Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Journal Proposal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Netiquette: ethic, education, and behavior on internet—a systematic literature review.

1. Introduction

2.1. search strategy, 2.2. inclosure criteria, 3.1. country, 3.4. methodological design, 3.5. main variables, 3.6. sample details, 3.7. measurement, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

| Ref. | Country | Date | Aim (s) | Methodology | Sample Details | Main Variables | Measurement | Main Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ ] | South Korea | 2014 | To study the relationship between levels of online activity and cyber-bullying behavior | Correlational. Random sampling. | 1200 teenagers | Bullying. Cyberbullying. Netiquette. Time online. Type of activities. Use of social networks. Communication with parents. | Face-to-face survey | Frequent users of the Internet and social networks are more likely to participate, become victims and witness cyber-bullying. | It is necessary to take preventive measures with teenagers to avoid cyberbullying. |

| [ ] | Denmark | 2017 | To analyze the rules underlying online mourning and commemoration practices on Facebook | Mixed. Qualitative, quantitative. | 166 Danish Facebook users | Attitude. Caring for the deceased. Caring for the bereaved. Taking care of friends. Legitimate practices. Objectionable practices. Mourning. Remembrance. Need for support. Questionable motives. Privacy. Publicity. | Ad-hoc questionnaire and coding with NVivo10 | Findings counter popular perceptions of Facebook as a desired online grief platform. | Despite not being the preferred medium, social media are a common means of communication with deep thematic. |

| [ ] | United Kingdom | 2010 | To examine whether married couples have similar ideas about network etiquette. | Quantitative. | 992 married couples | Netiquette. Use of the Internet. Specific activities. Supervision. | Adaptation of the eHarmonny survey. | A netiquette is developed and negotiated consciously or unconsciously in intimate relationships. | |

| [ ] | United States | 2012 | To present a methodological proposal based on the incorporation of laptops in the classroom. | Methodological article | 356 students | Use of laptop computer. Qualifications. Distraction | Ad-hoc survey | The majority of the students surveyed consider the accepted methodological policy to be positive. The proposal is based on placing the students who use the laptops in the first rows and there are point sanctions if there is a misuse or invented warning. | The incorporation of ICTs in the classroom can be functional and educational, but it is necessary to establish guidelines and consensus for students to understand in this way. |

| [ ] | Belgium | 2007 | To investigate whether the type of guideline provided has an effect on the quality of asynchronous group discussion or on participant assessment in the context of a medical course. | Experimental. Content analysis. | 112 graduate students in biomedical sciences. | Number of visits to the discussion forum. Number of times they read what has been published in the forum. Questions. Arguments. Unsubstantiated statements. | Discussion groups. | The group that received educational guidelines and advice on network etiquette had a higher quality of discussion and evaluation by the participants. There was no impact on the group that only received guidelines on network etiquette. | The more information students are provided with, the better they will understand digital formality. |

| [ ] | Jordan | 2017 | Study the presence of netiquette practices among university students. | Descriptive research. | 245 university students (125 classroom teachers and 120 special education teachers) | Gender. Specialization. Level of study. | Ad-hoc questionnaire. Likert type. | University students have a consensus on the general rules of netiquette, limited knowledge of them and different levels of implementation, Limited practice of netiquettes related to critical thinking skills. | There is a consensus on rules on the Internet, but it’s development and critical capacity needs to be further developed. |

| [ ] | Mexico | 2015 | To offer a panorama based on how moral practices develop ah now the rules of netiquette are applied in communities formed by secondary school students in their practices of virtual interaction. | Qualitative with a socio-historical perspective. Ethnography. | 34 students secondary education. | Categories. Moral practice. Communities of practice. Netiquette. | Open-ended questionnaire, field journal and an unstructured group interview. | Students consider morality and attachment to the family to be positive ideals that can be achieved, but exercise free behavior in virtual interactions. | There are discrepancies between knowing and doing on the Internet. Attention should be paid to ensuring that students apply what they know. |

| [ ] | England | 2011 | To examine the concept of agreement, how and why it is reached in an online interprofessional group. | Qualitative. Discourse analysis. | Ten interprofessional discussion group | Agreement. Disagreement. Online communication. | Discourse analysis. | Students tend to agree with each other’s comments rather than provoke disagreement. | In professional contexts, consensus is quickly reached. This is far from the reality in media such as social networks. |

| [ ] | Germany | 2018 | To examine the netiquette for Facebook contacts between students and their teachers. | Multiple closed answers. | 2849 participants (2550 students and 299 teachers) | Development of SL-Contacts. Netiquette and majority. | Ad-hoc questionnaire. | Most participants indicated that Facebook should be used only for private matters. The appropriateness of social networking contact between students and teachers depends on individual cases. | The use of social networks for educational purposes is not valued. It is recommended to focus on digital tools that are clearly intended for educational purposes. |

| Reference | Country | Date | Aim (s) | Methodology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ ] | United States | 2011 | Define the concept of a networked label and include guidelines to ensure that electronic communication takes place in an appropriate and polite manner. | Theoretical article | Different guidelines are set out to encourage written communication via e-mail. Some of them are: to use grammar and punctuation correctly, to avoid excessive use of abbreviations and acronyms, to use emoticons only, not to use the “high priority” option, to use a signature with personal contact information, to use spaces to avoid long messages, to avoid always using capital letters, to enter correctly and include a well-defined subject, to avoid sending sensitive information by e-mail, to avoid writing during other interactions. |

| [ ] | United States | 1997 | Attempt to collect and develop standard label guidelines in the context of a global Internet. | Literature review | The term netiquette has been described for e-mails and Internet use. A collection of authors is made on patterns of behavior on the Internet, specific suggestions, rules of network etiquette for advertising, control of undesirable network etiquette, the influence of Internet services, employees, and governments. |

| [ ] | United Kingdom | 1995 | Identify, present and digest some of the main patterns of netiquette | Literature review | The article presents different guidelines contained in different publications based on a total of 20: focus on objective, short and concise messages, edit your quotes, write grammatically correct, consider expressive typography, sign your messages, think where you want to go, mistakes can last forever, know the acronyms, don’t talk to a computer, don’t write in capital letters, try another kind of humor, think before you write, respect intellectual rights, be polite to newcomers, solve the necessary in private, be an ethical user, don’t damage the network, be proud of what you post, there is no rule 20. |

| [ ] | United States | 2004 | Present guidelines to alleviate problems in communication through email or phone calls. | Theoretical article | It presents 15 guidelines for personal writing of emails (always include a subject in the message, do not use capital letters, use appropriate language, use emoticons,...) and 11 guidelines for sending emails in distribution lists or groups (publish only what is relevant to the group, ask questions or comments without losing the focus of discussion, give feedback when you can, ask permission before sending large proposals to the organizer or moderator). |

| [ ] | United States/Canada | 2002 | Presenting some guidelines for e-mail etiquette. | Theoretical article | Different issues are presented in relation to e-mail: characteristics (backup, password protection, network and control systems, the threat of viruses, legal implications), risks (visual importance, avoid too much content, include emoticons, be careful with abbreviations), other risks (do not send negative information without notice, indicate response or delivery deadlines, use CC or Bcc) and practices to follow (be brief and concise, include a suitable subject, include a signature at the end, consider quoting a message or writing a new one, don’t send mass mailings, separate your personal mail from the professional one, keep your distribution lists updated, don’t open a mail if you don’t trust the source, don’t forget to say hello and goodbye. |

| [ ] | United States | 2018 | To provide the tools to avoid problems in electronic communication through email. | Theoretical article | It provides different guidelines regarding network behavior (basic rules such as using a professional email in a professional context, including subject, being concise, responding quickly, or forwarding emails only with permission). Also what not to do (offensive language, using capital letters, or avoiding emoticons in professional contexts), the negative impact (virtual empathy). It includes netiquette guidelines for an online learning environment, case studies, “the golden rules of netiquette” and the importance of positive communication. |

| [ ] | United States | 2011 | Provide a total of 50 rules for network etiquette for e-mail. Intended for employees in medical practice. | Theoretical article | It turns out to be a compilation of different guidelines, what to do and what not to do, regarding e-mail in the professional medical context. Some examples are: be concise, avoid long sentences, use templates, use a contact signature, protect the privacy of others, turn off the automatic reply, respect confidentiality, do not abuse the “high priority” option, do not write everything in capital letters, do not remember messages, do not ask for too much, do not use abbreviations, do not expect privacy when using a work email, etc. |

| [ ] | United States | 2000 | Guidelines for the use of appropriate distribution lists by nurses in their professional context | Theoretical article | Different ethical and practical issues for the use of distribution lists in the context of nursing are presented. Respect the ethical code (maintain privacy, provide information and sources for ethical decisions, incorporate legislative framework), avoid unethical messages (ask questions), consider Internet privacy, practical suggestions (do not leave your email account open and go away, sign your message, do not incorporate advertising, do not publish institutional messages without permission, do not write disrespectful or insensitive messages). |

| [ ] | United Kingdom | 2002 | Expose the importance of confidentiality among librarians and users in the face of the attraction of new technologies. | Theoretical article | Taking as a reference to a study by Loughborough University, which exposed the confidence of users and the poor preparation of librarians, a series of ethical reflections are raised. The development of specific users in libraries, individuality and privacy, access to the Internet and the individual, punishment, harassment, handling information, and making good policies. |

- Kapoor, K.K.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Patil, P.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Nerur, S. Advances in Social Media Research: Past, Present and Future. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018 , 20 , 531–538. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010 , 53 , 59–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shin, J.; Jian, L.; Driscoll, K.; Bar, F. The diffusion of misinformation on social media: Temporal pattern, message, and source. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018 , 83 , 278–287. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Carlson, M. Fake news as an informational moral panic: The symbolic deviancy of social media during the 2016 US presidential election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020 , 23 , 374–388. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chibuwe, A. Social Media and Elections in Zimbabwe: Twitter War between Pro-Zanu-PF and Pro-MDC-A Netizens. Communicatio 2020 , 1–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Carbonell, X.; Chamarro, A.; Oberst, U.; Rodrigo, B.; Prades, M. Problematic Use of the Internet and Smartphones in University Students: 2006–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018 , 15 , 475. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lin, T.T.C.; Kononova, A.; Chiang, Y.-H. Screen Adicction and Media Multitasking among American and Taiwanese Users. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2020 , 60 , 583–592. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaterlaus, J.M.; Aylward, A.; Tarabochia, D.; Martin, J.D. “A smartphone made my life easier”: An exploratory study on age of adolescent Smartphone acquisition and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021 , 114 , 106563. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Romero-Rodríguez, J.-M.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, C.; Ramos Navas-Parejo, M.; Marín-Marín, J.-A.; Gómez-García, G. Use of Instagram by Pre-Service Teacher Education: Smartphone Habits and Dependency Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 4097. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Do Nascimento, I.J.B.; Oliveira, J.A.Q.; Wolff, I.S.; Melo, L.D.R.; E Silva, M.V.R.S.; Cardoso, C.S.; Mars, M.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Marcolino, M.S. Use of Smartphone-based instant messaging services in medical practice: A cross-sectional study. SAO Paulo Med. J. 2020 , 138 , 86–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Soegoto, H. Smartphone usage among college students. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019 , 14 , 1248–1259. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011 , 54 , 241–251. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Jiao, Y.; Ertz, M.; Jo, M.S.; Sarigollu, E. Social value, content value, and Brand equity in social media brand communities: A comparison of Chinese and US consumers. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018 , 35 , 18–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Choudrie, J.; Pheeraphuttranghkoon, S.; Davari, S. The digital divide and older adult population adoption, use and diffusion of mobile phones: A quantitative study. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020 , 3 , 673–695. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chang, Y.S.; Jeon, S.; Shamba, K. Speed of catch-up and digital divide: Convergence analysis of mobile celular, Internet, and fixed broadband for 44 African countries. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2020 , 23 , 217–234. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Atik, H.; Unlu, F. Industry 4.0—Related digital divide in enterprises: An analysis for the European Union—28. Sosyoekonomi 2020 , 28 , 225–244. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ye, L.; Yang, H. From digital divide to social inclusión: A tale of mobile platform empowerment in rural áreas. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 2424. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Beigi, M.; Otaye, L. Social media, work and nonwork interface: A qualitative inquiri. Appl. Psychol. 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ramawela, S.; Chukwuere, J. Cultural influence on the adoption of social media platforms by employees. Knowl. Manag. E-Learning Int. J. 2020 , 12 , 344–358. [ Google Scholar ]

- Myagkov, M.; Shchekotin, E.V.; Chudinov, S.I.; Goiko, V. A comparative analysis of right-wing radical and Islamist communities’ strategies for survival in social networks evidence from the Russian social network VKontakte). Media War Conflict 2020 , 13 , 425–447. [ Google Scholar ]

- Park, C.S.; Kaye, B.K. Smartphone and self-extension: Functionally, anthropomorphically, and ontologically extending self via the Smartphone. Mob. Media Commun. 2019 , 7 , 215–231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aboujaoude, E. Problematic Internet use two decades later: Apps to wean us of apps. CNS Spectr. 2019 , 24 , 371–373. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Labrecque, L.I.; vor dem Esche, J.; Mathwick, C.; Novak, T.P.; Hofacker, C.F. Consumer power: Evolution in the digital age. J. Interact. Mark. 2013 , 27 , 257–269. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009 , 52 , 357–365. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ratchford, B.T. The impact of digital innovations on marketing and consumers. In Review of Marketing Research ; Emerald Publishing Limited: West Yorkshire, UK, 2020; Volume 16, pp. 35–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wawrowski, B.; Otola, I. Social Media Marketing in Creative Industries: How to Use Social Media Marketing to Promote Computer Games? Information 2020 , 11 , 242. [ Google Scholar ]

- Polanco, L.; Debasa, F. The use of digital marketing strategies in the sharing economy: A literature review. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2020 , 8 , 217–229. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, W.-L.; Malthouse, E.C.; Calder, B.; Uzunoglu, E. B2B content marketing for professional services: In-person versus digital contacts. Ind. Mark. Mngag. 2019 , 81 , 160–168. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jin, S.V.; Muqaddam, A.; Ryu, E. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019 , 37 , 567–579. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Meng, J.; Peng, W.; Tan, P.-N.; Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Bae, A. Diffusion size and structural virality: The effects os message and network features on spreading health information on twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018 , 89 , 111–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- McCain, J.L.; Campbell, W.K. Narcissism and Social Media Use: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2018 , 7 , 308–327. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cao, X.; Ali, A. Enhancing team creative performance through social media and transactive memory system. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018 , 39 , 69–79. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zengin, O.; Onder, M.E. Youtube for information about side effects of biologic therapy: A social media analysis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020 , 23 , 1645–1650. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Semenza, D.C.; Bernau, J.A. Information-seeking in the wake of tragedy: An examination of public response to mass shootings using Google Search data. Sociol. Perspect. 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sherine, A.; Seshagiri, A.; Sastry, M. Impact of Whatsapp interaction on improving L2 speaking skills. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020 , 15 , 250–259. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lv, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y. How Can E-Commerce Businesses Implement Discount Strategies through Social Media? Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 7459. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hausmann, A.; Toivonen, T.K.; Slotow, R.; Tenkanen, H.T.O.; Moilanen, A.J.; Heikinheimo, V.V.; Di Minin, E. Social media data can be used to understand tourists’ preferences for nature-based experiences in protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 2018 , 11 , e12343. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Nee, R.C.; Barker, V. Co-viewing virtually: Social outcomes of second screening with televised and streamed content. Telev. New Media. 2020 , 21 , 712–729. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Reis, C.; Pessoa, T.; Gallego, M. Literacy and digital competence in higher education: A systematic review. REDU—Rev. Docencia Univ. 2019 , 17 , 45–58. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pescott, C.K. “I wish I was wearing a filter right now”: An exploration of identity formation and subjectivity of 10-and 11-year olds’ social media use. Soc. Media + Soc. 2020 , 6 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alonso, S.; Soler, R.; Trujillo, J.M.; Juárez, V. Innovación y competencia digital en la Educación Superior: Análisis para la excelencia. In Experiencias Pedagógicas e Innovación Educativa ; En López-Meneses, E., Cobos-Sanchiz, D., Martín-Padilla, A., Eds.; Aportaciones desde la praxis docente e investigadora, Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; pp. 3728–3740. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spante, M.; Hashemi, S.S.; Lundin, M.; Algers, A. Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use. Cogent Educ. 2018 , 5 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chacon, J.; Suelves, D.; Saiz, J.; Blanco, D. Digital competence in the curricula of Spanish public universities. REDU—Rev. Docencia Univ. 2018 , 16 , 175–191. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez, E.; Gewerc, A.; Rodríguez, A. Digital competence of primary school students in Galicia. The socio-family influence. RED—Rev. Educ. Distancia. 2019 , 61. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Valverde, D.; de Pro, A.; González, J. Secondary students’ digital competence when searching and selecting scientific information. Enseñ. Cienc. 2020 , 38 , 81–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Domingo, M.; Bosco, A.; Carrasco, S. Fostering teacher’s digital competence at university: The perception of students and teachers. RIE—Rev. Investig. Educ. 2020 , 38 , 167–182. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh, A.; Ferry, D.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Balasubramanian, S. Using virtual reality in biomedical engineering education. J. Biomech. Eng. 2020 , 142 , 142. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Makonye, J.P. Teaching Young learners pre-number concepts through ICT mediation. Res. Educ. 2020 , 108 , 3–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bolumole, M. Student life in the age of COVID-19. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020 , 39 , 1357–1361. [ Google Scholar ]

- Costa, R.S.; Medrano, M.M.; Lafarga Ostáriz, P.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J. How to Teach Pre-Service Teachers to Make a Didactic Program? The Collaborative Learning Associated with Mobile Devices. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 3755. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodríguez-García, A.M.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.J.; Belmonte, J.L. Nomophobia: An individual’s growing fear of being without a Smartphone—a systematic literatura review. Int. J. Environl. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 580. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Pivetta, E.; Harkin, L.; Billieux, J.; Kanjo, E.; Kuss, D.J. Problematic Smartphone use: An empirically validated model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019 , 100 , 105–117. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Medina, L.C.; Manzuoli, C.H.; Duque, L.A.; Malfasi, S. Cyberbullying: Tackling the silent enemy. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020 , 24 , 936–947. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Park, S.; Na, E.-Y.; Kim, E.-M. The relationship between online activities, netiquette and cyberbullying. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014 , 42 , 74–81. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dawnson, V. Fans, Friends, advocates, ambassadors, and haters: Social media communities and the communicative constitution of organizational identity. Soc. Media + Soc. 2018 , 4 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Who falls for fake news? The roles of bullshit receptivity, overclaiming, familiarity, and analytic thinking. J. Pers. 2020 , 88 , 185–200. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Jiang, M.; Fu, K.-W. Chinese social media and Big Data: Big Data, big brother, big profit? Policy Internet 2018 , 10 , 372–392. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Winter, S.; Maslowska, E.; Vos, A. The effects of trait-based personalization in social media advertising. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021 , 114 , 106525. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brusco, J.M. Know your netiquette. AORN J. 2011 , 94 , 279–286. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Scheuermann, L.; Taylor, G. Netiquette. Int. Res. 1997 , 7 , 269–273. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- McMurdo, G. Netiquettes for networkers. J. Inf. Sci. 1995 , 21 , 305–318. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sabra, J.B. “I hate when They do that!” Netiquette in mourning and memorialization among Danish Facebook users. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 2017 , 61 , 24–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pregowski, M. The netiquette and its expectations—The personal pattern of an appropriate Internet user. Stud. Socjol. 2009 , 2 , 109–130. [ Google Scholar ]

- Helsper, E.; Whitty, M. Netiquette within married couples: Agreement about acceptable online behavior and surveillance between partners. Comput. Hum. Behavr. 2010 , 26 , 916–926. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fuller, D. Electronic manners and netiquette. Athl. Ther. Today 2004 , 9 , 40–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson, J.C.; Lloyd, B.A. E-mail etiquette (netiquette). In Proceedings of the Conference Record of Annual Pulp and Paper Industry Technical Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–21 June 2002; pp. 111–114. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammond, L.; Moseley, K. Reeling in proper “netiquette”. Nurs. Made Incred. Easy. 2018 , 16 , 50–53. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hills, L. E-mail netiquette for the medical practice employee: 50 do’s and don’ts. J. Med. Prac. Manag. 2011 , 27 , 112–117. [ Google Scholar ]

- McCartney, P.R. Netiquette. Maintaining confidentiality and privacy on discussion lists. Nurs. Women’s Health 2000 , 4 , 28–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sturges, P. Remember the human: The first rule of netiquette, librarians and the Internet. Online Inf. Rev. 2002 , 26 , 209–216. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Conald, S. Reclaiming the Wireless classroom when netiquette no longer Works. Coll. Teach. 2012 , 60 , 130. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buelens, H.; Totte, N.; Deketelaere, A.; Dierickx, K. Electronic discussion fórums in medical ethics education: The impact of didactic guidelines and netiquette. Med. Educ. 2007 , 41 , 711–717. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Artacho, E.G.; Martínez, T.S.; Martín, J.L.O.; Marín, J.A.M.; García, G.G. Teacher Training in Lifelong Learning—The Importance of Digital Competence in the Encouragement of Teaching Innovation. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 2852. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Arouri, Y.M.; Hamaidi, D.A. Undergraduate student’s perspectives of the extent of practicing netiquettes in a jordanian southern University. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2017 , 12 , 84. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Cardenas, J.; Figueroa, J.; Villarreal, E. Netiquette moral practices and norms in virtual interactions in secondary school students. Innov. Educ. 2015 , 15 , 57–71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clouder, D.; Goodman, S.; Bluteau, P.; Jackson, A.; Davies, B.; Merriman, L. An investigation of “agreement” in the context of interprofessional discussion online: A “netiquette” of interprofesional learning? J. Interprof. Care 2011 , 25 , 112–118. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Linek, S.; Ostermaier, A. Netiquette between students and their lecturers on Facebook: Injunctive and descriptive social norms. Soc. Media + Soc. 2018 , 4 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009 , 62 , 1006–1012. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- López-Belmonte, J.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.J.; López, J.A.; Pozo, S. Analysis of the productive, structural and dynamic development of Augmented Reality in Higher Education research on the Web of Science. Appl. Sci. 2019 , 9 , 5306. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Rodríguez, A.M.; López-Belmonte, J.; Agreda, M.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.J. Productive, structural and dynamic study of the concept of sustainability in the Educational field. Sustainability 2019 , 11 , 5613. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- de los Santos, P.j.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J.; Marín-Marín, J.-A.; Costa, R.S. The term equity in education: A literature review with scientific mapping in Web of Science. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 3562. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aksnes, D.W.; Sivertsen, G. A criteria-based assessment of the coverage of Scopus and Web of Science. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2019 , 4 , 1–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Soler-Costa, R.; Lafarga-Ostáriz, P.; Mauri-Medrano, M.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J. Netiquette: Ethic, Education, and Behavior on Internet—A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021 , 18 , 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031212

Soler-Costa R, Lafarga-Ostáriz P, Mauri-Medrano M, Moreno-Guerrero A-J. Netiquette: Ethic, Education, and Behavior on Internet—A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2021; 18(3):1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031212

Soler-Costa, Rebeca, Pablo Lafarga-Ostáriz, Marta Mauri-Medrano, and Antonio-José Moreno-Guerrero. 2021. "Netiquette: Ethic, Education, and Behavior on Internet—A Systematic Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031212

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Netiquette: Ethic, Education, and Behavior on Internet-A Systematic Literature Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Education Sciences, University of Zaragoza, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain.

- 2 Department of Didactics and School Organization, University of Granada, 51001 Ceuta, Spain.

- PMID: 33572925

- PMCID: PMC7908275

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18031212

In this article, an analysis of the existing literature is carried out. It focused on the netiquette (country, date, objectives, methodological design, main variables, sample details, and measurement methods) included in the Web of Science and Scopus databases. This systematic review of the literature has been developed entirely according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA). The initial search yielded 53 results, of which 18 exceeded the inclusion criteria and were analyzed in detail. These results show that this is a poorly defined line of research, both in theory and in practice. There is a need to update the theoretical framework and an analysis of the empirical proposals, whose samples are supported by students or similar. Knowing, understanding, and analyzing netiquette is a necessity in a society in which information and communication technologies (ICT) have changed the way of socializing and communicating. A new reality in which there is cyber-bullying, digital scams, fake news, and haters on social networks.

Keywords: ICT; digital competence; netiquette; social media; systematic review.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Flow diagram of PRISMA Systematic…

Flow diagram of PRISMA Systematic Review about “netiquette.”

Similar articles

- The effectiveness of internet-based e-learning on clinician behavior and patient outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Sinclair P, Kable A, Levett-Jones T. Sinclair P, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Jan;13(1):52-64. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1919. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015. PMID: 26447007

- Student and educator experiences of maternal-child simulation-based learning: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol. MacKinnon K, Marcellus L, Rivers J, Gordon C, Ryan M, Butcher D. MacKinnon K, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Jan;13(1):14-26. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1694. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015. PMID: 26447004

- Augmented and Virtual Reality in Anatomical Education - A Systematic Review. Uruthiralingam U, Rea PM. Uruthiralingam U, et al. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1235:89-101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-37639-0_5. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020. PMID: 32488637

- The utility and impact of information communication technology (ICT) for pre-registration nurse education: A narrative synthesis systematic review. Webb L, Clough J, O'Reilly D, Wilmott D, Witham G. Webb L, et al. Nurse Educ Today. 2017 Jan;48:160-171. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.10.007. Epub 2016 Oct 26. Nurse Educ Today. 2017. PMID: 27816862 Review.

- Investigating Serious Games That Incorporate Medication Use for Patients: Systematic Literature Review. Abraham O, LeMay S, Bittner S, Thakur T, Stafford H, Brown R. Abraham O, et al. JMIR Serious Games. 2020 Apr 29;8(2):e16096. doi: 10.2196/16096. JMIR Serious Games. 2020. PMID: 32347811 Free PMC article. Review.

- Mapping automatic social media information disorder. The role of bots and AI in spreading misleading information in society. Tomassi A, Falegnami A, Romano E. Tomassi A, et al. PLoS One. 2024 May 31;19(5):e0303183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0303183. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 38820281 Free PMC article.

- Fake news research trends, linkages to generative artificial intelligence and sustainable development goals. Raman R, Kumar Nair V, Nedungadi P, Kumar Sahu A, Kowalski R, Ramanathan S, Achuthan K. Raman R, et al. Heliyon. 2024 Jan 24;10(3):e24727. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24727. eCollection 2024 Feb 15. Heliyon. 2024. PMID: 38322879 Free PMC article.

- Exploration of Cyberethics in Health Professions Education: A Scoping Review. De Gagne JC, Cho E, Randall PS, Hwang H, Wang E, Yoo L, Yamane S, Ledbetter LS, Jung D. De Gagne JC, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Nov 10;20(22):7048. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20227048. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023. PMID: 37998279 Free PMC article. Review.

- Design and validation of a questionnaire for the evaluation of educational experiences in the metaverse in Spanish students (METAEDU). López-Belmonte J, Pozo-Sánchez S, Lampropoulos G, Moreno-Guerrero AJ. López-Belmonte J, et al. Heliyon. 2022 Nov 2;8(11):e11364. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11364. eCollection 2022 Nov. Heliyon. 2022. PMID: 36387471 Free PMC article.

- Health Communication in COVID-19 Era: Experiences from the Italian VaccinarSì Network Websites. Arghittu A, Dettori M, Dempsey E, Deiana G, Angelini C, Bechini A, Bertoni C, Boccalini S, Bonanni P, Cinquetti S, Chiesi F, Chironna M, Costantino C, Ferro A, Fiacchini D, Icardi G, Poscia A, Russo F, Siddu A, Spadea A, Sticchi L, Triassi M, Vitale F, Castiglia P. Arghittu A, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May 25;18(11):5642. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115642. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. PMID: 34070427 Free PMC article.

- Kapoor K.K., Tamilmani K., Rana N.P., Patil P.P., Dwivedi Y.K., Nerur S. Advances in Social Media Research: Past, Present and Future. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018;20:531–538. doi: 10.1007/s10796-017-9810-y. - DOI

- Kaplan A.M., Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010;53:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003. - DOI

- Shin J., Jian L., Driscoll K., Bar F. The diffusion of misinformation on social media: Temporal pattern, message, and source. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018;83:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.008. - DOI

- Carlson M. Fake news as an informational moral panic: The symbolic deviancy of social media during the 2016 US presidential election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020;23:374–388. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1505934. - DOI

- Chibuwe A. Social Media and Elections in Zimbabwe: Twitter War between Pro-Zanu-PF and Pro-MDC-A Netizens. Communicatio. 2020:1–24. doi: 10.1080/02500167.2020.1723663. - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- DOI: 10.1080/10447318.2023.2188534

- Corpus ID: 257644182

Netiquette as Digital Social Norms

- Maxi Heitmayer , Robin Schimmelpfennig

- Published in International journal of… 19 March 2023

- Computer Science, Sociology

9 Citations

Social normativity in the transition of new media: the case of facebook in vietnam, mastering digital ethic: uncovering the influence of self-control, peer attachment, and emotional intelligence on netiquette through adolescent social media exposure, the second wave of attention economics. attention as a universal symbolic currency on social media and beyond, x (twitter): a protective platform for personal revelations among indonesian lgbtq adolescents, exploring lecturers ethical dilemmas in digital communication: a case study of telegram usage in college education in russia, introducing smart machines technology and netiquette for highschool students, digital hygiene skills and cyberbullying reduction: a study among teenagers in kazakhstan, netiquette practices and perceptions in tesol-related online communities, online communities as a risk factor for gambling and gaming problems: a five-wave longitudinal study, 138 references, netiquette between students and their lecturers on facebook: injunctive and descriptive social norms.

- Highly Influential

Social Norms: A Review

Socially mediated publicness: an introduction, an approach to global netiquette research, rediscovering the netiquette: the role of propagated values and personal patterns in defining identity of the internet user., "to listen, share, and to be relevant" - learning netiquette by reflective practice, social media, work and nonwork interface: a qualitative inquiry, a focus theory of normative conduct: a theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior, cultural evolution in the digital age, older adults’ perceived sense of social exclusion from the digital world, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 October 2020

Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being

- Erica R. Bailey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2924-2500 1 na1 ,

- Sandra C. Matz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0969-4403 1 na1 ,

- Wu Youyou 2 &

- Sheena S. Iyengar 1

Nature Communications volume 11 , Article number: 4889 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

120k Accesses

63 Citations

443 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Social media users face a tension between presenting themselves in an idealized or authentic way. Here, we explore how prioritizing one over the other impacts users’ well-being. We estimate the degree of self-idealized vs. authentic self-expression as the proximity between a user’s self-reported personality and the automated personality judgements made on the basis Facebook Likes and status updates. Analyzing data of 10,560 Facebook users, we find that individuals who are more authentic in their self-expression also report greater Life Satisfaction. This effect appears consistent across different personality profiles, countering the proposition that individuals with socially desirable personalities benefit from authentic self-expression more than others. We extend this finding in a pre-registered, longitudinal experiment, demonstrating the causal relationship between authentic posting and positive affect and mood on a within-person level. Our findings suggest that the extent to which social media use is related to well-being depends on how individuals use it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Variation in social media sensitivity across people and contexts

Characteristics of online user-generated text predict the emotional intelligence of individuals

Like-minded sources on Facebook are prevalent but not polarizing

Introduction.

Social media can seem like an artificial world in which people’s lives consist entirely of exotic vacations, thriving friendships, and photogenic, healthy meals. In fact, there is an entire industry built around people’s desire to present idealistic self-representations on social media. Popular applications like FaceTune, for example, allow users to modify everything about themselves, from skin tone to the size of their physical features. In line with this “self-idealization perspective”, research has shown that self-expressions on social media platforms are often idealized, exaggerated, and unrealistic 1 . That is, social media users often act as virtual curators of their online selves 2 by staging or editing content they present to others 3 .

A contrasting body of research suggests that social media platforms constitute extensions of offline identities, with users presenting relatively authentic versions of themselves 4 . While users might engage in some degree of self-idealization, the social nature of the platforms is thought to provide a degree of accountability that prevents individuals from starkly misrepresenting their identities 5 . This is particularly true for platforms such as Facebook, where the majority of friends in a user’s network also have an offline connection 6 . In fact, modern social media sites like Facebook and Instagram are far more realistic than early social media websites such as Second Life, where users presented themselves as avatars that were often fully divorced from reality 7 . In line with this authentic self-expression perspective, research has shown that individuals on Facebook are more likely to express their actual rather than their idealized personalities 8 , 9 .

The desire to present the self in a way that is ideal and authentic is not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, an individual is likely to desire both simultaneously 10 . This occurs in part because self-idealization and authentic self-expression fulfill different psychological needs and are associated with different psychological costs. On the one hand, self-idealization has been called a “fundamental part of human nature” 11 because it allows individuals to cultivate a positive self-view and to create positive impressions of themselves in others 12 . In addition, authentic self-expression allows individuals to verify and affirm their sense of self 13 , 14 which can increase self-esteem 15 , and a sense of belonging 16 . On the other hand, self-idealizing behavior can be psychologically costly, as acting out of character is associated with feelings of internal conflict, psychological discomfort, and strong emotional reactions 17 , 18 ; individuals may also possess characteristics that are more or less socially desirable, bringing their desire to present themselves in an authentic way into conflict with their desire to present the best version of themselves.

Here, we explore the tension between self-idealization and authentic self-expression on social media, and test how prioritizing one over the other impacts users’ well-being. We focus our analysis on a core component of the self: personality 19 . Personality captures fundamental differences in the way that people think, feel and behave, reflecting the psychological characteristics that make individuals uniquely themselves 20 , 21 . Building on the Five Factor Model of personality 22 , we test the extent to which authentic self-expression of personality characteristics are related to Life Satisfaction, hypothesizing that greater authentic self-expression will be positively correlated with Life Satisfaction. In exploratory analyses, we also consider whether this relationship is moderated by the personality characteristics of the individual. That is, not all individuals might benefit from authentic self-expression equally. Given that some personality traits are more socially desirable than others 23 , individuals who possess more desirable personality traits are likely to experience a reduced tension between self-idealization and authentic self-expression. Consequently, individuals with more socially desirable profiles might disproportionality benefit from authentic self-expression because the motivational pulls of self-idealization and authentic self-expression point in the same—rather than the opposite—direction.

Previous literature on authentic self-expression has predominantly relied on self-reported perceptions of authenticity as (i) a state of feeling authentic 24 , or (ii) a judgement about the honesty or consistency of one’s self 25 . However, such self-reported measures have been shown to be biased by valence states, and social desirability 26 , 27 . To overcome these limitations, in Study 1 we introduce a measure of Quantified Authenticity. If authenticity is most simply defined as the unobstructed expression of one’s self 28 , then authenticity can be estimated as the proximity of an individual’s self-view and their observable self-expression. We calculate Quantified Authenticity by comparing self-reported personality to personality judgements made by computers on the basis of observable behaviors on Facebook (i.e., Likes and status updates).

By observing self-presentation on social media and comparing it to the individual’s self-view, we are able to quantify the extent to which an individual deviates from their authentic self. That is, we locate each individual on a continuum that ranges from low authenticity (i.e., large discrepancy between the self-view and observable self-expression) to high authenticity (i.e., perfect alignment between the self-view and observable self-expression). Importantly, our approach rests on the assumption that any deviation from the self-view on social media constitutes an attempt to present oneself in a more positive light, and therefore a form of self-idealization. While a deviation could theoretically indicate both self-idealization and self-deprecation, it is unlikely that users will deviate from their true selves in a way that makes them look worse in the eyes of others. A strength of our measures is that we do not postulate that self-idealization takes a particular form of deviation from the self or is associated with striving for a particular profile. Although research suggests that there are certain personality traits that are more desirable on average 29 , 30 , the extent to which a person sees scoring high or low on a given trait is likely somewhat idiosyncratic and depends—at least in part—on other people in their social network. For example, behaving in a more extraverted way might be self-enhancing for most people; however, there might be individuals for whom behaving in a more introverted way might be more desirable (e.g. because the norm of their social network is more introverted). Hence, our conceptualization of Quantified Authenticity allows for deviations in different directions (see Supplementary Information for more detail).

Quantified Authenticity and subjective well-being

In Study 1, we analyzed the data of 10,560 Facebook users who had completed a personality assessment and reported on their Life Satisfaction through the myPersonality application 31 , 32 . To estimate the extent to which their Facebook profiles represent authentic expressions of their personality, we compared their self-ratings to two observational sources: predictions of personality from Facebook Likes ( N = 9237) 33 and predictions of personality from Facebook status updates ( N = 3215) 34 . These are based on recent advances in the automatic assessment of psychological traits from the digital traces they leave on Facebook 35 . For each of the observable sources, we calculated Quantified Authenticity as the inverse Euclidean distance between all five self-rated and observable personality traits. Our measure of Quantified Authenticity exhibits a desirable level of variance, ranging all the way from highly authentic self-expression to considerable levels of self-idealization (see ridgeline plot of Quantified Authenticity calculated for self-language and Self-Likes in Supplementary Fig. 3 , see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for zero-order correlations among variables).

To test the extent to which authentic self-expression is related to Life Satisfaction, we ran linear regression analyses predicting Life Satisfaction from the two measures of Quantified Authenticity (Likes, status updates). The results support the hypothesis that higher levels of authenticity (i.e. lower distance scores) are positively correlated with Life Satisfaction (Table 1 , Model 1 without controls). These effects remained statistically significant when controlling for self-reported personality traits. Additionally, we included a control variable for the overall extremeness of an individual’s personality profile (deviation from the population mean across all five traits), as people with more extreme personality profiles might find it more difficult to blend into society and therefore experience lower levels of well-being 36 (see Table 1 , Model 2 with controls; the results are largely robust when controlling for gender and age, see Supplementary Table 3 ; see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 for interactions between individual self-reported and predicted personality traits).

To further explore the mechanisms of Quantified Authenticity, we conducted analyses that distinguished between normative self-enhancement (i.e., rating oneself as more Extraverted, Agreeable, Conscientiousness, Emotionally Stable, and Open-minded than is indicated by one’s Facebook behavior) from self-deprecation (i.e., rating oneself lower on all of these traits). While normative self-enhancement has a negative effect on well-being, normative self-deprecation has no effect. These findings suggest that self-enhancement specifically, rather than overall self-discrepancy/lack of authenticity, is detrimental to subjective well-being (see Supplementary Fig. 4 ).

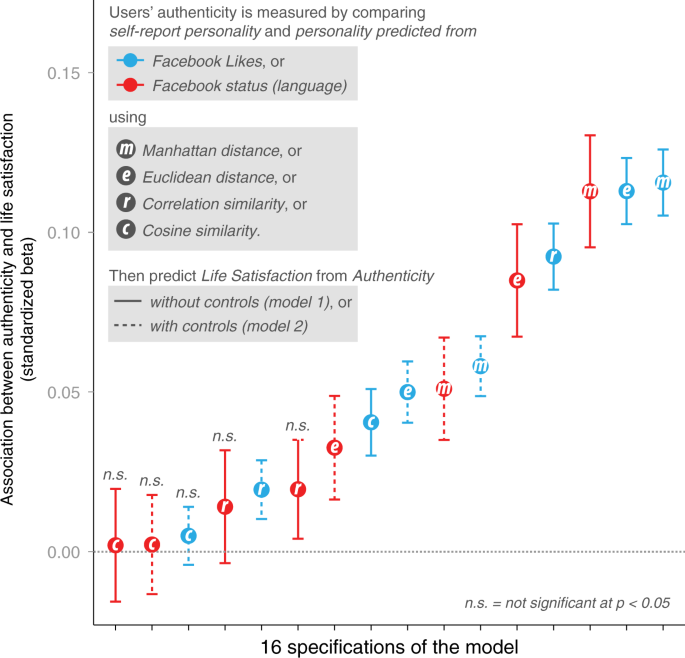

To test the robustness of our effects, we regressed Life Satisfaction on three additional measures of Quantified Authenticity (i.e., calculated using Manhattan Distance, Cosine Similarity, and Correlational Similarity; see SI for details on these measures). In both comparison sets (likes and status updates), we found significant and positive correlations between the various ways of estimating Quantified Authenticity (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 ). The standardized beta-coefficients across all four metrics of Quantified Authenticity and observable sources are displayed in Fig. 1 . Despite variance in effect sizes across measures and model specifications, the majority of estimates are statistically significant and positive (11 out of 16). Importantly, no coefficients were observed in the opposite direction. These results suggest that those who are more authentic in their self-expression on Facebook (i.e., those who present themselves in a way that is closer to their self-view) also report higher levels of Life Satisfaction.

Figure 1 presents standardized beta coefficients for Quantified Authenticity using ordinary least squares regressions in 16 individual regressions predicting Life Satisfaction. Quantified Authenticity is significantly associated with Life Satisfaction in 11 out of the 16 models. Quantified Authenticity is measured as the consistency between self-reported personality and two other sources of personality data: language and Likes, respectively, (indicated in red and blue color). Quantified Authenticity is defined using four distance metrics, respectively: Manhattan, Euclidean, correlation, and cosine similarity (indicated with a letter in the dots). Models with and without control variables are indicated with dashed and solid line, respectively.

In exploratory analyses, we considered whether authenticity might benefit individuals of different personalities differentially. In order to examine this, we regressed Life Satisfaction on the interactions between Quantified Authenticity and each of the five personality traits (e.g., Quantified Authenticity × Extraversion). The results of these interaction analyses did not provide reliable evidence for the proposition that individuals with socially desirable profiles (i.e., high openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and low neuroticism) benefit from authentic self-expression more than individuals with less socially desirable profiles (see Table 1 , Model 3). While the interactions of the five personality traits with Quantified Authenticity reached significance for some traits and measures, the results were not consistent across both observable sources of self-expression (Likes-based and Language-based). Consequently, we did not find reliable evidence that having a socially desirable personality profile boosts the effect of authenticity on well-being. Instead, individuals reported increased Life Satisfaction when they presented authentic self-expression, regardless of their personality profile.

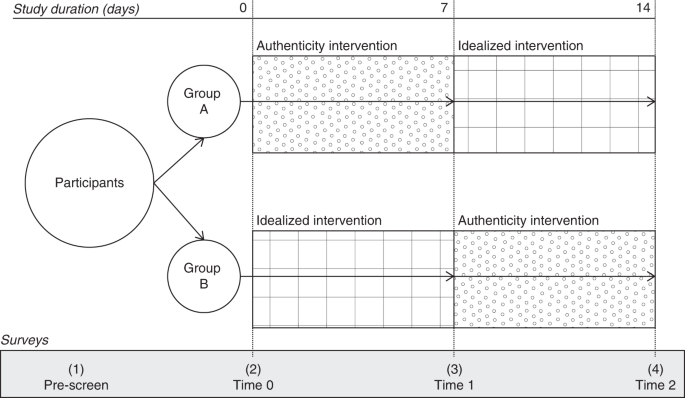

The findings of Study 1 provide evidence for the link between authenticity on social media and well-being in a setting of high external validity. However, given the correlational nature of the study, we cannot make any claims about the causality of the effects. While we hypothesize that expressing oneself authentically on social media results in higher levels of well-being, it is also plausible that individuals who experience higher levels of well-being are more likely to express themselves authentically on social media. To provide evidence for the directionality of authenticity on well-being, we conducted a pre-registered, longitudinal experiment in Study 2 (see Fig. 2 for an illustration of the experimental design).

Figure 2 presents the longitudinal experimental study design for Study 2 with key timepoints, interventions, and surveys.

Experimental manipulation of authentic self-expression on well-being

We recruited 90 students and social media users at a Northeastern University to participate in a 2-week study ( M age = 22.98, SD age = 4.17, 72.22% female). The sample size deviates from our pre-registered sample size of 200. The reason for this is that the behavioral research lab of the university was shut down after the first wave of data collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

All participants completed two intervention stages during which they were asked to post on their social media profiles in a way that was: (1) authentic for 7 days and (2) self-idealized for 7 days. The order in which participants completed the two interventions was randomly assigned. This experimental set-up allowed us to study the effects of authentic versus idealized self-expression on social media in between-person (week 1) and within-person analyses (comparison between week 1 and week 2). All analyses were pre-registered prior to data collection 37 . Given the reduced sample size, the effects reported in this paper are all as expected in effect size, but only partially reached significance at the conventional alpha = 0.05 level. Consequently, we also consider effects that reach significance at alpha = 0.10 as marginally significant.

All participants completed a personality pre-screen (IPIP) 38 prior to beginning the study, and received personalized feedback report at the beginning of the treatment period (t0). Both the authentic and self-idealized interventions (see Methods for details) asked participants to reflect on that feedback report and identify specific ways in which they could alter their self-expression on social media to align their posts more closely with their actual personality profile (authentic intervention) or to align their posts more closely with how they wanted to be seen by others (see Supplementary Information for treatment text and examples of responses). The operationalization of the treatment follows our conceptualization of Quantified Authenticity in Study 1 in that it does not prescribe the direction of personality change (e.g. towards higher levels of extraversion). Instead, this design leaves it up to participants what posting in a more desirable way means in relation to their current profile.

Participants self-reported their subjective well-being as Life Satisfaction 39 , a single-item mood measure, and positive and negative affect 40 a week after the first intervention (t1), and a week after the second intervention (t2). This design allowed us to examine the causal nature of posting for a week in which participants posted authentically (“authentic, real, or true”), compared to a week in which they posted in a self-idealized way (“ideal, popular or pleasing to others”). Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals who post more authentically over the course of a week would self-report greater subjective well-being at the end of that week, both at the between and within-person level.

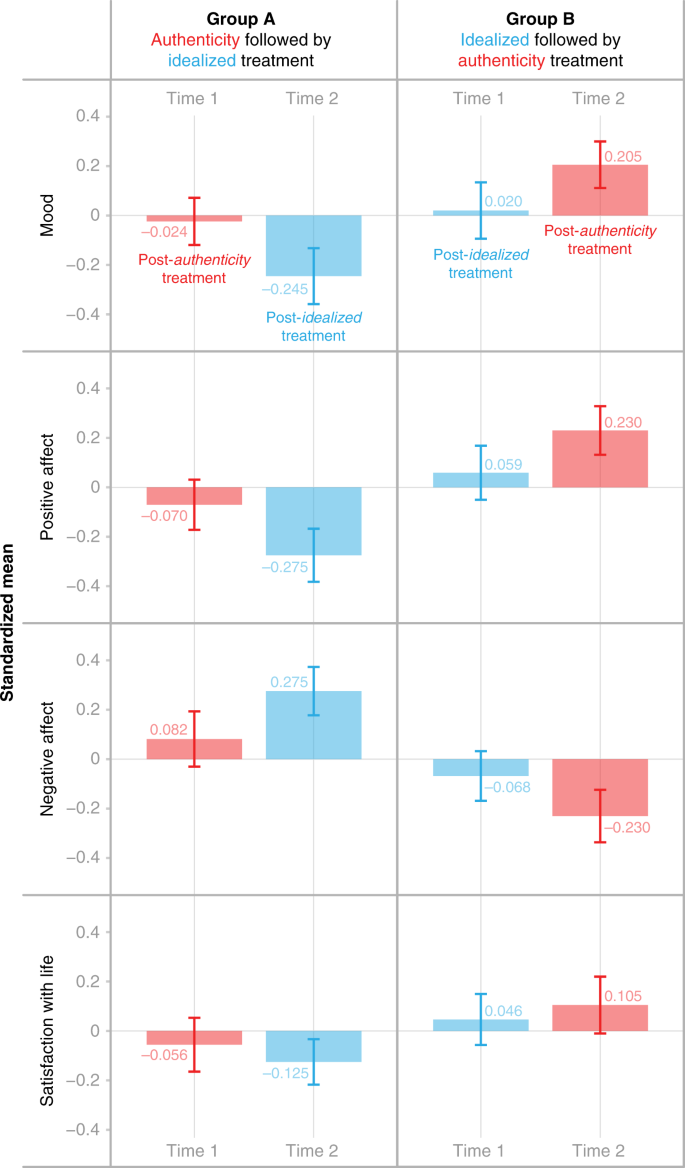

We examined the effect of authentic versus self-idealized expression at the between person level at t1 (see t1 in Fig. 3 ) using independent t -tests. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find any significant differences between the two conditions for any of the well-being indicators. This suggests that individuals in the authentic vs. self-idealized conditions did not differ from one another in their level of well-being after the first week of the study. However, when examining the effect within subjects using dependent t -tests we found that participants reported significantly higher levels of well-being after the week in which they posted authentically as compared to the week in which they posted in a self-idealized way. Specifically, the well-being scores in the authentic week were found to be significantly higher than in the self-idealized week for mood (mean difference = 0.19 [0.003, 0.374], t = 2.02, d = 0.43, p = 0.046) and for positive affect (mean difference = 0.17 [0.012, 0.318], t = 2.14, d = 0.45, p = 0.035), and marginally significant for negative affect (mean difference = −0.20 [−0.419, 0.016], t = −1.84, d = 0.39, p = 0.069). There was no significant effect on Life Satisfaction (mean difference = 0.09 [−0.096, 0.274], t = 0.96, d = 0.20, p = 0.342).

The bar chars illustrate the standardized mean of well-being indicators (mood, positive affect, negative affect, and Life Satisfaction) across two study time points by condition. The red bars indicate scores for the weeks in which participants were asked to post authentically, and the blue bars scores for the weeks in which they were asked to post in a self-idealized way. Error bars represent standard errors. The left-side panel presents Group A who received the authenticity treatment followed by the idealized treatment. The right-side panel presents Group B who received the idealized treatment followed by the authenticity treatment. This experiment was conducted once with independent samples in each group.

These findings are reflected in Fig. 3 which showcases the interactions between condition and time point. The graphs highlight that subjective well-being was higher in the weeks in which participants were asked to post authentically (red bars) compared to those in which they were asked to post in a self-idealized way (blue bars). While there was no difference in subjective well-being across conditions at t1, subjective well-being measures differed significantly between the authentic and self-idealized conditions at t2. We found no significant difference between conditions on Life Satisfaction (mean difference = 0.29 [−0.226, 0.798], t = 1.11, d = 0.23, p = 0.270), however, we found a significant difference between conditions such that the group which received the authenticity treatment had greater positive affect (mean difference = 0.45 [0.083, 0.825], t = 2.43, d = 0.51 , p = 0.017), lower negative affect (mean difference = −0.57 [−1.034, −0.113], t = −2.47, d = 0.52, p = 0.015), and higher overall mood (mean difference = 0.40 [0.028, 0.775], t = 2.14, d = 0.45 , p = 0.036).

The findings of the experiment provide support for the causal relationship between posting authentically, compared to posting in a self-idealized way, on the more immediate affective indicators of subjective-wellbeing, including mood and affect, but not on the more long-term, cognitive indicator of life satisfaction. This findings aligns with our pre-registration in that we had predicted mood and affect measures to be more sensitive to the treatment compared to Life Satisfaction, which is a broader global assessment one’s overall life 39 and less likely to change in the course of a week.

Additionally, the fact that we did not find significant effects in our between-subjects analysis in the first week of the study suggests that authentic self-expression might be difficult to manipulate in a one-off treatment as social media users are likely used to expressing themselves on social media both authentically and in a self-idealized way. Thus, when only one strategy is emphasized, participants might not shift their behavior. This is supported by the finding that participants did not differ significantly in their subjective experience of authenticity on social media at t1 (mean in authentic condition at t1 = 5.56, mean in self-idealized condition at t1 = 5.55, t = 0.05, d = 0.01, p = 0.958; Participants responded to a single item, which read “This past week, I was authentic on social media” on a 7-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree), indicating that the between-subjects manipulation was unsuccessful in getting people to shift their behaviors more toward self-idealized or authentic self-expression compared to their baseline. However, the contrast of the two strategies highlighted in the within-subjects part of the study seems to have successfully shifted participants’ behavior. When compared within person, students did indeed report higher levels of experienced authenticity in their posting during the week in which they were instructed to post authentically (mean difference = 0.30 [0.044, 0.556], t = 2.33, d = 0.49, p = 0.022).

We often hear the advice to just be ourselves. Indeed, psychological theories have suggested that behaving in a way that is consistent with the self-view is beneficial for individual well-being 41 . However, prior investigations of authenticity and well-being have relied solely on self-reported measures which can be confounded by valence and social desirability biases. We estimated authenticity as the proximity between the self-view and self-expression on social media—which we termed Quantified Authenticity—and found that authentic self-expression on social media was correlated with greater Life Satisfaction, an important component of overall well-being. This effect was robust across two comparison points, computer modeled personality based on Facebook Likes and status updates. Our findings suggest that if users engage in self-expression on social media, there may be psychological benefits associated with being authentic. We replicate this finding in a longitudinal experiment with university students; being prompted to post in an authentic way was associated with more positive mood and affect, and less negative mood within participants. Contrary to our second hypothesis, we did not find consistent support for interactions between personality traits and authenticity, such that individuals with more socially desirable traits would benefit more from behaving authentically. Instead, our findings suggest that all individuals regardless of personality traits could benefit from being authentic on social media.

Our findings contribute to the existing literature by speaking directly to conflicting findings on the effects of social media use on well-being. Some studies find that social media use increases self-esteem and positive self-view 42 , while others find that social media use is linked to lower well-being 43 . Still, others find that the effect of social media on well-being is small 44 or non-existent 45 . In an attempt to reconcile these mixed findings, researchers have suggested that the extent to which social media platforms related to lower or higher levels of well-being might depend not on whether people use them but on how they use them. For example, research has shown that active versus passive Facebook use has divergent effects on well-being. While passively using Facebook to consume the content share by others was negatively related to well-being, actively using Facebook to share content and communicate was not 46 . We add to this growing body of research by suggesting that effects of social media use on well-being may also be explained by individual differences in self-expression on social media.

Our study has a number of limitations that should be addressed by future research. First, our analyses focused exclusively on the effects of authentic social media use on well-being, and cannot speak to the question of whether an authentic social media use is better or worse than not using social media at all. That is, even though using social media authentically is better than using it in a more self-idealizing way, the overall effect of social media use on well-being might still be a negative. Future research could address this question by directly comparing no social media use to authentic social media use in both correlational and experimental settings.

Second, our findings do not provide any insights into why individuals might behave more or less authentically. For example, a deviation from the self-view might be explained by a lack of self-awareness, or an intentional misrepresentation of the self. It is possible that depending on whether deviation is driven by intent or not, authenticity might be more or less strongly related to well-being. That is, the psychological costs of deviating from one’s self-view might be stronger when they are intentional such that the individual is fully aware of the fact that they are behaving in a self-idealizing way. Future research should explore this factor empirically.

Finally, the effects of authentic self-presentation on social media on well-being are robust but small (max(β) = 0.11) when compared to compared to other important predictors of well-being such as income, physical health, and marriage 47 , 48 , 49 . However, we argue that the effects described here are meaningful when trying to understand a complex and multifaceted construct such as Life Satisfaction. First, Study 1 captures authenticity using observations of actual behavior rather than self-reports. Given that such behavioral data captured in the wild do not suffer from the same response biases as self-reports which can inflate relationships between variables (e.g. common method bias 50 ), and are often noisier than self-reports, their effect sizes cannot be directly compared 51 . In fact, the effect sizes obtained in Study 2 which was conducted in a much more controlled, experimental setting shows that the effect of authenticity on subjective well-being is substantially larger when measured with more traditional methods (max(d) = 0.45). In addition, while other factors such as employment and health are stronger predictors of well-being, they can be outside of the immediate control of the individual. In contrast, posting on social media in a way that is more aligned with an individual’s personality is both up to the individual and relatively easy to change.

Social media is a pervasive part of modern social life 52 . Nearly 80% of Americans use some form of social media, and three quarters of users check these accounts on a daily basis 53 . Many have speculated that the artificiality of these platforms and their trend towards self-idealization can be detrimental for individual well-being. Our results suggest that whether or not engaging with social media helps or hurts an individual’s well-being might be partly driven by how they use those platforms to express themselves. While it may be tempting to craft a self-enhanced Facebook presence, authentic self-expression on social media can be psychologically beneficial.

Study 1. Participants and procedure

Data were collected through the MyPersonality project, an application available on Facebook between 2007 and 2012 31 . Users of the app completed validated psychometric tests including a measure of the Big Five personality traits 22 , 54 , and received immediate feedback on their responses. A subsample of myPersonality users also agreed to donate their Facebook profile information—including their public profiles, their Facebook likes, their status updates, etc.—for research purposes. In addition, users could invite their Facebook friends to complete the personality questionnaire on their behalf, judging not their own personality but that of their friend.

To calculate authenticity, we developed a measure we refer to as Quantified Authenticity (QA). To compute this measure, we compared a person’s self-reported personality to two external criteria: (1) their personality as predicted from Facebook Likes, and (2) their personality as predicted from the language used in their status updates (see “Measures” section below for more information). The number of participants varied between the two samples based on exclusionary criteria. To be included in the Language-based model, individuals had to have posted at least 500 words of Facebook status updates ( N = 3215). In the Likes-based model, only participants with 20 or more Likes were included ( N = 9237).

Big Five personality

Participants’ personality was measured using the well-established Five Factor model of personality, also known as Big Five traits 54 , 55 . The Five Factor model posits five relatively stable, continuous personality traits: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. The Big Five personality traits have been found to be stable across cultures, instruments, and observers 56 . Additionally, years of research have linked them to a broad variety of behaviors, preferences and other consequential outcomes, including well-being 57 and behavior on Facebook 58 .

Self-reported personality

Participants’ views of their own personalities are based on the well-established International Personality Item Pool or IPIP 38 . Participants included in the analyses responded to 20–100 questions using a 5 point Likert-scale where 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Computer-based predictions of personality from likes and status updates

Recent methodological advances in machine learning have provided researchers with the ability to predict the personality of individuals from their social media profiles 33 , 34 , 35 . Here, we used personality prediction of personality from Facebook Likes and the language used in status updates. For Facebook Likes ( N = 9327), we obtained the personality predictions made by Youyou and colleagues 33 , who used a 10-fold cross-validated LASSO regression to predict Big Five personality traits out of sample. On average, the predictions captured personality with an accuracy of r = 0.56 (correlation between predicted and self-reported scores). For status updates ( N = 3215), we obtained the predictions made by Park et al. 34 , who used cross-validated Ridge regression to infer personality from language features, such as individual words, combinations of words (n-grams), and topics. On average, the predictions captured personality with an accuracy of r = 0.41 (correlation between predicted and self-reported scores).

Personality extremeness

We calculated extremeness of participants’ personality profiles as a control variable for our analyses by summing the absolute z -scores on all five traits. We include extremeness because extreme individual scores tend to produce larger absolute difference scores. Additionally, previous work has found that people with more extreme personality profiles might find it more difficult to blend into society and therefore experience lower levels of well-being 36 .

Self-ratings of well-being

Individuals reported their Life Satisfaction—a key component of subjective well-being—on a five-item scale 39 . The SWLS has been shown to be a meaningful psychological construct, correlated with a number of important life outcomes such as marital status and health 59 .

Quantified Authenticity

Quantified Authenticity was calculated in three steps. First, we z -standardized the personality scores on each of the three measures (self, Likes, language) to obtain a person’s relative standing on the five personality traits in comparison to the reference group. Second, we computed the distance between self-reported personality and each of the externally inferred personality profiles using Euclidean distance, a widely established distance measure, which has been used in previous psychological research 36 . To make our measure more intuitively interpretable, we finally subtracted the distance measure from zero to obtain a measure of Quantified Authenticity for which higher scores indicate higher levels of authenticity. See Eq. ( 1 ) below.

For individual i , x i is the Cartesian coordinate of the self-view in a 5 -dimensional personality space. For individual i, y i is the Cartesian coordinate of the language-, or likes-based personality. Our measure of Quantified Authenticity exhibited desirable level of variance, ranging all the way from highly authentic self-expression to considerable levels of self-idealization (see ridgeline plot of standardized Quantified Authenticity calculated based on Language and Likes in Supplementary Fig. 3 ). Additional information on the calculation of the three other metrics of Quantified Authenticity (i.e., Manhattan distance, correlational similarity, and cosine similarity) can be found in the SI.

Study 2. Participants and procedure