- Study Protocol

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2024

Learning effect of online versus onsite education in health and medical scholarship – protocol for a cluster randomized trial

- Rie Raffing 1 ,

- Lars Konge 2 &

- Hanne Tønnesen 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 927 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

123 Accesses

Metrics details

The disruption of health and medical education by the COVID-19 pandemic made educators question the effect of online setting on students’ learning, motivation, self-efficacy and preference. In light of the health care staff shortage online scalable education seemed relevant. Reviews on the effect of online medical education called for high quality RCTs, which are increasingly relevant with rapid technological development and widespread adaption of online learning in universities. The objective of this trial is to compare standardized and feasible outcomes of an online and an onsite setting of a research course regarding the efficacy for PhD students within health and medical sciences: Primarily on learning of research methodology and secondly on preference, motivation, self-efficacy on short term and academic achievements on long term. Based on the authors experience with conducting courses during the pandemic, the hypothesis is that student preferred onsite setting is different to online setting.

Cluster randomized trial with two parallel groups. Two PhD research training courses at the University of Copenhagen are randomized to online (Zoom) or onsite (The Parker Institute, Denmark) setting. Enrolled students are invited to participate in the study. Primary outcome is short term learning. Secondary outcomes are short term preference, motivation, self-efficacy, and long-term academic achievements. Standardized, reproducible and feasible outcomes will be measured by tailor made multiple choice questionnaires, evaluation survey, frequently used Intrinsic Motivation Inventory, Single Item Self-Efficacy Question, and Google Scholar publication data. Sample size is calculated to 20 clusters and courses are randomized by a computer random number generator. Statistical analyses will be performed blinded by an external statistical expert.

Primary outcome and secondary significant outcomes will be compared and contrasted with relevant literature. Limitations include geographical setting; bias include lack of blinding and strengths are robust assessment methods in a well-established conceptual framework. Generalizability to PhD education in other disciplines is high. Results of this study will both have implications for students and educators involved in research training courses in health and medical education and for the patients who ultimately benefits from this training.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05736627. SPIRIT guidelines are followed.

Peer Review reports

Medical education was utterly disrupted for two years by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the midst of rearranging courses and adapting to online platforms we, with lecturers and course managers around the globe, wondered what the conversion to online setting did to students’ learning, motivation and self-efficacy [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. What the long-term consequences would be [ 4 ] and if scalable online medical education should play a greater role in the future [ 5 ] seemed relevant and appealing questions in a time when health care professionals are in demand. Our experience of performing research training during the pandemic was that although PhD students were grateful for courses being available, they found it difficult to concentrate related to the long screen hours. We sensed that most students preferred an onsite setting and perceived online courses a temporary and inferior necessity. The question is if this impacted their learning?

Since the common use of the internet in medical education, systematic reviews have sought to answer if there is a difference in learning effect when taught online compared to onsite. Although authors conclude that online learning may be equivalent to onsite in effect, they agree that studies are heterogeneous and small [ 6 , 7 ], with low quality of the evidence [ 8 , 9 ]. They therefore call for more robust and adequately powered high-quality RCTs to confirm their findings and suggest that students’ preferences in online learning should be investigated [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

This uncovers two knowledge gaps: I) High-quality RCTs on online versus onsite learning in health and medical education and II) Studies on students’ preferences in online learning.

Recently solid RCTs have been performed on the topic of web-based theoretical learning of research methods among health professionals [ 10 , 11 ]. However, these studies are on asynchronous courses among medical or master students with short term outcomes.

This uncovers three additional knowledge gaps: III) Studies on synchronous online learning IV) among PhD students of health and medical education V) with long term measurement of outcomes.

The rapid technological development including artificial intelligence (AI) and widespread adaption as well as application of online learning forced by the pandemic, has made online learning well-established. It represents high resolution live synchronic settings which is available on a variety of platforms with integrated AI and options for interaction with and among students, chat and break out rooms, and exterior digital tools for teachers [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Thus, investigating online learning today may be quite different than before the pandemic. On one hand, it could seem plausible that this technological development would make a difference in favour of online learning which could not be found in previous reviews of the evidence. On the other hand, the personal face-to-face interaction during onsite learning may still be more beneficial for the learning process and combined with our experience of students finding it difficult to concentrate when online during the pandemic we hypothesize that outcomes of the onsite setting are different from the online setting.

To support a robust study, we design it as a cluster randomized trial. Moreover, we use the well-established and widely used Kirkpatrick’s conceptual framework for evaluating learning as a lens to assess our outcomes [ 15 ]. Thus, to fill the above-mentioned knowledge gaps, the objective of this trial is to compare a synchronous online and an in-person onsite setting of a research course regarding the efficacy for PhD students within the health and medical sciences:

Primarily on theoretical learning of research methodology and

Secondly on

◦ Preference, motivation, self-efficacy on short term

◦ Academic achievements on long term

Trial design

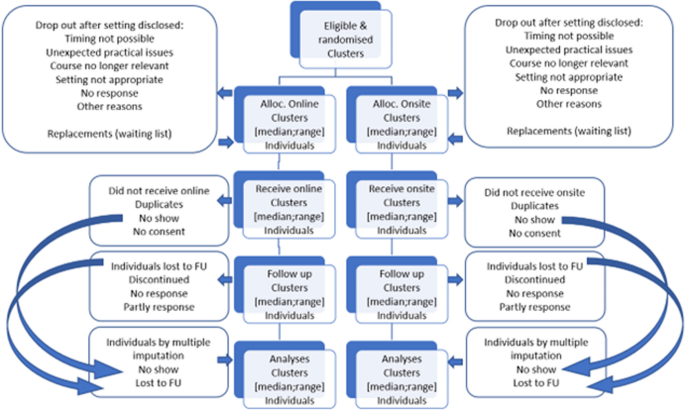

This study protocol covers synchronous online and in-person onsite setting of research courses testing the efficacy for PhD students. It is a two parallel arms cluster randomized trial (Fig. 1 ).

Consort flow diagram

The study measures baseline and post intervention. Baseline variables and knowledge scores are obtained at the first day of the course, post intervention measurement is obtained the last day of the course (short term) and monthly for 24 months (long term).

Randomization is stratified giving 1:1 allocation ratio of the courses. As the number of participants within each course might differ, the allocation ratio of participants in the study will not fully be equal and 1:1 balanced.

Study setting

The study site is The Parker Institute at Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. From here the courses are organized and run online and onsite. The course programs and time schedules, the learning objective, the course management, the lecturers, and the delivery are identical in the two settings. The teachers use the same introductory presentations followed by training in break out groups, feed-back and discussions. For the online group, the setting is organized as meetings in the online collaboration tool Zoom® [ 16 ] using the basic available technicalities such as screen sharing, chat function for comments, and breakout rooms and other basics digital tools if preferred. The online version of the course is synchronous with live education and interaction. For the onsite group, the setting is the physical classroom at the learning facilities at the Parker Institute. Coffee and tea as well as simple sandwiches and bottles of water, which facilitate sociality, are available at the onsite setting. The participants in the online setting must get their food and drink by themselves, but online sociality is made possible by not closing down the online room during the breaks. The research methodology courses included in the study are “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research”, (see course programme in appendix 1) and “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” [ 17 ] (see course programme in appendix 2). The two courses both have 12 seats and last either three or three and a half days resulting in 2.2 and 2.6 ECTS credits, respectively. They are offered by the PhD School of the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. Both courses are available and covered by the annual tuition fee for all PhD students enrolled at a Danish university.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for participants: All PhD students enrolled on the PhD courses participate after informed consent: “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” at the PhD School of the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Exclusion criteria for participants: Declining to participate and withdrawal of informed consent.

Informed consent

The PhD students at the PhD School at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen participate after informed consent, taken by the daily project leader, allowing evaluation data from the course to be used after pseudo-anonymization in the project. They are informed in a welcome letter approximately three weeks prior to the course and again in the introduction the first course day. They register their consent on the first course day (Appendix 3). Declining to participate in the project does not influence their participation in the course.

Interventions

Online course settings will be compared to onsite course settings. We test if the onsite setting is different to online. Online learning is increasing but onsite learning is still the preferred educational setting in a medical context. In this case onsite learning represents “usual care”. The online course setting is meetings in Zoom using the technicalities available such as chat and breakout rooms. The onsite setting is the learning facilities, at the Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, The Capital Region, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The course settings are not expected to harm the participants, but should a request be made to discontinue the course or change setting this will be met, and the participant taken out of the study. Course participants are allowed to take part in relevant concomitant courses or other interventions during the trial.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

Course participants are motivated to complete the course irrespectively of the setting because it bears ECTS-points for their PhD education and adds to the mandatory number of ECTS-points. Thus, we expect adherence to be the same in both groups. However, we monitor their presence in the course and allocate time during class for testing the short-term outcomes ( motivation, self-efficacy, preference and learning). We encourage and, if necessary, repeatedly remind them to register with Google Scholar for our testing of the long-term outcome (academic achievement).

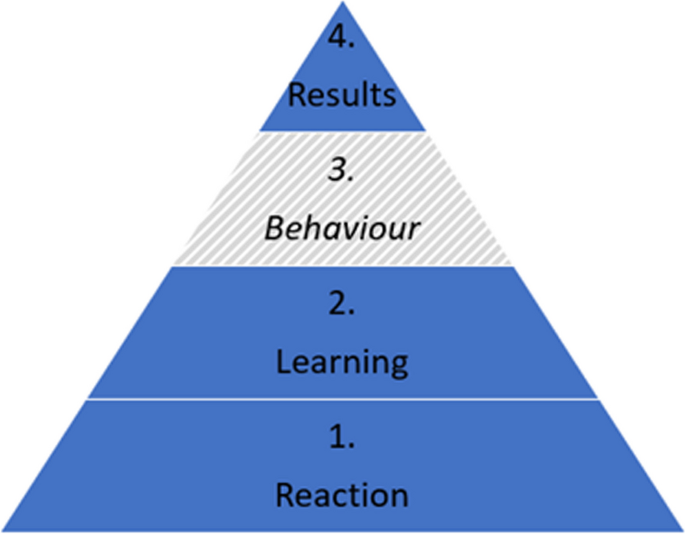

Outcomes are related to the Kirkpatrick model for evaluating learning (Fig. 2 ) which divides outcomes into four different levels; Reaction which includes for example motivation, self-efficacy and preferences, Learning which includes knowledge acquisition, Behaviour for practical application of skills when back at the job (not included in our outcomes), and Results for impact for end-users which includes for example academic achievements in the form of scientific articles [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

The Kirkpatrick model

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is short term learning (Kirkpatrick level 2).

Learning is assessed by a Multiple-Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) developed prior to the RCT specifically for this setting (Appendix 4). First the lecturers of the two courses were contacted and asked to provide five multiple choice questions presented as a stem with three answer options; one correct answer and two distractors. The questions should be related to core elements of their teaching under the heading of research training. The questions were set up to test the cognition of the students at the levels of "Knows" or "Knows how" according to Miller's Pyramid of Competence and not their behaviour [ 21 ]. Six of the course lecturers responded and out of this material all the questions which covered curriculum of both courses were selected. It was tested on 10 PhD students and within the lecturer group, revised after an item analysis and English language revised. The MCQ ended up containing 25 questions. The MCQ is filled in at baseline and repeated at the end of the course. The primary outcomes based on the MCQ is estimated as the score of learning calculated as number of correct answers out of 25 after the course. A decrease of points of the MCQ in the intervention groups denotes a deterioration of learning. In the MCQ the minimum score is 0 and 25 is maximum, where 19 indicates passing the course.

Furthermore, as secondary outcome, this outcome measurement will be categorized as binary outcome to determine passed/failed of the course defined by 75% (19/25) correct answers.

The learning score will be computed on group and individual level and compared regarding continued outcomes by the Mann–Whitney test comparing the learning score of the online and onsite groups. Regarding the binomial outcome of learning (passed/failed) data will be analysed by the Fisher’s exact test on an intention-to-treat basis between the online and onsite. The results will be presented as median and range and as mean and standard deviations, for possible future use in meta-analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Motivation assessment post course: Motivation level is measured by the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) Scale [ 22 ] (Appendix 5). The IMI items were randomized by random.org on the 4th of August 2022. It contains 12 items to be assessed by the students on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 is “Not at all true”, 4 is “Somewhat true” and 7 is “Very true”. The motivation score will be computed on group and individual level and will then be tested by the Mann–Whitney of the online and onsite group.

Self-efficacy assessment post course: Self-efficacy level is measured by a single-item measure developed and validated by Williams and Smith [ 23 ] (Appendix 6). It is assessed by the students on a scale from 1–10 where 1 is “Strongly disagree” and 10 is “Strongly agree”. The self-efficacy score will be computed on group and individual level and tested by a Mann–Whitney test to compare the self-efficacy score of the online and onsite group.

Preference assessment post course: Preference is measured as part of the general course satisfaction evaluation with the question “If you had the option to choose, which form would you prefer this course to have?” with the options “onsite form” and “online form”.

Academic achievement assessment is based on 24 monthly measurements post course of number of publications, number of citations, h-index, i10-index. This data is collected through the Google Scholar Profiles [ 24 ] of the students as this database covers most scientific journals. Associations between onsite/online and long-term academic will be examined with Kaplan Meyer and log rank test with a significance level of 0.05.

Participant timeline

Enrolment for the course at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, becomes available when it is published in the course catalogue. In the course description the course location is “To be announced”. Approximately 3–4 weeks before the course begins, the participant list is finalized, and students receive a welcome letter containing course details, including their allocation to either the online or onsite setting. On the first day of the course, oral information is provided, and participants provide informed consent, baseline variables, and base line knowledge scores.

The last day of scheduled activities the following scores are collected, knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy, setting preference, and academic achievement. To track students' long term academic achievements, follow-ups are conducted monthly for a period of 24 months, with assessments occurring within one week of the last course day (Table 1 ).

Sample size

The power calculation is based on the main outcome, theoretical learning on short term. For the sample size determination, we considered 12 available seats for participants in each course. To achieve statistical power, we aimed for 8 clusters in both online and onsite arms (in total 16 clusters) to detect an increase in learning outcome of 20% (learning outcome increase of 5 points). We considered an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.02, a standard deviation of 10, a power of 80%, and a two-sided alpha level of 5%. The Allocation Ratio was set at 1, implying an equal number of subjects in both online and onsite group.

Considering a dropout up to 2 students per course, equivalent to 17%, we determined that a total of 112 participants would be needed. This calculation factored in 10 clusters of 12 participants per study arm, which we deemed sufficient to assess any changes in learning outcome.

The sample size was estimated using the function n4means from the R package CRTSize [ 25 ].

Recruitment

Participants are PhD students enrolled in 10 courses of “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and 10 courses of “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” at the PhD School of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Assignment of interventions: allocation

Randomization will be performed on course-level. The courses are randomized by a computer random number generator [ 26 ]. To get a balanced randomization per year, 2 sets with 2 unique random integers in each, taken from the 1–4 range is requested.

The setting is not included in the course catalogue of the PhD School and thus allocation to online or onsite is concealed until 3–4 weeks before course commencement when a welcome letter with course information including allocation to online or onsite setting is distributed to the students. The lecturers are also informed of the course setting at this time point. If students withdraw from the course after being informed of the setting, a letter is sent to them enquiring of the reason for withdrawal and reason is recorded (Appendix 7).

The allocation sequence is generated by a computer random number generator (random.org). The participants and the lecturers sign up for the course without knowing the course setting (online or onsite) until 3–4 weeks before the course.

Assignment of interventions: blinding

Due to the nature of the study, it is not possible to blind trial participants or lecturers. The outcomes are reported by the participants directly in an online form, thus being blinded for the outcome assessor, but not for the individual participant. The data collection for the long-term follow-up regarding academic achievements is conducted without blinding. However, the external researcher analysing the data will be blinded.

Data collection and management

Data will be collected by the project leader (Table 1 ). Baseline variables and post course knowledge, motivation, and self-efficacy are self-reported through questionnaires in SurveyXact® [ 27 ]. Academic achievements are collected through Google Scholar profiles of the participants.

Given that we are using participant assessments and evaluations for research purposes, all data collection – except for monthly follow-up of academic achievements after the course – takes place either in the immediate beginning or ending of the course and therefore we expect participant retention to be high.

Data will be downloaded from SurveyXact and stored in a locked and logged drive on a computer belonging to the Capital Region of Denmark. Only the project leader has access to the data.

This project conduct is following the Danish Data Protection Agency guidelines of the European GDPR throughout the trial. Following the end of the trial, data will be stored at the Danish National Data Archive which fulfil Danish and European guidelines for data protection and management.

Statistical methods

Data is anonymized and blinded before the analyses. Analyses are performed by a researcher not otherwise involved in the inclusion or randomization, data collection or handling. All statistical tests will be testing the null hypotheses assuming the two arms of the trial being equal based on corresponding estimates. Analysis of primary outcome on short-term learning will be started once all data has been collected for all individuals in the last included course. Analyses of long-term academic achievement will be started at end of follow-up.

Baseline characteristics including both course- and individual level information will be presented. Table 2 presents the available data on baseline.

We will use multivariate analysis for identification of the most important predictors (motivation, self-efficacy, sex, educational background, and knowledge) for best effect on short and long term. The results will be presented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The results will be considered significant if CI does not include the value one.

All data processing and analyses were conducted using R statistical software version 4.1.0, 2021–05-18 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

If possible, all analysis will be performed for “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and for “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” separately.

Primary analyses will be handled with the intention-to-treat approach. The analyses will include all individuals with valid data regardless of they did attend the complete course. Missing data will be handled with multiple imputation [ 28 ] .

Upon reasonable request, public assess will be granted to protocol, datasets analysed during the current study, and statistical code Table 3 .

Oversight, monitoring, and adverse events

This project is coordinated in collaboration between the WHO CC (DEN-62) at the Parker Institute, CAMES, and the PhD School at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. The project leader runs the day-to-day support of the trial. The steering committee of the trial includes principal investigators from WHO CC (DEN-62) and CAMES and the project leader and meets approximately three times a year.

Data monitoring is done on a daily basis by the project leader and controlled by an external independent researcher.

An adverse event is “a harmful and negative outcome that happens when a patient has been provided with medical care” [ 29 ]. Since this trial does not involve patients in medical care, we do not expect adverse events. If participants decline taking part in the course after receiving the information of the course setting, information on reason for declining is sought obtained. If the reason is the setting this can be considered an unintended effect. Information of unintended effects of the online setting (the intervention) will be recorded. Participants are encouraged to contact the project leader with any response to the course in general both during and after the course.

The trial description has been sent to the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (VEK) (21041907), which assessed it as not necessary to notify and that it could proceed without permission from VEK according to the Danish law and regulation of scientific research. The trial is registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (Privacy) (P-2022–158). Important protocol modification will be communicated to relevant parties as well as VEK, the Joint Regional Information Security and Clinicaltrials.gov within an as short timeframe as possible.

Dissemination plans

The results (positive, negative, or inconclusive) will be disseminated in educational, scientific, and clinical fora, in international scientific peer-reviewed journals, and clinicaltrials.gov will be updated upon completion of the trial. After scientific publication, the results will be disseminated to the public by the press, social media including the website of the hospital and other organizations – as well as internationally via WHO CC (DEN-62) at the Parker Institute and WHO Europe.

All authors will fulfil the ICMJE recommendations for authorship, and RR will be first author of the articles as a part of her PhD dissertation. Contributors who do not fulfil these recommendations will be offered acknowledgement in the article.

This cluster randomized trial investigates if an onsite setting of a research course for PhD students within the health and medical sciences is different from an online setting. The outcomes measured are learning of research methodology (primary), preference, motivation, and self-efficacy (secondary) on short term and academic achievements (secondary) on long term.

The results of this study will be discussed as follows:

Discussion of primary outcome

Primary outcome will be compared and contrasted with similar studies including recent RCTs and mixed-method studies on online and onsite research methodology courses within health and medical education [ 10 , 11 , 30 ] and for inspiration outside the field [ 31 , 32 ]: Tokalic finds similar outcomes for online and onsite, Martinic finds that the web-based educational intervention improves knowledge, Cheung concludes that the evidence is insufficient to say that the two modes have different learning outcomes, Kofoed finds online setting to have negative impact on learning and Rahimi-Ardabili presents positive self-reported student knowledge. These conflicting results will be discussed in the context of the result on the learning outcome of this study. The literature may change if more relevant studies are published.

Discussion of secondary outcomes

Secondary significant outcomes are compared and contrasted with similar studies.

Limitations, generalizability, bias and strengths

It is a limitation to this study, that an onsite curriculum for a full day is delivered identically online, as this may favour the onsite course due to screen fatigue [ 33 ]. At the same time, it is also a strength that the time schedules are similar in both settings. The offer of coffee, tea, water, and a plain sandwich in the onsite course may better facilitate the possibility for socializing. Another limitation is that the study is performed in Denmark within a specific educational culture, with institutional policies and resources which might affect the outcome and limit generalization to other geographical settings. However, international students are welcome in the class.

In educational interventions it is generally difficult to blind participants and this inherent limitation also applies to this trial [ 11 ]. Thus, the participants are not blinded to their assigned intervention, and neither are the lecturers in the courses. However, the external statistical expert will be blinded when doing the analyses.

We chose to compare in-person onsite setting with a synchronous online setting. Therefore, the online setting cannot be expected to generalize to asynchronous online setting. Asynchronous delivery has in some cases showed positive results and it might be because students could go back and forth through the modules in the interface without time limit [ 11 ].

We will report on all the outcomes defined prior to conducting the study to avoid selective reporting bias.

It is a strength of the study that it seeks to report outcomes within the 1, 2 and 4 levels of the Kirkpatrick conceptual framework, and not solely on level 1. It is also a strength that the study is cluster randomized which will reduce “infections” between the two settings and has an adequate power calculated sample size and looks for a relevant educational difference of 20% between the online and onsite setting.

Perspectives with implications for practice

The results of this study may have implications for the students for which educational setting they choose. Learning and preference results has implications for lecturers, course managers and curriculum developers which setting they should plan for the health and medical education. It may also be of inspiration for teaching and training in other disciplines. From a societal perspective it also has implications because we will know the effect and preferences of online learning in case of a future lock down.

Future research could investigate academic achievements in online and onsite research training on the long run (Kirkpatrick 4); the effect of blended learning versus online or onsite (Kirkpatrick 2); lecturers’ preferences for online and onsite setting within health and medical education (Kirkpatrick 1) and resource use in synchronous and asynchronous online learning (Kirkpatrick 5).

Trial status

This trial collected pilot data from August to September 2021 and opened for inclusion in January 2022. Completion of recruitment is expected in April 2024 and long-term follow-up in April 2026. Protocol version number 1 03.06.2022 with amendments 30.11.2023.

Availability of data and materials

The project leader will have access to the final trial dataset which will be available upon reasonable request. Exception to this is the qualitative raw data that might contain information leading to personal identification.

Abbreviations

Artificial Intelligence

Copenhagen academy for medical education and simulation

Confidence interval

Coronavirus disease

European credit transfer and accumulation system

International committee of medical journal editors

Intrinsic motivation inventory

Multiple choice questionnaire

Doctor of medicine

Masters of sciences

Randomized controlled trial

Scientific ethical committee of the Capital Region of Denmark

WHO Collaborating centre for evidence-based clinical health promotion

Samara M, Algdah A, Nassar Y, Zahra SA, Halim M, Barsom RMM. How did online learning impact the academic. J Technol Sci Educ. 2023;13(3):869–85.

Article Google Scholar

Nejadghaderi SA, Khoshgoftar Z, Fazlollahi A, Nasiri MJ. Medical education during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: an umbrella review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1358084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1358084 .

Madi M, Hamzeh H, Abujaber S, Nawasreh ZH. Have we failed them? Online learning self-efficacy of physiotherapy students during COVID-19 pandemic. Physiother Res Int. 2023;5:e1992. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1992 .

Torda A. How COVID-19 has pushed us into a medical education revolution. Intern Med J. 2020;50(9):1150–3.

Alhat S. Virtual Classroom: A Future of Education Post-COVID-19. Shanlax Int J Educ. 2020;8(4):101–4.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1181–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.10.1181 .

Pei L, Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666538. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1666538 .

Richmond H, Copsey B, Hall AM, Davies D, Lamb SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of online versus alternative methods for training licensed health care professionals to deliver clinical interventions. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1047-4 .

George PP, Zhabenko O, Kyaw BM, Antoniou P, Posadzki P, Saxena N, Semwal M, Tudor Car L, Zary N, Lockwood C, Car J. Online Digital Education for Postregistration Training of Medical Doctors: Systematic Review by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e13269. https://doi.org/10.2196/13269 .

Tokalić R, Poklepović Peričić T, Marušić A. Similar Outcomes of Web-Based and Face-to-Face Training of the GRADE Approach for the Certainty of Evidence: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e43928. https://doi.org/10.2196/43928 .

Krnic Martinic M, Čivljak M, Marušić A, Sapunar D, Poklepović Peričić T, Buljan I, et al. Web-Based Educational Intervention to Improve Knowledge of Systematic Reviews Among Health Science Professionals: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(8): e37000.

https://www.mentimeter.com/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

https://www.sendsteps.com/en/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

https://da.padlet.com/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Zackoff MW, Real FJ, Abramson EL, Li STT, Klein MD, Gusic ME. Enhancing Educational Scholarship Through Conceptual Frameworks: A Challenge and Roadmap for Medical Educators. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):135–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.003 .

https://zoom.us/ . Accessed 20 Aug 2024.

Raffing R, Larsen S, Konge L, Tønnesen H. From Targeted Needs Assessment to Course Ready for Implementation-A Model for Curriculum Development and the Course Results. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032529 .

https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/the-kirkpatrick-model/ . Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

Smidt A, Balandin S, Sigafoos J, Reed VA. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(3):266–74.

Campbell K, Taylor V, Douglas S. Effectiveness of online cancer education for nurses and allied health professionals; a systematic review using kirkpatrick evaluation framework. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(2):339–56.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–7.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68 .

Williams GM, Smith AP. Using single-item measures to examine the relationships between work, personality, and well-being in the workplace. Psychology. 2016;07(06):753–67.

https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/citations.html . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Rotondi MA. CRTSize: sample size estimation functions for cluster randomized trials. R package version 1.0. 2015. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=CRTSize .

Random.org. Available from: https://www.random.org/

https://rambollxact.dk/surveyxact . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ (Online). 2009;339:157–60.

Google Scholar

Skelly C, Cassagnol M, Munakomi S. Adverse Events. StatPearls Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558963/ .

Rahimi-Ardabili H, Spooner C, Harris MF, Magin P, Tam CWM, Liaw ST, et al. Online training in evidence-based medicine and research methods for GP registrars: a mixed-methods evaluation of engagement and impact. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8439372/pdf/12909_2021_Article_2916.pdf .

Cheung YYH, Lam KF, Zhang H, Kwan CW, Wat KP, Zhang Z, et al. A randomized controlled experiment for comparing face-to-face and online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Educ. 2023;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1160430 .

Kofoed M, Gebhart L, Gilmore D, Moschitto R. Zooming to Class?: Experimental Evidence on College Students' Online Learning During Covid-19. SSRN Electron J. 2021;IZA Discussion Paper No. 14356.

Mutlu Aİ, Yüksel M. Listening effort, fatigue, and streamed voice quality during online university courses. Logop Phoniatr Vocol :1–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14015439.2024.2317789

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the students who make their evaluations available for this trial and MSc (Public Health) Mie Sylow Liljendahl for statistical support.

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University The Parker Institute, which hosts the WHO CC (DEN-62), receives a core grant from the Oak Foundation (OCAY-18–774-OFIL). The Oak Foundation had no role in the design of the study or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

WHO Collaborating Centre (DEN-62), Clinical Health Promotion Centre, The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg & Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, 2400, Denmark

Rie Raffing & Hanne Tønnesen

Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation (CAMES), Centre for HR and Education, The Capital Region of Denmark, Copenhagen, 2100, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RR, LK and HT have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; RR to the acquisition of data, and RR, LK and HT to the interpretation of data; RR has drafted the work and RR, LK, and HT have substantively revised it AND approved the submitted version AND agreed to be personally accountable for their own contributions as well as ensuring that any questions which relates to the accuracy or integrity of the work are adequately investigated, resolved and documented.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rie Raffing .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics has assessed the study Journal-nr.:21041907 (Date: 21–09-2021) without objections or comments. The study has been approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency Journal-nr.: P-2022–158 (Date: 04.05.2022).

All PhD students participate after informed consent. They can withdraw from the study at any time without explanations or consequences for their education. They will be offered information of the results at study completion. There are no risks for the course participants as the measurements in the course follow routine procedure and they are not affected by the follow up in Google Scholar. However, the 15 min of filling in the forms may be considered inconvenient.

The project will follow the GDPR and the Joint Regional Information Security Policy. Names and ID numbers are stored on a secure and logged server at the Capital Region Denmark to avoid risk of data leak. All outcomes are part of the routine evaluation at the courses, except the follow up for academic achievement by publications and related indexes. However, the publications are publicly available per se.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., supplementary material 2., supplementary material 3., supplementary material 4., supplementary material 5., supplementary material 6., supplementary material 7., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Raffing, R., Konge, L. & Tønnesen, H. Learning effect of online versus onsite education in health and medical scholarship – protocol for a cluster randomized trial. BMC Med Educ 24 , 927 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05915-z

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2024

Accepted : 14 August 2024

Published : 26 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05915-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-efficacy

- Achievements

- Health and Medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- IIEP Buenos Aires

- A global institute

- Governing Board

- Expert directory

- 60th anniversary

- Monitoring and evaluation

Latest news

- Upcoming events

- PlanED: The IIEP podcast

- Partnering with IIEP

- Career opportunities

- 11th Medium-Term Strategy

- Planning and management to improve learning

- Inclusion in education

- Using digital tools to promote transparency and accountability

- Ethics and corruption in education

- Digital technology to transform education

- Crisis-sensitive educational planning

- Rethinking national school calendars for climate-resilient learning

- Skills for the future

- Interactive map

- Foundations of education sector planning programmes

- Online specialized courses

- Customized, on-demand training

- Training in Buenos Aires

- Training in Dakar

- Preparation of strategic plans

- Sector diagnosis

- Costs and financing of education

- Tools for planning

- Crisis-sensitive education planning

- Supporting training centres

- Support for basic education quality management

- Gender at the Centre

- Teacher careers

- Geospatial data

- Cities and Education 2030

- Learning assessment data

- Governance and quality assurance

- School grants

- Early childhood education

- Flexible learning pathways in higher education

- Instructional leaders

- Planning for teachers in times of crisis and displacement

- Planning to fulfil the right to education

- Thematic resource portals

- Policy Fora

- Network of Education Policy Specialists in Latin America

- Strategic Debates

- Publications

- Briefs, Papers, Tools

- Search the collection

- Visitors information

- Planipolis (Education plans and policies)

- IIEP Learning Portal

- Ethics and corruption ETICO Platform

- PEFOP (Vocational Training in Africa)

- SITEAL (Latin America)

- Policy toolbox

- Education for safety, resilience and social cohesion

- Health and Education Resource Centre

- Interactive Map

- Search deploy

- The institute

Defining and measuring the quality of education

Strategic_seminar1.jpg.

What is the quality of education? What are the most important aspects of quality and how can they be measured?

These questions have been raised for a long time and are still widely debated. The current understanding of education quality has considerably benefitted from the conceptual work undertaken through national and international initiatives to assess learning achievement. These provide valuable feedback to policy-makers on the competencies mastered by pupils and youths, and the factors which explain these. But there is also a growing awareness of the importance of values and behaviours, although these are more difficult to measure.

To address these concerns, IIEP organized (on 15 December 2011) a Strategic Debate on “Defining and measuring the quality of education: Is there an emerging consensus?” The topic was approached from the point of view of two cross-national surveys: the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ)*.

Assessing the creativity of students

“Students’ capacity to extrapolate from what they know and apply this creatively in novel situations is more important than what the students know”, said Andreas Schleicher, Head of the Indicators and Analysis Division at the Directorate for Education, OECD, and in charge of PISA. This concept is reflected in current developments taking place in workplaces in many countries, which increasingly require non-routine interactive skills. When comparing the results obtained in different countries, PISA’s experience has shown that “education systems can creatively combine the equity and quality agenda in education”, Schleicher said. Contrary to conventional wisdom, countries can be both high-average performers in PISA while demonstrating low individual and institutional variance in students’ achievement. Finally, Schleicher emphasized that investment in education is not the only determining factor for quality, since good and consistent implementation of educational policy is also very important.

The importance of cross-national cooperation

When reviewing the experience of SACMEQ, Mioko Saito, Head a.i of the IIEP Equity, Access and Quality Unit (technically supporting the SACMEQ implementation in collaboration with SACMEQ Coordinating Centre), explained how the notion of educational quality has significantly evolved in the southern and eastern African region and became a priority over the past decades. Since 1995, SACMEQ has, on a regular basis, initiated cross-national assessments on the quality of education, and each member country has benefited considerably from this cooperation. It helped them embracing new assessment areas (such as HIV and AIDS knowledge) and units of analysis (teachers, as well as pupils) to produce evidence on what pupils and teachers know and master, said Saito. She concluded by stressing that SACMEQ also has a major capacity development mission and is concerned with having research results bear on policy decisions.

The debate following the presentations focused on the crucial role of the media in stimulating public debate on the results of cross-national tests such as PISA and SACMEQ. It was also emphasized that more collaboration among the different cross-national mechanisms for the assessment of learner achievement would be beneficial. If more items were shared among the networks, more light could be shed on the international comparability of educational outcomes.

* PISA assesses the acquisition of key competencies for adult life of 15-year-olds in mathematics, reading, and science in OECD countries. SACMEQ focuses on achievements of Grade 6 pupils. Created in 1995, SACMEQ is a network of 15 southern and eastern African ministries of education: Botswana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania (Mainland), Tanzania (Zanzibar), Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe

- New website coming 29 August 2024

- Q&A: Educational planning brings people together 27 August 2024

- Gender at the Centre Initiative for education: A journey in graphics 01 August 2024

- PISA Website

- Andreas Schleicher's presentation pdf, 2.3 Mo

- Mioko Saito's presentation pdf, 1.6 Mo

- Privacy Notice

Quality Education

Young Peruvian boy practices reading while sitting at a desk. Photo: Elizabeth Adelman

What are levers for inclusive and quality education for refugees?

Over one half of children globally who are out of school live in conflict settings. Yet quality education is an essential component for securing a future for refugee children. REACH identifies ways to strengthen and build refugees’ “unknowable futures.” This work is relevant not only for refugees but for other young people globally who face similar, even if less extreme, uncertainties in the face of rapid globalization and technological change.

Are Refugee Children Learning? Early Grade Literacy in a Refugee Camp in Kenya

by Benjamin Piper, Sarah Dryden-Peterson, Vidur Chopra, Celia Reddick, and Arbogast Oyanga

Research article

Are Refugee Children Learning? Early Grade Literacy in a Refugee Camp in Kenya by Benjamin Piper, Sarah Dryden-Peterson, Vidur Chopra, Celia Reddick, and Arbogast Oyanga (2020) in The Journal on Education in Emergencies .

In the first literacy census in a refugee camp, the authors assessed all the schools providing lower primary education to refugee children in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. The outcomes for these students were concerningly low, even lower than for those of disadvantaged children in the host community, Turkana County. Literacy outcomes differed among the refugee children, depending on their country of origin, the language of instruction used at the school in Kenya, the languages spoken at home, and the children’s self-professed expectation of a return to their country of origin.

Refugee Education: Backward Design to Enable Futures

by Sarah Dryden-Peterson

policy engagement

Refugee Education: Backward Design to Enable Futures by Sarah Dryden-Peterson (2019) in Education and Conflict Review.

This short paper explores the use of backward design as a way to conceptualize refugee education policy and practice. Drawing on examples of classroom and research experiences, it proposes a planning template aimed at enabling refugee education policy and practice to facilitate the futures that refugee young people imagine and aim to create.

Tío Emilio’s Story: A Tale from Nicaragua

written by Hania Mariën

Tío Emilio’s Story written by Hania Mariën (2019). A curriculum for students ages 10-14 .

Tío Emilio’s Story is a narrative of one individual’s pursuit of education during a time of conflict in Nicaragua. It offers students an insight into life in Nicaragua from 1967-1990, as experienced by one child on Isla Ometepe and touches upon issues of poverty, armed violence, and leaving home, as well as that of resilience and persistence. At its core, however, it is about learning to be a child. Educators and students are encouraged to learn with and from Tío Emilio and critically engage with Nicaraguan history, the United States’ involvement in the country, and to think about how conflict and military regimes can impact education.

Additional Resources

Video | What would it take to ensure that all refugee young people have access to learning that enables them to feel a sense of belonging? Refugee REACH founder and director Sarah Dryden-Peterson joined Steve Paikin on TVO’s The Agenda to discuss her book “Right Where We Belong: How Refugee Teachers and Students Are Changing the Future of Education,” and to explore this question.

Video | Refugee REACH director Sarah Dryden-Peterson delivers a lecture titled Refugee Education: Power, Purposes, and Pedagogies Across Contexts, hosted by NYU’s Global TIES for Children.

Podcast | Celia Reddick and Sarah Dryden-Peterson discuss language of instruction in refugee education on the FreshEd podcast, hosted by Will Brehm.

Video | Refugee REACH director Sarah Dryden-Peterson and students Esther Elonga, Martha Franco, Orelia Jonathan, and Kristia Wantchekon discuss how experiences of uncertainty affect the research design process amid multiple pandemics of Covid-19 and racism.

Insight | Student leaders and educators in Refugee REACH director Sarah Dryden-Peterson's new module at HGSE, Education in Uncertainty, share how they were able to connect their studies to practice and respond to emerging needs of their local communities and build supports during Covid-19.

Interview | Mary Winters, an HGSE alumna and now Programme Specialist with the LEGO Foundation, shares what it’s been like to put her classroom learning into practice, how she uses research in her work, and what keeps her going.

Research | This article finds that peer-to-peer group chats expand transnational learning opportunities and possibilities for instructional innovations, community engagement, and conversations about gender equity in refugee education.

Research | This article examines the quality of education available to refugees in both urban and refugee camp settings in Kenya, with a particular focus on teacher pedagogy.

Report | This policy report explores the educational histories of young refugee children in first-asylum countries, and identifies elements of these that are relevant to post-resettlement education in the United States.

Children’s Book | This resource details the personal account of Abdul, an Afghani child whose schooling was interrupted by armed conflict, but who never gave up in his pursuit for education.

The Quality and Qualities Of Educational Research

- Share article

Experts concur that American educational research is deficient.

In the early 1960s, the role of the federal government in education began its steady, if unspectacular, rise in size and importance. In the early 1980s, the indifferent quality of American schools came to the fore in the report A Nation at Risk . Now, at the start of the 21st century, a new theme—the quality of educational research—pervades discussions of education in America. The National Research Council has issued a widely reported essay on “Scientific Principles for Educational Research"; the influential educator Ellen Condliffe Lagemann has published her long-awaited critique An Elusive Science: The Troubling History of Education Research ; and Congress has enacted legislation, the “No Child Left Behind” Act of 2001, calling explicitly for scientifically based education research. Though the details of their analyses differ, these experts concur that American educational research is deficient—indeed, some imply that it bears the same tenuous relation to “real research” as “military justice” does to “real justice.” And at least on the political front, a solution seems clear: Educational research ought to take its model from medical research— specifically, the vaunted National Institutes of Health model. On this analysis (not one recommended by the aforementioned educational authorities), the more rapidly that we can institute randomized trials—the so-called “gold standard” of research involving human subjects—the sooner we will be able to make genuine progress in our understanding of schooling and education.

Perhaps—but perhaps not. Minds are not the same as bodies; schools are not the same as home or workplace; children cannot legitimately be assigned to or shuttled from one “condition” to another the way that agricultural seeds are planted or transplanted in different soils. It is appropriate to step back, to determine whether educational research is needed at all, whether it should be distinguished in any way from other scholarly research, what questions it might address, what are the principal ways in which it has worked thus far, and how it might proceed more effectively in the future.

If I had average means but flexibility in where I lived, I would send my infant to day care in France; my preschooler to the toddler centers in Reggio Emilia, Italy; my elementary school child to class in Japan; my high schooler to gymnasium in Germany or Hungary; and my 18-year-old to college or university in the United States. Living (as I have for decades) in Cambridge, Mass., and being fortunate enough to be able to afford quality local education, I would send my young child to one of the better public schools or Shady Hill School, my adolescent to Buckingham Browne and Nichols Secondary School, and—depending on his or her inclination—my college-age offspring to Harvard or MIT.

What is striking is that none of these good schools is based in any rigorous sense on educational research of the sort being called for by pundits. Rather, they are based on practices that have evolved over long periods of time. Often, these practices are finely honed by groups of teachers who have worked together for many years—trying out mini-experiments, reflecting on the results, critiquing one another, co-teaching, visiting other schools to observe, and the like. In the past—indeed, in the present—much of the best school practice has been based on such seat-of-the-pants observations, reflections, and informal experimentation. Perhaps we need to be doing more of this, rather than less; perhaps, in fact, research dollars might be better spent on setting up teacher study groups or mini-sabbaticals, rather than on NIH-style field-initiated or targeted-grant competitions.

Still, there is a place for more formal kinds of research, carried out by individuals who have been so trained. Certain questions are best answered by systematic study, rather than by anecdotes or impressions. Controversial issues like the optimal class size, the effects of tracking, the best way to introduce reading, the best method for improving comprehension of written materials, the immediate and long-term effects of charter or voucher schools, the consequences of bilingual vs. immersion programs—these and other issues need a more formal research design.

Note, however, three characteristics of such research. First of all, it is expensive and time-consuming to carry out. Second, it is very difficult to reach consensus. As any reader of the educational literature knows all too well, one can find experts on both sides of any of the aforementioned issues, each armed with his or her supporting data.

Third, and most painfully, even when consensus obtains on an issue, there is no guarantee that policymakers will take heed. As a cognitive psychologist, I know that children must construct knowledge for themselves; they cannot simply be “given” understanding of any important issue. This insight—shared by thousands of cognitive researchers all over the world—does not prevent legislators from calling time and again for “direct instruction” or drill-and- kill regimens. We may properly conclude that the results of educational research make their way only fitfully into classrooms: They are but one of numerous competing inputs.

As a longtime observer of the scene, I have identified two distinctive cohorts, which, as it happens, relate to the two principal organizations involved in educational research. For the purpose of contrast, let me caricature them slightly.

Founded in 1965, the National Academy of Education, or NAE, is a loosely knit set of approximately 120 scholars elected because of the judged quality of their research. Traditionally, the prototype for the NAE has been the scholar in a standard academic discipline whose work has had influence in educational circles. In many cases, the scholars themselves have not been in schools of education and have not thought of themselves primarily as educators. For example, psychologists Eleanor Gibson and Bärbel Inhelder, economist Gary Becker, sociologist James S. Coleman, and historian Bernard Bailyn have all been members of the academy. This association operates on the assumption that the best work is discipline-based; it is not particularly relevant whether the scholars are deeply knowledgeable about conditions “in the trenches.”

The much larger and more democratic American Educational Research Association, or AERA, consists of thousands of researchers, most of whom were trained and teach in schools of education. These individuals differ widely from one another in whether they have a disciplinary base, whether they value the disciplines, whether, indeed, they see the disciplines as obstacles. What links these individuals is a deep concern with the condition of children and schools— particularly (among American members) the conditions of disadvantaged youngsters in American public schools. Research is often evaluated in part in terms of whether it contributes to improving these conditions. If I may continue this caricature for a few more clauses, I would say that the prototypical NAE member is a discipline-based scholar from arts and sciences who happens to have wandered into an educational issue but may well wander out again. The prototypical AERA member is a researcher born and bred in education schools; his or her allegiance is more to problems and persons than to a discipline.

Naturally, one’s own analysis of and solution to the “education research” issue depends mightily on which cohort one values more highly. Were I appointed the czar of education research, I would call for three tried-and-true steps and one new one:

Recognize that much of the most valuable work in improving education has taken place in schools and systems that engage in reflective practice.

1. (Following teachers from Japan, Reggio Emilia, and other sites of exemplary practice) Recognize that much of the most valuable work in improving education has taken place in schools and systems that engage in reflective practice. Take serious steps to encourage such work and, when possible, support it by timely regulations and infusion of funds.

2. (Following the National Academy of Education model) Require that every researcher who wants to work in education have at least one disciplinary base. Such a disciplinary base requires familiarity with the chief approaches in the discipline; knowledge of major contributions; capacity to critique such literature; potential for contributing to scholarship. The discipline does not need to be a scientific one: Important contributions to education are made by humanists, philosophers, historians, and various breeds of social scientist.

3. (Following the American Educational Research Association model) Require that every researcher who wants to work in education become knowledgeable about two issues: First of all, the researcher must have direct knowledge of the educational system; such know-how is best acquired by spending time teaching or observing in schools or other precollegiate educational institutions. Second of all, the researcher must have direct knowledge of the various audiences for educational research. Unless there is familiarity with the audiences that can make use of educational research (teachers, administrators, policymakers, the general public), the chances that even good research will exert any effect are effectively nil.

Identification of relevant educational research by the proper constituents is necessary but, alas, it might not be sufficient. Hence, a new step is needed. In this respect, I have been much impressed by an organization called CIMIT, the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technologies. Affiliated with universities, hospitals, and research centers in the Boston area, the explicit goal of CIMIT is to create technological breakthroughs for which physicians are eager and to expedite the speed with which these innovations are placed in the hands of physicians who can use them.

Decades ago, the founder of CIMIT learned that even medical innovations that were universally hailed often took years—if not decades—before they could actually be used with patients on a widespread basis. And so, in 1994, a group of medical-science leaders decided to work with top-flight scientists and engineers and to devote their principal energies towards shortening the lead time from invention to use.

The crucial step in educational research will not occur simply because we have quality research along the lines I have specified. It will not occur simply because educational practitioners and consumers recognize the relevance of such research to their workaday concerns. Rather, it will occur only when the fruits of such research are readily available to any teacher or administrator who wants to put them to use.

Howard Gardner is the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs professor of cognition and education at Harvard University’s graduate school of education, in Cambridge, Mass. He is a co-author of Good Work: When Excellence and Ethics Meet (Basic Books), which has just been issued in paperback.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ

- PMC10606047

Factors Contributing to School Effectiveness: A Systematic Literature Review

Associated data.

No new data were created. Results are based on existing articles on the topic.

This paper aims to provide a systematic review of the literature on school effectiveness, with a focus on identifying the main factors that contribute to successful educational outcomes. The research question that this paper aimed to address is “what are the main factors of school effectiveness?”. We were interested in several descriptors such as school, effectiveness/efficiency theories, effectiveness/efficiency research and factors. Studies (published within the 2016–2022 period) were retrieved through two databases: JSTOR and ERIC. This paper defines several categories identified by school effectiveness research. Within these categories, various factors that affect the students’ outcomes and the defined effectiveness in school are listed. As the results show, the issue of school effectiveness is multifaceted, as the effectiveness of schools is a complex concept that can be measured through various indicators such as academic achievement, student engagement and teacher satisfaction. The review of school effectiveness revealed that several factors contribute to effective schools, such as strong leadership, effective teaching practices, a positive school culture and parental involvement. Additionally, school resources, such as funding and facilities, can impact school effectiveness, particularly in under-resourced communities.

1. Introduction

The answer to the question “what makes school effective?” is the Holy Grail of educational research [ 1 ]. School effectiveness has been a research topic for several decades, with scholars and policymakers seeking to identify the key factors that contribute to successful educational outcomes. The concept of school effectiveness refers to the extent to which a school is able to achieve its goals and objectives in terms of student learning, development and well-being [ 2 ]. This article is not focused on the historical view of school effectiveness research (SER) or on phases in its development but rather on identifying factors that contribute to school effectiveness. School effectiveness research concerns educational research and explores differences within and between schools and malleable factors that improve school performance [ 3 ] and/or achievements and/or outcomes. Educational (school) effectiveness can be defined as the degree to which an educational system and its components and stakeholders achieve specific desired goals and effects [ 4 ]. Taking into consideration the different terminology used in researching school effectiveness and that we were not focusing on those possible differences when describing our results, let us first focus on possible differences to which effective schooling can contribute—as the specific desired goals and effects of schooling can be numerous and especially because different aspects of those goals can be inter-linked.

Schools have important “effects” on children and their development; so, “schools do make a difference”, as stated by Reynolds and Creemers in [ 5 ] (p. 10). SER studies seek to include factors such as “gender, socio-economic status, mobility and fluency in the majority language used at school” in assessing the impact of schools [ 5 ] (p. 11). In the past, educational assessment mainly relied on basic metrics like the number of students advancing to higher education, the grade repetition rates and special education enrollment. However, it became clear that these metrics were influenced by external factors beyond school and teacher characteristics and were thus abandoned. Instead, more comprehensive measures focusing on academic achievement in subjects like math and language were introduced. Progress in assessing effectiveness continued with the inclusion of control measures, such as students’ prior knowledge and family socio-economic status. Presently, standardized objective tests are the primary tool for measuring educational effectiveness in specific curricula [ 4 ].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in understanding the factors that contribute to school effectiveness, particularly in light of concerns about the quality of education and the need to improve educational outcomes. Research suggests that school effectiveness is a multifaceted concept that is influenced by a range of factors, including school leadership, teacher quality, curriculum and instruction, school culture and climate, parental involvement and student characteristics [ 2 , 6 , 7 ]. However, the relative importance of these factors may vary depending on the context in which they are examined. Therefore, it is important to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to identify the key factors of school effectiveness across different contexts.

This paper aims to provide a systematic review of the literature on school effectiveness, with a focus on identifying the main influencing factors. The review drew upon a range of empirical studies, meta-analyses and reviews to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge on this topic. In this research, the literature review was conducted according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [ 8 ]. Systematic reviews of the literature have an important role and can identify different problems that can be addressed in future studies, “they can generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur’’ and can address questions that cannot be tackled by individual studies through several studies [ 8 ] (p. 1). We were interested in several descriptors such as school, effectiveness/efficiency theories, effectiveness/efficiency research, and factors. Studies were reviewed using two databases: JSTOR and ERIC. This paper defines several categories that are important in school effectiveness research and, within these categories, lists various factors that affect students’ outcomes and the defined school effectiveness. The research question that this paper aimed to address is “what are the main factors of school effectiveness?”. This paper can be helpful as it provides an overview of school effectiveness research, and the research question is of significant importance, as answering it can help inform educational policy and practice by identifying the key areas that schools should focus on in order to improve student outcomes. Several studies attempted to answer this question, but there is still much debate and discussion surrounding the factors that contribute to school effectiveness.

2. Background of School Effectiveness Research

The concept of school effectiveness emerged in the 1960s and 1970s in response to growing concerns about the quality of education and the need to improve educational outcomes for students [ 4 , 7 , 9 ]. Early definitions of school effectiveness focused on the achievement of educational outcomes, such as academic performance and the ability of schools to meet the needs of students from diverse backgrounds [ 4 , 10 ].

Coleman et al. [ 11 ] argued that students’ socioeconomic status is a crucial factor affecting their academic achievement in schools and has a greater impact than school characteristics. This is consistent with the conclusion reached by Jencks [ 12 ], who found that schools do not have a statistically significant impact on student achievement. These findings paved the way for school effectiveness research, which emerged in the early 1970s as a radical movement aimed at exploring the factors within schools that contribute to better students’ educational performance, regardless of their social background [ 13 ]. In the field of education, effective-schools research emerged as a response to previous studies such as Coleman’s and Jencks’, which indicated that schools had little impact on students’ achievement. As titles such as “Schools can make a difference” and “School matters” suggest, the goal of effective-schools research was to challenge this notion and explore factors that contribute to successful schools. What sets effective-schools research apart is its focus on investigating the internal workings of schools, including their organization, structure and content, in order to identify characteristics associated with effectiveness [ 14 , 15 ]. According to Muijs [ 14 ], school effectiveness research sought to move beyond the prevailing pessimism about the impact of schools and education on students’ educational performance. The movement aimed to focus on studying the factors within schools that could lead to better students’ academic performance, irrespective of their social background [ 14 ] (p. 141). Scheerens et al. [ 16 ] (p. 43) summed up the five influencing factors identified in early research on school effectiveness: “strong educational leadership, emphasis on the acquiring of basic skills, an orderly and secure environment, high expectations of pupil attainment, frequent assessment of pupil progress”.

According to various scholars [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ], defining educational quality is a challenging task due to the diverse settings, stakeholders and goals involved in education. Generally, educational quality can be defined as achieving the desired standards and goals. Creemers and Scheerens [ 23 ] further added that quality refers to the characteristics and factors of the school that contribute to differences in outcomes between students in different grades, schools and educational systems. However, these definitions fail to provide a clear explanation of the specific characteristics that result in quality education and schools [ 4 ] (p. 2). School effectiveness is a subset of educational effectiveness or educational quality. According to Scheerens [ 21 ], educational effectiveness refers to the extent to which an educational program or institution achieves its intended outcomes, while school effectiveness is concerned with the extent to which a school achieves its goals and objectives. Burusic et al. [ 4 ] also noted that school effectiveness research is a branch of educational effectiveness research that specifically focuses on the functioning of schools and their impact on student outcomes.

Theories of school effectiveness have evolved over time, with a greater emphasis on the role of leadership and school culture in shaping educational outcomes. One of the most influential models of school effectiveness is the “Effective Schools Model” developed by Edmonds [ 24 ]. This model identified five key characteristics of effective schools: high expectations, strong instructional leadership, a safe and orderly environment, a focus on basic skills, and frequent monitoring of student progress.

Subsequent research confirmed the importance of these factors in promoting school effectiveness [ 2 , 25 ]. For example, a study by Leithwood et al. [ 2 ] found that effective school leadership was associated with improved student outcomes, including academic achievement and graduation rates. Similarly, research by Ismail et al. [ 26 ] highlighted the importance of a positive school culture, including supportive relationships among staff and students, in promoting school effectiveness.

Reynolds et al. [ 27 ] (p. 3) proposed that there are three primary areas of focus in School Effectiveness Research (SER):

- School Effects Research: investigating the scientific characteristics of school effects, which has evolved from input–output studies to current studies that use multilevel models.

- Effective Schools Research: researching the procedures and mechanisms of effective schooling, which has developed from case studies of exceptional schools to contemporary studies that integrate qualitative and quantitative methods to study classrooms and schools concurrently.

- School Improvement Research: examining the methods through which schools can be transformed, utilizing increasingly advanced models that surpass the simple implementation of school effectiveness knowledge to employ sophisticated “multiple-lever” models.

Sammons and Bakkum [ 5 ] (p. 10) argued the importance of different factors that are associated with student attainment: “individual characteristics (age, birth weight, gender), family socio-economic characteristics (particularly family structure, parental background: qualification levels, health, socio-economic status, in or out of work, and income level), community and societal characteristics (neighborhood context, cultural expectations, social structural divisions especially in relation to social class)”.