Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation | A Guide to Structure & Content

A dissertation or thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on original research, submitted as part of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

The structure of a dissertation depends on your field, but it is usually divided into at least four or five chapters (including an introduction and conclusion chapter).

The most common dissertation structure in the sciences and social sciences includes:

- An introduction to your topic

- A literature review that surveys relevant sources

- An explanation of your methodology

- An overview of the results of your research

- A discussion of the results and their implications

- A conclusion that shows what your research has contributed

Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an argument by analysing primary and secondary sources . Instead of the standard structure outlined here, you might organise your chapters around different themes or case studies.

Other important elements of the dissertation include the title page , abstract , and reference list . If in doubt about how your dissertation should be structured, always check your department’s guidelines and consult with your supervisor.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements, table of contents, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review / theoretical framework, methodology, reference list.

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation’s title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo. Many programs have strict requirements for formatting the dissertation title page .

The title page is often used as cover when printing and binding your dissertation .

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

The acknowledgements section is usually optional, and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you.

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150-300 words long. You should write it at the very end, when you’ve completed the rest of the dissertation. In the abstract, make sure to:

- State the main topic and aims of your research

- Describe the methods you used

- Summarise the main results

- State your conclusions

Although the abstract is very short, it’s the first part (and sometimes the only part) of your dissertation that people will read, so it’s important that you get it right. If you’re struggling to write a strong abstract, read our guide on how to write an abstract .

In the table of contents, list all of your chapters and subheadings and their page numbers. The dissertation contents page gives the reader an overview of your structure and helps easily navigate the document.

All parts of your dissertation should be included in the table of contents, including the appendices. You can generate a table of contents automatically in Word.

If you have used a lot of tables and figures in your dissertation, you should itemise them in a numbered list . You can automatically generate this list using the Insert Caption feature in Word.

If you have used a lot of abbreviations in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

If you have used a lot of highly specialised terms that will not be familiar to your reader, it might be a good idea to include a glossary . List the terms alphabetically and explain each term with a brief description or definition.

In the introduction, you set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance, and tell the reader what to expect in the rest of the dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving necessary background information to contextualise your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of the research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your objectives and research questions , and indicate how you will answer them

- Give an overview of your dissertation’s structure

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant to your research. By the end, the reader should understand the what , why and how of your research. Not sure how? Read our guide on how to write a dissertation introduction .

Before you start on your research, you should have conducted a literature review to gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic. This means:

- Collecting sources (e.g. books and journal articles) and selecting the most relevant ones

- Critically evaluating and analysing each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g. themes, patterns, conflicts, gaps) to make an overall point

In the dissertation literature review chapter or section, you shouldn’t just summarise existing studies, but develop a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear basis or justification for your own research. For example, it might aim to show how your research:

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Takes a new theoretical or methodological approach to the topic

- Proposes a solution to an unresolved problem

- Advances a theoretical debate

- Builds on and strengthens existing knowledge with new data

The literature review often becomes the basis for a theoretical framework , in which you define and analyse the key theories, concepts and models that frame your research. In this section you can answer descriptive research questions about the relationship between concepts or variables.

The methodology chapter or section describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to assess its validity. You should generally include:

- The overall approach and type of research (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, ethnographic)

- Your methods of collecting data (e.g. interviews, surveys, archives)

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Your methods of analysing data (e.g. statistical analysis, discourse analysis)

- Tools and materials you used (e.g. computer programs, lab equipment)

- A discussion of any obstacles you faced in conducting the research and how you overcame them

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Your aim in the methodology is to accurately report what you did, as well as convincing the reader that this was the best approach to answering your research questions or objectives.

Next, you report the results of your research . You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses, or topics. Only report results that are relevant to your objectives and research questions. In some disciplines, the results section is strictly separated from the discussion, while in others the two are combined.

For example, for qualitative methods like in-depth interviews, the presentation of the data will often be woven together with discussion and analysis, while in quantitative and experimental research, the results should be presented separately before you discuss their meaning. If you’re unsure, consult with your supervisor and look at sample dissertations to find out the best structure for your research.

In the results section it can often be helpful to include tables, graphs and charts. Think carefully about how best to present your data, and don’t include tables or figures that just repeat what you have written – they should provide extra information or usefully visualise the results in a way that adds value to your text.

Full versions of your data (such as interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix .

The discussion is where you explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research questions. Here you should interpret the results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data and discuss any limitations that might have influenced the results.

The discussion should reference other scholarly work to show how your results fit with existing knowledge. You can also make recommendations for future research or practical action.

The dissertation conclusion should concisely answer the main research question, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your central argument. Wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you did and how you did it. The conclusion often also includes recommendations for research or practice.

In this section, it’s important to show how your findings contribute to knowledge in the field and why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known?

You must include full details of all sources that you have cited in a reference list (sometimes also called a works cited list or bibliography). It’s important to follow a consistent reference style . Each style has strict and specific requirements for how to format your sources in the reference list.

The most common styles used in UK universities are Harvard referencing and Vancouver referencing . Your department will often specify which referencing style you should use – for example, psychology students tend to use APA style , humanities students often use MHRA , and law students always use OSCOLA . M ake sure to check the requirements, and ask your supervisor if you’re unsure.

To save time creating the reference list and make sure your citations are correctly and consistently formatted, you can use our free APA Citation Generator .

Your dissertation itself should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents you have used that do not fit into the main body of your dissertation (such as interview transcripts, survey questions or tables with full figures) can be added as appendices .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation binding and printing

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- Dissertation title page

- Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

- Figure & Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="dissertation on or about"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Guide to writing your thesis/dissertation, definition of dissertation and thesis.

The dissertation or thesis is a scholarly treatise that substantiates a specific point of view as a result of original research that is conducted by students during their graduate study. At Cornell, the thesis is a requirement for the receipt of the M.A. and M.S. degrees and some professional master’s degrees. The dissertation is a requirement of the Ph.D. degree.

Formatting Requirement and Standards

The Graduate School sets the minimum format for your thesis or dissertation, while you, your special committee, and your advisor/chair decide upon the content and length. Grammar, punctuation, spelling, and other mechanical issues are your sole responsibility. Generally, the thesis and dissertation should conform to the standards of leading academic journals in your field. The Graduate School does not monitor the thesis or dissertation for mechanics, content, or style.

“Papers Option” Dissertation or Thesis

A “papers option” is available only to students in certain fields, which are listed on the Fields Permitting the Use of Papers Option page , or by approved petition. If you choose the papers option, your dissertation or thesis is organized as a series of relatively independent chapters or papers that you have submitted or will be submitting to journals in the field. You must be the only author or the first author of the papers to be used in the dissertation. The papers-option dissertation or thesis must meet all format and submission requirements, and a singular referencing convention must be used throughout.

ProQuest Electronic Submissions

The dissertation and thesis become permanent records of your original research, and in the case of doctoral research, the Graduate School requires publication of the dissertation and abstract in its original form. All Cornell master’s theses and doctoral dissertations require an electronic submission through ProQuest, which fills orders for paper or digital copies of the thesis and dissertation and makes a digital version available online via their subscription database, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses . For master’s theses, only the abstract is available. ProQuest provides worldwide distribution of your work from the master copy. You retain control over your dissertation and are free to grant publishing rights as you see fit. The formatting requirements contained in this guide meet all ProQuest specifications.

Copies of Dissertation and Thesis

Copies of Ph.D. dissertations and master’s theses are also uploaded in PDF format to the Cornell Library Repository, eCommons . A print copy of each master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation is submitted to Cornell University Library by ProQuest.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Theses and Dissertations

- Academic Integrity

- Using Sources and AI

- Academic Writing

- From Research to Writing

- GSD Writing Services

- Grants and Fellowships

- Reading, Notetaking, and Time Management

What is a thesis?

What is a dissertation, getting started, staying on track, thesis abstract, lit(erature) review.

A thesis is a long-term project that you work on over the course of a semester or a year. Theses have a very wide variety of styles and content, so we encourage you to look at prior examples and work closely with faculty to develop yours.

Before you begin, make sure that you are familiar with the dissertation genre—what it is for and what it looks like.

Generally speaking, a dissertation’s purpose is to prove that you have the expertise necessary to fulfill your doctoral-degree requirements by showing depth of knowledge and independent thinking.

The form of a dissertation may vary by discipline. Be sure to follow the specific guidelines of your department.

- PhD This site directs candidates to the GSAS website about dissertations , with links to checklists, planning, formatting, acknowledgments, submission, and publishing options. There is also a link to guidelines for the prospectus . Consult with your committee chair about specific requirements and standards for your dissertation.

- DDES This document covers planning, patent filing, submission guidelines, publishing options, formatting guidelines, sample pages, citation guidelines, and a list of common errors to avoid. There is also a link to guidelines for the prospectus .

- Scholarly Pursuits (GSAS) This searchable booklet from Harvard GSAS is a comprehensive guide to writing dissertations, dissertation-fellowship applications, academic journal articles, and academic job documents.

Finding an original topic can be a daunting and overwhelming task. These key concepts can help you focus and save time.

Finding a topic for your thesis or dissertation should start with a research question that excites or at least interests you. A rigorous, engaging, and original project will require continuous curiosity about your topic, about your own thoughts on the topic, and about what other scholars have said on your topic. Avoid getting boxed in by thinking you know what you want to say from the beginning; let your research and your writing evolve as you explore and fine-tune your focus through constant questioning and exploration.

Get a sense of the broader picture before you narrow your focus and attempt to frame an argument. Read, skim, and otherwise familiarize yourself with what other scholars have done in areas related to your proposed topic. Briefly explore topics tangentially related to yours to broaden your perspective and increase your chance of finding a unique angle to pursue.

Critical Reading

Critical reading is the opposite of passive reading. Instead of merely reading for information to absorb, critical reading also involves careful, sustained thinking about what you are reading. This process may include analyzing the author’s motives and assumptions, asking what might be left out of the discussion, considering what you agree with or disagree with in the author’s statements and why you agree or disagree, and exploring connections or contradictions between scholarly arguments. Here is a resource to help hone your critical-reading skills:

https://guides.library.harvard.edu/sixreadinghabits

https://youtu.be/BcV64lowMIA

Conversation

Your thesis or dissertation will incorporate some ideas from other scholars whose work you researched. By reading critically and following your curiosity, you will develop your own ideas and claims, and these contributions are the core of your project. You will also acknowledge the work of scholars who came before you, and you must accurately and fairly attribute this work and define your place within the larger discussion. Make sure that you know how to quote, summarize, paraphrase , integrate , and cite sources to avoid plagiarism and to show the depth and breadth of your knowledge.

A thesis is a long-term, large project that involves both research and writing; it is easy to lose focus, motivation, and momentum. Here are suggestions for achieving the result you want in the time you have.

The dissertation is probably the largest project you have undertaken, and a lot of the work is self-directed. The project can feel daunting or even overwhelming unless you break it down into manageable pieces and create a timeline for completing each smaller task. Be realistic but also challenge yourself, and be forgiving of yourself if you miss a self-imposed deadline here and there.

Your program will also have specific deadlines for different requirements, including establishing a committee, submitting a prospectus, completing the dissertation, defending the dissertation, and submitting your work. Consult your department’s website for these dates and incorporate them into the timeline for your work.

Accountability

Sometimes self-imposed deadlines do not feel urgent unless there is accountability to someone beyond yourself. To increase your motivation to complete tasks on schedule, set dates with your committee chair to submit pre-determined pieces of a chapter. You can also arrange with a fellow doctoral student to check on each other’s progress. Research and writing can be lonely, so it is also nice to share that journey with someone and support each other through the process.

Common Pitfalls

The most common challenges for students writing a dissertation are writer’s block, information-overload, and the compulsion to keep researching forever.

There are many strategies for avoiding writer’s block, such as freewriting, outlining, taking a walk, starting in the middle, and creating an ideal work environment for your particular learning style. Pay attention to what helps you and try different things until you find what works.

Efficient researching techniques are essential to avoiding information-overload. Here are a couple of resources about strategies for finding sources and quickly obtaining essential information from them.

https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/writing_in_literature/writing_in_literature_detailed_discussion/reading_criticism.html

https://students.dartmouth.edu/academic-skills/learning-resources/learning-strategies/reading-techniques

Finally, remember that there is always more to learn and your dissertation cannot incorporate everything. Follow your curiosity but also set limits on the scope of your work. It helps to create a folder entitled “future projects” for topics and sources that interest you but that do not fit neatly into the dissertation. Also remember that future scholars will build off of your work, so leave something for them to do.

An abstract is a short (approximately 200-word) summary or overview of your research project. It provides enough information for a reader to know what they will find within the larger document, such as your purpose, methodology, and results or conclusion. It may also include a list of keywords. An abstract is an original document, not an excerpt, and its contents and organization may vary by discipline.

A literature review establishes a set of themes and contexts drawn from foundational research and materials that relate to your project. It is an acknowledgment that your scholarship doesn’t exist in a vacuum. With the review, you identify patterns and trends in the literature to situate your contribution within the existing scholarly conversation.

What is a literature review? A literature review (or lit review, for short) is a critical analysis of published scholarly research (the "literature") related to a specific topic. Literature here means body of work, which traditionally was done in written form and may include journal articles, books, book chapters, dissertations and thesis, or conference proceedings. In the case of design, however, literature has an expanded breadth since the body of work is oftentimes not represented by words. A design review may include plans, sections, photographs, and any type of media that portrays the work.

A literature review may stand on its own or may be inside a larger work, usually in the introductory sections. It is thorough but not exhaustive--there will always be more information than you can reasonably locate and include. Be mindful of your scope and time constraints and select your reviewed materials with care. A literature review

- summarizes the themes and findings of works in an area

- compares and contrasts relevant aspects of literature on a topic

- critically assesses the strengths and omissions of the source material

- elaborates on the implications of their findings for one's own research topic

What does a literature review look like? Each discipline has its own style for writing a literature review; urban planning and design lit reviews may look different than those from architecture, and design lit reviews will look significantly different than reviews from the biological sciences or engineering. Look at published journal articles within your field and note how they present the information.

- Introduction: most scholarly articles and books will have a literature review within the introductory sections. Its precise location may vary, but it is most often in the first few paragraphs or pages.

Dedicated literature reviews: these are stand-alone resources unto themselves. You can search for "literature review" and a topic, and you may find that one already exists. These literature reviews are useful as models within your field, for finding additional sources to explore, and for beginning to map the general relationships within the scholarly conversation around your topic. Be mindful not to plagiarize the source material.

Database search tip : Add the phrase "literature review" to your search to find published literature reviews.

Browsing through theses and dissertations of the past can help to get a sense of your options and gain inspiration but be careful to use current guidelines and refer to your committee instead of relying on these examples for form or formatting.

Theses at the Frances Loeb Library is a research guide to finding p ast GSD theses.

DASH Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard.

HOLLIS Harvard Library’s catalog provides access to ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global .

MIT Architecture has a list of their graduates’ dissertations and theses.

Rhode Island School of Design has a list of their graduates’ dissertations and theses.

University of South Florida has a list of their graduates’ dissertations and theses.

Harvard GSD has a list of projects, including theses and professors’ research.

- << Previous: Reading, Notetaking, and Time Management

- Next: Publishing >>

- Last Updated: Oct 8, 2024 3:11 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

How to Write a Dissertation: Step-by-Step Guide

- Doctoral students write and defend dissertations to earn their degrees.

- Most dissertations range from 100-300 pages, depending on the field.

- Taking a step-by-step approach can help students write their dissertations.

Whether you’re considering a doctoral program or you recently passed your comprehensive exams, you’ve probably wondered how to write a dissertation. Researching, writing, and defending a dissertation represents a major step in earning a doctorate.

But what is a dissertation exactly? A dissertation is an original work of scholarship that contributes to the field. Doctoral candidates often spend 1-3 years working on their dissertations. And many dissertations top 200 or more pages.

Starting the process on the right foot can help you complete a successful dissertation. Breaking down the process into steps may also make it easier to finish your dissertation.

How to Write a Dissertation in 12 Steps

A dissertation demonstrates mastery in a subject. But how do you write a dissertation? Here are 12 steps to successfully complete a dissertation.

Choose a Topic

It sounds like an easy step, but choosing a topic will play an enormous role in the success of your dissertation. In some fields, your dissertation advisor will recommend a topic. In other fields, you’ll develop a topic on your own.

Read recent work in your field to identify areas for additional scholarship. Look for holes in the literature or questions that remain unanswered.

After coming up with a few areas for research or questions, carefully consider what’s feasible with your resources. Talk to your faculty advisor about your ideas and incorporate their feedback.

Conduct Preliminary Research

Before starting a dissertation, you’ll need to conduct research. Depending on your field, that might mean visiting archives, reviewing scholarly literature , or running lab tests.

Use your preliminary research to hone your question and topic. Take lots of notes, particularly on areas where you can expand your research.

Read Secondary Literature

A dissertation demonstrates your mastery of the field. That means you’ll need to read a large amount of scholarship on your topic. Dissertations typically include a literature review section or chapter.

Create a list of books, articles, and other scholarly works early in the process, and continue to add to your list. Refer to the works cited to identify key literature. And take detailed notes to make the writing process easier.

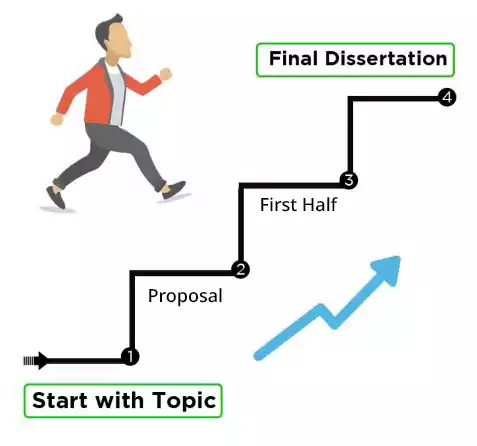

Write a Research Proposal

In most doctoral programs, you’ll need to write and defend a research proposal before starting your dissertation.

The length and format of your proposal depend on your field. In many fields, the proposal will run 10-20 pages and include a detailed discussion of the research topic, methodology, and secondary literature.

Your faculty advisor will provide valuable feedback on turning your proposal into a dissertation.

Research, Research, Research

Doctoral dissertations make an original contribution to the field, and your research will be the basis of that contribution.

The form your research takes will depend on your academic discipline. In computer science, you might analyze a complex dataset to understand machine learning. In English, you might read the unpublished papers of a poet or author. In psychology, you might design a study to test stress responses. And in education, you might create surveys to measure student experiences.

Work closely with your faculty advisor as you conduct research. Your advisor can often point you toward useful resources or recommend areas for further exploration.

Look for Dissertation Examples

Writing a dissertation can feel overwhelming. Most graduate students have written seminar papers or a master’s thesis. But a dissertation is essentially like writing a book.

Looking at examples of dissertations can help you set realistic expectations and understand what your discipline wants in a successful dissertation. Ask your advisor if the department has recent dissertation examples. Or use a resource like ProQuest Dissertations to find examples.

Doctoral candidates read a lot of monographs and articles, but they often do not read dissertations. Reading polished scholarly work, particularly critical scholarship in your field, can give you an unrealistic standard for writing a dissertation.

Write Your Body Chapters

By the time you sit down to write your dissertation, you’ve already accomplished a great deal. You’ve chosen a topic, defended your proposal, and conducted research. Now it’s time to organize your work into chapters.

As with research, the format of your dissertation depends on your field. Your department will likely provide dissertation guidelines to structure your work. In many disciplines, dissertations include chapters on the literature review, methodology, and results. In other disciplines, each chapter functions like an article that builds to your overall argument.

Start with the chapter you feel most confident in writing. Expand on the literature review in your proposal to provide an overview of the field. Describe your research process and analyze the results.

Meet With Your Advisor

Throughout the dissertation process, you should meet regularly with your advisor. As you write chapters, send them to your advisor for feedback. Your advisor can help identify issues and suggest ways to strengthen your dissertation.

Staying in close communication with your advisor will also boost your confidence for your dissertation defense. Consider sharing material with other members of your committee as well.

Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

It seems counterintuitive, but it’s a good idea to write your introduction and conclusion last . Your introduction should describe the scope of your project and your intervention in the field.

Many doctoral candidates find it useful to return to their dissertation proposal to write the introduction. If your project evolved significantly, you will need to reframe the introduction. Make sure you provide background information to set the scene for your dissertation. And preview your methodology, research aims, and results.

The conclusion is often the shortest section. In your conclusion, sum up what you’ve demonstrated, and explain how your dissertation contributes to the field.

Edit Your Draft

You’ve completed a draft of your dissertation. Now, it’s time to edit that draft.

For some doctoral candidates, the editing process can feel more challenging than researching or writing the dissertation. Most dissertations run a minimum of 100-200 pages , with some hitting 300 pages or more.

When editing your dissertation, break it down chapter by chapter. Go beyond grammar and spelling to make sure you communicate clearly and efficiently. Identify repetitive areas and shore up weaknesses in your argument.

Incorporate Feedback

Writing a dissertation can feel very isolating. You’re focused on one topic for months or years, and you’re often working alone. But feedback will strengthen your dissertation.

You will receive feedback as you write your dissertation, both from your advisor and other committee members. In many departments, doctoral candidates also participate in peer review groups to provide feedback.

Outside readers will note confusing sections and recommend changes. Make sure you incorporate the feedback throughout the writing and editing process.

Defend Your Dissertation

Congratulations — you made it to the dissertation defense! Typically, your advisor will not let you schedule the defense unless they believe you will pass. So consider the defense a culmination of your dissertation process rather than a high-stakes examination.

The format of your defense depends on the department. In some fields, you’ll present your research. In other fields, the defense will consist of an in-depth discussion with your committee.

Walk into your defense with confidence. You’re now an expert in your topic. Answer questions concisely and address any weaknesses in your study. Once you pass the defense, you’ll earn your doctorate.

Writing a dissertation isn’t easy — only around 55,000 students earned a Ph.D. in 2020, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. However, it is possible to successfully complete a dissertation by breaking down the process into smaller steps.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dissertations

What is a dissertation.

A dissertation is a substantial research project that contributes to your field of study. Graduate students write a dissertation to earn their doctorate.

The format and content of a dissertation vary widely depending on the academic discipline. Doctoral candidates work closely with their faculty advisor to complete and defend the dissertation, a process that typically takes 1-3 years.

How long is a dissertation?

The length of a dissertation varies by field. Harvard’s graduate school says most dissertations fall between 100-300 pages .

Doctoral candidate Marcus Beck analyzed the length of University of Minnesota dissertations by discipline and found that history produces the longest dissertations, with an average of nearly 300 pages, while mathematics produces the shortest dissertations at just under 100 pages.

What’s the difference between a dissertation vs. a thesis?

Dissertations and theses demonstrate academic mastery at different levels. In U.S. graduate education, master’s students typically write theses, while doctoral students write dissertations. The terms are reversed in the British system.

In the U.S., a dissertation is longer, more in-depth, and based on more research than a thesis. Doctoral candidates write a dissertation as the culminating research project of their degree. Undergraduates and master’s students may write shorter theses as part of their programs.

Explore More College Resources

How to Write an Effective Thesis Statement

by Staff Writers

Updated December 6, 2022

How to Write a Research Paper: 11-Step Guide

by Samantha Fecich, Ph.D.

Updated January 17, 2023

How to Write a History Essay, According to a History Professor

by Genevieve Carlton, Ph.D.

Updated April 13, 2022

View the most relevant schools for your interests and compare them by tuition, programs, acceptance rate, and other factors important to finding your college home.

- How it works

A Step-By-Step Guide to Write the Perfect Dissertation

“A dissertation or a thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on comprehensive research.”

The significance of dissertation writing in the world of academia is unparalleled. A good dissertation paper needs months of research and marks the end of your respected academic journey. It is considered the most effective form of writing in academia and perhaps the longest piece of academic writing you will ever have to complete.

This thorough step-by-step guide on how to write a dissertation will serve as a tool to help you with the task at hand, whether you are an undergraduate student or a Masters or PhD student working on your dissertation project. This guide provides detailed information about how to write the different chapters of a dissertation, such as a problem statement , conceptual framework , introduction , literature review, methodology , discussion , findings , conclusion , title page , acknowledgements , etc.

What is a Dissertation? – Definition

Before we list the stages of writing a dissertation, we should look at what a dissertation is.

The Cambridge dictionary states that a dissertation is a long piece of writing on a particular subject, especially one that is done to receive a degree at college or university, but that is just the tip of the iceberg because a dissertation project has a lot more meaning and context.

To understand a dissertation’s definition, one must have the capability to understand what an essay is. A dissertation is like an extended essay that includes research and information at a much deeper level. Despite the few similarities, there are many differences between an essay and a dissertation.

Another term that people confuse with a dissertation is a thesis. Let's look at the differences between the two terms.

What is the Difference Between a Dissertation and a Thesis?

Dissertation and thesis are used interchangeably worldwide (and may vary between universities and regions), but the key difference is when they are completed. The thesis is a project that marks the end of a degree program, whereas the dissertation project can occur during the degree. Hanno Krieger (Researchgate, 2014) explained the difference between a dissertation and a thesis as follows:

“Thesis is the written form of research work to claim an academic degree, like PhD thesis, postgraduate thesis, and undergraduate thesis. On the other hand, a dissertation is only another expression of the written research work, similar to an essay. So the thesis is the more general expression.

In the end, it does not matter whether it is a bachelor's, master or PhD dissertation one is working on because the structure and the steps of conducting research are pretty much identical. However, doctoral-level dissertation papers are much more complicated and detailed.

Problems Students Face When Writing a Dissertation

You can expect to encounter some troubles if you don’t yet know the steps to write a dissertation. Even the smartest students are overwhelmed by the complexity of writing a dissertation.

A dissertation project is different from any essay paper you have ever committed to because of the details of planning, research and writing it involves. One can expect rewarding results at the end of the process if the correct guidelines are followed. Still, as indicated previously, there will be multiple challenges to deal with before reaching that milestone.

The three most significant problems students face when working on a dissertation project are the following.

Poor Project Planning

Delaying to start working on the dissertation project is the most common problem. Students think they have sufficient time to complete the paper and are finding ways to write a dissertation in a week, delaying the start to the point where they start stressing out about the looming deadline. When the planning is poor, students are always looking for ways to write their dissertations in the last few days. Although it is possible, it does have effects on the quality of the paper.

Inadequate Research Skills

The writing process becomes a huge problem if one has the required academic research experience. Professional dissertation writing goes well beyond collecting a few relevant reference resources.

You need to do both primary and secondary research for your paper. Depending on the dissertation’s topic and the academic qualification you are a candidate for, you may be required to base your dissertation paper on primary research.

In addition to secondary data, you will also need to collect data from the specified participants and test the hypothesis . The practice of primary collection is time-consuming since all the data must be analysed in detail before results can be withdrawn.

Failure to Meet the Strict Academic Writing Standards

Research is a crucial business everywhere. Failure to follow the language, style, structure, and formatting guidelines provided by your department or institution when writing the dissertation paper can worsen matters. It is recommended to read the dissertation handbook before starting the write-up thoroughly.

Steps of Writing a Dissertation

For those stressing out about developing an extensive paper capable of filling a gap in research whilst adding value to the existing academic literature—conducting exhaustive research and analysis—and professionally using the knowledge gained throughout their degree program, there is still good news in all the chaos.

We have put together a guide that will show you how to start your dissertation and complete it carefully from one stage to the next.

Find an Interesting and Manageable Dissertation Topic

A clearly defined topic is a prerequisite for any successful independent research project. An engaging yet manageable research topic can produce an original piece of research that results in a higher academic score.

Unlike essays or assignments, when working on their thesis or dissertation project, students get to choose their topic of research.

You should follow the tips to choose the correct topic for your research to avoid problems later. Your chosen dissertation topic should be narrow enough, allowing you to collect the required secondary and primary data relatively quickly.

Understandably, many people take a lot of time to search for the topic, and a significant amount of research time is spent on it. You should talk to your supervisor or check out the intriguing database of ResearchProspect’s free topics for your dissertation.

Alternatively, consider reading newspapers, academic journals, articles, course materials, and other media to identify relevant issues to your study area and find some inspiration to get going.

You should work closely with your supervisor to agree to a narrowed but clear research plan.Here is what Michelle Schneider, learning adviser at the University of Leeds, had to say about picking the research topics,

“Picking something you’re genuinely interested in will keep you motivated. Consider why it’s important to tackle your chosen topic," Michelle added.

Develop a First-Class Dissertation Proposal.

Once the research topic has been selected, you can develop a solid dissertation proposal . The research proposal allows you to convince your supervisor or the committee members of the significance of your dissertation.

Through the proposal, you will be expected to prove that your work will significantly value the academic and scientific communities by addressing complex and provocative research questions .

Dissertation proposals are much shorter but follow a similar structure to an extensive dissertation paper. If the proposal is optional in your university, you should still create one outline of the critical points that the actual dissertation paper will cover. To get a better understanding of dissertation proposals, you can also check the publicly available samples of dissertation proposals .

Typical contents of the dissertation paper are as follows;

- A brief rationale for the problem your dissertation paper will investigate.

- The hypothesis you will be testing.

- Research objectives you wish to address.

- How will you contribute to the knowledge of the scientific and academic community?

- How will you find answers to the critical research question(s)?

- What research approach will you adopt?

- What kind of population of interest would you like to generalise your result(s) to (especially in the case of quantitative research)?

- What sampling technique(s) would you employ, and why would you not use other methods?

- What ethical considerations have you taken to gather data?

- Who are the stakeholders in your research are/might be?

- What are the future implications and limitations you see in your research?

Let’s review the structure of the dissertation. Keep the format of your proposal simple. Keeping it simple keeps your readers will remain engaged. The following are the fundamental focal points that must be included:

Title of your dissertation: Dissertation titles should be 12 words in length. The focus of your research should be identifiable from your research topic.

Research aim: The overall purpose of your study should be clearly stated in terms of the broad statements of the desired outcomes in the Research aim. Try and paint the picture of your research, emphasising what you wish to achieve as a researcher.

Research objectives: The key research questions you wish to address as part of the project should be listed. Narrow down the focus of your research and aim for at most four objectives. Your research objectives should be linked with the aim of the study or a hypothesis.

Literature review: Consult with your supervisor to check if you are required to use any specific academic sources as part of the literature review process. If that is not the case, find out the most relevant theories, journals, books, schools of thought, and publications that will be used to construct arguments in your literature research.Remember that the literature review is all about giving credit to other authors’ works on a similar topic

Research methods and techniques: Depending on your dissertation topic, you might be required to conduct empirical research to satisfy the study’s objectives. Empirical research uses primary data such as questionnaires, interview data, and surveys to collect.

On the other hand, if your dissertation is based on secondary (non-empirical) data, you can stick to the existing literature in your area of study. Clearly state the merits of your chosen research methods under the methodology section.

Expected results: As you explore the research topic and analyse the data in the previously published papers, you will begin to build your expectations around the study’s potential outcomes. List those expectations here.

Project timeline: Let the readers know exactly how you plan to complete all the dissertation project parts within the timeframe allowed. You should learn more about Microsoft Project and Gantt Charts to create easy-to-follow and high-level project timelines and schedules.

References: The academic sources used to gather information for the proposed paper will be listed under this section using the appropriate referencing style. Ask your supervisor which referencing style you are supposed to follow.

The proposals we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Investigation, Research and Data Collection

This is the most critical stage of the dissertation writing process. One should use up-to-date and relevant academic sources that are likely to jeopardise hard work.

Finding relevant and highly authentic reference resources is the key to succeeding in the dissertation project, so it is advised to take your time with this process. Here are some of the things that should be considered when conducting research.

dissertation project, so it is advised to take your time with this process. Here are some of the things that should be considered when conducting research.

You cannot read everything related to your topic. Although the practice of reading as much material as possible during this stage is rewarding, it is also imperative to understand that it is impossible to read everything that concerns your research.

This is true, especially for undergraduate and master’s level dissertations that must be delivered within a specific timeframe. So, it is important to know when to stop! Once the previous research and the associated limitations are well understood, it is time to move on.

However, review at least the salient research and work done in your area. By salient, we mean research done by pioneers of your field. For instance, if your topic relates to linguistics and you haven’t familiarised yourself with relevant research conducted by, say, Chomsky (the father of linguistics), your readers may find your lack of knowledge disconcerting.

So, to come off as genuinely knowledgeable in your own field, at least don’t forget to read essential works in the field/topic!

Use an Authentic Research database to Find References.

Most students start the reference material-finding process with desk-based research. However, this research method has its own limitation because it is a well-known fact that the internet is full of bogus information and fake information spreads fasters on the internet than truth does .

So, it is important to pick your reference material from reliable resources such as Google Scholar , Researchgate, Ibibio and Bartleby . Wikipedia is not considered a reliable academic source in the academic world, so it is recommended to refrain from citing Wikipedia content.Never underrate the importance of the actual library. The supporting staff at a university library can be of great help when it comes to finding exciting and reliable publications.

Record as you learn

All information and impressions should be recorded as notes using online tools such as Evernote to make sure everything is clear. You want to retain an important piece of information you had planned to present as an argument in the dissertation paper.

Write a Flawless Dissertation

Start to write a fantastic dissertation immediately once your proposal has been accepted and all the necessary desk-based research has been conducted. Now we will look at the different chapters of a dissertation in detail. You can also check out the samples of dissertation chapters to fully understand the format and structures of the various chapters.

Dissertation Introduction Chapter

The introduction chapter of the dissertation paper provides the background, problem statement and research questions. Here, you will inform the readers why it was important for this research to be conducted and which key research question(s) you expect to answer at the end of the study.

Definitions of all the terms and phrases in the project are provided in this first chapter of the dissertation paper. The research aim and objectives remain unchanged from the proposal paper and are expected to be listed under this section.

Dissertation Literature Review Chapter

This chapter allows you to demonstrate to your readers that you have done sufficient research on the chosen topic and understand previous similar studies’ findings. Any research limitations that your research incorporates are expected to be discussed in this section.

And make sure to summarise the viewpoints and findings of other researchers in the dissertation literature review chapter. Show the readers that there is a research gap in the existing work and your job is relevant to it to justify your research value.

Dissertation Methodology

The methodology chapter of the dissertation provides insight into the methods employed to collect data from various resources and flows naturally from the literature review chapter.Simply put, you will be expected to explain what you did and how you did it, helping the readers understand that your research is valid and reliable. When writing the methodology chapter for the dissertation, make sure to emphasise the following points:

- The type of research performed by the researcher

- Methods employed to gather and filter information

- Techniques that were chosen for analysis

- Materials, tools and resources used to conduct research (typically for empirical research dissertations)

- Limitations of your chosen methods

- Reliability and validity of your measuring tools and instruments (e.g. a survey questionnaire) are also typically mentioned within the mythology section. If you used a pre-existing data collection tool, cite its reliability/validity estimates here, too.Make use of the past tense when writing the methodology chapter.

Dissertation Findings

The key results of your research are presented in the dissertation findings chapter . It gives authors the ability to validate their own intellectual and analytical skills

Dissertation Conclusion

Cap off your dissertation paper with a study summary and a brief report of the findings. In the concluding chapter , you will be expected to demonstrate how your research will provide value to other academics in your area of study and its implications.It is recommended to include a short ‘recommendations’ section that will elaborate on the purpose and need for future research to elucidate the topic further.

Follow the referencing style following the requirements of your academic degree or field of study. Make sure to list every academic source used with a proper in-text citation. It is important to give credit to other authors’ ideas and concepts.

Note: Keep in mind whether you are creating a reference list or a bibliography. The former includes information about all the various sources you referred to, read from or took inspiration from for your own study. However, the latter contains things you used and those you only read but didn’t cite in your dissertation.

Proofread, Edit and Improve – Don’t Risk Months of Hard Work.

Experts recommend completing the total dissertation before starting to proofread and edit your work. You need to refresh your focus and reboot your creative brain before returning to another critical stage.

Leave space of at least a few days between the writing and the editing steps so when you get back to the desk, you can recognise your grammar, spelling and factual errors when you get back to the desk.

It is crucial to consider this period to ensure the final work is polished, coherent, well-structured and free of any structural or factual flaws. Daniel Higginbotham from Prospects UK states that:

“Leave yourself sufficient time to engage with your writing at several levels – from reassessing the logic of the whole piece to proofreading to checking you’ve paid attention to aspects such as the correct spelling of names and theories and the required referencing format.”

What is the Difference Between Editing and Proofreading?

Editing means that you are focusing on the essence of your dissertation paper. In contrast, proofreading is the process of reviewing the final draft piece to ensure accuracy and consistency in formatting, spelling, facts, punctuation, and grammar.

Editing: Prepare your work for submission by condensing, correcting and modifying (where necessary). When reviewing the paper, make sure that there are coherence and consistency between the arguments you presented.

If an information gap has been identified, fill that with an appropriate piece of information gathered during the research process. It is easy to lose sight of the original purpose if you become over-involved when writing.

Cut out the unwanted text and refine it, so your paper’s content is to the point and concise.Proofreading: Start proofreading your paper to identify formatting, structural, grammar, punctuation and referencing flaws. Read every single sentence of the paper no matter how tired you are because a few puerile mistakes can compromise your months of hard work.

Many students struggle with the editing and proofreading stages due to their lack of attention to detail. Consult a skilled dissertation editor if you are unable to find your flaws. You may want to invest in a professional dissertation editing and proofreading service to improve the piece’s quality to First Class.

Tips for Writing a Dissertation

Communication with supervisor – get feedback.

Communicate regularly with your supervisor to produce a first-class dissertation paper. Request them to comprehensively review the contents of your dissertation paper before final submission.

Their constructive criticism and feedback concerning different study areas will help you improve your piece’s overall quality. Keep your supervisor updated about your research progress and discuss any problems that you come up against.

Organising your Time

A dissertation is a lengthy project spanning over a period of months to years, and therefore it is important to avoid procrastination. Stay focused, and manage your time efficiently. Here are some time management tips for writing your dissertation to help you make the most of your time as you research and write.

- Don’t be discouraged by the inherently slow nature of dissertation work, particularly in the initial stages.

- Set clear goals and work out your research and write up a plan accordingly.

- Allow sufficient time to incorporate feedback from your supervisor.

- Leave enough time for editing, improving, proofreading, and formatting the paper according to your school’s guidelines. This is where you break or make your grade.

- Work a certain number of hours on your paper daily.

- Create a worksheet for your week.

- Work on your dissertation for time periods as brief as 45 minutes or less.

- Stick to the strategic dissertation timeline, so you don’t have to do the catchup work.

- Meet your goals by prioritising your dissertation work.

- Strike a balance between being overly organised and needing to be more organised.

- Limit activities other than dissertation writing and your most necessary obligations.

- Keep ‘tangent’ and ‘for the book’ files.

- Create lists to help you manage your tasks.

- Have ‘filler’ tasks to do when you feel burned out or in need of intellectual rest.

- Keep a dissertation journal.

- Pretend that you are working in a more structured work world.

- Limit your usage of email and personal electronic devices.

- Utilise and build on your past work when you write your dissertation.

- Break large tasks into small manageable ones.

- Seek advice from others, and do not be afraid to ask for help.

Dissertation Examples

Here are some samples of a dissertation to inspire you to write mind-blowing dissertations and to help bring all the above-mentioned guidelines home.

DE MONTFORT University Leicester – Examples of recent dissertations

Dissertation Research in Education: Dissertations (Examples)

How Long is a Dissertation?

The entire dissertation writing process is complicated and spans over a period of months to years, depending on whether you are an undergraduate, master’s, or PhD candidate. Marcus Beck, a PhD candidate, conducted fundamental research a few years ago, research that didn’t have much to do with his research but returned answers to some niggling questions every student has about the average length of a dissertation.

A software program specifically designed for this purpose helped Beck to access the university’s electronic database to uncover facts on dissertation length.

The above illustration shows how the results of his small study were a little unsurprising. Social sciences and humanities disciplines such as anthropology, politics, and literature had the longest dissertations, with some PhD dissertations comprising 150,000 words or more.Engineering and scientific disciplines, on the other hand, were considerably shorter. PhD-level dissertations generally don’t have a predefined length as they will vary with your research topic. Ask your school about this requirement if you are unsure about it from the start.

Focus more on the quality of content rather than the number of pages.

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

Phrases to Avoid

No matter the style or structure you follow, it is best to keep your language simple. Avoid the use of buzzwords and jargon.

A Word on Stealing Content (Plagiarism)

Very straightforward advice to all students, DO NOT PLAGIARISE. Plagiarism is a serious offence. You will be penalised heavily if you are caught plagiarising. Don’t risk years of hard work, as many students in the past have lost their degrees for plagiarising. Here are some tips to help you make sure you don’t get caught.

- Copying and pasting from an academic source is an unforgivable sin. Rephrasing text retrieved from another source also falls under plagiarism; it’s called paraphrasing. Summarising another’s idea(s) word-to-word, paraphrasing, and copy-pasting are the three primary forms plagiarism can take.

- If you must directly copy full sentences from another source because they fill the bill, always enclose them inside quotation marks and acknowledge the writer’s work with in-text citations.

Are you struggling to find inspiration to get going? Still, trying to figure out where to begin? Is the deadline getting closer? Don’t be overwhelmed! ResearchProspect dissertation writing services have helped thousands of students achieve desired outcomes. Click here to get help from writers holding either a master's or PhD degree from a reputed UK university.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a dissertation include.

A dissertation has main chapters and parts that support them. The main parts are:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Research Methodology

- Your conclusion

Other parts are the abstract, references, appendices etc. We can supply a full dissertation or specific parts of one.

What is the difference between research and a dissertation?

A research paper is a sort of academic writing that consists of the study, source assessment, critical thinking, organisation, and composition, as opposed to a thesis or dissertation, which is a lengthy academic document that often serves as the final project for a university degree.

Can I edit and proofread my dissertation myself?

Of course, you can do proofreading and editing of your dissertation. There are certain rules to follow that have been discussed above. However, finding mistakes in something that you have written yourself can be complicated for some people. It is advisable to take professional help in the matter.

What If I only have difficulty writing a specific chapter of the dissertation?

ResearchProspect ensures customer satisfaction by addressing all relevant issues. We provide dissertation chapter-writing services to students if they need help completing a specific chapter. It could be any chapter from the introduction, literature review, and methodology to the discussion and conclusion.

You May Also Like

Are you looking for intriguing and trending dissertation topics? Get inspired by our list of free dissertation topics on all subjects.

Looking for an easy guide to follow to write your essay? Here is our detailed essay guide explaining how to write an essay and examples and types of an essay.

Learn about the steps required to successfully complete their research project. Make sure to follow these steps in their respective order.

More Interesting Articles

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

What Exactly Is A Dissertation (Or Thesis)?

If you’ve landed on this article, chances are you’ve got a dissertation or thesis project coming up (hopefully it’s not due next week!), and you’re now asking yourself the classic question, “what the #%#%^ is a dissertation?”…

In this post, I’ll break down the basics of exactly what a dissertation is, in plain language. No ivory tower academia.

So, let’s get to the pressing question – what is a dissertation?

A dissertation (or thesis) = a research project

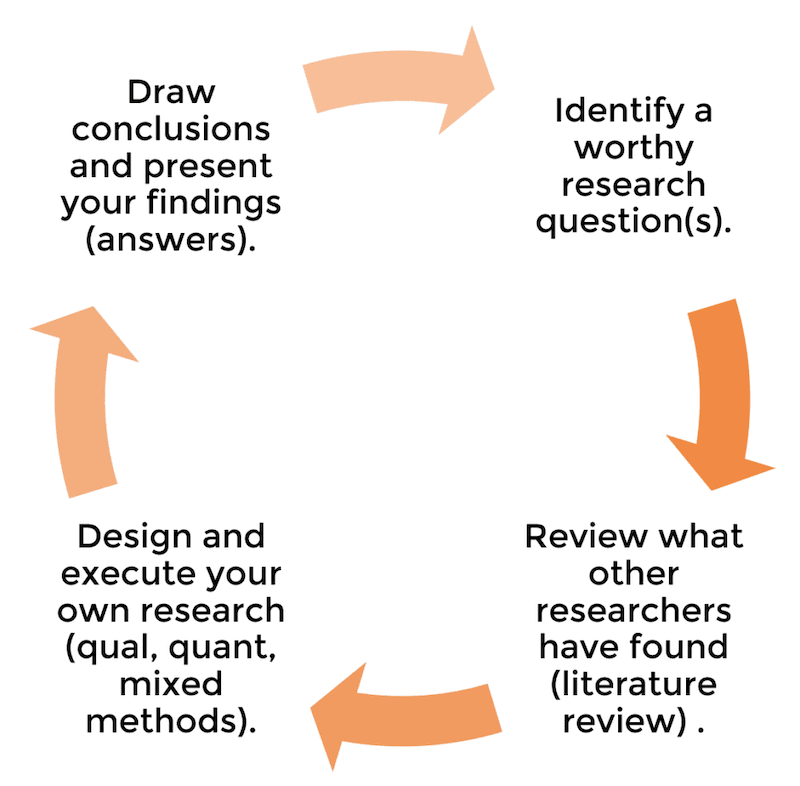

Simply put, a dissertation (or thesis – depending on which country you’re studying in) is a research project . In other words, your task is to ask a research question (or set of questions) and then set about finding the answer(s). Simple enough, right?

Well, the catch is that you’ve got to undertake this research project in an academic fashion , and there’s a wealth of academic language that makes it all (look) rather confusing (thanks, academia). However, at its core, a dissertation is about undertaking research (investigating something). This is really important to understand, because the key skill that your university is trying to develop in you (and will be testing you on) is your ability to undertake research in a well-structured structured, critical and academically rigorous way.

This research-centric focus is significantly different from assignments or essays, where the main concern is whether you can understand and apply the prescribed module theory. I’ll explain some other key differences between dissertations or theses and assignments a bit later in this article, but for now, let’s dig a little deeper into what a dissertation is.

A dissertation (or thesis) is a process.

Okay, so now that you understand that a dissertation is a research project (which is testing your ability to undertake quality research), let’s go a little deeper into what that means in practical terms.

The best way to understand a dissertation is to view it as a process – more specifically a research process (it is a research project, after all). This process involves four essential steps, which I’ll discuss below.

Step 1 – You identify a worthy research question

The very first step of the research process is to find a meaningful research question, or a set of questions. In other words, you need to find a suitable topic for investigation. Since a dissertation is all about research, identifying the key question(s) is the critical first step. Here’s an example of a well-defined research question:

“Which factors cultivate or erode customer trust in UK-based life insurance brokers?”

This clearly defined question sets the direction of the research . From the question alone, you can understand exactly what the outcome of the research might look like – i.e. a set of findings about which factors help brokers develop customer trust, and which factors negatively impact trust.

But how on earth do I find a suitable research question, you ask? Don’t worry about this right now – when you’re ready, you can read our article about finding a dissertation topic . However, right now, the important thing to understand is that the first step in the dissertation process is identifying the key research question(s). Without a clear question, you cannot move forward.

Step 2 – You review the existing research

Once the research question is clearly established, the next step is to review the existing research/literature (both academic and professional/industry) to understand what has already been said with regard to the question. In academic speak, this is called a literature review .

This step is critically important as, in all likelihood, someone else has asked a similar question to yours, and therefore you can build on the work of others . Good academic research is not about reinventing the wheel or starting from scratch – it’s about familiarising yourself with the current state of knowledge, and then using that as your basis for further research.

Simply put, the first step to answering your research question is to look at what other researchers have to say about it. Sometimes this will lead you to change your research question or direction slightly (for example, if the existing research already provides a comprehensive answer). Don’t stress – this is completely acceptable and a normal part of the research process.

Step 3 – You carry out your own research

Once you’ve got a decent understanding of the existing state of knowledge, you will carry out your own research by collecting and analysing the relevant data. This could take to form of primary research (collecting your own fresh data), secondary research (synthesising existing data) or both, depending on the nature of your degree, research question(s) and even your university’s specific requirements.

Exactly what data you collect and how you go about analysing it depends largely on the research question(s) you are asking, but very often you will take either a qualitative approach (e.g. interviews or focus groups) or a quantitative approach (e.g. online surveys). In other words, your research approach can be words-based, numbers-based, or both . Don’t let the terminology scare you and don’t worry about these technical details for now – we’ll explain research methodology in later posts .

Step 4 – You develop answers to your research question(s)

Combining your understanding of the existing research (Step 2) with the findings from your own original research (Step 3), you then (attempt to) answer your original research question (s). The process of asking, investigating and then answering has gone full circle.

Of course, your research won’t always provide rock-solid answers to your original questions, and indeed you might find that your findings spur new questions altogether. Don’t worry – this is completely acceptable and is a natural part of the research process.

So, to recap, a dissertation is best understood as a research process, where you are:

- Ask a meaningful research question(s)

- Carry out the research (both existing research and your own)

- Analyse the results to develop an answer to your original research question(s).

Depending on your specific degree and the way your university designs its coursework, you might be asking yourself “but isn’t this just a longer version of a normal assignment?”. Well, it’s quite possible that your previous assignments required a similar research process, but there are some key differences you need to be aware of, which I’ll explain next.

Same same, but different…

While there are, naturally, similarities between dissertations/theses and assignments, its important to understand the differences so that you approach your dissertation with the right mindset and focus your energy on the right things. Here, I’ll discuss four ways in which writing a dissertation differs substantially from assignments and essays, and why this matters.

Difference #1 – You must decide (and live with) the direction.

Unlike assignments or essays, where the general topic is determined for you, for your dissertation, you will (typically) be the one who decides on your research questions and overall direction. This means that you will need to:

- Find a suitable research question (or set of questions)

- Justify why its worth investigating (in the form of a research proposal )

- Find all the relevant existing research and familiarise yourself with the theory

This is very different from assignments, where the theory is given to you on a platter, and the direction is largely pre-defined. Therefore, before you start the dissertation process, you need to understand the basics of academic research, how to find a suitable research topic and how to source the relevant literature.

Difference #2 – It’s a long project, and you’re on your own.

A dissertation is a long journey, at least compared to assignments. Typically, you will spend 3 – 6 months writing around 15,000 – 25,000 words (for Masters-level, much more for PhD) on just one subject. Therefore, successfully completing your dissertation requires a substantial amount of stamina .

To make it even more challenging, your classmates will not be researching the same thing as you are, so you have limited support, other than your supervisor (who may be very busy). This can make it quite a lonely journey . Therefore, you need a lot of self-discipline and self-direction in order to see it through to the end. You should also try to build a support network of people who can help you through the process (perhaps alumni, faculty or a private coach ).

Difference #3 – They’re testing research skills.

We touched on this earlier. Unlike assignments or essays, where the markers are assessing your ability to understand and apply the theories, models and frameworks that they provide you with, your dissertation will be is assessing your ability to undertake high-quality research in an academically rigorous manner.

Of course, your ability to understand the relevant theory (i.e. within your literature review) is still very important, but this is only one piece of the research skills puzzle. You need to demonstrate the full spectrum of research skills.

It’s important to note that your research does not need to be ground-breaking, revolutionary or world-changing – that is not what the markers are assessing. They are assessing whether you can apply well-established research principles and skills to a worthwhile topic of enquiry. Don’t feel like you need to solve the world’s major problems. It’s simply not going to happen (you’re a first-time researcher, after all) – and doesn’t need to happen in order to earn good marks.

Difference #4 – Your focus needs to be narrow and deep.

In your assignments, you were likely encouraged to take a broad, interconnected, high-level view of the theory and connect as many different ideas and concepts as possible. In your dissertation, however, you typically need to narrow your focus and go deep into one particular topic. Think about the research question we looked at earlier:

The focus is intentionally very narrow – specifically the focus is on:

- The UK only – no other countries are being considered.

- Life insurance brokers only – not financial services, not vehicle insurance, not medical insurance, etc.

- Customer trust only – not reputation, not customer loyalty, not employee trust, supplier trust, etc.

By keeping the focus narrow, you enable yourself to deeply probe whichever topic you choose – and this depth is essential for earning good marks. Importantly, ringfencing your focus doesn’t mean ignoring the connections to other topics – you should still acknowledge all the linkages, but don’t get distracted – stay focused on the research question(s).

So, as you can see, a dissertation is more than just an extended assignment or essay. It’s a unique research project that you (and only you) must lead from start to finish. The good news is that, if done right, completing your dissertation will equip you with strong research skills, which you will most certainly use in the future, regardless of whether you follow an academic or professional path.

Wrapping up

Hopefully in this post, I’ve answered your key question, “what is a dissertation?”, at least at a big picture-level. To recap on the key points:

- A dissertation is simply a structured research project .

- It’s useful to view a dissertation as a process involving asking a question, undertaking research and then answering that question.

- First and foremost, your marker(s) will be assessing your research skills , so its essential that you focus on producing a rigorous, academically sound piece of work (as opposed to changing the world or making a scientific breakthrough).

- While there are similarities, a dissertation is different from assignments and essays in multiple ways. It’s important to understand these differences if you want to produce a quality dissertation.

In this post, I’ve gently touched on some of the intricacies of the dissertation, including research questions, data types and research methodologies. Be sure to check out the Grad Coach Blog for more detailed discussion of these areas.

36 Comments

Hello Derek

Yes, I struggle with literature review and am highly frustrated (with myself).

Thank you for the guide that you have sent, especially the apps. I am working through the guide and busy with the implementation of it.

Hope to hear from you again!

Regards Micheal

Great to hear that, Michael. All the best with your research!

Very useful and clear information.

Thank you. That was quite something to move forward with. Despite the fact that I was lost. I will now be able to do something with the information given.