Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical considerations for care of children and adults with confirmed COVID-19

‹ View Table of Contents

- The clinical presentation of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic to critical illness.

- An infected person can transmit SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, before the onset of symptoms. Symptoms can change over the course of illness and can progress in severity.

- Uncommon presentations of COVID-19 can occur, might vary by the age of the patient, and are a challenge to recognize.

- In adults, age is the strongest risk factor for severe COVID-19. The risk of severe COVID-19 increases with increasing age especially for persons over 65 years and with increasing number of certain underlying medical conditions .

Incubation Period

Data suggest that incubation periods may differ by SARS-CoV-2 variant. Meta-analyses of studies published in 2020 identified a pooled mean incubation period of 6.5 days from exposure to symptom onset. (1) A study conducted during high levels of Delta variant transmission reported an incubation period of 4.3 days, (2) and studies performed during high levels of Omicron variant transmission reported a median incubation period of 3–4 days. (3,4)

Presentation

People with COVID-19 may be asymptomatic or may commonly experience one or more of the following symptoms (not a comprehensive list) (5) :

- Fever or chills

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Myalgia (Muscle or body aches)

- New loss of taste or smell

- Sore throat

- Congestion or runny nose

- Nausea or vomiting

The clinical presentation of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic to severe illness, and COVID-19 symptoms may change over the course of illness. COVID-19 symptoms can be difficult to differentiate from and can overlap with other viral respiratory illnesses such as influenza(flu) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) . Because symptoms may progress quickly, close follow-up is needed, especially for:

- older adults

- people with disabilities

- people with immunocompromising conditions, and

- people with medical conditions that place them at greater risk for severe illness or death.

The NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines group SARS-CoV-2 infection into five categories based on severity of illness:

- Asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infection : people who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 using a virologic test (i.e., a nucleic acid amplification test [NAAT] or an antigen test) but who have no symptoms that are consistent with COVID-19.

- Mild illness : people who may have any of the various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 but who do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging.

- Moderate illness : people who have evidence of lower respiratory disease during clinical assessment or imaging and who have an oxygen saturation (SpO 2 ) ≥94% on room air at sea level.

- Severe illness : people who have oxygen saturation <94% on room air at sea level, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO 2 /FiO 2 ) <300 mm Hg, a respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrates >50%

- Critical illness : people who have respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction.

Asymptomatic and presymptomatic presentation

Studies have documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in people who never develop symptoms (asymptomatic presentation) and in people who are asymptomatic when tested but develop symptoms later (presymptomatic presentation). ( 6,7 ) It is unclear what percentage of people who initially appear asymptomatic progress to clinical disease. Multiple publications have reported cases of people with abnormalities on chest imaging that are consistent with COVID-19 very early in the course of illness, even before the onset of symptoms or a positive COVID-19 test. (9)

Radiographic Considerations and Findings

Chest radiographs of patients with severe COVID-19 may demonstrate bilateral air-space consolidation. (23) Chest computed tomography (CT) images from patients with COVID-19 may demonstrate bilateral, peripheral ground glass opacities and consolidation. (24,25) Less common CT findings can include intra- or interlobular septal thickening with ground glass opacities (hazy opacity) or focal and rounded areas of ground glass opacity surrounded by a ring or arc of denser consolidation (reverse halo sign). (24)

Multiple studies suggest that abnormalities on CT or chest radiograph may be present in people who are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or before RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal specimens. (25)

Common COVID-19 symptoms

Fever, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, headache, and myalgia are among the most commonly reported symptoms in people with COVID-19. (5) Some people with COVID-19 have gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, sometimes prior to having fever or lower respiratory tract signs and symptoms. (10) Loss of smell and taste can occur, although these symptoms are reported to be less common since Omicron began circulating, as compared to earlier during the COVID-19 pandemic. (11,19-21) People can experience SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic or symptomatic), even if they are up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines or were previously infected. (8)

Several studies have reported ocular symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including redness, tearing, dry eye or foreign body sensation, discharge or increased secretions, and eye itching or pain. (13)

A wide range of dermatologic manifestations have been associated with COVID-19; timing of skin manifestations in relation to other COVID-19 symptoms and signs is variable. (14) Some skin manifestations may be associated with increased disease severity. (15) Images of cutaneous findings in COVID-19 are available from the American Academy of Dermatology .

Uncommon COVID-19 symptoms

Less common presentations of COVID-19 can occur. Older adults may present with different symptoms than children and younger adults. Some older adults can experience SARS-CoV-2 infection accompanied by delirium, falls, reduced mobility or generalized weakness, and glycemic changes. ( 12)

Transmission

People infected with SARS-CoV-2 can transmit the virus even if they are asymptomatic or presymptomatic. ( 16) Peak transmissibility appears to occur early during the infectious period (prior to symptom onset until a few days after), but infected persons can shed infectious virus up to 10 days following infection. (22 ) Both vaccinated and unvaccinated people can transmit SARS-CoV-2. ( 17,18) Clinicians should consider encouraging all people to take the following prevention actions to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission:

- stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines,

- test for COVID-19 when symptomatic or exposed to someone with COVID-19, as recommended by CDC,

- wear a high-quality mask when recommended,

- avoiding contact with individuals who have suspected or confirmed COVID-19,

- improving ventilation when possible,

- and follow basic health and hand hygiene guidance .

Clinicians should also recommend that people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2, follow CDC guidelines for isolation.

Table of Contents

- › Clinical Presentation

- Clinical Progression, Management, and Treatment

- Special Clinical Considerations

- Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Evans SJ, et al. Factors associated with deaths due to COVID-19 versus other causes: population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Reg Health Eur. Jul 2021;6:100109. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100109

- Kim L, Garg S, O'Halloran A, et al. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-hospital Mortality among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the U.S. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis. Jul 16 2020;doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1012

- Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, et al. Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020-March 2021. Preventing chronic disease. Jul 1 2021;18:E66. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210123

- Ko JY, Danielson ML, Town M, et al. Risk Factors for COVID-19-associated hospitalization: COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Clin Infect Dis. Sep 18 2020;doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1419

- Wortham JM, Lee JT, Althomsons S, et al. Characteristics of Persons Who Died with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-May 18, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jul 17 2020;69(28):923-929. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6928e1

- Yang X, Zhang J, Chen S, et al. Demographic Disparities in Clinical Outcomes of COVID-19: Data From a Statewide Cohort in South Carolina. Open Forum Infect Dis. Sep 2021;8(9):ofab428. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab428

- Rader B.; Gertz AL, D.; Gilmer, M.; Wronski, L.; Astley, C.; Sewalk, K.; Varrelman, T.; Cohen, J.; Parikh, R.; Reese, H.; Reed, C.; Brownstein J. Use of At-Home COVID-19 Tests — United States, August 23, 2021–March 12, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. April 1, 2022;71(13):489–494. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7113e1

- Pingali C, Meghani M, Razzaghi H, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Insured Persons Aged >/=16 Years, by Race/Ethnicity and Other Selected Characteristics - Eight Integrated Health Care Organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-May 15, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jul 16 2021;70(28):985-990. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7028a1

- Wiltz JL, Feehan AK, Molinari NM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Receipt of Medications for Treatment of COVID-19 - United States, March 2020-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 21 2022;71(3):96-102. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7103e1

- Murthy NC, Zell E, Fast HE, et al. Disparities in First Dose COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage among Children 5-11 Years of Age, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. May 2022;28(5):986-989. doi:10.3201/eid2805.220166

- Saelee R, Zell E, Murthy BP, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Between Urban and Rural Counties - United States, December 14, 2020-January 31, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 4 2022;71(9):335-340. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7109a2

- Burki TK. The role of antiviral treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. Feb 2022;10(2):e18. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00011-X

- Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of Covid-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. N Engl J Med. Feb 10 2022;386(6):509-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2116044

- Bai Y, Du Z, Wang L, et al. Public Health Impact of Paxlovid as Treatment for COVID-19, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2024;30(2) (In eng). DOI: 10.3201/eid3002.230835.

- Najjar-Debbiny R, Gronich N, Weber G, et al. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in Reducing Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Mortality in High-Risk Patients. Clin Infect Dis 2023;76(3):e342-e349. (In eng). DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciac443.

- Shah MM, Joyce B, Plumb ID, et al. Paxlovid Associated with Decreased Hospitalization Rate Among Adults with COVID-19 - United States, April-September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71(48):1531-1537. (In eng). DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7148e2.

- Dryden-Peterson S, Kim A, Kim AY, et al. Nirmatrelvir Plus Ritonavir for Early COVID-19 in a Large U.S. Health System : A Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2023;176(1):77-84. (In eng). DOI: 10.7326/m22-2141.

- Lewnard JA, McLaughlin JM, Malden D, et al. Effectiveness of nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in preventing hospital admissions and deaths in people with COVID-19: a cohort study in a large US health-care system. Lancet Infect Dis 2023;23(7):806-815. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/s1473-3099(23)00118-4.

- Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022;386(15):1397-1408. (In eng). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542.

- Arbel R, Wolff Sagy Y, Hoshen M, et al. Nirmatrelvir Use and Severe Covid-19 Outcomes during the Omicron Surge. N Engl J Med 2022;387(9):790-798. (In eng). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204919.

- Skarbinski J, Wood M, Chervo T, et al. Risk of severe clinical outcomes among persons with SARS-CoV-2 infection with differing levels of vaccination during widespread Omicron (B.1.1.529) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variant circulation in Northern California: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022;12:100297. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lan.

- Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial Bias in Pulse Oximetry Measurement. N Engl J Med. Dec 17 2020;383(25):2477-2478. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2029240

- Jordan TB, Meyers CL, Schrading WA, Donnelly JP. The utility of iPhone oximetry apps: A comparison with standard pulse oximetry measurement in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. May 2020;38(5):925-928. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.07.020

- Iuliano AD, Brunkard JM, Boehmer TK, et al. Trends in Disease Severity and Health Care Utilization During the Early Omicron Variant Period Compared with Previous SARS-CoV-2 High Transmission Periods - United States, December 2020-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 28 2022;71(4):146-152. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e4

- Taylor CA, Whitaker M, Anglin O, et al. COVID-19-Associated Hospitalizations Among Adults During SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Variant Predominance, by Race/Ethnicity and Vaccination Status - COVID-NET, 14 States, July 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 25 2022;71(12):466-473. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7112e2

- Johnson AG, Amin AB, Ali AR, et al. COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates Among Unvaccinated and Fully Vaccinated Adults with and Without Booster Doses During Periods of Delta and Omicron Variant Emergence - 25 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4-December 25, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 28 2022;71(4):132-138. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e2

- Danza P, Koo TH, Haddix M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Hospitalization Among Adults Aged >/=18 Years, by Vaccination Status, Before and During SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant Predominance - Los Angeles County, California, November 7, 2021-January 8, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Feb 4 2022;71(5):177-181. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7105e1

To receive email updates about COVID-19, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

1.2 Disease presentation and clinical course

1.2.1 clinical features.

The incubation period ranges from a few hours to 5 days.

Depending on the strain involved, 60 to 75% of infections remain clinically unapparent. Among symptomatic patients, at least 25 to 30% have severe disease but this proportion may be higher.

The initial manifestation is diarrhoea. Stools quickly lose their faecal content, taking on a characteristic “rice water” appearance and contain no blood.

Symptoms can range from simple watery diarrhoea to massive watery diarrhoea with losses of up to 500 to 1000 ml/hour in severe disease a Citation a. After ingestion, vibrios pass through the gastric acid barrier and adhere to the mucosa of the upper small intestine without penetrating it. They secrete cholera toxin, which binds to mucosal receptors and is transported into the cell where it activates the enzyme adenylate cyclase, increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). As a result, a shift in cell membrane ion transport occurs, with a net increase in ion concentration (mainly chloride and sodium) within the intestinal lumen. Water is drawn into the lumen in response to the increased ion concentration leading to the voluminous watery diarrhoea characteristic of cholera. . The total stool output over 3 to 4 days of illness can reach 500 ml/kg.

Vomiting is often present, and is typically colourless without bile. Abdominal discomfort may be present but severe cramping is not a feature. There is usually no fever; low-grade fever is possible, but as cholera does not induce a systemic inflammatory response, temperatures above 38 °C (axillary) should prompt a search for another cause of fever.

Continuing diarrhoea and vomiting cause volume depletion and further clinical signs and symptoms are those of increasing dehydration:

- Patients present with sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes and decreased skin turgor.

- The pulse becomes more rapid, then weak, and eventually non-palpable.

- Blood pressure drops progressively.

- Patients show deterioration in the level of consciousness (lethargy).

- Patients may arrive unconscious, in hypovolaemic shock.

In severe disease, cardiovascular collapse and death can occur within 12 to 72 hours without therapy [1] Citation 1. World Health Organization. Manual for the laboratory identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial pathogens of public health importance in the developing world. WHO/CDS/CSR/RMD/2003.6. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/68554/WHO_CDS_CSR_RMD_2003.6.pdf?sequence=1 .

The large volume watery stools containing sodium, chloride, bicarbonates, and potassium contribute to acidosis and hypokalaemia. Bicarbonate loss (40 mmol/litre of stool) and lactate production are responsible for a nearly universal metabolic acidosis in patients with severe dehydration. This acidosis is quickly corrected with appropriate rehydration fluid. Potassium loss (20 mmol/litre of stool) also occurs and some degree of hypokalaemia is usually present. Clinical and biochemical evidence of hypokalaemia may be more apparent after 24 hours of rehydration therapy, particularly if ORS has not been used in rehydration.

1.2.2 Clinical diagnosis

At the beginning of the outbreak, laboratory investigations are performed in a group of patients presenting with compatible clinical signs of cholera, to confirm whether Vibrio cholerae is the causative pathogen and determine the sensitivity of the strain to antibiotics.

Once the cholera outbreak has been bacteriologically confirmed, diagnosis of subsequent cases relies on clinical case definition b Citation b. Cholera surveillance and early warning systems rely also on the standard clinical case definition for a presumptive diagnosis of cholera. and clinical assessment only. A sudden onset of severe watery diarrhoea during a cholera epidemic is highly predictive of cholera.

1.2.3 Prognosis and case fatality rate

Without treatment, the prognosis of severe cholera is poor, with up to a 50% mortality rate. In contrast, the case fatality rate in cholera cases treated in a well-functioning treatment structure is typically 1% or less.

- (a) After ingestion, vibrios pass through the gastric acid barrier and adhere to the mucosa of the upper small intestine without penetrating it. They secrete cholera toxin, which binds to mucosal receptors and is transported into the cell where it activates the enzyme adenylate cyclase, increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). As a result, a shift in cell membrane ion transport occurs, with a net increase in ion concentration (mainly chloride and sodium) within the intestinal lumen. Water is drawn into the lumen in response to the increased ion concentration leading to the voluminous watery diarrhoea characteristic of cholera.

- (b) Cholera surveillance and early warning systems rely also on the standard clinical case definition for a presumptive diagnosis of cholera.

- 1. World Health Organization. Manual for the laboratory identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial pathogens of public health importance in the developing world. WHO/CDS/CSR/RMD/2003.6. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/68554/WHO_CDS_CSR_RMD_2003.6.pdf?sequence=1

Wound Infection Clinical Presentation

- Author: Hemant Singhal, MD, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FRCS(Edin), FRCSC; Chief Editor: John Geibel, MD, MSc, DSc, AGAF more...

- Sections Wound Infection

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology

- Definition and Classification

- History and Physical Examination

- Laboratory Studies

- Ultrasonography

- Approach Considerations

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Risk Assessment

- Perioperative Recommendations

- Surgical Care

- APSIC Guidelines for Prevention of Surgical-Site Infection

- WHO Guidelines on Surgical-Site Infection

- CDC Guidelines for Prevention of Surgical-Site Infection

- IDSA Guidelines on Surgical-Site Infection

- Medication Summary

- Antibiotics

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

Surgical-site infection (SSI) is a difficult term to define accurately because it has a wide spectrum of possible clinical features.

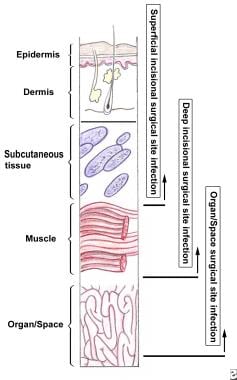

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has defined SSI to standardize data collection for the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) program. [ 8 , 16 ] SSIs are classified into incisional SSIs, which can be superficial or deep, and organ/space SSIs, which affect the rest of the body other than the body wall layers (see the image below). These classifications are defined as follows:

- Superficial incisional SSI - Infection involves only skin and subcutaneous tissue of incision

- Deep incisional SSI - Infection involves deep tissues, such as fascial and muscle layers; this also includes infection involving both superficial and deep incision sites and organ/space SSI draining through incision

- Organ/space SSI - Infection involves any part of the anatomy in organs and spaces other than the incision, which was opened or manipulated during operation

Superficial incisional SSI is more common than deep incisional SSI and organ/space SSI. Superficial incisional SSI accounts for more than half of all SSIs for all categories of surgery. The postoperative length of stay is longer for patients with SSI, even when adjusted for other factors influencing length of stay.

A report by the NNIS program [ 17 ] cited particular clinical findings as characteristic of the different types of SSI.

Superficial incisional SSI is characterized by the following:

- Occurs within 30 days after the operation

- Involves only the skin or subcutaneous tissue

- Includes at least one of the following: (a) purulent drainage is present (culture documentation not required); (b) organisms are isolated from fluid/tissue of the superficial incision; (c) at least one sign of inflammation (eg, pain or tenderness, induration, erythema, local warmth of the wound) is present; (d) the wound is deliberately opened by the surgeon; (e) the surgeon or clinician declares the wound infected

- Note: A wound is not considered a superficial incisional SSI if a stitch abscess is present; if the infection is at an episiotomy, a circumcision site, or a burn wound; or if the SSI extends into fascia or muscle

Deep incisional SSI is characterized by the following:

- Occurs within 30 days of the operation or within 1 year if an implant is present

- Involves deep soft tissues (eg, fascia and/or muscle) of the incision

- Includes at least one of the following: (a) purulent drainage is present from the deep incision but without organ/space involvement; (b) fascial dehiscence or fascia is deliberately separated by the surgeon because of signs of inflammation; (c) a deep abscess is identified by direct examination or during reoperation, by histopathology, or by radiologic examination; (d) the surgeon or clinician declares that a deep incisional infection is present

Organ/space SSI is characterized by the following:

- Involves anatomic structures not opened or manipulated during the operation

- Includes at least one of the following: (a) purulent drainage is present from a drain placed by a stab wound into the organ/space; (b) organisms are isolated from the organ/space by aseptic culturing technique; (c) an abscess in the organ/space is identified by direct examination, during reoperation, or by histopathologic or radiologic examination; (d) a diagnosis of organ/space SSI is made by the surgeon or clinician

Examples of wound infections are shown in the images below.

Breasted D. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus . Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1930.

Bryan PW. The Papyrus Ebers . London/Washington DC: Government Printing Office; 1883.

Cohen IK. A Brief History of Wound Healing . Yardley, PA: Oxford Clinical Communications; 1998.

Lister J. On a new method of treating compound fractures. Lancet . 1867. 1:326-9, 387-9, 507-9.

Qvist G. Hunterian Oration, 1979. Some controversial aspects of John Hunter's life and work. Ann R Coll Surg Engl . 1979 Jul. 61 (4):309-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Helling TS, Daon E. In Flanders fields: the Great War, Antoine Depage, and the resurgence of débridement. Ann Surg . 1998 Aug. 228 (2):173-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Krizek TJ, Robson MC. Evolution of quantitative bacteriology in wound management. Am J Surg . 1975 Nov. 130 (5):579-84. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) report, data summary from October 1986-April 1996, issued May 1996. A report from the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System. Am J Infect Control . 1996 Oct. 24 (5):380-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Hsiao CH, Chuang CC, Tan HY, Ma DH, Lin KK, Chang CJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ocular infection: a 10-year hospital-based study. Ophthalmology . 2012 Mar. 119 (3):522-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Cruse PJ, Foord R. The epidemiology of wound infection. A 10-year prospective study of 62,939 wounds. Surg Clin North Am . 1980 Feb. 60 (1):27-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev . 1993 Oct. 6 (4):428-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Mayon-White RT, Ducel G, Kereselidze T, Tikomirov E. An international survey of the prevalence of hospital-acquired infection. J Hosp Infect . 1988 Feb. 11 Suppl A:43-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Nosocomial Infection National Surveillance Service (NINSS). Surgical site infection in English hospitals: a national surveillance and quality improvement program. Public Health Laboratory Service . 2002.

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 1999 Apr. 20 (4):250-78; quiz 279-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 1999 Nov. 20 (11):725-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Di Leo A, Piffer S, Ricci F, Manzi A, Poggi E, Porretto V, et al. Surgical site infections in an Italian surgical ward: a prospective study. Surg Infect (Larchmt) . 2009 Dec. 10 (6):533-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 to June 2002, issued August 2002. Am J Infect Control . 2002 Dec. 30 (8):458-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Mahmoud NN, Turpin RS, Yang G, Saunders WB. Impact of surgical site infections on length of stay and costs in selected colorectal procedures. Surg Infect (Larchmt) . 2009 Dec. 10 (6):539-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Haley RW, Schaberg DR, Crossley KB, Von Allmen SD, McGowan JE Jr. Extra charges and prolongation of stay attributable to nosocomial infections: a prospective interhospital comparison. Am J Med . 1981 Jan. 70 (1):51-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Eagye KJ, Kim A, Laohavaleeson S, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. Surgical site infections: does inadequate antibiotic therapy affect patient outcomes?. Surg Infect (Larchmt) . 2009 Aug. 10 (4):323-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

[Guideline] Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis . 2014 Jul 15. 59 (2):147-59. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] . [Full Text] .

[Guideline] Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg . 2017 Aug 1. 152 (8):784-791. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] . [Full Text] .

[Guideline] Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2nd ed. World Health Organization. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-guidelines-for-the-prevention-of-surgical-site-infection-2nd-ed . January 3, 2018; Accessed: March 16, 2023.

[Guideline] Ling ML, Apisarnthanarak A, Abbas A, Morikane K, Lee KY, Warrier A, et al. APSIC guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control . 2019. 8:174. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] . [Full Text] .

Burke JF. The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery . 1961 Jul. 50:161-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Barchitta M, Matranga D, Quattrocchi A, Bellocchi P, Ruffino M, Basile G, et al. Prevalence of surgical site infections before and after the implementation of a multimodal infection control programme. J Antimicrob Chemother . 2012 Mar. 67 (3):749-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Gupta R, Sinnett D, Carpenter R, Preece PE, Royle GT. Antibiotic prophylaxis for post-operative wound infection in clean elective breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol . 2000 Jun. 26 (4):363-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Platt R, Zucker JR, Zaleznik DF, Hopkins CC, Dellinger EP, Karchmer AW, et al. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis and wound infection following breast surgery. J Antimicrob Chemother . 1993 Feb. 31 Suppl B:43-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Woodfield JC, Beshay N, van Rij AM. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials assessing the prophylactic use of ceftriaxone. A study of wound, chest, and urinary infections. World J Surg . 2009 Dec. 33 (12):2538-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Woods RK, Dellinger EP. Current guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis of surgical wounds. Am Fam Physician . 1998 Jun. 57 (11):2731-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Culver DH, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. Surgical wound infection rates by wound class, operative procedure, and patient risk index. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Am J Med . 1991 Sep 16. 91 (3B):152S-157S. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

American Society of Anesthesiologists. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology . 1963. 24:111.

Pearson ML. Guideline for prevention of intravascular device-related infections. Part I. Intravascular device-related infections: an overview. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control . 1996 Aug. 24 (4):262-77. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Mermel LA, Farr BM, Sherertz RJ, Raad II, O'Grady N, Harris JS, et al. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis . 2001 May 1. 32 (9):1249-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Dettenkofer M, Wilson C, Gratwohl A, Schmoor C, Bertz H, Frei R, et al. Skin disinfection with octenidine dihydrochloride for central venous catheter site care: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect . 2010 Jun. 16 (6):600-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Latham R, Lancaster AD, Covington JF, Pirolo JS, Thomas CS Jr. The association of diabetes and glucose control with surgical-site infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2001 Oct. 22 (10):607-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med . 1996 May 9. 334 (19):1209-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Belda FJ, Aguilera L, García de la Asunción J, Alberti J, Vicente R, Ferrándiz L, et al. Supplemental perioperative oxygen and the risk of surgical wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA . 2005 Oct 26. 294 (16):2035-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

- Wound infection due to disturbed coagulopathy. This patient has a pacemaker (visible below right clavicular space) and had previous cardiac surgery (median sternotomy wound visible) for a rheumatic mitral valve disorder, which was replaced. The patient was taking anticoagulants preoperatively. Despite converting to low-molecular weight subcutaneous heparin treatment and establishing normal coagulation studies, she developed a postoperative hematoma with subsequent wound infection. She had the hematoma evacuated and was administered antibiotic treatment as guided by microbiological results, and the wound was left to heal by secondary intention.

- Abscess secondary to a subclavian line.

- Definitions of surgical site infection (SSI).

- Factors that affect surgical wound healing.

- Large ulceration in a tattoo. A 33-year-old man presented with a superficial ulceration about 4 weeks after a red tattoo on his forearm. Microbial swabs remained negative. His medical history was uneventful and he was in good general health. No reason for this uncommon reaction could be identified. Image courtesy of the National Institutes of Health.

- Table 1. Pathogens Commonly Associated with Wound Infections and Frequency of Occurrence [ 8 ]

- Table 2: Surgical Wound Classification and Subsequent Risk of Infection (If No Antibiotics Used) [ 8 , 10 ]

- Table 3. Recommendations for Prophylactic Antibiotics as Indicated by Probable Infective Microorganism Involved [ 8 , 30 ]

- Table 4. Predictive Percentage of SSI Occurrence by Wound Type and Risk Index* [ 31 ]

- Table 5. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Classification of Physical Status [ 32 ]

- Table 6. Data Support Recommendations

|

|

| 20 |

Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 14 |

Enterococci | 12 |

| 8 |

| 8 |

species | 7 |

| 3 |

| 3 |

Other streptococci | 3 |

| 3 |

Group D streptococci | 2 |

Other gram-positive aerobes | 2 |

| 2 |

|

|

|

Clean (Class I) | Uninfected operative wound No acute inflammation Closed primarily Respiratory, gastrointestinal, biliary, and urinary tracts not entered No break in aseptic technique Closed drainage used if necessary | < 2 |

Clean-contaminated (Class II) | Elective entry into respiratory, biliary, gastrointestinal, urinary tracts and with minimal spillage No evidence of infection or major break in aseptic technique Example: appendectomy | < 10 |

Contaminated (Class III) | Nonpurulent inflammation present Gross spillage from gastrointestinal tract Penetrating traumatic wounds < 4 hours Major break in aseptic technique | About 20 |

Dirty-infected (Class IV) | Purulent inflammation present Preoperative perforation of viscera Penetrating traumatic wounds >4 hours | About 40 |

|

|

|

Orthopedic surgery (including prosthesis insertion), cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, breast surgery, noncardiac thoracic procedures | , coagulase-negative staphylococci | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

Appendectomy, biliary procedures | Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

Colorectal surgery | Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes | Cefotetan 1-2 g or cefoxitin 1-2 g plus oral neomycin 1 g and oral erythromycin 1 g (start 19 h preoperatively for 3 doses) |

Gastroduodenal surgery | Gram-negative bacilli and streptococci | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

Vascular surgery | , gram-negative bacilli | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

Head and neck surgery | , streptococci, anaerobes and streptococci present in an oropharyngeal approach | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

Obstetric and gynecological procedures | Gram-negative bacilli, enterococci, anaerobes, group B streptococci | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

Urology procedures | Gram-negative bacilli | Cefazolin 1-2 g |

|

|

0 | 1.5 |

1 | 2.9 |

2 | 6.8 |

3 | 13.0 |

*Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) recommendations (partial) for the prevention of SSIs, April 1999 (non–drug based) | |

|

|

1 | Normal healthy patient |

2 | Patient with mild systemic disease |

3 | Patient with a severe systemic disease that limits activity but is not incapacitating |

4 | Patient with an incapacitating systemic disease that is a constant threat to life |

5 | Moribund patient not expected to survive 24 hours with or without operation |

|

|

Category IA | Well designed, experimental, strong; recommended (category I*) clinical or epidemiological best practice; should be studies; adapted by all practices |

Category IB | Some experimental, fairly strong; recommended (category II*) clinical or epidemiological best practice; should be studies and theoretical grounds; adapted by all practices |

Category II | Fewer scientific supporting data; limited to specific nosocomial (category III*) problems |

No recommendation | Insufficient scientific personnel judgment for use (category III*) supporting data |

*Previous nomenclature of 1992 CDC guidelines | |

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Hemant Singhal, MD, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FRCS(Edin), FRCSC Consultant Breast Surgeon, Clementine Churchill Hospital; Consultant Breast Surgeon, Harley Street Breast Clinic, UK Hemant Singhal, MD, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FRCS(Edin), FRCSC is a member of the following medical societies: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada , Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Kanchan Kaur, MBBS, MS (GenSurg), MRCSEd Consulting Breast and Oncoplastic Surgeon, Medanta, The Medicity, India Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

John Geibel, MD, MSc, DSc, AGAF Vice Chair and Professor, Department of Surgery, Section of Gastrointestinal Medicine, Professor, Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale University School of Medicine; Director of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Yale-New Haven Hospital; American Gastroenterological Association Fellow; Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine John Geibel, MD, MSc, DSc, AGAF is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association , American Physiological Society , American Society of Nephrology , Association for Academic Surgery , International Society of Nephrology , New York Academy of Sciences , Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Amy L Friedman, MD Professor of Surgery, Director of Transplantation, State University of New York Upstate Medical University Amy L Friedman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons , American Medical Association , American Medical Women's Association , American Society for Artificial Internal Organs , American Society of Transplant Surgeons , American Society of Transplantation , Association for Academic Surgery , Association of Women Surgeons , International College of Surgeons , International Liver Transplantation Society , New York Academy of Sciences , Pennsylvania Medical Society , Philadelphia County Medical Society , Society of Critical Care Medicine , Transplantation Society Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Brian J Daley, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCP, CNSC Professor and Program Director, Department of Surgery, Chief, Division of Trauma and Critical Care, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Medicine Brian J Daley, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCP, CNSC is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Surgery of Trauma , Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma , Southern Surgical Association , American College of Chest Physicians , American College of Surgeons , American Medical Association , Association for Academic Surgery , Association for Surgical Education , Shock Society , Society of Critical Care Medicine , Southeastern Surgical Congress , Tennessee Medical Association Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Charles Zammit, MD Senior Specialist Registrar, Department of Surgery, Breast Unit Charing Cross Hospital of London, UK

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

What would you like to print?

- Print this section

- Print the entire contents of

- Print the entire contents of article

- Pressure Injuries (Pressure Ulcers) and Wound Care

- Thermal Burns

- Wound Closure Technique

- Human Bites

- Incision Placement

- Erbium-YAG Cutaneous Laser Resurfacing

- The Management of Anxiety in Primary Care

- AAD Updates Acne Management Guidelines

- Will Imaging Improve Migraine Diagnosis and Management?

- Drug Interaction Checker

- Pill Identifier

- Calculators

- 2001/s/viewarticle/979497Journal Article Journal Article Mobile Wound Management System Application

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present...

How to present clinical cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Ademola Olaitan , medical student 1 ,

- Oluwakemi Okunade , final year medical student 1 ,

- Jonathan Corne , consultant physician 2

- 1 University of Nottingham

- 2 Nottingham University Hospitals

Presenting a patient is an essential skill that is rarely taught

Clinical presenting is the language that doctors use to communicate with each other every day of their working lives. Effective communication between doctors is crucial, considering the collaborative nature of medicine. As a medical student and later as a doctor you will be expected to present cases to peers and senior colleagues. This may be in the setting of handovers, referring a patient to another specialty, or requesting an opinion on a patient.

A well delivered case presentation will facilitate patient care, act a stimulus for timely intervention, and help identify individual and group learning needs. 1 Case presentations are also used as a tool for assessing clinical competencies at undergraduate and postgraduate level.

Medical students are taught how to take histories, examine, and communicate effectively with patients. However, we are expected to learn how to present effectively by observation, trial, and error.

Principles of presentation

Remember that the purpose of the case presentation is to convey your diagnostic reasoning to the listener. By the end of your presentation the examiner should have a clear view of the patient’s condition. Your presentation should include all the facts required to formulate a management plan.

There are no hard and fast rules for a perfect presentation, rather the content of each presentation should be determined by the case, the context, and the audience. For example, presenting a newly admitted patient with complex social issues on a medical ward round will be very different from presenting a patient with a perforated duodenal ulcer who is in need of an emergency laparotomy.

Whether you’re presenting on a busy ward round or during an objective structured clinical …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

- Celiac Disease

Definition and Clinical Manifestations

- Pathogenesis

- Epidemiology

- Special Issues (FAQs)

- Associated Disorder

Gluten is the term for a protein component of wheat and similar proteins found in rye and barley. In people with celiac disease, the body mounts an immune reaction to gluten. The immune system goes on high alert. It attacks and damages the small intestine. The nature of this immune response is not an allergic reaction but a delayed type immune response.

A Quick Tour of The Small Intestine

Normal small intestine

In digesting the foods we eat, it’s the small intestine that does the “heavy lifting.” This organ performs the major work of breaking the food (nutrients) down into smaller fragments or components in a process that is called digestion. These components are then absorbed by the small intestine. They include protein, carbohydrate, fats, minerals and vitamins. They are then released into the bloodstream which carries them to all the tissues and cells of the body. This process of digestion, absorption and release into the circulation involves the normal functioning of the stomach, small intestine, pancreas and liver.

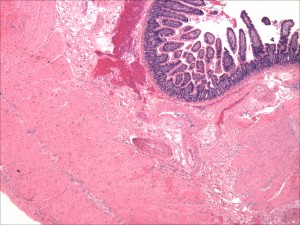

Critical to this process are tiny filaments called villi, which line the small intestine. These microscopic finger-like projections greatly expand the intestine’s surface area, maximizing the effective absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream. When the immune system of an individual with celiac disease goes into overdrive, it attacks and destroys intestinal villi (atrophy). Nutrients cannot be fully absorbed. This results in the term malabsorption. In celiac disease, all the components of the diet (carbohydrate, fats, minerals and vitamins) may be malabsorbed, or only a single nutrient such as a mineral (calcium or iron) or a single vitamin such as folic acid. The ability to take full nourishment from food is compromised.

The immune response in the intestine as well as causing atrophy of villi results in a marked inflammatory response and the generation of antibodies to food components (anti-gliadin antibodies and auto antibodies) tissue transglutaminase and endomysial antibodies. These antibodies while not causing any damage reflect the autoimmune nature of celiac disease and are used as diagnostic tests. This marked inflammatory response may be manifested as generalized systemic symptoms while the autoantibodies may be responsible or contribute to other organ damage and symptoms. In celiac disease, this systemic inflammatory response and multiple other organ involvement marks celiac disease as a multisystem disease. In fact, celiac disease more resembles a multisystem disorder with the possibility of every organ in the body being affected. Patients therefore may present with symptoms related to inflammation and malabsorption (diarrhea, abdominal pain and weight loss). Patients may present with manifestations of malabsorption of nutrients such as anemia due to iron deficiency or osteoporosis due to calcium and vitamin D malabsorption. Whereas the skin problem, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), reflects a systemic antibody response to tissue transglutaminase generated in the intestine but manifested in the skin by these antibodies reacting with tissue transglutaminase present in the skin. Other organ involvement may be the result of nutritional deficiency, antibody directed inflammation as part as an autoimmune response.

And once in attack mode, the immune system doesn’t always stop with the small intestine, but may also damage other organs.

Modes of Presentation of Celiac Disease

The classification of the main modes of presentation of adults with celiac disease into “classical” – diarrhea predominant and “silent” is widely accepted. The silent group includes atypical presentations and those presenting with complications of celiac disease as well as truly asymptomatic individuals picked up through screening high risk groups.

Presentation in Children

Children with untreated celiac disease are at special risk. Malnutrition during this period can have significant effects on growth and development. Failure to thrive in infants, learning difficulties in school-age children, irritability and behavioral difficulties, delayed puberty, and short stature as well as recurrent abdominal pain and constipation are all common symptoms of celiac disease.

Presentation in Adults

In order to assess the clinical spectrum of celiac disease in the United States, we obtained data on 1138 people with biopsy proven celiac disease. Our results demonstrated that the majority of individuals were diagnosed in their 4th to 6th decades. Females predominated (2.9:1); however the female predominance was less marked in the elderly. Diarrhea was the main mode of presentation, occurring in 85%. Most strikingly, symptoms were present a mean of 11 years prior to diagnosis.

In order to assess whether the presentation had changed over time we analyzed the mode of presentation for a series of patients seen in the Celiac Center at Columbia University in New York.4 There were 227 patients with biopsy proven celiac disease. We noted that females again predominated, in a ratio of 1.7 to 1. Mean age at diagnosis was 46.4 ± 1.0 years (range 16 to 82 years) and was similar in men and women. Females were younger and had a longer duration of symptoms compared to the males. Diarrhea was the main mode of presentation (in 62%) with the remainder classified as silent (38%). This later group included anemia or reduced bone density as presentations (15%), screening first-degree relatives (13%), and incidental diagnosis at endoscopy performed for such indications as reflux or dyspepsia (8%). We compared those diagnosed before and after 1993, (when serologic testing was first seen in patients), and noted a reduction in those presenting with diarrhea, 73% versus 43% (p=0.0001) and a reduction in the duration of symptoms, from 9.0 ± 1.1 years to 4.4 ± 0.6 years (p<0001). These results suggested that the use of serologic testing was responsible for more patients being detected with celiac disease having presented in non-classical ways, after a shorter duration of symptoms. Further analysis of the patients seen at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University has revealed that progressively fewer patients are presenting with diarrhea, less than 50% of those diagnosed in the last 10 years.

Many patients with celiac disease, 36% in our series and 29% of Canadians with celiac disease, have had a previous diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. In fact, screening of patients seen in irritable bowel referral clinics in England and Iran reveals celiac disease in a significant number of patients. The majority of patients with celiac disease, detected in a primary care screening study had symptoms attributable to an irritable bowel syndrome.

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Iron deficiency anemia was the mode of presentation in 8% of the individuals seen by us, 4 and was reported as a prior diagnosis in 40% of Canadians with celiac disease. In a study from the Mayo Clinic, celiac disease was identified as the cause of iron deficiency in 15% of those undergoing endoscopic assessment for iron deficiency. While in a prospective study of adults, mean age in their 50’s, Karnum et al found 2.8% to have celiac disease. Anemia in celiac disease is typically due to iron deficiency, though vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency may also be present and contribute to anemia.

Osteoporosis

A diagnosis of celiac disease may be made during the evaluation of reduced bone density (osteopenia or osteoporosis). In our study reduced bone density was more severe in men than women. Certainly men and premenopausal women with osteoporosis should be evaluated for celiac disease even if they lack evidence of calcium malabsorption, though the yield in menopausal women is low.

Incidental Recognition at Endoscopy for Reflux

An increasingly important mode of presentation is the recognition of endoscopic signs of villous atrophy in individuals who undergo endoscopy for symptoms not typically associated with celiac disease. These endoscopic signs include reduction in duodenal folds, scalloping of folds and the presence of mucosal fissures. The indications for upper gastrointestinal symptoms include dyspepsia, upper abdominal pain or gastroesophageal reflux. This presentation accounted for 10% of those who were diagnosed with celiac disease in our series. Interestingly symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux may resolve after starting a gluten-free diet. This is thought to be due to resolution of an accompanying motility disorder. These endoscopic abnormalities of the duodenal mucosa are not specific nor sensitive markers of celiac disease.

There is an argument for the routine biopsy of the duodenum in anyone undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to detect celiac disease, irrespective of the appearance of the duodenal mucosa.

Screening of high risk groups is, especially relatives of patients with celiac disease is a major mode of presentation. Studies reveal that 5% to 10% of first degree relatives of patients with celiac disease have serologic and biopsy evidence of the disease. A single testing of relatives does not suffice to detect all those with celiac disease. For those initially negative by screening antibodies, 3.5% will become positive a mean of 2 years after their initial testing. Other groups that are frequently screened for celiac disease include those with Type 1 diabetes, Down syndrome, and primary biliary cirrhosis.

Atypical Presentations

Among the atypical presentations that we have encountered are neurologic problems. We have found that 8% of those attending a peripheral neuropathy center, for evaluation of peripheral neuropathy, had celiac disease. The neuropathy is typically sensory in type, involving the limbs and sometimes the face. Nerve conduction studies are frequently normal; however skin biopsies reveal nerve damage in small fibers. We have also identified patients with severe ataxia. We have not identified patients with epilepsy, a neurologic manifestation that may be more common in childhood celiac disease.

Other, less common presentations, are abnormalities of blood chemistry determinations such as elevated serum amylase, secondary to macroamylasemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypocalcemia, vitamin deficiency states, and evidence of hyposplenism. We have seen patients referred because of dental enamel defects. Many females diagnosed with celiac disease have a history of infertility and there is a yield of screening infertile individuals for celiac disease.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Many people with gluten intolerance experience symptoms mainly as Dermatitis Herpetiformis (DH), a chronic disease of the skin. Patches of intensely itchy raised spots appear on the body, often symmetrically, on both elbows or both buttocks for example. However, it can occur anywhere on the body. It may occur on the face or in the hair, especially along the hairline. In this case, the immune system’s response consists of an immune reaction of anti tissue transglutaminase antibodies with a special form of tissue transglutaminase found in the skin. The lesions will typically form little blisters resembling herpes, hence its name, dermatitis herpetiformis.

Everyone with DH is considered to have a gluten sensitivity (celiac disease). While the majority of people will have an abnormal intestinal biopsy that demonstrates the characteristic changes of celiac disease, in 20% the biopsy can be normal. The diagnosis of DH requires a biopsy of skin immediately adjacent to a blistering lesion. Special studies (immunofluorescence for IgA deposition) are required for diagnosis. The lesions are very sensitive to ingestion of small amounts of gluten. Some patients require therapy with Dapsone to suppress the lesions. This may be used intermittingly and is not needed when patients are adhering to a strict gluten-free diet. Withdrawl of iodine from the diet may be necessary for the gluten-free diet to have a beneficial effect.

Patients with DH are a risk for all the complications that those with celiac disease but not DH experience. These include osteoporosis, iron deficiency anemia and vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Patients should be assessed regularly for these complications and treated accordingly. DH similar to celiac disease is associated with an increased risk of lymphoma. The gluten-free diet will protect against the development of lymphoma whereas Dapsone does not. A common problem is that patients will use Dapsone to control the lesions and not adhere to a gluten-free diet.

Autoimmune damage, the first manifestation of celiac disease, carries with it an array of potential symptoms. But as happens so often in life, one thing leads to another. When the immune system compromises the ability of the small intestine to absorb and transmit nutrients, malnutrition may result. And malnutrition carries its own array of potential disease symptoms. 250 different celiac disease symptoms and related conditions have so far been identified, among them. However the spectrum of the disease is very great with some people obese rather than malnourished.

Celiac Disease –multiple manifestations

Patients often have a vast array of symptoms and complications, not justone symptom. Here is a list which is not exhaustive. Patients with thesesymptoms warrant screening for celiac disease.

Gastrointestinal

- Recurring abdominal pain

- Chronic diarrhea

- Constipation

- Persistent anemia

- Chronic fatigue

- Weight loss

- Osteopenia, osteoporosis and fractures

- Infertility

- Muscle cramps

- Discoloration and loss of tooth enamel

Autoimmune Associations

- Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH)

- Aphthous stomatitis/ulcers

- Peripheral neuropathy, ataxia and epilepsy

- Thyroid disease

- Sjogren’s syndrome

- Chronic active hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing

- Cholangitis

Malignancies

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (intestinal and extra-intestinal, T- and B-cell types)

- Small intestinal adenocarcinoma

- Esophageal carcinoma

- Papillary thyroid cancer

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clin Med (Lond)

- v.20(4); 2020 Jul

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of multiple sclerosis

Leeds Centre for Neurosciences, Leeds, UK

The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) is through clinical assessment and supported by investigations. There is no single accurate and reliable diagnostic test. MS is a disease of young adults with a female predominance. There are characteristic clinical presentations based on the areas of the central nervous system involved, for example optic nerve, brainstem and spinal cord. The main pattern of MS at onset is relapsing–remitting with clinical attacks of neurological dysfunction lasting at least 24 hours. The differential diagnosis includes other inflammatory central nervous system disorders. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and lumbar puncture are the key investigations. New diagnostic criteria have been developed to allow an earlier diagnosis and thus access to effective disease modifying treatments.

- The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis supported by investigation findings.

- There is no single sensitive and specific diagnostic test for multiple sclerosis.

- The principle of dissemination of lesions in time and space underpins the diagnosis.

- Eighty-five per cent of people with multiple sclerosis have a relapsing-remitting course at onset.

- New diagnostic criteria aim to allow an earlier, accurate diagnosis.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating central nervous system (CNS) disease. Its onset is typically in adults with peak age at onset between 20–40 years. There is a female predominance of up to 3:1. The course of MS is relapsing–remitting (RRMS) at onset in 85% with episodes of neurological dysfunction followed by complete or incomplete recovery. Fifteen per cent of people present with a gradually progressive disease course from onset known as primary progressive MS (PPMS). A single episode in isolation with no previous clinical attacks in someone who does not fulfil the diagnostic criteria for MS is known as clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). Over time, people with RRMS can develop gradually progressive disability called secondary progressive MS (SPMS). This usually occurs at least 10–15 years after disease onset. These descriptions of clinical disease course are still used in practice (Fig (Fig1). 1 ). However, increased understanding of MS and its pathology has led to new definitions focused on disease activity (based on clinical or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings) and disease progression. 1

Multiple sclerosis disease course.

Clinical presentation

MS is a CNS disease characterised by demyelinating lesions in regions including the optic nerves, brainstem, cerebellum, periventricular and spinal cord. Histopathology also shows widespread involvement of the cerebral grey matter, although this is not well appreciated on conventional MRI. The clinical features of an MS attack depend on the areas of the brain or spinal cord involved. As this is an inflammatory condition, the onset of symptoms of an attack in RRMS is usually gradual and can evolve over days. Sudden onset with symptoms maximal at onset would be much more suggestive of a vascular event. A clinical attack must last at least 24 hours in the absence of fever or infection. In primary progressive MS, symptoms would be expected to have a gradual and insidious onset over at least 12 months by the time of diagnosis.

A common first presentation of RRMS is with unilateral optic neuritis characterised by gradual onset monocular visual loss, pain on moving the eye and altered colour vision. Visual loss rarely progresses beyond 2 weeks from the onset. Visual recovery usually takes longer than 2 weeks and may not recover to baseline. On examination, visual acuity is typically reduced, there may be a relative afferent pupillary defect, a central scotoma or impaired colour vision. On funduscopy, the optic disc may appear normal (retrobulbar neuritis) or swollen acutely, and may become pale and atrophic over time following the attack.

An inflammatory lesion in the spinal cord causes a myelitis that is usually partial and presents with gradual onset sensory and motor symptoms of the limbs. Evolution is over hours to days. The severity of myelitis can vary from a mild sensory syndrome to a severe disabling attack causing tetraparesis. A lesion in the cervical cord can cause Lhermitte's phenomenon with an electric shock-like sensation down the neck and back on flexing the neck. This can be a useful clue to the diagnosis. Thoracic cord lesions can cause a tight band-like sensation around the trunk or abdomen often described as the ‘MS hug’. In severe cases this has been misinterpreted as being due to a cardiac event. On examination, signs can include sensory signs of reduced fine touch, vibration sense and joint position sense. There may be a sensory level. Motor signs are typical of an upper motor neuron lesion with increased tone or spasticity, pyramidal weakness and hyperreflexia with extensor plantar responses. Myelitis may be partial causing a hemi-cord syndrome or partial Brown-Séquard.

Brainstem syndromes can present with diplopia, oscillopsia, facial sensory loss, vertigo and dysarthria. Typical findings include an isolated sixth nerve palsy, gaze evoked nystagmus or an internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia is pathognomonic of MS.

The diagnosis of MS is based on the clinical features of the attacks including the history and examination findings. The guiding principle of the diagnosis is that of dissemination in time (DIT) and dissemination in space (DIS). There is no single diagnostic laboratory test for MS. The diagnosis is based on the clinical findings supported by investigations.

Investigations

Magnetic resonance imaging.

MRI has been increasingly used to support the diagnosis of MS and to look for any atypical features suggesting an alternative diagnosis. Brain and spinal cord MRI are used to determine dissemination in space (DIS) and for evidence of dissemination in time (DIT) in patients with a typical CIS. DIS can be demonstrated by one or more MRI T2-hyperintense lesions that are characteristic of MS in two or more of four areas of the CNS: periventricular; cortical or juxtacortical; infratentorial; and the spinal cord. DIT can be demonstrated by the simultaneous presence of gadolinium-enhancing and non-enhancing lesions at any time or a new T2 lesion or gadolinium-enhancing lesion on follow-up MRI. 2

Cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination remains a valuable diagnostic test, particularly when clinical and MRI evidence is insufficient to confirm the diagnosis of MS. There has been a major change in the most recent MS diagnostic criteria in that oligoclonal bands in the CSF can be used as a surrogate marker of DIT to confirm the diagnosis of RRMS in people with CIS and MRI evidence of DIS. 3 CSF findings are also important when there is a progressive course from onset (PPMS) and when there are any atypical clinical or imaging findings. Evidence of intrathecal antibody synthesis (ie oligoclonal bands in the CSF but not in a paired serum sample) supports the diagnosis of MS. An elevated CSF protein >1.0 g/L or significant pleocytosis >50 cells/mm³ or the presence of neutrophils would suggest an alternative diagnosis.

Visually evoked potentials and optical coherence tomography

Visually evoked potentials (VEPs) were historically included in MS diagnostic criteria with an abnormal VEP (delayed but with a well preserved waveform) being used as objective evidence of a second lesion if the clinical presentation did not include the visual pathway. 4,5 In the 2017 criteria, it was recommended that further studies are needed to determine the role of VEPs and optical coherence tomography (OCT) in supporting the diagnosis of MS and VEPs are not included in the criteria. 3 In clinical practice VEPs can be useful, for example in a patient with a progressive spinal cord syndrome and normal brain MRI.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of MS is wide and varies depending on the site of presentation eg optic nerve or spinal cord. It is important for the clinician to be vigilant for atypical clinical findings or investigation results. 6,7 Non-specific symptoms with white matter lesions on the MRI can be a common cause of misdiagnosis of common disorders, such as migraine or small vessel vascular disease in the elderly.

Other CNS inflammatory diseases including neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody-associated disease and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) are important differential diagnoses as the treatment approaches are different. Several other rarer inflammatory, infective and metabolic conditions should also be considered (Table (Table1 1 ).

Differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis

| Autoimmune/inflammatory | CNS infections | Metabolic | Vascular conditions | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) | CNS syphilis | Vitamin B deficiency | Small vessel disease | CNS lymphoma |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) | Lyme disease | Copper deficiency | Stroke | Paraneoplastic |

| Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody disease | Human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV) | Mitochondrial disease | CADASIL | |

| Sjögren's syndrome | HIV | Leukodystrophies | Susac's syndrome | |

| CNS lupus | Anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome | |||

| Sarcoidosis | ||||

| Behçet's | ||||

| CNS vasculitis |

CADASIL = cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy; CNS = central nervous system.

NMOSD is an inflammatory CNS syndrome distinct from MS that can be associated with serum aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G antibodies (AQP4-IgG). 8 NMOSD is stratified by serologic testing into NMOSD with or without AQP4-IgG. NMOSD presents with severe episodes of complete transverse myelitis and/or severe episodes of optic neuritis with incomplete recovery or a brainstem syndrome of the area postrema causing nausea and vomiting or hiccups. More stringent clinical criteria with additional neuroimaging findings, are required for diagnosis of NMOSD without AQP4-IgG or when serologic testing is unavailable. The myelitis is usually extensive on MRI with a T2 spinal cord lesion extending over three or more spinal segments (longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM)). Brain lesions in NMO are located in areas of high expression of aquaporin 4, including the hypothalamus, medulla, and other brainstem areas. Oligoclonal bands in the CSF are detected in 10–20% of patients with NMO.

MOG antibody disease is associated with pathogenic serum antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. 9 Most are AQP4-IgG-seronegative. The presentation is varied ranging from isolated optic neuritis to classic NMO to ADEM. It affects both children and adults and there is no sex predominance. The disease can relapse, but medium-term immunosuppression is usually effective. Permanent disability is less frequent than in NMOSD associated with positive AQP4 antibodies. Sphincter and sexual dysfunction are common as the transverse myelitis involves the conus.

ADEM tends to present with a subacute encephalopathy with altered level of consciousness, behaviour or cognitive function. It often follows an infectious illness and is most common in children. It was initially thought to be a monophasic condition, but some patients experience recurrence of their initial ADEM symptoms. Around 60% of children with ADEM have MOG antibodies. MRI typically shows symmetrical multifocal or diffuse brain lesions (Table (Table1 1 ).

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnostic criteria for MS have been developed since the first description of MS as ‘La sclérose en plaques disséminées’ by Charcot in 1868. He described a triad of nystagmus, intention tremor and scanning speech. Clinical criteria were supplemented by CSF, MRI and evoked potentials in the Poser criteria in 1983. 4 With the more widespread availability of MRI, the McDonald criteria were developed by the International Panel on Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis in 2001 giving increasing weight to MRI in the diagnosis of MS. 5 There have been subsequent revisions of these criteria in 2005 and 2010 with the most recent revision in 2017 (Table (Table2 2 ). 3 The new criteria allow for an earlier diagnosis of MS in patients experiencing a typical clinically isolated syndrome. Earlier diagnosis of MS has become much more important with the availability of highly effective disease modifying treatments (DMTs) for MS. However, the benefits of earlier diagnosis have to be balanced with the risks of misdiagnosis. 10 The 2017 position paper addresses concerns about the potential for misdiagnosis, particularly with misinterpretation of non-specific symptoms and non-specific MRI findings. The development of the 2017 McDonald criteria was informed by the new MRI criteria for diagnosing MS proposed by the European Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis (MAGNIMS) network. 1,2

2017 McDonald criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in patients with an attack at onset 3

| Number of attacks at clinical presentation | Number of lesions with objective clinical evidence | Additional data needed for diagnosis of multiple sclerosis |

|---|---|---|

| ≥2 | ≥2 | None |

| ≥2 | 1 (as well as clear-cut historical evidence of a previous attack involving a lesion in a distinct anatomical location) | None |

| ≥2 | 1 | Dissemination in space demonstrated by an additional clinical attack implicating a different CNS site |

| Or by MRI | ||

| 1 | ≥2 | Dissemination in time demonstrated by an additional clinical attack |

| Or by MRI | ||

| Or demonstration of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands | ||

| 1 | 1 | Dissemination in space demonstrated by an additional clinical attack implicating a different CNS site |

| Or by MRI | ||

| And dissemination in time demonstrated by an additional clinical attack | ||

| Or by MRI | ||

| Or demonstration of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands |

a = no additional tests are required to demonstrate dissemination in space and time. However, unless MRI is not possible, brain MRI should be obtained in all patients in whom the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is being considered. In addition, spinal cord MRI or CSF examination should be considered in patients with insufficient clinical and MRI evidence supporting multiple sclerosis, with a presentation other than a typical clinically isolated syndrome, or with atypical features. If imaging or other tests (eg CSF) are undertaken and are negative, caution needs to be taken before making a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, and alternative diagnoses should be considered. CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The diagnosis of MS is still based on a combination of clinical, MRI and laboratory (eg CSF) findings. The diagnostic criteria are designed to be used for patients with typical clinical presentations and should not be applied in cases where MRI changes are incidentally identified in asymptomatic individuals. In that situation, cases are referred to as radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS). The risk of misdiagnosis may have harmful consequences if patients are started on DMTs inappropriately, for example, some MS DMTs can worsen outcomes for patients with NMO spectrum disorders.

The aim of the criteria is to make an earlier and accurate diagnosis of MS and lessen the period of uncertainty for the patient and clinician. This enables appropriate management including confirmation of the diagnosis for the patient and access to effective disease modifying treatments.

The clinical diagnosis of MS is based on history and examination providing evidence of typical neurological dysfunction. Dissemination in time and space can be demonstrated clinically but MRI is now routinely used to confirm the diagnosis. With a single episode, or clinically isolated syndrome, MRI evidence can allow an earlier diagnosis using new diagnostic criteria. Over-interpretation of non-specific symptoms and non-specific white matter lesions on MRI can lead to misdiagnosis. The differential diagnosis of MS includes other CNS inflammatory conditions such as NMOSD, ADEM and MOG antibody-related disease. It is important to differentiate these conditions as the treatment approach is different. CNS infections, metabolic conditions and vascular disease also need to be considered. There are now highly effective DMTs for MS and an accurate, timely diagnosis is crucial to ensure appropriate access to treatment.

How Do Patients Present? Acute and Chronic Presentations

- First Online: 01 June 2020

Cite this chapter

- Michael Hoffmann MD, PhD 2

276 Accesses

Certain stereotyped neurological presentations are typical in the clinic, hospital, or emergency room environment (Table 3.1).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1456–66.

Article Google Scholar

Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Jak AJ, et al. “Missed” mild cognitive impairment: high false-negative error rate based on conventional diagnostic criteria. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;52:685–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150986 .

Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2018;90:126–35.

O’Donnell MJ, et al. Risk factors for ischemic and intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (Interstroke study): a case control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–23.

Viswanathan A, Rocca WA, Tzourio C. Vascular risk factors and dementia: how to move forward? Neurology. 2009;72:368–74.