Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Scope and Delimitations – Explained & Example

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 2, 2020

What Is Scope and Delimitation in Research?

The scope and delimitations of a thesis, dissertation or research paper define the topic and boundaries of the research problem to be investigated.

The scope details how in-depth your study is to explore the research question and the parameters in which it will operate in relation to the population and timeframe.

The delimitations of a study are the factors and variables not to be included in the investigation. In other words, they are the boundaries the researcher sets in terms of study duration, population size and type of participants, etc.

Difference Between Delimitations and Limitations

Delimitations refer to the boundaries of the research study, based on the researcher’s decision of what to include and what to exclude. They narrow your study to make it more manageable and relevant to what you are trying to prove.

Limitations relate to the validity and reliability of the study. They are characteristics of the research design or methodology that are out of your control but influence your research findings. Because of this, they determine the internal and external validity of your study and are considered potential weaknesses.

In other words, limitations are what the researcher cannot do (elements outside of their control) and delimitations are what the researcher will not do (elements outside of the boundaries they have set). Both are important because they help to put the research findings into context, and although they explain how the study is limited, they increase the credibility and validity of a research project.

Guidelines on How to Write a Scope

A good scope statement will answer the following six questions:

- Why – the general aims and objectives (purpose) of the research.

- What – the subject to be investigated, and the included variables.

- Where – the location or setting of the study, i.e. where the data will be gathered and to which entity the data will belong.

- When – the timeframe within which the data is to be collected.

- Who – the subject matter of the study and the population from which they will be selected. This population needs to be large enough to be able to make generalisations.

- How – how the research is to be conducted, including a description of the research design (e.g. whether it is experimental research, qualitative research or a case study), methodology, research tools and analysis techniques.

To make things as clear as possible, you should also state why specific variables were omitted from the research scope, and whether this was because it was a delimitation or a limitation. You should also explain why they could not be overcome with standard research methods backed up by scientific evidence.

How to Start Writing Your Study Scope

Use the below prompts as an effective way to start writing your scope:

- This study is to focus on…

- This study covers the…

- This study aims to…

Guidelines on How to Write Delimitations

Since the delimitation parameters are within the researcher’s control, readers need to know why they were set, what alternative options were available, and why these alternatives were rejected. For example, if you are collecting data that can be derived from three different but similar experiments, the reader needs to understand how and why you decided to select the one you have.

Your reasons should always be linked back to your research question, as all delimitations should result from trying to make your study more relevant to your scope. Therefore, the scope and delimitations are usually considered together when writing a paper.

How to Start Writing Your Study Delimitations

Use the below prompts as an effective way to start writing your study delimitations:

- This study does not cover…

- This study is limited to…

- The following has been excluded from this study…

Examples of Delimitation in Research

Examples of delimitations include:

- research objectives,

- research questions,

- research variables,

- target populations,

- statistical analysis techniques .

Examples of Limitations in Research

Examples of limitations include:

- Issues with sample and selection,

- Insufficient sample size, population traits or specific participants for statistical significance,

- Lack of previous research studies on the topic which has allowed for further analysis,

- Limitations in the technology/instruments used to collect your data,

- Limited financial resources and/or funding constraints.

An In Press article is a paper that has been accepted for publication and is being prepared for print.

Fieldwork can be essential for your PhD project. Use these tips to help maximise site productivity and reduce your research time by a few weeks.

Is it really possible to do a PhD while working? The answer is ‘yes’, but it comes with several ‘buts’. Read our post to find out if it’s for you.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

This post explains where and how to write the list of figures in your thesis or dissertation.

Scientific misconduct can be described as a deviation from the accepted standards of scientific research, study and publication ethics.

Jay is in the third year of his PhD at Savitribai Phule Pune University, researching the applications of mesenchymal stem cells and nanocarrier for bone tissue engineering.

Elmira is in the third year of her PhD program at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology; Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, researching the mechanisms of acute myeloid leukemia cells resistance to targeted therapy.

Join Thousands of Students

Scope and Delimitations in Research

Delimitations are the boundaries that the researcher sets in a research study, deciding what to include and what to exclude. They help to narrow down the study and make it more manageable and relevant to the research goal.

Updated on October 19, 2022

All scientific research has boundaries, whether or not the authors clearly explain them. Your study's scope and delimitations are the sections where you define the broader parameters and boundaries of your research.

The scope details what your study will explore, such as the target population, extent, or study duration. Delimitations are factors and variables not included in the study.

Scope and delimitations are not methodological shortcomings; they're always under your control. Discussing these is essential because doing so shows that your project is manageable and scientifically sound.

This article covers:

- What's meant by “scope” and “delimitations”

- Why these are integral components of every study

- How and where to actually write about scope and delimitations in your manuscript

- Examples of scope and delimitations from published studies

What is the scope in a research paper?

Simply put, the scope is the domain of your research. It describes the extent to which the research question will be explored in your study.

Articulating your study's scope early on helps you make your research question focused and realistic.

It also helps decide what data you need to collect (and, therefore, what data collection tools you need to design). Getting this right is vital for both academic articles and funding applications.

What are delimitations in a research paper?

Delimitations are those factors or aspects of the research area that you'll exclude from your research. The scope and delimitations of the study are intimately linked.

Essentially, delimitations form a more detailed and narrowed-down formulation of the scope in terms of exclusion. The delimitations explain what was (intentionally) not considered within the given piece of research.

Scope and delimitations examples

Use the following examples provided by our expert PhD editors as a reference when coming up with your own scope and delimitations.

Scope example

Your research question is, “What is the impact of bullying on the mental health of adolescents?” This topic, on its own, doesn't say much about what's being investigated.

The scope, for example, could encompass:

- Variables: “bullying” (dependent variable), “mental health” (independent variable), and ways of defining or measuring them

- Bullying type: Both face-to-face and cyberbullying

- Target population: Adolescents aged 12–17

- Geographical coverage: France or only one specific town in France

Delimitations example

Look back at the previous example.

Exploring the adverse effects of bullying on adolescents' mental health is a preliminary delimitation. This one was chosen from among many possible research questions (e.g., the impact of bullying on suicide rates, or children or adults).

Delimiting factors could include:

- Research design : Mixed-methods research, including thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and statistical analysis of a survey

- Timeframe : Data collection to run for 3 months

- Population size : 100 survey participants; 15 interviewees

- Recruitment of participants : Quota sampling (aiming for specific portions of men, women, ethnic minority students etc.)

We can see that every choice you make in planning and conducting your research inevitably excludes other possible options.

What's the difference between limitations and delimitations?

Delimitations and limitations are entirely different, although they often get mixed up. These are the main differences:

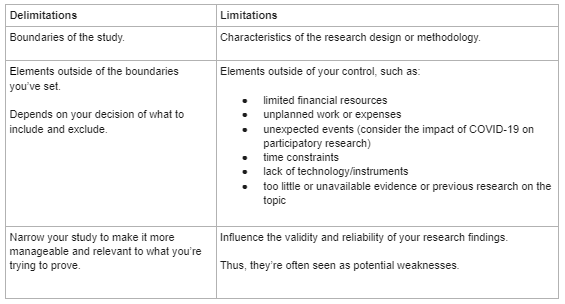

This chart explains the difference between delimitations and limitations. Delimitations are the boundaries of the study while the limitations are the characteristics of the research design or methodology.

Delimitations encompass the elements outside of the boundaries you've set and depends on your decision of what yo include and exclude. On the flip side, limitations are the elements outside of your control, such as:

- limited financial resources

- unplanned work or expenses

- unexpected events (for example, the COVID-19 pandemic)

- time constraints

- lack of technology/instruments

- unavailable evidence or previous research on the topic

Delimitations involve narrowing your study to make it more manageable and relevant to what you're trying to prove. Limitations influence the validity and reliability of your research findings. Limitations are seen as potential weaknesses in your research.

Example of the differences

To clarify these differences, go back to the limitations of the earlier example.

Limitations could comprise:

- Sample size : Not large enough to provide generalizable conclusions.

- Sampling approach : Non-probability sampling has increased bias risk. For instance, the researchers might not manage to capture the experiences of ethnic minority students.

- Methodological pitfalls : Research participants from an urban area (Paris) are likely to be more advantaged than students in rural areas. A study exploring the latter's experiences will probably yield very different findings.

Where do you write the scope and delimitations, and why?

It can be surprisingly empowering to realize you're restricted when conducting scholarly research. But this realization also makes writing up your research easier to grasp and makes it easier to see its limits and the expectations placed on it. Properly revealing this information serves your field and the greater scientific community.

Openly (but briefly) acknowledge the scope and delimitations of your study early on. The Abstract and Introduction sections are good places to set the parameters of your paper.

Next, discuss the scope and delimitations in greater detail in the Methods section. You'll need to do this to justify your methodological approach and data collection instruments, as well as analyses

At this point, spell out why these delimitations were set. What alternative options did you consider? Why did you reject alternatives? What could your study not address?

Let's say you're gathering data that can be derived from different but related experiments. You must convince the reader that the one you selected best suits your research question.

Finally, a solid paper will return to the scope and delimitations in the Findings or Discussion section. Doing so helps readers contextualize and interpret findings because the study's scope and methods influence the results.

For instance, agricultural field experiments carried out under irrigated conditions yield different results from experiments carried out without irrigation.

Being transparent about the scope and any outstanding issues increases your research's credibility and objectivity. It helps other researchers replicate your study and advance scientific understanding of the same topic (e.g., by adopting a different approach).

How do you write the scope and delimitations?

Define the scope and delimitations of your study before collecting data. This is critical. This step should be part of your research project planning.

Answering the following questions will help you address your scope and delimitations clearly and convincingly.

- What are your study's aims and objectives?

- Why did you carry out the study?

- What was the exact topic under investigation?

- Which factors and variables were included? And state why specific variables were omitted from the research scope.

- Who or what did the study explore? What was the target population?

- What was the study's location (geographical area) or setting (e.g., laboratory)?

- What was the timeframe within which you collected your data ?

- Consider a study exploring the differences between identical twins who were raised together versus identical twins who weren't. The data collection might span 5, 10, or more years.

- A study exploring a new immigration policy will cover the period since the policy came into effect and the present moment.

- How was the research conducted (research design)?

- Experimental research, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research, literature review, etc.

- What data collection tools and analysis techniques were used? e.g., If you chose quantitative methods, which statistical analysis techniques and software did you use?

- What did you find?

- What did you conclude?

Useful vocabulary for scope and delimitations

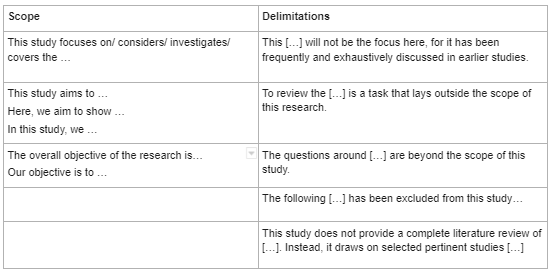

When explaining both the scope and delimitations, it's important to use the proper language to clearly state each.

For the scope , use the following language:

- This study focuses on/considers/investigates/covers the following:

- This study aims to . . . / Here, we aim to show . . . / In this study, we . . .

- The overall objective of the research is . . . / Our objective is to . . .

When stating the delimitations, use the following language:

- This [ . . . ] will not be the focus, for it has been frequently and exhaustively discusses in earlier studies.

- To review the [ . . . ] is a task that lies outside the scope of this study.

- The following [ . . . ] has been excluded from this study . . .

- This study does not provide a complete literature review of [ . . . ]. Instead, it draws on selected pertinent studies [ . . . ]

Analysis of a published scope

In one example, Simione and Gnagnarella (2020) compared the psychological and behavioral impact of COVID-19 on Italy's health workers and general population.

Here's a breakdown of the study's scope into smaller chunks and discussion of what works and why.

Also notable is that this study's delimitations include references to:

- Recruitment of participants: Convenience sampling

- Demographic characteristics of study participants: Age, sex, etc.

- Measurements methods: E.g., the death anxiety scale of the Existential Concerns Questionnaire (ECQ; van Bruggen et al., 2017) etc.

- Data analysis tool: The statistical software R

Analysis of published scope and delimitations

Scope of the study : Johnsson et al. (2019) explored the effect of in-hospital physiotherapy on postoperative physical capacity, physical activity, and lung function in patients who underwent lung cancer surgery.

The delimitations narrowed down the scope as follows:

Refine your scope, delimitations, and scientific English

English ability shouldn't limit how clear and impactful your research can be. Expert AJE editors are available to assess your science and polish your academic writing. See AJE services here .

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Setting Limits and Focusing Your Study: Exploring scope and delimitation

As a researcher, it can be easy to get lost in the vast expanse of information and data available. Thus, when starting a research project, one of the most important things to consider is the scope and delimitation of the study. Setting limits and focusing your study is essential to ensure that the research project is manageable, relevant, and able to produce useful results. In this article, we will explore the importance of setting limits and focusing your study through an in-depth analysis of scope and delimitation.

Company Name 123

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, cu usu cibo vituperata, id ius probo maiestatis inciderint, sit eu vide volutpat.

Sign Up for More Insights

Table of Contents

Scope and Delimitation – Definition and difference

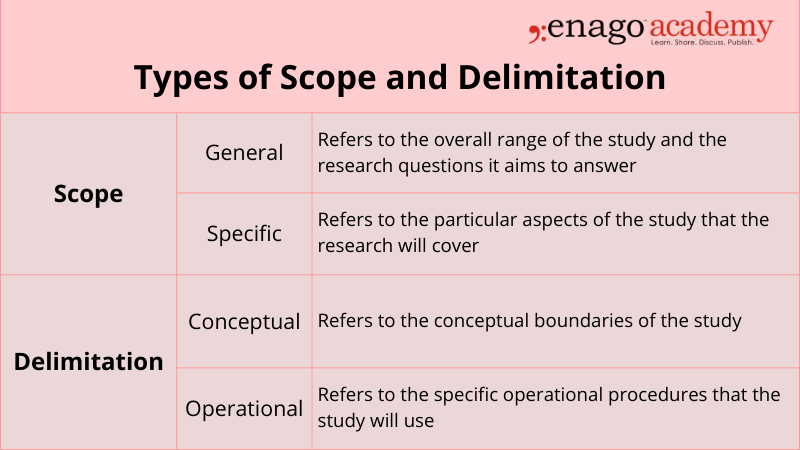

Scope refers to the range of the research project and the study limitations set in place to define the boundaries of the project and delimitation refers to the specific aspects of the research project that the study will focus on.

In simpler words, scope is the breadth of your study, while delimitation is the depth of your study.

Scope and delimitation are both essential components of a research project, and they are often confused with one another. The scope defines the parameters of the study, while delimitation sets the boundaries within those parameters. The scope and delimitation of a study are usually established early on in the research process and guide the rest of the project.

Types of Scope and Delimitation

Significance of Scope and Delimitation

Setting limits and focusing your study through scope and delimitation is crucial for the following reasons:

- It allows researchers to define the research project’s boundaries, enabling them to focus on specific aspects of the project. This focus makes it easier to gather relevant data and avoid unnecessary information that might complicate the study’s results.

- Setting limits and focusing your study through scope and delimitation enables the researcher to stay within the parameters of the project’s resources.

- A well-defined scope and delimitation ensure that the research project can be completed within the available resources, such as time and budget, while still achieving the project’s objectives.

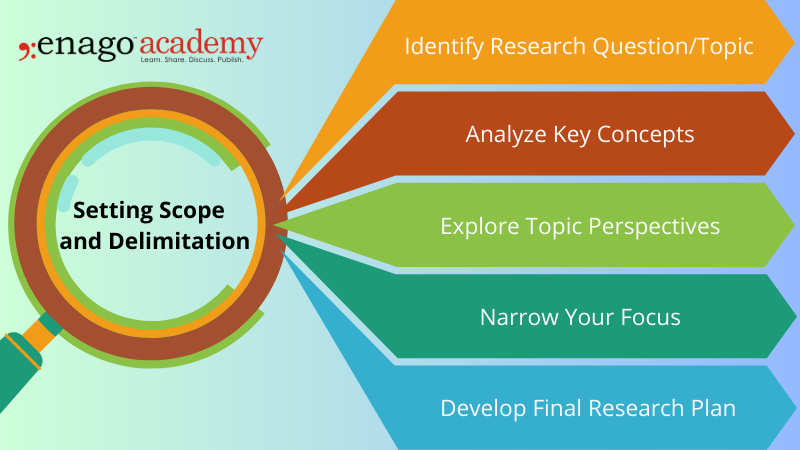

5 Steps to Setting Limits and Defining the Scope and Delimitation of Your Study

There are a few steps that you can take to set limits and focus your study.

1. Identify your research question or topic

The first step is to identify what you are interested in learning about. The research question should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Once you have a research question or topic, you can start to narrow your focus.

2. Consider the key terms or concepts related to your topic

What are the important terms or concepts that you need to understand in order to answer your research question? Consider all available resources, such as time, budget, and data availability, when setting scope and delimitation.

The scope and delimitation should be established within the parameters of the available resources. Once you have identified the key terms or concepts, you can start to develop a glossary or list of definitions.

3. Consider the different perspectives on your topic

There are often different perspectives on any given topic. Get feedback on the proposed scope and delimitation. Advisors can provide guidance on the feasibility of the study and offer suggestions for improvement.

It is important to consider all of the different perspectives in order to get a well-rounded understanding of your topic.

4. Narrow your focus

Be specific and concise when setting scope and delimitation. The parameters of the study should be clearly defined to avoid ambiguity and ensure that the study is focused on relevant aspects of the research question.

This means deciding which aspects of your topic you will focus on and which aspects you will eliminate.

5. Develop the final research plan

Revisit and revise the scope and delimitation as needed. As the research project progresses, the scope and delimitation may need to be adjusted to ensure that the study remains focused on the research question and can produce useful results. This plan should include your research goals, methods, and timeline.

Examples of Scope and Delimitation

To better understand scope and delimitation, let us consider two examples of research questions and how scope and delimitation would apply to them.

Research question: What are the effects of social media on mental health?

Scope: The scope of the study will focus on the impact of social media on the mental health of young adults aged 18-24 in the United States.

Delimitation: The study will specifically examine the following aspects of social media: frequency of use, types of social media platforms used, and the impact of social media on self-esteem and body image.

Research question: What are the factors that influence employee job satisfaction in the healthcare industry?

Scope: The scope of the study will focus on employee job satisfaction in the healthcare industry in the United States.

Delimitation: The study will specifically examine the following factors that influence employee job satisfaction: salary, work-life balance, job security, and opportunities for career growth.

Setting limits and defining the scope and delimitation of a research study is essential to conducting effective research. By doing so, researchers can ensure that their study is focused, manageable, and feasible within the given time frame and resources. It can also help to identify areas that require further study, providing a foundation for future research.

So, the next time you embark on a research project, don’t forget to set clear limits and define the scope and delimitation of your study. It may seem like a tedious task, but it can ultimately lead to more meaningful and impactful research. And if you still can’t find a solution, reach out to Enago Academy using #AskEnago and tag @EnagoAcademy on Twitter , Facebook , and Quora .

Frequently Asked Questions

The scope in research refers to the boundaries and extent of a study, defining its specific objectives, target population, variables, methods, and limitations, which helps researchers focus and provide a clear understanding of what will be investigated.

Delimitation in research defines the specific boundaries and limitations of a study, such as geographical, temporal, or conceptual constraints, outlining what will be excluded or not within the scope of investigation, providing clarity and ensuring the study remains focused and manageable.

To write a scope; 1. Clearly define research objectives. 2. Identify specific research questions. 3. Determine the target population for the study. 4. Outline the variables to be investigated. 5. Establish limitations and constraints. 6. Set boundaries and extent of the investigation. 7. Ensure focus, clarity, and manageability. 8. Provide context for the research project.

To write delimitations; 1. Identify geographical boundaries or constraints. 2. Define the specific time period or timeframe of the study. 3. Specify the sample size or selection criteria. 4. Clarify any demographic limitations (e.g., age, gender, occupation). 5. Address any limitations related to data collection methods. 6. Consider limitations regarding the availability of resources or data. 7. Exclude specific variables or factors from the scope of the study. 8. Clearly state any conceptual boundaries or theoretical frameworks. 9. Acknowledge any potential biases or constraints in the research design. 10. Ensure that the delimitations provide a clear focus and scope for the study.

What is an example of delimitation of the study?

Thank you 💕

Thank You very simplified🩷

Thanks, I find this article very helpful

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![what is scope in research study What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Research Manuscripts Using AI-Powered Insights: Enago reports for effective research communication

Language Quality Importance in Academia AI in Evaluating Language Quality Enago Language Reports Live Demo…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Academic Research in Education

- How to Find Books, Articles and eBooks

- Books, eBooks, & Multimedia

- Evaluating Information

- Deciding on a Topic

- Creating a Thesis Statement

- The Literature Review

- Scope of Research

Defining the Scope of your Project

What is scope.

- Choosing a Design

- Citing Sources & Avoiding Plagiarism

- Contact Library

Post-Grad Collective [PGC]. (2017, February 13). Thesis Writing-Narrow the Scope [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlCO5yRB9No&feature=youtu.be

Learn to cite a YouTube Video!

The scope of your project sets clear parameters for your research.

A scope statement will give basic information about the depth and breadth of the project. It tells your reader exactly what you want to find out , how you will conduct your study, the reports and deliverables that will be part of the outcome of the study, and the responsibilities of the researchers involved in the study. The extent of the scope will be a part of acknowledging any biases in the research project.

Defining the scope of a project:

- focuses your research goals

- clarifies the expectations for your research project

- helps you determine potential biases in your research methodology by acknowledging the limits of your research study

- identifies the limitations of your research

- << Previous: The Literature Review

- Next: Choosing a Design >>

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 9:06 AM

- URL: https://moc.libguides.com/aca_res_edu

Faculty & Staff Directory

Event Calendar

News Archives

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

Public Relations

634 Henderson St.

Mount Olive, NC 28365

1-800-653-0854

Chapter 1: Getting started with research

1.2 Determining your scope

The first thing you need to do is determine the scope of your research. Take a few minutes to think about your topic and the kind of information you might need. You can define your research scope by thinking about the following:

- Amount: how much information you need

- Content: the types of information you need

- Format: the configuration of the source (e.g., books, articles, videos, etc.)

Establishing the boundaries for your research may come from your instructor’s assignment guidelines. By carefully reviewing your assignment requirements and your instructor’s expectations, you can refine what research question you’re trying to answer and determine where you need to look for sources, what types and formats to use, and what content within your sources will be helpful.

Information that is appropriate for one research project may not be appropriate or relevant for another. For example, if you need to give a five minute class presentation on the pros or cons of an issue, you probably need a few sources that cover the key aspects of the issue and not every paper that’s ever been written on the topic. If you were writing a lengthy class paper, you would want more comprehensive coverage of your topic.

Amount of information

Sometimes your instructor will require that you use at least a specific number of sources for a project, but you won’t always have that as a guideline. If you need to determine the number of sources to use on your own, you can base it on what seems to be enough to fully answer your research question. Keep in mind that this might be more sources than the minimum you’re required to use.

Types of information

Knowing what types of information you need will help you be more efficient and successful in your research. Some common types of information are listed below.

Background information

This kind of information gives you a basic understanding and vocabulary surrounding a topic. Background information is broad and tends to be general. This is helpful when you don’t already know a lot about your topic. Examples of where you can find background information include encyclopedias like Encyclopaedia Britannica and Wikipedia or introductory textbooks.

News sources

News reports can provide information on an event or perspectives from a given point in time. They’re intended to keep us informed about current events and popular topics, and rarely go in depth or provide sources for further reading. News sources can help illustrate your points with timely examples or historical perspectives on a topic. They include historical or current newspapers, news websites, and some magazines. The Des Moines Register and Time magazine are examples of news sources.

Statistical information

Statistical information includes data and reports produced by research groups, associations, governmental organizations, non-profits, and more. These are helpful for making comparisons between groups, showing changes over time, and making predictions. Statistical databases and government websites, like the U.S. Census website, are examples of sources that contain statistics.

Library 160: Introduction to College-Level Research Copyright © 2021 by Iowa State University Library Instruction Services is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Implement Sci

Scoping studies: advancing the methodology

Danielle levac.

1 School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, 1400 Main Street West, Room 403, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Heather Colquhoun

Kelly k o'brien.

2 Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Scoping studies are an increasingly popular approach to reviewing health research evidence. In 2005, Arksey and O'Malley published the first methodological framework for conducting scoping studies. While this framework provides an excellent foundation for scoping study methodology, further clarifying and enhancing this framework will help support the consistency with which authors undertake and report scoping studies and may encourage researchers and clinicians to engage in this process.

We build upon our experiences conducting three scoping studies using the Arksey and O'Malley methodology to propose recommendations that clarify and enhance each stage of the framework. Recommendations include: clarifying and linking the purpose and research question (stage one); balancing feasibility with breadth and comprehensiveness of the scoping process (stage two); using an iterative team approach to selecting studies (stage three) and extracting data (stage four); incorporating a numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis, reporting results, and considering the implications of study findings to policy, practice, or research (stage five); and incorporating consultation with stakeholders as a required knowledge translation component of scoping study methodology (stage six). Lastly, we propose additional considerations for scoping study methodology in order to support the advancement, application and relevance of scoping studies in health research.

Specific recommendations to clarify and enhance this methodology are outlined for each stage of the Arksey and O'Malley framework. Continued debate and development about scoping study methodology will help to maximize the usefulness and rigor of scoping study findings within healthcare research and practice.

Scoping studies (or scoping reviews) represent an increasingly popular approach to reviewing health research evidence [ 1 ]. However, no universal scoping study definition or purpose exists (Table (Table1) 1 ) [ 1 , 2 ]. Definitions commonly refer to 'mapping,' a process of summarizing a range of evidence in order to convey the breadth and depth of a field. Scoping studies differ from systematic reviews because authors do not typically assess the quality of included studies [ 3 - 5 ]. Scoping studies also differ from narrative or literature reviews in that the scoping process requires analytical reinterpretation of the literature [ 1 ].

Definitions and purposes of scoping studies

Researchers can undertake a scoping study to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity, determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review, summarize and disseminate research findings, or identify gaps in the existing literature [ 6 ]. As such, researchers can use scoping studies to clarify a complex concept and refine subsequent research inquiries [ 1 ]. Scoping studies may be particularly relevant to disciplines with emerging evidence, such as rehabilitation science, in which the paucity of randomized controlled trials makes it difficult for researchers to undertake systematic reviews. In these situations, scoping studies are ideal because researchers can incorporate a range of study designs in both published and grey literature, address questions beyond those related to intervention effectiveness, and generate findings that can complement the findings of clinical trials.

In an effort to provide guidance to authors undertaking scoping studies, Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] developed a six-stage methodological framework: identifying the research question, searching for relevant studies, selecting studies, charting the data, collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, and consulting with stakeholders to inform or validate study findings (Table (Table2). 2 ). While this framework provided an excellent methodological foundation, published scoping studies continue to lack sufficient methodological description or detail about the data analysis process, making it challenging for readers to understand how study findings were determined [ 1 ]. Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] encouraged other authors to refine their framework in order to enhance the methodology.

Overview of the Arksey and O'Malley methodological framework for conducting a scoping study

In this paper, we apply our experiences using the Arksey and O'Malley framework to build on the existing methodological framework. Specifically, we propose recommendations for each stage of the framework, followed by considerations for the advancement, application, and relevance of scoping studies in health research. Continual refinement of the framework stages may provide greater clarity about scoping study methodology, encourage researchers and clinicians to engage in this process, and help to enhance the methodological rigor with which authors undertake and report scoping studies [ 1 ].

We each completed a scoping study in separate areas of rehabilitation using the Arksey and O'Malley framework [ 6 ]. Goals of these studies included: identifying research priorities within HIV and rehabilitation [ 7 ], applying motor learning strategies within pediatric physical and occupational therapy intervention approaches [ 8 ], and exploring the use of theory within studies of knowledge translation [ 9 ]. The amount of literature reviewed in our studies ranged from 31 (DL) to 146 (KO) publications. Upon discovering that we had similar challenges implementing the scoping study methodology, we decided to use our experiences to further develop the existing framework. We conducted an informal literature search on scoping study methodology. We searched CINAHL, MEDLINE, PubMed, ERIC, PsycInfo, and Web of Science databases using the search terms 'scoping,' 'scoping study,' 'scoping review,' and 'scoping methodology' for papers published in English between January 1990 and May 2010. Reference lists of pertinent papers were also searched. This search yielded seven citations that reflected on scoping study methodology, which were reviewed by one author (DL). After independently considering our own experiences utilizing the Arskey and O'Malley [ 6 ] framework, we met on seven occasions to discuss the challenges and develop recommendations for each stage of the methodological framework.

Recommendations to enhance scoping study methodology

We outline the challenges and recommendations associated with each stage of the methodological framework (Table (Table3 3 ).

Summary of challenges and recommendations for scoping studies

Framework stage one: Identifying the research question

Scoping study research questions are broad in nature as the focus is on summarizing breadth of evidence. Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] acknowledge the need to maintain a broad scope to research questions, however we found our research questions lacked the direction, clarity, and focus needed to inform subsequent stages of the research process, such as identifying studies and making decisions about study inclusion. To clarify this stage, we recommend that researchers combine a broad research question with a clearly articulated scope of inquiry. This includes defining the concept, target population, and health outcomes of interest to clarify the focus of the scoping study and establish an effective search strategy. For example, in one author's (KO) scoping study, the research question was broadly 'what is known about HIV and rehabilitation?' Defining the concept of 'rehabilitation' was essential in order to establish a clear scope to the study, guide the search strategy, and establish parameters around study selection in subsequent stages of the process [ 7 ].

Although Arskey and O'Malley [ 6 ] outline four main purposes for undertaking a scoping study, they do not articulate that purpose be specified within a specific framework stage. We recommend researchers simultaneously consider the purpose of the scoping study when articulating the research question. Linking a clear purpose for undertaking a scoping study to a well-defined research question at the first stage of the framework will help to provide a clear rationale for completing the study and facilitate decision making about study selection and data extraction later in the methodological process. A helpful strategy may be to envision the content and format of the intended outcome that may assist researchers to clearly determine the purpose at the beginning of a study. In the abovementioned HIV study, authors linked the broadly stated research question with a more specific purpose 'to identify the key research priorities in HIV and rehabilitation to advance policy and practice for people living with HIV in Canada' [ 7 ]. The envisioned outcome was a thematic framework that represented strengths and opportunities in HIV rehabilitation research, followed by a list of the key research priorities to pursue in future work.

Finally, the purposes put forth by Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] require more debate. We concur with Anderson et al. [ 2 ] and Davis et al. [ 1 ], who state that researchers may benefit from further clarification of the purposes for undertaking a scoping study. The first purpose, as articulated by Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ], is to summarize the extent, range, and nature of research activity; however, researchers are not required to reflect on their underlying motivation for doing so. We recommend that researchers consider the rationale for why they should summarize the activity in a field and the implications that this will have on research, practice, or policy. The second purpose is to assess the need for a full systematic review. However, it is difficult to determine whether a systematic review is advantageous when a scoping study does not involve methodological quality assessment of included studies. Furthermore, it is unclear how this purpose differs from existing methods of determining feasibility for a systematic review. The third purpose is to summarize and disseminate research findings, but we question how this differs from other narrative or systematic literature reviews. Lastly, the fourth purpose of undertaking a scoping study -- to identify gaps in the existing literature -- may yield false conclusions about the nature and extent of those gaps if the quality of the evidence is not assessed. The purpose 'to identify the key research priorities in HIV and rehabilitation to advance policy and practice for people living with HIV in Canada' does not explicitly align with one of the four Arskey and O'Malley purposes [ 7 ]. However, it appears authors inherently first summarized the extent, range, and nature of research (purpose one) and identified gaps in the existing literature (purpose four) in order to subsequently identify the key research priorities in HIV and rehabilitation (author purpose). This suggests authors might have an overall study purpose with multiple objectives articulated by Arksey and O'Malley that are required in order to help achieve their overall purpose.

Framework stage two: Identifying relevant studies

A strength of scoping studies includes the breadth and depth, or comprehensiveness, of evidence covered in a given field [ 1 ]. However, practical issues related to time, funding, and access to resources often require researchers to consider the balance between feasibility, breadth, and comprehensiveness. Brien et al. [ 5 ] reported that their search strategy yielded a vast amount of literature, making it difficult to determine how in depth to carry out the information synthesis. Although Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] identify these concerns and provide some suggestions to support these decisions, we also struggled with the trade-off between breadth and comprehensiveness and feasibility in our scoping studies. As such, we recommend that researchers ensure decisions surrounding feasibility do not compromise their ability to answer the research question or achieve the study purpose. Second, we recommend that a scoping study team be assembled whose members provide the methodological and context expertise needed for decisions regarding breadth and comprehensiveness. When limiting scope is unavoidable, researchers should justify their decisions and acknowledge the potential limitations of their study.

Framework stage three: Study selection

Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] provide suggestions to manage the time-consuming process of determining which studies to include in a scoping study. We experienced this stage as more iterative and requiring additional steps than implied in the original framework. While Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] do not indicate a team approach is imperative, we agree with others and suggest scoping studies involve multidisciplinary teams using a transparent and replicable process [ 2 , 10 ]. In two of our studies (HC and DL) where decision making was primarily completed by a single author, we faced several challenges, including uncertainty about which studies to include, variables to extract on the data-charting form, and the nature and extent of detail to conduct the data extraction process. This raised questions related to rigor and led to our recommendations for undertaking a systematic team approach to conducting a scoping study.

Specifically, we recommend that the team meet to discuss decisions surrounding study inclusion and exclusion at the beginning of the scoping process. Refining the search strategy based on abstracts retrieved from the search and reviewing full articles for study inclusion is also a critical step. We recommend that at least two researchers each independently review abstracts yielded from the search strategy for study selection. Reviewers should meet at the beginning, midpoint, and final stages of the abstract review process to discuss any challenges or uncertainties related to study selection and to go back and refine the search strategy if needed. This can help to alleviate potential ambiguity with a broad research question and to ensure that abstracts selected are relevant for full article review. Next, two reviewers should independently review the full articles for inclusion. When disagreements occur, a third reviewer can be consulted to determine final inclusion.

Framework stage four: Charting the data

This stage involves extracting data from included studies. Based on our experiences, we were uncertain about the nature and extent of information to extract from the included studies. To clarify this stage, we recommend that the research team collectively develop the data-charting form to determine which variables to extract that will help to answer the research question. Secondly, we recommend that charting be considered an iterative process in which researchers continually update the data-charting form. This is particularly true for process-oriented data, such as understanding how a theory or model has been used within a study. Uncertainty about the nature and extent of data that should be extracted may be resolved by researchers beginning the charting process and becoming familiar with study data, and then meeting again to refine the form. We recommend an additional step to charting the data in which two researchers independently extract data from the first five to ten studies using the data-charting form and meet to determine whether their approach to data extraction is consistent with the research question and purpose. Researchers may review one study several times within this stage. The number of researchers involved in the data extraction process will likely depend upon the number of included studies. For example, in one study, authors had difficulty developing one data-charting form that could apply to all included studies representing a range study designs, reviews, reports, and commentaries [ 7 ]. As a preliminary step, authors decided to classify the included studies into three areas --HIV disability, interventions, and roles of rehabilitation professionals in HIV care -- to help determine the nature and extent of information to extract from each of the types of studies [ 7 ].

Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] refer to a 'descriptive analytical method' that involves summarizing process information, such as the use of a theory or model in a meaningful format. Our experiences indicated that this is a highly valuable, though challenging aspect of scoping studies, as we struggled to chart and summarize complex concepts in a meaningful way. Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] indicate that synthesis of material is critical as scoping studies are not a short summary of many articles. We agree, and feel that additional direction in the framework might help to navigate this crucial but challenging stage. Perhaps synthesizing process information may benefit from utilization of qualitative content analysis approaches to make sense of the wealth of extracted data [ 11 ]. This issue also highlights the overlap with the next analytical stage. The role and relevance of analyzing process data and using qualitative content analysis within scoping study methodology requires further discussion.

Framework stage five: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Stage five is the most extensive in the scoping process, yet it lacks detail in the Arksey and O'Malley framework. Scoping studies have been criticized for rarely providing methodological detail about how results were achieved [ 1 ]. We appreciate the importance of breaking the analysis phase into meaningful and systematic steps so that researchers can provide this undertake scoping studies and report on findings in a rigorous manner. As a result, we recommend three distinct steps in framework stage five to increase the consistency with which researchers undertake and report scoping study methodology: analyzing the data, reporting results, and applying meaning to the results. As described in the existing framework, analysis (otherwise referred to as collating and summarizing) should involve a descriptive numerical summary and a thematic analysis. Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] describe the need to provide a descriptive numerical summary, stating that researchers should describe the characteristics of included studies, such as the overall number of studies included, types of study design, years of publication, types of interventions, characteristics of the study populations, and countries where studies were conducted. However, the description of thematic analysis requires additional detail to assist authors in understanding and completing this step. In our experience, this analytical stage resembled qualitative data analytical techniques, and researchers may consider using qualitative content analytical techniques [ 10 ] and qualitative software to facilitate this process.

Second, when reporting results, we recommend that researchers consider the best approach to stating the outcome or end product of the study and how the scoping study findings will be articulated to readers ( e.g ., through themes, a framework, or a table of strengths and gaps in the evidence). This product should be tied to the purpose of the scoping study as recommended in framework stage one.

Finally, in order to advance the legitimacy of scoping study methodology, we must consider the implications of findings within the broader context. As a result, we recommend that researchers consider the meaning of their scoping study results and the broader implications for research, policy, and practice. For example, for the question 'how are motor-learning strategies used within contemporary physical and occupational therapy intervention approaches for children with neuromotor conditions?,' the author (DL) presented themes that described strategy use. Results yielded insights into how researchers should better describe interventions in their publications and provided further considerations for clinicians to make informed decisions about which therapeutic approach might best fit their clients' needs. Considering the overall implications of the results as an explicit framework stage will help to ensure that scoping study results have practical implications for future clinical practice, research, and policy. This recommendation leads to the final stage of the framework.

Optional stage six: Consultation

Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] suggest that consultation is an optional stage in conducting a scoping study. Although only one of our three scoping studies incorporated this stage, we argue that it adds methodological rigor and should be considered a required component. Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] suggest that the purposes of consulting with stakeholders are to offer additional sources of information, perspectives, meaning, and applicability to the scoping study. However, it is unclear when, how, and why to consult with stakeholders, and how to analyze and integrate these data with the findings. We recommend researchers clearly establish a purpose for the consultation, which may include sharing preliminary findings with stakeholders, validating the findings, or informing future research. We suggest researchers use preliminary findings from stage five (either in the form of a framework, themes, or list of findings) as a foundation from which to inform the consultation. This will enable stakeholders to build on the evidence and offer a higher level of meaning, content expertise, and perspective to the preliminary findings. We also recommend that researchers clearly articulate the type of stakeholders with whom they wish to consult, how they will collect the data ( e.g ., focus groups, interviews, surveys), and how these data will be analyzed, reported, and integrated within the overall study outcome.

Finally, given that consultation requires researchers to orient stakeholders on the scoping study purpose, research question, preliminary findings, and plans for dissemination, we recommend that this stage additionally be considered a knowledge transfer mechanism. This may address Brien et al .'s [ 5 ] concern about the usefulness of scoping studies for stakeholders and how to translate knowledge about scoping studies. Given the importance of knowledge transfer and exchange in the uptake of research evidence [ 12 , 13 ], the consultation stage can be used to specifically translate the preliminary scoping study findings and develop effective dissemination strategies with stakeholders in the field, offering additional value to a scoping study.

One scoping study included a consultation phase comprised of focus groups and interviews with 28 stakeholders including people living with HIV, researchers, educators, clinicians, and policy makers [ 7 ]. Authors shared preliminary findings from the literature review phase of the scoping study with stakeholders and asked whether they may be able to identify any additional emerging issues related to HIV and rehabilitation not yet published in the evidence. The team proceeded to conduct a second consultation with 17 new and returning stakeholders whereby the team presented a preliminary framework of HIV and rehabilitation research and stakeholders refined the framework to further identify six key research priorities on HIV and rehabilitation. This series of consultations engaged community members in the development of the study outcome and provided opportunities for knowledge transfer about HIV and rehabilitation research. This process offered an ideal mechanism to enhance the validity of the study outcome while translating findings with the community. Nevertheless, further development of steps for undertaking knowledge translation as a part of the scoping study framework is required.

Additional considerations for scoping studies to support the advancement, application, and relevance of scoping studies in health research

Scoping study terminology.

Discrepancies in nomenclature between 'scoping reviews,' 'scoping studies,' 'scoping literature reviews,' and 'scoping exercises' lead to confusion. Despite our collective use of the Arksey and O'Malley framework, two authors (DL, HC) titled their studies as 'scoping reviews' while the other used 'scoping study.' In this paper, we use 'scoping studies' for consistency with Arksey and O'Malley's original framework. Nevertheless, the potential differences (if any) among the terms merit clarification. Lack of a universal definition for scoping studies is also problematic to researchers trying to clearly articulate their reasons for undertaking a scoping study. Finally, we advocate for labeling the methodology as the 'Arksey and O'Malley framework' to provide consistency for future use.

Quality assessment

Another consideration for scoping study methodology is the potential need to assess included studies for methodological quality. Brien et al. [ 5 ] state that this lack of quality assessment makes the results of scoping studies more challenging to interpret. Grant and Booth [ 4 ] imply that a lack of quality assessment limits the uptake of scoping study findings into policy and practice. While our research questions did not directly relate to any quality assessment debate, we recognize the challenges in assessing quality among the vast range of published and grey literature that may be included in scoping studies. This also raises the question of whether and how evidence from stakeholder consultation is evaluated in the scoping study process. It remains unclear whether the lack of quality assessment impacts the uptake and relevance of scoping study findings.

A final consideration for legitimization of scoping study methodology includes the development of a critical appraisal tool for scoping study quality [ 5 ]. Anderson et al. [ 2 ] offer criteria for assessing the value and utility of a commissioned scoping study in health policy contexts, but these criteria are not necessarily applicable to scoping studies in other areas of health research. Developing a critical appraisal tool would require the elements of a methodologically rigorous scoping study to be defined. This could include, but would not be limited to, the minimum level of analysis required and the requirements for reporting results. Overall, the issues surrounding quality assessment of included studies and subsequent scoping studies require further discussion.

Limitations

This paper responds to Arksey and O'Malley's [ 6 ] request for feedback to their proposed methodological framework. However, the recommendations that we propose are derived from our subjective experiences undertaking scoping studies of varying sizes in the rehabilitation field, and we recognize that they may not represent the opinions of all scoping study authors. Other than our individual experiences with our own studies, we have not yet implemented the full framework recommendations. Hence, readers can determine how strongly to interpret and implement these recommendations in their scoping study research. We invite others to trial our recommendations and continue the process of refining and improving this methodology.

Scoping studies present an increasingly popular option for synthesizing health evidence. Brien et al. [ 5 ] argue that guidelines are required to facilitate scoping review reporting and transparency. In this paper, we build on the existing methodological framework for scoping studies outlined by Arksey and O'Malley [ 6 ] and provide recommendations to clarify and enhance each stage, which may increase the consistency with which researchers undertake and report scoping studies. Recommendations include: clarifying and linking the purpose and research question; balancing feasibility with breadth and comprehensiveness of the scoping process; using an iterative team approach to selecting studies and extracting data; incorporating a numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis; identifying the implications of the study findings for policy, practice, or research; and adopting consultation as a required component of scoping study methodology. Ongoing considerations include: establishing a common accepted definition and purpose(s) of scoping studies; defining methodological rigor for the assessment of scoping study quality; debating the need for quality assessment of included studies; and formalizing knowledge translation as a required element of scoping methodology. Continued debate and development about scoping study methodology will help to maximize the usefulness of scoping study findings within healthcare research and practice.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DL and HC conceived of this paper. DL undertook the literature review process. DL, HC and KO developed challenges and recommendations. All authors drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

DL is a physical therapist and doctoral candidate in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. HC is an occupational therapist and doctoral candidate in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. KO is a clinical epidemiologist, physical therapist, and postdoctoral fellow in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. She is also a Lecturer in the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Toronto.

Acknowledgements

DL is supported by a Doctoral Award from the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program, a strategic training initiative of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the McMaster Child Health Research Institute. HC is supported by a Doctoral Award from the CIHR, the CIHR Quality of Life Strategic Training Program in Rehabilitation Research and the Canadian Occupational Therapy Foundation. KO is supported by a Fellowship from the CIHR, HIV/AIDS Research Program and a Michael DeGroote Postdoctoral Fellowship (McMaster University). The authors acknowledge the helpful feedback of Dr. Cheryl Missiuna on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

- Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; 46 :1386–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Sys. 2008; 6 :7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rumrill P, Fitzgerald S, Merchant W. Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work. 2010; 35 :399–404. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant M, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009; 26 :91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brien S, Lorenzetti D, Lewis S, Kennedy J, Ghali W. Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implement Sci. 2010; 5 :2. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-2. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005; 8 :19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Brien K, Wilkins A, Zack E, Solomon P. Scoping the field: identifying key research priorities in HIV and rehabilitation. AIDS Behav. 2010; 14 :448–458. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9528-z. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levac D, Wishart L, Missiuna C, Wright V. The application of motor learning strategies within functionally based interventions for children with neuromotor conditions. Peds Phys Ther. 2009; 21 :345–355. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181beb09d. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Colquhoun H, Letts L, Law M, MacDermid J, Missiuna C. A scoping review of the use of theory in studies of knowledge translation. Can J Occup Ther. in press . [ PubMed ]

- Ehrich K, Freeman G, Richards S, Robinson I, Shepperd S. How to do a scoping exercise: continuity of care. Res Pol Plan. 2002; 20 :25–29. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005; 15 :1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006; 26 :13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schuster M, McGlynn E, Brook R. How good is the quality of healthcare in the United States? Milbank Q. 2005; 83 :843–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00403.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. In: Studying the organization and delivery of health services: research methods. Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, editor. London: Routledge; 2001. Synthesising research evidence; p. 194. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Knowledge Translation. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html

How Do I Scope, Shape and Configure My Research Project?

- First Online: 28 June 2019

Cite this chapter

- Ray Cooksey 3 &

- Gael McDonald 4

1752 Accesses

In this chapter, we show that in order to make your research feasible and realistically achievable, you need to make scoping and shaping choices, pertaining to the nature of the research activities that you will use to gather the evidence you need and configuring choices, pertaining to the patterns and connections between those research activities. Such choices move you toward the ‘pointy end’ of research where you assemble the evidence you need to address your research questions/hypotheses. Appropriately scoping, shaping and configuring research will typically require adaptations and trade-offs in response to impediments or constraints you experience or can foresee down the track in order to achieve project feasibility. We also argue that you may, in addition, need to build up some type of conceptual framework to help guide your scoping, shaping and configuring activities.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alfawaz, A. (2015). Recruitment and selection practices for female administrative officers in Saudi public sector universities. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW

Google Scholar

Anderson, B. F., Deane, D. H., Hammond, K. R., McClelland, G. H., & Shanteau, J. C. (1981). Concepts in judgement and decision making: Definitions, sources, interrelations, comments . New York: Praeger Publishers.

Azorín, J. M., & Cameron, R. (2010). The application of mixed methods in organisational research: A literature review. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 8 (2), 95–105.

Braund, M. (2001). Understanding public perceptions of police in the ACT through observations of police-public turf interactions and surveys of the public . Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Department of Marketing and Management, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Cavana, R. Y., Delahaye, B. L., & Sekaran, U. (2001). Applied business research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Milton, QLD, Australia: Wiley.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Cooksey, R. W. (2014). Illustrating statistical procedures: Finding meaning in quantitative data (2nd ed.). Prahran, VIC: Tilde University Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Cryer, J. D., & Chan, K.-S. (2008). Time series analysis: With applications in R . New York: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Fieger, P. (2015). Efficiency and effectiveness in the Australian Technical and Further Education system. unpublished Ed.D. portfolio, UNE Business School, University of New England, NSW.

Fisher, C. (2007). Researching and writing a dissertation: A guidebook for business students (2nd ed.). Essex, UK: Pearson Education.

Flick, U. (2018). Triangulation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 444–461). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Glaser, B. (1992). The basics of grounded theory analysis . Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glass, G. V., Willson, V. L., & Gottman, J. N. M. (2008). Design and analysis of time-series experiments . Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Gregson, W. (2016). Harnessing sources of innovation, useful knowledge and leadership within a complex public sector agency network: A reflective practice perspective. Unpublished Ph.D.I portfolio, UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Harrison, J. (2003). Information scope in small service firms: A comparison of universalistic, contingency and configurational theoretical approaches. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Henryks, J. (2009). Organic foods, choice and consumer context: An exploration of switching behavior . Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, School of Business, Economics and Public Policy, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4), 602–611.

Article Google Scholar

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33 (7), 14–26.

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2001). The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial: gold standard or golden calf? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54 (6), 541–549.

Kincheloe, J. L. (2005). On to the next level: Continuing the conceptualization of the bricolage. Qualitative Inquiry, 11 (3), 323–350.

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Morse, J. M., Stern, P. N., Corbin, J., Bowers, B., Charmaz, K., & Clarke, A. E. (2009). Developing grounded theory: The second generation . Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Muchiri, M. (2006). Transformational leader behaviours, social processes of leadership and substitutes for leadership and their relationships with employee commitment, organisational efficacy and citizenship behaviours. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, New England Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Patton, M. Q. (2011). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use . New York: The Guilford Press.

Ross, E. (1999). Academics’ perceptions of university culture and the factors that facilitate or inhibit commitment to it . Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Department of Marketing and Management, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Sandall, J. (2006). Navigating pathways through complex systems of interacting problems: Strategic management of native vegetation policy. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, New England Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Smyth, R., & Maxwell, T. W. (2008). The research matrix: An approach to supervision of higher degree research . Milperra, NSW: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australia.

Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9 (2), 221–232.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). The basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques . London: Sage Publications.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2010). Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2011). Mixed methods research: Contemporary issues in an emerging field. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 285–299). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wolodko, K. (2017). The emergence of group dynamics from contextualised social processes: A complexity-oriented grounded-theory approach. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

Ray Cooksey

RMIT University Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Gael McDonald

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ray Cooksey .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cooksey, R., McDonald, G. (2019). How Do I Scope, Shape and Configure My Research Project?. In: Surviving and Thriving in Postgraduate Research. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7747-1_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7747-1_12

Published : 28 June 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-7746-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-7747-1

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research guides

Writing a Literature Review

Phase 1: scope of review, it's a literature review of what, precisely.

Need to Have a Precise Topic It is essential that one defines a research topic very carefully. For example, it should not be too far-reaching. The following is much too broad:

"Life and Times of Sigmund Freud"

However, this is more focused and specific and, accordingly, a more appropriate topic:

"An Analysis of the Relationship of Freud and Jung in the International Psychoanalytic Association, 1910-1914"

Limitations of Study In specifying precisely one's research topic, one is also specifying appropriate limitations on the research. Limiting, for example, by time, personnel, gender, age, location, nationality, etc. results in a more focused and meaningful topic.

Scope of the Literature Review It is also important to determine the precise scope of the literature review. For example,

- What exactly will you cover in your review?

- How comprehensive will it be?

- How long? About how many citations will you use?

- How detailed? Will it be a review of ALL relevant material or will the scope be limited to more recent material, e.g., the last five years.

- Are you focusing on methodological approaches; on theoretical issues; on qualitative or quantitative research?

- Will you broaden your search to seek literature in related disciplines?

- Will you confine your reviewed material to English language only or will you include research in other languages too?

In evaluating studies, timeliness is more significant for some subjects than others. Scientists generally need more recent material. However, currency is often less of a factor for scholars in arts/humanities. Research published in 1920 about Plato's philosophy might be more relevant than recent studies.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Phase 2: Finding Information >>

- Last Updated: Dec 5, 2023 2:26 PM

- Subjects: Education , General

- Tags: literature_review , literature_review_in_education

Good review practice: a researcher guide to systematic review methodology in the sciences of food and health

- About this guide

- Part A: Systematic review method

- What are Good Practice points?

- Part C: The core steps of the SR process

- 1.1 Setting eligibility criteria

- 1.2 Identifying search terms

- 1.3 Protocol development

- 2. Searching for studies

- 3. Screening the results

- 4. Evaluation of included studies: quality assessment

- 5. Data extraction

- 6. Data synthesis and summary

- 7. Presenting results

- Links to current versions of the reference guidelines

- Download templates

- Food science databases