CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Research about inclusive education: are the scope, reach and limits empirical and methodological and/or conceptual and evaluative.

- Graduate School of Education, University of Exeter, Exeter, England

This paper argues for a broader conception about research into inclusive education, one that extends beyond a focus on empirical factors associated with inclusive education and the effects of inclusive education. It starts with a recent summary of international research into the effects of inclusive education on students with SEN/disabilities and those without. On the basis of this review, it examines a model showing the complexity of factors involved in asking questions about the effects of inclusive education. This complexity reflects the ambiguity and complexity of inclusive education, which is discussed in terms of varied contemporary positions about inclusive education. The analysis illustrates how there has been more focus on thin concepts of inclusion (as setting placement or in general terms) rather than its normative and value basis, which reflects a thick concept of inclusion. The paper concludes by illustrating with the use of a version of the capability approach how there are value tensions implicit in inclusion about difference and about personal vs. public choice. This requires value clarification and some settlement about the balance of values, which is where deliberative democratic principles and processes have a crucial role. The proposed answer to the paper’s question about the scope, reach and limits of research in inclusive education is that such research involves both empirical, methodological, and evaluative matters. Educational research about inclusive education is not just empirical, it also involves value and norm clarification, a process which has been too often ignored.

Introduction

In asking about the scope, reach and limits of research in inclusive education in this paper, the aim is to examine some contemporary findings in one area of research in inclusive education and how value positions are implicated. Policy makers are interested in the effects of inclusive education and researchers are keen to provide evidence that bears on policy making. The paper will start off with a research review which was conducted as a specific response to a policy maker’s request. However, this kind of research, which can be described as treating inclusion as a technical matter, has been widely criticized. For example, Slee and Weiner (2001) identify two groups of researchers; (i) those who work within, what they call the “positivist paradigm,” accept the way things are, attempt to make marginal reforms and who criticize “full inclusion” as ideological and (ii) those who see inclusive education as cultural politics and call for educational reconstruction. Though these authors align with the second group, it is interesting that the first author subsequently uses research which treats inclusive education as a technical matter to support a position about inclusive education. Subsequently, Slee (2018) has referred to a review by Hehir et al. (2016) that depends on a systematic review of technical style studies to support his claims about how: “adjustments made to classrooms, to curriculum and to pedagogy to render classrooms more inclusive and enabling also benefit students without disabilities” (p. 69).

In discussing what this review of Inclusive Education Effects (IE) can tell us and what it cannot, the paper will examine a model showing the complexity of factors involved in asking questions about the effects of inclusive education. It then moves on to consider what other kinds of questions might be asked in research about inclusive education that cannot be addressed through effects-focussed methodologies. At this point in the paper, the issue arises about how the results from empirical studies relate to what is called inclusion or inclusive education. So, varied perspectives on inclusive education are summarized, including those of some parents, based on a recent study of parents’ experiences of deciding to opt for special schooling. These perspectives reflect the ambiguity and complexity of inclusive education, illustrating how the concept is often used in a thin way in empirical studies by focusing more on its empirical identification and causal relationships than its more expanded normative and value basis, a thick concept of inclusion. The paper concludes by using a version of the capability approach to examine issues about “full inclusion” and what can be called a more balanced or reasoned inclusion. This reveals two key dilemmas about difference and about personal vs. public choice that are relevant to providing inclusion with a well-founded value basis. The paper concludes with the claim that research into inclusive education involves technical, methodological, and evaluative matters. It proposes a role for public deliberation in clarifying and settling these value and norm clarification, process which have been largely ignored.

Review of inclusive education effects

The aims of this review were to (i) identify and summarize contemporary international research on IE effects and (ii) draw implications for policy, practice and future research in IE field. The context of this review was that it was undertaken in 2019 by three members of the Lead Group of the SEN Policy Research Forum (SENPRF) 1 following informal communications with the Government Department for Education (DfE) about national SEN and inclusion policy. The Forum was asked to summarize relevant research which was then presented as well to the national SEN Review ( Gray et al., 2020 ).

Ten sources were identified coming from a 2 stage process. Firstly, the authors identified relevant papers already known to them (4 papers). This was then supplemented, secondly, by a data base search using ERIC and ERC databases for the period 2009–2019. Search terms involved all variations of inclusion/inclusive education/mainstreaming × achievement/social emotional X effects. For the ERIC database 630 articles were retrieved with only 5 identified as relevant; for the ERC database 544 articles were retrieved with only one identified as relevant. In this way 10 papers were identified (see Gray et al., 2020 for more details). Five of the papers were reviews of international studies ( Ruijs and Peetsma, 2009 ; Dyssegaard and Larsen, 2013 ; Oh-Young and Filler, 2015 ; Hehir et al., 2016 ; Szumski et al., 2017 ). Some of these reviews included studies conducted before the 2009 cut-off date used for this review. Three involved a quasi-experimental designs, two with collected data and one using national administrative data. Four involved multi-variate statistical analyses of longitudinal data; with 2 using cohort studies. The papers were either from the United States or European countries, with none from the United Kingdom. Inclusion was mostly defined in the studies covered in terms of a mainstream class setting compared to a special class/school setting. Few gave details about the setting. Where they did, the proportion of time in the mainstream class was reported (e.g., greater or less than 80% of time). In one example, an inclusive setting was defined as being in general classrooms with several hours support per week and receiving therapy support too. Special school was described as small classes (5–8 children) taught by a specialist teacher with an assistant and therapy support ( Sermier Dessemontet et al., 2012 ).

The review was organized into four broad areas: (i) academic effects on students with SEN/disabilities and (ii) social-emotional effects on students with SEN/disabilities, (iii) academic effects on students without SEN/disabilities, and (iv) social-emotional effects on students without SEN/disabilities. For the first area, five sources were used with the balance of findings showing more academic gains of students with a range of SEN in ordinary rather than separate settings. These students were broadly characterized as having mild to moderate SEN/disabilities with the gains being in mostly literacy, but some in maths. One of the review papers reminded readers that this evidence did not show that “full” or “complete” inclusion had higher gains to special education settings for students with mild disabilities.

For the review area, academic effects for non-disabled students, the reviews of older studies, done before 2010 presented a mixed overall picture. However, on balance most studies showed more neutral or positive than negative effects for non-disabled students. However, some more recent individual studies rather than reviews indicated specific weak to moderate negative academic effects on non-disabled students, e.g., having classmates with emotional/behavior difficulties ( Fletcher, 2010 ) or special school returners ( Gottfried and Harven, 2015 ). Other studies indicated some small positive effects, associated with positive teacher attitudes, their training, strategies geared to diverse needs and problem-solving oriented schools ( Hehir et al., 2016 ). In addition, reviews were mixed about the negative academic effects of students with emotional and behavior difficulties on students without SEN/disabilities.

For the review area about social-emotional effects on SEN/disabled students, there were fewer studies than for academic effects. Here the sources showed mixed results. While one review referred to mostly positive outcomes ( Hehir et al., 2016 ), the other significant review reported that no conclusions can be drawn ( Ruijs and Peetsma, 2009 ). One specific recent study found no adaptive behavior differences across settings ( Sermier Dessemontet et al., 2012 ). For the fourth review area about social emotional effects for non-disabled students, there were also relatively few studies. These were recorded in review papers and showed some positive effects, e.g., less discriminating attitudes, increased acceptance, and understanding.

Research limitations and some relevant conclusion

As in other educational research focussed on effects, there are various design limitations to these inclusion effect studies. These studies use a range of approaches from quasi-experimental designs (QED) to multi-variate statistical analyses of longitudinal data and administrative data sets. With QED, as there is no randomized group allocation, there can be some “participant bias,” e.g., students in inclusive settings might have higher starting levels of functioning. Many of these papers refer to a series of limitations. Studies often use differing definitions of the compared settings. Comparisons are also often defined in terms of placements, e.g., special school v. ordinary school or special class/unit vs. ordinary class, not in terms of school-level (e.g., school ethos), or class level factors (e.g., quality of teaching). Findings relate to specific student age groups and areas of SEN/disability and not others. There is also the risk that other areas of SEN/impairment may not be controlled for in comparisons. Sometimes SEN/disability is also used generically to cover a range of areas and so the comparison becomes between SEN v non-SEN or disabled vs. non-disabled. How these terms are used can also vary internationally. In terms of statistical analyses, sample sizes may be under-powered to draw confident conclusions. Some effect measures, especially for the social-emotional effects could have improved measurement characteristics (e.g., reliability and validity).

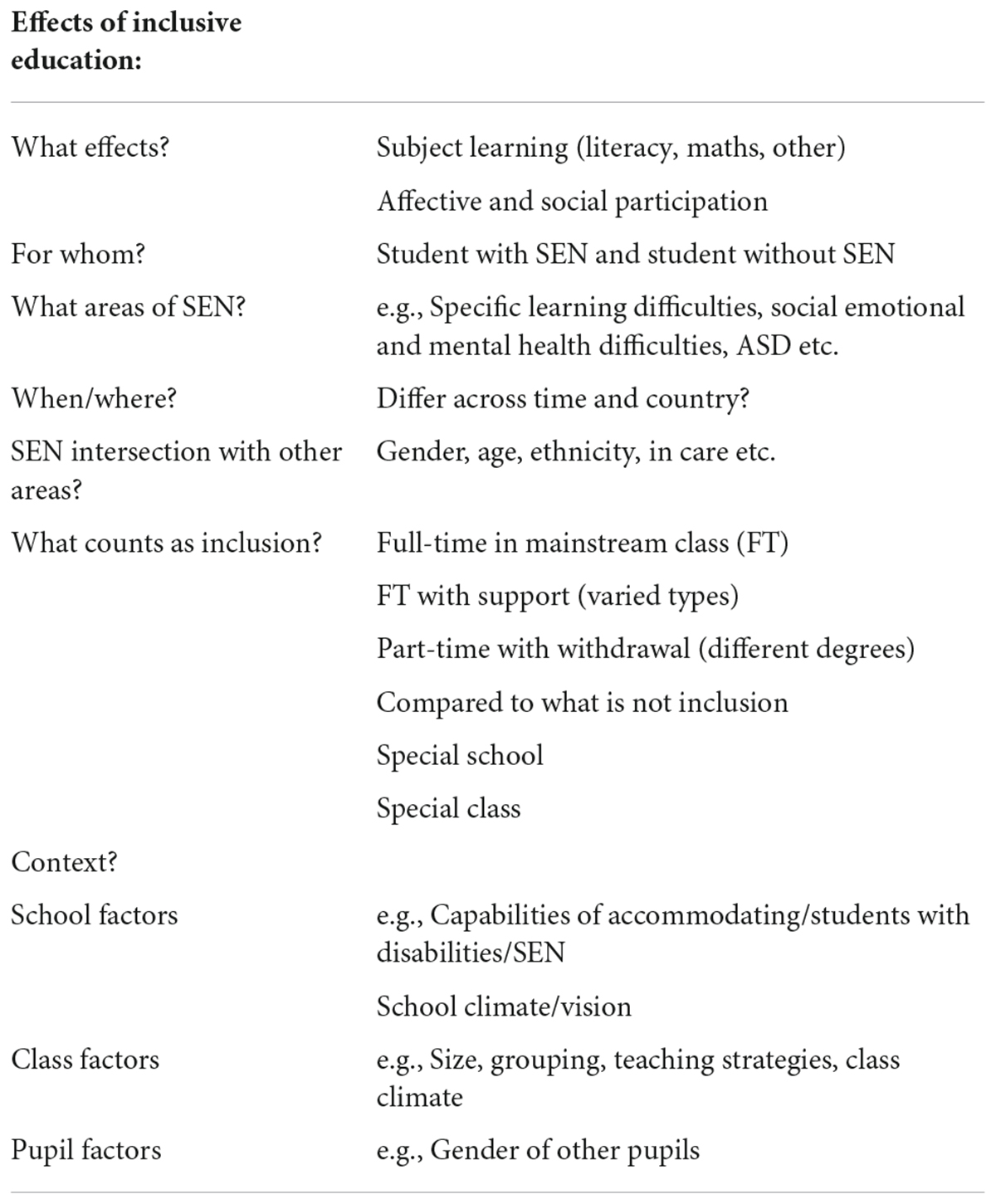

For the purposes of this paper three main concluding points can be drawn from this review of inclusive education effects. The first point is that the basic typology of effects (academic and socio-emotional inclusion effects for SEN/disabled students and non-SEN/disabled children) needs to take account of other factors. These include the kinds of SEN/disability, phases of schooling, quality of support for learning and structural class and school factors. Some of these factors might moderate the effects. These are illustrated in Table 1 .

Table 1. Framework of focus and interacting factors relevant to the effects of inclusive education.

What this framework indicates is the multi-dimensionality of inclusive education and the complexity of factors that relate to their varied effects. This implies that there is a need for more nuanced policy and practice questions about inclusive education and consequently more nuanced kinds of studies about inclusive education. This would counter the commonly found preferences that look for simple generalized empirical relationships to confirm pre-existing positions; avoiding what has been called the pervasive confirmation bias ( Wason, 1960 ).

The second main point to make from this review is that the balance of evidence finds neutral or small positive effects as opposed to negative effects. This means that adopting an “on balance” position is the wise way to summarize the review outcome. Both positive and negative effects need to be understood in terms of the complex interaction of individual, class and school factors, on one hand, and what counts as inclusive education and the specific types of effects, on the other. The value of a framework like in Table 1 is that it reflects points from research findings about factors in those interactions that are more or less alterable, with this having policy implications. The third main point of conclusion from this review is that it is useful to develop this kind of mapping of the kinds of interacting factors related to questions about inclusion effects. This is relevant both to the design of further studies and to drawing conclusions for policy.

Unaddressed questions about inclusive education

The kinds of effectiveness research discussed above still leave some crucial questions about inclusive education unaddressed. Although there is scope for more sophisticated research designs to evaluate the effects of inclusive education, the use of multivariate statistical techniques involves large samples which are often not available, especially in some areas of SEN/disability, e.g., severe and profound and multiple learning difficulties SLD/PMLD). So, there are questions still to be asked about the inclusion of students with SLD/PMLD and those with significant emotional and behavior difficulties. These are difficult to address partly because of the relatively low incidence of these areas of difficulties but also the scarcity of practices involving these students in what would be called inclusive settings ( Agran et al., 2020 ). In a rare US quasi-experimental study, for example, 15 pairs of early years and primary aged children with “extensive support needs,” were matched across 12 characteristics based on their first complete Individual Education Program (IEP). One child in each pair was included in general education for 80% or more of their day, while the other was in a separate special education class ( Gee et al., 2020 ). Extensive analyses were shown to indicate more engagement and higher outcomes in general classrooms. But, in terms of what this study implies for inclusive education, there are no details of the students’ level of intellectual disability in these pairs and so we do not know if they had severe/profound intellectual disabilities or in United Kingdom terms SLD or PMLD. Nor does the report indicate details about the type of support and adaptations that were made for those in the general class or whether they spent 20% of their time in a separate class setting.

In the United Kingdom by comparison, reports about inclusive practices are in the form of cases or demonstration models of inclusive practice. For example, an illustration of inclusive practice with students with PMLD involved a common interactive music program for learners with PMLD and those from a mainstream primary school that enabled learning for all involved ( Education Wales, 2020 ). Though this inclusive program took place in a special school setting, it could have also been in an ordinary school setting. Both the primary school and special school children benefitted in their own ways from the joint activities, which seemed to enable its inclusiveness through it focus on the expressive arts.

The implication is that effectiveness research about inclusive education does not bear directly on the basic questions about the future of special classes and schools, settings which have been interpreted as being inconsistent with “full inclusion” ( UNICEF, 2017 ). The uses of terms like “full inclusion” or an “inclusive system at all levels” are unclear about whether they can involve some part-time separate settings (e.g., 20% of class time) or not. They are also unclear about whether fixed term (e.g., 1 year) placements in separate settings are compatible with an inclusive system and whether an “inclusive system at all levels” implies the closure of all special schools in the foreseeable future.

Critiques of “full inclusion” over many years have been about the position representing a “moral absolute” that requires the elimination of any alternative placements or settings to ordinary class placements ( Kauffman et al., 2021 , p. 20). For Kauffman and colleagues, the “full inclusion” focus on place rather than instruction or teaching is deeply problematic. They question those interpretations of Article 24 of the CRPD ( UN, 2006 ) that the Convention implies “full inclusion” without attention to the quality of teaching and alternative placements. However, what both advocates of “full inclusion” and these above critics have in common is that they both use false oppositions or dichotomies; with one pole being favored and the other pole rejected. They mirror each other in this kind of thinking.

There have, however, also been more nuanced arguments about inclusion over the years. Fuchs and Fuchs (1998) , for example, identified strengths and limitations in arguments of both “full inclusionists” and “inclusionists.” They see the former group (full inclusionists) as focussed more on children with more severe disabilities (low incidence needs), prioritizing social attitude and interaction learning, while the latter (inclusionists) are focussed more on children with high incidence needs, prioritizing academic learning and accepting a continuum of provision. Fuchs and Fuchs (1998) raise the question of whether “full inclusionists” are willing to “sacrifice children’s academic or vocational skills” for their social priorities ( Fuchs and Fuchs, 1998 , p. 312). This identifies the differences over inclusive education as one of value priorities, a point to be returned to later in this paper.

One way to take a broader perspective is to consider the practice and theory of a “full inclusive education” commitment. From the practice perspective, we can examine the Canadian New Brunswick system, which is cited as an example of “full inclusion” ( National Council for Special Education [NCSE], 2019 ). In a statement by the Porter et al. (2012) , a core inclusive principle is that:

“… public education is universal—the provincial curriculum is provided equitably to all students and this is done in an inclusive, common learning environment shared among age-appropriate, neighborhood peers” (p. 184).

However, in this publication evidence is given of the use of part-time and full-time “streaming” in primary and secondary schools and some alternative settings (0.4–1.5% across Francophone districts: p. 91). The reference in the above core principle to “common learning environments” is central to the definition of inclusive education. This phrase was introduced as an expansive definition:

“to dispel the misperception that inclusion is having every learner in a regular classroom all the time, no matter what the circumstances” ( AuCoin et al., 2020 , p. 321).

By using this term “common learning environment” in this way and not referring to ordinary/mainstream class environments, the New Brunswick conception of inclusive education is open to use of some alternative settings which is inconsistent with “full inclusion” and compatible with the concept of a flexible continuum of provision.

Inclusive education: concept, theory, and ambiguity

Given these ambiguities, on one hand, and the passions associated with inclusion and inclusive education, on the other hand, the analysis needs to consider the value of inclusion as this might inform some of the applied questions about inclusive education. In this regard, Felder (2018) has identified that inclusion tends to be a thin concept in empirical studies, like those discussed above. This is illustrated in the way the terms inclusion/inclusive are used in these studies. It is also why “what counts as inclusion” is an important part of the framework in Table 1 about the focus and interacting factors relevant to the effects of inclusive education. What these empirical studies do is focus more on matters related to how to realize inclusive education than consider and justify its expanded normative and value basis, what Felder (2018) called a thick concept of inclusion.

For Felder, an important distinction here is between communal inclusion (gemeinschaft) and societal inclusion (gesellschaft), to use the German terms from the social theorist Tonnies. Societal inclusion is about social relationships formed through instrumental rationality, while communal inclusion is about social relationships found in friendships, love relationships and interpersonal ties. In this analysis, the structures of societal inclusion can influence what make communal inclusion possible. However, communal inclusion sets some limits to the extent to which this form of communal inclusion can be secured through human rights. Felder’s analysis implies that human rights are not able to fully secure the social freedom and recognition, esteem or solidarity that are often neglected aspects of inclusion. In Felder’s analysis inclusive education which ultimately depends on social inclusion depends on social intentionality or agents acting collectively. People need to be integrated in a cooperative societal context to use their freedoms and basic rights. This underlines the importance of people having a degree of freedom to decide where they want to be included and be associated with. And, if disabled people are to have similar freedoms as other people in positive terms, they require more goods than others, because of the problem of converting these resources into practical opportunities. This is the basic assumption deriving from the capability approach ( Sen, 1979 ), which will discussed further below.

This thick concept on inclusion can also be contrasted with some current concepts of what inclusion means in inclusive education. Two leading concepts will be discussed and contrasted with a third which relates directly to students with more severe/profound disabilities. The first perspective, proposed by Warnock (2005) emphasizes that inclusion means the entitlement of everyone to learning in a personally relevant way, wherever this takes place. This concept of inclusion can imply and be used to justify separate settings for learning, e.g., special schools and classes in general schools, while overlooking the social effects and significance of separation, especially if it is imposed. Another leading concept of inclusion in inclusive education, associated with the Inclusion Index ( Booth and Ainscow, 2011 ) focuses on increasing student participation and reducing exclusion from “the cultures, curricula and communities of local schools” (p. 6). This concept implies that “all are under same roof,” a phrase used by Warnock (2005) , with the onus on local ordinary schools to accommodate diversity. This concept says little about how much diversity can be accommodated nor whether restructuring local schools could include some internal school separation.

It is also useful to contrast these two leading concepts with a 40 year old concept of partial inclusion that relates specifically to students with more severe/profound disabilities ( Baumgart et al., 1982 ). The basic premise of the principle of partial participation is that all severely disabled students have “a right to educational services that allow them to be the most that they can be” (p. 4). This implies engaging in as many different activities in as many different environments as instructionally possible. Baumgart et al. (1982) clarify that such partial participation requires individualized adjustments or modifications of typical environmental conditions. They also note that observing severely disabled and non-disabled students will show that they do not participate in activities to the same degree and in the same ways. This concept is characterized by its strong focus on what is pedagogically possible, going beyond the generalities of the two more prominent recent concepts.

Different policy positions

The leading international policy position on inclusive education is in Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; UNICEF, 2017 ). The CRPD stresses that inclusive education is a fundamental human right for every child with a disability. It defines an inclusive education system as one that “accommodates all students whatever their abilities or requirements, and at all levels.” This position is justified in various terms: the educational case is that all children learn more effectively in an inclusive system; the social case is that this contributes to more inclusive societies and the economic case that it is more cost-effective.

However, not all countries accept Article 24 as shown by the United Kingdom Government having ratified the UNCRPD but stating specific reservations about preserving parents right to choose a special school education. This position has been United Kingdom (England) policy for over a decade. For example, the results of the consultation about the Green Paper that preceded 2014 revised SEN and disability legislation, were interpreted as showing widespread support. The public consultation was interpreted as showing support for parents to have the right to express a preference for any state funded mainstream or special school ( Department for Education [DFE], 2011 ).

It is revealing to compare these policy perspectives on inclusive education with those of parents who have selected special schools for their children with SEN/disabilities. A recent United Kingdom study examined the views of parents of pupils in special schools in the South West of England: their reasons for choosing special school, the extent to which they felt they had an independent choice, their views on alternative provision and their concepts of inclusive education ( Satherley and Norwich, 2021 ). Analysis showed that the top three reported factors as influencing decisions were school atmosphere, caring approach to pupils and class size, a finding that connected with their concepts of inclusive education. Not only does this small-scale study show distinctive parental perspectives on schooling and the dilemmas they experienced in choosing provision for their children, but concepts of inclusive education that depart from some of those discussed above. Over half considered that high quality inclusive education provision meant a sense of belonging to a class and school and social acceptance by peers, on one hand, and a more individualized curriculum, on the other. In addition, for many parents the belonging, social acceptance and Individualized curriculum was found only in special schools. By contrast, quality inclusive education rarely meant a resource base or specialist unit attached to mainstream school (28%), joint placement (21%), co-located schools (19%) or mainstream provision only (8.8%). What characterizes these parents’ perspectives was that they did not refer to placement, where provision is made. The UNCRP assumes that inclusion means placing students with disabilities within mainstream classes with appropriate adaptations ( UNCRPD, 2016 , p. 3). So, these parents mostly held different views from the dominant UNCRPD concept of inclusive education, discussed above.

The capability approach

A thick concept of inclusion in inclusive education, as discussed above, implies the importance of people having a degree of freedom to decide where they want to be included and with whom they associate. It was also suggested above that if disabled people are to have similar freedoms as other people, they require more resources than others, because of the problem of converting these resources into practical opportunities. This is where the capability approach developed by Sen (1979) can act as rich conceptual and value resource for thinking about inclusive education. Its discussion in this paper is not as a complete approach to the field, 2 but as the kind of framework that assists in thinking about what is involved in a just education system.

For Sen (1979) , the capability approach is about evaluating someone’s advantages in terms of his or her actual ability to achieve various valuable functionings as a part of living. Terzi (2014) expresses what a capability represents in terms of the “genuine, effective opportunities that people have to achieve valued functionings” (p. 124). What is distinctive about the capability approach is how it answers the political-ethical question about equality of what? Unlike perspectives which either focus on equality of resources or opportunities, the capability approach focuses on genuine opportunities. For Terzi, capabilities as genuine opportunities are important because they ensure that individuals can choose the kind of life they have reason to value. This also implies a fundamental role for agency in realizing the valued plans in one’s life. This has implications for the balance of choice, especially where it concerns children and young people. It has also been argued that a capability-oriented approach needs to acknowledge children’s agency in determining their own valued functionings and not just be determined by adults ( Dalkilic and Vadeboncoeur, 2016 ). This introduces some nuance into how a capability approach might work in relation to education, but this is not the paper to discuss these matters further. There are also issues about determining the capability set to be equalized. In considering whether there are basic universal capabilities there are also questions about opting for adequacy rather than equality in capabilities and whether some capabilities require equality. These matters will also not be addressed here.

Where the capabilities approach is incomplete is in considering the design questions of how to equalize capabilities; how to organize education to achieve this goal? Two key questions will be considered in relation to this question:

i how are “valuable functionings” identified? This is about the balance between personal preferences (agency) vs. public choice (democracy);

ii how to address the dilemmas of difference? This is about recognition of difference as either enabling vs. stigmatizing ( Norwich, 2013 ).

The second question about differences and differentiation will be dealt with first. In the capability approach thinking about equalizing capabilities is in terms of dignity. In these terms two ways of equalizing dignity can be considered from an educational perspective. One way of equalizing dignity is to respond to the individual functioning of all; this can be seen as about enabling learning for all. Another way is to avoid marking out students as different; this can be seen as avoiding the risk of stigma/humiliation. For example, some parents of children and young people are reluctant to seek out a diagnosis for their children, e.g., autism of ADHD, while others seek them out. These two ways of equalizing dignity can lead to a tension: differentiation as enabling but also risking stigma and devaluation, which can present a dilemma about difference/differentiation.

One way to connect how to address the dilemma of difference to conceptions of inclusion is in terms of the distinction which Cigman (2007) has made between “universal” and “moderate” inclusion. For Cigman, in “universal” inclusion, any marking out through separation of some children is to be avoided—through identification, different curricula, teaching and settings along a continuum of provision. This separation is regarded as a mark of devaluation and stigma; its avoidance is presented as a way of promoting respect. She contrasted this with “moderate” inclusion, that recognizes that promoting respect is also about identifying pupils’ personal strengths, difficulties and circumstances in a way that is enabling and not just stigmatizing. Based on this thinking there can be two broad responses to dilemmas of difference:

• it is possible to respond to the individual functional requirements (enabling route) and to avoid separation (avoid stigmatizing route); there are no dilemmas of difference representing a “universal” inclusion perspective.

• It is possible to some extent to respond to the individual functional requirements (enabling route) and to avoid separation (avoid stigmatizing route), but not fully: there are some dilemmas of difference which can be resolved to some extent. This represents a “moderate” inclusion perspective, what might better be represented as a reasoned and balanced inclusion.

This line of thinking shows how political-ethical questions about equalizing capabilities implicate dilemmas of difference in concepts of inclusion in inclusive education.

Deliberative democracy and citizens’ assemblies: personal vs. public choice

The second question arising from issues linked to the capability approach is how are “valuable functionings” identified? This has been framed as about the balance between personal preferences (agency) and public or social choice (democracy). In the United Kingdom (English) SEN/disability policy context, there has been over several decades a strong adoption of a “parental choice—provision diversity” approach—or what has also been called a neo-liberal approach ( Runswick-Cole, 2011 ). Here the choice is placed firmly with the individual. However, there has also been a persistent concern about United Kingdom (England) policy failure, which has been interpreted as reflecting an over-emphasis on personal preference rather than public choice ( Lehane, 2017 ). This has even been recognized more recently by policy makers, including the contemporary Department for Education Review of SEN/disability policy and practice ( Department for Education [DFE], 2022 ). This is a case of a Government having to confront the results of decades of policy which have not supported inclusive practices in a strategic way:

“…the need to restore families” trust and confidence in an inclusive education system with excellent mainstream provision that puts children and young people first; and the need to create a system that is financially sustainable and built for long-term success ( Department for Education [DFE], 2022 , p. 5).

However, this is not just about persistent policy failure over SEN/disability, it can be seen to also illustrate the democratic deficits in general educational and general social policy-making processes. SEN/disability inclusion cannot be detached from these other systems within the wider education system, such as school accountability, curriculum focus, and design, behavior management etc., because of their strong inter-connections. This is where Crouch’s (2011) Post-Democracy analysis is relevant in identifying how policy-making could better reflect stakeholder’s perspectives. This also connects to Felder’s (2018) examination of the meaning of inclusion, as encompassing communal and societal aspects and as being inherently social in its links to social intentions and actions. Felder goes onto to argue that the inclusion in inclusive education involves all stakeholders at all levels, from individuals to structural levels.

The implication of this analysis is that there needs to be more public deliberation and choice about inclusive education and a better balance between personal preferences and public choice. Following this argument Norwich (2019) has argued for an Educational Framework Commission, as a non-governmental policy initiative that uses representative citizen assemblies and other approaches to seek informed common ground between different stakeholders in policy making. This is one way to consider what is involved in a thick concept of inclusion in its links to democracy and as setting the context for research into inclusive education.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the above analysis about the scope, reach and limits of research on inclusive education. First, inclusive education is multi-dimensional, ambiguous and normative. This is related to the discussion about using inclusion as a thick or thin concept. The thick—thin distinction has been associated with the philosopher Williams (1985) in relation to ethical evaluations. Both thin and thick concepts involve evaluations, but thick concepts also have more complexity and descriptive content, while with thin concepts there is little sense of what is evaluated positively or negatively. In the case of inclusive education, the characteristic qualified by the term inclusive is positive without knowing much about the characteristic. For example, describing some education practice as “inclusive” reflects a thin use of the term, while qualifying the term “inclusive” as in “societal inclusion” or “curriculum inclusion in a separate setting” reflects more content and veers toward a thicker use of the concept. Kirchin (2013) has suggested that this thin-thick distinction is better represented as a continuum from thin to thick, which fits the use of the term “inclusive,” in these three examples, “inclusive practice,” “societal inclusion” to “curriculum inclusion in a separate setting.”

What makes inclusion in inclusive education a thick term is its multi-dimensionality which can also engender value tensions that need to be resolved. As argued above, this requires value clarification and some settlement about the balance of values, which is where deliberative democratic principles and processes have a crucial role. However, these processes can be Informed by empirical research, such as those summarized above. So, the answer in this paper to the question about the scope, reach and limits of research in inclusive education is that such research involves both empirical, methodological and evaluative matters. Educational research about inclusive education is not just empirical, it also involves value and norm clarification, a process which has been too often ignored. However, some empirical research in the field, such as the effects type summarized above, requires thin concepts of inclusion, as this is the only way that systematic empirical metrics can be set up for the kinds of large scale linking of variables. So, there is a place for both thin and thick concepts of inclusion in which they can interact. Thick concepts of inclusion can inform the foci for empirical research, while thin concepts used in empirical conclusions can inform how thick concepts develop through deliberative processes.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- ^ SEN Policy Research Forum, an independent network based in the United Kingdom, that aims to contribute intelligent analysis and the use of knowledge and experience to promote the development of policy and practice for children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities.

- ^ Sen indicated himself that the capability approach is an incomplete approach as it requires local democratic social choice in defining capabilities ( Sen, 2017 ).

Agran, M., Jackson, L., Kurth, J. A., Ryndak, D., Burnette, K., Jameson, M., et al. (2020). Why aren’t students with severe disabilities being placed in general education classrooms: examining the relations among classroom placement, learner outcomes, and other factors. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 45, 4–13. doi: 10.1177/1540796919878134

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

AuCoin, A., Porter, G. L., and BakerKorotkov, K. (2020). New Brunswick’s journey to inclusive education. Prospects 49, 313–328. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09508-8

Baumgart, D., Brown, L., Pumpian, I., Nisbet, J., Ford, A., Sweet, M., et al. (1982). Principle of Partial Participation and Individualized Adaptations in Educational Programs for Severely Handicapped Students. Psychol. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 7, 17–26.

Google Scholar

Booth, T., and Ainscow, M. (2011). Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools. 3 rd ed. Bristol: CSIE.

Cigman, R. (2007). A Question of Universality: inclusive Education and the Principle of Respect. J. Philos. Educ. 41, 775–793.

Crouch, C. (2011). The Strange Non-death of Neo-liberalism. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Dalkilic, M., and Vadeboncoeur, J. A. (2016). Re-framing inclusive education through the capability approach: an elaboration of the model of relational inclusion. Glob. Educ. Rev. 3, 122–137.

Department for Education [DFE] (2011). Support and Aspiration: A new Approach to Special Educational needs and Disability. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/support-and-aspiration-a-new-approach-to-special-educational-needs-and-disability-consultation (accessed July 6, 2022).

Department for Education [DFE] (2022). SEND Review: Right Support, Right Place, Right Time Government Consultation on the SEND and Alternative Provision System in England. London: DFE.

Dyssegaard, C. B., and Larsen, M. S. (2013). Evidence on Inclusion. Aarhus: Aarhus University.

Education Wales (2020). Routes for Learning: Guidance document. Available online at: https://hwb.gov.wales/api/storage/f4133444-0b1d-4f66-aa46-8f76edd09199/curriculum-2022-routes-for-learning-guidance-final-web-ready-e-130720.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022).

Felder, F. (2018). The value of Inclusion. J. Philos. Educ. 52, 54–70. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.12280

Fletcher, J. (2010). Spillover Effects of Inclusion of Classmates with Emotional Problems on Test Scores in Early Elementary School. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 29, 69–83. doi: 10.1002/pam.20479

Fuchs, D., and Fuchs, L. S. (1998). Competing Visions for Educating Students with Disabilities Inclusion versus Full Inclusion. Child. Educ. 74, 309–316. doi: 10.1080/00094056.1998.10521956

Gee, K., Gonzalez, M., and Cooper, C. (2020). Outcomes of Inclusive Versus Separate Placements: A Matched Pairs Comparison Study. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 45, 223–240. doi: 10.1177/1540796920943469

Gottfried, M. A., and Harven, A. (2015). The Effect of Having Classmates with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders and the Protective Nature of Peer Gender. J. Educ. Res. 108, 45–61. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2013.836468

Gray, P., Norwich, B., and Webster, R. (2020). Review of Research about the Effects of Inclusive Education: (longer version). Available online at: https://senpolicyresearchforum.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Inclusion-Review-final-longer-Feb-21.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022).

Hehir, T., Grindal, T., Freeman, B., Lamoreau, R., Borquaye, Y., and Burke, S. (2016). A Summary of The Evidence on Inclusive Education. Cambridge: Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Kauffman, J. M., Ahrbeck, B., Anastasiou, D., Badar, J., Felder, M., and Hallenbeck, B. A. (2021). Special Education Policy Prospects: Lessons From Social Policies Past. Exceptionality 29, 16–28. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2020.1727326

Kirchin, S. (2013). Thick Concepts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 9780199672349.001.0001 doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199672349.001.0001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lehane, T. (2017). “SEN’s completely different now”: critical discourse analysis of three “Codes of Practice for Special Educational Needs” (1994, 2001, 2015). Educ. Rev. 69, 51–67. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2016.1237478

National Council for Special Education [NCSE] (2019). Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society?. Trim: NCSE.

Norwich, B. (2013). Addressing Tensions and Dilemmas in Inclusive Education: living with Uncertainty. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203118436

Norwich, B. (2019). From the Warnock Report (1978) to an Education Framework Commission: A Novel Contemporary Approach to Educational Policy Making for Pupils With Special Educational Needs/Disabilities. Front. Educ . 4:72. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00072

Oh-Young, C., and Filler, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the effects of placement on academic and social skill outcome measures of students with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 47, 80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.014

Porter, G. L., and AuCoin, A., New Brunswick Department of Education Early Childhood Development (2012). Strengthening Inclusion, Strengthening Schools Report of the Review of Inclusive Education Programs and Practices in New Brunswick Schools. Fredericton, N.B: New Brunswick Dept of Education and Early Childhood Development.

Ruijs, N. M., and Peetsma, T. T. D. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educ. Res. Rev. 4, 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002

Runswick-Cole, K. (2011). Time to end the bias towards inclusive education? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 38, 113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2011.00514.x

Satherley, D., and Norwich, B. (2021). Parents’ experiences of choosing a special school for their children. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 1–15. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1967298

Sen, A. (1979). “Equality of What?,” in Tanner Lectures on Human Values , ed. S. McMurrin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Sen, A. (2017). Collective Choice and Social Welfare: An Expanded Edition. London: Penguin. doi: 10.4159/9780674974616

Sermier Dessemontet, R., Bless, G., and Morin, D. (2012). Effects of inclusion on the academic achievement and adaptive behaviour of children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 56, 579–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01497.x

Slee, R. (2018). Inclusive Education isn’t Dead, it Just Smells Funny. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429486869

Slee, R., and Weiner, G. (2001). Education Reform and Reconstruction as a Challenge to Research Genres: Reconsidering School Effectiveness Research and Inclusive Schooling. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 12, 83–98. doi: 10.1076/sesi.12.1.83.3463

Szumski, G., Smogorzewska, J., and Karwowski, M. (2017). Academic Achievement of Students Without Special Educational needs in Inclusive Classrooms: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 21, 33–54. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.02.004

Terzi, L. (2014). Reframing Inclusive Education: Educational Equality as Capability Equality. Camb. J. Educ. 44, 479–493. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2014.960911

UN (2006). Convention of the Rights of People with Disabilities , 24. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/ConventionRightsPersonsWithDisabilities.aspx#24 (accessed November 25, 2021).

UNCRPD (2016). Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: n Article 24: Right to inclusive education General comment No. 4 (2016) . Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CRPD/GC/RighttoEducation/CRPD-C-GC-4.doc (accessed November 29, 2021).

UNICEF (2017). Inclusive Education: Understanding Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_summary_accessible_220917_0.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022).

Warnock, M. (2005). Special Educational Needs: A New Look. London: Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain.

Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 12, 129–140. doi: 10.1080/17470216008416717

Williams, B. (1985). Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. London: Fontana.

Keywords : inclusive education, inclusion, research, effects, evaluations, thin and thick concepts

Citation: Norwich B (2022) Research about inclusive education: Are the scope, reach and limits empirical and methodological and/or conceptual and evaluative? Front. Educ. 7:937929. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.937929

Received: 06 May 2022; Accepted: 29 June 2022; Published: 15 July 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Norwich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brahm Norwich, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Dilemma of Inclusive Education: Inclusion for Some or Inclusion for All

Äli leijen.

1 Institute of Education, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Francesco Arcidiacono

2 Research Department, Haute Ecole Pédagogique BEJUNE, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland

Aleksandar Baucal

3 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

In this paper, we intend to consider different understandings of inclusive education that frame current public and professional debates as well as policies and practices. We analyze two – somewhat opposing – discourses regarding inclusive education, namely, the “inclusion for some” – which represents the idea that children with special needs have a right to the highest quality education which can be delivered by specially trained staff, and the “inclusion for all” – which represents the idea that all children regarding their diverse needs should have the opportunity to learn together. To put the two discourses in a dialogical relation, we have reconstructed the inferential configurations of the arguments of each narrative to identify how the two definitions contribute to position children with and without special needs and their teachers. The results show the possibilities to bridge the two narratives, with respect to the voices they promote or silence, the power relations they constitute, and the values and practices they enact or prevent.

Introduction

Inspired by social justice ideas, the Convention on the Rights of the Child ( UN, 1989 ) and the Salamanca Statement ( UNESCO, 1994 ), many European countries have developed policies and implemented practices to promote inclusive education ( Arcidiacono and Baucal, 2020 ; Nelis and Pedaste, 2020 ). Consequently, more children with special education needs 1 are nowadays learning with their peers in mainstream schools and the number of special schools has decreased. Although this is a trend in different countries in Europe and in the Global North, there are several challenges. Most notably, there is still no clear understanding of inclusive education. Researchers, policy makers, and teacher educators have diverse understandings ( Haug, 2017 ; Van Mieghem et al., 2018 ; Kivirand et al., 2020 ), which range from the idea that special education is itself a form of inclusive education, to the observation that all children are, for the majority, learning together in an inclusive setting ( Ainscow and Miles, 2008 ; Hornby, 2015 ; Kivirand et al., 2020 ). Magnússon (2019) has concluded that the “implementations, interpretations and definitions of the concept vary greatly both in research and in practice, between countries and even within them” ( ibid , p. 678).

These different discourses are present in several societies, but the debates are more heated in contexts which more recently have started to implement inclusive education practices, such as Eastern Europe and former Soviet countries ( Florian and Becirevic, 2011 ; Stepaniuk, 2019 ). One of the reasons for so many challenges in the latter context is the past experience of a strongly segregated educational system. This historical context is illuminated in the views of teachers, parents, and the general public.

In this paper, we will analyze two – somewhat opposing – discourses regarding inclusive education encapsulating two positions that are in the core of many current debates about inclusive education. The first one (“inclusion for some”) represents the idea that children with special needs have a right to highest quality education which can be best delivered by specially trained staff in a specialized and often segregated environment, while the second one (“inclusion for all”) represents the idea that all children regarding their diverse needs should have the equal opportunity to learn together in a regular education setting.

In this paper, we are going to put the two discourses in a dialogical relation. Through an argumentative analysis based on the reconstruction of the inferential configurations of arguments, we intend to identify how the two definitions contribute to position children (with and without special needs) and teachers, whose voices they promote and whose voices are silenced, what power relations they constitute, and what values and practices they enact or prevent. The possibility to map out the reasoning beyond these arguments is discussed as the starting point for bridging the existing conceptions about inclusive education. Prior to introducing the two narratives, we introduce briefly the background of inclusive education in Estonia which forms the context of the current study.

Inclusive Education in Estonia

Similarly to many Eastern European countries, Estonia has a long special education tradition, which is influencing acceptance of the principles and the actual practices of inclusive education. These principles have been established at the legislative level in Estonia since 2010, most notably the law states that students with special needs have the right for studying in their schools of residence with their peers ( Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act, 2010 , 2019 ). In accord with the changes in the legislative framework, the number of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools has increased; however, another phenomenon has appeared – the number of students enrolled in special classes in mainstream schools has also increased ( Räis et al., 2016 ). These special classes are often taught by teachers of special education and not by regular teachers. Although many school leaders understand the need for inclusive education, their main concern is a lack of availability of support specialists – including special needs teachers, speech therapists, and phycologists ( Räis and Sõmer, 2016 ). Although the expertise of support specialists is highly valued in Estonian schools and kindergartens, more and more teachers have recognized the importance of their own professional development related to supporting diverse learners. For example, the comparison of TALIS 2013 and TALIS 2018 survey data ( OECD, 2020 ) showed that teachers’ participation in professional development activities related to supporting diverse learners has significantly increased in Estonia and at the same time teachers indicated that training in this area is for them still the largest need for professional development. Consequently, diverse in-service training courses are available for teachers. An analysis of the course content at one of the major universities in Estonia providing teacher education showed that the core content of these courses has tended to focus on didactical methods of teaching students with special educational needs rather than on strategies of inclusive pedagogy. However, more recent in-service courses have emphasized social justice, possibilities for participation, and inclusive pedagogies as well (e.g., Kivirand et al., 2021 ). This brief overview illuminates that very different perspectives and practices are present in Estonia. We will explore these in more detail in the next sections.

Two Discourses of Inclusive Education

Inclusion for some.

There have been several articles published in 2020 in Estonian national newspapers arguing that inclusive education is a dream or ideology that does not take into account actual circumstances of reality. In one of such articles ( Ehala, 2020 ), a university professor, who regularly writes about education, cites a recent study conducted in Estonia on the added value of education on children’s cognitive abilities. The study showed that 80% of the children’s knowledge and skills can be explained by individual abilities and home background, and only 20% by the influence of school. The professor argued that children with physical disabilities could be included, but it is problematic to include children who have been raised according to very different principles or who have significant cognitive disabilities. He specified that inclusive education would only be possible in societies which are very homogeneous, most importantly regarding child raising practices and family values. This would result in a situation where there are few differences between children’s behaviors and are used for similar norms and regulations. He pointed out as: “Inclusive education is a mirage created by our sense of justice, but its implementation puts young people in a learning environment that is not in line with their home preparation and developmental needs. They are just too special and different so that everyone could learn together in a way that no one suffers.” He concluded that we simply need different kinds of environments for different children.

Many of these ideas are also pointed out by some teachers. In 2019, a new educational strategy was prepared for Estonia and in this process, several meetings were held in different places across the country. Many teachers were critical regarding the recent policy reform related to inclusive education. On the one hand, teachers are concerned about the learning process and outcomes of the regular children and, on the other hand, their own preparation to support students with special needs. Working with special needs students requires specialized knowledge and expert skills, which many teachers simply do not have. Similar to these views, a group of master students wrote an article in a national newspaper in June 2020 ( Kupper et al., 2020 ) where they stated that although they support the idea of inclusive education, it is only justified if it is carefully organized and sufficient support is available. They also added that inclusive education is certainly not suitable for students with more severe special needs. They point out as: “Inclusion may not be effective in case the teacher does not receive enough support and guidance regarding how to work with a special needs student and the rest of the class at the same time. If, figuratively speaking, the teacher’s strength does not overcome the situation, then the increase in behavioral problems, drop-out rates and developmental delays are real dangers.”

Moreover, this article also shed light into the perspective of parents of special needs students. They argued as: “A familiar and close-to-home school with a teacher assistant or support specialist does not outweigh the assurance that the child’s safety and well-being is guaranteed throughout the day and is cared for by a sufficient number of professionals.” Moreover, “Studying at a school close to home may not always be possible if the child needs a much more complex service due to his or her situation, including, for example, special therapies and additional activities. If such a solution is not offered during the school day, parents must find the time and opportunity, usually at the expense of working hours, to provide the necessary service to the child. Thus, the difficulty of the whole situation lies with the parents, who, despite the child’s special needs, must be able to maintain optimism, offer equal care and love to the other children of the family in other words, try to live as normal a life as possible while maintaining the ability to work, good relations with the employer and income and one’s own emotional balance.”

In brief, all these perspectives argue that the development of different students will benefit from specialized learning environments and special teachers who have good expert knowledge and skills for preparing specific educational experiences for maximizing each student’s individual potential. Similar viewpoints have also been presented in the international literature: for example, Kauffman and Hornby (2020) criticized inclusive education ideology and leading scholars in the field for the unrealistic claims regarding its implementation and outcomes. They concluded as: “Appropriate instruction is by far the most important task of education for all students, including those with disabilities. Making appropriate instruction a reality for all students requires special education, including teachers with special training, rather than a generic, ‘one size fits all’ or all-purpose preparation” (p. 10).

Inclusion for All

In contrast to voices arguing for creating different learning environments for different children, scholars, policy makers, teachers, and parents in favor of inclusion for all stress, in different talks and articles, that all children in a society should have an equal right to get adequate opportunities to develop wellbeing, agency, identities, and competences in order to become capable to participate fully and equally in the society ( UNESCO, 1994 ; Ainscow and César, 2006 ; Cigman, 2007 ; Felder, 2019 ). This objective cannot be reached if some children are educated in a segregated context.

Inspired by social constructivist approaches to learning, teacher educators supporting inclusive education argue that child development depends not only on inherited capacities, but it is also constructed by shared social values, access to educational institutions, technologies (including assistive technologies), and other relevant social resources as well as quality of support provided to the child and opportunities to participate fully and equally in a community.

Teacher educators and policy makers would agree that it is true that current educational systems (schools, teachers, initial education of teachers, practices, technologies, teaching and learning materials, etc.) in many countries have been established based on an assumption that “regular” education, schools, and teachers should work only with “typical” children and other children need to be educated in a specially designed and segregated environment, that is, “special” education ( Carrington, 1999 ; Croll and Moses, 2000 ; Dyson et al., 2002 ; Radó et al., 2016 ; Zgaga, 2019 ; Koutsouris et al., 2020 ). However, they would argue that in such an environment, children cannot develop a sense of belonging nor can become full members of the society because of marginalized status and limited opportunities to grow with others ( Freeman and Alkin, 2000 ; Farrell, 2010 ; Koller et al., 2018 ). Moreover, in a special education, setting relationships, practices, and technologies tend to be adapted to their constraints instead of being designed to enable children to fully participate in education and society in spite of constraints. Similarly, parents, teachers, and kindergarten/school leaders favoring inclusive education in Estonia would argue for social justice ideas: the importance of growing up within the community and learning at a kindergarten/school close to their home. A father of a child with speech difficulties, who was contacted by an author of this article and asked why he favored his child attending a regular kindergarten instead of a specialized kindergarten, pointed out as: “I can’t distinguish my child, who has special (or rather specific) needs, from any other child. How can I agree with her being placed in a school which labels her directly and indirectly as a person who does not fit the norm? Especially when attending kindergarten, she is as special and as normal as every other child who she plays with and a child who plays with her. This should be the norm for any healthy development of a child.” Similarly, a teacher and master student ( Konetski-Ramul, 2021 ) and a head of support specialists services ( Labi, 2019 ) have argued for inclusive education in articles published in the national teachers’ newspaper in Estonia. In these articles, the authors urged for not separating students with special needs easily to special classes or special schools, e.g., Labi (2019) pointed out as: “If today we separate one quarter of children for fear that their involvement could negatively affect the well-being of the other three quarters of children, then as adults there are people in the labor market, in families, or even in the queue at the store, who cannot cope with each other. It is more sustainable to grow together, learn from each other and cope with each other throughout the school journey.” Many parents of special needs children would also argue that the most important goal for them is for their children to adapt to society and learn to live with other people. To illustrate this idea, a mother of a young child with multiple disabilities pointed out during a public speech in Estonia that her family’s “goal is to support him so he would become a taxpayer.”

In order to have an equal opportunity, all children need to be educated in regular education that have conditions, capacities, and resources to be able to adapt to the children needs, capacities, and constraints. Following this, in a case when a school, teachers, discourses, practices, and technologies are not aligned with the needs of some students, it cannot be an acceptable reason for the exclusion of the child, but for adapting the education to the child and his/her learning and developmental needs ( Farrell, 2010 ; Arcidiacono and Baucal, 2020 ).

The majority of Estonian teachers has adopted learner-centered views about education as reported in international comparison studies, such as TALIS 2013, 2018, and a smaller group has also learned to implement these in practice (many Estonian teachers are still rather traditional and subject-oriented in their teaching practice; OECD, 2014 , 2020 ; see also Leijen and Pedaste, 2018 ). Teachers who have accepted the child-centered view might not consider a class as a unified mass, instead they might perceive children anyway as special and different, notice variety, individual differences and adapt their teaching accordingly ( Breeman et al., 2015 ). Following, adapting their teaching for a child with special needs would not be so different from any other adaptation of teaching for the child’s needs and interests. While discussing the possible challenges of inclusive education during an in-service course taught by the first author of the paper in autumn 2019, a teacher pointed out that “it is very interesting and positively challenging to teach a group of students with a large variety. These are (my) favorite classes.” This indicates that teachers might find diversity and variety enriching for themselves as professionals.

Goal of the Paper

The aim of this paper is to show, through the conceptual analysis of the two above-mentioned discourses, that it is possible to put these two narratives in a dialogical relation to identify their contribution to position children (with and without special needs) and teachers with respect to the voices they promote or silence about inclusive education, the power relations they constitute, and the values and practices they enact or prevent.

Materials and Methods

We propose an analytical approach based on the argumentum model of topics (AMT) that aims at systematically reconstructing the inferential configuration of arguments; namely, the deep structure of reasoning underlying the connection between a standpoint and the argument(s) in its support ( Rigotti and Greco Morasso, 2009 ). The general principle underlying the reconstruction of the inferential configuration of argumentation is that of finding those implicit premises that are necessary for the argumentation to be valid.

In the AMT, two fundamental components should be distinguished when bringing to light the inferential relation binding the premises to the conclusion of an argumentation. First, an argument envisages a topical component, which focuses on the inferential connection activated by the argument, corresponding to the abstract reasoning that justifies the passage from the premises (arguments) to the conclusion (standpoint). The inferential connection underlying the argument is named with the traditional term maxim. Maxims are inferential connections generated by a certain semantic ontological domain named locus. Second, an endoxical component, which consists of the implicit or explicit material premises shared by the discussants that, combined with the topical component, ground the standpoint. These premises include endoxa, i.e., general principles, values, and assumptions that typically belong to the specific context, and data, basically coinciding with punctual information and facts regarding the specific situation at hand and usually representing the part of the argument that is made explicit in the text ( Rigotti and Greco Morasso, 2011 ). Despite its particular concern for the inferential aspects of argumentation, the AMT accounts not only for the logical aspects of the argumentative exchange, but also for its embeddedness in the parties’ relationship, and thus proves to be particularly suited for the argumentative analysis of public discourses.

In the present paper, we refer to the AMT to reconstruct the inferential structure of some arguments proposed by the two above-mentioned discourses, i.e., the type of reasoning underneath the arguments. In this sense, the model is assumed to be a guiding framework for the analysis, since it provides the criteria for the investigation of argumentative positions and for the identification of different components of each discourse. It is used to highlight points of contention and dialogue, as well as the explicit and implicit arguments advanced by the involved sustainers of the two narratives. The application of this analytic method in the study of public discourses, such as the role of inclusive education, is assumed to reinforce the possibilities of understanding how people discursively position themselves as involved partners in the management of the selected issue, namely, inclusive education.

According to the AMT, the following analytical components must be identified as: the maxim on which the argumentation is based and the relative locus at work; the endoxon, i.e., the premises shared by the discussants, and the datum, i.e., the punctual information and facts regarding the specific situation at hand (usually representing the part of the argument that is made explicit in the text) to which the argument is linked. The results of the AMT’s reconstruction will be represented through graphical tools adopted to show the above-mentioned components.

Generally speaking, the different arguments used by the parties can be viewed in terms of a constellation of features ( Goodwin, 2006 ), including various interactional structures connected to aims, perceptions, directives, accounts, etc. In the present paper, we will limit our conceptual analysis of two narratives to some elements that are essential for the aim of the study, although we are aware that this is a partial choice. Accordingly, the locus at work for the maxims will not appear in our schemes and only the arguments sustaining the main ideal view of each narrative and the presumed positions associated with the selected arguments will be presented.

In the next sections, we propose two examples of AMT based on selected arguments for each discourse.

Reconstructing the Inferential Structure of the First Discourse Argument

The first discourse (“inclusion for some”) proposes as a standpoint that students with special needs require specialized educational settings. The argument advanced to sustain this position is that specialized settings are accommodating to the student’s capacities and needs.

Figure 1 shows the representation of such an argument based on the AMT. On the right hand of the diagram, the inferential principle, i.e., the maxim, on which the argumentation is based is specified as: “to provide a beneficial property to the student, it is required to adopt a system that guarantees this beneficial property.” The AMT representation allows consideration of the contextual premises that are implicitly or explicitly used in argumentation. This may be found on the left hand of the diagram, where a second line of reasoning is developed that supports the former one. This is why the first conclusion on the left becomes the minor premise on the right. In this way, the crossing of contextual and formal premises that is characteristic of argumentation is accounted for in the AMT. The endoxon refers in this case to common knowledge about the main idea of the accommodation principles: “To accommodate to the student’s capacities is a beneficial property.” The datum (“Specialized settings are accommodating to student capacities”) combined with the endoxon produces the conclusion that “Specialized settings have beneficial properties.”

AMT-based reconstruction of the first discourse argument.

In the first discourse, if the accommodation is considered beneficial for a student with special needs, and if specialized settings are recognized as environments that can guarantee a process of accommodation, then it is valuable to require that students with special needs should be placed in specialized settings.

Reconstructing the Inferential Structure of the Second Discourse Argument

The second discourse (“inclusion for all”) proposes as a standpoint that all students require regular educational settings. The argument advanced to sustain this position should be summarized as follows: Regular settings offer equal opportunities to all students. Figure 2 shows the representation of such an argument based on the AMT.

AMT-based reconstruction of the second argument.

On the right hand of the diagram, the inferential principle, i.e., the maxim, on which the argumentation is based is specified as: “if the offer of equal opportunities is an important educational goal, and there is a way to guarantee such a goal, then this way should be adopted.” Concerning the contextual premises that are implicitly or explicitly used in argumentation, the endoxon refers to common knowledge about the main idea of the educational goals: “Education should offer equal opportunities to all students.” The datum (“Regular settings offer equal opportunities to all students”) combined with the endoxon produces the conclusion that “All students require regular educational settings.”

The discourse indicates that if offering equal opportunities to all students (by exposing them to similar conditions) are considered an important educational goal, and if regular settings are recognized as environments that can guarantee to offer equal opportunities, then it is valuable to require that all students be placed in regular settings.

Implicit in Two Discourses

The models referring to the two discourses about inclusive education are showing in both cases reasonable arguments advanced to sustain the positions and the perspectives they intend to promote. For each discourse, accountable elements are proposed to show the pertinence of the approach and to sustain the idea of education that is considered as adequate for society.

The two discourses position the children as the main key-players in the educational endeavor: In fact, inclusive education should sustain the requirement for appropriate settings (special and regular) that are able to allow students (with and without special needs) to develop their capacities and to become members of the society. In this sense, the two discourses share a similar preoccupation and aim to play in the service of children’s development. However, it is also true that both discourses promote reasons that seem to position the children within different frames, for example, in terms of temporality. In fact, the first discourse (“inclusion for some”) focuses on the need to guarantee a process of accommodation to the children’s needs in order to guarantee a system that allows students to develop their capacities. In this sense, a short-term perspective is promoted, because the goal behind the sustained discourse is to be able to act adequately in the “here and now” of the contingent situations. By contrast, the second discourse (“inclusion for all”) advances the idea that offering equal opportunities to all students constitute the main goal of education. In this sense, a long-term perspective is promoted in terms of capacity to ensure the conditions that will guarantee the future realization of students as full members of the society. These elements, connecting the two discourses along a temporal dimension, will be discussed in the next section of the paper, as well as the implications in terms of positions that children and teachers should take according to their voice, the power relations that are connected to this, and the values that are enacted or prevented.