Decision Making in Social Work

- © 1999

- Latest edition

- Terence O’Sullivan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- The first text to address the core skill of decisionmaking in social work Offers a coherent synthesis of a previously fragmented literature Develops an innovative framework that systematically addresses the complexity of practice without oversimplification

875 Accesses

27 Citations

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Other ways to access.

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

Social Justice and Social Work

Key Social Work Frameworks for Sociologists

- decision making

- decision-making

- organization

- social work

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, making decisions, decision making contexts, involving the client, stakeholders meeting together, thought and emotion in decision making, framing the decision situation, choice of options, evaluating decisions, conclusions, back matter, about the author, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Decision Making in Social Work

Authors : Terence O’Sullivan

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-14369-6

Publisher : Red Globe Press London

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social & Cultural Studies Collection , Social Sciences (R0)

Copyright Information : Terence OSullivan 1999

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIII, 216

Additional Information : Previously published under the imprint Palgrave

Topics : Social Work

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Find a Social Worker

- NSCSW Staff

- NSCSW Council

- Board of Examiners

- Strategic Plan: Our Foundation for Growth

- Social Policy Framework

The Nova Scotia College of Social Workers exists to serve and protect Nova Scotians by effectively regulating the profession of social work.

- New Member Orientation

- Student Members

- Associate Members

- Member Committees

- Professional Development Activities

- Registration Fees

As a member you have the ability to support the NSCSW in building a professional community that embodies the best of social work practice.

- Standards of Practice

- Normes de pratique

- Code of Ethics

- Candidacy Mentorship Program

- Professional Development Standards

- Practice Guidelines & Resources

Ensuring Nova Scotians receive the services of skilled and competent social workers who are knowledgeable, ethical, qualified, and accountable to the people who receive social work services.

- Finding a private practitioner

- Benefit plan coverage for social work

- Clinical Registration

- Private practice resources

Private practitioners are self-employed RSWs who are licensed to practice independently in one or more areas of specialization.

- Canadian BSW/MSW

- Registration Transfer From Another Province

- Telepractice From Outside NS

- United States BSW/MSW

- International BSW/MSW

- Registration Appeal

We establish, maintain, and regulate Standards of Professional Practice to ensure Nova Scotians receive the services of skilled and competent social workers who are knowledgeable, ethical, qualified, and accountable to the people who receive their services.

- National Social Work Month

- 2024 Conference: Celebrating Courage

- Connection Magazine

- Bi-Weekly Newsletter

- Employment Listings

Stay up to date on the latest news and events happening with NSCSW.

Ethical Decision Making Tool

Event_note upcoming events.

The Ethical Decision Making Tool

Are you reflecting on an ethical dilemma?

This tool includes interactive options to guide Nova Scotia Registered Social Workers through the CASW Code of Ethics and the NSCSW Standards of Practice (2015).

Ethical Decision Making

Our experiences and values influence ethical decision-making. That’s why it’s important for social workers to seriously consider the perspectives of those they work with, the environments they are working in and the influence of the dominant narrative. Throughout the ethical decision-making process, we encourage reflection on one’s own value system, emotions, and positionality in relationship to these broader systems.

Social Work Philosophy & Ethics

Social work values are embedded in principles of social justice and Humanitarianism. The social work worldview is often distinct from the dominant ideology (how issues are represented in our society at large). Dominant values are presented as though they apply to everyone but are often the values of elites or ruling powers in society, such as the state. We still battle prejudices related to race, gender, and class etc.

Social work can act as the conscience of society. As social workers, we bare witness to suffering and help people find their voice. That is the “noble” part of our professional identity. There have always been courageous social workers who “spoke truth to power” and challenged the dominant view (Spencer, Massing and Gough,2017).

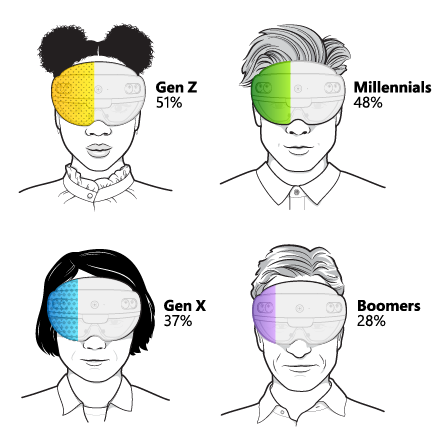

Intersectionality

Post-modern social work philosophy and ethics are guided by intersectional theory which promotes thinking about multiple identities and how systems of oppression are interconnected through ethnicity, class, and gender… etc which are experienced simultaneously, not ‘one at a time (Mullaly, 2009). The theory holds that each person holds different degrees of oppression and privilege based on our relative positioning along axes of interlocking systems of oppression. Where each of us lies in relation to the center and the margin —our social location—is determined by our identities, which are necessarily intersectional (Hulko, 2004).

Our social location refers to the relative amount of privilege and oppression that individuals possess on the basis of specific identity constructs, such as race, ethnicity, social class, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, and faith” (Hulko, 2009, p. 5). Differences in class, in social and economic power, in educational opportunity and achievement, in health and physical well-being, are the expression and result of institutionalized inequalities in opportunity and socialization through the narrative of the dominant ideology. Such differences perpetuate and increase the social imbalances in power and thereby serve to maintain all forms of oppression (Mullay,2009).

Intersectional theory informs social workers on how to build professional helping relationships. Rooted first through the concept of empathy, or living in someone else’s shoes, intersectional theories guide social works to understand our shared experience with a client, drive a mutual need to collaborate, while addressing collective problems that have created these issues. Empathy leads to us to work in solidarity with clients towards liberation from oppressive structures (Mullaly, 2009). When we recover the buried memories of our socialization, to share our stories and heal the hurts imposed by the conditioning, to act in the present in a humane and caring manner, to rebuild our human connections and to change our world (Sherover-Marcuse, 2015.)

Relational Ethics

Intersectionality informs social workers on how to co-create meaning with clients. Traditionally, care is often thought of as flowing one way–from professional to client in the case of social work. The notion of relational ethics helps us to see care as something that happens in the space between us, what some have called the “third space” (Spencer, Massing and Gough, 2017). Care is neither about you nor I alone, but a process of co-creating a better story that happens between us. That is, it brings together a space in which we are all equal in our humanity. In practice, this may mean that as professionals, we take primary responsibility for the helping process but freely share the process of co-creation (Spencer, Massing and Gough,2017). In action this may mean:

- We put the other’s needs in the forefront for the moment.

- We are emotionally present to the other, attentive to their story.

- We resist the urge and need to immediately fix the problem (or what we think is the problem).

- We help people to empower themselves.

- We share appropriately how the other’s story touches us.

- We take responsibility for our ethical practice but share ethical dilemmas with the other as appropriate (Spencer, Massing and Gough, 2017).

Intersectional thinking pushes us to work in solidarity with clients to liberate both the undoing effects and of the causes of social oppression. These changes will involve transforming oppressive behavioral patterns and “unlearning” oppressive attitudes and assumptions (Mullay, 2009).

Dolgoff, R., Loewenberg, F. M., & Harrington, D. (2009). Ethical issues for social work practice.

Gough, J. & Spencer, E. (2014) Ethics in action: An exploratory survey of social workers ethical decision making and value conflicts. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics vol. 11. 2. (pp 23-39).

Hulko, W. (2004). Social science perspectives on dementia research: Intersectionality. Dementia and social inclusion, 237-254.

Hulko, Wendy (2009). The time-and context-contingent nature of intersectionality and interlocking oppressions.” Affilia 24.1 (2009): 44-55.

Mattsson, T. (2014). Intersectionality as a Useful Tool Anti-Oppressive Social Work and Critical Reflection. Affilia, 29(1), 8-17.

Mullaly, R. P. (2010). Challenging oppression and confronting privilege: A critical social work approach. Don Mills, Ont: Oxford University Press.

Spencer E; Massing, D & Gough, J (2017)Social Work Ethics; Progressive, Practical, and Relational Approaches; Oxford Press.

Questions? Contact the College’s Executive Director/Registrar, Alec Stratford at [email protected].

June 3, 2024 — Highlights of our special general meeting and annual general meeting in May.

May 24, 2024 — The NSCSW is hiring a Professional Development Consultant. Applications close on June 18, 2024.

Sign up for Connection

CONNECTION is the official newsletter of the Nova Scotia College of Social Workers.

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work Case Study

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Inclusivity and diversity imply acceptance of differences, awareness of their value, and profitable use of the uniqueness of each. Inclusivity removes barriers that prevent a person from gaining access to a specific area: education, the ability to make political decisions, culture, and others. Primarily, it relates to ethical decision-making because all points of view should be considered in any workplace (Banks & Nøhr, 2012). The ethics of decision-making is choosing one of the alternative ways of solving a problem based on the foresight of the immediate and long-term consequences of the decisions made and their responsibility.

Decision-making is an integral part of the ethics of responsibility. At the level of everyday practice, decision-making is based either on intuition, impulsive impulse, or judgments based on personal experience, knowledge, and competencies. Intuitive solutions are not burdened with a conscious weighing of the pros and cons of each alternative and do not need a rational understanding of the situation (McAuliffe & Sudbery, 2005). Even though intuition constantly accompanies the manager’s activities, rationality is the primary factor in solving the problem. Hence, this paper aims to investigate an inclusive model of ethical decision-making and reveal its influence on the working environment.

The inclusive model of decision-making was elaborated on the basis of numerous principles in such fields as healthcare, psychology, social work, legal practice, and others. It was first published by Chenoweth and McAuliffe (McAuliffe & Sudbery, 2005). It is built upon several essential dimensions responsible for the decision-making process and ensuring a safe environment for every employee. These dimensions are accountability, consultation, cultural sensitivity, and critical reflection.

The first element is explained as the responsibility of “being called on to give an account of what one has done or not done” (Banks, 2004, p. 150). It is usually linked to blame because managers should be careful while making choices since unpredictable results may be. As an essential platform for an Inclusive Model of Ethical Decision-making, accountability focuses on the employee’s ability to formulate and justify the decisions made, considering the broader social context in which they work. This platform is tightly linked to critical reflection, which encourages managers to open up the decision-making process to test themselves and others in a way that improves organizational status (Banks & Nøhr, 2012). If this step is followed, workers can realize the structure of their values and their impact on their decisions.

The ethics of professional social work can be defined as the theory (teaching) of professional morality of specialists in the field of social work. It includes a system of ideals and values, ethical principles and norms of behavior, ideas about what is due, and requirements for the personality of a specialist (McAuliffe & Sudbery, 2005). These components of the ethics of professional social work reflect its essence and specifics as a profession and provide relationships between people that develop in the work process, which follow from the content of their professional activities.

The third component of the model, cultural sensitivity, is of vital importance since the modern world demands us to be tolerant and respectful of any culture. Culturally insensitive practices often lead to destructive consequences and leave employees susceptible to discrimination if managers do not take action against such cases (McAuliffe & Chenoweth, 2008). The final platform of the foundation is consultation, which consists in making reasonable use of the wisdom and advice of others. It also requires participation in discussions with others that can help the practitioner maintain essential values in the interests of honesty and prudence (McAuliffe & Chenoweth, 2008). However, this element is customarily disregarded when it comes to making ethical decisions, and many practitioners silently bear a moral burden, fearing that colleagues will consider them unprofessional (McAuliffe & Sudbery, 2005). These four platforms are interconnected and interdependent since, together, they aim to improve the decision-making process. When passing through the stages of the inclusive model, these virtual platforms should remain at the center of attention at each stage.

The model also includes five steps to solve the organizational problem and come up with a proper decision. The case study chosen for the assessment refers to the dilemmas in working with a gypsy family. Following the inclusive model of ethical decision-making steps, it is primarily vital to define the social problem (McAuliffe & Chenoweth, 2008). The ethical dilemma in the selected situation is that Miguel, the educator, struggles to prevent 15-year-old Gloria from marriage or to respect the gypsy marriage traditions of nomadic people. Despite the fact that now, Gypsies almost do not wander and lead a sedentary lifestyle, they keep their traditions and customs sacred. It is accepted that early marriages in the gypsy traditions are not prohibited, but they are not mandatory either. This practice is common, but not all representatives of the people follow the customs. Its meaning is to preserve the purity of the bride and groom by arranging the marriage as early as possible.

Meanwhile, Miguel attempts to preserve the low school dropout statistics to ensure as many kids as possible receive a proper education. On the one hand, Miguel has a good relationship with the community leader and does not want to disrespect his culture. On the other hand, he wants to satisfy Gloria’s needs and her desire to stay in school because he knows how important it is for her.

Since the ethical dilemma was determined, it is necessary to follow the second step called mapping legitimacy. This stage determines the nature of the relationships between the participants at various levels of interpersonal, family, and social systems (McAuliffe & Chenoweth, 2008). It is crucial to define relevant for dilemma-solving participants since irrelevant stakeholders may worsen the outcomes. In Miguel and Gloria’s case, the primary relationship to be viewed is between the educator himself and Gloria’s father because he is responsible for his underage daughter.

The problem needs to be directly discussed with the client, Gloria’s father, for several reasons. First, the dropout Gloria is facing can have a negative impact on her further education and career. As Gloria’s intentions align with Miguel’s, her father needs to be convinced that school is of primary importance for the girl, while the marriage can be delayed. Second, according to gypsy tradition, a husband is the head of the family, and a wife is the keeper of the hearth, which means they barely receive any education or want to work. Among the gypsies, a girl aged 19-20 years is already considered an old maid (Williams, 2020). It is already challenging for her to get married, no matter how beautiful she is. By the age of 30, she loses her fertility, which means that she will not produce offspring (Williams, 2020). Hence, Gloria’s dad needs to understand that the modern world requires people to acquire new knowledge regardless of the culture they belong to.

The third step of the model presumes to gather information. According to McAuliffe and Chenoweth (2008), “the difference with ethical decision making is that the information to be gathered is more specific to practice standards, codes of conduct, protocols, legal precedent, and organizational policies” (p. 44). It means that the data collection should be conducted thoroughly, considering both sides’ perspectives on the matter (McAuliffe & Chenoweth, 2008). For instance, Miguel should find out more about gypsy traditions. He may research the existing literature regarding their customs and determine if there are any deviations if they do not stick to the specific rites such as getting married. On the other hand, the educator should abide by the code of ethics of social workers to avoid encountering any ethical issues.

Collecting relevant information and disposing of unnecessary facts is crucial to establishing a plan of action. It would also help discard misleading data that could contribute to destructive results in further plan implementation. One of the fundamental principles of social workers is the principle of “do no harm,” which involves working for the well-being of a person and preventing any ill-treatment of them (Beckett et al., 2017). Respect for the client’s right to decide is a manifestation of respect and observance of their rights (Beckett et al., 2017). A social worker cannot assist a client without their consent to their action plan.

Hence, when solving Gloria’s situation, it is vital to consider the background of her family. All the specific features of her culture and family should be taken into account when making a decision on providing her with social assistance. However, it is also indispensable to rely upon the psychological perspective regarding child development. At the age of 15, the ten lays the foundations of conscious behavior; there is a general orientation in the formation of moral ideas and social attitudes (Newman & Newman, 2020). Features of the development of cognitive abilities of a teenager often cause difficulties in school education: poor academic performance and inappropriate behavior. The success of learning largely depends on the motivation of learning and on the personal meaning that learning has for a teenager (Newman & Newman, 2020). The primary condition for any training is the desire to gain knowledge and measure yourself and the student. Considering Gloria’s dive to study and acquire knowledge, I believe Miguel should explain its fundamentality to her parents, suggesting the psychological view on the teenager’s development.

In addition, a teenager has a strong need to communicate with their peers. The leading motive of such behavior is the desire to find their place among their peers. If Gloria is deprived of this opportunity, she is likely to lack social skills. Moreover, if she is getting married and gives birth at such an early age, it may result in trauma since children are not adapted to such events due to the relative instability of their psyche. Early pregnancy among adolescents has severe consequences for the health of adolescent mothers and their children (Branje, 2018). What is more, childbirth during adolescence often forces girls to drop out of school, which could be the case for Gloria.

The final step relates to the evaluation and critical analysis. Here Miguel should appraise several alternatives and suggest them to Gloria and her father to decide which suits them better. There is no need to press clients when they choose, but Miguel should be persuasive to sustain his project’s goals (Beckett et al., 2017). Thus, when they together evaluate the probable outcomes, the solution can be found.

Given similar circumstances in Australia, I would primarily investigate gypsy traditions within the scope of my country. Due to the fact that gypsies share identical values across the world, their mindsets become adjusted to their location as geographical context influences the central part of any person’s life. Hence, if I ever encountered such a situation, I would conduct research on the psychology of 15-year-old teens, determine the positive and negative consequences of a school dropout, and discuss this information with both Gloria and her father. Undoubtedly, it is necessary to explain that adolescence is a time of active personality formation, refracting social experience through the individual’s functional activity to transform one’s personality. As a result, I would persuade Gloria’s father that a girl needs education before entering adult life.

On the other hand, being a social worker demands utter respect for a client. They act in the interests of the person who has applied to them for help, often doing more than is prescribed by standards. It presumes that clients make their own decision based on the alternative proposed by social workers (Beckett et al., 2017). Therefore, I would suggest two ways for Gloria’s situation development to her father and let him choose since he is the official guardian of an underage child. Taking into consideration customers’ needs is vital to providing desired outcomes.

In summary, the inclusive model of ethical decision-making helps solve social dilemmas. It is an efficient means of establishing the root of the problem and the resolutions, and most importantly, it relies on ethics. Gloria’s case proves that cultural context is the primary factor affecting the development of the further flow of the situation. Despite the traditions preserved within a specific society, there are other perspectives on the matter, such as the psychological one, which should also be considered.

Banks, S. (2004). Ethics, accountability and the social professions . Palgrave Macmillan.

Banks, S., & Nøhr, K. (Eds.). (2012) Practising social work ethics around the world: Cases and commentaries . Routledge.

Beckett, C., Maynard, A., & Jordan, P. (2017). Values and ethics in social work. SAGE Publications.

Branje, S. (2018). Development of parent-adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change . Child Development Perspectives , 1-6.

McAuliffe, D., & Chenoweth, L. (2008). Leave no stone unturned: The inclusive model of ethical decision making. Ethics and Social Welfare, 2 (1), 38-49.

McAuliffe, D.,& Sudbery, J. (2005). Who do I tell? Support and consultation in cases of ethical conflict. Journal of Social Work, 5 (1), 21-43.

Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2020). Theories of adolescent development. Elsevier Science.

Williams, V. R. (2020) . Indigenous peoples: An encyclopedia of culture, history, and threats to survival . ABC-CLIO.

- Laban Erapu's Views on Naipaul's "Miguel Street"

- "Gloria" by Vivaldi and "O Magnum Mysterium" by Tomas Luis De Victoria

- Analysis of the Statement by Gloria Anzaldua

- Self-Determination and Ethical Dilemma of Assisted Suicide

- Ethical Considerations That Determine People’s Choices in Eating Meat

- Ethical Issues in “Prison Experiments” Video

- Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity

- Mississippi Code of Ethics in Connection to Athletics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, November 8). Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-of-decision-making-in-social-work/

"Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work." IvyPanda , 8 Nov. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-of-decision-making-in-social-work/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work'. 8 November.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work." November 8, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-of-decision-making-in-social-work/.

1. IvyPanda . "Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work." November 8, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-of-decision-making-in-social-work/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Ethics of Decision-Making in Social Work." November 8, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-of-decision-making-in-social-work/.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Social Work

- About the British Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, the aims and scope of safeguarding adults’ services, the crpd and supported decision-making, supporting people living with dementia to take part in safeguarding decisions in england, case law references.

- < Previous

Safeguarding People Living with Dementia: How Social Workers Can Use Supported Decision-Making Strategies to Support the Human Rights of Individuals during Adult Safeguarding Enquiries

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jeremy Dixon, Sarah Donnelly, Jim Campbell, Judy Laing, Safeguarding People Living with Dementia: How Social Workers Can Use Supported Decision-Making Strategies to Support the Human Rights of Individuals during Adult Safeguarding Enquiries, The British Journal of Social Work , Volume 52, Issue 3, April 2022, Pages 1307–1324, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab119

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Dementia may make adults more susceptible to abuse and neglect and such mistreatment is recognised as a human rights violation. This article focusses on how the rights of people living with dementia might be protected through the use of supported decision-making within safeguarding work. The article begins by reviewing the aims and scope of adult safeguarding services. It then describes how the concept of ‘legal capacity’ is set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and how this differs from the concept of ‘mental capacity’ in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. Focussing on practice in England, it is argued that tensions between the CRPD and domestic law exist, but these can be brought into closer alignment by finding ways to maximise supported decision-making within existing legal and policy frameworks. The article concludes with suggested practice strategies which involve: (i) providing clear and accessible information about safeguarding; (ii) thinking about the location of safeguarding meetings; (iii) building relationships with people living with dementia; (iv) using flexible timescales; (v) tailoring information to meet the needs of people living with dementia and (v) respecting the person’s will and preferences in emergency situations.

Dementia is an umbrella term used to refer to a range of conditions leading to impairments in memory, language and sensory awareness. Whilst the causes of abuse and neglect are complex, research shows that older adults with dementia experience higher rates than those without dementia ( Fang and Yan, 2018 ). Such mistreatment is recognised as a human rights violation by the World Health Organisation ( WHO, 2016 ). Speaking at the Global Action Against Dementia conference in 2015 the UN Independent Expert on the Enjoyment of all Human Rights by Older People stated that:

the rights and needs of person’s with dementia have been given low priority in the national and global agenda. In particular, with the progression of the disease, as their autonomy decreases, persons with dementia tend to be isolated, excluded and subject to abuse and violence (cited in Cahill, 2018 , p. 3).

The WHO Call for Action and Global Action Plan, which was adopted in May 2017, called on countries to: ‘promote mechanisms to monitor the protection of the human rights, wishes and preferences of people with dementia and the implementation of relevant legislation, in line with the objectives of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and other international and regional human rights instruments’ ( WHO, 2016 , para 20). These aims align with the principles of social work, which is committed to advocating and upholding the human rights of clients and communities ( International Federation of Social Workers, 2014 ).

Supported decision-making is viewed as a key mechanism for delivering the rights of persons with disabilities under the CRPD. This model is founded in Article 12.3 of the CRPD and is predicated on the principle that, ‘all people are autonomous beings who develop and maintain capacity as they engage in the process of their own decision-making even if at some level support is needed’ ( Devi et al. , 2011 , p. 254). The support model is in contrast to substituted decision-making regimes, which are systems where, ‘(i) legal capacity [the formal ability to hold and to exercise rights and duties] is removed from a person, even if this is in respect to a single decision; (ii) a substitute decision-maker can be appointed by someone other than the person concerned, and this can be done against his or her will and (iii) any decision made by a substitute decision-maker is based on what is believed to be in the objective best interests of the person concerned, as opposed to being based on their will and preferences’ ( Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2014 , para 27). Supported decision-making acts in contrast to substituted decision-making through providing a ‘conceptual and practical bridge’ ( Gooding, 2013 , p. 432), which seeks to respect the individual’s will and preference, whilst viewing decision-making as an interdependent process ( Sinclair et al. , 2019 ). It allows for consideration of a disabled person’s decision-making ability, the environmental demands for decision-making and the support that is required to enable the person to decide ( Shogren and Wehmeyer, 2015 ). The approach is informed by the social model of disability, which highlights how barriers (physical, attitudinal and structural) perpetrate disadvantage for disabled people; and feminist critiques of individualism, which explore how autonomy develops within the context of social relationships ( Donnelly, 2019 ).

Attention has been paid to the ways in which the CRPD should be applied in situations where people are living with dementia ( Keeling, 2016 ; Sinclair et al. , 2019 ). However, debates remain as to how supported decision-making should be interpreted and applied in practice. Research indicates that people living with dementia are often positive about supported decision-making ( Sinclair et al. , 2019 ) although there are complex practice issues to be dealt with, particularly when the person supporting an individual may be a source of risk. Social workers are often involved in such situations and yet little analysis has been carried out on this subject, an issue that this article seeks to address.

Concerns about adult abuse and neglect have led to the development of adult protection systems, most notably in the UK, the USA, Canada and Australia; initially developed as a response to concerns about elder abuse in the 1980s and 1990s. A key policy document, the Toronto Declaration on the Global Protection of Elder Abuse highlighted the need for a universal human rights framework for older adults ( WHO, 2002 ). It asserted that legal frameworks to address elder abuse were often missing, meaning that abuse might be recognised, but not adequately dealt with. Such arguments influenced responses by governments enabling the traditional focus on elder abuse to be broadened, to concepts of ‘vulnerable adults’ or ‘adults at risk’ more generally ( Donnelly et al. , 2017 ).

To some degree UK policy and law had begun this process earlier through reference to the Human Rights Act 1998 . For example, the No Secrets guidance on adult abuse in England referred to abuse as, ‘a violation of an individual’s human and civil rights by any other person or persons’ ( DH, 2000 , para 2.5). There remain, however, contested ideas on definitions. The term ‘adult safeguarding’ has not been defined internationally and there are differences in definitional thresholds ( Mackay, 2018 ). Thus, all four countries in the UK explicitly state that risk of (as well as actual) harm, abuse or neglect are grounds for making an enquiry. The terminology thereafter varies: the term abuse or neglect is used in Wales and England; in Northern Ireland it is abuse, exploitation or neglect; and Scotland has the most expansive term of harm on its own. Whilst safeguarding law and policies vary across national systems, social workers tend to play a lead role in England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Novia Scotia and British Colombia ( Donnelly et al. , 2017 ). The rationale is that social workers possess particular skills in assessment, working across professional boundaries and in enabling individuals through self-directed support. These systems have identified that they value social work knowledge. For example, The Care and Support Statutory Guidance in England states that social workers are likely to be the most appropriate professionals to make enquiries about abuse or neglect within families or informal relationships ( Department of Health and Social Care, 2020 , para 14.8) and highlights the importance of the principal social work role ( Whittington, 2016 ). Nonetheless, little has been done to consider how social workers might explicitly protect the human rights of people living with dementia within safeguarding practice.

The CRPD (Article 1) states that, ‘Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments’, which may hinder their participation in society. This definition clearly places people living with dementia within its remit, making them subject to its rights and protections. The CRPD marks a paradigm shift for the rights of persons with disabilities as it adopts a social model of disability (identifying the need for society to adapt to the needs of the disabled person), in contrast to a medical model (focussing on cure) or a social welfare model (focussing on a person’s limitations) ( Bartlett, 2012 ). The CRPD states that people with disabilities should be free from exploitation, violence and abuse and that state parties should take, ‘all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, educational and other measures to protect persons with disabilities, both within and outside the home’ (Article 16.1). Furthermore, those with disabilities are given positive rights and entitlements (such as the right to provision of services) by the CRPD, in contrast to the European Convention of Human Rights, which protects individuals’ negative rights (e.g. the right to be free from undue interference or abuse from others).

National safeguarding legislation has increasingly identified the need to involve those experiencing abuse or neglect in the process ( Donnelly et al. , 2017 ), making the issue of decision-making of central importance. For example, the Care Act (2014) put safeguarding in England on a statutory footing. It is therefore essential to consider how autonomy and decision-making are conceptualised within the CRPD and how this should inform decision-making within national safeguarding practice. Protecting a person’s legal capacity and promoting their involvement in decision-making are central to the CRPD. Legal capacity can be understood as a person’s ability to hold rights, and to exercise them on an equal basis with others ( Bach and Kerzner, 2010 ). It differs from the concept of mental capacity, which is concerned with the decision-making skills and competencies of a person, which may differ between individuals. So, from a safeguarding perspective, people living with dementia should have rights to be engaged and participate in decision-making in the safeguarding process and should also receive support to exercise these rights. Article 12 of the CRPD states that people with disabilities should be afforded legal capacity on an equal footing to others and that States should take measures ‘to provide access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require’ (Article 12.3). In English law, there is also recognition that people may have mental capacity but remain vulnerable to abuse due to manipulation or undue influence from others. In these cases, the court may exercise its ‘inherent jurisdiction’ to intervene in a way that is compliant with the CRPD ( Series, 2015 ) (although it is beyond the scope of our article to consider the complexities of inherent jurisdiction here). Nonetheless, the CRPD Committee’s Interpretation of Article 12 identifies that people with disabilities cannot be viewed as having exercised their legal capacity unless they have been supported to decide for themselves. This view is reflected in the statement that:

State Parties’ obligation to replace substitute decision-making regimes by supported decision-making requires both the abolition of substitute decision-making regimes and the development of supported decision-making alternatives. (United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2014 , para 28)

However, the UN Committee’s interpretation of Article 12 has been viewed as problematic by some as it states that substituted decision-making mechanisms are outlawed by the CRPD. The removal of substituted decision-making in all circumstances may cause a range of practical problems in adult safeguarding where an individual is unable to decide for themselves (as may be the case when an individual is living with advanced dementia and experiencing abuse or neglect) ( Freeman et al. , 2015 ; Gooding, 2015 ). No state who is a signatory to the CRPD has followed this binary approach to decision-making in the field of capacity laws, partly because of possible, perverse outcomes that might follow. For example, the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (MCA) in England and Wales defines mental capacity in relation to decision-making and states that individuals should be assumed to have mental capacity, unless it can be established otherwise on the balance of probabilities. The MCA states that consideration of capacity must be decision and time specific. In the context of an adult safeguarding case, this means that once it has been established by the decision-maker that the person lacks mental capacity, section 4 of the MCA allows for a form of substituted decision-making by allowing the decision-maker to act in the person’s ‘best interests’. However, this places the MCA in tension with the CRPD due to its focus on decision-making capacity rather than legal capacity ( Martin et al. , 2016 ).

Current State responses to the CRPD tend to involve a hybrid mix of safeguards and processes that professionals are expected to adhere to in order to support the exercise of a person’s legal capacity ( Davidson et al. , 2016 ). In doing so, in a more limited way than the CRPD strives for, improved approaches to supported decision-making can go some way to protect the legal rights of persons living with dementia. Several arguments are presented for such approaches. First, people living with dementia will have formed a range of moral, political, social and other views before developing the condition ( Donnelly, 2019 ). The use of mental capacity laws allows these former wishes and values to be used in preference to their current views (which may have altered radically since the onset of dementia). For example, in Briggs v Briggs [2016] Charles J. gave primacy to previously expressed wishes, in line with the ‘enabling’ ethos of the MCA deciding that, ‘an earlier self can bind a future and different self’ (para 53). As noted by Ruck Keene et al. (2017 , p. 135), this can be promoted when the previously expressed and current wishes are consistent, either because they match (see Westminster City Council v Sykes [2014] ) or because the person who lacks capacity is no longer able to express their wishes (see PS v LP [2013] ). However, it becomes more problematic when there is a clash between a person’s past and present wishes. Domestic case law is inconsistent and the CRPD is silent on the primacy point. Ruck Keene et al. (2017 , p. 138) suggest that the CRPD Committee’s interpretation of Article 12, ‘drives inexorably towards prioritisation at all points of a person’s immediately identifiable wishes and feelings’. But this approach could be problematic in a safeguarding context for persons with dementia who might express a current preference, which puts them at risk.

Second, older adults experience higher levels of abuse and neglect than other disabled groups and tend to afford greater weight to professional review and protection ( Bach and Kerzner, 2010 ; Donnelly, 2019 ). This indicates the need for legal frameworks which balance notions of empowerment and safeguarding. Such circumstances have led some to argue that supported decision-making should be the preferred option to accommodate a person’s rights under the CRPD, but that mental capacity laws are required where individuals with conditions, such as dementia may place themselves at serious risk and where there is danger in delay ( Freeman et al. , 2015 ).

Social workers are required to work within existing legal frameworks, despite the earlier stated tensions that exist between the interpretation of legal capacity identified by the CRPD and domestic laws. It is crucial that they find ways to maximise the rights of individuals to exercise their legal capacity whilst ensuring compliance with these domestic laws.

The following section explores how supported decision-making can be facilitated in England, one of four jurisdictions in the UK. The population of England was 55.6 million in 2018 ( Office for National Statistics, 2018 ). The most recent estimate of people with dementia, in 2013, found that 685,812 people were living with dementia ( Prince et al. , 2014 ). As in some other jurisdictions, social workers play a lead role in safeguarding and substitute decision-making processes, using a range of laws and policies, now described and discussed.

The legal and policy context for safeguarding in England

In England, the Care Act, 2014 (CA) is the key legislation for safeguarding. The Care and Support Statutory Guidance describes this as a process of, ‘Protecting an adult’s right to live in safety, free from abuse and neglect’ (para 14.7). In cases where a safeguarding referral for a person living with dementia is made, practitioners must consider their duties under section 42(1) of the CA which requires the Local Authority to consider whether there is reasonable cause to suspect that an adult:

Has care and support needs;

is experiencing, or is at risk of abuse and neglect; and

as a result of their needs is unable to protect themselves from the abuse or neglect or risk of it.

This process may not be linear and actions to safeguard a person may take place as part of the section 42(1) process or during a general assessment of need ( LGA/ADASS, 2019a ). Safeguarding decisions must be focussed on the principles inherent within the CA, notably the duty to promote well-being under section 1, and should adopt a flexible approach focussing on what matters to the individual. Decisions must also be grounded in the six safeguarding principles contained in the Care and Support Statutory Guidance (empowerment, prevention, proportionality, protection, partnership and accountability). Workers need also to consider how abuse can be prevented (Care and Support Statutory Guidance, para 2.1) and should draw on the Making Safeguarding Personal approach. This is a sector-led initiative supported by the Local Government Association, the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services and other bodies. It promotes a personalised approach, where adults at the centre of the safeguarding process are asked what their preferred outcomes are. A number of studies suggest that these initiatives can promote increased confidence amongst staff when involving service users in decision-making ( Cooper, 2015 ; Butler and Manthorpe, 2016 ). The principles of the MCA must also inform any safeguarding interventions (see further below).

Tensions between English law and the CRPD

The CRPD is an international treaty and therefore does not have the same status and enforceability as domestic law. Although it is not directly legally binding on the UK, it is nevertheless of persuasive authority. The Court of Appeal has affirmed the influence of the CRPD ( Burnip v Birmingham City Council and Another [2012] ), and there is evidence that CRPD principles are informing the jurisprudence of the higher courts, for example, in relation to decisions about the management of a person’s property and deprivations of liberty ( LB Haringey v CM [2014] ; P ( by his litigation friend the Official Solicitor ) v Cheshire West and Chester Council & Anor [2014]). However, judges have also urged caution when considering how the CRPD should shape domestic law. For example, Hayden J. noted that, whilst courts should seek to interpret and apply national laws in line with international obligations, ‘the court cannot by a process of statutory construction simply ignore or rewrite the clear provisions of the MCA [Mental Capacity Act]’ ( Lawson, Mottram and Hopton, RE ( appointment of personal welfare deputies [2019]) ). This makes it clear that practitioners must follow domestic law and cannot use the CRPD to circumvent it.

Despite the disparities between Article 12 and the substitute decision-making regime of the MCA, the MCA nevertheless has an empowering ethos and includes several mechanisms which are designed to promote autonomy and support the decision-making ability of individuals. Foremost, section 1(2) of the MCA states that individuals are assumed to have mental capacity, unless it can be established otherwise, and that they should be supported, as far as possible, to make their own decisions. The MCA (section 1, statutory principle 2) and Code of Practice ( Department of Constitutional Affairs, 2007 , Chapter 3) make clear that, before deciding that someone lacks capacity, practitioners should take practical steps to help individuals to decide for themselves, including providing relevant information; communicating in an appropriate way and putting the person at ease.

The best interests checklist in section 4 includes a list of factors for the substitute decision-maker to consider. The list expressly includes the person’s wishes and feelings. Whilst they are not determinative, the court has made it clear that they must be central to the decision-making process. For example, in Wye Valley NHS Trust v Mr B [2015] the Court of Protection stated that it may in some circumstances support a person’s incompetent wishes and feelings. There is a growing evidence in the case law of the court’s willingness to engage with ‘the person and their identity’. As Series (2014) has argued, by prioritising this subjective approach to discerning best interests, the MCA can be applied in ways, which accord with the CRPD’s approach. Sections 24–26 of the MCA make provision for advance decision-making, which allows a person with mental capacity to refuse specific treatments in the future, should they lose capacity. This is regarded by the Court of Protection as a key mechanism for promoting a person’s ‘capacity to shape and control’ decisions affecting their life ( Barnsley Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust v MSP [2020]). Sections 9–14 of the MCA provide further mechanisms through which people can take out a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). It is a legal document stating who an individual would like to manage their property and finances or health and welfare should they lose mental capacity to make such decisions. Whilst LPAs can be viewed as problematic (because they allow for decision-making on behalf of the person), they can be made to work in a CRPD context as long as the LPA holder focuses on the subjective views/wishes, etc. of the individual (rather than objective criteria) in making decisions ( Series, 2014 ).

Supported decision-making with people living with dementia in practice

Safeguarding decisions may focus on a range of complex areas, including domestic abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse, discrimination or neglect. Dementia may affect a person’s ability to make decisions about abuse or neglect and this generally becomes more severe over time ( Fetherstonhaugh et al. , 2013 ). Nonetheless, a person’s ability to decide can be enhanced through support by professionals and carers; particularly where the dementia is mild or moderate. At a practical level, supported decision-making focuses on the environmental demands for decision-making (such as consideration for the procedure in question, the physical space that the person is in and the relationship between the individual and the decision-maker). It also focuses on the support that is required to enable the person to decide ( Shogren and Wehmeyer, 2015 ). Currently, there are no empirically tested decision tools that have been designed to help people living with dementia to engage in safeguarding ( Wied et al. , 2019 ). However, practitioners can design strategies, based on the principles of supported decision-making, which tailor information to the needs of people with dementia and seek to involve them as much as possible in the decision-making process. In the following section, we consider how such strategies may be used, drawing on the research evidence.

In order for safeguarding to be effective, people living with dementia need to be clear what safeguarding means. This is important as the first principle of safeguarding is empowerment (Department of Health and Social Care, 2020); meaning that adults should be supported and encouraged to make their own decisions with informed consent. Such consent can only be achieved if the person with dementia is clear about the enquiries which may be made and what their options are. The MCA Code of Practice places emphasis on providing information to the person, stating that it should be tailored to their needs and ‘in the easiest and most appropriate form’ ( DCA, 2007 , para 3.8). This is crucial because the literature suggests that giving people with mental impairments excessive information is often challenging because of problems of cognitive retention ( Wied et al , 2019 ). Local Authorities must therefore consider the most effective strategies for informing the public about safeguarding. Whilst the sections of the CA associated with safeguarding (sections 42–47) have been in force since 2015, levels of public awareness about safeguarding remain unclear. To ensure that people with dementia have adequate and appropriate information to make a decision, Local Authorities need to provide accessible and clear information, setting out the types of abuse, which may be experienced and how people can report it. This can be achieved by using clear and simple language with a focus on consistency of expression, as well as pictures or drawings ( Wied et al. , 2019 ). When explaining the safeguarding process at an individual level, practitioners may draw on public information as communication aids, but need to explain to individuals how it applies to them. Research indicates that people living with dementia are better able to engage where workers adopt a spirit of collaboration, highlight what they are expecting of them and work with them to define what it is they need to decide on ( Groen-van de Ven et al. , 2017 ). Practitioners should therefore explain the nature of the safeguarding concerns from the outset, identifying first how it has been raised and then what information is required.

Within any supported decision-making process, consideration should also be given to the location of the meeting. The MCA Code of Practice advises that practitioners should choose a quiet place where discussions cannot be easily interrupted ( DCA, 2007 , para 3.13). Current research on this issue is limited but indicates that people living with dementia find it harder to make decisions in noisy or cluttered environments ( Wied et al. , 2019 ). Interviewing a person in a quiet room rather than a busy area is likely to improve communication. Efforts should also be made to limit the number of people taking part in an interview, particularly if they are unfamiliar to the person (Fetherstonhaugh et al. , 2016).

Supported decision-making relies on building a relationship with the person. This is something that is currently overlooked in the MCA Code of Practice, which focusses more broadly on providing information and putting the person at ease ( DCA, 2007 , paras 3.10–3.15). In order to build an effective relationship, several factors should be borne in mind. A recent study found that persons with dementia prefer to be supported by people that they know well ( Sinclair et al. , 2019 ). Where family members are not suspected of abuse or neglect, then social workers and other professionals should engage with them so that they can provide advice on the person’s preferences and how best to involve them in decisions. Whilst people living with dementia may be fully autonomous, they may also engage in shared decision-making with carers or may delegate decision-making ( Smebye et al. , 2012 ). When people with dementia consent to these arrangements, they should be considered as ways of facilitating decision-making. In cases where it is not possible to work with family members or carers and communication is challenging, advocacy under section 68 of the CA (2014) should be considered, although this can only be provided if the conditions of the CA are met. Representation by an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) can also be considered where safeguarding issues arise, even where the person has friends or family (s. 4, Mental Capacity Act, 2005 . It should, however, be noted that advocacy provision across England is patchy, with most Local Authorities failing to meet the spending recommendations prescribed by the Local Government Association, making person-centred practices a challenge ( Dixon et al. , 2020 ). When building relationships with the person, practitioners also need to assess their attitude to risk. Recent safeguarding guidance has placed an emphasis on positive risk-taking, in which individuals are enabled through a careful consideration of the risks in question ( LGA/ADASS, 2019b ). Nonetheless, research has found that people living with dementia and family carers often conceptualise risk in negative terms because of its emotive connotations ( Stevenson et al. , 2019 ). A way of dealing with this dilemma is to encourage people living with dementia to view risk in terms of ‘likelihood’ to enable positive risk-taking. Social workers should also be aware that people living with dementia may be concerned about the risks which social care services may pose to them. For example, lesbian women with dementia have been known to conceal their sexual identities because they fear discrimination by services ( Westwood, 2016 ). Social workers therefore need to consider the person’s personal and cultural needs. With lesbian and gay service users this may be achieved through taking account of the person’s sexual identity, making sure that it is explicitly acknowledged in safeguarding plans and through facilitating access to support networks where required.

Time is an important issue if people living with dementia are meaningfully to be engaged in decision-making. The MCA Code of Practice places emphasis on the timing of conversations, stating that decisions should not be rushed and that unnecessary time limits should be challenged where the decision is not urgent ( DCA, 2007 , para 3.14). This guidance is supported by research which has found that supported decision-making processes are more likely to be effective where a person living with dementia is given time to recognise the issues they face and consider the options to enable a final decision to be made ( Smebye et al. , 2012 ; Fetherstonhaugh et al. , 2013 ). Ideally, time should be ring-fenced, to enable an assessment of the person’s life story, and conducted at a pace that they feel comfortable with and at the time of day during which they function best. These recommendations are congruent with guidance by the Local Government sector ( LGA/ADASS, 2019a , b ), which has encouraged practitioners to view safeguarding as a series of conversations with the person, drawing on a strengths-based approach. There are possible organisational impediments to these aspirations where resources are limited. In some instances, however, local authorities have supported a flexible approach. For example, the London Safeguarding Adults Board (2019) states that a divergence from target timescales may be justified for a number of reasons including the need to provide supported decision-making. Nonetheless, there may be situations where immediate risks prevent engagement with the person over time, discussed in more detail, below.

Practitioners should design strategies that tailor information to the needs of people with dementia. As mentioned above, there are no empirically tested decision-tools to enable clients to engage in safeguarding ( Wied et al. , 2019 ). The MCA Code of Practice, however, provides guidance on what steps can be taken to tailor the information to the individual and ensure it is ‘relevant’, including not giving too much detail; providing a ‘broad simple explanation’ and outlining the risks, benefits and effects of the decision (2007; para 3.9). It has been found that strategies which build a relationship with the person through helping them to feel useful and productive are most effective ( Fetherstonhaugh et al. , 2013 ). At a practical level, this involves writing options down, to ensure the retention of information; the use of lists to explore options and using visual aids (such as pictures or photographs) to compensate for memory problems. Limiting decisions to two or three options to prevent the person experiencing ‘sensory overload’ has also been found to be important ( Smebye et al. , 2012 ; Fetherstonhaugh et al. , 2013 ). However, this option needs to be considered carefully. Not giving the full range of options may lead to over-simplifying or withholding important information. This is problematic from a legal perspective as it limits how informed the decision can be, thereby impacting on the person’s rights. When deciding how to proceed, workers need to consider the person’s individual preferences for decision-making as well as the potential consequences of the decision. Further sources of support from family/friends or professional advocacy services should be considered as a way of maintaining the person’s legal capacity, as recommended by the MCA Code of Practice ( DCA, 2007 , para 5.69).

Consideration needs to be given to principles of safeguarding where an urgent decision needs to be made. Whilst the MCA makes no explicit reference to safeguarding, it aims to balance an individual’s right to make decisions with ‘their right to be protected from harm if they lack capacity’ ( DCA, 2007 , para 1.4). Relying solely on the concept of mental capacity may not accord with the approach to legal capacity within the CRPD, but can be viewed as necessary in cases where a person with a mental health problem is at serious risk and there is danger in delaying decisions ( Freeman et al. , 2015 ). Whilst section 4 of the MCA allows for a best interests decision to be made, the person’s legal capacity can still be protected where workers are able to draw on advance decisions, designed to attend to previous choices made by the person ( Series, 2014 ; Keeling, 2016 ). In order to maximise legal capacity, these should be referred to first, although in practice their use is likely to be limited, as they focus on advance refusals of medical treatment. Where neither an advance decision, a LPA, or a court-appointed deputy exists, practitioners need to resort to a best-interests decision-making process in line with the MCA, although this should be viewed as a last resort after all other decision-making avenues have been explored. To maximise the person’s rights, all efforts should be made to consider the subjective wishes of the person within this process. In these circumstances, practitioners should endeavour to resume supported decision-making once the person is out of immediate danger.

Finally, it should be noted that there are some limits to the research evidence as it stands. Although the CRPD has led to an increased emphasis on supported decision-making, research on supported decision-making remains at an early stage, particularly with regards to dementia ( Wied, 2019 ). Whilst current research may inform practice, many of the studies focus on aspects of supported decision-making, such as user-involvement or participation, rather than on the supported decision-making process as a whole. It should also be noted that much of the existing evidence draws on qualitative research. Whilst such research has provided valuable insights, there is a need for studies that test the effectiveness of supported decision-making for people with different types of dementia. Such developments have the potential to lead to empirically tested decision-making tools with greater levels of validity.

Dementia leaves individuals more susceptible to abuse and neglect and action is required to address this. Social workers play a key role within adult safeguarding systems internationally and have an opportunity to address such abuse, yet little analysis has been carried out on this issue. The CRPD provides social workers with the opportunity to strengthen human rights protection for people with dementia, through the application of supported decision-making. This opportunity should be welcomed whilst recognising practice dilemmas, particularly in navigating the tensions between international frameworks and domestic law. In England, these are illustrated by the CRPD’s insistence on supported decision-making in Article 12, compared with the MCA which embraces a substitute decision-making model, albeit with elements of supported decision-making built into the process. Despite these tensions, steps can be taken to maximise the legal capacity of people living with dementia to promote the ethos of the CRPD through adopting a range of supported decision-making strategies.

Social workers must adhere to the provisions in the MCA and take appropriate steps to aid decision-making ‘before’ an assessment of mental capacity is made, in line with the guidance in the MCA Code of Practice. Additionally, key measures should also be taken to maximise supported decision-making. Local authorities should be required to provide clear and accessible information to the wider public and to people living with dementia, their family and carers. These should explain what safeguarding is, how the safeguarding process works and how to access it. It is imperative that social workers clearly explain to the person how the safeguarding concern has been raised, associated issues and what information they require. Drawing on the research evidence, it has been argued that key steps are involved in good quality safeguarding interventions that are service user focussed. For example, people living with dementia should be interviewed in quiet areas, with care being taken to minimise the number of attendant people in the room. Skills in building effective relationships are critical for the practitioner. People living with dementia prefer to be supported by people that they already know, although advocacy under the CA should be considered where this is not possible and advocacy under the MCA may be considered where the person lacks capacity. Social workers also should be mindful that people with dementia often frame notions of risk differently to that of professionals. This awareness and knowledge can help build on the preferences of the person. The importance of time is central to decision-making processes. Ideally it should be ring-fenced in order to learn about the person’s life story, and to enable assessments to be conducted at a pace that the person feels comfortable with, and at the time of day at which they function best. The use of visual aids, diagrams and lists have been shown to assist the person to retain information and make decisions. Consideration should also be given to limiting options to enhance comprehension. Where immediate risks prevent this, the person’s capacity should be protected through ascertaining wishes expressed in advance decisions or through an LPA, or court appointed deputy, where they exist.

Bach M. , Kerzner L. ( 2010 ) ‘A new paradigm for protecting autonomy and the right to legal capacity’, available online at: http://repositoriocdpd.net:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/449/L_BachM_NewParadigmAutonomy_2010.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed December 18, 2019).

Bartlett P. ( 2012 ) ‘ The United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and mental health law ’, The Modern Law Review , 75 ( 5 ), pp. 752 – 78 .

Google Scholar

Butler L. , Manthorpe J. ( 2016 ) ‘ Putting people at the centre: Facilitating making safeguarding personal approaches in the context of the Care Act 2014 ’, The Journal of Adult Protection , 18 ( 4 ), pp. 204 – 13 .

Cahill S. ( 2018 ) Dementia and Human Rights , Bristol , Policy Press .

Google Preview

Care Act ( 2014 ) London, The Stationery Office.

Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ( 2014 ) General Comment No. 1 (2014). Article 12: Equal Recognition before the Law , New York, NY, United Nations.

Cooper A. , Penhale B. , Cooper A. , Lawson J. , Lewis S. , Williams C. ( 2015 ) ‘ Making safeguarding personal: Learning and messages from the 2013/14 programme ’, The Journal of Adult Protection , 17 ( 3 ), pp. 153 – 65 .

Davidson G. , Brophy L. , Campbell J. , Farrell S. J. , Gooding P. , O'Brien A.-M. ( 2016 ) ‘ An international comparison of legal frameworks for supported and substitute decision-making in mental health services ’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry , 44 , 30 – 40 .

Department of Constitutional Affairs ( 2007 ) Mental Capacity Act 2005. Code of Practice , London, The Stationery Office.

Department of Health ( 2000 ) No Secrets: Guidance on Developing and Implementing Multi-agency Policies and Procedures to Protect Vulnerable Adults from Abuse , London, Department of Health.

Department of Health and Social Care ( 2000 ) ‘Care and support statutory guidance’, available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/care-act-statutory-guidance/care-and-support-statutory-guidance (accessed February 17, 2021).

Devi N. , Bickenbach J. , Stucki G. ( 2011 ) ‘ Moving towards substituted or supported decision-making?: Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ’, Alter , 5 ( 4 ), pp. 249 – 64 .

Dixon J. , Laing J. , Valentine C. ( 2020 ) ‘ A human rights approach to advocacy for people with dementia: A review of current provision in England and Wales ’, Dementia , 19 ( 2 ), pp. 221 – 36 .

Donnelly M. ( 2019 ) ‘ Deciding in dementia: The possibilities and limits of supported decision-making ’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry , 66 , 101466 .

Donnelly S. , O’Brien M. , Walsh J. , McInerney J. , Campbell J. , Kodate N. ( 2017 ) Adult Safeguarding Legislation and Policy Rapid Realist Literature Review , Dublin , University College Dublin .

Fang B. , Yan E. ( 2018 ) ‘ Abuse of older persons with dementia: A review of the literature ’, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse , 19 ( 2 ), pp. 127 – 47 .

Fetherstonhaugh D. , Tarzia L. , Nay R. ( 2013 ) ‘ Being central to decision making means I am still here!: The essence of decision making for people with dementia ’, Journal of Aging Studies , 27 ( 2 ), pp. 143 – 50 .

Freeman M. C. , Kolappa K. , de Almeida J. M. C. , Kleinman A. , Makhashvili N. , Phakathi S. , Saraceno B. , Thornicroft G. ( 2015 ) ‘ Reversing hard won victories in the name of human rights: A critique of the general comment on Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ’, The Lancet Psychiatry , 2 ( 9 ), pp. 844 – 50 .

Gooding P. ( 2015 ) ‘ Navigating the ‘flashing amber lights’ of the right to legal capacity in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Responding to major concerns ’, Human Rights Law Review , 15 ( 1 ), pp. 45 – 71 .

Gooding P. ( 2013 ) ‘ Supported decision-making: A rights-based disability concept and its implications for mental health law ’, Psychiatry Psychology and Law , 20 ( 3 ), pp. 431 – 51 .

Groen-van de Ven L. , Smits C. , Oldewarris K. , Span M. , Jukema J. , Eefsting J. , Vernooij-Dassen M. ( 2017 ) ‘ Decision trajectories in dementia care networks: Decisions and related key events ’, Research on Aging , 39 ( 9 ), pp. 1039 – 71 .

Human Rights Act ( 1998 ) London, The Stationery Office.

International Federation of Social Workers ( 2014 ) ‘Global definition of social work’, available online at: https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (accessed February 11, 2020).

Keeling A. ( 2016 ) ‘ Supported decision making: The rights of people with dementia ’, Nursing Standard , 30 ( 30 ), pp. 38 – 44 .

LGA/ADASS ( 2019a ) Making Decisions on the Duty to Carry Out Safeguarding Adults’ Enquiries. Suggested Framework to Support Practice, Reporting and Recording , London, Local Government Association.

LGA/ADASS ( 2019b ) Making Safeguarding Personal: A Toolkit for Responses , 4th edn, London, Local Government Association.

London Safeguarding Adults Board ( 2019 ) London Multi-Agency Safeguarding Policy & Procedures , London, London Safeguarding Adults Board.

Mackay K. ( 2018 ) ‘The UK policy context for safeguarding adults: Rights-based v Public protection?’, in MacIntyre G. , Stewart A. , McCusker P. (eds), Safeguarding Adults. Key Themes and Issues , London , Palgrave .

Martin W. , Michalowski S. , Stavert J. , Ward A. , Keene A. R. , Caughey C. , Hempsey A. , McGregor R. ( 2016 ) ‘The Essex Autonomy Project Three Jurisdictions Report: Towards compliance with CRPD Art. 12 in capacity/incapacity legislation across the UK . University of Essex, Essex Autonomy Project.

Mental Capacity Act ( 2005 ) London, The Stationery Office.

Office for National Statistics ( 2018 ) ‘Overview of the UK population’, available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/november2018 (accessed 20 February 2020).

Prince M. , Knapp M. , Guerchet M. , McCrone P. , Prina M. , Comas-Herrera A. , Wittenberg R. , Adelaja B. , Hu B. , King D. , Rehill A. ( 2014 ) Dementia UK: Update , London , Alzheimer’s Society .

Ruck Keene A. , Cooper R. , Hobbes T. ( 2017 ) ‘ When past and present wishes collide: The theory, the practice and the future ’, Elder Law Journal , 2 , pp. 132 – 40 .

Series L. ( 2015 ) ‘ Relationships, autonomy and legal capacity: Mental capacity and support paradigms ’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry , 40 , 80 – 91 .

Series L. ( 2014 ) ‘ Comparing old and new paradigms of legal capacity ’, Elder Law Journal , 2014 ( 1 ), pp. 62 – 70 .

Shogren K. A. , Wehmeyer M. L. ( 2015 ) ‘ A framework for research and intervention design in supported decision-making ’, Inclusion , 3 ( 1 ), pp. 17 – 23 .

Sinclair C. , Gersbach K. , Hogan M. , Blake M. , Bucks R. , Auret K. , Clayton J. , Stewart C. , Field S. , Radoslovich H. , Agar M. , Martini A. , Gresham M. , Williams K. , Kurrle S. ( 2019 ) ‘ A real bucket of worms: Views of people living with dementia and family members on supported decision-making ’, Journal of Bioethical Inquiry , 16 ( 4 ), pp. 587 – 608 .

Smebye K. L. , Kirkevold M. , Engedal K. ( 2012 ) ‘ How do persons with dementia participate in decision making related to health and daily care? A multi-case study ’, BMC Health Services Research , 12 ( 1 ), p. 241 .

Stevenson M. , Savage B. , Taylor B. J. ( 2019 ) ‘ Perception and communication of risk in decision making by persons with dementia ’, Dementia , 18 ( 3 ), pp. 1108 – 27 .

The Mental Capacity Act ( 2005 ) ( Independent Mental Capacity Act Advocates) (Expansion of role) regulations 2006 (SI 2006/2883) , London, The Stationery Office.

United Nations ( 2014 ) CRPD Committee, General Comment No 1: Equal recognition before the law (art. 12), 11 April 2014.

van de Ven L. G. , Smits C. , Elwyn G. , Span M. , Jukema J. , Eefsting J. , Vernooij-Dassen M. ( 2017 ) ‘ Recognizing decision needs: First step for collaborative deliberation in dementia care networks ’, Patient Education and Counselling , 100 ( 7 ), pp. 1329 – 37 .

Westwood S. ( 2016 ) ‘ Dementia, women and sexuality: How the intersection of ageing, gender and sexuality magnify dementia concerns among lesbian and bisexual women ’, Dementia , 15 ( 6 ), pp. 1494 – 514 .

Whittington C. ( 2016 ) ‘ The promised liberation of adult social work under England’s 2014 Care Act: Genuine prospect or false prospectus? ’, British Journal of Social Work , 46 ( 7 ), pp. 1942 – 61 .

Wied T. S. , Knebel M. , Tesky V. A. , Haberstroh J. ( 2019 ) ‘ The human right to make one’s own choices–Implications for supported decision-making in persons with dementia ’, European Psychologist , 24 ( 2 ), pp. 146 – 58 .

World Health Organization ( 2016 ) ‘Draft global action plan on the public health response to dementia’, Report by the Director-General, available online at: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB140/B140_28-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed December, 18 2019).

World Health Organisation ( 2002 ) The Toronto Declaration on the Global Protection of Elder Abuse , Geneva, World Health Organisation.

Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust v MSP ( 2020 ) EWCOP 26 (01 June 2020).

Briggs v Briggs ( 2016 ) EWCOP 53.

Burnip v Birmingham City Council and Another ( 2012 ) EWCA Civ 629.

Lawson, Mottram and Hopton, Re (appointment of personal welfare deputies) (Rev 1) ( 2019 ) EWCOP 22 (25 June 2019).

LB Haringey v CM ( 2014 ) EWCOP B23.

** P (by his litigation friend the Official Solicitor) v Cheshire West and Chester Council & Anor ( 2014 ).

PS v LP ( 2013 ) EWHC 1106 (COP).

Westminster City Council v Sykes ( 2014 ) EWHC B9 (COP).

Wye Valley NHS Trust v B (Rev 1) ( 2015 ) EWCOP 60 (28 September 2015).

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-263X

- Print ISSN 0045-3102

- Copyright © 2024 British Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

A GROUNDBREAKING PERSPECTIVE: JUDGE NEWSOM’S VISION FOR AI IN JUDICIAL DECISION-MAKING

- The Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.)

- June 7, 2024

- AI , Blog Articles , Case Law , In the News , LLM , Recent News , Topic

[Editor’s Note: EDRM is proud to publish the Hon. Ralph Artigliere’s (ret.) advocacy and analysis. The opinions and positions are Judge Artigliere’s (ret.) June 7, 2024 © Ralph Artigliere.]

Judges and lawyers received a significant gift last week when 11 th Circuit Judge Kevin C. Newsom penned a concurring opinion in a seemingly mundane insurance case involving a backyard in-ground trampoline. The concurring opinion, however, transcends its humble context, presenting a visionary outlook on a pivotal issue: the integration of advanced technology, particularly AI, into judicial workflows. As we navigate the current concerns surrounding AI—such as safety, hallucinations, and bias—this opinion prompts us to consider how we can harness machine intelligence to enhance judicial efficiency and efficacy.