The evolving profile of eating disorders and their treatment in a changing and globalised world

Affiliations.

- 1 Centre for Research in Eating and Weight Disorders, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King's College London, London SE5 8AF, UK; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Centre for Research in Eating and Weight Disorders, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King's College London, London SE5 8AF, UK.

- 3 Center for Eating and Feeding Disorders Research, Mental Health Center Ballerup, Copenhagen University Hospital-Mental Health Services CPH, Copenhagen, Denmark; Institute of Biological Psychiatry, Mental Health Center Sct. Hans, Mental Health Services Copenhagen, Roskilde, Denmark.

- 4 Psychiatry Department, St Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- 5 Centre for Research in Eating and Weight Disorders, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King's College London, London SE5 8AF, UK; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

- PMID: 38705161

- DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00874-2

- Publications

- Published Papers, 2021

Published Papers by year

Walter Kaye and the UCSD Eating Disorders Research team have published over 250 papers on the neurobiology of eating disorders. These publications include behavioral, treatment, and cognitive neuroscience studies that have improved understanding of the clinical presentation, genetics, neurotransmitter systems, and neural substrates involved in appetite dysregulation and disordered eating. These studies are guiding the development of more effective, neurobiologically informed interventions.

- Treatment of Patients With Anorexia Nervosa in the US – A Crisis in care

- Walter H. Kaye, MD; Cynthia M. Bulik, PhD

- Association of Brain Reward Response With Body Mass Index and Ventral Striatal-Hypothalamic Circuitry Among Young Women With Eating Disorders

- Guido K. W. Frank, MD; Megan E. Shott, BS; Joel Stoddard, MD; Skylar Swindle, BS; Tamara L. Pryor, PhD

- The acceptability, feasibility, and possible benefits of a neurobiologically-informed 5-day multifamily treatment for adults with anorexia nervosa.

- Wierenga CE, Hill L, Knatz Peck S, McCray J, Greathouse L, Peterson D, Scott A, Eisler I, Kaye WH.

- Int J Eat Disord. 2018 May 2. doi: 10.1002/eat.22876. [Epub ahead of print]

- PMID: 29722047

- Free PMC Article

- Research Program

- Current Research Studies

- Genetic Studies

- Participate in Our Studies

Multi-family Therapy for Eating Disorders Across the Lifespan

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Julian Baudinet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7840-4158 1 , 2 &

- Ivan Eisler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8211-7514 1 , 2

278 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

This review aims to report on recent evidence for multi-family therapy for eating disorders (MFT) across the lifespan. It is a narrative update of recent systematic, scoping and meta-analytic reviews.

Recent Findings

There has been a recent increase in published theoretical, quantitative and qualitative reports on MFT in the past few years. Recent and emerging data continues to confirm MFT can support eating disorder symptom improvement and weight gain, for those who may need to, for people across the lifespan. It has also been associated with improved comorbid psychiatric symptoms, self-esteem and quality of life. Data are also emerging regarding possible predictors, moderators and mediators of MFT outcomes, as well as qualitative data on perceived change processes. These data suggest families with fewer positive caregiving experiences at the start of treatment may particularly benefit from the MFT context. Additionally, early change in family functioning within MFT may lead to improved outcomes at end of treatment.

MFT is a useful adjunctive treatment across the lifespan for people with eating disorders. It helps to promote change in eating disorder and related difficulties. It has also been shown to support and promote broader family and caregiver functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward the Integration of Family Therapy and Family-Based Treatment for Eating Disorders

Life is different now – impacts of eating disorders on Carers in New Zealand: a qualitative study

A systematic review of the impact of carer interventions on outcomes for patients with eating disorders

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multi-family therapy (MFT) is increasingly being implemented in eating disorder services internationally [ 1 •]. MFT models differ significantly depending on the country and service context. What they all have in common is that they are (a) group-based, (b) involve several families working together as part of treatment with the support of a clinical team and, (c) in the context of eating disorders, are most commonly delivered in blocks of several hours or full days of treatment [ 2 , 3 ]. MFT has been described in the mental health literature since the 1960s. The earliest groups described were for people struggling with schizophrenia [ 4 , 5 ], substance misuse [ 6 ] and depression [ 7 , 8 ]. Nowadays, MFT is used internationally to support people with a range of presentations across the lifespan including eating disorders, mood disorders, schizophrenia, addiction and medical illnesses [ 9 ].

MFT for eating disorders was first described for young adults with bulimia nervosa [ 10 ] and anorexia nervosa [ 11 ] in the 1980s. Adolescent-specific MFT models emerged in the 1990s, initially from teams in Germany [ 12 , 13 ] and the UK [ 14 ]. These MFT models integrated the theoretical concepts of eating disorder focused family therapy [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] with more general concepts of MFT [ 14 , 19 , 20 ].

The overarching aim of current MFT models are to speed up the recovery process by offering brief, intensive support in the early stages of treatment when families are feeling most in need of urgent support. MFT differs from other intensive outpatient treatment options (e.g., day programmes, partial hospitalisation programmes, intensive outpatient treatment, etc.) by being entirely group-based and typically adjunctive to other therapeutic interventions [ 21 ]. By bringing multiple families together, MFT provides an opportunity for them to learn from each other and share experiences with a wider range of people, including others with lived experience [ 13 , 22 ]. This is described as helping to reduce stigma and a sense of isolation [ 23 , 24 ]. The MFT milieu has also been described as a “hot house” learning environment in which it is safe to try out new behaviours and express emotions with increased support [ 19 ]. The collaborative environment of MFT may also help to highlight and address any deleterious staff-patient dynamics that can otherwise hamper treatment engagement and progress [ 13 ].

Several systematic, scoping and meta-analytic reviews have been published on MFT across the lifespan in recent years [ 1 , 25 , 26 ]. MFT Manuals have been produced in English [ 27 , 28 , 29 •, 30 ], French [ 31 ], Swedish [ 32 , 33 ], and German [ 34 ].

Typically, MFT is offered in an outpatient context, although day- and inpatient models have also been described. The briefest MFT models provide three [ 35 ] or five [ 28 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] consecutive days of MFT offered as a stand-alone intervention. The latter five-day model has been manualised by a team at the University of California, San Diego, and named Temperament-Based Therapy with Support (TBT-S [ 28 ]). Other models, such as the Maudsley model, offer six to ten days of MFT spread across 6–12 months [ 29 •, 40 ]. Others offer up to 20 days or more of MFT [ 41 , 42 , 43 •] spread across a period of 12 months or more. Inpatient MFT models tend to be more heterogeneous. Those described in the literature range from the aforementioned three and five day models to eight-week [ 44 ], 26-week [ 45 ] and 12-month models [ 46 ].

The majority of programmes described in this paper are outpatient child and adolescent MFT models for anorexia nervosa (MFT-AN), although the number of adult studies is growing. Only recently have MFT models specifically for bulimia nervosa (MFT-BN) been developed [ 47 , 48 ]. Several services offer MFT for mixed eating disorder groups [ 36 , 46 , 49 •]. During child and adolescent MFT, parents and siblings are typically invited to attend, whereas adult models may also include partners, other significant people in the participant’s life, and/or parents/caregivers.

This review aims to narratively synthesise key MFT findings and provide an update on new quantitative and qualitative data published since our most recent systematic scoping review [ 1 ]. While the full systematic scoping review process was not repeated, the same search terms and strategy were implemented using the same databases (PsycInfo, Medline, Embase, CENTRAL) with the date range set for April 2021 to the present.

Outpatient Multi-family Therapy Outcomes

Regardless of age or MFT model, the pattern of findings is relatively similar across studies. One outpatient MFT-AN randomized controlled trial (RCT) has been published to date ( N = 169, age range 12–20 years) [ 50 •], although two other RCT protocols have been reported [ 51 , 52 ], suggesting more is to follow. Eisler et al. [ 50 •] randomised participants to 12 months of single-family therapy alone or single-family therapy with the addition of 10 days of adjunctive MFT-AN spread across treatment. Both groups reported significant improvements in weight, eating disorder psychopathology and mood, as well as parent-rated negative aspects of caregiving. Participants who received MFT-AN were significantly more likely to have a better global outcome, using the Morgan Russel outcome criteria [ 53 ], compared to those who received single-family therapy alone. At six-month follow-up (18 months post-randomisation) this difference was no longer significant, however, weight was significantly higher for those who received MFT-AN compared to single-family therapy [ 50 •].

Findings from uncontrolled comparison studies and case series’ confirm MFT is associated with weight gain for those who are underweight [ 43 •, 49 •, 50 •, 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 ] and a reduction in eating disorder symptoms [ 3 , 43 •, 49 •, 50 •, 56 , 57 ].

Meta-analytic review findings suggest a large effect size for weight ( n = 8 studies) and medium effect size for self-reported eating disorder symptoms ( n = 4 studies) from baseline to post-MFT intervention, although no differences were reported between MFT and comparison interventions [ 26 ]. When subgroup analyses of weight outcomes were assessed by age, adolescent MFT was associated with significant weight gain with a large effect (standard mean difference = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.94, 1.36), but adult MFT was not (standard mean difference = 0.18, 95% CI = − 0.09, 0.45). It is worth noting that only three adult studies [ 39 , 45 , 46 ] were included in this analysis, all of which had very different treatment lengths and intensity (range 5 days – 12 months). Two included participants with mixed eating disorder diagnoses [ 39 , 46 ] and one included restrictive eating disorder presentations only [ 45 ]. Only one MFT study across the lifespan in this review did not find a significant improvement in weight during MFT, however, participants ( N = 10) in this study reported significant improvements in eating disorder symptoms and mean BMI at the start of treatment was 20.7 (sd = 3.3, range = 16.0–26.1), which was maintained during treatment [ 45 ].

Regarding broader psycho-social functioning, there is evidence that MFT is associated with improved quality of life [ 56 , 58 ], self-perception and self-image [ 57 ], self-esteem [ 58 , 59 ], reduced caregiver burden [ 54 ], changes in expressed emotion [ 60 ], as well as improved general family functioning [ 39 , 43 •, 61 , 62 ] and communication [ 63 ]. Notably, change in family functioning and expressed emotion are more varied and not consistently reported between studies.

Within the last few years, data are also beginning to emerge regarding possible moderators, mediators and predictors (baseline individual and family factors) of MFT outcomes. Terache et al. [ 43 •] found that MFT was associated with improvements in all aspects of family functioning on the Family Assessment Device [ 64 ], and that two subscales (roles, communication) and the general family functioning score each mediated improvements in some aspects of eating disorder symptomatology measures using the Eating Disorder Inventory, second edition (EDI-II) [ 65 ]. Most notably, an improvement in the clarity of family roles mediated changes in drive for thinness [ 43 •]. However, in the same study, family functioning did not mediate improvements in weight [ 43 •]. In another study, decreases in parental perceived isolation was associated with improved young person physical health and general functioning at the end of treatment [ 54 ].

Regarding baseline predictors of outcome, Funderud et al. [ 49 •] reported that lower baseline weight was not significantly associated with change in eating disorder symptoms or distress. Dennhag et al. [ 54 ] found that baseline maternal level of guilt was associated with poorer end-of-treatment eating disorder symptom outcomes in their case series. Additionally, greater paternal social isolation and perceived burden of dysregulated behaviours was associated with poorer physical health outcomes for the young person at end of treatment [ 54 ].

In a secondary analysis of the Eisler et al. [ 50 •] RCT, six hypothesised moderators of treatment effect were recently explored; (1) age, (2) eating disorder symptom severity, (3) perceived conflict from the 3) young person and (4) parent/caregiver perspective, parent-rated (5) positive and (6) negative experiences of caregiving [ 66 ]. Positive experiences of caregiving significantly moderated treatment effect. Families presenting with fewer parent-rated positive caregiving experiences at baseline had higher weight at follow-up if they had MFT-AN alongside single-family therapy compared to single-family therapy alone. This is striking given consistent findings from three studies that positive caregiving experiences do not change during MFT [ 35 , 50 •, 61 ]. Taken together, these data suggest that MFT-AN may help protect against this impacting outcome for the adolescent, however, it does not seem help improve parental sense of caregiving itself. The findings from this moderator study extend previous findings that weight at commencement of treatment does not seem to impact on outcome [ 49 •] by demonstrating that it also does not seem to moderate treatment effect [ 66 ].

Outcome data for MFT-BN is still very limited, and all data are generated from one outpatient specialist child and adolescent eating disorder clinic, the Maudsley Centre for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders. Quantitative outcomes ( N = 50) from this 14-week programme consisting of weekly 90 min sessions indicate it is associated with a reduction in binge-purge behaviours, as well as improvements in eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, depression and emotion dysregulation [ 48 ]. Caregiver burden and parental mood also significantly improved in the same study, although level of anxiety in the young person did not [ 48 ]. While promising, more data are needed to confirm MFT-BN’s effectiveness and replicability in different contexts.

Multi-family Therapy Outcomes in Day- and Inpatient Settings

A much smaller amount of data have been reported on for inpatient/day-patient MFT models. Regarding quantitative data, three inpatient (two young person [ 61 , 67 ] and one adult [ 35 ] studies) and one adult day programme MFT study [ 44 ] have been published. All studies compared MFT to another type of treatment, namely, single family therapy [ 35 , 44 , 67 ] or a parent-only group intervention [ 61 ]. Two were small RCTs ( N = 25 [ 67 ], N = 48 [ 35 ]) and the other two used a non-randomised, uncontrolled comparison design.

Regarding outcomes, MFT within intensive treatment settings has been associated with weight gain and eating disorder symptom improvement [ 35 , 44 , 61 ], as well as broader factors such as expressed emotion [ 35 , 44 ], perceived caregiver burden [ 61 ], family member depressive symptoms [ 44 ], carer distress [ 35 ] and family functioning [ 61 ].

Notably, findings are more mixed than in the outpatient context. One study found no change in eating disorder symptoms and a worsening in perceived family functioning, which the authors attributed to increased family insight into their difficulties [ 67 ]. This may reflect the more heterogeneous treatment models tested and the fact that much more intervention is offered alongside MFT in inpatient and day-patient settings, such as other therapeutic group work, meal support, individual and family therapy sessions, etc.

Qualitative Findings and Perceived Change Processes During MFT

Due to the multiple co-occurring family needs and dynamics within MFT, increasingly qualitative studies are being produced to better understand participant, caregiver and clinician experiences of treatment. Based on data generated using observational, individual interviews and focus groups, MFT has been described as challenging and helpful, regardless of model, setting or age [ 1 ]. Specifically, people describe it as promoting understanding, identity development, mentalising and holistic recovery-oriented change [ 47 , 63 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 ]. Benefits include participants (particularly caregivers) feeling empowered, more confident and more able to share experiences [ 45 , 72 , 73 , 74 ]. Many also speak of the intensity and comparisons that arise out of the group process, and how this can generate and lead to the expression of strong emotion – described as both a challenge and a benefit [ 62 , 68 ]. Being able to learn and experiment through non-verbal and activity-based tasks has also been described as helpful and unique to MFT [ 68 ].

In the only study exploring the experience of MFT delivered online vs. face-to-face, data were mixed with participants describing both the convenience of online MFT as well as the potential loss of non-verbal communication during online working [ 62 ].

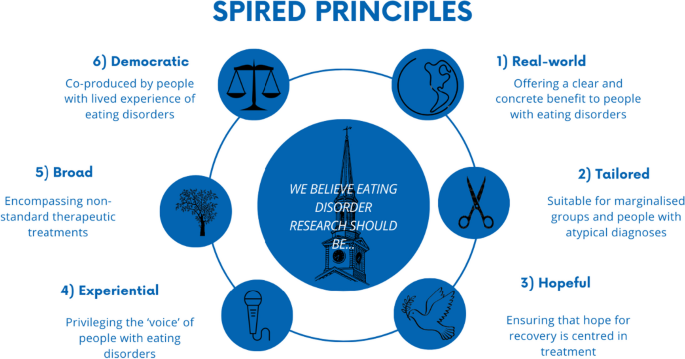

Most recently, qualitative studies have explored how participants and clinicians perceived change to occur within MFT [ 68 , 75 ]. Considering data from these three different perspectives suggests four inter-related elements (1. Intensity and immediacy, 2. Flexibility, 3. Peer connection and comparisons, 4. New ideas and channels of learning) may combine to contain the family system by building trust, engagement, hope and confidence. It seems that from this (re)established secure base, recovery-oriented behaviour change may (re)commence. See Fig. 1 for a proposed model of change in MFT-AN that incorporates data from clinician [ 75 ], young person and parent/caregiver [ 68 ] data. To date, no data have been collected regarding potential change processes in MFT-BN.

Proposed model of change in MFT-AN that incorporates young person, parent/caregiver and clinician perspectives from two recent qualitative studies [ 68 , 75 ]

Within this model (Fig. 1 ), the step of ‘containment’ may reflect the quantitative findings that improved family functioning mediates MFT outcomes [ 43 •]. Qualitative data suggests families need to move from a place of uncertainty and distress to connection to be able to take positive steps forward. This fits closely theoretically with the aspects of family functioning (roles, communication, general family functioning) that mediated outcomes in the Terache et al. [ 43 •] quantitative study. It also supports the idea that MFT (and possibly other intensive treatments) may (re)activate several change processes recently reported for single-family therapy [ 76 ].

These data also fit theoretically with qualitative data on young person and parent experiences of intensive day programme treatment [ 77 , 78 ]. While, day programme treatments are somewhat different from MFT, some do include multi-family elements. Other similarities include the intensity, increased level of support and additional hours of intervention per week. In both settings, the importance of immediacy, intensity and connecting with others are all described by young people and parents/caregivers as key factors in supporting people to (re)engage in less intensive outpatient treatment.

Conclusions

Available data are encouraging and suggest MFT is an effective adjunctive treatment for people with eating disorders across the lifespan. The available data are predominantly focused on adolescent MFT-AN models, specifically. Conclusions are more mixed regarding adult MFT models and MFT-BN. Findings for this review indicate that more is needed to confirm these effects in more diverse and larger groups, and settings. It will be important for future research to begin empirically investigating which components or aspects of MFT are most effective and whether this differs according to individual, family, cultural and service contexts.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

• Baudinet J, Eisler I, Dawson L, Simic M, Schmidt U. Multi-family therapy for eating disorders: a systematic scoping review of the quantitative and qualitative findings. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54:2095–120. This article is a recent comprehensive scoping review of quantitative and qualitative findings for MFT-ED across the lifespan.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cook-Darzens S, Gelin Z, Hendrick S. Evidence base for multiple family therapy (MFT) in non-psychiatric conditions and problems: a review (part 2): evidence base for non-psychiatric MFT. J Fam Ther. 2018;40:326–43.

Article Google Scholar

Gelin Z, Cook-Darzens S, Simon Y, Hendrick S. Two models of multiple family therapy in the treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21:19–30.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Laqueur HP, Laburt HA, Morong E. Multiple family therapy. Curr Psychiatr Ther. 1964;4:150–4.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

McFarlane WR. Multifamily groups in the treatment of severe Psychiatric disorders. New York & London: Guilford Press; 2002.

Google Scholar

Kaufman E, Kaufmann P. Multiple family therapy: a new direction in the treatment of drug abusers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abus. 1977;4:467–78.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anderson CM, Griffin S, Rossi A, Pagonis I, Holder DP, Treiber R. A comparative study of the Impact of Education vs. process groups for families of patients with affective disorders. Fam Process. 1986;25:185–205.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lemmens GMD, Eisler I, Buysse A, Heene E, Demyttenaere K. The effects on mood of adjunctive single-family and multi-family group therapy in the treatment of hospitalized patients with major depression a 15-month follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:98–105.

Van Es CM, El Khoury B, Van Dis EAM, Te Brake H, Van Ee E, Boelen PA, et al. The effect of multiple family therapy on mental health problems and family functioning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Process. 2023;62:499–514.

Wooley OW, Wooley SC, Deddens JA. Outcome evaluation of an intensive residential treatment program for bulimia. J Psychother Pract Res. 1993;2(3):242–56. PMID: 22700149; PMCID: PMC3330336.

Slagerman M, Yager J. Multiple family group treatment for eating disorders: a short term program. Psychiatr Med. 1989;7:269–83.

Asen E. Multiple family therapy: an overview. J Family Therapy. 2002;24:3–16.

Scholz M, Asen E. Multiple family therapy with eating disordered adolescents: concepts and preliminary results. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2001;9:33–42.

Dare C, Eisler I. A multi-family group day treatment programme for adolescent eating disorder. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2000;8:4–18.

Baudinet J, Simic M, Eisler I. From treatment models to manuals: Maudsley single- and multi-family therapy for adolescent eating disorders. In: Mariotti M, Saba G, Stratton P, editors. Systemic approaches to manuals. Switzerland: Springer, Cham; 2021. p. 349–72.

Dare C, Eisler I, Russell GFM, Szmukler GI. The clinical and theoretical impact of a controlled trial of family therapy in anorexia nervosa. J Marital Fam Ther. 1990;16:39–57.

Eisler I. The empirical and theoretical base of family therapy and multiple family day therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Family Therapy. 2005;27:104–31.

Eisler I, Simic M, Blessitt E, Dodge L, MCCAED Team. Maudsley Service Manual for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders. 2016. https://mccaed.slam.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Maudsley-Service-Manual-for-Child-and-Adolescent-Eating-Disorders-July-2016.pdf .

Asen E, Scholz M. Multi-family therapy: concepts and techniques. London/New York: Routledge; 2010.

Book Google Scholar

Simic M, Eisler I. Family and multifamily therapy. In: Eating and its Disorders. 2012. p. 260–79.

Chapter Google Scholar

Baudinet J, Simic M. Adolescent eating Disorder Day Programme Treatment models and outcomes: a systematic scoping review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:539.

Blessitt E, Baudinet J, Simic M, Eisler I. Eating disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults. The handbook of systemic family therapy. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2020. pp. 397–427.

Dawson L, Baudinet J, Tay E, Wallis A. Creating community - the introduction of multi-family therapy for eating disorders in Australia. Australian New Z J Family Therapy. 2018;39:283–93.

Simic M, Eisler I. Multi-family therapy. In: Loeb KL, Le Grange D, Lock J, editors. Family Therapy for Adolescent Eating and Weight disorders. New York: Imprint Routledge; 2015. pp. 110–38.

Gelin Z, Cook-Darzens S, Hendrick S. The evidence base for multiple family therapy in psychiatric disorders: a review (part 1). J Family Therapy. 2018;40:302–25.

Zinser J, O’Donnell N, Hale L, Jones CJ. Multi-family therapy for eating disorders across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Euro Eat Disorders Rev 2022;30(6):723–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2919

Balmbra S, Valvik M, Lyngmo S. Coming together, letting go. Bodo, Norway, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.nordlandssykehuset.no/siteassets/documents/Ressp/Coming-together-2019-10d-B5.pdf .

Hill LL, Knatz Peck S, Wierenga CE. Temperament based therapy with support for Anorexia Nervosa: a Novel treatment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009032063 .

• Simic M, Baudinet J, Blessitt E, Wallis A, Eisler I. Multi-family therapy for anorexia nervosa: a treatment manual. 1st edition. London, UK: Routledge; 2021. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003038764 . This is a treatment manual covering theory and practice of MFT-AN for young people. This is the model used in the only outpatient MFT-ED RCT.

Tantillo M, McGraw JS, Le Grange D. Multifamily therapy group for young adults with anorexia nervosa: reconnecting for recovery. 1st ed. London, UK: Routledge; 2020.

Duclos J, Carrot B, Minier L, Cook-Darzens S, Barton-Clegg V, Godart N, Criquillion-Doublet S. Manuel de Thérapie Multi-Familiale. 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350906742_Manuel_de_Therapie_Multi-Familiale_approche_integrative_pour_la_prise_en_charge_d%27adolescents_souffrant_d%27Anorexie_Mentale_et_de_leurs_familles .

Wallin U. Multi-family therapy with anorexia nervosa. A treatment manual. Lund: Lund University; 2007.

Wallin U. Multifamiljeterapi vid anorexia nervosa [Multifamily therapy of anorexia nervosa]. Lund, Sweden: Behandlingsmanual; 2011.

Scholz M, Rix M, Hegewald K. Tagesklinische multifamilientherapie bei anorexia nervosa – manual Des Dresdner modells [Outpatient multifamiliy therapy for anorexia nevrosa – manual of the Dresdner model]. In: Steinbrenner B, Schönauer CS, editors. Essst ̈ orungen – anorexie – bulemie-adipositas – therapie in theorie und praxis [Eating disorders. Anorexia – bulimia-obesity – therapy in theory and practice]. Vienna: Maudrich; 2003. pp. 66–75.

Whitney J, Murphy T, Landau S, Gavan K, Todd G, Whitaker W, et al. A practical comparison of two types of family intervention: an exploratory RCT of Family Day Workshops and Individual Family Work as a supplement to Inpatient Care for adults with Anorexia Nervosa. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2012;20:142–50.

Knatz Peck S, Towne T, Wierenga CE, Hill L, Eisler I, Brown T, et al. Temperament-based treatment for young adults with eating disorders: acceptability and initial efficacy of an intensive, multi-family, parent-involved treatment. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:110.

Marzola E, Knatz S, Murray SB, Rockwell R, Boutelle K, Eisler I, et al. Short-term intensive family therapy for adolescent eating disorders: 30-month outcome. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23:210–8.

Stedal K, Funderud I, Wierenga CE, Knatz-Peck S, Hill L. Acceptability, feasibility and short-term outcomes of temperament based therapy with support (TBT-S): a novel 5-day treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:156.

Wierenga CE, Hill L, Knatz Peck S, McCray J, Greathouse L, Peterson D, et al. The acceptability, feasibility, and possible benefits of a neurobiologically-informed 5-day multifamily treatment for adults with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51:863–9.

Baudinet J, Eisler I, Simic M. Thérapie multifamiliale intensive pour adolescents avec troubles des conduits alimentaires (TMF-AM) [Intensive multi-family therapy for adolescents with eating disorders]. In: Cook-Darzens S, Criquillion-Doublet S, editors. Les Thérapies multifamiliales appliquées aux troubles des conduites alimentaires [Multi-family therapies: applications to eating disorders]. Elsevier Masson: France,; 2023. pp. 13–35.

Minier L, Carrot B, Cook-Darzens S, Criquillion‐Doublet S, Boyer F, Barton‐Clegg V, Simic M, Voulgari S, Godart N, Duclos J, the THERAFAMBEST group. Conceptualising, designing and drafting a monthly multi‐family therapy programme and manual for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Fam Ther 2022;1467–6427.12403. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12403 .

Scholz M, Rix M, Scholz K, Gantchev K, Thomke V. Multiple family therapy for anorexia nervosa: concepts, experiences and results. J Family Therapy. 2005;27:132–41.

• Terache J, Wollast R, Simon Y, Marot M, Van der Linden N, Franzen A, et al. Promising effect of multi-family therapy on BMI, eating disorders and perceived family functioning in adolescent anorexia nervosa: an uncontrolled longitudinal study. Eat Disord. 2023;31:64–84. This recent naturalistic study includes a relatively large sample and includes mediator analyses.

Dimitropoulos G, Farquhar JC, Freeman VE, Colton PA, Olmsted MP. Pilot study comparing multi-family therapy to single family therapy for adults with anorexia nervosa in an intensive eating disorder program. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23:294–303.

Tantillo M, McGraw JS, Lavigne HM, Brasch J, Le Grange D. A pilot study of multifamily therapy group for young adults with anorexia nervosa: reconnecting for recovery. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:950–5.

Skarbø T, Balmbra SM. Establishment of a multifamily therapy (MFT) service for young adults with a severe eating disorder – experience from 11 MFT groups, and from designing and implementing the model. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:9.

Escoffié A, Pretorius N, Baudinet J. Multi-family therapy for bulimia nervosa: a qualitative pilot study of adolescent and family members’ experiences. J Eat Disord. 2022;10:91.

Stewart CS, Baudinet J, Hall R, Fiskå M, Pretorius N, Voulgari S, et al. Multi-family therapy for bulimia nervosa in adolescence: a pilot study in a community eating disorder service. Eat Disord. 2021;29:351–67.

• Funderud I, Halvorsen I, Kvakland A-L, Nilsen J-V, Skjonhaug J, Stedal K, et al. Multifamily therapy for adolescent eating disorders: a study of the change in eating disorder symptoms from start of treatment to follow-up. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:92. This larger naturalistic study conducted in Norway includes investigation of whether some baseline factors predict treatment response.

• Eisler I, Simic M, Hodsoll J, Asen E, Berelowitz M, Connan F, et al. A pragmatic randomised multi-centre trial of multifamily and single family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry . 2016;16:422. This is the only outpatient RCT for MFT-ED with a relatively large sample size compared to may MFT-ED studies.

Baudinet J, Eisler I, Simic M, Schmidt U. Brief early adolescent multi-family therapy (BEAM) trial for anorexia nervosa: a feasibility randomized controlled trial protocol. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:71.

Carrot B, Duclos J, Barry C, Radon L, Maria A-S, Kaganski I, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled trial on the comparison of multi-family therapy (MFT) and systemic single-family therapy (SFT) in young patients with anorexia nervosa: study protocol of the THERAFAMBEST study. Trials. 2019;20:249.

Russell GFM, Szmukler GI, Dare C, Eisler I. An evaluation of Family Therapy in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:1047.

Dennhag I, Henje E, Nilsson K. Parental caregiver burden and recovery of adolescent anorexia nervosa after multi-family therapy. Eat Disorders: J Treat Prev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2019.1678980 .

Gabel K, Pinhas L, Eisler I, Katzman D, Heinmaa M. The effect of multiple family therapy on Weight Gain in adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa: Pilot Data. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:4.

Gelin Z, Fuso S, Hendrick S, Cook-Darzens S, Simon Y. The effects of a multiple family therapy on adolescents with eating disorders: an outcome study. Fam Process. 2015;54:160–72.

Hollesen A, Clausen L, Rokkedal K. Multiple family therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study of eating disorder symptoms and interpersonal functioning: outcome of multiple family therapy. J Fam Ther. 2013;35:53–67.

Mehl A, Tomanova J, Kubena A, Papezova H. Adapting multi-family therapy to families who care for a loved one with an eating disorder in the Czech Republic combined with a follow-up pilot study of efficacy. J Fam Ther. 2013;35:82–101.

Salaminiou E, Campbell M, Simic M, Kuipers E, Eisler I. Intensive multi-family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: an open study of 30 families: multi-family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Family Therapy. 2017;39:498–513.

Uehara T, Kawashima Y, Goto M, Tasaki S, Someya T. Psychoeducation for the families of patients with eating disorders and changes in expressed emotion: a preliminary study. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:132–8.

Depestele L, Claes L, Dierckx E, Colman R, Schoevaerts K, Lemmens GMD. An adjunctive multi-family group intervention with or without patient participation during an inpatient treatment for adolescents with an eating disorder: a pilot study. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2017;25:570–8.

Yim SH, White S. Service evaluation of multi-family therapy for anorexia groups between 2013–2021 in a specialist child and adolescent eating disorders service. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045231193249 .

Voriadaki T, Simic M, Espie J, Eisler I. Intensive multi-family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: adolescents’ and parents’ day-to-day experiences. J Fam Ther. 2015;37:5–23.

Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMasters Family Assessment device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171–80.

Garner DM. Eating disorder inventory-2: professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa. 1991.

Baudinet J, Eisler I, Konstantellou A, Hunt T, Kassamali F, McLaughlin N, Simic M, Schmidt U. Perceived change mechanisms in multi-family therapy for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative follow-up study of adolescent and parent experiences. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2023;31(6):822–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.3006 .

Geist R, Heinmaa M, Stephens D, Davis R, Katzman DK. Comparison of family therapy and family group psychoeducation in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45:173–8.

Baudinet J, Eisler I, Konstantellou A, Hunt T, Kassamali F, McLaughlin N, et al. Perceived change mechanisms in multi-family therapy for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative follow-up study of adolescent and parent experiences. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2023;31:822–36.

Baumas V, Zebdi R, Julien-Sweerts S, Carrot B, Godart N, Minier L, et al. Patients and parents’ experience of multi-family therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: a pilot study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:584565.

Coopey E, Johnson G. Exploring the experience of young people receiving treatment for an eating disorder: family therapy for anorexia nervosa and multi-family therapy in an inpatient setting. J Eat Disord. 2022;10:101.

Escoffié A, Pretorius N, Baudinet J. Multi-family therapy for bulimia nervosa: a qualitative pilot study of adolescent and family members’ experiences. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00606-w .

Brinchmann BS, Krvavac S. Breaking down the wall’ patients’ and families’ experience of multifamily therapy for young adult women with severe eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:56.

Whitney J, Currin L, Murray J, Treasure J. Family Work in Anorexia Nervosa: a qualitative study of Carers’ experiences of two methods of family intervention. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2012;20:132–41.

Wiseman H, Ensoll S, Russouw L, Butler C. Multi-family therapy for Young People with Anorexia Nervosa: clinicians’ and Carers’ perspectives on systemic changes. J Systemic Ther. 2019;38:67–83.

Baudinet J, Eisler I, Roddy M, Turner J, Simic M, Schmidt U. Clinician perspectives on the change mechanisms in multi-family therapy for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. J Eat Disord. under review.

Baudinet J, Eisler I, Konstantellou A, Simic M, Schmidt U. How young people perceive change to occur in family therapy for anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. J Eat Disord. 2024;12:11.

Colla A, Baudinet J, Cavenagh P, Senra H, Goddard E. Change processes during intensive day programme treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa: a dyadic interview analysis of adolescent and parent views. Front Psychol. 2023;14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1226605 .

Gledhill LJ, MacInnes D, Chan SC, Drewery C, Watson C, Baudinet J. What is day hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa really like? A reflexive thematic analysis of feedback from young people. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:223.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Maudsley Centre for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders (MCCAED), Maudsley Hospital, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, SE5 8AZ, UK

Julian Baudinet & Ivan Eisler

Centre for Research in Eating and Weight Disorders (CREW), Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN), King’s College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, SE5 8AF, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JB and IE were involved in study design. JB drafted the initial manuscript. JB and IE reviewed the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julian Baudinet .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Both authors receive royalties from Routledge for a published manual on multi-family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa [ 29 •].

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Baudinet, J., Eisler, I. Multi-family Therapy for Eating Disorders Across the Lifespan. Curr Psychiatry Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-024-01504-5

Download citation

Accepted : 14 April 2024

Published : 06 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-024-01504-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Maudsley family therapy

- Multi-family therapy

- Family based treatment

- Anorexia nervosa

- Bulimia nervosa

- Group therapy

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2023

Eating disorder outcomes: findings from a rapid review of over a decade of research

- Jane Miskovic-Wheatley 1 , 2 ,

- Emma Bryant 1 , 2 ,

- Shu Hwa Ong 1 , 2 ,

- Sabina Vatter 1 , 2 ,

- Anvi Le 3 ,

- National Eating Disorder Research Consortium ,

- Stephen Touyz 1 , 2 &

- Sarah Maguire 1 , 2

Journal of Eating Disorders volume 11 , Article number: 85 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

14 Citations

277 Altmetric

Metrics details

Eating disorders (ED), especially Anorexia Nervosa (AN), are internationally reported to have amongst the highest mortality and suicide rates in mental health. With limited evidence for current pharmacological and/or psychological treatments, there is a grave responsibility within health research to better understand outcomes for people with a lived experience of ED, factors and interventions that may reduce the detrimental impact of illness and to optimise recovery. This paper aims to synthesise the literature on outcomes for people with ED, including rates of remission, recovery and relapse, diagnostic crossover, and mortality.

This paper forms part of a Rapid Review series scoping the evidence for the field of ED, conducted to inform the Australian National Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy 2021–2031, funded and released by the Australian Government. ScienceDirect, PubMed and Ovid/MEDLINE were searched for studies published between 2009 and 2022 in English. High-level evidence such as meta-analyses, large population studies and Randomised Controlled Trials were prioritised through purposive sampling. Data from selected studies relating to outcomes for people with ED were synthesised and are disseminated in the current review.

Of the over 1320 studies included in the Rapid Review, the proportion of articles focused on outcomes in ED was relatively small, under 9%. Most evidence was focused on the diagnostic categories of AN, Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder, with limited outcome studies in other ED diagnostic groups. Factors such as age at presentation, gender, quality of life, the presence of co-occurring psychiatric and/or medical conditions, engagement in treatment and access to relapse prevention programs were associated with outcomes across diagnoses, including mortality rates.

Results are difficult to interpret due to inconsistent study definitions of remission, recovery and relapse, lack of longer-term follow-up and the potential for diagnostic crossover. Overall, there is evidence of low rates of remission and high risk of mortality, despite evidence-based treatments, especially for AN. It is strongly recommended that research in long-term outcomes, and the factors that influence better outcomes, using more consistent variables and methodologies, is prioritised for people with ED.

Plain English summary

Eating disorders are complex psychiatric conditions that can seriously impact a person’s physical health. Whilst they are consistently associated with high mortality rates and significant psychosocial difficulties, lack of agreement on definitions of recovery, remission and relapse, as well as variations in methodology used to assess for standardised mortality and disability burden, means clear outcomes can be difficult to report. The current review is part of a larger Rapid Review series conducted to inform the development of Australia’s National Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy 2021–2031. A Rapid Review is designed to comprehensively summarise a body of literature in a short timeframe to guide policymaking and address urgent health concerns. This Rapid Review synthesises the current evidence-base for outcomes for people with eating disorders and identifies gaps in research and treatment to guide decision making and future clinical research. A critical overview of the scientific literature relating to outcomes in Western healthcare systems that may inform health policy and research in an Australian context is provided in this paper. This includes remission, recovery and relapse rates, diagnostic cross-over, the impact of relapse prevention programs, factors associated with outcomes, and findings related to mortality.

Introduction

Eating disorders (ED), especially Anorexia Nervosa (AN), have amongst the highest mortality and suicide rates in mental health. While there has been significant research into causal and maintaining factors, early identification efforts and evidence-based treatment approaches, global incidence rates have increased from 3.4% calculated between 2000 and 2006 to 7.8% between 2013 and 2018 [ 1 ]. While historically seen as a female illness, poorer outcomes are increasingly seen in other genders, including males [ 2 ].

Over 3.3 million healthy life years are lost worldwide due to ED each year, and many more lost to disability due to medical and psychiatric complications [ 3 ]. Suicide accounts for approximately 20% of non-natural deaths among people with ED [ 4 ]. As this loss of healthy life is preventable, there is a grave responsibility to better understand outcomes for people with ED, including factors which may minimise the detrimental impact they have on individuals, carers, and communities, as well as to optimise recovery.

There has been considerable debate within the clinical, scientific and lived experience (i.e., patient, consumer, carer) communities about the definition and measurement of key outcomes in ED, including ‘remission’ from illness (a period of relief from symptoms), ‘relapse’ (a resumption of symptoms) and ‘recovery’ (cessation of illness) [ 5 , 6 ], which can compromise outcome comparisons. Disparities include outcome variables relating to eating behaviours as well as medical, psychological, social and quality of life factors. There is increasing awareness in the literature of the elevated likelihood of diagnostic crossover [ 7 ]; research examining specific diagnostic profiles potentially misses outcomes where symptom experience transforms rather than alleviates. Methodological approaches in outcomes research are varied, the most significant being length of time to follow up, compromising direct study comparisons.

The aim of this Rapid Review (RR) is to synthesise the literature on outcomes for people with ED, including rates of remission, recovery and relapse, diagnostic crossover, and mortality. Factors influencing outcomes were summarised including demographic, illness, treatment, co-morbidities, co-occurring health conditions, societal factors, and impact of relapse prevention programs. This RR forms one of a series of reviews scoping the field of ED commissioned to inform the Australian National Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy 2021–2031 [ 8 ]. The objective is to evaluate the current literature in ED outcomes to identify areas of consensus, knowledge gaps and suggestions for future research.

The Australian Government Commonwealth Department of Health funded the InsideOut Institute for Eating Disorders (IOI) to develop the Australian Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy 2021–2031 [ 8 ] under the Psych Services for Hard to Reach Groups initiative (ID 4-8MSSLE). The strategy was developed in partnership with state and national stakeholders including clinicians, service providers, researchers, and experts by lived experience (including consumers and families/carers). Developed through a 2 year national consultation and collaboration process, the strategy provides the roadmap to establishing ED as a national research priority and is the first disorder-specific strategy to be developed in consultation with the National Mental Health Commission. To inform the strategy, IOI commissioned Healthcare Management Advisors (HMA) to conduct a series of RRs to broadly assess all available peer-reviewed literature on the six DSM-V [ 9 ] listed ED. RR’s were conducted in the following domains: (1) population, prevalence, disease burden, Quality of Life in Western developed countries; (2) risk factors; (3) co-occurring conditions and medical complications; (4) screening and diagnosis; (5) prevention and early intervention; (6) psychotherapies and relapse prevention; (7) models of care; (8) pharmacotherapies, alternative and adjunctive therapies; and (9) outcomes (including mortality) (current RR), with every identified paper allocated to only one of the above domains from abstract analysis by two investigators. Each RR was submitted for independent peer review to the Journal of Eating Disorders special edition, “Improving the future by understanding the present: evidence reviews for the field of eating disorders”.

A RR Protocol [ 10 ] was utilised to swiftly synthesise evidence to guide public policy and decision-making [ 11 ]. This approach has been adopted by several leading health organisations, including the World Health Organization [ 12 ] and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Rapid Response Service [ 13 ], to build a strong evidence base in a timely and accelerated manner, without compromising quality. RR was chosen as the most suitable design as it is conducted with broader search terms and inclusion criteria allowing to gain a better understanding of a specific field, returning a larger number of search results and providing a snapshot of key findings detailing the current state of a field at study [ 10 ]. A RR is not designed to be as comprehensive as a systematic review—it is purposive rather than exhaustive and provides actionable evidence to guide health policy [ 14 ].

The RR is a narrative synthesis adhering to the PRISMA guidelines [ 15 ]. It is divided by topic area and presented as a series of papers. Three research databases were searched: ScienceDirect, PubMed and Ovid/MEDLINE. To establish a broad understanding of the progress made in the field of eating disorders, and to capture the largest evidence base on the past 13 years (originally 2009–2019, but expanded to include the preceding two years), the eligibility criteria for included studies into the RR were kept broad. Therefore, included studies were published between 2009 and 2022, in English, and conducted within Western healthcare systems or health systems comparable to Australia in terms of structure and resourcing. The initial search and review process was conducted by three reviewers between 5 December 2019 and 16 January 2020. The re-run for the years 2020–2021 was conducted by two reviewers at the end of May 2021 and a final run for 2022 conducted in January 2023 to ensure the most up to date publications were included prior to publication.

The RR had a translational research focus with the objective of identifying evidence relevant to developing optimal care pathways. Searches, therefore, used a Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) approach to identify literature relating to population impact, prevention and early intervention, treatment, and long-term outcomes. Purposive sampling focused on high-level evidence studies such as: meta-analyses; systematic reviews; moderately sized randomised controlled trials (RCTs) ( n > 50); moderately sized controlled-cohort studies ( n > 50), or population studies ( n > 500). However, the diagnoses Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS), Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED) and Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder (UFED) necessitated a less stringent eligibility criterion due to a paucity of published articles. As these diagnoses are newly captured in the DSM-V [ 9 ] (released in 2013, within the allocated search timeframe), the evidence base is emerging, and fewer studies have been conducted. Thus, smaller studies ( n ≤ 20) and narrative reviews were also considered and included. Grey literature, such as clinical or practice guidelines, protocol papers (without results) and Masters’ theses or dissertations, was excluded.

Full methodological details including eligibility criteria, search strategy and terms and data analysis are published in a separate protocol paper [ 10 ]. The full RR included a total of over 1320 studies (see Additional file 1 : Fig. S1). Data from included studies relating to outcomes for eating disorders were synthesised and are presented in the current review.

Of the 1320 articles included in the RR, the proportion of articles focused on outcomes in ED was relatively small, just less than 9% ( n = 116) (see Additional file 2 : Table S1). Studies typically examined outcomes in AN, Bulimia Nervosa (BN) and Binge Eating Disorder (BED), with limited research in other diagnostic groups. Whereas most outcome studies reported recovery, remission and relapse rates, others explored factors impacting outcomes, such as quality of life, co-occurring conditions, and outcomes from relapse prevention programs.

ED, particularly AN, have long been associated with an increased risk of mortality. The current review summarises best available evidence exploring this association. Several factors complicate these findings including a lack of consensus on definitions of remission, recovery and relapse, widely varying treatment protocols and research methodologies, and limited transdiagnostic outcome studies or syntheses such as meta-analyses. Table 1 provides a summary of outcomes reported by studies identified in this review. There is considerable heterogeneity in the reported measures.

Overall outcomes

A good outcome for a person experiencing ED symptomatology is commonly defined as either remission or no longer meeting diagnostic criteria, as well as improved levels of psychosocial functioning and quality of life [ 28 , 29 ]. However, such a comprehensive approach is rarely considered, and there is no consensus on a definition for recovery, remission, or relapse for any of the ED diagnoses [ 30 , 31 ]. To contextualise this variation, definitions and determinants for these terms are presented in Table 2 .

The terms ‘remission’ and ‘recovery’ appear to be used interchangeably in the literature. Whilst ‘remission’ is usually defined by an absence of diagnostic symptomatology, and ‘recovery’ an improvement in overall functioning, the period in which an individual must be symptom-free to be considered ‘remitted’ or ‘recovered’ varies greatly between studies, follow-up (FU) time periods are inconsistent, and very few studies examine return to psychosocial function and quality of life (QoL) after alleviation of symptoms. The current review uses the terms adopted by the original studies. ‘Relapse’ is typically defined by a return of symptoms after a period of symptom relief. The reviewed studies report a variety of symptom determinants including scores on standardised psychological and behavioural interviews or questionnaires, weight criteria [including Body Mass Index (BMI) or %Expected Body Weight (%EBW)], clinical assessment by a multidisciplinary team, self-reported ED behaviours, meeting diagnostic criteria, or a combination of the above.

Remission, recovery, and relapse

In a global overview of all studies reviewed, remission or recovery rates were reported for around half of the cohort, regardless of diagnostic group. For example, a 30 month FU study of a transdiagnostic cohort of patients found 42% obtained full and 72% partial remission, with no difference between diagnostic groups for younger people; however, bulimic symptoms emerged frequently during FU, regardless of initial diagnosis [ 44 ]. A 6 year study following the course of a large clinical sample ( n = 793) reported overall recovery rates of 52% for AN, 50–52% for BN, 57% for EDNOS-Anorectic type (EDNOS-A), 60–64% for BED and 64–80% for EDNOS-Bulimic type (EDNOS-B) [ 7 ]. Of those who recorded full remission at end of treatment (EOT), relapse was highest for AN (26%), followed by BN (18%), and EDNOS-B (16%). Relapse was less common for individuals with BED (11–12%), and EDNOS-A (4%). Change in diagnosis (e.g., from AN to BN) was also seen within the relapse group [ 7 ].

Longer-term FU studies may more accurately reflect the high rates of relapse and diagnostic crossover associated with ED. A 17 year outcome study of ED in adult patients found only 29% remained fully recovered, with 21% partially recovered and half (50%) remaining ill [ 52 ], noting the protracted nature of illness for adults with longstanding ED. Relapse is observed at high rates (over 30%) among people with AN and BN at 22 year FU [ 61 ]. In a large clinical study using predictive statistical modelling, full remission was more likely for people with BED (47.4%) and AN (43.9%) compared to BN (25.2%) and OSFED (23.2%) [ 41 ]. This result is distinct from other studies citing AN to have the worst clinical outcomes within the diagnostic profiles [ 52 ]. The cut‐off points for the duration of illness associated with decreased likelihood of remission were 6–8 years for OSFED, 12–14 years for AN/BN and 20–21 years for BED [ 41 ]. As with recovery rates, reported rates of relapse are highly variable due to differing definitions and study methodologies used by researchers in FU studies [ 35 , 61 ].

Evidence from a meta-analysis of 16 studies found four factor clusters that significantly contributed to relapse; however, also noted a substantial variability in procedures and measures compromising study comparison [ 62 ]. Factors contributing to heightened risk of relapse included severity of ED symptoms at pre- and post-treatment, presence and persistence of co-occurring conditions, higher age at onset and presentation to assessment, and longer duration of illness. Process treatment variables contributing to higher risk included longer duration of treatment, previous engagement in psychiatric and medical treatment (including specialist ED treatment) and having received inpatient treatment. These variables may indicate more significant illness factors necessitating a higher intensity of treatment.

Importantly, full recovery is possible, with research showing fully recovered people may be indistinguishable from healthy controls (HCs) on all physical, behavioural, and psychological domains (as evaluated by a battery of standardised assessment measures), except for anxiety (those who have fully recovered may have higher general anxiety levels than HCs) [ 29 ].

Diagnostic crossover

Most studies reported outcomes associated with specific ED diagnoses; however, given a significant proportion of individuals will move between ED diagnoses over time, it can be challenging to determine diagnosis-specific outcomes. Results from a 6 year FU study indicated that overall individuals with ED crossed over to other ED diagnoses during the FU observational period, most commonly AN to BN (23–27%), then BN to BED (8–11%), BN to AN (8–9%) and BED to BN (7–8%) [ 7 ]. Even higher crossover trends were observed in the subgroup reporting relapse during the FU period, with 61.5% of individuals originally diagnosed with AN developing BN, 27.2% and 18.1% of individuals originally diagnosed with BN developing AN and BED respectively, and 18.7% of people with a previous diagnosis of BED developing BN [ 7 ].

A review of 79 studies also showed a significant number of individuals with BN (22.5%) crossed over to other diagnostic groups (mostly OSFED) at FU [ 63 ]. A large prospective study of female adolescents and young adults in the United States ( n = 9031) indicated that 12.9% of patients with BN later developed purging disorder and between 20 and 40% of individuals with subthreshold disorders progressed to full threshold disorders [ 64 ]. Progression from subthreshold to threshold eating disorders was higher for BN and BED (32% and 28%) than for AN (0%), with researchers suggesting higher risk for binge eating [ 66 ]. Progression from subthreshold to full threshold BN and BED was also common in adolescent females over the course of an 8 year observational study [ 33 ]. Some researchers contend that such diagnostic ‘instability’ demonstrates a need for ‘dimensional’ approaches to research and treatment which have greater focus on the severity rather than type of symptoms [ 7 ]. Diagnostic crossover is common and should be considered in the long-term management and monitoring of people with an ED.

Anorexia nervosa (AN)

People with restrictive-type ED have the poorest prognosis compared to the other diagnostic groups, particularly individuals displaying severe AN symptomatology (including lower weights and higher body image concerns) [ 44 ]. There is a paucity of effective pharmacological and/or psychological treatments for AN [ 65 ]. Reported rates of recovery vary and include 18% [ 56 ] to 52% at 6 year FU [ 7 ] to 60.3% at 13 year FU [ 20 ] and 62.8% at 22 year-FU [ 61 ]. Reported relapse rates in AN also vary, for example, 41.0% at 1 year post inpatient/day program treatment [ 35 ] to 30% at 22 year FU [ 61 ]. Average length of illness across the reviewed studies also varies from 6.5 years [ 56 ] to 14 years [ 41 ].

A variety of reported outcomes from treatment studies is likely due to the breadth of treatments under investigation, diverse study protocols and cohorts. For example, in a mixed cohort of female adult patients with AN and Atypical AN (A-AN), 33% were found to have made a full recovery at 3 year FU after treatment with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [ 57 ], while 6.4% had a bad outcome and 6.4% a severe outcome. However, in a 5–10 year FU study of paediatric inpatients (mean age 12.5 years) approximately 41% had a good outcome, while 35% had intermediate and 24% poor outcome [ 66 ]. Multimodal treatment approaches including psychiatric, nutritional, and psychological rehabilitation have been found to be most efficacious for moderate to severe and enduring AN but noting a discrete rate of improvement [ 67 ].

Very few factors were able to predict outcomes in AN. Higher baseline BMI was consistently found to be the strongest predictor of recovery, and better outcomes were associated with shorter duration of illness [ 7 , 55 , 61 , 66 ]. Earlier age of illness onset [ 59 , 68 , 69 ] and older age at presentation to treatment [ 30 ] were related to chronicity of illness and associated with poorer outcome.

There was a consensus across a variety of studies that engagement in binge/purge behaviours (Anorexia Nervosa Binge/Purge subtype; AN-BP) was associated with a poorer prognosis [ 20 , 56 , 70 ]. Similarly, individuals with severe and enduring AN restrictive sub-type (AN-R) are likely to have a better outcome than individuals with AN-BP. AN-BP was associated with a two-fold greater risk of relapse compared to AN-R [ 30 , 35 ]. Some studies, however, were unable to find an association between AN subtype and outcome [ 55 ]. Other factors leading to poorer outcome and higher probability of relapse were combined ED presentations, such as combined AN/BN [ 35 ], higher shape concern [ 57 ], lower desired weight/BMI [ 44 ], more ED psychopathology at EOT, low or decreasing motivation to recover, and comorbid depression [ 35 , 61 ].

Preliminary genetic work has found associations between a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in a ghrelin production gene (TT genotype at 3056 T-C) and recovery from AN-R [ 71 ], and the S-allele of the 5-HTTLPR genotype increasing the risk susceptibility for both depressive comorbidity and diagnostic crossover at FU of AN patients [ 72 ]. These studies, however, need to be interpreted with caution as they were conducted over a decade ago and have not since been replicated. Research in eating disorder genetics is a rapidly emerging area with potential clinical implications for assessment and treatment.

Bulimia nervosa (BN)

Overall, studies pertaining to a diagnostic profile of BN report remission recovery rates of around 40–60%, depending on criteria and FU period, as detailed below. Less than 40% of people achieved full symptom abstinence [ 73 ] and relapse occurred in around 30% of individuals [ 61 ]. A meta-analysis of 79 case series studies reported rates of recovery for BN at 45.0% for full recovery and 27.0% for partial remission, with 23.0% experiencing a chronic course and high rates of treatment dropout [ 63 ]. At 11 year FU, 38.0% reported remission in BN patients, increasing to 42.0% at 21 year [ 45 ]. At 22 year FU, 68.2% with BN were reported to have recovered [ 41 ]. Higher frequency of both objective binge episodes and self-induced vomiting factors influencing poorer outcomes [ 44 ].

Considering impact of treatment, analysis of engagement in self-induced vomiting as a predictor for outcome indicated there were no differences between groups in treatment dropout or response to CBT among a sample of 152 patients with various types of EDs (AN-BP, BN, EDNOS) at EOT [ 74 ]. Meta-analysis of results from 45 RCTs on psychotherapies for BN found 35.4% of treatment completers achieved symptom abstinence [ 73 ] with other studies indicating similar rates of recovery (around 52–59% depending on DSM criteria) [ 7 ].

Studies delivering CBT or other behavioural therapies reported the best outcomes for BN [ 73 ]. Specifically, early treatment progression, elimination of dietary restraint and normalisation of eating behaviour resulted in more positive outcomes [ 22 ]. These findings are supported by results from a study comparing outcomes of CBT and integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) [ 75 ]. Additional moderating effects were shown at FU (but not EOT), with greater improvements for those with less baseline depression, higher stimulus seeking (the need for excitement and stimulation) and affective lability (the experience of overly intense and unstable emotions) in the ICAT-BN group and lower stimulus seeking in the Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT-E) group. Lower affective lability showed improvements in both treatment groups [ 75 ]. Such findings indicate personality factors may deem one treatment approach more suitable to an individual than another.

A review of 4 RCTs of psychotherapy treatments for BN in adolescents (including FBT and CBT) reported overall psychological symptom improvement by EOT predicting better outcomes at 12 months, which underscored the need for not only behavioural but psychological improvement during 6 month treatment [ 31 ]. Other factors leading to poorer outcomes included less engagement in treatment, higher drive for thinness, less global functioning, and older age at presentation [ 45 ]. More research is needed into consistent predictors, mediators and moderators focused on treatment engagement and outcomes [ 22 ].

While many studies combine findings for BN and BED, one study specifically considered different emotions associated with binge eating within the two diagnostic profiles [ 60 ]. At baseline, binge eating was associated with anger/frustration for BN and depression for BED. At FU, objective binge eating (OBE) reduction in frequency (a measure of recovery) was associated with lower impulsivity and shape concern for BN but lower emotional eating and depressive symptoms for BED. These differences may provide approaches for effective intervention targets for differing presentations; however, how these may play out within a transdiagnostic approach requires further enquiry.

Binge eating disorder (BED)

BED is estimated to affect 1.5% of women and 0.3% of men worldwide, with higher prevalence (but more transient) in adolescents. Most adults report longstanding symptoms, 94% lifetime mental health conditions and 23% had attempted suicide, yet only half were in recognised healthcare or treatment [ 76 ].

Compared with AN and BN, long-term outcomes, and treatment success for individuals with BED were more favourable. Meta-analysis of BED abstinence rates suggests available psychotherapy and behavioural interventions are more effective for this population [ 77 ]. Additionally, stimulant medication (i.e., Vyvanse) has been found to be particularly effective to reduce binge eating [see [ 78 ] for full review]. Results from a study of people who received 12 months of CBT for BED indicated high rates of treatment response and favourable outcomes, maintained to 4 year FU. Significant improvements were observed with binge abstinence increasing from 30.0% at post-treatment to 67.0% at FU [ 79 ]. A meta-analysis reviewing psychological or behavioural treatments found Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) to be the treatment producing the greatest abstinence rates [ 73 ]. In a comparative study of IPT and CBT, people receiving CBT experienced increased ED symptoms between treatment and 4 year FU, while those who received IPT improved during the same period. Rates of remission at 4 year FU were also higher for IPT (76.7%) versus CBT (52.0%) [ 80 ].

One study specifically explored clinical differences between ED subtypes with and without lifetime obesity over 10 years. Prevalence of lifetime obesity in ED was 28.8% (ranging from 5% in AN to 87% in BED), with a threefold increase in lifetime obesity observed over the previous decade. Observed with temporal changes, people with ED and obesity had higher levels of childhood and family obesity, older-age onset, longer ED duration, higher levels of ED (particularly BED and BN) and poorer general psychopathology than those who were not in the obese weight range [ 81 ], suggesting greater clinical severity and poorer outcomes for people of higher weight.

Comparison of 6 year treatment outcomes between CBT and Behavioural Weight Loss Treatment (BWLT) found CBT more effective at post-treatment but fading effectiveness over time, with remission rates for both interventions lower than other reported studies (37%) [ 82 ]. A meta-analytic evaluation of 114 published and unpublished psychological and medical treatments found psychological treatments, structured self-help, and a combination of the two were all effective at EOT and 12 month FU but noted a wide variation in study design and quality, and the need for longer term FU. Efficacy and FU data for pharmacological and surgical weight loss treatments were lacking [ 77 ].

Whilst high weight and associated interventions (such as bariatric surgery) can be associated with any ED, they are frequently studied in relation to BED. A significant proportion of individuals seeking bariatric surgery (up to 42%) displayed binge eating symptomatology [ 83 ], yet little is known about the effect of these interventions on ED psychopathology and whether this differs by type of intervention. A systematic review of 23 studies of changes in ED behaviour following three different bariatric procedures found no specific procedure led to long term changes in ED profiles or behaviours [ 84 ]; however, another study investigating the placement of an intragastric balloon in obese patients found post-surgical reductions in grazing behaviours, emotional eating and EDNOS scores [ 85 ]. Bariatric surgery in general is associated with a reduction in ED, binge eating and depressive symptoms [ 86 ].

Outcomes among patients receiving bariatric surgery with and without BED were assessed where weight loss was comparable between the groups at 1 year FU. However, compared with participants receiving a BWLT-based lifestyle modification intervention instead of surgery, bariatric surgery patients lost significantly less weight at a 10.3% difference between groups. There was no significant difference between lifestyle modification and surgery groups in BED remission rates [ 87 ]. These results indicate that BLWT-type interventions are more effective than surgery at promoting weight loss in individuals with BED over a 1 year FU period, and people with BED and higher BMI were able to maintain weight loss in response to psychotherapy (CBT) at up to 5 year FU [ 88 ]. In analysis of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in people with BED who received various levels of CBT (therapist-led, therapist-assisted and self-help), evaluation indicated that all modalities resulted in improvements to HRQoL. Poorer outcomes were associated with obesity and ED symptom severity at presentation, stressing the importance of early detection and intervention measures [ 89 ]. Research into the role of CBT in strengthening the effect of bariatric surgery for obesity is ongoing but promising [ 90 ].

EDNOS, OSFED and UFED

Similarly to BED, a diagnosis of DSM-IV EDNOS (now OSFED) was associated with a more favourable outcome than AN or BN, including shorter time to remission. One study reported remission rates for both EDNOS and BED at 4 year FU of approximately 80% [ 21 ]. The researchers suggested that an ‘otherwise specified’ diagnostic group might be comprised of individuals transitioning into or out of an ED rather than between diagnostic categories; however, more work is needed in this area to fully understand this diagnostic profile. The reported recovery rate from EDNOS-A has been found to be much lower at 57% than for EDNOS-B at 80% (DSM-V). One factor suggested leading to poorer outcomes for EDNOS-A was a higher association with a co-occurring condition of major depression and/or dysthymia not found in other EDNOS subtypes [ 7 ]. Another study found purging occurred in 6.7% from total (cross-diagnostic) ED referrals, but this subtype did not have different post-treatment remission rates or completion rates compared to non-purging profiles [ 91 ], so results are mixed.

Acknowledging the scarcity of research within these diagnostic groups, remission rates for adolescents including those with a diagnosis of Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED) and Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder (UFED) was reported to be 23% at 12 month FU in the one study reviewed, but no detail was provided on recovery rates by diagnosis [ 26 ]. No available evidence was identified specifically for the DSM-V disorders OSFED or UFED for adults.

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

Research into outcomes for people with ARFID is lacking, with only three studies meeting criteria for the review [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. While, like AN, recovery for people with ARFID is usually measured by weight gain targets, one of the three studies [ 63 ] identified by this review instead reported on outcomes in terms of meeting a psychiatric diagnosis, making comparison between the studies difficult.

In a cross-diagnostic inpatient study, individuals presenting with ARFID were younger, had fewer reported ED behaviours and co-occurring conditions, less weight loss and were less likely to be bradycardic than individuals presenting with AN [ 25 ]. Although both groups received similar caloric intakes, ARFID patients relied on more enteral nutrition and required longer hospitalisations but had higher rates of remission and fewer readmissions than AN patients at 12 months. This study highlights the need for further investigation into inpatient treatment optimisation for different diagnostic profiles.

People with ARFID who had achieved remission post-treatment were able to maintain remission until 2.5 year FU, with most continuing to use outpatient treatment services [ 23 ]. In a 1 year FU study assessing ARFID, 62.0% of patients had achieved remission as defined by weight recovery and no longer meeting DSM-V criteria [ 25 ]. In a study following children treated for ARFID to a mean FU of 16 years post-treatment (age at FU 16.5–29.9 years), 26.3% continued to meet diagnostic criteria for ARFID with no diagnostic crossover, suggesting symptom stability [ 24 ]. Rates of recovery for ARFID patients in this study were not significantly different to the comparison group who had childhood onset AN, indicating similar prognoses for these disorders. No predictors of outcome for patients with ARFID were identified by the articles reviewed [ 63 ].

Community outcomes

While most outcome studies derive from health care settings, two studies were identified exploring outcomes of ED within the community. The first reported the 8 year prevalence, incidence, impairment, duration, and trajectory of ED via annual diagnostic interview of 496 adolescent females. Controlling for age, lifetime prevalence was 7.0% for BN/subthreshold BN, 6.6% for BED/subthreshold BED, 3.4% for purging disorder, 3.6% for AN/atypical AN, and 11.5% for feeding and eating disorders not otherwise classified. Peak onset age across the ED diagnostic profiles was 16–20 years with an average episode duration ranging from 3 months for BN to a year for AN; researchers noted that these episodes were shorter than the average duration estimates reported in similar research and may be representative of the transient nature of illness rather than longer term prognosis. ED were associated with greater functional impairment, distress, suicidality, and increased use of mental health treatment [ 27 ].