vocabulary to develop their story, there are a bunch of different skills they’ll need to perfect their creative writing pieces. There are so many creative writing activities out there, but which ones are best for your kiddos? Our list of 51 creative writing activities is the perfect place to start looking if you’ve got a creative writing unit coming up! Read on and see which ones might grab your little writers’ attention!

1. Make Your Own Comic Books

We bet your kiddos just love comic books! Let them create their very own in the style of the super popular Diary of a Wimpy Kid books! Encourage your students to come up with their own plot, dialogue, and illustrations to spark their creativity. Even your most reluctant writers will love this fun activity!

Learn More: Puffin Schools

2. Mad Libs

Using Mad Libs is a super popular way to develop your little creative writers! Use these free printables to get their creative juices flowing as they try to come up with words to fill the gaps to create weird and wonderful new stories. The best thing is that you can use these printables as many times as you like as their answers will be different each time!

Learn More: Teacher Vision

3. Flash Fiction

Flash fiction is a fantastic way to get your kiddies writing creatively while keeping things short and sweet! Use the range you prompts included in this resource to challenge them to write a creative story in less than 100 words. Flash fiction is amazing because your students won’t be overwhelmed by a huge writing task and it also means that your more confident writers will need to focus on the quality of their work, not the quantity!

Learn More: TES

4. Write a Story Based on the Ending

Test your students’ creativity by providing them with writing prompts that start at the end! In backward story writing, your budding writers will need to plan and pen a story that eventually leads to the ending you give them. This idea is a fantastic way to turn your traditional creative writing lesson on its head and in many ways take the pressure off your kids, as ending their stories is often the most difficult part for them!

Learn More: Teachers Pay Teachers

5. Found Poetry

Your learners will love this fun and creative found poetry activity. You can encourage them to collect words or a group of words from a favorite story or song then write them on a piece of paper or cut them out of a printed page. The overall goal is to have them rearrange the words differently to make an interesting poem with a unique writing style or genre!

Learn More: Homeschooling Ideas

6. Picture Dictionary

A picture dictionary is a brilliant way to support every member of your younger elementary class in their creative writing. The words paired with pictures give your writers a ‘dictionary’ that they can use pretty independently, so your less confident writers or non-native English-speaking students can still access your writing lessons!

Learn More: Twinkl

7. Creative Journal Writing

Why not start a creative journal with your kiddos? Have them engage in daily journaling activities by giving them a different creative prompt each day. For instance, write a story about what would happen if dogs took over the world or what would you do if you were the security guard at a zoo and someone stole an animal? The fun is never-ending with these prompts!

Learn More: Think Written

8. Roll a Story

Roll-a-Story is one of the best ways to help any of your kids who are suffering from a bout of writer’s block! They’ll roll the dice to discover the character, setting, and problem for their story then set to work weaving their creative tale! It could be a story about a wise doctor being chased by a mysterious creature in a casino, or maybe a rich artist losing their wallet in a library. Then it’s up to your students to fill in the gaps!

Learn More: TPT

9. Pass-it-on Story Writing

There’s no telling quite where this fun writing game will end up! Start by writing the first sentence of a story on a piece of paper then pass it around your class, having your kids come up with a sentence that continues the story. The paper is then passed around the whole class until every student has contributed. Finally, once it makes its way back to you, read out your collaborative story to the whole class!

Learn More: Minds In Bloom

10. Picture Writing Prompts

Creative writing prompts activities test not only your little ones’ imaginations but also their ability to craft a story and dialogue from that. Display an intriguing picture prompt for your class and have a discussion about it, recording their ideas. You could discuss what the person or animal in the picture is doing or what they’re thinking, where they think the picture was taken, and much more. They can use your collective notes to inspire their story!

Learn More: Pandora Post

11. What’s the Question?

What’s the Question is a simple, yet super engaging game that requires your young learners to think creatively. Spark their creativity by writing an answer on the whiteboard such as “the moon would explode,” and task your kiddos with coming up with a question to match it. There’ll be lots of laughs as everyone shares what they came up with!

Learn More: That Afterschool Life

12. Creative Writing Printables

This website is absolutely full of quick and fun graphics for children that’ll encourage their creative writing! The cute graphics and simple directions make it an easy bellringer activity for your writing class. Just print out some of these cool sheets and let your students get creative as they write thank-you notes to helpful heroes or finish little cartoon comics!

Learn More: Jarrett Lerner

13. Paint Chip Poetry

Nothing says creative writing quite like figurative language! Grab some of these free paint swatches from your local home improvement store and have your students create metaphors about their chosen color! We love this low-prep activity as once your kids have finished their poems, they’re a ready-made multi-colored display that’ll brighten the walls of your classroom!

Learn More: Fabulous In Fifth

14. Story Storm Activities

Once again, these Jarrett Lerner activities do not disappoint! Your students will have a blast pretending they are the principal for a day and they’ll get to create their very own rules for the school. Not only will this be an engaging writing exercise that we’re sure they’ll love getting creative with, but it also challenges children to think about why rules in school are important.

Learn More: Tara Lazar

15. Story Bag

Story bags are a fantastic way to destroy any kind of writer’s block! Grab an assortment of random objects from your home or classroom and pop them into the story bag. Next, gather your students around and pull out all the objects in the bag. Can they then write a story connecting all the items? Be sure to leave time to let them share their stories at the end of the lesson!

Learn More: Life Hack

16. Change the Ending

An easy way to ease your kiddos into the writing process is by having them rewrite part of a story. Grab their favorite read-aloud, and challenge them to come up with a new ending! They’ll need to finish the story in a way that makes sense, but aside from that, they can be as creative as they like! Your reluctant readers will like this one as much of the work on setting and characters has already been done!

Learn More: Make Beliefs Comix

17. Plot Twist Writing Prompts

BUT WAIT – there’s a twist…This fun writing practice is perfect for older middle or high school but could also be simplified for younger students. Write these twist prompts on notecards and have your kids draw one each before letting them go off and write a story around their chosen twist! They’ll be eager to share their finished work with classmates at the end. After all, who doesn’t love a good plot twist?

Learn More: Pinterest

18. Craft Box Craft

Every kid loves the book The Day the Crayons Quit for its creative narrative about this familiar box of coloring supplies! This extension activity rolls art and creative writing into one! Your students will have fun coming up with dialogue for each of the different crayons and you could even make it into a fun display for your classroom walls!

Learn More: Buggy And Buddy

19. Dialogue Pictures

Personalizing writing activities always makes it more engaging for kids! Print out a picture of yourself with a blank speech bubble, and model how to add in some dialogue. Then, let your kiddos practice speech bubbling with a photo of themselves, a pet, or a favorite celebrity, and have them come up with some interesting things for each of their subjects to say!

Learn More: SSS Teaching

20. Figurative Language Tasting

Your students will be creative writers in no time after practicing their figurative language with food tasting! Not only do tasty treats make this activity incredibly fun, but it also brings the writing process of metaphors and hyperbole to life. Just give each of your kids a few pieces of candy or snacks, and have them practice writing figures of speech relating to each one! They’ll have the words on the tip of their tongue- literally!

Learn More: It’s Lit Teaching

21. Explode the Moment

One of my favorite writing concepts as a teacher is ‘exploding the moment’. This method is perfect for showing your kiddies that even the smallest moment can be turned into an imaginative, descriptive story! Start by having them brainstorm some ideas and expand on tiny memories like losing a tooth, getting a pet, or making a winning goal in a soccer game!

Learn More: Raise The Bar Reading

22. Round-Robin Storytelling

Round-robin storytelling is the perfect collaborative creative writing activity! This one can be done verbally or in writing, and it challenges your class to build a story using a given set of words. They’ll have a fun and challenging time figuring out how to incorporate each piece into one cohesive story.

Learn More: Random Acts Of Kindness

23. Acrostic Poems

Acrostic poetry is one of the least intimidating creative writing exercises as there are no rules other than starting each line with the letter from a word. Challenge your kiddies to use each letter in their name to write lines of poetry about themselves, or they could choose to write about their favorite food or animal!

Learn More: Surfin’ Through Second

24. Sentence Sticks

This exercise requires minimal prep and can be used in so many different ways. All you’ll need are some craft sticks in which you will write sentences with blanks and word banks. Your young writers can then pull a stick and fill in the blanks to practice creative thinking! Task them with a different goal each time; can they make the sentence silly or sad for example?

Learn More: Liz’s Early Learning Spot

25. Conversation Prompts

These fun prompts require your kids to think creatively and answer a range of interesting questions. They’ll be excited to write stories about waking up with a mermaid tail or describe what is in a mystery package delivered to their doorstep! These creative prompts are perfect for bellringers or transitions throughout the school day!

Learn More: Twitter

26. Pretend Play Writing

Do you remember playing with fake money and fake food when you were younger? This idea takes it a step further by incorporating some writing practice! All you’ll have to do is print the templates for dollars, shopping lists, and recipes then let your little learners have fun with these play-pretend writing ideas!

Learn More: Prekinders

27. Question Cubes

Your class will be on a roll with these amazing question cubes! Whether the cubes are used for responding to a story, brainstorming the plot of a story, or practicing speech and listening, they are an easy, affordable tool for your little readers and writers! You can snag some foam dice at the dollar store and hot glue questions on each side to spark some creative writing ideas for your class.

Learn More: A Love 4 Teaching

28. Balderdash

Not only is Balderdash an addicting board game, but it can even be used in the classroom! Your little learners will have a blast as they create made-up, imaginative definitions for words, important people, and dates. Whoever guesses the real answer out of the mix wins the points!

Learn More: EB Academics

29. Two Sentence Horror Story

This creative writing exercise is best for older students and would be a great one to try out around Halloween! You’ll be challenging your learners to write a story that runs chills up their readers’ spines, but there’s a twist…the story can only be two sentences long! Your kiddos will love writing and sharing their writing to see who can come up with the spookiest short story!

30. Telephone Pictionary

Another game that your kids will be begging to play over and over again is telephone pictionary! The first player will write down a random phrase, and the next person must draw their interpretation of the phrase. The third player will write what they think the picture is and so on!

Learn More: Imagine Forest

31. Consequences

You need at least two players for this fun creative writing game. Each pair or group of kids will start by having one person write a random phrase and conceal it by folding the paper. Then, they pass it to the next student to fill in the blank using the prompt. Once all the blanks are filled in, let them unfold the paper and get ready to reveal some seriously silly stories!

32. Story Wands

Story wands are a fun way to have your kids respond to stories and study what makes something their favorite. Responding to what they’re reading is a super helpful exercise in preparing them for creative writing as it allows your students to connect to their favorite stories. By figuring out what elements make stories great, this is sure to help them in their own creative writing assignments!

Learn More: Little Lifelong Learners

33. The Best Part of Me

Probably my favorite creative writing activity, this one is infused with social-emotional learning and self-esteem building! Let your students get to choose their favorite physical characteristics about themselves; whether it be their eyes, hands, feet, etc. Then, they take a picture to attach to their written reasoning! Make sure to boost the creative element of this writing task by encouraging your learners to use a bunch of adjectives and some figurative language!

Learn More: Sarah Gardner Teaching

34. Me From A-Z

Challenge your kiddos to get creative by coming up with 26 different words to describe themselves! Me From A-Z gives your students the opportunity to explore who they are by coming up with words describing them in some way using each letter of the alphabet. Why not let them decorate their lists and turn them into a display celebrating the uniqueness of each of your class members?

35. How to Make Hot Chocolate

How-to writing is a great way to get the creative writing wheels turning in your kiddies’ brains! They’ll have a fun time coming up with their instructions and ways to explain how to make hot chocolate! Do they have a secret recipe that’ll make the best-ever hot cocoa!? Once they’ve written their instructions, be sure to try them out and do a taste-test of their recipes!

Learn More: Teacher Mama

36. Give Yourself a Hand

Hands up if you love this idea! For this creative writing activity, have your little ones trace their hand on a piece of paper and decorate it with accessories. Then, encourage them to write a list of all the different things they do with their hands all over their tracing! This is a great warm-up to get the creative gears turning.

Learn More: Write Now Troup

37. Word Picture Poem

A word picture poem is a fantastic way to challenge your kids to write descriptive poetry about a common object! Your little poets will learn to find beauty in ordinary things and strengthen their sensory language skills and their vocabulary. For some added fun, you can even task them with writing a short story about the item as well! The results are sure to be fun to read!

Learn More: Teaching With Terhune

38. Shape Poem