How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

How to Write a Master's Thesis

- Yvonne N. Bui - San Francisco State University, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“Yvonne Bui’s How to Write a Master’s Thesis should be mandatory for all thesis track master’s students. It steers students away from the shortcuts students may be tempted to use that would be costly in the long run. The step by step intentional approach is what I like best about this book.”

“This is the best textbook about writing an M.A. thesis available in the market.”

“This is the type of textbook that students keep and refer to after the class.”

Excellent book. Thorough, yet concise, information for students writing their Master's Thesis who may not have had a strong background in research.

Clear, Concise, easy for students to access and understand. Contains all the elements for a successful thesis.

I loved the ease of this book. It was clear without extra nonsense that would just confuse the students.

Clear, concise, easily accessible. Students find it of great value.

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- Concrete instruction and guides for conceptualizing the literature review help students navigate through the most challenging topics.

- Step-by-step instructions and more screenshots give students the guidance they need to write the foundational chapter, along with the latest online resources and general library information.

- Additional coverage of single case designs and mixed methods help students gain a more comprehensive understanding of research methods.

- Expanded explanation of unintentional plagiarism within the ethics chapter shows students the path to successful and professional writing.

- Detailed information on conference presentation as a way to disseminate research , in addition to getting published, help students understand all of the tools needed to write a master’s thesis.

KEY FEATURES:

- An advanced chapter organizer provides an up-front checklist of what to expect in the chapter and serves as a project planner, so that students can immediately prepare and work alongside the chapter as they begin to develop their thesis.

- Full guidance on conducting successful literature reviews includes up-to-date information on electronic databases and Internet tools complete with numerous figures and captured screen shots from relevant web sites, electronic databases, and SPSS software, all integrated with the text.

- Excerpts from research articles and samples from exemplary students' master's theses relate specifically to the content of each chapter and provide the reader with a real-world context.

- Detailed explanations of the various components of the master's thesis and concrete strategies on how to conduct a literature review help students write each chapter of the master's thesis, and apply the American Psychological Association (APA) editorial style.

- A comprehensive Resources section features "Try It!" boxes which lead students through a sample problem or writing exercise based on a piece of the thesis to reinforce prior course learning and the writing objectives at hand. Reflection/discussion questions in the same section are designed to help students work through the thesis process.

Sample Materials & Chapters

1: Overview of the Master's Degree and Thesis

3: Using the Literature to Research Your Problem

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation | A Guide to Structure & Content

A dissertation or thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on original research, submitted as part of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

The structure of a dissertation depends on your field, but it is usually divided into at least four or five chapters (including an introduction and conclusion chapter).

The most common dissertation structure in the sciences and social sciences includes:

- An introduction to your topic

- A literature review that surveys relevant sources

- An explanation of your methodology

- An overview of the results of your research

- A discussion of the results and their implications

- A conclusion that shows what your research has contributed

Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an argument by analysing primary and secondary sources . Instead of the standard structure outlined here, you might organise your chapters around different themes or case studies.

Other important elements of the dissertation include the title page , abstract , and reference list . If in doubt about how your dissertation should be structured, always check your department’s guidelines and consult with your supervisor.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements, table of contents, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review / theoretical framework, methodology, reference list.

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation’s title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo. Many programs have strict requirements for formatting the dissertation title page .

The title page is often used as cover when printing and binding your dissertation .

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

The acknowledgements section is usually optional, and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you.

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150-300 words long. You should write it at the very end, when you’ve completed the rest of the dissertation. In the abstract, make sure to:

- State the main topic and aims of your research

- Describe the methods you used

- Summarise the main results

- State your conclusions

Although the abstract is very short, it’s the first part (and sometimes the only part) of your dissertation that people will read, so it’s important that you get it right. If you’re struggling to write a strong abstract, read our guide on how to write an abstract .

In the table of contents, list all of your chapters and subheadings and their page numbers. The dissertation contents page gives the reader an overview of your structure and helps easily navigate the document.

All parts of your dissertation should be included in the table of contents, including the appendices. You can generate a table of contents automatically in Word.

If you have used a lot of tables and figures in your dissertation, you should itemise them in a numbered list . You can automatically generate this list using the Insert Caption feature in Word.

If you have used a lot of abbreviations in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

If you have used a lot of highly specialised terms that will not be familiar to your reader, it might be a good idea to include a glossary . List the terms alphabetically and explain each term with a brief description or definition.

In the introduction, you set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance, and tell the reader what to expect in the rest of the dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving necessary background information to contextualise your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of the research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your objectives and research questions , and indicate how you will answer them

- Give an overview of your dissertation’s structure

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant to your research. By the end, the reader should understand the what , why and how of your research. Not sure how? Read our guide on how to write a dissertation introduction .

Before you start on your research, you should have conducted a literature review to gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic. This means:

- Collecting sources (e.g. books and journal articles) and selecting the most relevant ones

- Critically evaluating and analysing each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g. themes, patterns, conflicts, gaps) to make an overall point

In the dissertation literature review chapter or section, you shouldn’t just summarise existing studies, but develop a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear basis or justification for your own research. For example, it might aim to show how your research:

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Takes a new theoretical or methodological approach to the topic

- Proposes a solution to an unresolved problem

- Advances a theoretical debate

- Builds on and strengthens existing knowledge with new data

The literature review often becomes the basis for a theoretical framework , in which you define and analyse the key theories, concepts and models that frame your research. In this section you can answer descriptive research questions about the relationship between concepts or variables.

The methodology chapter or section describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to assess its validity. You should generally include:

- The overall approach and type of research (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, ethnographic)

- Your methods of collecting data (e.g. interviews, surveys, archives)

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Your methods of analysing data (e.g. statistical analysis, discourse analysis)

- Tools and materials you used (e.g. computer programs, lab equipment)

- A discussion of any obstacles you faced in conducting the research and how you overcame them

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Your aim in the methodology is to accurately report what you did, as well as convincing the reader that this was the best approach to answering your research questions or objectives.

Next, you report the results of your research . You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses, or topics. Only report results that are relevant to your objectives and research questions. In some disciplines, the results section is strictly separated from the discussion, while in others the two are combined.

For example, for qualitative methods like in-depth interviews, the presentation of the data will often be woven together with discussion and analysis, while in quantitative and experimental research, the results should be presented separately before you discuss their meaning. If you’re unsure, consult with your supervisor and look at sample dissertations to find out the best structure for your research.

In the results section it can often be helpful to include tables, graphs and charts. Think carefully about how best to present your data, and don’t include tables or figures that just repeat what you have written – they should provide extra information or usefully visualise the results in a way that adds value to your text.

Full versions of your data (such as interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix .

The discussion is where you explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research questions. Here you should interpret the results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data and discuss any limitations that might have influenced the results.

The discussion should reference other scholarly work to show how your results fit with existing knowledge. You can also make recommendations for future research or practical action.

The dissertation conclusion should concisely answer the main research question, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your central argument. Wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you did and how you did it. The conclusion often also includes recommendations for research or practice.

In this section, it’s important to show how your findings contribute to knowledge in the field and why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known?

You must include full details of all sources that you have cited in a reference list (sometimes also called a works cited list or bibliography). It’s important to follow a consistent reference style . Each style has strict and specific requirements for how to format your sources in the reference list.

The most common styles used in UK universities are Harvard referencing and Vancouver referencing . Your department will often specify which referencing style you should use – for example, psychology students tend to use APA style , humanities students often use MHRA , and law students always use OSCOLA . M ake sure to check the requirements, and ask your supervisor if you’re unsure.

To save time creating the reference list and make sure your citations are correctly and consistently formatted, you can use our free APA Citation Generator .

Your dissertation itself should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents you have used that do not fit into the main body of your dissertation (such as interview transcripts, survey questions or tables with full figures) can be added as appendices .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation binding and printing

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- Dissertation title page

- Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

- Figure & Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Resources for Dissertation Writing

- Getting Started

- Proposals and Prospectuses

- Literature Reviews

- Humanities and the Arts Resources

- Social/Behavioural Sciences Resources

- Sciences Resources

- Business Resources

- Formatting and Submitting Your Dissertation

- Tips: Making Progress, Staying Well, and More!

UBC Library Research Commons

About This Section of the Guide

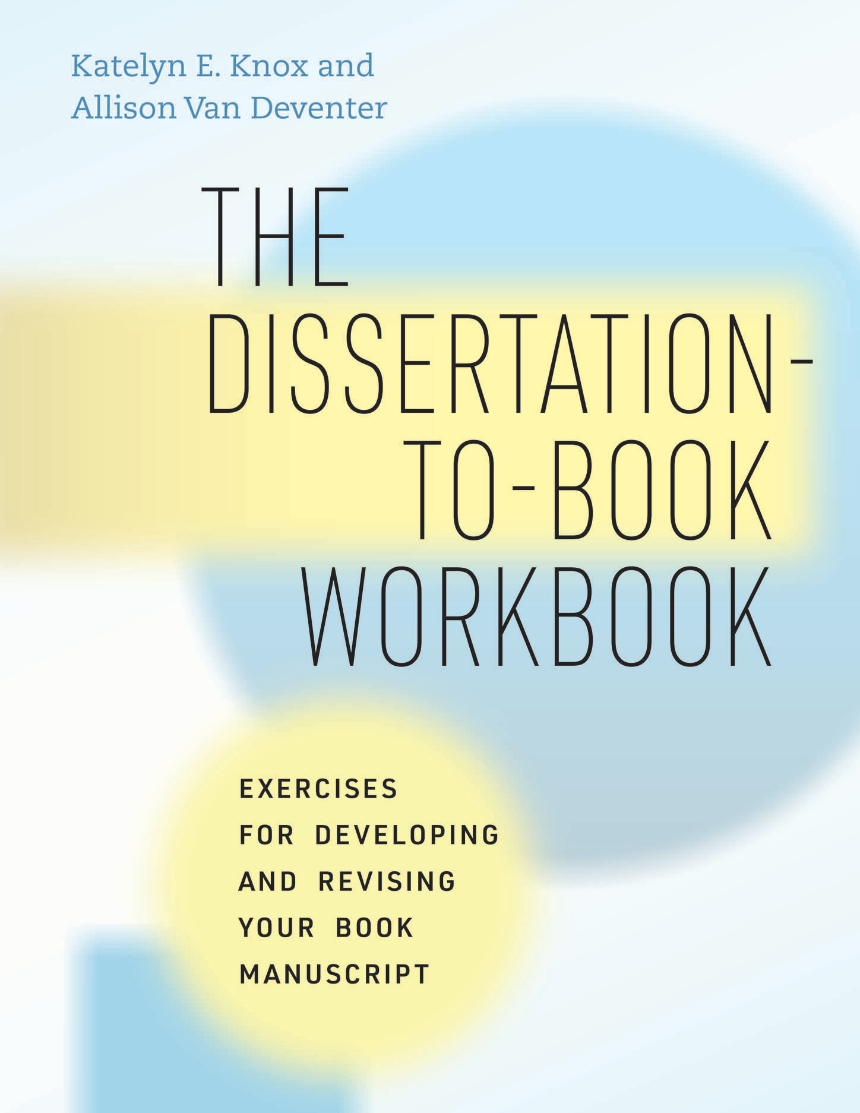

In this section, UBC Research Commons staff have compiled a number of books available through UBC Library that might help you in your dissertation writing. In addition to the general books on this page, there are also pages with books related to writing in the Humanities and the Arts , the Social and Behavioural Sciences , the Sciences , and Business . For disciplines that fall under more than one of these broad areas, such as education or social work, we've included the books in all the broad disciplines that seem to be most appropriate.

If there's a book you've used that doesn't appear on any of these pages, please e-mail us and let us know!

General Dissertation Writing Books and E-Books

Older Books and E-Books

These books may be somewhat dated now, but can still provide useful tips for writing theses and dissertations.

- << Previous: Literature Reviews

- Next: Humanities and the Arts Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 23, 2021 9:58 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ubc.ca/dissertation

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Guide to Thesis Writing That Is a Guide to Life

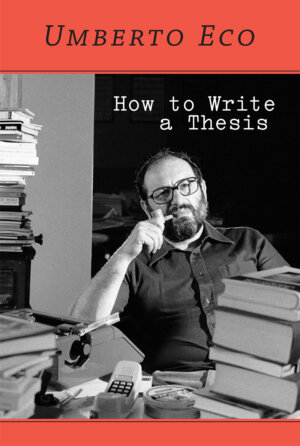

“How to Write a Thesis,” by Umberto Eco, first appeared on Italian bookshelves in 1977. For Eco, the playful philosopher and novelist best known for his work on semiotics, there was a practical reason for writing it. Up until 1999, a thesis of original research was required of every student pursuing the Italian equivalent of a bachelor’s degree. Collecting his thoughts on the thesis process would save him the trouble of reciting the same advice to students each year. Since its publication, “How to Write a Thesis” has gone through twenty-three editions in Italy and has been translated into at least seventeen languages. Its first English edition is only now available, in a translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina.

We in the English-speaking world have survived thirty-seven years without “How to Write a Thesis.” Why bother with it now? After all, Eco wrote his thesis-writing manual before the advent of widespread word processing and the Internet. There are long passages devoted to quaint technologies such as note cards and address books, careful strategies for how to overcome the limitations of your local library. But the book’s enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it’s about what, in Eco’s rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one’s early twenties. “Your thesis,” Eco foretells, “is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.” By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Eco’s career has been defined by a desire to share the rarefied concerns of academia with a broader reading public. He wrote a novel that enacted literary theory (“The Name of the Rose”) and a children’s book about atoms conscientiously objecting to their fate as war machines (“The Bomb and the General”). “How to Write a Thesis” is sparked by the wish to give any student with the desire and a respect for the process the tools for producing a rigorous and meaningful piece of writing. “A more just society,” Eco writes at the book’s outset, would be one where anyone with “true aspirations” would be supported by the state, regardless of their background or resources. Our society does not quite work that way. It is the students of privilege, the beneficiaries of the best training available, who tend to initiate and then breeze through the thesis process.

Eco walks students through the craft and rewards of sustained research, the nuances of outlining, different systems for collating one’s research notes, what to do if—per Eco’s invocation of thesis-as-first-love—you fear that someone’s made all these moves before. There are broad strategies for laying out the project’s “center” and “periphery” as well as philosophical asides about originality and attribution. “Work on a contemporary author as if he were ancient, and an ancient one as if he were contemporary,” Eco wisely advises. “You will have more fun and write a better thesis.” Other suggestions may strike the modern student as anachronistic, such as the novel idea of using an address book to keep a log of one’s sources.

But there are also old-fashioned approaches that seem more useful than ever: he recommends, for instance, a system of sortable index cards to explore a project’s potential trajectories. Moments like these make “How to Write a Thesis” feel like an instruction manual for finding one’s center in a dizzying era of information overload. Consider Eco’s caution against “the alibi of photocopies”: “A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many.” Many of us suffer from an accelerated version of this nowadays, as we effortlessly bookmark links or save articles to Instapaper, satisfied with our aspiration to hoard all this new information, unsure if we will ever get around to actually dealing with it. (Eco’s not-entirely-helpful solution: read everything as soon as possible.)

But the most alluring aspect of Eco’s book is the way he imagines the community that results from any honest intellectual endeavor—the conversations you enter into across time and space, across age or hierarchy, in the spirit of free-flowing, democratic conversation. He cautions students against losing themselves down a narcissistic rabbit hole: you are not a “defrauded genius” simply because someone else has happened upon the same set of research questions. “You must overcome any shyness and have a conversation with the librarian,” he writes, “because he can offer you reliable advice that will save you much time. You must consider that the librarian (if not overworked or neurotic) is happy when he can demonstrate two things: the quality of his memory and erudition and the richness of his library, especially if it is small. The more isolated and disregarded the library, the more the librarian is consumed with sorrow for its underestimation.”

Eco captures a basic set of experiences and anxieties familiar to anyone who has written a thesis, from finding a mentor (“How to Avoid Being Exploited By Your Advisor”) to fighting through episodes of self-doubt. Ultimately, it’s the process and struggle that make a thesis a formative experience. When everything else you learned in college is marooned in the past—when you happen upon an old notebook and wonder what you spent all your time doing, since you have no recollection whatsoever of a senior-year postmodernism seminar—it is the thesis that remains, providing the once-mastered scholarly foundation that continues to authorize, decades-later, barroom observations about the late-career works of William Faulker or the Hotelling effect. (Full disclosure: I doubt that anyone on Earth can rival my mastery of John Travolta’s White Man’s Burden, owing to an idyllic Berkeley spring spent studying awful movies about race.)

In his foreword to Eco’s book, the scholar Francesco Erspamer contends that “How to Write a Thesis” continues to resonate with readers because it gets at “the very essence of the humanities.” There are certainly reasons to believe that the current crisis of the humanities owes partly to the poor job they do of explaining and justifying themselves. As critics continue to assail the prohibitive cost and possible uselessness of college—and at a time when anything that takes more than a few minutes to skim is called a “longread”—it’s understandable that devoting a small chunk of one’s frisky twenties to writing a thesis can seem a waste of time, outlandishly quaint, maybe even selfish. And, as higher education continues to bend to the logic of consumption and marketable skills, platitudes about pursuing knowledge for its own sake can seem certifiably bananas. Even from the perspective of the collegiate bureaucracy, the thesis is useful primarily as another mode of assessment, a benchmark of student achievement that’s legible and quantifiable. It’s also a great parting reminder to parents that your senior learned and achieved something.

But “How to Write a Thesis” is ultimately about much more than the leisurely pursuits of college students. Writing and research manuals such as “The Elements of Style,” “The Craft of Research,” and Turabian offer a vision of our best selves. They are exacting and exhaustive, full of protocols and standards that might seem pretentious, even strange. Acknowledging these rules, Eco would argue, allows the average person entry into a veritable universe of argument and discussion. “How to Write a Thesis,” then, isn’t just about fulfilling a degree requirement. It’s also about engaging difference and attempting a project that is seemingly impossible, humbly reckoning with “the knowledge that anyone can teach us something.” It models a kind of self-actualization, a belief in the integrity of one’s own voice.

A thesis represents an investment with an uncertain return, mostly because its life-changing aspects have to do with process. Maybe it’s the last time your most harebrained ideas will be taken seriously. Everyone deserves to feel this way. This is especially true given the stories from many college campuses about the comparatively lower number of women, first-generation students, and students of color who pursue optional thesis work. For these students, part of the challenge involves taking oneself seriously enough to ask for an unfamiliar and potentially path-altering kind of mentorship.

It’s worth thinking through Eco’s evocation of a “just society.” We might even think of the thesis, as Eco envisions it, as a formal version of the open-mindedness, care, rigor, and gusto with which we should greet every new day. It’s about committing oneself to a task that seems big and impossible. In the end, you won’t remember much beyond those final all-nighters, the gauche inside joke that sullies an acknowledgments page that only four human beings will ever read, the awkward photograph with your advisor at graduation. All that remains might be the sensation of handing your thesis to someone in the departmental office and then walking into a possibility-rich, almost-summer afternoon. It will be difficult to forget.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mary Norris

By Joshua Rothman

By Richard Brody

By Katy Waldman

- Writing, Research & Publishing Guides

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $20.08 $ 20 . 08 FREE delivery Tuesday, June 4 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $14.96 $ 14 . 96 FREE delivery Wednesday, June 5 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Murfbooks

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day: A Guide to Starting, Revising, and Finishing Your Doctoral Thesis Paperback – August 15, 1998

Purchase options and add-ons.

Expert writing advice from the editor of the Boston Globe best-seller, The Writer's Home Companion

Dissertation writers need strong, practical advice, as well as someone to assure them that their struggles aren't unique. Joan Bolker, midwife to more than one hundred dissertations and co-founder of the Harvard Writing Center, offers invaluable suggestions for the graduate-student writer. Using positive reinforcement, she begins by reminding thesis writers that being able to devote themselves to a project that truly interests them can be a pleasurable adventure. She encourages them to pay close attention to their writing method in order to discover their individual work strategies that promote productivity; to stop feeling fearful that they may disappoint their advisors or family members; and to tailor their theses to their own writing style and personality needs. Using field-tested strategies she assists the student through the entire thesis-writing process, offering advice on choosing a topic and an advisor, on disciplining one's self to work at least fifteen minutes each day; setting short-term deadlines, on revising and defing the thesis, and on life and publication after the dissertation. Bolker makes writing the dissertation an enjoyable challenge.

- Print length 184 pages

- Language English

- Publication date August 15, 1998

- Dimensions 5.5 x 0.52 x 8.25 inches

- ISBN-10 080504891X

- ISBN-13 978-0805048919

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Editorial Reviews

Amazon.com review.

While some of the book's advice is of interest only to dissertation writers, much of the information--on battling writer's block, for instance--is valuable to anybody engaged in writing. Rather than being filled with rules defining how to become a great writer, Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day is about finding the process by which you can be the most productive--it's a set of exercises that you can use to find out more about you and the way you write. Along the way, you'll do a bit of writing. And that's what matters, especially when you experience writer's block--as Bolker says, "Write anything, because writing is writing." With its helpful advice and supportive tone, Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day should be required reading for anyone considering writing a dissertation. --C.B. Delaney

About the Author

Editor of the best-selling The Writers Home Companion , Joan Bolker, Ed.D ., has taught writing at Harvard, Wellesley, Brandeis, and Bard colleges. She is currently a psychotherapist whose speciality is working with struggling writers. She lives in Newton, Massachusetts.

Product details

- Publisher : Owl Books; First Edition (August 15, 1998)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 184 pages

- ISBN-10 : 080504891X

- ISBN-13 : 978-0805048919

- Item Weight : 7.2 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 0.52 x 8.25 inches

- #29 in Research Reference Books

- #125 in Writing Skill Reference (Books)

- #215 in Fiction Writing Reference (Books)

About the author

Joan bolker.

Joan Bolker, Ed.D., has taught and counseled writers at Harvard, where she cofounded the Writing Center; at University of Massachusetts, Boston, where she began The Language Place; and at Wellesley, Brandeis, and M.I.T., where she was a psyco-therapist and writing consultant. She has coached the authors of more than one hundred doctoral dissertations and is currently a clinical psychologist who works with many writers in her private practice. She is the author of Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

How to Write a Thesis, According to Umberto Eco

In 1977, three years before Umberto Eco’s groundbreaking novel “ The Name of the Rose ” catapulted him to international fame, the illustrious semiotician published a funny and unpretentious guide for his favorite audience: teachers and their students. Now translated into 17 languages (it finally appeared in English in 2015), “How to Write a Thesis” delivers not just practical advice for writing a thesis — from choosing the right topic (monograph or survey? ancient or contemporary?) to note-taking and mastering the final draft — but meaningful lessons that equip writers for a lifetime outside the walls of the classroom. “Your thesis is like your first love” Eco muses. “It will be difficult to forget. In the end, it will represent your first serious and rigorous academic work, and this is no small thing.”

“Full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it,” praised one critic, “the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own.” An excerpt from that chapter can be read below.

Once we have decided to whom to write (to humanity, not to the advisor), we must decide how to write, and this is quite a difficult question. If there were exhaustive rules, we would all be great writers. I could at least recommend that you rewrite your thesis many times, or that you take on other writing projects before embarking on your thesis, because writing is also a question of training. In any case, I will provide some general suggestions:

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

The pianist Wittgenstein, brother of the well-known philosopher who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicusthat today many consider the masterpiece of contemporary philosophy, happened to have Ravel write for him a concerto for the left hand, since he had lost the right one in the war.

Write instead,

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Since Paul was maimed of his right hand, the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the famous philosopher, author of the Tractatus. The pianist had lost his right hand in the war. For this reason the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

Do not write,

The Irish writer had renounced family, country, and church, and stuck to his plans. It can hardly be said of him that he was a politically committed writer, even if some have mentioned Fabian and “socialist” inclinations with respect to him. When World War II erupted, he tended to deliberately ignore the tragedy that shook Europe, and he was preoccupied solely with the writing of his last work.

Rather write,

Joyce had renounced family, country, and church. He stuck to his plans. We cannot say that Joyce was a “politically committed” writer even if some have gone so far as describing a Fabian and “socialist” Joyce. When World War II erupted, Joyce deliberately ignored the tragedy that shook Europe. His sole preoccupation was the writing of Finnegans Wake.

Even if it seems “literary,” please do not write,

When Stockhausen speaks of “clusters,” he does not have in mind Schoenberg’s series, or Webern’s series. If confronted, the German musician would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the series has ended. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. On the other hand Webern followed the strict principles of the author of A Survivor from Warsaw. Now, the author of Mantra goes well beyond. And as for the former, it is necessary to distinguish between the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio agrees: it is not possible to consider this author as a dogmatic serialist.

You will notice that, at some point, you can no longer tell who is who. In addition, defining an author through one of his works is logically incorrect. It is true that lesser critics refer to Alessandro Manzoni simply as “the author of the Betrothed,” perhaps for fear of repeating his name too many times. (This is something manuals on formal writing apparently advise against.) But the author of The Betrothed is not the biographical character Manzoni in his totality. In fact, in a certain context we could say that there is a notable difference between the author of The Betrothed and the author of Adelchi , even if they are one and the same biographically speaking and according to their birth certificate. For this reason, I would rewrite the above passage as follows:

When Stockhausen speaks of a “cluster,” he does not have in mind either the series of Schoenberg or that of Webern. If confronted, Stockhausen would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the end of the series. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. Webern, by contrast, followed the strict principles of Schoenberg, but Stockhausen goes well beyond. And even for Webern, it is necessary to distinguish among the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio also asserts that it is not possible to think of Webern as a dogmatic serialist.

You are not e. e. cummings. Cummings was an American avant-garde poet who is known for having signed his name with lower-case initials. Naturally he used commas and periods with great thriftiness, he broke his lines into small pieces, and in short he did all the things that an avant-garde poet can and should do. But you are not an avant-garde poet. Not even if your thesis is on avant-garde poetry. If you write a thesis on Caravaggio, are you then a painter? And if you write a thesis on the style of the futurists, please do not write as a futurist writes. This is important advice because nowadays many tend to write “alternative” theses, in which the rules of critical discourse are not respected. But the language of the thesis is a metalanguage , that is, a language that speaks of other languages. A psychiatrist who describes the mentally ill does not express himself in the manner of his patients. I am not saying that it is wrong to express oneself in the manner of the so-called mentally ill. In fact, you could reasonably argue that they are the only ones who express themselves the way one should. But here you have two choices: either you do not write a thesis, and you manifest your desire to break with tradition by refusing to earn your degree, perhaps learning to play the guitar instead; or you write your thesis, but then you must explain to everyone why the language of the mentally ill is not a “crazy” language, and to do it you must use a metalanguage intelligible to all. The pseudo-poet who writes his thesis in poetry is a pitiful writer (and probably a bad poet). From Dante to Eliot and from Eliot to Sanguineti, when avant-garde poets wanted to talk about their poetry, they wrote in clear prose. And when Marx wanted to talk about workers, he did not write as a worker of his time, but as a philosopher. Then, when he wrote The Communist Manifesto with Engels in 1848, he used a fragmented journalistic style that was provocative and quite effective. Yet again, The Communist Manifesto is not written in the style of Capital, a text addressed to economists and politicians. Do not pretend to be Dante by saying that the poetic fury “dictates deep within,” and that you cannot surrender to the flat and pedestrian metalanguage of literary criticism. Are you a poet? Then do not pursue a university degree. Twentieth-century Italian poet Eugenio Montale does not have a degree, and he is a great poet nonetheless. His contemporary Carlo Emilio Gadda (who held a degree in engineering) wrote fiction in a unique style, full of dialects and stylistic idiosyncrasies; but when he wrote a manual for radio news writers, he wrote a clever, sharp, and lucid “recipe book” full of clear and accessible prose. And when Montale writes a critical article, he writes so that all can understand him, including those who do not understand his poems.

Begin new paragraphs often. Do so when logically necessary, and when the pace of the text requires it, but the more you do it, the better.

Write everything that comes into your head , but only in the first draft. You may notice that you get carried away with your inspiration, and you lose track of the center of your topic. In this case, you can remove the parenthetical sentences and the digressions, or you can put each in a note or an appendix. Your thesis exists to prove the hypothesis that you devised at the outset, not to show the breadth of your knowledge.

Use the advisor as a guinea pig. You must ensure that the advisor reads the first chapters (and eventually, all the chapters) far in advance of the deadline. His reactions may be useful to you. If the advisor is busy (or lazy), ask a friend. Ask if he understands what you are writing. Do not play the solitary genius.

Do not insist on beginning with the first chapter . Perhaps you have more documentation on chapter 4. Start there, with the nonchalance of someone who has already worked out the previous chapters. You will gain confidence. Naturally your working table of contents will anchor you, and will serve as a hypothesis that guides you.

Do not use ellipsis and exclamation points, and do not explain ironies . It is possible to use language that is referential or language that is figurative . By referential language, I mean a language that is recognized by all, in which all things are called by their most common name, and that does not lend itself to misunderstandings. “The Venice-Milan train” indicates in a referential way the same object that “The Arrow of the Lagoon” indicates figuratively. This example illustrates that “everyday” communication is possible with partially figurative language. Ideally, a critical essay or a scholarly text should be written referentially (with all terms well defined and univocal), but it can also be useful to use metaphor, irony, or litotes. Here is a referential text, followed by its transcription in figurative terms that are at least tolerable:

[ Referential version :] Krasnapolsky is not a very sharp critic of Danieli’s work. His interpretation draws meaning from the author’s text that the author probably did not intend. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky sees a symbolic expression that alludes to poetic activity. One should not trust Ritz’s critical acumen, and one should also distrust Krasnapolsky. Hilton observes that, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he adds, “Truly, two perfect critics.”

[ Figurative version :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the sharpest critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is putting words into Danieli’s mouth. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets it as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky plays the symbolism card and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight, but Krasnapolsky should also be handled with care. As Hilton observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon. Truly, two perfect critics.”

You can see that the figurative version uses various rhetorical devices. First of all, the litotes: saying that you are not convinced that someone is a sharp critic means that you are convinced that he is not a sharp critic. Also, the statement “Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight” means that he is a modest critic. Then there are the metaphors : putting words into someone’s mouth, and playing the symbolism card. The tourist brochure and the Lenten sermon are two similes , while the observation that the two authors are perfect critics is an example of irony : saying one thing to signify its opposite.

Now, we either use rhetorical figures effectively, or we do not use them at all. If we use them it is because we presume our reader is capable of catching them, and because we believe that we will appear more incisive and convincing. In this case, we should not be ashamed of them, and we should not explain them . If we think that our reader is an idiot, we should not use rhetorical figures, but if we use them and feel the need to explain them, we are essentially calling the reader an idiot. In turn, he will take revenge by calling the author an idiot. Here is how a timid writer might intervene to neutralize and excuse the rhetorical figures he uses:

[ Figurative version with reservations :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the “sharpest” critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is “putting words into Danieli’s mouth.” Consider Danieli’s line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky “plays the symbolism card” and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a “prodigy of critical insight,” but Krasnapolsky should also be “handled with care”! As Hilton ironically observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a vacation brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he defines them (again with irony!) as two models of critical perfection. But all joking aside …

I am convinced that nobody could be so intellectually petit bourgeois as to conceive a passage so studded with shyness and apologetic little smiles. Of course I exaggerated in this example, and here I say that I exaggerated because it is didactically important that the parody be understood as such. In fact, many bad habits of the amateur writer are condensed into this third example. First of all, the use of quotation marks to warn the reader, “Pay attention because I am about to say something big!” Puerile. Quotation marks are generally only used to designate a direct quotation or the title of an essay or short work; to indicate that a term is jargon or slang; or that a term is being discussed in the text as a word, rather than used functionally within the sentence. Secondly, the use of the exclamation point to emphasize a statement. This is not appropriate in a critical essay. If you check the book you are reading, you will notice that I have used the exclamation mark only once or twice. It is allowed once or twice, if the purpose is to make the reader jump in his seat and call his attention to a vehement statement like, “Pay attention, never make this mistake!” But it is a good rule to speak softly. The effect will be stronger if you simply say important things. Finally, the author of the third passage draws attention to the ironies, and apologizes for using them (even if they are someone else’s). Surely, if you think that Hilton’s irony is too subtle, you can write, “Hilton states with subtle irony that we are in the presence of two perfect critics.” But the irony must be really subtle to merit such a statement. In the quoted text, after Hilton has mentioned the vacation brochure and the Lenten sermon, the irony was already evident and needed no further explanation. The same applies to the statement, “But all joking aside.” Sometimes a statement like this can be useful to abruptly change the tone of the argument, but only if you were really joking before. In this case, the author was not joking. He was attempting to use irony and metaphor, but these are serious rhetorical devices and not jokes.

You may observe that, more than once in this book, I have expressed a paradox and then warned that it was a paradox. For example, in section 2.6.1, I proposed the existence of the mythical centaur for the purpose of explaining the concept of scientific research. But I warned you of this paradox not because I thought you would have believed this proposition. On the contrary, I warned you because I was afraid that you would have doubted too much, and hence dismissed the paradox. Therefore I insisted that, despite its paradoxical form, my statement contained an important truth: that research must clearly define its object so that others can identify it, even if this object is mythical. And I made this absolutely clear because this is a didactic book in which I care more that everyone understands what I want to say than about a beautiful literary style. Had I been writing an essay, I would have pronounced the paradox without denouncing it later.

Always define a term when you introduce it for the first time . If you do not know the definition of a term, avoid using it. If it is one of the principal terms of your thesis and you are not able to define it, call it quits. You have chosen the wrong thesis (or, if you were planning to pursue further research, the wrong career).