Find anything you save across the site in your account

Inside the Music Industry’s High-Stakes A.I. Experiments

By John Seabrook

Listen to this article.

Sir Lucian Grainge, the chairman and C.E.O. of Universal Music Group, the largest music company in the world, is curious, empathetic, and, if not exactly humble, a master of the humblebrag. His superpower is his humanity. A sixty-three-year-old Englishman, who was knighted in 2016 for his contributions to the music industry and has topped Billboard’s Power 100 list of music-industry players several times in the past decade, Grainge is compact and a bit chubby, with alert eyes behind owlish glasses. He isn’t trying to be noticed. He presides over a public company worth more than fifty billion dollars, but he could be a small-business owner who sells music in a London shop, as did his father, Cecil. On earnings calls, Grainge can sound more like a London taxi dispatcher than a chief executive. But woe to those who mistake his European civility for a lack of competitive fire. “He is so deceptive with that little kind face and those little glasses,” Doug Morris, the previous chairman of UMG, told the Financial Times in 2003, when he was still Grainge’s boss. “Behind them, he is actually a killer shark.” In 2011, Grainge devoured Morris’s job.

As UMG’s leader, he has solidified the dominance of Universal, the largest of the Big Three label groups, helping it to overtake Warner Music and Sony. More than half of Spotify ’s twenty most streamed artists of all time are signed to UMG. But Grainge is also the consummate music man, with forty-five years of experience on both the publishing and the label sides of the business. He oversees a long list of formerly independent labels, including Interscope, Republic, Capitol, Motown, and Island. “Lucian’s like the league commissioner,” Monte Lipman, who founded Republic with his brother Avery, told me. Don Was, the head of Blue Note, UMG’s storied jazz label, said, “He’s the smartest motherfucker in the music business, period. He can operate in the artistic world, and he can operate in the financial world, which are two very different beasts.”

Grainge lives and works in Los Angeles, but West Coast fitness culture has yet to make a convert of him. He neither skis nor golfs, although he sometimes drives the cart for other golfers, doing business between holes. He doesn’t drink or smoke, and, as for drugs, “I panic when I have to take an aspirin,” he has said. He is a family man whose first wife, Samantha Berg, suffered complications while giving birth to their son, Elliot, in 1993, and spent the remaining years of her life in a coma—a profound loss that has colored his world view as much as any professional experience. In March, 2020, Grainge was among the first wave of people in L.A. to contract COVID , and he nearly died, spending eighteen days on a ventilator. After recovering, he told me in his office last November, he had survivor’s guilt. “Why me?” he kept asking himself.

Grainge’s son, Elliot, now thirty and a record man himself (his label, 10K Projects, signed the Gen Z sensation Ice Spice), told me, “We’re not from Hollywood.” He added, of his father, “He doesn’t put on a show, a façade, like so many people out here do—there’s a total difference of personality. He’s from an insular Jewish community in North London. He has a village mentality.”

Still, music has made Grainge a very rich villager. One British music executive told me, “Winning means more to him than to almost anyone else I have met in the music business”; money is just a way of keeping score. Although Grainge’s annual salary—five million dollars—is relatively modest for his position, he received a hundred-and-fifty-million-dollar bonus for successfully taking UMG public, in 2021. Some shareholders objected to the size of this “transition” compensation, deeming it “excessive.” In the U.K., Grainge’s pay package was even discussed in Parliament, in the context of a proposed bill that was promoting equity in the music business. A Conservative M.P., Esther McVey, said, “It’s shocking that record-label owners are earning more out of artists’ works than the artists themselves.”

Grainge lives in a mansion in Pacific Palisades with his second wife, Caroline, whom he married in 2002, and with whom he has raised a daughter, Alice, and a stepdaughter, Betsy. When he got a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, in 2020, Lionel Richie—a longtime Universal artist, and the father of Elliot’s wife, Sofia—honored him at the ceremony. (“That’s a real copyright!” Grainge exclaimed to me approvingly about Richie’s evergreen tune “Hello.” “A wedding and bar-mitzvah song!”) He is highly regarded both by UMG’s artists and by the company’s investors, an extraordinarily difficult twofer to pull off.

His old friend Bono , whose band, U2, is on Island, told me, “Lucian doesn’t do varnish. If you’re looking for varnish from Lucian, you’d better be drinking it. He is exactly as he appears.” He added, “People like us are practiced in the art of dizziness, and the music business can be a dizzy world. But for those of us who like to know where the doors, walls, and windows are, facts are friendly, and they’re more friendly if they don’t come with the kind of back-slapping, white-crowned varnish”—the kind with which music executives often treat artists. Bono did an impression of Grainge for me. “Can’t do it, mate!’’ he barked. “No! Will not. Not gonna happen!” He added that, as a musician, “I feel very comfortable when I know who I’m in the room with, when I don’t have to negotiate with a Janus-faced man.”

Which is not to say that Grainge is always easy to understand. He favors off-the-wall analogies, often involving cars, which he collects. When Grainge first met the English singer-songwriter Jamie Cullum, he declared, “Jamie! You’re like a Formula 1 sausage roll,” an exchange that has been captured for posterity in a cartoon Cullum drew that hangs on a wall outside Grainge’s office. “He talks in riddles, which I find endearing,” Jody Gerson, who runs UMG’s global publishing company, told me. “Weird historical British references, Yiddish things, and every now and then he’ll say, ‘Do you know what I mean?’ And I’m, like, Do I admit that I don’t? He once said to me, ‘Jody, I think like a jazz musician. I don’t always know exactly how I’m getting there, but I know where I’m going to end up.’ Lucian knows what he’s doing at all times, and that’s his process.”

Among investors, Grainge is seen as an executive whose strategic use of technology has reshaped the industry’s business model. At an investor presentation in 2021, Bill Ackman, whose hedge fund, Pershing Square Capital Management, owns ten per cent of UMG, compared Grainge’s impact on the music business to that of Netflix’s Reed Hastings on the TV and film industry; he has also likened Grainge to Walt Disney and Steve Jobs. Irving Azoff, of Full Stop Management, told me that Grainge, who attracted Ackman’s fund and the Chinese tech conglomerate Tencent, which owns twenty per cent of UMG, had created a global investor base to match the company’s roster of global superstars. That, in turn, had enhanced the value of the music industry as a whole, “which had always been traditionally undervalued,” Azoff said.

In the course of Grainge’s forty-five years in the business, everything about the way people create, sell, and consume music has changed. Distribution, once a mainstay—you needed labels to physically get records into stores—has become as easy as hitting an Upload button. Promotion of new music, which labels once controlled by way of radio d.j.s, now occurs on streaming platforms, where algorithms determine playlists. Product lives in the cloud, and revenues, formerly derived from sales of albums and singles, have given way to regular royalty payouts from streaming services. Music executives, who used to come up in the record business, like Grainge and Rob Stringer, the head of Sony Music, are now as likely to be lawyers, private-equity managers, turnaround specialists, or tech leaders—such as Robert Kyncl, the recently appointed C.E.O. of Warner Music Group, who was previously an executive at YouTube.

And yet, unlike print media, television, and film—other creative industries that have struggled to adapt to similar digital transformations—the music industry, after a severe contraction in the first decade of the century, now appears to be more profitable than ever. Streaming revenues alone reportedly surpassed seventeen billion dollars in 2022. It was arguably Grainge who, more than any other executive, defied the grim prognostications of the industry’s imminent demise in the early two-thousands. How did he manage it? After all, even though UMG controls the content, Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta, et al. own the technology.

Link copied

“It’s called a ‘wriggle,’ ” Grainge, in his large sixth-floor corner office, told me on a gray November day. He sat at an oblong table with his back to the window, which faces east toward downtown Santa Monica. A guitar signed by Amy Winehouse was nearby. He held out his hand and wriggled it, his fingers moving like fish nosing through coral. “You’re going to have to figure out if you’re going to go above, beneath, around the side, or through.”

In March, 2023, Neal Mohan, who had just become the C.E.O. of YouTube, received a message from Grainge that said, “Hey Neal, congratulations, when can we meet?” Mohan told me, “It was typical Lucian in that it was warm and friendly, but it was clear that he had real urgency in his request to talk.” The subject was A.I.

A. & R. scouts are said to have ears, and Grainge sports an impressive pair of aural appendages that move up and down the sides of his head when he’s talking. But Grainge uses his nose. “I’ve always been able to smell intuitively what the next scene is,” he said. “Whether it’s punk or New Romantics, I’ve always enjoyed it, picked up on it, and this is my view of technology.” Generative A.I., which can produce novel images, text, and music, smelled to him like the next big scene. “That’s all I am—a talent scout.”

The industry is facing yet another revolution, but what sort isn’t yet clear. Is A.I. a format change in the way music is consumed, like the transition from records and cassettes to CDs, or is it a threat to the business model, as were free downloading and file-sharing? Is generative A.I. a new kind of digital workstation for making music, or is it the new radio—a platform for promoting acts and engaging with fans? Is a new era of musical invention at hand, or will A.I. cripple human creativity?

In April of 2023, an anonymous producer called ghostwriter used A.I. voice replications of Drake and the Weeknd to create a deepfake duet called “ Heart on My Sleeve .” The “Fake Drake” song quickly went viral, sending waves of fear through the industry; Universal’s stock fell by roughly twenty per cent between February and mid-May, over concerns about generative A.I. eroding the value of its copyrights. (The stock has since recovered, and is near an all-time high.) Grainge invited me to imagine an illegitimate version of a Kanye West song featuring Taylor Swift’s voice: “Get your head around that. And then it’s ingested into one of the platforms and someone starts monetizing it.” He added, “I haven’t spent forty-five years in the industry just to have it be a free-for-all where anything goes. Not going to happen while I’m still here!” At the same time, he didn’t want to miss out, in case A.I.-generated material became a new source of revenue for artists—and their labels.

Before Mohan’s appointment, YouTube, which is owned by Google, had developed several key music-related products: paid-subscription services and Content ID, an automated way to detect copyrighted music on the platform. These products dramatically altered YouTube’s relationship with the music industry, turning the lawless wasteland of the early twenty-first century into the industry’s Elysian Fields. Between July, 2021, and June, 2022, YouTube paid more than six billion dollars to rights holders globally.

Last spring, Grainge flew to San Bruno, south of San Francisco, where YouTube is based. This was around the time that people in nearly every content industry were awakening to the fact that Google, Microsoft, Meta, and OpenAI were scraping material of all kinds from the Internet to use in training their A.I. models. As lawyers in all those content businesses mulled suing for copyright infringement, Grainge’s instinct was to play with the technology. It was the same approach he had taken to music streaming. “He experiments early,” Daniel Ek, a founder of Spotify, told me. “So then the cost isn’t as huge later, because you’re not betting the farm on everything you’re trying to do.”

DeepMind, Google’s artificial-intelligence research lab in London, had been working on generative-A.I. music technology. One model—which Google later dubbed Lyria—was just emerging from the lab, and Mohan and his colleagues were beginning to ponder how to put it to use. He welcomed Grainge’s input. “I remember in one of our first conversations Lucian said we need a constitution,” Mohan recalled. Working with YouTube colleagues, Mohan came up with three “principles”: a commitment to the “responsible” use of A.I. in collaboration with music partners; a pledge to continue refining safety protocols and guardrails; and systems that would help counteract trademark and copyright abuse. Google has created a tool called SynthID, which can watermark and detect synthetically generated content.

Still, it seemed highly likely that music-generating A.I.s had been trained on at least some copyrighted material, without a license. In experimenting with the technology, would Grainge be implicitly endorsing the scraping that UMG’s lawyers could potentially go to court to stop? Grainge told me that the industry’s historical response to engaging with tech companies had been fear. “The lawyers have done what’s necessary to protect us,” he said. “But if a strategy is only seen through the lens of what can go wrong, the people running the business become scared and paralyzed. Well, I don’t do scared.”

“I always say that the music industry chooses you,” Grainge told me. In the nineteen-fifties, his father, Cecil, was the proprietor of GrAInge, a North London record shop and appliance retailer. (The “AI” in the logo was uppercased, a spooky coincidence.) Grainge has an early memory of watching his father shave while he whistled “Hey Jude”: “How is it he’s not cutting himself? He couldn’t stop whistling that melody.” Music was always playing in the house. “I’d get woken up to Neil Diamond, the ‘Radetzky March,’ Fats Domino, lots of Ray Charles,” he said.

“It’s in the blood,” Irving Azoff said of being in a music family; both of his sons are in the industry. “Being around it your whole life, you get a perspective you couldn’t learn in business school.”

Grainge’s half brother Nigel, thirteen years his senior, had begun a career in music that would eventually lead to his signing Sinéad O’Connor, the Waterboys, Thin Lizzy, 10cc, and Bob Geldof’s band, the Boomtown Rats, to his record label, Ensign, which he founded in 1976. He took Lucian, still in his mid-teens, to see the Ramones on their first U.K. tour. Grainge also saw the Sex Pistols and the Stranglers, among other punk acts, and hung out in a derelict house where the Damned rehearsed. He loved it all, including being gobbed on at gigs. “I had a jacket covered with saliva,” he said. “I used to leave it on a heap on the floor.” He also learned to pogo. “Because I was normally the shortest one at the club, people would use me to pogo off,” he said. “When Bob Geldof got smacked in the mouth at the Music Machine”—a venue in Camden Town—“and lost his front teeth, the guy who did it pogoed off my shoulders.” (Geldof, who has also been knighted in the intervening years, recalled the young Grainge as “kind of annoying, in a little brother way,” but clarified that, although his lip was bruised and his nose bloodied that night, no teeth went missing.)

When Grainge was seventeen, a talent agent in Soho hired him as a sandwich guy, the lowliest gofer. He balanced work with study at Queen Elizabeth’s School, a venerable institution for boys in North London, established in 1573. His mother, Marion, a certified public accountant, was keen for her son to go to university; Grainge didn’t see the point. He agreed to take his A-level exams, but during one of the tests a proctor admonished him for wearing red shoes instead of black ones, which Grainge was said to have been “really fucked off” about. He walked out of the exam and later that day signed a producer to the agency he worked for. His mother was livid; his father, who had left school at age fourteen, didn’t care. (Years later, when Elliot told his father that he wasn’t planning on attending college, Grainge wouldn’t hear of it. Elliot graduated from Northeastern.)

In 1979, Maurice Oberstein, an American record man who helped build CBS Records U.K. into a powerhouse in the late seventies, hired Grainge as an A. & R. scout on the publishing side. A towering figure in the British music industry, Obie, as Oberstein was called, appeared to enjoy making visitors uncomfortable by behaving eccentrically, bringing his dog to meetings and pretending that he was listening to the canine’s advice. “Obie was one of the most brilliant record executives I ever met,” Grainge told me. “He absolutely terrified me and most of the people around him.” (Grainge has been known to have a similar effect at times. “It’s how he tests you,” John Janick, the head of Interscope, told me.)

In 1979, Grainge signed the Psychedelic Furs to a writing contract, mainly because of their song “Sister Europe,” which hadn’t yet been released. He spent a decade in publishing, traditionally the more conservative wing of the business: while the labels focus on breaking new acts, publishing favors a measured approach, building long-term value in evergreens. As a “song guy,” Grainge acted as a consultant to writer-performers he signed, and developed material for established artists who didn’t write. In 1982, he became the director of R.C.A.’s publishing arm, where he signed the Eurythmics. Grainge told me, of signing acts in those days, “All I needed was a Walkman, a park bench, and a checkbook. The rest is bullshit.” Mike Caren, a longtime record executive formerly at Warner, told me, “Working with artists and songwriters is the closest you can be to the creative process.”

Grainge’s early years in the business were a fertile time in music. Punk taught him about the power of a “scene,” Grainge’s shorthand for the way a musical subculture can fuse with fashion, art, media, and politics to change mainstream culture. As hip-hop, one such scene, emerged in the U.S., Grainge observed how technology, in the form of early samplers and drum machines, could enfranchise artists who lacked access to instruments, music lessons, and studios. The rise of New Wave bands, which eclipsed punk, schooled Grainge in how transient scenes can be. One minute he was getting spit on by lads in ripped tees, “and then I wake up and I’m with Steve Strange”—the dandyish front man of the band Visage—“and all the guys look like girls. And the saliva is gone.” That’s why he wasn’t alarmed, years later, when streaming disrupted the industry. “I feel exactly the same with music in the cloud. Everything’s disruption, disruption, change, change. I’m used to disruption.”

By the early eighties, formerly independent labels that were run by their founders—such as Chris Blackwell’s Island and Ahmet Ertegun’s Atlantic—had begun to attract Wall Street interest, thanks in part to the enormous success of records like Peter Frampton’s double album “Frampton Comes Alive!,” on A&M. Labels began merging, to increase market share, offset distribution costs, and spread risk. In 1986, Grainge joined PolyGram, a Dutch-German entertainment company that had expanded into the U.S. and the U.K., to launch a publishing division. He acquired the rights to the catalogues of artists like Elton John, recognizing how valuable copyrights would be in the burgeoning CD era, with the repackaging of older work. That acumen would prove crucial in the streaming age, as catalogues replaced new hits as the primary source of income; one report showed that catalogues represented about seventy per cent of the U.S. music market in 2021.

Toward the end of his publishing career, Grainge was involved in one of the most renowned catalogue rejuvenations ever. In 1992, PolyGram released “ABBA Gold,” a greatest-hits collection. After the band split up, in 1982, “we thought it was finished,” Björn Ulvaeus, who wrote the Swedish foursome’s songs with Benny Andersson, told me. “I really believed that. Oh, they might play the odd song, with a reference to the seventies, perhaps, but that’s it.” Grainge, working with his colleagues John Kennedy and David Hockman, was instrumental in rebranding the band for a new generation. “It became a huge hit,” Ulvaeus said of “ABBA Gold.” “I have to thank those guys. They saw something else.”

The following January, Grainge moved over to the label side, becoming the head of A. & R. and business affairs at Polydor, a PolyGram label. It had done well with the Bee Gees in the seventies but now had a roster of waning artists. Grainge helped turn things around by signing acts like the Cure, Take That, the Cardigans, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. But it was when he was at Polydor that Grainge’s private life was torn apart, after his wife, Samantha Berg, suffered an amniotic-fluid embolism while giving birth to Elliot. “In the space of an hour, I lost my wife and became a father for the first time,” he told me. “It’s the worst thing that could happen to someone. I had a son to raise, and that became my priority. I became braver. In my professional life, I suppose it enabled me to confront challenges as well as risk with a different mindset, in a way I might not otherwise have had.”

In 1997, he became the managing director, a job transition that Grainge now considers the most daunting in his career. At the time, CD sales were driving the industry to new heights, and record companies were growing ever larger. In 1995, the Canadian conglomerate Seagram, led by Edgar Bronfman, Jr., an heir to the Seagram’s liquor fortune, had acquired the MCA Music Entertainment Group, and the following year renamed the company Universal Music Group. Two years later, Seagram bought PolyGram. In 2000, Seagram was sold to the French media company Vivendi. Grainge rode this merry-go-round of mergers and acquisitions to greater power. Bronfman appointed him head of Universal Music U.K. in 2001, and he took over UMG International in 2005. Unfortunately, his ascendancy came just as the industry that he had grown up with was facing extinction.

In the fifteen years after the pioneering file-sharing service Napster launched, in 1999, worldwide music revenues declined more than forty per cent. Thousands of people lost their jobs. In 2004, Grainge assembled his senior executives in the company’s boardroom in London. He sat in silence until they all were seated, and then he got up and switched off the lights. “This is what’s going to happen to the company unless you get some hits and fucking fix file-sharing,” he said, and walked out. (Bono, who had heard about this famous meeting, did his Grainge impersonation when he gave his account: “Roight! Get used to the dahk!”)

Per Sundin, a record executive in Sweden, recalled meeting Grainge in 2009: “I said, ‘We’re firing people like crazy, and there’s no upside coming.’ And Lucian was totally positive. His confidence—about music, songs, and songwriters, but also about the future—was contagious. This is a guy who doesn’t fear anyone.”

In 2007, Grainge and Nokia made one of the first “all you can eat” music deals: buy the phone and download as much UMG music as you want for a year. Such deals are now the norm. “The fact is that much of the industry was scared to make the shift to an access model,” he told me. “And I understand why. When your whole existence has been based on a wholesale retail-transaction model, a fundamental shift like that can be terrifying.”

Daniel Ek, of Spotify, met Grainge the same year. “A lot of people at that time were trying to protect their jobs,” Ek told me. “But Lucian’s view was, How do I protect music, regardless of what happens to me?” Ek believed that a free, ad-supported model for music streaming would act as a “funnel” to bring in users and then convert them to paying subscribers, through premium features. But free music was a non-starter for Edgar Bronfman, who by then was C.E.O. of Warner Music Group. (In 2004, Bronfman had led a group of investors who acquired WMG from Time Warner.) “Free streaming services are clearly not net positive for the industry, and, as far as Warner Music is concerned, will not be licensed,” he said at the time.

Grainge didn’t love the idea of free music, either. Yet he supported Ek’s vision, and was instrumental in getting Spotify licensed in the U.S., in 2011. But the free tier remained contentious (and still is). Ek recalled a particularly difficult negotiation a few years later over renewing the license, which was set to expire. “I was running up against the clock, both sides were threatening each other, and I was kind of getting stressed out,” Ek told me. His partner, Sofia Levander, was about to give birth to their first child. “Lucian called me up,” he went on. “I was expecting him to scream at me, ‘You’ve got twenty-four hours!’ But what he actually said was, ‘I just heard that you’re about to become a father. I’ve been in this situation myself, where it was really difficult in my professional career. You know what, I’m just going to renew the existing deal as is for two months. Go have your baby, take it easy, we will sort it out somehow.’ He had no financial reason for doing that. In fact, it would probably have been better for him to wear me out while I was going through a lot of hardship.” He added, “And when I came back we sat together and worked it out.”

Bronfman recently described the tough stance that he took with Ek in the early days of streaming. “I said, ‘Look, Daniel, you will have people on the free tier forever—that’s just not right,’ ” he told me. But, he added, “Lucian was more the leader and I was the outlier.” Grainge’s approach to A.I. today, Bronfman believes, is “very consistent” with his initial approach to streaming. “He has always wanted to enable technologies,” Bronfman said. “He doesn’t want to shut them down, but he doesn’t want to give them entirely free rein until he has a better understanding of their potential, either to grow or harm the industry.”

In 2011, Grainge became the head of global UMG, which was based in New York, after spending six months as co-C.E.O. with Doug Morris. He decided to relocate the company to L.A., in part to be closer to Silicon Valley, and in part to establish a new power base away from New York and Morris’s loyalists. Although the unique cultures of the formerly independent labels had mostly disappeared by the twenty-first century, Grainge, like Morris before him, sought to revive the entrepreneurial spirit that made them successful in the first place, encouraging UMG label heads to compete not only with outside labels but with one another. He told me that he had learned from Obie the importance of “surrounding oneself with brilliant creative executives,” and that “they needed to be treated like artists themselves.” Interscope’s John Janick, whom Grainge helped bring in to succeed Jimmy Iovine, told me, “I’m an employee here, but he makes me feel like I’m building the company I run.”

Eleven months into his tenure as UMG’s chairman, Grainge made a huge wager on the future of music and on his own career. EMI, the British music conglomerate—home to the Beatles and Queen—had gone bankrupt after a disastrous sale of its assets to Guy Hands, a British private-equity investor who thought that he knew how to run a record company.

In what could now be called one of the biggest bargains of all time, Grainge bought the company from Citibank for $1.9 billion. Competitors raised antitrust concerns; Congress held a hearing, where Bronfman said that the merger would create “one innovation-stifling dominant player”; and the European Commission issued a two-hundred-page statement of objection. Citibank sold EMI’s publishing arm to Sony. Grainge sold some of the labels, including Ensign, his brother Nigel’s former label, to appease the regulators. (Nigel died in 2017, at the age of seventy, owing to complications from surgery.)

“I would take ‘innovation stifling’ out,” Bronfman said, when I asked him how he felt about his testimony today.

UMG’s larger market share enhanced Grainge’s leverage with the tech companies. When it comes to a wriggle, scale matters. “I’m negotiating with companies whose value runs into the trillions,” Grainge told me. “In that sense, we’re a minnow.” He forged the first licensing deal between a major record company and a social platform, when he entered into an agreement with Facebook, in 2017. In the past decade, YouTube, Snapchat, Amazon, Peloton, and any number of gaming companies, fitness apps, and purveyors of online karaoke have come to Grainge seeking licensing deals. “I was around for some of that,” Neil Jacobson, a former president of Geffen Records, which is part of Interscope, told me. “It’s the greatest negotiation in the history of the music business. He knew how to play one against the other.” Azoff observed, “He deserves full credit for knocking down these walls and making them start dealing with us, but he would be the first to say the fight’s far from over.”

Grainge starts each year with a memo to the UMG staff—the music-industry equivalent of Warren Buffett’s annual letter to his shareholders. His January, 2023, epistle to UMG’s ten thousand employees began with chest thumping over the company’s domination of the charts, with tracks by Taylor Swift, the Weeknd, Feid, Karol G, Lana Del Rey, Morgan Wallen, Olivia Rodrigo, the Rolling Stones, and Drake, who on the 2021 Migos song “Having Our Way” dropped the chairman’s name:

Shit done changed Billionaires talk to me different When they see my paystub from Lucian Grainge.

Then Grainge turned to “content oversupply,” as he referred to it. In spite of the popularity of the company’s superstars (several of the most followed people on social media are Universal artists), UMG’s over-all share of the streaming market is declining, as is that of the other label groups. A decade ago, according to a study published by Bank of America, major labels were responsible for about ninety per cent of the content on streaming platforms; today, their share is roughly ten per cent. YouTube and TikTok have allowed emerging artists to monetize their careers without major-label help. Ice Spice, Jack Harlow, and Lil Nas X, for instance, owe their ascendancy to social media.

Grainge grew up in an industry in which labels were the only game in town. Now the platforms are clogged with aspiring musicians, hoping that an algorithm will notice them. In a report last year, the research company Luminate said that, of the hundred and eighty-four million tracks available on streaming platforms, 86.2 per cent received fewer than a thousand plays, and 24.8 per cent—45.6 million tracks—had zero plays. It seems that Spotify, which in many ways could be considered the Netflix of music, has also become something like Friendster: a place for amateurs to post homemade work for friends.

In Grainge’s view, this oversupply is “getting in the way of real talent and real songwriters,” he told me. Many of the hundred and twenty thousand new tracks flooding into streaming platforms each day aren’t songs at all; they’re “functional music” designed for exercising, concentrating, or sleeping, including such bangers as “Baby White Noise” and “Rain on Windshield.” Endel, a prominent functional-music company, has estimated that there are as many as fifteen billion streams of these tracks a month. In our conversations, Grainge pointed to a vacuum sound that had recently risen to No. 7 on the Swiss music charts. A.I. was likely to vastly increase what he called the “sea of noise.” (In May, 2023, in another kind of wriggle, Grainge himself entered the market, when UMG announced a partnership with Endel that would allow UMG artists to use A.I. to make functional versions of their songs.)

The payment system that was being used by Spotify and other platforms—a pro-rata model that Grainge helped create—paid a share of the aggregate royalties to labels based on the percentage of the total that their artists’ streams represented. The labels were then responsible for paying out the artists’ share. It galled Grainge that all streams were valued the same, whether it was Drake or a dripping faucet. A pro-rata model also didn’t account for the added value of major acts, which drive people to pay, and stay subscribed to, premium streaming services. As Monte Lipman put it to me, “With these superstar artists, when they set a release date, you see these sharp spikes in the streaming space, and you don’t necessarily see that with rainwater hitting the windshield.”

In his letter, Grainge called for a new “artist-centric” model that would value legitimate artists at a higher rate. It is a measure of his clout that by the time his 2024 letter came out, in early January, Spotify and several other platforms were adopting key aspects of this model. The French streaming service Deezer, for example, now counts an instance of someone searching for and listening to a song—rather than listening after it has been served up by an algorithm—as two streams. On Spotify, tracks must have a thousand plays in a year before they can start generating revenue. “Is it fair?” Daniel Glass, who heads the indie label Glassnote, said. “No. But Lucian did the right thing for the music industry.”

I asked Grainge how he could be sure that one of those hundred and twenty thousand new songs that crop up every day might not be the next hit.

“How are you going to find that?” he said. “There’s too much stuff! And it is just stuff.”

In June of 2023, Mohan arranged for a demonstration of the nascent Lyria for Grainge and several members of his team, at Grainge’s home. Prompted by a text command, Lyria generated an instrumental version of the melody of Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” in the style of John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things.” It was impressive, but Grainge wasn’t surprised. He had seen this kind of thing before, back in the early eighties, when synthesizers, samplers, and drum machines became especially popular. “Everyone said it was the end back then,” he observed.

Michael Nash, UMG’s chief digital officer, and Will Tanous, the chief administrative officer, attended the meeting. “I don’t mean to be a wet blanket,” Tanous said after the demo ended, “but there’s a huge section of the artist community that won’t be down with this.” Musicians were growing anxious about what A.I. might do to their careers.

YouTube and UMG discussed the idea of an “artist incubator.” Songwriters, performers, producers, and rights holders would experiment with the technology and give Google feedback, including any concerns. By August, the incubator was up and running. Participants included Don Was, Björn Ulvaeus, the artist Rosanne Cash, the composer Max Richter, the rapper Yo Gotti, the OneRepublic front man Ryan Tedder, and representatives of the estate of Frank Sinatra.

In October, Don Was told me about his session with Lyria. He prompted the model with the name of a famous artist, a legendary singer-songwriter he had worked with in the past, asking for a song about his first car. The DeepMind team suggested adding the command “produced by Don Was.” The A.I. generated four different fragments of songs about cars, all with lyrics, melodies, and orchestration, and sung in the A.I.-generated voice of the artist, which had been learned from YouTube videos. Was described the experience as “a combination of awe and terror simultaneously.” His first thought was “This is better than anything I could have done.” His second was “I could collaborate with myself on my very best day.” For that reason, he told himself, “the songwriters are going to like this more than anybody, as long as you can’t steal from them.” He imagines an A.I. that has been trained on an artist’s complete works, and which other songwriters could collaborate with, for a fee. The songwriter, he mused, “gets paid, and he can put his name on the song if he likes it, take it off if he doesn’t.”

DeepMind representatives met with Ulvaeus in Stockholm; he later spent a day at DeepMind, in London. “I can only describe it as an extension of my mind,” Ulvaeus told me. I quoted Was’s line about writing with yourself on your “very best day.” “Exactly,” Ulvaeus replied. He talked about hearing the Beatles on the radio as a young man. “We kind of trained on that,” he said. “And, when we started writing, all of those references—we used them for inspiration.” But the A.I. would be able to reference so much more than he had. “Every songwriter in the world would subscribe to that service if it was good enough,” he said. He’d also started to think about monetization. “The A.I. models would have a heap of money like Spotify does, and that money could be distributed back to songwriters and labels according to consumption,” he suggested, adding, “It’s a blunt instrument, but that’s one way of doing it.”

It’s possible that questions over copyright and monetization could take years to sort out. By that point, the A.I. version of an artist might not need her anymore, once it has learned everything there is to learn about her style. And who would own the output: the prompter of the A.I. or the artist whose style was the inspiration? “I have to accept that the prompter gets a copyright,” Ulvaeus said. “It sounds radical, but I see no other way.”

But why was training a song-generating A.I. like Lyria any different from the way that he and Benny Andersson had drawn on their memories of listening to the Beatles in making their hits? Because, as Ulvaeus pointed out to me, the Beatles music that they heard was licensed and paid for.

When I asked Grainge whether licensing the music used for training A.I.s was the way forward, he offered an automobile analogy. “If only it were as simple as buying a car: ‘This is what the manufacturing cost is, this is what the taxes are,’ ” he said. “This is more like building a car, so it’s far too early for me to discuss business models.” He added, “But it’s in my bones to try and be ahead.”

When I met with Grainge in California, YouTube was about to announce an experimental venture called Dream Track. A select group of a hundred YouTube creators would get to use the A.I.-generated voices and songwriting styles of nine well-known singer-songwriters, three of them from UMG—John Legend, Demi Lovato, and Troye Sivan—to create YouTube Shorts of up to thirty seconds. Four Warner artists would also be involved: Alec Benjamin, Charlie Puth, Charli XCX, and Sia. And T-Pain and the rapper Papoose rounded out the group. As Lyor Cohen, YouTube’s global music head, explained in a blog post about the experiment, the creators would simply have to type an idea into the creation prompt and select one of the artists from a carrousel in order to produce a unique soundtrack for their Shorts.

For Grainge, Dream Track represented an unusually bold collaboration between a content colossus and a tech superpower, in an effort to determine how to monetize synthetic vocals. Among other possible applications, Grainge was curious how the technology could be used to create new iterations of hit songs which would be sung in different languages by A.I.-generated versions of the artists’ voices. In the U.S., artists own their voices and likenesses, which are protected not by copyright but by the “right of publicity.” After Fake Drake appeared, last April, people were using services like Voicify to flood streaming platforms with tracks that replicated artists’ voices and songwriting styles without permission. UMG issued thousands of takedown notices, but efforts were complicated because right-of-publicity statutes exist only at the state level. UMG has lobbied Congress for a federal right of publicity, and a recent bipartisan bill, the No AI Fraud Act, aims to protect artists’ voices under federal intellectual-property law. “I personally think legislation is critical,” Grainge told me. He sees the unlicensed use of A.I.-generated voices and styles “as a form of identity theft.” It’s “immoral,” he said.

One day, Grainge invited me to tag along to a meeting with his “creative SWAT team” to discuss both Dream Track and the artist incubator. In a conference room called ABBA—each meeting room in the building is named for a famous UMG artist or act—seven men and one woman were waiting at a long table, with the empty chair at the head reserved for Grainge. He began by noting that this was a limited experiment. Rigid controls were in place so that the users couldn’t, say, prompt the John Legend A.I. to sing a hymn to terrorists. The output is closely monitored by YouTube and watermarked using SynthID.

“Sometimes you need a Snickers bar to get to the filet mignon, to stop you from driving into a concrete pillar and killing yourself along the way,” Grainge remarked, in a typically tortured analogy. He was particularly concerned that a superstar artist might object to UMG’s involvement in a generative-A.I. experiment with Google. Bad Bunny had recently declared, to fans listening to an unauthorized deepfake track that used his voice, “You don’t deserve to be my friends.”

Grainge went on, “I can just hear it—‘I don’t fuck with A.I.!’ ” He added, “We have to be ready. Let’s not be afraid. Let’s just be prepared.”

The discussion turned to the incubator. Dickon Stainer, UMG’s global head of classical music and jazz, who was joining the meeting by Zoom from London, reported that his artist Max Richter was delighted to be invited into the incubator. “He’s been through all the format changes, from albums to CDs, CDs to downloads, downloads to streaming, and he feels he was powerless to affect any of that,” Stainer said. “And all of a sudden he feels like he can be in the middle of the conversation.”

It was late in London. “Do you have your p.j.’s on under that shirt, Dickon?” Grainge called out, with a laugh. “The ones with the little animals on them?”

“I’ve been out to a gig!” Stainer replied.

Grainge wrapped up the meeting with a couple more metaphors. “I don’t think this will be plain sailing,” he said. “It’s like going to the dentist. ‘If you experience any pain, let me know and I’ll stop immediately.’ That’s what this is.”

The larger question of whether copyrighted material can be used as training data for A.I. is far from settled. In October, Universal Music Publishing Group and other prominent publishers sued the A.I. company Anthropic—the creator of Claude, a “next generation AI assistant for your tasks, no matter the scale”—for systematic and widespread infringement of copyrighted material in the training of Claude and in its potential output. Both sides submitted written responses to the U.S. Copyright Office on several topics, including fair use and copyright. Anthropic maintains that its A.I. uses a vast body of work, of which lyrics are one small element, to build a statistical model of the way language functions.

In reference to the overarching challenges posed by generative A.I., UMG argued in its submission to the Copyright Office that “the wholesale appropriation of UMG’s enormous catalog of copyright-protected sound recordings and musical compositions to build multibillion commercial enterprises . . . is simply theft on an unprecedented scale.” Jonathan King, a copyright lawyer who worked on the submission, told me, “One of the principles of fair use is that authors ought to be allowed to build upon the work of other authors in some circumstances. But that’s not how A.I. works. A.I. uses copyrighted materials to emulate human authorship. The machine is not an author, in the traditional sense of a creative and expressive human being, because it is just synthesizing an imitation of human content, derived from algorithms that study and try to sound like human authors.”

Grainge wasn’t waiting for the courts to decide what constitutes fair use. Recalling the first decade of file-sharing, he said, “If we had waited for the tech companies to finish innovating, we would have ended up as roadkill.”

“I ’m never really apprehensive about anything,” Grainge told me of his exploratory A.I. ventures. I had raised the question of whether he could really trust Google, since the company’s long-term interests may lie in giving its users the tools to close the gap between wannabes and real artists by making it possible for anyone to create a fully orchestrated song by typing in a prompt or even whistling a melody. A tsunami of noise could be coming.

Grainge doesn’t indulge in such existential fears. “The things that make me apprehensive,” he said, “are when people can’t see around the corners and the bends.” He made the swimming motion with his hand again. “Technology has served the industry very well,” he went on. “From sheet music to upright pianos to big bands and the huge CBS radio network in the U.S. that was going to destroy fledging shellac sales. In the eighties, Linn drum machines, 808s, the Fairlight synthesizer—we’ve always been served very well.” In any case, he added, there was no point in fighting generative A.I. “What are we going to do?” When a company the size of Google is “making an investment in developing products and tools,” he said, “my view is, as an industry, we need to be the hostess with the mostest.”

Grainge mentioned new health-and-wellness projects that UMG was pursuing with a couple of startups, according to research on how music affects the brain. “If you’ve ever been in a ward with brain-injury patients, as I have, unfortunately,” Grainge said, pausing for a second before continuing, “the music-therapy person is like the guy in a Mexican restaurant who goes around and plays at your table. I thought, How can we use the technology—headphones, earbuds, and software—to program inaudible frequencies into the music for the region of the frontal lobes that affects pain and reduce stress? And I think we’ve got it. I believe that we’ve got a product that over a twelve-minute period will be as effective as a valium.” He added, “It’s brilliant for catalogue—that’s the businessman in me. But it also shows the importance of music to the world. It is emotionally healing as well as physically healing.”

Had Grainge’s brush with death at the beginning of the pandemic informed his view of life, work, or the threat of A.I.? Had he answered the question “Why me?” “I’m not a particularly spiritual person,” he said. “I care about music, I care about artists, I care deeply, deeply, deeply about this industry. That was the impact the illness had.” After another pause, he added, “You know, the reality is, we’re no more than a speck of sand. All of us.”

“The last time I spoke to Lucian,” Bono told me, “he was going on about Africa: ‘It’s so exciting! All these new artists!’ He was looking at talent in Nigeria.” By 2050, more than a third of the world’s youth will live on the African continent.

When the African music scene came up in our conversation, Grainge got so worked up that he seemed like he might pogo off his chair. “A dancehall record coming out of Lagos—to an old-fart talent scout like me, this is wonderful,” he said. His ears were up. “Because they’re scenes. And then they start to cross-pollinate. It’s the greatest feeling when you’ve placed a song with an artist, or you’ve seen a band and there’s fifty people, then one hundred and fifty people, then three hundred people. It’s the greatest feeling in the world.” ♦

An earlier version of this article misidentified one of the artists involved in the Dream Track experiment.

New Yorker Favorites

The day the dinosaurs died .

What if you started itching— and couldn’t stop ?

How a notorious gangster was exposed by his own sister .

Woodstock was overrated .

Diana Nyad’s hundred-and-eleven-mile swim .

Photo Booth: Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged portraits of Black love .

Fiction by Roald Dahl: “The Landlady”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By David Owen

By Rachel Aviv

By Emily Witt

By Eric Lach

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 July 2021

Cultural Divergence in popular music: the increasing diversity of music consumption on Spotify across countries

- Pablo Bello ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2343-9617 1 &

- David Garcia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2820-9151 2 , 3 , 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 182 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

12 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

The digitization of music has changed how we consume, produce, and distribute music. In this paper, we explore the effects of digitization and streaming on the globalization of popular music. While some argue that digitization has led to more diverse cultural markets, others consider that the increasing accessibility to international music would result in a globalized market where a few artists garner all the attention. We tackle this debate by looking at how cross-country diversity in music charts has evolved over 4 years in 39 countries. We analyze two large-scale datasets from Spotify, the most popular streaming platform at the moment, and iTunes, one of the pioneers in digital music distribution. Our analysis reveals an upward trend in music consumption diversity that started in 2017 and spans across platforms. There are now significantly more songs, artists, and record labels populating the top charts than just a few years ago, making national charts more diverse from a global perspective. Furthermore, this process started at the peaks of countries’ charts, where diversity increased at a faster pace than at their bases. We characterize these changes as a process of Cultural Divergence, in which countries are increasingly distinct in terms of the music populating their music charts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Revival of positive nostalgic music during the first Covid-19 lockdown in the UK: evidence from Spotify streaming data

The role of population size in folk tune complexity

Elites, communities and the limited benefits of mentorship in electronic music

Introduction.

Digitization is arguably the biggest change the music market has undergone over the last decades. In 2016, digital sales already accounted for more than half of the revenues of the music industry (Coelho and Mendes, 2019 ). There are innumerable aspects on which digitization has impacted how we listen, produce, and commercialize music. For example, digital music is distributed at a null marginal cost, meaning that digital audio can be reproduced ad infinitum without an extra cost on the side of the record label. For the consumer, streaming has had homologous effects. In streaming platforms, listening to new music does not carry an extra monetary cost, as a listener only pays a flat monthly fee to subscribe to a platform like Spotify Footnote 1 . This way, time and search costs are the only ones remaining in the way of music exploration. On the distribution side, online catalogs of music are orders of magnitude larger than those of physical stores due to the lack of space constraints, making a more diverse offer of music (Anderson, 2006 ). There is evidence that the increased availability of music has been accompanied by an enhanced diversity and quantity of music consumption (Datta et al., 2018 ). In this paper, we explore the evolution of global diversity in the past years and find a clear trend towards global diversity in the music market.

Concerns of Cultural Convergence have been part of the public debate for decades. European governments, in particular, have made attempts to protect national cultural industries either directly (e.g. radio quotas) or indirectly (e.g. subsidizing national film production) (Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010 ; Waldfogel, 2018 ). Because digitization granted easier access to imported goods, predictions were that national cultural products were doomed, especially in smaller countries. Nonetheless, scientific research has not yet provided a definitive answer to whether this fear was well-grounded or not. There is evidence that digitization might have accelerated cultural convergence across countries in popular music (Gomez-Herrera et al., 2014 ; Verboord and Brandellero, 2018 ) while others find an increasing interest in national artists (Achterberg et al., 2011 ; Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010 ). Discrepancies most likely stem from the inconsistency in the sample of countries included in these studies and the limited granularity of data available. Therefore, the question of whether digitization and streaming are currently propelling cultural convergence is open for debate. For similar cultural products, such as YouTube videos, global convergence is limited by cultural values (Park et al., 2017 ).

The recent availability of datasets on music consumption across large numbers of countries has provided a way of overcoming some limitations of previous studies. In a recent example, Way and his collaborators, look at Spotify users’ listening behavior and find that “home bias”—the preference towards national artists—is on the rise globally (Way et al., 2020 ). A source of concern is the possible influence of a platform’s endogenous processes on the behavior of its users. For instance, what appears as an enhanced preference for national artists could be the result of changes in the recommendation algorithm. Alternatively, increased popularity of playlists like the New Music Friday, which are biased towards national artists (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018a ) could produce a similar effect. Although far from common, major changes in the recommendation system of Spotify happen, the latest one being announced in March of 2019 (Spotify, 2019 ). As a result, recommendations are now more personalized, which, if the nationality of a user is taken into account, could generate increasing divergence between countries by feeding users with national music. According to Spotify, up to one-fifth of their streams can be attributed to algorithmic recommendations (Anderson et al., 2020 ), which may be enough to sway macro-level trends in music consumption.

We deal with platform-specific confounders by supplementing our analysis of Spotify data with a dataset from iTunes. It must be noted, however, that changes similarly affecting both platforms may exist, such as the increasing use of recommendation systems or catalog expansions, as well as the mutual influence that would make these observations non-independent. Another caveat of using platform-specific data is the fact that users of such platforms might not be representative of the entire population. Spotify users are disproportionately young and male when compared to their countries’ population (Datta et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, the composition of users of a platform is in constant change and the timing of adoption correlates with individual listening habits. For instance, in Spotify, late adopters have a stronger preference for local music than those who joined the platform early on (Way et al., 2020 ). To minimize the impact of these issues, we reduce the sample of countries from the 59 available to 39, keeping those in which Spotify is strongly established. Therefore, we expect the population of users in these countries to be more stable than in recently incorporated ones such as India, in which market penetration is quickly expanding. Additionally, this can be considered as a within-sample comparison (Salganik, 2019 ), which, given the large user base of Spotify, is of interest in and on itself.

In this paper, we tackle the question of whether digitized music consumption is globalizing or not by looking at the ecology of the national music charts of Spotify and iTunes in the past few years. In other words, by observing the global diversity in the charts we can discern whether popular music is converging or diverging across countries. More diversity across countries would be a sign of Cultural Divergence. On the other hand, a decrease in diversity would be indicative of a process of Cultural Convergence across countries. We utilize the Rao-Stirling measure of diversity and its components (Stirling, 2007 ) to describe these trends. We find upward trends in the cross-national diversity of songs, artists, and labels, starting in 2017 in Spotify as well as in iTunes and ending in 2020 for Spotify. Popular music is thus diverging across countries in what we define as Cultural Divergence. To complement previous studies, we also look at the diversity of artists and labels and find that these have increased in parallel. Ultimately, this paper describes trends in popular music across a large sample of countries, giving a more clear perspective of the cultural dynamics in the digital era.

Research background

Winner-takes-all.

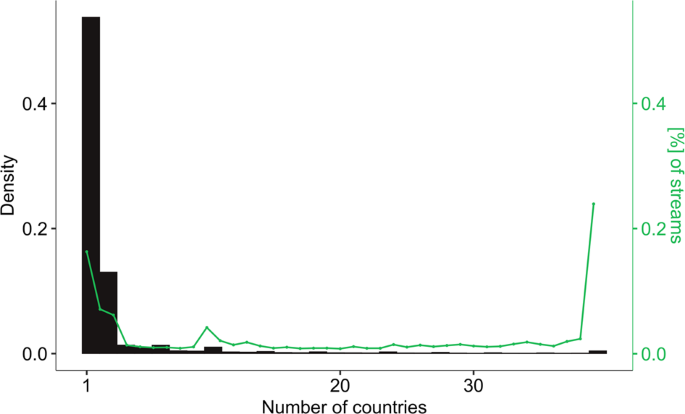

Cultural markets often exhibit a highly skewed distribution of success (e.g. Keuschnigg, 2015 , Salganik et al., 2006 ). In the music market in particular, a few hits expand across the globe while the majority of popular songs only hoard local success (see Fig. 1 ). Such inequalities are partly due to the scalability of cultural products, a property that refers to the fact that most of their cost is fixed – although this property does not apply to all cultural markets, being the art field an exception – while marginal costs are relatively low. For instance, once a song is recorded or a book is written, the cost of making another copy is insignificant when compared to the initial cost of producing it, measured in time, creativity, or money, making these products scalable to large audiences. As a result, demand is highly concentrated on the best alternatives, even when they are only marginally better than the rest (Rosen, 1981 ).

Bars represent the percentage of songs that got to the charts of exactly x countries. The green line represents the total number of streams that songs on each bin have accumulated while in the charts, as a measure of popularity in the period of analysis (2017-mid 2020).

Oftentimes this is an oversimplified view, since quality in cultural products is hard to define, and it is perceived (between others) as a function of previous success, thus creating path dependencies in the popularity of cultural products and artists. This process can be viewed as one in which information is accumulated, with consumers relying on it to moderate the quality uncertainty of their selection of cultural products (Giles, 2007 ). Information is aggregated in the form of consumer reviews, sales rankings, or top charts. In a pathbreaking experimental study, Salganik et al. ( 2006 ) found that information on other listener’s musical preferences results in an amplified inequality of popularity when compared to a world of independent listeners. Using social cues in the form of aggregated information might be beneficial for individuals in cultural markets in which preference is a matter of taste, but there are multiple strategies to leverage such information and its fit varies between individuals (Analytis et al., 2018 ). In the case of artists, during their careers, “small differences in talent become magnified in larger earning differences” (Rosen, 1981 ). This “superstar effect”—defined as the previous success of an artist—is the most important predictor of the popularity of a song, even when controlling for other factors (Interiano et al., 2018 ). Thus, the huge inequalities of success stemming from the scalability of cultural products and the social influence mechanisms intervening in their spread allows for the possibility of a few songs and artists to dominate the charts across the globe.

In principle, both scalability, as well as social influence processes, may have gained bearing after digitization and streaming. On the one hand, digitization reduced the marginal costs of music production by eliminating the need to manufacture an album. Some transaction costs for digital music remain, such as copyrights and distributing platform fees, but overall, the barriers for music to flow across countries are substantially lower than in the pre-digital era. On the other hand, information is more abundant than ever before. Users can get near-real-time data on the listening decisions of millions of other users. On Spotify, anyone can search through the Top 50 playlists tailored for every country. Each of them contains the most popular songs on the platform, which are updated daily. These playlists are extremely popular among users, for instance, the Top 50 Global has over 15 million followers. This deluge of information is complemented with second-order feedback effects (Easley and Kleinberg, 2010 ) such as recommender systems, which might be luring listeners towards the most popular songs. For Spotify, there is evidence that users who rely more heavily on algorithmic recommendations listen to less diverse music and podcasts than those who discover music for themselves (Anderson et al., 2020 , Holtz et al., 2020 ). In short, there are arguments to think that the winner-takes-all effects characteristic of the music market might be gaining bearing under the digital regime, decreasing the diversity and increasing the concentration of the market in the hands of a few hit songs, superstar artists, and major labels.

The long tail

The idea of the long tail, first proposed by Anderson ( 2004 ) in a widely circulated press article sustains that online retailing has led to increased diversity in the consumption of music. This happened because online retailers do not have the limitations of shelf space that traditional brick-and-mortar stores have, and so their catalogs can be virtually unlimited in size. The unlimited digital space can be filled with niche products that do not attract huge audiences but, bit by bit, make a difference in terms of profits generated. In the book following his article, Anderson ( 2006 ) goes beyond the original argument, suggesting that the Internet has a carrying capacity for cultural products previously unattainable and its impact on cultural markets has been broader than initially expected. Not only the distribution but also the production of cultural goods has thrived as a result of the new technologies for distribution (e.g. online retailers), production (e.g. cheaper software), and consumption (e.g. flat fees). Some have even qualified these changes as a renaissance of cultural markets (Waldfogel, 2018 ).

More recently, Aguiar and Waldfogel have argued that the idea of the long tail fails to account for the unpredictability of success in cultural markets (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b ; Waldfogel, 2017 , 2020 ). When confronted with new artists, for instance, record labels have a scant capacity to assess what will be the success of those artists. Under such uncertainty, producers strive to pick those with better prospects but there will inevitably be miscalculations (e.g. the infamous Decca audition of The Beatles) and artists that were deemed unworthy of being promoted will end up reaping huge success, and the same in the opposite direction. In other words, before digitization, market intermediaries held most of the decision power over which products or artists were worthy of being produced and which ones did not, the inevitable result of which was that some hits were lost. The reduced costs of production and promotion of digital cultural goods have made possible the production of these products. Unlike what the original idea of the long tail proposed, not all of them will be niche products and some will end up achieving unexpected popularity. The same goes for independent record labels, which now have better opportunities to promote their artists even with small budgets. There is evidence that indie artists and labels have gained relevance under the digital music regime (Coelho and Mendes, 2019 ). For instance, top-selling albums in the US produced by independent labels increased from 12% in 2000 to 35% in 2010 (Waldfogel, 2015 ).

Waldfogel and Aguiar refer to this phenomenon as the random long tail of music production. The random long tail contains those cultural goods that despite not being attractive to traditional intermediaries can be brought into production and, due to the inherent unpredictability of cultural markets, sometimes reach unexpected success. Accordingly, the more unpredictable a cultural market is, the greater the number of unexpected hits. For instance, the success of songs is more difficult to predict than that of movies, whose box-office earnings heavily depend on the budget and cast of the film (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b ). In summary, these studies put forward a vision of the music market in the digital era as more diverse and unpredictable.

Methods and data

Although there are multiple approaches to the study of diversity in social phenomena, Stirling’s ( 2007 ) is one of the most influential and widely applied. More importantly, the Rao–Stirling diversity index has already been used to study diversity in music taste, although at a different level of analysis than here (Park et al., 2015 ; Way et al., 2019 ). The Rao–Stirling index consists of three components: variety, balance, and disparity.

Variety is a function of the number of distinct units (songs, artists, or labels) in the charts on a given day. The more unique units the more variety there is in the charts. Naturally, in the case of songs variety is bounded by the fact that the same song cannot occupy more than one chart position per country so changes in variety should be interpreted, rather than the absolute size of the indicators (which also applies to the other measures of song diversity). We measure variety as the number of distinct units divided by the total number of chart positions. Balance refers to how evenly distributed the system is across units. Here we measure balance as 1−Gini, a common measure of the inequality of a distribution. In this case, it is the distribution of chart positions across songs, artists, or labels. The more equally distributed positions are the higher the balance in the system. Importantly, balance does not give any information about the number of units in the charts (variety). For instance, label balance would be highest if two labels produce all the songs in the charts with equal shares as well as if every song in the charts was produced by a different label (and there were no songs in more than one chart-country). The disparity is defined not by categories themselves but by the qualities of such categories or elements. In other words, the disparity is a measure of how different the elements of a system are. We define the qualities of a song by its acoustic features Footnote 2 and then calculate the euclidean distance between songs. In the case of artists, we define them by the central tendency of the acoustic features of their songs on the charts. The Rao–Stirling index combines variety, balance, and disparity into a single indicator of diversity Footnote 3 .

Additionally, we introduce Zeta diversity, a measure from biology. Zeta diversity was developed by Hui and McGeoch ( 2014 ) to tackle the issues with pairwise measures of diversity. Aggregated pairwise distance measures are consistently biased (Baselga, 2013 ) and, when the number of sites (countries) is large, they approximate their upper limit (Hui and McGeoch, 2014 ). More importantly, Zeta diversity gives a more nuanced view of the interplay between global and local hits. The distribution of the number of countries in which a song reaches the charts is right-skewed, as shown in Fig. 1 , meaning that most songs enter the charts of just one or two countries. As a consequence, what aggregated measures such as Rao–Stirling mainly capture is the effect of local hits. The influence of global hits is mostly null in such measures because of their paucity. Zeta diversity, on the other hand, measures distances at multiple orders. For instance, Zeta of order 3 ( ζ 3 ) represents the expected number of songs shared by groups of three countries. It is calculated by looking at all possible combinations of three countries and calculating the number of songs that each group shares. Higher orders or Zeta (e.g. songs shared by groups of 10 or more countries) capture the prevalence of more global hits. Here, we characterize Zeta by its central tendency, but other options are possible. As the order of Zeta increases its value decreases monotonically since there are always fewer songs charting in groups of three countries than in groups of two. In short, Zeta diversity gives us a more nuanced view of the distribution of success of songs across the charts compared to other diversity measures.

The data for the study comes from Spotify’s top 200 charts and iTunes’ top 100. We illustrate the analysis focusing on Spotify’s data because of the larger sample of countries (39 vs. 19). The entire list of countries can be found in Supplementary Table S1 online. Because iTunes data could not be retrieved from an official source (instead we obtained it through Kworb.com), the results are reported only as a means of externally validating our main findings. Spotify’s data covers the period from 2017-01-01 to 2020-06-20, iTunes top 100 daily charts for the period 2013-08-14 to 2020-07-16.

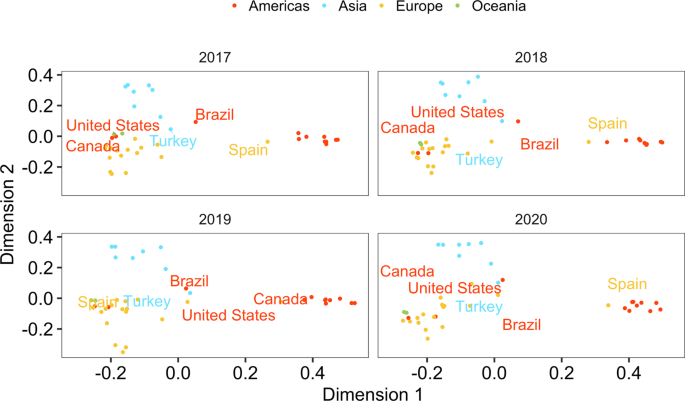

Figure 2 shows distances between countries as a function of the songs shared between their charts within a year. Countries appear geographically clustered. One cluster is formed by Western countries of which Spain is the exception, being part of a different cluster, together with the Latin American countries. The third cluster encapsulates the Asian countries and Brazil. There are some noticeable anomalies, such as the closeness between Turkey and Brazil. Upon closer examination, most of the songs shared between them are produced in the United States. This is likely the result of the small market penetration of Spotify, making for a user base of early adopters more internationally oriented. Alternatively, it could be the result of a small catalog of local music. In any case, the observable consequence is an over-representation of international (and mainly US) hits in both countries’ charts.

Jaccard distances calculated over annually constructed incidence matrices. Countries are colored according to the continent they belong to (red: Americas, yellow: Europe, blue: Asia, Green: Oceania).

Although positions are fairly stable over the years, if anything, clusters of countries seem to consolidate, being these three groups more clearly discernible in 2020 than in 2017. Following Park et al. ( 2017 ) we also look at the relationship between countries as a projection of the two-mode network between countries and songs. The modularity of the network indicates the degree to which countries are clustered into modules beyond what would be expected on a random network. Modularity increased consistently from 2017 up to 2020 (see Supplementary Fig. S4 ) indicating that countries within clusters are becoming more similar in their music charts and, at the same time, drifting away from other clusters. These results are consistent with general notions of cultural, geographical, and linguistic distance which elsewhere have been proved to be the main determinants of music taste similarities between countries (Moore et al., 2014 ; Pichl et al., 2017 ; Schedl et al., 2017 ) although with a few exceptions such as the above-mentioned.

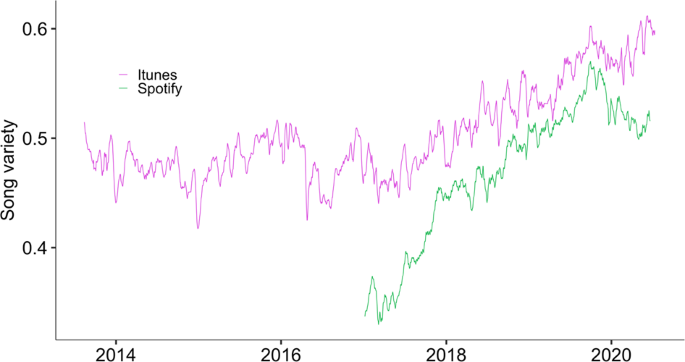

Seen as a whole, the diversity of songs, artists, and labels has increased during this period. Variety has grown not only on Spotify but on iTunes as well (Fig. 3 ). The resemblance between the two trends is startling, especially if we consider how different these platforms are, one being a streaming platform with growing popularity (Spotify) while the other (iTunes) is a digital music shop whose user base is in decay. The resemblance between the trends points to the external validity of the observations, although there could be some degree of influence between the platforms and thus they cannot be regarded as completely independent observations. The upward tendency in variety starts in 2017 and plateaus at the end of 2019 on Spotify while it keeps increasing in iTunes.

Values range from 0 (same set of songs in every country) to 1 (no overlap between the charts). Calculated for countries in both datasets (16 countries) and the same chart size (100 positions). Time series are calculated with daily frequency and smoothed over a 10-day window. Both Spotify and iTunes display consistent trends of increasing variety over time.

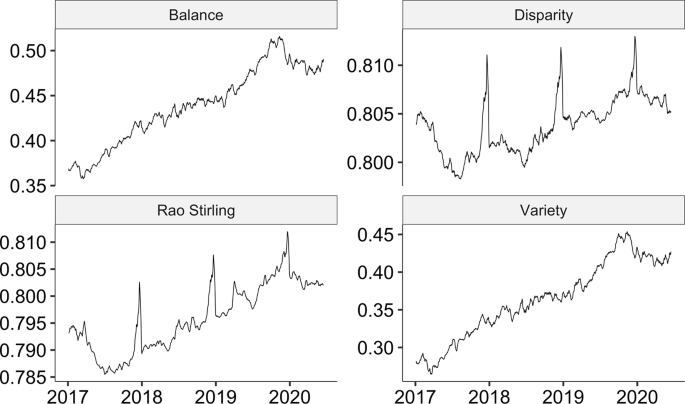

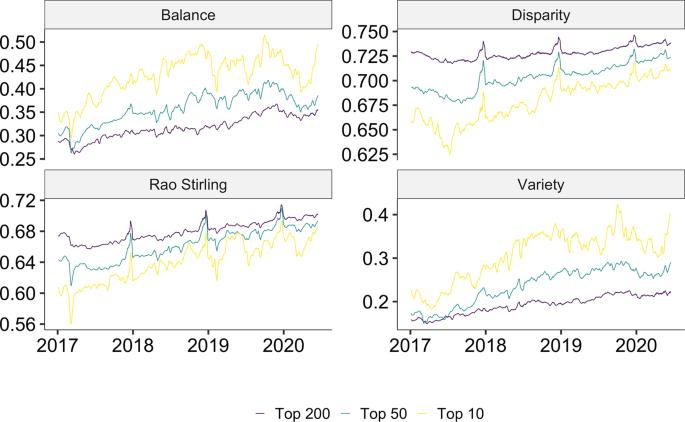

The increase in song diversity can be observed in Fig. 4 . Balance, disparity, and variety have all increased during the period. The disparity indicator also shows a strong seasonal burst around Christmas. This is consistent with other findings, suggesting that in countries in the Northern Hemisphere musical intensity declines around Christmas while the opposite is true for the Southern Hemisphere (Park et al., 2019 ). Overall diversity (Rao–Stirling index) rises from 2017 up to 2020 and then plateaus. Hence, not only there are more distinct songs in the charts (variety) but these are acoustically more dissimilar (disparity) and their distribution over the chart slots is more equal (balance) than at the beginning of the period.

Diversity, measured as balance, disparity, variety, or a combination of them, has been increasing consistently across countries with a plateau at the beginning of the year 2020. Besides the secular growth, disparity shows a strong seasonal component centered around Christmas.

As for songs, the diversity of artists has also grown. However, the trend is distinct at the head of the charts than at the bottom. By slicing charts at certain ranking positions we create a top 10, top 50, and top 200 for each country. When it comes to balance and variety, the increase has been more pronounced at the head of the charts, which already presented a higher level at the beginning of the observed period. However, disparity is lowest within the top 10, indicating that the group of artists with songs on the head of the charts are stylistically more similar than those who just make it to the charts (a group that subsumes the former). What we can derive from these trends is that, while there are proportionally more unique artists at the top of the charts, the music that those artists produce is relatively similar, as if there was an acoustic “recipe” for reaching the peak of the charts. In general, artist diversity as a whole has increased at a similar pace across strata of the charts (Fig. 5 c).

All the components of artist diversity have increased steadily during the period. As for songs, artist disparity bursts around Christmas. While balance and variety are higher at the peak of the charts, disparity shows the opposite pattern.

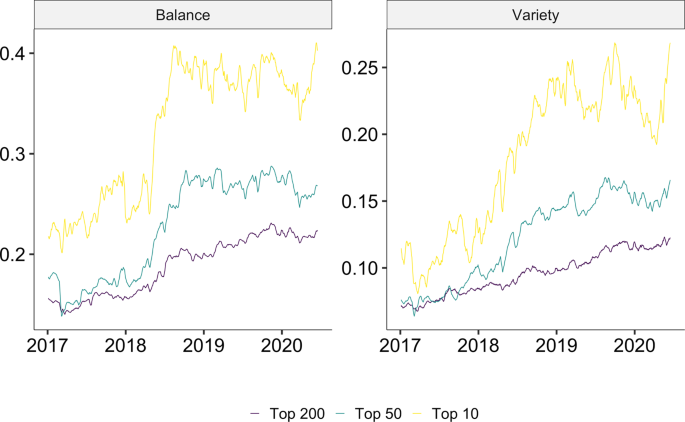

The increasing diversity of songs and artists in the charts has been accompanied by a more equally distributed market for record labels (Fig. 6 a). Again, the trend is steeper if we look only at the head of the charts. The number of distinct labels with at least one song in the charts has also increased in a stratified manner (Fig. 6 b). In general, labels had on average fewer artists and songs on the charts at the end of the period. While in the first 6 months of 2017 labels had on average 5.88 songs on the charts (and 2.19 artists), for the first half of 2020 it was one less song (and only 1.66 artists). Interestingly, the number of songs that each artist got on the charts has increased slightly, going from 2.67 in 2017 to 2.96 in 2020 (comparing the first half of each year).

The left panel shows the balance of labels over time for three sizes of the top chart, displaying increases over time especially for the highest positions in the chart. The right panel shows the variety of labels on the charts. The same patterns as for balance can be observed.

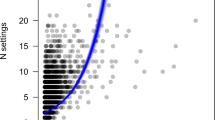

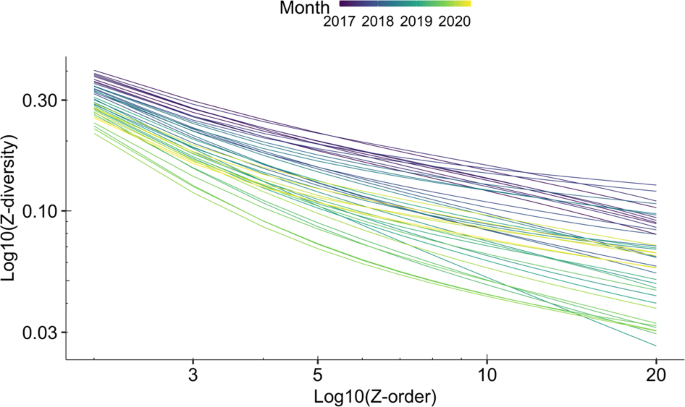

We can take a closer look at the interplay between local and global hits through the Zeta diversity measure. Figure 7 presents the results for monthly Zeta diversity measures of orders 2—which is equivalent to pairwise distances—up to 20—the mean number of common songs shared by groups of 20 countries. We observe that across all orders of Zeta the mean diversity tends to decrease with time (brighter colors) which is consistent with the previous results Footnote 4 . When we look at the decay of Z -values along orders of Zeta ( x -axis) we observe that it gets steeper over time. In other words, the slope of the regression with Z -values ( y -axis) as a dependent variable and Z -order ( x -axis) as a predictor gets greater with time. Table 1 presents the results of a linear regression model that shows the increase in steepness over time. The substantive interpretation is that global hits have taken the lion’s share of the increase in diversity, becoming an increasingly rare phenomenon.

The x -axis represents the order of Zeta and the y -axis the z -value, or mean percentage of songs shared across groups of x countries. Both axes are represented on a log10 scale. The function of Zeta with order shifts down over time and becomes steeper.