- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Criminal Justice

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Criminology research methods.

This section provides an overview of various research methods used in criminology and criminal justice. It covers a range of approaches from quantitative research methods such as crime classification systems, crime reports and statistics, citation and content analysis, crime mapping, and experimental criminology, to qualitative methods such as edge ethnography and fieldwork in criminology. Additionally, we explore two particular programs for monitoring drug abuse among arrestees, namely, the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM). Finally, the article highlights the importance of criminal justice program evaluation in shaping policy decisions. Overall, this overview demonstrates the significance of a multidisciplinary approach to criminology research, and the need to combine both qualitative and quantitative research methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of crime and its causes.

I. Introduction

• Brief overview of criminology research methods • Importance of understanding different research methods in criminology

II. Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM)

• Definition and purpose of DAWN and ADAM • Methodology and data collection process • Significance of DAWN and ADAM data in criminology research

III. Crime Classification Systems: NCVS, NIBRS, and UCR

• Overview and purpose of each system • Differences between the systems • Advantages and limitations of each system

IV. Crime Reports and Statistics

• Sources of crime data and statistics • Limitations of crime data and statistics • Use of crime data and statistics in criminology research

V. Citation and Content Analysis

• Definition and purpose of citation and content analysis • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of citation and content analysis in criminology research

VI. Crime Mapping

• Definition and purpose of crime mapping • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of crime mapping in criminology research

VII. Edge Ethnography

• Definition and purpose of edge ethnography • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of edge ethnography in criminology research

VIII. Experimental Criminology

• Definition and purpose of experimental criminology • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of experimental criminology in criminology research

IX. Fieldwork in Criminology

• Definition and purpose of fieldwork in criminology • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of fieldwork in criminology research

X. Criminal Justice Program Evaluation

• Definition and purpose of criminal justice program evaluation • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of criminal justice program evaluation in criminology research

XI. Quantitative Criminology

• Definition and purpose of quantitative criminology • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of quantitative criminology in criminology research

XII. Conclusion

• Importance of understanding different research methods in criminology • Future directions for criminology research methods

Criminology research methods are crucial for understanding the causes and patterns of crime, as well as developing effective strategies for prevention and intervention. There are various methods used in criminological research, each with its own strengths and limitations. Understanding the different research methods is essential for conducting high-quality research that can inform policies and practices aimed at reducing crime and promoting public safety. This overview provides an overview of some of the most commonly used criminology research methods, including the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM), crime classification systems such as the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), and Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR), crime reports and statistics, citation and content analysis, crime mapping, edge ethnography, experimental criminology, fieldwork in criminology, and quantitative criminology. The survey highlights the importance of understanding these methods and their applications in criminology research.

The Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) are two important research methods used in criminology to collect data on drug use and abuse among the population.

DAWN is a national public health surveillance system that tracks drug-related emergency department visits and deaths in the United States. The system collects data on drug-related medical emergencies and deaths from a variety of sources, including hospitals, medical examiners, and coroners. The purpose of DAWN is to provide information on drug use trends and the impact of drug use on public health and safety.

ADAM, on the other hand, is a research program that collects data on drug use and drug-related criminal activity among individuals who have been arrested and booked into jail. The program is designed to provide information on the prevalence of drug use and abuse among individuals involved in the criminal justice system.

Both DAWN and ADAM use similar methodology and data collection processes. Data is collected through interviews with individuals who have been involved in drug-related incidents, and through the analysis of drug-related data collected from medical and criminal justice records.

The significance of DAWN and ADAM data in criminology research is twofold. First, the data provides valuable information on drug use trends and patterns, which can inform the development of drug prevention and treatment programs. Second, the data can be used to understand the relationship between drug use and criminal behavior, and to inform criminal justice policies related to drug offenses.

Overall, the use of DAWN and ADAM in criminology research has contributed significantly to our understanding of drug use and abuse among the population, and has helped inform public health and criminal justice policies related to drug offenses.

The classification of crimes is an essential component of criminology research. The three main crime classification systems used in the United States are the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), and the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program.

The NCVS is a victimization survey that collects data on the frequency and nature of crimes that are not reported to law enforcement. The survey is conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics and includes a sample of households and individuals. The NCVS provides valuable insights into crime victimization patterns and trends.

The NIBRS, on the other hand, is a more detailed crime reporting system that provides a comprehensive view of crime incidents. It captures more data than the UCR, including information on the victim, offender, and the circumstances surrounding the crime. The NIBRS is being adopted by law enforcement agencies across the country and is expected to replace the UCR as the primary crime reporting system.

The UCR is the longest-running and most widely used crime reporting system in the United States. It collects data on seven index crimes, including murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft. The UCR provides an overview of crime trends and patterns at the national, state, and local levels.

Each system has its advantages and limitations. For example, the NCVS provides valuable information on crime victimization that is not captured by the UCR or NIBRS. The NIBRS provides more detailed information on crimes than the UCR but requires more resources to implement. The UCR is widely used and provides long-term trends but does not capture detailed information on each crime incident.

Understanding the differences and similarities between these classification systems is important for criminology research and policy development.

Crime reports and statistics are essential sources of data for criminology research. Law enforcement agencies, criminal justice systems, and government agencies collect and analyze crime data to develop policies and strategies to reduce crime rates. However, crime data and statistics have several limitations that researchers should consider when interpreting and using them in research.

One limitation of crime data and statistics is that they rely on the accuracy and completeness of reported crimes. Not all crimes are reported to law enforcement, and those that are reported may not be accurately recorded. Additionally, the police may have biases in their reporting practices, which can affect the accuracy of the data.

Another limitation of crime data and statistics is that they do not always provide a complete picture of crime. For example, crime data may not capture crimes that occur in private places or are committed by people who are not typically considered criminals, such as white-collar criminals.

Despite these limitations, crime data and statistics are still valuable sources of information for criminology research. They can help researchers identify patterns and trends in crime rates and understand the factors that contribute to criminal behavior. Crime data can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of criminal justice policies and programs.

Researchers should be cautious when using crime data and statistics in their research and acknowledge the limitations of these sources. They should also consider using multiple sources of data to triangulate their findings and develop a more comprehensive understanding of crime trends and patterns.

Citation and content analysis are research methods that are increasingly used in criminology. Citation analysis involves the systematic examination of citations in published works to determine patterns of authorship, influence, and intellectual relationships within a given field. Content analysis, on the other hand, involves the systematic examination of written or visual material to identify patterns or themes in the content.

In criminology research, citation and content analysis can be used to study a wide range of topics, including the evolution of criminological theories, the impact of specific research studies, and the representation of crime and justice issues in the media. These methods can also be used to identify gaps in the literature and to develop new research questions.

The methodology for citation analysis involves gathering data on citations from published works, including books, articles, and other sources. This data is then analyzed to determine patterns in the citations, such as which works are cited most frequently and by whom. Content analysis involves the systematic examination of written or visual material, such as news articles or social media posts, to identify patterns or themes in the content. This process may involve coding the content based on specific categories or themes, or using machine learning algorithms to identify patterns in the data.

Citation and content analysis are important tools in criminology research because they provide a way to examine the influence of research and ideas over time, as well as the representation of crime and justice issues in the media. However, these methods also have limitations, such as the potential for bias in the selection of sources or the coding of content.

Overall, citation and content analysis are valuable research methods in criminology that can provide insights into the evolution of criminological theories, the impact of specific research studies, and the representation of crime and justice issues in the media.

Crime mapping is a criminology research method that visualizes the spatial distribution of crime incidents. Crime mapping involves the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and other digital mapping tools to display crime data. The purpose of crime mapping is to provide researchers and law enforcement agencies with a better understanding of the spatial patterns of criminal activity in a given area.

Methodology and data collection process for crime mapping involve the collection of crime data and the use of GIS software to display the data in a visual format. Crime data can be collected from a variety of sources, such as police reports, victim surveys, and self-report surveys. Once the data is collected, it is geocoded, or assigned a geographic location, using a global positioning system (GPS) or address information.

The applications of crime mapping in criminology research are numerous. Crime mapping can be used to identify crime hotspots, or areas with a high concentration of criminal activity, which can help law enforcement agencies allocate resources more effectively. Crime mapping can also be used to identify crime patterns and trends over time, which can help researchers and law enforcement agencies develop strategies to prevent crime. Additionally, crime mapping can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of crime prevention and intervention strategies.

In conclusion, crime mapping is a valuable criminology research method that can provide researchers and law enforcement agencies with important insights into the spatial patterns of criminal activity. By using GIS and other digital mapping tools, crime mapping can help researchers and law enforcement agencies develop effective crime prevention and intervention strategies.

Edge ethnography is a criminology research method that focuses on studying the behaviors and social interactions of people on the fringes of society. It is often used to explore deviant or criminal behaviors in subcultures and marginalized groups. Edge ethnography involves immersive fieldwork, where the researcher actively participates in the activities of the group being studied to gain a deeper understanding of their values, beliefs, and practices.

The data collection process in edge ethnography involves participant observation, in-depth interviews, and document analysis. The researcher spends a considerable amount of time in the field to gain the trust and respect of the group members and to observe their behaviors and social interactions in a naturalistic setting. The researcher may also collect artifacts, such as photos and videos, to provide additional insights into the group’s activities.

Edge ethnography has many applications in criminology research. It can be used to explore the social and cultural contexts of criminal behaviors, as well as the experiences of marginalized groups in the criminal justice system. It can also be used to identify emerging trends and subcultures that may be associated with criminal activities.

However, edge ethnography also has limitations. It can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring the researcher to spend a considerable amount of time in the field. It may also raise ethical concerns, particularly if the researcher is studying criminal activities or subcultures that engage in illegal behaviors. Therefore, it is important for researchers to carefully consider the ethical implications of their research and to take steps to protect the privacy and safety of their subjects.

Experimental criminology refers to the use of scientific experimentation to test theories related to crime and deviance. The goal is to isolate the effects of specific factors on criminal behavior by manipulating one variable while holding others constant. Experimental criminology can involve lab experiments, field experiments, and quasi-experiments.

The methodology involves randomly assigning participants to different groups, manipulating the independent variable, and measuring the dependent variable. The data collected can be both quantitative and qualitative.

Experimental criminology has been used to test a variety of theories related to crime, including deterrence theory, social learning theory, and strain theory. It has also been used to evaluate the effectiveness of criminal justice interventions, such as drug treatment programs and community policing initiatives.

Despite the potential benefits of experimental criminology, there are limitations to its use. For example, it can be difficult to generalize the findings of a lab experiment to real-world situations, and ethical concerns may arise when manipulating variables related to criminal behavior. However, experimental criminology remains a valuable tool in the criminology research arsenal.

Fieldwork is an integral part of criminology research that involves researchers immersing themselves in the settings they are studying to gather firsthand information about the social and cultural dynamics of the phenomenon being studied. Fieldwork in criminology can be conducted through various methods such as participant observation, ethnography, case studies, and interviews.

The purpose of fieldwork in criminology is to gain a deeper understanding of the social and cultural factors that contribute to criminal behavior, victimization, and the criminal justice system. Fieldwork also provides insights into the lived experiences of those involved in the criminal justice system and how they perceive and experience law enforcement, punishment, and rehabilitation.

The methodology and data collection process in fieldwork in criminology involve a range of activities, including developing research questions, selecting research sites, building relationships with research participants, conducting observations and interviews, collecting data, and analyzing data. Researchers may also use various tools such as field notes, audio and video recordings, photographs, and maps to document their observations and experiences.

Fieldwork in criminology has various applications, including exploring the social and cultural dynamics of crime and criminal justice, evaluating criminal justice programs and policies, and understanding the experiences of victims, offenders, and criminal justice professionals. Fieldwork is particularly useful in gaining insights into the perspectives and experiences of marginalized and vulnerable populations, such as those living in poverty, incarcerated individuals, and communities that experience high rates of crime.

Overall, fieldwork in criminology is a valuable research method that provides rich and detailed information about the social and cultural dynamics of crime, victimization, and the criminal justice system. It allows researchers to gain insights into the experiences and perspectives of those involved in the criminal justice system and provides opportunities to evaluate and improve criminal justice policies and programs.

Criminal justice program evaluation refers to the systematic assessment of programs and policies implemented within the criminal justice system to determine their effectiveness in achieving their intended goals. The evaluation process involves collecting and analyzing data to assess the program’s impact, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency. Program evaluation is an essential tool for policymakers and practitioners to make informed decisions about criminal justice policies and programs.

The methodology used in program evaluation varies depending on the program or policy being evaluated. However, the process typically involves identifying the program’s goals and objectives, determining the program’s theory of change, identifying the target population, developing measures to evaluate the program, collecting and analyzing data, and reporting the findings.

Criminal justice program evaluation can be used to assess a wide range of programs, including correctional programs, law enforcement initiatives, and community-based programs. Evaluation findings can be used to determine the effectiveness of the program in reducing recidivism, improving public safety, or achieving other goals.

In recent years, criminal justice program evaluation has gained increasing attention as policymakers and practitioners seek evidence-based solutions to address the challenges facing the criminal justice system. The use of program evaluation has been instrumental in identifying effective interventions and programs, as well as those that are ineffective or even counterproductive.

Overall, criminal justice program evaluation is a critical tool for improving the effectiveness of criminal justice policies and programs. By providing policymakers and practitioners with evidence-based information, program evaluation can help to ensure that resources are used efficiently and effectively to promote public safety and reduce crime.

Quantitative criminology is a research method that involves the use of statistical data and techniques to analyze and understand crime patterns and behavior. It focuses on measuring and analyzing crime trends and patterns, identifying risk factors, and evaluating the effectiveness of crime prevention and intervention programs.

Quantitative criminology involves the use of numerical data to understand crime and its correlates. The purpose of this research method is to test theories and hypotheses about the causes and consequences of crime, identify patterns and trends, and evaluate the effectiveness of criminal justice policies and programs.

Quantitative criminology uses a variety of research methods and data collection techniques, including surveys, experiments, observations, and secondary data analysis. Researchers use statistical analysis to identify patterns, trends, and relationships among variables, such as crime rates, demographic characteristics, and socioeconomic factors.

Quantitative criminology has been used to study a wide range of topics, including the relationship between crime and social inequality, the effectiveness of community policing programs, and the impact of incarceration on recidivism. It has also been used to develop and test theories of crime, such as social disorganization theory and strain theory.

Quantitative criminology has contributed significantly to our understanding of crime and criminal behavior. It has provided valuable insights into the causes and consequences of crime and helped to inform the development of effective crime prevention and intervention programs.

The study of criminology is a complex field that requires a variety of research methods to understand and analyze the causes and patterns of crime. This article has provided an overview of several important criminology research methods, including the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM), crime classification systems such as NCVS, NIBRS, and UCR, crime reports and statistics, citation and content analysis, crime mapping, edge ethnography, experimental criminology, fieldwork, and criminal justice program evaluation. Each research method has its unique strengths and limitations, making it important for criminologists to choose the appropriate method for their research question.

As the field of criminology continues to evolve, it is important for researchers to consider new and innovative research methods. Future directions in criminology research may include advances in technology, such as the use of big data analytics and machine learning algorithms, as well as an increased emphasis on interdisciplinary collaborations between criminologists and experts in fields such as psychology, sociology, and public health.

Overall, the study of criminology requires a diverse range of research methods to fully understand the complex nature of crime and its causes. By utilizing these methods and continuing to explore new avenues for research, criminologists can make important contributions to our understanding of crime and help inform policies and interventions aimed at reducing crime and promoting public safety.

References:

- Aebi, M. F., Tiago, M. M., & Burkhardt, C. (2018). The future of crime and crime control between tradition and innovation. Cham: Springer.

- Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (2013). Environmental criminology. In The Oxford handbook of criminology (pp. 387-408). Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, R. V. (2017). Situational crime prevention. In The Routledge handbook of critical criminology (pp. 124-136). Routledge.

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American sociological review, 44(4), 588-608.

- Cullen, F. T., & Jonson, C. L. (2017). Criminal justice research methods: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Dantzker, M. L., & Hunter, R. D. (2017). Research methods in criminal justice and criminology (10th ed.). Routledge.

- Eck, J. E. (2017). Problem-oriented policing. In The Routledge handbook of critical criminology (pp. 137-150). Routledge.

- Eck, J. E., & Weisburd, D. (2015). What is problem-oriented policing?. Crime and justice, 44(1), 1-54.

- Felson, M. (2017). Routine activity theory. In The Routledge handbook of critical criminology (pp. 79-92). Routledge.

- Fox, J. A. (2015). Trends in drug use and related criminal behavior. In Drugs and crime (pp. 19-47). Springer.

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press.

- Hagan, F. E., & Foster, H. (2017). Crime and inequality. In The Routledge handbook of critical criminology (pp. 47-62). Routledge.

- Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2009). Crime, policing and social order: On the expressive nature of public confidence in policing. British Journal of Sociology, 60(3), 493-521.

- Kelling, G. L., & Coles, C. M. (1996). Fixing broken windows: Restoring order and reducing crime in our communities. Simon and Schuster.

- Maguire, M., & Snider, L. (2017). Understanding criminal justice. Routledge.

- Mazerolle, L., & Rombouts, S. (2017). Experimental criminology. In The Routledge handbook of critical criminology (pp. 93-107). Routledge.

- Mazerolle, L., & Roehl, J. (2008). Policing, crime, and hot spots policing. Crime and justice, 37(1), 315-363.

- National Institute of Justice. (n.d.). Crime mapping research center. Retrieved from https://www.nij.gov/topics/technology/maps/Pages/welcome.aspx

- Reisig, M. D., Holtfreter, K., & Morash, M. (Eds.). (2016). The Oxford handbook of criminological theory. Oxford University Press.

- Weisburd, D., Hinkle, J. C., & Eck, J. E. (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Research Methods for Criminal Justice Students

(3 reviews)

Monica Williams, Weber State University

Copyright Year: 2022

Publisher: Monica Williams

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Kelly Arney, Dean of Behavioral Sciences, Associate Professor, Grace College on 12/15/23

This textbook covers topics needed for criminal justice students to understand as they are going to be doing continual research in their field. Most of the examples cover criminal justice-specific real work examples with an emphasis on law... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This textbook covers topics needed for criminal justice students to understand as they are going to be doing continual research in their field. Most of the examples cover criminal justice-specific real work examples with an emphasis on law enforcement. Interestingly, this could be utilized for a larger behavioral science class as it encompasses the foundations of research that can be applied to most degrees in behavioral sciences. It places a large emphasis on the scientific method, how to design research, and data collection. It differs from other textbooks by not exploring the specifics of experimental designs, nonexperimental designs, quasi-experimental strategies, and factorial designs. The integration of real-world examples throughout each chapter will likely help students to grow in their willingness to engage in research that is necessary to the profession. Emphasis is placed on finding, understanding, and utilizing research.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The content was accurate and error-free. No biases material or examples were identified.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The content was relevant and recent. The foundational terminology spans the last two decades. This book was originally based on Bhattachergee's 2012 Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practice and Blackstone's 2012 Principles of Sociological Inquiry: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. This material was built on and this textbook is accurate with more recent examples. It has devoted a chapter to ethics in research which I found particularly relevant. It not only covers ethical standards such as the Belmont Report but also dives deep into ethics surrounding the specifics of those requirements. It has a section for research on humans, the Stanford Prison Experiment, Institutional Review Boards, informed consent, vulnerable populations, and the professional code of ethics. This textbook explores these areas in depth. Compared to other textbooks, this has devoted a substantial area to these topics that seem especially relevant recently and particularly important to emphasize for the criminal justice student.

Clarity rating: 5

This textbook seems to make research a little easier. The author has bolded the terminology words for students and created a nice and simple way of organizing the areas of study. The author has multiple categories inside each chapter that give meaning to the section. It is clear what each chapter is about, then each section inside that chapter. Research Methods can be a world of confusing terminology, but this author has simplified this and taken it to a level that students can easily follow. The Key Terms and Discussion Questions at the end of each chapter are also a nice guide for students to clarify what they read in each chapter.

Consistency rating: 4

Consistency is a difficult task in research methods because terms are interchangeable. Some of the terminology was inconsistent, but it described the same things and did not seem confusing. This textbook was the easiest to read when compared to the other textbooks on Research Methods. The sentences were simple and to the point. The book was not overrun with examples or mathematical equations that tend to confuse students. The instructor of the class may need to work to create the standard terminology they want to be used in class. This textbook explores the different terminology, so that can be a learning experience for students in and of itself. People use different terms in real life. It is an easy read as far as research goes. The clarity in the sentences and larger categories is apparent.

Modularity rating: 5

This is one of the largest strengths of this textbook. The text is easy to follow. The author did an excellent job of dividing the chapters into categories that divide the content into smaller readable sections. This makes smaller assignments much easier to assign to instructors. The sections have nice bolded titles and clear spacing between them with bolded words inside the sections. This makes pulling out specific areas and the relevant terminology much easier than in a traditional textbook. It is clear the author put time into organizing this textbook in a student-friendly way.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The topics are organized well. The chapters flow in a way that seems relevant to how it should be taught in the classroom. It is logical in that flow. The chapters are encompassed into larger sections: Think like a researcher, Research design, Qualitative data collection and analysis techniques, A qualitative and quantitative data collection technique, and finally Quantitative data collection and analysis techiniques. Inside each of these larger 5 sections are the chapters that expand on that idea. It is wellorganized.

Interface rating: 5

The digital pdf and the online versions of the textbook did not have any navigational problems. This textbook has some illustrations that worked well. No issues were noted with the interface.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The writing in this textbook was straightforward and clear. I did not find any typos or grammatical errors. This was an easy-to-read textbook.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

This textbook was culturally inclusive. I did not find any of the materials in this book to be insensitive or offensive. The examples in this textbook were general examples and did not associate with a cultural component. The only area I think that encompassed this was the vulnerable population section. That was very generalized and mostly suggested students consider who would fall into the vulnerable population category given what they want to research. The chapter on Research Questions (CH 4) did dive into the idea that students are social scientists and use their bias for their research projects. This was more about observing the world around them and then asking questions. It did not dive into cultural sensitivity any further.

I would recommend this book for research in behavioral science college-level classes. This book can be applied to students well beyond the criminal justice major. Many of the examples can be used for psychology, sociology, law, political science, and social work students. Don't let the criminal justice part of the title limit you. This is an easy-to-read and well-organized research textbook with helpful review guides included at the end of each chapter.

Reviewed by Mari Sakiyama, Associate Professor, Western Oregon University on 12/14/23

Each chapter of the textbook included the objectives, summary, key terms, and a few discussion questions. The key terms used in the book were in bold and were easy to identify. The chapters covered in the textbook are appropriate, and they are... read more

Each chapter of the textbook included the objectives, summary, key terms, and a few discussion questions. The key terms used in the book were in bold and were easy to identify. The chapters covered in the textbook are appropriate, and they are grouped in sections. Given that the provided examples throughout the textbook are CJ related, the major specific students can relate themselves to the course materials and it is easier for them to apply their conceptual CJ research ideas to research questions or a proposal. Glossary with definitions at the end of the book was not listed.

Content Accuracy rating: 2

I thought the content was accurate, and the author put the book together in an error-free manner. However, I thought that the textbook was slightly qualitative research heavy as opposed to quantitative research. Also, in the sampling section, I probably would not label non-probability and probability sampling for inductive qualitative and deductive quantitative research, respectively.

Given that research methods is generally required at all 4-year CJ programs and the majority of the concept of the course does not get outdated, the textbook definitely meets both relevancy and longevity.

Despite research methods tend to be full of jargon and technical terminologies, the material was written and introduced in a very reader-friendly and lucid manner. Perhaps, this book might had been the easiest read amongst all the research methods books I have read.

Both terminology and framework were internally consistent throughout the textbook. Although research methods consist with many interchangeable terms that describe the same thing, the author did a great job maintaining its consistency. In addition, the format for each chapter was also consistent and was easy to follow.

Modularity rating: 4

The textbook contains 15 chapters and are grouped in 5 different sections. Each chapter or even within those chapters can be divisible into smaller segment to fit instructors’ existing course structure. However, as mentioned earlier, the textbook was more qualitative research oriented and I thought some of the sections could be combined (i.e., III & IV). In addition, I think sampling could be its own section. Nonetheless, with the divisibility as well as the author’s permission to reuse and modify with attribution, the issues could be easily resolved.

The textbook was well-organized and -structured. I generally do not cover different designs until after midterm but I personally like the flow of this textbook.

Interface rating: 3

The textbook did not have any navigation problems, since each chapter’s organization is consistent. Some of the tables that provided key summaries of strategies/designs or its comparison of strengths/weakness are very helpful to learners. The author did a great job creating charts and diagrams, bur there could be more of them. Also, the number of illustrations/photos were limited but that could be easily adjusted when incorporating the textbook.

The style of writing was appropriate and straightforward. I did not find any typos or grammatical errors. I believe that the textbook would be an easy read compared to other publishers’ research methods textbooks.

I did not find any of the materials in the textbook that were culturally insensitive nor offensive. Examples throughout the textbook were general examples that did not necessarily associate with cultural component.

While there have been OER research methods books for Sociology and Psychology, I think this is the first OER book for CJ research methods, at least that I know of (and kudos to the author)! It would be an excellent material for undergraduate CJ students. I definitely consider using this book for my class.

Reviewed by Youngki Woo, Assistant professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 12/16/22

The textbook covers most areas of research methods in the field of criminology and criminal justice. Like other textbooks, each chapter identifies the learning objectives and showed it in the beginning. At the end of each chapter, there are... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The textbook covers most areas of research methods in the field of criminology and criminal justice. Like other textbooks, each chapter identifies the learning objectives and showed it in the beginning. At the end of each chapter, there are several discussion questions for students. Each chapter is comfortable to follow and addresses all the learning objectives to provide a straightforward response to the discussion questions. In addition, each chapter covers ideas of the subject appropriately and provides an effective index, key terms, and glossary.

Content is accurate and it is easy to read and follow.

Each chapter addresses fundamental concepts and techniques that students should know about research methods in social sciences. The book is published in 2022, indicating that content is up-to-date.

The text is simple and well-written, and content is informative and straight-forward.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. The author did a great job in providing summary at the end of the chapter that tied along with the learning objectives that are provided at the beginning of the chapter.

There are five parts in the textbook and each part is easily divisible into smaller reading sections that can be assigned at different points within the course (please see the Table of Contents). Personally, chapter 4 and 5 covers relevant information, but they could have gone more in depth when describing the different techniques along with a variety of research examples.

The topics in the text are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The logical organization carries students through the sequence of the research process. As an instructor, I like the organization that is flexible and helps students better understand the fundamental research skills in criminal justice.

Personally, I would suggest the author to add more photos/images/charts to give examples of what each objective talk about on each chapter. It would help the reader to figure out some methodological techniques with a visual representation. Nonetheless, the text is free of significant interface issues, including navigation problems and any other display features that may distract or confuse the reader.

There are no typos or technical/grammatical errors that I am aware of in the textbook.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The text is not culturally insensitive and offensive as the text discuss mainly about research methods. Some examples in the textbooks are children and family.

Overall, this book contains information that could help students understand the knowledge about methodological terms and skills. This book would be suitable for undergraduate methods courses in most social sciences.

Table of Contents

- 1. Scientific Research

- 2. Paradigms, Theories, and Research

- 3. Ethics in Research

- 4. Research questions

- 5. Research approaches and goals

- 6. Research methodologies

- 7. Measurement

- 8. Sampling

- 9. Focus groups

- 10. Field research

- 11. Qualitative data analysis

- 12. Interviews

- 13. Surveys

- 14. Experiments

- 15. Quantitative data analysis

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This book is based on two open-access textbooks: Bhattacherjee’s (2012) Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices and Blackstone’s (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. I first used Bhattacherjee’s book in a graduate-level criminal justice research methods course. I chose the book because it was an open educational resource that covered the major topics of my course. While I found the book adequate for my purposes, the business school perspective did not always fit with my criminal justice focus. I decided to rewrite the textbook for undergraduate and graduate students in my criminal justice research methods courses. As I researched other open- educational resources for teaching social science research methods, I found Blackstone’s book, which covered more of the social science and qualitative methods perspectives that I wanted to incorporate into my book.

As a result, this open-access textbook includes some content from both previous works along with my own additions based on my extensive experience and expertise in conducting qualitative and quantitative research in social science settings and in mentoring students through the research process. My Ph.D. is in Sociology, and I currently teach undergraduates and graduate students in a criminal justice program at Weber State University. Throughout my career, I have conducted and published the results of research projects using a variety of methods, including surveys, case studies, in-depth interviews, participant observation, content analysis, and secondary analysis of quantitative data. I have also mentored undergraduates in conducting community-based research projects using many of these same methods with the addition of focus groups and program evaluations.

About the Contributors

Monica Williams, Ph.D ., Associate Professor, Weber State University

Contribute to this Page

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Ronet D. Bachman - University of Delaware, USA

- Russell K. Schutt - University of Massachusetts Boston, USA

- Description

- Assignable Video with Assessment Assignable video (available in SAGE Vantage ) is tied to learning objectives and curated exclusively for this text to bring concepts to life. Watch a sample video now .

- LMS Cartridge: Import this title's instructor resources into your school's learning management system (LMS) and save time. Don't use an LMS? You can still access all of the same online resources for this title via the password-protected Instructor Resource Site. Select the Resources tab on this page to learn more.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

- Editable chapter-specific PowerPoint® slides

- Lecture notes

- Instructor's Manual

- All tables and figures from the textbook

The digital content on the website for instructors is very helpful. The book is well written and organized with a nice blend of examples and illustrations. I'll most likely adopt this one should I teach another research methods course.

We were notified by the bookstore that copies of the 7th edition would no longer be available for our students. We also acknowledge new content and updated examples in the latest version.

- The new edition is available in SAGE Vantage , an intuitive learning platform that integrates quality SAGE textbook content with assignable multimedia activities and auto-graded assessments to drive student engagement and ensure accountability. Unparalleled in its ease of use and built for dynamic teaching and learning, Vantage offers customizable LMS integration and best-in-class support. Select the Vantage tab on this page to learn more.

- An entirely new Chapter 2 describes the process of both inductive and deductive research using recent examples related to police behavior including body worn cameras.

- New sections throughout reflect new developments in research methods such as revised federal guidance on ethics, and new methods that have come to the fore such as visual criminology and photo voice.

- Expanded chapters with new sections highlight the importance of making sure samples, measurements, and methods are inclusive and sensitive to the diverse nature of our society .

- New coverage on Writing a Journal Article and new developments that impact research, such as the revision to the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects.

- The authors have included contemporary examples throughout , such as the increase in the use of social media, the continuing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, mass participation in social movements including Black Lives Matter, increasing hate crimes across the globe, and increasing incidents of mass shootings in the U.S.

- Each chapter includes an in-depth substantive research example from the real world , highlighting researchers' decision-making processes in their own words.

- Updated "Careers in Research" feature highlights a researcher who has used the methods described in that chapter, demonstrating the use of research methods within a variety of professions.

- New empirical datasets are now included in the Student Study Site, and each chapter contains new IBM® SPSS® Statistics or Excel exercises that correspond to the chapter material.

- Effective study aids include end-of-chapter summaries and key terms that are bolded on first use, listed at the end of each chapter, and defined in a glossary.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1. Science, Society, and Research

Chapter 2. The Process and Problems of Research

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

Shipped Options:

BUNDLE: Bachman, The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice 8e (Vantage Shipped Access Card) + Bachman, The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice 8e (Loose-leaf)

Related Products

Advertisement

Mixed Methods Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice: a Systematic Review

- Published: 07 January 2021

- Volume 47 , pages 526–546, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Nicole Wilkes 1 ,

- Valerie R. Anderson 1 ,

- Cheryl Laura Johnson 2 &

- Lillian Mae Bedell 1

3393 Accesses

8 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

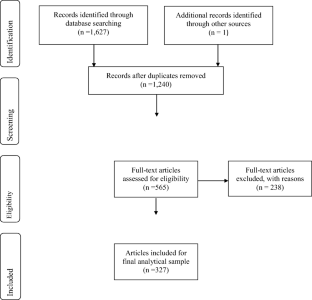

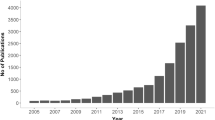

The field of criminology and criminal justice encompass broad and complex multidisciplinary topics. Most of the research that falls under these areas uses either quantitative or qualitative methodologies, with historically limited use of mixed methods designs. Research utilizing mixed methods has increased within the social sciences in recent years, including a steadily growing body of mixed method research in criminal justice and criminology. The goal of this study was to examine how mixed method designs are being employed within research related to criminal justice and criminology. Our systematic review located 327 mixed method articles published between 2001 and 2017. Findings indicated most criminology and criminal justice research is being conducted within the specialty area of victimology. This study provides an overview of mixed methods research in criminology and criminal justice and also illustrates that most publications are not including methodological concepts specific to mixed methods research (e.g., integration). Along with our systematic review, we offer a series of recommendations to move mixed methods research forward in criminology and criminal justice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The disaster of misinformation: a review of research in social media

The Social Learning Theory of Crime and Deviance

Labeling theory.

Aarons, G. A., Fettes, D. L., Sommerfeld, D. H., & Palinkas, L. A. (2012). Mixed methods for implementation research: Application to evidence-based practice implementation and staff turnover in community-based organizations providing child welfare services. Child Maltreatment, 17 (1), 67–79.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city . New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Google Scholar

Anderson, V. R. (2015). Introduction to mixed methods approaches. In L. A. Jason & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (pp. 233–241). New York: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bazeley, P. (2018). Integrating analyses in mixed methods research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Brent, J. J., & Kraska, P. B. (2010). Moving beyond our methodological default: A case for mixed methods. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21 (4), 412–430.

Bryman, A. (1988). Quantity and quality in social research . London: Routledge.

Buckler, K. (2008). The quantitative/qualitative divide revisited: A study of published research, doctoral program curricula, and journal editor perceptions. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 19 (3), 383–403.

Burrell, N. A., & Gross, C. (2018). Quantitative research, purpose of. In M. Allen (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods (pp. 1378–1380). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56 (2), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046016 .

Campbell, R., Fehler-Cabral, G., Bybee, D., & Shaw, J. (2017). Forgotten evidence: A mixed methods study of why sexual assault kits (SAKs) are not submitted for DNA forensic testing. Law and Human Behavior, 41 (5), 454–467.

Campbell, R., Goodman-Williams, R., Feeney, H., & Fehler-Cabral, G. (2020). Assessing triangulation across methodologies, methods, and stakeholder groups: The joys, woes, and politics of interpreting convergent and divergent data. American Journal of Evaluation, 41 (1), 125–144.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 1 , 37–46.

Copes, H., Beaton, B., Ayeni, D., Dabney, D., & Tewksbury, R. (2020). A content analysis of qualitative research published in top criminology and criminal justice journals from 2010 to 2019. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45 , 1060–1079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09540-6 .

Copes, H., Brown, A., & Tewksbury, R. (2011). A content analysis of ethnographic research published in top criminology and criminal justice journals from 2000 to 2009. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 22 (3), 341–359.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., Klassen, A. C., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences . Washington, DC: National Institute for Health https://www.obssr.od.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Best-Practices-for-Mixed-Methods-Research-in-the-Health-Sciences-2018-01-25.pdf .

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Crow, M. S., & Smykla, J. O. (2013). A mixed methods analysis of methodological orientation in national and regional criminology and criminal justice journals. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24 (4), 536–555.

Culbert, G. J., Bazazi, A. R., Waluyo, A., Murni, A., Muchransyah, A. P., Iriyanti, M., Finnahari, Polonsky, M., Levy, J., & Altice, F. L. (2016). The influence of medication attitudes on utilization of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Indonesian prisons. AIDS and Behavior, 20 (5), 1026–1038.

Curry, L., & Nunez-Smith, M. (2015). Mixed methods in health sciences research: A practical primer . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. (1978). Sociological methods . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Eadie, D., MacAskill, S., McKell, J., & Baybutt, M. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to a criminal justice tobacco control coordinator: An innovative approach to supporting smoking cessation among offenders. Addiction, 107 (2), 26–38.

European Commission JRC. (2007). Quantitative versus qualitative methods. Retrieved from http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/4_methodology/meth_quanti-quali.htm .

Fàbregues, S., & Molina-Azorín, J. F. (2017). Addressing quality in mixed methods research: A review and recommendations for a future agenda. Quality and Quantity, 51 , 2847–2863.

Greene, J. C., & Caracelli, V. J. (Eds.). (1997). Advances in mixed-method evaluation: The challenges and benefits of integrating diverse paradigms: New directions for evaluation, 74 . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11 (3), 255–274.

Hart, L. C., Smith, S. Z., Swars, S. L., & Smith, M. E. (2009). An examination of research methods in mathematics education (1995–2005). Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 3 (1), 26–41.

Heap, V., & Waters, J. (2019). Mixed methods in criminology . Routledge.

Hesse-Biber, S., & Johnson, R. B. (2013). Coming at things differently: Future directions of possible engagement with mixed methods research [Editorial]. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 7 (2), 103–109.

Hovey, A., Rye, B. J., & Stalker, C. A. (2013). Factors influencing perceptions of abuse victims: Do therapists’ beliefs about sexual offending affect counseling practices with women? Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 22 , 572–592.

Hovey, A., Stalker, C. A., & Rye, B. J. (2014). Perpetrators of sexual abuse and considerations for treatment. Asking women survivors about thoughts or actions involving sex with children: An issue requiring therapist sensitivity. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23 , 442–461.

Howe, K. R. (2016). Against the quantitative-qualitative incompatibility thesis or dogmas die hard. Educational Researcher, 17 (8), 10–16.

Howell Smith, M. C., & Shanahan Bazis, P. (2020). Conducting mixed methods research systematic methodological reviews: A review of practice and recommendations. Journal of Mixed Methods Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689820967626 .

Islam, F., & Oremus, M. (2014). Mixed methods immigrant mental health research in Canada: A systematic review. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 16 , 1284–1289.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33 (7), 14–26.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (2), 112–133.

Kleck, G., Tark, J., & Bellows, J. J. (2006). What methods are most frequently used in research in criminology and criminal justice? Journal of Criminal Justice, 34 , 147–152.

Maruna, S. (2009). Mixed method research in criminology: Why not go both ways? In A. R. Piquero & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of Quantitative Criminology (pp. 123–140). New York: Springer.

Miller, H. V., Miller, J. M., & Barnes, J. C. (2016). Reentry programming for opioid and opiate involved female offenders: Findings from a mixed methods evaluation. Journal of Criminal Justice, 46 , 129–136.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6 (7), 1–6.

Molina-Azorin, J. F., & Fetters, M. D. (2016). Mixed methods research prevalence studies: Field-specific studies on the state of the art of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10 (2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/155868981663670 .

Plano Clark, V. L., & Ivankova, N. V. (2016). Mixed methods research: A guide to the field . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shaw, C. R. (1966). The jack-roller: A delinquent boy’s own story . University of Chicago Press.

Sullivan, C. J., & Maxfield, M. G. (2003). Examining paradigmatic development in criminology and criminal justice: A content analysis of research methods syllabi in doctoral programs. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 14 (2), 269–285.

Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. W. (2007). The new era of mixed methods [editorial]. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (3), 207–211.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Testa, M., Livingston, J. A., & Vanzile-Tamsen, C. (2011). Advancing the study of violence against women using mixed methods: Integrating qualitative methods into a quantitative research program. Violence Against Women, 17 (2), 236–250.

Tewksbury, R., DeMichele, M. T., & Miller, J. M. (2005). Methodological orientations of articles appearing in criminal justice’s top journals: Who publishes what and where. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 16 (2), 265–279.

Tewksbury, R., Dabney, D. A., & Copes, H. (2010). The prominence of qualitative research in criminology and criminal justice scholarship. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21 , 391–411.

Wright, R. T., & Decker, S. H. (1997). Armed robbers in action: Stickups and street culture . Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate Christina Poole’s assistance with coding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Teachers-Dyer Complex, School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati, 2610 McMicken Circle, Cincinnati, OH, 45221, USA

Nicole Wilkes, Valerie R. Anderson & Lillian Mae Bedell

Department of Sociology, Hartwick College, P.O. Box 4022, Oneonta, NY, 13820, USA

Cheryl Laura Johnson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicole Wilkes .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 38 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wilkes, N., Anderson, V.R., Johnson, C.L. et al. Mixed Methods Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice: a Systematic Review. Am J Crim Just 47 , 526–546 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09593-7

Download citation

Received : 17 August 2020

Accepted : 13 November 2020

Published : 07 January 2021

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09593-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mixed methods

- Methodology

- Criminal justice

- Criminology

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- My library record

- ANU Library

- new production templates

Criminology

Research methodologies.

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

- Books and e-books

- Journals and e-journals

- Audio-visual resources

- Sample ANU Theses

- Associations and Societies

- Domain names

- Open Educational Resources

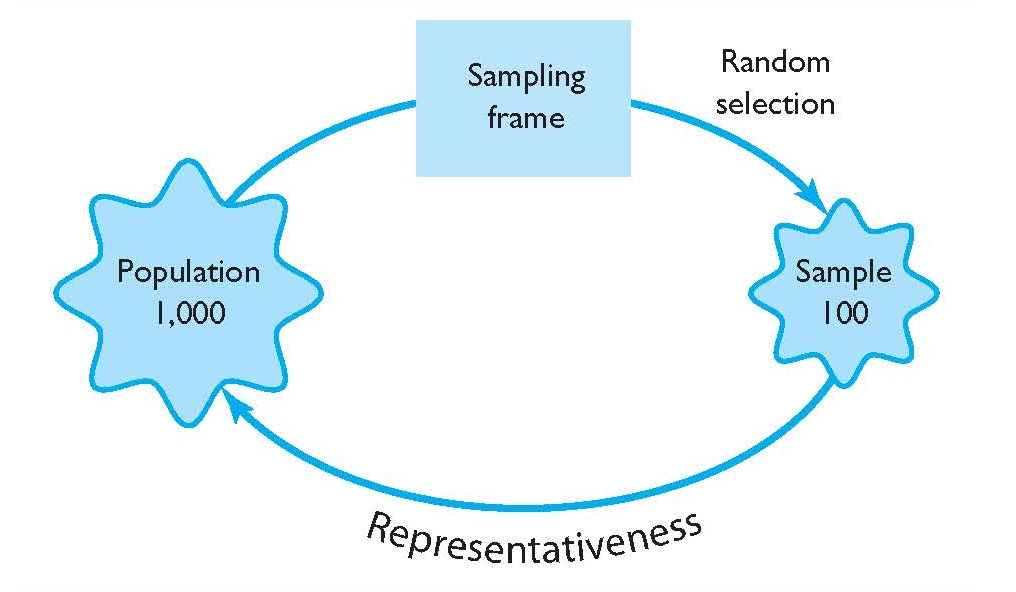

- Requesting resources

A research methodology describes the specific process used to collect and evaluate information and data. This may involve a variety of qualitative and quantative techniques such as surveys, interviews, experiments, measurement and statistics, and publication research. The texts below are a selection of titles that may help you to design your own research methodology.

- << Previous: Audio-visual resources

- Next: Statistics >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 4:17 PM

- URL: https://libguides.anu.edu.au/criminology

Responsible Officer: University Librarian / Page Contact: Library Systems & Web Coordinator

- Contact ANU

- Freedom of Information

+61 2 6125 5111 The Australian National University, Canberra CRICOS Provider : 00120C ABN : 52 234 063 906

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2014

Innovative data collection methods in criminological research: editorial introduction

- Jean-Louis van Gelder 1 &

- Stijn Van Daele 2

Crime Science volume 3 , Article number: 6 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

11 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Novel technologies, such as GPS, the Internet and virtual environments are not only rapidly becoming an increasingly influential part of our daily lives, they also have tremendous potential for improving our understanding of where, when and why crime occurs. In addition to these technologies, several innovative research methods, such as neuropsychological measurements and time-space budgets, have emerged in recent years. While often highly accessible and relevant for crime research, these technologies and methods are currently underutilized by criminologists who still tend to rely on traditional data-collection methods, such as systematic observation and surveys.

The contributions in this special issue of Crime Science explore the potential of several innovative research methods and novel technologies for crime research to acquaint criminologists with these methods so that they can apply them in their own research. Each contribution deals with a specific technology or method, gives an overview and reviews the relevant literature. In addition, each article provides useful suggestions about new ways in which the technology or method can be applied in future research. The technologies describe software and hardware that is widely available to the consumer (e.g. GPS technology) and that sometimes can even be used free of charge (e.g., Google Street View). We hope this special issue, which has its origins in a recent initiative of the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR) called CRIME Lab, and a collaborative workshop together with the Research consortium Crime, Criminology and Criminal Policy of Ghent University, will inspire researchers to start using innovative methods and novel technologies in their own research.

Issues and challenges facing crime researchers

Applied methods of scientific research depend on a variety of factors that play out at least in part beyond researcher control. One such factor regards the nature and availability of data, which largely determines the research questions that can be addressed: Data that cannot be collected cannot serve to answer a research question. Although this may seem like stating the obvious, it has had and continues to have far-reaching implications for criminological research. Because crime tends to be a covert activity and offenders have every interest in keeping it that way, crime in action can rarely be observed, let alone in such a way as to allow for systematic empirical study. Consequently, our knowledge of the actual offending process is still limited and relies in large part on indirect evidence. The same applies to offender motivations and the offending process; these cannot be measured directly in ways similar to how we can observe say the development of a chemical process or the workings of gravity. This has placed significant restrictions on the way crime research has been performed over the years, and most likely has coloured our view of crime and criminality by directing our gaze towards certain more visible elements such as offender backgrounds, demographics and criminal careers.

Another factor operating outside of researcher control regards the fact that the success of scientific analyses hinges on the technical possibilities to perform them. Even if researchers have access to particular data, this does not guarantee that the technology to perform the analysis in the best possible way is available to them. The complexity of the social sciences and the interconnectivity of various social phenomena, together with the lack of a controlled environment or laboratory, require substantial computational power to test highly complicated models. For instance, the use of space-time budgets, social network analysis or agent-based modelling can be quite resource-intensive. Adding the complexity of social reality to the resulting datasets (e.g. background variables related to social structure, GIS to incorporate actual road networks, etc.) puts high pressure on the available computational power of regular contemporary desktop computers. Addressing these challenges has practical and financial consequences, which brings us to the third issue, which although more mundane in nature is by no means limited to the applied sciences: a researcher requires the financial and non-financial resources to be able to perform his research.

All three factors have a bearing on the contents and goals of the present special issue. More specifically, the methods that are discussed and explained in different articles in this special issue each address one or more of these factors and have, we believe, the potential to radically change the way we think about crime and go about doing crime research. The methods and technologies are available, feasible and affordable. They are, so to speak, there for the taking.

Notes on criminological research methods

The above factors have contributed to a general tendency within criminology to stick to particular research traditions, both in terms of method and analysis. Although these traditions are well-developed and have undergone substantial improvement over the decades, most changes in the way research is performed in the discipline have been of the ’more of the same‘ variety, and most involve gradual improvements, rather than embodying ‘scientific revolutions’ and ‘paradigm shifts’ that have radically changed how criminologists go about doing research and thinking about crime.

With respect to methodology, since the field's genesis in the early 20th century, research in criminology has largely spawned studies using similar methods. In a meta-analysis of articles that have appeared in seven leading criminology and criminal justice journals in 2001-2002, Kleck et al. ([ 2006 ]) demonstrate that survey research is still the dominant method of collecting information (45.1%), followed by the use of archival data (31.8%), and official statistics (25.6%). Other methods, such as interviews, ethnographies and systematic observation, each account for less than 10% (as methods are sometimes combined the percentages add up to more than 100%). Furthermore, the Kleck et al. meta-analysis shows that as far as data analysis is concerned, nearly three quarters (72.5%) of the articles published uses some type of multivariate statistics. As such, it appears that criminology has developed a research tradition that started to dominate the field, though not to everybody's enthusiasm. Berk ([ 2010 ]), for example, states that regression analysis, in its broad conception, has become so dominant that researchers give it more credit than they sometimes should and take some of its possibilities for granted. Whereas certain research traditions may have a strong added value, they run the risk of being used more out of habit than for being the most appropriate method to answer a particular research question. As innovation influences our daily lives and how we perform our daily activities, there is no reason why it should not influence our way of performing science as well.

Innovation and technology in daily life and their application in criminological research

Novel technologies, such as GPS, the Internet, and virtual environments are rapidly establishing themselves as ingrained elements of our daily lives. Think, for example, of smart phones. While unknown to most of us as recently as ten years ago, today few people would leave their home without carrying one with them. Through their ability to, for example, transmit visual and written communication, use social media, locate ourselves and others through apps and GPS, smart phone technology has radically changed the way we go about our daily routines. The research potential of smart phone technology for improving our understanding of social phenomena is enormous and includes a better understanding of where, when and why crime occurs through automated data collection, interactive tests and surveys (Miller [ 2012 ]). Yet, so far surprisingly few crime researchers have picked up on the possibilities this technology has to offer.

A similar point can be made with respect to the Internet. While most researchers have made the transition from paper-and-pencil questionnaires to online surveys and online research panels may have become the norm for collecting community sample data, much of the potential of the Internet for crime research remains untapped. Think, for example, of the possibility of using Google Maps and Google Street View for studying spatial aspects of crime and the ease with which we can virtually travel down most of the roads and streets to examine street corners, buildings and neighbourhoods. The launch of Google Street View in Belgium stirred up controversy because it was perceived by police officers as a catalogue for burglars and was expected to lead to an increase in the number of burglaries. While it is not clear whether this has actually happened, crime studies reporting these tools in their method sections are few and far between.

In addition to novel technologies, several innovative research methods, such as social network analysis, time-space budgets, and neuropsychological measures that can tap into people's physiological and mental state, have emerged in recent years and have become common elements of the tool-set used in some of criminology's sister disciplines, such as sociology, psychology and neuroscience. Again, while often highly accessible and relevant for crime research, these methods are currently underutilized by crime researchers. The promising and emerging field of neurocriminology is an important exception in this respect (see e.g., Glenn & Raine [ 2014 ]).

To revert back to the three issues that have restricted the gaze of criminology mentioned at the outset of this article: accessibility of data, type of data analysis, and availability of resources, the new methods and technologies seem to check all the boxes. Much more data have become accessible for analysis through novel technologies, new methods for data-analysis and data-collection have been developed, and most of it is available at the consumer level. In other words, this allows for collecting and examining data in ways that go far beyond what we are used to in crime research. For example, methods combining neurobiological measurements with virtual environments can tell us a lot about an individual's mental and physical states and how they go about making criminal decisions, which were until recently largely black boxes. Finally, novel technologies are often available on the consumer market, such as smart phones, tablets, and digital cameras, and require only very modest research budgets. In some cases, such as the automated analysis of footage made by security cameras, simulations, or the use of honeypots that lure cyber criminals into hacking them, they even allow for systematically examining crime in action.

Goals of this special issue of Crime Science

The principal aim of the present special issue is to acquaint crime researchers and criminology students with some of these technologies and methods and explain how they can be used in crime research. While widely diverging, what these technologies and methods have in common is their accessibility and potential for furthering our understanding of crime and criminal behavior. The idea, in other words, is to explore the potential of innovative research methods of data-collection and novel technologies for crime research and to acquaint readers with these methods so that they can apply them in their own research.

Each article deals with a specific technology or method and is set-up in such a way as to give readers an overview of the specific technology/method at hand, i.e., what it is about, why to use it and how to do so, and a discussion of relevant literature on the topic. Furthermore, when relevant, articles contain technical information regarding the tools that are currently available and how they can be obtained. Case studies also feature in each article, giving readers a clearer picture of what is at stake. Finally, we have encouraged all contributors to give their views on possible future developments with the specific technology or method they describe and to make a prediction regarding the direction their field could or should develop. We sincerely hope this will inspire readers to apply these methods in their own work.

While not intended as a manual, after reading an article, readers should not only have a clear view of what the method/technology entails but also of how to use it, possibly in combination with one or more of the references that are provided in the annotated bibliography provided at the end of each article. The contributions may also be useful for researchers already working with a specific method or students interested in research methodology.

Article overview

Hoeben, Bernasco and Pauwels discuss the space-time budget method. This method aims at retrospectively recording on an hour-by-hour basis the whereabouts and activities of respondents, including crime and victimization. The method offers a number of advantages over existing methods for data-collection on crime and victimization such as the possibility of studying situational causes of crime or victimization, possibly in combination with individual lifestyles, routine activities and similar theoretical concepts. Furthermore, the space-time budget method offers the possibility of collecting information on spatial location, which enables the study of a respondent's whereabouts, going beyond the traditional focus of ecological criminological studies on residential neighborhoods. Finally, the collected spatial information on the location of individuals can be combined with data on neighborhood characteristics from other sources, which enables the empirical testing of a variety of ecological criminological theories.

The contribution of Gerritsen focuses on the possibilities offered by agent-based modeling, a technique borrowed from the domain of Artificial Intelligence. Agent-based modeling (ABM) is a computational method that enables a researcher to create, analyse and experiment with models composed of agents that interact within a computational environment. Gerritsen explains how modeling and simulation techniques may help gain more insight into (informal) criminological theories without having to experiment with these phenomena in the real world. For example, to study the effect of bystander presence on norm violation, an ‘artificial neighborhood’ can be developed that is inhabited by 'virtual aggressors and victims’, and by manipulating the agents’ parameters different hypothetical scenarios may be explored. This enables criminologists to investigate complex processes in a relatively fast and cheap manner.