Error: User registration is currently not allowed.

Username or Email Address

Google Authenticator code

Remember Me

Lost your password?

← Go to BMJ

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2023

The factors associated with teachers’ job satisfaction and their impacts on students’ achievement: a review (2010–2021)

- Kazi Enamul Hoque 1 ,

- Xingsu Wang 1 ,

- Yang Qi 1 &

- Normarini Norzan 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 177 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The success of any educational organization depends heavily on the effectiveness of its teachers, who are tasked with transferring knowledge, supervising students, and enhancing the standard of instruction. Teachers’ job satisfaction has a significant impact on the lessons they teach since they are directly involved in transferring knowledge to students. In order to determine the effect of teachers’ job satisfaction (TJS) on students’ accomplishments, the researchers sought to analyze the empirical studies conducted over the previous 12 years (SA). To determine the characteristics that link to instructors’ job satisfaction and their effect on students’ achievement, thirty-two empirical studies were examined. The analysis of world-wide empirical research findings shows four types of results: (i) In some countries, teachers’ job satisfaction is low, but students’ achievement is high (Shanghai, China, South Korea, Japan, Singapore) (ii) In some countries, teacher job satisfaction is high, but student achievement is low (Mexico, Malaysia, Chile, Italy). (iii) In some countries, teachers’ job satisfaction is high, and so is student achievement (Finland, Alberta, Canada, Australia). (iv) In some countries, teacher job satisfaction is low, which has a negative impact on student achievement (Bulgaria, Brazil, Russia). In sum, irrespective of countries, highly satisfied teachers give their best to their students’ success, not only by imparting knowledge but also by giving extra attention to ensure the better achievement of each student. The review of this study makes it even more worthwhile to reflect on the need to avoid stereotypical considerations and assessments of any objective presentation of the phenomenon and to reflect more deeply on the need to assess the validity of the relationship study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Influence of motivation on teachers’ job performance

Job satisfaction and self-efficacy of in-service early childhood teachers in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era

Exploring the employment motivation, job satisfaction and dissatisfaction of university English instructors in public institutions: a Chinese case study analysis

Introduction.

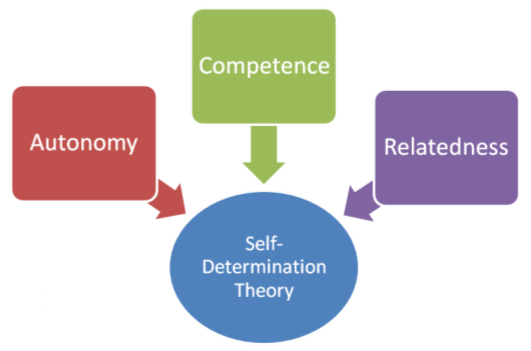

Teachers are the main part of the school education system. The factors affecting students’ achievement (SA) should be multifaceted. Among them, teachers are one of the important factors that affect students’ academic performance (Ma, 2012 ). Teacher job satisfaction (TJS) refers to teachers’ satisfaction with their current work, which can be divided into internal satisfaction and external satisfaction (Wang, 2019 ). TJS inquiry and analysis can help managers not only comprehend teachers’ professional attitudes and avoid burnout but also provide some guidance for management decision-making. Improving TJS will assist instructors in maintaining a high level of passion and enthusiasm for their profession for a long time, allowing them to play even better in the lesson and ensuring consistent teaching quality (Zong, 2016 ). Teachers must have proper work satisfaction in order to be fully ready to transmit knowledge and skills important for learners to develop in SA. Teachers have been revered as “nation builders”. More specifically, teachers who teach in colleges and train students into elites and have talents in different disciplines are the key to a nation. Low TJS may lead to lower levels of education (Borah, 2016 ).

Many studies show that TJS has a significant positive correlation with job performance. As an example, Hayati & Caniago ( 2012 ) found that higher job satisfaction is conductive to higher job performance, while Ejimofor’s ( 2015 ) finding shows triadic relationships in which it indicates that TJS improves teaching quality, and teaching quality has the direct effect of improving students’ quality. One of the most important topics in every academic organization is TJS and SA. TJS not only increases productivity but also helps promote a productive teaching and learning environment. Based on this, both school administrators and the government should give more attention to meeting the needs of teachers to improve their motivational level to achieve educational goals so as to improve student academic performance (Ihueze et al., 2018 ). Surprisingly, though some researchers did not find a substantial link between TJS and SA (Ejimofor, 2015 ; Borah, 2016 ), the intuition and popular expectation is that TJS affects SA significantly and directly (Fisher, 2003 ). Moreover, Lopes & Oliveira ( 2020 ), utilizing information from the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey, demonstrated that teacher job satisfaction is a vital element of teachers’ and schools’ performance as well as students’ academic and educational attainment (TALIS). They also discovered that aspects of interpersonal relationships are the most effective predictors of job happiness. They advised schools to improve by addressing interpersonal problems, especially in the classroom, where the majority of perceived job satisfaction tends to reside. The findings demonstrated that, (1) among the personal traits of teachers, teacher efficacy had significant effects on job satisfaction (You et al., 2017 ). As the factors affecting teachers’ job satisfaction vary depending on the context of different countries, this review included studies from different regions to give a comprehensive scenario of findings based on different regional factors. The review results have revealed the associated factors of teachers’ job satisfaction and their impacts on student achievement. The findings can be the subject of further exploration. The review study set out to accomplish the following objectives:

Objectives:

to find whether teachers’ job satisfaction (TJS) has an impact on student achievement (SA)

to find the factors that have a positive impact on TJS and SA

to find the factors that influence the effect of TJS on SA and that manifest differently in different countries

Theoretical background

Between 2010 and 2021, the number of studies examining the impact of TJS on SA increased significantly.

Conceptualization of teachers’ job satisfaction

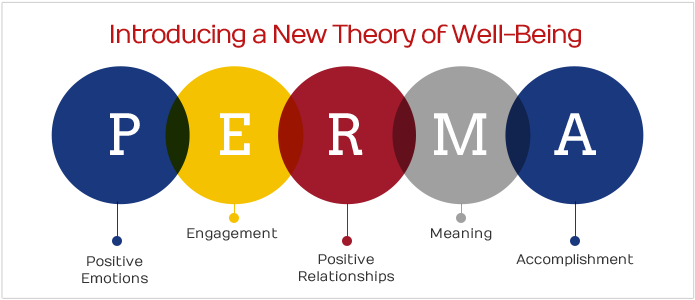

Job satisfaction is one of the important topics in the fields of occupational psychology, organizational behavior, and human resource management to explore employee productivity and organizational effectiveness (Fisher, 2003 ). With the development of humanistic thinking and the concept of lifelong education, this concept has been generally accepted by people, and the academic community has increasingly paid attention to the work-related emotional experiences of different professional or occupational groups such as teachers, nurses, etc.

Generally speaking, TJS refers to a teacher’s overall emotional experience and cognitive expression of their occupation, working conditions, and state. The international community generally believes that, as a variable of emotional attitude, TJS itself not only covers different dimensions but, more importantly, TJS has an important and direct impact on teachers’ enthusiasm and commitment to teaching. Daily work efficiency and effectiveness are also powerful predictors of SA. In addition, from the perspective of organizational commitment, improving TJS is an important way to enhance teachers’ sense of identity and belonging to the school, as well as to improve teachers’ professional attractiveness.

From the perspective of logical inference, according to the important phenomenon of the mentoring effect in the rise of talent chains and talent groups in the history of scientific development, as well as the practical experience that “the greatest happiness of teachers comes from the extraordinary achievements of students,” and even the word “teacher” often used when praising teachers, judging from the phrases such as “famous teachers produce master apprentices” and “peaches and plums fill the world,” in practical work, SA should also be one of the important sources of TJS (Wang & Zhang, 2020 ).

Factors affecting the teachers’ job satisfaction

Different studies have used different elements that have direct, indirect, or even no impacts on the job satisfaction of teachers. In their research on college teachers’ job satisfaction, Shi et al. ( 2011 ) revealed that work treatment, job pressure, leadership behavior, gender, age, etc. have more or less influence on the job satisfaction of college teachers. Existing research usually divides the factors that affect TJS into four levels: individual, school, work, and others. The influencing factors at the individual level can be grouped into objective factors and subjective factors. Among them, objective factors include teachers’ educational background, teaching years (experience), gender, professional title, monthly income and workload, teaching subjects, etc.; subjective factors include occupational preference and work engagement.

The two main influencing variables at the school level are students and management. While the management aspect comprises the institutional culture of the school and student management, the student aspect includes the student’s learning environment. The professional growth environment, work pressure, learning exchange possibilities, etc. are examples of workplace factors. The location of the school (eastern, central, or western) and whether it is located in an urban or rural area are examples of other levels (Beijing Normal University Teachers’ Labor Market Research Group et al., 2021 ).

These elements can be categorized into three groups when considered collectively: the elements of the college professors themselves, the elements of the institutions, and the level of compatibility between individuals and roles. The author’s research focuses on the connection between these three variables and college professors’ job satisfaction (Shi et al., 2011 ).

Professional title, educational background, and job satisfaction are among the factors that teachers can control for themselves, but these variables have very weak correlations and cannot be used as explanatory variables in the regression equation. Age, on the other hand, has a weak correlation with job satisfaction but can be used as a variable to explain job satisfaction. Salary level is the school component that has the greatest impact on TJS. The primary output that teachers receive from the organization is compensation, which is also a key component that teachers demand from the organization. The degree of alignment between instructors’ expectations and their compensation is the most significant element determining TJS in terms of the matching of people to roles.

Student achievement

Defining a student’s grades is not an easy task. The most common metric of achievement is undoubtedly student performance on achievement exams in academic disciplines like reading, language arts, math, science, and history. The quality of schools and teachers, students’ backgrounds and situations, and a host of other variables all have an impact on academic attainment (Cunningham, 2012 ). The researchers looked at academic levels, achievement gaps, graduation and dropout rates, student and school development over time, and student success after high school.

Academic achievement is the ability to complete educational tasks. Such achievements can be general or topic-specific. Academic achievement refers to students’ scores in courses, curriculums, courses, and books that they have studied, expressed in the form of marks, percentages, or any other scale of marks (Borah, 2016 ). It is important to highlight that academic performance encompasses not only students’ achievement in tests and exams, but also their participation in social events, cultural events, entertainment, athletics, and other activities in academic institutions and organizations.

Conceptual framework of the study

How to improve the academic performance of students is a popular topic in the field of education. After all, the purpose of education is to train students to become talents in society. Between 2010 and 2021, scholars from many different countries studied the relationship between TJS and SA. Many scholars’ studies have shown that there is a significant positive correlation between TJS and SA (McWherter, 2012 ; Crawford, 2017 ; Andrew, 2017 ; Iqbal et al., 2016 ). In these studies, the effects of TJS on SA were investigated, suggesting that it is fairly common in the literature to study the relationship between the two as a theme (Ejimofor, 2015 ; Borah, 2016 ).

Specifically, some districts have high SA but lower TJS than average schools. While some districts had high TJS, this did not improve SA. Therefore, it makes sense to understand the findings of these studies as a whole. What’s more, it is necessary to sort out the reasons for this divergence among numerous studies and make comparisons. The following questions serve as a guide for this study’s analysis of the findings in the literature on the effect of TJS on SA.

Does research show that TJS has an impact on SA?

What factors will have positive impact on tjs and sa.

What factors influence the effect of TJS on SA that manifests differently in different countries?

By examining previous research, this work seeks to characterize teacher motivation and assess the evaluation criteria and processes that account for student performance. The research method is systematically summarizing and analyzing based on a literature review, which helps us research and analyze the topic from a dialectical perspective. This study refers to the model of PSALSAR. The process of selecting documents starts with analyzing the topic, searching and classifying relevant documents, screening relevant documents from different sources according to the selection criteria, and finally extracting the most relevant documents for sorting out. Analysis (Bearman et al., 2012 ). The scope of this review also followed four criteria as outlined in the review work of Wayne & Youngs ( 2003 ).

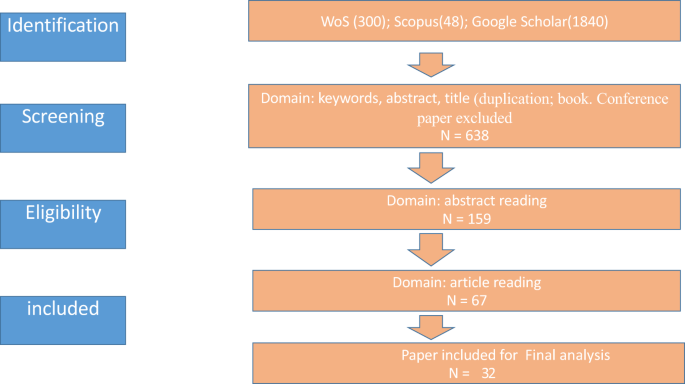

Data sources

The data for this literature review was extracted from three major data sources: Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and HowNet. The review intended to take into account all recognized and relevant sources reporting on studies that are in English and falls within the duration of the study, which is a 12-year period from 2010 to 2021. The aim of the search is to locate all appropriate literature without expanding the search too much and retrieving a huge number of unrelated results. After applying an analytical inclusion/exclusion criterion to the 721 papers that were found, 32 papers were found to be applicable to the study’s objectives.

Data screening

The databases were searched using the following terms: “career management of teachers,” “teacher job satisfaction,” “student achievement,” and “teacher job satisfaction and student achievement.”

There is much literature on the relationship between TJS and SA, many of which use TJS as a mediator, or TJS is just one of the variables to promote SA. Since the focus of this review was on the impact of TJS on SA, the literature search consisted of two phases to ensure that all relevant literature on the relationship between the two was included. In the first phase, which focused on TJS, the following search terms were used: “teacher job satisfaction”, “teacher work satisfaction” and “teacher satisfaction”, combined with the search term “SA”. In the second stage, the focus is on the effect of TJS on the SA selected from the first stage choices. After screening for keywords and selecting the year interval as 2010–2021, 26 documents were finally extracted for research. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based framework that clearly defines the bare minimum of items to be included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2009 ).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In order to check on the quality and validity of the data obtained, the most recent journals available on the topic were chosen. Also, a high priority was given to reading the findings and extracts of every journal before it was selected for review. Literature analysis adopts the selected research selected by narrative methods so that the author can understand the literature and find the mode by carefully reading and interpreting the research results (De Rijdt et al., 2013 ).

Next, each article is completely reread to determine the important part. Based on the content analysis method, the paragraphs of important information containing the answer to the hypothesis research question are encoded. In this literature review, as mentioned in an earlier section, the PRISMA is applied to the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. The table below depicts the details (Table 1 ).

The review results of 32 empirical studies have revealed the following answers to formulated research questions. The answers are organized according to research questions.

From 2010 to 2021, most studies from different countries have shown that TJS has a positive impact on students SA (McWherter, 2012 ; Crawford, 2017 ; Farooqi & Shabbir et al., 2016 ) The morale of teachers is closely related to the academic achievements of students (Sabin, 2015 ). This is because when the teacher is dissatisfied with their work, they will transfer it to students in many ways, including the absence of classes. When this happens, students will suffer, and their academic performance will inevitably be negatively affected.

The research results also show that the more teachers believe that teaching is a valuable occupation, the more satisfied they are (Armstrong, 2009 ), and the better the students’ outcomes. A study in two sub-Saharan African nations examined the degree of teacher satisfaction in Uganda and Nigeria, its causes, and how it affects the quality of instruction and learning (Nkengne et al., 2021 ). According to research, teachers who are satisfied with their jobs are more likely to teach effectively, which should help their pupils learn more in the classroom. In order to make employees play a greater role, the work itself must have satisfactory characteristics. If it is interesting, it has good income and work safety. A teacher with high work satisfaction usually puts more effort into teaching and learning (Ihueze et al., 2018 ). However, whether it is based on the conclusions of existing mainstream theoretical research or on practical experience, low job satisfaction will not only affect teachers’ teaching enthusiasm but also cause teachers to have a teaching attitude problem of “not happy to teach”, as a result, it may even lead to the problem of “poor teaching” ability and ultimately have a negative impact on students’ academic performance; at the same time, it will also have a negative effect on the organizational commitment of in-service teachers and the professional attractiveness of teachers (Wang and Zhang, 2020 ).

The results of several earlier investigations likewise show the opposite. The intuition and general expectations of the work satisfaction of teachers will affect the students’ grades (Fisher, 2003 ). TJS lacks a significant relationship with student grades, which is in line with the findings of Banerjee et al. ( 2017 ). According to their longitudinal study of young children between kindergarten and fifth grade, student reading growth has no association with teacher job satisfaction, but there is a slight but favorable relationship between the two. Although this seems to be a violation, it is consistent with the previous 41 research (Iaffaldano & Muchinsky, 1985 ; Fisher, 2003 ). Studies lack significant relationships between TJS and children’s academic achievements (Ejimofor, 2015 ). The relationship between TJS and SA can be ignored, which is to say that teachers’ job satisfaction has no significant impact on SA (Borah, 2016 ). Despite such findings, most of the scholars agree with the notion that job satisfaction concerning school teachers reflects their strong motivation towards their dedication to students’ performance (Manandhar et al., 2021 ).

TJS has a positive impact on the quality of education; therefore, affecting teacher job satisfaction can affect the quality of education. However, because multiple factors have a significant effect on TJS and SA, not all things that improve TJS also improve academic performance. In many circumstances, the aims of increasing job happiness and enhancing student accomplishment are antagonistic rather than complimentary (Michaelowa, 2002 ).

System control factors and incentive structures, in particular, due to a complete lack of job protection, have been found to have a significant positive impact on teacher performance, although they tend to be strongly opposed by the instructors involved. According to a study (Tsai & Antoniou, 2021 ) conducted in Taiwan with 113 teachers and 2,334 students to examine the relationships between teacher attitudes toward teaching mathematics, teacher self-efficacy, student achievement, and teacher job satisfaction, teacher attitudes toward teaching mathematics, efficacy in the classroom, and student achievement in mathematics could, to some extent, explain variations in teacher job satisfaction. The majority of the variation in teacher job satisfaction, which may translate into improved teacher efficacy and student achievement, was explained by teacher attitudes about teaching mathematics. It suggests that improving the quality of education for children is a complex process for which variables like instructors’ attitudes, their level of self-efficacy, and their pleasure and satisfaction at work may be responsible (Khalid, 2014 ). According to a study by Rutkowski et al. ( 2013 ) on 81 elementary school teachers from a sizable metropolitan school district in the United States, the PD program improved teachers’ pedagogical topic knowledge and subject-matter expertise. The teachers that participated in the professional development program showed a greater level of topic and instructional strategy understanding.

In fact, only a few variables had a clear positive effect on both goals. One was related to classroom equipment, which had a clear positive effect on teachers’ well-being. By accessing the material support of a supportive and satisfying working environment, teachers are more likely to be more actively involved in their teaching activities, which in turn is an important factor in how this leads to the creation of relevance for students’ teaching practice (Benevene et al., 2020 ). Among the device variables, many variables do not have any significant effect on SA and therefore do not even appear in the regressions. However, the situation is different for students’ teaching materials, which are highly correlated with SA and positively correlated with teacher job satisfaction. Therefore, improving the supply of textbooks is certainly a relevant policy option (Hee et al., 2019 ). In terms of class size, however, it does have a significant impact on teacher work satisfaction (Hee et al., 2019 ). TJS can be improved by reducing class size. Increasing class size is clearly the best answer to high student numbers for both teachers and kids. The disadvantages of double-shifting are so severe that they are applicable to classes of up to 100 pupils. Teacher efficacy has been shown to correlate with the presence of classroom processes and procedures, and the presentation of good classroom processes may contribute to better outcomes for students (Perera et al., 2022 ). At the same time, good teacher efficacy will also enable teachers to provide more effective pedagogical support, resulting in better outcomes for students in teaching and learning.

The commonly held belief that low salaries and large class sizes are the key reasons for low teacher job satisfaction and low SA has no support in this study. This had no discernible impact on SA. As a result of this research, an extraordinarily costly endeavor to enhance teacher compensation does not appear to be a suitable policy option in general.

What factors influence the effect of TJS on SA that manifest differently in different countries?

In their study, Dicke et al. ( 2020 ) found that the working context item was associated with student accomplishment for both teachers and principals; however, only the general and working environment factors of teacher job satisfaction were related to the disciplinary climate observed by students. International Student Evaluation Projects (PISA) and the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) found that in countries and regions with outstanding academic performance of students, their teachers showed lower work satisfaction (OECD, 2016 ; TALIS, 2013). For example, for two consecutive years in the PISA test, it is hailed by the World Bank as Shanghai, China, which has the highest education system in the world, shows that the teacher’s work satisfaction is significantly lower in the Talis 2013 survey results (Liang et al., 2016 ). In fact, Shanghai is not a special case. PISA (2015) data shows that, as a whole, despite the outstanding performance of students, the work satisfaction and occupational satisfaction of East Asian countries and regions are lower than the international average (Chen, 2017 ). At the same time, in those countries or regions that are less ideal in the PISA test, their teachers’ work satisfaction and occupational satisfaction are often significantly higher than the international average (Wang and Zhang, 2020 ). Data from 1,539 teachers at 306 secondary schools in the two Indian metropolises of New Delhi and Kolkata supported the notion that instructional leadership has indirect effects on teaching and learning and that the social and affective climate of the classroom has direct effects on teacher job satisfaction, which in turn affects student achievement (Dutta & Sahney, 2016 ). De Vries et al. ( 2013 ) conducted a study on teacher professional development (PD) in the context of inquiry-based science education (IBSE). The study aimed to investigate the effects of a long-term PD program on teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. A total of 62 primary school teachers from the Netherlands participated in the trial and were randomized to either the PD program or a control group. Surveys, interviews, and classroom observations were used to gauge the teachers’ awareness of, attitudes about, and behavior with regard to IBSE. The outcomes demonstrated that the PD program had a favorable impact on teachers’ attitudes and knowledge to IBSE. IBSE knowledge was higher among the teachers in the PD program group, and they were more enthusiastic about advantages for their pupils.

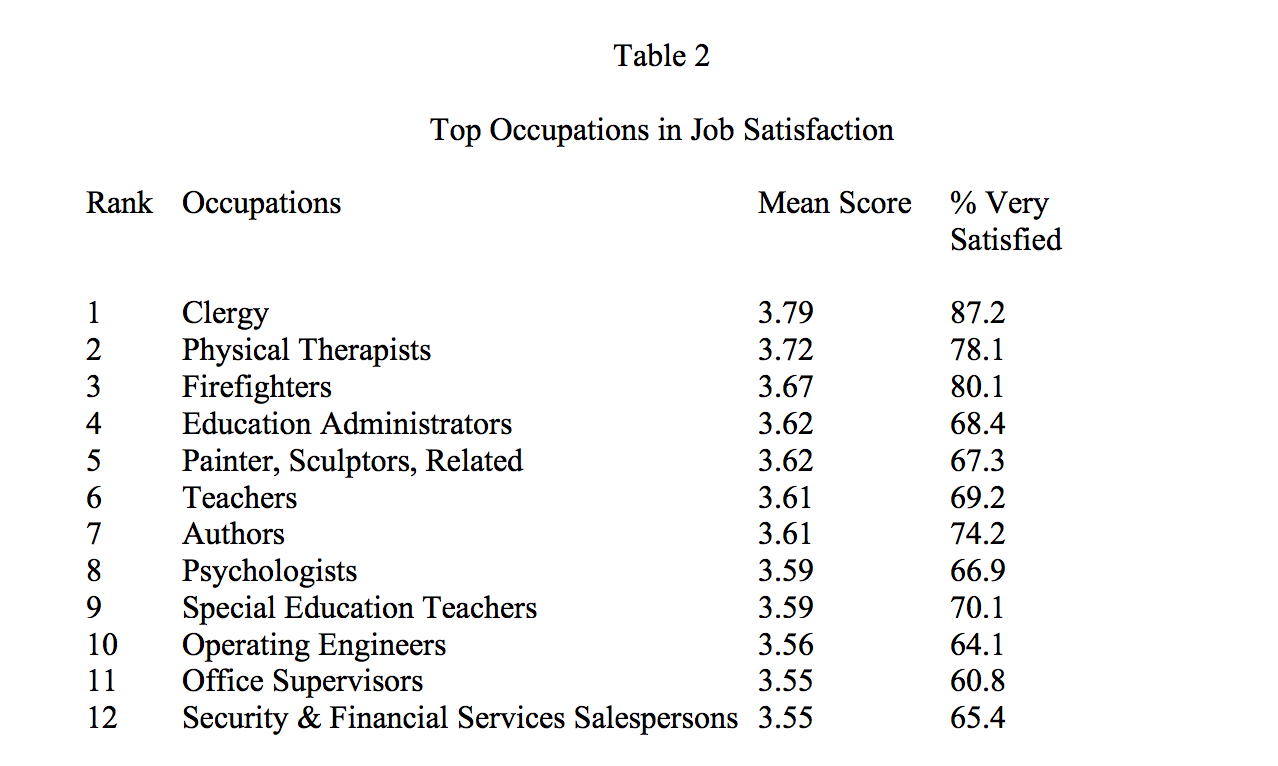

Australia, Chile, Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Korea, Portugal, Spain, USA, Brazil, China, Colombia, Dominia, Peru, Arab, Netherlands Combining the survey and test data of TALIS 2013 and PISA 2012, it is found that there are four main correspondences between teachers’ job satisfaction index and students’ test scores in different countries (regions) (OECD, 2016 ; TALIS, 2013). Countries (regions) with better test performance, such as Finland, Canada (Alberta), Australia, the Netherlands, etc. The second is countries (regions) where teachers’ job satisfaction is high but students’ performance is significantly worse, such as Mexico, Malaysia, Chile, Italy, etc.; the third is countries (regions) where teachers’ job satisfaction is significantly lower than the international average level, but students’ test scores are significantly higher than the international average or even among the best, such as Shanghai (China), South Korea, Japan, Singapore, and other East Asian countries and regions; the fourth is countries with low teacher job satisfaction and low student test scores, such as Bulgaria, Brazil, Russia, etc.

There is a clear correlation between cultural differences in different countries (regions) and teachers’ job satisfaction. Firstly, teachers’ job satisfaction in countries (regions) with a high power distance index is generally lower; secondly, individualism is different in different countries (regions), and there is a potential positive correlation between the index and teacher job satisfaction; furthermore, countries with a high long-term orientation index tend to have lower teacher job satisfaction and vice versa; and lastly, countries with a high indulgence index score. In other regions, teachers’ job satisfaction is generally higher (Wang and Zhang, 2020 ).

Combined with the analysis results, it can be determined to a large extent that national (or regional) culture has a potential impact on teachers’ job satisfaction that cannot be ignored, and compared with the usual experience of “good SA, TJS should also be high”. From the perspective of stereotyped thinking, the degree of influence of cultural differences on teachers’ job satisfaction, or at least the degree of correlation between the two, is more obvious and stronger. Therefore, it seems that a more reasonable explanation can be made for the puzzling differences in teacher job satisfaction in different countries (regions) shown by the TALIS 2013 survey data (Sims, 2017 ; Wang and Zhang, 2020 ). In order to highlight areas for development and to wrap up the section, Kravarušić ( 2021 ) can be quoted. He looked at the fundamental components of the structure of factors in the Republic of Serbia. He discovered that the status of society, the immediate social context, the quality of the study program, the professional environment, continuous professional development, pedagogical practice, the personal characteristics of educators, job satisfaction, and private life all influence the level of competence of teachers. As a result, the setting is a key factor in determining how satisfied teachers are with their work, which in turn influences student progress.

Limitations & recommendations

This review summarizes and analyzes the existing literature on teacher job satisfaction and student achievement, which will help improve student performance from the perspective of teachers’ job satisfaction in the future. However, there are still some limitations in the research process, which can be considered in the follow-up research.

First of all, it is about theoretical research. Although the research on teachers’ job satisfaction theory has been refined and divided into three stages for discussion and definition, the influencing factors obtained from the experimental analysis based on this definition have also been proved to be effective. However, this method of definition has not been widely accepted, which does not mean that researchers have not paid enough attention, precisely because job satisfaction theory involves too much content and there is not enough practice to demonstrate that the theory is true and effective. In addition, due to the repetition and contradiction of different types of theories caused by too many related studies, it has seriously affected the research on the classification and influencing factors of teachers’ job satisfaction at different stages. As the working lives of teachers cannot be simply divided into pre-service teachers and in-service teachers, such as teachers before retirement, teachers in private schools, etc., these can be the basis for classification, and the factors that affect teachers’ satisfaction are also different. At this stage, the theoretical knowledge of teachers’ job satisfaction is simply divided into stages, but teaching is a process, and its complexity and variability cannot be explained clearly by existing theories. The research at this stage cannot realize the analysis of teachers in terms of process. Therefore, future research can focus on defining teachers job satisfaction from different aspects through practice and strive to obtain the most accurate factors that affect teacher satisfaction so as to achieve the adjustment of students’ achievement.

Secondly, the articles chosen for this study include a reasonably high proportion of quantitative research, which is the primary method for studying the theory of teacher satisfaction and examining its affecting elements. However, this means that the research method is single, and the research results mainly come from the results of questionnaires and data analysis. The research results on the influencing factors to improve teachers’ job satisfaction promote the development of teachers’ personal professional abilities, and thus students’ achievement have been confirmed. However, some researchers said that relying too much on questionnaires and data made them ignore the complexity of the research content, and the validity of the research results also weakened their in-depth research ideas to a certain extent. In order to gain a deeper understanding of teachers’ job satisfaction, a qualitative investigation should be used to truly understand the source of teachers’ satisfaction and provide more possibilities for research on influencing factors (Fig. 1 ).

An overview of the overall screening procedures as well as the workflow associated with selecting relevant material. At the beginning of the process, a total of 2188 records were discovered from the databases. After eliminating gray literatures, duplicated papers, book and book chapters and conference papers, the number of articles maintained for further title reading and abstract review was decreased to 632. Following this, only 159 papers met the eligibility requirements for additional abstract reading and main body skimming. Out of that, 67 remained to be read in their entirety. During the main body reading, articles 32 without content pertaining either to teachers’ professional development or student achievement were excluded manually. At last, 32 papers met eligibility requirements for SLR study remained.

Concluding remarks

In the past 12 years, most studies from different countries have paid much attention to the effect of teachers’ job satisfaction on student achievement. Most research shows that TJS will have a positive impact on students achievement (McWherter, 2012 ; Crawford, 2017 ; Andrew, 2017 ; Iqbal et al., 2016 ). Although there is still a small subset of studies showing no significant relationship between TJS and SA, the number of these studies is far lower than the number of studies that believe that TJS has a positive effect on SA (Ejimofor, 2015 ; Borah, 2016 ). There are many factors that affect TJS, but only work treatment, work pressure, co-worker relationships, etc. However, research shows that only classroom equipment and classroom size have a positive effect on both. Research shows that it is largely certain that national (or regional) culture has a non-negligible potential impact on teacher job satisfaction. Moreover, compared with the usual experience and stereotyped thinking that “students have good grades, so teachers’ job satisfaction should also be high”, the degree of influence of cultural differences on teachers’ job satisfaction, or at least the degree of correlation between the two, is more obvious and relevant. The review of this study makes it even more worthwhile to reflect on the need to avoid stereotypical considerations and assessments of any objective presentation of the phenomenon and to reflect more deeply on the need to assess the validity of the relationship study. As in the case of measuring teacher job satisfaction, the extent to which cultural differences affect teacher job satisfaction cannot be ignored. This is why it is important for scholars to develop a framework for measuring teachers’ job satisfaction according to cultural contexts and specific social needs and to give more dimensions to reflection and further measurement. Only on this basis can the overall level of teacher satisfaction be improved, thus increasing the overall level of teacher effectiveness and well-being, and better motivating students to engage in teaching and learning activities that lead to better quality learning outcomes.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analyzed

Andrew K (2017) Teacher job satisfaction and student academic performance at Uganda Certificate of Education in secondary schools in Uganda: a case study of kamwenge district. Doctoral dissertation, Kabale University

Armstrong M (2009) Armstrong’s handbook of management and leadership a guide to managing for results. Kogan

Banerjee N, Stearns E, Moller S, Mickelson RA (2017) Teacher job satisfaction and student achievement: the roles of teacher professional community and teacher collaboration in schools. Am J Educ 123(2):203–241

Article Google Scholar

Bearman M, Smith CD, Carbone A, Slade S, S, Baik C, Hughes-Warrington M, Neumann DL (2012) Systematic review methodology in higher education. High Educ Res Dev 31(5):625–640

Benevene P, De Stasio S, Fiorilli C (2020) Editorial: well-being of school teachers in their work environment. Front Psychol 11:1239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01239

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Borah A (2016) Impact of teachers’ job satisfaction in academic achievement of the students in higher technical institutions: A study in the Kamrup district of Assam. Clar Int Multidiscip J 8(1):51–55. http://www.journalijdr.com

Chen C (2017) An empirical study on the influencing factors of middle school teachers’ job satisfaction——based on the analysis of the Pisa 2015 Teacher Survey Data [in Chinese]. Teach Educ Res 29(2):9

ADS Google Scholar

Crawford JD (2017) Teacher job satisfaction as related to student performance on state-mandated testing. Doctoral dissertation, Lindenwood University

Cunningham J (2012) Student achievement. In: National Conference of State Legislatures. pp. 1–6

Dicke T, Marsh HW, Parker PD, Guo JS, Riley P, Waldeyer J (2020) Job satisfaction of teachers and their principals in relation to climate and student achievement. J Educ Psychol 112(5):1061–1073

Dutta V, Sahney S (2016) School leadership and its impact on student achievement The mediating role of school climate and teacher job satisfaction. Int J Educ Manag 30(6):941–958

Ejimofor AD (2015) Teachers’ job satisfaction, their professional development and the academic achievement of low-income kindergartners. Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Farooqi R, Shabbir F (2016) Impact of teacher professional development on the teaching and learning of English as a second language. J Educ Pract 7(17):41–50

Google Scholar

Fisher CD (2003) Why do lay people believe that satisfaction and performance are correlated? possible source of a commonsense theory. J Organ Behav 24:753–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.219

Beijing Normal University Teachers’ Labor Market Research Group, Guan CH, Xing CB, Chen CF (2021) Secondary school teachers’ career satisfaction and willingness to move and their influencing factors: experience from China Education Tracking Survey data (ceps) Evidence. Beijing Soc Sci 3:19

Hayati K, Caniago I (2012) Islamic work ethic: the role of intrinsic motivation, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job performance. Proc Soc Behav Sci 65:272–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.122

Hee OC, Shukor MFA, Ping LL, Kowang TO, Fei GC (2019) Factors influencing teacher job satisfaction in Malaysia. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 9(1):1166–1174. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i1/5628

Iaffaldano MT, Muchinsky PM (1985) Job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 97(2):251–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.2.251

Ihueze S, Unachukwu GO, Onyali LC (2018) Motivation and teacher job satisfaction as correlates of students’ academic performance in secondary schools in Anambra state. UNIZIK J Educ Manag Policy 2(1):59–68. https://journals.unizik.edu.ng/index.php/ujoemp/article/view/569

Iqbal A, Aziz F, Farooqi T, Ali S (2016) Relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and students’ academic performance. Eurasian J Educ Res 16(65):1–35. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2016.65.19

Kravarušić VB (2021) Factors of professional activity of educators in pedagogical practice, international journal of cognitive research in Science. Eng Educ 9(3):385–398

Liang X, Kidwai H, Zhang M, Zhang Y (2016) How Shanghai does it: Insights and lessons from the highest-ranking education system in the world. World Bank Publications

Lopes J, Oliveira C (2020) Teacher and school determinants of teacher job satisfaction: a multilevel analysis. Sch Eff Sch Improv 31(4):641–659

Ma Y (2012) Talking about the influence of teachers on students’ academic performance [in Chinese]. New Curr Teach Res Edn 12:140–141

Manandhar P, Manandhar N, Joshi SK (2021) Job satisfaction among school teachers in Duwakot, Bhaktapur District, Nepal. Int J Occup Safe Health 11(3):165–169

McWherter S (2012) The effects of teacher and student satisfaction on student achievement. Gardner-Webb University

Michaelowa K (2002) Teacher job satisfaction, student achievement, and the cost of primary education in Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa, 188. HWWA Discussion Paper

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. British Medical Association, Ontario, Canada

Nkengne P, Pieume O, Tsimpo C, Ezeugwu G, Wodon Q (2021) Teacher satisfaction and its determinants: analysis based on data from Nigeria and Uganda. Int Stud Cath Educ 13(2):190–208

OECD F (2016) FDI in figures. Organisation for European Economic Cooperation, Paris

Perera H, Maghsoudlou A, Miller C, McIlveen P, Barber D, Part R, Reyes A (2022) Relations of science teaching self-efficacy with instructional practices, student achievement and support, and teacher job satisfaction. Contemp Educ Psychol 69:102041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.102041

De Rijdt C, Stes A, van der Vleuten C, Dochy F (2013) Influencing variables and moderators of transfer of learning to the workplace within the area of staff development in higher education: a research review. Educ Res Rev 8:48–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.05.007

Rutkowski D, Rutkowski L, Bélanger J, Knoll S, Weatherby K, Prusinski E (2013) Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2013: conceptual framework. Final. OECD Publishing

Sabin JennyT (2015) Teacher morale, student engagement, and student achievement growth in reading: a correlational study. J Organ Educ Leadersh 1:5, http://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/joel/vol1/iss1/5

Shi J, Peng HC, Huang YF (2011) A survey of influencing factors of teachers’ satisfaction in colleges and universities [in Chinese]. J Zhanjiang Norm Coll 32(1):5

Sims S (2017) TALIS 2013: Working conditions, teacher job satisfaction and retention. Statistical working paper. UK Department for Education. Castle View House East Lane, Runcorn, Cheshire, WA7 2GJ, UK

Sun H, Li H, Lin C (2008) Secondary school teachers’ job satisfaction status and its related factors [in Chinese]. Stud Psychol Behav 6(4):260–265

Tayyar KAl (2014) Job satisfaction and motivation amongst secondary school teachers in Saudi Arabia. PhD Thesis, University of York, Department of Education

Tsai P, Antoniou P (2021) Teacher job satisfaction in Taiwan: making the connections with teacher attitudes, teacher self-efficacy and student achievement. Int J Educ Manag 35(5):1016–1029

De Vries S, Jansen EPWA, Van de Grift WJCM (2013) Profiling teachers’ continuing professional development and the relations with their beliefs about learning and teaching. Teach Teach Educ 33:78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.006

Wang Y (2019) Research on the relationship between the leadership of primary and secondary school principals and teacher satisfaction [in Chinese]. Shanghai J Educ Eval 8(6):5

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Wang Z, Zhang M (2020) International comparison of teachers’ job satisfaction: differences, reasons and countermeasures: an empirical analysis based on TALIS data [in Chinese]. Prim Second School Abroad 1:19

Wayne AJ, Youngs P (2003) Teacher characteristics and student achievement aains: a review. Rev Educ Res 73(1):89–122

You S, Kim AY, Lim SA (2017) Job satisfaction among secondary teachers in Korea: effects of teachers’ sense of efficacy and school culture. Educ Manag Adm Leadersh 45(2):284–297

Zong QZ (2016) Influencing factors and incentives of teachers’ job satisfaction. Mod Bus Trade Ind 37(26):2. https://doi.org/10.19311/j.cnki.1672-3198.2016.26.060

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Universiti Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Kazi Enamul Hoque, Xingsu Wang & Yang Qi

Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, 35900, Tanjung Malim, Perak, Malaysia

Normarini Norzan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kazi Enamul Hoque .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This manuscript does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors

Informed consent

Since there were no human subjects involved in this review study, no consent was required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hoque, K.E., Wang, X., Qi, Y. et al. The factors associated with teachers’ job satisfaction and their impacts on students’ achievement: a review (2010–2021). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 177 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01645-7

Download citation

Received : 23 August 2022

Accepted : 27 March 2023

Published : 24 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01645-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Determinants of job satisfaction among faculty members of a veterinary university in india: an empirical study.

- Rachna Singh

- Gautam Singh

- Anika Malik

Current Psychology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

The Relationship Between “Job Satisfaction” and “Job Performance”: A Meta-analysis

- Original Research

- Published: 24 August 2021

- Volume 23 , pages 21–42, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Ali Katebi 1 ,

- Mohammad Hossain HajiZadeh 1 ,

- Ali Bordbar 1 &

- Amir Masoud Salehi 1

7678 Accesses

32 Citations

Explore all metrics

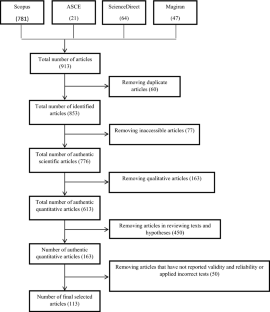

The purpose of this meta-analytic research is to obtain a clear and unified result for the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance, as previous research has shown contradictions in this regard. A total of 913 articles in both English and Persian languages were obtained from four databases, and finally, 113 articles with 123 independent data were selected and analyzed. The random-effects model was adopted based on results, and the analysis resulted a medium, positive, and significant relationship between job performance and job satisfaction ( r = 0.339; 95% CI = 0.303 to 0.374; P = 0.000). Finally, the country of India was identified as a moderator variable. The publication, language, selection, and citation biases have been examined in this study. Increasing and improving the job performance of employees have always been an important issue for organizations. The results of this study can be useful for managers in different industries, especially for Indian professionals in both public and private sectors, to better plan and manage the satisfaction and the performance of their employees. Also, Indian scholars can use these results to localize the global research in this regard.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Mediating Effects of Job Satisfaction and Propensity to Leave on Role Stress-Job Performance Relationships: Combining Meta-Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling

Detecting causal relationships between work motivation and job performance: a meta-analytic review of cross-lagged studies

Development and validation of a self-reported measure of job performance.

Abbas, M., Raja, U., Anjum, M., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2019). Perceived competence and impression management: Testing the mediating and moderating mechanisms. International Journal of Psychology, 54 (5), 668–677. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12515

Article Google Scholar

Abbas, M., Raja, U., Darr, W., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2014). Combined effects of perceived politics and psychological capital on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance. Journal of Management, 40 (7), 1813–1830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312455243

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In Leonard Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–299). Elsevier.

Ahn, N., & García, J. R. (2004). Job satisfaction in Europe. Documento de Trabajo, 16 (September), 29.

Google Scholar

Alessandri, G., Borgogni, L., & Latham, G. P. (2017). A Dynamic model of the longitudinal relationship between job satisfaction and supervisor-rated job performance. Applied Psychology, 66 (2), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12091

Ambrose, S. C., Rutherford, B. N., Shepherd, C. D., & Tashchian, A. (2014). Boundary spanner multi-faceted role ambiguity and burnout: An exploratory study. Industrial Marketing Management, 43 (6), 1070–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.05.020

Arab, H. R., & Atan, T. (2018). Organizational justice and work outcomes in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Management Decision, 56 (4), 808–827. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2017-0405

Bal, P. M., De Lange, A. H., Jansen, P. G. W., & Van Der Velde, M. E. G. (2013). A longitudinal study of age-related differences in reactions to psychological contract breach. Applied Psychology, 62 (1), 157–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00524.x

Barakat, L. L., Lorenz, M. P., Ramsey, J. R., & Cretoiu, S. L. (2015). Global managers: An analysis of the impact of cultural intelligence on job satisfaction and performance. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 10 (4), 781–800. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-01-2014-0011

Bhatti, M. A., Alshagawi, M., Zakariya, A., & Juhari, A. S. (2019). Do multicultural faculty members perform well in higher educational institutions?: Examining the roles of psychological diversity climate, HRM practices and personality traits (Big Five). European Journal of Training and Development, 43 (1/2), 166–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-08-2018-0081

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1 (2), 97–111.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis . John Wiley & Sons.

Bouckenooghe, D., Raja, U., & Butt, A. N. (2013). Combined effects of positive and negative affectivity and job satisfaction on job performance and turnover intentions. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 147 (2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2012.678411

Bowling, N. A., Khazon, S., Meyer, R. D., & Burrus, C. J. (2015). Situational strength as a moderator of the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analytic examination. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30 (1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9340-7

Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes in and around organizations (Vol. 9). Sage.

Bukhari, I., & Kamal, A. (2017). Perceived organizational support, its behavioral and attitudinal work outcomes: Moderating role of perceived organizational politics. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32 (2), 581–602.

Campbell, J. P., McCloy, R. A., Oppler, S. H., & Sager, C. E. (1993). A theory of performance. Personnel Selection in Organizations, 3570 , 35–70.

Carlson, R. E. (1969). Degree of job fit as a moderator of the relationship between job performance and job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 22 (2), 159–170.

Chao, M. C., Jou, R. C., Liao, C. C., & Kuo, C. W. (2015). Workplace stress, job satisfaction, job performance, and turnover intention of health care workers in rural Taiwan. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27 (2), NP1827–NP1836. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539513506604

Charoensukmongkol, P. (2014). Effects of support and job demands on social media use and work outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 36 (July 2014), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.061

Chatzoudes, D., Chatzoglou, P., & Vraimaki, E. (2015). The central role of knowledge management in business operations. Business Process Management Journal, 21 (5), 1117–1139.

Chen, J., & Silverthorne, C. (2008). The impact of locus of control on job stress, job performance and job satisfaction in Taiwan. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29 (7), 572–582.

Chen, L., & Muthitacharoen, A. (2016). An empirical investigation of the consequences of technostress: Evidence from China. Information Resources Management Journal, 29 (2), 14–36. https://doi.org/10.4018/IRMJ.2016040102

Cheng, J. C., Chen, C. Y., Teng, H. Y., & Yen, C. H. (2016). Tour leaders’ job crafting and job outcomes: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20 (October 2016), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.06.001

Chinomona, R., & Sandada, M. (2014). Organisational support and its influence on teachers job satisfaction and job performance in limpopo province of South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5 (9), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n9p208

Choi, Y., Jung, H., & Kim, T. (2012). Work-family conflict, work-family facilitation, and job outcomes in the Korean hotel. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24 (7), 1011–1028.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112 (1), 155–159.

Cortini, M., Converso, D., Galanti, T., Di Fiore, T., Di Domenico, A., & Fantinelli, S. (2019). Gratitude at work works! A mix-method study on different dimensions of gratitude, job satisfaction, and job performance. Sustainability (switzerland), 11 (14), 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143902

Dabić, M., Vlačić, B., Paul, J., Dana, L. P., Sahasranamam, S., & Glinka, B. (2020). Immigrant entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 113 (November 2019), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.013

Dello Russo, S., Vecchione, M., & Borgogni, L. (2013). Commitment profiles, job satisfaction, and behavioral outcomes. Applied Psychology, 62 (4), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00512.x

Derakhshide, H., & Ansari, M. (2012). Investigating the impact of managerial competence and management commitment on employee empowerment on their job performance. Journal of Management and Development Process, 27 (1), 73–93.

Derakhshide, H., & Kazemi, A. (2013). The impact of job participation and organizational commitment on employee satisfaction and job performance in mashhad hotel industry using structural equation model. Journal of Applied Sociology, 25 (3), 89–101.

Dinc, M. S., Kuzey, C., & Steta, N. (2018). Nurses’ job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between organizational commitment components and job performance. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 33 (2), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2018.1464930

Ding, Z., Ng, F., Wang, J., & Zou, L. (2012). Distinction between team-based self-esteem and company-based self-esteem in the construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 138 (10), 1212–1219. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000534

Doargajudhur, M. S., & Dell, P. (2019). Impact of BYOD on organizational commitment: An empirical investigation. Information Technology and People, 32 (2), 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-11-2017-0378

Durrah, O., Alhamoud, A., & Khan, K. (2016). Positive psychological capital and job performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Ponte, 72 (7), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.21506/j.ponte.2016.7.17

Edwards, B. D., Bell, S. T., Arthur Winfred, J., & Decuir, A. D. (2008). Relationships between facets of job satisfaction and task and contextual performance. Applied Psychology, 57 (3), 441–465.

Egger, M., & Smith, G. D. (1998). Meta-Analysis Bias in Location and Selection of Studies. BMJ, 316 (7124), 61–66.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315 (7109), 629–634.

Ersen, Ö., & Bilgiç, R. (2018). The effect of proactive and preventive coping styles on personal and organizational outcomes: Be proactive if you want good outcomes. Cogent Psychology, 5 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1492865

Esmaieli, M., & Seydzadeh, H. (2016). The effect of job satisfaction on performance with the mediating role of organizational loyalty. Journal of Management Studies (improvement and Transformation), 25 (83), 51–68.

EU Statistics Center report. (2019). isna.ir/news/98122619604/

Ewen, R. B. (1973). Pressure for production, task difficulty, and the correlation between job satisfaction and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 58 (3), 378–380.

Fisher, R. T. (2001). Role stress, the type A behavior pattern, and external auditor job satisfaction and performance. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 13 (1), 143–170.

Freeman, R. B. (1978). Job Satisfaction as an Economic Variable. American Economic Review, 68 (2), 135–141.

Fu, W., & Deshpande, S. P. (2014). The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a China’s insurance company. Journal of Business Ethics, 124 (2), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1876-y

Geddes, J., & Carney, S. (2003). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Evidence in Mental Health Care . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-443-06367-1.50015-6

Book Google Scholar

Gerlach, G. I. (2019). Linking justice perceptions, workplace relationship quality and job performance: The differential roles of vertical and horizontal workplace relationships. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 33 (4), 337–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002218824320

Ghosh, K., & Sahney, S. (2010). Organizational sociotechnical diagnosis of managerial retention: SAP-LAP framework. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 11 (1–2), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03396580

Gibbs, T., & Ashill, N. J. (2013). The effects of high performance work practices on job outcomes: Evidence from frontline employees in Russia. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 31 (4), 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-10-2012-0096

Gilal, F. G., Zhang, J., Paul, J., & Gilal, N. G. (2019). The role of self-determination theory in marketing science: An integrative review and agenda for research. European Management Journal, 37 (1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.10.004

Giri, V. N., & Pavan Kumar, B. (2010). Assessing the impact of organizational communication on job satisfaction and job performance. Psychological Studies, 55 (2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-010-0013-6

Godarzi, H. (2017). Investigating the effect of work-family conflict and work-family support on job satisfaction and job performance of employees of National Iranian Drilling Company. Journal of Human Resource Management in the Oil Industry, 9 (33), 111–132.

Goldsmith, R. E., McNeilly, K. M., & Russ, F. A. (1989). Similarity of sales representatives’ and supervisors’ problem-solving styles and the satisfaction-performance relationship. Psychological Reports, 64 (3), 827–832.

Grissom, R. J., & Kim, J. J. (2005). Effect sizes for research: A broad practical approach . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Guan, X., Sun, T., Hou, Y., Zhao, L., Luan, Y. Z., & Fan, L. H. (2014). The relationship between job performance and perceived organizational support in faculty members at Chinese universities: A questionnaire survey. BMC Medical Education, 14 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-50

Gul, H., Usman, M., Liu, Y., Rehman, Z., & Jebran, K. (2018). Does the effect of power distance moderate the relation between person environment fit and job satisfaction leading to job performance? Evidence from Afghanistan and Pakistan. Future Business Journal, 4 (1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbj.2017.12.001

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327 (7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Hill, N. S., Kang, J. H., & Seo, M. G. (2014). The interactive effect of leader-member exchange and electronic communication on employee psychological empowerment and work outcomes. Leadership Quarterly, 25 (4), 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.04.006

Hsieh, J. Y. (2016). Spurious or true? An exploration of antecedents and simultaneity of job performance and job satisfaction across the sectors. Public Personnel Management, 45 (1), 90–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026015624714

Huang, L. V., & Liu, P. L. (2017). Ties that work: Investigating the relationships among coworker connections, work-related Facebook utility, online social capital, and employee outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 72 (July 2017), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.054

Hur, W. M., Han, S. J., Yoo, J. J., & Moon, T. W. (2015b). The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Management Decision, 53 (3), 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379

Hur, W., Kim, B., & Park, S. (2015a). The relationship between coworker incivility, emotional exhaustion, and organizational outcomes: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Medicina (argentina), 75 (5), 303–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm

Iaffaldano, M. T., & Muchinsky, P. M. (1985). Job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 97 (2), 251–273.

Ieong, C. Y., & Lam, D. (2016). Role of Internal Marketing on Employees’ Perceived Job Performance in an Asian Integrated Resort. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 25 (5), 589–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2015.1067664

Iyer, R., & Johlke, M. C. (2015). The role of external customer mind-set among service employees. Journal of Services Marketing, 29 (1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-09-2013-0237

Jabri, M. M. (1992). Job satisfaction and job performance among R&D scientists: The moderating influence of perceived appropriateness of task allocation decisions. Australian Journal of Psychology, 44 (2), 95–99.

Jahangiri, A., & Abaspor, H. (2017). The impact of talent management on job performance: with the mediating role of job effort and job satisfaction. Journal of Management and Development Process, 30 (1), 29–50.

Jain, A. (2016). the mediating role of job satisfaction in the realationship of vertical trust and distributed leadership in health care context. Journal of Modelling in Management, 11 (2), 722–738.

Jannot, A. S., Agoritsas, T., Gayet-Ageron, A., & Perneger, T. V. (2013). Citation bias favoring statistically significant studies was present in medical research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66 (3), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.015

Jeong, M., Lee, M., & Nagesvaran, B. (2016). Employees’ use of mobile devices and their perceived outcomes in the workplace: A case of luxury hotel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57 (August 2016), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.05.003

Johnson, M., Jain, R., Brennan-Tonetta, P., Swartz, E., Silver, D., Paolini, J., Mamonov, S., & Hill, C. (2021). Impact of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence on Industry: Developing a Workforce Roadmap for a Data Driven Economy. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management , 22 (3), 197–217.

Jia, L., Hall, D., Yan, Z., Liu, J., & Byrd, T. (2018). The impact of relationship between IT staff and users on employee outcomes of IT users. Information Technology and People, 31 (5), 986–1007. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-03-2017-0075

Jing, F. F. (2018). Leadership paradigms and performance in small service firms. Journal of Management and Organization, 24 (3), 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.44

Johlke, M. C., & Iyer, R. (2017). Customer orientation as a psychological construct: evidence from Indian B-B salespeople. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 29 (4), 704–720.

Jones, A., Guthrie, C. P., & Iyer, V. M. (2012). Role stress and job outcomes in public accounting: Have the gender experiences converged? In Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research (Vol. 15, pp. 53–84). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/S1475-1488(2012)0000015007

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127 (3), 376–407.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Rubenstein, A. L., Long, D. M., Odio, M. A., Buckman, B. R., Zhang, Y., & Halvorsen-Ganepola, M. D. K. (2013). A meta-analytic structural model of dispositonal affectivity and emotional labor. Personnel Psychology, 66 (1), 47–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12009

Karadağ, E., Bektaş, F., Çoğaltay, N., & Yalçin, M. (2017). The effect of educational leadership on students’ achievement. In The Factors Effecting Student Achievement (Vol. 16, pp. 11–33). Springer. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56083-0_2

Karatepe, O. M., & Agbaim, I. M. (2012). Perceived ethical climate and hotel employee outcomes: an empirical investigation in Nigeria. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, 13 (4), 286–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2012.692291

Kašpárková, L., Vaculík, M., Procházka, J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Why resilient workers perform better: The roles of job satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 33 (1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2018.1441719

Katzell, R. A., Barrett, R. S., & Parker, T. C. (1961). Job satisfaction, job performance, and situational characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 45 (2), 65–72.

Kelley, K., & Preacher, K. J. (2012). On effect size. Psychological Methods, 17 (2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028086

Kim, S. (2005). Individual-level factors and organizational performance in government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15 (2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui013

Kim, T. Y., Aryee, S., Loi, R., & Kim, S. P. (2013). Person-organization fit and employee outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24 (19), 3719–3737. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.781522

Kim, T. Y., Gilbreath, B., David, E. M., & Kim, S. P. (2019). Self-verification striving and employee outcomes: The mediating effects of emotional labor of South Korean employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31 (7), 2845–2861. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2018-0620

Kim, T. Y., Liden, R. C., Kim, S. P., & Lee, D. R. (2015). The interplay between follower core self-evaluation and transformational leadership: effects on employee outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30 (2), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9364-7

Kim, T. Y., & Liu, Z. (2017). Taking charge and employee outcomes: The moderating effect of emotional competence. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28 (5), 775–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1109537

Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0503-8

Kock, N., & Moqbel, M. (2019). Social Networking Site Use, Positive Emotions, And Job Performance. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 00 (00), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2019.1571457

Kolbadinejad, M., Ganjouei, F. A., & Anzehaei, Z. H. (2018). Performance evaluation model according to performance improvement and satisfaction of the staff in the individual sports federations and federations with historical aspect. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 6 (4), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.29252/aassjournal.6.4.59

Koo, B., Yu, J., Chua, B. L., Lee, S., & Han, H. (2020). Relationships among emotional and material rewards, job satisfaction, burnout, affective commitment, job performance, and turnover intention in the hotel industry. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, 21 (4), 371–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2019.1663572

Kumar, A., Paul, J., & Unnithan, A. B. (2020). ‘Masstige’ marketing: A review, synthesis and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 113 (September), 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.030

Kuo, C. W., Jou, R. C., & Lin, S. W. (2012). Turnover intention of air traffic controllers in Taiwan: A note. Journal of Air Transport Management, 25 (December 2012), 50–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2012.08.003

Kuzey, C. (2018). Impact of health care employees’ job satisfaction on organizational performance support vector machine approach. Journal of Economics and Financial Analysis, 2 (1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1991/jefa.v2i1.a12

Laurence, G. A., Fried, Y., & Raub, S. (2016). Evidence for the need to distinguish between self-initiated and organizationally imposed overload in studies of work stress. Work and Stress, 30 (4), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2016.1253045

Lauring, J., & Selmer, J. (2018). Person-environment fit and emotional control: Assigned expatriates vs. self-initiated expatriates. International Business Review, 27 (5), 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.02.010

Lee, M., Mayfield, C. O., Hinojosa, A. S., & Im, Y. (2018). A dyadic approach to examining the emotional intelligence-work outcome relationship: the mediating role of LMX. Organization Management Journal, 15 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2018.1427539

Liao, P. Y. (2015). The role of self-concept in the mechanism linking proactive personality to employee work outcomes. Applied Psychology, 64 (2), 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12003

Lin, S., Lamond, D., Yang, C.-L., & Hwang, M. (2014). Personality traits and simultaneous reciprocal influences between job performance and job satisfaction. Chinese Management Studies, 8 (1), 6–26.

Lipsey, M. W. (2003). Those confounded moderators in meta-analysis: Good, bad, and ugly. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587 (1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716202250791

Liu, F., Chow, I. H. S., Xiao, D., & Huang, M. (2017). Cross-level effects of HRM bundle on employee well-being and job performance: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Chinese Management Studies, 11 (3), 520–537. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-03-2017-0065

Lu, C., Wang, B., Siu, O., Lu, L., & Du, D. (2015). Work-home interference and work values in Greater China. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30 (7), 801–814.

Lu, L., Lin, H. Y., & Cooper, C. L. (2013). Unhealthy and present: Motives and consequences of the act of presenteeism among taiwanese employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18 (4), 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034331

Luna-Arocas, R., & Morley, M. J. (2015). Talent management, talent mindset competency and job performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction. European Journal of International Management, 9 (1), 28–51. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2015.066670

Mathies, C., & Ngo, L. V. (2014). New insights into the climate-attitudes-outcome framework: Empirical evidence from the Australian service sector. Australian Journal of Management, 39 (3), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896213495054

Melian, S. (2016). An extended model of the interaction between work-related attitudes and job performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65 (1), 42–57.

Mikkelsen, A., & Espen, O. (2018). The influence of change-oriented leadership on work performance and job satisfaction in hospitals – the mediating roles of learning demands and job involvement. Leadership in Health Services, 32 (1), 37–53.

Mittal, A., & Jain, P. K. (2012). Mergers and acquisitions performance system: Integrated framework for strategy formulation and execution using flexible strategy game-card. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 13 (1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-012-0004-7

Mohammadi, J., Bagheri, M., Safaryan, S., & Alavi, A. (2015). Explain the role of party play in employee job satisfaction and performance. Journal of Human Resource Management Research, 6 (1), 229–249.

Monavarian, A., Fateh, O., & Fateh, A. (2017). The effect of Islamic work ethic on individual job performance considering the mediating role of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Journal of Management and Development Process, 31 (1), 57–82.

Moqbel, M., Nevo, S., & Kock, N. (2013). Organizational members’ use of social networking sites and job performance: An exploratory study. Information Technology & People, 26 (3), 240–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2012-0110

Mosuin, E., Mat, T. Z. T., Ghani, E. K., Alzeban, A., & Gunardi, A. (2019). Accountants’ acceptance of accrual accounting systems in the public sector and its influence on motivation, satisfaction and performance. Management Science Letters, 9 (5), 695–712. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.2.002

Motowidlo, S. J., & Kell, H. J. (2012). Job performance. Handbook of Psychology, Second Edition, 12 , 91–130.

Mount, M., Ilies, R., & Johnson, E. (2006). Relationship of personality traits and counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effects of job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 59 (3), 591–622.

Naidoo, R. (2018). Role stress and turnover intentions among information technology personnel in South Africa: The role of supervisor support. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 16 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.936

Ng, T. W. H., Sorensen, K. L., & Yim, F. H. K. (2009). Does the job satisfaction-job performance relationship vary across cultures? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40 (5), 761–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109339208

Ning, B., Omar, R., Ye, Y., Ting, H., & Ning, M. (2020). The role of Zhong-Yong thinking in business and management research: A review and future research agenda. Asia Pacific Business Review, 27 (2), 150–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1857956

Noh, M., Johnson, K. K. P., & Koo, J. (2015). Building an exploratory model for part-time sales associates’ turnover intentions. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 44 (2), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12135

Oh, J. H., Rutherford, B. N., & Park, J. (2014). The interplay of salesperson’s job performance and satisfaction in the financial services industry. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 19 (2), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2014.7

Olsen, E., Bjaalid, G., & Mikkelsen, A. (2017). Work climate and the mediating role of workplace bullying related to job performance, job satisfaction, and work ability: A study among hospital nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73 (11), 2709–2719. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13337

Oluwatayo, A. A., & Adetoro, O. (2020). Influence of Employee Attributes, Work Context and Human Resource Management Practices on Employee Job Engagement. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 21 (4), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-020-00249-3