Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Examining the duality of Israel

One way to help big groups of students? Volunteer tutors.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Bridget Long, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, addresses the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in the field of education.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Post-pandemic challenges for schools

Harvard Staff Writer

Ed School dean says flexibility, more hours key to avoid learning loss

With the closing of schools, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many of the injustices facing schoolchildren across the country, from inadequate internet access to housing instability to food insecurity. The Gazette interviewed Bridget Long, A.M. ’97, Ph.D. ’00, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Saris Professor of Education and Economics, regarding her views on the impact the public health crisis has had on schools, the lessons learned from the pandemic, and the challenges ahead.

Bridget Long

GAZETTE: The pandemic exposed many inequities that already existed in the education landscape. Which ones concern you the most?

LONG: Persistent inequities in education have always been a concern, but with the speed and magnitude of the changes brought on by the pandemic, it underscored several major problems. First of all, we often think about education as being solely an academic enterprise, but our schools really do so much more. Immediately, we saw children and families struggling with basic needs, such as access to food and health care, which our schools provide but all of a sudden were removed. We also shifted our focus, once we had to be in lockdown, to the differences in students’ home environments, whether it was lack of access to technology and the other commitments and demands on their time in terms of family situations, space, basic needs, and so forth. The focus had to shift from leveling the playing field within school or within college to instead what are the differences in inequities inside students’ homes and neighborhoods and the differences in the quality and rigor and supports available to students of different backgrounds. All of this was just exacerbated with the pandemic. There are concerns about learning loss and how that will vary across different income groups, communities, and neighborhoods. But there are also concerns about trauma and the mental health strain of the pandemic and how the strain of racial injustice and political turmoil has also been experienced — no doubt differently by different parts of population. And all of that has impacted students’ well-being and academic performance. The inequities we have long seen have become worse this year.

GAZETTE: Now that those inequities have been exposed, what can leaders in education do to navigate those issues? Are there any specific lessons learned?

LONG: Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet. The solution depends on the individual, the community, and the classroom.

At first, the public health crisis underscored that we needed to meet students where they are. This has been a long-held lesson among experienced education professionals, but it became even more important. In many respects, it butted up against some of our systems, which tried to come up with across-the-board approaches when instead what we needed was a bit of nimbleness depending on the context of the particular school or classroom and the individual needs of students.

Where you have seen some success and progress is where principals and teachers have been proactive and creative in how they can meet the needs of their students. What’s underneath all of this, regardless of whether we’re face-to-face or on technology, is the importance of people and personal connections. Education is a labor-intensive industry. Technology can help us in many respects to supplement or complement what we do, but the key has always been individual personal connection. Some teachers have been able to connect with their students, whether by phone or on Zoom, or schools, where they put concerted effort into doing outreach in the community to check on families to make sure they had basic needs. Some schools were able to understand what challenges their students were facing and were somewhat flexible and proactive to address those challenges, especially if they already had strong parental engagement. That’s where you have continued to see progress and growth.

“In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before.”

GAZETTE: You spoke about concerns about learning loss. What can we do to avoid a lost year?

LONG: One of the difficulties is that the experience has differed tremendously. For some students, their parents have been able to supplement or their schools have been able to react. The hope is that they will not lose much learning time, while other students effectively haven’t been in school for almost a year; they have lost quite a bit of ground. As a teacher, you can imagine your students come back to school, and all of a sudden, students of the same chronological age are actually in very different places, depending on their individual family situation and what accommodations were able to be made. I think there’s a great deal we can do to try to address that. First of all, we have to have some understanding of what gains students have made as well as things they haven’t learned yet. That means taking a moment to see where a student is in their learning. The second thing is to make sure we’re capturing the lessons learned from this pandemic by identifying places where teachers and schools used a combination of technology, outreach, personal instruction, and tutors and mentors, and helped students make progress in their learning. We need to share those lessons more broadly so that other districts can see examples that have worked.

As we look ahead, I think it will take extending learning time to close the gaps. Schools will have to decide whether that is after school, weekends, or summer, and whether or not that’s going to involve the teachers themselves, or if it’s going to be using the best tools that are out there, such as videos and technology platforms that students and families use themselves. There has already been talk by some districts of extending the school year into summer or having summer-camp-type programs to give students additional time to work through some of the material.

The other important piece is partnerships. Schools oftentimes work with members of the community or nonprofit organizations, and that’s a really important layer in our system. After-school programs, enrichment programs, tutors, and mentors are essential, and we really want to continue with that expanded sense of capacity and partnership. It’s going to have an impact on all of us if we lose a generation, or if this generation goes backwards in terms of their learning. It certainly is in all of our best interests to try to contribute to the solution.

GAZETTE: Many parents gained renewed appreciation of the work teachers do. Do you think the pandemic would lead to a reappraisal of the profession?

LONG: Certainly, in the beginning, there was so much more appreciation for what teachers do. As parents needed to start doing homeschooling, there was a new understanding of just how difficult teaching is. Imagine having a classroom with different personalities, different strengths and assets, and also different weaknesses, and somehow being nimble enough to continue that class moving forward. As time has gone on, I worry a little bit about the level of contentiousness in some communities as schools haven’t reopened. There is the balancing act between caring for children’s learning and the fact that we have to make sure that the adults are safe and supported. You hear stories of teachers trying to teach from home while they are also homeschooling their own children. I would hope that coming out of this would be an appreciation of the amazing things teachers do in the classroom, as well as also some acknowledgement that these are people who are also living through a devastating pandemic with all the stress and strain that every individual is going through.

One other point is that given that we know that teachers do more than just academics, we need to make sure our teachers are trained to be able to provide social emotional support to students. As some of the students come back into the classroom, we need to acknowledge that they may be dealing with devastating losses, or the frustration of being kept inside, or the violence that is happening in their homes and neighborhoods. It’s very hard to learn if you’re first dealing with those kinds of issues. Our teachers already do so much, and we need to support them more and provide even more training to help them address that wide-ranging set of challenges their students may be facing even before they can get to the learning part.

“Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet.”

GAZETTE: Are there any silver linings in education brought on by the pandemic?

LONG: The first one is when we all needed to pivot last spring, and especially this fall, many educators took a moment to pause and reflect on their learning goals and priorities. There was a great deal of discussion, both in K‒12 and higher education, to think carefully and deliberately about the ways in which we could make sure our teaching was engaging and active and how we could bring in different voices and perspectives. In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before. The second silver lining is the innovation and creativity. Because there wasn’t necessarily one right answer, you saw a lot of experimentation. We have seen an explosion of different approaches to teaching, and many more people got involved in that process, not just some small 10 percent of the teaching force. We’ve identified new ways of engaging with our students, and we’ve also increased the capacity of our educators to be able to deliver new ways of engagement. From this process, my hope is that we’ll walk away with even more tools and approaches to how we engage our students, so that we can then make choices about what to do face-to-face, how to use technology, and what to do in more of an asynchronous sort of way. But key to this is being able to share those lessons learned with others, how you were able to still maintain connection, how you were better able to teach certain material, and perhaps even build better relationships with parents and families during this process. Just the innovation, experimentation, and growth of instructors in many places has been very positive in so many respects.

GAZETTE: In which ways do you think the education system should be transformed after this year? How should it be rebuilt?

LONG: First, we’ve all had to understand that education and schools are not a spot on a map. They are actually communities; they have to include families, nonprofit organizations, and community-based organizations. For a university in particular, it’s not just about coming to campus; it’s actually about the people coming together, and how they are involved in learning from each other. It’s great to push on this reconceptualization and to be clear that education is an exchange of information, of perspective, of content, and making connections, regardless of the age of the student. The crisis has also forced us to go back to some of the fundamentals of what do we need students to learn, and how are we going to accomplish those goals. That has been a very important discussion for education. And the third part is realizing that education is not a one-size-fits-all. The best educators use multiple methods and approaches to be able to connect with their students, to be able to present material, and to provide support. That’s always been the case. How do we meet students where they are? That framing is one that I hope will not go away because all students have the potential to learn, and it’s a matter of how to personalize the learning experience to meet their needs, how we notice and provide supports to help learners who are struggling. That really is at the core of education, and I hope that we will take away that lesson as we look ahead.

GAZETTE: What do you think the role of higher education should be in this new educational landscape?

LONG: Higher education has an incredibly important role, and in particular given the economic recession. Traditionally, this is when many more people go into higher education to learn new skills, given what’s happening in the labor market. We have yet to see what the long-term impact is going to be, but in the short term, one thing we’ve noticed is that college enrollments are down. That’s very alarming and may have to do with how suddenly and how quickly the pandemic affected society. The first thing that higher education is going to have to think about is increasing proactive outreach — how to connect with potential students and how to help them get into programs that are going to give them skills necessary for this changing economy. Unfortunately, they’ll be doing this in a context where students are going to have greater needs, and where it’s not quite clear if funding from state and local governments is going to be declining. That’s the challenge that higher education will have to face. While it’s an amazing instrument in helping individuals further their skills or retool their skills, we need to make investments and make sure individuals can actually access the training available in our colleges and universities.

More like this

With revamped master’s program, School of Education faces fresh challenges

Seeded amid the many surprises of COVID times, some unexpected positives

Dental students fill the gap in online learning

GAZETTE: What are your hopes for the Biden administration in the area of education?

LONG: Government has a very important role in education, but it has to be balanced with the importance of local control and the fact that the context of every community is slightly different. Certainly, as we’ve been in the middle of a public health crisis, this has been incredibly challenging for schools. Schools had been trying to continue providing food and health care and connect with their students and, all of a sudden, they had to become experts in public health and buildings. This is something that falls under the purview of the federal government. Having access to the best doctors, the best public health officials, and people who think about buildings, and how to make things safe, the government needs to put that information together to give guidance to schools, principals, and teachers. It’s the government that can say, “Here are the risks, and here are the things you can do to mitigate those risks. Here are the conditions that are necessary for buildings. Here is what we know in terms of preventing spread, and here is what we know about the impact on children of different ages, and how we can protect the adults.” That kind of guidance would be incredibly helpful, as you have all of these individual school districts trying to sort through complex information and what the science says and how it applies to their particular context. Guidance is No. 1.

No. 2 is data. It’s very important having some understanding about where we stand in terms of learning loss, what we need to prioritize, and what areas of the country perhaps need more help than others. The other key component is to gauge what lessons have been learned and share the best practices across all school districts. The idea is to use the federal government as a central information bank with proactive outreach to schools. Government also plays a critical role in funding the research that will document the lessons from this pandemic.

It’s going to be incredibly helpful to have a more active federal government. As we have a better sense about where our students are the most vulnerable, and what are the kinds of high-impact practices that would be most beneficial, it’s going to be critical having the funding to support those kinds of investments because they will most certainly pay off. That possibility, I’m much more optimistic about now.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity

Share this article

You might like.

Expert in law, ethics traces history, increasing polarization, steps to bolster democratic process

Research finds low-cost, online program yields significant results

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

Women who follow Mediterranean diet live longer

Large study shows benefits against cancer, cardiovascular mortality, also identifies likely biological drivers of better health

Harvard-led study IDs statin that may block pathway to some cancers

Cholesterol-lowering drug suppresses chronic inflammation that creates dangerous cascade

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Education in a post-covid world, towards a rapid transformation.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, resulting in disruptions to education at an unprecedented scale. In response to the urgent need to recover learning losses, countries worldwide have taken RAPID actions to: R each every child and keep them in school; A ssess learning levels regularly; P rioritize teaching the fundamentals; I ncrease the efficiency of instruction; and D evelop psychosocial health and wellbeing.

Marking three years since the onset of the pandemic, this report looks back at policy measures taken during school closures and reopening based on country survey data, initiatives implemented by countries and regions to recover and accelerate learning, and their emerging lessons within each RAPID action. With schools now reopened worldwide, this report also looks ahead to longer-term education transformation, offering policy recommendations to build more resilient, effective and equitable education systems.

Files available for download

Related topics, more to explore.

1 in 4 children globally live in severe child food poverty due to inequity, conflict, and climate crises – UNICEF

Youth from 57 island states call for urgent climate action

Children and youth demand attention on critical issues at the SIDS Summit

Sudan’s children trapped in critical malnutrition crisis, warn UN agencies

UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador Millie Bobby Brown calls for ‘a world where periods don’t hold us back’ in new video for Menstrual Hygiene Day

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021

THE CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended.

Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning.

It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake.

THE MISSION

Mission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs.

Timeframe : By end 2021.

Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs.

Three priorities:

1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs.

Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school.

Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs.

Targets and indicators

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning.

Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access.

Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction.

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis.

3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching.

Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely.

Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches.

Country level actions and global support

UNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank are joining forces to support countries to achieve the Mission, leveraging their expertise and actions on the ground to support national efforts and domestic funding.

Country Level Action

1. Mobilize team to support countries in achieving the three priorities

The Partners will collaborate and act at the country level to support governments in accelerating actions to advance the three priorities.

2. Advocacy to mobilize domestic resources for the three priorities

The Partners will engage with governments and decision-makers to prioritize education financing and mobilize additional domestic resources.

Global level action

1. Leverage data to inform decision-making

The Partners will join forces to conduct surveys; collect data; and set-up a global, regional, and national real-time data-warehouse. The Partners will collect timely data and analytics that provide access to information on school re-openings, learning losses, drop-outs, and transition from school to work, and will make data available to support decision-making and peer-learning.

2. Promote knowledge sharing and peer-learning in strengthening education recovery

The Partners will join forces in sharing the breadth of international experience and scaling innovations through structured policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and peer learning actions.

The time to act on these priorities is now. UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank are partnering to help drive that action.

Last Updated: Mar 30, 2021

- (BROCHURE, in English) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BLOG) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Arabic) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- World Bank Education and COVID-19

- World Bank Blogs on Education

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Reinventing Education Post-Pandemic

On December 16, 2021, we hosted a talk by Professor Justin Reich. Professor Reich discussed his research on how the experiences of students and teachers during pandemic schooling are vital to educational recovery and building back better.

Capturing the Perspectives of Teachers and Students

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, conversations focused on high-level questions about how the pandemic would disrupt education: Will schools stay open, and if so, under what conditions? How will the pandemic impact standardized test performance? However, Professor Justin Reich argues that when researchers simply focus on these two questions, they fail to consider a vital part of education: the day-to-day experiences of the teachers and students in the classroom.

In the spring of 2021, Reich and his team conducted three research exercises to understand these experiences:

- They invited 200 teachers to interview their students about the past year and share their findings (the instructions are available at http://bit.ly/imaginingseptember2021 ).

- They interviewed 50 classroom teachers.

- They conducted ten multistakeholder design charrettes with students, teachers, school leaders, and family members.

The spring 2021 research builds on research from Summer 2020, which had focused on understanding the initial school closures and pivots to remote learning in Spring 2020 and working with school communities to design a better experience for Fall 2020.

Disparate Impacts

Experts in online instruction will attest that high-quality remote learning looks quite different from traditional classroom learning. However, the quick pivot in Spring 2020 and ongoing lack of resources and training for teachers meant that in most cases, pandemic-era remote K-12 education mirrored traditional classroom education. Class time was moved to a video conferencing platform and materials were shared via digital Learning Management Systems rather than on paper, attempting to replicate in-person teaching rather than reshaping the learning experiences to take advantage of the affordances of remote learning while minimizing the drawbacks. Individual teachers also adopted discipline-specific tools that served functions such as collaboration, asynchronous content delivery, and practice. The abundance of tools led to an overwhelming number of logins and platforms for students and parents to manage until schools began to coordinate platforms centrally.

The remote student experience varied widely, and their academic and social experiences were not necessarily correlated. For example, some students with special needs struggled because they were cut off from needed special education resources, whereas others thrived in an environment with fewer distractions and more control over how they learn. Students shared that they did better academically without their friends around to distract them, but noted that they then struggled to reacclimate themselves to the social environment of the classroom. Other factors like access to broadband, relationships with family, and bullying and racism experienced at school also shaped student experiences of remote schooling.

For teachers, the experience was almost always exhausting and often demoralizing. Despite making recommendations to administrators and policy-makers, teachers often felt ignored when decisions were made. At the same time, teachers demonstrated tremendous resilience and capacity for innovation, developing new teaching strategies and adapting quickly to ensure their students’ needs were met.

Hopes for the Future

Reich presented three potential trajectories for post-pandemic education: a return to the status quo, a focus on remediating learning loss, or an organized effort to reinvent education to be more humane. Early efforts to return to the status quo are already demonstrating the problems with doing so, as schools struggle with understaffing and a rise in fighting among stressed students. Remediation, meanwhile, is popular among policymakers but does not resonate at the classroom level. As a deficit-oriented approach, remediation fails to recognize that while certain learning goals were not achieved, students demonstrated incredible resilience and learned a lot from the experience. The third approach, a humane reinvention, builds on the strengths that students and teachers alike have demonstrated. Though Reich favors this third approach, he recognizes that there are many barriers to change.

Interviews with teachers have reinforced the idea that teachers are capable of innovation, but the pandemic has left many too exhausted to take on new initiatives. Initiatives can be enjoyable and energizing when teachers are actively involved in shaping change that they believe will benefit them and their students. However, it will be hard to create such a productive environment unless teachers feel supported and trusted by administrators, policymakers, and communities. Another problem is that most of the United States relies on public schools to provide necessary social services for children. While schools have done their best to keep students safe, healthy, and fed, doing social services work can take time and resources away from their core mission of teaching and learning.

To overcome these barriers as society recovers from the pandemic, Reich supports the idea of “strategic subtraction” in which old practices are “hospiced” to make room for new initiatives. Some changes, like abolishing rules that do more to police student bodies and behaviors than to improve learning, are relatively straightforward. Students who have gotten used to an at-home learning environment and the associated autonomy are quick to point out that they can learn just as effectively while wearing a hoodie or enjoying a snack. Other changes, like remedying long-standing inequities in how schools access resources, will be more challenging.

Takeaways for Higher Education

Though his research focused on K-12 schools, Reich notes that it has several implications for higher education. Some of Reich’s findings parallel those seen at MIT and other universities. The loss of a year or more of socialization may impact an elementary school student differently than a college student, but both are returning to the classroom with new social challenges. Loneliness, isolation, and social anxiety have become common, and readjusting to social norms takes time.

Most importantly, K-12 schools shape the students who will become undergraduates. Incoming first-year students will have weathered a broad spectrum of pandemic-era educational experiences. Rather than focusing on filling gaps in these students’ knowledge, colleges would be wise to appreciate the strengths these students will bring to campus: their resilience, their capacity for self-regulated learning, and their hard work to make the best of an incredibly challenging situation.

Further Reading

All reports can be found at: tsl.mit.edu/covid19 , including the specific reports discussed in the talk:

- Healing Community and Humanity

- The Teachers Have Something to Say

About the Speaker

Justin Reich is an associate professor of digital media in the Comparative Media Studies/Writing department at MIT and the director of the Teaching Systems Lab. He is the author of Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education, and the host of the TeachLab Podcast . He earned his doctorate from the Harvard Graduate School of Education and was the Richard L. Menschel HarvardX Research Fellow. He is a past Fellow at the Berkman-Klein Center for Internet and Society. His writings have been published in Science, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Washington Post, The Atlantic, and other scholarly journals and public venues. He started his career as a high school history teacher, and coach of wrestling and outdoor adventure activities. Follow Justin on Twitter or Google Scholar .

Written by Kate Weishaar

active learning anti-racist equity inclusion

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

6 things we've learned about how the pandemic disrupted learning

Cory Turner

How did the pandemic disrupt learning for America's more than 50 million K-12 students?

For two years, that question has felt immeasurable, like a phantom, though few educators doubted the shadow it cast over children who spent months struggling to learn online.

Now, as a third pandemic school year draws to a close, new research offers the clearest accounting yet of the crisis's academic toll — as well as reason to hope that schools can help.

1. Surprise! Students learned less when they were remote

But really, this should surprise no one.

Most schools had little to no experience with remote instruction when the pandemic began; they lacked teacher training, appropriate software, laptops, universal internet access and, in many cases, students lacked stability and a supportive adult at home to help.

Even students who spent the least amount of time learning remotely during the 2020-21 school year — just a month or less — missed the equivalent of seven to 10 weeks of math learning, says Thomas Kane of the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University.

Much of that missed learning, Kane says, was likely a hangover from spring 2020, when nearly all schools were remote and remote instruction was at its worst.

Kane is part of a collaborative of researchers at Harvard, the American Institutes for Research, Dartmouth College and the school-testing nonprofit NWEA, who set out to measure just how much learning students missed during the pandemic.

And notice we're saying "missed," not "lost," because the problem is that when schools went remote, kids simply did not learn as much or as well as they would have in person.

" We try not to say 'learning loss,' because if they didn't learn it, they didn't lose it," explains Ebony Lee, an assistant superintendent in Clayton County, Ga.

Not everyone agrees. Some parents who saw their kids struggle while trying to learn remotely believe "learning loss" fits — because it captures the urgency they now feel to make up for what was lost.

"It would mean so much for parents if somebody would acknowledge it. 'You know, we have learning loss,' " says Sheila Walker, a parent in Northern California. "Like our board, they don't even use those words. We know we have learning loss, so how are we going to address it?"

Kane and his fellow researchers studied the test scores of more than 2 million elementary- and middle-schoolers, comparing the growth they made between fall 2017 and fall 2019 to their pandemic-era growth, from fall 2019 to fall 2021.

Though researchers focused on math, the instructional time students missed in reading was "comparable," Kane says.

One quick caveat: Obviously, test scores can tell us only so much about what students actually learn in a given year (social-emotional skills, for example, are harder to measure). But they're a start.

2. Students at high-poverty schools were hit hardest

Students at high-poverty schools experienced an academic double-whammy: Their schools were more likely to be remote and, when they were, students missed more learning.

The Coronavirus Crisis

How schools can help kids heal after a year of 'crisis and uncertainty'.

Let's break that down.

First, high-poverty schools spent about 5.5 more weeks in remote instruction during the 2020-21 school year than low- and mid-poverty schools, the report says. Researchers also found a "higher incidence of remote schooling for Black and Hispanic students."

And second, in high-poverty schools that stayed remote for the majority of the 2020-21 school year, students missed the equivalent of 22 weeks of in-person math learning.

That's more than half of a traditional school year (roughly 36-40 weeks).

By contrast, students in similarly remote, low-poverty schools missed considerably less learning: roughly 13 weeks, Kane says, and he warns that closing these gaps could take years.

Homeless Families Struggle With Impossible Choices As School Closures Continue

This new data backs up what many teachers and school leaders have been saying.

"It's very disconcerting," says Sharon Contreras, the superintendent of North Carolina's third-largest district, in Guilford County. "Because we know that the students who are most vulnerable saw the most amount of learning loss, and they were already behind."

Why did students in high-poverty schools miss more learning while remote? Recent U.S. Government Accountability Office surveys of more than 2,800 teachers offer some explanations.

Teachers in remote, high-poverty schools were more likely to report that their students lacked a workspace and internet at home, and were less likely to have an adult there to help. Many older students disengaged because the pandemic forced them to become caretakers, or to get jobs.

Making matters worse, as NPR has reported, high-poverty students were also more likely to experience food insecurity , homelessness and the loss of a loved one to COVID-19.

"These gaps are not new," says Becky Pringle, head of the National Education Association (NEA), the nation's largest teachers union. "We know that there are racial and social and economic injustices that exist in every system ... what the pandemic did was just like the pandemic did with everything: It just made it worse."

3. Different states saw different gaps

Kane and his fellow researchers found that learning gaps were most pronounced in states with higher rates of remote instruction overall.

For example, in the quarter of states where students spent the most time learning remotely, including California, Illinois, Kentucky and Virginia, "high-poverty schools spent an additional nine weeks in remote instruction (more than two months) than low-poverty schools," the report says.

On the other hand, in the quarter of states where overall use of remote instruction was the lowest, including Texas, Florida and a host of rural states, the report says, high-poverty schools were still more likely to be remote "but the differences were small: 3 weeks remote in high poverty schools versus 1 week remote in low poverty schools."

The report says, "as long as schools were in-person throughout 2020-21, there was no widening of math achievement gaps between high-, middle-, and low-poverty schools."

Kane says he hopes that, instead of relitigating districts' choices to stay remote, politicians and educators can use this data as a call to action.

"That student achievement declined is not a surprise," Kane says. "Rather, we should think of it as a bill for a public health measure that was taken on our behalf. And it's our obligation now, whether or not we agreed with those decisions, to pay that bill. We can't stiff our children."

4. High school graduation rates didn't change much

One more study , from Brookings, looks at the impact all this pandemic-driven turmoil had on high school graduation and college entry rates.

It turns out, for the 2019-20 school year, when graduation ceremonies were canceled and students ended the year at home, high school graduation rates actually increased slightly.

"The message clearly was 'just show up,' " says Douglas Harris, the study's lead researcher and director of the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice at Tulane University.

"So it became pretty easy," Harris says. "Anybody who was on the margin of graduating at that point was going to graduate because the states officially relaxed their standards."

For the 2020-21 school year, Harris says, states and school districts largely returned to pre-pandemic standards and, as a result, the high school graduation rate dipped slightly.

College enrollment plummeted during the pandemic. This fall, it's even worse

5. many high school grads chose to delay college.

While the pandemic appeared to have little impact on students' ability to finish high school, it seemed to have the opposite effect on their willingness to start college.

Harris says entry rates for recent high school grads at four-year colleges dipped 6% and a worrying 16% at two-year colleges. Why?

Harris has a theory: "I think for anybody, regardless of age, starting something new, trying to develop new relationships in the pandemic, was a nonstarter."

6. Schools can do something about it

School leaders are now racing to build programs that, they hope, will help students make up for at least some of this missed learning. One popular approach: "high-dosage" tutoring.

Here's what schools are doing to try to address students' social-emotional needs

"For us, high-dosage means two to three times per week for at least 30 minutes, and ... no more than three students in a group," says Penny Schwinn, Tennessee's state education commissioner.

Schwinn led the creation of the TN ALL Corps, a sprawling, statewide network of tutors who, Schwinn hopes, can reach 150,000 elementary- and middle-schoolers over three years. High school students with busier schedules can access online tutoring anytime, on demand.

In Guilford County, Contreras says the benefits of their tutoring program go well beyond learning recovery. Their new tutoring corps draws heavily from graduate assistants at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, a regional HBCU.

" We want to continue to grow the number of Black and brown teachers in the district," Contreras says. "So hiring graduate assistants was a very intentional effort to make sure our students saw themselves, but also to introduce those graduate assistants to the teaching profession."

Multiple superintendents, including Contreras, emphasized that the purpose of these tutoring efforts was not to look backward, over old material, but to support students as they move forward through new concepts.

"We don't want to remediate," Contreras says emphatically. "We want to accelerate learning."

Kane says districts should also consider making up for missed learning by adding more days to the school calendar .

"Schools already have the teachers. They already have the buildings. They already have the bus routes," Kane explains. Extending the school year may be logistically easier than, say, hiring and scheduling hundreds of new tutors.

But that doesn't mean extending the school year is easy.

In Los Angeles, where students spent most of the 2020-21 school year learning remotely, Superintendent Alberto Carvalho says he would love to expand the next school year by as many as 10 additional days to help address what he calls "unprecedented, historic learning loss." But, he says, "[that idea] ran into a lot of opposition" from parents and teachers alike.

So Carvalho has had to settle for four additional student learning days next year.

Kane acknowledges that adding time to the school year is asking a lot of teachers and some families and would likely require a pay bump above educators' normal weekly rate.

"Everybody is eager to return to normal. And I can appreciate that," Kane says, "but normal is not enough."

If there is a silver lining for districts rushing to create new learning opportunities, it's that many school leaders — and politicians — are realizing they make good sense long-term too.

In Los Angeles, Carvalho says many students attending high-poverty schools "were in crisis prior to COVID-19," academically speaking. And he hopes these new efforts, forced by the pandemic, "may actually catapult their learning experience."

Tennessee's ALL Corps "is now funded forever more," Schwinn says.

"So this isn't going to be a COVID recovery. This is just good practice for kids."

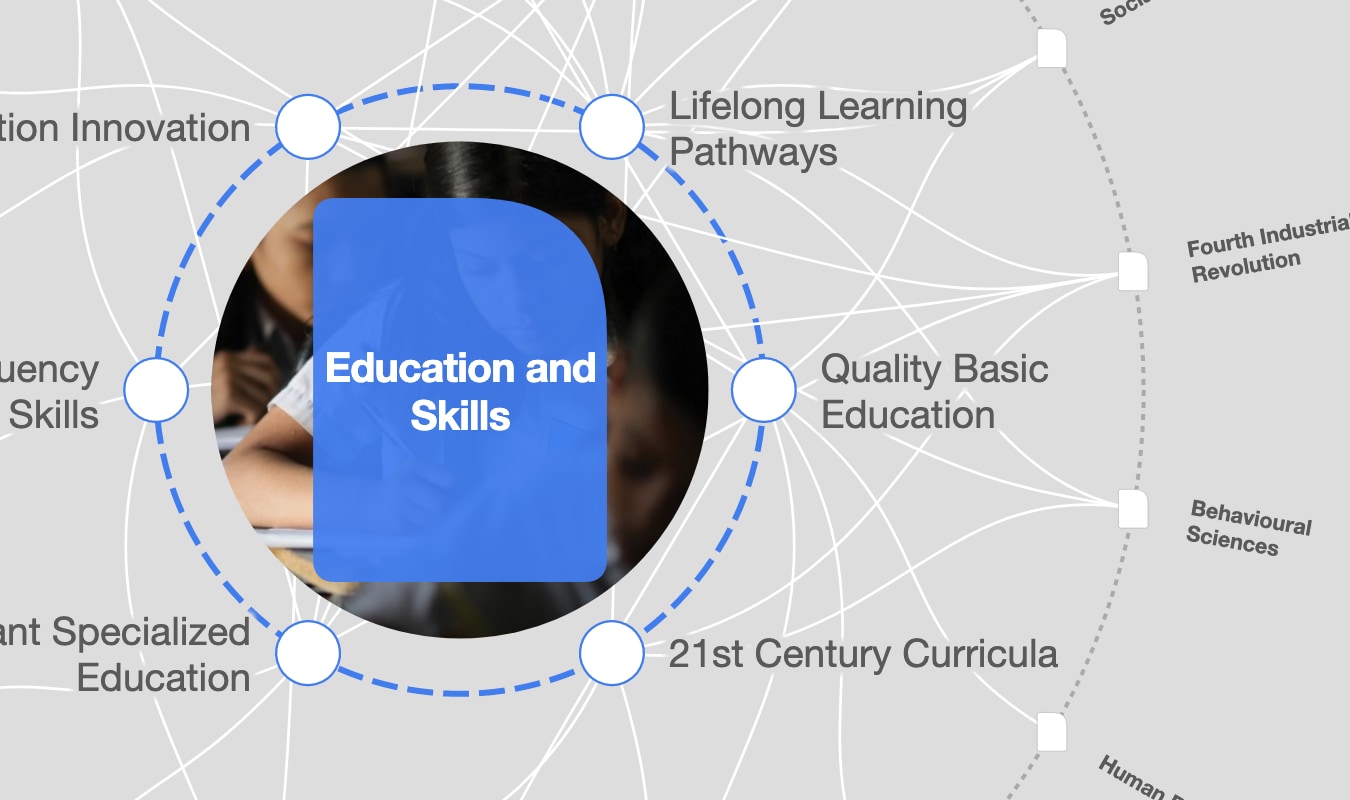

Futures of Education

- Research and knowledge

- New social contract

- Digital learning futures

- The Initiative 2019-2021

- National & local dialogues

- International advocacy

The Futures of Education

Our world is at a unique juncture in history, characterised by increasingly uncertain and complex trajectories shifting at an unprecedented speed. These sociological, ecological and technological trends are changing education systems, which need to adapt. Yet education has the most transformational potential to shape just and sustainable futures. UNESCO generates ideas, initiates public debate, and inspires research and action to renew education. This work aims to build a new social contract for education, grounded on principles of human rights, social justice, human dignity and cultural diversity. It unequivocally affirms education as a public endeavour and a common good.

No trend is destiny...Multiple alternative futures are possible... A new social contract for education needs to allow us to think differently about learning and the relationships between students, teachers, knowledge, and the world.

Our work is grounded in the principles of the 2021 report “Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education” and in the report’s call for action to consolidate global solidarity and international cooperation in education, as well as strengthen the global research agenda to reinforce our capacities to anticipate future change.

The report invites us to rebalance our relationship with:

- each other,

- the planet, and

- technology.

Summary of the Report

Renewing education to transform the future, 2-4 December 2024

UNESCO International Forum on the Futures of Education 2024 Suwon, Gyeonggido, Republic of Korea

Interview with Stefania Giannini, Assistant Director-General for Education

Featured highlights

The International Commission

In 2019 UNESCO Director–General convened an independent International Commission to work under the leadership of the President of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, H.E. President Sahle-Work Zewde, and develop a global report on the Futures of Education. The commission was charged with carefully considering inputs received through the different consultation processes and ensuring that this collective intelligence was reflected in the global report and other knowledge products connected with the initiative.

Sustainable development challenges and the role of education

Our foresight work, looking towards 2050, envisions possible futures in which education shapes a better world. Our starting point is observation of the multiple, interlocking challenges the world currently faces and how to renew learning and knowledge to steer policies and practices along more sustainable pathways.The challenges are great. But there are reasons for optimism, no trend is destiny.

Our work responds to the call of the International Commission on the Futures of Education to guide a new research agenda for the futures of education. This research agenda is wide-ranging and multifaceted as a future-oriented, planet-wide learning process on our futures together. It draws from diverse forms of knowledge and perspectives, and from a conceptual framework that sees insights from diverse sources as complementary rather than exclusionary and adversarial.

Linking current trends and the report of the International Commission on the Futures of Education.

- The global population is projected to reach a peak at around 10.4 billion people during the 2080s , nearly double the global population of 1990 (5.3 billion)

- There will be an estimated 170 million displaced people by 2050 , equivalent to 2.3% of the global population

- Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to be home to some 1/3 of the global population by 2050

"A new social contract for education requires renewed commitment to global collaboration in support of education as a common good, premised on more just and equitable cooperation among state and non-state actors. Beyond North-South flows of aid to education, the generation of knowledge and evidence through South-South and triangular cooperation must be strengthened."

- The number of persons aged 65 years or older worldwide is expected to double over the next three decades, reaching 1.6 billion in 2050 (16% of global population)

"Human longevity may also increase and perhaps with it, at least for some, the extension of the work period of life. If older people can remain active and engaged, they will enrich society and the economy through their skills and experience."

- Global temperatures are expected to increase 2.7 degrees by 2100 , leading to devastating global consequences

- Humans currently use as as many ecological resources as is we lived on 1.75 Earths

"The planet is in peril (...) Here children and youth already lead the way, calling for meaningful action and delivering a harsh rebuke to those who refuse to face the urgency of the situation. (...) One of the best strategies to prepare for green economies and a carbon-neutral future is to ensure qualifications, programmes and curricula deliver ‘green skills’, be they for newly emerging occupations and sectors or for those sectors undergoing transformation for the low-carbon economy."

- Global freedom has been declining for more than 15 years

"There has been a flourishing of increasingly active citizen participation and activism that is challenging discrimination and injustice worldwide (...) In educational content, methods and policy, we should promote active citizenship and democratic participation."

- There will be an estimated 380 million higher education students by 2030, up from roughly 220 million students were enrolled in formal post-secondary education in 2021

"Future policy agendas for higher education will need to embrace all levels of education and better account for non-traditional educational trajectories and pathways. Recognizing the interconnectedness of different levels and types of education, speaks to the need for a sector-wide, lifelong learning approach towards the future development of higher education."

- Less than 10% of school and universities have guidance on educational uses of AI

"The challenge of creating decent human-centered work is about to get much harder as Artificial Intelligence (AI), automation and structural transformations remake employment landscapes around the globe. At the same time, more people and communities are recognizing the value of care work and the multiple ways that economic security needs to be provisioned.”

- Fake news travel 6 times faster than true stories via Twitter - such disinformation undermines a shared perception of truth and reality

"Digital technologies, tools and platforms can be bent in the direction of supporting human rights, enhancing human capabilities, and facilitating collective action in the directions of peace, justice, and sustainability (...) A primary educational challenge is to equip people with tools for making sense of the oceans of information that are just a few swipes or keystrokes away."

- Employers anticipate a structural “labour market churn” (or disruption) of 23% of jobs in the next five years, resulting in a net decrease of 2% of current employment due to environmental, technological and economic trends.

"Underemployment, the inability to find work that matches one’s aspirations, skillset and capabilities, is a persistent and growing global problem, even among university graduates in many of the world’s wealthiest countries. This mismatch is combustible: social scientists have shown that a highly educated population unable to apply its skills and competencies in decent work, leads to discontent, agitation and sometime sparks political and civil strife... Learning must be relevant to the world of work. Young people need strong support upon educational completion to be integrated into labour markets and contribute to their communities and societies according to their potential."

- CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS: Global population in 2080s: 10.4 billion ( UNDESA World Population Prospects, 2022) /Africa 1/3 population ( UNDESA World Population Prospects, 2022)

- AGING POPULATIONS: 1.6 billion people over 65 in 2050 (UNDESA World Social Report , 2023)

- PLANETARY CRISIS: Humans use 1.75 Earths ( Global Footprint Network ) / Global temperatures to increase 2.7 degrees by 2100 ( UNFCCC Synthesis Report, 2021)

- DEMOCRATIC BACKSLIDING: Global freedom has been declining for more than 15 years ( Freedom House Freedom in the World report, 2023)

* All figures correct as of 2023.

- TECHNOLOGY: Less that 10% of school and universities have guidance on educational uses of AI ( UNESCO study, 2023)

- DISINFORMATION: Fake news travel 6 times faster than true stories via Twitter ( MIT study, 2018)

- UNCERTAIN FUTURE OF WORK: Net decrease of 2% of employment over next 5 years ( WEF Futures of Work report, 2023)

- CHANGING LIFELONG EDUCATION APPROACHES: 320 million students by 2030 ( World Bank blog, 2022)

The third in a series of major visioning exercises for education

Reimagining our future together: a new social contract for education is the third in a series of UNESCO-led once-a-generation foresight and visioning exercises, conducted at key moments of historical transition.

In 1972, the Learning to Be: the world of education today and tomorrow report already warned of the risks of inequalities, and emphasized the need for the continued expansion of education, for education throughout life and for building a learning society.

This was followed by the 1996 Learning: The treasure within report that proposed an integrated vision of education around four pillars: learning to be, learning to know, learning to do, and learning to live together in a lifelong perspective.

News and stories

Please feel free to contact us here if you have any questions or requests.

To help students recover from the pandemic, education leaders must prioritize equity and evidence

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, lindsay dworkin and lindsay dworkin vice president, policy and advocacy - nwea karyn lewis karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew.

October 13, 2021

As students return to classrooms this fall, COVID-19 continues to present schools across the country with challenging circumstances. The pandemic has already impacted learning on an unprecedented scale, exposing and magnifying deep inequities within our education system. While no one has been left unscathed, the impacts have been most severe for those who were already the furthest behind academically—students of color and those experiencing poverty.

In the coming school year and beyond, data on student progress will be critical to understanding the disproportionate impact of the pandemic and addressing the resulting inequities. While learning has suffered across the board, the data tell a nuanced story. Understanding those nuances—particularly at the state and local level—will be essential to targeting evidence-based interventions (and recovery resources) to the students who need them most.

The research team at NWEA has been working diligently throughout the pandemic to analyze data from the MAP Growth assessment to illuminate the effects of COVID-19 on student growth and achievement . Even amid very challenging circumstances, students made modest gains in reading and math in 2020-21 . We also see, however, that students experienced slower growth rates and lower achievement levels, on average, in both math and reading in 2020-21 compared to a more “typical” year (the 2018-19 school year). More specifically, students ended the year with reading achievement levels between 3 and 6 percentile points behind and 8 to 12 points behind in math.

The impacts of the pandemic were even larger among students of color and students experiencing poverty, especially in the youngest grades we studied. For example, Latino third graders showed declines of 17 points in math and 10 points in reading compared to historic averages. Black third graders ended the 2020-21 school year 15 points lower in math and 17 points lower in reading.

Figure 1: MAP Growth achievement percentile rank difference by cohort and race/ethnicity for reading and math

We found declines of a similar magnitude for students in high-poverty schools, where students in the earlier grades again saw the largest setbacks. For instance, third and fourth graders in high-poverty schools experienced declines in math achievement of 17 and 14 points, respectively, compared to a typical year.

Figure 2: MAP Growth achievement percentile rank difference by cohort and school poverty level for reading and math

Our education system is facing an unprecedented crisis. Despite the challenges, however, there is reason for optimism. With the near-universal return of in-person instruction and significant federal funding to deploy , education leaders have an opportunity to develop a strong foundation for equitable and excellent education for all students. Short-term recovery efforts can lead to long-term transformation if states and districts invest resources in evidence-based, holistic strategies , particularly those that have been proven to accelerate learning for historically underserved students.

More specifically, we believe that education leaders should:

- Re-engage disconnected students. Our data shows that the pandemic has impacted learning unevenly and on an unprecedented scale. Estimates suggest that as many as 3 million students across the country went “missing” from schools last year. This missingness is apparent in our data as well. We find overall attrition rates were higher than normal, which is to be expected given the challenges of the past year. We see even higher attrition rates for students of color, which means the true impacts of the pandemic on academic achievement may be even more dire that what we report. This underscores the need for states and districts to make extraordinary efforts to identify disconnected students , reconnect them to their school communities, and provide them with the support and interventions they need to access grade-level content while recovering lost ground.

- Expand instructional time. NWEA data shows that all student groups learned at a slower rate and ended the past school year with achievement below their same-grade peers in previous years. The disruption in instruction— particularly the reduction in structured learning time for many students —was surely part of the problem. In response, states and districts should consider expanding instructional time and opportunities for learning in evidence-based ways that have shown to improve outcomes for historically underserved students, such as through small-group tutoring and mentoring .

- Support access to remote learning technology for students and families. Before the pandemic, the “homework gap” left nearly 17 million children offline . That includes about one in three Black, Latino, and Native households—compared to about 20% of white households—and almost half of families making less than $25,000 per year. With instruction, extracurricular activities, and family engagement likely to continue to happen online (in some form) well into the future, it is essential to support the technological needs of students and families (e.g. access to high-speed internet and devices, as well as digital literacy).

- Attend to physical, social, and mental health needs of students. As the pandemic continues, students and families need support addressing basic needs and coping with everything from anxiety to trauma arising from major life disruptions. Evidence shows that students are unable to reach their academic potential without socioemotional and mental health support. States and districts should make mental health services available in schools , including increasing access to school nurses and counseling services . They can also partner with community organizations to support underserved families .

- Measure student progress and use data to advance learning. To understand the uneven impacts of the pandemic and inform effective recovery, it is essential that educators and school leaders have ongoing and high-quality data on multiple dimensions of student progress . Interventions should be targeted at students whose learning has suffered disproportionately and continuously adjusted to reflect evidence on what’s working , particularly for historically underserved students.

The pandemic has had the most dramatic impact on the learning of those students who could least afford to fall further behind. As a result, equity is the most important lens through which we must evaluate efficacy of educational investments and the success of recovery efforts. The impacts of COVID-19 will last far longer than the federal recovery funds. Thus, states and districts must look beyond short-term fixes and deploy resources to catalyze transformation that can last a generation. America’s children are counting on it.

Related Content

Dr. Nathan Chomilo, Chelsea Clinton, Dr. Judith Guzman-Cottrill, Dr. Neil A. Lewis, Jr.

August 26, 2021

Anita McGinty, Ann Partee, Allison Lynn Gray, Walter Herring, Jim Soland

July 19, 2021

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Phillip Levine, Luke Pardue

June 5, 2024

Carly D. Robinson, Katharine Meyer, Susanna Loeb

June 4, 2024

Monica Bhatt, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig

June 3, 2024

Most US students are recovering from pandemic-era setbacks, but millions are making up little ground

America’s schools have just started making progress toward getting students back on track after they fell behind by historic margins during the pandemic

ALEXANDRIA, Va. — On one side of the classroom, students circled teacher Maria Fletcher and practiced vowel sounds. In another corner, children read together from a book. Scattered elsewhere, students sat at laptop computers and got reading help from online tutors.

For the third graders at Mount Vernon Community School in Virginia, it was an ordinary school day. But educators were racing to get students learning more, faster, and to overcome setbacks that have persisted since schools closed for the COVID-19 pandemic four years ago.

America’s schools have started to make progress toward getting students back on track. But improvement has been slow and uneven across geography and economic status, with millions of students — often those from marginalized groups — making up little or no ground.

Nationally, students made up one-third of their pandemic losses in math during the past school year and one-quarter of the losses in reading, according to the Education Recovery Scorecard , an analysis of state and national test scores by researchers at Harvard and Stanford.

But in nine states, including Virginia, reading scores continued to fall during the 2022-23 school year after previous decreases during the pandemic.

Clouding the recovery is a looming financial crisis. States have used some money from the historic $190 billion in federal pandemic relief to help students catch up , but that money runs out later this year.

“The recovery is not finished, and it won’t be finished without state action,” said Thomas Kane, a Harvard economist behind the scorecard. “States need to start planning for what they’re going to do when the federal money runs out in September. And I think few states have actually started that discussion.”

Virginia lawmakers approved an extra $418 million last year to accelerate recovery. Massachusetts officials set aside $3.2 million to provide math tutoring for fourth and eighth grade students who are behind grade level, along with $8 million for literacy tutoring.

But among other states with lagging progress, few said they were changing their strategies or spending more to speed up improvement.

Virginia hired online tutoring companies and gave schools a “playbook” showing how to build effective tutoring programs. Lisa Coons, Virginia’s superintendent of public instruction, said last year’s state test scores were a wake-up call.

“We weren’t recovering as fast as we needed,” Coons said in an interview.

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona has called for states to continue funding extra academic help for students as the federal money expires.

“We just can’t stop now,” he said at a May 30 conference for education journalists. “The states need to recognize these interventions work. Funding public education does make a difference.”

In Virginia, the Alexandria district received $2.3 million in additional state money to expand tutoring.

At Mount Vernon, where classes are taught in English and Spanish, students are divided into groups and rotate through stations customized to their skill level. Those who need the most help get online tutoring. In Fletcher’s classroom, a handful of students wore headsets and worked with tutors through Ignite Learning, one of the companies hired by the state.

With tutors in high demand, the online option has been a big help, Mount Vernon principal Jennifer Hamilton said.

“That’s something that we just could not provide here,” she said.

Ana Marisela Ventura Moreno said her 9-year-old daughter, Sabrina, benefited significantly from extra reading help last year during second grade, but she’s still catching up.

“She needs to get better. She’s not at the level she should be,” the mother said in Spanish. She noted the school did not offer the tutoring help this year, but she did not know why.

Alexandria education officials say students scoring below proficient or close to that cutoff receive high-intensity tutoring help and they have to prioritize students with the greatest needs. Alexandria trailed the state average on math and reading exams in 2023, but it’s slowly improving.

More worrying to officials are the gaps: Among poorer students at Mount Vernon, just 24% scored proficient in math and 28% hit the mark in reading. That’s far lower than the rates among wealthier students, and the divide is growing wider.

Failing to get students back on track could have serious consequences. The researchers at Harvard and Stanford found communities with higher test scores have higher incomes and lower rates of arrest and incarceration. If pandemic setbacks become permanent, it could follow students for life.

The Education Recovery Scorecard tracks about 30 states, all of which made at least some improvement in math from 2022 to 2023. The states whose reading scores fell in that span, in addition to Virginia, were Nevada, California, South Dakota, Wyoming, Indiana, Oklahoma, Connecticut and Washington.

Only a few states have rebounded to pre-pandemic testing levels. Alabama was the only state where math achievement increased past 2019 levels, while Illinois, Mississippi and Louisiana accomplished that in reading.

In Chicago Public Schools, the average reading score went up by the equivalent of 70% of a grade level from 2022 to 2023. Math gains were less dramatic, with students still behind almost half a grade level compared with 2019. Chicago officials credit the improvement to changes made possible with nearly $3 billion in federal relief.

The district trained hundreds of Chicago residents to work as tutors. Every school building got an interventionist, an educator who focuses on helping struggling students.

The district also used federal money for home visits and expanded arts education in an effort to re-engage students.

“Academic recovery in isolation, just through ‘drill and kill,’ either tutoring or interventions, is not effective,” said Bogdana Chkoumbova, the district’s chief education officer. “Students need to feel engaged.”

At Wells Preparatory Elementary on the city’s South Side, just 3% of students met state reading standards in 2021. Last year, 30% hit the mark. Federal relief allowed the school to hire an interventionist for the first time, and teachers get paid to team up on recovery outside working hours.

In the classroom, the school put a sharper focus on collaboration. Along with academic setbacks, students came back from school closures with lower maturity levels, principal Vincent Izuegbu said. By building lessons around discussion, officials found students took more interest in learning.

“We do not let 10 minutes go by without a teacher giving students the opportunity to engage with the subject,” Izuegbu said. “That’s very, very important in terms of the growth that we’ve seen.”

Olorunkemi Atoyebi was an A student before the pandemic, but after spending fifth grade learning at home, she fell behind. During remote learning, she was nervous about stopping class to ask questions. Before long, math lessons stopped making sense.

When she returned to school, she struggled with multiplication and terms such as “dividend” and “divisor” confused her.

While other students worked in groups, her math teacher took her aside for individual help. Atoyebi learned a rhyming song to help memorize multiplication tables. Over time, it began to click.

“They made me feel more confident in everything,” said Atoyebi, now 14. “My grades started going up. My scores started going up. Everything has felt like I understand it better.”

Associated Press writers Michael Melia in Hartford, Connecticut, and Chrissie Thompson in Las Vegas contributed to this report.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

140k Accesses

213 Citations

337 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic