- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

scientific method

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- University of Nevada, Reno - College of Agriculture, Biotechnology and Natural Resources Extension - The Scientific Method

- World History Encyclopedia - Scientific Method

- LiveScience - What Is Science?

- Verywell Mind - Scientific Method Steps in Psychology Research

- WebMD - What is the Scientific Method?

- Chemistry LibreTexts - The Scientific Method

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Redefining the scientific method: as the use of sophisticated scientific methods that extend our mind

- Khan Academy - The scientific method

- Simply Psychology - What are the steps in the Scientific Method?

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Scientific Method

Recent News

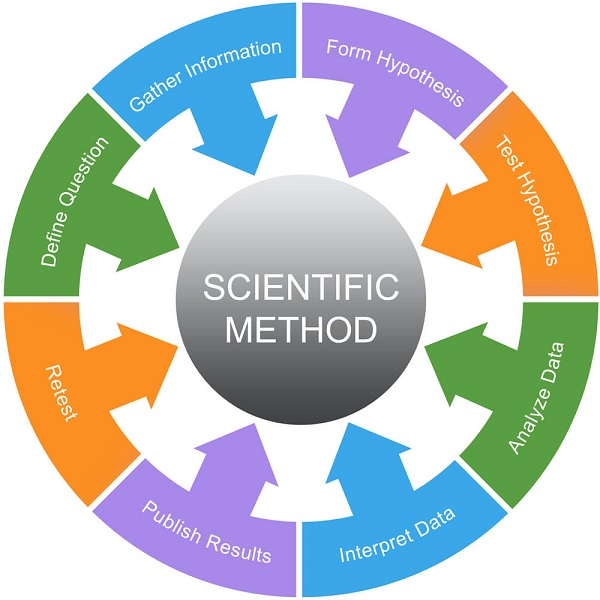

scientific method , mathematical and experimental technique employed in the sciences . More specifically, it is the technique used in the construction and testing of a scientific hypothesis .

The process of observing, asking questions, and seeking answers through tests and experiments is not unique to any one field of science. In fact, the scientific method is applied broadly in science, across many different fields. Many empirical sciences, especially the social sciences , use mathematical tools borrowed from probability theory and statistics , together with outgrowths of these, such as decision theory , game theory , utility theory, and operations research . Philosophers of science have addressed general methodological problems, such as the nature of scientific explanation and the justification of induction .

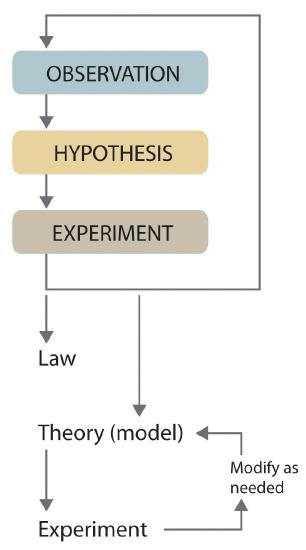

The scientific method is critical to the development of scientific theories , which explain empirical (experiential) laws in a scientifically rational manner. In a typical application of the scientific method, a researcher develops a hypothesis , tests it through various means, and then modifies the hypothesis on the basis of the outcome of the tests and experiments. The modified hypothesis is then retested, further modified, and tested again, until it becomes consistent with observed phenomena and testing outcomes. In this way, hypotheses serve as tools by which scientists gather data. From that data and the many different scientific investigations undertaken to explore hypotheses, scientists are able to develop broad general explanations, or scientific theories.

See also Mill’s methods ; hypothetico-deductive method .

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- Science Experiments for Kids

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

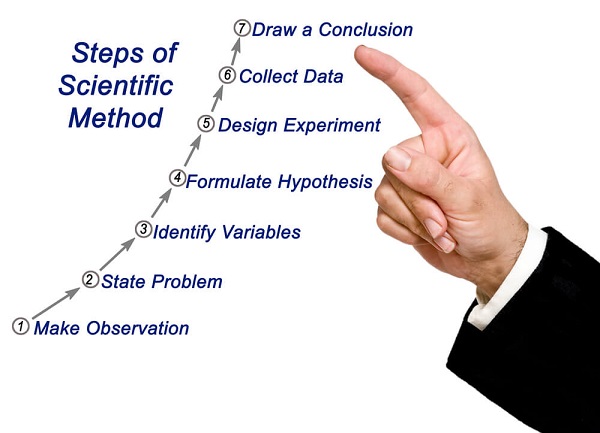

Steps of the Scientific Method 2

The scientific method is a system scientists and other people use to ask and answer questions about the natural world. In a nutshell, the scientific method works by making observations, asking a question or identifying a problem, and then designing and analyzing an experiment to test a prediction of what you expect will happen. It’s a powerful analytical tool because once you draw conclusions, you may be able to answer a question and make predictions about future events.

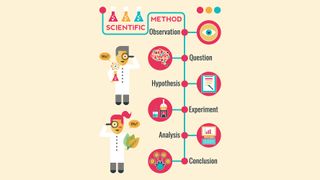

These are the steps of the scientific method:

- Make observations.

Sometimes this step is omitted in the list, but you always make observations before asking a question, whether you recognize it or not. You always have some background information about a topic. However, it’s a good idea to be systematic about your observations and to record them in a lab book or another way. Often, these initial observations can help you identify a question. Later on, this information may help you decide on another area of investigation of a topic.

- Ask a question, identify a problem, or state an objective.

There are various forms of this step. Sometimes you may want to state an objective and a problem and then phrase it in the form of a question. The reason it’s good to state a question is because it’s easiest to design an experiment to answer a question. A question helps you form a hypothesis, which focuses your study.

- Research the topic.

You should conduct background research on your topic to learn as much as you can about it. This can occur both before and after you state an objective and form a hypothesis. In fact, you may find yourself researching the topic throughout the entire process.

- Formulate a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a formal prediction. There are two forms of a hypothesis that are particularly easy to test. One is to state the hypothesis as an “if, then” statement. An example of an if-then hypothesis is: “If plants are grown under red light, then they will be taller than plants grown under white light.” Another good type of hypothesis is what is called a “ null hypothesis ” or “no difference” hypothesis. An example of a null hypothesis is: “There is no difference in the rate of growth of plants grown under red light compared with plants grown under white light.”

- Design and perform an experiment to test the hypothesis.

Once you have a hypothesis, you need to find a way to test it. This involves an experiment . There are many ways to set up an experiment. A basic experiment contains variables, which are factors you can measure. The two main variables are the independent variable (the one you control or change) and the dependent variable (the one you measure to see if it is affected when you change the independent variable).

- Record and analyze the data you obtain from the experiment.

It’s a good idea to record notes alongside your data, stating anything unusual or unexpected. Once you have the data, draw a chart, table, or graph to present your results. Next, analyze the results to understand what it all means.

- Determine whether you accept or reject the hypothesis.

Do the results support the hypothesis or not? Keep in mind, it’s okay if the hypothesis is not supported, especially if you are testing a null hypothesis. Sometimes excluding an explanation answers your question! There is no “right” or “wrong” here. However, if you obtain an unexpected result, you might want to perform another experiment.

- Draw a conclusion and report the results of the experiment.

What good is knowing something if you keep it to yourself? You should report the outcome of the experiment, even if it’s just in a notebook. What did you learn from the experiment?

How Many Steps Are There?

You may be asked to list the 5 steps of the scientific method or the 6 steps of the method or some other number. There are different ways of grouping together the steps outlined here, so it’s a good idea to learn the way an instructor wants you to list the steps. No matter how many steps there are, the order is always the same.

Related Posts

2 thoughts on “ steps of the scientific method ”.

You raise a valid point, but peer review has its limitations. Consider the case of Galileo, for example.

That’s a good point too. But that was a rare limitation due to religion, and scientific consensus prevailed in the end. It’s nowhere near a reason to doubt scientific consensus in general. I’m thinking about issues such as climate change where so many people are skeptical despite 97% consensus among climate scientists. I was just surprised to see that this is not included as an important part of the process.

Comments are closed.

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation:

- Guides research: A hypothesis provides a clear and specific direction for research. It helps to focus the research question, select appropriate methods and variables, and interpret the results.

- Predictive powe r: A hypothesis makes predictions about the outcome of research, which can be tested through experimentation. This allows researchers to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis and make new discoveries.

- Facilitates communication: A hypothesis provides a common language and framework for scientists to communicate with one another about their research. This helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promotes collaboration.

- Efficient use of resources: A hypothesis helps researchers to use their time, resources, and funding efficiently by directing them towards specific research questions and methods that are most likely to yield results.

- Provides a basis for further research: A hypothesis that is supported by data provides a basis for further research and exploration. It can lead to new hypotheses, theories, and discoveries.

- Increases objectivity: A hypothesis can help to increase objectivity in research by providing a clear and specific framework for testing and interpreting results. This can reduce bias and increase the reliability of research findings.

Limitations of Hypothesis

Some Limitations of the Hypothesis are as follows:

- Limited to observable phenomena: Hypotheses are limited to observable phenomena and cannot account for unobservable or intangible factors. This means that some research questions may not be amenable to hypothesis testing.

- May be inaccurate or incomplete: Hypotheses are based on existing knowledge and research, which may be incomplete or inaccurate. This can lead to flawed hypotheses and erroneous conclusions.

- May be biased: Hypotheses may be biased by the researcher’s own beliefs, values, or assumptions. This can lead to selective interpretation of data and a lack of objectivity in research.

- Cannot prove causation: A hypothesis can only show a correlation between variables, but it cannot prove causation. This requires further experimentation and analysis.

- Limited to specific contexts: Hypotheses are limited to specific contexts and may not be generalizable to other situations or populations. This means that results may not be applicable in other contexts or may require further testing.

- May be affected by chance : Hypotheses may be affected by chance or random variation, which can obscure or distort the true relationship between variables.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Biology archive

Course: biology archive > unit 1, the scientific method.

- Controlled experiments

- The scientific method and experimental design

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Scientific Method

Science is an enormously successful human enterprise. The study of scientific method is the attempt to discern the activities by which that success is achieved. Among the activities often identified as characteristic of science are systematic observation and experimentation, inductive and deductive reasoning, and the formation and testing of hypotheses and theories. How these are carried out in detail can vary greatly, but characteristics like these have been looked to as a way of demarcating scientific activity from non-science, where only enterprises which employ some canonical form of scientific method or methods should be considered science (see also the entry on science and pseudo-science ). Others have questioned whether there is anything like a fixed toolkit of methods which is common across science and only science. Some reject privileging one view of method as part of rejecting broader views about the nature of science, such as naturalism (Dupré 2004); some reject any restriction in principle (pluralism).

Scientific method should be distinguished from the aims and products of science, such as knowledge, predictions, or control. Methods are the means by which those goals are achieved. Scientific method should also be distinguished from meta-methodology, which includes the values and justifications behind a particular characterization of scientific method (i.e., a methodology) — values such as objectivity, reproducibility, simplicity, or past successes. Methodological rules are proposed to govern method and it is a meta-methodological question whether methods obeying those rules satisfy given values. Finally, method is distinct, to some degree, from the detailed and contextual practices through which methods are implemented. The latter might range over: specific laboratory techniques; mathematical formalisms or other specialized languages used in descriptions and reasoning; technological or other material means; ways of communicating and sharing results, whether with other scientists or with the public at large; or the conventions, habits, enforced customs, and institutional controls over how and what science is carried out.

While it is important to recognize these distinctions, their boundaries are fuzzy. Hence, accounts of method cannot be entirely divorced from their methodological and meta-methodological motivations or justifications, Moreover, each aspect plays a crucial role in identifying methods. Disputes about method have therefore played out at the detail, rule, and meta-rule levels. Changes in beliefs about the certainty or fallibility of scientific knowledge, for instance (which is a meta-methodological consideration of what we can hope for methods to deliver), have meant different emphases on deductive and inductive reasoning, or on the relative importance attached to reasoning over observation (i.e., differences over particular methods.) Beliefs about the role of science in society will affect the place one gives to values in scientific method.

The issue which has shaped debates over scientific method the most in the last half century is the question of how pluralist do we need to be about method? Unificationists continue to hold out for one method essential to science; nihilism is a form of radical pluralism, which considers the effectiveness of any methodological prescription to be so context sensitive as to render it not explanatory on its own. Some middle degree of pluralism regarding the methods embodied in scientific practice seems appropriate. But the details of scientific practice vary with time and place, from institution to institution, across scientists and their subjects of investigation. How significant are the variations for understanding science and its success? How much can method be abstracted from practice? This entry describes some of the attempts to characterize scientific method or methods, as well as arguments for a more context-sensitive approach to methods embedded in actual scientific practices.

1. Overview and organizing themes

2. historical review: aristotle to mill, 3.1 logical constructionism and operationalism, 3.2. h-d as a logic of confirmation, 3.3. popper and falsificationism, 3.4 meta-methodology and the end of method, 4. statistical methods for hypothesis testing, 5.1 creative and exploratory practices.

- 5.2 Computer methods and the ‘new ways’ of doing science

6.1 “The scientific method” in science education and as seen by scientists

6.2 privileged methods and ‘gold standards’, 6.3 scientific method in the court room, 6.4 deviating practices, 7. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

This entry could have been given the title Scientific Methods and gone on to fill volumes, or it could have been extremely short, consisting of a brief summary rejection of the idea that there is any such thing as a unique Scientific Method at all. Both unhappy prospects are due to the fact that scientific activity varies so much across disciplines, times, places, and scientists that any account which manages to unify it all will either consist of overwhelming descriptive detail, or trivial generalizations.

The choice of scope for the present entry is more optimistic, taking a cue from the recent movement in philosophy of science toward a greater attention to practice: to what scientists actually do. This “turn to practice” can be seen as the latest form of studies of methods in science, insofar as it represents an attempt at understanding scientific activity, but through accounts that are neither meant to be universal and unified, nor singular and narrowly descriptive. To some extent, different scientists at different times and places can be said to be using the same method even though, in practice, the details are different.

Whether the context in which methods are carried out is relevant, or to what extent, will depend largely on what one takes the aims of science to be and what one’s own aims are. For most of the history of scientific methodology the assumption has been that the most important output of science is knowledge and so the aim of methodology should be to discover those methods by which scientific knowledge is generated.

Science was seen to embody the most successful form of reasoning (but which form?) to the most certain knowledge claims (but how certain?) on the basis of systematically collected evidence (but what counts as evidence, and should the evidence of the senses take precedence, or rational insight?) Section 2 surveys some of the history, pointing to two major themes. One theme is seeking the right balance between observation and reasoning (and the attendant forms of reasoning which employ them); the other is how certain scientific knowledge is or can be.

Section 3 turns to 20 th century debates on scientific method. In the second half of the 20 th century the epistemic privilege of science faced several challenges and many philosophers of science abandoned the reconstruction of the logic of scientific method. Views changed significantly regarding which functions of science ought to be captured and why. For some, the success of science was better identified with social or cultural features. Historical and sociological turns in the philosophy of science were made, with a demand that greater attention be paid to the non-epistemic aspects of science, such as sociological, institutional, material, and political factors. Even outside of those movements there was an increased specialization in the philosophy of science, with more and more focus on specific fields within science. The combined upshot was very few philosophers arguing any longer for a grand unified methodology of science. Sections 3 and 4 surveys the main positions on scientific method in 20 th century philosophy of science, focusing on where they differ in their preference for confirmation or falsification or for waiving the idea of a special scientific method altogether.

In recent decades, attention has primarily been paid to scientific activities traditionally falling under the rubric of method, such as experimental design and general laboratory practice, the use of statistics, the construction and use of models and diagrams, interdisciplinary collaboration, and science communication. Sections 4–6 attempt to construct a map of the current domains of the study of methods in science.

As these sections illustrate, the question of method is still central to the discourse about science. Scientific method remains a topic for education, for science policy, and for scientists. It arises in the public domain where the demarcation or status of science is at issue. Some philosophers have recently returned, therefore, to the question of what it is that makes science a unique cultural product. This entry will close with some of these recent attempts at discerning and encapsulating the activities by which scientific knowledge is achieved.

Attempting a history of scientific method compounds the vast scope of the topic. This section briefly surveys the background to modern methodological debates. What can be called the classical view goes back to antiquity, and represents a point of departure for later divergences. [ 1 ]

We begin with a point made by Laudan (1968) in his historical survey of scientific method:

Perhaps the most serious inhibition to the emergence of the history of theories of scientific method as a respectable area of study has been the tendency to conflate it with the general history of epistemology, thereby assuming that the narrative categories and classificatory pigeon-holes applied to the latter are also basic to the former. (1968: 5)

To see knowledge about the natural world as falling under knowledge more generally is an understandable conflation. Histories of theories of method would naturally employ the same narrative categories and classificatory pigeon holes. An important theme of the history of epistemology, for example, is the unification of knowledge, a theme reflected in the question of the unification of method in science. Those who have identified differences in kinds of knowledge have often likewise identified different methods for achieving that kind of knowledge (see the entry on the unity of science ).

Different views on what is known, how it is known, and what can be known are connected. Plato distinguished the realms of things into the visible and the intelligible ( The Republic , 510a, in Cooper 1997). Only the latter, the Forms, could be objects of knowledge. The intelligible truths could be known with the certainty of geometry and deductive reasoning. What could be observed of the material world, however, was by definition imperfect and deceptive, not ideal. The Platonic way of knowledge therefore emphasized reasoning as a method, downplaying the importance of observation. Aristotle disagreed, locating the Forms in the natural world as the fundamental principles to be discovered through the inquiry into nature ( Metaphysics Z , in Barnes 1984).

Aristotle is recognized as giving the earliest systematic treatise on the nature of scientific inquiry in the western tradition, one which embraced observation and reasoning about the natural world. In the Prior and Posterior Analytics , Aristotle reflects first on the aims and then the methods of inquiry into nature. A number of features can be found which are still considered by most to be essential to science. For Aristotle, empiricism, careful observation (but passive observation, not controlled experiment), is the starting point. The aim is not merely recording of facts, though. For Aristotle, science ( epistêmê ) is a body of properly arranged knowledge or learning—the empirical facts, but also their ordering and display are of crucial importance. The aims of discovery, ordering, and display of facts partly determine the methods required of successful scientific inquiry. Also determinant is the nature of the knowledge being sought, and the explanatory causes proper to that kind of knowledge (see the discussion of the four causes in the entry on Aristotle on causality ).

In addition to careful observation, then, scientific method requires a logic as a system of reasoning for properly arranging, but also inferring beyond, what is known by observation. Methods of reasoning may include induction, prediction, or analogy, among others. Aristotle’s system (along with his catalogue of fallacious reasoning) was collected under the title the Organon . This title would be echoed in later works on scientific reasoning, such as Novum Organon by Francis Bacon, and Novum Organon Restorum by William Whewell (see below). In Aristotle’s Organon reasoning is divided primarily into two forms, a rough division which persists into modern times. The division, known most commonly today as deductive versus inductive method, appears in other eras and methodologies as analysis/synthesis, non-ampliative/ampliative, or even confirmation/verification. The basic idea is there are two “directions” to proceed in our methods of inquiry: one away from what is observed, to the more fundamental, general, and encompassing principles; the other, from the fundamental and general to instances or implications of principles.

The basic aim and method of inquiry identified here can be seen as a theme running throughout the next two millennia of reflection on the correct way to seek after knowledge: carefully observe nature and then seek rules or principles which explain or predict its operation. The Aristotelian corpus provided the framework for a commentary tradition on scientific method independent of science itself (cosmos versus physics.) During the medieval period, figures such as Albertus Magnus (1206–1280), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Robert Grosseteste (1175–1253), Roger Bacon (1214/1220–1292), William of Ockham (1287–1347), Andreas Vesalius (1514–1546), Giacomo Zabarella (1533–1589) all worked to clarify the kind of knowledge obtainable by observation and induction, the source of justification of induction, and best rules for its application. [ 2 ] Many of their contributions we now think of as essential to science (see also Laudan 1968). As Aristotle and Plato had employed a framework of reasoning either “to the forms” or “away from the forms”, medieval thinkers employed directions away from the phenomena or back to the phenomena. In analysis, a phenomena was examined to discover its basic explanatory principles; in synthesis, explanations of a phenomena were constructed from first principles.

During the Scientific Revolution these various strands of argument, experiment, and reason were forged into a dominant epistemic authority. The 16 th –18 th centuries were a period of not only dramatic advance in knowledge about the operation of the natural world—advances in mechanical, medical, biological, political, economic explanations—but also of self-awareness of the revolutionary changes taking place, and intense reflection on the source and legitimation of the method by which the advances were made. The struggle to establish the new authority included methodological moves. The Book of Nature, according to the metaphor of Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) or Francis Bacon (1561–1626), was written in the language of mathematics, of geometry and number. This motivated an emphasis on mathematical description and mechanical explanation as important aspects of scientific method. Through figures such as Henry More and Ralph Cudworth, a neo-Platonic emphasis on the importance of metaphysical reflection on nature behind appearances, particularly regarding the spiritual as a complement to the purely mechanical, remained an important methodological thread of the Scientific Revolution (see the entries on Cambridge platonists ; Boyle ; Henry More ; Galileo ).

In Novum Organum (1620), Bacon was critical of the Aristotelian method for leaping from particulars to universals too quickly. The syllogistic form of reasoning readily mixed those two types of propositions. Bacon aimed at the invention of new arts, principles, and directions. His method would be grounded in methodical collection of observations, coupled with correction of our senses (and particularly, directions for the avoidance of the Idols, as he called them, kinds of systematic errors to which naïve observers are prone.) The community of scientists could then climb, by a careful, gradual and unbroken ascent, to reliable general claims.

Bacon’s method has been criticized as impractical and too inflexible for the practicing scientist. Whewell would later criticize Bacon in his System of Logic for paying too little attention to the practices of scientists. It is hard to find convincing examples of Bacon’s method being put in to practice in the history of science, but there are a few who have been held up as real examples of 16 th century scientific, inductive method, even if not in the rigid Baconian mold: figures such as Robert Boyle (1627–1691) and William Harvey (1578–1657) (see the entry on Bacon ).

It is to Isaac Newton (1642–1727), however, that historians of science and methodologists have paid greatest attention. Given the enormous success of his Principia Mathematica and Opticks , this is understandable. The study of Newton’s method has had two main thrusts: the implicit method of the experiments and reasoning presented in the Opticks, and the explicit methodological rules given as the Rules for Philosophising (the Regulae) in Book III of the Principia . [ 3 ] Newton’s law of gravitation, the linchpin of his new cosmology, broke with explanatory conventions of natural philosophy, first for apparently proposing action at a distance, but more generally for not providing “true”, physical causes. The argument for his System of the World ( Principia , Book III) was based on phenomena, not reasoned first principles. This was viewed (mainly on the continent) as insufficient for proper natural philosophy. The Regulae counter this objection, re-defining the aims of natural philosophy by re-defining the method natural philosophers should follow. (See the entry on Newton’s philosophy .)

To his list of methodological prescriptions should be added Newton’s famous phrase “ hypotheses non fingo ” (commonly translated as “I frame no hypotheses”.) The scientist was not to invent systems but infer explanations from observations, as Bacon had advocated. This would come to be known as inductivism. In the century after Newton, significant clarifications of the Newtonian method were made. Colin Maclaurin (1698–1746), for instance, reconstructed the essential structure of the method as having complementary analysis and synthesis phases, one proceeding away from the phenomena in generalization, the other from the general propositions to derive explanations of new phenomena. Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and editors of the Encyclopédie did much to consolidate and popularize Newtonianism, as did Francesco Algarotti (1721–1764). The emphasis was often the same, as much on the character of the scientist as on their process, a character which is still commonly assumed. The scientist is humble in the face of nature, not beholden to dogma, obeys only his eyes, and follows the truth wherever it leads. It was certainly Voltaire (1694–1778) and du Chatelet (1706–1749) who were most influential in propagating the latter vision of the scientist and their craft, with Newton as hero. Scientific method became a revolutionary force of the Enlightenment. (See also the entries on Newton , Leibniz , Descartes , Boyle , Hume , enlightenment , as well as Shank 2008 for a historical overview.)

Not all 18 th century reflections on scientific method were so celebratory. Famous also are George Berkeley’s (1685–1753) attack on the mathematics of the new science, as well as the over-emphasis of Newtonians on observation; and David Hume’s (1711–1776) undermining of the warrant offered for scientific claims by inductive justification (see the entries on: George Berkeley ; David Hume ; Hume’s Newtonianism and Anti-Newtonianism ). Hume’s problem of induction motivated Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) to seek new foundations for empirical method, though as an epistemic reconstruction, not as any set of practical guidelines for scientists. Both Hume and Kant influenced the methodological reflections of the next century, such as the debate between Mill and Whewell over the certainty of inductive inferences in science.

The debate between John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) and William Whewell (1794–1866) has become the canonical methodological debate of the 19 th century. Although often characterized as a debate between inductivism and hypothetico-deductivism, the role of the two methods on each side is actually more complex. On the hypothetico-deductive account, scientists work to come up with hypotheses from which true observational consequences can be deduced—hence, hypothetico-deductive. Because Whewell emphasizes both hypotheses and deduction in his account of method, he can be seen as a convenient foil to the inductivism of Mill. However, equally if not more important to Whewell’s portrayal of scientific method is what he calls the “fundamental antithesis”. Knowledge is a product of the objective (what we see in the world around us) and subjective (the contributions of our mind to how we perceive and understand what we experience, which he called the Fundamental Ideas). Both elements are essential according to Whewell, and he was therefore critical of Kant for too much focus on the subjective, and John Locke (1632–1704) and Mill for too much focus on the senses. Whewell’s fundamental ideas can be discipline relative. An idea can be fundamental even if it is necessary for knowledge only within a given scientific discipline (e.g., chemical affinity for chemistry). This distinguishes fundamental ideas from the forms and categories of intuition of Kant. (See the entry on Whewell .)

Clarifying fundamental ideas would therefore be an essential part of scientific method and scientific progress. Whewell called this process “Discoverer’s Induction”. It was induction, following Bacon or Newton, but Whewell sought to revive Bacon’s account by emphasising the role of ideas in the clear and careful formulation of inductive hypotheses. Whewell’s induction is not merely the collecting of objective facts. The subjective plays a role through what Whewell calls the Colligation of Facts, a creative act of the scientist, the invention of a theory. A theory is then confirmed by testing, where more facts are brought under the theory, called the Consilience of Inductions. Whewell felt that this was the method by which the true laws of nature could be discovered: clarification of fundamental concepts, clever invention of explanations, and careful testing. Mill, in his critique of Whewell, and others who have cast Whewell as a fore-runner of the hypothetico-deductivist view, seem to have under-estimated the importance of this discovery phase in Whewell’s understanding of method (Snyder 1997a,b, 1999). Down-playing the discovery phase would come to characterize methodology of the early 20 th century (see section 3 ).

Mill, in his System of Logic , put forward a narrower view of induction as the essence of scientific method. For Mill, induction is the search first for regularities among events. Among those regularities, some will continue to hold for further observations, eventually gaining the status of laws. One can also look for regularities among the laws discovered in a domain, i.e., for a law of laws. Which “law law” will hold is time and discipline dependent and open to revision. One example is the Law of Universal Causation, and Mill put forward specific methods for identifying causes—now commonly known as Mill’s methods. These five methods look for circumstances which are common among the phenomena of interest, those which are absent when the phenomena are, or those for which both vary together. Mill’s methods are still seen as capturing basic intuitions about experimental methods for finding the relevant explanatory factors ( System of Logic (1843), see Mill entry). The methods advocated by Whewell and Mill, in the end, look similar. Both involve inductive generalization to covering laws. They differ dramatically, however, with respect to the necessity of the knowledge arrived at; that is, at the meta-methodological level (see the entries on Whewell and Mill entries).

3. Logic of method and critical responses

The quantum and relativistic revolutions in physics in the early 20 th century had a profound effect on methodology. Conceptual foundations of both theories were taken to show the defeasibility of even the most seemingly secure intuitions about space, time and bodies. Certainty of knowledge about the natural world was therefore recognized as unattainable. Instead a renewed empiricism was sought which rendered science fallible but still rationally justifiable.

Analyses of the reasoning of scientists emerged, according to which the aspects of scientific method which were of primary importance were the means of testing and confirming of theories. A distinction in methodology was made between the contexts of discovery and justification. The distinction could be used as a wedge between the particularities of where and how theories or hypotheses are arrived at, on the one hand, and the underlying reasoning scientists use (whether or not they are aware of it) when assessing theories and judging their adequacy on the basis of the available evidence. By and large, for most of the 20 th century, philosophy of science focused on the second context, although philosophers differed on whether to focus on confirmation or refutation as well as on the many details of how confirmation or refutation could or could not be brought about. By the mid-20 th century these attempts at defining the method of justification and the context distinction itself came under pressure. During the same period, philosophy of science developed rapidly, and from section 4 this entry will therefore shift from a primarily historical treatment of the scientific method towards a primarily thematic one.

Advances in logic and probability held out promise of the possibility of elaborate reconstructions of scientific theories and empirical method, the best example being Rudolf Carnap’s The Logical Structure of the World (1928). Carnap attempted to show that a scientific theory could be reconstructed as a formal axiomatic system—that is, a logic. That system could refer to the world because some of its basic sentences could be interpreted as observations or operations which one could perform to test them. The rest of the theoretical system, including sentences using theoretical or unobservable terms (like electron or force) would then either be meaningful because they could be reduced to observations, or they had purely logical meanings (called analytic, like mathematical identities). This has been referred to as the verifiability criterion of meaning. According to the criterion, any statement not either analytic or verifiable was strictly meaningless. Although the view was endorsed by Carnap in 1928, he would later come to see it as too restrictive (Carnap 1956). Another familiar version of this idea is operationalism of Percy William Bridgman. In The Logic of Modern Physics (1927) Bridgman asserted that every physical concept could be defined in terms of the operations one would perform to verify the application of that concept. Making good on the operationalisation of a concept even as simple as length, however, can easily become enormously complex (for measuring very small lengths, for instance) or impractical (measuring large distances like light years.)

Carl Hempel’s (1950, 1951) criticisms of the verifiability criterion of meaning had enormous influence. He pointed out that universal generalizations, such as most scientific laws, were not strictly meaningful on the criterion. Verifiability and operationalism both seemed too restrictive to capture standard scientific aims and practice. The tenuous connection between these reconstructions and actual scientific practice was criticized in another way. In both approaches, scientific methods are instead recast in methodological roles. Measurements, for example, were looked to as ways of giving meanings to terms. The aim of the philosopher of science was not to understand the methods per se , but to use them to reconstruct theories, their meanings, and their relation to the world. When scientists perform these operations, however, they will not report that they are doing them to give meaning to terms in a formal axiomatic system. This disconnect between methodology and the details of actual scientific practice would seem to violate the empiricism the Logical Positivists and Bridgman were committed to. The view that methodology should correspond to practice (to some extent) has been called historicism, or intuitionism. We turn to these criticisms and responses in section 3.4 . [ 4 ]

Positivism also had to contend with the recognition that a purely inductivist approach, along the lines of Bacon-Newton-Mill, was untenable. There was no pure observation, for starters. All observation was theory laden. Theory is required to make any observation, therefore not all theory can be derived from observation alone. (See the entry on theory and observation in science .) Even granting an observational basis, Hume had already pointed out that one could not deductively justify inductive conclusions without begging the question by presuming the success of the inductive method. Likewise, positivist attempts at analyzing how a generalization can be confirmed by observations of its instances were subject to a number of criticisms. Goodman (1965) and Hempel (1965) both point to paradoxes inherent in standard accounts of confirmation. Recent attempts at explaining how observations can serve to confirm a scientific theory are discussed in section 4 below.

The standard starting point for a non-inductive analysis of the logic of confirmation is known as the Hypothetico-Deductive (H-D) method. In its simplest form, a sentence of a theory which expresses some hypothesis is confirmed by its true consequences. As noted in section 2 , this method had been advanced by Whewell in the 19 th century, as well as Nicod (1924) and others in the 20 th century. Often, Hempel’s (1966) description of the H-D method, illustrated by the case of Semmelweiss’ inferential procedures in establishing the cause of childbed fever, has been presented as a key account of H-D as well as a foil for criticism of the H-D account of confirmation (see, for example, Lipton’s (2004) discussion of inference to the best explanation; also the entry on confirmation ). Hempel described Semmelsweiss’ procedure as examining various hypotheses explaining the cause of childbed fever. Some hypotheses conflicted with observable facts and could be rejected as false immediately. Others needed to be tested experimentally by deducing which observable events should follow if the hypothesis were true (what Hempel called the test implications of the hypothesis), then conducting an experiment and observing whether or not the test implications occurred. If the experiment showed the test implication to be false, the hypothesis could be rejected. If the experiment showed the test implications to be true, however, this did not prove the hypothesis true. The confirmation of a test implication does not verify a hypothesis, though Hempel did allow that “it provides at least some support, some corroboration or confirmation for it” (Hempel 1966: 8). The degree of this support then depends on the quantity, variety and precision of the supporting evidence.

Another approach that took off from the difficulties with inductive inference was Karl Popper’s critical rationalism or falsificationism (Popper 1959, 1963). Falsification is deductive and similar to H-D in that it involves scientists deducing observational consequences from the hypothesis under test. For Popper, however, the important point was not the degree of confirmation that successful prediction offered to a hypothesis. The crucial thing was the logical asymmetry between confirmation, based on inductive inference, and falsification, which can be based on a deductive inference. (This simple opposition was later questioned, by Lakatos, among others. See the entry on historicist theories of scientific rationality. )

Popper stressed that, regardless of the amount of confirming evidence, we can never be certain that a hypothesis is true without committing the fallacy of affirming the consequent. Instead, Popper introduced the notion of corroboration as a measure for how well a theory or hypothesis has survived previous testing—but without implying that this is also a measure for the probability that it is true.

Popper was also motivated by his doubts about the scientific status of theories like the Marxist theory of history or psycho-analysis, and so wanted to demarcate between science and pseudo-science. Popper saw this as an importantly different distinction than demarcating science from metaphysics. The latter demarcation was the primary concern of many logical empiricists. Popper used the idea of falsification to draw a line instead between pseudo and proper science. Science was science because its method involved subjecting theories to rigorous tests which offered a high probability of failing and thus refuting the theory.

A commitment to the risk of failure was important. Avoiding falsification could be done all too easily. If a consequence of a theory is inconsistent with observations, an exception can be added by introducing auxiliary hypotheses designed explicitly to save the theory, so-called ad hoc modifications. This Popper saw done in pseudo-science where ad hoc theories appeared capable of explaining anything in their field of application. In contrast, science is risky. If observations showed the predictions from a theory to be wrong, the theory would be refuted. Hence, scientific hypotheses must be falsifiable. Not only must there exist some possible observation statement which could falsify the hypothesis or theory, were it observed, (Popper called these the hypothesis’ potential falsifiers) it is crucial to the Popperian scientific method that such falsifications be sincerely attempted on a regular basis.

The more potential falsifiers of a hypothesis, the more falsifiable it would be, and the more the hypothesis claimed. Conversely, hypotheses without falsifiers claimed very little or nothing at all. Originally, Popper thought that this meant the introduction of ad hoc hypotheses only to save a theory should not be countenanced as good scientific method. These would undermine the falsifiabililty of a theory. However, Popper later came to recognize that the introduction of modifications (immunizations, he called them) was often an important part of scientific development. Responding to surprising or apparently falsifying observations often generated important new scientific insights. Popper’s own example was the observed motion of Uranus which originally did not agree with Newtonian predictions. The ad hoc hypothesis of an outer planet explained the disagreement and led to further falsifiable predictions. Popper sought to reconcile the view by blurring the distinction between falsifiable and not falsifiable, and speaking instead of degrees of testability (Popper 1985: 41f.).

From the 1960s on, sustained meta-methodological criticism emerged that drove philosophical focus away from scientific method. A brief look at those criticisms follows, with recommendations for further reading at the end of the entry.

Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) begins with a well-known shot across the bow for philosophers of science:

History, if viewed as a repository for more than anecdote or chronology, could produce a decisive transformation in the image of science by which we are now possessed. (1962: 1)

The image Kuhn thought needed transforming was the a-historical, rational reconstruction sought by many of the Logical Positivists, though Carnap and other positivists were actually quite sympathetic to Kuhn’s views. (See the entry on the Vienna Circle .) Kuhn shares with other of his contemporaries, such as Feyerabend and Lakatos, a commitment to a more empirical approach to philosophy of science. Namely, the history of science provides important data, and necessary checks, for philosophy of science, including any theory of scientific method.

The history of science reveals, according to Kuhn, that scientific development occurs in alternating phases. During normal science, the members of the scientific community adhere to the paradigm in place. Their commitment to the paradigm means a commitment to the puzzles to be solved and the acceptable ways of solving them. Confidence in the paradigm remains so long as steady progress is made in solving the shared puzzles. Method in this normal phase operates within a disciplinary matrix (Kuhn’s later concept of a paradigm) which includes standards for problem solving, and defines the range of problems to which the method should be applied. An important part of a disciplinary matrix is the set of values which provide the norms and aims for scientific method. The main values that Kuhn identifies are prediction, problem solving, simplicity, consistency, and plausibility.

An important by-product of normal science is the accumulation of puzzles which cannot be solved with resources of the current paradigm. Once accumulation of these anomalies has reached some critical mass, it can trigger a communal shift to a new paradigm and a new phase of normal science. Importantly, the values that provide the norms and aims for scientific method may have transformed in the meantime. Method may therefore be relative to discipline, time or place

Feyerabend also identified the aims of science as progress, but argued that any methodological prescription would only stifle that progress (Feyerabend 1988). His arguments are grounded in re-examining accepted “myths” about the history of science. Heroes of science, like Galileo, are shown to be just as reliant on rhetoric and persuasion as they are on reason and demonstration. Others, like Aristotle, are shown to be far more reasonable and far-reaching in their outlooks then they are given credit for. As a consequence, the only rule that could provide what he took to be sufficient freedom was the vacuous “anything goes”. More generally, even the methodological restriction that science is the best way to pursue knowledge, and to increase knowledge, is too restrictive. Feyerabend suggested instead that science might, in fact, be a threat to a free society, because it and its myth had become so dominant (Feyerabend 1978).

An even more fundamental kind of criticism was offered by several sociologists of science from the 1970s onwards who rejected the methodology of providing philosophical accounts for the rational development of science and sociological accounts of the irrational mistakes. Instead, they adhered to a symmetry thesis on which any causal explanation of how scientific knowledge is established needs to be symmetrical in explaining truth and falsity, rationality and irrationality, success and mistakes, by the same causal factors (see, e.g., Barnes and Bloor 1982, Bloor 1991). Movements in the Sociology of Science, like the Strong Programme, or in the social dimensions and causes of knowledge more generally led to extended and close examination of detailed case studies in contemporary science and its history. (See the entries on the social dimensions of scientific knowledge and social epistemology .) Well-known examinations by Latour and Woolgar (1979/1986), Knorr-Cetina (1981), Pickering (1984), Shapin and Schaffer (1985) seem to bear out that it was social ideologies (on a macro-scale) or individual interactions and circumstances (on a micro-scale) which were the primary causal factors in determining which beliefs gained the status of scientific knowledge. As they saw it therefore, explanatory appeals to scientific method were not empirically grounded.

A late, and largely unexpected, criticism of scientific method came from within science itself. Beginning in the early 2000s, a number of scientists attempting to replicate the results of published experiments could not do so. There may be close conceptual connection between reproducibility and method. For example, if reproducibility means that the same scientific methods ought to produce the same result, and all scientific results ought to be reproducible, then whatever it takes to reproduce a scientific result ought to be called scientific method. Space limits us to the observation that, insofar as reproducibility is a desired outcome of proper scientific method, it is not strictly a part of scientific method. (See the entry on reproducibility of scientific results .)

By the close of the 20 th century the search for the scientific method was flagging. Nola and Sankey (2000b) could introduce their volume on method by remarking that “For some, the whole idea of a theory of scientific method is yester-year’s debate …”.

Despite the many difficulties that philosophers encountered in trying to providing a clear methodology of conformation (or refutation), still important progress has been made on understanding how observation can provide evidence for a given theory. Work in statistics has been crucial for understanding how theories can be tested empirically, and in recent decades a huge literature has developed that attempts to recast confirmation in Bayesian terms. Here these developments can be covered only briefly, and we refer to the entry on confirmation for further details and references.

Statistics has come to play an increasingly important role in the methodology of the experimental sciences from the 19 th century onwards. At that time, statistics and probability theory took on a methodological role as an analysis of inductive inference, and attempts to ground the rationality of induction in the axioms of probability theory have continued throughout the 20 th century and in to the present. Developments in the theory of statistics itself, meanwhile, have had a direct and immense influence on the experimental method, including methods for measuring the uncertainty of observations such as the Method of Least Squares developed by Legendre and Gauss in the early 19 th century, criteria for the rejection of outliers proposed by Peirce by the mid-19 th century, and the significance tests developed by Gosset (a.k.a. “Student”), Fisher, Neyman & Pearson and others in the 1920s and 1930s (see, e.g., Swijtink 1987 for a brief historical overview; and also the entry on C.S. Peirce ).

These developments within statistics then in turn led to a reflective discussion among both statisticians and philosophers of science on how to perceive the process of hypothesis testing: whether it was a rigorous statistical inference that could provide a numerical expression of the degree of confidence in the tested hypothesis, or if it should be seen as a decision between different courses of actions that also involved a value component. This led to a major controversy among Fisher on the one side and Neyman and Pearson on the other (see especially Fisher 1955, Neyman 1956 and Pearson 1955, and for analyses of the controversy, e.g., Howie 2002, Marks 2000, Lenhard 2006). On Fisher’s view, hypothesis testing was a methodology for when to accept or reject a statistical hypothesis, namely that a hypothesis should be rejected by evidence if this evidence would be unlikely relative to other possible outcomes, given the hypothesis were true. In contrast, on Neyman and Pearson’s view, the consequence of error also had to play a role when deciding between hypotheses. Introducing the distinction between the error of rejecting a true hypothesis (type I error) and accepting a false hypothesis (type II error), they argued that it depends on the consequences of the error to decide whether it is more important to avoid rejecting a true hypothesis or accepting a false one. Hence, Fisher aimed for a theory of inductive inference that enabled a numerical expression of confidence in a hypothesis. To him, the important point was the search for truth, not utility. In contrast, the Neyman-Pearson approach provided a strategy of inductive behaviour for deciding between different courses of action. Here, the important point was not whether a hypothesis was true, but whether one should act as if it was.

Similar discussions are found in the philosophical literature. On the one side, Churchman (1948) and Rudner (1953) argued that because scientific hypotheses can never be completely verified, a complete analysis of the methods of scientific inference includes ethical judgments in which the scientists must decide whether the evidence is sufficiently strong or that the probability is sufficiently high to warrant the acceptance of the hypothesis, which again will depend on the importance of making a mistake in accepting or rejecting the hypothesis. Others, such as Jeffrey (1956) and Levi (1960) disagreed and instead defended a value-neutral view of science on which scientists should bracket their attitudes, preferences, temperament, and values when assessing the correctness of their inferences. For more details on this value-free ideal in the philosophy of science and its historical development, see Douglas (2009) and Howard (2003). For a broad set of case studies examining the role of values in science, see e.g. Elliott & Richards 2017.

In recent decades, philosophical discussions of the evaluation of probabilistic hypotheses by statistical inference have largely focused on Bayesianism that understands probability as a measure of a person’s degree of belief in an event, given the available information, and frequentism that instead understands probability as a long-run frequency of a repeatable event. Hence, for Bayesians probabilities refer to a state of knowledge, whereas for frequentists probabilities refer to frequencies of events (see, e.g., Sober 2008, chapter 1 for a detailed introduction to Bayesianism and frequentism as well as to likelihoodism). Bayesianism aims at providing a quantifiable, algorithmic representation of belief revision, where belief revision is a function of prior beliefs (i.e., background knowledge) and incoming evidence. Bayesianism employs a rule based on Bayes’ theorem, a theorem of the probability calculus which relates conditional probabilities. The probability that a particular hypothesis is true is interpreted as a degree of belief, or credence, of the scientist. There will also be a probability and a degree of belief that a hypothesis will be true conditional on a piece of evidence (an observation, say) being true. Bayesianism proscribes that it is rational for the scientist to update their belief in the hypothesis to that conditional probability should it turn out that the evidence is, in fact, observed (see, e.g., Sprenger & Hartmann 2019 for a comprehensive treatment of Bayesian philosophy of science). Originating in the work of Neyman and Person, frequentism aims at providing the tools for reducing long-run error rates, such as the error-statistical approach developed by Mayo (1996) that focuses on how experimenters can avoid both type I and type II errors by building up a repertoire of procedures that detect errors if and only if they are present. Both Bayesianism and frequentism have developed over time, they are interpreted in different ways by its various proponents, and their relations to previous criticism to attempts at defining scientific method are seen differently by proponents and critics. The literature, surveys, reviews and criticism in this area are vast and the reader is referred to the entries on Bayesian epistemology and confirmation .

5. Method in Practice

Attention to scientific practice, as we have seen, is not itself new. However, the turn to practice in the philosophy of science of late can be seen as a correction to the pessimism with respect to method in philosophy of science in later parts of the 20 th century, and as an attempted reconciliation between sociological and rationalist explanations of scientific knowledge. Much of this work sees method as detailed and context specific problem-solving procedures, and methodological analyses to be at the same time descriptive, critical and advisory (see Nickles 1987 for an exposition of this view). The following section contains a survey of some of the practice focuses. In this section we turn fully to topics rather than chronology.

A problem with the distinction between the contexts of discovery and justification that figured so prominently in philosophy of science in the first half of the 20 th century (see section 2 ) is that no such distinction can be clearly seen in scientific activity (see Arabatzis 2006). Thus, in recent decades, it has been recognized that study of conceptual innovation and change should not be confined to psychology and sociology of science, but are also important aspects of scientific practice which philosophy of science should address (see also the entry on scientific discovery ). Looking for the practices that drive conceptual innovation has led philosophers to examine both the reasoning practices of scientists and the wide realm of experimental practices that are not directed narrowly at testing hypotheses, that is, exploratory experimentation.

Examining the reasoning practices of historical and contemporary scientists, Nersessian (2008) has argued that new scientific concepts are constructed as solutions to specific problems by systematic reasoning, and that of analogy, visual representation and thought-experimentation are among the important reasoning practices employed. These ubiquitous forms of reasoning are reliable—but also fallible—methods of conceptual development and change. On her account, model-based reasoning consists of cycles of construction, simulation, evaluation and adaption of models that serve as interim interpretations of the target problem to be solved. Often, this process will lead to modifications or extensions, and a new cycle of simulation and evaluation. However, Nersessian also emphasizes that

creative model-based reasoning cannot be applied as a simple recipe, is not always productive of solutions, and even its most exemplary usages can lead to incorrect solutions. (Nersessian 2008: 11)

Thus, while on the one hand she agrees with many previous philosophers that there is no logic of discovery, discoveries can derive from reasoned processes, such that a large and integral part of scientific practice is

the creation of concepts through which to comprehend, structure, and communicate about physical phenomena …. (Nersessian 1987: 11)

Similarly, work on heuristics for discovery and theory construction by scholars such as Darden (1991) and Bechtel & Richardson (1993) present science as problem solving and investigate scientific problem solving as a special case of problem-solving in general. Drawing largely on cases from the biological sciences, much of their focus has been on reasoning strategies for the generation, evaluation, and revision of mechanistic explanations of complex systems.

Addressing another aspect of the context distinction, namely the traditional view that the primary role of experiments is to test theoretical hypotheses according to the H-D model, other philosophers of science have argued for additional roles that experiments can play. The notion of exploratory experimentation was introduced to describe experiments driven by the desire to obtain empirical regularities and to develop concepts and classifications in which these regularities can be described (Steinle 1997, 2002; Burian 1997; Waters 2007)). However the difference between theory driven experimentation and exploratory experimentation should not be seen as a sharp distinction. Theory driven experiments are not always directed at testing hypothesis, but may also be directed at various kinds of fact-gathering, such as determining numerical parameters. Vice versa , exploratory experiments are usually informed by theory in various ways and are therefore not theory-free. Instead, in exploratory experiments phenomena are investigated without first limiting the possible outcomes of the experiment on the basis of extant theory about the phenomena.

The development of high throughput instrumentation in molecular biology and neighbouring fields has given rise to a special type of exploratory experimentation that collects and analyses very large amounts of data, and these new ‘omics’ disciplines are often said to represent a break with the ideal of hypothesis-driven science (Burian 2007; Elliott 2007; Waters 2007; O’Malley 2007) and instead described as data-driven research (Leonelli 2012; Strasser 2012) or as a special kind of “convenience experimentation” in which many experiments are done simply because they are extraordinarily convenient to perform (Krohs 2012).

5.2 Computer methods and ‘new ways’ of doing science

The field of omics just described is possible because of the ability of computers to process, in a reasonable amount of time, the huge quantities of data required. Computers allow for more elaborate experimentation (higher speed, better filtering, more variables, sophisticated coordination and control), but also, through modelling and simulations, might constitute a form of experimentation themselves. Here, too, we can pose a version of the general question of method versus practice: does the practice of using computers fundamentally change scientific method, or merely provide a more efficient means of implementing standard methods?