Here are 10 ways to fight corruption

Robert hunja.

4. It’s not 1999: Use the power of technology to build dynamic and continuous exchanges between key stakeholders: government, citizens, business, civil society groups, media, academia etc. 5. Deliver the goods: Invest in institutions and policy – sustainable improvement in how a government delivers services is only possible if the people in these institutions endorse sensible rules and practices that allow for change while making the best use of tested traditions and legacies – imported models often do not work. 6. Get incentives right: Align anti-corruption measures with market, behavioral, and social forces. Adopting integrity standards is a smart business decision, especially for companies interested in doing business with the World Bank Group and other development partners. 7. Sanctions matter: Punishing corruption is a vital component of any effective anti-corruption effort. 8. Act globally and locally: Keep citizens engaged on corruption at local, national, international and global levels – in line with the scale and scope of corruption. Make use of the architecture that has been developed and the platforms that exist for engagement. 9. Build capacity for those who need it most: Countries that suffer from chronic fragility, conflict and violence– are often the ones that have the fewest internal resources to combat corruption. Identify ways to leverage international resources to support and sustain good governance. 10. Learn by doing: Any good strategy must be continually monitored and evaluated to make sure it can be easily adapted as situations on the ground change. What are other ways we could fight corruption? Tell us in the comments.

- Digital Development

- Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management

- The World Region

Get updates from Governance for Development

Thank you for choosing to be part of the Governance for Development community!

Your subscription is now active. The latest blog posts and blog-related announcements will be delivered directly to your email inbox. You may unsubscribe at any time.

Director, Public Integrity and Openness

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Corruption is a Global Problem for Development. To Fight It, We All Have a Role to Play

Oped published in French in La Tribune Afrique, June 13, 2023.

Oped by Ousmane Diagana, World Bank Vice President for Western and Central Africa and Mouhamadou Diagne, World Bank Vice President for Integrity.

Every day, we hear about the onslaught of crises facing the world—from climate change to conflict, inflation and debt, and the ongoing recovery from a years-long pandemic. Add to them the prospect of slow economic growth , and our efforts to overcome these challenges seem rife with obstacles. For developing countries, many with limited and already stretched resources, the confluence of crises will be especially difficult to navigate.

But if we are to achieve success over the challenges of our time, there is one scourge we cannot fail to confront: corruption.

The unfortunate truth is that corruption persists in all countries. It manifests in many ways—from petty bribes and kickbacks to grand theft of public resources. With advances in technology, corruption has increasingly become a transnational challenge without respect for borders, as money can now move more easily in and out of countries to hide illicit gains.

Corruption is also a fundamental problem for development.

Corruption harms the poor and vulnerable the most, increasing costs and reducing access to basic services, such as health, education, social programs, and even justice. It exacerbates inequality and reduces private sector investment to the detriment of markets, job opportunities, and economies. Corruption can also undermine a country’s response to emergencies, leading to unnecessary suffering and, at worst, death. Over time, corruption can undermine the trust and confidence that citizens have for their leaders and institutions, creating social friction and in some contexts increasing the risk of fragility, conflict, and violence.

To prevent these negative impacts, we must confront corruption with determined and deliberate action. For the World Bank Group, fighting corruption in development has been a long-standing commitment in our operational work. This commitment is reflected in our support for countries in building transparent, inclusive, and accountable institutions , but also through initiatives that go beyond developing countries to also include financial centers, take on the politics of corruption more openly than before, and harness new technologies to understand, address, and prevent corruption.

Indeed, across western and central Africa in particular, it is one of the World Bank Group’s strategic priorities to emphasize issues of good governance, accountability, and transparency among our partner countries, with the aim of reducing corruption. We recognize that transparency in public affairs and the accountability of high-level officials are fundamental to the trust of citizens in their government and the effective delivery of public services. Working to rebuild and bolster trust between citizens and the state is critical today, especially in countries affected by fragility, conflict and violence that make up half of the countries in this region alone.

Across Africa, World Bank Group support is helping countries face these challenges. Recent investments in the Republic of Congo , Ghana , and Morocco , for example, will support institutional governance reforms to improve the performance and transparency of service delivery. In Kenya, our support will further fiscal management reforms for greater transparency in public procurement , thereby reducing opportunities for corruption. Strengthening citizen-state engagement is key: In Burkina Faso, for example, a World Bank-funded project helped the national government improve citizen engagement and public sector accountability through the development of a digital tool to monitor the performance of municipal service delivery.

The World Bank Group’s commitment to fighting corruption is also reflected in robust mechanisms across the institution that enhance the integrity of our operations. Our independent Integrity Vice Presidency (INT) works to detect, deter, and prevent fraud and corruption involving World Bank Group funds. Over two decades of INT’s work, the World Bank has sanctioned more than 1,100 firms and individuals, often imposing debarments that make them ineligible to participate in the projects and operations we finance. In addition, we have enforced more than 640 cross-debarments from other multilateral development banks, standing with our MDB partners to help keep corruption out of development projects everywhere. Nevertheless, we must remain vigilant to the risks of fraud and corruption that remain.

The World Bank Group also leverages its position as global convener to support anticorruption actors at all levels and from around the world. That is why we are pleased to have organized the next edition of the World Bank Group’s International Corruption Hunters Alliance (ICHA) to take place in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, on June 14-16, 2023.

The ICHA forum is an opportunity for front-line practitioners committed to fighting corruption as well as policy makers and representatives from the private sector and civil society, to come together to share knowledge, experience, and insights for confronting corruption. For the first time since its inception in 2010, we are hosting the ICHA forum in an African country. This reflects the reality that the negative impacts of corruption can be more devastating for developing countries, who face unique challenges and have fewer resources to overcome them. Yet, it also acknowledges that there is a wealth of anticorruption strengths, skills, and expertise from these countries that we must draw upon.

Together, we can affirm that through our collective action, we can advance the fight against corruption even in an era of crises.

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Seven Steps to Control of Corruption: The Road Map

After a comprehensive test of today’s anticorruption toolkit, it seems that the few tools that do work are effective only in contexts where domestic agency exists. Therefore, the time has come to draft a comprehensive road map to inform evidence-based anticorruption efforts. This essay recommends that international donors join domestic civil societies in pursuing a common long-term strategy and action plan to build national public integrity and ethical universalism. In other words, this essay proposes that coordination among donors should be added as a specific precondition for improving governance in the WHO’s Millennium Development Goals. This essay offers a basic tool for diagnosing the rule governing allocation of public resources in a given country, recommends some fact-based change indicators to follow, and outlines a plan to identify the human agency with a vested interest in changing the status quo. In the end, the essay argues that anticorruption interventions must be designed to empower such agency on the basis of a joint strategy to reduce opportunities for and increase constraints on corruption, and recommends that experts exclude entirely the tools that do not work in a given national context.

ALINA MUNGIU-PIPPIDI is Professor of Democracy Studies at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin. She chairs the European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building (ERCAS), where she managed the FP7 research project ANTICORRP. She is the author of The Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption (2015) and A Tale of Two Villages: Coerced Modernization in the East European Countryside (2010).

T he last two decades of unprecedented anticorruption activity – including the adoption of an international legal framework, the emergence of an anticorruption civil society, the introduction of governance-related aid conditionality, and the rise of a veritable anticorruption industry – have been marred by stagnation in the evolution of good governance, ratings of which have remained flat for most of the countries in the world.

The World Bank’s 2017 Control of Corruption aggregate rating showed that twenty-two countries progressed significantly in the past twenty years and twenty-five regressed. Of the countries showing progress on corruption, nineteen were rated as either “free” or “partly free” by Freedom House (a democracy watchdog that measures governance via political rights and civil liberties); only seven were judged “not free.” 1 Our governance measures are too new to allow us to look further into the past; still, it seems that governance change has much in common with climate change: it occurs only slowly, and the role that humans play involuntarily seems always to matter more than what they do with intent.

External aid and its attached conditionality are considered an essential component of efforts to enable developing countries to deliver decent public services on the principle of ethical universalism (in which everyone is treated equally and fairly). However, a panel data set (collected from 110 developing countries that received aid from the European Union and its member states between 2002 and 2014) shows little evolution of fair service delivery in countries receiving conditional aid. Bilateral aid from the largest European donors does not have significant impact on governance in recipient countries, while multilateral financial assistance from EU institutions such as the Office of Development Assistance (which provides aid conditional on good governance) produces only a small improvement in the governance indicators of the net recipients. Dedicated aid to good-governance and corruption initiatives within multilateral aid packages has no sizable effect, whether on public-sector functionality or anticorruption. 2 Countries like Georgia, Vanuatu, Rwanda, Macedonia, Bhutan, and Uruguay, which have managed to evolve more than one point on a one-to-ten scale from 2002 to 2014, are outliers. In other words, they evolved disproportionately given the EU aid per capita that they received, while countries that received the most aid (such as Turkey, Egypt, and Ukraine) had rather disappointing results.

So how, if at all, can an external actor such as a donor agency influence the transition of a society from corruption as a governance norm , wherein public resource distribution is systematically biased in favor of authority holders and those connected with them, to corruption as an exception , a state that is largely independent from private interest and that allocates public resources based on ethical universalism? Can such a process be engineered? How do the current anticorruption tools promoted by the international community perform in delivering this result?

Looking at the governance progress indicators outlined above, one might wonder whether efforts to change the quality of government in other countries are doomed from the outset. The incapacity of international donors to help push any country above the threshold of good governance during the past twenty years of the global crusade against corruption seems over- rather than under-explained. For one, corrupt countries are generally run by corrupt people with little interest in killing their own rents, although they may find it convenient to adopt international treaties or domestic legislation that are nominally dedicated to anticorruption efforts. Furthermore, countries in which informal institutions have long been substituted for formal ones have a tradition of surviving untouched by formal legal changes that may be forced upon them. One popular saying from the post-Soviet world expresses the view that “the inadequacy of the laws is corrected by their non-observance.” 3

Explicit attempts of donor countries and international organizations to change governance across borders might appear a novel phenomenon, but are they actually so very different from older endeavors to “modernize” and “civilize” poorer countries and change their domestic institutions to replicate allegedly superior, “universal” ones? Describing similar attempts by the ancient Greeks – and also their rather poor impact – historian Arnaldo Momigliano writes: “The Greeks were seldom in a position to check what natives told them: they did not know the languages. The natives, on the other hand, being bilingual, had a shrewd idea of what the Greeks wanted to hear and spoke accordingly. This reciprocal position did not make for sincerity and real understanding.” 4

Many factors speak against the odds of success of international donors’ efforts to change governance practices, especially government-funded ones. One such factor is the incentives facing donor countries themselves: they want first and foremost to care for national companies investing abroad and their business opportunities; reduce immigration from poor countries; and generate jobs for their development industry. Even if donor countries would prefer that poor countries govern better, reduce corruption, and adopt Western values, they also have to play their cards realistically. Thus, donor countries often end up avoiding the root of the problem: when the choice is between their own economic interests and more idealistic commitments to better governance, the former usually wins out.

T he first question a policy analyst should ask, therefore, is not how to go about altering governance in developing countries, but whether the promotion of good governance and anticorruption is worth doing at all, self-serving reasons aside. I have addressed these questions in greater detail elsewhere; this essay assumes a donor has already made the decision to intervene. 5 The evidence on the basis of which such decisions are made is often poor, but realistically, due to the other policy objectives mentioned above (such as the exigencies of participation in the global economy), international donors will continue to give aid systematically to corrupt countries. As long as one thinks a country is worth granting assistance to, preventing aid money from feeding corruption in the recipient country becomes an obligation to one’s own taxpayers. For the sake of the recipient country, too, ensuring that such money is used to do good, rather than actually to funnel more resources into local informal institutions and predatory elites, seems more of an obligation than a choice.

While our knowledge of how to establish a norm of ethical universalism is still far from sufficient, I will outline a road map toward making corruption the exception rather than the rule in recipient countries. To do so, I draw on one of the largest social-science research projects undertaken by the European Union, ANTICORRP, which was conducted between 2013 and 2017 and was dedicated to systematically assessing the impact of public anticorruption tools and the contexts that enable them. I follow the consequences of the evidence to suggest a methodology for the design of an anticorruption strategy for external donors and their counterparts in domestic civil societies. 6

Many anticorruption policies and programs have been declared successful, but no country has yet achieved control of corruption through the prescriptions attached to international assistance. 7 To proceed, we must also clarify what constitutes “success” in anticorruption reforms. Success can only mean a consolidated dominant norm of ethical universalism and public integrity. Exceptions, in the form of corrupt acts, will always remain, but if they are numerous enough to be the rule, a country cannot be called an achiever. A successful transformation requires both a dominant norm of public integrity (wherein the majority of acts and public officials are noncorrupt) and the sustainability of that norm across at least two or three electoral cycles.

Q uite a few developing countries presently seem to be struggling in a borderline area in which old and new norms confront one another. This is why popular demand for leadership integrity has been loudly proclaimed in headlines from countries such as South Korea, India, Brazil, Bulgaria, and Romania, but substantially better quality of governance has yet to be achieved there. While the solutions for each and every country will ultimately come from the country itself – and not from some universal toolkit – recent research can contribute to a road map for more evidence-based corruption control.

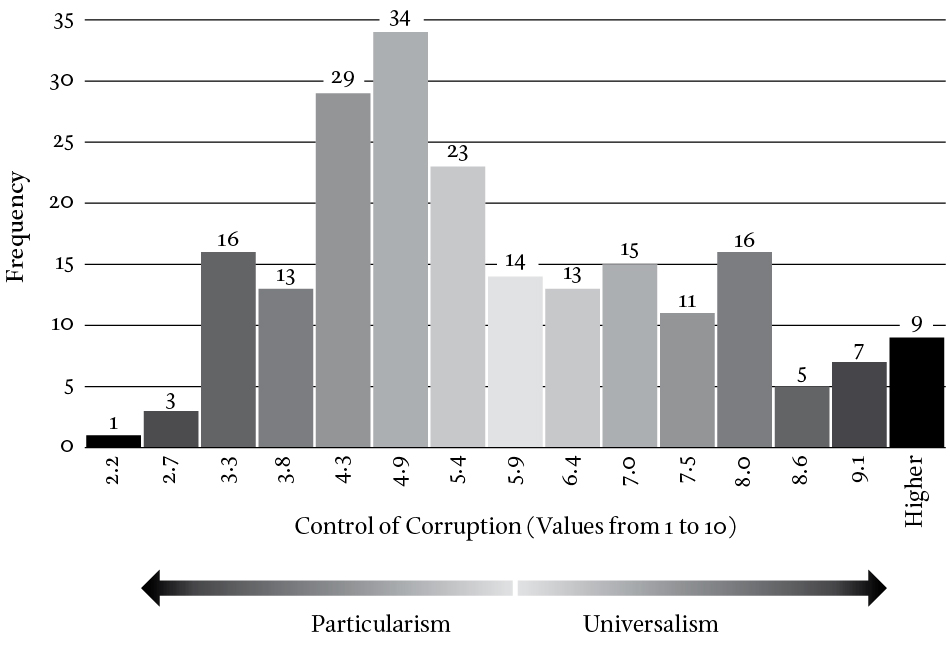

The first step is to understand that with the exception of the developed world, control of corruption has to be built from the ground up, not “restored.” Most anticorruption approaches are built on the concept that public integrity and ethical universalism are already global norms of governance. This is wrong on two counts, and leads to policy failure. First, at the present moment, most countries are more corrupt than noncorrupt. A histogram of corruption control shows that developing countries range between two and six on a one-to-ten scale, with some borderline cases in between (see Figure 1). Countries scoring in the upper third are a minority, so a development agency is more likely than not to be dealing with a situation in which corruption is not only a norm but an institutionalized practice. Development agencies need to understand corruption as a social practice or institution, not just as a sum of individual corrupt acts. Further, presuming that ethical universalism is the default is wrong from a developmental perspective, since even countries in which ethical universalism is the governance norm were not always this way: from sales of offices to class privileges and electoral corruption, the histories of even the cleanest countries show that good governance is the product of evolution, and modernity a long and frequently incomplete endeavor to develop state autonomy in the face of private group interests.

Figure 1 Particularism versus Ethical Universalism: Distribution of Countries on the Control of Corruption Continuum

Source: The World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, Control of Corruption, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home distribution . Distribution recoded 1–10 (with Denmark 10). The number of countries for each score is noted on each column.

Institutionalized corruption is based on the informal institution of particularism (treating individuals differently according to their status), which is prevalent in collectivistic and status-based societies. Particularism frequently results in patrimonialism (the use of public office for private profit), turning public office into a perpetual source of spoils. 8 Public corruption thrives on power inequality and the incapacity of the weak to prevent the strong from appropriating the state and spoiling public resources. Particularism encompasses a variety of interpersonal and personal-state transaction types, such as clientelism, bribery, patronage, nepotism, and other favoritisms, all of which imply some degree of patrimonialism when an authority-holder is concerned. Particularism not only defines the relations between a government and its subjects, but also between individuals in a society; it explains why advancement in a given society might be based on status or connections with influential people rather than on merit.

The outcome associated with the prevalence of particularism – a regular pattern of preferential distribution of public goods toward those who hold more power – has been termed “limited-access order” by economists Douglass North, John Wallis, and Barry Weingast; “extractive institutions” by economist Daron Acemoglu and political scientist James Robinson; and “patrimonialism” by political scientist Francis Fukuyama. 9 Essentially, though, all these categories overlap and all the authors acknowledge that particularism rather than ethical universalism is closer to the state of nature (or the default social organization), and that its opposite, a norm of open and equal access or public integrity, is by no means guaranteed by political evolution and indeed has only ever been achieved in a few cases thus far. The first countries to achieve good control of corruption – among them Britain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Prussia – were also the first to modernize and, in Max Weber’s term, to “rationalize.” This implies an evolution from brutal material interests (espoused, for instance, by Spanish conquistadors who appropriated the gold and silver of the New World) to a more rationalistic and capitalistic channeling of economic surplus, underpinned by an ideology of personal austerity and achievement. The market and capitalism, despite their obvious limitations, gradually emerged in these cases as the main ways of allocating resources, replacing the previous system of discretionary allocation by means of more or less organized violence. The past century and a half has seen a multitude of attempts around the world to replicate these few advanced cases of Western modernization. However, a reduction in the arbitrariness and power discretion of rulers, as occurred in the West and some Western Anglo-Saxon colonies, has not taken place in many other countries, regardless of whether said rulers were monopolists or won power through contested elections. Despite adopting most of the formal institutions associated with Western modernity – such as constitutions, political parties, elections, bureaucracies, free markets, and courts – many countries never managed to achieve a similar rationalization of both the state and the broader society. 10 Many modern institutions exist only in form, substituted by informal institutions that are anything but modern. That is why treating corruption as deviation is problematic in developing countries: it leads to investing in norm-enforcing instruments, when the norm-building instruments that are in fact needed are quite different. Strangely enough, developed countries display extraordinary resistance to addressing corruption as a development-related rather than moral problem. This is why our Western anticorruption techniques look much like an invasion of the temperance league in a pub on Friday night: a lot of noise with no consequence. Scholars contribute to the inefficacy of interventions by perpetuating theoretical distinctions that are of poor relevance even in the developed world (such as “bureaucratic versus political” or “grand versus petty” corruption), which inform us only of the opportunities that somebody has to be corrupt. As those opportunities simply vary according to one’s station in life (a minister exhorting an energy company for a contract is simply using his grand station in a perfectly similar way to a petty doctor who required a gift to operate or a policeman requiring a bribe not to give a fine), such distinctions are not helpful or conceptually meaningful. In countries where the practice of particularism is dominant, disentangling political from bureaucratic corruption also does not work, since rulers appoint “bureaucrats” on the basis of personal or party allegiance and the two collude in extracting resources. Even distinguishing victims from perpetrators is not easy in a context of institutionalized corruption. In a developing country, an electricity distribution company, for instance, might be heavily indebted to the state but still provide rents (such as well-paid jobs) to people in government and their cronies and eventually contribute funds to their electoral campaigns. For their part, consumers defend themselves by not paying bills and actually stealing massively from the grid, and controllers take moderate bribes to leave the situation as it is. The result is constant electricity shortages and a situation to which everybody (or nearly everybody) contributes, and which has to be understood and addressed holistically and not artificially separated into types of corruption.

The second step is diagnosing the norm. If we conceive governance as a set of formal rules and informal practices determining who gets which public resources, we can then place any country on a continuum with full particularism at one end and full ethical universalism at the other. There are two main questions that we have to answer. What is the dominant norm (and practice) for social allocation: merit and work, or status and connections to authority? And how does this compare to the formal norm – such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), or the country’s own regulation – and to the general degree of modernity in the society? For instance, merit-based advancement in civil service may not work as the default norm, but it may in the broader society, for instance in universities and private businesses. The tools to begin this assessment are the Worldwide Governance Indicator Control of Corruption, an aggregate of all perception scores (Figure 1); and the composite, mostly fact-based Index for Public Integrity that I developed with my team (which is highly correlated with perception indicators). Any available public-opinion poll on governance can complete the picture (one standard measure is the Global Corruption Barometer, which is organized by Transparency International). Simply put, the majority of respondents in countries in the upper tercile of the Control of Corruption indicators feel that no personal ties are needed to access a public service, while those in the lower two-thirds will in all likelihood indicate that personal connections or material inducement are necessary (albeit in different proportions). Within the developed European Union, only in Northern Europe does a majority of citizens believe that the state and markets work impartially. The United States, developed Commonwealth countries, and Japan round out the top tercile. The next set of countries, around six and seven on the scale, already exhibit far more divided public opinion, showing that the two norms coexist and possibly compete. 11 In countries where the norm of particularism is dominant and access is limited, surveys show majorities opining that government only works in the favor of the few; that people are not equal in the eyes of the law; and that connections, not merit, drive success in both the public and private sectors. Bribery often emerges as a substitute for or a complement to a privileged connection; when administration discretion is high, favoritism is the rule of the game, so bribes may be needed to gain access, even for those with some preexisting privilege. A thorough analysis needs to determine whether favoritism is dominant and how material and status-based favoritism relate to one another in order to weigh useful policy answers. Are they complementary, compensatory, or competitive? When the dominant norm is particularistic, collusive practices are widespread, including not only a fusion of interests between appointed and elected office holders and civil servants more generally, but also the capture of law enforcement agencies.

The second step, diagnosis, needs to be completed by fact-based indicators that allow us to trace prevalence and change. Fortunately for the analyst (but unfortunately for everyone else), since corrupt societies are, in Max Weber’s words, status societies , where wealth is only a vehicle to obtain greater status, we do not need Panama-Papers revelations to see corruption. Systematic corrupt practices are noticeable both directly and through their outcomes: lavish houses of poorly paid officials, great fortunes made of public contracts, and the poor quality of public works. Particularism results in privilege to some (favoritism) and discrimination to others, outcomes that can both be measured. 12

Table 1 illustrates how these two contexts – corruption as norm and corruption as exception – differ essentially, and shows that different measures must be taken to define, assess, and respond to corruption in either case. An individual is corrupt when engaging in a corrupt act, regardless of whether he or she is a public or private actor. The dominant analytic framework of the literature on corruption is the principal-agent paradigm, wherein agents (for example government officials) are individuals authorized to act on behalf of a principal (for example a government). To diagnose an organization or a country as “corrupt,” we have to establish that corruption is the norm: in other words, that corrupt transactions are prevalent. When such practices are the exception, the corrupt agent is simply a deviant and can be sanctioned by the principal if identified. When such practices are the norm, corruption occurs on an organized scale, extracting resources disproportionately in favor of the most powerful group. Telling the principal from the agent can be quite impossible in these cases due to generalized collusion (the organization is by privileged status groups, patron-client pyramids, or networks of extortion) and fighting corruption means solving social dilemmas and issues around discretionary use of power. Most people operate by conformity, and conformity always works in favor of the status quo: if ethical universalism is already the norm in a society, conformity helps to enforce public integrity; if favoritism and clientelism are the norm, few people will dissent. The difference between corruption as a rule and corruption as a norm shows in observable, measurable phenomena. In contexts with clearer public-private separation, it is more difficult to discover corrupt acts, requiring whistleblowers or some time for a conflict of interest to unfold (as with revolving doors, through which the official collects benefits from his favor by getting a cushy job later with a private company). In contexts where patrimonialism is widespread, there is no need for whistleblowers: officials grant state contracts to themselves or their families, use their public car and driver to take their mother-in-law shopping, and so forth – all in publicly observable displays (see Table 1).

Table 1 Corruption as Governance Context

| Corruption as Exception | Corruption as Norm | |

| Definition | Individual abuses public authority to gain undue private profit. | Social practice in which particularism (as opposed to ethical universalism) informs the majority of government transactions, resulting in widespread favoritism and discrimination. |

| Visibility | Corruption unobservable; whistleblowing needed. | Corruption is observable as overt behaviors and flawed processes, as well as through outcomes/consequences; monitoring and curbing impunity needed. |

| Public-Private Separation | Enshrined. Access is permitted via lobby, and exchanges between the sides are consequent in time (revolving doors). | Permeable border, with patrimonialism and conflict of interest ubiquitous. Exchanges between the sides are synchronous (one person belongs to both sides at the same time). |

| Preferred Observation Level | Micro and qualitative (for example, lobby studies). | Macro (how many bills are driven by special interest, how many contracts awarded by favoritism, how many officials are corrupt, and so on). |

Efforts to measure corruption should aim at gauging the prevalence of favoritism, measuring how many transactions are impersonal and by-the-book, and how many are not. Observations for measurement can be drawn from all the transactions that a government agency, sector, or entire state engages in, from regulation to spending. The results of these observations allow us to monitor change over time in a country’s capacity to control corruption. Even anecdotal evidence can be a good way to gauge changes to corruption over long periods: twenty years ago, for example, it was customary even in some developed countries for companies bidding for public contracts to consult among themselves; today this is widely understood to be a collusive practice and has been made illegal in many countries. These indicators signal essential changes of context that we need to trace in developing countries and indeed to use to create our good governance targets. If in a given country it is presently customary to pay a bribe to have a telephone line installed, the target is to make this exceptional.

In my previous work, I have given examples of such indicators of corruption norms, including the particularistic distribution of funds for natural disasters, comparisons of turnout and profit for government-connected companies versus unconnected companies, the changing fortunes of market leaders after elections, and the replacement of the original group of market leaders (those connected to the losing political clique) by another well-defined group of market leaders (those connected with election winners). The data sources for such measurements are the distribution of public contracts, subsidies, tax breaks, government subnational transfers; in short, basically any allocation of public resources, including through legislation (laws are ideal instruments to trade favors for personal profit). If such data exist in a digital format, which is increasingly the case in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and even China, it becomes feasible to monitor, for example, how many public contracts go to companies belonging to officials or how many people put their relatives on public payrolls. Ensuring that data sources like these are made open and universally accessible by public or semipublic entities (such as government and Register of Commerce data) is itself a valid and worthy target for donors. The method works even when data are not digitized: through simple requests for information, as most countries in the world have freedom of information acts. Inaccessibility of public data opens an entire avenue for donor action unto itself: supporting freedom-of-information legislation also supports anticorruption efforts, since lack of transparency and corruption are correlated.

N ow that targets have been established, the fourth step is solving the problem of domestic agency. By and large, countries can achieve control of corruption in two ways. The first is surreptitious: policy-makers and politicians change institutions incrementally until open access, free competition, and meritocracy become dominant, even though that may not have been a main collective goal. This has worked for many developed countries in the past. The second method is to make a concerted effort to foster collective agency and investment in anticorruption efforts specifically, eventually leading to the rule of law and control of corruption delivered as public goods. This can occur after sustained anticorruption campaigns in a country where particularism is engrained. Both paths require human agency. In the former, the role of agency is small. Reforms slip by with little opposition, since they are not perceived as being truly dangerous to anybody’s rents, and do not therefore need great heroism to be pushed through; just common sense, professionalism, and a public demand for government performance. The latter scenario, however, requires considerable effort and alignment of both interests favoring change and an ideology of ethical universalism. Identifying the human agency that can deliver the change therefore becomes essential to selecting a well-functioning anticorruption strategy.

Changing governance across borders is a difficult task even under military occupation. Leaving external actors aside, a country’s governance can push corruption from norm to exception either through the actions of an enlightened despot (the king of Denmark model beginning in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), an enlightened elite (as in the British and American cases), or by an enlightened mass of citizens (the famous “middle class” of political modernization theory). Enlightened despots do appear periodically (the kingdom of Bhutan is the current example of shining governance reforms, after the classic example of Botswana, where the chief of the largest tribe became a democratically elected president). Enlightened elites can perhaps be engineered (this is what George Soros and the Open Society Foundation have tried to do, with one of the results being a great mobilization against elites in less democratic countries), and countries that have them (like Estonia, Georgia, Chile, and Uruguay) have evolved further than their neighbors. Enlightened and organized citizens must reach a critical mass; and regardless how strong a demand for good governance they put up, they cannot do much without an alternative and autonomous elite that is able to take over from the corrupt one. As the recent South Korean case has proved, entrusting power at the top to former elites leads to an immediate return to former practices; however, in that case, the society had sufficiently evolved in the interval to defend itself.

In principle, donors can work with enlightened despots, attempt to socialize enlightened elites to some extent, and help civil society and “enlightened” citizens. But, in practice, this does not go so well. Donors seem by default to treat every corrupt government as though it were run by an enlightened despot, entrusting it with the ownership of anticorruption programs. These, of course, will never take off, not only because they are more often than not the wrong programs, but because implementing them would run counter to the main interests of these principals. Additionally, this approach is not sustainable: pro-Western elites are so scarce these days that checking their anticorruption credentials often becomes problematic. Take the tiny post-Soviet republic of Moldova, which could never afford to punish anyone from the Russian-organized crime syndicates that control part of its economy and even a breakaway province thriving on weapons smuggling. Due to international anticorruption efforts, a prime minister was jailed for eight years for “abuse of function” – actually for failing to prevent cybercrime – despite the fact that he held pro-EU policy goals. The better and less repressive approach – designing anticorruption interventions that include society actors as main stakeholders by default, not just working with governments – is rather exceptional, although such an approach might greatly enhance the effectiveness of aid programs in general.

The remaining option, building a critical mass from bottom up, is not easy either, as it basically means competing with patronage and client networks that have a lot to offer the average citizen. “Incentivizing,” another anticorruption-industry buzzword, is really a practical joke. No anticorruption incentive can compete with a diamond mine, a country’s oil income, or, indeed, its whole budget, including assistance funds. Despoilers generally control those rents and distribute them wisely to stay in control. Anticorruption is not a win-win game, it is a game played by societies against their despoilers, and when building accountability, not everybody wins. But if in contemporary times countries like Estonia, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Taiwan, Chile, Slovenia, Botswana, and even Georgia are edging over the threshold of good governance through their own agency, we must maintain hope that others can follow.

W e see all around the world that demand for good governance and participation in anticorruption protests have increased – just not sufficiently to change governance. Perhaps there was not enough middle-class growth in the last two decades for that: the Pew Research Center found that between 2001 and 2011, nearly seven hundred million people escaped poverty but did not travel far up enough to be labeled middle-class. 13 Fortunately, the development of smartphones with Internet access provides a great shortcut to fostering individual autonomy and achieving enlightened participation.

Any assistance in increasing the percentage of “enlightened citizens” armed with smartphones is helpful in creating grassroots demand for government transparency; this is why both Internet access and ownership of smartphones are strongly associated with control of corruption. 14 But for our transition strategy we need more: careful stakeholder analysis and coalition building. Brokers of corrupt acts and practitioners of favoritism are not hidden in corrupt societies. Losers are more difficult to find; today’s losers may be tomorrow’s clients. As a ground rule, however, whoever wishes to engage in fair, competitive practices – whether in business or politics – stands to lose in a particularistic society. He or she faces two options: to desert for a more meritocratic realm (hence the close correlation between corruption and brain drain) or to fight. These are our recruitment grounds. It is essential to understand who is invested in challenging the rules of the game and who is invested in defending them; in other words, who are the status quo losers and winners? Who, among the winners, would stay a winner even if more merit-based competition were allowed? Who among the losers would gain? These are the groups that must come together to empower merit and fair competition.

By now, enough evidence should exist to support a theory of change, which in turn informs our strategy. To understand when the status quo will change, we need a theory of why it would change, who would push for the desired evolution, and how donors can assist them to steer the country to a virtuous circle. The main theories informing intervention presently are very general: modernization theory (the theory that increases in education and economic development bring better governance) and state modernization (the belief that building state capacity will also resolve integrity problems). But as there is a very close negative correlation between rule of law and control of corruption, it is the case more often than not that rule of law is absent where corruption is high, so legal approaches to anticorruption (like anticorruption agencies or strong punitive campaigns) can hardly be expected to deliver. 15 The same goes for civil-service capacity building in countries where bureaucracy has never gained its autonomy from rulers. Good governance requires autonomous classes of magistrates and of bureaucrats. These cannot be delivered by capacity-building in the absence of domestic political agency or some major loss of power of ruling elites that could empower bureaucrats. 16 This is why the accountability tools that work in our statistical assessments are those associated with civil-society agency. Voluntary implementation of accountability tools by interested groups (businesses who lose public tenders, for instance, or journalists seeking an audience) works better than implementation by government, which is always found wanting by donors.

In our recent work, my colleagues and I tested a broad panel of anticorruption tools and good governance policies from the World Bank’s Public Accountability Mechanism database. The panel includes nearly all instruments that are either frequently used in practice or specified in the UNCAC: anticorruption agencies, ombudsmen, freedom of information laws (FOIs), immunity protection limitations, conflict of interest legislation, financial disclosures, audit infrastructure improvements, budgetary transparency, party finance restrictions, whistleblower protections, and dedicated legislation. 17 The evidence so far shows that countries that adopt autonomous anticorruption agencies, restrictive party finance legislation, or whistleblower protection acts make no more progress on corruption than countries that do not. 18 The comprehensiveness of anticorruption regulation does not seem to matter either: in fact, the cleanest countries have moderate regulation and excessive regulation is actually associated with more corruption; what matters are the legal arrangements used to generate privileges and rents. In other words, it may well be that a country’s specific anticorruption legislation matters far less in ensuring good control of corruption than its overall “regulatory quality,” which might result precisely from a long process of controlled rent creation and profiteering. 19

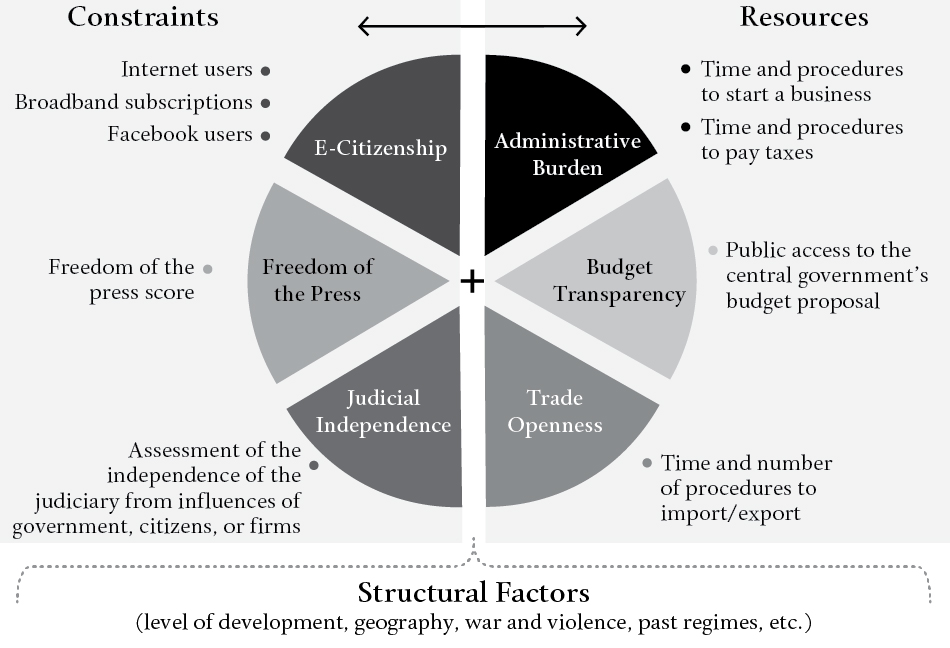

Actually, as I have already argued, the empirical evidence suggests corruption control is best described as an equilibrium between opportunities (or resources) for corruption, such as natural resources, unconditional aid, lack of government transparency, administrative discretion, and obstacles to trade, and constraints on corruption, whether legal (an autonomous judiciary and audit) or normative (by the media and civil society). 20 Not only is each element highly influential on corruption, but statistical relationships between resources and constraints are highly significant. Examples include the inverse relationship between red tape and the independence of the judiciary and between transparency in any form (fiscal transparency, existence of an FOI, or financial disclosures) and the direct relationship between civil society activism and press freedom. Using this model, my colleagues and I designed an elegant composite index for public integrity for 109 countries based on policy determinants of control of corruption (which should be seen as the starting point of any diagnosis, since it shows at a first glance where the balance between opportunities and constraints goes wrong). While even evidence-based comparative measures can be criticized for ignoring cross-border corrupt behavior (like hiding corrupt income offshore), from a policy perspective, it still makes the most sense to keep national jurisdiction as the main comparison unit. Basically every anticorruption measure that would limit international resources for corruption is in the power of some national government.

Let’s take the well-known example of Tunisia, whose revolution was catalyzed in late 2010 by an unlicensed street vendor who immolated himself to protest against harassment by local police. Corruption – as inequity of social allocation induced and perpetuated by the government – was one of the main causes of protests. Has the fall of President Ben Ali and his cronies made Tunisians happy? No, because there are as many unemployed youths as before, equally lacking in jobs and hope, and the maze of obstructive regulation and rent seekers who profit by it are the same. If we check Tunisia against countries in its region and income group on the Index of Public Integrity, we see that the revolution has only brought significant progress on press freedom and trade openness. On items such as administrative burden, fiscal transparency, and quality of regulation, the country still has much to do to bring the economy out of the shadows and restore a social contract between society and the state (see Table 2). To get there, policies are needed both to bring the street vendors into the licensed, tax-paying world and to reduce the discretion of policemen.

Examples of specific, successful legislative initiatives exist in the handful of achievers we identified through our measurement index: Uruguay and Georgia, for instance, which have implemented soft formalization policies, tax simplification, and police reform. This is the correct path to follow to control corruption successfully. In a context of generalized lawbreaking fostered by unrealistic legislation, selective enforcement becomes inevitable, and then even anticorruption laws can generate new rents and protect existing ones, reproducing rather than changing the rules of the game. One cannot expect isolated anticorruption measures to work unless opportunities and constraints are brought into balance. For instance, one cannot ask Nigeria to create a register for foreign-owned businesses in order to trace beneficial ownership (as is the standard procedure for anticorruption consultants) without formalizing and registering (hopefully electronically) all property in Nigeria, a long-standing development goal with important implications for corruption. It is quite important, therefore, that we understand and act on both sides of this balance. Working on just one side only creates more distance between formal and informal institutions, which is already a serious problem in corrupt countries.

Figure 2 Control of Corruption as Interaction between Resources and Constraints

Source: Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Ramin Dadasov, “Measuring Control of Corruption by a New Index of Public Integrity,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (3) (2016).

Table 2 Tunisia’s Public Integrity Framework

| Component Score | World Rank (of 109) | Regional Rank (of 8) | Income Group Rank (of 28) | |

| Judicial Independence | 5.34 | 55 | 5 | 11 |

| Administrative Burden | 8.77 | 47 | 3 | 8 |

| Trade Openness | 7.1 | 76 | 3 | 21 |

| Budget Transparency | 6.79 | 71 | 2 | 20 |

| E-Citizenship | 5.22 | 60 | 5 | 19 |

| Freedom of the Press | 5.16 | 65 | 1 | 14 |

Note: On the Index of Public Integrity, Tunisia scores 6.40 on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 as the best, and ranks 59th out of 109 countries. Source: Index of Public Integrity, 2015, http://www.integrity-index.org .

The sixth step on the road map is for international donors to get together to implement a strategy to fix this imbalance. In the same way the Millennium Development goals required coordination and multiyear planning, making the majority of transactions clean rather than corrupt requires long-term strategic planning. The goals are not just to reduce corruption with isolated interventions, but to build public integrity in many countries – a clear development goal – and to refrain from punishing deviation. The joint planners of such efforts should begin by sponsoring a diagnostic effort using objective indicators and subsequently launch coordinated efforts to reduce resources and increase constraints. This collaboration-based approach also allows donors to diversify their efforts, as some may have strengths in building civil society, others in market development reforms, and others still in increasing Internet access. Freedom of the press receives insufficient support, and seldom the kind it needs (what media needs in corrupt countries is clean media investment, not training for investigative journalists).

Finally, international donors must set the example. They should publicize what they fund and how they structure the process of aid allocation itself. Those at the apex of the donor-coordination strategy ought to agree upon aid-related good-governance conditions and enforce them across the board. Aid recipients – including particular governments, subnational government units or agencies, and aid intermediaries – should qualify for receiving aid transfers only if they publish in advance all their calls for tenders and their awards, which would allow monitoring the percentage of transparent and competitive bids out of the total procurement budget. Why not make the full transparency of all recipients the main condition for selection? Such indicators could also be useful to trace evolution (or lack thereof) from one year to another. On top of this, using social accountability more decisively, for instance by involving pro-change local groups in planning and audits of aid projects, would also empower these groups and set an example for how local stakeholders should monitor public spending. These gestures of transparency and inclusiveness toward the societies that donors claim to help – and not just their rulers – would bring real benefits for both sides and enhance the reputation of development aid.

1 Count based on the Worldwide Governance Indicator Control of Corruption recoded on a scale of 1 to 10, with the best performer rated 10.

2 Ramin Dadasov, “European Aid and Governance: Does the Source Matter?” The European Journal of Development Research 29 (2) (2017): 269–288.

3 Cited in Alena V. Ledeneva, How Russia Really Works: The Informal Practices that Shaped Post-Soviet Politics and Business (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2006).

4 Arnaldo Momigliano, Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 8.

5 See Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, A Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

6 See Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Ramin Dadasov, “When Do Anticorruption Laws Matter? The Evidence on Public Integrity,” Crime, Law, and Social Change 68 (4) (2017): 1 – 16. I am grateful to Sweden’s Expert Group for Aid Studies (EBA) for funding this research and for helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. See Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, Seven Steps to Evidence-Based Anticorruption: A Roadmap (Stockholm: Swedish Expert Group for Aid Studies, 2017), http://eba.se/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2017_10_final-webb.pdf .

7 An ampler discussion of this issue can be found in Robert Klitgaard, Addressing Corruption Together (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2015), https://www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/publications/FINAL%20Addressing%20corruption%20together.pdf .

8 For the intellectual genealogy of these terms, see Mungiu-Pippidi, A Quest for Good Governance , chap. 1 – 2; and Talcott Parsons, Introduction to Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 80–82.

9 Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York: Crown Business, 2012); Francis Fukuyama, Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014); and Douglass C. North, John J. Wallis, and Barry Weingast, Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

10 A fuller argument roughly compatible with mine appears in North, Wallis, and Weingast, Violence and Social Orders .

11 For evidence, see Mungiu-Pippidi, A Quest for Good Governance , chap. 2; and Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadasov, “When Do Anticorruption Laws Matter?”

12 For a more extensive argument, see Robert Rotberg, “Good Governance Means Performance and Results,” Governance 27 (3) (2014): 511 – 518; and Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, “For a New Generation of Objective Indicators in Governance and Corruption Studies,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (3) (2016): 363–367.

13 Rakesh Kochhar, A Global Middle Class Is More Promise than Reality (Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, 2015), http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/07/08/a-global-middle-class-is-more-promise-than-reality/ .

14 See Niklas Kossow and Roberto M. B. Kukutschka, “Civil Society and Online Connectivity: Controlling Corruption on the Net?” Crime, Law and Social Change 68 (4) (2017): 1–18.

15 Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock, “Solutions when the Solution is the Problem: Arraying the Disarray in Development,” World Development 32 (2) (2004): 191–212.

16 Robert Rotberg makes a similar point in “Good Governance Means Performance and Results.”

17 See Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadasov, “When Do Anticorruption Laws Matter?”

19 See updated evidence in Mihaly Fazekas, “Red Tape, Bribery and Government Favouritism: Evidence from Europe,” Crime, Law & Social Change 68 (4) (2017): 403–429.

20 For the full models, see Mungiu-Pippidi, A Quest for Good Governance , chap. 4; and Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Ramin Dadasov, “Measuring Control of Corruption by a New Index of Public Integrity,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (3) (2016): 415–438.

How to Stop Corruption Essay: Guide & Topics [+4 Samples]

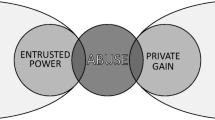

Corruption is an abuse of power that was entrusted to a person or group of people for personal gain. It can appear in various settings and affect different social classes, leading to unemployment and other economic issues. This is why writing an essay on corruption can become a challenge.

One “how to stop corruption” essay will require plenty of time and effort, as the topic is too broad. That’s why our experts have prepared this guide. It can help you with research and make the overall writing process easier. Besides, you will find free essays on corruption with outlines.

- ✍️ How to Write an Essay

- 💰 Essay Examples

- 🤑 How to Stop Corruption Essay

- 💲 Topics for Essay

✍️ How to Write an Essay on Corruption

Before writing on the issue, you have to understand a few things. First , corruption can take different forms, such as:

- Bribery – receiving money or other valuable items in exchange for using power or influence in an illegal way.

- Graft – using power or authority for personal goals.

- Extortion – threats or violence for the person’s advantage.

- Kickback – paying commission to a bribe-taker for some service.

- Cronyism – assigning unqualified friends or relatives to job positions.

- Embezzlement – stealing the government’s money.

Second , you should carefully think about the effects of corruption on the country. It seriously undermines democracy and the good name of political institutions. Its economic, political, and social impact is hard to estimate.

Let’s focus on writing about corruption. What are the features of your future paper? What elements should you include in your writing?

Below, we will show you the general essay on corruption sample and explain each part’s importance:

You already chose the paper topic. What’s next? Create an outline for your future writing. You’re better to compose a plan for your paper so that it won’t suffer from logic errors and discrepancies. Besides, you may be required to add your outline to your paper and compose a corruption essay with headings.

At this step, you sketch out the skeleton:

- what to write in the introduction;

- what points to discuss in the body section;

- what to put into the conclusion.

Take the notes during your research to use them later. They will help you to put your arguments in a logical order and show what points you can use in the essay.

For a long-form essay, we suggest you divide it into parts. Title each one and use headings to facilitate the reading process.

🔴 Introduction

The next step is to develop a corruption essay’s introduction. Here, you should give your readers a preview of what’s coming and state your position.

- Start with a catchy hook.

- Give a brief description of the problem context.

- Provide a thesis statement.

You can always update and change it when finishing the paper.

🔴 Body Paragraphs

In the body section, you will provide the central points and supporting evidence. When discussing the effects of this problem in your corruption essay, do not forget to include statistics and other significant data.

Every paragraph should include a topic sentence, explanation, and supporting evidence. To make them fit together, use analysis and critical thinking.

Use interesting facts and compelling arguments to earn your audience’s attention. It may drift while reading an essay about corruption, so don’t let it happen.

🔴 Quotations

Quotes are the essential elements of any paper. They support your claims and add credibility to your writing. Such items are exceptionally crucial for an essay on corruption as the issue can be controversial, so you may want to back up your arguments.

- You may incorporate direct quotes in your text. In this case, remember to use quotation marks and mark the page number for yourself. Don’t exceed the 30 words limit. Add the information about the source in the reference list.

- You may decide to use a whole paragraph from your source as supporting evidence. Then, quote indirectly—paraphrase, summarize, or synthesize the argument of interest. You still have to add relevant information to your reference list, though.

Check your professor’s guidelines regarding the preferred citation style.

🔴 Conclusion

In your corruption essay conclusion, you should restate the thesis and summarize your findings. You can also provide recommendations for future research on the topic. Keep it clear and short—it can be one paragraph long.

Don’t forget your references!

Include a list of all sources you used to write this paper. Read the citation guideline of your institution to do it correctly. By the way, some citation tools allow creating a reference list in pdf or Word formats.

💰 Corruption Essay Examples

If you strive to write a good how to stop a corruption essay, you should check a few relevant examples. They will show you the power of a proper outline and headings. Besides, you’ll see how to formulate your arguments and cite sources.

✔️ Essay on Corruption: 250 Words

If you were assigned a short paper of 250 words and have no idea where to start, you can check the example written by our academic experts. As you can see below, it is written in easy words. You can use simple English to explain to your readers the “black money” phenomenon.

Another point you should keep in mind when checking our short essay on corruption is that the structure remains the same. Despite the low word count, it has an introductory paragraph with a thesis statement, body section, and a conclusion.

Now, take a look at our corruption essay sample and inspire!

✔️ Essay on Corruption: 500 Words

Cause and effect essay is among the most common paper types for students. In case you’re composing this kind of paper, you should research the reasons for corruption. You can investigate factors that led to this phenomenon in a particular country.

Use the data from the official sources, for example, Transparency International . There is plenty of evidence for your thesis statement on corruption and points you will include in the body section. Also, you can use headlines to separate one cause from another. Doing so will help your readers to browse through the text easily.

Check our essay on corruption below to see how our experts utilize headlines.

🤑 How to Stop Corruption: Essay Prompts

Corruption is a complex issue that undermines the foundations of justice, fairness, and equality. If you want to address this problem, you can write a “How to Stop Corruption” essay using any of the following topic ideas.

The writing prompts below will provide valuable insights into this destructive phenomenon. Use them to analyze the root causes critically and propose effective solutions.

How to Prevent Corruption Essay Prompt

In this essay, you can discuss various strategies and measures to tackle corruption in society. Explore the impact of corruption on social, political, and economic systems and review possible solutions. Your paper can also highlight the importance of ethical leadership and transparent governance in curbing corruption.

Here are some more ideas to include:

- The role of education and public awareness in preventing corruption. In this essay, you can explain the importance of teaching ethical values and raising awareness about the adverse effects of corruption. It would be great to illustrate your essay with examples of successful anti-corruption campaigns and programs.

- How to implement strong anti-corruption laws and regulations. Your essay could discuss the steps governments should take in this regard, such as creating comprehensive legislation and independent anti-corruption agencies. Also, clarify how international cooperation can help combat corruption.

- Ways of promoting transparency in government and business operations. Do you agree that open data policies, whistleblower protection laws, independent oversight agencies, and transparent financial reporting are effective methods of ensuring transparency? What other strategies can you propose? Answer the questions in your essay.

How to Stop Corruption as a Student Essay Prompt

An essay on how to stop corruption as a student can focus on the role of young people in preventing corruption in their communities and society at large. Describe what students can do to raise awareness, promote ethical behavior, and advocate for transparency and accountability. The essay can also explore how instilling values of integrity and honesty among young people can help combat corruption.

Here’s what else you can talk about:

- How to encourage ethical behavior and integrity among students. Explain why it’s essential for teachers to be models of ethical behavior and create a culture of honesty and accountability in schools. Besides, discuss the role of parents and community members in reinforcing students’ moral values.

- Importance of participating in anti-corruption initiatives and campaigns from a young age. Your paper could study how participation in anti-corruption initiatives fosters young people’s sense of civic responsibility. Can youth engagement promote transparency and accountability?

- Ways of promoting accountability within educational institutions. What methods of fostering accountability are the most effective? Your essay might evaluate the efficacy of promoting direct communication, establishing a clear code of conduct, creating effective oversight mechanisms, holding all members of the educational process responsible for their actions, and other methods.

How to Stop Corruption in India Essay Prompt

In this essay, you can discuss the pervasive nature of corruption in various sectors of Indian society and its detrimental effects on the country’s development. Explore strategies and measures that can be implemented to address and prevent corruption, as well as the role of government, civil society, and citizens in combating this issue.

Your essay may also include the following:

- Analysis of the causes and consequences of corruption in India. You may discuss the bureaucratic red tape, weak enforcement mechanisms, and other causes. How do they affect the country’s development?

- Examination of the effectiveness of existing anti-corruption laws and measures. What are the existing anti-corruption laws and measures in India? Are they effective? What are their strengths and weaknesses?

- Discussion of potential solutions and reforms to curb corruption. Propose practical solutions and reforms that can potentially stop corruption. Also, explain the importance of political will and international cooperation to implement reforms effectively.

Government Corruption Essay Prompt

A government corruption essay can discuss the prevalence of corruption within government institutions and its impact on the state’s functioning. You can explore various forms of corruption, such as bribery, embezzlement, and nepotism. Additionally, discuss their effects on public services, economic development, and social justice.

Here are some more ideas you can cover in your essay:

- The causes and manifestations of government corruption. Analyze political patronage, weak accountability systems, and other factors that stimulate corruption. Additionally, include real-life examples that showcase the manifestations of government corruption in your essay.

- The impact of corruption on public trust and governance. Corruption undermines people’s trust and increases social inequalities. In your paper, we suggest evaluating its long-term impact on countries’ development and social cohesion.

- Strategies and reforms to combat government corruption. Here, you can present and examine the best strategies and reforms to fight corruption in government. Also, consider the role of international organizations and media in advocating for anti-corruption initiatives.

How to Stop Police Corruption Essay Prompt

In this essay, you can explore strategies and reforms to address corruption within law enforcement agencies. Start by investigating the root causes of police corruption and its impact on public safety and trust. Then, propose effective measures to combat it.

Here’s what else you can discuss in your essay:

- The factors contributing to police corruption, such as lack of accountability and oversight. Your paper could research various factors that cause police corruption. Is it possible to mitigate their effect?

- The consequences of police corruption for community relations and public safety. Police corruption has a disastrous effect on public safety and community trust. Your essay can use real-life examples to show how corruption practices in law enforcement undermine their legitimacy and fuel social unrest.

- Potential solutions, such as improved training, transparency, and accountability measures. Can these measures solve the police corruption issue? What other strategies can be implemented to combat the problem? Consider these questions in your essay.

💲 40 Best Topics for Corruption Essay

Another key to a successful essay on corruption is choosing an intriguing topic. There are plenty of ideas to use in your paper. And here are some topic suggestions for your writing:

- What is corruption? An essay should tell the readers about the essentials of this phenomenon. Elaborate on the factors that impact its growth or reduce.

- How to fight corruption ? Your essay can provide ideas on how to reduce the effects of this problem. If you write an argumentative paper, state your arguments, and give supporting evidence. For example, you can research the countries with the lowest corruption index and how they fight with it.

- I say “no” to corruption . This can be an excellent topic for your narrative essay. Describe a situation from your life when you’re faced with this type of wrongdoing.

- Corruption in our country. An essay can be dedicated, for example, to corruption in India or Pakistan. Learn more about its causes and how different countries fight with it.

- Graft and corruption. We already mentioned the definition of graft. Explore various examples of grafts, e.g., using the personal influence of politicians to pressure public service journalists. Provide your vision of the causes of corruption. The essay should include strong evidence.

- Corruption in society. Investigate how the tolerance to “black money” crimes impact economics in developing countries.

- How can we stop corruption ? In your essay, provide suggestions on how society can prevent this problem. What efficient ways can you propose?

- The reasons that lead to the corruption of the police. Assess how bribery impacts the crime rate. You can use a case of Al Capone as supporting evidence.

- Literature and corruption. Choose a literary masterpiece and analyze how the author addresses the theme of crime. You can check a sample paper on Pushkin’s “ The Queen of Spades ”

- How does power affect politicians ? In your essay on corruption and its causes, provide your observations on ideas about why people who hold power allow the grafts.

- Systemic corruption in China. China has one of the strictest laws on this issue. However, crime still exists. Research this topic and provide your observations on the reasons.

- The success of Asian Tigers . Explore how the four countries reduced corruption crime rates. What is the secret of their success? What can we learn from them?

- Lee Kuan Yew and his fight against corruption. Research how Singapore’s legislation influenced the elimination of this crime.

- Corruption in education. Examine the types in higher education institutions. Why does corruption occur?

- Gifts and bribes . You may choose to analyze the ethical side of gifts in business. Can it be a bribe? In what cases?

- Cronyism and nepotism in business. Examine these forms of corruption as a part of Chinese culture.

- Kickbacks and bribery. How do these two terms are related, and what are the ways to prevent them?

- Corporate fraud. Examine the bribery, payoffs, and kickbacks as a phenomenon in the business world. Point out the similarities and differences.

- Anti-bribery compliance in corporations. Explore how transnational companies fight with the misuse of funds by contractors from developing countries.

- The ethical side of payoffs. How can payoffs harm someone’s reputation? Provide your point of view of why this type of corporate fraud is unethical.

- The reasons for corruption of public officials.

- Role of auditors in the fight against fraud and corruption.

- The outcomes of corruption in public administration .

- How to eliminate corruption in the field of criminal justice.

- Is there a connection between corruption and drug abuse ?

- The harm corruption does to the economic development of countries.

- The role of anti-bribery laws in fighting financial crimes.

- Populist party brawl against corruption and graft.

- An example of incorrigible corruption in business: Enron scandal .

- The effective ways to prevent corruption.

- The catastrophic consequences of corruption in healthcare.

- How regular auditing can prevent embezzlement and financial manipulation.

- Correlation between poverty and corruption .

- Unethical behavior and corruption in football business.

- Corruption in oil business: British Petroleum case.

- Are corruption and bribery socially acceptable in Central Asian states?

- What measures should a company take to prevent bribery among its employees?

- Ways to eliminate and prevent cases of police corruption.

- Gift-giving traditions and corruption in the world’s culture.

- Breaking business obligations: embezzlement and fraud.

These invaluable tips will help you to get through any kind of essay. You are welcome to use these ideas and writing tips whenever you need to write this type of academic paper. Share the guide with those who may need it for their essay on corruption.

This might be interesting for you:

- Canadian Identity Essay: Essay Topics and Writing Guide

- Nationalism Essay: An Ultimate Guide and Topics

- Human Trafficking Essay for College: Topics and Examples

- Murder Essay: Top 3 Killing Ideas to Complete your Essay

🔗 References

- Public Corruption: FBI, U.S. Department of Justice

- Anti-Corruption and Transparency: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- United Nations Convention against Corruption: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- Corruption Essay: Cram

- How to Construct an Essay: Josh May

- Essay Writing: University College Birmingham

- Structuring the Essay: Research & Learning Online

- Insights from U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre: Medium

- Share to Facebook

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Do you have to write an essay for the first time? Or maybe you’ve only written essays with less than 1000 words? Someone might think that writing a 1000-word essay is a rather complicated and time-consuming assignment. Others have no idea how difficult thousand-word essays can be. Well, we have...

To write an engaging “If I Could Change the World” essay, you have to get a few crucial elements: Let us help you a bit and give recommendations for “If I Could Change the World” essays with examples. And bookmark our writing company website for excellent academic assistance and study...

![essay on eradication of corruption Why I Want to be a Pharmacist Essay: How to Write [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/cut-out-medicament-drug-doctor-medical-1-284x153.jpg)

Why do you want to be a pharmacist? An essay on this topic can be challenging, even when you know the answer. The most popular reasons to pursue this profession are the following:

How to write a film critique essay? To answer this question, you should clearly understand what a movie critique is. It can be easily confused with a movie review. Both paper types can become your school or college assignments. However, they are different. A movie review reveals a personal impression...

Are you getting ready to write your Language Proficiency Index Exam essay? Well, your mission is rather difficult, and you will have to work hard. One of the main secrets of successful LPI essays is perfect writing skills. So, if you practice writing, you have a chance to get the...

![essay on eradication of corruption Dengue Fever Essay: How to Write It Guide [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/scientist-hand-is-holding-test-plate-284x153.jpg)

Dengue fever is a quite dangerous febrile disease that can even cause death. Nowadays, this disease can be found in the tropics and Africa. Brazil, Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia, and India are also vulnerable to this disease.