Home — Blog — Topic Ideas — Essay Topics on Racism: 150 Ideas for Analysis and Discussion

Essay Topics on Racism: 150 Ideas for Analysis and Discussion

Here’s a list of 150 essay ideas on racism to help you ace a perfect paper. The subjects are divided based on what you require!

Before we continue with the list of essay topics on racism, let's remember the definition of racism. In brief, it's a complex prejudice and a form of discrimination based on race. It can be done by an individual, a group, or an institution. If you belong to a racial or ethnic group, you are facing being in the minority. As it's usually caused by the group in power, there are many types of racism, including socio-cultural racism, internal racism, legal racism, systematic racism, interpersonal racism, institutional racism, and historical racism. You can also find educational or economic racism as there are many sub-sections that one can encounter.

150 Essay Topics on Racism to Help You Ace a Perfect Essay

General Recommendations

The subject of racism is one of the most popular among college students today because you can discuss it regardless of your academic discipline. Even though we are dealing with technical progress and the Internet, the problem of racism is still there. The world may go further and talk about philosophical matters, yet we still have to face them and explore the challenges. It makes it even more difficult to find a good topic that would be unique and inspiring. As a way to help you out, we have collected 150 racism essay topics that have been chosen by our experts. We recommend you choose something that motivates you and narrow things down a little bit to make your writing easier.

Why Choose a Topic on Racial Issues?

When we explore racial issues, we are not only seeking the most efficient solutions but also reminding ourselves about the past and the mistakes that we should never make again. It is an inspirational type of work as we all can change the world. If you cannot choose a topic that inspires you, think about recent events, talk about your friend, or discuss something that has happened in your local area. Just take your time and think about how you can make the world a safer and better place.

The Secrets of a Good Essay About Racism

The secret to writing a good essay on racism is not only stating that racism is bad but by exploring the origins and finding a solution. You can choose a discipline and start from there. For example, if you are a nursing student, talk about the medical principles and responsibilities where every person is the same. Talk about how it has not always been this way and discuss the methods and the famous theorists who have done their best to bring equality to our society. Keep your tone inspiring, explore, and tell a story with a moral lesson in the end. Now let’s explore the topic ideas on racism!

General Essay Topics On Racism

As we know, no person is born a racist since we are not born this way and it cannot be considered a biological phenomenon. Since it is a practice that is learned and a social issue, the general topics related to racism may include socio-cultural, philosophical, and political aspects as you can see below. Here are the ideas that you should consider as you plan to write an essay on racial issues:

- Are we born with racial prejudice?

- Can racism be unlearned?

- The political constituent of the racial prejudice and the colonial past?

- The humiliation of the African continent and the control of power.

- The heritage of the Black Lives Matter movement and its historical origins.

- The skin color issue and the cultural perceptions of the African Americans vs Mexican Americans.

- The role of social media in the prevention of racial conflicts in 2022 .

- Martin Luther King Jr. and his role in modern education.

- Konrad Lorenz and the biological perception of the human race.

- The relation of racial issues to nazism and chauvinism.

The Best Racism Essay Topics

School and college learners often ask about what can be considered the best essay subject when asked to write on racial issues. Essentially, you have to talk about the origins of racism and provide a moral lesson with a solution as every person can be a solid contribution to the prevention of hatred and racial discrimination.

- The schoolchildren's example and the attitude to the racial conflicts.

- Perception of racism in the United States versus Germany.

- The role of the scouting movement as a way to promote equality in our society.

- Social justice and the range of opportunities that African American individuals could receive during the 1960s.

- The workplace equality and the negative perception of the race when the documents are being filed.

- The institutional racism and the sources of the legislation that has paved the way for injustice.

- Why should we talk to the children about racial prejudice and set good examples ?

- The role of anthropology in racial research during the 1990s in the USA.

- The Black Poverty phenomenon and the origins of the Black Culture across the globe.

- The controversy of Malcolm X’s personality and his transition from anger to peacemaking.

Shocking Racism Essay Ideas

Unfortunately, there are many subjects that are not easy to deal with when you are talking about the most horrible sides of racism. Since these subjects are sensitive, dealing with the shocking aspects of this problem should be approached with a warning in your introduction part so your readers know what to expect. As a rule, many medical and forensic students will dive into the issue, so these topic ideas are still relevant:

- The prejudice against wearing a hoodie.

- The racial violence in Western Africa and the crimes by the Belgian government.

- The comparison of homophobic beliefs and the link to racial prejudice.

- Domestic violence and the bias towards the cases based on race.

- Racial discrimination in the field of the sex industry.

- Slavery in the Middle East and the modern cultural perceptions.

- Internal racism in the United States: why the black communities keep silent.

- Racism in the American schools: the bias among the teachers.

- Cyberbullying and the distorted image of the typical racists .

- The prisons of Apartheid in South Africa.

Light and Simple Ideas Regarding Racism

If you are a high-school learner or a first-year college student, your essay on racism may not have to represent complex research with a dozen of sources. Here are some good ideas that are light and simple enough to provide you with inspiration and the basic points to follow:

- My first encounter with racial prejudice.

- Why do college students are always in the vanguard of social campaigns?

- How are the racial issues addressed by my school?

- The promotion of the African-American culture is a method to challenge prejudice and stereotypes.

- The history of blues music and the Black culture of the blues in the United States.

- The role of slavery in the Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain.

- School segregation in the United States during the 1960s.

- The negative effect of racism on the mental health of a person.

- The advocacy of racism in modern society .

- The heritage of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and the modern perception of the historical issues.

Interesting Topics on Racism For an Essay

Contrary to the popular belief, when you have to talk about the cases of racial prejudice, you will also encounter many interesting essay topic ideas. As long as these are related to your main academic course, you can explore them. Here are some great ideas to consider:

- Has the perception of Michael Jackson changed because of his skin transition?

- The perception of racial problems by the British Broadcasting Corporation.

- The role of the African American influencers on Instagram.

- The comparison between the Asian students and the Mexican learners in the USA.

- Latin culture and the similarities when compared to the Black culture with its peculiarities.

- The racial impact in the “Boy In The Stripped Pajamas”.

- Can we eliminate racism completely and how exactly, considering the answer is “Yes”?

- Scientific research of modern racism and social media campaigns.

- Why do some people believe that the Black Lives Matter movement is controversial?

- Male vs female challenges in relation to racial attitudes.

Argumentative Essay Topics About Race

An argumentative type of writing requires making a clear statement or posing an assumption that will deal with a particular question. As we are dealing with racial prejudice or theories, it is essential to support your writing with at least one piece of evidence to make sure that you can support your opinion and stand for it as you write. Here are some good African American argumentative essay examples of topics and other ideas to consider:

- Racism is a mental disorder and cannot be treated with words alone.

- Analysis of the traumatic experiences based on racial prejudice.

- African-American communities and the sense of being inferior are caused by poverty.

- Reading the memoirs of famous people that describe racial issues often provides a distorted image through the lens of a single person.

- There is no academic explanation of racism since every case is different and is often based on personal perceptions.

- The negatives of the post-racial perception as the latent system that advocates racism.

- The link of racial origins to the concept of feminism and gender inequality.

- The military bias and the merits that are earned by the African-American soldiers.

- The media causes a negative image of the Latin and Mexican youth in the United States.

- Does racism exist in kindergarten and why the youngsters do not think about racial prejudice?

Racism Research Paper Topics

Dealing with The Black Lives Matter essay , you should focus on those aspects of racism that are not often discussed or researched by the media. You can take a particular case study or talk about the reasons why the BLM social campaign has started and whether the timing has been right. Here are some interesting racism topics for research paper that you should consider:

- The link of criminal offenses to race is an example of the primary injustice .

- The socio-emotional burdens of slavery that one can trace among the representatives of the African-American population.

- Study of the cardio-vascular diseases among the American youth: a comparison of the Caucasian and Latin representatives.

- The race and the politics: dealing with the racial issues and the Trump administration analysis.

- The best methods to achieve medical equality for all people: where race has no place to be.

- The perception of racism by the young children: the negative side of trying to educate the youngsters.

- Racial prejudice in the UK vs the United States: analysis of the core differences.

- The prisons in the United States: why do the Blacks constitute the majority?

- The culture of Voodoo and the slavery: the link between the occult practices.

- The native American people and the African Americans: the common woes they share.

Racism in Culture Topics

Racism topics for essay in culture are always upon the surface because we can encounter them in books, popular political shows, movies, social media, and more. The majority of college students often ignore this aspect because things easily become confusing since one has to take a stand and explain the point. As a way to help you a little bit, we have collected several cultural racism topic ideas to help you start:

- The perception of wealth by the Black community: why it differs when researched through the lens of past poverty?

- The rap music and the cultural constituent of the African-American community.

- The moral constituent of the political shows where racial jargon is being used.

- Why the racial jokes on television are against the freedom of speech?

- The ways how the modern media promotes racism by stirring up the conflict and actually doing harm.

- The isolated cases of racism and police violence in the United States as portrayed by the movies.

- Playing with the Black musicians: the history of jazz in the United States.

- The social distancing and the perception of isolation by the different races.

- The cultural multitude in the cartoons by the Disney Corporations: the pros and cons.

- From assimilation to genocide: can the African American child make it big without living through the cultural bias?

Racism Essay Ideas in Literature

One of the best ways to study racism is by reading the books by those who have been through it on their own or by studying the explorations by those who can write emotionally and fight for racial equality where racism has no place to be. Keeping all of these challenges in mind, our experts suggest turning to the books as you can explore racism in the literature by focusing on those who are against it and discussing the cases in the classic literature that are quite controversial.

- The racial controversy of Ernest Hemingway's writing.

- The personal attitude of Mark Twain towards slavery and the cultural peculiarities of the times.

- The reasons why "To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee book has been banned in libraries.

- The "Hate You Give" by Angie Thomas and the analysis of the justified and "legit" racism.

- Is the poetry by the gangsta rap an example of hidden racism?

- Maya Angelou and her timeless poetry.

- The portrayal of xenophobia in modern English language literature.

- What can we learn from the "Schilder's List" screenplay as we discuss the subject of genocide?

- Are there racial elements in "Othello" or Shakespeare's creation is beyond the subject?

- Kate Chopin's perception of inequality in "Desiree's Baby".

Racism in Science Essay Ideas

Racism is often studied by scientists because it's not only a cultural point or a social agenda that is driven by personal inferiority and similar factors of mental distortion. Since we can talk about police violence and social campaigns, it is also possible to discuss things through different disciplines. Think over these racism thesis statement ideas by taking a scientific approach and getting a common idea explained:

- Can physical trauma become a cause for a different perception of race?

- Do we inherit racial intolerance from our family members and friends?

- Can a white person assimilate and become a part of the primarily Black community?

- The people behind the concept of Apartheid: analysis of the critical factors.

- Can one prove the fact of the physical damage of the racial injustice that lasted through the years?

- The bond between mental diseases and the slavery heritage among the Black people.

- Should people carry the blame for the years of social injustice?

- How can we explain the metaphysics of race?

- What do the different religions tell us about race and the best ways to deal with it?

- Ethnic prejudices based on age, gender, and social status vs general racism.

Cinema and Race Topics to Write About

As a rule, the movies are also a great source for writing an essay on racial issues. Remember to provide the basic information about the movie or include examples with the quotations to help your readers understand all the major points that you make. Here are some ideas that are worth your attention:

- The negative aspect of the portrayal of racial issues by Hollywood.

- Should the disturbing facts and the graphic violence be included in the movies about slavery?

- Analysis of the "Green Mile" movie and the perception of equality in our society.

- The role of music and culture in the "Django Unchained" movie.

- The "Ghosts of Mississippi" and the social aspect of the American South compared to how we perceive it today.

- What can we learn from the "Malcolm X" movie created by Spike Lee?

- "I am Not Your Negro" movie and the role of education through the movies.

- "And the Children Shall Lead" the movie as an example that we are not born racist.

- Do we really have the "Black Hollywood" concept in reality?

- Do the movies about racial issues only cause even more racial prejudice?

Race and Ethnic Relations

Another challenging problem is the internal racism and race and ethnicity essay topics that we can observe not only in the United States but all over the world as well. For example, the Black people in the United States and the representatives of the rap music culture will divide themselves between the East Coast and the West Coast where far more than cultural differences exist. The same can be encountered in Afghanistan or in Belgium. Here are some essay topics on race and ethnicity idea samples to consider:

- The racial or the ethnic conflict? What can we learn from Afghan society?

- Religious beliefs divide us based on ethnicity .

- What are the major differences between ethnic and racial conflicts?

- Why we are able to identify the European Black person and the Black coming from the United States?

- Racism and ethnicity's role in sports.

- How can an ethnic conflict be resolved with the help of anti-racial methods?

- The medical aspect of being an Asian in the United States.

- The challenges of learning as an African American person during the 1950s.

- The role of the African American people in the Vietnam war and their perception by the locals.

- Ethnicity's role in South Africa as the concept of Apartheid has been formed.

Biology and Racial Issues

If you are majoring in Biology or would like to research this side of the general issue of race, it is essential to think about how we can fight racism in practice by turning to healthcare or the concepts that are historical in their nature. Although we cannot explain slavery per se other than by turning to economics and the rule of power that has no justification, biologists believe that racial challenges can be approached by their core beliefs as well.

- Can we create an isolated non-racist society in 2022?

- If we assume that a social group has never heard of racism, can it occur?

- The physical versus cultural differences in the racial inequality cases?

- The biological peculiarities of the different races?

- Do we carry the cultural heritage of our race?

- Interracial marriage through the lens of Biology.

- The origins of the racial concept and its evolution.

- The core ways how slavery has changed the African-American population.

- The linguistic peculiarities of the Latin people.

- The resistance of the different races towards vaccination.

Modern Racism Topics to Consider

In case you would like to deal with a modern subject that deals with racism, you can go beyond the famous Black Lives Matter movement by focusing on the cases of racism in sports or talking about the peacemakers or the famous celebrities who have made a solid difference in the elimination of racism.

- The Global Citizen campaign is a way to eliminate racial differences.

- The heritage of Aretha Franklin and her take on the racial challenges.

- The role of the Black Stars in modern society: the pros and cons.

- Martin Luther King Day in the modern schools.

- How can Instagram help to eliminate racism?

- The personality of Michelle Obama as a fighter for peace.

- Is a society without racism a utopian idea?

- How can comic books help youngsters understand equality?

- The controversy in the death of George Floyd.

- How can we break down the stereotypes about Mexicans in the United States?

Racial Discrimination Essay Ideas

If your essay should focus on racial discrimination, you should think about the environment and the type of prejudice that you are facing. For example, it can be in school or at the workplace, at the hospital, or in a movie that you have attended. Here are some discrimination topics research paper ideas that will help you to get started:

- How can a schoolchild report the case of racism while being a minor?

- The discrimination against women's rights during the 1960s.

- The employment problem and the chances of the Latin, Asian, and African American applicants.

- Do colleges implement a certain selection process against different races?

- How can discrimination be eliminated via education?

- African-American challenges in sports.

- The perception of discrimination, based on racial principles and the laws in the United States.

- How can one report racial comments on social media?

- Is there discrimination against white people in our society?

- Covid-19 and racial discrimination: the lessons we have learned.

Find Even More Essay Topics On Racism by Visiting Our Site

If you are unsure about what to write about, you can always find an essay on racism by visiting our website. Offering over 150 topic ideas, you can always get in touch with our experts and find another one!

5 Tips to Make Your Essay Perfect

- Start your essay on racial issues by narrowing things down after you choose the general topic.

- Get your facts straight by checking the dates, the names, opinions from both sides of an issue, etc.

- Provide examples if you are talking about the general aspects of racism.

- Do not use profanity and show due respect even if you are talking about shocking things. The same relates to race and ethnic relations essay topics that are based on religious conflicts. Stay respectful!

- Provide references and citations to avoid plagiarism and to keep your ideas supported by at least one piece of evidence.

Recommendations to Help You Get Inspired

Speaking of recommended books and articles to help you start with this subject, you should check " The Ideology of Racism: Misusing Science to Justify Racial Discrimination " by William H. Tucker who is a professor of social sciences at Rutgers University. Once you read this great article, think about the poetry by Maya Angelou as one of the best examples to see the practical side of things.

The other recommendations worth checking include:

- How to be Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi . - White Fragility by Robin Diangelo . - So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo .

The Final Word

We sincerely believe that our article has helped you to choose the perfect essay subject to stir your writing skills. If you are still feeling stuck and need additional help, our team of writers can assist you in the creation of any essay based on what you would like to explore. You can get in touch with our skilled experts anytime by contacting our essay service for any race and ethnicity topics. Always confidential and plagiarism-free, we can assist you and help you get over the stress!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

SCOTUS Says You Can Discuss Race in Your College Essay. Should You?

The us supreme court banned colleges’ affirmative action admission practices, raising a question about students writing about race in their college essay.

Although the Supreme Court says college application essays may discuss race and disadvantage, BU experts say inauthentic or traumatic recollections won’t cut it. Photo by Delmaine Donson/iStock

Should You Discuss Race in Your College Essay?

“Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration or otherwise.” — Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts

“The student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race. Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. …Universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.”—Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts

Confused? So are many in higher education. When the United States Supreme Court sacked affirmative action racial preferences in June, Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion, while spotlighting applicants’ personal essays, also put vague guardrails around their use. And anyway, not every young person who has suffered racial discrimination wants to revisit it in their essay, that critical part of applying to college where students tell their story in their voice.

After the SCOTUS decision, the advice from Boston University admissions and college guidance experts is this: your story must always be authentic. It can be about discrimination or other challenges met and dealt with, but it need not be. And it shouldn’t be , if writing about it means revisiting traumatic experiences.

“The essay for us is just going to continue to be as important as it always was,” notwithstanding the new legal landscape, says Kelly Walter (Wheelock’81), BU dean of admissions and associate vice president for enrollment. She has discussed the ruling with the University’s legal office, she says, and her office has tweaked BU’s two essay question options applicants must choose from. (The University also asks potential future Terriers to complete the Common Application for college, which has its own essay requirement.) The tweaks were partly in response to the court ruling, Walter says, but also to ensure that the questions conveyed to students “what BU stood for, and that we value diversity. We thought it was very important to put that out there front and center, and for them to be able to specifically respond to our commitment, our values, as it relates to one of these two essay questions.”

Those questions are:

Reflect on a social or community issue that deeply resonates with you. Why is it important to you, and how have you been involved in addressing or raising awareness about it? What about being a student at BU most excites you? How do you hope to contribute to our campus community?

While the chief justice exhorted students to share discrimination episodes in answering such questions, recent alum and current student Erika Decklar (Sargent’22, SPH’24) says that may not be comfortable for some. She is an advisor with BU Admissions College Advising Corps (CAC-BU) , which gives college application counseling to low-income and other marginalized high schoolers.

“In my experience,” Decklar says, “students from marginalized backgrounds gravitate towards writing college essays on traumatic experiences, whether they are comfortable sharing these experiences with admissions counselors or not. We have always advised and encouraged students to write about a topic that highlights their strengths, personalities, and passions—whether it is a ‘resiliency’ essay or an essay about their culture, values, or a unique passion.”

After the SCOTUS ruling, Decklar says, her advice to students has not changed. “We should continue motivating students to write about a passion, something that makes them unique, but not coach them to write about their traumatic experiences.”

Katie Hill, who directs CAC-BU, says applicants sharing in their essays what makes them special “does not require them revisiting their pain. If students so choose, we can help them write about their families and cultures, what is beautiful and makes them proud to be” of that culture.

Students from marginalized backgrounds gravitate towards writing college essays on traumatic experiences, whether they are comfortable sharing these experiences with admissions counselors or not. Erika Deklar (Sargent’22, SPH’24)

But what BIPOC (Black, indigenous, people of color) students do not need, Hill says, is to hear from their advisors that in order to get into college, they need to open themselves up beyond their comfortable boundaries.

Walter agrees that an applicant’s story need not be an unrelenting nightmare. It’s true that some of them “are sharing things about their personal lives that I’m not sure I would have seen 20 years ago,” she says. “Students are certainly talking about their sexual identity in their essays. And some will say to us, ‘I’m telling you this [about my identity], and my parents don’t know yet.’”

But she can reel off the opening lines from three of her favorite essays over the years that were hardly gloomy. One began, Geeks come in many varieties. “We laughed. It makes you want to keep reading,” she says. Then there was the woman who started, Life is short, and so am I.

The third: By day, Louis is my trusty companion; by night, my partner in crime. “Doesn’t that make you want to read more and find out who or what Louis is?” Walter asks. (He was the applicant’s first car, a metaphor for this woman’s passion for the independence it conveyed, preparing her for the next step of going to BU, where she indeed matriculated.)

The essay is so important because it’s a given that applicants to BU can manage the academics here. “We have 80,000 students applying for admission to Boston University [annually],” Walter says, “and I think it’s fair to say that the vast majority of them can do the work academically. We’re also shaping and building a class.

“For some, it may be leadership. For some, it may be their cultural background. For others, it might be writing for the Daily Free Press. We really want to think about a wide variety of students in our first-year class.” The essay fills in blanks about applicants for admission, along with teacher and counselor recommendations, their high school activities, and their internships or jobs.

That’s not to say there aren’t lethal don’ts to avoid, most of them emphasizing the necessity of having a proofreader.

“We often get references to ‘Boston College,’” says Patrice Oppliger , a College of Communication assistant professor of communication, who solicits faculty reviews of applicants to COM’s mass communication, advertising, and public relations master’s program before making a decision.

And need we say, do your own work? Walter recalls an essay from a couple of years back where the applicant discussed life in Warren Towers. “And I was like, wait, you couldn’t have lived in Warren Towers, you’re not here yet. And it became very clear that the parent, who was an alum—I think in an effort to help—was telling her story. And somehow no one [in that family] caught that.”

So writing about dealing with discrimination, race-based or otherwise, is fine if it’s not traumatic for you to revisit— and if it’s authentic. Authenticity also includes avoiding over-reliance on artificial intelligence in crafting your essay. According to Admissions’ AI statement ,

If you opt to use these tools at any point while writing your essays, they should only be used to support your original ideas rather than to write your essays in their entirety. As potential future Terriers, we expect all applicants to adhere to the same standards of academic honesty and integrity as our current students. When representing the words or ideas of another in their original work, students should properly credit the source.

“We want to think about not just who will thrive academically at BU,” Walter says, “but also who will enrich the University community and make diverse contributions.”

Explore Related Topics:

- Administration

- Supreme Court

- Share this story

- 1 Comments Add

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There is 1 comment on Should You Discuss Race in Your College Essay?

The resiliency essay is the archetypical admissions essay of our time, but it has its drawbacks: https//www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/11/against-land-acknowledgements-native-american/620820/

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from BU Today

To do today: “i’m right” drag trivia night at roxy’s arcade, should samuel alito and clarence thomas recuse themselves from the supreme court’s insurrection cases, coming soon: waving your phone to ride on the mbta, as drownings surge, fitrec offers swim lessons that could save your life, dive into lgbtq+ pride month with these 12 books, is israel committing genocide in gaza new report from bu school of law’s international human rights clinic lays out case, to do today: check out a boston bollywood dance performance, photos of the month: a look back at may at bu, office artifacts: roz abukasis, celebrating pride month: discover bu’s lgbtqia+ student resource center, a jury found trump guilty. will voters care, to do today: concerts in the courtyard at the boston public library, trump is a convicted felon. does that actually mean anything, what’s hot in music june: new albums, local concerts, proposal to push space junk to “graveyard orbit” earns bu duo first prize in national contest, to do today: chill out at the jimmy fund scooper bowl, six bars to try now that allston’s tavern in the square has shuttered, celebrate pride month with these campus and citywide events, boston’s declining murder rate lowest among big us cities. is it a fluke, donald trump convicted on all 34 counts in hush money trial.

How to Talk About Race on College Applications, According to Admissions Experts

R afael Figueroa, dean of college guidance at Albuquerque Academy, was in the middle of tutoring Native American and Native Hawaiian students on how to write college application essays when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the race-conscious college admissions processes at Harvard and the University of North Carolina are unconstitutional .

Earlier in the week, he told the students that they shouldn’t feel like they need to talk about their ethnicity in their essays. But after the June 29 Supreme Court ruling , he backtracked. “If I told you that you didn’t have to write about your native or cultural identity, you need to get ready to do another supplemental essay” on it or prepare a story that can fit into short answer questions, he says he told them.

For high school seniors of color applying to colleges in the coming years, the essay and short answer sections will take on newfound importance. Chief Justice John Roberts suggested as much when he wrote in his majority opinion, “Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration or otherwise.” That “discussion” is usually in an essay, and many colleges have additional short-answer questions that allow students to expand more on their background and where they grew up.

“The essay is going to take up a lot more space than maybe it has in the past because people are going to be really trying to understand who this person is that is going to come into our community,” says Timothy Fields, senior associate dean of undergraduate admission at Emory University.

Now, college admissions officers are trying to figure out how to advise high schoolers on their application materials to give them the best chance to showcase their background under the new rules, which will no longer allow colleges or universities to use race as an explicit factor in admissions decisions .

Shereem Herndon-Brown, who co-wrote The Black Family’s Guide to College Admissions with Fields, says students of color can convey their racial and ethnic backgrounds by writing about their families and their upbringing. “I’ve worked with students for years who have written amazing essays about how they spend Yom Kippur with their family, which clearly signals to a college that they are Jewish—how they listened to the conversations from their grandfather about escaping parts of Europe… Their international or immigrant story comes through whether it’s from the Holocaust or Croatia or the Ukraine. These are stories that kind of smack colleges in the face about culture.”

“Right now, we’re asking Black and brown kids to smack colleges in the face about being Black and brown,” he continues. “And, admittedly, I am mixed about the necessity to do it. But I think the only way to do it is through writing.”

Read More: The ‘Infamous 96’ Know Firsthand What Happens When Affirmative Action Is Banned

Students of color who are involved in extracurriculars that are related to diversity efforts should talk about those prominently in their college essays, other experts say. Maude Bond, director of college counseling at Cate School in Santa Barbara County, California, cites one recent applicant she counseled who wrote her college essay about an internship with an anti-racism group and how it helped her highlight the experiences of Asian American Pacific Islanders in the area.

Bond also says there are plenty of ways for people of color to emphasize their resilience and describe the character traits they learned from overcoming adversity: “Living in a society where you’re navigating racism every day makes you very compassionate.” she says. “It gives you a different sense of empathy and understanding. Not having the same resources as people that you grow up with makes you more creative and innovative.” These, she argues, are characteristics students should highlight in their personal essays.

Adam Nguyen, a former Columbia University admissions officer who now counsels college applicants via his firm Ivy Link, will also encourage students of color to ask their teachers and college guidance counselors to hint at their race or ethnicity in their recommendation letters. “That’s where they could talk about your racial background,” Nguyen says. “Just because you can’t see what’s written doesn’t mean you can’t influence how or what is said about you.”

Yet as the essay portions of college applications gain more importance, the process of reading applications will take a lot longer, raising the question of whether college admissions offices have enough staffers to get through the applications. “There are not enough admission officers in the industry to read that way,” says Michael Pina, director of admission at the University of Richmond.

That could make it even more difficult for students to get the individual attention required to gain acceptance to the most elite colleges. Multiple college admissions experts say college-bound students will need to apply to a broader range of schools. “You should still apply to those 1% of colleges…but you should think about the places that are producing high-quality graduates that are less selective,” says Pina.

One thing more Black students should consider, Fields argues, is applying to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). (In fact, Fields, a graduate of Morehouse College, claims that may now be “necessary” for some students.) “There’s something to be said, for a Black person to be in a majority environment someplace that they are celebrated, not tolerated,” Fields says. “There’s something to be said about being in an environment where you don’t have to justify why you’re here.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Joe Biden Leads

- TIME100 Most Influential Companies 2024

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Sealed Trump’s Fate : Column

- Are Walking Pads Worth It?

- 15 LGBTQ+ Books to Read for Pride

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at [email protected]

An Essay for Teachers Who Understand Racism Is Real

- Share article

This essay is not to enumerate the recent murders of Black people by police, justify why protest and uprising are important for social change, or remind us why NFL player Colin Kaepernick took a knee. If you have missed those points, blamed victims, or proclaimed “All Lives Matter,” this article is not for you, and you may want to ask yourself whether you should be teaching any children, especially Black children.

This article is for teachers who understand that racism is real, anti-Blackness is real, and state-sanctioned violence, which allows police to kill Black people with impunity, is real. It is for teachers who know change is necessary and want to understand exactly what kind of change we need as a country.

Politicians who know the words “justice” and “equity” only when they want peace in the streets are going to try to persuade us that they are capable of reforming centuries of oppression by changing policies, adding more accountability measures, and removing the “bad apples” from among police.

More From This Author:

“Teachers, We Cannot Go Back to the Way Things Were” “White Teachers Need Anti-Racist Therapy” “How Schools Are ‘Spirit Murdering’ Black and Brown Students” “Dear White Teachers: You Can’t Love Your Black Students If You Don’t Know Them” “‘Grit Is in Our DNA': Why Teaching Grit Is Inherently Anti-Black”

These actions will sound comprehensive and, with time, a solution to injustice. These reforms may even reduce police killings or school suspensions of Black students, but as civil rights activist Ella Baker said, a “reduction of injustice is not the same as freedom.” Reformists want incremental change, but Black lives are being lost with every day we wait. And to be Black is to live in a constant state of exhaustion.

Centuries of Black resistance and protest have had a profound impact on the nation. As Nikole Hannah-Jones, the creator of “The 1619 Project,” points out, “We have helped the country to live up to its founding ideals. ... Without the idealistic, strenuous, and patriotic efforts of Black Americans, our democracy today would most likely look very different—it might not be a democracy at all.” Those civil rights achievements were critical, including the reformist ones.

But reform is no longer enough. Too often, reform is rooted in Whiteness because it appeases White liberals who need to see change but want to maintain their status, power, and supremacy.

Abolition of oppression is needed because reform still did not stop a police officer from putting his knee on George Floyd’s neck in broad daylight for 8 minutes and 46 seconds; it did not stop police from killing Breonna Taylor in her own home. Also that: Largely non-White school districts get $23 billion less in state and local funding than predominantly White ones; Black people make up 13 percent of the U.S. population but account for 26 percent of the deaths from COVID-19; and with only 5 percent of the world’s population, the United States has nearly 25 percent of the world’s prison population. We need to be honest: We cannot reform something this monstrous; we have to abolish it.

Abolitionist Resources From Bettina L. Love

Organizations

- Free Minds, Free People

- Critical Resistance

- Black Youth Project 100

- Quetzal Education Consulting

- Assata’s Daughters

- Black Organizing Project

- Teachers 4 Social Justice

- “Reading Towards Abolition: A Reading List on Policing, Rebellion, and the Criminalization of Blackness”

Abolitionists want to eliminate what is oppressive, not reform it, not reimagine it, but remove oppression by its roots. Abolitionists want to understand the conditions that normalize oppression and uproot those conditions, too. Abolitionists, in the words of scholar and activist Bill Ayers, “demand the impossible” and work to build a world rooted in the possibilities of justice. Abolitionists are not anarchists because, as we eliminate these systems, we want to build conditions that create institutions that are just, loving, equitable, and center Black lives.

Abolitionism is not a social-justice trend. It is a way of life defined by commitment to working toward a humanity where no one is disposable, prisons no longer exist, being Black is not a crime, teachers have high expectations for Black and Brown children, and joy is seen as a foundation of learning.

Abolitionists strive for that reality by fighting for a divestment of law enforcement to redistribute funds to education, housing, jobs, and health care; elimination of high-stakes testing; replacement of watered-down and Eurocentric materials from educational publishers like Pearson, McGraw Hill, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt with community-created standards and curriculum; the end of police presence in schools; employment of Black teachers en masse; hiring of therapists and counselors who believe Black lives matter in schools; destruction of inner-city schools that resemble prisons; and elimination of suspension in favor of restorative justice.

Abolitionist work is hard and demands an indomitable spirit of resistance. As a nation, we saw this spirit in Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass. We also see it in 21st-century abolitionists like Angela Davis, Charlene Carruthers, Erica Meiners, Derecka Purnell, David Stovall, and Farima Pour-Khorshid.

For non-Black people, abolitionism requires giving up the idea of being an “ally” to become a “co-conspirator.” Many social-justice groups have shifted the language to “co-conspirator” because allies work toward something that is mutually beneficial and supportive to all parties. Co-conspirators, in contrast, understand how Whiteness and privilege work in our society and leverage their power, privilege, and resources in solidarity with justice movements to dismantle White supremacy. Co-conspirators function as verbs, not as nouns.

The journey for abolitionists and our co-conspirators is arduous, but we fight for a future that will never need to be reformed again because it was built as just from the beginning.

Related Video

In 2016, Bettina L. Love, the author of this essay, spoke to Education Week about African-American girls and discipline. Here’s what she had to say:

A version of this article appeared in the June 17, 2020 edition of Education Week as For Teachers Who Understand Racism Is Real

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

14 influential essays from Black writers on America's problems with race

- Business leaders are calling for people to reflect on civil rights this Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

- Black literary experts shared their top nonfiction essay and article picks on race.

- The list includes "A Report from Occupied Territory" by James Baldwin.

For many, Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a time of reflection on the life of one of the nation's most prominent civil rights leaders. It's also an important time for people who support racial justice to educate themselves on the experiences of Black people in America.

Business leaders like TIAA CEO Thasunda Duckett Brown and others are encouraging people to reflect on King's life's work, and one way to do that is to read his essays and the work of others dedicated to the same mission he had: racial equity.

Insider asked Black literary and historical experts to share their favorite works of journalism on race by Black authors. Here are the top pieces they recommended everyone read to better understand the quest for Black liberation in America:

An earlier version of this article was published on June 14, 2020.

"Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases" and "The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States" by Ida B. Wells

In 1892, investigative journalist, activist, and NAACP founding member Ida B. Wells began to publish her research on lynching in a pamphlet titled "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases." Three years later, she followed up with more research and detail in "The Red Record."

Shirley Moody-Turner, associate Professor of English and African American Studies at Penn State University recommended everyone read these two texts, saying they hold "many parallels to our own moment."

"In these two pamphlets, Wells exposes the pervasive use of lynching and white mob violence against African American men and women. She discredits the myths used by white mobs to justify the killing of African Americans and exposes Northern and international audiences to the growing racial violence and terror perpetrated against Black people in the South in the years following the Civil War," Moody-Turner told Business Insider.

Read "Southern Horrors" here and "The Red Record" here >>

"On Juneteenth" by Annette Gordon-Reed

In this collection of essays, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annette Gordon-Reed combines memoir and history to help readers understand the complexities out of which Juneteenth was born. She also argues how racial and ethnic hierarchies remain in society today, said Moody-Turner.

"Gordon-Reed invites readers to see Juneteenth as a time to grapple with the complexities of race and enslavement in the US, to re-think our origin stories about race and slavery's central role in the formation of both Texas and the US, and to consider how, as Gordon-Reed so eloquently puts it, 'echoes of the past remain, leaving their traces in the people and events of the present and future.'"

Purchase "On Juneteenth" here>>

"The Case for Reparations" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates, best-selling author and national correspondent for The Atlantic, made waves when he published his 2014 article "The Case for Reparations," in which he called for "collective introspection" on reparations for Black Americans subjected to centuries of racism and violence.

"In his now famed essay for The Atlantic, journalist, author, and essayist, Ta-Nehisi Coates traces how slavery, segregation, and discriminatory racial policies underpin ongoing and systemic economic and racial disparities," Moody-Turner said.

"Coates provides deep historical context punctuated by individual and collective stories that compel us to reconsider the case for reparations," she added.

Read it here>>

"The Idea of America" by Nikole Hannah-Jones and the "1619 Project" by The New York Times

In "The Idea of America," Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones traces America's history from 1619 onward, the year slavery began in the US. She explores how the history of slavery is inseparable from the rise of America's democracy in her essay that's part of The New York Times' larger "1619 Project," which is the outlet's ongoing project created in 2019 to re-examine the impact of slavery in the US.

"In her unflinching look at the legacy of slavery and the underside of American democracy and capitalism, Hannah-Jones asks, 'what if America understood, finally, in this 400th year, that we [Black Americans] have never been the problem but the solution,'" said Moody-Turner, who recommended readers read the whole "1619 Project" as well.

Read "The Idea of America" here and the rest of the "1619 Project here>>

"Many Thousands Gone" by James Baldwin

In "Many Thousands Gone," James Arthur Baldwin, American novelist, playwright, essayist, poet, and activist lays out how white America is not ready to fully recognize Black people as people. It's a must read, according to Jimmy Worthy II, assistant professor of English at The University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

"Baldwin's essay reminds us that in America, the very idea of Black persons conjures an amalgamation of specters, fears, threats, anxieties, guilts, and memories that must be extinguished as part of the labor to forget histories deemed too uncomfortable to remember," Worthy said.

"Letter from a Birmingham Jail" by Martin Luther King Jr.

On April 13 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights activists were arrested after peaceful protest in Birmingham, Alabama. In jail, King penned an open letter about how people have a moral obligation to break unjust laws rather than waiting patiently for legal change. In his essay, he expresses criticism and disappointment in white moderates and white churches, something that's not often focused on in history textbooks, Worthy said.

"King revises the perception of white racists devoted to a vehement status quo to include white moderates whose theories of inevitable racial equality and silence pertaining to racial injustice prolong discriminatory practices," Worthy said.

"The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action" by Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde, African American writer, feminist, womanist, librarian, and civil rights activist asks readers to not be silent on important issues. This short, rousing read is crucial for everyone according to Thomonique Moore, a 2016 graduate of Howard University, founder of Books&Shit book club, and an incoming Masters' candidate at Columbia University's Teacher's College.

"In this essay, Lorde explains to readers the importance of overcoming our fears and speaking out about the injustices that are plaguing us and the people around us. She challenges us to not live our lives in silence, or we risk never changing the things around us," Moore said. Read it here>>

"The First White President" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

This essay from the award-winning journalist's book " We Were Eight Years in Power ," details how Trump, during his presidency, employed the notion of whiteness and white supremacy to pick apart the legacy of the nation's first Black president, Barack Obama.

Moore said it was crucial reading to understand the current political environment we're in.

"Just Walk on By" by Brent Staples

In this essay, Brent Staples, author and Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial writer for The New York Times, hones in on the experience of racism against Black people in public spaces, especially on the role of white women in contributing to the view that Black men are threatening figures.

For Crystal M. Fleming, associate professor of sociology and Africana Studies at SUNY Stony Brook, his essay is especially relevant right now.

"We see the relevance of his critique in the recent incident in New York City, wherein a white woman named Amy Cooper infamously called the police and lied, claiming that a Black man — Christian Cooper — threatened her life in Central Park. Although the experience that Staples describes took place decades ago, the social dynamics have largely remained the same," Fleming told Insider.

"I Was Pregnant and in Crisis. All the Doctors and Nurses Saw Was an Incompetent Black Woman" by Tressie McMillan Cottom

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an author, associate professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and a faculty affiliate at Harvard University's Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. In this essay, Cottom shares her gut-wrenching experience of racism within the healthcare system.

Fleming called this piece an "excellent primer on intersectionality" between racism and sexism, calling Cottom one of the most influential sociologists and writers in the US today. Read it here>>

"A Report from Occupied Territory" by James Baldwin

Baldwin's "A Report from Occupied Territory" was originally published in The Nation in 1966. It takes a hard look at violence against Black people in the US, specifically police brutality.

"Baldwin's work remains essential to understanding the depth and breadth of anti-black racism in our society. This essay — which touches on issues of racialized violence, policing and the role of the law in reproducing inequality — is an absolute must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how much has not changed with regard to police violence and anti-Black racism in our country," Fleming told Insider. Read it here>>

"I'm From Philly. 30 Years Later, I'm Still Trying To Make Sense Of The MOVE Bombing" by Gene Demby

On May 13, 1985, a police helicopter dropped a bomb on the MOVE compound in Philadelphia, which housed members of the MOVE, a black liberation group founded in 1972 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Eleven people, including five children, died in the airstrike. In this essay, Gene Demby, co-host and correspondent for NPR's Code Switch team, tries to wrap his head around the shocking instance of police violence against Black people.

"I would argue that the fact that police were authorized to literally bomb Black citizens in their own homes, in their own country, is directly relevant to current conversations about militarized police and the growing movement to defund and abolish policing," Fleming said. Read it here>>

When you buy through our links, Insider may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more .

- Main content

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Christian Peña Christian Peña

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/how-social-media-is-helping-students-of-color-speak-out-about-racism-on-campus

How social media is helping students of color speak out about racism on campus

Students of color are speaking up about the racial prejudice and scrutiny they encounter in higher education, as part of a national reckoning on racial injustice ignited by the killings of Black Americans like George Floyd by law enforcement and the wave of protests — often led by young people — that followed.

On social media, students are sharing their experiences at predominantly white institutions (PWIs), calling for the end of the implicit and explicit racial biases they face, and demanding accountability from administrators. To some, accountability means sparking discussions about race and the inequalities present in college. For others, it means that students who act in racist ways would face consequences such as suspension, having their Greek organization closed, or even expulsion from the institution.

Thousands of students from colleges and universities with majority white populations have used anonymous Instagram accounts to share their experiences dealing with racism on their respective campuses. Accounts like @dearpwi feature screenshots and videos of students at universities using racial slurs, or engaging in acts of cultural appropriation , such as white college athletes posing as “Mexican” bandits by wearing a sombrero or dressing as a tequila bottle, or posing as “African” men wearing dashikis.

“My family immigrated to the U.S. from an African country […] the professor made jokes to me about how I must be so skinny because in my parent’s country there’s ‘not enough food,’” a student from Haverford College posted on the account .

A student studying at Columbia University posted about often being the only Native American wherever they go. “I’ve always known that in any space I enter, I am oftentimes the first Native American people meet,” the student wrote. “I remember one night eating dinner with a group of friends when one of them said ‘I thought all of your people were dead until I met you.’”

That account alone has more than 190 posts and has amassed 31,000 followers, detailing incidents at nearly 70 universities, including all of the schools in the Ivy League. The @dearpwi account and others, such as various accounts that start with the words “Black at,” are not officially affiliated with any university, and are meant to offer a safe place for those who are dealing with racism in their institutions.

On Twitter, students and professors are using the hashtag #BlackIntheIvory , where they share their successes and their hardships. Users who have embraced the hashtag have shared everything from professional advice, to their thoughts on Black hair and how it often becomes a target of racism.

When students of color face inhospitable or racist environments, they say it makes it more difficult to be themselves. Not only do they have to worry about assignments and grades, but how they’re going to be treated, what resources they will have to be successful and if they’ll be able to fit in.

Thriving academically is challenging without the proper support, which can mean having a faculty that looks like them, or being taught a curriculum that addresses the issues that people of color face daily, students have also said on social media.

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics , some people of color are vastly underrepresented among professors at American institutions: Black males, Black females, Hispanic males and Hispanic females each accounted for 3 percent of the total. Upon moving to college, Mia Hamernik, a senior at the Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, never thought she’d live in a community where everyone else looked different than her. For the California native, who was born to Argentine immigrants, the institution she now calls home is less than 10 percent Latino . Hamernik said her ethnicity and cultural background often leads other students to question her about the color of her skin.

“A student told me it was ‘cool’ that some of my family members were assassinated during the ‘Guerra Sucia,’” said Hamernik. Shocked that a period of state-sponsored violence carried out by the military government would be regarded as “cool,” Hamernik couldn’t help but feel voiceless and unheard among her peers.

“The biggest change I personally experienced was becoming aware of my own identity in the face of countless students who would either ignore my identity or highlight my otherness,” she said.

Maynor Loaisiga, a third-year student, enrolled at Bowdoin College in Maine with the hopes of receiving a rigorous education and full academic support. But he quickly realized the faculty at his university were not representative of the diverse student body. Loaisiga, who was born and raised in Managua, Nicaragua, and migrated to the United States at the age of 11, has been speaking out about issues of social and racial justice since his freshman year and is one of the many students across the United States who are using their voices on social media to bring attention to the pains and hurdles they encounter in college.

In early July, Loasiga submitted a post to the Instagram account @dearbowdoin , calling out his institution. “It is shameful that Bowdoin’s largest academic department only has two professors POC’s,” he wrote. “Do better.”

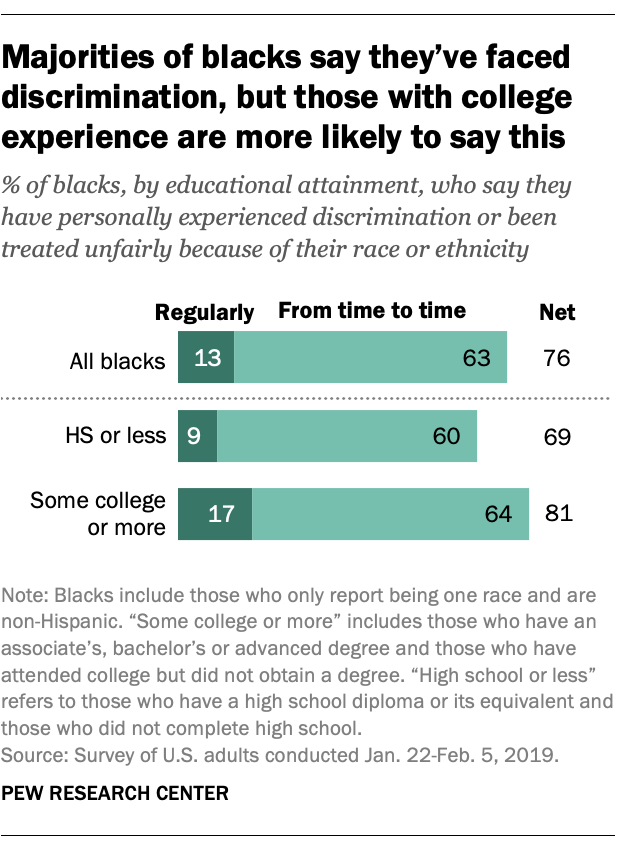

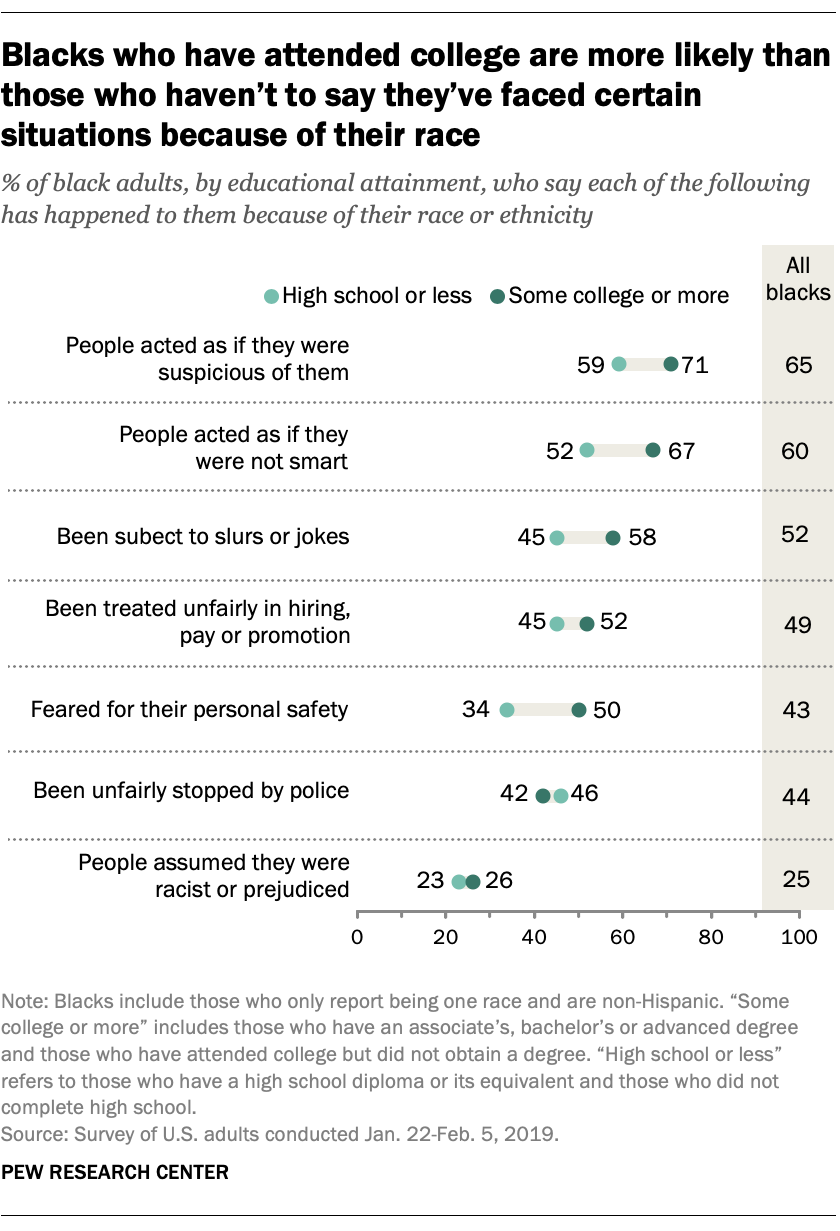

Of the 249 faculty members at Bowdoin College , 17.9 percent are people of color, while students of color make up a third of Bowdown’s student population. According to a 2019 analysis from Pew Research Center, out of all faculty members in the U.S., including adjuncts, 24 percent are non-white . A statement on Bowdoin’s Office of Inclusion and Diversity website says, “Bowdoin is engaged in the deliberate and focused work of identifying where structural racism is embedded in our policies, practices, and everyday operations. We will develop specific plans to address barriers to equity wherever they are found.”

In order to curb feelings of isolation for students of color, inclusivity and diversity must be implemented into college culture and curriculums, said Carole Emberton, author of “ Beyond Redemption: Race Violence, and the American South After the Civil War .” Emberton, who teaches the Civil War and the history of race at the University of Buffalo, argues that tough conversations must take place in the classroom even when faculty members are not prepared to face the challenge.

“We have to work on our pedagogical training and our own outlooks to make sure we’re well equipped to handle these kinds of difficult conversations,” Emberton said. “Students are hungry for the tools to understand and to speak about the world we live in.”

The language of diversity and inclusion has also been amplified on social media and in the news media, fostering more conversations about the insidiousness of systemic racism. While fluency in those concepts may not be a cure-all for racism at universities, for some, it is a step closer to dismantling a culture of oppression.

Ralph Tamakloe, a Black student at the University of Pennsylvania studying electrical engineering, said he has faced microaggressions such as being followed around campus by students, to being asked to show his campus ID by campus police, to having his personal belongings searched in a chemistry lab.

While Tamakloe said he tries to forget about these incidents, he can’t help but reflect and think about how different certain scenarios are for students who do not look like him. In his experience, white people do not face the same stereotypes he does and do not have to worry about being followed around campus because they’re suspected of wrongdoing.

He said he felt that school administrators are dismissive of such incidents. In July, he said, the National Society of Black Engineers at the University of Pennsylvania had a meeting with the School of Engineering’s dean, where they addressed microaggressions that are displayed toward Black students at the institution. According to Tamakloe, the dean listened but didn’t promise any fundamental change. He said he felt like he was being gaslighted.

Vijay Kumar, dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS), said he believes the best way to create an inclusive environment is to change campus behavior rather than punishing individuals who exhibit hurtful behavior, as well as admitting students of color at the same rate as white students.

“The least we can do is to guarantee a level playing field where there’s a rich interaction between students from different” backgrounds, he said about college acceptance rates generally. “We’re not able to do this at this point.”

Kumar said he plans to kick-start a diversity and inclusion campaign this September in which he will individually contact every faculty and staff member to discuss their concerns and possible ideas on how to create an environment that is welcoming for all. The campaign will have mandatory training on anti-racism and unconscious bias for all faculty, staff and students within the engineering school, he added. Every day when Camille Zubrinsky Charles looks at her personal Instagram account, she reads the anonymous stories students of color posted on @blackivystories . Charles, a professor of sociology, Africana studies and education at UPenn, can feel the pain that some anonymous students express, because she once had similar experiences.

“It breaks my heart that they’re having to go through it, because I can still feel what that feels like,” said Charles, co-author of “ Taming the River: Negotiating the Academic, Financial, and Social Currents in Selective Colleges and Universities .” Charles said she believes as an educator into not avoiding discomfort when it comes to teaching race because it reminds students of why they are in college — to become critical thinkers and to be open to alternative points of view. But faculty members have a responsibility to figure out how to navigate appropriate conversations that create a safe environment for marginalized students who have their college experiences minimized, Charles said: “Students have to be reminded that they’re of equal status by the grown-up in the room.”

For now, Tamakloe feels that social media is the only way to hold people and universities accountable.

“Without these [social media] accounts, I think we would have this mentality that schools are just right when they are not,” Tamakloe said.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Racism - List of Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

It is difficult to imagine a more painful topic than racism. Violation of civil rights based on race, racial injustice, and discrimination against African American people are just a small part of issues related to racial inequality in the United States. Such a topical issue was also displayed in the context of school and college education, as students are often asked to write informative and research essays about racial discrimination.

The work on this paper is highly challenging as a student is supposed to study various cruel examples of bad attitudes and consider social questions. One should develop a topic sentence alongside the titles, outline, conclusion for essay on racism. The easiest way is to consult racism essay topics and ideas on our web. Also, we provide an example of a free college essay on racism in America for you to get acquainted with the problem.

Moreover, a hint to writing an excellent essay is good hooks considering the problem. You can find ideas for the thesis statement about racism that may help broaden your comprehension of the theme. It’s crucial to study persuasive and argumentative essay examples about racism in society, as it may help you to compose your paper.

Racism is closer than we think. Unfortunately, this awful social disease is also common for all levels and systems in the US. A student can develop a research paper about systemic racism with the help of the prompts we provide in this section.

Racism in Pop Culture

Emma Watson, Tom Hanks, both names are familiar and quite popular in Hollywood and on television. An emerging actor John Boyega whose name may not be widely known nevertheless impressed the audience with his character Finn from Star Wars. But as popular as these movie actors are, the movie that they all starred in The Circle did not sit well with the audience. In addition to the movie's low rating on film review sites and its abrupt ending that left […]

Appeal to Ethos, Logos and Pathos Racism

Abraham Lincoln once said, Achievement has no color."", but is that really true? In many cases of racism, people have been suppressed and kept from being able to contribute to the society. Racism is a blight and a hindrance to our development. Imagine the many things we could do if people could set aside differences and cooperate meaningfully. Sadly that is not the case. In reality, people are put down because of their heritage and genetics. By no means is […]

Professions for Women by Virginia Woolf

Have you ever asked yourself why people assume something of others by looks? In the chapter, Professions for Women written in 1931 by Virginia Woolf, who talks about her life and the difference she tried to make for all women in that period. She wanted her audience who were professional women to be able to figure out on their own what her story was about. Woolf talks about how she was unmasked and confused as she makes her readers understand […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Racism in Movie “42”

The movie I chose for this assignment is 42 starring Chadwick Boseman and Harrison Ford. The movie is about Jackie Robinson, a baseball player who broke the color barrier when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. One of the topics we covered in this course was racism. For my generation it is hard to understand how pervasive racism used to be in society. I have three cousins that have a black father. Many of my friends are from different races and […]

Racism and the U.S. Criminal Justice System

Introduction The primary purpose of this report is to explore racism issues in the United States justice system and addressing the solutions to the problem affecting the judicial society. Racism entails social practices that give merits explicitly solely to members of certain racial groups. Racism is attributed to three main aspects such as; personal predisposition, ideologies, and cultural racism, which promotes policies and practices that deepen racial discrimination. Institutional racism is also rife in the US justice system. This entails […]

About Black Lives Matter Movement

The fundamental rights and freedoms enshrined in the Constitution are inherent for all. There is no question that all people (blacks, Latinos, Indians, or white) were created free and equal with certain inalienable rights. This is a universally accepted principle. Segregation and racism against minorities in this country have been widely discussed, and prominent figures have taken a stand asking people to join in the fight for equality. This stand addresses the significance of black lives. However, contrasting opinions on […]

Structural Racism in U.S. Medical Care System Doctor-Patient Relationship

US history is littered with instances of racism and it has creeped into not only social, political, and economic structures of society, but also the US healthcare system. Racism is the belief that one race is superior over others, which leads to discrimination and prejudice against people based on their race or ethnicity (Romano). Centuries of racism in the United States' social structures has led to institutionalized or systemic racism”policies and behaviors adapted into our social, economic, and political systems […]

Slavery and Racism in “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is absolutely relating a message to readers about the ills of slavery but this is a complex matter. On the one hand, the only truly good and reliable character is Jim who, a slave, is subhuman. Also, twain wrote this book after slavery had been abolished, therefore, the fact that is significant. There are still several traces of some degree of racism in the novel, including the use of the n word and his tendency […]

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman by Ernest James Gaines

The author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, Ernest J. Gaines, is a male African American author who has taken full advantage of his culture by writing about rural Louisiana. His stories mainly tell the struggles of blacks trying to make a living in racist and discriminating lands. Many of his stories are based on his own family experiences. In Ernest J. Gaines’ novel, The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, four themes that are displayed are the nature of […]

History of Racism

Racism started in the 1700s and has still been occuring till this day. From the looks of it, it seems to be that racism would never end. Because of cultural reasons, stereotypes, and economic reasons, it will always be an issue. People teach their kids to be racist, and make racists comments like it's normal. We can't stop people from having their personal opinions on racism, but we can stay aware of how racists others could be, our history of […]

A Simple Introduction to Three Main Types of Racism

Race plays an important role in both personal and social life, and racial issues are some of the most heated debates in the world due to their complexity, involving the diverse historical and cultural backgrounds of different ethnic groups. Consciously or unconsciously, when one race holds prejudice, discrimination, and a sense of superiority to oppress another race, the issue of racism arises. Based on aspects of individual biases, social institutions, and cultural backgrounds, the three most common types of racism […]

Civil Rights Martyrs

Are you willing to give your life for your people? These martyrs of the civil rights movement gave everything for their people. Although some may say their deaths did not have an impact on the civil rights movements. They risked their lives just so African Americans could have the rights they have today. The definition of martyr is a person who is killed because of their religious or other beliefs. They believe that everyone should be equal and have the […]

Making Racism Obsolete

Does racism still exist? Some would say no?, but some would agree that racism is a cut that won't heal. Molefi Kete Asante is a professor at Temple University and has written many books during his career. In this analysis I will dissect Asante's work covering racism from the past, present and the future moving forward. Asante argues that America is divided between two divisions, the Promise and the Wilderness. Historically, African Americans has been at a disadvantage politically, socially, […]

American Rule in the Philippines and Racism

During our almost 50 years of control in the Philippines, many of our law makers and leaders were fueled by debates at home, and also our presence overseas. These two perspectives gave a lot of controversy as to how Americans were taking control, and confusion of what they were actually doing in the Philippines. Many leaders drew from Anglo- Saxon beliefs, which lead to racist ideas and laws. These combined proved unfair treatment of the Filipinos and large amounts of […]

Social Media’s Role in Perceptions of Racism in the USA

Research studies show that racism has been in existence for centuries. Whether this is still an issue, is the question we must ask ourselves. The internet or, social media has become a major part of society over the years and conveys information, news, opinionated posts, and propaganda, as well. There are several factors involved within this topic and a plethora of resources available in search of the answers. We will look at different opinions, research studies, and ideas in relation […]

The Institutional Racism

In today society there is several police brutality against black people, and it is governed by the behavioral norms which defined the social and political institution that support institutional systems. Black people still experience racism from people who think they are superior, it is a major problem in our society which emerged from history till date and it has influences other people mindset towards each other to live their dreams. In the educational system, staffs face several challenges among black […]

Movie Review of Argo with Regards to Geography

The movie "Crash" is set in a geographical setting which clearly helps in building the major themes of racial discrimination and drug trafficking. This is because the movie is set in Los Angeles which is an area of racial discrimination epitome and partially in Mexico, a geographical area well known for drug trafficking (Schneider, 2014). The physical geographical setting where the movie is shot is very crucial as it helps in developing the main themes of the movie. The movie […]