- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2017

New York Times Bestseller

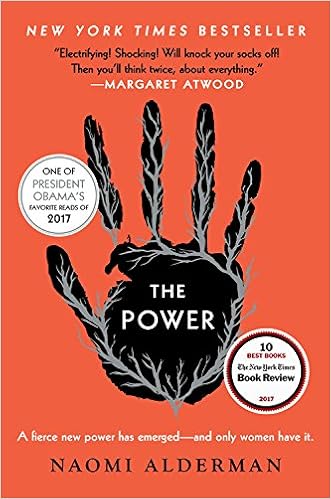

by Naomi Alderman ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 10, 2017

Very smart and very entertaining.

All over the world, teenage girls develop the ability to send an electric charge from the tips of their fingers.

It might be a little jolt, as thrilling as it is frightening. It might be powerful enough to leave lightning-bolt traceries on the skin of people the girls touch. It might be deadly. And, soon, the girls learn that they can awaken this new—or dormant?—ability in older women, too. Needless to say, there are those who are alarmed by this development. There are efforts to segregate and protect boys, laws to ensure that women who possess this ability are banned from positions of authority. Girls are accused of witchcraft. Women are murdered. But, ultimately, there’s no stopping these women and girls once they have the power to kill with a touch. Framed as a historical novel written in the far future—long after rule by women has been established as normal and, indeed, natural—this is an inventive, thought-provoking work of science fiction that has already won the Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction in Britain. Alderman ( The Liars’ Gospel , 2013, etc.) chronicles the early days of matriarchy’s rise through the experiences of four characters. Tunde is a young man studying to be a journalist who happens to capture one of the first recordings of a girl using the power; the video goes viral, and he devotes himself to capturing history in the making. After Margot’s daughter teaches her to use the power, Margot has to hide it if she wants to protect her political career. Allie takes refuge in a convent after running away from her latest foster home, and it’s here that she begins to understand how newly powerful young women might use—and transform—religious traditions. Roxy is the illegitimate daughter of a gangster; like Allie, she revels in strength after a lifetime of knowing the cost of weakness. Both the main story and the frame narrative ask interesting questions about gender, but this isn’t a dry philosophical exercise. It’s fast-paced, thrilling, and even funny.

Pub Date: Oct. 10, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-316-54761-1

Page Count: 400

Publisher: Little, Brown

Review Posted Online: July 16, 2017

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 1, 2017

DYSTOPIAN FICTION | SCIENCE FICTION | APOCALYPTIC & POST APOCALYPTIC SCI-FI | GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY

Share your opinion of this book

More by Naomi Alderman

BOOK REVIEW

by Naomi Alderman

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

Leslie Mann to Star in The Power Miniseries

SEEN & HEARD

by Max Brooks ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 16, 2020

A tasty, if not always tasteful, tale of supernatural mayhem that fans of King and Crichton alike will enjoy.

Are we not men? We are—well, ask Bigfoot, as Brooks does in this delightful yarn, following on his bestseller World War Z (2006).

A zombie apocalypse is one thing. A volcanic eruption is quite another, for, as the journalist who does a framing voice-over narration for Brooks’ latest puts it, when Mount Rainier popped its cork, “it was the psychological aspect, the hyperbole-fueled hysteria that had ended up killing the most people.” Maybe, but the sasquatches whom the volcano displaced contributed to the statistics, too, if only out of self-defense. Brooks places the epicenter of the Bigfoot war in a high-tech hideaway populated by the kind of people you might find in a Jurassic Park franchise: the schmo who doesn’t know how to do much of anything but tries anyway, the well-intentioned bleeding heart, the know-it-all intellectual who turns out to know the wrong things, the immigrant with a tough backstory and an instinct for survival. Indeed, the novel does double duty as a survival manual, packed full of good advice—for instance, try not to get wounded, for “injury turns you from a giver to a taker. Taking up our resources, our time to care for you.” Brooks presents a case for making room for Bigfoot in the world while peppering his narrative with timely social criticism about bad behavior on the human side of the conflict: The explosion of Rainier might have been better forecast had the president not slashed the budget of the U.S. Geological Survey, leading to “immediate suspension of the National Volcano Early Warning System,” and there’s always someone around looking to monetize the natural disaster and the sasquatch-y onslaught that follows. Brooks is a pro at building suspense even if it plays out in some rather spectacularly yucky episodes, one involving a short spear that takes its name from “the sucking sound of pulling it out of the dead man’s heart and lungs.” Grossness aside, it puts you right there on the scene.

Pub Date: June 16, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-9848-2678-7

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Del Rey/Ballantine

Review Posted Online: Feb. 9, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2020

GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SCIENCE FICTION

More by Max Brooks

by Max Brooks

THE DARK FOREST

From the remembrance of earth's past series , vol. 2.

by Cixin Liu ; translated by Joel Martinsen ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 11, 2015

Once again, a highly impressive must-read.

Second part of an alien-contact trilogy ( The Three-Body Problem , 2014) from China’s most celebrated science-fiction author.

In the previous book, the inhabitants of Trisolaris, a planet with three suns, discovered that their planet was doomed and that Earth offered a suitable refuge. So, determined to capture Earth and exterminate humanity, the Trisolarans embarked on a 400-year-long interstellar voyage and also sent sophons (enormously sophisticated computers constructed inside the curled-up dimensions of fundamental particles) to spy on humanity and impose an unbreakable block on scientific advance. On Earth, the Earth-Trisolaris Organization formed to help the invaders, despite knowing the inevitable outcome. Humanity’s lone advantage is that Trisolarans are incapable of lying or dissimulation and so cannot understand deceit or subterfuge. This time, with the Trisolarans a few years into their voyage, physicist Ye Wenjie (whose reminiscences drove much of the action in the last book) visits astronomer-turned-sociologist Luo Ji, urging him to develop her ideas on cosmic sociology. The Planetary Defense Council, meanwhile, in order to combat the powerful escapist movement (they want to build starships and flee so that at least some humans will survive), announces the Wallfacer Project. Four selected individuals will be accorded the power to command any resource in order to develop plans to defend Earth, while the details will remain hidden in the thoughts of each Wallfacer, where even the sophons can't reach. To combat this, the ETO creates Wallbreakers, dedicated to deducing and thwarting the plans of the Wallfacers. The chosen Wallfacers are soldier Frederick Tyler, diplomat Manuel Rey Diaz, neuroscientist Bill Hines, and—Luo Ji. Luo has no idea why he was chosen, but, nonetheless, the Trisolarans seem determined to kill him. The plot’s development centers on Liu’s dark and rather gloomy but highly persuasive philosophy, with dazzling ideas and an unsettling, nonlinear, almost nonnarrative structure that demands patience but offers huge rewards.

Pub Date: Aug. 11, 2015

ISBN: 978-0-7653-7708-1

Page Count: 480

Publisher: Tor

Review Posted Online: June 2, 2015

Kirkus Reviews Issue: June 15, 2015

GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | SCIENCE FICTION | GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION

More In The Series

by Cixin Liu ; translated by Ken Liu

More by Cixin Liu

by Cixin Liu ; translated by Various

by Cixin Liu ; translated by Joel Martinsen

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

before I read the middle

Review: The Power, Naomi Alderman

Since its release in 2016, Naomi Alderman’s The Power has been impossible to miss, receiving accolades from the New York Times and President Barack Obama, among many many others. The premise is that women — through a new organ called a skein, located at their collarbones — suddenly become more physically powerful than men, able to transmit strong jolts of electricity. Things go downhill pretty quickly.

I resisted The Power because I am tired of power and the things people do to keep it. 2016 was the year Alton Sterling was killed in my home state. 2016 was the year I woke up at three in the morning and learned that white America had elected Donald Trump to the presidency. 2016 was already a terrifying real-life master class in the ways power corrupts morality; it was not my opinion that I needed a fictional one, as well.

But time passed, and I got used to this new reality (which I’m perennially angry with myself for, which is stupid because that’s how humans are, but also what is wrong with me and how could anyone get used to this?), and my friend Renay said The Power was really good though flawed, and what can I say? I like a book with ambition. The Power has ambition. Naomi Alderman wasn’t just writing a story about gender — in fact, Renay argues (I think rightly!) that she wasn’t writing about gender at all — but about the downfall of a society that cannot reconcile itself to a new balance of power. The characters in The Power would rather see everyone die, than change. It’s a message that resonates deeply under this presidency.

As a narrative, The Power succeeds brilliantly: It’s tense, engaging, propulsive. You have to keep reading to find out what happens next, even though what happens next is inevitably terrible. The four central characters — Margot, Allie, Roxy, and Tunde — all begin as very recognizable humans. One becomes a prophet, and one an international crime boss, and one a world-renowned journalist / refugee and one a world-changing politician; and it’s a tribute to Naomi Alderman that she makes their journeys (generally) believable.

Yet for all the ambition of the premise, The Power leaves out huge, crucial swathes of human experience in favor of staying within a white, cis, straight comfort zone. Though we’re told that two of the four main characters are people of color, the intersections of race and gender are barely explored. Though Alderman does consider the differing responses in different countries, such as riots in India where women protest sexual harassment, or uprisings in Moldova by trafficked women, she depicts few, if any, divides along racial and religious lines. To the best of my recollection, nobody ever addresses the fact that the renowned prophetess Mother Eve is mixed race. Nor (again to the best of my recollection) does the right-wing backlash — mostly glimpsed through their writings, and never point-of-view characters — launch racist or homophobic attacks. It’s all gender.

Despite the apparent tight focus on gender, Alderman includes no gay or trans characters. There’s a guy character who happens to have a skein, which the book describes as rare, but apart from him we don’t see any of the implications of the premise for sexuality or gender identity. It’s also, frankly, wild to me that in a book where many many characters discuss not needing the majority of men (just a few with good genes for procreation), not one single person talks about queer female sexuality.

These are, I think, real failures of imagination. I would also have liked to see Alderman create a society that was more than a mirror image of the one we have now. While I strongly agree with the premise that women in power would be as susceptible as men to corruption and moral turpitude, I don’t think that the forms that corruption would take would be identical. But in The Power, women do to men all the exact things men have done to women, and in the exact same format and using the exact same language. Alderman depicts this well, convincingly. I just don’t think it’s what would happen. I think it would look different. But this falls under the heading of I wish this book had been attempting a very different project, more than proper criticism.

My final gripe — I swear I enjoyed this book though! — comes with a content warning for childhood sexual abuse. I was uncomfortable from the start with Alderman’s depiction of Allie / Mother Eve as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. I didn’t like the depiction of her as sinister and calculating and nearly incapable of forming genuine connections. Even more maddening, at the end of the book, there’s a reveal that I’m going to spoil because it made me so angry: Allie/Eve learns that the foster father she killed for sexually abusing her was acting at the behest of the foster mother. It’s meant, I think, to be the final twist of the knife that tips Allie into believing the human race is not worth saving. Sexual trauma as plot twist is boring, and lazy, and exploitative. Let’s stop with it, yeah?

Basically I had a ton of thoughts and feelings about the book, and I bet you did too, and I’d love to hear what yours were! Get at me in the comments or on Twitter , because I really want to talk about this book!

Edit to add: My clever friend Jeanne pointed out that the book is fundamentally a satire — very true, and probably the reason I was dissatisfied with some of the worldbuilding. Her review is here .

Share this:

Published in 3 Stars

- Naomi Alderman

With The Power Finale, Author Naomi Alderman Looks to ‘The Future’

The author of the Amazon Prime Video series' source material talks season 2, feminism, and her next book.

Every item on this page was chosen by an ELLE editor. We may earn commission on some of the items you choose to buy.

In the Amazon Prime Video series The Power , adapted from Naomi Alderman’s novel of the same name, the status of women in society is forever shifted when electricity begins to bloom beneath their fingertips. For some, this inexplicable power is a torment. For others, it’s leverage—a means with which to reshape long-standing hierarchies and elevate their sex (and, depending on their motives, themselves).

As The Power makes its second wave in the form of a TV series, which dropped its season 1 finale last night, Alderman spoke with ELLE.com about the challenges of adapting a story as the world changes; her hopes for a second season; and why she needed seven years to finish her next book, The Future .

Tell me about the process of developing this series. What preconceptions did you have going in that you ultimately had to let go of?

It’s a very interesting process, and particularly, nobody expected the global pandemic, so that certainly threw a little spanner in there. I had had a very good experience working on the movie Disobedience , which is based on my novel, and so I went in with high hopes, which indeed have been met by the show. I had a bidding war for the rights before it was published, so I thought, Well, this has got a good chance of becoming something, surely. And I sold the rights to Sister Pictures, who really—they were just incredibly impressive, incredibly ambitious for the show. I then worked on writing the pilot script for probably 18 months to really get that perfect. That was my first TV script. We also had a bidding war in Hollywood between different networks.

And when I had the meeting with Jen Salke at Amazon Studios, by the end of the meeting, she was crying and I was crying, because we had both connected so deeply with the idea behind the show. We put together an incredible writing team, some of whom obviously had to end up dropping out because of the pandemic.

But we’ve had some fantastic writers on board. And we were all ready to go—we were at the beginning of shooting in February 2020, and then we had to put everything away. But, in some ways, I think it worked to the advantage of the material. One of my favorite stories is, even at the end of 2019, people in the writers’ room were saying, “If women developed the power to electrocute people at will, would they really close the schools? How would that even work?” And I feel like now we all understand how...

Yeah, seeing the political bureaucratic response to a crisis in real time had to have helped flesh out your material.

And that feeling that you need to be monitoring, in that type of crisis, what’s happening all around the world. In France, you are watching what’s happened in China, and in the U.S. you’re seeing what’s happening in France, and in Brazil you’re looking at Korea. So that idea of a real global event, I think, in some ways, was helpful for people to understand the show.

This series has landed at a different point in the wider feminist conversation than the book itself, which was published in 2016. A lot of our discourse has shifted. I don’t know if it’s necessarily evolved—

Depends on the individual feminist.

Exactly. But it has certainly shifted in the years since 2016. I’m curious about how that shift impacted the way you approached adapting this material for TV.

Right. So it is interesting. When we were pitching the show, there was a feeling of, Oh, well, maybe because of #MeToo, all this is—we’re done now. Everything’s sorted out. And I think nobody has that feeling anymore. The essential question has become, if anything, more relevant. I think we’re not under any illusions right now that everything is fine, and that we are on an inexorable road toward greater liberation.

I also think that there have been, to me, very upsetting, distressing movements within some elements of feminism where there’s a real hang up about... I’m a trans-inclusive feminist, right? And I find it upsetting that this issue has somehow become something that is separating women from other women, feminists from other feminists, and just at the time when we could do with some unity. Never underestimate the capacity of progressives to attack their own side. So that’s a complicated question. I’m very delighted that we have intersectional representation in the show, that we have trans representation in the show, and it’s a show about women’s liberation in some way. And all of those questions, these are things that we had to think about in order to bring the show up to date. But, unfortunately, the world has not made the question less relevant. It would be nice if it had.

Do you think this shifting conversation has changed the way The Power itself, as a story, is being received and discussed by audiences?

I’ve seen people saying, “Well, this show doesn’t go as far as the book,” and I go, “Well, you’ve only got the first season.”

I firmly believe that you need to have those moments of wish fulfillment before you get into those big hard questions about who has power and what does having power do to them? I definitely think that these days, it’s very important, particularly to a lot of young feminists—and I entirely understand why—that feminist work should be inclusive and intersectional. And I think I’m open to those questions, critiques, and I would say that my work has been improved by talking to audiences and fans. A lot of people have engaged with me in a really loving way and said, “Hey, have you thought about this?” And I’m delighted. I’m always delighted. In my other life, I make video games. I’m the co-creator and the writer of a game called Zombies Run , which we Kickstarted in 2011. When your audience have funded your work, you develop a real openness to discussing it with them.

And I think maybe more than some authors, I don’t know, I’m very happy to hear from my readers, and very relaxed about the idea that sometimes they’re going to tell me that I fucked something up. They’re going to do that, because I’m a human, and they’re going to tell me, and then I’m going to go, “Thank you.”

I’d love to know how, in your opinion, the sort of violence and burn-it-down anger that’s present in a lot of your work, and particularly in The Power , ultimately serves this story rather than detracting from it.

I think one of the things that I’m often up to in my work is trying, if I can, to radically reimagine the status quo, and that’s fun. That’s in the tradition of some of the speculative writing that I love the best. It’s also a philosophical approach. My first degree is in philosophy, and one of the things that you do in philosophy is to imagine, What if things were different? You do a little thought experiment, and then you go, Okay, well, how does it feel?

So in terms of what I’m doing with my work, I think one of the things that I’m most interested in fiction is to see things as if they were different. Just to imagine what it would be like and then go, Okay, well, let me compare that to what we have now. Does it seem like that way of doing things is completely implausible? Or does it seem better? Does it seem interestingly better in some ways and worse in other ways? I guess the burn-it-down energy—which I like, I should get it on a shirt.

I’m a novelist; I’m not a Molotov cocktail thrower, so I’m very interested in thinking about what would happen if we burned it down, rather than in actually doing arson. But I think those questions are incredibly important because we can so easily fall into believing that the way we do things is the only way they can be done. And that’s a trap. That is a limit. Really, possibly, the most profound limit on human freedom is to say the way that things happen here and now is the only way they could possibly happen.

What was behind the decision to end the first season of this series where it does, which is only about a third-ish into the novel?

This is really a question about pacing. Because if somebody had commissioned us to make a season that was, I don’t know, 30 episodes long, each episode an hour, then we would’ve done the whole book.

It’s a complicated book, and what I’ve realized now is that it takes an audience quite a while to get to grips with each set of characters... And also since the book is trying to encompass the whole world, we took the decision that we would need to give the audience some time with each set of characters to really understand them before we start, excuse me, fucking shit up.

So that’s how that decision was made. And obviously, we leave the characters at quite an explosive, exciting point in all of their stories.

What can you tell me about the future of the show?

Well, we’re waiting to hear. I think a lot of it will depend on viewers and where the viewers are, and many questions that are totally above my pay grade. What I can tell you is that I would like to do another couple of seasons of it and get the story done. And not leave it with a kind of, “Yeah, if women could electrocute things, you’ll basically all be great—there might be a little outbreak of violence in a country you’ve never heard of, but apart from that it’ll be fine!”

Your next book, appropriately named The Future , is your first in seven years, and you jokingly alluded on Instagram to the fact that it’s been a little while. I don't mean to ask, “Oh, what took you so long?” But why did you need this time to perfect the story?

I will tell you all the reasons, and one of them is personal—but, also, I feel like it’s something people should talk about more. One reason is I was making a TV show. Another reason is, when I started working on the new novel, it was a novel about a pandemic. And at that point I thought, I can’t write the book like this anymore. Because nobody wants to read that now. So I rethought the book. And the third reason is a sad reason, which is that I had several pregnancy losses in a row.

That’s the honest truth. And I feel like, when people have that experience, there’s a feeling of like, Oh, I want to conceal it. I don’t want to talk about it. But I feel like this is something that happens to a lot of women. And it’s almost impossible to speak about because if you say, “Well, I got pregnant here with my baby,” then everyone goes, “Oh, of course, you had a baby.” But if you just were pregnant a bunch of times and then there’s no baby, then you go, Well, now I’m going to have to let you into some tragedy in my life . But this is the reality of women’s lives; I’m not the only person this has happened to.

So I don’t feel like I have anything to be ashamed about with that, and that’s the truth. And I hope the next one doesn’t take seven years.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Movies & TV 2024

Watch Lily Gladstone’s 'Fancy Dance' Trailer

The Best Drama Series to Stream on Netflix

Wednesday Season 2 Begins Filming

How ‘The Idea of You’ Nails ‘Cool Mom’ Style

When Will 'Challengers' Be Streaming?

'The Idea of You' Changes the Book’s Abrupt Ending

How to Stream The Fall Guy

Who’s the Real Winner of 'Challengers'?

Steve Martin Teases ‘Only Murders’ Season 4

The Buzzy Indie Making Trans Viewers Feel Seen

‘Emily in Paris’ Season 4 Premieres in August

Get recommended reads, deals, and more from Hachette

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Site Preferences

Free shipping on orders $45+ Shop Now .

Contributors

By Naomi Alderman

Formats and Prices

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

- Barnes & Noble

- Books-A-Million

Description

- Praise for THE POWER: "Electrifying! Shocking! Will knock your socks off! Then you'll think twice, about everything." Margaret Atwood

- "Magnificent. I'm agog. I'm several gogs. Smart and scary and sad but true. It's a classic, in the way that it's hard to imagine it ever wasn't there." Joss Whedon

- "Alderman has written our era's Handmaid's Tale , and, like Margaret Atwood's classic, The Power is one of those essential feminist works that terrifies and illuminates, enrages and encourages....This book sparks with such electric satire that you should read it wearing insulated gloves." Ron Charles, Washington Post

- "Narratively complex, philosophically searching, and gorgeously rendered." Lisa Shea, Elle

- "Fierce and unsettling...Through immersive prose and a riveting plot, Alderman explores how power corrupts everyone: those who gain it, and those resisting its loss." Radhika Jones, New York Times Book Review

- "Richly imagined, ambitious, and propulsively written." Sophie Gilbert, The Atlantic

- "Alderman's writing is beautiful, and her intelligence seems almost limitless. She also has a pitch-dark sense of humor that she wields perfectly." Michael Schaub, NPR

- "Alderman's tilted dystopia is a smartly layered place of slippery slopes and moral ambiguities, a fitting folktale for strange times." Leah Greenblatt, Entertainment Weekly

- "I was riveted by every page. Alderman's prose is immersive and, well, electric, and I felt a closed circuit humming between the book and me as I read." Amal El-Mohtar, New York Times Book Review

- "An instant classic of speculative fiction... Smart, readable and joyously achieved." Justine Jordan, Guardian

- "Bold and disturbing...it's not just a book of the moment. The Power is a major innovation in the overlapping genres of feminist dystopia/utopia, science fiction, and speculative fiction." Elaine Showalter, New York Review of Books

- "Fans of speculative fiction (see also: Margaret Atwood and Ben Marcus) about empowered youth will be struck by Alderman's speedy and thorough inhabitation of a world just different enough from ours to jolt the imagination. Mothers, lock up your boys." Sloane Crosley, Vanity Fair

- "Alderman has the daring and good sense to eschew go-girl uplift in favor of terrifying and complex dystopia." Boris Kachka, Vulture/ New York Magazine

- "A suspenseful thrill ride filled with deep, contrasting female leads on a scaffolding of philosophical questions about how different men and women are at heart....Reminiscent of the work of Alderman's mentor Margaret Atwood, The Power is perfect for book clubs, where readers will undoubtedly debate the finer points of nature versus nurture." Jaclyn Fulwood, Shelf Awareness

- "The Power is stupendous. It's gorgeously written, endlessly exciting, fun, and frightening." Ayelet Waldman, author of A Really Good Day

- " The Hunger Games crossed with The Handmaid's Tale. " Cosmopolitan

- "What starts out as a fantasy of female empowerment deepens and darkens into an interrogation of power itself, its uses and abuses and what it does to the people who have it... Alderman's breakout work." Claire Armitstead, Guardian

- "Outstanding... Alderman imagines a world much like ours, with one difference: teenage girls suddenly have the ability to electrocute people. This is the perfect read if you've been itching for something to get you through to season two of The Handmaid's Tale ." Melissa Ragsdale, Bustle

- " The Power is at once as streamlined as a 90-minute action film and as weirdly resonant as one of Atwood's own early fictions... Alderman has conducted a brilliant thought experiment in the nature of power itself...Turning the world inside out, she reveals how one of the greatest hallmarks of power is the chance to create a mythology around how that power was used." John Freeman, Boston Globe

- "This is a thriller that terrifies and leaves behind a lingering tingle that's part discomfort and part exhilaration. Easy to read, hard to put down, difficult to forget." Cory Doctorow, Boing Boing

- "The Power is a subtly funny, lyrical and utterly subversive vision of an impossible future. As all the best visionaries do, Alderman shines a penetrating and yet merciful light on to our present and the so many cruelties in which we may be complicit." A.L. Kennedy

- "Please, please, PLEASE read Naomi Alderman's The Power. It'll crack your brain open in all the right ways. Such an important, timely book." Literary Death Match

- "Audaciously depict[s]...the most extreme results of a movement that seeks rather than interrogates power: That if feminism has become a means for domination, it has lost its way." Bridget Read, Vogue

- "Ingenious....Deserves to be read by every woman (and, for that matter, every man)." Francesca Steele, The Times UK

- "A page-turning thriller and timely exploration of gender roles, censorship and repressive political regimes, The Power is a must-read for today's times." Lauren Bufferd, BookPage

- "Gripping and disturbing, it pushes the reader -- even the confidently feminist reader -- to question the assumptions underlying many of the mechanisms that drive relationships between women and men." Harper's Bazaar UK

- "Alderman's storytelling is visceral and brave; you'll stay up all night reading after a thousand deals with the clock that you'll put it down after just a few more pages. Gleeful, intelligent, clever, and unflinching, The Power is the kind of book to keep a person going." Fiona Zublin, Ozy

- "A searing critique of how power is used in a world in which a long-oppressed class can suddenly fight back." Renay Williams, Barnes & Noble Blog

- "By gleefully replacing the protocols of one gender with another, Alderman has created a thrilling narrative stuffed with provocative scenarios and thought experiments. The Power is a blast." Suzi Feay, Financial Times UK

- "When we say that The Power is profoundly disturbing and you may well want to argue with it as you read, we mean that in a good way." SFX, Five Stars

You May Also Like

Newsletter Signup

Naomi Alderman

About the author.

Learn more about this author

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

May 15, 2024

- Read Alice Munro’s 1994 interview with Jeanne McCulloch and Mona Simpson

- Madeleine Schwartz on losing a native language

- Kathleen Hanna and Brontez Purnell discuss trauma and memoir

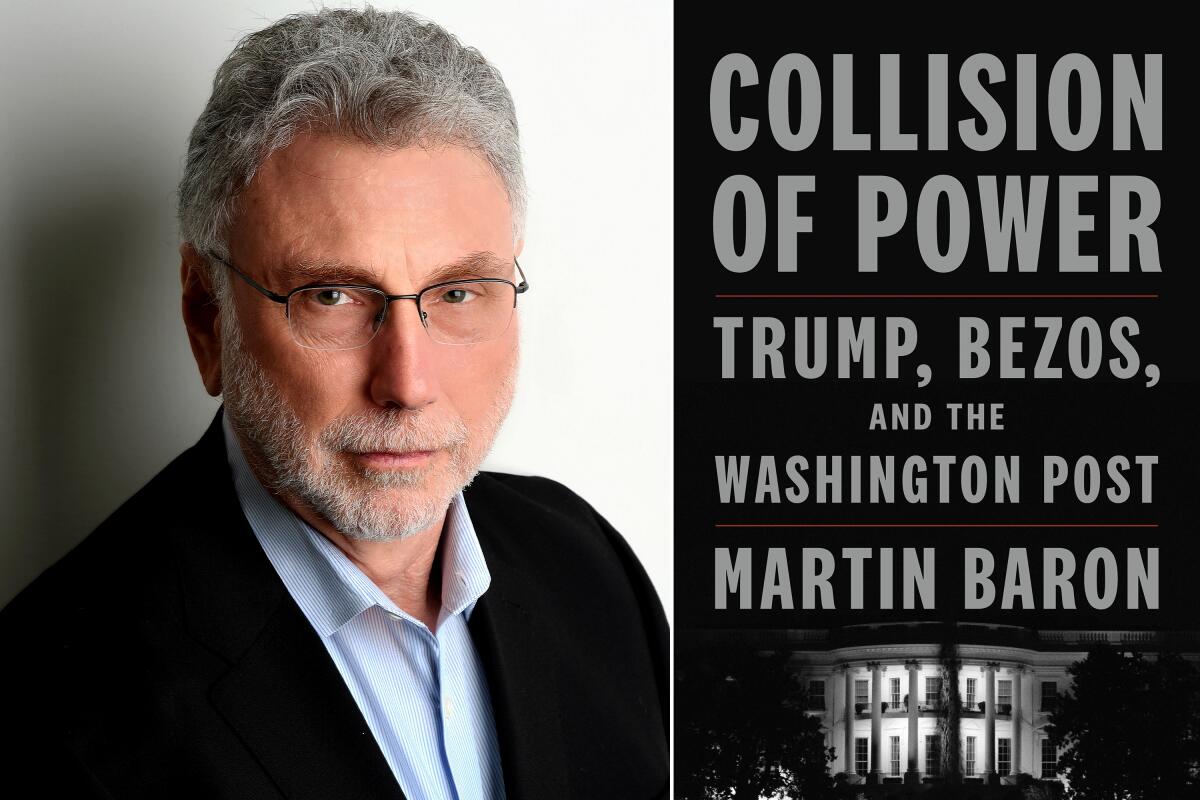

Insiders chart the power and money struggles behind the two biggest U.S. newspapers

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Two Insider Newspaper Accounts

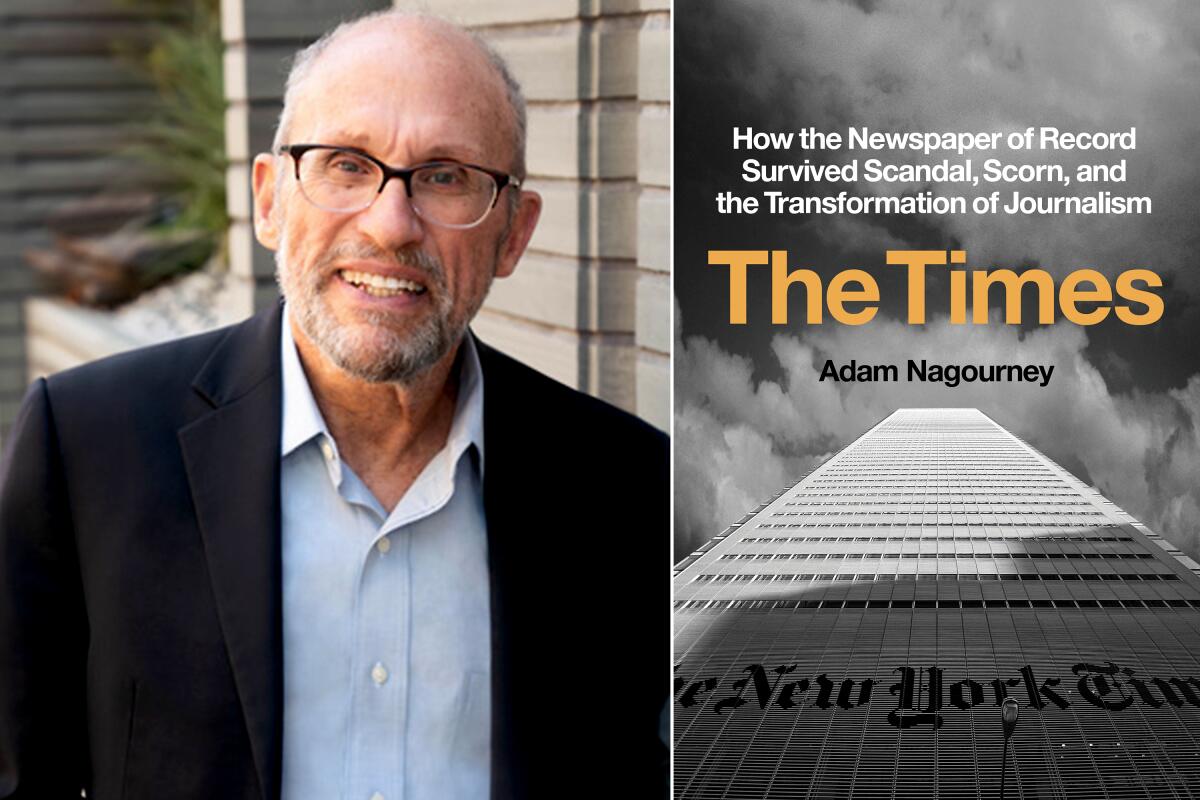

Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and the Washington Post By Martin Baron Flatiron: 560 pages, $35 The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Journalism By Adam Nagourney Crown: 592 pages, $35 If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In the 2015 film “ Spotlight ,” Liev Schreiber played Boston Globe executive editor Martin Baron as “humorless, laconic, and yet resolute.” That is Baron’s own description in “ Collision of Power ,” a reported memoir about his more recent gig as executive editor of the Washington Post.

Baron has no beef with the movie’s portrayal of his leadership of the Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. What does irk him is that his reputation didn’t deter critics from slamming his cautious handling of sexual harassment and assault stories at the Post. “That stung,” he writes.

Amid intense economic pressures and yawning generational, political and cultural divides, life at the apex of the newspaper hierarchy can be nasty, brutish and short. Baron, an avatar of traditional journalistic values, has weathered the challenges better than most. A veteran of both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, he led three newsrooms (the first was the Miami Herald ) to multiple awards and left each on his own terms.

Review: Radiant ‘Spotlight’ illuminates how the Boston Globe covered church sex scandal

“Spotlight” doesn’t call attention to itself.

Nov. 5, 2015

The same can’t be said of several recent top editors of the New York Times, hobbled variously by nettlesome personalities, bad timing and worse luck. Adam Nagourney’s “ The Times ,” an often enthralling chronicle of four decades (1976-2016) of management upheaval and digital transformation, delivers the gossipy goods, thanks in part to interviews with nearly all the surviving principals. Nagourney’s insider status — he still works for the Times, covering West Coast cultural affairs — no doubt contributed to his access.

Media junkies will find both books indispensable. But like Robert Caro ’s biographies, they should appeal to anyone interested in power: how it operates, and how it is lost. The context here is the continuing struggle to keep the news industry solvent, an exhausting pursuit even for the most gifted and resource-rich organizations.

Both volumes offer a version of Great Man (and in the case of the Times, one not-so-Great Woman) history. Neither dwells on the legions of reporters and editors whose careers have been derailed as the business, fixated on declining profits and slow to adapt to the internet, has shed jobs. What the books do show is how these two major news organizations managed to pivot to life-sustaining digital subscriptions while much of the local news landscape lay in ruins.

“Collision of Power” details clashes between the Post and President Donald Trump and between Trump and Jeff Bezos , the multibillionaire founder of Amazon. Bezos scooped up the struggling Post from the Graham family for $250 million in 2013, just months after Baron became executive editor.

Baron repeatedly underlines Bezos’ respect for the Post’s journalistic independence. The newspaper covered Amazon’s business dealings and the tabloid-worthy dissolution of Bezos’ marriage without interference from the boss. Meanwhile, Bezos poured money — within limits — into new hires, upgraded the Post’s technology and, despite threats to his business, ignored Trump’s demands that he curb the Post’s investigative zeal. When his editors were stymied, Bezos himself picked the paper’s new slogan: “ Democracy Dies in Darkness .”

Opinion: Lighten up on The Washington Post. It’s only a newspaper slogan

“Democracy Dies in Darkness.” Film at 11.

Feb. 22, 2017

Baron finds Bezos charming. He does complain mildly that the owner could have spent more time with Post staff — and, more substantively, that Bezos didn’t fully understand the value of editors.

To Post readers, Baron’s recaps of Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage of the Trump administration and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, as well as other investigative coups, will be familiar fare. He does break some news of office strife, reporting that the political staff was more gung-ho about stories on ties between the Trump campaign and Russia than the national security team and Moscow bureau — a divide about which, “stunningly,” he himself wasn’t initially informed.

“Collision of Power” tells us little about Baron’s life and career prior to the Post. Nevertheless, the book is revealing of the man.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter , #MeToo and the police murder of George Floyd , Baron slogged, sometimes ungracefully, through conflicts with his staff over diversity, political participation and the use of social media. Two of Baron’s biggest headaches were the Pulitzer Prize-winning Black reporter Wesley Lowery and Felicia Sonmez , a reporter who identified as a sexual assault survivor. In Baron’s telling, neither cared much for his treasured norm of journalistic objectivity. Both would eventually leave the Post. (Sonmez was fired.)

Baron declares himself “weary of well-meaning but moralistic young journalists — and their forever enabling union — lecturing me on best management practices when precious few had ever managed anyone” or “had any appreciation for the difficult task of meeting ambitious growth goals that bestowed benefits on all of them.”

Review: Local journalism is in crisis. Author Margaret Sullivan shows what’s at stake

The Washington Post media columnist’s ‘Ghosting the News’ diagnoses the disastrous decline in local papers.

July 8, 2020

“Nothing was more hurtful,” he adds, than “the invective leveled against me by colleagues — whose skill and bravery I admired and whose news organization I had busted my butt for eight years to turn around.”

Beneath his vaunted cool, Baron was feeling unappreciated and misunderstood. By the time he retires, in February 2021, it seems he can’t wait to leave.

By contrast, as Nagourney recounts, New York Times executive editors, starting with the legendary A.M. Rosenthal — “self-assured to the point of arrogance” and later “embattled and self-pitying” — often had to be pried out of their jobs. Rosenthal, in fact, had to be pried out twice — the second time, in 1999, from a 13-year tenure as an Op-Ed columnist.

The Times has spawned numerous fine histories and memoirs, including Gay Talese ’s “ The Kingdom and the Power ” (1969), Susan E. Tifft and Alex S. Jones’s “ The Trust ” (1999) and former managing editor Arthur Gelb ’s “ City Room ” (2003). Nagourney’s volume, both candid and fair-minded, is a valuable addition to the canon, adding detail to already well-reported stories.

Nagourney analogizes two abrasive and rivalrous figures, Howell Raines and Jill Abramson . Raines, who presided over the newsroom from 2001 to 2003, frequently tangled with Abramson, then Washington bureau chief. Both, says Nagourney, “were calculating and ruthless when they needed to be and capable of the rawest candor — characteristics that would help lift them to the top of the newsroom.” Their hubris would also contribute to their demise.

World & Nation

New York Times promotes Joseph Kahn to executive editor

The New York Times has named Joseph Kahn as its new executive editor, replacing Dean Baquet as leader of the newsroom.

April 19, 2022

Raines was felled, in large part, by the plagiarism and fraud perpetrated by a troubled young reporter, Jayson Blair . A lesser embarrassment, involving a correspondent relying too heavily on freelance reporting, contributed, as did the widespread staff antagonism Raines had aroused. In the end, Nagourney writes, “he did not see the kindling piling up around his feet.”

Abramson, the Times’ first female executive editor, won the job despite foreign editor Susan Chira’s warning to publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. that her management style was “volatile, sporadically cruel, intolerant of dissent.” As executive editor from 2011 to 2014, Abramson fought what she saw as business incursions into the newsroom and fatally alienated her managing editor and onetime friend, Dean Baquet . After her firing, Baquet (who had briefly served as the L.A. Times’ executive editor) would become the New York Times’ first Black executive editor.

Interwoven with these juicy, neo-Shakespearean tales is Nagourney’s account of the Times’ digital pivot, “a messy and occasionally embarrassing exercise that had sometimes seemed destined for failure.” The Times’ 2011 implementation of a paywall was copied successfully by the Washington Post, less so by other newspapers around the country. (And even the Post, since Baron’s departure, has been flailing financially , according to reporting in the New York Times.) This complex story — of just-in-time transformation and its national fallout — likely merits a book of its own.

Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, was a longtime reporter and editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer and a contributing editor at the Columbia Journalism Review.

Book Club: Martin Baron

What: Former Washington Post Editor Martin Baron joins the L.A. Times Book Club to discuss “Collision of Power” with Times Executive Editor Kevin Merida .

When: Oct. 11 at 6 p.m.

Where: USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, 3630 Watt Way, Los Angeles. Get tickets on Eventbrite for this live, in-person conversation, also available virtually.

Join: Sign up for the book club newslette r for the latest book, news and live journalism events.

More to Read

A letter to readers

April 9, 2024

L.A. Times Executive Editor Terry Tang solidifies leadership position

April 8, 2024

Commentary: How ‘The Girls on the Bus’ depicts journalists would be fun, if it weren’t so dangerous

March 14, 2024

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Column: L.A.’s only Spanish-language children’s bookstore will soon get más grande

May 15, 2024

The week’s bestselling books, May 19

A gender-fluid childhood at an RV park in the desert. Zoë Bossiere wouldn’t change a thing

20 new books you need to read this summer

- Literature & Fiction

- Genre Fiction

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -38% $16.25 $ 16 . 25 FREE delivery May 22 - 29 Ships from: Yanakman Sold by: Yanakman

Save with used - acceptable .savingpriceoverride { color:#cc0c39important; font-weight: 300important; } .reinventmobileheaderprice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerdisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventpricesavingspercentagemargin, #apex_offerdisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventpricepricetopaymargin { margin-right: 4px; } $7.85 $ 7 . 85 free delivery thursday, may 23 on orders shipped by amazon over $35 ships from: amazon sold by: jrl33 enterprises, return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

The Power Hardcover – October 10, 2017

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 400 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Little, Brown and Company

- Publication date October 10, 2017

- Dimensions 6 x 1 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 0316547611

- ISBN-13 978-0316547611

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Little, Brown and Company; First Edition (October 10, 2017)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 400 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0316547611

- ISBN-13 : 978-0316547611

- Item Weight : 1.5 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1 x 9 inches

- #771 in Dystopian Fiction (Books)

- #1,030 in Coming of Age Fiction (Books)

- #1,115 in Post-Apocalyptic Science Fiction (Books)

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Amazon Videos

About the author

Naomi alderman.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

clock This article was published more than 4 years ago

Why Christian nationalists think Trump is heaven-sent

Early last month, President Trump took the stage at the bipartisan National Prayer Breakfast, held up that day’s papers to celebrate his impeachment acquittal and expressed his sense of persecution over his “terrible ordeal.” “When they impeach you for nothing, then you’re supposed to like them?” he said. Many critics were dismayed by Trump’s refusal to engage with the keynote speaker’s Christian message of love for one’s enemies. But, as Katherine Stewart shows us in her ambitious new book, “ The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism ,” there are many ways of being publicly Christian. Some of them are about domination, not humility.

Throughout this fast-paced account, Stewart brings the reader into the halls of power, past and present, that have given us the world of 2020. From a Capitol Ministries fundraiser at the World Ag Expo in Tulare, Calif., to the World Congress of Families in Verona, Italy, Stewart traverses the globe, making a clear case for how deeply Christian nationalism is intertwined with U.S. domestic and foreign policy.

The book’s title is a pun, and it’s an apt one. What stands out the most from this gripping volume is how a reverence for authority — if the right person is in charge — is encoded into the various strands of this movement. Stewart argues that “Christian nationalism is not a religious creed but, in my view, a political ideology.” “Christian nationalism” is an accurate phrase. It is also Stewart’s way of saying #NotAllChristians, which is certainly the case. It also means she is focused on how Christian nationalists exercise political power, not their private actions or personal beliefs.

That political power, however, cannot be separated from some strands of Christian theology. Many critics of the Trump administration fear that the United States is in danger of losing its status as a democracy. “The Power Worshippers” shows us how deeply our current political trajectory is driven by another Christian theo-political notion: the divine right of kings.

As Stewart writes: “When God sends a ruler to save the nation, He doesn’t mess around; He sends a kingly king. And kings don’t have to follow the rules.” She clearly demonstrates how Trump’s policies on school “choice” and health care, and his support for conservative regimes abroad, continue political battles that were set in motion decades ago, from Paul Weyrich’s engineering of the New Right in the 1970s to the dismantling of the establishment clause — the portion of the First Amendment that prevents the government from favoring one religion over another — since the early 1980s. It’s a long playbook. The difference now is just how thoroughly this rhetoric of Christian kingship has saturated national discourse, and how technologies like data mining and social media bots have helped it spread.

What many anti-Trump commenters sometimes miss, in their criticisms of Christian nationalists’ embrace of Trump, is how the allegiance-driven nature of his presidency is precisely what appeals to this constituency. Stewart is attuned to this trope. In one scene, Jack Hibbs, pastor of Calvary Chapel Chino Hills in California, speaks to a rapt audience at a Church United rally. “I’m not a Republican or a Democrat. I’m a Christian — which makes me a monarchist if you think about it!”

There’s a wink and a nod in that statement, but also a profound truth. The Christian Bible is saturated with images of kingship, from David and Solomon to poetry comparing God to a king.

Historically speaking, there is no such thing as a “biblical worldview,” despite the fact that this phrase animates the Museum of the Bible (established in Washington by the Green family, which owns Hobby Lobby) and other examples throughout the book. What we now call the Bible incorporates dozens of texts written over more than a millennium, evincing a multiplicity of approaches to life, the universe and everything.

But as Stewart shows us, today’s Christian nationalist power brokers are dedicated to the monarchical strand within biblical texts. Trump is not just any president. He is the anointed one, “God’s candidate,” according to David Barton, a former math teacher who vigorously (and often inaccurately) promotes that idea that the United States was founded as a Christian nation. Many Christian nationalists evoke King Cyrus, the ancient Persian king who defeated the Babylonians and is praised in the Hebrew Bible for allowing the exiled Judeans to return to their homeland. For these supporters, Trump’s pro-Christian policies and appointees make him a modern-day Cyrus, an “imperfect vessel” selected by God to provide liberty to Christians.

In other words, despite its concern for religious freedom, Christian nationalism is not libertarian, or even anti-government, so long as the right people (the best people?) are calling the shots. As Stewart writes, “The many paradoxes and contradictions of Christian nationalism make sense when they are taken out of the artificial ‘culture war’ framing and placed within the history of the antidemocratic reaction in the United States.”

Many of the trends Stewart discusses will be familiar to anyone who has read a good deal of U.S. religious history or who has been following the latest reporting by Stewart herself, or by Jeff Sharlet, Sarah Posner, and more journalists, historians and sociologists than I can name in this review (Stewart credits all of them throughout the text). What’s so impressive is how seamlessly she weaves it all together. Her synthesis of previous scholarship, combined with her deft on-the-ground reporting, makes for a strong, if sometimes overwhelming, narrative.

One of the best things about “The Power Worshippers” is Stewart’s ability to paint a vivid, even empathetic, picture of her interlocutors. Her section on California pastor Jim Domen, the founder of Church United, who identifies as a former homosexual, is particularly well-written and nuanced. She’s also prone to clever, even humorous turns of phrase: “The Bible is the Forrest Gump of history” and Barton is the “Where’s Waldo of the Christian nationalist movement” are particularly entertaining asides.

The book’s final chapters poignantly illustrate the personal and global stakes of putting Christian nationalist policies into action. One chapter details the traumatic and sometimes fatal experiences of women who were denied reproductive health care because of ethical and religious directives that govern Catholic health-care providers. Other chapters detail the role that firms owned by Christian conservatives play in data mining and make it abundantly clear that the 2020 election stakes are high: Organizations like the Faith and Freedom Coalition mobilize likely Christian nationalist voters based on enormous troves of demographic data. “The Power Worshippers” is required reading for anyone who wants to map the continuing erosion of our already fragile wall between church and state.

The Power Worshippers

Inside the dangerous rise of religious nationalism.

By Katherine Stewart

Bloomsbury. 342 pp. $28

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Based on the New York Times bestseller, The Power is our world, but for one twist of nature. Suddenly, women develop a mysterious new ability to electrocute at will, leading to an extraordin... Read all Based on the New York Times bestseller, The Power is our world, but for one twist of nature. Suddenly, women develop a mysterious new ability to electrocute at will, leading to an extraordinary global reversal of the power balance Based on the New York Times bestseller, The Power is our world, but for one twist of nature. Suddenly, women develop a mysterious new ability to electrocute at will, leading to an extraordinary global reversal of the power balance

- Naomi Alderman

- Sarah Quintrell

- Raelle Tucker

- Toni Collette

- Toheeb Jimoh

- 91 User reviews

- 24 Critic reviews

- 1 win & 5 nominations

- Margot Cleary-Lopez

- Jos Cleary-Lopez

- Bernie Monke

- Matty Clearly-Lopez …

- Darrell Monke

- Barbara Monke

- Helen Wright

- Tatiana Moskalev

- Izzy Cleary-Lopez

- Daniel Dandon

- Ricky Monke

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia Based on the 2016 novel of the same name by Naomi Alderman. Along with being tapped for screen adaptation, The Power was named one of the top 10 books of 2017 by the New York Times.

User reviews 91

- Apr 12, 2023

- How many seasons does The Power have? Powered by Alexa

- How does season one of The Power differ from the novel?

- Is this a good adaptation?

- March 31, 2023 (United States)

- United States

- The Bridge Studios - 2400 Boundary Road, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada (Studio)

- Amazon Studios

- CAMA Asset Storage & Recycling

- Sister Pictures

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

Related news, contribute to this page.

- IMDb Answers: Help fill gaps in our data

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

May 23, 2024

Current Issue

Joseph Giovannini

Joseph Giovannini is a critic, architect, and teacher based in New York and Los Angeles. He has written for The New York Times , The Los Angeles Times , New York magazine, Architect magazine, and Architectural Record , and has taught at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, UCLA’s Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning, the University of Southern California’s School of Architecture, and the University of Innsbruck. His book Architecture Unbound: A Century of the Disruptive Avant-Garde will be published in 2021. (October 2020)

The Redesign of LACMA: An Exchange

The CEO of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art debates the architectural critic’s evaluation of his institution’s renovation.

October 23, 2020

The Demolition of LACMA

Asked recently at a dinner party what he thought of the new building design, Frank Gehry simply draped a napkin over his head.

October 2, 2020

Subscribe and save 50%!

Read the latest issue as soon as it’s available, and browse our rich archives. You'll have immediate subscriber-only access to over 1,200 issues and 25,000 articles published since 1963.

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Nellie Bowles’s Failed Provocations

By Molly Fischer

The journalist Nellie Bowles writes a column called “TGIF” for the Free Press, a new media company she started with her wife, Bari Weiss. Both women previously worked at the New York Times : Bowles was a tech reporter, and Weiss was a right-leaning opinion writer and editor before resigning with an open letter lamenting that the paper was now ruled by a “mob” enforcing a “new orthodoxy.” The Free Press styles itself as an antidote to the woke excesses of mainstream institutions, and “TGIF” provides a weekly roundup of headlines on its pet concerns, garnished with Bowles’s jesting commentary. “I’m wearing my old Columbia sweatshirt and a Hamas headband—the look of the season,” one recent installment , covering the protests at her alma mater, begins.

When Joan Didion died , in December, 2021, “TGIF” included a tribute to her influence. Didion had “inspired a generation of young writers including this one” with work that “skewered the trendy movements around her,” Bowles wrote . “The Didion I read would quietly find the flabbiest bits of American culture. She was ruthless and funny. She was not on your side. She wasn’t on anyone’s side. If Didion had been working these past few years, I have no doubt who she’d be writing about.”

With a new book called “ Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History ,” Bowles seems to be making a bid for Didion territory. Her title evokes “On the Morning After the Sixties,” Didion’s 1970 meditation on her fundamental alienation from the previous decade’s idealism. Weiss declared her wife “the lovechild of Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion.”

Bowles’s subject in “Morning After the Revolution” is what she variously refers to as “the revolution,” “the movement,” and “the New Progressive”—more or less what Elon Musk would call “the woke-mind virus”—and she presents herself as an apostate of left-wing orthodoxy. “I owe a lot of my life to political progressivism,” she writes, of her evolution. “I bristled at the alternative, which certainly wouldn’t want me.” She volunteers bona fides:

I ran the Gay-Straight Alliance at my high school, and I was the only out gay kid for a while, sticking rainbows all around campus. After college, I fit in well with the Brooklyn Left. I’ve been to a reading of The Nation writers at the Verso Books office, and, my God, I bought a tote. When Hillary Clinton was about to win, I was drinking I’m With Her-icanes at a drag bar.

No inveterate outsider à la Didion, she was, if not a fellow-traveller of the revolution, at least a fellow-commuter, generally on board for her cohort’s quotidian habits and conventional wisdom. But she began to harbor doubts about its growing fervor, and the social opprobrium she experienced after meeting Weiss, “a known liberal dissident,” in 2018, exacerbated those doubts. She saw her peers in the media business adopting new jargon and publishing stories that identified potential racism in everything from Alzheimer’s drugs to organic food; she felt that questioning these developments was impermissible. Around 2020—amid the pandemic, George Floyd’s murder, and the responses, both cultural and political, that each provoked, including Weiss’s resignation—things, in Bowles’s estimation, “went berserk.” When protesters established a police-free “autonomous zone” in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood that summer, she wanted to check it out, but colleagues discouraged her. Her reportorial instincts were being squelched, she felt. (She eventually made it to CHAZ , the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, where she wrote a story on unhappy business owners.) In 2021, she left the Times , and set out to report a forbidden truth—that the left can be somewhat goofy. She writes, in the introduction to “Morning After the Revolution,” “The ideology that came shrieking in would go on to reshape America in some ways that are interesting and even good, and in other ways that are appalling, but mostly in ways that are—I hate to say it—funny.”

No one who remembers the day that Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer wore kente-cloth stoles could argue that the past four years have lacked episodes of dazzling absurdity. Periods of social change come with shifting codes of behavior, exposing individual foibles and institutional ineptitude; people caught in the undertow of history flail revealingly. All this has made rich fodder for nonfiction prose since the days when the New Journalism took shape in the sixties and seventies, wielding novelistic detail and authorial subjectivity to capture that era’s tumult. Wolfe, the form’s self-appointed promoter, framed the New Journalism as a project of depicting status—minute gradations of subcultural hierarchy—long before anyone talked about “virtue signalling.” In “Radical Chic,” Wolfe crashes a party at Leonard Bernstein’s Park Avenue penthouse thrown to benefit the Black Panthers; he describes the nut-covered Roquefort morsels circulated on trays, and also the special frisson of supporting a cause that, guests were warned, might not be tax deductible. His anthropological scrutiny of manners and ritual make the scene indelible.

Didion’s writing on the counterculture circled an apocalyptic dread that lay beyond Wolfe’s status jockeying—but her own unsparing discernment sliced through cliché and attuned her to nuances of style and character. In a withering report on Joan Baez’s Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, she portrays its founder not as a vacuous-hippie stereotype but as “an interesting girl, who might have interested Henry James,” clad in Irish lace and serenely confident at a county-board meeting as she faces down her irritated neighbors. Didion and Wolfe brought skepticism to writing about their era’s would-be revolutionaries, but they also brought a novelist’s eye for character—a basic interest in understanding why human beings behave the way they do. Their critique rested on an acute perception of their subjects’ particular vanities.

Bowles is going for something similar. “I want you to see the New Progressive from their own perspective, not as a caricature,” she writes, near the beginning of her book. “Morning” starts with the protests in the summer of 2020 and follows a loosely chronological structure. She discusses privilege workshops and puberty blockers, the anti-racism guru Robin DiAngelo and the viral-recipe master Alison Roman, CHAZ in Seattle and the Echo Park homeless encampment in Los Angeles and the progressive former district attorney Chesa Boudin in San Francisco.

It is difficult, though, to see Bowles’s subjects as more than caricatures when her descriptions of them are so generic. She writes that Seattle’s sixtysomething mayor has “hair perfectly blown out into the helmet that’s popular for successful women of that age.” Protesters in their teens and early twenties, meanwhile, possess “that coiled squirrely energy men have then.” At such moments, Bowles is not identifying and describing types; she is gesturing toward them, relying on readers to supply a portrait they already have in mind. Her characterization of emergent activist groups that collected donations and attention in 2020 and 2021 is similarly blank: they are “the flashiest new organizations with the best names and the sharpest websites,” or “cool, flashy nonprofits,” or “trendy groups”; in any case, they have “chic websites.” The incrementalist old-guard organizations have “basic websites.” What constitutes a flashy nonprofit, and, when you visit its Web site, what appears onscreen? Bowles doesn’t say. And “Morning After the Revolution” is a book that involves a good deal of staring at screens. Several set pieces—courses Bowles takes called “The Toxic Trends of Whiteness” and “Foundations of Somatic Abolitionism,” a panel for Times staffers on asexuality, a Columbia event on police abolition, all of which occurred online—amount to summaries of Webinars.

It’s not Bowles’s fault that events in 2020 and 2021 often happened via videoconference. But, for the reader, there is a dispiriting flatness to the results. Imagine “Radical Chic” with no penthouse, no eavesdropping, no combustible social chemistry, no outfits, no Roquefort morsels—just a transcript of unknown people, identified by a first name and maybe a hair style, addressing a group and saying cartoonish things. It’s a truism that humor dwells in specificity, and this principle works against Bowles’s efforts at bitingly observed social commentary. Instead, she resorts frequently to blunt-force sarcasm: according to the media, violent protesters are “good, very good”; according to clinicians, gender-dysphoric teens are “very wise.” She writes, “The movement makes new moral rules so fast that ‘brown-bag lunch’ and ‘trigger warning’ are actually bad now. You’re probably bad.”

You can picture a writer following up with her somatic-abolitionism classmates post-Zoom to discuss whether they have persisted in the practice (it involves humming and swaying), and fleshing out a sketch of who pays for such a class in the first place. But Bowles seems hesitant to engage personally or at length with the revolution’s foot soldiers. The people she speaks with instead tend to be the irritated neighbors, bewildered bystanders, disillusioned allies, proponents of moderate alternatives, and officials with talking points. The voice of the revolution comes from public statements, whether quoted in the media, posted on the Internet, or shouted at protests. The primary voices in a chapter on trans children (“Toddlers Know Who They Are”) are doctors and medical administrators whose quotes seem to come from lectures and videos available online.

Some figures whom Bowles considers (such as Tema Okun, the author of a widely circulated guide to “white supremacy culture”) decline to be interviewed. At demonstrations, protesters regard her warily and sometimes block her view of their activity with umbrellas. Bowles regards this as proving a point—that the revolutionaries are insular and refuse to talk to skeptics—and takes it as an excuse not to change their minds. Her account of a trans-rights protest leans on quoting things yelled by a person Bowles calls “Green Shorts,” who was wearing green shorts and yelling. Didion described herself as “bad at interviewing people”; still, she managed to sustain a level of intimacy with her subjects sufficient to get behind closed doors and see, say, a child on LSD (as in one famous scene in “ Slouching Towards Bethlehem ”). “Writers are always selling somebody out,” Didion warned, but Bowles never gets close enough to expose anything sensitive to public view. You can’t sell out a stranger on the street.

In the absence of such fine-grained scrutiny, Bowles is left rehearsing the conservative commentariat’s greatest hits of left-wing piety run amok—stuff like the “progressive stack,” a method of prioritizing speakers based on their degree of oppression, which has found greater purchase as an anti-woke punching bag than as an actual practice. “It gets messy,” Bowles writes. “Would a white gay guy go ahead of a straight Asian man? Is a trans teenager more oppressed than someone in a wheelchair?” (“Think of the sticky moral quandaries,” the Times columnist Pamela Paul mused last month on the same subject. “Who is more oppressed, an older disabled white veteran or a young gay Latino man? A transgender woman who lived for five decades as a man or a 16-year-old girl?”)

Perhaps, given that Bowles counts herself a former member of the revolution’s social milieu, she’s reasoned that her voice represents it sufficiently. Yet even when discussing her own experiences she can be coy to the point of evasiveness, to the detriment of her credibility. “All the smart people are buying guns,” her chapter on police abolition begins. “That’s what I told myself waiting in line for one.” She never thought that she’d buy a gun, she writes—but she starts hearing about crime in her neighborhood, and then she finds out she’s pregnant. “Almost as soon as I peed on a stick, I got in the car and found myself holding an AR-15, getting a sense of the heft.” Would a shotgun or a pistol be better, she wonders, and where should she put a gun safe? Though she goes on to detail the brand of her home alarm system and the monthly cost of her neighborhood’s private security patrol, she never says what kind of gun she bought, if indeed she bought one.

The early pandemic was a time when countless people were trying to navigate the biggest disruption to American life since the Second World War, and they did it while peering into their phones, where brands, radicals, charlatans, eyewitnesses, experts, and hapless civilians all jumbled together in the same feeds. Bowles is not wrong—it’s funny that there was an interlude when the C.I.A. felt compelled to share a recruiting video touting intersectionality. Indeed, there is an abundance of material within easy reach: corporate lip service to racial justice, viral news stories, videos of lectures and street confrontations, provocations of all sorts on Twitter. Her book raises a question that Wolfe and Didion, working in the sixties and seventies, never had to face. How does a writer make use of such material in a way that takes into account the peculiar perspective—at once vividly proximate and remote—that online detritus affords?

It seems impossible to extricate the revolution that Bowles wants to describe from the context of social media—the realm of cancel-culture callouts, virtue signals, subcultural warrens at once noisy and arcane. (“Twitter has become [the Times ’] ultimate editor,” Weiss wrote in her resignation letter.) But, despite Bowles’s past reporting on tech culture, this isn’t an aspect of the period she ever brings into focus. The book just reflects, unexamined, an experience—hers—of being caught in the online slipstream. “The transition from Black Lives Matter to Trans Lives Matter was seamless,” she writes. “The movement simply pivoted: The conversation about racism was now about transphobia. Done! Go!” Maybe this was how it felt scrolling through Instagram at the time; on the page, it reads as incuriosity, even credulity. Surely a book premised on a united and overpowering new movement ought to offer some account of how the people, the institutions, and the ideas it encompasses came into concert. Lacking that, the main thing that B.L.M., pediatric gender clinics, and San Francisco NIMBY s appear to have in common is that they began to vex Bowles around the same time.

In “Morning After the Revolution,” Bowles writes dismissively that her reporting on Silicon Valley for the Times “fit right in” with the Trump-era resistance mind-set that prevailed at the paper. The revolution, she suggests, was happy to look askance at the tech-bro sexism and wacky élite fads that she was then covering. Bowles may feel that she’s moved on to bolder work now, but she found more texture and nuance in her reporting about tech than in anything that appears in her book. The stories she was writing just before the pandemic about screens and human connection have a prescient ambivalence: she conveyed both technology’s power as a lifeline and her own misgivings about what it might portend. But, around the time she remembers the world going berserk, something changed. “Now I have thrown off the shackles of screen-time guilt,” she wrote , in spring of 2020—in retrospect, perhaps a touch ominously. “My television is on. My computer is open. My phone is unlocked, glittering.” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

The day the dinosaurs died .

What if you started itching— and couldn’t stop ?

How a notorious gangster was exposed by his own sister .

Woodstock was overrated .

Diana Nyad’s hundred-and-eleven-mile swim .

Photo Booth: Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged portraits of Black love .

Fiction by Roald Dahl: “The Landlady”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Gary Shteyngart

By Meg Richardson

By Roz Chast

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Tesla Pullback Puts Onus on Others to Build Electric Vehicle Chargers

The automaker led by Elon Musk is no longer planning to take the lead in expanding the number of places to fuel electric vehicles. It’s not clear how quickly other companies will fill the gap.

By Jack Ewing and Ivan Penn

Elon Musk, the chief executive of Tesla, blindsided competitors, suppliers and his own employees this week by reversing course on his aggressive push to build electric vehicle chargers in the United States, a major priority of the Biden administration.

Mr. Musk’s decision to lay off the 500-member team responsible for installing charging stations, and to sharply slow investment in new stations, baffled the industry and raised doubts about whether the number of public chargers would grow fast enough to keep pace with sales of battery-powered cars. It put the onus on other charging companies, raising questions about whether they can build fast enough to address a shortage that appears to be discouraging some people from buying electric cars.

As the owner of the largest charging network in the United States, Tesla has a powerful effect on people’s views of electric cars.

“There is certainly a psychological component,” said Robert Zabors, a senior partner at Roland Berger, a consulting firm. “Availability and reliability are critical to overall E.V. adoption.”

Tesla’s change of direction, only days after it had told shareholders in a securities filing that it would “rapidly” expand its charging network, which it calls Supercharger, is likely to delay construction of fast chargers, which are concentrated along the two coasts and in parts of Texas.