Case studies in child welfare

About this guide, child welfare case studies, real-life stories, and scenarios, social services and organizational case studies, other case studies, using case studies.

This guide is intended as a supplementary resource for staff at Children's Aid Societies and Indigenous Well-being Agencies. It is not intended as an authority on social work or legal practice, nor is it meant to be representative of all perspectives in child welfare. Staff are encouraged to think critically when reviewing publications and other materials, and to always confirm practice and policy at their agency.

Case studies and real-life stories can be a powerful tool for teaching and learning about child welfare issues and practice applications. This guide provides access to a variety of sources of social work case studies and scenarios, with a specific focus on child welfare and child welfare organizations.

- Real cases project Three case studies, drawn from the New York City Administration for Children's Services. Website also includes teaching guides

- Protective factors in practice vignettes These vignettes illustrate how multiple protective factors support and strengthen families who are experiencing stress. From the National Child Abuse Prevention Month website

- Child welfare case studies and competencies Each of these cases was developed, in partnership, by a faculty representative from an Alabama college or university social work education program and a social worker, with child welfare experience, from the Alabama Department of Human Resources

- Immigration in the child welfare system: Case studies Case studies related to immigrant children and families in the U.S. from the American Bar Association

- White privilege and racism in child welfare scenarios From the Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare more... less... https://web.archive.org/web/20190131213630/https://cascw.umn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/WhitePrivilegeScenarios.pdf

- You decide: Would you remove these children from their families? Interactive piece from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation featuring cases based on real-life situations

- A case study involving complex trauma This case study complements a series of blog posts dedicated to the topic of complex trauma and how children learn to cope with complex trauma

- Fostering and adoption: Case studies Four case studies from Research in Practice (UK)

- Troubled families case studies This document describes how different families in the UK were helped through family intervention projects

- Parenting case studies From of the Pennsylvania Child Welfare Resource Center's training entitled "Understanding Reactive Attachment Disorder"

- Children’s Social Work Matters: Case studies Collections of narratives and case studies

- Race for Results case studies Series of case studies from the Annie E. Casey Foundation looking at ways of addressing racial inequities and supporting better outcomes for racialized children and communities

- Systems of care implementation case studies This report presents case studies that synthesize the findings, strategies, and approaches used by two grant communities to develop a principle-guided approach to child welfare service delivery for children and families more... less... https://web.archive.org/web/20190108153624/https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/ImplementationCaseStudies.pdf

- Child Outcomes Research Consortium: Case studies Case studies from the Child Outcomes Research Consortium, a membership organization in the UK that collects and uses evidence to improve children and young people’s mental health and well-being

- Social work practice with carers: Case studies

- Social Care Institute for Excellence: Case studies

- Learning to address implicit bias towards LGBTQ patients: Case scenarios [2018] more... less... https://web.archive.org/web/20190212165359/https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Implicit-Bias-Guide-2018_Final.pdf

- Using case studies to teach

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2022 11:21 AM

- URL: https://oacas.libguides.com/case-studies

- Conveyancing

- Business Law

A blog for easier living

Child care and protection: 3 real life case studies.

In New South Wales, the law puts the safety, welfare and wellbeing of the children above all else. Government departments such as Family and Community Services (FACS) do not interfere in people’s lives unless children are believed to be at risk of significant harm. If children are removed from your care because they are deemed to be at risk of significant harm, they can be placed with family or emergency carers until the situation has been resolved. If the situation is not resolved, then the children may need to remain in that placement. Parents and guardians have the right to legal aid and will be able to appear in the Children’s Court to work towards having the children restored to their care. The following examples are real case studies from Australia (with names and identifying details changed) to demonstrate how complex child care and protection cases can be.

Case study 1: Thomas & Charlotte A single mother of two children moved in with a partner who has a long criminal history, which included offences against children . There were reports made that the partner was abusing the children. The mother refused to accept that her partner was a risk to the children and prioritised him over the safety, welfare and wellbeing of the children. The children's father was contacted and said he was willing to take care of the children, but he has had little contact with them since the separation.

Response: Concerned about the risk of harm to the children, FACS removed the children and placed them into care and made an application to the Children’s Court to have interim parental responsibility for the children. The mother worked with FACS to address the concerns and was able to have the children restored to her care.

Case study 2: William A child care worker raised concerns about a toddler's late development. The child's mother was contacted and she admitted that she often struggles with her parental duties and relies on stimulants and anti-anxiety medication, but sometimes finds it hard even to get out of bed. Upon further investigation, it was found that the mother was using methamphetamine daily and often leaving the child unsupervised whilst she slept. Response: Her son was temporarily placed into care, but the mother was open to receiving help. She began attending parenting classes and she engaged with drug and alcohol counselling. She also completed random drug screens for FACS to show that she was no longer using illicit substances. She also spoke to her Doctor and obtained assistance for her anxiety. Her son was eventually returned to her care. Case study 3: James A school contacted child protection services when it was concerned about a pupil's poor attendance record, falling asleep in class, arriving without lunch and hygiene issues. When officers visited the child's home, they found that his mother suffered from a number of health problems that made it difficult for her to provide the daily care her son needed. Response: With no close family members available to help out, government support services were contacted to offer financial and emotional support. Care proceedings were not required. Are you worried about your children? If you or a loved one have been separated from your children, you have the right to representation in Children's Court if you can prove that your home is now a safe and caring environment. To find out more about child care and protection in New South Wales and how family lawyers can help you, click the image below to download our free ebook : Care and Protection: Know Your Rights and Where to Get Support.

Never miss an Article

Get the latest articles straight to your inbox, see how our other specialised services can help you:.

Phone: 1300 735 947

Child Protection Forum | Community

Community Child Protection Exchange

Resguardos de Paz – Módulos del proyecto. Guardia Indígena

Published: no date author: war child colombia.

Una historia de resistencia y protección Guardia Indígena. Acciones para la protección comunitaria, defensa de los derechos humanos y construcción de memoria histórica en comunidades indigenas en los departamentos de Choco y Antioquia, Colombia.

A SCHOOL FOR EVERY CHILD! Story of a community-led Initiative against school absenteeism in Jharkhand

Published: 2021 author: the inter-agency core group cini, chetna vikas, child resilience alliance, plan india, & praxis.

A short, illustrated story of a community-led initiative against school absenteeism in Khunti, Jharkhand, India.

Artbooks as witness of everyday resistance: Using art with displaced children living in Johannesburg, South Africa

Published: 2021 author: glynis clacherty.

Artbooks, which are a combined form of picture and story book created using mixed media, can be a simple yet powerful way of supporting children affected by war and displacement to tell their stories. They allow children to work through the creative arts, which protects them from being overwhelmed by difficult memories.

Ficha de situación – Chocó: Quibdó

Published: 2020 author: mire–mecanismo intersectorial de respuesta a emergencias.

Ficha de situación – Chocó: Quibdó. Comunidades de Villa nueva, Wounaan Phoboor y Wounaan la Paz.

Protecting children through village-based Family Support Groups in a post-conflict and refugee setting, Northern Uganda: A Case Study

Published: 2018 author: written by glynis clacherty, edited by lucy hillier, with contributions from mike wessells for the interagency learning initiative (ili).

This case study tells the story of a child protection programme developed by a community-based organisation called Children of the World that works in villages in northern Uganda. The Children of the World programme was chosen for this set of case studies because of its focus on the importance of a personal psychological process for real sustainable child protection.

Truck drivers stand for child protection – The story of the Regional Association of Truck Drivers Against Exploitation of Children, Uganda, Kampala/Mombasa trucking route: A Case Study

This case study tells the story of a regional association set up by truckers to protect children, in particular to stop truck drivers from picking up girls under 18 in the towns along the Uganda section of the Kampala-Mombasa trucking route. It tells the story of some of the truckers who took a stand against sexual exploitation of under-age girls as individuals and how they approached the Uganda Reproductive Health Bureau (URHB) to help them with technical information.

The Tatu Tano child-led organisation – Building child capacity and protective relationships through a child-led organisation, North-western Tanzania

Published: 2018 author: written by glynis clacherty, edited by lucy hillier, with contributions from mike wessells. photographs by james clacherty..

A case study collaboration between the Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) on community-based child protection mechanisms, the Community Child Protection Exchange, and Kwa Wazee, Tanzania.

The story of the Vutamdogo Clubs, Mwanza, Tanzania. Youth clubs run livelihood projects and a literacy programme that provides protection for young children

A case study collaboration between the Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) on community-based child protection mechanisms, the Community Child Protection Exchange, and Tanzanian Home Economics Association (TAHEA).

Weaving the web: documenting community-based development and child protection in Kolwezi, DRC

Published: 2018 author: mark canavera et al. with good shepherd international foundation.

The goal of this document – and the research process that underpins it – is to articulate the model that the Good Shepherd Sisters (GSS) have been implementing in Kolwezi in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By consulting with stakeholders from multiple levels – the Good Shepherd Sisters and their staff, participants in their programmes, community members who are not involved in the programme, government and non-government partners, and mining company representatives – we aimed to document what the Good Shepherd Sisters have been doing in Kolwezi over the past five years with an eye to provide constructive recommendations about the future of the programme, which is currently under review for possible replication in areas around Kolwezi.

Tisser la Toile: documenter l’approche au développement communautaire et protection de l’enfance à Kolwezi, RDC

Published: 2018 author: mark canavera et al. avec good shepherd international foundation.

Le but de ce document et le processus de recherche qui le sous-tend est d’articuler le modèle que les Soeurs du Bon Pasteur (GSS) ont mis en place à Kolwezi en République Démocratique du Congo (RDC). En consultant des intervenants de multiples niveaux les Soeurs du Bon Pasteur et leur personnel, les participants de leurs programmes, les membres de la communauté qui ne participent pas au programme, les partenaires gouvernementaux et non gouvernementaux et les représentants des sociétés minières, nous avons cherché à documenter ce que les Soeurs du Bon Pasteur ont réalisées à Kolwezi au cours des cinq dernières années dans le but de fournir des recommandations constructives sur l’avenir du programme, qui est actuellement en cours de révision pour une réplication possible dans les zones situées autour de Kolwezi.

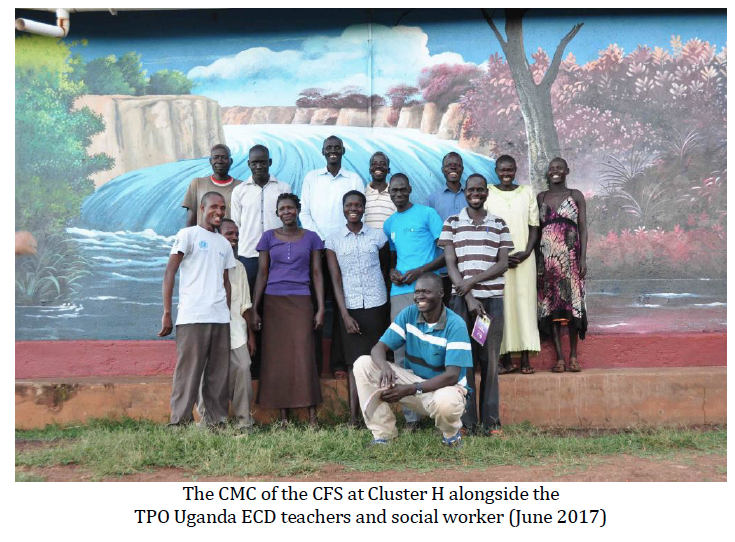

Community Management of Child Friendly Spaces Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement, Uganda. A case study.

Published: 2018 author: clacherty, g. published by the interagency learning intitative on community based child protection, the community child protection exchange and tpo uganda.

A case study collaboration between the Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) on community-based child protection mechanisms, the Community Child Protection Exchange, and TPO Uganda.

Supporting Communities’ Disaster Resilience

Published: 2018 author: global communities.

A cross-sector example from the humanitarian response to disaster affected populations. Global Communities partners with communities to recover after natural disasters by addressing long-term needs and rebuilding climate-resilient infrastructure. It works with communities to strengthen their environmental resilience through climate change adaptation planning and disaster risk mitigation. The approach seeks to empower communities to identify, prioritise and find solutions to their most pressing needs. Haiti, Colombia, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico.

Building cross-sector collaboration using participatory action research to improve community health in an urban slum in Accra, Ghana

Published: 2018 author: jessica kritz.

A cross sector case study. Every urban slum creates challenges too complex for governments to resolve when working alone. Old Fadama, the largest slum in in Accra, Ghana, is home to over 100 000 people. Old Fadama has virtually no water or sanitation infrastructure, contributing to diminished quality of health and frequent cholera outbreaks when the nearby river floods. Our research introduces a model for cross-sector collaboration, supporting stakeholders who wanted to improve community health by installing latrines.

Community-based alternative care as a strategy for protecting Burundian refugee girls and boys: a case study from Mahama camp, Rwanda

Published: 2017 author: plan international.

A case study which describes the community-based child protection programme implemented between 2015 and 2016 with Burundian girls, boys and adults in Mahama refugee camp in Rwanda.

Barefoot Guide 5 – Mission Inclusion

Published: 2017 author: the fifth barefoot guide writer’s collective.

Many organisations, large and small, are tackling the deep challenges of exclusion and coming up with creative, innovative and workable solutions that are putting into practice the policies and strategies that everyone is talking about. This Barefoot Guide, written by 34 practitioners from 16 different countries on all continents makes many of these successful approaches and solutions more visible.

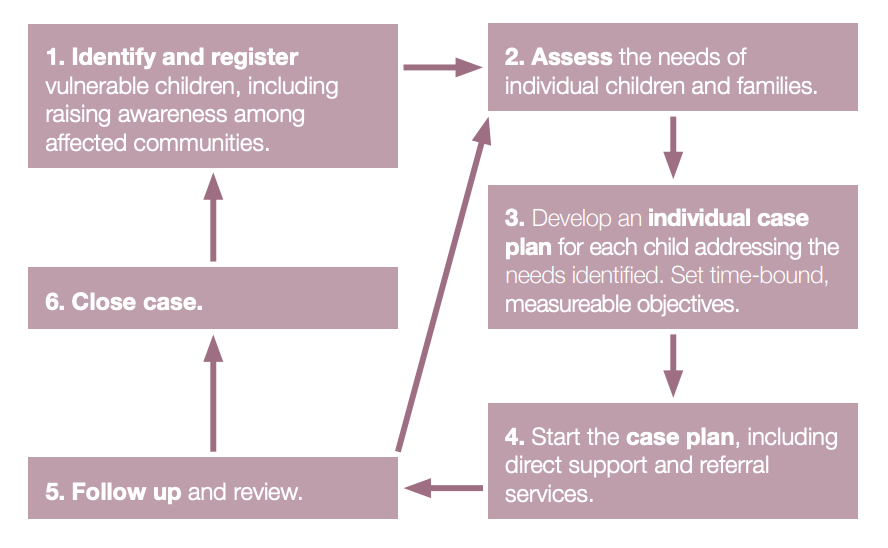

From the ground up: developing a national case management system for highly vulnerable children – An experience in Zimbabwe

Published: 2017 author: n. beth bradford.

A case study from Zimbabwe on how a national case management system for orphans and vulnerable children was built based on a community based care model.

How collaboration, early engagement and collective ownership increase research impact: Strengthening community-based child protection mechanisms in Sierra Leone

Published: 2017 author: michael wessells, david lamin, marie manyeh, dora king, lindsay stark, sarah lilley and kathleen kostelny.

Chapter 5 of the publication “The Social Realities of Knowledge for Development: Sharing Lessons of Improving Development Processes with Evidence” published by the International Development Institute, 2017. Using Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) action research in Sierra Leone, this chapter from a DfiD provides a case study on how a highly collaborative approach can enable child protection research to achieve a significant national impact. The chapter describes how the inter-agency research facilitated a community-driven approach to addressing teenage pregnancy.

Presentation by Eddy Walakira – Kampala workshop, 17-18 August, 2016

Published: 2016 author: eddy walakira.

This presentation looks at the results of a War Child Holland initiative in Northern Uganda around prevention of violence against children in a post war setting.

Presentation by Patrick Onyango – Kampala workshop, 17-18 August, 2016

Published: 2016 author: patrick onyango.

A presentation on girl mothers in armed forces and groups and their children in Northern Uganda, Liberia and Sierra Leone – Participatory Action Research to assess and improve their situations.

Community engagement to strengthen social cohesion and child protection in Chad and Burundi – “Bottom Up” participatory monitoring, planning and action

Published: 2016 author: international institute for child rights and development (iicrd), dr. philip cook, michele cook, natasha blanchet cohen, armel oguniyi & jean sewanou.

A final report on action research which looked at how communities can help drive monitoring, planning and action around social cohesion strengthening and child protection in Chad and Burundi.

Tatu Tano – a portrait

Published: 2015 author: kurt madoerin. kwa wazee.

A background document on the Tatu Tano programme in Nshamba, Tanzania, Developed and implemented by Kwa Wazee.

Tatu Tano – a portrait

Published: 2015 author: kurt madoerin/kwa wazee.

An outline of the Tatu Tano programme and learning from 2015.

An Overview of the Community Driven Intervention To Reduce Teenage Pregnancy in Sierra Leone

Published: 2014 author: mike wessells, david lamin, & marie manyeh.

An overview of the Interagency Learning Initiative process of supporting community-driven action that addresses needs of vulnerable children in Bombali and Moyamba Districts of Sierra Leone.

National Child Protection Systems in the east Asia and Pacific region – a review and analysis of mappings and assessments

Published: 2014 author: ecpat international, plan international, save the children, unicef and world vision - ecpat international, bangkok.

A review of mappings and assessments of the child protection system in 14 countries was commissioned by the Inter-Agency Steering Committee (IASC), a subcommittee of the East Asia and Pacific Child Protection Working Group.

Etude sur les problématiques et les risques de protection de l’enfance – Etude de cas dans la région de Segou, Mali

Published: 2014 author: frédérique boursin-balkouma - sociologue - spécialiste en protection de l’enfant, ouagadougou, burkina faso. nouhoun sidibé - enseignant – chercheur - spécialiste en education, isfra, bamako, mali.

A travers un diagnostic participatif, l’étude commanditée par l’ONG Terre des hommes dans les districts sanitaires de Markala et Macina avait pour objectif d’identifier les problématiques et les risques de protection de l’enfance les plus répandus ; ainsi que de découvrir les pratiques endogènes de protection (PEP) existantes.

Study on the issues and risks for child protection in the Segou region in Mali

A participatory study sponsored by the Terre des Hommes NGO in the health districts of Markala and Macina which aimed to identify the most common risks for child protection as well as existing endogenous protection practices.

Research Brief: An Ethnographic Study of Community-Based Child Protection Mechanisms and their Linkages with the National Child Protection System of Sierra Leone

Published: 2012 author: inter-agency learning initiative on community-based child protection mechanisms and child protection systems.

This document serves as a seven-page summary of the longer report included among these research documents, “An Ethnographic Study of Community-Based Child Protection Mechanisms and their Linkages with the National Child Protection System of Sierra Leone.”

Kwa Wazee’s Impact assessment of Self Defense – the views of the participants

Published: 2011 author: kwa wazee.

A 2011 evaluation of the Kwa Wazee girl’s self-defence training initiative in Nshamba, Tanzania.

Tanzania: Linking community systems to a national model of child protection

Published: 2011 author: sian long, maestral international.

This report describes a child protection system strengthening initiative that was piloted in four districts in Tanzania. The aim of the initiative was to improve the delivery of social and protective services to all children, especially the most vulnerable, with a view towards building an evidence base for an effective child protection model that can be scaled up nationally.

Strengthening National Child Protection Systems in Emergencies through Community-Based Mechanisms: A Discussion Paper

Published: 2010 author: alyson eynon and sarah lilley for save the children uk on behalf of the child protection working group of the un protection cluster.

This discussion paper uses three case studies – Myanmar, the occupied Palestinian territories, and Timor Leste – to examine the state of evidence about strengthening national child protection systems through community-based mechanisms during emergencies.

Executive Summary: What are we learning about protecting children in the community?

Published: 2009 author: mike wessells, lead consultant, on behalf of an inter-agency working group.

This 20-page executive summary presents an overview of the key findings from a 2009 inter-agency review of the evidence on community-based child protection mechanisms. The full report is also available in this research section.

Sudan: An in-depth analysis of the social dynamics of abandonment of FGM/C

Published: 2009 author: samira ahmed, s. al hebshi and b. v. nylund for unicef innocenti research centre.

An Innocenti Working Paper Special Series on Social Norms and Harmful Practices.This paper examines the experience of Sudan by analysing the factors that promote and support the abandonment of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and other harmful social practices. Despite the fact that FGM/C is still widely practiced in all regions of northern Sudan, women’s intention to circumcise their daughters has decreased significantly during the last 16 years. Attitudes are changing and today, actors are mobilizing across the country to end the practice. This paper examines these changes. It analyses programmes that support ending FGM/C in Sudan and highlights the key factors that promote collective abandonment of the practice, including the roles of community dialogue, human rights deliberation, community-led activities, and the powerful force of local rewards and punishment.

A Common Responsibility: The role of community-based groups in protection children from sexual abuse and exploitation – a discussion paper

Published: 2008 author: sarah lilley for save the children uk.

This 2008 discussion paper shares Save the Children’s experience in working with community-based groups; the paper is an effort to stimulate dialogue by highlighting the successes and challenges of such work.

Mobilising Children & Youth into their Own Child- & Youth-led Organisations

Published: 2008 author: kurt madoerin. published by repssi.

Several decades of experience in working with vulnerable children across the planet had resulted in Kurt coming to believe that in the face of family, community and societal disintegration, the single most important supportive “intervention” that could be offered “to”, and more importantly “with” children and youth, might be the mobilisation of children and youth into their own child-led and youth-led organisations.

Community Action and the Test of Time: Learning from Community Experiences and Perceptions

Published: 2006 author: jill donahue and louis mwewa.

Case studies of mobilisation and capacity building to benefit vulnerable children in Malawi and Zambia.

Impact Evaluation of the VSI (Vijana Simama Imara) organisation and the Rafiki Mdogo group of the HUMULIZA orphan project Nshamba, Tanzania

Published: 2005 author: glynis clacherty and professor david donald.

The aims of the Humuliza Project are to develop a practical instrument to enable

teachers and caregivers to support orphans psychologically and to develop the

orphans’ own capacity to cope with the loss of their caretakers.

Latest Addition

A community keeping its children safe, what i’ve learned podcast.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Parenting, childcare and children's services

- Safeguarding and social care for children

- Safeguarding and child protection

- Preventing neglect, abuse and exploitation

Training resources on childhood neglect: family case studies

Case studies for training multi-agency groups on identifying and preventing child neglect.

F1.0: case studies - Evans family

PDF , 198 KB , 1 page

F1.1: Fiona Evans' story

PDF , 183 KB , 1 page

F1.2: Steve Evans' story

PDF , 291 KB , 1 page

F1.3: Liam Evans' story

PDF , 233 KB , 1 page

F1.4: Shireen Evans' story

PDF , 253 KB , 1 page

F1.5: Lewis Evans' story

F1.6: liam evans' history.

PDF , 206 KB , 1 page

F2.0: case studies - Henderson/Miller/Taylor family

PDF , 313 KB , 2 pages

F2.1: Claire Henderson's story

PDF , 277 KB , 1 page

F2.2: Darren Miller's story

PDF , 223 KB , 1 page

F2.3: Michelle Henderson's story

PDF , 255 KB , 1 page

F2.4: Troy Taylor's story

PDF , 241 KB , 1 page

F2.5: Susan Miller's story

PDF , 324 KB , 1 page

F2.6: Michelle Henderson's history

PDF , 288 KB , 1 page

F2.7: Michelle Henderson's chronology

PDF , 303 KB , 2 pages

F2.8: Troy Taylor's history

PDF , 267 KB , 1 page

F3.0: case studies - Akhtar family

PDF , 141 KB , 2 pages

F3.1: Mabina Akhtar's story

PDF , 164 KB , 1 page

F3.2: Saleem Akhtar's story

PDF , 168 KB , 1 page

F3.3: Wasim Akhtar's story

PDF , 152 KB , 1 page

We have developed 3 family case studies to illustrate many of the issues that practitioners are likely to encounter when investigating childhood neglect. The 3 families are:

- Henderson/Taylor/Miller

The case studies provide first person narratives giving the perspective of each adult and child.

Accompanying videos to these case studies are available on our YouTube channel.

The guidance and exercise documents , presentations and notes and handouts that complement these family case studies are also available.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

- Broader Community

- Work With Us

- Transformational Practice

- knowledge-and-research

- therapeutic-application

Ethical Dilemmas in Child Protection Practice: A Tale of Two Stories

This blog article was authored by Vicky Averkiou . Vicky has twelve years experience in child protection. She has been a Casework Specialist since 2010 in various offices and districts.

In NSW, Family and Community Services (FACS), as the statutory child protection agency, has implemented Structured Decision Making (SDM) for much of these decision points. And while SDM tools do much to increase consistency and validity of child protection assessments, they can never take away the human element in making decisions. Nor should they. The catchcry is that people make decisions, not tools. And nowhere is this highlighted more poignantly than in child protection. Their value is as their name implies: structuring, or scaffolding if you will, the information you need in order to make decisions at certain points of our involvement with a family.

In order to support practice, each Community Services Centre (CSC) has access to a Casework Specialist, a senior child protection practitioner who helps increase staff capacity and practice quality through coaching, training, consultation, and quality assurance. As a Casework Specialist, I am most frequently consulted on the application of the SDM tools when assessing safety of and risk to children. So I know all too well the vagaries that can afflict child protection assessments, whether through a misapplication of the tool, a misunderstanding of the definitions, or whether a more serious misconception of the family’s issues. Not that I am implying that decisions are frequently wrong. Just that with families with the most complex difficulties, even the application of standardised tools can similarly become complex and require consideration and, often, consultation.

A tale of two stories

The validity of our assessments are dependent upon the quality of the information we have gathered about a family. And this, in turn, is dependent upon the quality of our engagement with the family, our ability to understand the family’s story and to conceptualise what this means for this child. It takes skill and expertise in order to do this well. What happens when parents’ accounts for events vary with children’s accounts? What about when the most vulnerable children are non-verbal or have limited verbal ability?

It is the unfortunate finding that child protection practitioners tend to believe children over parents only if it fits with their existing views of a family [1] . Sometimes parents’ version of events presented to us is more palatable, less distressing, and does much to assuage our concerns. For if the child’s version of events was true, this truly would challenge all our abilities to make sense of how parents can cause such harm to their children, especially children they genuinely love. How can we reconcile our compassion and sympathy for these parents, who had clearly been disadvantaged by life, with reports of behaviour that was clearly damaging to their child?

“I think you should take me again.”

If we focussed only on the parents’ story, we could become lost in our empathy for them and our assessment of their behaviour become confused with our sympathy for them. This is where it is vital to understand as well as reflect upon the child’s lived experience, what it means for them to live on a daily basis with the legacy of their parents’ difficulties. Just as a trauma-informed perspective can increase compassion for parents who are struggling, so too can it support an understanding that children’s behaviour is a reflection of their environment and their unmet needs. This disallows an unacceptable level of tolerance of parental difficulties when children’s behaviours are particularly difficult [3] . A Casework Specialist can provide both the reflective space as well as an additional, dispassionate perspective that more easily allows for such consideration to take place. For, otherwise, it is too easy for children’s experiences to become lost in the busyness of the day.

I had the opportunity to talk to Jonathan following a child protection report being received while I was conducting my review. This was the fifth report regarding facial bruising to either Jonathan or one of his younger siblings – the fourth to Jonathan himself. Jonathan and his siblings had also been subject to numerous reports of neglect. It was in fact assessed that the developmental delays Jonathan and his siblings experienced were due to the neglect they had experienced throughout their lives. In order to understand Jonathan, I required the assistance of his teacher to help ‘translate’ what he told me. It still amazes what he could say – what he did have language for and what he didn’t. Jonathan was able to clearly say, “Daddy punch”, just as he had three years earlier after sustaining a black eye. His other clearest communication was that he wanted to be removed. He stated, “I think you should take me again”, and then pointed to a picture of a happy face, indicating that this is how he would feel if he was to be removed.

I had to leave Jonathan there at school that day without ‘taking him again’ as he had requested. As a Casework Specialist, I can have influence over decisions, but I cannot make them. I did not doubt that he was unsafe. Jonathan did his best to tell me that. However, the decision was made that Jonathan’s verbal disclosure’s did not provide sufficient clarity that he was currently being harmed and therefore at ‘immediate risk of serious harm’. This was because we could not tell whether he was talking about a recent event or an event in the past. The burden of proof upon FaCS is, in these cases, much more onerous to casework staff to be able to demonstrate to the Children’s Court that the children need to come into care.

I often think back as to how confusing it must have been for Jonathan for us to leave him that day after he told us he was scared and wanted to come into care. He cannot know that I wrote a review report that may have influenced somewhat the decision that saw him ultimately come into care. Not when he came into care several months after I spoke to him. And while I was relieved that Jonathan and his siblings were now safe, this did not mean that their difficulties were over. We know that the care system can be flawed. The availability of carers – kinship or otherwise – who can provide the therapeutic care required to rehabilitate these children from the effects of trauma is severely limited relative to the need. But this cannot be a reason to leave children in unsafe circumstances with their families of origin. For this would be the ultimate ethical dilemma.

[1] Munro (1999; 2008)

[2] e.g. Donald & Jureidini, 2004; Jackson, Frederico, Jones, Walsh & Dounias; Killen, 2008; Siegel, 2008, 2012a; Siegel & Hartzell, 2014; Tarczon, 2012.

[3] Donald & Jureidini (2004).

[4] Names have been changed to protect confidentiality.

If you liked this blog post, you may also be interested in these blogs on similar themes.

The legacy of robin clark.

Robyn Clark provides an on-going inspiration for all who work to promote the rights of and the protection of children in Australia. Here Noel Macnamara reflects on the impact she still has on his own work, and how her legacy might inspire us all.

Stepping Inside the Infant Experience

To be truly attuned to the infant experience it is likely that we best meet the needs of our ‘under twos’, when we access and communicate with, our own right brains writes Jeanette Miller, who here explores myths and misconceptions held around the infant experience.

Practicing Shame Resilience

Shame is a powerful emotion that can have trans-generational effects. It is not easy to talk about, but in this entry by Guest Blogger Andrea Szasz that's exactly what she does, sharing important insights into how we can work with our own shame, and that of clients.

Sign up for our e-newsletters for professionals - bringing regular updates, training opportunities and free resources for your work.

- Name First Last

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Child protection, every child has the right to live free from violence, exploitation and abuse..

- Available in:

Overview | What we do | Reports | Data | News

Children experience insidious forms of violence, exploitation and abuse. It happens in every country, and in the places children should be most protected – their homes, schools and communities. Violence against children can be physical, emotional or sexual. And in many cases, children suffer at the hands of the people they trust.

Children in humanitarian settings are especially vulnerable. During armed conflict, natural disasters and other emergencies, children may be forced to flee their homes, some torn from their families and exposed to exploitation and abuse along the way. They risk injury and death. They may be recruited by armed groups. Especially for girls and women, the threat of gender-based violence soars.

Harmful cultural practices pose another grave risk in various parts of the world. Hundreds of millions of girls have been subjected to child marriage and female genital mutilation – even though both are internationally recognized human rights violations.

No matter the circumstance, every child has the right to be protected from violence. Child protection systems connect children to vital social services and fair justice systems – starting at birth. They provide care to the most vulnerable, including children uprooted by conflict or disaster; victims of child labour or trafficking; and those who live with disabilities or in alternative care. Protecting children means protecting their physical and psychosocial needs to safeguard their futures.

UNICEF works in more than 150 countries to protect children from violence, exploitation and abuse. We partner with governments, businesses, civil society organizations and communities to prevent all forms of violence against children and to support survivors. Our efforts strengthen child protection systems to help children access vital social services, from birth through adolescence.

During a humanitarian crisis, we provide leadership and coordination for all actors involved in the response. Our programming focuses on protecting children from explosive weapons and remnants of war; reunifying separated children with their families; releasing and reintegrating children associated with armed groups; preventing and addressing gender-based violence; and safeguarding children from sexual exploitation and abuse. We also work with United Nations partners to monitor and report grave violations of children’s rights in armed conflict.

Alongside communities, we accelerate the elimination of harmful practices, such as child marriage and female genital mutilation.

We also support governments with policy, legislation and regulatory frameworks that give more children access to social services and justice.

Throughout all we do, we listen to young people to ensure their needs drive our work.

Our programmes

Our strategy

Child Rights Impact Assessments

Developing global guidance

Caring for child survivors of sexual abuse Resource Package

Second edition

Building synergies to address child malnutrition and poverty

UNICEF programming guidance

Meeting Report: 2023 Annual Technical Consultation

UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation: Delivering the Global Promise

Data and insights

Our research

Our insights

Child migration through the Darien Gap up 40 per cent so far this year

On the 10-year mark of the Chibok abductions, UNICEF urges action to secure children's education in Nigeria

Over 230 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to female genital mutilation — UNICEF

Nearly half a million children in Europe and Central Asia live in residential care facilities

Straight from the experts

Breaking news and analysis from UNICEF's Child Protection team.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 17 September 2013

A qualitative case study of child protection issues in the Indian construction industry: investigating the security, health, and interrelated rights of migrant families

- Theresa S Betancourt 1 , 2 ,

- Ashkon Shaahinfar 2 ,

- Sarah E Kellner 2 ,

- Nayana Dhavan 2 &

- Timothy P Williams 2 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 13 , Article number: 858 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

11 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

Many of India’s estimated 40 million migrant workers in the construction industry migrate with their children. Though India is undergoing rapid economic growth, numerous child protection issues remain. Migrant workers and their children face serious threats to their health, safety, and well-being. We examined risk and protective factors influencing the basic rights and protections of children and families living and working at a construction site outside Delhi.

Using case study methods and a rights-based model of child protection, the SAFE model, we triangulated data from in-depth interviews with stakeholders on and near the site (including employees, middlemen, and managers); 14 participants, interviews with child protection and corporate policy experts in greater Delhi (8 participants), and focus group discussions (FGD) with workers (4 FGDs, 25 members) and their children (2 FGDs, 9 members).

Analyses illuminated complex and interrelated stressors characterizing the health and well-being of migrant workers and their children in urban settings. These included limited access to healthcare, few educational opportunities, piecemeal wages, and unsafe or unsanitary living and working conditions. Analyses also identified both protective and potentially dangerous survival strategies, such as child labor, undertaken by migrant families in the face of these challenges.

Conclusions

By exploring the risks faced by migrant workers and their children in the urban construction industry in India, we illustrate the alarming implications for their health, safety, livelihoods, and development. Our findings, illuminated through the SAFE model, call attention to the need for enhanced systems of corporate and government accountability as well as the implementation of holistic child-focused and child-friendly policies and programs in order to ensure the rights and protection of this hyper-mobile, and often invisible, population.

Peer Review reports

In India, there are an estimated 40 million migrant laborers in the construction industry [ 1 ], who together make an immense contribution to the country’s rapidly developing economy [ 2 ]. Many of these laborers are parents who migrate with their young children to work and live in very challenging conditions [ 3 – 5 ]. Despite a broad epidemiological “migration and health” literature [ 6 ] and the documented impact of labor migration on child health [ 7 , 8 ], including explorations of child maltreatment in migrant families [ 9 – 12 ], little research has examined the health, safety, development, and well-being of migrant workers’ children. Using the methodology of a social science case study [ 13 ] conducted at a large construction site in the National Capital Region near Delhi, India, we examine dynamics influencing the security and well-being of migrant children and families who live near and work in infrastructure development projects.

Public health implications of migration for children and families

Migrants worldwide comprise a heterogeneous population that includes more than 214 million international and 740 million internal migrants [ 14 ]. The reasons for migration are diverse: for some, it is necessitated by civil conflict, natural disaster, development, or trafficking; while for others, it is out of desperation to escape profound poverty. The field of public health has traditionally focused on how mobile populations contribute to communicable disease epidemiology e.g. [ 15 ]. There is, however, a growing literature on migration and health, which addresses a variety of topics including: mental health [ 16 ], reproductive health [ 17 ], maternal and child health [ 18 , 19 ], tobacco and substance use [ 20 , 21 ], occupational health [ 22 ], and child abuse and neglect e.g. [ 9 ]. Studies have generally indicated that the drivers of migration, such as socioeconomic status [ 7 , 8 , 23 – 25 ], closely determine migrant health, rather than the process of migration itself. Increasingly, research has highlighted structural and institutional factors that affect migrant health, such as denial of medical care and its relationship to child survival [ 7 ].

Migration has implications for family well-being, including the safety, development, and education of children of migrant workers. Parental absence and struggle for survival have been tied to harmful socio-emotional impacts on children left behind [ 26 – 28 ]. With regards to the education of children of migrant families, researchers have found both positive impacts from remittances [ 29 , 30 ] and negative effects due to lack of parental support and supervision [ 26 , 31 ] as well as disincentivization by the prospect of migration [ 32 ]. Researchers seeking to understand the complex connections between family migration and child abuse have also highlighted poverty and socioeconomic stress [ 9 , 10 , 33 , 34 ], as well as social isolation and lack of social capital [ 11 , 12 , 33 – 35 ]. Frequent mobility has also been correlated with child maltreatment within families [ 36 , 37 ] as well as in neighborhoods and communities [ 38 – 40 ].

Labor migration and construction in India

The drivers and consequences of labor migration in India are as diverse as its regions and peoples [ 41 ]. While rural–urban and interstate migration make up relatively small portions of all migration in India (18% and 13% of 315 million migrants, respectively, per the 2001 census) [ 42 ], rapid development has increased these numbers. By recent trade union estimates, there are approximately 40 million interstate migrants in the construction industry alone [ 1 ]. This group of internal migrant workers, defined in the Interstate Migrant Workmen Act of India as “any person who is recruited by or through a contractor [including middlemen] in one State under an agreement or other arrangement for employment in an establishment in another State”, and their families, comprise the general focus of the present study [ 43 ].

Cyclical migration has long been an important livelihood strategy for the rural poor of India [ 44 , 45 ]. Seasonal climate fluctuations in regions such as the flood-prone Ganges basin and the rain-dependent semi-arid tropics make for agrarian lifestyles fraught with risk and food insecurity [ 4 , 46 , 47 ]. Landlessness and social-deprivation [ 3 , 48 , 49 ], indebtedness [ 4 , 50 ], and limited employment opportunities [ 44 , 49 , 50 ] all drive individuals and families to migrate.

The impact of migration on families and communities varies. While longitudinal field studies in India indicate improved wages and income among migrants over time [ 2 , 48 , 51 ], the most economically and socially-deprived have remained in debt [ 50 , 52 ]. Deshingkar and colleagues summarized their observations in Madhya Pradesh: “…for the poorest groups of migrants, especially unskilled and uneducated Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) who still migrate through agents, or who cannot enter remunerative … work because of discrimination, working conditions and earnings are far from ideal and positive changes in living standards are less certain and slower” [ 2 ]. Though some studies suggest migrants are more able to resist exploitation [ 2 , 51 ], recent reports document illegally low wages and strenuous work hours [ 4 , 53 , 54 ].

An emerging body of literature documents numerous threats to the health and well-being of migrant children in India, including poor living conditions [ 3 – 5 , 54 ], frequent injuries of workers [ 1 , 4 ], poor access to drinking water [ 4 , 5 , 53 ], and sexual violence towards women and children [ 53 , 55 ]. Furthermore, urban migrant laborers have great difficulty accessing government programs otherwise accessible in rural settings, including those for health care and insurance [ 4 , 54 , 55 ], childcare [ 4 , 54 , 56 ], education [ 53 , 56 ], and food rations [ 5 , 53 , 54 ]. However, the interrelated and interdependent relationship of these threats to child health and well-being is often overlooked.

Conceptual framework

A rights-based, holistic model of child security, the SAFE model, provided the conceptual basis for the present study. Situating child protection within the nested social ecologies of families, communities, and the larger political, cultural and historical context, the SAFE model examines interrelatedness among four core domains of children’s basic needs and rights: S afety/freedom from harm; A ccess to basic physiological needs and healthcare; F amily and connection to others; E ducation and economic security [ 57 ]. Of central importance to SAFE is the idea that insecurity in any of these fundamental domains threatens security in the others. The SAFE model posits that in the face of child security threats, children and families demonstrate considerable agency, adopting survival strategies to meet their basic security needs. These survival strategies may take risky forms (with cascading negative effects on other dimensions of child security and well-being) or adaptive forms [ 57 ]. For instance, to overcome family economic insecurity, some families may give their child over to bonded child labor while others may organize workers’ collectives to secure a loan to start a small business. The purpose of the SAFE model is to identify and build on adaptive strategies while also highlighting risky strategies in order to enact preventive interventions, provide alternatives, or end third party manipulation [ 58 ].

Fundamental concepts of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) [ 59 ], such as the evolving capacities of the child and the interdependence and interrelatedness of child rights and basic security needs, are implicit to the SAFE model. The SAFE domains also map onto rights delineated in the CRC, such as the rights to life, survival, and development (e.g., Art. 6); education (Art. 28); health (Art. 24); family connections (e.g. Arts. 9, 20); and protection from violence (Art. 19) as well as various other special protection articles (e.g. Arts. 32–40) [ 59 ].

Case study design and research questions

We applied a case study methodology [ 13 ] to identify factors affecting children’s security and well-being at a construction site in the National Capital Region of India using the SAFE model as a theoretical framework for our data collection. A case study approach has particular utility in addressing the “how” and “why” of contemporary phenomena within their real life contexts [ 13 ]. Furthermore, this approach allowed for an in depth examination of issues related to child protection on a single site and the resulting elucidation of complex phenomena. As with prior applications of the SAFE model e.g. [ 58 ], we specifically sought to illuminate child protection threats facing children in families migrating for work in India’s construction industry with particular attention to the SAFE domains and their interrelatedness. We also sought to identify adaptive and dangerous survival strategies used by migrant families. The study was guided by four research questions: (1) What conditions lead children and families to the site?; (2) What are the security threats facing children at the site as described by children, adults, local community representatives, and child protection stakeholders in the National Capital Region?; (3) How do children and families of the site cope with or respond to security threats and situations of adversity?; (4a) In what ways, if any, do public and private sectors of civil society work to support the security and well-being of migrant children and families on the site?; and (4b) More generally, how do local stakeholders think public and private sectors can promote the security and well-being of migrant children and families, if at all?

Our study methods placed particular emphasis on triangulation of information pertaining to the study site, and included key informant interviews, focus groups discussions, ethnographic observations, and a thorough exploration of relevant peer-reviewed and grey literatures. The research was facilitated by Mobile Crèches, a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Delhi that works with the developer at the construction site to provide an early childhood development-oriented crèche and daycare center to care for migrant children during the work day. Indian law requires the establishment of a crèche at sites with more than 50 women [ 60 ], but the law is rarely implemented [ 61 ] (Table 1 ).

Study sample and recruitment

The research team worked closely with Mobile Crèches to select and recruit study participants. Purposive sampling was used to select participants from the construction company leadership, government, civil society, as well as migrant workers and children living and working at the site. We conducted six focus groups, including: two with female workers (N = 15, median age 26), one with male workers (N = 5, median age 35), one with adult “Malda workers” (described below; N = 5, median age 25), one with young boys (N = 4, median age 11), and one with young girls (N = 5, median age 7). A small group of children and adolescents, who were on the site without their parents, were deemed by the research team in discussion with the host NGO too vulnerable for involvement and were excluded from the study. Each focus group consisted of four to ten people and lasted from one to two hours. We also conducted seven in-depth interviews with providers who work with the children at and near the site (e.g. school teachers and child care providers; see Table 2 ). Six developer and contractor representatives at various levels of leadership and employment as well as a local business owner were also interviewed. In order to locate this case study within a larger political context, we also spoke with eight key informants from the government and international and local NGOs.

Data collection

Primary data were collected in the months of January and July 2010, with additional “member checks” (described below) in January-February 2011. All interviews and focus groups were conducted in Hindi or English by local research assistants trained in research ethics and qualitative interviewing techniques. Working in pairs, one research assistant conducted the interview while the other took detailed field notes. All focus groups were held in the local language (Hindi), and key informant interviews were held in English or Hindi. Focus groups and interview guides were open-ended in nature (e.g., “What problems, if any, do children and families face in this site?”), and interviewers probed to gain further insight into emerging issues. Depending on respondent preference, interviews were recorded digitally or via detailed note-writing. All interview and focus group data were transcribed, de-identified, and stored electronically with access limited to authorized research staff, ensuring participant confidentiality. Local research assistants worked in small teams to make accurate Hindi to English translations. Ethical approval was obtained from both the Human Subjects Committee of the Harvard School of Public Health and a local Community Advisory Board in Delhi. Verbal informed consent and independent child assent was obtained from all participants. Parental consent for their children’s participation was obtained at least one day prior to the child focus groups. Participants were given opportunities to ask the local research team any questions before, during, and after the focus group discussions.

Data analysis

Our method of qualitative data analysis included open coding, category construction, and axial coding to examine relationships between categories consistent with a grounded theory-based analysis [ 62 ] and Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) [ 63 ]. This approach entailed a 4-stage procedure: 1) We first conducted an open-coding process of all data using both SAFE model informed categories as well as findings arising organically from the data. 2) Categories and themes that were most saturated in the data informed the development of a coding scheme, e.g., “poverty”, “access to medical care” “hunger”. 3) To examine reliability, two team members trained in the coding scheme independently coded 10% of transcripts. The code book was refined and reliability testing was repeated until all coding was at 80% reliability. 4) Using the code book, the qualitative dataset was coded in Nvivo 8 [ 64 ], a qualitative data analysis program.

After multiple readings of the data, emergent themes were identified and specific codes representing core themes or phenomena were developed. The codebook underwent several iterations with input from multiple coders, allowing its structure to be refined and adapted over time [ 65 ]. This approach was further supplemented by axial coding [ 62 ] to examine the interrelatedness between key concepts and identify cross-cutting themes. In January-February 2011, members of the research team returned to Delhi to re-contact several study participants and to undertake follow-up interviews and focus group discussions through a validation exercise known as “member checks” [ 66 ] (N = 38 participants).

Factors driving family migration to construction site

The laborers, many from the rural areas of distant states such as Bihar and West Bengal (see Table 3 ), likened their experience as a migrant worker to “going abroad” or living in pardes (foreign land). “ If a person has … everything, then why would they come here in this jungle to live ”, explained one female laborer (age 45). “ [Only] [t]he ones who have some problem or are suffering would come here ”. Most laborers and families came to the construction site through jamadars or thekedars from their village, middlemen hired by contractors to sort out logistics related to recruitment, transport, and, in some cases, on-site accommodation. Others arrived through previously migrated family members or through direct company recruitment. A number of respondents had recently migrated for the first or second time: “ It’s been five days since I arrived here. I have just come from home. Earlier when I was here, I stayed for nine months ”. (female laborer, age 21). Many had spent years in pardes , moving from work site to work site, often in association with the same company. As one male worker described, “ We came here and have stayed here since 1995. And we used to go to our native place and come back. I go once or twice in a year to my village. Again, I come to join the same construction firm ” (age 55). Citing the costs and risks associated with travel, many migrants would visit the village infrequently. One group of male laborers referred to as “Malda workers” work on short-term, 50-day contracts, which permit them to pay off small debts, work in their agricultural “off season”, and return home (typically Malda and Cooch Behar districts of West Bengal) to their families and land regularly. No indication of forced labor, coercion, or human trafficking emerged from our observations or discussions with children and adults.

Frequently cited drivers for migration included the opportunity to “earn and eat”, family indebtedness, limited land ownership, and poor fertility of land in villages. Laborers shared stories of migration to meet basic needs for their families: “ Earlier I was a tailor master in Malda. I owned a shop … but I left the work as my youngest daughter was sick. I have spent so much money on her treatment … I was running out of money ” (male supervising laborer). One mother explained, “ We have three children two boys and one girl. We have a house that is made up of mud that is falling down. With the thought to re-build our house and to educate my children we have come here ” (age 25). Another described how her family was compelled to migrate, “ I do not have fields, and there are no rains. In the village, we were dying from hunger and thirst, so we have left children there and have come only with one son to work here on this site ”. (age 30). Still, others cited their intent to help secure a better life for their children. A female migrant (age 22) explained, “ We are poor. We are taking care of, raising our children … to make them move forward, we are earning money. If we educate our children, we will make them into something ”. All of the women in our focus groups were parents; two-thirds of these mothers had children living with them and their husbands on the site, nearly half of whom also had children living with grandparents in the village.

Safety and freedom from harm at the construction site

Displayed prominently at the entrance of the construction site was a sign that read, “ Parents must warn children that this is an unsafe area ”. Large machinery, moving vehicles, and precariously-situated construction materials were ever-present on the site. Children, in particular, expressed worry about their parents’ safety. They recalled incidents that had occurred at other sites where children or workers had been severely hurt or killed, resulting in a preoccupation with the safety of their parents: “ When people work in this site … [they] climb from a rope … then they fall, then people die” , said a girl, age 8. In fact, between July 2010 and January 2011, two workers had died in falls on the worksite.

Access to basic physiological needs: housing, food insecurity and accessing medical care

Living conditions & basic amenities.

Workers and their families lived in cramped, temporary structures, termed jhuggis, made of either corrugated tin or brick and mortar. During the course of our fieldwork, entire portions of the housing area were destroyed and moved due to expanding construction on the site. Many families spent their day off rebuilding or tending to their shelters, a time-consuming and labor-intensive task. While the site manager cited the danger electricity would pose in the tin jhuggis , the lack of electricity for fans or other cooling systems proved especially burdensome and potentially dangerous given high humidity and temperatures exceeding 100°F in the summer months: “ Poor people come from far off and feel so hot here. We stay inside and are drenched in sweat, but still they do not provide us with any electricity… ” (female worker, age 35). To cope with the extreme heat, particularly when the crèche was closed, children would spend time in half-built, multi-story towers where, as one boy (age 12) put it, “ winds … [give] people a calm and cool situation” . Unsupervised, they were placed at risk of falling from the towers or being injured.

The quality and availability of basic amenities, including housing, access to drinking water, affordable food, and proper sanitation were also of primary concern to participants. Many children expressed nostalgia for their village life, citing the heat, cramped jhuggis , and lack of open space. One girl (age 7) insisted, “ Everyone, boys and girls, says it is better back home ”. Although workers were generally satisfied with the availability of clean water, some reported conflicts over communal pipelines. Food was also readily available near the site; however, given their lack of access to ration cards and the high price of food around Delhi, some migrants struggled to afford food and needed to purchase it from the grocery shop owner, or lala, on credit. Sanitation at the site was observed to be poor, with latrines that were often full and seldom cleaned. The lack of separate facilities for men and women was distressing for female workers. Despite these various concerns, the multiple layers of accountability and relative powerlessness of workers meant change was unlikely; as one man (age 55) lamented, “ We cannot do anything. If we will ask, we will be kicked out of this place ”.

Health & healthcare

Many migrate to a worksite in hopes of improving family well-being; yet the health challenges they encounter in pursuing this survival strategy may put children and families at further peril. Respondents familiar with the site described health issues ranging from water-borne and other infectious diseases to heat-exhaustion, dehydration and other work-related problems. Unresolved malnutrition and anemia were both common among children [ 67 ]. While the crèche offered some medical support for children and their families, there were divergent opinions about whether the company or contractors provided care for workers’ children. One male worker (age 35) asserted that there was “ [n]othing for the children ” and that “ the facilities are only for the workers ”. Conversely, a supervisor for a sub-contractor claimed that their facilities were available to both workers and their families. Options for workers themselves were also limited as employers only took responsibility for provision of, transportation to, and payment for care related to work place injury or illness. Basic first aid was provided on the construction site and in the crèche, and an ambulance was reportedly available around the clock. However, in case of off-duty health problems among workers or of more serious injuries or illnesses among children, workers and families had to seek off-site care and pay out of pocket. Informed choice of providers was uncommon, and many participants reported going to informal practitioners of herbal and other alternative medicine as well as unlicensed providers without any medical background in the nearby market. One female worker (age 25) lamented, “ Here there are doctors, some are good and some are bad … there is no fixed doctor, so what do we do? [When we’re] in trouble, we have to go back to our village ”. Primary care services, such as adult health screening, mental health services, and chronic disease management, did not appear readily available.

The costs of paying for healthcare, medications, and other associated expenses (e.g. transportation) were a resounding concern among workers. As one woman (age 35) explained, “ If [the doctor] gives us two injections, it costs us Rs.200 [$4.45 USD]. We are already in so much debt, and if we are not well, how would we go to work? ” Missed work meant lost wages for ill workers, posing additional risk to their families. To save time, many visited private hospitals rather than seek the largely free services at a government hospital, which was reportedly farther away. By law, the contractors are responsible for covering costs of work-related injuries; however, as a manager with the development company admitted, “…not everyone gets to take advantage of the contractor all risk policy because migrants are … a floating population and are not necessarily recognized by the contractor ”. Similarly, due to barriers to registering as local labor welfare board beneficiaries or obtaining documentation of Below Poverty Line (BPL) status, very few workers had access to locally-implemented health insurance schemes intended to provide financial assistance for hospitalizations and chronic care. Thus, in the face of high healthcare costs, workers often turned to their jamadars or thekadars for loans and accompaniment to medical care, adding potentially substantial debt which could force them to extend their work or contract periods.

Family and connection to others: limited monitoring and constant pressure

Construction work meant that many parents were spending long hours without direct capacity to monitor their young children at the site, which became additionally challenging without the presence of extended family. The existence of a functioning crèche at the site greatly mitigated some of the risks due to parental inability to monitor their children. According to both male and female laborers, sexual violence was of diminishing concern. This may be linked to a trend towards leaving school age girls with extended family in the village. One crèche staff member reflected on this survival strategy: “ I saw that earlier young girls [migrated] with their parents, but many crimes occurred like assault … When they went back to their village, they talked about these problems, and awareness increased. Now they leave their young girls at their home” . Issues of family conflict arose infrequently in focus groups and interviews. However, the use of alcohol, and cramped living spaces, were both mentioned as linked to domestic and intimate partner violence. A local teacher, who noted that children were at times reluctant to go home due to violence, reflected on these factors: “ Society demands certain things from kids, and parents have zero economic power. Sometimes they beat kids and women when children ask for their needs to be met”. Child labor was also a seldom-raised topic, but in addition to the adolescent Malda workers and a few teenage children working on the site with their parents, a number of children worked at the worksite canteen, businesses in the nearby market, and in rag-picking in exchange for food and shelter. These children were some of the most vulnerable in this site. We were unable to interview these children and adolescents without being observed by their supervisors and were unable to obtain parental consent given limited information about their family members.

Education and economic security: looking to the future

Children at the site faced numerous barriers to education and learning due to issues of distance, expense, lack of documentation, and frequent movement. A few older boys and one girl were able to attend a nearby private school due to reduced-payment options that were offered for children of migrant workers. However, the nearest government school was far away and across a busy highway. While a few children did attend, responses suggested it was too dangerous to access for many children at this site, thus impeding their right to universal primary education [ 68 ]. Speaking to the de facto discrimination faced by migrant children without residency documentation, the manager of a development company explained, “Although the schools don’t have official rules against [migrant] children, they are not willing to admit children who do not have some degree of permanency”. Even when a child was able to enroll in school, a wide range of obstacles hindered learning, including: the lack of electricity and thus lighting in the jhuggis, a generally poor study environment at home, inability to afford or access tutors, as well as domestic responsibilities that led to school absenteeism. As a local teacher at a private school observed, “ Our kids who are migrants, they really struggle. They have a really difficult time because they compare themselves to [non-migrant] kids ”. These prevailing concerns around education were tied to most parents’ decision to leave their school-aged children (particularly girls) with extended family in the village, allowing uninterrupted schooling. As one man (age 35) asserted, “ We cannot keep our children here; otherwise their education will spoil ”. Not surprisingly, most school-age children on the site were not in school. Apparently having no other safe place to go, many spent their days in the crèche.

Work & wages

Financial concerns were at the forefront of discussion for adult migrant workers. Despite the site manager’s assurance that workers “ do not express concern over wages ”, construction workers told a story of working extended hours for low, piecemeal wages and having only every other Sunday off. Malda workers instead received payment in advance of their 50-day contract period and had no days off. Many workers claimed that payments for piecemeal work and other wages could be delayed, even for months, although not universally reported. However, workers did commonly describe an improvement in wages and financial circumstances relative to opportunities in the village. Nonetheless, many workers, particularly unskilled laborers, were still struggling to provide for their families, much less to save earnings. As one mother (age 35) explained, “ We have to take care of the whole family; we came here to save money. If he would increase the rate, we would save a little. The amount we earn goes to eating ”. In response to these difficulties, delayed payments, and other unexpected costs, respondents reported borrowing money from family, friends, coworkers, or their jamadars or thekadars . Parents also worked overtime to provide for and meet the basic needs of their families. In contrast to other sites, where participants described that women are generally subject to reprimands and deductions in wages for breastfeeding, this site was notably sensitive to the needs of breastfeeding mothers, and women did not report difficulty feeding their infants. Yet, given that the law allows only two nursing breaks per day The Maternity Benefits Act, [ 69 ], section 11, crèche employees needed to provide supplemental formula feeding. Meanwhile, a number of children in the crèche were being monitored for mild and moderate malnutrition and were provided with nutritional supplements.

Protective processes

A sense of community solidarity, social support, and the presence of the crèche were all important sources of risk mitigation and protection at the site. Despite difficulties with wages, living conditions, health care, and access to other services, conflicts among workers did not appear to be common or significant. A crèche employee observed that workers “… become friends and … live like brothers and sisters ”. With many workers living together in “lanes” based on their language and region of origin, communal living also appeared to transcend some of the tension that could otherwise arise from differences in origin, caste, and religion. As one female worker (age 33) explained, “ We are all laborers and live together with each other happily. Every one helps each other ”. Although relationships among migrants were often brief, workers were able to rely upon their community support by turning to one another in times of need. A few respondents suggested their personal sense of faith by invoking God’s role in protecting their children or allowing their family’s success, representing an emergent and preliminary theme.

The crèche also served a protective role that had broader implications for families. One of its primary functions was to provide a safe and caring environment for children during the day, allowing both mothers and fathers to work. As one mother (age 22) noted, “ [Without] such a service or facility, where would we have left our children? Children would come after us to the site … How would we earn our livelihood then? ” The crèche provided basic health care services and regular doctor visits (including growth-monitoring, immunizations, and de-worming), meals to children during the day, and informational sessions for parents on issues like school enrollment. Although not designed to replace school, it also provided younger children an opportunity to develop cognitive, motor, and language skills as well as classroom discipline important for school readiness. The crèche also served to free older siblings from the task of childrearing. The crèche was a safe, child-friendly haven in an otherwise harsh physical environment, in utter contrast to most construction sites, where, as one key informant described, “ the young child is invariably either left alone, unattended, or in the care of siblings … [and] the implications for a child’s development can easily be gauged” . The NGO also worked to mainstream older children into local schools and to encourage provision of basic amenities at this site.

Invisible children, invisible families: the key informant perspective

Our key informants from government agencies and non-governmental organizations reflected upon a scenario in which vulnerable and hyper-mobile migrant families are surrounded by the complex layers of accountability of a rapidly expanding Indian economy. Grappling with the confluence of challenges facing migrant workers and their children, our respondents emphasized the obligations of local and national governments as well as corporations towards the fulfillment of the rights of this marginalized and often “invisible” population.