Introduction to qualitative nursing research

This type of research can reveal important information that quantitative research can’t.

- Qualitative research is valuable because it approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, about which little is known by trying to understand its many facets.

- Most qualitative research is emergent, holistic, detailed, and uses many strategies to collect data.

- Qualitative research generates evidence and helps nurses determine patient preferences.

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

How to appraise quantitative research articles

All nurses are expected to understand and apply evidence to their professional practice. Some of the evidence should be in the form of research, which fills gaps in knowledge, developing and expanding on current understanding. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods inform nursing practice, but quantitative research tends to be more emphasized. In addition, many nurses don’t feel comfortable conducting or evaluating qualitative research. But once you understand qualitative research, you can more easily apply it to your nursing practice.

What is qualitative research?

Defining qualitative research can be challenging. In fact, some authors suggest that providing a simple definition is contrary to the method’s philosophy. Qualitative research approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, from a place of unknowing and attempts to understand its many facets. This makes qualitative research particularly useful when little is known about a phenomenon because the research helps identify key concepts and constructs. Qualitative research sets the foundation for future quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research also can stand alone without quantitative research.

Although qualitative research is diverse, certain characteristics—holism, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and situated contexts—guide its methodology. This type of research stresses the importance of studying each individual as a holistic system (holism) influenced by surroundings (situated contexts); each person develops his or her own subjective world (subjectivity) that’s influenced by interactions with others (intersubjectivity) and surroundings (situated contexts). Think of it this way: Each person experiences and interprets the world differently based on many factors, including his or her history and interactions. The truth is a composite of realities.

Qualitative research designs

Because qualitative research explores diverse topics and examines phenomena where little is known, designs and methodologies vary. Despite this variation, most qualitative research designs are emergent and holistic. In addition, they require merging data collection strategies and an intensely involved researcher. (See Research design characteristics .)

Although qualitative research designs are emergent, advanced planning and careful consideration should include identifying a phenomenon of interest, selecting a research design, indicating broad data collection strategies and opportunities to enhance study quality, and considering and/or setting aside (bracketing) personal biases, views, and assumptions.

Many qualitative research designs are used in nursing. Most originated in other disciplines, while some claim no link to a particular disciplinary tradition. Designs that aren’t linked to a discipline, such as descriptive designs, may borrow techniques from other methodologies; some authors don’t consider them to be rigorous (high-quality and trustworthy). (See Common qualitative research designs .)

Sampling approaches

Sampling approaches depend on the qualitative research design selected. However, in general, qualitative samples are small, nonrandom, emergently selected, and intensely studied. Qualitative research sampling is concerned with accurately representing and discovering meaning in experience, rather than generalizability. For this reason, researchers tend to look for participants or informants who are considered “information rich” because they maximize understanding by representing varying demographics and/or ranges of experiences. As a study progresses, researchers look for participants who confirm, challenge, modify, or enrich understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Many authors argue that the concepts and constructs discovered in qualitative research transcend a particular study, however, and find applicability to others. For example, consider a qualitative study about the lived experience of minority nursing faculty and the incivility they endure. The concepts learned in this study may transcend nursing or minority faculty members and also apply to other populations, such as foreign-born students, nurses, or faculty.

Qualitative nursing research can take many forms. The design you choose will depend on the question you’re trying to answer.

| Action research | Education | Conducted by and for those taking action to improve or refine actions | What happens to the quality of nursing practice when we implement a peer-mentoring system? |

| Case study | Many | In-depth analysis of an entity or group of entities (case) | How is patient autonomy promoted by a unit? |

| Descriptive | N/A | Content analysis of data | |

| Discourse analysis | Many | In-depth analysis of written, vocal, or sign language | What discourses are used in nursing practice and how do they shape practice? |

| Ethnography | Anthropology | In-depth analysis of a culture | How does Filipino culture influence childbirth experiences? |

| Ethology | Psychology | Biology of human behavior and events | What are the immediate underlying psychological and environmental causes of incivility in nursing? |

| Grounded theory | Sociology | Social processes within a social setting | How does the basic social process of role transition happen within the context of advanced practice nursing transitions? |

| Historical research | History | Past behaviors, events, conditions | When did nurses become researchers? |

| Narrative inquiry | Many | Story as the object of inquiry | How does one live with a diagnosis of scleroderma? |

| Phenomenology | Philosophy Psychology | Lived experiences | What is the lived experience of nurses who were admitted as patients on their home practice unit? |

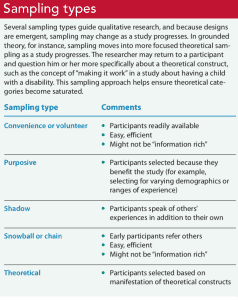

A sample size is estimated before a qualitative study begins, but the final sample size depends on the study scope, data quality, sensitivity of the research topic or phenomenon of interest, and researchers’ skills. For example, a study with a narrow scope, skilled researchers, and a nonsensitive topic likely will require a smaller sample. Data saturation frequently is a key consideration in final sample size. When no new insights or information are obtained, data saturation is attained and sampling stops, although researchers may analyze one or two more cases to be certain. (See Sampling types .)

Some controversy exists around the concept of saturation in qualitative nursing research. Thorne argues that saturation is a concept appropriate for grounded theory studies and not other study types. She suggests that “information power” is perhaps more appropriate terminology for qualitative nursing research sampling and sample size.

Data collection and analysis

Researchers are guided by their study design when choosing data collection and analysis methods. Common types of data collection include interviews (unstructured, semistructured, focus groups); observations of people, environments, or contexts; documents; records; artifacts; photographs; or journals. When collecting data, researchers must be mindful of gaining participant trust while also guarding against too much emotional involvement, ensuring comprehensive data collection and analysis, conducting appropriate data management, and engaging in reflexivity.

Data usually are recorded in detailed notes, memos, and audio or visual recordings, which frequently are transcribed verbatim and analyzed manually or using software programs, such as ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH, MAXQDA, or NVivo. Analyzing qualitative data is complex work. Researchers act as reductionists, distilling enormous amounts of data into concise yet rich and valuable knowledge. They code or identify themes, translating abstract ideas into meaningful information. The good news is that qualitative research typically is easy to understand because it’s reported in stories told in everyday language.

Evaluating a qualitative study

Evaluating qualitative research studies can be challenging. Many terms—rigor, validity, integrity, and trustworthiness—can describe study quality, but in the end you want to know whether the study’s findings accurately and comprehensively represent the phenomenon of interest. Many researchers identify a quality framework when discussing quality-enhancement strategies. Example frameworks include:

- Trustworthiness criteria framework, which enhances credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity

- Validity in qualitative research framework, which enhances credibility, authenticity, criticality, integrity, explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity.

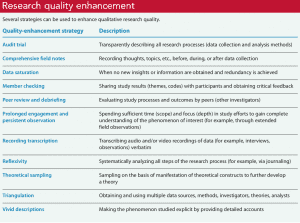

With all frameworks, many strategies can be used to help meet identified criteria and enhance quality. (See Research quality enhancement ). And considering the study as a whole is important to evaluating its quality and rigor. For example, when looking for evidence of rigor, look for a clear and concise report title that describes the research topic and design and an abstract that summarizes key points (background, purpose, methods, results, conclusions).

Application to nursing practice

Qualitative research not only generates evidence but also can help nurses determine patient preferences. Without qualitative research, we can’t truly understand others, including their interpretations, meanings, needs, and wants. Qualitative research isn’t generalizable in the traditional sense, but it helps nurses open their minds to others’ experiences. For example, nurses can protect patient autonomy by understanding them and not reducing them to universal protocols or plans. As Munhall states, “Each person we encounter help[s] us discover what is best for [him or her]. The other person, not us, is truly the expert knower of [him- or herself].” Qualitative nursing research helps us understand the complexity and many facets of a problem and gives us insights as we encourage others’ voices and searches for meaning.

When paired with clinical judgment and other evidence, qualitative research helps us implement evidence-based practice successfully. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of disaster workers might help expose strengths and weaknesses of individuals, populations, and systems, providing areas of focused intervention. Or a phenomenological study of the lived experience of critical-care patients might expose factors (such dark rooms or no visible clocks) that contribute to delirium.

Successful implementation

Qualitative nursing research guides understanding in practice and sets the foundation for future quantitative and qualitative research. Knowing how to conduct and evaluate qualitative research can help nurses implement evidence-based practice successfully.

When evaluating a qualitative study, you should consider it as a whole. The following questions to consider when examining study quality and evidence of rigor are adapted from the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

| o What is the report title and composition of the abstract? o What is the problem and/or phenomenon of interest and study significance? o What is the purpose of the study and/or research question? | → Clear and concise report title describes the research topic and design (e.g., grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g., interviews) → Abstract summarizes key points including background, purpose, methods, results, and conclusions → Problem and/or phenomenon of interest and significance is identified and well described, with a thorough review of relevant theories and/or other research → Study purpose and/or research question is identified and appropriate to the problem and/or phenomenon of interest and significance |

| o What design and/or research paradigm was used? o Is there evidence of researcher reflexivity? o What is the setting and context for the study? o What is the sampling approach? How and why were data selected? Why was sampling stopped? o Was institutional review board (IRB) approval obtained and were other issues relating to protection of human subjects outlined? | → Design (e.g., phenomenology, ethnography), research paradigm (e.g., constructivist), and guiding theory or model, as appropriate, are identified, along with well-described rationales → Design is appropriate to research problem and/or phenomenon of interest → Researcher characteristics that may influence the study are identified and well described, as well as methods to protect against these influences (e.g., journaling, bracketing) → Settings, sites, and contexts are identified and well described, along with well-described rationales |

| o What data collection and analysis instruments and/or technologies were used? o What is the method for data processing and analysis? o What is the composition of the data? o What strategies were used to enhance quality and trustworthiness? | → Sampling approach and how and why data were selected are identified and well described, along with well-described rationales; participant inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined and appropriate → Criteria for deciding when sampling stops is outlined (e.g., saturation) and rationale is provided and appropriate → Documentation of IRB approval or explanation of lack thereof provided; consent, confidentiality, data security, and other protection of human subject issues are well described and thorough → Description of instruments (e.g., interview scripts, observation logs) and technologies (e.g., audio-recorders) used is provided, including how instruments were developed; description of if and how these changed during the study is given, along with well-described rationales → Types of data collected, details of data collection, analysis, and other processing procedures are well described and thorough, along with well-described rationales → Number and characteristics of participants and/or other data are described and appropriate → Strategies to enhance quality and trustworthiness (e.g., member checking) are identified, comprehensive, and appropriate, along with well-described rationales; trustworthiness framework, if identified, is established from experts (e.g., Lincoln and Guba, Whittemore et al.) and strategies are appropriate to this framework |

| o Were main study results synthesized and interpreted? If applicable, were they developed into a theory or integrated with prior research? o Were results linked to empirical data? | → Main results (e.g., themes) are presented and well described and a theory or model is developed and described, if applicable; results are integrated with prior research → Adequate evidence (e.g., direct quotes from interviews, field notes) is provided to support main study results |

| o Are study results described in relation to prior work? o Are study implications, applicability, and contributions to nursing identified? o Are study limitations outlined? | → Concise summary of main results are provided and thorough, including relation to prior works (e.g., connection, support, elaboration, challenging prior conclusions) → Thorough discussion of study implications, applicability, and unique contributions to nursing is provided → Study limitations are described thoroughly and future improvements and/or research topics are suggested |

| o Are potential or perceived conflicts of interest identified and how were these managed? o If applicable, what sources of funding or other support did the study receive? | → All potential or perceived conflicts of interest are identified and well described; methods to manage potential or perceived conflicts of interest are identified and appear to protect study integrity → All sources of funding and other support are identified and well described, along with the roles the funders and support played in study efforts; they do not appear to interfere with study integrity |

Jennifer Chicca is a PhD candidate at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a part-time faculty member at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(3):121-7.

Cuthbert CA, Moules N. The application of qualitative research findings to oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum . 2014;41(6):683-5.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1994: 105-17.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1985.

Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective . 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 1: Philosophies. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(1):26-33.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 2: Methodology. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(2):71-7.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(3):114-21.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med . 2014;89(9):1245-51.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Thorne S. Saturation in qualitative nursing studies: Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Auth Ed. 2020;30(1):5. naepub.com/reporting-research/2020-30-1-5

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res . 2001;11(4):522-37.

Williams B. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse Today . 2015;10(7):40-2.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

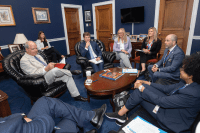

Nurses build coalitions at the Capitol

Stop fall prevention practices that aren’t working

Self-compassion in practice

Mitigating patient identification threats

Reflections: My first year as a Magnet® Program Director

Collective wisdom

The role of hospital-based nurse scientists

Professionalism and professional identity

Emotional intelligence: A neglected nursing competency

Hypnosis and pain

Measuring nurses’ health

From Retirement to Preferment: Crafting Your Next Chapter

Leadership in changing times

Promoting health literacy

Mentorship: A strategy for nursing retention

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 3

- Data collection in qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- David Barrett 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1130-5603 Alison Twycross 2

- 1 Faculty of Health Sciences , University of Hull , Hull , UK

- 2 School of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr David Barrett, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, UK; D.I.Barrett{at}hull.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102939

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Qualitative research methods allow us to better understand the experiences of patients and carers; they allow us to explore how decisions are made and provide us with a detailed insight into how interventions may alter care. To develop such insights, qualitative research requires data which are holistic, rich and nuanced, allowing themes and findings to emerge through careful analysis. This article provides an overview of the core approaches to data collection in qualitative research, exploring their strengths, weaknesses and challenges.

Collecting data through interviews with participants is a characteristic of many qualitative studies. Interviews give the most direct and straightforward approach to gathering detailed and rich data regarding a particular phenomenon. The type of interview used to collect data can be tailored to the research question, the characteristics of participants and the preferred approach of the researcher. Interviews are most often carried out face-to-face, though the use of telephone interviews to overcome geographical barriers to participant recruitment is becoming more prevalent. 1

A common approach in qualitative research is the semistructured interview, where core elements of the phenomenon being studied are explicitly asked about by the interviewer. A well-designed semistructured interview should ensure data are captured in key areas while still allowing flexibility for participants to bring their own personality and perspective to the discussion. Finally, interviews can be much more rigidly structured to provide greater control for the researcher, essentially becoming questionnaires where responses are verbal rather than written.

Deciding where to place an interview design on this ‘structural spectrum’ will depend on the question to be answered and the skills of the researcher. A very structured approach is easy to administer and analyse but may not allow the participant to express themselves fully. At the other end of the spectrum, an open approach allows for freedom and flexibility, but requires the researcher to walk an investigative tightrope that maintains the focus of an interview without forcing participants into particular areas of discussion.

Example of an interview schedule 3

What do you think is the most effective way of assessing a child’s pain?

Have you come across any issues that make it difficult to assess a child’s pain?

What pain-relieving interventions do you find most useful and why?

When managing pain in children what is your overall aim?

Whose responsibility is pain management?

What involvement do you think parents should have in their child’s pain management?

What involvement do children have in their pain management?

Is there anything that currently stops you managing pain as well as you would like?

What would help you manage pain better?

Interviews present several challenges to researchers. Most interviews are recorded and will need transcribing before analysing. This can be extremely time-consuming, with 1 hour of interview requiring 5–6 hours to transcribe. 4 The analysis itself is also time-consuming, requiring transcriptions to be pored over word-for-word and line-by-line. Interviews also present the problem of bias the researcher needs to take care to avoid leading questions or providing non-verbal signals that might influence the responses of participants.

Focus groups

The focus group is a method of data collection in which a moderator/facilitator (usually a coresearcher) speaks with a group of 6–12 participants about issues related to the research question. As an approach, the focus group offers qualitative researchers an efficient method of gathering the views of many participants at one time. Also, the fact that many people are discussing the same issue together can result in an enhanced level of debate, with the moderator often able to step back and let the focus group enter into a free-flowing discussion. 5 This provides an opportunity to gather rich data from a specific population about a particular area of interest, such as barriers perceived by student nurses when trying to communicate with patients with cancer. 6

From a participant perspective, the focus group may provide a more relaxing environment than a one-to-one interview; they will not need to be involved with every part of the discussion and may feel more comfortable expressing views when they are shared by others in the group. Focus groups also allow participants to ‘bounce’ ideas off each other which sometimes results in different perspectives emerging from the discussion. However, focus groups are not without their difficulties. As with interviews, focus groups provide a vast amount of data to be transcribed and analysed, with discussions often lasting 1–2 hours. Moderators also need to be highly skilled to ensure that the discussion can flow while remaining focused and that all participants are encouraged to speak, while ensuring that no individuals dominate the discussion. 7

Observation

Participant and non-participant observation are powerful tools for collecting qualitative data, as they give nurse researchers an opportunity to capture a wide array of information—such as verbal and non-verbal communication, actions (eg, techniques of providing care) and environmental factors—within a care setting. Another advantage of observation is that the researcher gains a first-hand picture of what actually happens in clinical practice. 8 If the researcher is adopting a qualitative approach to observation they will normally record field notes . Field notes can take many forms, such as a chronological log of what is happening in the setting, a description of what has been observed, a record of conversations with participants or an expanded account of impressions from the fieldwork. 9 10

As with other qualitative data collection techniques, observation provides an enormous amount of data to be captured and analysed—one approach to helping with collection and analysis is to digitally record observations to allow for repeated viewing. 11 Observation also provides the researcher with some unique methodological and ethical challenges. Methodologically, the act of being observed may change the behaviour of the participant (often referred to as the ‘Hawthorne effect’), impacting on the value of findings. However, most researchers report a process of habitation taking place where, after a relatively short period of time, those being observed revert to their normal behaviour. Ethically, the researcher will need to consider when and how they should intervene if they view poor practice that could put patients at risk.

The three core approaches to data collection in qualitative research—interviews, focus groups and observation—provide researchers with rich and deep insights. All methods require skill on the part of the researcher, and all produce a large amount of raw data. However, with careful and systematic analysis 12 the data yielded with these methods will allow researchers to develop a detailed understanding of patient experiences and the work of nurses.

- Twycross AM ,

- Williams AM ,

- Huang MC , et al

- Onwuegbuzie AJ ,

- Dickinson WB ,

- Leech NL , et al

- Twycross A ,

- Emerson RM ,

- Meriläinen M ,

- Ala-Kokko T

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons Ireland - Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Al Sayh Muharraq Governorate, Bahrain.

- 2 Department of Mental Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

- 3 Department of OBG Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

- 4 School of Nursing, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, USA.

- 5 Department of Child Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

- PMID: 34084317

- PMCID: PMC8106287

- DOI: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_321_19

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate robust evidence about important issues in the fields of medicine and healthcare. Qualitative research has ample possibilities within the arena of healthcare research. This article aims to inform healthcare professionals regarding qualitative research, its significance, and applicability in the field of healthcare. A wide variety of phenomena that cannot be explained using the quantitative approach can be explored and conveyed using a qualitative method. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research. The greatest strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness and depth of the healthcare exploration and description it makes. In health research, these methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Keywords: Ethnography; grounded theory; qualitative research; research design.

Copyright: © 2021 International Journal of Preventive Medicine.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Similar articles

- A qualitative systematic review of internal and external influences on shared decision-making in all health care settings. Truglio-Londrigan M, Slyer JT, Singleton JK, Worral P. Truglio-Londrigan M, et al. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(58):4633-4646. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2012-432. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012. PMID: 27820528

- The experience of adults who choose watchful waiting or active surveillance as an approach to medical treatment: a qualitative systematic review. Rittenmeyer L, Huffman D, Alagna M, Moore E. Rittenmeyer L, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016 Feb;14(2):174-255. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2270. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016. PMID: 27536798 Review.

- Experiences and perceptions of spousal/partner caregivers providing care for community-dwelling adults with dementia: a qualitative systematic review. Macdonald M, Martin-Misener R, Weeks L, Helwig M, Moody E, MacLean H. Macdonald M, et al. JBI Evid Synth. 2020 Apr;18(4):647-703. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003774. JBI Evid Synth. 2020. PMID: 32813338

- Health professionals' experience of teamwork education in acute hospital settings: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Eddy K, Jordan Z, Stephenson M. Eddy K, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016 Apr;14(4):96-137. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-1843. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016. PMID: 27532314 Review.

- Patient experiences of partnering with healthcare professionals for hand hygiene compliance: a systematic review. Butenko S, Lockwood C, McArthur A. Butenko S, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017 Jun;15(6):1645-1670. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003001. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017. PMID: 28628522 Review.

- Comprehensive Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (CCQR): Reporting Guideline for Global Health Qualitative Research Methods. Sinha P, Paudel B, Mosimann T, Ahmed H, Kovane GP, Moagi M, Phuti A. Sinha P, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Jul 30;21(8):1005. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21081005. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024. PMID: 39200615 Free PMC article. Review.

- Advantages, barriers, and cues to advance care planning engagement in elderly patients with cancer and family members in Southern Thailand: a qualitative study. Sripaew S, Assanangkornchai S, Limsomwong P, Kittichet R, Vichitkunakorn P. Sripaew S, et al. BMC Palliat Care. 2024 Aug 21;23(1):211. doi: 10.1186/s12904-024-01536-x. BMC Palliat Care. 2024. PMID: 39164698 Free PMC article.

- Health Workers' Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Resilience During COVID-19 Pandemic. Ma HY, Chiang NT, Kao RH, Lee CY. Ma HY, et al. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024 Aug 2;17:3691-3713. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S464285. eCollection 2024. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024. PMID: 39114858 Free PMC article.

- A Mixed-Method Study of the Utilization and Determinants of Private Health Insurance Schemes in the Residents of Rural Communities in Central India: A Study Protocol. Jambholkar PC, Choudhari SG, Dhonde A. Jambholkar PC, et al. Cureus. 2024 Jul 2;16(7):e63648. doi: 10.7759/cureus.63648. eCollection 2024 Jul. Cureus. 2024. PMID: 39092375 Free PMC article.

- Developing a module on the care of LGBTQIA+ individuals for health professionals: Research protocol. Pai MS, Yesodharan R, Palimar V, Thimmappa L, Bhat BB, Krishnan M N, Shetty D, Babu BV. Pai MS, et al. F1000Res. 2024 Jul 23;12:1437. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.140518.1. eCollection 2023. F1000Res. 2024. PMID: 39070118 Free PMC article.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice.

- Sorrell JM. Qualitative research in clinical nurse specialist practice. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27:175–8. - PubMed

- Draper AK. The principles and application of qualitative research. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:641–6. - PubMed

- Alasuutari P. The rise and relevance of qualitative research. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2010;13:139–55.

- Morse JM. Qualitative health research: One quarter of a century. Qual Health Res. 2014;25:3–4. - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- PubMed Central

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

Nursing Resources : Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Differences between Qualitative & Quantitative Research

" Quantitative research ," also called " empirical research ," refers to any research based on something that can be accurately and precisely measured. For example, it is possible to discover exactly how many times per second a hummingbird's wings beat and measure the corresponding effects on its physiology (heart rate, temperature, etc.).

" Qualitative research " refers to any research based on something that is impossible to accurately and precisely measure. For example, although you certainly can conduct a survey on job satisfaction and afterwards say that such-and-such percent of your respondents were very satisfied with their jobs, it is not possible to come up with an accurate, standard numerical scale to measure the level of job satisfaction precisely.

It is so easy to confuse the words "quantitative" and "qualitative," it's best to use "empirical" and "qualitative" instead.

Hint: An excellent clue that a scholarly journal article contains empirical research is the presence of some sort of statistical analysis

See "Examples of Qualitative and Quantitative" page under "Nursing Research" for more information.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Considered hard science |

| Considered soft science |

| Objective |

| Subjective |

| Deductive reasoning used to synthesize data |

| Inductive reasoning used to synthesize data |

| Focus—concise and narrow |

| Focus—complex and broad |

| Tests theory |

| Develops theory |

| Basis of knowing—cause and effect relationships |

| Basis of knowing—meaning, discovery |

| Basic element of analysis—numbers and statistical analysis |

| Basic element of analysis—words, narrative |

| Single reality that can be measured and generalized |

| Multiple realities that are continually changing with individual interpretation |

- John M. Pfau Library

Examples of Qualitative vs Quantitiative

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| What is the impact of a learner-centered hand washing program on a group of 2 graders? | Paper and pencil test resulting in hand washing scores | Yes | Quantitative |

| What is the effect of crossing legs on blood pressure measurement? | Blood pressure measurements before and after crossing legs resulting in numbers | Yes | Quantitative |

| What are the experiences of fathers concerning support for their wives/partners during labor? | Unstructured interviews with fathers (5 supportive, 5 non-supportive): results left in narrative form describing themes based on nursing for the whole person theory | No | Qualitative |

| What is the experience of hope in women with advances ovarian cancer? | Semi-structures interviews with women with advances ovarian cancer (N-20). Identified codes and categories with narrative examples | No | Qualitative |

- << Previous: Table of Evidence

- Next: Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

Nursing - Quantitative & Qualitative Articles: Qualitative

- Search Actively

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- Mixed Methods

- Definitions

- Write & Cite

- Give Feedback

"How does numerical value teach us about a population's problems?" .cls-1{fill:#fff;stroke:#79a13f;stroke-miterlimit:10;stroke-width:5px;}.cls-2{fill:#79a13f;} Numeric data collected from studies can indicate why a health problem exists, such as correlating data between environmental or genetic factors to a condition. This data can help us find appropriate interventions based on a specific cause.

- What is Qualitative?

Search for Qualitative

Identify articles, check quality, what is qualitative research.

- Qualitative Research from the SAGE Encyclopedia of Theory in Psychology by Carla Willig Qualitative research is an approach to research that is primarily concerned with studying the nature, quality, and meaning of human experience. It asks questions about how people make sense of their experiences, how people talk about what has happened to them and others, and how people experience, manage, and negotiate situations they find themselves in. Qualitative research is interested both in individual experiences and in the ways in which people experience themselves as part of a group. Qualitative data take the form of accounts or observations, and the findings are presented in the form of a discussion of the themes that emerged from the analysis. Numbers are very rarely used in qualitative research.

- Entanglement and the Relevance of Method in Qualitative Research by Pamela G. Reed "This brief article is an introduction to the feature article on self-reflection in interpretive phenomenology research. Self-reflection is discussed as a method that warrants more explicit description in the practice of qualitative research. Research does not occur in an epistemic vacuum. Despite researchers’ entanglement in the process of research and the fuzziness of the phenomenon under study, scientific methods, including that of self-reflection, enable nurse scientists to persevere in their study of human health experiences" (Reed, 2018, Abstract).

- Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) by Trisha Greenhalgh "Qualitative researchers seek a deeper truth. They aim to study things in their natural setting, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them'[2], and they use a holistic perspective which preserves the complexities of human behaviour" [2]. (Greenhalgh, 2020, Chapter 12).

- Qualitative evidence by Jane Noyes et al. from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions "A synthesis of qualitative evidence can inform understanding of how interventions work by: increasing understanding of a phenomenon of interest (e.g. women’s conceptualization of what good antenatal care looks like); identifying associations between the broader environment within which people live and the interventions that are implemented; increasing understanding of the values and attitudes toward, and experiences of, health conditions and interventions by those who implement or receive them; and providing a detailed understanding of the complexity of interventions and implementation, and their impacts and effects on different subgroups of people and the influence of individual and contextual characteristics within different contexts" (Noyes et al, 2019, Introduction).

- The value of qualitative research by Liam Clarke "This article describes the dual nature of nursing research. It describes how qualitative research can present the patient's experience in a way that quantitative research cannot, but warns against over-reliance on qualitative methods. The article critically summarises the ideas of the European philosophers on which qualitative research is based" (Clarke, 2004).

- Engaging nursing students in qualitative research through hands-on participation by Hall et al. The article focuses on undergraduate nursing students often view research as challenging and difficult to understand. Topics include student learning the processes of qualitative and quantitative research has compared with learning new clinical skills, active learning uses creative strategies to improve critical thinking, and learning the qualitative research process and has sparked an interest in using the methods for future areas of interest.

Clarke, L. (2004). The value of qualitative research. Nursing Standard , 18 (52), 41+. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.simmons.edu/apps/doc/A122410070/ITOF?u=mlin_b_simmcol&sid=ITOF&xid=acb3d5a5

Greenhalgh, T. (2019). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). In How to read a Paper : The basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare . (Sixth ed., pp. 165-178). Wiley Blackwell.

Hall, K. C., Andries, C., & McNair, M. E. (2020). Engaging nursing students in qualitative research through hands-on participation. Journal of Nursing Education , 59 (3), 177. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.3928/01484834-20200220-13

Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Harden A, Harris J, Garside R, Hannes K, Pantoja T, Thomas J. Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/

Reed, P. G. (2018). Entanglement and the relevance of method in qualitative research. Nursing Science Quarterly , 31 (3), 243–244. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.1177/0894318418774927

Willig, C. (2016). Qualitative research. In L. H. Miller (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of theory in psychology . Sage Publications, Credo Reference.

Here are some search examples you can use. Let us know if we can add a type of search link for you.

- "Fibromyalgia" AND Quantitative Keyword and method searched as subjects; from 2015-2020

- "Palliative Care" AND "Qualitative Studies" From 2015-2020

- "Nurs* Perception" AND "Qualitative Studies" From 2015-2018; Peer-Reviewed; Any Author is Nurse; in Nursing Journals

- "Anxiety" AND Qualitative Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and method searched as subject; from 2015-2019; in Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals

- "Operating Room" AND Qualitative Method searched in titles; from 2015-2020; Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals;

- "Transgender Patient*" AND Quantitative From 2015-2019; Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals

- Blindness AND Qualitative From 2015-2020; Nursing journals

- Dementia AND Qualitative From 2015-2020; Nursing journals

- Hypertension AND Qualitative From 2015-2020; Nursing journals

Qualitative and Quantitative Studies

To find qualitative and quantitative studies, try adding one of these words/phrases to your search terms. The word "qualitative" or "quantitative" will sometimes appear in the title, abstract, or subject terms, but not always. Look at the methods section of the article to determine what type of study design was used.

| - | Qualitative | Quantitative |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Research that seeks to provide understanding of human experience, perceptions, motivations, intentions, and behaviors based on description and observation and utilizing a naturalistic interpretative approach to a subject and its contextual setting. | Research based on traditional scientific methods, which generates numerical data and usually seeks to establish causal relationships between two or more variables, using statistical methods to test the strength and significance of the relationships. |

| What's Involved | Observations described in words | Observations measured in numbers |

| Starting Point | A situation the researcher can observe | A testable hypothesis |

| Goals | Participants are comfortable with the researcher. They are honest and forthcoming, so that the researcher can make robust observations. | Others can repeat the findings of the study. Variables are defined and correlations between them are studied. |

| Drawbacks | If the researcher is biased, or is expecting to find certain results, it can be difficult to make completely objective observations. | Researchers may be so careful about measurement methods that they do not make connections to a greater context. |

| Some Methods | Interview, Focused group, Observation, Ethnography, Grounded Theory | Survey, Randomized controlled trial, Clinical trial, Experimental Statistics |

From A Dictionary of Nursing

- Critical Appraisal Tools from the Joanna Briggs Institute ▸ JBI’s critical appraisal tools assist in assessing the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers. ▸ Checklist for Systematic Reviews

- Trust It or Trash It ▸ This is a tool to help you think critically about the quality of health information (including websites, handouts, booklets, etc.). ▸ Created by the Genetic Alliance

- << Previous: Quantitative

- Next: Mixed Methods >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 10:14 AM

- URL: https://simmons.libguides.com/Quantitative-Qualitative-Articles

- Open access

- Published: 05 September 2024

Breaking the taboo of using the nursing process: lived experiences of nursing students and faculty members

- Amir Shahzeydi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9095-2424 1 , 2 ,

- Parvaneh Abazari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4024-2867 3 , 4 ,

- Fatemeh Gorji-varnosfaderani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6830-982X 5 ,

- Elaheh Ashouri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7566-6566 6 ,

- Shahla Abolhassani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5191-7586 6 &

- Fakhri Sabohi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1448-6606 6

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 621 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Despite the numerous advantages of the nursing process, nursing students often struggle with utilizing this model. Therefore, studies suggest innovative teaching methods to address this issue. Teaching based on real clinical cases is considered a collaborative learning method that enhances students’ active learning for the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In this method, students can acquire sufficient knowledge about patient care by accessing authentic information.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the experiences of nursing students and faculty members regarding the implementation of nursing process educational workshops, based on real case studies.

A qualitative descriptive study.

Participants

9 Nursing students and 7 faculty members from the Isfahan School of Nursing and Midwifery who attended the workshops.

This qualitative descriptive study was conducted from 2021 to 2023. Data was collected through semi-structured individual and focus group interviews using a qualitative content analysis approach for data analysis.

After analyzing the data, a theme titled “Breaking Taboos in the Nursing Process” was identified. This theme consists of four categories: “Strengthening the Cognitive Infrastructure for Accepting the Nursing Process,” “Enhancing the Applicability of the Nursing Process,” “Assisting in Positive Professional Identity,” and “Facilitating a Self-Directed Learning Platform.” Additionally, thirteen subcategories were obtained.

The data obtained from the present study showed that conducting nursing process educational workshops, where real clinical cases are discussed, analyzed, and criticized, increases critical thinking, learning motivation, and understanding of the necessity and importance of implementing the nursing process. Therefore, it is recommended that instructors utilize this innovative and effective teaching method for instructing the nursing process.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The nursing process is a systematic and logical method for planning and providing nursing care [ 1 ] that provides an opportunity for nurses to efficiently and dynamically utilize their knowledge and expertise. It also creates a common language, known as nursing diagnosis, which facilitates action, promotes creative solutions, and minimizes errors in patient care [ 2 ]. Clinical education, based on the nursing process, provides an appropriate setting for nursing students to gain clinical experiences and foster professional development [ 3 ].

Despite the numerous advantages, nursing students face difficulties in implementing this model in various countries [ 4 , 5 ], lack of appropriate knowledge, lack of clinical practice, and insufficient learning are among the most significant obstacles to the implementation of the nursing process by students. This can be attributed to the poor quality of education regarding this important nursing care model. Therefore, it is necessary for educators in this field to use innovative and participatory teaching methods [ 3 , 6 ]. According to research conducted in Iran, 72% of nursing faculty members use passive teaching methods. Meanwhile, 92% of nursing students prefer active and innovative learning methods over traditional and passive methods [ 7 ]. Therefore, the use of modern methods, which aim to stimulate students’ thinking and enhance their responsiveness in acquiring and applying knowledge, can be effective [ 6 ].

Case-based learning is a collaborative learning method that aims to develop and enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills [ 8 ]. Teaching the nursing process based on clinical and real cases can be very important in terms of promoting critical thinking, simulating real experiences, enhancing clinical judgment, and ultimately improving the quality and effectiveness of education [ 8 , 9 ]. In this method, students gain sufficient knowledge about patient care by accessing real information, improving their skills in patient assessment, and gaining personal nursing experience. This leads to a better understanding of comprehensive care and prepares individuals for future professional roles [ 9 ].

Very few studies have been conducted on teaching methods and their impact on the quality of nursing process [ 10 , 11 ]. In Iran, case-based trainings have mostly focused on hypothetical cases [ 1 , 12 ]. In other countries, most studies conducted on the case-based educational method have not focused on the nursing process. The few studies that have been conducted on the nursing process have either not been based on real clinical cases [ 13 ] or, if clinical cases have been researched, the studies have been conducted quantitatively [ 8 , 9 ] While qualitative research provides researchers with more opportunities to discover and explain the realities of the educational environment and gain a better understanding of many challenging aspects related to the nursing education process. Researchers are able to provide a practical model that helps improve and enhance the current process by gaining insight and a deep understanding of what is happening in the field of study [ 14 ]. This study represents the first qualitative research that describes the lived experiences of nursing students and faculty members regarding the teaching of the nursing process through real-based case workshops.

Study design

This qualitative descriptive study was conducted from 2021 to 2023. Qualitative descriptive studies typically align with the naturalistic inquiry paradigm, which emphasizes examining phenomena in their natural settings as much as possible within the context of research. Naturalistic inquiry, rooted in a constructivist viewpoint, enables a deeper understanding of phenomena by observing them within the authentic social world we inhabit [ 15 ]. In this type of study, researchers provide a comprehensive summary of an extraordinary occurrence or circumstance of interest and its related factors, but they do not delve into deep interpretation [ 16 ]. This study was undertaken to explore students and faculty members perceptions of the effect of the educational workshops on knowledge, skills and attitudes of students to the nursing process.

Setting and sample

Participants were selected from nursing students and faculty members who participated in nursing process workshops (Table 1 ). The criteria for entry into the study included volunteering to participate in the study and attending at least 3 sessions of the workshops.

Workshop details

The workshops were held in the conference hall of the Nursing and Midwifery Faculty. They consisted of 9 sessions, each lasting 2 h, from 16:00 to 18:00. Students from terms 2 to 8 and faculty members participated in these workshops. Each session was attended by an average of 60 members. Despite the inconvenience of scheduling the sessions outside of the official class hours, all the members stayed until the end of the meeting, showing a keen interest in the material and actively participating in discussions. Attendance was open to all students and faculty members, and participants in each of the workshop sessions were not the same.

It should be noted that all workshops were accompanied by a specialized instructor in the field of the nursing process, as well as a specialized instructor in the field of the specific disease being discussed. The details of these workshops are summarized in three stages:

First Stage

Step 1 . The researcher visited one of the inpatient clinical wards of the hospital based on the assigned topic for each workshop. They selected a patient, conducted a comprehensive assessment, and recorded the information using Gordon’s assessment form. This included the patient’s current and past medical history, paraclinical tests, physical examinations, medications, and information gathered from credible sources such as interviews with the patient and their family, medical records, and the patient’s treatment and care interventions documented in their medical file and Cardex.

Step 2 . Preparing the presentation file, which includes the following items:

Writing the comprehensive patient assessment based on step one.

Writing actual and at-risk nursing diagnoses according to PES (Problem/ Etiology/ Signs and Symptoms) and PE (Problem/ Etiology) rules, as well as collaborative problems, and then prioritizing them based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Writing objectives and outcomes for each nursing diagnosis based on the SMART (Specific/ Measurable/ Attainable/ Realistic/ Time Bound).

Writing nursing interventions (based on objectives and outcomes), along with the rationales according to evidence-based, up-to-date, and reliable sources for each intervention.

Step 3 . Sending the presentation file to an expert professor in the field of nursing process for review and implementing her comments.

Second stage

Step 1 . Announcing the date and time of the workshop session to students and faculty members.

Step 2 . Providing students and faculty members with a comprehensive patient assessment.

Third stage (workshop implementation)

Step 1. Presenting all stages of the nursing process based on the case study:

Providing a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s condition. (Giving time for students, faculty members, and presenters to discuss with each other, express their comments, and summarize)

Presenting diagnoses along with the objectives and expected outcomes. (Giving time for students, faculty members, and presenters to discuss with each other, express their comments, and summarize)

Presentation of nursing interventions. (Giving time for students, faculty members, and presenters to discuss with each other, express their comments, and summarize)

Presentation on assessing the level of achievement of expected outcomes and evaluating interventions. (Giving time for students, faculty members, and presenters to discuss with each other, express their comments, and summarize)

Data Collection Tools

Demographic questionnaire.

It included age, gender, Position, degree and number of sessions attended in the workshop.

Semi-structured interview

It included the following questions:

What was your motivation to attend these meetings?

Before entering the nursing process meetings, what did you expect from the meeting?

How many of your expectations were met by participating in the meetings?

How much did these meetings help you in applying the nursing process in the clinical setting?

What do you think about the continuation of such meetings?

Data collection

After obtaining official permission from the university in 2021, the phone numbers of students and faculty members who participated in more sessions of the workshop were collected in 2023. A specific time and location were subsequently arranged to contact and interview participants who had indicated their willingness to take part in the study. Approximately 40 individuals expressed their consent to participate; however, data saturation was achieved after interviewing 16 participants. It is important to note that interviews were conducted through both individual sessions and focus groups. Individual interviews were carried out with 3 faculty members, while two focus groups were conducted separately with 9 students and 4 faculty members.

Individual Interviews

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner and began with a general question to establish initial and closing communication. These interviews were conducted by one of the researchers who holds a PhD in nursing and has published several qualitative articles in reputable journals. In each of these sessions, the interviewer introduced themselves and welcomed the participants. The goals of the session were discussed, and participants were given complete freedom to express their opinions. The interviewer refrained from interfering or reacting to their opinions, and the information discussed was kept completely confidential under the guise of a code. Participants were subsequently asked to provide consent for voice recording during the interviews. Once consent was obtained from the participants, their voices were recorded. Each individual interview lasted between 30 and 45 min.

Focus Group Interviews

All the conditions of these interviews were similar to individual interviews. However, in focus group sessions, an additional researcher acted as an assistant to the main interviewer. The assistant’s role was to determine the order of speaking based on the participants’ requests, observe their facial expressions while speaking, and take necessary notes. Each of the focus group sessions lasted approximately 5 h. It should be noted that participant selection and sampling continued until data saturation was achieved. Saturation of data refers to the repetition of information and the confirmation of previously collected data.

Data analysis

The qualitative content analysis approach proposed by Graneheim and Lundman was used for data analysis [ 16 ]. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim (The transcripts were sent to the participants for feedback and were approved by them), and then each word was carefully examined to identify codes Two independent individuals encoded the data. Words that accurately represented thoughts or concepts within the data were highlighted. Then, the researcher added her own notes about his thoughts, interpretations of the text, and initial analysis of the text. With the progression of this process, appropriate names for the codes emerged, and the codes were organized into subcategories. These subcategories were created to organize and categorize the codes within clusters. The researcher reorganized the subcategories based on their relationships, condensing them into a smaller number of organizational categories. And then the concepts of each category, subcategory, and code were developed.

Trustworthiness

Data was managed using the Lincoln and Guba criteria. These criteria include acceptability, which is equivalent to internal validity; transferability, which is equivalent to external validity; similarity, which is equivalent to reliability; and verifiability, which is equivalent to objectivity [ 17 ]. The use of member checks by participants is considered a technique for exploring the credibility of results. In this regard, the interview text and the primary codes extracted from it were made available to several participants to verify the accuracy with their experiences. External supervision was employed to ensure that the criterion of internal consistency was met. For this purpose, the data was given to a researcher who did not participate in the study. If there was agreement in the interpretation of the data, it confirmed the presence of internal consistency. Finally, an audit or verification inquiry was conducted. The researcher accurately recorded and reported all stages and processes of the research from beginning to end. This allows external supervisors to conduct audits and assess the credibility of the findings.

Data analysis resulted in the emergence of 13 subcategories, 4 categories, and 1 theme (Table 2 ).

Strengthening the intellectual infrastructure of accepting the nursing process

Subcategories such as “improving nursing perception,” “strengthening critical thinking,” “evidence-based nursing practice,” and “filling an educational gap” contributed to the emergence of the category “Strengthening the intellectual infrastructure of accepting the nursing process.”

Improving nursing perception

Participants’ experiences indicate the significant positive impact of the workshop on improving students’ perception of the nursing process. Most nurses in departments do not provide patient care based on the nursing process. As a result, students do not have the opportunity to practically experience the real application of the nursing process in the department. Instead, they only perceive the nursing process as a written task.

For me, it was a question of what the nursing process is, for instance. How difficult is it?” and it really helped me overcome my fear in a way. (P3 student) Usually, they would explain the nursing process to us, but it was not practical or based on real cases, like this. (P1 Student)

Strengthening critical thinking

Critical thinking is a fundamental skill in the nursing process that involves various stages and activities. These include questioning to gather adequate information, validating and analyzing information to comprehend the problem and its underlying factors, evaluating interventions, and making appropriate decisions for effective problem-solving. The experiences of the participating students clearly reflected the formation of these stages during the workshop sessions.

I learned in the workshop about the importance of using critical thinking to successfully connect knowledge and practice. It’s a shame that critical thinking has not been cultivated in the minds of students, and these workshops have laid the foundation for it in our minds. (P6 student) Students often come across hypothetical cases in textbooks, but when they are confronted with real cases, the circumstances are different… This is when critical thinking becomes crucial and the art of nursing is demonstrated… These sessions have made a significant contribution to this subject. (P15 Faculty member)

Evidence-based nursing practice

One of the features of the sessions was that in introducing the case from assessment to evaluation, to justify the rationale and process of collecting and formulating nursing diagnoses, establishing expected outcomes, and providing reasons for each intervention, relied on up-to-date and reliable nursing and medical resources

It had a strong scientific foundation, consistently emphasizing the importance of evidence-based practices and a scientific approach, effectively communicating this perspective to audience. (P2 Student). I became familiar with the book ‘Carpenito,’ and it helped me a lot in understanding my shortcomings. (P3 student). In my opinion, one of the factors that contributed to the effectiveness of the work was consulting the references. They emphasized that as a nurse, I should not solely rely on my personal opinion but should instead base my actions on the reference materials (P14 Faculty member).

Filling an educational gap

From the perspective of workshop participants, the workshop has increased their awareness of their limited knowledge about the application of the nursing process. It has also helped them recognize their shortcomings, and motivated them to pursue additional studies in this field.

Exactly, there was a vacant spot for this educational program in our classes. And there should have been sessions that would prove to us that nursing is not just about the theoretical concepts that faculty members teach in class. (P5 Student) The nursing process has a theoretical aspect that students learn, but when they attempt to apply it in practice, they often encounter difficulties. These sessions helped to fill the gap between theory and practice. (P15 Faculty member)

Practicality of the nursing process

Subcategories of “linking the nursing process with team care,” “demonstrating the role of the nursing process in improving care quality,” “comprehensive view in care,” and “student’s guiding light in the clinic,” Created the category “Practicality of the Nursing Process”.

Linking the nursing process with team care

Participants’ experiences indicated that participating in nursing process sessions helped them realize that the nursing process is a model that will lead to collaborative team care. Prior to attending these sessions, nursing students like nurses considered their duty to be solely executing medical orders under the supervision of clinical faculty members and staff nurses.

I realized that in certain situations, I am able to confidently express my opinion to the doctor. For instance, if I believe that a particular course of action would yield better results, I can easily communicate this and provide reasons to support my viewpoint (P7 Student). Teaching the pathway when it’s categorized with knowing what we’re assessing… Let’s go up to the patient; our confidence can really guide them along with us as we progress step by step and systematically. Often, the patient accompanies us, and sometimes they voice their unspoken concerns, which helps improve their care. It means the patient themselves are partnering with us. (P6 student)

Demonstrating the role of the nursing process in improving care quality

Strengthening the attitude and belief in the role and application of the nursing process in improving the quality of care was another concept that emerged from the experiences of the students. Presenting reports on the implementation of the nursing process on real cases led them to believe that providing care based on the nursing process results in organized care planning and enhances the quality of care.

In these workshops, the needs of patients were prioritized, documented, and then organized systematically. This concept remains ingrained in a person’s mind and enables us to deliver comprehensive care to the patient without overlooking any aspect. This has been very helpful for me, and now it greatly assists me in the clinic. (P4 Student) Another great aspect of these sessions was the emphasis they placed on the nurse-patient relationship. I could see that the students had been following up with patients for a while and implementing the process. This was very helpful to me. For instance, diagnosing based on the patient’s current health status was an ongoing process. In my opinion, the connection between the patient and nurse was more important and practical for me.(P1 Student).

Comprehensive view in care

Attention to the patient’s care needs went beyond focusing solely on physiological aspects. It involved a holistic approach that addressed the patient’s needs related to all aspects of biology, psychology, society, spirituality, and economics. This was clearly reflected in the students’ experiences during the nursing process sessions.

…I paid attention to all aspects of the patient. For example, perhaps I overlooked her anxiety issue and never took it into consideration. However, I eventually came to realize that addressing anxiety is crucial, as it is one of the primary concerns and needs of patients. (P2 Student) …that the students had a holistic view of the patient (they had examined the patient thoroughly, including the patient’s skin, etc.) and had compiled a list of the patient’s issues, paying attention to all aspects of the patient (P14 Faculty member).

Student’s guiding light in the clinic

One of the significant accomplishments of nursing process sessions, as evidenced by the students’ experiences, was the role of these sessions in assisting students in overcoming confusion and uncertainty during their internships. These sessions enabled them to establish a mental connection between the theoretical knowledge learned in the classroom and its application in the real clinical setting, also helped them understand how to effectively utilize their theoretical knowledge in a clinical learning environment.

.I was feeling incredibly lost and confused. I didn’t know what steps to take next. Many of us find ourselves in this situation, unsure of what to do. At least for me, as someone who grasps concepts better through examples, the case-based studies conducted during the workshop had a significant impact. (P6 Student)

Supporting a positive professional identity

Two subcategories, “highlighting the importance of nursing science” and “reforming the perception of nursing nature,” have contributed to the development of the category “supporting a positive professional identity.”

Highlighting the importance of nursing science

Based on students’ experiences, the nursing process sessions have been able to answer an important question. Why should they be bombarded with information and expected to possess extensive knowledge in the field of disease recognition, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and nursing care during their studies? The students believed that the content of the nursing process sessions clarified the necessity and importance of nursing knowledge for them. In these sessions, they came to believe that providing care based on the nursing process requires extensive nursing knowledge.

. In my opinion, this work showcases a significant strength by highlighting the importance of working scientifically as a nurse. Personally, I feel its impact on myself is profound. (P2 Student) In my opinion, it was very touching and captivating because it accurately portrayed the immense power of a nurse. However, amidst the demanding and difficult nature of the job, what specific details should a nurse pay attention to? and it is precisely these details that shape the work of a nurse. It was very interesting and beneficial for me. (P5 student)

Reforming the perception of nursing nature

The student is seeking ways to comprehend and value the practical aspects of nursing as a genuine science, assuming that nursing is indeed regarded as a science. Participants’ experiences have shown that nursing process sessions have been able to address this identity challenge and modify and enhance students’ understanding of the nature of nursing.

I used to believe that nursing was primarily an art complemented by science until I entered term 2 and participated in these workshops. And now I realize that it has the scientific foundation that I expected from an evidence-based practice. (P5 student). . The important point was that lower-term students, who sometimes lacked motivation and thought nursing had nothing to offer, gained motivation and had a change in perspective by attending these sessions. (P2 faculy members)

Self-directed learning facilitator

Subcategories of “stimulating a thirst for learning,” “creating a stress-free learning atmosphere,” and “teaching fishing,” formed the category of “self-directed learning facilitator.”

Stimulating a thirst for learning

Participants’ experiences indicated that the format of conducting sessions, ranging from step-by-step training to training accompanied by multiple examples, had a significant impact on creating a sense of necessity and stimulating learners’ motivation to learn.

First of all, the challenges that you yourself raised (faculty member) for example, why did you make this diagnosis?” Why did you include this action? Why is this a priority? Really, it shook me and made me think that maybe there is more to this, maybe there is more to the nursing process that I haven’t understood yet…. That’s why it became my motivation. (P3 student) …But these sessions helped me a lot. At least, they sparked my curiosity and motivated me to delve deeper into the subject. I began actively participating in these sessions and found them to be highly effective for my personal growth. (P6 student) In my opinion, one of the things that empowered the work was the act of seeking references. They emphasized that as a nurse, I should not solely rely on my personal opinion but should instead base my actions on credible sources. (P14 Faculty member)

Creating a stress-free learning atmosphere

Students believed that the absence of a legal requirement to attend these workshops, coupled with the understanding that their participation or non-participation would not be evaluated for grading purposes, would enable them to engage in these sessions without concern for their academic performance and in accordance with their own volition.