Get the latest content and program updates from Life Time.

Unsubscribe

The Better Good Life: An Essay on Personal Sustainability

Imagine a cherry tree in full bloom, its roots sunk into rich earth and its branches covered with thousands of blossoms, all emitting a lovely fragrance and containing thousands of seeds capable of producing many more cherry trees. The petals begin to fall, covering the ground in a blanket of white flowers and scattering the seeds everywhere.

Some of the seeds will take root, but the vast majority will simply break down along with the spent petals, becoming part of the soil that nourishes the tree — along with thousands of other plants and animals.

Looking at this scene, do we shake our heads at the senseless waste, mess and inefficiency? Does it look like the tree is working too hard, showing signs of strain or collapse? Of course not. But why not?

Well, for one thing, because the whole process is beautiful, abundant and pleasure producing: We enjoy seeing and smelling the trees in bloom, we’re pleased by the idea of the trees multiplying (and producing delicious cherries ), and everyone for miles around seems to benefit in the process.

The entire lifecycle of the cherry tree is rewarding, and the only “waste” involved is an abundant sort of nutrient cycling that only leads to more good things.

The entire lifecycle of the cherry tree is rewarding, and the only “waste” involved is an abundant sort of nutrient cycling that only leads to more good things. Best of all, this show of productivity and generosity seems to come quite naturally to the tree. It shows no signs of discontent or resentment — in fact, it looks like it could keep this up indefinitely with nothing but good, sustainable outcomes.

The cherry-tree scenario is one model that renowned designer and sustainable-development expert William McDonough uses to illustrate how healthy, sustainable systems are supposed to work. “Every last particle contributes in some way to the health of a thriving ecosystem,” he writes in his essay (coauthored with Michael Braungart), “The Extravagant Gesture: Nature, Design and the Transformation of Human Industry” (available at).

Rampant production in this scenario poses no problem, McDonough explains, because the tree returns all of the resources it extracts (without deterioration or diminution), and it produces no dangerous stockpiles of garbage or residual toxins in the process. In fact, rampant production by the cherry tree only enriches everything around it.

In this system and most systems designed by nature, McDonough notes, “Waste that stays waste does not exist. Instead, waste nourishes; waste equals food.”

If only we humans could be lucky and wise enough to live this way — using our resources and energy to such good effect; making useful, beautiful, extravagant contributions; and producing nothing but nourishing “byproducts” in the process.

If only we humans could be lucky and wise enough to live this way — using our resources and energy to such good effect; making useful, beautiful, extravagant contributions ; and producing nothing but nourishing “byproducts” in the process. If only our version of rampant production and consumption produced so much pleasure and value and so little exhaustion, anxiety, depletion and waste.

Well, perhaps we can learn. More to the point, if we hope to create a decent future for ourselves and succeeding generations, we must. After all, a future produced by trends of the present — in which children are increasingly treated for stress, obesity, high blood pressure and heart disease, and in which our chronic health problems threaten to bankrupt our economy — is not much of a future.

We need to create something better. And for that to happen, we must begin to reconsider which parts of our lives contribute to the cherry tree’s brand of healthy vibrance and abundance, and which don’t.

The happy news is, the search for a more sustainable way of life can go hand in hand with the pursuit of a healthier, more rewarding life. And isn’t that the kind of life most of us are after?

In Search of Sustainability and Satisfaction

McDonough’s cherry-tree model represents several key principles of sustainability — including lifecycle awareness, no-waste nutrient cycling and a commitment to “it’s-all-connected” systems thinking (see “ See the Connection “). And it turns out that many of these principles can be usefully applied not just to natural resources and ecosystems, but to all systems — from frameworks for economic and industrial production to blueprints for individual and collective well-being.

For example, when we look at our lives through the lens of sustainability, we can begin to see how unwise short-term tradeoffs (fast food, skipped workouts, skimpy sleep, strictly-for-the-money jobs) produce waste (squandered energy and vitality, unfulfilled personal potential, excessive material consumption) and toxic byproducts (illness, excess weight , depression, frustration, debt).

We can also see how healthy choices and investments in our personal well-being can produce profoundly positive results that extend to our broader circles of influence and communities at large.

Conversely, we can also see how healthy choices and investments in our personal well-being can produce profoundly positive results that extend to our broader circles of influence and communities at large. When we’re feeling our best and overflowing with energy and optimism, we tend to be of greater service and support to others. We’re clearer of mind, meaning we can identify opportunities to reengineer the things that aren’t working in our lives. We can also more fully appreciate and emphasize the things that are (as opposed to feeling stuck in a rut , down in the dumps, unappreciated or entitled to something we’re not getting).

When you look at it this way, it’s not hard to see why sustainability plays such an important role in creating the conditions of a true “ good life ”: By definition, sustainability principles discourage people from consuming or destroying resources at a greater pace than they can replenish them. They also encourage people to notice when buildups and depletions begin occurring and to correct them as quickly as possible.

As a result, sustainability-oriented approaches tend to produce not just robust, resilient individuals , but resilient and regenerative societies — the kind that manage to produce long-term benefits for a great many without undermining the resources on which those benefits depend. (For a thought-provoking exploration of how and why this has been true historically, read Jared Diamond’s excellent book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed .)

The Good Life Gone Bad

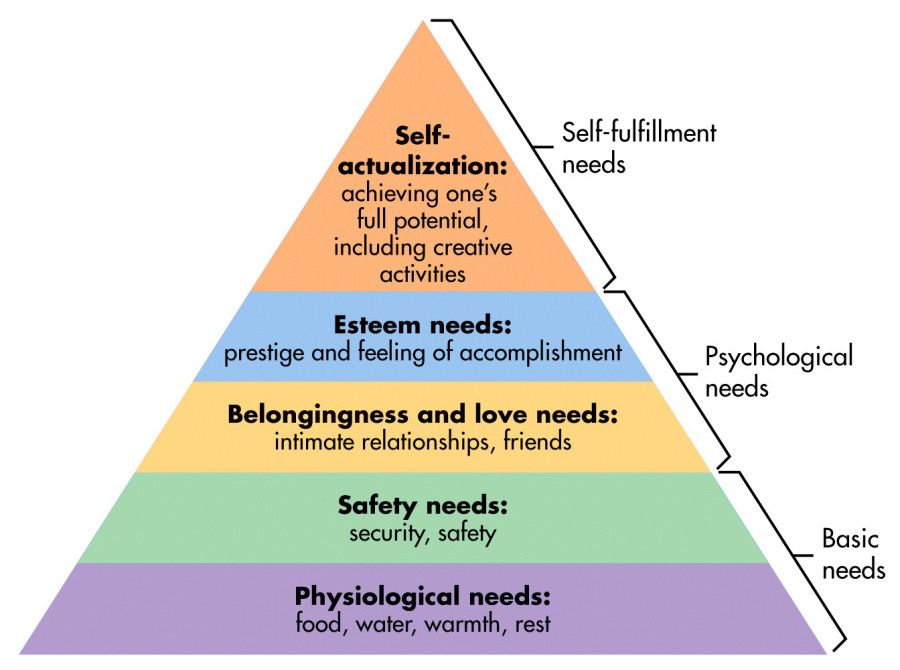

So, what exactly is a “good life”? Clearly, not everyone shares the same definition, but most of us would prefer a life filled with experiences we find pleasing and worthwhile and that contribute to an overall sense of well-being.

We’d prefer a life that feels good in the moment, but that also lays the ground for a promising future — a life, like the cherry tree’s, that contributes something of value and that benefits and enriches the lives of others, or at least doesn’t cause them anxiety and harm.

Unfortunately, historically, our pursuit of the good life has focused on increasing our material wealth and upgrading our socioeconomic status in the short term (learn more at “ What Is Affluenza? “). And, in the big picture, that approach has not turned out quite the way we might have hoped.

For too many, the current version of “the good life” involves working too-long hours and driving too-long commutes. It has us worrying and running ourselves ragged.

For too many, the current version of “the good life” involves working too-long hours and driving too-long commutes. It has us worrying and running ourselves ragged, overeating to soothe ourselves, watching TV to distract ourselves, binge-shopping to sate our desire for more, and popping prescription pills to keep troubling symptoms at bay. This version of “the good life” has given us only moments a day with the people we love, and virtually no time or inclination to participate as citizens or community members.

It has also given us anxiety attacks; obesity; depression ; traffic jams; urban sprawl; crushing daycare bills; a broken healthcare system; record rates of addiction, divorce and incarceration; an imploding economy; and a planet in peril.

From an economic standpoint, we’re more productive than we’ve ever been. We’ve focused on getting more done in less time. We’ve surrounded ourselves with technologies designed to make our lives easier, more comfortable and more amusing.

Yet, instead of making us happy and healthy, all of this has left a great many of us feeling depleted, lonely, strapped, stressed and resentful. We don’t have enough time for ourselves, our loved ones, our creative aspirations or our communities. And in the wake of the bad-mortgage-meets-Wall-Street-greed crisis, much of the so-called value we’ve been busy creating has seemingly vanished before our eyes, leaving future generations of citizens to pay almost inconceivably huge bills.

The conveniences we’ve embraced to save ourselves time have reduced us to an unimaginative, sedentary existence that undermines our physical fitness and mental health and reduces our ability to give our best gifts.

Meanwhile, the quick-energy fuels we use to keep ourselves going ultimately leave us feeling sluggish, inflamed and fatigued. The conveniences we’ve embraced to save ourselves time have reduced us to an unimaginative, sedentary existence that undermines our physical fitness and mental health and reduces our ability to give our best gifts. (Not sure what your best gift is? See “ Play to Your Strengths ” for more.)

Our bodies and minds are showing the telltale symptoms of unsustainable systems at work — systems that put short-term rewards ahead of long-term value. We’re beginning to suspect that the costs we’re incurring could turn out to be unacceptably high if we ever stop to properly account for them, which some of us are beginning to do.

Accounting for What Matters

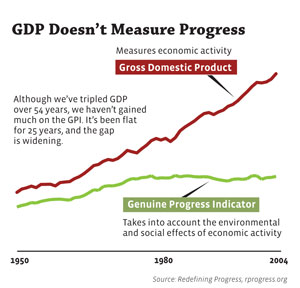

Defining the good life in terms of productivity, material rewards and personal accomplishment is a little like viewing the gross domestic product (GDP) as an accurate measurement of social and economic progress.

In fact, the GDP is nothing more than a gross tally of products and services bought and sold, with no distinctions between transactions that enhance well-being and transactions that diminish it, and no accounting for most of the “externalities” (like losses in vitality, beauty and satisfaction) that actually have the greatest impact on our personal health and welfare.

We’d balk if any business attempted to present a picture of financial health by simply tallying up all of its business activity — lumping income and expense, assets and liabilities, and debits and credits together in one impressive, apparently positive bottom-line number (which is, incidentally, much the way our GDP is calculated).

Yet, in many ways, we do the same kind of flawed calculus in our own lives — regarding as measures of success the gross sum of the to-dos we check off, the salaries we earn, the admiration we attract and the rungs we climb on the corporate ladder.

But not all of these activities actually net us the happiness and satisfaction we seek, and in the process of pursuing them, we can incur appalling costs to our health and happiness. We also make vast sacrifices in terms of our personal relationships and our contributions to the communities, societies and environments on which we depend.

This is the essence of unsustainability , the equivalent of a cherry tree sucking up nutrients and resources and growing nothing but bare branches, or worse — ugly, toxic, foul-smelling blooms. So what are our options?

Asking the Right Questions

In the past several years, many alternative, GDP-like indexes have emerged and attempted to more accurately account for how well (or, more often, how poorly) our economic growth is translating to quality-of-life improvements.

Measurement tools like the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), developed by Redefining Progress, a nonpartisan public-policy and economic think tank, factor in well-being and quality-of-life concerns by considering both positive and negative impacts of various products and services. They also measure more impacts overall (including impacts on elements of “being” and “doing” vs. just “having”). And they evaluate whether various financial expenditures represent a net gain or net loss — not just in economic terms, but also in human, social and ecological ones (see “Sustainable Happiness,” below).

Perhaps it’s time to consider our personal health and well-being in the same sort of broader context — distinguishing productive activities from destructive ones, and figuring the true costs and unintended consequences of our choices into the assessment of how well our lives are working.

To that end, we might begin asking questions like these:

- Where, in our rush to accomplish or enjoy “more” in the short run, are we inadvertently creating the equivalent of garbage dumps and toxic spills (stress overloads, health crises, battered relationships, debt) that will need to be cleaned up later at great (think Superfund) effort and expense?

- Where, in our impatience to garner maximum gains in personal productivity, wealth or achievement in minimum time, are we setting the stage for bailout scenarios down the road? (Consider the sacrifices endured by our families, friends and colleagues when we fall victim to a bad mood, much less a serious illness or disabling health condition.)

- Where, in an attempt to avoid uncertainty, experimentation or change , are we burning through our limited and unrenewable resource of time (staying at jobs that leave us depleted, for example), rather than striving to harness our bottomless stores of purpose-driven enthusiasm (by, say, pursuing careers or civic duties of real meaning)?

- Where are we making short-sighted choices or non-choices (about our health, for example) that sacrifice the resources we need (energy, vitality, clear focus) to make progress and contributions in other areas of our lives?

In addition to these assessments, we can also begin imagining what a better alternative would look like:

- What might be possible if we embraced a different version of the good life — the kind of good life in which the vast majority of our choices both feel good and do good?

- What if we took a systems view of our life , acknowledging how various inputs and outputs play out (for better or worse) over time? What if we fully considered how those around us are affected by our choices now and in the long term?

- What if we embraced more choices that honor our true nature, that gave us more opportunities to use our talents and enthusiasms in the service of a higher purpose?

One has to wonder how many of our health and fitness challenges would evaporate under such conditions — how many compensatory behaviors (overeating, hiding out, numbing out) would simply no longer have a draw.

How many health-sustaining behaviors would become easy and natural choices if each of us were driven by a strong and joyful purpose , and were no longer saddled with the stress and dissatisfaction inherent in the lives we live now?

Think about the cherry-tree effect implicit in such a scenario: each of us getting our needs met, fulfilling our best potential, living at full vitality, and contributing to healthy, vital, sustainable communities in the process.

If it sounds a bit idealistic, that’s probably because it describes an ideal distant enough from our current reality to provoke a certain amount of hopelessness. But that doesn’t mean it’s entirely unrealistic. In fact, it’s a vision that many people are increasingly convinced is the only kind worth pursuing.

Turning the Corner

Maybe it has something to do with how many of our social, economic and ecological systems are showing signs of extreme strain. Maybe it’s how many of us are sick and tired of being sick and tired — or of living in a culture where everyone else seems sick and tired. Maybe it’s the growing realization that no matter how busy and efficient we are, if our efforts don’t feed us in a deep way, then all that output may be more than a little misguided. Whatever the reason, a lot of us are asking: If our rampant productivity doesn’t make us happy, doesn’t allow for calm and creativity, doesn’t give us an opportunity to participate in a meaningful way — then, really, what’s the point?

These days, it seems that more of us are taking a keen interest in seeking out better ways, and seeing the value of extending the lessons of sustainability beyond the natural world and into our own perspectives on what the good life is all about.

In her book MegaTrends 2010: The Rise of Conscious Capitalism , futurist Patricia Aburdene describes a hopeful collection of social and economic trends shaped by a large and influential subset of the American consuming public. What these 70 million individuals have in common, she explains, are some very specific values-driven behaviors — most of which revolve around seeking a better, deeper, more meaningful and sustainable quality of life (discover the four pillars or meaning at “ How to Build a Meaningful Life “).

[“Conscious Consumers” balance] short-term desires and conveniences with long-term well-being — not just their own, but that of their local and larger communities, and of the planet as a whole.

These “Conscious Consumers,” as Aburdene characterizes them, are more carefully weighing material and economic payoffs against moral and spiritual ones. They are balancing short-term desires and conveniences with long-term well-being — not just their own, but that of their local and larger communities, and of the planet as a whole. They are acting, says Aburdene, out of a sort of “enlightened self-interest,” one that is deeply rooted in concerns about sustainability in all its forms.

“Enlightened self-interest is not altruism,” she explains. “It’s self-interest with a wider view. It asks: If I act in my own self-interest and keep doing so, what are the ramifications of my choices? Which acts — that may look fine right now — will come around and bite me and others one year from now? Ten years? Twenty-five years?”

In other words, Conscious Consumers are not merely consumers, but engaged and concerned individuals who think in terms of lifecycles, who perceive the subtleties and complexities of interconnected systems .

As John Muir famously said: “When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.” Just as the cherry tree is tethered in a complex ecosystem of relationships, so are we.

Facing Reality

When we live in a way that diminishes us or weighs us down — whether as the result of poor physical health and fitness, excess stress and anxiety, or any compromise of our best potential — we inevitably affect countless other people and systems whose well-being relies on our own.

For example, if we don’t have the time and energy to make food for ourselves and our families, we end up eating poorly, which further diminishes our energy, and may also result in our kids having behavior or attention problems at school, undermining the quality of their experience there, and potentially creating problems for others.

As satisfaction and well-being go down, need and consumption go up.

If we skimp on sleep and relaxation in order to “get more done,” we court illness and depression, risking both our own and others’ productivity and happiness in the process and diminishing the creativity with which we approach challenges.

At the individual level, unsustainable choices create strain and misery. At the collective level, they do the same thing, with exponential effect. Because, when not enough of us are living like thriving cherry trees, cycles of scarcity (rather than abundance) ensue. Life gets harder for everyone. As satisfaction and well-being go down, need and consumption go up. Our sense of “enough” becomes distorted.

Taking Full Account

The basic question of sustainability is this: Can you keep doing what you’re doing indefinitely and without ill effect to yourself and the systems on which you depend — or are you (despite short-term rewards you may be enjoying now, or the “someday” relief you’re hoping for) on a likely trajectory to eventual suffering and destruction?

When it comes to the ecology of the planet, this question has become very pointed in recent years. But posed in the context of our personal lives, the question is equally instructive: Are we living like the cherry tree — part of a sustainable and regenerative cycle — or are we sucking up resources, yet still obsessed with what we don’t have? Are we continually generating new energy, vitality, generosity and personal potential , or wasting it?

We can work just so hard and consume just so much before we begin to experience both diminishing personal returns and increasing degenerative costs.

The human reality, in most cases, isn’t quite as pretty as the cherry tree in full bloom. We can work just so hard and consume just so much before we begin to experience both diminishing personal returns and increasing degenerative costs. And when enough of us are in a chronically diminished state of well-being, the effect is a sort of social and moral pollution — the human equivalent of the greenhouse gasses that threaten our entire ecosystem.

Accounting for these soft costs, or even recognizing them as relevant externalities, is not something we’ve been trained to do well. But all that is changing — in part, because many of us are beginning to realize that much of what we’ve been sold in the name of “progress” is now looking like anything but. And, in part, because we’re starting to believe that not only might there be a better way, but that the principles for creating it are staring us right in the face.

By making personal choices that respect the principles of sustainability, we can interrupt the toxic cycles of overconsumption and overexertion. Ultimately, when confronted with the possibility of a better quality of life and more satisfying expression of our potential, the primary question becomes not just can we continue living the way we have been, but perhaps just as important, why would we even want to ?

If the approach we’ve been taking appears likely to make us miserable (and perhaps extinct), then it makes sense to consider our options. How do we want to live for the foreseeable and sustainable future, and what are the building blocks for that future? What would it be like to live in a community where most people were overflowing with vitality and looking for ways to be of service to others?

While no one expert or index or council claims to have all the answers to that question, when it comes to discerning the fundamentals of the good life, nature conveniently provides most of the models we need. It suggests a framework by which we can better understand and apply the principles of sustainability to our own lives. Now it’s up to us to apply them.

Make It Sustainable

Here are some right-now changes you can make to enhance and sustain your personal well-being:

1. Rethink Your Eating.

Look beyond meal-to-meal concerns with weight. Aim to eat consciously and selectively in keeping with the nourishment you want to take in, the energy and personal gifts you want to contribute, and the influence you want to have on the world around you.

To that end, you might start eating less meat, or fewer packaged foods, or you might start eating regularly so that you have enough energy to exercise (and so that your low blood sugar doesn’t negatively affect your mood and everyone around you).

You also might start packing your lunch, suggests money expert Vicki Robin: Not only will you have more control over what and how you eat, but the money you’ll save over the course of a career can amount to a year’s worth of work. “Bringing your lunch saves you a year of your life,” she says.

2. Set a Regular Bedtime

Having a target bedtime can help you get the sleep you need to be positive and productive, and to avoid becoming depleted and depressed. Research confirms that adequate sleep is essential to clear thinking, balanced mood, healthy metabolism, strong immunity, optimal vitality and strong professional performance.

Research also shows that going to bed earlier provides a higher quality of rest than sleeping in, so get your hours at the start of the night. By taking care of yourself in this simple way, you lay the groundwork for all kinds of regenerative (vs. depleting) cycles.

3. Own Your Outcomes

If there are parts of your life you don’t like — parts that feel toxic, frustrating or wasteful to you — be willing to trace the outcomes back to their origins, including your choices around self-care , seeking help, balancing priorities and sticking to your core values.

Also examine the full range of outputs and impacts: What waste or damage is occurring as a result of this area of unresolved challenge? Who else and what else in your life might be paying too-high a price for the scenario in question? If you’re unsure about whether or not a choice or an activity you’re involved in is sustainable, ask yourself the following questions:

- Given the option, would I do or choose this again? Would I do it indefinitely?

- How long can I keep this up, and at what cost — not just to me, but to the other people and systems I care about?

- What have I sacrificed to get here; what will it take for me to continue? Are the rewards worth it, even if the other areas of my life suffer?

Sustainable Happiness

Not all growth and productivity represent progress, particularly if you consider happiness and well-being as part of the equation. The growing gap between our gross domestic product and Genuine Progress Indicator (as represented below) suggests we could be investing our resources with far happier results.

Data source: Redefining Progress, rprogress.org . Chart graphic courtesy of Yes! magazine.

Learn more about the most reliable, sustainable sources of happiness and well-being in the Winter 2009 issue of Yes! magazine, available at www.yesmagazine.org .

Learning From Nature

What can we learn from ecological sustainability about the best ways to balance and sustain our own lives? Here are a few key lessons:

- Everything is in relationship with everything else. So overdrawing or overproducing in one area tends to negatively affect other areas. An excessive focus on work can undermine your relationship with your partner or kids. Diminished physical vitality or low mood can affect the quality of your work and service to others.

- What comes around goes around. Trying to “cheat” or “skimp” or “get away with something” in the short term generally doesn’t work because the true costs of cheating eventually become painfully obvious. And very often the “cleanup” costs more and takes longer than it would have to simply do the right thing in the first place.

- Waste not, want not. Unpleasant accumulations or unsustainable drains represent opportunities for improvement and reinvention. Nature’s models of nutrient cycling show us that what looks like waste can become food for a process we simply haven’t engaged yet: Anxiety may be nervous energy that needs to be burned off, or a nudge to do relaxation and self-inquiry exercises that will churn up new insights and ideas. Excess fat may be fuel for enjoyable activities we’ve resisted doing or haven’t yet discovered — or a clue that we’re hungry for something other than food. The clutter in our homes may represent resources that we haven’t gotten around to sharing. Look for ways to put waste and excess to work, and you may discover all kinds of “nutrients” just looking for attention. (See “ The Emotional Toll of Clutter “.)

The Sustainable Self

Connie Grauds, RPh, is a pharmacist who combines her Western medical training with shamanic teachings, and in her view, we get caught in wearying patterns primarily because of fear . “Energy-depleting thoughts and feelings underlie energy-depleting habits,” Grauds writes in her book The Energy Prescription , cowritten with Doug Childers. She says that we often burn ourselves out because we’re unconsciously afraid of what will happen if we don’t.

Grauds uses the shamanic term “susto” to describe our anxious response to external situations we can’t control — the traffic jam, the work deadline, the pressure to buy stuff we don’t really need. “Susto” triggers the body’s fight-or-flight response, which encourages short-term, unconscious reactions to stress. When we shift to a more internal focus, tuning in to our body’s physical and emotional signals more reflectively, we act from what Grauds calls our “sustainable self.” She says the sustainable self can be accessed anytime with a simple four-step process:

- Take a deep breath ;

- Feel your body;

- Notice your thoughts, and then;

- Recognize that you are connected to a larger network of energy .

“A sustainable self recognizes and embraces its interdependent relationship to life,” she says, explaining that when we get our energy from controlling external circumstances we’re bound to collapse eventually, but when we’re connected to our internal reserves, we can be much more effective. “By consistently doing things that replenish us and not doing things that needlessly deplete us,” Grauds writes, “we access and conduct the energy we need to make and sustain positive changes and function at peak levels.”

Thoughts to share?

This Post Has 0 Comments

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

ADVERTISEMENT

More Like This

How to Develop a ‘Stretch’ Mindset

Working with what you have can be the key to more sustainable success. Adopting a “stretch” mindset can help.

The Power of Intention: Learning to Co-Create Your World Your Way

Thought-provoking takeaways from Wayne Dyer’s classic guide to conscious living.

6 Keys to a Happy and Healthy Life

A functional-medicine pioneer explains how to make small choices that build lasting well-being.

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

- Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

Eight brilliant student essays on what matters most in life.

Read winning essays from our spring 2019 student writing contest.

For the spring 2019 student writing contest, we invited students to read the YES! article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age” by Nancy Hill. Like the author, students interviewed someone significantly older than them about the three things that matter most in life. Students then wrote about what they learned, and about how their interviewees’ answers compare to their own top priorities.

The Winners

From the hundreds of essays written, these eight were chosen as winners. Be sure to read the author’s response to the essay winners and the literary gems that caught our eye. Plus, we share an essay from teacher Charles Sanderson, who also responded to the writing prompt.

Middle School Winner: Rory Leyva

High School Winner: Praethong Klomsum

University Winner: Emily Greenbaum

Powerful Voice Winner: Amanda Schwaben

Powerful Voice Winner: Antonia Mills

Powerful Voice Winner: Isaac Ziemba

Powerful Voice Winner: Lily Hersch

“Tell It Like It Is” Interview Winner: Jonas Buckner

From the Author: Response to Student Winners

Literary Gems

From A Teacher: Charles Sanderson

From the Author: Response to Charles Sanderson

Middle School Winner

Village Home Education Resource Center, Portland, Ore.

The Lessons Of Mortality

“As I’ve aged, things that are more personal to me have become somewhat less important. Perhaps I’ve become less self-centered with the awareness of mortality, how short one person’s life is.” This is how my 72-year-old grandma believes her values have changed over the course of her life. Even though I am only 12 years old, I know my life won’t last forever, and someday I, too, will reflect on my past decisions. We were all born to exist and eventually die, so we have evolved to value things in the context of mortality.

One of the ways I feel most alive is when I play roller derby. I started playing for the Rose City Rollers Juniors two years ago, and this year, I made the Rosebud All-Stars travel team. Roller derby is a fast-paced, full-contact sport. The physicality and intense training make me feel in control of and present in my body.

My roller derby team is like a second family to me. Adolescence is complicated. We understand each other in ways no one else can. I love my friends more than I love almost anything else. My family would have been higher on my list a few years ago, but as I’ve aged it has been important to make my own social connections.

Music led me to roller derby. I started out jam skating at the roller rink. Jam skating is all about feeling the music. It integrates gymnastics, breakdancing, figure skating, and modern dance with R & B and hip hop music. When I was younger, I once lay down in the DJ booth at the roller rink and was lulled to sleep by the drawl of wheels rolling in rhythm and people talking about the things they came there to escape. Sometimes, I go up on the roof of my house at night to listen to music and feel the wind rustle my hair. These unique sensations make me feel safe like nothing else ever has.

My grandma tells me, “Being close with family and friends is the most important thing because I haven’t

always had that.” When my grandma was two years old, her father died. Her mother became depressed and moved around a lot, which made it hard for my grandma to make friends. Once my grandma went to college, she made lots of friends. She met my grandfather, Joaquin Leyva when she was working as a park ranger and he was a surfer. They bought two acres of land on the edge of a redwood forest and had a son and a daughter. My grandma created a stable family that was missing throughout her early life.

My grandma is motivated to maintain good health so she can be there for her family. I can relate because I have to be fit and strong for my team. Since she lost my grandfather to cancer, she realizes how lucky she is to have a functional body and no life-threatening illnesses. My grandma tries to eat well and exercise, but she still struggles with depression. Over time, she has learned that reaching out to others is essential to her emotional wellbeing.

Caring for the earth is also a priority for my grandma I’ve been lucky to learn from my grandma. She’s taught me how to hunt for fossils in the desert and find shells on the beach. Although my grandma grew up with no access to the wilderness, she admired the green open areas of urban cemeteries. In college, she studied geology and hiked in the High Sierras. For years, she’s been an advocate for conserving wildlife habitat and open spaces.

Our priorities may seem different, but it all comes down to basic human needs. We all desire a purpose, strive to be happy, and need to be loved. Like Nancy Hill says in the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” it can be hard to decipher what is important in life. I believe that the constant search for satisfaction and meaning is the only thing everyone has in common. We all want to know what matters, and we walk around this confusing world trying to find it. The lessons I’ve learned from my grandma about forging connections, caring for my body, and getting out in the world inspire me to live my life my way before it’s gone.

Rory Leyva is a seventh-grader from Portland, Oregon. Rory skates for the Rosebuds All-Stars roller derby team. She loves listening to music and hanging out with her friends.

High School Winner

Praethong Klomsum

Santa Monica High School, Santa Monica, Calif.

Time Only Moves Forward

Sandra Hernandez gazed at the tiny house while her mother’s gentle hands caressed her shoulders. It wasn’t much, especially for a family of five. This was 1960, she was 17, and her family had just moved to Culver City.

Flash forward to 2019. Sandra sits in a rocking chair, knitting a blanket for her latest grandchild, in the same living room. Sandra remembers working hard to feed her eight children. She took many different jobs before settling behind the cash register at a Japanese restaurant called Magos. “It was a struggle, and my husband Augustine, was planning to join the military at that time, too.”

In the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” author Nancy Hill states that one of the most important things is “…connecting with others in general, but in particular with those who have lived long lives.” Sandra feels similarly. It’s been hard for Sandra to keep in contact with her family, which leaves her downhearted some days. “It’s important to maintain that connection you have with your family, not just next-door neighbors you talk to once a month.”

Despite her age, Sandra is a daring woman. Taking risks is important to her, and she’ll try anything—from skydiving to hiking. Sandra has some regrets from the past, but nowadays, she doesn’t wonder about the “would have, could have, should haves.” She just goes for it with a smile.

Sandra thought harder about her last important thing, the blue and green blanket now finished and covering

her lap. “I’ve definitely lived a longer life than most, and maybe this is just wishful thinking, but I hope I can see the day my great-grandchildren are born.” She’s laughing, but her eyes look beyond what’s in front of her. Maybe she is reminiscing about the day she held her son for the first time or thinking of her grandchildren becoming parents. I thank her for her time and she waves it off, offering me a styrofoam cup of lemonade before I head for the bus station.

The bus is sparsely filled. A voice in my head reminds me to finish my 10-page history research paper before spring break. I take a window seat and pull out my phone and earbuds. My playlist is already on shuffle, and I push away thoughts of that dreaded paper. Music has been a constant in my life—from singing my lungs out in kindergarten to Barbie’s “I Need To Know,” to jamming out to Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space” in sixth grade, to BTS’s “Intro: Never Mind” comforting me when I’m at my lowest. Music is my magic shop, a place where I can trade away my fears for calm.

I’ve always been afraid of doing something wrong—not finishing my homework or getting a C when I can do better. When I was 8, I wanted to be like the big kids. As I got older, I realized that I had exchanged my childhood longing for the 48 pack of crayons for bigger problems, balancing grades, a social life, and mental stability—all at once. I’m going to get older whether I like it or not, so there’s no point forcing myself to grow up faster. I’m learning to live in the moment.

The bus is approaching my apartment, where I know my comfy bed and a home-cooked meal from my mom are waiting. My mom is hard-working, confident, and very stubborn. I admire her strength of character. She always keeps me in line, even through my rebellious phases.

My best friend sends me a text—an update on how broken her laptop is. She is annoying. She says the stupidest things and loves to state the obvious. Despite this, she never fails to make me laugh until my cheeks feel numb. The rest of my friends are like that too—loud, talkative, and always brightening my day. Even friends I stopped talking to have a place in my heart. Recently, I’ve tried to reconnect with some of them. This interview was possible because a close friend from sixth grade offered to introduce me to Sandra, her grandmother.

I’m decades younger than Sandra, so my view of what’s important isn’t as broad as hers, but we share similar values, with friends and family at the top. I have a feeling that when Sandra was my age, she used to love music, too. Maybe in a few decades, when I’m sitting in my rocking chair, drawing in my sketchbook, I’ll remember this article and think back fondly to the days when life was simple.

Praethong Klomsum is a tenth-grader at Santa Monica High School in Santa Monica, California. Praethong has a strange affinity for rhyme games and is involved in her school’s dance team. She enjoys drawing and writing, hoping to impact people willing to listen to her thoughts and ideas.

University Winner

Emily Greenbaum

Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

The Life-Long War

Every morning we open our eyes, ready for a new day. Some immediately turn to their phones and social media. Others work out or do yoga. For a certain person, a deep breath and the morning sun ground him. He hears the clink-clank of his wife cooking low sodium meat for breakfast—doctor’s orders! He sees that the other side of the bed is already made, the dogs are no longer in the room, and his clothes are set out nicely on the loveseat.

Today, though, this man wakes up to something different: faded cream walls and jello. This person, my hero, is Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James.

I pulled up my chair close to Roger’s vinyl recliner so I could hear him above the noise of the beeping dialysis machine. I noticed Roger would occasionally glance at his wife Susan with sparkly eyes when he would recall memories of the war or their grandkids. He looked at Susan like she walked on water.

Roger James served his country for thirty years. Now, he has enlisted in another type of war. He suffers from a rare blood cancer—the result of the wars he fought in. Roger has good and bad days. He says, “The good outweighs the bad, so I have to be grateful for what I have on those good days.”

When Roger retired, he never thought the effects of the war would reach him. The once shallow wrinkles upon his face become deeper, as he tells me, “It’s just cancer. Others are suffering from far worse. I know I’ll make it.”

Like Nancy Hill did in her article “Three Things that Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I asked Roger, “What are the three most important things to you?” James answered, “My wife Susan, my grandkids, and church.”

Roger and Susan served together in the Vietnam war. She was a nurse who treated his cuts and scrapes one day. I asked Roger why he chose Susan. He said, “Susan told me to look at her while she cleaned me up. ‘This may sting, but don’t be a baby.’ When I looked into her eyes, I felt like she was looking into my soul, and I didn’t want her to leave. She gave me this sense of home. Every day I wake up, she makes me feel the same way, and I fall in love with her all over again.”

Roger and Susan have two kids and four grandkids, with great-grandchildren on the way. He claims that his grandkids give him the youth that he feels slowly escaping from his body. This adoring grandfather is energized by coaching t-ball and playing evening card games with the grandkids.

The last thing on his list was church. His oldest daughter married a pastor. Together they founded a church. Roger said that the connection between his faith and family is important to him because it gave him a reason to want to live again. I learned from Roger that when you’re across the ocean, you tend to lose sight of why you are fighting. When Roger returned, he didn’t have the will to live. Most days were a struggle, adapting back into a society that lacked empathy for the injuries, pain, and psychological trauma carried by returning soldiers. Church changed that for Roger and gave him a sense of purpose.

When I began this project, my attitude was to just get the assignment done. I never thought I could view Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James as more than a role model, but he definitely changed my mind. It’s as if Roger magically lit a fire inside of me and showed me where one’s true passions should lie. I see our similarities and embrace our differences. We both value family and our own connections to home—his home being church and mine being where I can breathe the easiest.

Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James has shown me how to appreciate what I have around me and that every once in a while, I should step back and stop to smell the roses. As we concluded the interview, amidst squeaky clogs and the stale smell of bleach and bedpans, I looked to Roger, his kind, tired eyes, and weathered skin, with a deeper sense of admiration, knowing that his values still run true, no matter what he faces.

Emily Greenbaum is a senior at Kent State University, graduating with a major in Conflict Management and minor in Geography. Emily hopes to use her major to facilitate better conversations, while she works in the Washington, D.C. area.

Powerful Voice Winner

Amanda Schwaben

Wise Words From Winnie the Pooh

As I read through Nancy Hill’s article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I was comforted by the similar responses given by both children and older adults. The emphasis participants placed on family, social connections, and love was not only heartwarming but hopeful. While the messages in the article filled me with warmth, I felt a twinge of guilt building within me. As a twenty-one-year-old college student weeks from graduation, I honestly don’t think much about the most important things in life. But if I was asked, I would most likely say family, friendship, and love. As much as I hate to admit it, I often find myself obsessing over achieving a successful career and finding a way to “save the world.”

A few weeks ago, I was at my family home watching the new Winnie the Pooh movie Christopher Robin with my mom and younger sister. Well, I wasn’t really watching. I had my laptop in front of me, and I was aggressively typing up an assignment. Halfway through the movie, I realized I left my laptop charger in my car. I walked outside into the brisk March air. Instinctively, I looked up. The sky was perfectly clear, revealing a beautiful array of stars. When my twin sister and I were in high school, we would always take a moment to look up at the sparkling night sky before we came into the house after soccer practice.

I think that was the last time I stood in my driveway and gazed at the stars. I did not get the laptop charger from

my car; instead, I turned around and went back inside. I shut my laptop and watched the rest of the movie. My twin sister loves Winnie the Pooh. So much so that my parents got her a stuffed animal version of him for Christmas. While I thought he was adorable and a token of my childhood, I did not really understand her obsession. However, it was clear to me after watching the movie. Winnie the Pooh certainly had it figured out. He believed that the simple things in life were the most important: love, friendship, and having fun.

I thought about asking my mom right then what the three most important things were to her, but I decided not to. I just wanted to be in the moment. I didn’t want to be doing homework. It was a beautiful thing to just sit there and be present with my mom and sister.

I did ask her, though, a couple of weeks later. Her response was simple. All she said was family, health, and happiness. When she told me this, I imagined Winnie the Pooh smiling. I think he would be proud of that answer.

I was not surprised by my mom’s reply. It suited her perfectly. I wonder if we relearn what is most important when we grow older—that the pressure to be successful subsides. Could it be that valuing family, health, and happiness is what ends up saving the world?

Amanda Schwaben is a graduating senior from Kent State University with a major in Applied Conflict Management. Amanda also has minors in Psychology and Interpersonal Communication. She hopes to further her education and focus on how museums not only preserve history but also promote peace.

Antonia Mills

Rachel Carson High School, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Decoding The Butterfly

For a caterpillar to become a butterfly, it must first digest itself. The caterpillar, overwhelmed by accumulating tissue, splits its skin open to form its protective shell, the chrysalis, and later becomes the pretty butterfly we all know and love. There are approximately 20,000 species of butterflies, and just as every species is different, so is the life of every butterfly. No matter how long and hard a caterpillar has strived to become the colorful and vibrant butterfly that we marvel at on a warm spring day, it does not live a long life. A butterfly can live for a year, six months, two weeks, and even as little as twenty-four hours.

I have often wondered if butterflies live long enough to be blissful of blue skies. Do they take time to feast upon the sweet nectar they crave, midst their hustling life of pollinating pretty flowers? Do they ever take a lull in their itineraries, or are they always rushing towards completing their four-stage metamorphosis? Has anyone asked the butterfly, “Who are you?” instead of “What are you”? Or, How did you get here, on my windowsill? How did you become ‘you’?

Humans are similar to butterflies. As a caterpillar

Suzanna Ruby/Getty Images

becomes a butterfly, a baby becomes an elder. As a butterfly soars through summer skies, an elder watches summer skies turn into cold winter nights and back toward summer skies yet again. And as a butterfly flits slowly by the porch light, a passerby makes assumptions about the wrinkled, slow-moving elder, who is sturdier than he appears. These creatures are not seen for who they are—who they were—because people have “better things to do” or they are too busy to ask, “How are you”?

Our world can be a lonely place. Pressured by expectations, haunted by dreams, overpowered by weakness, and drowned out by lofty goals, we tend to forget ourselves—and others. Rather than hang onto the strands of our diminishing sanity, we might benefit from listening to our elders. Many elders have experienced setbacks in their young lives. Overcoming hardship and surviving to old age is wisdom that they carry. We can learn from them—and can even make their day by taking the time to hear their stories.

Nancy Hill, who wrote the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” was right: “We live among such remarkable people, yet few know their stories.” I know a lot about my grandmother’s life, and it isn’t as serene as my own. My grandmother, Liza, who cooks every day, bakes bread on holidays for our neighbors, brings gifts to her doctor out of the kindness of her heart, and makes conversation with neighbors even though she is isn’t fluent in English—Russian is her first language—has struggled all her life. Her mother, Anna, a single parent, had tuberculosis, and even though she had an inviolable spirit, she was too frail to care for four children. She passed away when my grandmother was sixteen, so my grandmother and her siblings spent most of their childhood in an orphanage. My grandmother got married at nineteen to my grandfather, Pinhas. He was a man who loved her more than he loved himself and was a godsend to every person he met. Liza was—and still is—always quick to do what was best for others, even if that person treated her poorly. My grandmother has lived with physical pain all her life, yet she pushed herself to climb heights that she wasn’t ready for. Against all odds, she has lived to tell her story to people who are willing to listen. And I always am.

I asked my grandmother, “What are three things most important to you?” Her answer was one that I already expected: One, for everyone to live long healthy lives. Two, for you to graduate from college. Three, for you to always remember that I love you.

What may be basic to you means the world to my grandmother. She just wants what she never had the chance to experience: a healthy life, an education, and the chance to express love to the people she values. The three things that matter most to her may be so simple and ordinary to outsiders, but to her, it is so much more. And who could take that away?

Antonia Mills was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York and attends Rachel Carson High School. Antonia enjoys creative activities, including writing, painting, reading, and baking. She hopes to pursue culinary arts professionally in the future. One of her favorite quotes is, “When you start seeing your worth, you’ll find it harder to stay around people who don’t.” -Emily S.P.

Powerful Voice Winner

Isaac Ziemba

Odyssey Multiage Program, Bainbridge Island, Wash.

This Former State Trooper Has His Priorities Straight: Family, Climate Change, and Integrity

I have a personal connection to people who served in the military and first responders. My uncle is a first responder on the island I live on, and my dad retired from the Navy. That was what made a man named Glen Tyrell, a state trooper for 25 years, 2 months and 9 days, my first choice to interview about what three things matter in life. In the YES! Magazine article “The Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I learned that old and young people have a great deal in common. I know that’s true because Glen and I care about a lot of the same things.

For Glen, family is at the top of his list of important things. “My wife was, and is, always there for me. My daughters mean the world to me, too, but Penny is my partner,” Glen said. I can understand why Glen’s wife is so important to him. She’s family. Family will always be there for you.

Glen loves his family, and so do I with all my heart. My dad especially means the world to me. He is my top supporter and tells me that if I need help, just “say the word.” When we are fishing or crabbing, sometimes I

think, what if these times were erased from my memory? I wouldn’t be able to describe the horrible feeling that would rush through my mind, and I’m sure that Glen would feel the same about his wife.

My uncle once told me that the world is always going to change over time. It’s what the world has turned out to be that worries me. Both Glen and I are extremely concerned about climate change and the effect that rising temperatures have on animals and their habitats. We’re driving them to extinction. Some people might say, “So what? Animals don’t pay taxes or do any of the things we do.” What we are doing to them is like the Black Death times 100.

Glen is also frustrated by how much plastic we use and where it ends up. He would be shocked that an explorer recently dived to the deepest part of the Pacific Ocean—seven miles!— and discovered a plastic bag and candy wrappers. Glen told me that, unfortunately, his generation did the damage and my generation is here to fix it. We need to take better care of Earth because if we don’t, we, as a species, will have failed.

Both Glen and I care deeply for our families and the earth, but for our third important value, I chose education and Glen chose integrity. My education is super important to me because without it, I would be a blank slate. I wouldn’t know how to figure out problems. I wouldn’t be able to tell right from wrong. I wouldn’t understand the Bill of Rights. I would be stuck. Everyone should be able to go to school, no matter where they’re from or who they are. It makes me angry and sad to think that some people, especially girls, get shot because they are trying to go to school. I understand how lucky I am.

Integrity is sacred to Glen—I could tell by the serious tone of Glen’s voice when he told me that integrity was the code he lived by as a former state trooper. He knew that he had the power to change a person’s life, and he was committed to not abusing that power. When Glen put someone under arrest—and my uncle says the same—his judgment and integrity were paramount. “Either you’re right or you’re wrong.” You can’t judge a person by what you think, you can only judge a person from what you know.”

I learned many things about Glen and what’s important in life, but there is one thing that stands out—something Glen always does and does well. Glen helps people. He did it as a state trooper, and he does it in our school, where he works on construction projects. Glen told me that he believes that our most powerful tools are writing and listening to others. I think those tools are important, too, but I also believe there are other tools to help solve many of our problems and create a better future: to be compassionate, to create caring relationships, and to help others. Just like Glen Tyrell does each and every day.

Isaac Ziemba is in seventh grade at the Odyssey Multiage Program on a small island called Bainbridge near Seattle, Washington. Isaac’s favorite subject in school is history because he has always been interested in how the past affects the future. In his spare time, you can find Isaac hunting for crab with his Dad, looking for artifacts around his house with his metal detector, and having fun with his younger cousin, Conner.

Lily Hersch

The Crest Academy, Salida, Colo.

The Phone Call

Dear Grandpa,

In my short span of life—12 years so far—you’ve taught me a lot of important life lessons that I’ll always have with me. Some of the values I talk about in this writing I’ve learned from you.

Dedicated to my Gramps.

In the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” author and photographer Nancy Hill asked people to name the three things that mattered most to them. After reading the essay prompt for the article, I immediately knew who I wanted to interview: my grandpa Gil.

My grandpa was born on January 25, 1942. He lived in a minuscule tenement in The Bronx with his mother,

father, and brother. His father wasn’t around much, and, when he was, he was reticent and would snap occasionally, revealing his constrained mental pain. My grandpa says this happened because my great grandfather did not have a father figure in his life. His mother was a classy, sharp lady who was the head secretary at a local police district station. My grandpa and his brother Larry did not care for each other. Gramps said he was very close to his mother, and Larry wasn’t. Perhaps Larry was envious for what he didn’t have.

Decades after little to no communication with his brother, my grandpa decided to spontaneously visit him in Florida, where he resided with his wife. Larry was taken aback at the sudden reappearance of his brother and told him to leave. Since then, the two brothers have not been in contact. My grandpa doesn’t even know if Larry is alive.

My grandpa is now a retired lawyer, married to my wonderful grandma, and living in a pretty house with an ugly dog named BoBo.

So, what’s important to you, Gramps?

He paused a second, then replied, “Family, kindness, and empathy.”

“Family, because it’s my family. It’s important to stay connected with your family. My brother, father, and I never connected in the way I wished, and sometimes I contemplated what could’ve happened. But you can’t change the past. So, that’s why family’s important to me.”

Family will always be on my “Top Three Most Important Things” list, too. I can’t imagine not having my older brother, Zeke, or my grandma in my life. I wonder how other kids feel about their families? How do kids trapped and separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border feel? What about orphans? Too many questions, too few answers.

“Kindness, because growing up and not seeing a lot of kindness made me realize how important it is to have that in the world. Kindness makes the world go round.”

What is kindness? Helping my brother, Eli, who has Down syndrome, get ready in the morning? Telling people what they need to hear, rather than what they want to hear? Maybe, for now, I’ll put wisdom, not kindness, on my list.

“Empathy, because of all the killings and shootings [in this country.] We also need to care for people—people who are not living in as good circumstances as I have. Donald Trump and other people I’ve met have no empathy. Empathy is very important.”

Empathy is something I’ve felt my whole life. It’ll always be important to me like it is important to my grandpa. My grandpa shows his empathy when he works with disabled children. Once he took a disabled child to a Christina Aguilera concert because that child was too young to go by himself. The moments I feel the most empathy are when Eli gets those looks from people. Seeing Eli wonder why people stare at him like he’s a freak makes me sad, and annoyed that they have the audacity to stare.

After this 2 minute and 36-second phone call, my grandpa has helped me define what’s most important to me at this time in my life: family, wisdom, and empathy. Although these things are important now, I realize they can change and most likely will.

When I’m an old woman, I envision myself scrambling through a stack of storage boxes and finding this paper. Perhaps after reading words from my 12-year-old self, I’ll ask myself “What’s important to me?”

Lily Hersch is a sixth-grader at Crest Academy in Salida, Colorado. Lily is an avid indoorsman, finding joy in competitive spelling, art, and of course, writing. She does not like Swiss cheese.

“Tell It Like It Is” Interview Winner

Jonas Buckner

KIPP: Gaston College Preparatory, Gaston, N.C.

Lessons My Nana Taught Me

I walked into the house. In the other room, I heard my cousin screaming at his game. There were a lot of Pioneer Woman dishes everywhere. The room had the television on max volume. The fan in the other room was on. I didn’t know it yet, but I was about to learn something powerful.

I was in my Nana’s house, and when I walked in, she said, “Hey Monkey Butt.”

I said, “Hey Nana.”

Before the interview, I was talking to her about what I was gonna interview her on. Also, I had asked her why I might have wanted to interview her, and she responded with, “Because you love me, and I love you too.”

Now, it was time to start the interview. The first

question I asked was the main and most important question ever: “What three things matter most to you and you only?”

She thought of it very thoughtfully and responded with, “My grandchildren, my children, and my health.”

Then, I said, “OK, can you please tell me more about your health?”

She responded with, “My health is bad right now. I have heart problems, blood sugar, and that’s about it.” When she said it, she looked at me and smiled because she loved me and was happy I chose her to interview.

I replied with, “K um, why is it important to you?”

She smiled and said, “Why is it…Why is my health important? Well, because I want to live a long time and see my grandchildren grow up.”

I was scared when she said that, but she still smiled. I was so happy, and then I said, “Has your health always been important to you.”

She responded with “Nah.”

Then, I asked, “Do you happen to have a story to help me understand your reasoning?”

She said, “No, not really.”

Now we were getting into the next set of questions. I said, “Remember how you said that your grandchildren matter to you? Can you please tell me why they matter to you?”

Then, she responded with, “So I can spend time with them, play with them, and everything.”

Next, I asked the same question I did before: “Have you always loved your grandchildren?”

She responded with, “Yes, they have always been important to me.”

Then, the next two questions I asked she had no response to at all. She was very happy until I asked, “Why do your children matter most to you?”

She had a frown on and responded, “My daughter Tammy died a long time ago.”

Then, at this point, the other questions were answered the same as the other ones. When I left to go home I was thinking about how her answers were similar to mine. She said health, and I care about my health a lot, and I didn’t say, but I wanted to. She also didn’t have answers for the last two questions on each thing, and I was like that too.

The lesson I learned was that no matter what, always keep pushing because even though my aunt or my Nana’s daughter died, she kept on pushing and loving everyone. I also learned that everything should matter to us. Once again, I chose to interview my Nana because she matters to me, and I know when she was younger she had a lot of things happen to her, so I wanted to know what she would say. The point I’m trying to make is that be grateful for what you have and what you have done in life.

Jonas Buckner is a sixth-grader at KIPP: Gaston College Preparatory in Gaston, North Carolina. Jonas’ favorite activities are drawing, writing, math, piano, and playing AltSpace VR. He found his passion for writing in fourth grade when he wrote a quick autobiography. Jonas hopes to become a horror writer someday.

From The Author: Responses to Student Winners

Dear Emily, Isaac, Antonia, Rory, Praethong, Amanda, Lily, and Jonas,

Your thought-provoking essays sent my head spinning. The more I read, the more impressed I was with the depth of thought, beauty of expression, and originality. It left me wondering just how to capture all of my reactions in a single letter. After multiple false starts, I’ve landed on this: I will stick to the theme of three most important things.

The three things I found most inspirational about your essays:

You listened.

You connected.

We live in troubled times. Tensions mount between countries, cultures, genders, religious beliefs, and generations. If we fail to find a way to understand each other, to see similarities between us, the future will be fraught with increased hostility.

You all took critical steps toward connecting with someone who might not value the same things you do by asking a person who is generations older than you what matters to them. Then, you listened to their answers. You saw connections between what is important to them and what is important to you. Many of you noted similarities, others wondered if your own list of the three most important things would change as you go through life. You all saw the validity of the responses you received and looked for reasons why your interviewees have come to value what they have.

It is through these things—asking, listening, and connecting—that we can begin to bridge the differences in experiences and beliefs that are currently dividing us.

Individual observations

Each one of you made observations that all of us, regardless of age or experience, would do well to keep in mind. I chose one quote from each person and trust those reading your essays will discover more valuable insights.

“Our priorities may seem different, but they come back to basic human needs. We all desire a purpose, strive to be happy, and work to make a positive impact.”

“You can’t judge a person by what you think , you can only judge a person by what you know .”

Emily (referencing your interviewee, who is battling cancer):

“Master Chief Petty Officer James has shown me how to appreciate what I have around me.”

Lily (quoting your grandfather):

“Kindness makes the world go round.”

“Everything should matter to us.”

Praethong (quoting your interviewee, Sandra, on the importance of family):

“It’s important to always maintain that connection you have with each other, your family, not just next-door neighbors you talk to once a month.”

“I wonder if maybe we relearn what is most important when we grow older. That the pressure to be successful subsides and that valuing family, health, and happiness is what ends up saving the world.”

“Listen to what others have to say. Listen to the people who have already experienced hardship. You will learn from them and you can even make their day by giving them a chance to voice their thoughts.”

I end this letter to you with the hope that you never stop asking others what is most important to them and that you to continue to take time to reflect on what matters most to you…and why. May you never stop asking, listening, and connecting with others, especially those who may seem to be unlike you. Keep writing, and keep sharing your thoughts and observations with others, for your ideas are awe-inspiring.

I also want to thank the more than 1,000 students who submitted essays. Together, by sharing what’s important to us with others, especially those who may believe or act differently, we can fill the world with joy, peace, beauty, and love.

We received many outstanding essays for the Winter 2019 Student Writing Competition. Though not every participant can win the contest, we’d like to share some excerpts that caught our eye:

Whether it is a painting on a milky canvas with watercolors or pasting photos onto a scrapbook with her granddaughters, it is always a piece of artwork to her. She values the things in life that keep her in the moment, while still exploring things she may not have initially thought would bring her joy.

—Ondine Grant-Krasno, Immaculate Heart Middle School, Los Angeles, Calif.

“Ganas”… It means “desire” in Spanish. My ganas is fueled by my family’s belief in me. I cannot and will not fail them.

—Adan Rios, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

I hope when I grow up I can have the love for my kids like my grandma has for her kids. She makes being a mother even more of a beautiful thing than it already is.

—Ashley Shaw, Columbus City Prep School for Girls, Grove City, Ohio

You become a collage of little pieces of your friends and family. They also encourage you to be the best you can be. They lift you up onto the seat of your bike, they give you the first push, and they don’t hesitate to remind you that everything will be alright when you fall off and scrape your knee.

— Cecilia Stanton, Bellafonte Area Middle School, Bellafonte, Pa.

Without good friends, I wouldn’t know what I would do to endure the brutal machine of public education.

—Kenneth Jenkins, Garrison Middle School, Walla Walla, Wash.

My dog, as ridiculous as it may seem, is a beautiful example of what we all should aspire to be. We should live in the moment, not stress, and make it our goal to lift someone’s spirits, even just a little.

—Kate Garland, Immaculate Heart Middle School, Los Angeles, Calif.

I strongly hope that every child can spare more time to accompany their elderly parents when they are struggling, and moving forward, and give them more care and patience. so as to truly achieve the goal of “you accompany me to grow up, and I will accompany you to grow old.”

—Taiyi Li, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

I have three cats, and they are my brothers and sisters. We share a special bond that I think would not be possible if they were human. Since they do not speak English, we have to find other ways to connect, and I think that those other ways can be more powerful than language.

—Maya Dombroskie, Delta Program Middle School, Boulsburg, Pa.

We are made to love and be loved. To have joy and be relational. As a member of the loneliest generation in possibly all of history, I feel keenly aware of the need for relationships and authentic connection. That is why I decided to talk to my grandmother.

—Luke Steinkamp, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

After interviewing my grandma and writing my paper, I realized that as we grow older, the things that are important to us don’t change, what changes is why those things are important to us.

—Emily Giffer, Our Lady Star of the Sea, Grosse Pointe Woods, Mich.

The media works to marginalize elders, often isolating them and their stories, and the wealth of knowledge that comes with their additional years of lived experiences. It also undermines the depth of children’s curiosity and capacity to learn and understand. When the worlds of elders and children collide, a classroom opens.

—Cristina Reitano, City College of San Francisco, San Francisco, Calif.

My values, although similar to my dad, only looked the same in the sense that a shadow is similar to the object it was cast on.

—Timofey Lisenskiy, Santa Monica High School, Santa Monica, Calif.

I can release my anger through writing without having to take it out on someone. I can escape and be a different person; it feels good not to be myself for a while. I can make up my own characters, so I can be someone different every day, and I think that’s pretty cool.

—Jasua Carillo, Wellness, Business, and Sports School, Woodburn, Ore.

Notice how all the important things in his life are people: the people who he loves and who love him back. This is because “people are more important than things like money or possessions, and families are treasures,” says grandpa Pat. And I couldn’t agree more.

—Brody Hartley, Garrison Middle School, Walla Walla, Wash.

Curiosity for other people’s stories could be what is needed to save the world.

—Noah Smith, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

Peace to me is a calm lake without a ripple in sight. It’s a starry night with a gentle breeze that pillows upon your face. It’s the absence of arguments, fighting, or war. It’s when egos stop working against each other and finally begin working with each other. Peace is free from fear, anxiety, and depression. To me, peace is an important ingredient in the recipe of life.

—JP Bogan, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

From A Teacher

Charles Sanderson

Wellness, Business and Sports School, Woodburn, Ore.

The Birthday Gift

I’ve known Jodelle for years, watching her grow from a quiet and timid twelve-year-old to a young woman who just returned from India, where she played Kabaddi, a kind of rugby meets Red Rover.

One of my core beliefs as an educator is to show up for the things that matter to kids, so I go to their games, watch their plays, and eat the strawberry jam they make for the county fair. On this occasion, I met Jodelle at a robotics competition to watch her little sister Abby compete. Think Nerd Paradise: more hats made from traffic cones than Golden State Warrior ball caps, more unicorn capes than Nike swooshes, more fanny packs with Legos than clutches with eyeliner.

We started chatting as the crowd chanted and waved six-foot flags for teams like Mystic Biscuits, Shrek, and everyone’s nemesis The Mean Machine. Apparently, when it’s time for lunch at a robotics competition, they don’t mess around. The once-packed gym was left to Jodelle and me, and we kept talking and talking. I eventually asked her about the three things that matter to her most.

She told me about her mom, her sister, and her addiction—to horses. I’ve read enough of her writing to know that horses were her drug of choice and her mom and sister were her support network.

I learned about her desire to become a teacher and how hours at the barn with her horse, Heart, recharge her when she’s exhausted. At one point, our rambling conversation turned to a topic I’ve known far too well—her father.

Later that evening, I received an email from Jodelle, and she had a lot to say. One line really struck me: “In so many movies, I have seen a dad wanting to protect his daughter from the world, but I’ve only understood the scene cognitively. Yesterday, I felt it.”

Long ago, I decided that I would never be a dad. I had seen movies with fathers and daughters, and for me, those movies might as well have been Star Wars, ET, or Alien—worlds filled with creatures I’d never know. However, over the years, I’ve attended Jodelle’s parent-teacher conferences, gone to her graduation, and driven hours to watch her ride Heart at horse shows. Simply, I showed up. I listened. I supported.

Jodelle shared a series of dad poems, as well. I had read the first two poems in their original form when Jodelle was my student. The revised versions revealed new graphic details of her past. The third poem, however, was something entirely different.

She called the poems my early birthday present. When I read the lines “You are my father figure/Who I look up to/Without being looked down on,” I froze for an instant and had to reread the lines. After fifty years of consciously deciding not to be a dad, I was seen as one—and it felt incredible. Jodelle’s poem and recognition were two of the best presents I’ve ever received.

I know that I was the language arts teacher that Jodelle needed at the time, but her poem revealed things I never knew I taught her: “My father figure/ Who taught me/ That listening is for observing the world/ That listening is for learning/Not obeying/Writing is for connecting/Healing with others.”

Teaching is often a thankless job, one that frequently brings more stress and anxiety than joy and hope. Stress erodes my patience. Anxiety curtails my ability to enter each interaction with every student with the grace they deserve. However, my time with Jodelle reminds me of the importance of leaning in and listening.

In the article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age” by Nancy Hill, she illuminates how we “live among such remarkable people, yet few know their stories.” For the last twenty years, I’ve had the privilege to work with countless of these “remarkable people,” and I’ve done my best to listen, and, in so doing, I hope my students will realize what I’ve known for a long time; their voices matter and deserve to be heard, but the voices of their tias and abuelitos and babushkas are equally important. When we take the time to listen, I believe we do more than affirm the humanity of others; we affirm our own as well.