- Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comprehensive Overview and Latest Research Insights

- Dementia Prevention: Effective Strategies for Brain Health

- Senior Cognitive Function: Exploring Strategies for Mental Sharpness

- Neuroprotection: Strategies and Practices for Optimal Brain Health

- Aging Brain Health: Expert Strategies for Maintaining Cognitive Function

- Screen Time and Children’s Brain Health: Key Insights for Parents

- Autism and Brain Health: Unraveling the Connection and Strategies

- Dopamine and Brain Health: Crucial Connections Explained

- Serotonin and Brain Health: Uncovering the Connection

- Cognitive Aging: Understanding Its Impact and Progression

- Brain Fitness: Enhancing Cognitive Abilities and Mental Health

- Brain Health Myths: Debunking Common Misconceptions

- Brain Waves: Unlocking the Secrets of the Mind’s Signals

- Brain Inflammation: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

- Neurotransmitters: Unlocking the Secrets of Brain Chemistry

- Neurogenesis: Unraveling the Secrets of Brain Regeneration

- Mental Fatigue: Understanding and Overcoming Its Effects

- Neuroplasticity: Unlocking Your Brain’s Potential

- Brain Health: Essential Tips for Boosting Cognitive Function

- Brain Health: A Comprehensive Overview of Brain Functions and Its Importance Across Lifespan

- An In-depth Scientific Overview of Hydranencephaly

- A Comprehensive Overview of Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome (PTHS)

- An Extensive Overview of Autism

- Navigating the Brain: An In-Depth Look at The Montreal Procedure

- Gray Matter and Sensory Perception: Unveiling the Nexus

- Decoding Degenerative Diseases: Exploring the Landscape of Brain Disorders

- Progressive Disorders: Unraveling the Complexity of Brain Health

- Introduction to Embryonic Stem Cells

- Memory Training: Enhance Your Cognitive Skills Fast

- Mental Exercises for Kids: Enhancing Brain Power and Focus

- Senior Mental Exercises: Top Techniques for a Sharp Mind

- Nutrition for Aging Brain: Essential Foods for Cognitive Health

- ADHD and Brain Health: Exploring the Connection and Strategies

- Pediatric Brain Disorders: A Concise Overview for Parents and Caregivers

Child Cognitive Development: Essential Milestones and Strategies

- Brain Development in Children: Essential Factors and Tips for Growth

- Brain Health and Aging: Essential Tips for Maintaining Cognitive Function

- Pediatric Neurology: Essential Insights for Parents and Caregivers

- Nootropics Forums: Top Online Communities for Brain-Boosting Discussion

- Brain Health Books: Top Picks for Boosting Cognitive Wellbeing

- Nootropics Podcasts: Enhance Your Brainpower Today

- Brain Health Webinars: Discover Essential Tips for Improved Cognitive Function

- Brain Health Quizzes: Uncovering Insights for a Sharper Mind

- Senior Brain Training Programs: Enhance Cognitive Abilities Today

- Brain Exercises: Boost Your Cognitive Abilities in Minutes

- Neurofeedback: A Comprehensive Guide to Brain Training

- Mood Boosters: Proven Methods for Instant Happiness

- Cognitive Decline: Understanding Causes and Prevention Strategies

- Brain Aging: Key Factors and Effective Prevention Strategies

- Alzheimer’s Prevention: Effective Strategies for Reducing Risk

- Gut-Brain Axis: Exploring the Connection Between Digestion and Mental Health

- Meditation for Brain Health: Boost Your Cognitive Performance

- Sleep and Cognition: Exploring the Connection for Optimal Brain Health

- Mindfulness and Brain Health: Unlocking the Connection for Better Wellness

- Brain Health Exercises: Effective Techniques for a Sharper Mind

- Brain Training: Boost Your Cognitive Performance Today

- Cognitive Enhancers: Unlocking Your Brain’s Full Potential

- Neuroenhancers: Unveiling the Power of Cognitive Boosters

- Mental Performance: Strategies for Optimal Focus and Clarity

- Memory Enhancement: Proven Strategies for Boosting Brainpower

- Cognitive Enhancement: Unlocking Your Brain’s Full Potential

- Children’s Brain Health Supplements: Enhancing Cognitive Development

- Brain Health Supplements for Seniors: Enhancing Cognitive Performance and Memory

- Oat Straw Benefits

- Nutrition for Children’s Brain Health: Essential Foods and Nutrients for Cognitive Development

- Nootropic Drug Interactions: Essential Insights and Precautions

- Personalized Nootropics: Enhance Cognitive Performance the Right Way

- Brain Fog Remedies: Effective Solutions for Mental Clarity

- Nootropics Dosage: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimal Use

- Nootropics Legality: A Comprehensive Guide to Smart Drugs Laws

- Nootropics Side Effects: Uncovering the Risks and Realities

- Nootropics Safety: Essential Tips for Smart and Responsible Use

- GABA and Brain Health: Unlocking the Secrets to Optimal Functioning

- Nootropics and Anxiety: Exploring the Connection and Potential Benefits

- Nootropics for Stress: Effective Relief & Cognitive Boost

- Nootropics for Seniors: Enhancing Cognitive Health and Well-Being

- Nootropics for Athletes: Enhancing Performance and Focus

- Nootropics for Students: Enhance Focus and Academic Performance

- Nootropic Stacks: Unlocking the Power of Cognitive Enhancers

- Nootropic Research: Unveiling the Science Behind Cognitive Enhancers

- Biohacking: Unleashing Human Potential Through Science

- Brain Nutrition: Essential Nutrients for Optimal Cognitive Function

- Synthetic Nootropics: Unraveling the Science Behind Brain Boosters

- Natural Nootropics: Unlocking Cognitive Enhancements through Nature

- Brain Boosting Supplements: Enhancing Cognitive Performance Naturally

- Smart Drugs: Enhancing Cognitive Performance and Focus

- Concentration Aids: Enhancing Focus and Productivity in Daily Life

- Nootropics: Unleashing Cognitive Potential and Enhancements

- Best Nootropics 2024

- Alpha Brain Review 2023

- Neuriva Review

- Neutonic Review

- Prevagen Review

- Nooceptin Review

- Nootropics Reviews: Unbiased Insights on Brain Boosters

- Phenylpiracetam: Unlocking Cognitive Enhancement and Brain Health

- Modafinil: Unveiling Its Benefits and Uses

- Racetams: Unlocking Cognitive Enhancement Secrets

- Adaptogens for Brain Health: Enhancing Cognitive Function Naturally

- Vitamin B for Brain Health: Unveiling the Essential Benefits

- Caffeine and Brain Health: Unveiling the Connection

- Antioxidants for Brain: Enhancing Cognitive Function and Health

- Omega-3 and Brain Health: Unlocking the Benefits for Cognitive Function

- Brain-Healthy Foods: Top Picks for Boosting Cognitive Function

- Focus Supplements: Enhance Concentration and Mental Clarity Today

Child cognitive development is a fascinating and complex process that entails the growth of a child’s mental abilities, including their ability to think, learn, and solve problems. This development occurs through a series of stages that can vary among individuals. As children progress through these stages, their cognitive abilities and skills are continuously shaped by a myriad of factors such as genetics, environment, and experiences. Understanding the nuances of child cognitive development is essential for parents, educators, and professionals alike, as it provides valuable insight into supporting the growth of the child’s intellect and overall well-being.

Throughout the developmental process, language and communication play a vital role in fostering a child’s cognitive abilities . As children acquire language skills, they also develop their capacity for abstract thought, reasoning, and problem-solving. It is crucial for parents and caregivers to be mindful of potential developmental delays, as early intervention can greatly benefit the child’s cognitive development. By providing stimulating environments, nurturing relationships, and embracing diverse learning opportunities, adults can actively foster healthy cognitive development in children.

Key Takeaways

- Child cognitive development involves the growth of mental abilities and occurs through various stages.

- Language and communication are significant factors in cognitive development , shaping a child’s ability for abstract thought and problem-solving.

- Early intervention and supportive environments can play a crucial role in fostering healthy cognitive development in children.

Child Cognitive Development Stages

Child cognitive development is a crucial aspect of a child’s growth and involves the progression of their thinking, learning, and problem-solving abilities. Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget developed a widely recognized theory that identifies four major stages of cognitive development in children.

Sensorimotor Stage

The Sensorimotor Stage occurs from birth to about 2 years old. During this stage, infants and newborns learn to coordinate their senses (sight, sound, touch, etc.) with their motor abilities. Their understanding of the world begins to develop through their physical interactions and experiences. Some key milestones in this stage include object permanence, which is the understanding that an object still exists even when it’s not visible, and the development of intentional actions.

Preoperational Stage

The Preoperational Stage takes place between the ages of 2 and 7 years old. In this stage, children start to think symbolically, and their language capabilities rapidly expand. They also develop the ability to use mental images, words, and gestures to represent the world around them. However, their thinking is largely egocentric, which means they struggle to see things from other people’s perspectives. During this stage, children start to engage in pretend play and begin to grasp the concept of conservation, recognizing that certain properties of objects (such as quantity or volume) remain the same even if their appearance changes.

Concrete Operational Stage

The Concrete Operational Stage occurs between the ages of 7 and 12 years old. At this stage, children’s cognitive development progresses to more logical and organized ways of thinking. They can now consider multiple aspects of a problem and better understand the relationship between cause and effect . Furthermore, children become more adept at understanding other people’s viewpoints, and they can perform basic mathematical operations and understand the principles of classification and seriation.

Formal Operational Stage

Lastly, the Formal Operational Stage typically begins around 12 years old and extends into adulthood. In this stage, children develop the capacity for abstract thinking and can consider hypothetical situations and complex reasoning. They can also perform advanced problem-solving and engage in systematic scientific inquiry. This stage allows individuals to think about abstract concepts, their own thought processes, and understand the world in deeper, more nuanced ways.

By understanding these stages of cognitive development, you can better appreciate the complex growth process that children undergo as their cognitive abilities transform and expand throughout their childhood.

Key Factors in Cognitive Development

Genetics and brain development.

Genetics play a crucial role in determining a child’s cognitive development. A child’s brain development is heavily influenced by genetic factors, which also determine their cognitive potential , abilities, and skills. It is important to understand that a child’s genes do not solely dictate their cognitive development – various environmental and experiential factors contribute to shaping their cognitive abilities as they grow and learn.

Environmental Influences

The environment in which a child grows up has a significant impact on their cognitive development. Exposure to various experiences is essential for a child to develop essential cognitive skills such as problem-solving, communication, and critical thinking. Factors that can have a negative impact on cognitive development include exposure to toxins, extreme stress, trauma, abuse, and addiction issues, such as alcoholism in the family.

Nutrition and Health

Maintaining good nutrition and health is vital for a child’s cognitive development. Adequate nutrition is essential for the proper growth and functioning of the brain . Key micronutrients that contribute to cognitive development include iron, zinc, and vitamins A, C, D, and B-complex vitamins. Additionally, a child’s overall health, including physical fitness and immunity, ensures they have the energy and resources to engage in learning activities and achieve cognitive milestones effectively .

Emotional and Social Factors

Emotional well-being and social relationships can also greatly impact a child’s cognitive development. A supportive, nurturing, and emotionally healthy environment allows children to focus on learning and building cognitive skills. Children’s emotions and stress levels can impact their ability to learn and process new information. Additionally, positive social interactions help children develop important cognitive skills such as empathy, communication, and collaboration.

In summary, cognitive development in children is influenced by various factors, including genetics, environmental influences, nutrition, health, and emotional and social factors. Considering these factors can help parents, educators, and policymakers create suitable environments and interventions for promoting optimal child development.

Language and Communication Development

Language skills and milestones.

Children’s language development is a crucial aspect of their cognitive growth. They begin to acquire language skills by listening and imitating sounds they hear from their environment. As they grow, they start to understand words and form simple sentences.

- Infants (0-12 months): Babbling, cooing, and imitating sounds are common during this stage. They can also identify their name by the end of their first year. Facial expressions play a vital role during this period, as babies learn to respond to emotions.

- Toddlers (1-3 years): They rapidly learn new words and form simple sentences. They engage more in spoken communication, constantly exploring their language environment.

- Preschoolers (3-5 years): Children expand their vocabulary, improve grammar, and begin participating in more complex conversations.

It’s essential to monitor children’s language development and inform their pediatrician if any delays or concerns arise.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication contributes significantly to children’s cognitive development. They learn to interpret body language, facial expressions, and gestures long before they can speak. Examples of nonverbal communication in children include:

- Eye contact: Maintaining eye contact while interacting helps children understand emotions and enhances communication.

- Gestures: Pointing, waving goodbye, or using hand signs provide alternative ways for children to communicate their needs and feelings.

- Body language: Posture, body orientation, and movement give clues about a child’s emotions and intentions.

Teaching children to understand and use nonverbal communication supports their cognitive and social development.

Parent and Caregiver Interaction

Supportive interaction from parents and caregivers plays a crucial role in children’s language and communication development. These interactions can improve children’s language skills and overall cognitive abilities . Some ways parents and caregivers can foster language development are:

- Reading together: From an early age, reading books to children enhance their vocabulary and listening skills.

- Encouraging communication: Ask open-ended questions and engage them in conversations to build their speaking skills.

- Using rich vocabulary: Expose children to a variety of words and phrases, promoting language growth and understanding.

By actively engaging in children’s language and communication development, parents and caregivers can nurture cognitive, emotional, and social growth.

Cognitive Abilities and Skills

Cognitive abilities are the mental skills that children develop as they grow. These skills are essential for learning, adapting, and thriving in modern society. In this section, we will discuss various aspects of cognitive development, including reasoning and problem-solving, attention and memory, decision-making and executive function, as well as academic and cognitive milestones.

Reasoning and Problem Solving

Reasoning is the ability to think logically and make sense of the world around us. It’s essential for a child’s cognitive development, as it enables them to understand the concept of object permanence , recognize patterns, and classify objects. Problem-solving skills involve using these reasoning abilities to find solutions to challenges they encounter in daily life .

Children develop essential skills like:

- Logical reasoning : The ability to deduce conclusions from available information.

- Perception: Understanding how objects relate to one another in their environment.

- Schemes: Organizing thoughts and experiences into mental categories.

Attention and Memory

Attention refers to a child’s ability to focus on specific tasks, objects, or information, while memory involves retaining and recalling information. These cognitive abilities play a critical role in children’s learning and academic performance . Working memory is a vital component of learning, as it allows children to hold and manipulate information in their minds while solving problems and engaging with new tasks.

- Attention: Focuses on relevant tasks and information while ignoring distractions.

- Memory: Retains and retrieves information when needed.

Decision-Making and Executive Function

Decision-making is the process of making choices among various alternatives, while executive function refers to the higher-order cognitive processes that enable children to plan, organize, and adapt in complex situations. Executive function encompasses components such as:

- Inhibition: Self-control and the ability to resist impulses.

- Cognitive flexibility: Adapting to new information or changing circumstances.

- Planning: Setting goals and devising strategies to achieve them.

Academic and Cognitive Milestones

Children’s cognitive development is closely linked to their academic achievement. As they grow, they achieve milestones in various cognitive domains that form the foundation for their future learning. Some of these milestones include:

- Language skills: Developing vocabulary, grammar, and sentence structure.

- Reading and mathematics: Acquiring the ability to read and comprehend text, as well as understanding basic mathematical concepts and operations.

- Scientific thinking: Developing an understanding of cause-and-effect relationships and forming hypotheses.

Healthy cognitive development is essential for a child’s success in school and life. By understanding and supporting the development of their cognitive abilities, we can help children unlock their full potential and prepare them for a lifetime of learning and growth.

Developmental Delays and Early Intervention

Identifying developmental delays.

Developmental delays in children can be identified by monitoring their progress in reaching cognitive, linguistic, physical, and social milestones. Parents and caregivers should be aware of developmental milestones that are generally expected to be achieved by children at different ages, such as 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, 18 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, and 5 years. Utilizing resources such as the “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” program can help parents and caregivers recognize signs of delay early in a child’s life.

Resources and Support for Parents

There are numerous resources available for parents and caregivers to find information on developmental milestones and to learn about potential developmental delays, including:

- Learn the Signs. Act Early : A CDC initiative that provides pdf checklists of milestones and resources for identifying delays.

- Parental support groups : Local and online communities dedicated to providing resources and fostering connections between families experiencing similar challenges.

Professional Evaluations and Intervention Strategies

If parents or caregivers suspect a developmental delay, it is crucial to consult with healthcare professionals or specialists who can conduct validated assessments of the child’s cognitive and developmental abilities. Early intervention strategies, such as the ones used in broad-based early intervention programs , have shown significant positive impacts on children with developmental delays to improve cognitive development and outcomes.

Professional evaluations may include:

- Pediatricians : Primary healthcare providers who can monitor a child’s development and recommend further assessments when needed.

- Speech and language therapists : Professionals who assist children with language and communication deficits.

- Occupational therapists : Experts in helping children develop or improve on physical and motor skills, as well as social and cognitive abilities.

Depending on the severity and nature of the delays, interventions may involve:

- Individualized support : Tailored programs or therapy sessions specifically developed for the child’s needs.

- Group sessions : Opportunities for children to learn from and interact with other children experiencing similar challenges.

- Family involvement : Parents and caregivers learning support strategies to help the child in their daily life.

Fostering Healthy Cognitive Development

Play and learning opportunities.

Encouraging play is crucial for fostering healthy cognitive development in children . Provide a variety of age-appropriate games, puzzles, and creative activities that engage their senses and stimulate curiosity. For example, introduce building blocks and math games for problem-solving skills, and crossword puzzles to improve vocabulary and reasoning abilities.

Playing with others also helps children develop social skills and better understand facial expressions and emotions. Provide opportunities for cooperative play, where kids can work together to achieve a common goal, and open-ended play with no specific rules to boost creativity.

Supportive Home Environment

A nurturing and secure home environment encourages healthy cognitive growth. Be responsive to your child’s needs and interests, involving them in everyday activities and providing positive reinforcement. Pay attention to their emotional well-being and create a space where they feel safe to ask questions and explore their surroundings.

Promoting Independence and Decision-Making

Support independence by allowing children to make decisions about their playtime, activities, and daily routines. Encourage them to take age-appropriate responsibilities and make choices that contribute to self-confidence and autonomy. Model problem-solving strategies and give them opportunities to practice these skills during play, while also guiding them when necessary.

Healthy Lifestyle Habits

Promote a well-rounded lifestyle, including:

- Sleep : Ensure children get adequate and quality sleep by establishing a consistent bedtime routine.

- Hydration : Teach the importance of staying hydrated by offering water frequently, especially during play and physical activities.

- Screen time : Limit exposure to electronic devices and promote alternative activities for toddlers and older kids.

- Physical activity : Encourage children to engage in active play and exercise to support neural development and overall health .

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key stages of child cognitive development.

Child cognitive development can be divided into several key stages based on Piaget’s theory of cognitive development . These stages include the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), preoperational stage (2-7 years), concrete operational stage (7-11 years), and formal operational stage (11 years and beyond). Every stage represents a unique period of cognitive growth, marked by the development of new skills, thought processes, and understanding of the world.

What factors influence cognitive development in children?

Several factors contribute to individual differences in child cognitive development, such as genetic and environmental factors. Socioeconomic status, access to quality education, early home environment, and parental involvement all play a significant role in determining cognitive growth. In addition, children’s exposure to diverse learning experiences, adequate nutrition, and mental health also influence overall cognitive performance .

How do cognitive skills vary during early childhood?

Cognitive skills in early childhood evolve as children progress through various stages . During the sensorimotor stage, infants develop fundamental skills such as object permanence. The preoperational stage is characterized by the development of symbolic thought, language, and imaginative play. Children then enter the concrete operational stage, acquiring the ability to think logically and solve problems. Finally, in the formal operational stage, children develop abstract reasoning abilities, complex problem-solving skills and metacognitive awareness.

What are common examples of cognitive development?

Examples of cognitive development include the acquisition of language and vocabulary, the development of problem-solving skills, and the ability to engage in logical reasoning. Additionally, memory, attention, and spatial awareness are essential aspects of cognitive development. Children may demonstrate these skills through activities like puzzle-solving, reading, and mathematics.

How do cognitive development theories explain children’s learning?

Piaget’s cognitive development theory suggests that children learn through active exploration, constructing knowledge based on their experiences and interactions with the world. In contrast, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes the role of social interaction and cultural context in learning. Both theories imply that cognitive development is a dynamic and evolving process, influenced by various environmental and psychological factors.

Why is it essential to support cognitive development in early childhood?

Supporting cognitive development in early childhood is critical because it lays a strong foundation for future academic achievement, social-emotional development, and lifelong learning. By providing children with diverse and enriching experiences, caregivers and educators can optimize cognitive growth and prepare children to face the challenges of today’s complex world. Fostering cognitive development early on helps children develop resilience, adaptability, and critical thinking skills essential for personal and professional success.

Direct Your Visitors to a Clear Action at the Bottom of the Page

E-book title.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 62, 2011, review article, the development of problem solving in young children: a critical cognitive skill.

- Rachel Keen 1

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22904; email: [email protected] * *Photograph by Cat Thrasher

- Vol. 62:1-21 (Volume publication date January 2011) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130730

- First published as a Review in Advance on September 03, 2010

- © Annual Reviews

Problem solving is a signature attribute of adult humans, but we need to understand how this develops in children. Tool use is proposed as an ideal way to study problem solving in children less than 3 years of age because overt manual action can reveal how the child plans to achieve a goal. Motor errors are as informative as successful actions. Research is reviewed on intentional actions, beginning with block play and progressing to picking up a spoon in different orientations, and finally retrieving objects with rakes and from inside tubes. Behavioral and kinematic measures of motor action are combined to show different facets of skill acquisition and mastery. We need to design environments that encourage and enhance problem solving from a young age. One goal of this review is to excite interest and spur new research on the beginnings of problem solving and its elaboration during development.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Adalbjornsson CF , Fischman MG , Rudisill ME . 2008 . The end-state comfort effect in young children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 79 : 36– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Baker RK , Keen R . 2007 . Tool use by young children: choosing the right tool for the task Presented at biennial meet Soc. Res. Child Dev. Boston, MA: [Google Scholar]

- Bascandziev I , Harris PL . 2010 . The role of testimony in young children's solution of a gravity-driven invisible displacement task. Cogn. Dev. In press [Google Scholar]

- Bates E , Carlson-Luden V , Bretherton I . 1980 . Perceptual aspects of tool using in infancy. Infant Behav. Dev. 3 : 127– 40 [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N . 1969 . Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant Development New York: Psychol. Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Berthier NE , Clifton RK , Gullipalli V , McCall DD , Robin DJ . 1996 . Visual information and object size in the control of reaching. J. Motor Behav. 28 : 187– 97 [Google Scholar]

- Brown A . 1990 . Domain-specific principles affect learning and transfer in children. Cogn. Sci. 14 : 107– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J . 1973 . Organization of early skilled action. Child Dev. 44 : 1– 11 [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y , Keen R , Rosander K , von Hofsten C . 2010 . Movement planning reflects skill level and age change in toddlers. Child Dev. In press [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z , Siegler R . 2000 . Across the great divide: bridging the gap between understanding of toddlers' and other children's thinking. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 65 : 2 i– vii 1– 96 [Google Scholar]

- Claxton LJ , Keen R , McCarty ME . 2003 . Evidence of motor planning in infant reaching behavior. Psychol. Sci. 14 : 354– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Claxton LJ , McCarty ME , Keen R . 2009 . Self-directed action affects planning in tool-use tasks with toddlers. Infant Behav. Dev. 32 : 230– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Clifton RK. 2002 . Learning about infants. Conceptions of Development: Lessons from the Laboratory DJ Lewkowicz, R Lickliter 135– 63 New York: Psychol. Press [Google Scholar]

- Clifton RK , Rochat P , Litovsky RY , Perris EE . 1991 . Object representation guides infants' reaching in the dark. J. Exp. Psychol.: Hum. Percept. Perform. 17 : 323– 29 [Google Scholar]

- Clifton RK , Rochat P , Robin DJ , Berthier NE . 1994 . Multimodal perception in the control of infant reaching. J. Exp. Psychol.: Hum. Percept. Perform. 20 : 876– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Connolly K , Dalgleish M . 1989 . The emergence of a tool-using skill in infancy. Dev. Psychol. 6 : 894– 912 [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta D , Thelen E . 2002 . Behavioral fluctuations and the development of manual asymmetries in infancy: contributions of the dynamic system approach. Handbook of Neuropsychology: Child Neuropsychology, Vol. 8 , Pt. 1 SJ Segalowitz, I Rapin 309– 28 Amsterdam: Elsevier Sci. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta D , Williams J , Snapp-Childs W . 2006 . Plasticity in the development of handedness: evidence from normal development and early asymmetric brain injury. Dev. Psychobiol. 48 : 460– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J . 2005 . Collapse: Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed New York: Penguin [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL , Scholnick EK . 1997 . An evolving “blueprint” for planning: psychological requirements, task characteristics, and social-cultural influences. The Developmental Psychology of Planning: Why, How, and When Do We Plan? SL Friedman, EK Scholnick 3– 22 Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EJ , Pick AD . 2000 . An Ecological Approach to Perceptual Learning and Development. New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K , Golinkoff RM , Berk LE , Singer DG . 2009 . A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Presenting the Evidence New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Hood BM . 1995 . Gravity rules for 2- to 4-year-olds?. Cogn. Dev. 10 : 577– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Joh A , Jaswal V , Keen R . 2010 . Imagining a way out of the gravity bias: preschoolers can visualize the solution to a spatial problem. Child Dev In press [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Frey SH , McCarty ME , Keen R . 2004 . Reaching beyond spatial perception: effects of intended future actions on visually guided prehension. Visual Cogn. 11 : 371– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Kohler W . 1927 . The Mentality of Apes New York: Harcourt [Google Scholar]

- Koslowski B , Bruner JS . 1972 . Learning to use a lever. Child Dev. 43 : 790– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Kosslyn SM . 1975 . Information representation in visual images. Cogn. Psychol. 7 : 341– 70 [Google Scholar]

- Lockman JJ . 2000 . A perception-action perspective on tool use development. Child Dev. 71 : 137– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Lockman JJ , Ashmead DH , Bushnell EW . 1984 . The development of anticipatory hand orientation during infancy. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 37 : 176– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Manoel EJ , Moreira CRP . 2005 . Planning manipulative hand movements: Do young children show the end-state comfort effect?. J. Hum. Movement Stud. 49 : 93– 114 [Google Scholar]

- Marteniuk RG , MacKenzie CL , Jeannerod M , Athenes A , Dugas C . 1987 . Constraints on human arm movement trajectories. Can. J. Psychol. 41 : 365– 78 [Google Scholar]

- McCarty ME , Clifton RK , Ashmead DH , Lee P , Goubet N . 2001a . How infants use vision for grasping objects. Child Dev. 72 : 973– 87 [Google Scholar]

- McCarty ME , Clifton RK , Collard RR . 1999 . Problem solving in infancy: the emergence of an action plan. Dev. Psychol. 35 : 1091– 101 [Google Scholar]

- McCarty ME , Clifton RK , Collard RR . 2001b . The beginnings of tool use by infants and toddlers. Infancy 2 : 233– 56 [Google Scholar]

- McCarty ME , Keen R . 2005 . Facilitating problem-solving performance among 9- and 12-month-old infants. J. Cogn. Dev. 6 : 209– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Metevier CM . 2006 . Tool-using in rhesus monkeys and 36-month-old children: acquisition, comprehension, and individual differences PhD thesis Univ. Mass. Amherst: [Google Scholar]

- Metevier CM , Baker RK , Keen R . 2007 . Knowing how to use tools independently does not guarantee their use in sequence Poster at Soc. Res. Child Dev. Boston, MA: [Google Scholar]

- Michel GF. 1983 . Development of hand-use preference during infancy. Manual Specialization and the Developing Brain G Young, S Segalowitz, C Cortea, S Trehub 33– 70 New York: Academic [Google Scholar]

- Newell KM , Scully DM , McDonald PV , Baillargeon R . 1989 . Task constraints and infant grip configurations. Dev. Psychobiol. 22 : 817– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J . 1952 . The Origins of Intelligence New York: Int. Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Richards CA , Sanderson JA . 1999 . The role of imagination in facilitating deductive reasoning in 2-, 3-, and 4-year-olds. Cognition 72 : B1– 9 [Google Scholar]

- Rieser JJ , Garing AE , Young MF . 1994 . Imagery, action, and young children's spatial orientation: It's not being there that counts, it's what one has in mind. Child Dev. 65 : 1262– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DA , Halloran ES , Cohen RG . 2006 . Grasping movement plans. Psychol. Bull. Rev. 13 : 918– 22 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DA , Marchak F , Barnes J , Vaughan J , Slotta J , Jorgenson M . 1990 . Constraints for action-selection: overhand versus underhand grips. Attention and Performance XIII M Jeannerod 321– 42 Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DA , van Heugten CM , Caldwell GE . 1996 . From cognition to biomechanics and back: the end-state comfort effect and middle-is-faster effect. Acta Psychol. 94 : 59– 85 [Google Scholar]

- Schulz LE , Bonawitz EB . 2007 . Serious fun: preschoolers engage in more exploratory play when evidence is confounded. Dev. Psychol. 43 : 1045– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK , Dutton S . 1979 . Play and training in direct and innovative problem solving. Child Dev. 50 : 830– 36 [Google Scholar]

- Smitsman AW. 1997 . The development of tool use: changing boundaries between organism and environment. Evolving Explanations of Development: Ecological Approaches to Organism-environment Systems C Dent-Read, P Zukow-Goldring 301– 29 Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- Smitsman AW , Cox RFA . 2008 . Perseveration in tool use: a window for understanding the dynamics of the action-selection process. Infancy 13 : 249– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Spies JR , Keen R . 2010 . Picking up tools: cognitive and motor factors in acquiring a new skill Presented at biennial meet Int. Conf. Infant Studies Baltimore, MD: [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen L , Smitsman A , van Leeuwen C . 1994 . Affordances, perceptual complexity, and the development of tool use. J. Exp. Psychol.: Hum. Percept. Perform. 20 : 174– 91 [Google Scholar]

- van Roon D , Van Der Kamp J , Steenbergen B . 2003 . Constraints in children's learning to use spoons. Development of Movement Coordination in Children: Applications in the Field of Ergonomics, Health Sciences and Sport G Savelsbergh, K Davids, J van der Kamp, S Bennett 75– 93 London: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- von Hofsten C . 1980 . Predictive reaching for moving objects by human infants. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 30 : 369– 82 [Google Scholar]

- von Hofsten C , Fazel-Zandy S . 1984 . Development of visually guided hand orientation in reaching. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 38 : 208– 19 [Google Scholar]

- von Hofsten C , Ronnqvist L . 1988 . Preparation for grasping an object: a developmental study. J. Exp. Psychol: Hum. Percept. Perform. 14 : 610– 21 [Google Scholar]

- Want SC , Harris PL . 2001 . Learning from other people's mistakes: causal understanding in learning to use a tool. Child Dev. 72 : 431– 43 [Google Scholar]

Data & Media loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Cognitive development.

Fatima Malik ; Raman Marwaha .

Affiliations

Last Update: April 23, 2023 .

- Definition/Introduction

The concept of childhood is relatively new; in most medieval societies, childhood did not exist. At approximately seven years of age, children were considered little adults with similar expectations for a job, marriage, and legal consequences. Charles Darwin originated ideas of childhood development in his work on the origins of ethology (the scientific study of the evolutionary basis of behavior) and "A Biographical Sketch of an Infant," first published in 1877.

It wasn't until the 20th century that developmental theories emerged. When conceptualizing cognitive development, we cannot ignore the work of Jean Piaget. Piaget suggested that when young infants experience an event, they process new information by balancing assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation is taking in new information and fitting it into previously understood mental schemas. Accommodation is adapting and revising a previously understood mental schema according to the novel information. Piaget divided child development into four stages.

The first stage, Sensorimotor (ages 0 to 2 years of age), is the time when children master two phenomena: causality and object permanence. Infants and toddlers use their sense and motor abilities to manipulate their surroundings and learn about the environment. They understand a cause-and-effect relationship, like shaking a rattle may produce sound and may repeat it or how crying can make the parent(s) rush to give them attention. As the frontal lobe matures and memory develops, children in this age group can imagine what may happen without physically causing an effect; this is the emergence of thought and allows for the planning of actions. Object permanence emerges around six months of age. It is the concept that objects continue to exist even when they are not presently visible.

Second is the "Pre-operational" stage (ages 2 to 7 years), when a child can use mental representations such as symbolic thought and language. Children in this age group learn to imitate and pretend to play. This stage is characterized by egocentrism, i.e., being unable to perceive that others can think differently than themselves, and everything (good or bad) somehow links to the self.

Third is the "Concrete Operational stage" (ages 7 to 11 years), when the child uses logical operations when solving problems, including mastery of conservation and inductive reasoning. Finally, the Formal Operational stage (age 12 years and older) suggests an adolescent can use logical operations with the ability to use abstractions. Adolescents can understand theories, hypothesize, and comprehend abstract ideas like love and justice.

Childhood cognitive development and the Piaget stages are poorly generalizable. For example, conservation may overlap between the Pre-operational and Concrete Operational stages as the child masters conservation in one task and not in another. Similarly, the current understanding is that a child masters the "Theory of Mind" by 4 to 5 years, much earlier than when Piaget suggested that egocentrism resolves. [1]

Stages of Cognitive Development (Problem-Solving and Intelligence)

The word intelligence derives from the Latin "intelligere," meaning to understand or perceive. Problem-solving and cognitive development progress from establishing object permanence, causality, and symbolic thinking with concrete (hands-on) learning to abstract thinking and embedding of implicit (unconscious) to explicit memory development.

Birth to two months: The optical focal length is approximately 10 inches at birth. Infants actively seek stimuli, habituate to the familiar, and respond more vigorously to changing stimuli. The initial responses are more reflexive, like sucking and grasping. The infant can fix and follow a slow horizontal arc and eventually will follow past the midline. Contrasts, colors, and faces are preferred. The infant will distinguish familiar from moderately novel stimuli. As habituation to the faces of caregivers occurs, preferences are developed. The infant will stare momentarily where at the place from where an object has disappeared (lack of object permanence). At this stage, high-pitched voices are preferred.

Two to six months: Children in this age bracket engage in a purposeful sensory exploration of their bodies, staring at their hands and reaching and touching their body parts; this builds the concepts of cause and effect and self-understanding. Sensations and changes outside of themselves are appreciated with less regularity. As motor abilities are mastered, something that happens by chance will be repeated. For example, touching a button may light up the toy, or crying can cause the appearance of the caregiver. Routines are appreciated in this age group.

Six to twelve months: Object permanence emerges in this age group as the toddler looks for objects. A six-month-old will look for partially hidden objects, while a nine-month-old will look for wholly hidden objects and uncover them; this includes engaging in peek-a-boo-type games. Separation and stranger anxiety emerge as the toddler understands that out of sight is not out of mind. As motor abilities advance, sensory exploration of the environment occurs via reaching, inspecting, holding, mouthing, and dropping objects. They learn to manipulate their environment, learning cause and effect by trial and error, like banging two blocks together can produce a sound. Eventually, as Piaget suggested, mental schemas are built, and objects can be used functionally; for example, by intentionally pressing a button to open and reach inside a toy box.

Twelve to eighteen months: Around this time, motor abilities make it easier for the child to walk and reach, grasp, and release. Toys can be explored, made to work, and novel play skills emerge. Gestures and sounds can be imitated. Egocentric pretend play emerges. As object permanence and memory advance, objects can be found after witnessing a series of displacements, and moving objects can be tracked.

Eighteen months to two years: As memory and processing skills advance and frontal lobes mature, outcomes are imagined without so much physical manipulation, and new problem-solving strategies emerge without rehearsal. Thought arises, and there is the ability to plan actions. Object permanence is wholly established, and objects can be searched for by anticipating where they may be without witnessing their displacement. At 18 months, symbolic play expands from just the self; the child may attempt to feed a toy along with themselves, and housework may be imitated.

Two to five years: During this stage, the preschool years, magical and wishful thinking emerges; for example, the sun went home because it was tired. This ability may also give rise to apprehensions with fear of monsters, and having logical solutions may not be enough for reassurance. Perception will dominate over logic, and giving them an imaginary tool, like a monster spray, to help relieve that anxiety may be more helpful. Similarly, conservation and volume concept lacks, and what appears bigger or larger is more. For example, one cookie split into may equal two cookies.

Children in the preschool stage have a poor concept of cause and may think sickness is due to misbehavior. They are egocentric in their approach and may look at situations from only their point of view, offering comfort from a favorite stuffed toy to an upset loved one. At 36 months, a child can understand simple time concepts, identify shapes, compare two items, and count to three. Play becomes more comprehensive. At 48 months, children can count to four, identify four colors and understand opposites.

At five years of age, pre-literacy and numeracy skills further; five-year-old children can count to ten accurately, recites the alphabet by rote, and recognize a few letters. A child also develops hand preference at this age. Play stories become even more detailed between four and five years and may include imaginary scenarios, including imaginary friends. Playing with some game rules and obedience to those rules also establishes during the preschool years. Rules can be absolute.

Six to twelve years: During early school years, scientific reasoning and understanding of physical laws of conservation, including weight and volume, develop. A child can understand multiple points of view and can understand one perspective of a situation. They realize the rules of the game can change with mutual agreement. Basic literacy skills of reading and numbers are mastered initially. Eventually, around third to fourth grade, the emphasis shifts from learning to read to reading to learn and from spelling to composition writing. All these stages need mastery of sustained attention and processing skills, receptive and expressive language, and memory development and recall. The limitation of this stage is an inability to comprehend abstract ideas and reliance on logical answers.

Twelve years and older: During this age, adolescents can exercise logic systematically and scientifically. They can simultaneously apply abstract thinking to solve algebraic problems and multiple logics to reach a scientific solution. It is easier to use these concepts for schoolwork. Later in adolescence and early adulthood, these concepts can also apply to emotional and personal life problems. Magical thinking or following ideals guides decisions more than wisdom. Some may have more influence from religious or moral rules and absolute concepts of right and wrong. Questioning the prevalent code of conduct may cause anxiety or rebellion and eventually lead to the development of personal ethics. Side by side, social cognition, apart from self, also is developing, and concepts of justice, patriarchy, politics, etc. establish. During late teens and early adulthood, thinking about the future, including ideas such as love, commitment, and career goals, become important. [2]

- Issues of Concern

Pediatric and primary care practitioners are in a prime position to monitor the growth and development of children, particularly cognitive development. A lag in cognitive development may alert the provider to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, learning disability, global developmental delay, developmental language disorder, developmental coordination disorder, mild intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, moderate-severe intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, fetal alcohol syndrome (FASD), or vision and auditory disorders.

The most well-known causes of intellectual disability are FASD, Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, other genetic or chromosomal problems, lead or other toxicities, and environmental influences such as poverty, malnutrition, abuse, and neglect. Prenatal causes of intellectual disability include infection, toxins and teratogens, congenital hypothyroidism, inborn errors of metabolism, and genetic abnormalities. Fetal alcohol syndrome is the most common preventable cause of intellectual disability. Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause, and Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause. First-tier tests recommended for intellectual disability are chromosomal microarray and Fragile X testing.

Clinical concerns can arise in areas of visual analysis, proprioception, motor control, memory storage and recall, attention span and sequencing, and deficits in receptive or expressive language. Early recognition of intellectual disability leads to earlier diagnosis and intervention, showing promising results in improved cognition. Besides what is best for children and families, early intervention saves overall economic expenditure on disabilities. Thus, surveillance alone is inadequate; active screening for developmental delay should be an integral part of medical practice. [3] Some commonly used measures for screening are the Ages and Stages Questionnaire and the Survey of Well-being of Young Children. If the results of surveillance and screening are concerning, watchful waiting is inadequate, and a referral is necessary for early intervention.

Intellectual disability is defined when there is a concern for intellectual and adaptive functioning. Usually, on standardized measures, this means a score less than two standard deviations below the mean, which is 100 for most measures. Standardized tests used to measure intellectual function include the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI), and the Stanford-Binet test. One standardized test for adaptive functioning is the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale.

A learning disability should be suspected when the intelligence score is within the average range, but a significant discrepancy in achievement scores exists, or a child does not respond to evidence-based interventions. Evidence-based interventions include increasing instruction time and specialized instruction by trained personnel in deficit areas.

- Clinical Significance

Early intervention during the "critical period" in development has shown promising results. [4] Thus clinicians must take the lead to diagnose, treat, and establish resources for early intervention to provide optimal health opportunities to our children. Early intervention services should be provided in two areas; biological risk/disabilities and environmental risk.

Pediatric and primary care practitioners should understand The Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) and other federal policies. Early intervention laws give entitlement to services from birth through early intervention home-based service, the Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) from birth to 3 years of age, and individualized education plans for ages 3 to 21 years. The goal is to minimize or prevent disability by accommodating children with intellectual disabilities or changing the curriculum to meet the individualized needs of the child. This plan should be based on an interprofessional assessment to understand the child's needs.

Thus, clinicians should partner with social workers, psychologists, or psychiatrists for thorough evaluations, lawyers to explore legal support and advocacy for services, therapists, early intervention providers, and schools to plan individualized goals and monitor progress.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Fatima Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Raman Marwaha declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Malik F, Marwaha R. Cognitive Development. [Updated 2023 Apr 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Darwin's "Natural Science of Babies". [J Hist Neurosci. 2010] Darwin's "Natural Science of Babies". Lorch M, Hellal P. J Hist Neurosci. 2010 Apr 8; 19(2):140-57.

- Scientific cousins: the relationship between Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. [Am Psychol. 2009] Scientific cousins: the relationship between Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. Fancher RE. Am Psychol. 2009 Feb-Mar; 64(2):84-92.

- Darwin's legacy to comparative psychology and ethology. [Am Psychol. 2009] Darwin's legacy to comparative psychology and ethology. Burghardt GM. Am Psychol. 2009 Feb-Mar; 64(2):102-10.

- Review Evolutionary ethics from Darwin to Moore. [Hist Philos Life Sci. 2003] Review Evolutionary ethics from Darwin to Moore. Allhoff F. Hist Philos Life Sci. 2003; 25(1):51-79.

- Review Entomological reactions to Darwin's theory in the nineteenth century. [Annu Rev Entomol. 2008] Review Entomological reactions to Darwin's theory in the nineteenth century. Kritsky G. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008; 53:345-60.

Recent Activity

- Cognitive Development - StatPearls Cognitive Development - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Cognitive Development Theory: What Are the Stages?

Sensorimotor stage, preoperational stage, concrete operational stage, formal operational stage.

Cognitive development is the process by which we come to acquire, understand, organize, and learn to use information in various ways. Cognitive development helps a child obtain the skills needed to live a productive life and function as an independent adult.

The late Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget was a major figure in the study of cognitive development theory in children. He believed that it occurs in four stages—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

This article discusses Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, including important concepts and principles.

FatCamera / Getty Images

History of Cognitive Development

During the 1920s, the psychologist Jean Piaget was given the task of translating English intelligence tests into French. During this process, he observed that children think differently than adults do and have a different view of the world. He began to study children from birth through the teenage years—observing children who were too young to talk, and interviewing older children while he also observed their development.

Piaget published his theory of cognitive development in 1936. This theory is based on the idea that a child’s intelligence changes throughout childhood and cognitive skills—including memory, attention, thinking, problem-solving, logical reasoning, reading, listening, and more—are learned as a child grows and interacts with their environment.

Stages of Cognitive Development

Piaget’s theory suggests that cognitive development occurs in four stages as a child ages. These stages are always completed in order, but last longer for some children than others. Each stage builds on the skills learned in the previous stage.

The four stages of cognitive development include:

- Sensorimotor

- Preoperational

- Concrete operational

- Formal operational

The sensorimotor stage begins at birth and lasts until 18 to 24 months of age. During the sensorimotor stage, children are physically exploring their environment and absorbing information through their senses of smell, sight, touch, taste, and sound.

The most important skill gained in the sensorimotor stage is object permanence, which means that the child knows that an object still exists even when they can't see it anymore. For example, if a toy is covered up by a blanket, the child will know the toy is still there and will look for it. Without this skill, the child thinks that the toy has simply disappeared.

Language skills also begin to develop during the sensorimotor stage.

Activities to Try During the Sensorimotor Stage

Appropriate activities to do during the sensorimotor stage include:

- Playing peek-a-boo

- Reading books

- Providing toys with a variety of textures

- Singing songs

- Playing with musical instruments

- Rolling a ball back and forth

The preoperational stage of Piaget's theory of cognitive development occurs between ages 2 and 7 years. Early on in this stage, children learn the skill of symbolic representation. This means that an object or word can stand for something else. For example, a child might play "house" with a cardboard box.

At this stage, children assume that other people see the world and experience emotions the same way they do, and their main focus is on themselves. This is called egocentrism .

Centrism is another characteristic of the preoperational stage. This means that a child is only able to focus on one aspect of a problem or situation. For example, a child might become upset that a friend has more pieces of candy than they do, even if their pieces are bigger.

During this stage, children will often play next to each other—called parallel play—but not with each other. They also believe that inanimate objects, such as toys, have human lives and feelings.

Activities to Try During the Preoperational Stage

Appropriate activities to do during the preoperational stage include:

- Playing "house" or "school"

- Building a fort

- Playing with Play-Doh

- Building with blocks

- Playing charades

The concrete operational stage occurs between the ages of 7 and 11 years. During this stage, a child develops the ability to think logically and problem-solve but can only apply these skills to objects they can physically see—things that are "concrete."

Six main concrete operations develop in this stage. These include:

- Conservation : This skill means that a child understands that the amount of something or the number of a particular object stays the same, even when it looks different. For example, a cup of milk in a tall glass looks different than the same amount of milk in a short glass—but the amount did not change.

- Classification : This skill is the ability to sort items by specific classes, such as color, shape, or size.

- Seriation : This skill involves arranging objects in a series, or a logical order. For example, the child could arrange blocks in order from smallest to largest.

- Reversibility : This skill is the understanding that a process can be reversed. For example, a balloon can be blown up with air and then deflated back to the way it started.

- Decentering : This skill allows a child to focus on more than one aspect of a problem or situation at the same time. For example, two candy bars might look the same on the outside, but the child knows that they have different flavors on the inside.

- Transitivity : This skill provides an understanding of how things relate to each other. For example, if John is older than Susan, and Susan is older than Joey, then John is older than Joey.

Activities to Try During the Concrete Operational Stage

Appropriate activities to do during the concrete operational stage include:

- Using measuring cups (for example, demonstrate how one cup of water fills two half-cups)

- Solving simple logic problems

- Practicing basic math

- Doing crossword puzzles

- Playing board games

The last stage in Piaget's theory of cognitive development occurs during the teenage years into adulthood. During this stage, a person learns abstract thinking and hypothetical problem-solving skills.

Deductive reasoning—or the ability to make a conclusion based on information gained from a person's environment—is also learned in this stage. This means, for example, that a person can identify the differences between dogs of various breeds, instead of putting them all in a general category of "dogs."

Activities to Try During the Formal Operational Stage

Appropriate activities to do during the formal operational stage include:

- Learning to cook

- Solving crossword and logic puzzles

- Exploring hobbies

- Playing a musical instrument

Piaget's theory of cognitive development is based on the belief that a child gains thinking skills in four stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational. These stages roughly correspond to specific ages, from birth to adulthood. Children progress through these stages at different paces, but according to Piaget, they are always completed in order.

National Library of Medicine. Cognitive testing . MedlinePlus.

Oklahoma State University. Cognitive development: The theory of Jean Piaget .

SUNY Cortland. Sensorimotor stage .

Marwaha S, Goswami M, Vashist B. Prevalence of principles of Piaget’s theory among 4-7-year-old children and their correlation with IQ . J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):ZC111-ZC115. doi:10.7860%2FJCDR%2F2017%2F28435.10513

Börnert-Ringleb M, Wilbert J. The association of strategy use and concrete-operational thinking in primary school . Front Educ. 2018;0. doi:10.3389/feduc.2018.00038

By Aubrey Bailey, PT, DPT, CHT Dr, Bailey is a Virginia-based physical therapist and professor of anatomy and physiology with over a decade of experience.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The development of problem solving in young children: a critical cognitive skill

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22904, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 20822435

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130730

Problem solving is a signature attribute of adult humans, but we need to understand how this develops in children. Tool use is proposed as an ideal way to study problem solving in children less than 3 years of age because overt manual action can reveal how the child plans to achieve a goal. Motor errors are as informative as successful actions. Research is reviewed on intentional actions, beginning with block play and progressing to picking up a spoon in different orientations, and finally retrieving objects with rakes and from inside tubes. Behavioral and kinematic measures of motor action are combined to show different facets of skill acquisition and mastery. We need to design environments that encourage and enhance problem solving from a young age. One goal of this review is to excite interest and spur new research on the beginnings of problem solving and its elaboration during development.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Action planning in young children's tool use. Cox RF, Smitsman AW. Cox RF, et al. Dev Sci. 2006 Nov;9(6):628-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00541.x. Dev Sci. 2006. PMID: 17059460

- Children's questions: a mechanism for cognitive development. Chouinard MM. Chouinard MM. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2007;72(1):vii-ix, 1-112; discussion 113-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2007.00412.x. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2007. PMID: 17394580

- Longitudinal mediators of social problem solving in spina bifida and typical development. Landry SH, Taylor HB, Swank PR, Barnes M, Juranek J. Landry SH, et al. Rehabil Psychol. 2013 May;58(2):196-205. doi: 10.1037/a0032500. Rehabil Psychol. 2013. PMID: 23713730

- Play, creativity, and adaptive functioning: implications for play interventions. Russ SW. Russ SW. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998 Dec;27(4):469-80. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2704_11. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998. PMID: 9866084 Review.

- From play to problem solving to Common Core: The development of fluid reasoning. Prince P. Prince P. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2017 Jul-Sep;6(3):224-227. doi: 10.1080/21622965.2017.1317487. Epub 2017 May 12. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2017. PMID: 28498010 Review.

- Validation of new tablet-based problem-solving tasks in primary school students. Schäfer J, Reuter T, Leuchter M, Karbach J. Schäfer J, et al. PLoS One. 2024 Aug 29;19(8):e0309718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0309718. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 39208270 Free PMC article.

- Parenting Influences on Frontal Lobe Gray Matter and Preterm Toddlers' Problem-Solving Skills. Muñoz JS, Giles ME, Vaughn KA, Wang Y, Landry SH, Bick JR, DeMaster DM. Muñoz JS, et al. Children (Basel). 2024 Feb 6;11(2):206. doi: 10.3390/children11020206. Children (Basel). 2024. PMID: 38397318 Free PMC article.

- Lifelong learning of cognitive styles for physical problem-solving: The effect of embodied experience. Allen KR, Smith KA, Bird LA, Tenenbaum JB, Makin TR, Cowie D. Allen KR, et al. Psychon Bull Rev. 2024 Jun;31(3):1364-1375. doi: 10.3758/s13423-023-02400-4. Epub 2023 Dec 4. Psychon Bull Rev. 2024. PMID: 38049575 Free PMC article.

- Young children spontaneously invent three different types of associative tool use behaviour. Reindl E, Tennie C, Apperly IA, Lugosi Z, Beck SR. Reindl E, et al. Evol Hum Sci. 2022 Feb 2;4:e5. doi: 10.1017/ehs.2022.4. eCollection 2022. Evol Hum Sci. 2022. PMID: 37588934 Free PMC article.

- Tool mastering today - an interdisciplinary perspective. Schubotz RI, Ebel SJ, Elsner B, Weiss PH, Wörgötter F. Schubotz RI, et al. Front Psychol. 2023 Jun 16;14:1191792. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1191792. eCollection 2023. Front Psychol. 2023. PMID: 37397285 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- R37 HD27714/HD/NICHD NIH HHS/United States

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ingenta plc

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- MedlinePlus Consumer Health Information

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Vygotsky’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Sociocultural Theory

The work of Lev Vygotsky (1934, 1978) has become the foundation of much research and theory in cognitive development over the past several decades, particularly what has become known as sociocultural theory.

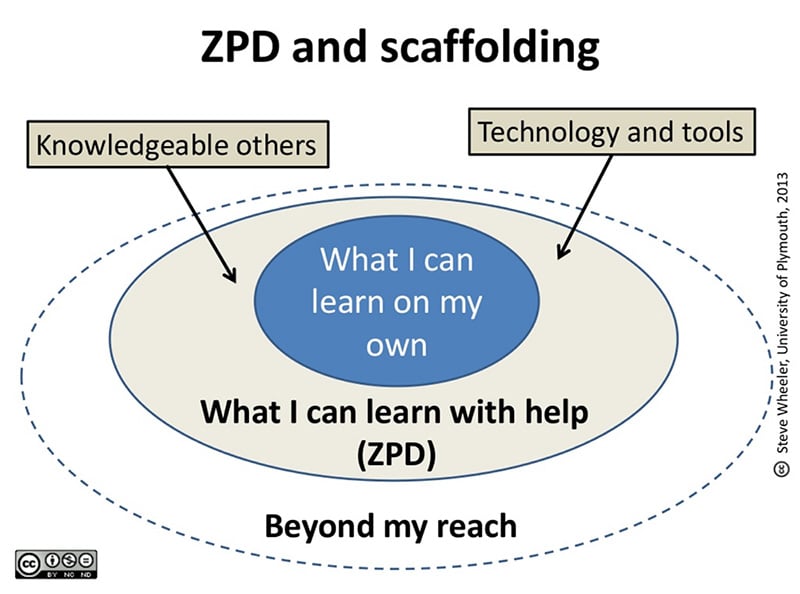

Vygotsky’s theory comprises concepts such as culture-specific tools, private speech, and the zone of proximal development.

Vygotsky believed cognitive development is influenced by cultural and social factors. He emphasized the role of social interaction in the development of mental abilities e.g., speech and reasoning in children.

Vygotsky strongly believed that community plays a central role in the process of “making meaning.”

Cognitive development is a socially mediated process in which children acquire cultural values, beliefs, and problem-solving strategies through collaborative dialogues with more knowledgeable members of society.

The more knowledgeable other (MKO) is someone who has a higher level of ability or greater understanding than the learner regarding a particular task, process, or concept.

The MKO can be a teacher, parent, coach, or even a peer who provides guidance and modeling to enable the child to learn skills within their zone of proximal development (the gap between what a child can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance).

The interactions with more knowledgeable others significantly increase not only the quantity of information and the number of skills a child develops, but also affects the development of higher-order mental functions such as formal reasoning. Vygotsky argued that higher mental abilities could only develop through interaction with more advanced others.

According to Vygotsky, adults in society foster children’s cognitive development by engaging them in challenging and meaningful activities. Adults convey to children how their culture interprets and responds to the world.

They show the meaning they attach to objects, events, and experiences. They provide the child with what to think (the knowledge) and how to think (the processes, the tools to think with).

Vygotsky’s theory encourages collaborative and cooperative learning between children and teachers or peers. Scaffolding and reciprocal teaching are effective educational strategies based on Vygotsky’s ideas.

Scaffolding involves the teacher providing support structures to help students master skills just beyond their current level. In reciprocal teaching, teachers and students take turns leading discussions using strategies like summarizing and clarifying. Both scaffolding and reciprocal teaching emphasize the shared construction of knowledge, in line with Vygotsky’s views.

Vygotsky highlighted the importance of language in cognitive development. Inner speech is used for mental reasoning, and external speech is used to converse with others.

Initially, these operations occur separately. Indeed, before age two, a child employs words socially; they possess no internal language.

Once thought and language merge, however, the social language is internalized and assists the child with their reasoning. Thus, the social environment is ingrained within the child’s learning.

Effects of Culture

Vygotsky’s theory emphasizes individuals’ active role in their cognitive development, highlighting the interplay between innate abilities, social interaction, and cultural tools.

Vygotsky posited that people aren’t passive recipients of knowledge but actively interact with their environment. This interaction forms the basis of cognitive development.

Infants are born with basic abilities for intellectual development, called “elementary mental functions.” These include attention, sensation, perception, and memory.

Through interaction within the sociocultural environment, elementary functions develop into more sophisticated “higher mental functions.”

Higher mental functions are advanced cognitive processes that develop through social interaction and cultural influences. They are distinct from the basic, innate elementary mental functions.

Unlike elementary functions (like basic attention or memory), higher functions are:

- Conscious awareness : The individual is aware of these processes.

- Voluntary control : They can be deliberately used and controlled.

- Mediated : They involve the use of cultural tools or signs (like language).

- Social in origin : They develop through social interaction.

Examples include language and communication, logical reasoning, problem-solving, planning, attention control, self-regulation, and metacognition.

Vygotsky posited that higher mental functions are not innate but develop through social interaction and the internalization of cultural tools.

Tools of Intellectual Adaptation

Cultural tools are methods of thinking and problem-solving strategies that children internalize through social interactions with more knowledgeable members of society.

These tools, such as language, counting systems, mnemonic techniques, and art forms, shape the way individuals think, problem-solve, and interact with the world.

Tools of intellectual adaptation is Vygotsky’s term for methods of thinking and problem-solving strategies that children internalize through social interactions with the more knowledgeable members of society.

Cultural tools, particularly language, influence the development of higher-order thinking skills.

Other tools include writing systems, number systems, mnemonic techniques, works of art, diagrams, maps, and drawings.

These tools are products of sociocultural evolution, passed down and transformed across generations.

Each culture provides its children with tools of intellectual adaptation that allow them to use basic mental functions more effectively.

These tools, along with social interaction, contribute to the development of higher mental functions through a process of internalization.

This historical and cultural embeddedness means that tools carry within them the accumulated knowledge and practices of a particular community.

For example, biological factors limit memory in young children. However, culture determines the type of memory strategy we develop.

For example, in Western culture, children learn note-taking to aid memory, but in pre-literate societies, other strategies must be developed, such as tying knots in a string to remember, carrying pebbles, or repeating the names of ancestors until large numbers can be repeated.

Vygotsky, therefore, sees cognitive functions, even those carried out alone, as affected by the beliefs, values, and tools of intellectual adaptation of the culture in which a person develops and, therefore, socio-culturally determined.

Therefore, intellectual adaptation tools vary from culture to culture – as in the memory example.