- National Science Foundation (NSF) Templates

- Sponsored Research and Programs

- Proposal Preparation

NSF Career Program

Please note that the eligibility requirements specified in the solicitation remain unchanged, and proposers must meet all of the eligibility requirements as of the original deadline of July 26, 2023. The Departmental Letter that must be submitted by the Department Chair (or equivalent) must use July 26, 2023 to determine eligibility, regardless of whether the CAREER proposal is submitted before, on, or after July 26, 2023. An untenured assistant professor on July 26, 2023 is eligible to submit a CAREER proposal even if the Principal Investigator is tenured/promoted in the fall. A new faculty member who starts on July 27, 2023 or later is not eligible to submit a CAREER proposal this year.

Solicitation: NSF 22-586 - All NSF CAREER proposals for all directorates are due by July 26, 2023. However, due to the high number of proposal submissions, IIT’s internal deadline is July 20, 2023 . PI's: Click here for additional information regarding CAREER Proposal Submission Timelines. Note: Illinois Tech has completed and maintains all institutional registration information.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for the Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program for Submission in Years 2022 - 2026 (2022-2026)

NSF CAREER Administrative Notes | NSF CAREER Administrative Video

NSF Grant Proposal Guide (23-1)

Current Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (PAPPG) for preparing proposals to be submitted to NSF.

NSF Checklist

It is important that all proposals conform to the proposal preparation and submission instructions specified in PAPPG and solicitation guidelines. This checklist is not intended to be all inclusive. It is meant to highlight certain critical items so they will not be overlooked when the proposal is prepared.

NSF Biographical Sketch

- NSF Requirements (webinar) to use an NSF-approved format for both the biographical sketch and current and pending support documents

A biographical sketch (limited to two pages) is required for each individual identified as senior personnel and must be uploaded as a pdf document for each individual. Do not submit any personal information in the biographical sketch. Template

Note: NSF now requires the use of the NSF-approved format for the preparation of the Biographical Sketch and Current and Pending Support via SciENcv . Each PI will need to use the SciENcv to prepare these. SciEncv will create a PDF to submit.

- YouTube Video: SciENcv tutorial

- SciENcv - Creating Biosketches Instructions

- Using SciENcv FAQ's

Current and Pending Support

- NSF current & pending support format

The support requested or available from all other sources (Federal, State, Industry, gifts, etc.).

Note: NSF now requires the use of the NSF-approved format for the preparation of the Biographical Sketch and Current and Pending via SciENcv . Each PI will need to use the SciENcv to prepare their Current and Pending.

Please review this FAQ for what needs to be reported on a current and pending. Here are some highlights:

Only an NSF approved format through SCiENcv for current and pending support can be used. Creating a PDF from a Word document will be not compliant with NSF policy.

An item or service given with the expectation of an associated time commitment which is not a gift and is instead an in-kind contribution and must be reported to NSF. A gift by definition is given without expectation of anything in return.

- In-kind contributions which are not intended for use on the project/proposal being proposed to NSF and have no associated time commitment, the information is not required to be reported. However, in-kind contributions with no associated time commitment that are intended for use on the project/proposal being proposed to NSF must be included as part of the Facilities, Equipment, and Other Resources section.

- Organizational start-up packages provided to the individual from the proposing organization are not required to be reported. Start-up packages from other than the proposing organization must be reported. Faculty academic year salary is not considered current and pending support in this context.

Collaborators and Other Affiliations

The information collaborators and other affiliations must be separately provided for each individual identified as senior project personnel. Click here for more information and template.

Collaboration Letter Template

NSF requires the use of a template for identifying collaborators and other affiliations.

Data Management Plan

Plans for data management and sharing of the products of research. Proposals must include a document of no more than two pages uploaded under “Data Management Plan” in the supplementary documentation section of FastLane. Sample

Please see the NSF Proposal & Award Policies & Preparation Guide ( PAPPAG ) for additional guidance.

You may also find additional guidance on how to manage your research data and additional information in the Illinois Tech Library Guides.

Postdoctoral Mentoring Plan

Each proposal that requests funding to support postdoctoral researchers must upload under “Mentoring Plan” in the supplementary documentation section of FastLane, a description of the mentoring activities that will be provided for such individuals. See the PAPPG for additional guidance. Sample

Project Reports

Annual project reports are required for all standard and continuing grants and cooperative agreements. Final reports are required for all standard and continuing grants, cooperative agreements and fellowships. Interim project reports are not required and are used to update the progress of a project any time during or before the award period expires. You can find additional information here .

Other Resources

Grants.gov Proposal Processing in Research.gov

Research.gov About Proposal Preparation and Submission

Research.gov About Supplemental Funding Request Preparation and Submission

Research.gov Proposal Preparation Demo Site ( You will be prompted to sign into Research.gov if you are not already signed in)

Resources for LaTeX Users: https://github.com/nsf-open/nsf-proposal-latex-samples

Learn more...

- Utility Menu

FAS Research Administration Services

- National Science Foundation (NSF) Resources

RAS has compiled a set of guidelines, templates, and tools to facilitate the development of NSF proposals. The templates have been reviewed and updated, if necessary, to reflect changes and clarifications described in NSF 24-1, the Proposal & Award Policies & Procedures Guide (PAPPG), effective for proposals submitted on or due on or after May 20, 2024.

To view the full 24-1 PAPPG, click the link in the Related Links section.

NSF Resources

Doctoral dissertation research improvement grant checklist, using sciencv for nsf biosketches and current and pending support - frequently asked questions, nsf current and pending support, facilities and resources - sample language for describing core facilities, nsf collaborators and other affiliations.

NSF requires the use of an Excel template (click here for a copy) for reporting the Collaborators and Other Affiliations (COA) information of all Senior Personnel identified in proposal submissions. The Excel template has been developed to be fillable, however, the content and format requirements must not be altered by as this will create printing and viewing errors.

... Read more about NSF Collaborators and Other Affiliations

NSF Biographical Sketch

A biographical sketch is required for each individual identified as Senior Personnel on a NSF proposal. Click the link above for content guidelines and the new format requirements for this section effective May 20, 2024.

NSF Facilities, Equipment and Other Resources Template

Proposers must include a description of the internal and external resources (both physical and personnel) that the organization and its collaborators will provide to the project, should it be funded.

NSF Results from Prior NSF Support Template

If any PI or co-PI identified on the project has received NSF funding in the past five years, information on the award(s) is required. Each PI and co-PI who has received more than one award (excluding amendments) must report on the award most closely related to the proposal.

NSF Mentoring Plan Template

Each NSF proposal that requests funding to support postdoctoral researchers and/or graduate students must include, as a supplementary document, a description of the mentoring activities that will be provided for such individuals.

Standard NSF Grant Checklist

A sample planning checklist for the preparation of a NSF research grant.

Sample Proposal Library

This proposal library contains recently successful grant proposals from FAS and SEAS applicants available for use by request from FAS and SEAS faculty and principal investigators.

Broader Impacts Resources

This resource provides information on programs and resources in and around Harvard that FAS and SEAS faculty can leverage to demonstrate the potential for a project to benefit society or advance desired societal outcomes.

NSF Data Management Plan

NSF Guide and template for creating a data management plan

- Getting Started

- Sample Proposals

- Diversity Resources for Grant Proposals

- Broader Impacts

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Resources

- Budget Preparation

- Review & Submission

- Award Setup

Related Links

NSF Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (effective May 20, 2024)

NSF Merit Review Process

Research.gov online portal

Why You Should Volunteer to Serve As An NSF Reviewer

- Skip to main navigation

- Skip to main content

University Research Administration

- National Science Foundation (NSF) Proposal Toolkit

- International Research Collaborations

- University of Chicago CRA Study Group

- Faculty Proposal Development Guide

- Finding Funding

- Limited Opportunities (InfoReady)

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Proposal Toolkit

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Training, Career Development and Fellowship Proposal Toolkit

- Department of Energy (DOE) Proposal Toolkit

- Office of Justice Programs (OJP) Proposal Toolkit

- Department of Defense (DOD) Proposal Toolkit

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Proposal Toolkit

- USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Proposal Toolkit

- Small Business Association (SBA) and SBIR/STTR Proposal Toolkit

- Department of Education (ED) Proposal Toolkit

- Institute of Education Sciences (IES) Proposal Toolkit

- Institute of Museum and Library Sciences (IMLS) Proposal Toolkit

- National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Proposal Toolkit

- proposalCENTRAL Non-Federal Agencies Toolkit

- Federal Contracts

- Grants & Cooperative Agreements

- SciENcv Guide

- ORCID Guide

- Proposal Budget Development

- Quick Reference Fact Sheet

- Roles and Responsibilities Matrix

- URA Review and Endorsement

- Agency Electronic Submissions and/or URA Submissions

- eRA Commons

- Sponsored Development Services

- Sponsored Program Services

- Research Compliance & Training

- Policies & Compliance

Quick Links

- URA Intranet

- Conflict of Interest – Conflict of Commitment

- Finding Funding – Pivot

- PI Eligibility

- URA Annual Report

- Forms, Templates, & Sponsor Resources (URA Intranet)

National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent Federal agency created by Congress in 1950 to “promote the progress of science; [and] to advance the national health, prosperity, and welfare” by supporting research and education in all fields of science and engineering. An overview of Understanding NSF Research is available to provide descriptions of areas of research interests. A description for types of proposals provides guidance on the variety of proposals accepted, in addition to the standard research proposal.

Funding opportunities are provided through the NSF website; additional information about special requirements of individual NSF programs may be obtained from the appropriate Foundation program office. Information about most program deadlines and target dates for proposals are available on the NSF website. Program deadline and target date information also appears in individual funding opportunities and on relevant NSF Divisional/Office websites.

NSF Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (PAPPG)

The National Science Foundation (NSF) requires electronic submission for all grant proposals via Research.gov . The NSF Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (PAPPG) is the primary reference guidance for proposal development. Part I sets forth NSF’s proposal preparation and submission guidelines. Part II of the NSF PAPPG sets forth NSF policies and procedures regarding the award, administration, and monitoring of the Foundation’s grants and cooperative agreements. Frequently asked questions on proposal preparation and award management are also available for quick reference.

The new PAPPG Guide is effective for proposals submissions on or after May 20th, 2024.

Merit Review and Broader Impacts

All proposals must address the intellectual merit and broader impacts review criteria specified in the program announcement. If the review criteria are not addressed the proposal will NOT be reviewed.

What is Merit Review ?

Through its merit review process , the National Science Foundation (NSF) ensures that proposals submitted are reviewed in a fair, competitive, transparent, and in-depth manner. The merit review process is described in detail in Part I of the NSF Proposal & Award Policies & Procedures Guide (PAPPG) which provides guidance for the preparation and submission of proposals to NSF.

What are broader impacts ?

The broader impacts of a research project are those components that, beyond the advancement of knowledge, have the potential to benefit society and contribute to achievement of specific desired societal outcomes. The National Science Foundation (NSF) requires proposals to address the broader impacts in addition to the intellectual merit of the project.

- NSF Five Tips for Your Broader Impact Statement

- ARIS Broader Impacts (and other) Toolkit

Proposal Formatting, Requirements, and Sections

Nsf proposal checklist.

Note that some NSF program solicitations modify standard NSF proposal preparation guidelines, and, in such cases, the guidelines provided in the solicitation must be followed. The requirements specified for each type of proposal are compliance checked by NSF electronic systems prior to submission. Proposers are strongly advised to review Chapter II.D (for Research proposals) and the applicable sections of Chapter II.F. relevant to the other types of proposals being developed prior to submission. NSF will not accept or will return without review proposals that are not consistent with these instructions.

Sections of the Proposal

The sections described below represent the body of a research proposal submitted to NSF. Failure to submit the required sections will result in the proposal not being accepted, or being returned without review. See Chapter IV.B for additional information. A full research proposal must contain the following sections. Note: the PAPPG may use different naming conventions, and sections may appear in a different order than in Research.gov, however, the content is the same.

- Cover Sheet

- Project Summary

- Project Description

- References Cited

- Budget and Budget Justification

- Biographical Sketches

- Collaborators and Other Affilations Information

- Current and Pending Support

- Synergistic Activities Template

- Facilities, Equipment, and Other Resources

- Data Management Plan

- Postdoctoral Research Plan

- Formatting Requirements

- Letters of Collaboration

- Single Copy Documents

- Defining Categories of Personnel

- Special Information and Supplementary Documentation

- Special Processing Instructions

- NSF Safe and Inclusive Working Environment Plans for Off-Campus or Off-Site Research

Special Programs

Faculty early career program (career).

The Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program is a Foundation-wide activity that offers the National Science Foundation's most prestigious awards in support of early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and to lead advances in the mission of their department or organization. Activities pursued by early-career faculty should build a firm foundation for a lifetime of leadership in integrating education and research. NSF encourages submission of CAREER proposals from early-career faculty at all CAREER-eligible organizations and especially encourages women, members of underrepresented minority groups, and persons with disabilities to apply.

- CAREER Program Information

- NSF CAREER Contacts

- FAQs for CAREER Program for Submission in Years 2020-2026

- View All CAREER Awards

EArly-concept Grants for Exploratory Research (EAGER)

The EAGER funding mechanism may be used to support exploratory work in its early stages on untested, but potentially transformative, research ideas or approaches. This work may be considered especially "high risk-high payoff" in the sense that it, for example, involves radically different approaches, applies new expertise, or engages novel disciplinary or interdisciplinary perspectives. These exploratory proposals may also be submitted directly to an NSF program, but the EAGER mechanism should not be used for projects that are appropriate for submission as “regular” (i.e., non-EAGER) NSF proposals.

- Transformative Research

- Interdisciplinary Research

- View All EAGER Awards

Rapid Response Research (RAPID)

In addition to standard research proposals, NSF also has the Rapid Response Research (RAPID) proposal type. This type of proposal is used when there is a severe urgency with regard to availability of, or access to, data, facilities or specialized equipment, including quick-response research on natural or anthropogenic disasters and similar unanticipated events. See PAPPG Chapter II.E.2 for additional information on RAPID proposals.

RAPID proposals are NOT for: (1) Projects appropriate for submission as regular NSF proposals. (2) Events that are unanticipated due to lack of awareness of timelines; or (3) Collection of only non-perishable data.

RAPID is a type of proposal used when there is a severe urgency with regard to availability of or access to, data, facilities or specialized equipment, including quick-response research on natural or anthropogenic events and similar unanticipated occurrences.

RAPID proposals are NOT for: projects that are appropriate for submission as "regular" NSF proposals; events that are unanticipated due to lack of awareness of timelines; or collection of only non-perishable data.

PIs are advised that they must submit a Concept Outline prior to submission of a RAPID proposal. This will aid in determining the appropriateness of the work for consideration under this type of proposal. Concept Outlines can be submitted either by email to a cognizant Program Officer or via ProSPCT . An NSF funding opportunity that includes RAPID proposals will provide specific guidance on submission of Concept Outlines using either email or via ProSPCT.

Research in Undergraduate Institutions (RUI) and Research Opportunity Awards (ROA)

The Research in Undergraduate Institutions (RUI) and Research Opportunity Awards (ROA) funding opportunities support research by faculty members at predominantly undergraduate institutions (PUIs). RUI proposals support PUI faculty in research that engages them in their professional field(s), builds capacity for research at their home institution, and supports the integration of research and undergraduate education. ROAs similarly support PUI faculty research, but these awards typically allow faculty to work as visiting scientists at research-intensive organizations where they collaborate with other NSF-supported investigators.

Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU)

The Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program supports active research participation by undergraduate students in any of the areas of research funded by the National Science Foundation. REU projects involve students in meaningful ways in ongoing research programs or in research projects specifically designed for the REU program. This solicitation features two mechanisms for support of student research: (1) REU Sites are based on independent proposals to initiate and conduct projects that engage a number of students in research. REU Sites may be based in a single discipline or academic department or may offer interdisciplinary or multi-department research opportunities with a coherent intellectual theme. Proposals with an international dimension are welcome. (2) REU Supplements may be included as a component of proposals for new or renewal NSF grants or cooperative agreements or may be requested for ongoing NSF-funded research projects.

Proposal Writing and Other Resources

- NSF Grants Writing and Management Workshop

- NSF Guide to Proposal Writing

- NSF Project Evaluation Handbook

- Learn about Interdisciplinary Research

- Guidelines for Education Research and Development

COI Disclosures

Standard and Non-Standard COI Disclosures for NSF

The University of Chicago's Revised Conflict of Interest Policy requires that all individuals with the designation of faculty, or other academic appointment, annually file a Conflict of interest-Conflict of Commitment Disclosure . Furthermore, any individual that is engaged in the design, conduct or reporting of research, or is considered "key personnel" must comply with the policy. This is a university-wide policy and applies regardless of whether the faculty or academic is engaged in research, or receives external research funding, and regardless of whether they have a full time or part time appointment.

When OS or CPS documents are required at proposal stage or Just-in-Time (JIT) stage, the URA Pre-Award Specialist with send an Ancillary Review to the URA COI team to identify any additional items that need to be reported for key personnel. The URA COI team will complete the Ancillary Review and inform the key personnel, Administrative Contact, and URA Pre-Award Specialist about what involvements and activities should be included.

For this process of developing or updating the Other Support (OS) or Current and Pending Support (CPS) documentation for a faculty member, the question arises on where to include outside faculty appointments, ownership in an external business, or other non-standard or unusual circumstances identified by the URA COI team.

For NSF, with the mandatory required use of SciENcv for CPS documents, when asked in a webinar Jean Feldman (Head, Policy Office https://nsfpolicyoutreach.com/resource-center/ ) at NSF indicated these types of outside of the norm activities should be disclosed in the Collaborators and Other Affiliations (COA) document required for proposal submission. For the full webinar follow this link: https://nsfpolicyoutreach.com/resources/nsf-implementation-of-the-common-forms-for-the-biographical-sketch-and-current-and-pending-other-support/

- NSF requires use of their template for the COA document: https://new.nsf.gov/funding/senior-personnel-documents#collaborators-and-other-affiliations-2b3

- Also see the NSF disclosure table (updating May 20, 2024): https://www.nsf.gov/bfa/dias/policy/disclosures_table.jsp

| Susan Finger Updated April 2015

The original version of this advice was written in the late 1980s. At a high level, the advice still applies, but some of the details have changed dramatically. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

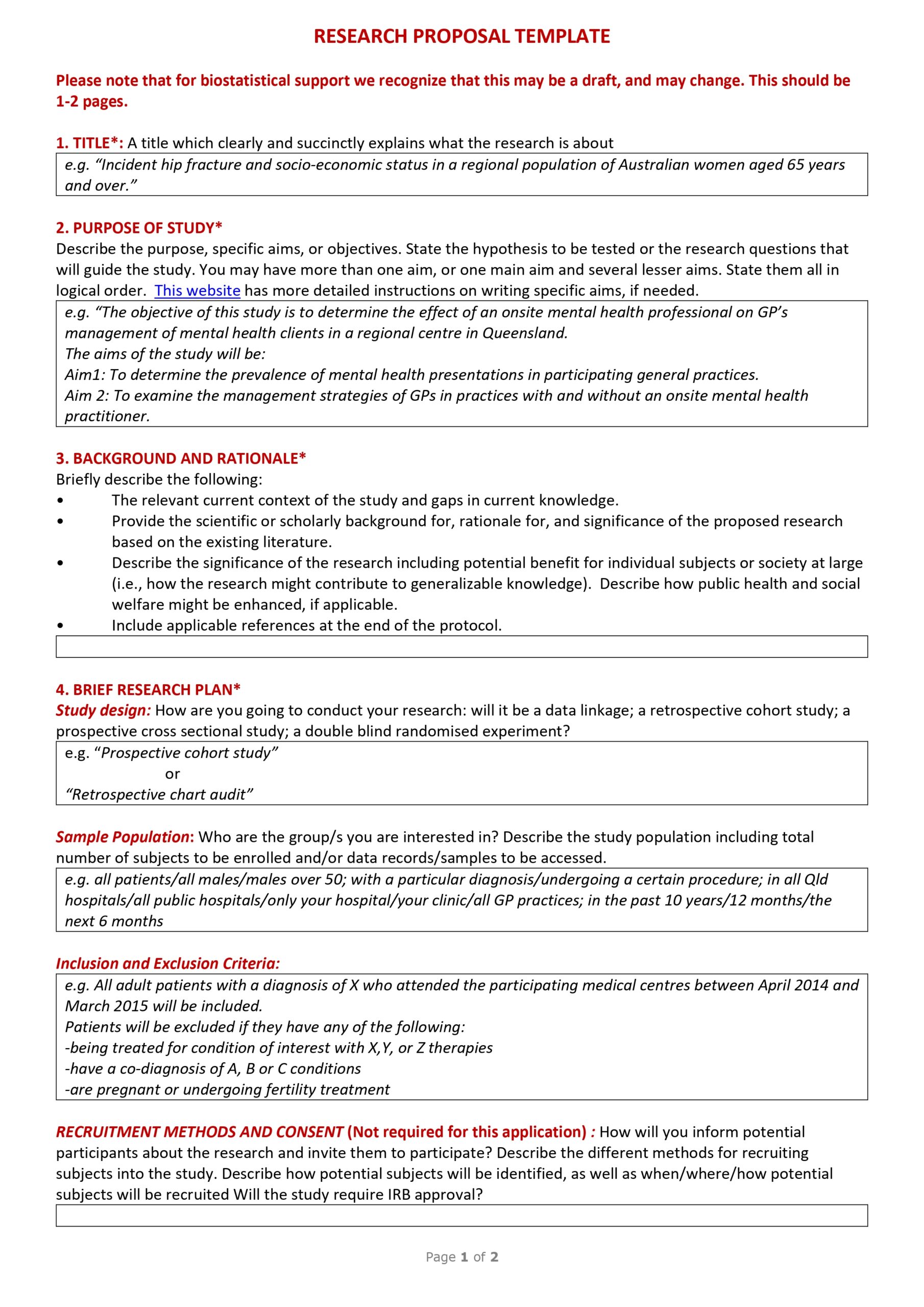

What follows is a collection of advice for writing research grants to the National Science Foundation. It includes some guidelines on how to write an NSF proposal and how to get the latest version of the NSF forms. Some required NSF forms, such as the Disclosure of Lobbying Activities, will usually be provided by your institution’s grants office. This document focuses on writing proposals to NSF, but the general advice can be applied to writing any proposal. I. General adviceAlways read the RFP (request for proposal) to find out what the funders want. They will give you money only if you can help them reach their goals. The goals of funding agencies (public and private) vary dramatically. A successful proposal to NSF looks nothing like a successful proposal to NASA. Even within an agency, the style of proposals can be different among internal divisions. Find out about the agency, its goals, and its review system. All proposals should answer the following questions in one form or another. II. Writing NSF proposalsNSF is organized a lot like a university, except that instead of departments and colleges it has divisions and directorates. The Program Directors (PDs, also equivalently called program managers and program officers) are like professors (and a lot of them are professors on leaves of absence). They have areas of specialization which correspond to the research areas covered by their programs. The division directors are like department chairs. They oversee the broad research areas covered by the programs and deal with administrative issues. The Assistant Directors are like Deans of Colleges. They lead the directorates and are responsible for the major research directions in Engineering, Physical Sciences, etc. The Director of NSF, who is like a university president or chancellor, is responsible for the overall direction of Science and Engineering Research. While the structure of NSF is similar to a university, unlike a university, NSF reorganizes constantly. This means that you may get to know a program director who may suddenly return to his or her university or may be reassigned to another program -- or that your program may be merged with a different program. While this is disconcerting in the short run, in the long run it keeps programs from stagnating and helps NSF keep on the forefront of research areas. Find out which program supports your research area. (It's not always obvious). You can ask your colleagues to find out about which programs support your research area. Find out if there are other people at NSF you should talk to and what special initiatives might apply to you. You can find the list of telephone numbers and e-mail addresses from the NSF web site (http://www.nsf.gov/). Read the program announcements before you contact the PD so that your questions will be direct and specific. The easiest way to get started is to send a brief email to the program director stating which program you are interested in applying to, a short statement of your relevant research interests, your availability by phone or email, and a one-page attachment that covers the first three questions above: what’s the problem, why it’s important, and what your key idea is. Don’t spend a lot of time/space giving the big picture on, e.g. cybersecurity; you are talking to an expert your area. Some PDs prefer e-mail; some prefer phone calls. Some like to talk to Principal Investigators (PIs); some don’t. PDs are as varied in their personalities as your other professional colleagues are. If you do talk to a PD on the phone, remember to listen; don’t just pitch your idea non-stop. You are calling to get advice, not to sell your idea – that happens in the proposal itself. Remember to say "thank you." (Don't be discouraged if they are rough on you. They spend most of the day on the computer and the phone and the rest of the time they're traveling and staying in government-rate hotels.) Treat the PDs as if they are intelligent people (even if you doubt it). The PD will assign the reviewers and will make the final decision. You don't have to be a sycophant, just be polite. (This advice comes from a former NSF program director.) Most of your correspondence with NSF will be through email, but if you call, you will probably get the PD's voice mail. Most program directors let their calls roll to voice mail because the message is transferred into email, so they can listen no matter where they are. Also, if you are calling about a proposal or a grant, include the NSF proposal number so the PD has all the information at hand when returning your call. When you call, · clearly state who you are, · your institutional affiliation, · why you are calling, · give the proposal or grant number if you have it, and · provide several times when you will be available for a call back. Also, oddly, the NSF phone system displays the caller ID when the call is in progress, but the number disappears after the call is over and, as far as I could tell, there is no way to get it back. So don't count on the program officer being able to see that you called. Leave a message if you want them to know that you called. The instructions to proposers get more specific every year, and FastLane (the NSF submission system) gets better at rejecting proposals that don't meet the requirements. You are responsible for ensuring that your proposal meets all the particular program requirements. Follow the directions! (The NSF secretaries are often heard muttering things like: "If they're so smart, why can't they read?") The number of proposals submitted to NSF has increased dramatically over the last decade. As a result, fewer proposals are funded. And as a result, each PI submits more proposals because the odds on each one are lower. DO NOT submit essentially the same proposal to several programs. The proposal will probably go to at least one duplicate reviewer, who will get angry that you are burdening the system, will recommend that both proposals be rejected, and will put a black mark next to your name. DO NOT submit a proposal that is rushed and not the best that you can do. Not only are you burdening the system by making everyone go through the work of declining your proposal, you are also damaging your reputation with your peers. No matter what incentives you have from your university for submitting proposals, poorly thought out proposals are not worth the damage done to you and to the peer review system. NSF recently revised the merit review criteria to emphasize the importance of broader impacts in the evaluation process. The following excerpt is from the instructions to NSF reviewers:

When evaluating NSF proposals, reviewers should consider what the proposers want to do, why they want to do it, how they plan to do it, how they will know if they succeed, and what benefits would accrue if the project is successful. These issues apply to the technical aspects of the proposal and the way in which the project may make broader contributions. To that end, reviewers are asked to evaluate all proposals against two criteria:

· Intellectual Merit: The intellectual Merit criterion encompasses the potential to advance knowledge; and · Broader Impacts: The Broader Impacts criterion encompasses the potential to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of specific, desired societal outcomes.

The following elements should be considered in the review for both criteria: 1. What is the potential for the proposed activity to a. advance knowledge and understanding within its own field or across different fields (Intellectual Merit); and b. benefit society or advance desired societal outcomes (Broader Impacts)? 2. To what extent do the proposed activities suggest and explore creative, original, or potentially transformative concepts? 3. Is the plan for carrying out the proposed activities well-reasoned, well-organized, and based on a sound rationale? Does the plan incorporate a mechanism to assess success? 4. How well qualified is the individual, team, or institution to conduct the proposed activities? 5. Are there adequate resources available to the PI (either at the home institution or through collaborations) to carry out the proposed activities?

As you write your proposal, you should keep the review criteria in mind. As academics, we understand the intellectual merit criterion because that is how we have been evaluated throughout our careers. However, many academics struggle with the broader impacts criterion. You need to convince the reviewers that your question is not just intellectually challenging, but also that the resulting knowledge will benefit society and that you have a feasible plan to get the knowledge out of the university and get it used in the world. IV. Putting together your proposalThis section follows the general flow of creating the forms and text for an NSF proposal. Once you have a rough draft of your proposal, ask someone who is senior to you to read your proposal as if he or she were an NSF reviewer. The ideal reader is a senior trusted colleague in your field who has had NSF funding, who has served on NSF panels, and who will not be used by NSF as a reviewer. (See Section 2.5.e on conflicts of interest.)

The formatting requirements for proposals are given in the (GPG), which you can get from the . (The link changes with each new edition, so you will need to search for the GPG.) Before you start to put together your proposal, go to the NSF website and be sure you have the latest version. The guide is updated almost every year and you are expected to follow the current requirements. Your proposal may be returned without review if you don’t do this.

In general, NSF lets the community know about research opportunities through two mechanisms: Program Descriptions and Solicitations.

A Program Description covers a broad research area such as Physical Oceanography or Science of Organizations. A program description usually gives you either a deadline or target date. Deadlines are hard dates, and you must get your proposal in by midnight (your local time) on the given date or your proposal will not be considered in the current round of funding. Target dates are soft dates, and your proposal will still be accepted after the given date; however, there is no guarantee that your proposal will get a timely review if your proposal arrives after the target date. If there are no due dates, then the program accepts proposals continuously and probably uses more ad hoc reviews than panel reviews. (Section V explains the difference between these types of reviews.)

A Solicitation is more specific than a Program Description. Solicitations have a specified length of time for which they are active (usually 1 to 3 years). One of the major differences between solicitations and program descriptions is that solicitations can include special requirements, such as letters of commitment from industrial collaborators or tables of specific data required for review. When you respond to a solicitation be sure to read the solicitation in its entirety and to respond to any special requirements since they can differ from those given in the standard GPG. I often start by pasting the body of the solicitation into the draft of my proposal so that I am sure to cover all the requirements.

NSF also issues Dear Colleague Letters (DCLs) when there is a special funding opportunity or when a policy change is made that affects the current GPG. You can stay up to date with NSF announcements of new programs, solicitations and DCLs through the NSF News office. To receive email updates, go to and select Get News Updates by Email. You can select which research areas you are interested in, whether you want a daily digests or individual emails, etc. I get a daily digest, and I over- rather than under-select options. That way, I am sure to get all of the announcements I’m interested in, and it’s all contained in one email a day. The summary is a one page overview of the proposal. It is not an abstract. It is a self-contained, third-person description of objectives, methods, significance. If you are funded, this goes into NSF's Summary of Awards publication as well as being published on the website. It will be read by your colleagues, the general public, and Congress. Because PIs were not explicitly addressing Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts as instructed, NSF has changed the summary page to a form with separate sections for the overview, the statement of Intellectual Merit and the statement of Broader Impact.

Note: the Project Summary form accepts ASCII text only. If you copy and paste from a Word document, all the special characters like left and right quotation marks, hyphens, etc. will show up as question marks in the final version. Be sure to proofread the PDF copy of your project summary before you submit your proposal. Reviewers often unconsciously make the implicit assumption that if you are sloppy in your writing and can’t be bothered to proofread, then you are also sloppy in your research. There is a provision to upload a PDF if your project summary requires special formatting for equations or other technical content; however, the PDF must follow the project summary requirements with separate headings for the overview, statement of Intellectual Merit and the statement of Broader Impact. The project description has a 15 page limit. Proposals over this limit are returned without review. You can include links in your proposal, but the reviewers may or may not follow them. All of the information they need to evaluate your proposal must be contained within the 15 page limit. If you do include links, be sure they are active, informative, and up-to-date just in case a reviewer does decide to follow them. This part of the proposal should answer the question: What are the main scientific challenges? Emphasize what the new ideas are. Briefly describe the project's major goals and their impact on the state of the art. Give the reviewer the context for the proposal. Clearly state the question you will address: Surprisingly, this section can kill a proposal. You need to be able to put your work in context. Often, a proposal will appear naive because the relevant literature is not cited. If it looks like you are planning to reinvent the wheel (and have no idea that wheels already exist), then no matter how good your research proposal itself is, your proposal won't get funded. If you trash everyone else in your research field, saying their work is no good, you also will not get funded. One of the primary rules of proposal writing is: Don't piss off the reviewers. You can build your credentials in this section by summarizing other people's work clearly and concisely and by stating how your work uses their ideas and how it differs from theirs. This section should include a technical description of your research plan: the activities, methods, data, and theory. This should be equivalent to a PhD thesis proposal for the big leagues. Write to convince the best person in your field that your idea deserves funding. Simultaneously, you must convince someone who is very smart but has no background in your sub-area. The goal of your proposal is to persuade the reviewers that your ideas are so important that they will take money out of the taxpayers' pockets and hand it to you. This is the part that counts. WHAT will you do? Why is your strategy an appropriate one to pursue? What is the key idea that makes it possible for to answer this question? HOW will you achieve your goals? Concisely and coherently, this section should complete the arguments developed earlier and present your initial pass on how to solve the problems posed. Avoid repetitions and digressions. In general, NSF is more interested in ideas than in deliverables. The question is: What will we know when you're done that we don't know now? The question is not: What will we have that we don't have now? That is, rather than saying that you will develop a system that will do X, Y and Z, instead say why it is important to be able to do X, Y and Z; why X, Y and Z can't be done now; what knowledge is needed to make X, Y, and Z possible, your plan that will make it possible to do X, Y and Z; and, by the way, you will demonstrate X, Y and Z in a system. Right now, NSF is more open to application-oriented research. They need to show Congress that the money spent on research benefits the US economy. Some years ago, the word "applied" was a bad word at NSF. Now it's a good word. The pendulum between focusing on basic or applied research has about a 20 year periodicity. You always need to check to find out where it is at the moment. Check with the PD and knowledgeable colleagues. of the Proposed WorkIn the review criteria, Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts have the same weight. From the GPG (emphasis mine): Broader impacts may be accomplished through the research itself, through the activities that are directly related to specific research projects, or through activities that are supported by, but are complementary to the project. NSF values the advancement of scientific knowledge and activities that contribute to the achievement of societally relevant outcomes. Such outcomes include, but are not limited to: full participation of women, persons with disabilities, and underrepresented minorities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); improved STEM education and educator development at any level; increased public scientific literacy and public engagement with science and technology; improved well-being of individuals in society; development of a diverse, globally competitive STEM workforce; increased partnerships between academia, industry, and others; improved national security; increased economic competitiveness of the United States; and enhanced infrastructure for research and education. Remember that all of the proposals going to a review panel are in the same area of research, so you need to distinguish your proposal by what YOU are going to do to help NSF get the knowledge out of the academy and into the world. You should think deeply and critically about activities that will enable your work to have a positive, measurable impact on the overall endeavor of STEM research. Present a plan for how you will go about addressing/attacking/solving the questions you have raised. Discuss expected results and your plan for evaluating the results. How will you measure progress? Include a discussion of milestones and expected dates of completion. (Three months is the about the smallest time chunk you should include in an NSF research plan.) You are not committed to following this plan - but you must present a FEASIBLE plan to convince the reviewers that you know how to go about getting research results. For new PIs, this is often the hardest section to write. You don't have to write the plan that you will follow no matter what. Think of it instead as presenting a possible path from where you are now to where you want to be at the end of the research. Give as much detail as you can. (You will always have at least one reviewer who is a stickler for details.) If any of the PIs have received NSF support in the past 5 years, you must include a summary of the results of previous work. The pages in this section count toward the total 15 pages. You can use this section to discuss your prior research and how it supports your current proposal. Note that you must report both on the results for Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. One of the purposes of this section is to help the reviewers evaluate your track record, so be sure to make a strong case for your results in both categories. and ;The references are a separate section that lists the pertinent literature that has been referenced within the project description. Remember to proofread the reference list. Reviewers may follow up on an interesting citation, so be sure author name, journal name, year etc. are correct. Program directors often look in the bibliography for potential reviewers, and reviewers often look in the bibliography to see if their work is cited. If your bibliography has a lot of peripheral references, your proposal may be sent to reviewers whose work is not directly related to yours and who may not understand your proposal. On the other hand, if you do not cite the relevant literature, your proposal may be sent to reviewers who are not cited and who will criticize you for not knowing the literature. The references do not count in the 15 page proposal limit. Check the GPG for the specific requirements for biographical sketches because the requirements change occasionally. The goal of the biosketch is to provide reviewers with your credentials that will help them evaluate whether you have the background, knowledge and skills to perform the proposed research. The biosketch also helps identify your conflicts of interest. Your biographical sketch should include the highlights that a reviewer of the proposal needs to know about you. Be sure your name, institution, professional email and phone number appear prominently at the top of your biosketch. Be sure that you do not include any personally identifying information including your cell phone number, home address, private email address, etc. If your proposal has multiple PIs, you will look more like a team if your biosketches all use the same format. The current requirements are:

a) Your professional preparation: undergraduate, graduate nd postdoctoral. Include the institution, major, degree and year.

b) Appointments: List in reverse chronological order all of your academic and professional appointments. Include your current appointment c) Publications: List up to five publications, patents, copyrights, or software systems , plus up to five other significant publications. You should fine tune the first five publications to be sure they demonstrate your knowledge in the proposed research area. Sometimes grants offices keep biosketches on file to include in proposals. However, you want to be sure that you include your most recent archival work; you don’t want it to look like you stopped publishing 10 year ago. Also, if you work in several areas or want to highlight a particular area of expertise, be sure to select your five works most relevant to the current proposal. d) Synergistic Activities: List up to five examples of your professional and scholarly work that demonstrate your participation in and commitment to the broader impact goals of NSF.

e) Collaborators and other affiliations; Conflicts of Interest (COI): This section has three parts: a) collaborators and co-editors; b) your graduate and post graduate advisors and c) the current and former students who you advised as graduate or post graduate students. (See the GPG for the exact requirements.)

The information in this section serves many purposes. A reviewer may be interested in the number of PhD students you have advised and what kinds of careers they have gone on to; they may look at your collaborators to see whether you work with industry, with people from other fields, or with people at other universities. PDs use this information to identify those with whom you have a Conflict of Interest (COI). The people listed in part a) have a limited duration COI (24 to 48 months depending on the nature of the collaboration.) The people listed in b) and c) have a life-time COI. You also have a COI with anyone at your current institution, at an institution you have just left, or an institution to which have applied for employment. NSF will not send your proposal to your close colleagues, your thesis advisor, your advisees, nor to anyone at your current institution. You may list such people explicitly, if you wish.

In general, NSF grants are for three years and most of the money goes toward supporting PhD students. A typical budget for a single PI grant is about $100K/year, which will pay for a graduate student (tuition and stipend), about 10% of the professor's time to supervise the student, a little bit of travel, copying, and overhead. However, the grant size varies from division to division. Ask someone in your area what is typical. Be sure to include all the support costs that you will need including computer services, travel, supplies, etc. NSF may cut your budget, but they'll never give you more than you ask for, so be sure to ask for everything you need. Describe, justify, and estimate cost of equipment items $5000 or more. (Double check the GPG for the current dollar limit.) If your equipment needs change between the time you submit the proposal and the time it is granted, you can still buy what you need -- But be sure to talk to the university grants office BEFORE you buy the new equipment. There are special rules about equipment money because it is usually exempt from overhead charges. Also, NSF will only provide equipment money for research computers. Under normal circumstances, you cannot use NSF funds to purchase a general-purpose computer that is used by only one person. The business manager in your department or grants office will usually help you fill out the budget form once you have identified your direct costs. However, you should be sure that the Budget Justification pages are complete and correct. Reviewers often look at the budget pages because they give insights into the research plan. Who is being paid to do the work? What priorities are reflected in the budget? Are the resources requested sufficient to carry out the plan? Does the budget look padded or lean? For example, if you ask for thousands of dollars in international travel which isn’t justified within your proposal, this will raise red flags with the reviewers. Note that NSF does not allow voluntary cost sharing. Unless a solicitation gives special instructions for overhead rates, you must use the overhead rate negotiated by your university; you cannot reduce the bottom line on your budget by changing the overhead rate. List all current and pending support on the given forms. Your institution’s grants office can probably help with these. If you have submitted the same proposal to more than one agency, be sure that you declare it on the cover page and in the current and pending support section. If you don't and the same reviewer is picked by both agencies, you won't get funded and your reputation will be damaged. Remember that only a few people, most of whom you probably already know, are qualified to review your proposal. This section should focus on the facilities available to you that you need to do your research. If you will rely on any specialized equipment, describe it. The question in the reviewer's mind is: Do you have the necessary resources to carry out the research? In addition, if you are asking for equipment in your proposal, you will want to make clear what equipment you don't have. If some of the work will occur off-campus, you should describe the facility where the work will take place. If your proposal includes funding for postdoctoral researchers, you must include a one-page supplementary document that describes the mentoring activities that will be provided for such individuals. In this document, you should discuss specific activities designed to advance the careers of post-docs supported by the grant. Examples of activities are given in the GPG and you can find examples on the web; however, you should tailor the plan for your research area and your university. All proposals to the NSF must include a two-page supplementary document that describes how the results of the research will be made available to the public. The plan should cover: Check to see if there is special guidance for the program you are applying to. Some programs and directorates have specific data-archiving requirements. Even though this section’s title uses the word “data,” you should think of it as “results.” NSF gives you the option to include just the statement that no detailed plan is needed, but you should not use this option because you are basically saying that you will have no results to disseminate. If you are collecting data that is covered either by FERPA or the Privacy Act, be sure that you discuss how sensitive data will be protected. Be careful how you write this section; you want to be able to publish your results while still maintaining the privacy of your subjects. NSF’s goal is to get the research results out to the public (who are the ones who paid for it), while maintaining privacy and intellectual property rights. Again, you can find many sample data management plans on the web. Be sure that your plan is relevant to your research and your university. V. What happens to your proposal after it is submitted to NSF?All proposals arrive at NSF electronically - mostly through www.fastlane.nsf.gov and occasionally through www.grants.gov. The proposals are routed based on the program announcement number or the NSF division given by the PI. (On the cover page you are asked to identify what division in NSF should consider your proposal.) Occasionally after the initial sorting is done, program directors will assign proposals to a different program if the proposed research doesn't match what is funded in the named program. Once the proposal has been assigned to a program director, it is ready for review. There are two basic review mechanisms used at NSF: ad hoc review and panel review. Both are single blind peer review mechanisms: that is, the reviewers (who are the PI's peers) know who the PI is, but the PI does not know who the reviewers are. Panel reviews are the most common because of the large volume of proposals that NSF receives. Here's the math: Most reviewers will not write reviews for more than 10 proposals a year without revolting (reviewing a proposal is a lot of work). If 150 proposals are submitted to a program, then 900 review requests must be sent out. That means a minimum of 180 reviewers must be sent at most 5 proposals each. Three reviews per person per year is more realistic - so that means the program director must have access to 300 of the proposal writers' peers in order to get the peer review system to work. And that's just for one program. All the other program directors are working with the same numbers -- and the expertise of many reviewers overlaps several programs. For a panel review, the program director selects 10 to 15 experts in a field and asks them review a set of related proposals. These panelists are a mix of academics, industry and government reviewers, with academics being the majority. Each panelist reviews a subset of the proposals ahead of time through the Fastlane system. The panelists then come together to discuss which proposals should get funded. Most reviewers find it easier to rank a set of proposals than to write a detailed review of each proposal. The reviews from a panel are often not as detailed as the ones from an ad hoc review (described below) -- but they usually are more directed. If one reviewer completely misses the point of a proposal (which they sometimes do), this will come out during the panel discussion so you get fewer out-in-left-field reviews from panels than from ad hoc review. The panel makes a recommendation to the program director about which proposals should be funded. The program director can assign an individual to review a proposal outside the panel system. Ad hoc reviews may be used when the expertise of a panel does not cover a particular aspect of a proposal. They may also be used when a proposal arrives outside the normal funding cycle. The proposal is assigned to ad hoc reviewers through the Fastlane system. The reviewer is given about two weeks to a month to review the proposal. Again, the review happens within the Fastlane system. Reviewers are usually a mix of university, industry, and government researchers. Almost always, the majority are academics. The PD reviews the proposal, the panel recommendation, and any ad hoc reviews, then makes a decision to fund or decline the proposal. The PDs must exercise judgment. For example, a reviewer might appear to be a perfect match for a proposal -- but when the review comes in, it may be obvious that the PI's work conflicts with the reviewers work, and the reviewer is biased. Often the decision to fund involves deciding whether to fund the proposal at the full or reduced amount. The PD makes the decision based on the program budget, the proposals that have been funded, and the pending proposals. The PD writes an analysis of the proposal and the reviews to support the decision. The proposal goes to the division director who must concur with the decision for it to be official. You are notified by email once the decision is final. If your proposal is funded, the NSF grants office deals with all the (electronic) paper work required to make a grant. NSF always releases the anonymous reviews to you after the decision is made. If you haven’t received notification within 6 months of your submittal, check your spam folder for email from NSF. (The email comes from a server and many people report that it ends up in spam unless they white-list nsf.gov.) You can also login to Fastlane to check the status. Only call the PD as a last resort. Note: A grant from NSF goes to the institution, not to the PI. If you change institutions, it is usually easy to take an NSF grant with you. However, you must negotiate with your current and future institution. NSF will not intervene in these negotiations. Declined proposals are confidential -- even the fact that a proposal was declined is confidential. For grants, the titles, abstracts, PIs, funding amounts, .. are public information, but the proposal itself is confidential. Almost all NSF information is available over the web. The main NSF web page gives you access to all NSF program descriptions, publications (including the NSF Grant Proposal Guide), program descriptions and current deadlines, the phone numbers and e-mail addresses of project directors, etc. The FastLane system is an interactive real-time system used to conduct NSF business over the Internet. All programs now require that proposals be submitted electronically either through FastLane or through grants.gov. The grants office at your institution can set up an account for you so that you can submit proposals and check their status through FastLane. If you are asked to write a review or be on a panel, the program officer will give you an id and password to give you access to the proposals. Aside on Fastlane: The first time I was a PD at NSF in the mid 1980s, Fastlane was just coming into existence through the efforts of Erich Bloch, then the Director of NSF and a former IBM researcher and executive. I returned to NSF as a PD in 2010 and that was the year that all proposal processing was done completely electronically. In order to update the software methods and make NSF funding more transparent to the public, the current plan is to migrate the functions of Fastlane to research.gov and to grants.gov. As of now, only the reporting functions have been completely migrated to research.gov. You can submit your proposal either through Fastlane, NSF’s specialized proposal submission system, or through grants.gov, the submission system for all proposals to the US government. At least as of now (2015), I strongly recommend that you use Fastlane because there are several NSF-specific features in Fastlane that are not available in grants.gov. Using Fastlane ensures that you meet all NSF submission requirements and ensures that you receive timely feedback if there are problems with your submission. In the long run, Fastlane will almost certainly be subsumed by grants.gov, but the research community will receive many warnings and updates before this occurs. If your institution’s grants office requires you to use grants.gov, don’t worry that your proposal will be penalized. It just requires more work on the part of the NSF support staff both to get the proposal from grants.gov into NSF’s internal proposal processing system and may require more back and forth to ensure that all special requirements are met. Start early if you haven’t used Fastlane before. There are many sections and forms to fill out. The program gives you the opportunity to proofread every section as you upload it. Always click "Proofread PDF" button. READ the pdf and be sure it is OK before you hit the "Accept" button. Do not treat the "Accept" button like a "Yeah, Sure, Whatever" button. Don’t call the PD and ask to replace a corrupt file with the correct one. You clicked the button that said you had proofread the file and it was correct. VII. Being a panelist or reviewerRemember that for every proposal you submit to NSF, at least five or six of your peers take the time to read it, write a review, and travel to DC to discuss it. Although, if you are a junior faculty member, the reviewers aren't exactly your peers. Panels tend to be weighted toward more senior members of the community, and these are the people who will be asked to write letters for your promotion and tenure case and they are also are the people who are on program committees and editorial boards. Only submit your best work! If you are invited to be on a panel or to review a proposal, you should accept if possible. Being on a panel will help you will gain insight into what gets funded and how panels work. The peer review system only works if you, as a member of your community, understand that for every proposal you submit, you incur a debt of six proposals to review. Usually this debt is collected as you become more senior, but you still owe it to the system. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

NSF FellowshipThe National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship ( NSF GRFP ) is a great way to start a research career. I was a successful applicant in 2010. Below are some details about the program and some tips for applying. You will also find many examples of successful essays and you can even submit your own essays if you are willing to serve as inspiration for the next round of applicants. Note, this advice was last updated in Sept 2021. What is it?The NSF GRFP provides $34,000 to the student and some money to your department for three years. You have the flexibility to defer for up to two years in case you have another source of funding (but you cannot defer to take a year off). The basic requirements are: 1. US Citizen, US National, or permanent resident 2. Currently a graduating Senior or First/Second year graduate student 3. Graduate students may only apply in their first OR second year (NOT both) . I have some thoughts on which year to apply . 4. Going into science research (does not apply to medical school) Check out the official requirements at the NSF GRFP website . Here is the more detailed NSF presentation on the requirements. The deadlines are usually the last week of October , but it is never too early to start. Basic Outline of Application ProcessYou will need to write two essays: Personal Statement, Relevant Background, and Future Goals (3 pages) Graduate Research Statement (2 pages) You will need to get at least three letters of reference These essays will be reviewed on the criteria of Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. And that's really it. The challenge is to sell yourself in 5 pages and to successful address the two criteria. Tips for Getting StartedRead over the official NSF GRFP website , especially their tips . Look through the NSF GRFP FAQ , with detailed answers here. Here is a detailed website from Robin Walker . She has a very very thorough guide to the application . Look at advice from past winners. There are lots of great advice out there, but in an interest to not overload you, here are my personal top choices. You can find more in my examples table at the bottom of the page. Mallory Ladd - If you can follow her schedule, you should be more than prepared Claire Bowen - Lots of advice interleaved with excerpts from successful essays DJ Strouse - Applied under old system, but still great advice. Blengineers - Fun video series of application tips Read an example essay. I have posted all of my essays (and others) as well as my ratings sheets at the bottom of this page and organized into them into a table . Personally, I found this extremely useful and I have to give credit to two University of Wisconsin NSF GRFP winners who shared their essays with me, without which I was struggling on how to start the application. Check out an old guide for reviewers . For current discussions on the application process, check out this years NSF GRFP discussion at The GradCafe Forums . Some past years discussions include: 2020-2021 , 2019-2020 , 2018-2019 , 2017-2018 , 2016-2017 , 2015-2016 , 2014-2015 , 2013-2014 , 2012-2013 , 2011-2012 , and 2010-2011 . General AdviceEvery essay should address both Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. Each essay needs explicit headers of Intellectual Merit / Broader Impacts . NSF GRFP funds the person, not the project. The most important choice you make is designating the primary field (Chemistry vs Physics & Astronomy, etc). The subfield is less important. If you are an undergrad doing research, I would strongly suggest to make your research proposal related to what you are currently researching as long as: 1. you are going to apply to programs in the same primary field and 2. there is at least a small chance (even if only a few percent) that you could do something related to your proposal in graduate school. NSF will not force you to follow through with the research; instead they just want to see that you can actually write a proposal. I personally wrote about my undergraduate research. It was in physics and I only applied to physics graduate schools (so same primary field), but I was not sure I wanted to continue with it in graduate school, and in fact it ended up being impossible since I did not get into any graduate schools with anyone doing research in my proposed subfield. Write for a general science audience and assume the reviewer is in your primary field, but not your subfield. This is NSF's tentative review panels , you can see that the only guarantee is that the reviewer is in your primary field. Ask for letters of reference early and gently remind your writers of the deadline. Get a diverse set of letter writers. I had my current adviser (who was doing research similar to what I proposed), a past research adviser, and my boss at a tutoring center. Therefore, I had two letters addressing my intellectual merit, while one letter addressed broader impacts. Ask for help. Your current university probably has a writing center . Don't be shy, they will love to help you. Also try asking around your department to find students who have applied previously. Review Criteria Details(Below is direct text from NSF but with sentences cut and added highlights) General Review Criteria In considering applications, reviewers are instructed to address the two Merit Review Criteria as approved by the National Science Board - Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. Therefore, applicants must include separate statements on Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts in their written statements in order to provide reviewers with the information necessary to evaluate the application with respect to both Criteria as detailed below. Reviewers will be asked to evaluate all proposals against two criteria: Intellectual Merit: the potential to advance knowledge Broader Impacts: the potential to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of specific, desired societal outcomes. The following elements should be considered in the review for both criteria: What is the potential for the proposed activity to Advance knowledge and understanding within its own field or across different fields (Intellectual Merit); and Benefit society or advance desired societal outcomes (Broader Impacts)? To what extent do the proposed activities suggest and explore creative, original, or potentially transformative concepts? Is the plan for carrying out the proposed activities well-reasoned, well-organized, and based on a sound rationale ? Does the plan incorporate a mechanism to assess success ? How well qualified is the individual, team, or organization to conduct the proposed activities? Are there adequate resources available to the PI (either at the home organization or through collaborations) to carry out the proposed activities? Extra details on Broader Impacts: (additional tips from NSF here ) Broader impacts may be accomplished through the research itself , through the activities that are directly related to specific research projects , or through activities that are supported by, but are complementary to, the project . NSF values the advancement of scientific knowledge and activities that contribute to achievement of societally relevant outcomes. Such outcomes include, but are not limited to: full participation of women, persons with disabilities, and underrepresented minorities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); improved STEM education and educator development at any level; increased public scientific literacy and public engagement with science and technology; improved well-being of individuals in society; development of a diverse, globally competitive STEM workforce; increased partnerships between academia, industry, and others; improved national security; increased economic competitiveness of the US; and enhanced infrastructure for research and education. Merit Review Criteria specific to the GRFP Intellectual Merit Criterion : the potential of the applicant to advance knowledge based on a holistic analysis of the complete application, including the Personal, Relevant Background, and Future Goals Statement, Graduate Research Plan Statement, strength of the academic record, description of previous research experience or publication/presentations, and references. Broader Impacts Criterion : the potential of the applicant for future broader impacts as indicated by personal experiences, professional experiences, educational experiences and future plans. Review Criteria: My Two CentsHere is how I like to think of the review criteria, point by point. How would answering this research question change science (Intellectual Merit) or society (Broader Impacts)? Why should I fund you specifically, and not just this research question? What innovation do you specifically bring to the table? Is there a detailed plan? With built in measures of success? What are your qualifications? Can you actual carry out the needed research? At the end of each essay, you should be able to check off how you answered each point above for BOTH Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. Personal Statement, Relevant Background, and Future Goals: Essay Prompt from NSFPrompt in 2021: Please outline your educational and professional development plans and career goals. How do you envision graduate school preparing your for a career that allows you to contribute to expanding scientific understanding as well as broadly benefit society? Additional prompt previously provided by NSF: Describe your personal, educational, and/or professional experiences that motivate your decision to pursue advanced study in science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM). Include specific examples of any research and/or professional activities in which you have participated. Present a concise description of the activities, highlight the results and discuss how these activities have prepared you to seek a graduate degree. Specify your role in the activity including the extent to which you worked independently and/or as part of a team. Describe the contributions of your activity to advancing knowledge in STEM fields as well as the potential for broader impacts (See Solicitation, Section VI, for more information about Broader Impacts). NSF Fellows are expected to become globally engaged knowledge experts and leaders who can contribute significantly to research, education, and innovations in science and engineering. The purpose of this essay is to demonstrate your potential to satisfy this requirement. Your ideas and examples do not have to be confined necessarily to the discipline that you have chosen to pursue. Personal Statement, Relevant Background, and Future Goals Essay: My Two CentsBased on the new emphasis NSF GRFP general requirements, I would write the essay in three main sections with two subsections for Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. Personal Statement (~1 page). This is where you tell your unique story of either how you became interested in science, what makes you special, and/or any unique perspective you bring to science. Great place to mention if you had to overcome any hardships or would be adding to the diversity of the STEM field. Definitely use this section to highlight Broader Impacts. Relevant Background (~1 page). Hopefully you already have research experience, so explain how that has prepared you for success in graduate school and beyond. Mainly use this section for Intellectual Merit, but also highly the Broader Impacts of your research experience. Future Goals (~ 1/2 page). This is where you tie your personal background and scientific background into one cohesive vision for the future. Intellectual Merit (~1/4 page). Conclude the essay by summarizing all of your contributions to Intellectual Merit. Make sure this is an explicit header. Broader Impact (~1/4 page). Conclude the essay by summarizing all of your contributions to Broader Impact. Make sure this is an explicit header. Graduate Research Statement: Essay Prompt from NSFPresent an original research topic that you would like to pursue in graduate school. Describe the research idea, your general approach, as well as any unique resources that may be needed for accomplishing the research goal (i.e. access to national facilities or collections, collaborations, overseas work, etc). You may choose to include important literature citations. Address the potential of the research to advance knowledge and understanding within science as well as the potential for broader impacts on society. The research discussed must be in a field listed in the Solicitation (Section X, Fields of Study). Graduate Research Statement: My Two CentsI would recommend structuring the essay as follows: Introduction Introduce the scientific problem and its impact on science and society (emphasis on Review Criteria 1) Research Plan Show the major steps that need to be accomplished What is the creative part of your approach? Have you thought of alternatives for hard or crucial steps? What skills do you have to make this plan successful? Intellectual Merit Have a clear header for this section Clearly demonstrate that tackling this problem will make an impact and advance science Try to summarize how you hit all five Review Criteria Broader Impacts Paragraphs to address how this research impacts all five Review Criteria. (Optional). Could use the Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts sections as conclusion. If not, e nd with several sentences summarizing your project . This essay will be Intellectual Merit heavy, but still needs to address Broader Impacts. Show why the broader scientific community / society should care about your research! Examples of Successful EssaysThese are all the essays of recent winners that I could find online. If you want me to link to an example on your website, or if you are willing to share your essays but don't have a site, I can add it to the table if you fill out the contact form below . Some notes: Click here to apply your own sort / filters to the table . Remember the format changed starting in 2014! If I couldn't figure out the year, I filled in 2013 for old format and 2014 for new formats. Proposal Column --- Graduate Research Plan ( >= 2014) or Proposed Research ( <= 2013) Personal Column --- Personal, Relevant Background, and Future Goals ( >= 2014) or Personal ( <= 2013) Previous Column --- Previous Research Statement ( <= 2013 only) HM = Honorable Mention Can't find an example in your area? Tip from GradCafe Forum : politely email past winners ! I've linked to a lot of sites, let me know if any links break! A suggested fix is even better :) Example essays below, or open in Google Drive Submit Example Here

Plan & Manage

Sample NSF Data Management PlansThese examples from UC San Diego proposals are intended to provide a starting point for the development of other proposal-specific Data Management Plans. We thank the UC San Diego investigators who gave permission to include their DMPs in this collection. If you have a DMP you'd be willing to have included here, please contact the library Research Data Curation Program . Please keep in mind that these examples are project-specific. PIs are encouraged to submit draft DMPs well in advance of the proposal deadline to OCGA to ensure compliance with University policy. Office of the Director (OD)Office of cyberinfrastructure (od/oci).

Office of Integrative Activities (OD/OIA)

Directorate for Biological Sciences (BIO)Division of environmental biology (bio/deb).

Division of Integrative Organismal Systems (BIO/IOS)

Directorate for Computer & Information Science & Engineering (CISE)Division of computing and communication foundations (cise/ccf).

Directorate for Education & Human Resources (EHR)Division of graduate education (ehr/dge).

Directorate for Engineering (ENG)Division of chemical, bioengineering, environmental, and transport systems (eng/cbet).

Division of Civil Mechanical and Manufacturing Innovation (ENG/CMMI)

Division of Electrical, Communications and Cyber Systems (ENG/ECCS)

Directorate for Geosciences (GEO)Division of ocean sciences (geo/oce) physical oceanography (geo/po).

Directorate for Mathematical & Physical Sciences (MPS)Division of mathematical sciences (mps/dms).

Directorate for Social, Behavioral & Economic Sciences (SBE)Division of social and economic sciences (sbe/ses).

Crosscutting – Multiple Directorates and Offices

Submit a consultation request or email us at [email protected] . Search form

NSF GRFP Proposal LibraryFilter by....

Award Status

Translational Interests

Home ProgramBiochemistry Bioengineering Biomedical Informatics Cancer Biology Chemical and Systems Biology Developmental Biology Microbiology and Immunology Molecular and Cellular Physiology Neurosciences Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Structural Biology